Abstract

Food waste is a global challenge to sustainable development. Nevertheless, there is insufficient research on the issue at the consumption stage, especially in developing countries (e.g., Malaysia). To effectively ameliorate food waste, it is crucial to understand how internal cultural values and external social influences affect food waste reduction. Drawing upon 345 Malaysian respondents, this study finds that religiosity, subjective norm, information publicity and personal norm have important effects on consumers’ intention to reduce food waste. However, materialism does not significantly influence consumers’ food waste behaviour, which is inconsistent with prior research. These findings advanced our understanding of food waste among Malaysian consumers, which provides insights to governments and NGOs on how to solve the food waste challenge.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

Responding to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), there is increasing attention on food waste worldwide from various governments, NGOs and research institutions in recent years (Dhir et al., Citation2020). Nevertheless, it seems that many consumers are not aware of the seriousness of the food waste problem (Gáthy et al., Citation2022). It was reported that each consumer, on average, wasted 95-115kg of food annually in Europe and North America (FAO, Citation2011). On a global scale, about one-third of the world’s annual food production is either lost or wasted, while more than 10% of the world’s population are suffering from hunger on a daily basis (FAO, Citation2019). Moreover, the annual amount of food waste is likely to increase from the current 1.6 billion tons to 2.1 billion tons by the year 2030 without effective interventions (Boston Consulting Group, Citation2018).

Food waste is not just an economic issue, but also a challenge to environmental sustainability (Dolnicar et al., Citation2020). For example, a large quantity of food waste is dumped at landfill sites daily, which generates much greenhouse gas emission, such as methane and carbon dioxide (Jereme et al., Citation2018; Moult et al., Citation2018). Since the food waste disposal system consumes considerable land resources, it pollutes the environment and threatens the well-being of people living in the vicinity of the waste dumping sites (Jereme et al., Citation2018). Given the negative impacts of food waste on global sustainable development, it is necessary to gain a holistic understanding of why consumers waste food and how to encourage them to reduce food waste (Diaz-Ruiz et al., Citation2018). However, relevant research remains scarce at the final consumption stage (Bravi et al., Citation2020). Among consumers, food waste is a rather complex behavior being jointly influenced by a range of cultural and social factors. Aschemann-Witzel et al. (Citation2019) state that there may be synergies, conflicts or trade-offs across these determinant factors, so we must deeply understand the interplay among these factors to properly address consumer’s food waste issue.

Most prior studies mainly focus on consumers from developed countries and regions, but it does not mean that food waste is not a serious problem in developing countries (Papargyropoulou et al., Citation2019). According to UNEP (Citation2021), food waste is very similar among high, upper-middle and lower-middle income countries. Take Malaysia for example, along with the economic development in the past few decades, the living standard has been improved significantly (Zakaria et al., Citation2020), and Malaysian consumers are less likely to worry about food shortages. It was reported that Malaysian consumers generate 16,687.5 tonnes of food waste per day, and this amount is enough to feed 12 million people with three meals (Edward, Citation2018). More seriously, only 5% of food waste is either reused or recycled due to the immaturity of waste management methods, and the rest is dumped at various landfills (Moh & Manaf, Citation2014). Therefore, it is extremely important to reduce food waste in Malaysia. However, it remains largely unclear what factors determine consumers’ food waste behaviors (Long et al., Citation2022).

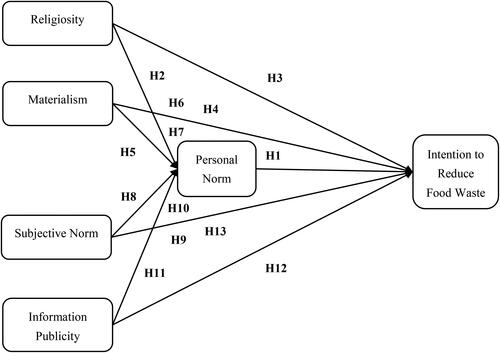

To gain a deep understanding of Malaysian consumers’ food waste behavior, this research proposed a conceptual framework based on the norm activation model (NAM) incorporating internal cultural values (i.e. religiosity and materialism) and external social influences (i.e. subjective norm and information publicity) to examine the interplay between cultural values, social influences and behavioral intention to reduce food waste (see ). Significantly, human behaviours are guided by individuals’ internalized cultural values as a desirable standard towards the external world (Jun et al., Citation2014; Uckan Yuksel & Kaya, Citation2021). Meanwhile, individuals are members of groups, communities and societies, and their behaviours are unavoidably shaped by social factors (Ajzen, Citation2020; Li et al., Citation2021). Therefore, cultural values (i.e. religiosity and materialism) and external social influences (i.e. subjective norm and information publicity) are incorporated to enhance the predictive power of the NAM.

Overall, this research makes contributions to the literature with regard to food waste reduction and other pro-environmental behaviours at the consumption stage in the context of Malaysia, which could facilitate the Malaysian government and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) devising effective measures to mitigate food waste. Specifically, the study addresses three objectives: (1) investigate the influence of internal cultural values (i.e. religiosity and materialism) and external social influences (i.e. subjective norm and information publicity) on personal norms concerning food waste among Malaysian consumers; (2) examine the impacts of cultural values and external social influences on Malaysian consumers’ intention to reduce food waste; and (3) explore the mediating effect of the personal norm on the relationship between cultural values/external social influences and intention to reduce food waste among Malaysian consumers. This study makes considerable contributions to the literature with regard to food waste reduction and other pro-environmental behaviours in the context of Malaysia, which could facilitate the Malaysian government and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) devising effective measures to mitigate food waste.

