?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

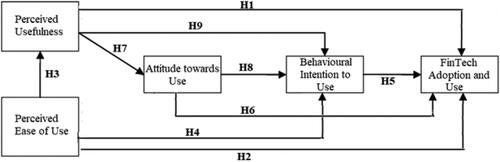

This study investigates the determinants of FinTech adoption among small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Ghana, utilizing the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) as a theoretical framework. It employed a survey design with a quantitative approach to data analysis. Data was gathered from a sample of 309 SMEs by adapting a closed-ended questionnaire. To test the hypotheses, the data were analysed using structural equation modelling Partial Least Square. The findings of this research demonstrate that the majority of the constructs in the conceptual framework has significant explanatory power in relation to the desire to embrace FinTech in Ghana. Specifically, 11 out of the total 13 hypotheses were confirmed. The key factor that positively impacts the uptake of FinTech innovations is the perceived usefulness, followed by the intention to use as the second influential factor. The results also indicate that there is a positive association between perceived ease of use and attitude towards use with FinTech adoption. Nevertheless, the observed direct impact of perceived ease of use on the adoption of FinTech is not statistically significant. But the impact of perceived ease of use on the adoption of FinTech is mediated by either perceived usefulness or intention to use. This research will assist FinTech service providers in designing FinTech services that take into account a wide range of SMEs’ needs. FinTech services could be made more beneficial to build attitude affirmations and shape intentions. This will encourage SMEs and other users to use FinTech regularly and persuade nonusers to try it.

IMPACT STATEMENT

The swift advancement of technology and the substantial user base of smartphones are revolutionising the manner in which the general public accesses financial services. Fintech firms continually engage in innovative practices to provide tailored products and services for individuals and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), with the aim of enhancing financial accessibility and inclusivity. This is done in order to contribute towards the United Nations’ goal of achieving financial inclusion as part of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by the year 2030. Fintech enables SMEs to achieve greater financial inclusion by providing them with access to digital financial solutions. The purpose of this technological breakthrough is to convert payment processes into digital formats, which would lead to decreased costs and the establishment of transparent and efficient payment systems, specifically benefiting SMEs. This study examines the factors that impact SMEs in their decision to adopt FinTech innovation for their business.

REVIIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

In the past decade, the financial industry has experienced many changed and development (Nurqamarani et al., Citation2021). Traditional banks have transformed significantly over the previous decade and, simultaneously, new financial service ideas have arisen. The innovations in technology have resulted in radical structural shifts in the delivery of financial services. Verma et al. (Citation2023) highlight that technology serves as the main channel in the financial sector, and it would be a chance for them to explore the efficiency of delivery better experience and convenience to consumers. Nonetheless, the pervasiveness of these innovations, known as financial technology (FinTech), poses a challenge for traditional banking and other financial institutions (McWaters, et al., 2018; Edo et al., Citation2023).

The trend of client engagement is increasingly shifting towards FinTech services, particularly in the realm of payments (Coffie et al., Citation2021; Nurqamarani et al., Citation2021). The aforementioned development has prompted a demand for the incorporation of Financial Technology (FinTech) services within organisations as a means to maintain competitiveness. In order to include financial technology services, it is imperative for the financial sector to gain a comprehensive understanding of the amount of customer acceptance towards the adoption of technology in financial services (Santini et al., Citation2023). The advent of FinTech has significantly transformed the corporate environment. FinTech refers to the integration of technology and finance, providing innovative solutions to organisations, including SMEs (Nurqamarani et al., Citation2021). According to Hsueh and Kuo (Citation2017), FinTech applications encompass several examples such as crowdfunding, peer-to-peer lending, and payment settlement. Whilst crowd funding is the act of raising funds from a large number of people to fund a project or business unit that involves the entire community (Lestari et al., Citation2020), peer-to-peer lending on the other hand is a platform that connects lenders and borrowers to meet their needs and provide efficient cash flow (Hsueh & Kuo, Citation2017). FinTech is considered innovative because it can easily connect all business lines into one platform.

Undoubtedly, the worldwide FinTech adoption index (2019) highlights that adoption of FinTech has moved consistently upward from 16% in 2015 to 64% in 2019, and the awareness of FinTech, even among nonadopters, is now very high. The recent Covid-19 pandemic also highlighted the growing necessity for digitalization, with FinTech enabling safe and distant operating across the international financial services, businesses and the economy at large. Among Ghanian firms, particularly SMEs, mobile payment services, a component of FinTech, has been the lead driver for the adoption of FinTech (Coffie et al., Citation2021). Today, cashless transactions are rampant in the sector with many FinTech startups such as ExpressPay, Hubtel, Slydepay, BezoMoney, Interpay, and PennySmart springing up. FinTech adoption is likely to experience a trajectory rise among SMEs as many nonadopters already use of FinTech services (Ernst & Young Global Limited, Citation2019; Huong et al., Citation2021; Nugraha et al., Citation2022).

From an empirical perspective, whilst studies proliferate on the factors that influence adoption of FinTech (Coffie et al., Citation2021; Ebrahim et al., Citation2021; Singh et al., Citation2020; Tan & Leby Lau, Citation2016), the majority of research conducted in the sub region has focused primarily on the adoption of FinTech payment services. These studies, such as those conducted by Ebrahim et al. (Citation2021), Singh et al. (Citation2020), and Tan and Leby Lau (Citation2016), have overlooked the significant role of attitude towards use and intention to use as crucial factors in relation to the acceptance of FinTech. This neglect is particularly evident when considering the theoretical framework of the traditional Technology Acceptance Model (TAM).

Despite its widespread use and popularity in both research and practical applications, empirical studies examining the TAM have revealed inconsistent findings regarding the role of attitude in the relationships between perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use, as well as behavioural intention and actual system use (Balcázar & Rivas, Citation2021; Dwivedi et al., Citation2019; Kim et al., Citation2009; Singh et al., Citation2020). Davis, Venkatesh, and their colleagues contend that the influence of attitude in elucidating behavioural intention or actual adoption behaviour is considerably restricted and, at most, serves as an incomplete intermediary for the association between salient beliefs (specifically, perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use) and user acceptance (Davis, Citation1989; Singh et al., Citation2020; Venkatesh & Morris, Citation2000).

While, current existing study such as Singh et al. (Citation2020) made a significant effort to address the existing research gap; nevertheless, their study mostly focused on capturing the perspectives of customers or consumers, rather than that of business owners. Therefore, it is imperative to examine the viewpoint of enterprises in order to contribute supplementary insights to the existing body of literature.

This study also utilises the TAM as a theoretical framework. In addition, it employs attitude towards use and perceived usefulness as mediating variables to study the indirection relationship of the variables with FinTech adoption and use in Ghana. This is because; the majority of scholarly investigations have focused on evaluating the direct influence of TAM variables on the adoption of FinTech. However, there is a limited amount of research available that examines the mediating impacts of perceived usefulness and intention to use on FinTech adoption. For instance, the existing body of research demonstrates a clear association between perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, attitude towards use, and behavioural intention in relation to the adoption of FinTech innovation services by SMEs (Adamek & Solarz, Citation2023; Balcázar & Rivas, Citation2021; Ebrahim et al., Citation2021; Singh et al., Citation2020; Verma et al., Citation2023). Consequently, investigating the direct and indirect effects of these variables, with some serving as mediators, would significantly contribute to the understanding of technology innovation adoption within the SME context

The remaining sections of this article are structured as follows. This study’s research model and hypotheses are described in the following section. The third section describes the research methodology, while the fourth section analyses the findings. The discussion and implications of the study then follow. The article concludes with conclusions, limitations, and future research directions.

