Abstract

This article seeks to reveal the most important elements of the physical and social servicescape in determining customer satisfaction and the intention to recommend the service during COVID-19-related restrictions. The necessity to wear masks, maintain social distance and other COVID-19 containment measures had a profound impact on the role of servicescape factors in the formation of customer satisfaction. A cross-sectional survey and a partial least squares (PLS) structural equation modelling (SEM) were employed as the main research tools. Visitors to nightclubs in Lithuania served as the empirical basis for the research. The study reveals that social servicescape factors were more important than physical servicescape factors in determining both customer satisfaction and the intention to recommend the service.

Reviewing Editor:

Introduction

Although the service environment and its impact on customer satisfaction and the intention to recommend a service have been studied for several years, research has focused on individual sectors and dimensions. Researchers acknowledge that very little is known about the impact of the social environment on the service experience and how it influences customer behaviour (Line & Hanks Citation2020) and that it is a relatively new concept (Morkunas & Rudienė, Citation2020). Additionally, physical and social environments are often researched separately (Line & Hanks, Citation2019), and there is a lack of scientific research integrating both physical and social servicescapes to obtain more multifaceted insights about the impact of the service environment on customer satisfaction and the intention to recommend (word of mouth) the service. The COVID-19 pandemic has made research on this topic even more puzzling. The requirements to wear masks both for service staff and consumers, increase the distance between customers in restaurants, bars and other similar establishments and lower visitor density in nightclubs significantly affected the social and physical servicescape and, possibly, its impact on customers’ satisfaction and intentions to recommend the service. This study was conducted during the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic when all the harshest measures for controlling the pandemic were enforced. Thus, it enables us to draw the first conclusions about how physical and social servicescape factors affect consumer satisfaction and the intention to recommend a service when masks on the faces of staff and customers conceal emotions, obscure facial features, do not allow to easily recognise persons or even depersonalise them; when increased distances between customers affect cosiness and atmosphere of the service provider and when reduced customer density decreases the number of new social contacts in public places. Until recently, the appearance, emotions and behaviour of employees and customers, as well as their identification with one another, were considered to be an important part of the social environment, which has a direct and strong impact on attitudes, satisfaction and loyalty (Morkunas & Rudienė, Citation2020). The COVID-19 containment measures created a precedent, which due to various reasons (most probably – medical, i.e. another pandemic, etc.) may repeat in the future (Fairlie, Citation2020; Gursoy & Chi, Citation2020). So it is important to know, how the importance of servicescape elements changes in times of the restrictions in order to assure the highest possible customer satisfaction even during the restrictions period. Therefore, the contribution of this article to knowledge development is twofold. First, it is one of very few studies to investigate the impact of both physical and social servicescapes on the customer satisfaction and intentions to recommend simultaneously. Second, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, it is the first study to investigate the effect of pandemic-related restrictions on servicescape components. The aim of this articler is to identify the influence of both physical and social servicescape factors on consumer satisfaction and intention to recommend a service during the periods of a severely restricted possibilities of service delivery.

The article is structured as follows. First, a literature review provides the theoretical background for the research. A methodological section then introduces the hypotheses and methods used. The results section lays out the most important results and briefly juxtaposes them with current theoretical streams. Finally, the conclusion generalises the results and identifies future research directions.

Theoretical background

The term ‘servicescape’ and its division into social servicescape (social environment of the service delivery) and physical (physical environment of service delivery) was proposed by Bitner (Citation1992). Line and Hanks (Citation2020) go further and divide social servicescape into two spheres – the employee environment and the customer environment – both of them consist out of the dimensions of similarity, appearance and behaviour. Further we provide a brief overview of each component of the social and physical servicescape.Staff behaviour: There are many different areas where employee behaviour can have an important impact on customer satisfaction. Babin and Boles (Citation1998) study shows that in some aspects gender can be important such as job satisfaction but both genders reacted similarly to many workplace constructs. Yao et al. (Citation2014) analysed stress factor impact on the negative employee behavior. Berry et al. (Citation2002) indicate that factors like body language or friendliness influence on the customers’ experience of a service and Wall and Berry (Citation2007) connect it with customers’ perception of the services quality. Staff behavior importance was recognised in different areas by different researchers, in the hotel sector (Baber & Kaurav, Citation2015) health services provision (Dcunha et al. (Citation2021)) showing that the behaviour of staff is one of the most important factors to choose one or other hotel or health centre. Staff conduct is not just about personnel of an organization, but also cultural elements that are not researched very well.