Literature review

The norm activation model (NAM)

The norm activation model (NAM) is originally proposed by Schwartz (Citation1977), and it is one of the most influential theories used to explain various pro-environmental behaviours (Wang et al., Citation2019). According to the NAM, a pro-environmental behaviour is a result of an individual’s awareness of consequences, ascription of responsibility, and personal norm, and personal norm is a direct predictor of a pro-environmental behaviour. Based on prior studies, pro-environmental behaviours refer to actions conducted by individuals that intend to reduce harmful impacts of their own behaviors on the environment (Steg & De Groot, Citation2010). Given the negative economic, social and environmental impacts of food waste (Dolnicar et al., Citation2020), food waste reduction could be seen as a pro-environmental behaviour. In the literature with regard to altruistic behaviours, NAM has been widely utilized in the fields of sustainable transport (Liu et al., Citation2017), e-waste recycling (Wang et al., Citation2018), organic food (Peštek et al., Citation2018), eco-cruise (Han et al., Citation2019), and food waste prevention (Chun T’ing et al., Citation2021).

According to Schwartz (Citation1977), personal norm (moral obligation) plays a key role in the NAM as it directly influences people’s altruistic behaviors. Personal norm may be described as a feeling that an individual is morally obligated to perform or not perform specific actions (Schwartz & Howard, Citation1981). Therefore, personal norm determines whether an individual should participate in pro-environmental behavior (Han et al.,, 2016). The positive relationship between personal norm and pro-environmental behavior has been frequently verified by previous studies (Han et al., Citation2016; Han et al., Citation2019; Peštek et al., Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2018). For example, Liu et al. (Citation2017) examined Chinese consumers’ sustainable transport behavior, and they concluded that people with a higher level of the personal norm are more likely to reduce car travel. Khan et al. (Citation2022) found that personal norms positively influence Pakistani consumers’ sustainable consumption of organic food. In the context of food waste, Chun T’ing et al. (Citation2021) investigated Malaysian consumers’ intention to reduce food waste, and their findings confirm that personal norm is significantly correlated with altruistic behavioral intention (Kim et al., Citation2020). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Personal norm positively influences intention to reduce food waste among Malaysian consumers.

Religiosity and food waste reduction

Religion, as an important component of culture, affects individuals’ social behaviors for a large population in the world (Agarwala et al., Citation2019). In literature, religion is a broad and multi-dimensional concept that consists of beliefs, rituals, values, and community (Mathras et al., Citation2016). Significantly, religion influences people’s food consumption behaviors through religious codes and traditions (Bailey & Sood, Citation1993; Minton et al., Citation2020). However, directly discussing religious affiliation or rituals can be culturally-inappropriate and very sensitive in some Muslim communities (Elhoushy & Jang, Citation2021). Malaysia, as a culturally and ethnically diverse country, has followers of all major religions, so it is unreasonable to use a certain religious affiliation to represent Malaysian consumers (Fernandez & Coyle, Citation2019). Besides, it is believed that religiosity represents the centrality of religion in one’s life (Mathras et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, some researchers argue that religiosity (religious values) has a stronger predictive power on consumers’ attitudes and behaviors than a religious affiliation in the recent two decades (Agarwala et al., Citation2019; Choi, Citation2010; Elhoushy & Jang, Citation2021). Therefore, this research decided to investigate the effect of religiosity, reflecting one’s commitment to comply with religious teachings and practices, rather than religion on Malaysian consumers’ intention to reduce food waste.

Religiosity (religious values) is defined as ‘the degree in which an individual adheres to his or her religious values, beliefs, and practices, and uses these in daily living’ (Worthington et al., Citation2003, p. 85). With regard to social behaviors, religious individuals tend to behave in line with the guidelines and restrictions that are set by their religions, while religious codes are less influential for people who have a low level of religiosity (Wang et al., Citation2020). According to prior studies, religiosity imposes a strong influence on consumers’ attitudinal and behavioral outcomes (Agarwala et al., Citation2019), which is generally universal regardless of religious affiliation (Cleveland et al., Citation2013).

Significantly, religiosity takes effect in contexts where ethical issues are involved (Bhuian et al., Citation2018; Vitell et al., Citation2018). Thus, it is often discussed in relation to pro-environmental behaviors. For example, Wang et al. (Citation2020) examined Chinese consumers’ intention to choose green hotels, and they found that religiosity positively influences attitude and behavioral intention to patronize green hotels. With regard to food waste, major religions, such as Islam and Christianity, promote values and beliefs against wastefulness (Yoreh & Scharper, Citation2020). Abdelradi (Citation2018) found that religious beliefs positively influence consumers’ environmental awareness, and consequently influence food waste behaviors. Specifically, Elhoushy and Jang (Citation2021) concluded that religiosity has a positive impact on the intention to reduce food waste via personal norm. However, Filimonau et al. (Citation2022) revealed that religiosity only has limited effect on consumers’ food waste behaviors at home and away. To clarify the inconsistency, further investigation is needed. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2: Religiosity positively influences personal norms to reduce food waste among Malaysian consumers.

H3: Religiosity positively influences intention to reduce food waste among Malaysian consumers.

H4: Personal norm mediates the positive relationship between religiosity and intention to reduce food waste among Malaysian consumers.

Materialism and food waste reduction

Materialism (materialistic values) is defined as a set of values or goals reflecting the importance of acquiring wealth, possessions and status for an individual (Hurst et al., Citation2013; Kasser, Citation2016), which could be seen as a substitute for consumerism (Diaz-Ruiz et al. Citation2018). Thus, materialists mainly evaluate themselves and others by consumption patterns. Based on prior studies, materialism has a negative influence on a variety of attitudes, norms and intentions related to pro-environmental behaviors (Alzubaidi et al., Citation2021; Diaz-Ruiz et al., Citation2018; Gatersleben et al., Citation2018; Gu et al., Citation2020). According to a mega-analysis research conducted by Hurst et al. (Citation2013), materialism is negatively correlated with pro-environmental behaviors as it is usually associated with self-indulgence and over-consumption (Hynes & Wilson, Citation2016). Materialistic consumers are inclined to gain happiness through consumption, and are not likely to feel morally obligated to restrain their desire for excessive consumption. Besides, materialists have a low altruistic attitude toward the environment (Gu et al., Citation2020). As a result, they are less likely to participate in pro-environmental activities, such as recycling and water conservation (Alzubaidi et al., Citation2021; Gu et al., Citation2020; Kilbourne & Pickett, Citation2008). Nevertheless, it should be noted that there are contradicting results with regard to the correlation between materialism and pro-environmental behaviours (Tu et al., Citation2023), and the inconsistency requires further examination.