2. Literature review and hypotheses development

The term ‘FinTech’ is a terminology derived from the combination of the words ‘finance’ and ‘technology’ (Balcázar & Rivas, Citation2021). It has gained significant popularity within the financial sector (Gai et al., Citation2018; Nurqamarani et al., Citation2021) due to the profound impact that technological advancements have had on the range of services provided by financial institutions (Adamek & Solarz, Citation2023; Edo et al., Citation2023). FinTech services have emerged as innovative alternatives that utilise internet and automated data processing along with emerging technologies like big data, artificial intelligence, IoT, and cloud computing (Lee & Shin, 2018). These services aim to disrupt the traditional methods of offering financial products (Milian et al., Citation2019) and expands payments, credit, wealth management, and insurance in advanced, emerging markets and developing economies (Verma et al., Citation2023). However, the scale of adoption differs widely in the context of developing countries (Frost, 2020).

This study investigates the acceptance and utilisation of the FinTech innovation among the SMEs in Ghana. However, in order to achieve this objective, it is important to employ a conceptual framework that facilitates the identification of the variables that drive business owners to embrace this innovation. The TAM is considered the most suitable approach for doing this analysis, as it provides an explanation and prediction of individual users’ adoption of information technology (IT) (Putri et al., Citation2023; Zulfikri et al., Citation2023). Given the efficacy of the TAM in elucidating individuals’ desire to adopt a specific technology, as well as its adaptability to the characteristics of the unit of analysis, this model has emerged as one of the most extensively utilised in the realm of scholarly investigation (Zhang et al., Citation2018).

In order to investigate what motivates FinTech adoption, this study categories the constructs along two dimensions: behavioural attributes and adoption attributes. The TAM model derives the behavioural attributes of perceptions of technology’s ease of use and utility because they predict attitude and subsequent acceptance and use of technology (Singh et al., Citation2020; Venkatesh & Morris, Citation2000). The TAM suggests that two beliefs about a new technology, namely perceived simplicity of use and perceived usefulness, influence a user’s initiative towards using that technology, which in turn influences their intention to use it.

The second aspect pertains to the adoption attributes that influence individuals’ behavioural intention to utilise FinTech services. The dependent variable in the present study is the actual use of FinTech services, which is regarded a crucial factor for their success (Venkatesh et al., Citation2012; Yoon et al., Citation2023). The factor of actual usage, which has received less scholarly attention, is considered a significant influence in the adoption of technology, as revealed by earlier studies (Venkatesh et al., Citation2012; Venkatesh & Morris, Citation2000). The inclusion of these variables in the present study serves to strengthen its practical implication as it is common in many studies to integrate extra variables in order to augment the predictive capacity of the TAM variables (Singh et al., Citation2020).

2.1. Behavioural attributes

2.1.1. Perceived usefulness

The degree to which an individual believes that implementing technology would improve job performance is referred to as perceived usefulness (Davies, 1989; Mathwick et al., Citation2001; Verma et al., Citation2023) and reduce cost and bureaucratic processes (Contreras Pinochet et al., Citation2019) and time saving (Balcázar & Rivas, Citation2021). According to Vijayasarathy (Citation2004), perceived usefulness will show that using a given technology might be helpful for someone to accomplish a specific outcome in the online environment. Furthermore, López-Nicolás et al. (Citation2008) accept that the system ought to have the option to help the consumer to carry out a job easier, quicker and of better quality. In the context of this study, perceived usefulness in the adoption of FinTech is characterised as how well SMEs believe can coordinate the services into their everyday exercises (Kleijnen et al., Citation2004) and how it can upgrade their transaction (Chen, Citation2008). According to Luarn and Lin (Citation2005), the ultimate aim users exploit FinTech is that they can find them helpful.

The empirical examination of the impact of perceived usefulness on behavioural intention in the adoption of FinTech services across different geographical settings has been investigated (Adamek & Solarz, Citation2023; Balcázar & Rivas, Citation2021; Ebrahim et al., Citation2021; Singh et al., Citation2020; Verma et al., Citation2023). Given the widespread prevalence of FinTech services and their inherent convenience, it is of scholarly interest to examine the effect of perceived usefulness on the adoption of FinTech services. Consequently, the first hypothesis is formulated as follows:

H1. Perceived usefulness positively affects adoption of FinTech services by SMEs.

2.1.2. Perceived ease of use

According to Davis (Citation1989), perceived ease of use alludes to the degree where an individual believes that a system would be not difficult to utilise and that the system should not be complex to encourage its adoption (Rogers, Citation1995). This means to utilise a specific type of innovation; little exertion ought to be required by the user (Rasheed et al., Citation2019). This exertion can be physical and mental (Davis, Citation1989; Taylor & Todd, Citation1995). When SMEs adopts FinTech, perceived ease of use include ease of use of the payment method, simple admittances to customer services, little advances needed to make a payment, how available the assistance is on mobile phones with the fundamental features and software. Extensive studies have reported proof of the critical impact of Perceived ease of use on user behavioural intentions (Davis, Citation1989; Guriting & Oly Ndubisi, Citation2006). It is imperative that FinTech should not be difficult to use both by the young and the old, the educated and uneducated, and across all genders to impact its adoption. As confirmed in the literature, perceived ease of use affects users’ intention to adopt FinTech (Carlsson et al., Citation2005; Chuang et al., Citation2016; Hu et al., Citation2019; Marakarkandy et al., Citation2017; Venkatesh & Morris, Citation2000). In recent studies, researchers have also proven that perceived ease of use will not influence on consumer acceptance to use FinTech (Balcázar & Rivas, Citation2021; Nurunnisha, Citation2020; Nurunnisha et al., Citation2020; Singh et al., Citation2020; Verma et al., Citation2023). Based on a review of existing literature and empirical research, the second hypothesis is formulated as follows:

H2. Perceived ease of use positively affects adoption of FinTech services by SMEs.

H3. Perceived ease of use positively affects perceived usefulness (PU) for adoption of FinTech services by SMEs.

2.2 Adoption attributes

2.2.1. Actual adoption and use

The prominent technology acceptance and use models have supported the relationship between behaviour intention and use to capture the ‘adoption or acceptance’ (Davis, Citation1989; Singh et al., Citation2020). Because of this, most of the current research studies are more focused on investigating behaviour intention to predict use. The primary studies for technology acceptance and use are dominated by the information technology perspective (Davis, Citation1989; Venkatesh et al., Citation2012). The main aim of this study is to understand the impact of behaviour intention on actual use from the perspective of business success through actual use for FinTech services and to analyze the factors affecting the consumer perception about the offered FinTech services. This study considers actual usage as the frequency and an approximate number of times a FinTech service is used in a given period.

2.2.2. Intention to use

According to TAM, determining one’s attitude in using services will have influence one’s intention to use it. It can be said that the certainty of a person attitude will affect someone’s intention to use fintech services (Akinwale & Kyari, Citation2022). According to Meyliana et al. (Citation2019), Attitude is a very significant ingredient to customer’s intent to act favourable towards adoption of fintech. Thus, the following hypothesis is developed:

H4. Perceived ease of use positively influences intention to use.

H5. Intention to use positively affects adoption and use of FinTech services by SMEs.

2.2.3. Attitude towards use

According to TAM, attitude towards use refers to the degree to which a user likes or dislikes using technology (Davis, Citation1989). According to the traditional TAM, previous studies (Balcázar & Rivas, Citation2021; Ebrahim et al., Citation2021) have established a strong and statistically significant relationship between individuals’ attitudes towards a specific technology. The findings of Chuang et al. (Citation2016), Marakarkandy et al. (Citation2017), and Hu et al. (Citation2019) indicate that users’ attitudes play a significant role in the adoption of FinTech services. The significance of attitude as a primary determinant of FinTech adoption is underscored by the research conducted by Balcázar and Rivas (Citation2021) and Arseto and Soemitra (Citation2022). Thus, the following hypothesis is developed:

H6. Attitude towards use positively influences adoption of FinTech service by SMEs.

H7. Perceived Usefulness positively influence Attitude towards use of FinTech by SMEs.

H8. The attitude of SMEs towards the use of FinTech has a positive influence on their intention to adopt these technological innovations.

H9. SMEs attitudes towards the use of FinTech are positively influenced by their perceived usefulness.