Staff appearance: The mere presence of employees in the environment can influence customer perceptions and behaviour as well as the experience. Studies (Magnini et al., Citation2013; Baker & Kim, Citation2018) have found that employees’ facial appearance and hair significantly influenced customers’ perceptions of service, satisfaction and loyalty. Customers’ perception of how similar an employee is to themselves is an important factor in evaluating the experience, and customers are more likely to interact with employees they perceive to be similar to themselves because they believe that similarity will help employees understand their needs and preferences (Kim & Cha, Citation2002; Morkunas & Rudienė, Citation2020). As a very important factor staff appearance was indicated in beauty salon services research (Kampani & Jhamb, Citation2020), restaurants and cafes (Jang et al., Citation2015, Lee & Kim, Citation2014). In travel agencies (Krzesiwo & Zaremba, Citation2020), the top-rated areas of customer service were staff appearance as well as their behaviour. Hopf (Citation2018) highlighted the importance of the service interaction between guest and employee in the hospitality industry by focusing on body modification and gender. Line and Hanks (Citation2019) confirmed that how employees were dressed and that employees looked nice are important for the customer in the hotel services. Customer behaviour: After pandemic period customers started looking for safety in terms of contactless, social distancing and barriers in seating (Roggeveen & Sethuraman, Citation2020), it means there are taking care about social distances and avoiding physical touches (Rosenbaum & Russell-Bennett, Citation2020). The appearance, emotions and behaviour of employees and customers, as well as their identification with them, were considered to be an important part of the social environment, which, in turn, has a direct and strong impact on attitudes, satisfaction and loyalty (Morkunas & Rudienė, Citation2020). Jang et al. (Citation2015) identify perceptions of service employees as positive element in restaurant services. It was noted, that customer behaviour is among the factors, which were affected most during the pandemic period (Eger et al., Citation2021) and requires additional research as current knowledge about trends of customer conduct at the service delivery places may be slightly outdated (Mehta et al., Citation2020). Customer appearance: Similarity and appearance with other customers influence customer perceptions and loyalty behaviour (Line & Hanks, Citation2017). In addition, similarity to other customers influences place attachment and firm identification (Line & Hanks, Citation2017). Line and Hanks (Citation2020) summarized previous research (Juwaheer & Lee-Ross, Citation2003; Pizam & Tasci, Citation2019; Line & Hanks, Citation2017) and pointed out that the characteristics and behaviours of restaurant employees can have a significant impact on customers’ evaluations, perceptions, satisfaction and behaviour, and that this is true even in the absence of a direct interaction with the individual employee. Facilities: Rashid et al. (Citation2015) indicate that facilities are important for the customers in entertainment area. Facilities importance in hotel services is also confirmed by Lee and Lee (Citation2015) stating that it is the most important factor for the customers’ judgement on the service quality. Lee and Kim (Citation2014) stresses the importance of facilities naming it focal for customers in choosing the service provider in an area of gyms and sporting complexes. Du and Shepotylo (Citation2022) noticed that during pandemic airports experienced employee layoffs and significantly decreased flow of passengers – this resulted in a closure of the majority of terminals but increased crowding in the ones still operating. Such increased density of passengers not only directly negatively affected customer experience but also led to the lowered assessment of the airport facilities. This finding once again supports the necessity of our research which was conducted during the pandemic period when restrictions in terms of customer density was imposed, so it is important to reveal, how this factor affected both social and physical servicescape elements. Layout & Interior: Layout can be identified in two aspects – perceived safety as tangible aspect (furnishing, surface materials, signages (Baker et al., Citation2020). The three main subdimensions of design factor in shaping customer experience are: spatial factors, colour and surface materials. However, when it comes to well-being, influence of biophilic elements starts to play the most important role in customer satisfaction (Rosenbaum & Massiah, Citation2011). Another aspect – space refers to equipment, technology, furniture and its arrangement as well as the convenience and accessibility of its layout. Functionality refers to the ability of all physical objects to facilitate the service exchange process (Nyrhinen et al., Citation2022). Kumar et al. (Citation2023) show that layout is an important factor influencing the physical and psychological safety of both customers and employees which is later being transformed into the increased mutual trust between staff and customers., which in turn, reflects in customer satisfaction. Such a proxy role of layout in shaping customer satisfaction is also confirmed by Rashid et al. (Citation2015) in entertainment services, Dharma et al. (Citation2019) in healthcare sector and Alfakhri et al. (Citation2018) in hospitality services. Cleanliness: The cleanliness factor appears to be the cheapest and easiest for the service provider to manage, but requires constant attention from the service provider (Barber & Scarcelli, Citation2010). Research by Hoffman et al. (Citation2003) showed that consumers most often cite cleanliness problems as a weakness of the service provider. Cleanliness influences customer affective responses, trust in the service provider and attributed prestige (Vilnai-Yavetz & Gilboa, Citation2010). Cleanliness is important across all categories of services, althoughit is more critical for personal services like hotels (Park et al., Citation2019), health sector or beauty sector (Kampani & Jhamb, Citation2020). Good lighting, the use of solid, sterile consumables and the presence of cleaning staff can impact actual and perceived cleanliness in the hospitality, retail sectors. In addition, biophilic elements, shiny surfaces and ambient scents can influence perceived cleanliness (Magnini & Zehrer, Citation2021), enhancing the physical and psychological safety of users. Lee and Lee (Citation2015) research confirm that cleanliness is a critical element in the service delivery environment, especially where functionality and health concerns matter, such as in hospitals, clinics and hotels. Customer identification: Line and Hanks (Citation2019) confirmed the role of customer identification as one of the most important factors in shaping customer judgement on the service provided. Jang et al. (Citation2015) confirmed importance of customers’ perception of other customers in restaurant services and identify this as positive factor in creating loyalty, but social crowding can influence it negatively. Workload: The success of any hospitality organization depends mainly on the employees’ performance (Al-Badarneh et al., Citation2019). Castro-Casal et al. (Citation2019) confirmed that services in hotels depends on their employees. Because of some specific aspects in some services like work 7/24, long working hours, unpredictable shifts, few breaks, excessive workload employees are under additional pressure. Grobelna (Citation2021) confirmed that workload exerts a significant impact on hotel employees’ leaving intention that reduces the quality of service performance. This, in turn is mirrored in the level of customer satsifaction and even loyalty (Abror et al., Citation2020). Muslih and Damanik (Citation2022) confirmed that the work environment and the workload have a significant effect on the employee performance and directly impact the provision of services and its outcome. Staff identification: Line and Hanks (Citation2019) confirmed importance of the staff identification factor by their research in hotel sector research. They identified that for customers it is important to know that ‘the employees are like me’ or ‘I am similar to the employees in the hotel’ or ‘I fit right in with the employees’. The desire of congruity between employees and customers is also considered crucial by Dong and Siu (Citation2013) in researching customer satisfaction and loyalty in entertainment industry.