Most prior studies are conducted based on consumers from developed countries (Gatersleben et al., Citation2018). Thus, it is noteworthy to see that materialism is quickly growing among consumers from developing countries (Kilbourne & Pickett, Citation2008). For example, Zakaria et al. (Citation2020) examined Malaysian millennials’ conspicuous consumption behaviors, and it was found that materialism has a positive effect on conspicuous consumption. With regard to food waste, Diaz-Ruiz et al. (Citation2018) state that materialism negatively influences environment concerns and food waste reduction. In addition, Kim et al. (Citation2020) argue that personal norm is directly shaped by values, and it could be considered a moral attitude in the context of food waste. Significantly, the NAM model states that external value influences one’s actual behaviours through their influence on that individual’s personal norm that is defined as one’s own beliefs and self-concept (Hynes & Wilson, Citation2016; Schwartz, Citation1977). Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H5: Materialism negatively influences personal norm to reduce food waste among Malaysian consumers.

H6: Materialism negatively influences intention to reduce food waste among Malaysian consumers.

H7: Personal norm mediates the negative relationship between materialism and intention to reduce food waste among Malaysian consumers.

Subjective norm and food waste reduction

The norm activation model (NAM) is chosen as the foundation of the research framework due to its effectiveness to explain pro-environmental behaviour. However, the NAM has been criticized for overestimating internalized personal norm and underestimating external social factors (Liao et al., Citation2018). It is widely acknowledged that an individual’s consumption behaviours are affected by some social factors, such as social norm (Zhang & Dong, Citation2020). Therefore, subjective norm is added to the research framework to enhance the effectiveness of the NAM.

Subjective norm is a typical representation of external social influences, and it refers to an individual’s perceived external pressure from important referents (e.g. family members, close friends and communities) on whether to perform specific behaviors (Ajzen, Citation2020). People value opinions from their referent groups because of either trust or conformity to established social norms (Zhang et al., Citation2020). On the contrary, personal norm, as an internalized belief, is a feeling or moral obligation to conduct a certain behavior (Schwartz, Citation1977). Based on the definitions of the two concepts, subjective norm and personal norm are different, and the formation of personal norm is shaped by external social factors (Liao et al., Citation2018; Long et al., Citation2022).

In collectivist societies, such as Malaysia, individuals are encouraged to conform to subjective norm (Bond & Smith, Citation1996). In addition, Trommsdorff (Citation2010) states that Asians were brought up to compromise their own preferences to comply with their referent groups, and their attitude formation is shaped by subjective norm (Bananuka et al., Citation2019). Thus, Malaysian consumers are likely to reduce food waste if they perceive associated social pressure. Nevertheless, Coşkun & Özbük (Citation2020), Tsai et al. (Citation2020) and some other scholars concluded that subjective norm has no significant effect on intention to reduce food waste because personal norm (attitude) plays a more important role in influencing behavior choices (Zhang et al., Citation2019, Citation2020, Citation2021). The inconsistent findings from prior studies indicate a necessity to further examine the relationship between subjective norm and intention to reduce food waste, especially in a developing country context. Based on the above discussion, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H8: Subjective norm positively influences personal norm to reduce food waste among Malaysian consumers.

H9: Subjective norm positively influences intention to reduce food waste among Malaysian consumers.

H10: Personal norm mediates the positive relationship between subjective norm and intention to reduce food waste among Malaysian consumers.

Information publicity and food waste reduction

Information publicity is considered an important component of external social influences in environmental protection (Fouad et al., Citation2021; Jiang et al., Citation2021), and it refers to all forms and types of available information related to food waste in the current research context (Wang et al., Citation2019). Some prior studies indicate that information publicity can significantly influence consumers’ pro-environmental behavioral intention (Li et al., Citation2021; Xu et al., Citation2017). For example, Zhang et al. (Citation2020) found that information publicity directly affects residents’ waste classification behavior, and they further argued that residents may question the necessity of waste classification if they do not receive complete and clear information about this pro-environmental behavior. Similarly, consumers probably will not take actions to reduce food waste unless they are fully aware of the food waste problem and methods to reduce food waste (Tsai et al., Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2019; Zhang et al., Citation2021). Meanwhile, some researchers believe that information publicity affects pro-environmental behavioral intentions indirectly via personal norm/attitude (Wang et al., Citation2018). Given the discussion above, the following hypotheses are postulated:

H11: Information publicity positively influences personal norm to reduce food waste among Malaysian consumers.

H12: Information publicity positively influences intention to reduce food waste among Malaysian consumers.

H13: Personal norm mediates the positive relationship between information publicity and intention to reduce food waste among Malaysian consumers.

Methodology

A convenience sampling technique was used by this research. The questionnaire was presented at Google Forms (Lu et al., Citation2018), and open for potential respondents from 12 September to 12 October, 2021. During the four weeks, a digital invitation letter with the survey link was distributed to 1,500 potential respondents via email and social media platforms (e.g. Facebook and WhatsApp). The invitation letter briefly explains the research, and it explicitly mentions that only Malaysian citizens who currently live in Malaysia are eligible for filling up the survey. To further ensure that the respondents are eligible for the survey, a filter question is added asking whether the respondent is a Malaysian citizen currently living in Malaysia. All respondents were aware that they were participating in academic research anonymously. By the end of October 2021, 352 responses had been successfully collected, and seven of them were excluded because those respondents didn’t pass the filter question.

The rationale to select Malaysia as the study’s context is that most previous studies focus on consumers from developed countries and regions, but it does not mean that food waste is not a serious problem in developing countries (Papargyropoulou et al., Citation2019). However, food waste is also a serious issue in many developing countries (Papargyropoulou et al., Citation2019). As per a report released by the United Nations Environment Programme, food waste issue is similar among high, upper-middle and lower-middle income countries (UNEP). Malaysia is a typical upper-middle income country with serious food waste issue (Edward, Citation2018; Moh & Manaf, Citation2014), and relevant research on consumers from developing countries is relatively scarce. Besides, Malaysia is a culturally and ethnically diverse country, and it has followers of all major religions, which makes Malaysia a suitable context to examine to role of religiosity to food waste. Thus, this study decided to choose Malaysia as research context.