2.3. Mediating variables

According to Hussein et al. (Citation2019), a mediator explains why and how a certain phenomenon occurs. Based on this argument and empirical evidence, the present study predicts the role of perceived usefulness and attitude towards use as mediating variables influencing the adoption and use of FinTech by SMEs.

The concept of perceived usefulness, as previously mentioned, pertains to the potential benefits that a technology may offer in everyday encounters (Singh et al., Citation2020). The significance of perceived usefulness is underscored by empirical research, as it has been found to have a direct association with an individual’s sentiments towards a certain technology (Davis, Citation1989; Kim et al., Citation2021). Perceived usefulness, in comparison to other perceptions connected to technology such as perceived ease of use, has been identified as having more robust associations with the multiple factors that impact the adoption of technology in various contexts (Kim et al., Citation2021; Venkatesh & Morris, Citation2000).

In addition to its direct impact on adoption, perceived usefulness has been found to play a mediating function in other areas, as evidenced by studies conducted by Burton-Jones and Hubona (Citation2006), Henderson and Divett (Citation2003), Purnawirawan et al. (Citation2012a), Xia and Bechwati (Citation2008), and Hussein et al. (Citation2019). An empirical study conducted by Burton-Jones and Hubona (Citation2006) discovered that the perceived usefulness of email and word processing systems plays a mediating role in individuals’ perception of ease of use, as well as their frequency and duration of usage. Similarly, Chawla and Joshi (Citation2023) have identified that perceived usefulness mediates the effect of perceived ease of use on technology adoption. In other words, a higher level of cognitive personalisation, referring to the extent to which customers connect with the information presented in a positive product review, is positively correlated with increased intents to purchase the product. The occurrence of this specific link is attributed to the mediating influence of the consumer’s perceived usefulness of the review. Accordingly, we propose the following hypotheses:

H10. Perceived usefulness mediates the relationship between perceived ease of use and SMEs’ adoption of Fintech services.

H11. Intention to use mediates the relationship between perceived usefulness and SMEs’ adoption of FinTech service.

H12. Intention to use mediates the relationship between perceived ease of use and SMEs’ adoption of FinTech service.

H13. Intention to use mediates the relationship attitude towards use and SMEs’ adoption of FinTech service.

3. Research context and methodology

3.1. Research context

This investigation is particularly relevant due to the notable rise in the adoption and utilisation of FinTech in Ghana, as evidenced by previous research conducted by Yeboah et al. (Citation2020) and Coffie et al. (Citation2021). The consideration of these two factors holds significant importance within the context of this study and contribute the existing knowledge. For instance, the impact of an individual’s attitude on their behaviours is arbitrated through the process of filtering information and forming their perspective of the environment (Dwivedi et al., Citation2019; Kim et al., Citation2009). Furthermore, the TAM posits that an individual’s inclination to adopt a new technology is contingent upon two key beliefs: perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness. These beliefs then influence the individual’s motivation to engage with the technology, ultimately shaping their intention to utilise it. The absence of comprehensive study that considers both variables in the sector has resulted in the existence of unexplored variables that may contribute to SMEs’ tendency to accept and utilise FinTech services.

Ghana has been selected as the study’s geographical context and primary data source due to its distinction as the first country in Sub-Saharan Africa to establish a cellular network, therefore making it one of the pioneering nations on the African continent as a whole (Coffie et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, the prioritization of information and communication technology (ICT) in 1992, along with the establishment of the National ICT for Accelerated Development program in 2003, led to the introduction of the inaugural biometric payment system known as ‘e-zwich’ in 2008 (Des Nations Unies, Citation2018; Tetteh et al., Citation2021). The aforementioned factor has played a significant role in the heightened utilization of peer-to-peer FinTech payment systems. The FinTech industry in Ghana is currently characterized by the prevalence of mobile-based, card-based, and online payment systems, as well as the widespread adoption of third-party blockchain applications. Consequently, Ghana has been selected as the key hub for SMEs in Sub-Saharan Africa to adopt FinTech payment services, with the aim of subsequently disseminating the knowledge and expertise gained from the Ghanaian SMEs to other nations in the region.

Accra, the nation’s capital, was the study setting. The region has become a thriving business destination, particularly for SMEs. Further, SMEs in Accra were chosen because they frequently have the opportunity to witness events such as product launches, project piloting, and product updates before they are disseminated to other regions, giving them the advantage of having in-depth interaction with products and services and adopting innovations. Finally, because the majority of SMEs, offices are in Greater Accra, obtaining information was simple and quick.

3.2. Research approach and design

The study quantitatively determines FinTech adoption among SMEs. The study used quantitative approach because this method enabled the researcher to use a questionnaire to collect data from a larger number of respondents for analysis. This research is a descriptive study that employed a survey research design to collect data (Tetteh et al., Citation2022). Descriptive research allows the researchers to describe phenomena by collecting data from members of a population (Bryman, Citation2012) which in this case were the owner managers/operators of SMEs. The study was based on a survey, and the researchers designed a Likert-type survey with descriptive rankings for the study’s key constructs, such as the perceive usefulness, perceive ease of use, attitude towards use, intention to use and FinTech adoption.

3.3. Population

The population for this study comprised of SMEs situated in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana, engaged in any sector of the economy; and who satisfy the Ghana Enterprises Agency (GEA) formerly known as National Board of Small-Scale Industries (NBSSI) definition of SMEs. The survey encompassed all SMEs that were officially registered with the Ghana Enterprises Agency within the Greater Accra Region of Ghana. As of March 2022, the Agency reported a total of 4,998 registered SMEs in the region. The unit of analysis in this study pertains to the individuals who assume the roles of owner managers/operators within the context of SMEs.

3.4. Sampling procedure

This study employed a convenience sampling technique to pick SMEs whose contact information and email addresses were available in the database of GEA. This approach was chosen to ensure easy accessibility to the owner-managers of these SMEs. Regarding the sample size, according to Hair et al. (Citation2017), the minimum sample size of Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) analysis is 100–150 respondents. However, Kline (Citation2011) proposed critical sample size of 200 respondents. To select the appropriate sample size, we adopted Miller and Brewer (Citation2003) formula to select the appropriate sample size from a target population of 5,963 for this study. A given sample size of approximately 374 SMEs was considered with the formula: n = N/1 + N(e)^2. Where n is the sample size, N is the population size and e is the margin of error (Miller & Brewer, Citation2003).

In order to meet the predetermined threshold, the study distribute 374 questionnaires to 374 SMEs, a number that significantly exceeds the specified criteria of 200. This approach was chosen to ensure that the resulting data analysis would produce sufficient statistical power. Out of the 374 questionnaires sent to the owner-managers or operators of the SMEs, only 309 SMEs were successfully completed and were valid for analysis, representing 77.8% of the sample size, presenting good data for analysis (Malhotra et al., Citation2017). As a result, the sample size for this study stood at 309 SMEs.

3.5. Data collection

Primary data was collected using a structured questionnaire adopted. The questionnaire was a close-ended questionnaire that allowed the respondents to choose options from a limited range of options with a 5-point Likert scale. The Ghana Enterprises Agency was contacted, and information containing registered SMEs in Accra Metropolitan Assembly was given to the researchers. The various registered SMEs were contacted within Accra Metropolitan Assembly. The questionnaire was an online survey through Google form and was sent to each respondent. The researchers did this because of the country was still observing the Covid-19 pandemic protocols, and most managers in the SMEs sector prefer sending them emails and calls rather than meeting them physically. The aforementioned methodology for data gathering is considered suitable in the context of interruptions caused by a pandemic (Nugraha et al., Citation2022). Due to the simple and precise wording of the questions, the respondents could fill the questionnaire with ease. The data collection lasted for one month.

3.6. Research instrumentation

The data collection instrument for the study was a structured questionnaire containing predominantly close-ended descriptive questions. The use of questionnaires was suitable for this study it helps the researcher ensure that, key topics were explored with a greater number of participants (Babbie, Citation2008; Tetteh et al., Citation2023). A Likert scale which ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree, was used. The questions were adapted from researchers who either used questions in a FinTech service or mobile money payment.