Methodology

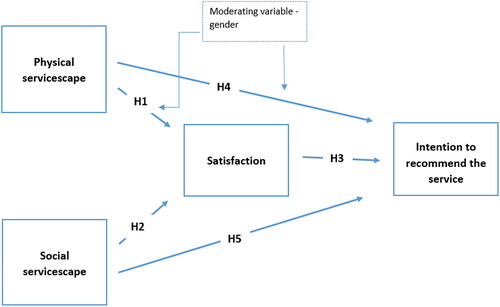

Hypothesis development and research model

Lin (Citation2010) found that the colours and music of a hotel bar have an impact on customer satisfaction, that is, new and unique colours and music that matches the bar’s target atmosphere increase customer arousal and lead to satisfaction. Ryu and Han (Citation2010) reported that when restaurant customers perceive the physical environment (such as interior design, colours and lighting) as reflecting quality, their satisfaction level increases. Lin and Mattila (Citation2010) observed that a restaurant’s physical environment determines customer satisfaction, while Hwang and Ok (Citation2013) found that a restaurant’s physical environment (environmental conditions, equipment layout, seating amenities) has a positive effect on patronage and the emotional response of restaurant patrons. Similarly, Rashid et al. (Citation2015) showed that environmental conditions (temperature and lighting), facility layout and signage affect the satisfaction of exhibition visitors. Hanks et al. (Citation2017) also demonstrated that the density of the spatial layout of equipment influences customers’ perception of an establishment. Meanwhile, Touchstone et al. (Citation2017) suggested that the mere lack of signage or informational links in a multilingual location causes customer disruption and a sense of discrimination, even if this is not the service provider’s intent. Line and Hanks (Citation2020) observed that the physical environment of a fast-food restaurant influences customer behaviour. For their part, Taheri et al. (Citation2020) found a significant effect of the physical environment on customer dissatisfaction (including customer misbehaviour) in a study of airport environments, and Vigolo et al. (Citation2020) reported that indoor signage has a significant effect on patient satisfaction in the hospital sector in Italy. Özkul et al. (Citation2020) observed that the colour of the lighting has an effect on customer satisfaction in the restaurant environment. Thus, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H1. The physical service delivery environment has a significant positive impact on customer satisfaction in the nightclub sector.

H2. The social service environment has a significant positive effect on customer satisfaction in the nightclub sector.

H3. Satisfaction with the nightclub environment has a significant positive effect on customers’ intentions to recommend a service.

H4. The physical environment of service delivery has a significant positive effect on the intention to recommend a service in the nightclub sector.

H5. The social environment of the service delivery has a significant positive effect on the intention to recommend a service in the nightclub sector.

The relationships between the hypotheses raised are shown in .

Survey sample and data analysis method

A nightclub’s services were selected as the empirical base for our research based on the following criteria: a) the service under investigation must have important physical and social servicescape dimensions in determining consumer satisfaction, b) the service provider must be among the most affected by the COVID-19 restrictions (Dey & Loewenstein, Citation2020), and c) the services researched should be relevant to a wider audience in various countries for results to be generalisable. Consequently, no traditional cultural services relevant only to small minorities or particular countries were considered for the research.

The survey was conducted from September to November of 2021. With the preselected 95% confidence level and a confidence interval of 5%, taking into account the population of Lithuania, the required sample size was 384. In total, 1265 responses were collected, of which 406 were found to be suitable for the study. For ethical reasons and the peculiarity of the questions included in the questionnaire, only persons aged 18 years and above were interviewed. Younger persons are not allowed to visit nightclubs according to Lithuanian legislation. We conducted a single cross-sectional study, collecting data only once from the population sample. We chose the non-probability sampling method of convenience sampling. The sampling method is left to the researcher’s judgment, and it is noted that this method has its limitations, and the findings should be generalised with caution. Similar studies using convenience sampling have been conducted in environmental research (Ryu & Han, Citation2010; Chua et al., Citation2020; Basarangil, Citation2018; Oviedo-García et al., Citation2019). Moreover, in real life, absolute random samples are very difficult to achieve, and a small deviation from this condition typically does not significantly affect the results (Mork¯unas, Citation2022). A structural equation modelling (SEM) partial least squares (PLS) analysis was employed as the main research tool. We chose a confirmatory component analysis (CCA) instead of the widely utilised exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) as CCA is credited with providing more robust results (Hair et al., Citation2020).

The rationale for selecting a PLS-SEM as the primary research method is that it is becoming a key research method in various disciplines, especially in fields such as marketing, information systems or innovation management (Rodríguez-Entrena et al., Citation2018) and because it allows to determine the strength of causal relationships from relatively small samples (Vinzi et al., Citation2010; Hair et al., Citation2019). Hair et al. (Citation2011) pointed out that data collected in social science research often do not follow a multivariate normal distribution and that some SEM methods used in path modelling can underestimate standard errors and overestimate goodness of fit. The use of PLS-SEM transforms non-normal data according to the central limit theorem and, therefore, enables the analysis of samples that do not follow a normal distribution and small samples. The primary data obtained were processed using SmartPLS version 3.3.3 software.

Results

The descriptive statistics of the researched variables are presented in , while model reliability indicators are provided in . Given that the data are not normally distributed, the Friedman criterion was used to examine the differences in the assessment of environmental factors.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the researched variables.

Table 2. Model reliability indicators.

The Friedman test yielded a Chi-square value of 768.779, p = 0.000 < 0.05, indicating that there is a statistically significant difference between the environmental factors. The highest-ranked factor (9.77) was the employee behaviour factor, and the lowest-ranked (3.96) was identification with employees. Pairwise comparisons of the factors using the Wilcoxon test were carried out to determine whether there is a statistically significant difference between them. The results of the test showed that consumers are most positive about the behaviour of employees; the appearance of employees and the appearance of customers and the behaviour of customers and equipment. The most unfavourable perceptions concerned identification with the staff and the occupancy of the club and identification with other customers and cleanliness.