With regard to the measurement of the research, all items are adopted from prior studies mainly focusing on pro-environmental behaviors. The questionnaire was arranged with four sections. The first section contains ten items from Bhuian et al. (Citation2018) measuring religiosity and four items from Diaz-Ruiz et al. (Citation2018) measuring materialism. The second section includes four items taken from Wang and Zhang (Citation2020) measuring personal norm. The third section contains five questions in relation to demographic information. At last, the fourth section has four items taken from Aktas et al. (Citation2018) measuring consumers’ intention to reduce food waste. This study collects data from a single source, which may generate common method bias. To reduce the impact of common method bias, the authors placed a demographic information section between the predictive variables and the criterion variable (Podsakoff et al., Citation2012). Moreover, Podsakoff et al. (Citation2012) suggest using different Likert scales to predictive and criterion variables for the sake of minimizing common method bias as well. Thus, a 7-point Likert scale is assigned to the predictive variables, and a 5-point Likert scale is assigned to the criterion variable.

Although all the measurement items are adopted from relevant studies, five Malaysian consumers were invited to participate in a small-scale pretest before the distribution of the questionnaire to make sure that potential respondents can easily and correctly understand the questions (Dillman, Citation2011). According to the five respondents’ feedback, the questionnaire was well designed, and potential respondents are unlikely to misunderstand the measurement items. Nevertheless, slight modifications were made for a couple of items in relation to wording. The modified version was checked by another scholar who is adept at research design, and no issues were found.

Data analysis

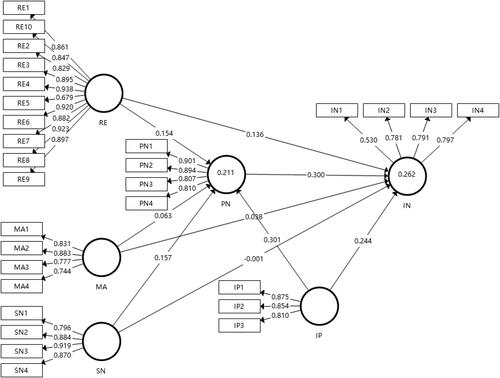

To test the proposed hypotheses, this research adopted partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), and software SmartPLS 3.3.3 for data analysis (Hair et al., Citation2017). The authors followed Hair et al. (Citation2017) to examine the measurement and structural models of the research. Thus, reliability, validity, lateral collinearity, path coefficient, coefficient of determination, effect size and predictive relevance were checked respectively (see ).

As shown in , the loading values of all items are greater than 0.4 and their associated AVE values are greater than 0.5. Therefore, the indicator reliability is confirmed (Hulland, Citation1999). With regard to internal consistency, this research referred to rho_A because Cronbach’s alpha and Composite Reliability (CR) tend to underestimate and overestimate the reliability, and rho_A usually lies between Cronbach’s alpha and CR (Dijkstra & Henseler, Citation2015). All the rho_A values range between 0.70 and 0.95, so the research’s internal consistency is confirmed (Hair et al., Citation2019). Meanwhile, all the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) values are less than the threshold at 0.90 (see ), which indicates adequacy of discriminant validity (Gold et al., Citation2001). Based on the results above, the measurement model of the research is established.

Table 1. Assessment results of measurement model.

Table 2. Discriminant validity.

Although vertical collinearity issue is ruled out by the HTMT values (see ), lateral collinearity issue (predictor-criterion collinearity) may still exist (Kock & Lynn, Citation2012). Therefore, this research examined Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). As shown in , all VIF values are no more than 3.3, so lateral collinearity issue is also ruled out (Diamantopoulos & Siguaw, Citation2006).

Table 3. Variance Inflation Factor.

To confirm the structural model, beta value, t-value, p-value, confidence intervals, coefficient of determination (R2), effect size (f2) and predictive relevance (Q2) were assessed (Hair et al., Citation2017). As shown in , H1, H2, H3, H8, H11 and H12 are supported with small effect sizes, H5, H6 and H9 are rejected. That is, religiosity, subjective norm and information publicity have a significant effect on personal norm; religiosity, information publicity and personal norm have a significant effect on intention to reduce food waste. With regard to the mediating effect of personal norm, H4, H10 and H13 are supported, H7 is rejected (see ). That is, personal norm mediates the positive relationship between religiosity/subjective norm/information publicity and behavioral intention. Besides, the R2 value of personal norm and behavioral intention is 0.211 and 0.262 respectively, indicating a moderate and substantial level of predictive accuracy of the model on personal norm and behavioral intention (Cohen, Citation1988). At last, the Q2 value of personal norm and behavioral intention is higher than 0, indicating that the structural model has a predictive relevance on the two latent variables (Hair et al., Citation2017).

Table 4. Results summary of hypothesis testing.

Table 5. Results summary of mediation testing.

Discussion and conclusion

This research aims to gain a holistic understanding of food waste prevention at consumption stage by examining the interplay of internal cultural values (i.e. religiosity and materialism), external social influences (i.e. subjective norm and information publicity), personal norm and intention to reduce food waste. To do this, the research collected and analyzed data from 345 Malaysian consumers via online survey.

The results of the research indicate that personal norm (moral attitude) has the strongest impact on consumers’ intention to reduce food waste in the proposed framework. This finding suggests that a consumer is very likely to avoid food waste behaviors if the consumer feels morally obligated to prevent food waste (Schwartz, Citation1977). Besides, eating behaviors are also influenced by religiosity and information publicity, implying that a consumer tends to avoid food waste if the consumer is highly religious and has access to sufficient information on food waste prevention.

With regard to the formation of personal norm, it is mutually shaped by information publicity, subjective norm and religiosity (Wang et al., Citation2019; Yoreh & Scharper, Citation2020; Zhang & Dong, Citation2020). Significantly, information publicity has the highest significant effect on personal norm, implying that a consumer is inclined to feel morally obligated to reduce food waste if the consumer has received much information on food waste prevention. Additionally, religious values and opinions from others also facilitate the formation of a consumer’s moral obligation towards food waste prevention.