Perceived usefulness was adapted from Huh et al. (Citation2009) and Singh et al. (Citation2020). Perceived ease of use was adapted from Huei et al. (Citation2018) and Singh et al. (Citation2020). Attitude towards use was adapted from Grabner‐Kräuter and Faullant (Citation2008) and Singh et al. (Citation2020). Intention to use was adapted from (Marakarkandy et al., Citation2017). FinTech adoption was measured by items adapted from (Maradung, Citation2013). In all, twenty-nine (29) items were used to measure five (5) constructs. Four items each were used to measure Perceived Usefulness (PU), Perceived ease of use (PEU), Attitude towards use (ATU) and Intention to use (IU). Three items were used to measure FinTech (F). The instrument was in six (6) sections. The first (section A) part measured the demographic characteristics of the respondents, the second (section B) measure FinTech, the third (Section C), the fourth (Section D), the fifth (Section E), and the sixth (section F) measured both factors of adoption FinTech among SMEs.

3.7. Data analysis

The data analysis was done using descriptive analysis and partial least squares structural equation modelling methods available in SmartPLS version 3.3.3 (Hair et al., Citation2019). Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) was employed to assess the adequacy of the measurement model of the principal constructs and the predictive relevance of the conceptual model; and test the hypothesized relationships. PLS-SEM was suitable as the study’s main aim was concerned with exploiting the prediction of respective constructs to predict the contribution of various antecedents on intention to adopt FinTech among SMEs.

Also, PLS-SEM was selected because of its distribution -free assumption, which was appropriate for the study. The PLS algorithm allows each indicator to differ with how much it contributes to the composite score of the latent variables instead of assuming equal weight for all indicators of a scale (Hair et al., Citation2013). Though PLS-SEM estimates both the measurement model and the structural model alongside, the assessment of the estimated full model should follow Hair et al. (Citation2013) two-step approach; the examination of the outer model before the estimation of the structural (inner) model.

According to Hair et al. (Citation2019), the measurement model permits us to examine whether the constructs are measured with acceptable accuracy while the structural model helps us examine the explanatory power of the model. The former is, however. A prerequisite for the latter as it only makes sense to assess the structural model when the measurement model indicates evidence of reliability and validity (Henseler, Citation2017). The SmartPLS 3.3.3 version software was set to 500 bootstrap samples to estimate the significance of the t-values (Chin, Citation2010).

4. Findings and discussion

4.1. Demographic information

sets out the demographic profile of the respondents, and it consists of the gender, age, form of business, educational level of managers, type of business, for how long has your business been in operation. The profile also depicts number of employees, type of FinTech service adopted the SMEs and the number of years the SMEs has using FinTech system for business transaction.

Table 1. Constructs reliability and AVE.

Numerous demographic variables were collected in this study including, Gender, age, Form of Business, Type of Business, Educational level of managers, for how long has your business been in operation, number of employees, what type of FinTech service do your business operate, for how long have you used FinTech system for business transaction and these results have been abridged in . From the , out of 309 respondents comprised in this study 57.3% were male while 42.7% were female. Also, the results presented that 0% of the respondents were below age 18, with 34.6% between the ages 18 and 25. Respondents between the ages 26 and 34 were 43.0%. Respondent between the ages of 35 and 44 were made up of 16.2% with 45 and 59 years constituting 5.5%. Lastly 60 years and above were 0.6% of the respondent. This suggests that majority of them were in the economically active population.

Further, indicates that 74.1% of the respondents were involved in sole proprietorship business, 14.6% were Limited Liability Company and 11.3% were involved in partnership business. This result is consistent with Ayyagari et al. (Citation2014) findings that, SMEs in developing countries such as Ghana are deemed to be sole proprietorship. Also, 12.3% of the respondents were Diploma graduates. Majority (45.3) of the respondent were undergraduate students and 30.1% of them being postgraduate students. Others were 12.3%. Also, 46.6% of the respondents were into services, 17.8% were involve in manufacturing, 9.4% were into wholesaling business whiles 26.2% of the respondents were into Retailing Business.

Moreover, the results showed that 72.5% of the respondent has been in business between 2 and 5 years. Respondent between 6 and 9 years were 12.6% whiles 14.9% were those who has operated their business between 10 years and above. Also, the number of employees between 0 and 5 were 69.3% respondents, 21.7% respondents were between 6 and 29, 5.5% respondents were between 30 and 100, 3.6% respondents were between 101 and 250. Also, 9.1% had used Crowdfunding in FinTech service, 9.7% of the respondents had used P2P Lending in FinTech service. Majority (79.3%) of the respondent had used Payment system and 1.9% respondents had used other FinTech services. With regards to the number of years’ respondent had used FinTech for business transaction, 81.9% had used the service between 0 and 5 years whilst 11.0% had used the service between 6 and 10 years. Also, 7.1% had used the FinTech service 10 years and above.

This shows that most of the respondents have been active users of FinTech services for a while now. In terms of type of FinTech services business mostly operate, it was observed that 79.3% have been using payment system while other FinTech service were 1.9 apart from crowdfunding and P2P Lending. Finally, 81.9% of the respondent has used FinTech service in their business between 0 and 5 years whilst 11% of the respondent has used it between 6 and 10 years.

4.2. Assessment of the measurement model

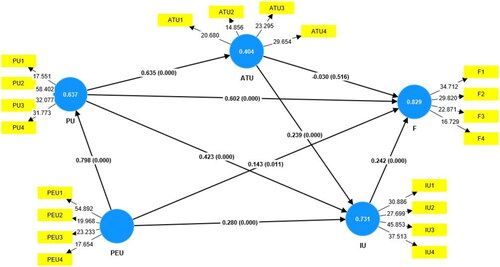

All the constructs in the study are reflective and not formative; hence to validate the model fitness, there is the need to examine the average variances extracted (AVE), composite reliabilities (CR), item loading’s size and significance, and discriminant validity (Liang et al., Citation2007). Cronbach’s alpha and the Composite Reliability test revealed that all constructs presented a value above the threshold 0.7 for both Cronbach’s alpha and CR, adopted by Bagozzi and Yi (Citation1988) ().

According to Hair et al. (Citation2019), reliability values between 0.60 and 0.70 are considered acceptable in exploratory research. Between 0.70 and 0.90 range from satisfactory to good. AVE exceeding 0.5 is reliable (Hair et al., Citation2017). Cronbach’s alpha greater than 0.7 is reliable (Hair et al., Citation2013) and if it is above 0.60 is also acceptable in exploratory research (Azlis-Sani et al., Citation2013).

4.3. Convergent validity

To test for convergent validity, composite reliability factor loading, and AVE (Average Variance Extracted) were examined. It is satisfactory if an individual item factor loading is greater than 0.7, composite reliability exceeds 0.7, and AVE exceeds 0.5 (Gefen et al., Citation2003). Hair et al. (Citation2017) suggest that factor loading greater than 0.60 is acceptable in exploratory research as depicted in . All loadings for the reflective constructs exceeded 0.7 except only PEU4, which was 0.693 and were shown to be significant at Bootstrap t-statistics.

Table 2. Cross loadings for items and convergent reliability.

4.4. Discriminant validity

Discriminant Validity was considered passable since the square root of the AVEs (in the diagonal) are greater than their respective inter-construct correlations, as in and (Hair et al., Citation2017). Extra support for discriminant validity comes through inspection of the cross-loadings (), which shows that the measurement items for each construct load higher on their respective constructs than they load on other constructs (Hair et al., Citation2013). Since the square root of the AVE’s (in the diagonal) are greater than their respective inter-construct correlations as portrayed in and , conditions for discriminant validity were fulfilled (Hair et al., Citation2017).

Table 3. Latent variable correlations and discriminant validity.