The results of the Mann–Whitney U test revealed a significant difference in the evaluation of the equipment (U = 14859.500, p = 0.013), interior (U = 14990,500, p = 0.018), employee appearance (U = 14040.000, p = 0.001), employee behaviour (U = 13896.000, p = 0.000) between women and men. In all cases, women rated the above-mentioned environmental factors more favourably than men. This is interesting as it contradicts the findings of Morkunas and Rudienė (Citation2020). This may be related to the fact that women are more prone to engage in various social interactions than men. In addition, the opportunity for some form of social interaction in nightclubs after a long period of lockdown may have come as a reward (McKinlay et al., Citation2022; Kumar & Ayedee, Citation2022), thus positively affecting the mood. Moreover, the more positive the attitude of a person during the provision of the service, the better she/he evaluates it (Carneiro et al., Citation2019).

We checked whether there was a difference between men and women in terms of satisfaction and intention to recommend and found none (p > 0.05). However, the results of the Kruskal–Wallis test show that there is a statistically significant difference between consumers of different educational backgrounds for the following factors: cleanliness (H3 = 10.116, p = 0.018), customer appearance (H3 = 10.575, p = 0.014), social servicescape (S.S.) employee identification (H3 = 7.909, p = 0.048) and employee appearance (H3 = 14.959, p = 0.002).

We found that the asymmetry and skewness do not significantly deviate from the normal distribution (Mardia’s test p = 0.000; asymmetry = 4.131; skewness = 38.295). The appropriateness of the PLS-SEM method for further research was thus justified.

As seen in the table, the Cronbach’s alphas of the adjusted variables and the internal consistency reliability exceed 0.7 and are considered acceptable (Hair et al., Citation2019). Once the constructs were validated, we examined their average variance extracted (AVE). The estimated AVE ranges from 0.600 to 0.838 and is above the recommended value of 0.50. The discriminant validity of the structural model was assessed using Fornell–Larcker and heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) criteria ( and ).

Table 3. Fornell–Larcker correlation values.

Table 4. Heterotrait–monotrait correlations of the researched constructs.

Henseler et al. (Citation2015) indicated that a suitable value for the HTMT correlation index is up to 0.85, conservatively, but a value of 0.9 is also possible, as well as a value of 1 in the case of larger samples. Therefore, we assume that this condition is fulfilled as the maximum value for the HTMT index in the data does not exceed 0.784 ().

An additional step in the confirmatory composite analysis is to check the nomological validity. One of the approaches cited by Hair et al. (Citation2020) is to use the results of previous studies to determine the theoretical relationship between the constructs. The service environment model is described quite well in the literature, and the theoretical model was developed based on similar research on physical and social servicescapes. Nomological validity in this case would imply that the physical and social servicescape has a positive effect on user satisfaction, which, in turn, has a positive effect on the intention to recommend services. The results of the relationships obtained (positive correlation) suggest that the nomological validity of the model is appropriate as it is in line with the relationships previously identified by the researchers. There is also a positive correlation between frequency of attendance, time spent, money spent at the club and satisfaction, which indicates nomological validity. Following the confirmatory composite analysis, the structural model was further assessed.

According to Hair et al. (Citation2019), the VIF score should be less than 5, but a score between 3 and 5 may present challenges for collinearity. The VIF test results of the model ( in the Annex) clearly show collinearity trends in the satisfaction construct. This could be explained by similar issues in the satisfaction construct.

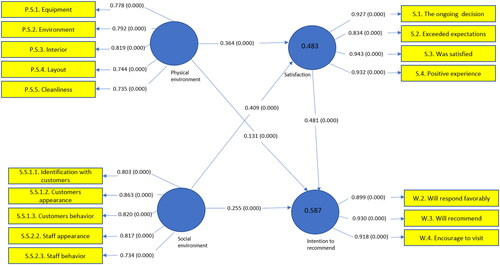

To assess the validity of the model, its statistical significance is analysed using a bootstrapping process. The bootstrapping process generates new samples from the existing sample and evaluates the statistical significance of the relationship. The self-selection process uses 5000 samples, following Hair et al. (Citation2019). The coefficient of determination (R2), standardised path coefficients (β), Student’s criterion for the significance of the association (t-statistic) and p values (the association is statistically significant at p < 0.05) were calculated. The results of the self-selection reveal a statistically significant relationship between the physical and social environment and consumer satisfaction, between the physical and social environment and the consumer’s intention to recommend and between the consumer’s satisfaction and intention to recommend (t > 1.96; p < 0.05). The path coefficients show a very weak relationship between the physical servicescape and the intention to recommend and a weak relationship between the other variables. The next step in the model evaluation is to estimate the coefficient of determination R2. The R2 value is 0.483 for satisfaction and 0.587 for the intention to recommend. These figures show that the model explains 48.30% of the variation in satisfaction and 58.7% of the variation in intention to recommend.

All our hypotheses were confirmed (). The highest path coefficient (0.481) is between satisfaction and the intention to recommend, which could be anticipated based on a large body of literature examining this relationship (Loureiro et al., Citation2017; Eid et al., Citation2019; Al-Ansi et al., Citation2019). The more novel and significant findings are the high importance of the social servicescape to customer satisfaction (path coefficient = 0.409) and the intention to recommend (0.255). Because most of the attributes of the social servicescape (emotions and facial expressions of the staff and consumer, social density, social congruence, etc.) were significantly downgraded during the COVID-19 pandemic due to requirements to use masks and increase distances between consumers, the physical servicescape could be anticipated to prevail in determining customer satisfaction and the intention to recommend in this context. These findings call for additional research in social servicescape to determine which social servicescape attributes truly influence customer satisfaction and the intention to recommend. We revealed that in nightclubs, even when its effects were significantly reduced, the social servicescape remained more important than the physical servicescape in determining customer satisfaction (0.409 vs. 0.364) and the intention to recommend (0.255 vs. 0.134). The percentile bootstrapping procedure (5000 iterations) was conducted to test the statistical significance of the results. No significant deviations from the originally derived path coefficients were detected (please, see ).