Furthermore, personal norm mediates the relationship between religiosity, information publicity and subjective norm and intention to reduce food waste. That is, religiosity and information publicity affect eating behaviors directly and indirectly via personal norm, and subjective norm only has an indirect effect on intention to reduce food waste via personal norm. These findings suggest the centrality of personal norm in the extended norm activation model (NAM). Meanwhile, materialism has neither direct nor indirect effect on eating behaviors among Malaysian consumers, which is inconsistent with the findings of some previous studies, such as Alzubaidi et al. (Citation2021) and Gu et al. (Citation2020). Overall, both internal cultural values and external social influences should be considered in relation to pro-environmental attitudes (personal norm) and behaviors.

Theoretical contributions

This research makes several theoretical contributions as follows. The extended NAM is valid in predicting consumers’ personal norm and behavioral intention towards food waste reduction in the context of Malaysia. The current study verifies that religiosity, subjective norm, information publicity are significant factors to reduce food waste, and personal norm plays a mediating role in the framework. It is noteworthy to note that materialism does not negatively influence personal norm or behavioral intention as previous studies suggested. Our findings expand the relevant literature on religiosity, information publicity, subjective norm and eating behaviors in the context of Malaysia, and help address food waste challenges in a developing country of cultural, religious and ethnic diversity. In general, this research adds new insights to the pro-environmental behavior literature, especially about food waste prevention.

The results suggest that religiosity, information publicity and subjective norm significantly influences personal norm, and the first two factors also have a significant effect on intention to reduce food waste (Elhoushy & Jang, Citation2021; Li et al., Citation2021). These findings indicate that external social influences (i.e. information publicity and subjective norm) and religiosity (religious values) could activate Malaysian consumers’ personal norm toward food waste. In other words, an individual’s personal norm is mutually shaped by external social factors and obtained religious values (Yoreh & Scharper, Citation2020; Zhang & Dong, Citation2020). Moreover, the activated personal norm has a significant impact on their behavioral intention to reduce food waste, which implies Malaysian consumers tend to reduce food waste when they feel morally obliged to avoid food waste (Wang et al., Citation2019). The findings facilitate us understanding how to form favorable personal norm and behavioral intention toward food waste at the consumption stage.

With regard to information publicity, it is confirmed that it could effectively improve Malaysian consumers’ behavioral intention to reduce food waste (Wang et al., Citation2019). Along with the rapid development of information technology, social media is becoming more and more popular among consumers, so their purchase styles and consumption patterns are more likely to be influenced by social media influencers (Tu et al., Citation2023). However, the results, out of expectation, indicate that materialism does not significantly influence personal norm or intention to reduce food waste, which contradict some prior studies (Alzubaidi et al., Citation2021; Gu et al., Citation2020; Kilbourne & Pickett, Citation2008). The inconsistency highlights the urgent necessity to explore the mechanism of how materialism influences food waste reduction and other pro-environmental behaviors. Although previous research indicates that materialists are less likely to participate in pro-environmental behaviors as they have relatively low altruistic attitude toward the environment (Gu et al., Citation2020), it remains unclear whether other psychological factors, such as egoism and symbolic values, affect materialistic consumers’ consumption behaviors (Tu et al., Citation2023). Thus, there might be other valid mediators regarding the relationship between materialism and intention to reduce food waste.

Another theoretical contribution is that the research identified the mediating role of personal norm in the extended NAM. It is found that the relationship between religiosity, information publicity, subjective norm and behavioral intention is mediated by personal norm. As prior studies suggest, religiosity and information publicity influence intention to reduce food waste directly and indirectly (Abdelradi, Citation2018; Elhoushy & Jang, Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2020). In contrast, subjective norm, it has a significant effect on personal norm but not on eating behaviors, which supports Tsai et al. (Citation2020)’s conclusion that personal norm is much more important than subjective norm towards food waste (Zhang et al., Citation2021). Malaysian consumers, living in a collectivist society, value opinions from their referent groups, but they tend to view the behavior of food consumption as a personal choice. Nevertheless, their personal norm (moral attitude) towards food is inevitably influenced by established social norms (Bananuka et al., Citation2019). Based on these findings, our understanding of norm activation theory is advanced in the context of food waste.

Managerial implications

This research also provides some practical implications to policy makers and civil society organizations concerning food waste reduction at consumption stage in Malaysia. Food waste is a growing environmental challenge in developing countries, and it is crucial to understand how cultural values and social influences affect consumers’ personal norm (moral attitude) and willingness to reduce food waste. First, religious groups should take responsibility to reduce food waste as their believers’ consumption behaviors are influenced by religious codes and traditions (Minton et al., Citation2020). Major religions, such as Islam and Christianity, all provide moral frameworks to prevent wastefulness (Yoreh & Scharper, Citation2020), and they could highlight these imperatives to convince their believers not to waste food. When consumers are fully aware of these moral frameworks from their affiliated religions, they are likely to form strong personal norm and intention to avoid food waste (Bailey & Sood, Citation1993).

Similarly, governments and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) should take necessary measures to spread useful information on food waste (Fouad et al., Citation2021). Some consumers may waste food because they have not received sufficient information on food waste and how to effectively reduce food waste (Tsai et al., Citation2020; Zhang et al., Citation2021). Significantly, the effect of information publicity on personal norm is stronger than either religiosity or subjective norm on personal norm (see effect size in ), which indicates the crucial role of information publicity in addressing food waste problem in Malaysia. Thus, the Malaysian government and relevant NGOs are advised to launch campaigns to increase public awareness about food waste through both traditional channels and social media (Li et al., Citation2021). Only when most Malaysian consumers realize the food waste problem, will food waste reduction/avoidance become a widely recognized social norm in Malaysian society. Then, the established social norm of reducing/avoiding food waste will further enhance consumers’ personal norm and willingness to reduce food waste (Coşkun & Özbük, Citation2020). Although materialism does not affect personal norm and intention to reduce food waste in this research, Malaysian government and NGOs should discourage consumers from excessive consumption via information publicity as many previous studies indicate that materialism is correlated with food waste.

