Abstract

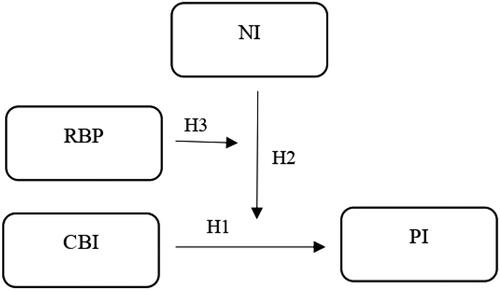

Religion and nationalism are two of the prominent individual identities which can signify the consumers’ emotional attachment to the brand. However, brand communication rarely incorporates those two approaches simultaneously due to their seemingly contradictory nature, which may burden the overall brand messages. This study investigates the three-way interaction between consumers’ brand identification (CBI), national identity (NI), religious brand positioning (RBP), and their effects on purchase intention (PI). According to the context of this study, an experimental survey involving two groups of small business consumers was employed in the data collection. Hierarchical multiple regression is used to investigate the three-way interaction between CBI, NI, RBP, and PI. The result revealed a significant three-way interaction effect, where the strongest influence was found in high NI and brands with religious positioning scenarios. This study concluded that nationalism and religious identities do not reject each other. Moreover, those two identities simultaneously strengthen consumers’ emotional attachment to the brands. Hence, small business owners can develop communication strategies to affirm consumers’ nationalism and religious identities.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

National and religious identities are two primary psychological identities that have recently drawn much attention from scholars. Individual national identity signifies and gives rise to new local identities, especially in the wake of people’s anxiety and insecurity in response to the destabilizing effects of globalization (Kinvall, Citation2004). Murshed (Citation2019) highlighted the critical role of nationalism as an approach to capture the consumers’ national identity, reinforce their socio-cultural values, and provide a sense of ownership to local products other than global brands. The current revival of nationalism goes beyond the realm of politics and has become intertwined with the practices of promotion and consumption (Castelló & Mihelj, Citation2017). Marketers also incorporate religious approaches to attract their target consumers, as religious reason is the primary driver of consumption. Marketing communication attempts to capture religious segments by emphasizing religious cues for consumption, such as kosher (Jews) or halal (Islam). Religious marketing approaches are common in the area with prominent religious influence. Even multinational brands use religious festivals to customize their campaign to bring the brand identity closer to the religious group of consumers.

Despite the critical role of religious and national identities in engaging with the target consumers, scarce studies have investigated the effect of the simultaneous approach of religion and nationalism toward building brand identity. This could be due to the seemingly contradictory, opposed to each other, which inflicts a considerable debate on the relationship between religion and nationalism (Mentzel, Citation2020). This contradiction could weaken the overall brand messages. On a broader aspect, it is no surprise that some arguments stand on a seemingly unethical view of the relationship between these two, such as that nationalism is intrinsically secular. Similarly, previous studies dominantly described nationalism as a modern phenomenon that supplanted religious self-identification and eventually replaced it with more secular ones (Smith, Citation1999). Therefore, it is understandable why marketers refrain from incorporating those two approaches simultaneously (e.g. domestically halal brands) in their advertisings, as it potentially weakens the overall brand positioning.

However, recent studies on patriotism and religion noticed that these two kinds of self-identification could be coexistent or mutually supportive (Barry, Citation2020; Ichwan et al., Citation2020; Mentzel, Citation2020). This is mainly due to the inability and the ineffectiveness of secular nationalism to express the public values and moral community. People are more demanding of social identification, which eventually spurred the idea of so-called ‘religious nationalism’ (Juergensmeyer, Citation2010). Busse (Citation2019) argued that religious nationalism, or the fusion of religious and national identities, is an increasingly salient aspect of nationalism. He highlighted the potential of these two identities to reinforce each other in achieving the nation’s goals. In fact, the relationship between nationalism and religion is a kind of continuum which is ‘secular nationalism’ at one end and a fully ‘religious nationalism’ at the other end (Soper & Fetzer, Citation2018). As such, individuals can have national and religious identities to represent their subjectivity. Given the momentum of religious nationalism increasing awareness, especially in Indonesia, this present study provides timely insights for marketers to reach consumers with those two identity communication approaches.