Table 5. Path coefficients and significance intervals of the structural model.

The moderation analysis confirmed assumptions about the existence of gender-related differences in the impact the physical servicescape elements exerts on the customer satisfaction and the intention to recommend the service ().

Table 6. The results of moderation analysis.

Table 7. Results of the effect size testing.

It was revealed, that social servicescape elements have a bigger influence in shaping men’s satisfaction by service compared to women’s. These findings complement Morkunas and Rudienė (Citation2020) insights, who state, that women tend to be more critical toward social servicescape elements compared to men. Combining the results of our research and Morkunas and Rudienė (Citation2020) study, we can conclude, that social servicescape elements are more important to women in deciding customer satisfaction. Men, in contrary, ten to pay more attention to physical servicescape elements when judging on the service provided. Our research also shows that women tend to engage into word of mouth regarding services received more compared to men. This allows to conclude, that the owners of the nightclubs or other service providers should approach women first if they expect to receive recommendations of their services.

The next step in the evaluation of our model is the assessment of predictability using the effect size (f2) (). The calculated f2 value shows that the variables meet the minimum criteria for significance. The smallest effect is found between the physical and social environment and the intention to recommend, and we observe a medium effect between the other variables.

Another indicator for model evaluation is the Stone Geisser (Q2) coefficient. The resulting values of 0.395 for satisfaction and 0.484 for the intention to recommend indicate that the model has medium predicted relevance.

Conclusion

This study adds to the marketing knowledge about a business segment (nightclubs) whose physical and social servicescape has not been widely studied. Cardona and Sanchez-Fernandez (2017) point out that studies looking at nightclub management are very rare and that the nightclub environment was last studied in 2008.

Our results show that both the physical servicescape and the social servicescape have a statistically significant impact on customer satisfaction and the intention to recommend a service. These findings are a step toward a more detailed understanding of how the elements of the service environment work together to influence customers’ perceptions and evaluations of the experience. They also confirm the importance of capturing a holistic view of the service environment, that is, considering the physical and social servicescape together as both have an impact on the customer.

Although the servicescape items were highly rated by consumers, the Friedman test showed that the ratings are not homogeneous. According to the Wilcoxon tests, the highest scoring elements (appearance and behaviour of the staff and customers) pertained to the social servicescape dimension. These results confirm once again that not only the physical environment but also the social environment is important to customers in the service area. They also indicate that social factors are quite important in the nightclub sector. This is a very important finding as our research was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic-related restrictions, which severely restrained the social servicescape (via the use of face masks, significant reductions in customer density, etc.) and moderated its possible impact on customer satisfaction and intentions to recommend. The social servicescape still proved to be very important in determining customer satisfaction, allowing us to derive two additional implications. From a theoretical point of view, we confirm that the social servicescape has a greater influence than the physical servicescape on customer satisfaction and the intention to recommend the service. Another important insight is the fact that when all customers wear masks, the customer appearance and behaviour aspects of the social servicescape were rated very high. This means that the ability to ‘disappear’ and be less recognisable is desirable to nightclub customers. Another implication may be related to the number of visitors. It is typical for nightclubs to be overcrowded with visitors (Pinke-Sziva et al., Citation2019). The high evaluation of the social density facet of the social servicescape during the pandemic (when the number of visitors was significantly reduced) may reflect the desire of visitors to find a slightly lower density of visitors in the nightclubs during normal times as well. However, this insight must still be confirmed by additional research and can be considered a prospective research avenue, which, if supported, could have both theoretical and practical implications.

We also found that neither occupation nor marital status had a statistically significant effect on the assessment of servicescape elements and satisfaction. We confirm that both the physical and the social servicescape have an impact on customer satisfaction and the intention to recommend the service. It should be noted that the servicescape factors explain almost half of the variation in customer satisfaction. In turn, servicescape and satisfaction account for almost 60% of the variation in intention to recommend.

We found that men tend to allocate more importance toward physical servicescape compared to women when judging on the services provided. This raises another practical implication: services, which are more oriented toward male audience should focus more on the improvements of the physical servicescape. But if the preferred target group is women (e.g. beauty salons, etc.), the service provider should concentrate on the social servicescape elements first.

The higher inclination of women toward spreading word of mouth, compared to men has a twofold practical implication. First, in order to get positive reviews or recommendations service providers should approach women first, as there is a higher chance to receive a positive feedback or recommendation. On the other hand, service providers should not get very disappointed if they do not receive positive recommendation from men for the service delivered. As our research showed men are simply less inclined to recommend the service received.

When consumers are looking for specific and unique experiences (which is what the club environment provides), more frequent visits to a club reduce satisfaction with the elements of its servicescape, although this does not significantly reduce satisfaction with the holistic environment. It can be assumed that a decrease in hedonic stimuli occurs when the environment no longer provides a sufficient level of stimulation due to experience.

One of the possible limitations of our study may be connected to the empirical base of the research. We derived our results from the nightclub sector, and the combination of the most important social and physical servicescape factors determining customer satisfaction and intention to recommend the service may be different for other services. Another limitation may concern the age factor. The typical nightclub visitors are young adults (Beselia et al., Citation2019), and older persons may assess physical and social servicescape factors differently. The investigation of this issue could also be a research avenue. Another research direction could aim at revealing the influence of both physical and social servicescape elements on consumer satisfaction for services with a significant tangible component.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mangirdas Morkunas

Dr. Mangirdas Morkūnas is with the Faculty of Economics and Business Administration at Vilnius University. His main research areas cover agri-business, rural development, conduct of business in an unfavourable conditions, servicescape and the sustainable consumption.