Limitations and future research directions

Regardless of the theoretical and practical contributions, this research has a few limitations. First, the research identified religiosity, materialism, subjective norm and information publicity as representative cultural values and social influences, but other factors, such as perceived behavioral control, may be important in affecting Malaysian consumers’ food waste (reduction) behaviors (Ajzen, Citation2020; Chun T’ing et al., Citation2021). Second, this study collected data through online surveys and the respondents may have understated their level of materialism and overstated their willingness to reduce food waste due to social desirability. Thus, future research is suggested to use other methods to collect data rather than self-reported surveys (Giordano et al., Citation2018). Third, this research only collected data from Malaysian consumers, so it should be cautious to generalize the findings of this study, especially in contexts very different from Malaysia. Future research could examine this framework in other developing countries to confirm the findings for the purpose of generalization. At last, future studies are advised to extend the proposed framework to actual food waste reduction behavior because consumers’ behavior may not always be consistent with behavioral intention (Ajzen, Citation2020).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Fei Long

Fei Long received his PhD from the National University of Malaysia (UKM) after 6 years of corporate experiences in marketing and communications. He is currently a Lecturer of Tourism Management at the Business School, Guangdong Ocean University. His research focuses on Chinese outbound tourism, cross-cultural communications and ASEAN studies.

Norzalita Abd Aziz

Norzalita Abd Aziz is a Professor of Marketing at the UKM-Graduate School of Business. She continues her career at National University of Malaysia (UKM) after 6 years of corporate experience in marketing in a multifaceted conglomerate and has more than 25 years of experience in teaching and researching in UKM.

Kei Wei Chia

Kei Wei Chia is a senior lecturer in the School of Hospitality, Tourism & Events, Taylor’s University, Malaysia. He completed his PhD at Universiti Putra Malaysia. His current research interests are in the areas of island tourism, rural tourism, tourism management, and sustainable tourism.

Huan Zhang

Huan Zhang now serves as an Associate Professor at the Business School of Guangdong Ocean University and are pursuing a doctoral degree in Hotel and Tourism Management of Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Her research areas include cultural heritage and rural tourism.

References

- Abdelradi, F. (2018). Food waste behaviour at the household level: A conceptual framework. Waste Management (New York, N.Y.), 71, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2017.10.001

- Agarwala, R., Mishra, P., & Singh, R. (2019). Religiosity and consumer behavior: A summarizing review. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 16(1), 32–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2018.1495098

- Ajzen, I. (2020). The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2(4), 314–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.195

- Aktas, E., Sahin, H., Topaloglu, Z., Oledinma, A., Huda, A. K. S., Irani, Z., Sharif, A. M., Van’t Wout, T., & Kamrava, M. (2018). A consumer behavioural approach to food waste. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 31(5), 658–673. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-03-2018-0051

- Alzubaidi, H., Slade, E. L., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2021). Examining antecedents of consumers’ pro-environmental behaviours: TPB extended with materialism and innovativeness. Journal of Business Research, 122, 685–699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.01.017

- Aschemann-Witzel, J., Giménez, A., & Ares, G. (2019). Household food waste in an emerging country and the reasons why: Consumer’s own accounts and how it differs for target groups. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 145, 332–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.03.001

- Bailey, J. M., & Sood, J. (1993). The effects of religious affiliation on consumer behavior: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Managerial Issues, 5(3), 328–352.

- Bananuka, J., Kasera, M., Najjemba, G. M., Musimenta, D., Ssekiziyivu, B., & Kimuli, S. N. L. (2019). Attitude: mediator of subjective norm, religiosity and intention to adopt Islamic banking. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 11(1), 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-02-2018-0025

- Bhuian, S. N., Sharma, S. K., Butt, I., & Ahmed, Z. U. (2018). Antecedents and pro-environmental consumer behavior (PECB): The moderating role of religiosity. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 35(3), 287–299. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-02-2017-2076

- Bond, R., & Smith, P. B. (1996). Culture and conformity: A meta-analysis of studies using Asch’s (1952b, 1956) line judgment task. Psychological Bulletin, 119(1), 111–137. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.119.1.111

- Boston Consulting Group. (2018). Tackling the 1.6-Billion-Ton food loss and waste crisis. https://www.bcg.com/publications/2018/tackling-1.6-billion-ton-food-loss-and-wastecrisis

- Bravi, L., Francioni, B., Murmura, F., & Savelli, E. (2020). Factors affecting household food waste among young consumers and actions to prevent it. A comparison among UK, Spain and Italy. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 153, 104586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104586

- Choi, Y. (2010). Religion, religiosity, and South Korean consumer switching behaviors. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 9(3), 157–171. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.292

- Chun T’ing, L., Moorthy, K., Gunasaygaran, N., Sek Li, C., Omapathi, D., Jia Yi, H., Anandan, K., & Sivakumar, K. (2021). Intention to reduce food waste: a study among Malaysians. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association (1995), 71(7), 890–905. https://doi.org/10.1080/10962247.2021.1900001

- Cleveland, M., Laroche, M., & Hallab, R. (2013). Globalization, culture, religion, and values: Comparing consumption patterns of Lebanese Muslims and Christians. Journal of Business Research, 66(8), 958–967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.12.018

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum.

- Coşkun, A., & Özbük, R. M. Y. (2020). What influences consumer food waste behavior in restaurants? An application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Waste Management (New York, N.Y.), 117, 170–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2020.08.011

- Dhir, A., Talwar, S., Kaur, P., & Malibari, A. (2020). Food waste in hospitality and food services: a systematic literature review and framework development approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 270, 122861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122861

- Diamantopoulos, A., & Siguaw, J. A. (2006). Formative versus reflective indicators in organizational measure development: A comparison and empirical illustration. British Journal of Management, 17(4), 263–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2006.00500.x

- Diaz-Ruiz, R., Costa-Font, M., & Gil, J. M. (2018). Moving ahead from food-related behaviours: An alternative approach to understand household food waste generation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 172, 1140–1151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.10.148

- Dijkstra, T. K., & Henseler, J, University of Groningen. (2015). Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Quarterly, 39(2), 297–316. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2015/39.2.02

- Dillman, D. A. (2011). Mail and Internet surveys: The tailored design method–2007 Update with new Internet, visual, and mixed-mode guide. John Wiley & Sons.