Also, the inspection of the cross-loadings in support discriminant validity, as it indicates that the measurement items for each construct load higher on their respective constructs than they load on other constructs (Hair et al., Citation2017). These confirm that the measurement items adequately explain their respective constructs more than they do explain other constructs in the structural model.

Radomir and Moisescu (Citation2020) and Shafique and Majeed (Citation2020) suggest that discriminant validity can be accepted when the difference between the constructs is too minor. Regarding perceived usefulness and FinTech, there is some disagreement. The difference, however, is 0.079 and can be disregarded. Overall, the discriminant validity of this measurement model is acceptable and supports the discriminant validity between the constructs. Consequently, discriminant Validity is attained.

4.5. Structural model assessment

The subsequent phase in the SEM procedure involves the assessment of the structural path coefficient, which pertains to the relationships between study constructs and their level of statistical significance. This follows the assessment of the measuring model.

4.5.1. Variance inflation factor

The examination of the Variable Inflation Factor (VIF) values is the first step in the structural model assessment (Hair et al., Citation2022). The VIF values were less than 3 as shown in , indicating that the data has no multicollinearity concerns (Hair et al., 2022).

Table 4. VIF values.

4.5.2. Direct path relationships

In PLS-SEM, structural models’ validity is measured through the strength of the sample mean, t-values, p-values for the significance of t-statistics, as well as effect sizes of independent variables on the dependent variables (Hair et al., Citation2013). The results of hypothesis testing are presented in and .

Following the validation of the measurement model, the structural model was developed to test the stated hypotheses. Regarding the examination of the conceptual model (refer to and and ), H1 assesses the influence of perceived usefulness on the adoption of FinTech services by SMEs. The findings of the study indicate that SMEs in Ghana are influenced by their perception of the usefulness of FinTech services when deciding to adopt them. This conclusion is supported by the statistical analysis, which shows that the t-value and p-value for the relationship between perceived usefulness and FinTech are both significant (t-value = 11.846, p-value = 0.000). Therefore, the hypothesis H1 has been proven or confirmed.

Table 5. Results of hypotheses testing for the model.

H2 was empirically examined in order to investigate the relationship between the perceived ease of use and the uptake of FinTech services within the context of SMEs in Ghana. The statistical analysis revealed that there was no significant effect seen between the perceived ease of use and the uptake of FinTech services (t-value = 2.535, p-value = 0.011), although the relationship was positive. Therefore, the H2 was not supported or validated.

The aim of H3 was to examine the relationship between perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness. The regression coefficient and its corresponding t and p values were statistically significant (t-value = 38.595, p-value = 0.000). Therefore, H3 was supported.

H4 aimed to evaluate the potential correlation between SMEs’ perception of ease of use and their intention to employ FinTech services. The findings indicated a statistically significant positive link between the two variables (t-value = 4.074, p-value = 0.000). Based on the findings of this study, it can be concluded that there is a positive relationship between the perceived ease of use and the desire to use FinTech services. Therefore, H4 has been confirmed or supported.

H5 was tested to assess the effect of intention to use on the adoption of FinTech services among SMEs. The t-value and p-value from intention to use and FinTech was significant (t-value = 4.197, p-value = 0.000). Based on this result, intention to use positively influenced the adoption of FinTech services, thus H4 was supported.

Further, H6 was tested to determine the influence of attitude towards use on the adoption of FinTech services among SMEs. The t-value and p-value from attitude towards use and FinTech was not significant although the relationship between the two variables was positive (t-value = 0. 649, p-value = 0.516). Therefore, H6 was not supported or confirmed.

H7 also tested the relationship between perceived usefulness and attitude towards use of FinTech services among SMEs. The results from the analysis revealed positive relationship and significant impact (t-value = 12.885, p-value = 0.000). Based on the confirmed results, H7 was supported.

The relationship between Attitude towards use and intention to use being H8 was found to be significant (t-value = 3.608, p-value = 0.001). It can be said that the certainty of a user attitude will influence someone’s intention to use FinTech services. The result indicates that, attitude is a very significant ingredient to SMEs’ intention to act favorable towards adoption of FinTech services. Hypothesis 8 was therefore supported.

Further, H9 examined the relationship between perceived usefulness and intention to use FinTech services among SMEs. The results found the impact to be significant and the relationship to be positive given the results of t-value and p-values (t-value = 6.110, p-value = 0.000). Therefore, H9 was supported or confirmed.

4.5.3. Model explanation power

The study also examined the structural model’s explanation power. This was accomplished with the R2. The R2 is a measure of the model’s explanatory ability and represents the variation explained in each of the endogenous constructs. According to Hair et al. (Citation2013, Citation2019), R2 values of 0.75, 0.50, and 0.25, respectively, can be classified as substantial, moderate, or weak. The R2 value in this study was 0.829 or 82.9% with an adjusted R2 of 0.827 or 82.7% for FinTech adoption and use. The adjusted R2 value of 82.7% suggests that a significant portion of the variance in the adoption of FinTech innovation services can be accounted for by the relationships incorporated within our model. In addition, adjusted R2 reported in this study demonstrates a high level of strength (Hair et al., Citation2013), surpassing the majority of models found in previous research on technology adoption. Typically, such studies find R2 values ranging from 0.30 to 0.50. Finally, the model’s predictive power, denoted as Q2, is 0.626, surpassing the suggested threshold of 0.35 as indicated by Hair (2017). shows the findings of F square, Q square, and R square (R2).

Table 6. R Square, f-square and Q-square.

4.6. Mediation analysis

The study additionally examined the indirect effects of perceived usefulness (PU), attitude towards use (ATU), and intention to use (IU) on Fintech innovation adoption and use. The findings are presented in .

Table 7. Mediating effects.

First, perceived ease of use has an indirect effect on FinTech adoption and use when fully mediated by perceived usefulness (t-value = 10.802, p-value = 0.000). Therefore, H10 was supported or confirmed. Secondly, the study discovered that perceived usefulness has an indirect effect on adoption FinTech services when fully mediated by intention to use (t-value = 3.303, p-value = 0.001). Therefore, H11 was supported or confirmed. Thirdly, perceived ease of use has an indirect effect on FinTech adoption and use when fully mediated by intention to use (t-value = 2.710, p-value = 0.007). Therefore, H12 was supported or confirmed. Lastly, attitude towards use has an indirect effect on adoption of FinTech service when mediated by intention to use (t-value = 3.225, p-value = 0.001).

4.7. Discussion of results

The study was set out to investigate the factors that influence adoption of FinTech among SMEs in Ghana. The study examines the hypotheses related to the TAM constructs, namely Perceived Usefulness (PU), Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU), Intention to Use (IU), and Attitude towards Use (ATU). Additionally, the study explores five indirect relationships within the TAM framework.

First, the findings of the study indicate that SMEs in Ghana are influenced by their perception of the usefulness of FinTech services when deciding to adopt them. Therefore, the hypothesis (H1) has been proven or confirmed. The result from this finding is consistent with the TAM that perceived usefulness shows how individual believes that performance will improve if technology is adopted (Putri et al., Citation2023; Zulfikri et al., Citation2023). This aligns with the claims made by a number of studies (Adamek & Solarz, Citation2023; Balcázar & Rivas, Citation2021; Ebrahim et al., Citation2021; Hu et al., Citation2019; Marakarkandy et al., Citation2017; Singh et al., Citation2020; Verma et al., Citation2023), as it confirms the significance of perceived usefulness in influencing users’ intention to adopt a specific technology due to the anticipated benefits or advantages it offers (Davis, Citation1989). Undeniably, the utilisation of FinTech platforms by SME owners is motivated, to some extent, by the functional benefits they offer. These benefits include convenience and performance, as highlighted by Singh et al. (Citation2020) and Verma et al. (Citation2023), as well as cost and bureaucratic process reduction, as noted by Contreras Pinochet et al. (Citation2019), and time-saving, as emphasised by Balcázar and Rivas (Citation2021). Hence, insofar as these financial innovations address the service-related requirements of SME owners or operators, they enable more efficient transactional processes compared to conventional alternatives that do not incorporate technological advancements. Therefore, it is reasonable to attribute the strong influence and positive correlation between perceived usefulness and FinTech adoption by SMEs to these aforementioned benefits.