Elzė Rudienė

Dr. Elzė Rudienė is an associate professor at Vilnius University Business School. She leads the Digital Marketing master studies program. Her main research interests include services marketing, marketing communication and digital advertising.

Norbertas Valiauga

Mr. Norbertas Valiauga is interested in service business, insurance and advertising.

References

- Abror, A., Patrisia, D., Engriani, Y., Evanita, S., Yasri, Y., & Dastgir, S. (2020). Service quality, religiosity, customer satisfaction, customer engagement and Islamic bank’s customer loyalty. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 11(6), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-03-2019-0044

- Al-Ansi, A., Olya, H. G., & Han, H. (2019). Effect of general risk on trust, satisfaction, and recommendation intention for halal food. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 83, 210–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.10.017

- Al-Badarneh, M. B., Shatnawi, H. S., Alananzeh, O. A., & Al-Mkhadmeh, A. A. (2019). Job performance management: The burnout inventory model and intention to quit their job among hospitality employees. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 5(2), 1355–1375.

- Alfakhri, D., Harness, D., Nicholson, J., & Harness, T. (2018). The role of aesthetics and design in hotelscape: A phenomenological investigation of cosmopolitan consumers. Journal of Business Research, 85, 523–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.10.031

- Baber, R., & Kaurav, R. P. S. (2015). Criteria for hotel selection: A study of travellers. Pranjana: The Journal of Management Awareness, 18(2), 52–59. https://doi.org/10.5958/0974-0945.2015.00012.6

- Babin, B. J., & Boles, J. S. (1998). Employee behavior in a service environment: A model and test of potential differences between men and women. Journal of Marketing, 62(2), 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299806200206

- Baker, J., Bentley, K., & Lamb, C.Jr (2020). Service environment research opportunities. Journal of Services Marketing, 34(3), 335–346. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-02-2019-0077

- Baker, M. A., & Kim, K. (2018). Other customer service failures: Emotions, impacts, and attributions. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 42(7), 1067–1085. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348016671394

- Barber, N., & Scarcelli, J. M. (2010). Enhancing the assessment of tangible service quality through the creation of a cleanliness measurement scale. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 20(1), 70–88. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604521011011630

- Basarangil, I. (2018). The relationships between the factors affecting perceived service quality, satisfaction and behavioral intentions among theme park visitors. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 18, 415–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358416664566

- Berry, L. L., Carbone, L. P., & Haeckel, S. H. (2002). Managing the total customer experience. MIT Sloan Management Review.

- Beselia, A., Kirtadze, I., & Otiashvili, D. (2019). Nightlife and drug use in Tbilisi, Georgia: Results of an exploratory qualitative study. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 51(3), 247–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2019.1574997

- Bitner, M. J. (1992). Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of Marketing, 56(2), 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299205600205

- Cardona, J. R., & Sánchez-Fernández, M. D. (2017). Nightlife sector from a gender point of view: The case of Ibiza. European Journal of Tourism, Hospitality and Recreation, 8(1), 51–64. https://doi.org/10.1515/ejthr-2017-0005

- Carneiro, M. J., Eusébio, C., Caldeira, A., & Santos, A. C. (2019). The influence of eventscape on emotions, satisfaction and loyalty: The case of re-enactment events. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 82, 112–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.03.025

- Castro-Casal, C., Vila-Vázquez, G., & Pardo-Gayoso, Á. (2019). Sustaining affective commitment and extra-role service among hospitality employees: Interactive effect of empowerment and service training. Sustainability, 11(15), 4092. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154092

- Chang, K. C. (2016). Effect of servicescape on customer behavioral intentions: Moderating roles of service climate and employee engagement. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 53, 116–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.12.003

- Chua, B. L., Karim, S., Lee, S., & Han, H. (2020). Customer restaurant choice: An empirical analysis of restaurant types and eating-out occasions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6276. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176276

- Dcunha, S., Suresh, S., & Kumar, V. (2021). Service quality in healthcare: Exploring servicescape and patients’ perceptions. International Journal of Healthcare Management, 14(1), 35–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/20479700.2019.1605689

- Dey, M., & Loewenstein, M. A. (2020). How many workers are employed in sectors directly affected by COVID-19 shutdowns, where do they work, and how much do they earn? Monthly Labor Review, April, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.21916/mlr.2020.6

- Dharma, D., Adawiyahi, R. W., & Sutrisna, E. (2019) The effect of servicescape dimension on patient satisfaction in private hospital in purwokerto [Paper presentation]. Central Java. International Conference on Rural Development and Enterpreneurship 2019: Enhancing Small Busniness and Rural Development Toward Industrial Revolution 4.0, Purwokerto, Indonesia (Vol. 5).