- Dolnicar, S., Juvan, E., & Grün, B. (2020). Reducing the plate waste of families at hotel buffets – A quasi-experimental field study. Tourism Management, 80, 104103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104103

- Edward, O. T. (2018). Tackling food waste with innovation. https://www.nst.com.my/opinion/letters/2018/11/432303/tackling-food-wastage-innovation

- Elhoushy, S., & Jang, S. (. (2021). Religiosity and food waste reduction intentions: A conceptual model. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(2), 287–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12624

- FAO. (2011). Global Food Losses and Food Waste. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome. http://www.fao.org/3/i2697e/i2697e.pdf

- FAO. (2019). Food loss and food waste. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome. http://www.fao.org/3/ca6030en/ca6030en.pdf

- Fernandez, E. F., & Coyle, A. (2019). Sensitive issues, complex categories, and sharing festivals: Malay Muslim students’ perspectives on interfaith engagement in Malaysia. Political Psychology, 40(1), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12501

- Filimonau, V., Kadum, H., Mohammed, N. K., Algboory, H., Qasem, J. M., Ermolaev, V. A., & Muhialdin, B. J. (2022). Religiosity and food waste behavior at home and away. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 31(7), 797–818. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2022.2080145

- Fouad, T. Z., Chang, C. H., & Huang, Y. C. (2021). The influence of media exposure and trust on youth attitude towards greener Tainan. International Journal of Innovation and Sustainable Development, 15(4), 416–437. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJISD.2021.118376

- Gatersleben, B., Jackson, T., Meadows, J., Soto, E., & Yan, Y. L. (2018). Leisure, materialism, well-being and the environment. European Review of Applied Psychology, 68(3), 131–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2018.06.002

- Gáthy, A. B., Soltész, A. K., & Szűcs, I. (2022). Sustainable consumption – examining the environmental and health awareness of students at the University of Debrecen. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2105572. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2105572

- Giordano, C., Piras, S., Boschini, M., & Falasconi, L. (2018). Are questionnaires a reliable method to measure food waste? A pilot study on Italian households. British Food Journal, 120(12), 2885–2897. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-02-2018-0081

- Gold, A. H., Malhotra, A., & Segars, A. H. (2001). Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 185–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2001.11045669

- Gu, D., Gao, S., Wang, R., Jiang, J., & Xu, Y. (2020). The negative associations between materialism and pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors: individual and regional evidence from China. Environment and Behavior, 52(6), 611–638. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916518811902

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hair, J. F., Thomas, G., Hult, M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Han, H., Hwang, J., Lee, M. J., & Kim, J. (2019). Word-of-mouth, buying, and sacrifice intentions for eco-cruises: Exploring the function of norm activation and value-attitude-behavior. Tourism Management, 70, 430–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.09.006

- Han, H., Jae, M., & Hwang, J. (2016). Cruise travelers’ environmentally responsible decision-making: An integrative framework of goal-directed behavior and norm activation process. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 53, 94–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.12.005

- Hulland, J. (1999). Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strategic Management Journal, 20(2), 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199902)20:2<195::AID-SMJ13>3.0.CO;2-7

- Hurst, M., Dittmar, H., Bond, R., & Kasser, T. (2013). The relationship between materialistic values and environmental attitudes and behaviors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 36, 257–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.09.003

- Hynes, N., & Wilson, J. (2016). I do it, but don’t tell anyone! Personal values, personal and social norms: Can social media play a role in changing pro-environmental behaviours? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 111, 349–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.06.034

- Jereme, I. A., Siwar, C., Begum, R. A., Talib, B. A., & Choy, E. A. (2018). Analysis of household food waste reduction towards sustainable food waste management in Malaysia. The Journal of Solid Waste Technology and Management, 44(1), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.5276/JSWTM.2018.86

- Jiang, P., Van Fan, Y., & Klemeš, J. J. (2021). Data analytics of social media publicity to enhance household waste management. Resources, Conservation, and Recycling, 164, 105146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105146

- Jun, J., Kang, J., & Arendt, S. W. (2014). The effects of health value on healthful food selection intention at restaurants: Considering the role of attitudes toward taste and healthfulness of healthful foods. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 42, 85–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.06.002

- Kasser, T. (2016). Materialistic values and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 67(1), 489–514. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033344

- Khan, K., Iqbal, S., Riaz, K., & Hameed, I. (2022). Organic food adoption motivations for sustainable consumption: moderating role of knowledge and perceived price. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2143015. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2143015

- Kilbourne, W., & Pickett, G. (2008). How materialism affects environmental beliefs, concern, and environmentally responsible behavior. Journal of Business Research, 61(9), 885–893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.09.016

- Kim, M. J., Hall, C. M., & Kim, D. K. (2020). Predicting environmentally friendly eating out behavior by value-attitude-behavior theory: does being vegetarian reduce food waste? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(6), 797–815. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1705461

- Kock, N., & Lynn, G, Texas A&M International University. (2012). Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 13(7), 546–580. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00302

- Li, C., Wang, Y., Li, Y., Huang, Y., & Harder, M. K. (2021). The incentives may not be the incentive: A field experiment in recycling of residential food waste. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 168, 105316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105316

- Liao, C., Hong, J., Zhao, D., Zhang, S., & Chen, C. (2018). Confucian culture as determinants of consumers’ food leftover generation: evidence from Chengdu, China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 25(15), 14919–14933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-018-1639-5

- Liu, Y., Sheng, H., Mundorf, N., Redding, C., & Ye, Y. (2017). Integrating norm activation model and theory of planned behavior to understand sustainable transport behavior: Evidence from China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(12), 1593. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14121593