Second, it was discovered that the perceived ease of use does not exert a statistically significant impact on the adoption of FinTech services among SMEs in Ghana. Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that there is a positive association between these two variables. The findings indicate that this particular variable did not have a significant impact on the inclination of SMEs to use FinTech services to a greater extent. Certainly, despite the contrasting findings in various researches (Balcázar & Rivas, Citation2021; Contreras Pinochet et al., Citation2019; Singh et al., Citation2020; Verma et al., Citation2023), it has been demonstrated that during the initial phase of technology adoption, the ease of use does not significantly influence adoption behaviours (Hu et al., Citation2019). This can be attributed to SMEs’ lack of familiarity with the FinTech’s functional characteristics and interface, as well as their limited knowledge on how to effectively interact with these platforms (Balcázar & Rivas, Citation2021; Davis, Citation1989). Therefore, the H2 was not supported or validated by the findings of this study. Nevertheless, the findings of this current study offer substantiation that this particular variable does indeed have an indirect influence on the adoption of FinTech by means of the interplay between perceived usefulness or intention to use. Consequently, this interplay has a somewhat positive effect on the adoption of FinTech, as illustrated in . The implications of a user-friendly and uncomplicated FinTech platform, which is easily managed by both customers and SMEs, with minimal effort required for payment transactions and prompt assistance from providers, contribute to the increased usefulness of the innovation. These factors significantly influence the intentions of SMEs to adopt the innovation.

Thirdly, concerning the variable attitude, in contrast to prior research conducted by Chuang et al. (Citation2016), Marakarkandy et al. (Citation2017), Hu et al. (Citation2019), and Balcázar and Rivas (Citation2021), the findings regarding the impact of SMEs’ attitude towards the adoption of FinTech services provide inadequate evidence to support the assertion that SMEs’ attitude influences the adoption of FinTech services. This can be attributed to the insignificant influence of SMEs’ attitude on the adoption of FinTech. However, it was observed that there is a positive association between the attitude of SMEs and the adoption of FinTech. The aforementioned researches have demonstrated that the attitudes of users have a substantial impact on the uptake of FinTech services. On the other hand, the present study findings indicate that the variable attitude plays a significant role in influencing adoption of FinTech through the interplay of intention to use. This finding aligns with a previous researches in the financial sector (Hu et al., Citation2019), which has demonstrated that variable attitude is associated with a range of intentions to engage in specific actions (Balcázar & Rivas, Citation2021; Davis, Citation1989). Hence, it can be deduced that the owners of the SMEs possess a favourable disposition towards the use of Fintech. This disposition is further reinforced by their intention to utilise Fintech services. Therefore, the level of Fintech acceptance is directly influenced by the intention of SMEs, while their attitude indirectly affects this adoption.

Finally, the study assessed the direct effect of intention to use on the adoption of FinTech services among the SMEs. Based on this result, intention to use positively influenced the adoption of FinTech services. Indeed, interest is widely recognised as a crucial factor influencing the desire to embrace novel systems or technologies (Al-Maghrabi & Dennis, 2011; Venkatesh et al., Citation2012). The present study validates Ajzen’s (Citation2006) proposition that an individual’s behavioural intentions are influenced by three cognitive factors: behavioural beliefs, normative beliefs, and control beliefs. In relation to the current study, it is evident that owners of SMEs possessed initial convictions regarding the outcomes of adopting FinTech (referred to as behavioural beliefs). Additionally, they acquired sufficient information through external sources such as media and professional associations (referred to as normative beliefs). Furthermore, they possessed knowledge about the current factors that may facilitate or hinder the utilisation of FinTech services (referred to as control beliefs). Therefore, all these three cognitive factors could have accounted for the statistically significant positive impact of the variable intention to use on the adoption of FinTech. The implication of this result is that managers of SMEs will only use FinTech when they have intentions to use them. The survey demonstrates that it is increasingly imperative for managers of SMEs to familiarise themselves with the prevalent trend of utilising FinTech services. Therefore, the consistent utilisation of FinTech innovations is expected to have a positive impact on the overall performance of the firms and improve their operational efficiency.

The study further performed mediation analysis and found that perceived usefulness played a positive and significant role in mediating the association between perceived ease of use and FinTech adoption and use. This was noted to be a full mediation because the direct path between perceived ease of use and FinTech adoption and use is insignificant. The current study aligns with the argument of Hussein et al. (Citation2019) that a mediator explains the reasoning and mechanism behind the manifestation of a specific phenomenon. The further analysis finds that SMEs perceive the realism of FinTech as beneficial, thereby substantiating their adoption of this innovation based on its perceived ease of use or user-friendliness. Again, when examining the perceived usefulness of FinTech Adoption, it is observed that SMEs view the functioning of FinTech innovation to be beneficial. This impression subsequently enhances their perception of the convenience of using FinTech for adoption purposes. Indeed, existing studies have also provided evidence for the mediating function of perceived usefulness, as demonstrated by studies conducted by Purnawirawan et al. (Citation2012b), Hussein et al. (Citation2019), and Chawla and Joshi (Citation2023).

Another interestingly revelation was the variable intention to use also significantly and positively mediating the relationship between (perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness and attitude towards use) and FinTech innovation adoption and use by the SMEs. Additionally, our findings indicate that the utilization of Fintech services is influenced by the intention to use. Additionally, it was shown that the influence of the intention to use on the connection between perceived usefulness and FinTech adoption was only partial, since the direct pathway was found to be significant. Nevertheless, it was seen that the connections between intention to use and the links between perceived ease of use and attitude towards use, as well as Fintech adoption and use, were fully mediated due to the insignificance of the direct pathways. This suggests that the adoption of FinTech by SMEs relies on factors such as awareness of its benefits, the user-friendliness of the technology, and the prevailing attitude towards its usage (Kosasi et al., Citation2019; Venkatesh et al., Citation2012). However, it is important to note that SME managers will only implement the technology if they possess the intention to do so. Hence, the present analysis identifies the presence of intention to use as a significant predictor of actual adoption, thereby supplementing previous research conducted in many domains (Al-Maghrabi & Dennis, 2011; Ravichandran et al., Citation2010; Venkatesh et al., Citation2012).

5. Theoretical and practical implications

The findings from the hypothesis testing suggest that the model well captures the various factors that impact the adoption of FinTech SMEs. The present study has contributed to the expansion of knowledge regarding the factors that impact the adoption of FinTech among SMEs in developing nations. The findings of this research build upon previous investigations into the adoption of FinTech, which predominantly rely on the TAM as the underlying theoretical framework. The results demonstrate a significant impact of 11 out of the 13 hypotheses that were examined, yielding an overall explanatory power of 82.9% ( of 0.829).

The practical ramifications of our findings are noteworthy. The FinTech business is seeing significant transformations, with new technology being introduced to the market on a daily basis. From the standpoint of SMEs, it is imperative for users to consistently adjust and acclimatise themselves to the latest products. In order to attain effective adaptation and generate commercial gains, it is important for FinTech service providers to thoroughly understand and include the needs and perspectives of SMEs. This is crucial since the perceived usefulness factor plays a mediating role in influencing the adoption of FinTech services. In addition, it is important for the facilitators/diffusers of FinTech innovations to also address the behavioural intentions of SMEs. This is because behavioural intention to utilize FinTech services has emerged from the current study results as a crucial factor in determining the likelihood of adoption and usage by users.

6. Conclusion, limitation, and avenue for future study

This study examined the factors that influence the adoption of FinTech services in Ghana, employing the TAM as the theoretical framework. With respect to the demographic characteristics of SME owners, the research revealed that the FinTech service utilized most by these SMEs is the payment system. Furthermore, it was observed that a significant proportion (81.9%) of SMEs have employed FinTech for conducting business transactions within a duration of 0–5 years. This suggests that the utilisation of FinTech by SMEs will lead to a subsequent enhancement in their business profitability through cost reduction as observed in the literature (Contreras Pinochet et al., Citation2019), The study additionally revealed that a majority of managers have a formal educational qualification, thereby indicating their capacity to understand financial information to a certain extent using FinTech.