Meanwhile, scholars have advocated the role of consumer brand identity (CBI) in pursuing consumers’ purchase intention (PI) through its ability to fortify the congruity between consumers’ personalities, self-concept, and the brands’ (Chen et al., Citation2021; Wassler et al., Citation2019). CBI’s impact on PI can be boosted when consumers perceive their values to be congruent with those of the brands (Coelho et al., Citation2018). Shokri and Alavi (Citation2019) asserted that it is imperative to explore more factors that shape value congruity between brands and consumers as it will strengthen the role of CBI in consumer outcomes (Shokri & Alavi, Citation2019). Therefore, responding to those calls, this present study attempts to investigate the simultaneous impact of the nationalism and religious approach reflected by a three-way interaction between national identity (NI) and religious brand positioning (RBP) on the relationship between CBI and PI. The context of this study is Indonesian entrepreneurs and their businesses. Indonesian entrepreneurs struggle to recover from the business downturn due to the covid-19 pandemic. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, small businesses accounted for more than 90% of business types in Indonesia and contributed to more than 90% of employment in 2021 (Central Bureau of Statistics, Citation2022). Hence, the accelerated recovery of this segment plays a critical role in the whole national economic recovery.

Theoretically, this paper extends the research stream on the consumer-brand relationship in two ways. First, this paper contributes to the ongoing debate regarding the possibility of both nationalism and religious identity being owned by an individual. Second, this study implements nationalism and religious positioning in branding activities and provides evidence of how that two approaches interact with consumer-brand identification. Practically this paper provides empirical evidence which could be a salient communication strategy for marketers and business owners by incorporating nationalism and religious factors. Also, in line with the context of this present study, the findings contribute to policy insight for Government in formulating a strategy to accelerate the small business recovery. The later parts of this paper were organized as follows: the next section described theories and the hypotheses development. Subsequently, the research methodology was described, covering the measurement, data collection, and analysis steps. The following section is the results and discussions. The last sections were conclusions, theoretical and practical implications, limitations, and directions for further studies.

Theories and hypotheses development

Consumer brand identification

C. K. Kim et al. (Citation2001) defined CBI as the degree to which the brand expresses and enhances the consumer’s identity. CBI reflects the consumers’ perceived oneness with a brand. It acts as a means for identity-fulfilling (Sauer et al., Citation2012). CBI has developed into a new force in marketing strategies due to the rising intensity of consumer demands. Companies find it challenging to fulfill or outperform consumers’ expectations only using the traditional features-benefits strategy. Likewise, consumer satisfaction no longer suffices to create significant differentiation from competitors (Popp & Woratschek, Citation2017). Ahearne et al. (Citation2005) asserted that the orientation shift toward identification is an expansion of relationship marketing. This identification is a binding force to create a more robust consumer relationship. With this notion, CBI is the last phase in the consumer-company relationship. CBI starts on a transactional basis, focuses on an enduring relationship, and ends with a perceived oneness of consumers with the brands (Popp & Woratschek, Citation2017; Coelho et al., Citation2018). Therefore, unlike traditional brand evaluative measures (i.e. brand attitude), CBI emphasizes both sides more, as it involves the perceived brand identity and the consumer’s self-identity (Sauer et al., Citation2012).

CBI plays a crucial strategy beyond functional features and aims to enhance the product’s value. It involves attaching the consumers to the brand by creating an association between the brand name and qualities such as luxury, higher cost-benefit ratio, or environmental concern, among others (Morgan & Rego, Citation2009). Sirgy et al. (Citation1991) coined self-image congruence as the cognitive matching between brand expressive value and consumer-self-concept. This congruity plays a critical role in consumers’ decisions and could explain why they choose specific brands and reject others (Japutra et al., Citation2018). The enduring congruity eventually makes them loyal consumers (Kaap-Deeder et al., Citation2016). Further, Vikas and Nayak (Citation2014) asserted that the focal point of brand identity communication highlights the compatibility between the brands and consumers’ psychological factors. Brand identity should emphasize the consumers’ self-concept to create CBI. As such, the CBI develops a positive attitude, boosts the consumers’ psychological ownership, and enhances their PI.

CBI concepts were developed based on the self-congruity theory, highlighting individuals’ likeliness of comparing themselves with other objects and stimuli (F. Liu et al., Citation2012). Self-congruity means a fit between consumers’ self-concept and brand personality. This congruity makes consumers feel or experience while forming a consumer-brand relationship. Consumers tend to prefer and maintain a long-term relationship with a brand that has a consistent image of themselves (Aaker, Citation1995). Therefore, consumers always seek brands that carry an image that is consistent with/her own identity and self-concept, including an image that fits with how consumers want to be seen or perceived by others. Self-concept plays a prominent role in consumption behavior, as possessions or material objects can be viewed as extended self, personal expression, and indicators of group belonging (Cleveland et al., Citation2015). Hence, in social interactions, consumers strive to attach to their group members through brand choices (Carvalho et al., Citation2019).