- Long, F., Ooi, C. S., Gui, T., & Ngah, A. H. (2022). Examining young Chinese consumers’ engagement in restaurant food waste mitigation from the perspective of cultural values and information publicity. Appetite, 175, 106021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2022.106021

- Lu, Z., Zhang, H., Luoto, S., & Ren, X. (2018). Gluten-free living in China: The characteristics, food choices and difficulties in following a gluten-free diet–An online survey. Appetite, 127, 242–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.05.007

- Mathras, D., Cohen, A. B., Mandel, N., & Mick, D. G. (2016). The effects of religion on consumer behavior: A conceptual framework and research agenda. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 26(2), 298–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2015.08.001

- Minton, E. A., Johnson, K. A., Vizcaino, M., & Wharton, C. (2020). Is it godly to waste food? How understanding consumers’ religion can help reduce consumer food waste. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 54(4), 1246–1269. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12328

- Moh, Y. C Manaf, & A., L. (2014). Overview of household solid waste recycling policy status and challenges in Malaysia. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 82, 50–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2013.11.004

- Moult, J. A., Allan, S. R., Hewitt, C. N., & Berners-Lee, M. (2018). Greenhouse gas emissions of food waste disposal options for UK retailers. Food Policy. 77, 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2018.04.003

- Papargyropoulou, E., Steinberger, J. K., Wright, N., Lozano, R., Padfield, R., & Ujang, Z. (2019). Patterns and causes of food waste in the hospitality and food service sector: food waste prevention insights from Malaysia. Sustainability, 11(21), 6016. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216016

- Peštek, A., Agic, E., & Cinjarevic, M. (2018). Segmentation of organic food buyers: An emergent market perspective. British Food Journal, 120(2), 269–289. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-04-2017-0215

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

- Schwartz, S. H. (1977). Normative influences on altruism. In Leonard, B. (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Academic Press.

- Schwartz, S. H., & Howard, J. A. (1981). A normative decision-making model of altruism. In Rushton, J. P., Sorrentino, R. M. (Eds.), Altruism and Helping Behavior. Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Steg, L., & De Groot, J. (2010). Explaining prosocial intentions: Testing causal relationships in the norm activation model. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 49(Pt 4), 725–743. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466609X477745

- Trommsdorff, G. (2010). Teaching and learning guide for: Culture and development of self-regulation. social and personality psychology compass, 4(4), 282–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00257.x

- Tsai, W. C., Chen, X., & Yang, C. (2020). Consumer food waste behavior among emerging adults: Evidence from China. Foods (Basel, Switzerland), 9(7), 961. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9070961

- Tu, M., Wang, X. D., & Guo, K. X. (2023). The double-edged sword effect of materialism on energy saving behaviors. Journal of Cleaner Production, 411, 137382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137382

- Uckan Yuksel, C., & Kaya, C. (2021). Traces of cultural and personal values on sustainable consumption: An analysis of a small local swap event in Izmir, Turkey. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 20(2), 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1843

- UNEP. (2021). Food waste index report 2021. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi. https://www.unep.org/resources/report/unep-food-waste-index-report-2021

- Vitell, S., Ramos-Hidalgo, E., & Rodríguez-Rad, C. (2018). A Spanish perspective on the impact on religiosity and spirituality on consumer ethics. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 42(6), 675–686. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12438

- Wang, L., Weng Wong, P. P., & Elangkovan, N. A. (2020). The influence of religiosity on consumer’s green purchase intention towards green hotel selection in China. Journal of China Tourism Research, 16(3), 319–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388160.2019.1637318

- Wang, S., Wang, J., Zhao, S., & Yang, S. (2019). Information publicity and resident’s waste separation behavior: An empirical study based on the norm activation model. Waste Management (New York, N.Y.), 87, 33–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2019.01.038

- Wang, X., & Zhang, C. (2020). Contingent effects of social norms on tourists’ pro-environmental behaviours: the role of Chinese traditionality. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(10), 1646–1664. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1746795

- Wang, Z., Guo, D., Wang, X., Zhang, B., & Wang, B. (2018). How does information publicity influence residents’ behaviour intentions around e-waste recycling? Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 133, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2018.01.014

- Worthington, E. L., Wade, N. G., Hight, T. L., Ripley, J. S., McCullough, M. E., Berry, J. W., Schmitt, M. M., Berry, J. T., Bursley, K. H., & O’Connor, L. (2003). The Religious Commitment Inventory–10: Development, refinement, and validation of a brief scale for research and counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50(1), 84–96. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.50.1.84

- Xu, L., Ling, M., Lu, Y., & Shen, M. (2017). External influences on forming residents’ waste separation behaviour: Evidence from households in Hangzhou, China. Habitat International, 63, 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2017.03.009

- Yoreh, T., & Scharper, S. B. (2020). Food Waste, Religion, and Spirituality: Jewish, Christian, and Muslim approaches. In Routledge Handbook of Food Waste (pp. 55–64). Routledge.

- Zakaria, N., Wan-Ismail, W. N. A., & Abdul-Talib, A. N. (2020). Seriously, conspicuous consumption? The impact of culture, materialism and religiosity on Malaysian Generation Y consumers’ purchasing of foreign brands. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 33(2), 526–560. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-07-2018-0283

- Zhang, B., Lai, K. H., Wang, B., & Wang, Z. (2019). From intention to action: How do personal attitudes, facilities accessibility, and government stimulus matter for household waste sorting? Journal of Environmental Management, 233, 447–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.12.059

- Zhang, L., Hu, Q., Zhang, S., & Zhang, W. (2020). Understanding Chinese residents’ waste classification from a perspective of intention–behavior gap. Sustainability, 12(10), 4135. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104135

- Zhang, S., Hu, D., Lin, T., Li, W., Zhao, R., Yang, H., Pei, Y., & Jiang, L. (2021). Determinants affecting residents’ waste classification intention and behavior: A study based on TPB and ABC methodology. Journal of Environmental Management, 290, 112591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112591Get

- Zhang, X., & Dong, F. (2020). Why do consumers make green purchase decisions? Insights from a systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186607