- Dong, P., & Siu, N. Y. M. (2013). Servicescape elements, customer predispositions and service experience: The case of theme park visitors. Tourism Management, 36, 541–551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.09.004

- Du, J., & Shepotylo, O. (2022). UK trade in the time of COVID‐19: A review. The World Economy, 45(5), 1409–1446. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.13220

- Eger, L., Komárková, L., Egerová, D., & Mičík, M. (2021). The effect of COVID-19 on consumer shopping behaviour: Generational cohort perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 61, 102542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102542

- Eid, R., El-Kassrawy, Y. A., & Agag, G. (2019). Integrating destination attributes, political (in) stability, destination image, tourist satisfaction, and intention to recommend: A study of UAE. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 43(6), 839–866. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348019837750

- Fairlie, R. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on small business owners: Evidence from the first three months after widespread social-distancing restrictions. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 29(4), 727–740. https://doi.org/10.1111/jems.12400

- Grobelna, A. (2021). Emotional exhaustion and its consequences for hotel service quality: The critical role of workload and supervisor support. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 30(4), 395–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2021.1841704

- Gursoy, D., & Chi, C. G. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on hospitality industry: Review of the current situations and a research agenda. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 29(5), 527–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2020.1788231

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

- Hair, J. F., Howard, M. C., & Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Han, J., Kang, H. J., & Kwon, G. H. (2018). A systematic underpinning and framing of the servicescape: Reflections on future challenges in healthcare services. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(3), 509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15030509

- Hanks, L., Line, N., & Kim, W. G. W. (2017). The impact of the social servicescape, density, and restaurant type on perceptions of interpersonal service quality. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 61, 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.10.009

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hepola, J., Leppäniemi, M., & Karjaluoto, H. (2020). Is it all about consumer engagement? Explaining continuance intention for utilitarian and hedonic service consumption. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 57, 102232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102232

- Hoffman, K. D., Kelley, S. W., & Chung, B. C. (2003). A CIT investigation ofservicescape failures and associated recovery strategies. Journal of Services Marketing, 17(4), 322–340. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040310482757

- Hopf, V. (2018). Does the body modified appearance of front-line employees matter to hotel guests? Research in Hospitality Management, 8(1), 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/22243534.2018.1501959

- Huang, W. H. (2008). The impact of other-customer failure on service satisfaction. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 19(4), 521–536. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564230810891941

- Hwang, J., & Ok, C. (2013). The antecedents and consequence of consumer attitudes toward restaurant brands: A comparative study between casual and fine dining restaurants. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 32(1), 121–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.05.002

- Jain, S. P., & Weiten, T. J. (2020). Consumer psychology of implicit theories: A review and agenda. Consumer Psychology Review, 3(1), 60–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/arcp.1056

- Jang, Y., Ro, H., & Kim, T. H. (2015). Social servicescape: The impact of social factors on restaurant image and behavioral intentions. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 16(3), 290–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2015.1054758

- Juwaheer, D., & Lee-Ross, D. (2003). A study of hotel guest perceptions in Mauritius. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 15, 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110310462959

- Kampani, N., & Jhamb, D. (2020). Uncovering the dimensions of servicescape using mixed method approach – A study of beauty salons. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 28(4), 1247–1272. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-09-2020-0492

- Karamustafa, K., & Ülker, P. (2020). Impact of tangible and intangible restaurant attributes on overall experience: A consumer oriented approach. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 29(4), 404–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2019.1653806

- Kattara, H., Weheba, D., & El-Said, O. (2008). The impact of employee behaviour on customers’ service quality perceptions and overall satisfaction. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 8(4), 309–323. https://doi.org/10.1057/thr.2008.35

- Kim, W. G., & Cha, Y. (2002). Antecedents and consequences of relationship quality in hotel industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 21(4), 321–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-4319(02)00011-7

- Konuk, F. A. (2019). The influence of perceived food quality, price fairness, perceived value and satisfaction on customers’ revisit and word-of-mouth intentions towards organic food restaurants. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 50, 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.05.005

- Krzesiwo, K., & Zaremba, A. (2020). Jakość obsługi klienta W biurach podróży - przykład krakowa. Prace Geograficzne, 160(160), 9–27. https://doi.org/10.4467/20833113PG.20.001.12259

- Kumar, A., & Ayedee, N. (2022). Life under COVID-19 lockdown: An experience of old age people in India. Working with Older People, 26(4), 368–373. https://doi.org/10.1108/WWOP-06-2020-0027

- Kumar, S. D., Nair, U., & Purani, K. (2023). Servicescape design: Balancing physical and psychological safety. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 41(4), 473–488. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-06-2022-0259

- Kwong D, L. (2017). The role of servicescape in hotel buffet restaurant. Journal of Hotel & Business Management, 06(01), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.4172/2169-0286.1000152

- Lee, S. Y., & Kim, J. H. (2014). Effects of servicescape on service quality, satisfaction and behavioral outcomes in public service facilities. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 13(1), 125–131. https://doi.org/10.3130/jaabe.13.125

- Lee, S. H., & Lee, H. (2015). The design of servicescape based on benefit sought in hotel facilities: A survey study of hotel consumers in Seoul. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 14(3), 633–640. https://doi.org/10.3130/jaabe.14.633

- Lin, I. Y. (2010). The interactive effect of Gestalt situations and arousal seeking tendency on customers’ emotional responses: matching color and music to specific servicescapes. Journal of Services Marketing, 24(4), 294–304. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876041011053006

- Lin, I. Y., & Mattila, A. S. (2010). Restaurant servicescape, service encounter, and perceived congruency on customers’ emotions and satisfaction. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 19(8), 819–841. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2010.514547

- Line, N. D., & Hanks, L. (2019). The social servicescape: Understanding the effects in the full-service hotel industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(2), 753–770. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-11-2017-0722

- Line, N. D., & Hanks, L. (2020). A holistic model of the servicescape in fast casual dining. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(1), 288–306. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04-2019-0360

- Line, N. D., & Hanks, L. (2017). The other customer: The impact of self-image in restaurant patronage. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 20(3), 268–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/15378020.2016.1206773

- Loureiro, S. M. C., Gorgus, T., & Kaufmann, H. R. (2017). Antecedents and outcomes of online brand engagement: The role of brand love on enhancing electronic-word-of-mouth. Online Information Review, 41(7), 985–1005. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-08-2016-0236

- Magnini, V. P., Baker, M., & Karande, K. (2013). The frontline provider’s appearance: A driver of guest perceptions. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 54(4), 396–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965513490822

- Magnini, V. P., & Zehrer, A. (2021). Subconscious influences on perceived cleanliness in hospitality settings. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102761

- Martin, C. L., & Pranter, C. A. (1989). Compatibility management: Customer-to-customer relationships in service environments. Journal of Services Marketing, 3(3), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000002488

- McKinlay, A. R., May, T., Dawes, J., Fancourt, D., & Burton, A. (2022). “You’re just there, alone in your room with your thoughts” A qualitative study about the impact of lockdown among young people during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ open, 12(2), e053676.