Further, the findings derived from this research demonstrate that the majority of the constructs included in the conceptual framework has significant explanatory power in relation to the desire to embrace FinTech services in Ghana. Specifically, 11 out of the total 13 hypotheses were confirmed. The findings of the research offer valuable insights into the factors that influence the adoption of FinTech. The key factor that positively impacts the intention to embrace FinTech services is the perceived usefulness, followed by the intention to use as the second influential factor. The results indicate that there is a positive association between perceived ease of use and attitude towards use with FinTech adoption. However, it is important to note that these factors have a limited impact on the acceptance of FinTech services.

In nutshell, it can be concluded that owner managers of SMEs maintain a positive perception of the usefulness of FinTech services in enhancing their overall business performance. This is due to the fact that the owner managers hold the belief that the adoption of FinTech will yield benefits in terms of enhancing operational efficiency and ensuring the attainment of favourable outcomes in the future. Consequently, their inclination towards adopting FinTech is heightened, thereby influencing their intention to adopt and use the service in subsequent periods. The research findings indicate that there are positive associations between behavioural factors, such as usefulness and ease of use, and adoption attributes, such as attitude and intention to use, in relation to the uptake of FinTech services.

It is essential to recognise and acknowledge the presence of various limitations. The present study investigated the intentions of respondents to adopt FinTech, rather than focusing on their actual behavioural patterns. Comprehending behavioural intention is a crucial, although its ability to precisely reflect real-life behaviour may not be the same. Caution should be exercised when generalising the conclusions of this study, given the data were collected solely from one region in Ghana. The generalizability of the findings to the entire population of SMEs may be limited due to the presence of selection bias and insufficient information regarding the sampling frame. Furthermore, it is worth noting that owner mangers of SMEs from diverse geographical regions within the country may exhibit varying perspectives and responses towards FinTech services. Finally, the proposed model demonstrated an explanatory power of 82.9%, indicating the absence of other predictors and moderating variables. Future research could investigate incorporating these variables in order to provide a comprehensive understanding of the behavioural and adoption intentions towards FinTech services in Ghana, as well as in other developing nations that exhibit comparable features to Ghana.

The current study has enhanced our understanding of the factors that influence the adoption of FinTech among SMEs in emerging economies. The study demonstrates that the adoption of FinTech innovation in developing nations is influenced by the intention to use and the perceived usefulness of the technology. This is particularly relevant in a situation where efforts are being made in developing nations to bridge the gap in technology access. This contribution is vital for advancing the research on financial inclusion and filling a significant knowledge gap.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lexis Alexander Tetteh

Lexis Alexander Tetteh, the corresponding author, is a people-focused individual with a strong desire to inspire and support the development of future generations of dignified transformational leaders through career guidance. He is currently a Lecturer, Department of Accounting of the University of Professional Studies-Accra. He holds a Master of Philosophy Degree Accounting and currently a PhD candidate in Accounting with the University of Ghana. In addition, Lexis Alexander Tetteh is an associate of the Institute of Chartered Accountants, Ghana (ICAG). Public Financial Management Information Systems, Auditing and Assurance, Accounting Education, Sustainability Reporting and Assurance, and Internal Control Systems are among his teaching, research, and consulting interests.

References

- Adamek, J., & Solarz, M. (2023). Adoption factors in digital lending services offered by FinTech lenders. Oeconomia Copernicana, 14(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.24136/oc.2023.005

- Ajzen, I. (2006). Behavioural interventions based on the theory of planned behaviour.

- Akinwale, Y. O., & Kyari, A. K. (2022). Factors influencing attitudes and intention to adopt financial technology services among the end-users in Lagos State, Nigeria. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 14(1), 272–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2020.1835177

- Al‐Maghrabi, T., & Dennis, C. (2011). What drives consumers’ continuance intention to e‐shopping? International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 39(12), 899–926. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590551111183308

- Arseto, D. D., & Soemitra, A. (2022). Analysis of the influence of attitudes and perceptions on decisions to use sharia fintech peer to peer lending in Indonesia with satisfaction as an intervening variable. Reslaj: Religion Education Social Laa Roiba Journal, 4(4), 1000–1009. https://doi.org/10.47467/reslaj.v4i4.1048

- Ayyagari, M., Demirguc-Kunt, A., & Maksimovic, V. (2014). Who creates jobs in developing countries? Small Business Economics, 43(1), 75–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9549-5

- Azlis-Sani, J., Dawal, S. Z. M., & Zakuan, N. (2013). Validity and reliability testing on train driver performance model using a PLS approach. Advanced Engineering Forum, 10, 361–366. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AEF.10.361

- Babbie, E. (2008). The basics of social research. Thomson Wadsworth.

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16, 74–94.

- Balcázar, J. J. M., & Rivas, Á. E. L. (2021). Determining factors of the intention to adopt fintech services by micro and small business owners from Chiclayo, Peru. Journal of Business, Universidad Del Pacífico (Lima, Peru), 13(2), 19–43.

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Burton-Jones, A., & Hubona, G. S. (2006). The mediation of external variables in the technology acceptance model. Information & Management, 43(6), 706–717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2006.03.007

- Carlsson, C., Hyvönen, K., Repo, P., & Walden, P. (2005 Adoption of mobile services across different technologies [Paper presentation].18th Bled eConference: eIntegration in Action, 6(08.06), 2005.

- Chawla, D., & Joshi, H. (2023). Role of mediator in examining the influence of antecedents of mobile wallet adoption on attitude and intention. Global Business Review, 24(4), 609–625. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150920924506

- Chen, L. D. (2008). A model of consumer acceptance of mobile payment. International Journal of Mobile Communications, 6(1), 32–52. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMC.2008.015997

- Chin, W. W. (2010). How to write up and report PLS analyses. Handbook of partial least squares (pp. 655–690). Springer.

- Chuang, L. M., Liu, C. C., & Kao, H. K. (2016). The adoption of Fintech service: TAM perspective. International Journal of Management and Administrative Sciences, 3(7), 1–15.

- Coffie, C. P. K., Hongjiang, Z., Mensah, I. A., Kiconco, R., & Simon, A. E. O. (2021). Determinants of FinTech payment services diffusion by SMEs in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Ghana. Information Technology for Development, 27(3), 539–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2020.1840324

- Contreras Pinochet, L. H., Diogo, G. T., Lopes, E. L., Herrero, E., & Bueno, R. L. P. (2019). Propensity of contracting loans services from FinTech’s in Brazil. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 37(5), 1190–1214. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-07-2018-0174

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

- Des Nations Unies, O. (2018). United Nations E-Government Survey 2018: Gearing E-government to support transformation towards sustainable and resilient societies.

- Dwivedi, Y. K., Rana, N. P., Jeyaraj, A., Clement, M., & Williams, M. D. (2019). Re-examining the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT): Towards a revised theoretical model. Information Systems Frontiers, 21(3), 719–734. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-017-9774-y

- Ebrahim, R., Kumaraswamy, S., & Abdulla, Y. (2021). FinTech in banks: Opportunities and challenges. Innovative Strategies for Implementing Fintech in Banking, 100–109.

- Edo, O. C., Etu, E. E., Tenebe, I., Oladele, O. S., Edo, S., Diekola, O. A., & Emakhu, J. (2023). Fintech adoption dynamics in a pandemic: An experience from some financial institutions in Nigeria during COVID-19 using machine learning approach. Cogent Business & Management, 10(2), 2242985. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2242985

- Ernst & Young Global Limited. (2019). Global fintech adoption index 2019. Retrieved from https://www.ey.com/en_gl/ey-global-fintech-adoption-index

- Gai, K., Qiu, M., & Sun, X. (2018). A survey on FinTech. Journal of Network and Computer Applications, 103, 262–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnca.2017.10.011

- Gefen, D., Karahanna, E., & Straub, D. W. (2003). Trust and TAM in online shopping: An integrated model. MIS Quarterly, 1, 27, 51–90. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036519

- Grabner‐Kräuter, S., & Faullant, R. (2008). Consumer acceptance of internet banking: The influence of internet trust. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 26(7), 483–504. https://doi.org/10.1108/02652320810913855

- Guriting, P., & Oly Ndubisi, N. (2006). Borneo online banking: Evaluating customer perceptions and behavioural intention. Management Research News, 29(1/2), 6–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409170610645402

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Planning, 46(1-2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2013.01.001

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2022). Evaluation of reflective measurement models. In Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (P LS-SEM) Using R (pp. 75–90). Cham: Springer.

- Henderson, R., & Divett, M. J. (2003). Perceived usefulness, ease of use and electronic supermarket use. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 59(3), 383–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1071-5819(03)00079-X

- Henseler, J. (2017). Partial least squares path modeling. Advanced Methods for Modeling Markets, 361–381.

- Hsueh, S. C., & Kuo, C. H. (2017 Effective matching for P2P lending by mining strong association rules [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Industrial and Business Engineering, 30–33. https://doi.org/10.1145/3133811.3133823

- Hu, Z., Ding, S., Li, S., Chen, L., & Yang, S. (2019). Adoption intention of FinTech services for bank users: An empirical examination with an extended technology acceptance model. Symmetry, 11(3), 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11030340

- Huei, C. T., Cheng, L. S., Seong, L. C., Khin, A. A., & Leh Bin, R. L. (2018). Preliminary study on consumer attitude towards Fintech products and services in Malaysia. International Journal of Engineering and Technology (UAE), 7(2), 166–169.

- Huh, H. J., Kim, T. T., & Law, R. (2009). A comparison of competing theoretical models for understanding acceptance behaviour of information systems in upscale hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28(1), 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2008.06.004

- Huong, A., Puah, C. H., & Chong, M. T. (2021). Embrace Fintech in ASEAN: A perception through Fintech adoption index. Research in World Economy, 12(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.5430/rwe.v12n1p1

- Hussein, L. A., Baharudin, A. S., Jayaraman, K., & Kiumarsi, S. H. A. I. A. N. (2019). B2B e-commerce technology factors with mediating effect perceived usefulness in Jordanian manufacturing SMES. Journal of Engineering Science and Technology, 14(1), 411–429.

- Kim, J., Merrill, K., Jr,., & Collins, C. (2021). AI as a friend or assistant: The mediating role of perceived usefulness in social AI vs. functional AI. Telematics and Informatics, 64, 101694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2021.101694

- Kim, Y. J., Chun, J. U., & Song, J. (2009). Investigating the role of attitude in technology acceptance from an attitude strength perspective. International Journal of Information Management, 29(1), 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2008.01.011

- Kleijnen, M., Wetzels, M., & De Ruyter, K. (2004). Consumer acceptance of wireless finance. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 8(3), 206–217. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.fsm.4770120

- Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modelling (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Kosasi, S., Kasma, U., & Susilo, B. (2019 The mediating role of intention to use e-commerce adoption in MSMEs [Paper presentation]. 2019 1st International Conference on Cybernetics and Intelligent System (ICORIS),1, 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICORIS.2019.8874923

- Lestari, D., Darma, D. C., & Muliadi, M. (2020). FinTech and micro, small and medium enterprises development: special reference to Indonesia. Entrepreneurship Review, 1(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.38157/entrepreneurship-review.v1i1.76

- Liang, H., Saraf, N., Hu, Q., & Xue, Y. (2007). Assimilation of enterprise systems: the effect of institutional pressures and the mediating role of top management. MIS Quarterly, 59–87.

- López-Nicolás, C., Molina-Castillo, F. J., & Bouwman, H. (2008). An assessment of advanced mobile services acceptance: Contributions from TAM and diffusion theory models. Information & Management, 45(6), 359–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2008.05.001

- Luarn, P., & Lin, H. H. (2005). Toward an understanding of the behavioural intention to use mobile banking. Computers in Human Behavior, 21(6), 873–891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2004.03.003

- Malhotra, N., Nunan, D., & Birks, D. (2017). Marketing research: An applied approach. Pearson Education Limited.

- Maradung, P. (2013). Factors affecting the adoption of mobile money services in the banking and financial industries of Botswana [Doctoral dissertation].

- Marakarkandy, B., Yajnik, N., & Dasgupta, C. (2017). Enabling internet banking adoption: An empirical examination with an augmented technology acceptance model (TAM). Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 30(2), 263–294. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-10-2015-0094

- Mathwick, C., Malhotra, N., & Rigdon, E. (2001). Experiential value: Conceptualization, measurement and application in the catalog and Internet shopping environment’. Journal of Retailing, 77(1), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(00)00045-2

- McWaters, R. J., Bruno, G., Lee, A., & Blake, M. (2015). The future of financial services: How disruptive innovations are reshaping the way financial services are structured, provisioned and consumed. World Economic Forum, 125, 1–178.

- Meyliana, M., Surjandy, S., Fernando, E., & Anindra, F. (2019). The influencing factors of female passenger background in online transportation with perceived ease of use. ComTech: Computer, Mathematics and Engineering Applications, 10(1), 37–41. https://doi.org/10.21512/comtech.v10i1.5713

- Milian, E. Z., Spinola, M. D. M., & de Carvalho, M. M. (2019). FinTechs: A literature review and research agenda. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 34, 100833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2019.100833

- Miller, R. L., & Brewer, J. D. (Eds.) (2003). The AZ of social research: A dictionary of key social science research concepts. Sage.

- Nugraha, D. P., Setiawan, B., Nathan, R. J., & Fekete-Farkas, M. (2022). FinTech adoption drivers for innovation for SMEs in Indonesia. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 8(4), 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8040208

- Nurqamarani, A. S., Sogiarto, E., & Nurlaeli, N. (2021). Technology adoption in small-medium enterprises based on technology acceptance model: A critical review. Journal of Information Systems Engineering and Business Intelligence, 7(2), 162–172. https://doi.org/10.20473/jisebi.7.2.162-172

- Nurunnisha, G. A. (2020). Effect of perceived ease of use, use fulness, and relative advantage toward FinTech’s consumer acceptance at Bandung SMEs. Prosiding ICoISSE, 1(1), 464–471.

- Nurunnisha, G. A., Rohmattulah, A., Maulansyah, M. R., & Sinaga, O. (2020). Analysis of consumer acceptance factors against FinTech at Bandung SMES. PalArch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology, 17(5), 841–855.

- Purnawirawan, N., De Pelsmacker, P., & Dens, N. (2012a). Balance and sequence in online reviews: How perceived usefulness affects attitudes and intentions. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 26(4), 244–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2012.04.002

- Purnawirawan, N., De Pelsmacker, P., & Dens, N. (2012b). The perceived usefulness of online review sets: The role of balance and presentation order. Advances in Advertising Research, Current Insights and Future Trends, 3, 177–190.

- Putri, G. A., Widagdo, A. K., & Setiawan, D. (2023). Analysis of financial technology acceptance of peer to peer lending (P2P lending) using extended technology acceptance model (TAM). Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 9(1), 100027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joitmc.2023.100027

- Radomir, L., & Moisescu, O. I. (2020). Discriminant validity of the customer-based corporate reputation scale: Some causes for concern. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 29(4), 457–469. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-11-2018-2115

- Rasheed, R., Siddiqui, S. H., Mahmood, I., & Khan, S. N. (2019). Financial inclusion for SMEs: Role of digital micro-financial services. Review of Economics and Development Studies, 5(3), 429–439. https://doi.org/10.26710/reads.v5i3.686

- Ravichandran, K., Bhargavi, K., & Kumar, S. A. (2010). Influence of service quality on banking customers’ behavioural intentions. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 2(4), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v2n4p18