- Mehta, S., Saxena, T., & Purohit, N. (2020). The new consumer behaviour paradigm amid COVID-19: Permanent or transient? Journal of Health Management, 22(2), 291–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972063420940834

- Mork¯unas, M. (2022). Revealing differences in brand loyalty and brand engagement of single or no parented young adults. IIM Kozhikode Society & Management Review, 12(1), 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/22779752221108797

- Morkunas, M., & Rudienė, E. (2020). The impact of social servicescape factors on customers’ satisfaction and repurchase intentions in mid-range restaurants in baltic states. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 6(3), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6030077

- Muslih, M., & Damanik, F. A. (2022). Effect of work environment and workload on employee performance. International Journal of Economics, Social Science, Entrepreneurship and Technology (IJESET), 1(1), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.55983/ijeset.v1i1.24

- Nyrhinen, J., Uusitalo, O., Frank, L., & Wilska, T. A. (2022). How is social capital formed across the digital-physical servicescape? Digital Business, 2(2), 100047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.digbus.2022.100047

- Olson, E., & Park, H. (2019). The impact of age on gay consumers’ reaction to the physical and social servicescape in gay bars. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(9), 3683–3701. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-12-2018-0999

- Oviedo-García, M. Á., Vega-Vázquez, M., Castellanos-Verdugo, M., & Orgaz-Agüera, F. (2019). Tourism in protected areas and the impact of servicescape on tourist satisfaction, key in sustainability. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 12, 74–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2019.02.005

- Özkul, E., Bilgili, B., & Koç, E. (2020). The Influence of the color of light on the customers’ perception of service quality and satisfaction in the restaurant. Color Research & Application, 45(6), 1217–1240. https://doi.org/10.1002/col.22560

- Park, J. Y., Back, M. R., Bufquin, D., & Shapoval, V. (2019). Servicescape, positive affect, satisfaction and behavioral intentions: The moderating role of familiarity. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 78, 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.11.003

- Pinke-Sziva, I., Smith, M., Olt, G., & Berezvai, Z. (2019). Overtourism and the night-time economy: A case study of Budapest. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 5(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-04-2018-0028

- Pizam, A., & Tasci, A. D. A. (2019). Experienscape: Expanding the concept of servicescape with a multi-stakeholder and multi-disciplinary approach. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 76, 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.06.010

- Rashid, N. M., Ma’amor, H., Ariffin, N., & Achim, N. (2015). Servicescape: Understanding how physical dimensions influence exhibitors satisfaction in convention centre. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 211, 776–782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.167

- Rodríguez-Entrena, M., Schuberth, F., & Gelhard, C. (2018). Assessing statistical differences between parameters estimates in Partial Least Squares path modeling. Quality & Quantity, 52(1), 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-016-0400-8

- Roggeveen, A. L., & Sethuraman, R. (2020). How the COVID-19 pandemic may change the world of retailing. Journal of Retailing, 96(2), 169–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2020.04.002

- Rosenbaum, M. S., & Massiah, C. (2011). An expanded servicescape perspective. Journal of Service Management, 22(4), 471–490. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564231111155088

- Rosenbaum, M. S., & Russell-Bennett, R. (2020). Service research in the new (post-COVID) marketplace. Journal of Services Marketing, 34(5), I–V. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-06-2020-0220

- Ryu, K., & Han, H. (2010). Influence of the quality of food, service, and physical environment on customer satisfaction and behavioral intention in quick-casual restaurants: Moderating role of perceived price. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 34(3), 310–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348009350624

- Siguaw, J. A., Mai, E., & Sheng, X. (2020). Word-of-mouth, servicescapes and the impact on brand effects. SN Business & Economics, 1(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43546-020-00016-7

- Taheri, B., Olya, H., Ali, F., & Gannon, M. J. (2020). Understanding the influence of airport servicescape on traveler dissatisfaction and misbehavior. Journal of Travel Research, 59(6), 1008–1028. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519877257

- Touchstone, E. E., Koslow, S., Shamdasani, P. N., & D’Alessandro, S. (2017). The linguistic servicescape: Speaking their language may not be enough. Journal of Business Research, 72, 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.10.008

- Vigolo, V., Bonfanti, A., Sallaku, R., & Douglas, J. (2020). The effect of signage and emotions on satisfaction with the servicescape: An empirical investigation in a healthcare service setting. Psychology & Marketing, 37(3), 408–417. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21307

- Vilnai-Yavetz, I., & Gilboa, S. (2010). The effect of servicescape cleanliness on customer reactions. Services Marketing Quarterly, 31(2), 213–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332961003604386

- Vinzi, E., Vincenzo, T., Amato, L., & Silvano, E. (2010). PLS path modeling: From foundations to recent developments and open issues for model assessment and improvement. Handbook of partial least squares: Concepts, methods and applications, 47–82.

- Wall, E. A., & Berry, L. L. (2007). The combined effects of the physical environment and employee behavior on customer perception of restaurant service quality. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 48(1), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010880406297246

- Yao, Y. H., Fan, Y. Y., Guo, Y. X., & Li, Y. (2014). Leadership, work stress and employee behavior. Chinese Management Studies, 8(1), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1108/CMS-04-2014-0089

Annex

Table A1. VIF values of the researched constructs.

Table A2. Correlations among the researched variables.