Previous studies on CBI generally found a positive connection with consumers’ PI. While rational purchase decisions remain essential for consumers, brand identity allows for developing a positive attitude through the brand’s distinctive characteristics (Coelho et al., Citation2018). As an emotional reason, consumers see brands as an extension of themselves and help them to support their self-image, personality, and lifestyle (Coelho et al., Citation2018; Gurau, Citation2012). Also, consumers are concerned about what others think about them. This peer group determines their consumption choices and encourages them to choose the brands aligned with the image they want to portray in the social groups (Gurau, Citation2012; Lazarevic, Citation2012). The first hypothesis was proposed:

H1: CBI positively influences PI.

National identity

People need to feel recognized as a group, including a nation. In terms of a group, a nation meets human needs in the economy, social culture, and politics. A nation provides individuals with a sense of belongingness, security, and prestige (Druckman, Citation1994). Nationalism involves a desire for sovereignty and creates a collective sentiment or identity bounding. Nationality binds individuals who share a sense of large-scale national solidarity (Gellner, Citation2006; Marx, Citation2005). It provides a sense of group consciousness, the feeling of identifying with certain groups, whether in-group or out-group. Subsequently, nationalism raises the tendency to distinguish one group from another (Kamenka, Citation1973). Nationalism can be a feeling of anger aroused by the violation of principle or the feeling of satisfaction aroused by its fulfillment (Dugis, Citation1999). Although the early definition of nationalism emerged around tribalism, the contemporary definition is no longer based on ethnic, religious, historical, or geographical proximity. It is more concerned with shared values and principles and sometimes the combination of those two (Brubaker, Citation1992; Mylonas & Tudor, Citation2021). With this view, it is apparent that the critical marker of nationalism is grounded in the narratives of being loyal to that set of values preserving the nation (Bieber, Citation2018).

NI encompasses such a broad array of associations (both collective and individual) that it is bound to be characterized by an array of feelings, attitudes, and behavioral manifestations (Carvalho et al., Citation2019). NI consists of a set of cognitions and emotions that express an individual’s relationship with a nation (Barrett & Davis, Citation2008). Gerth (Citation2011) defines nationalism in the context of consumer behavior, accentuating that consumer nationalism refers to consuming their own nationally produced goods. This definition broadens the concept of nationalism from spirits related to a political movement to the more practical one. This definition emphasizes everyone’s behavior, even without political affiliation. While in the marketing context, strengthening NI becomes paramount as accelerated globalization brings advantages for multinational companies with a global reach. With their internal capabilities, these companies could reach the local markets with their marketing resources. Even they can adapt the local preferences by customizing brands that fulfill local needs.

Murshed (Citation2019) found that consumers’ NI strongly relates to local brand loyalty by providing cues that link with nationalism. Even in highly competitive low-involvement product categories, brands could achieve prestige over time due to their effective positioning as local brands (Coelho et al., Citation2018). Frequently advertised local brands also strengthen the feeling of belonging to the nation. The messages of being ‘local brands’ make people feel they must consume the brands due to the similarity with their nationalist values (Bulmer & Oliver, Citation2010). The second hypothesis was proposed:

H2: NI moderates (strengthens) the positive relationship between CBI and PI.

Religious identification and brand positioning

The sociocultural theory highlights the interplay between individuals’ faith and spirituality (i.e. personal identities). This theory asserted that spirituality intertwines with the larger cultural community context, such as rituals, ceremonies, and services (i.e. social identities) (Etengoff & Rodriguez, Citation2020). Indeed, the unique characteristics of group members do not exist in isolation and are inextricably linked to religious belief systems. Even the religious belief linkage is often stronger than other ideological belief systems (Ysseldyk et al., Citation2010). The intensity of religious identity influences people’s cognitive, behavioral, social, and affective variables. This influence grows as an individual develops her/himself within the nested system. This nested system serves as a microsystem alongside other social influences such as family and peers (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979; Palitsky et al., Citation2020). Religious identification is also often considered a manifestation of social identity. Hence, it provides cues of why religion is important; as such, people always seek religious justification for their behaviors during their daily life (Palitsky et al., Citation2020). In other words, religious identity refers to how individuals develop their sense of religion over their lifetime (Etengoff & Rodriguez, Citation2020).

Religious identity creates an emotional consumer attachment and generally develops pride in belonging to the community (McMillan & Chavis, Citation1986). Indeed, this sense of belonging motivates their consumption behavior (Coşgel & Minkler, Citation2004). Reciprocally, consumption choice assists individuals in solving the problem of how to convey their religious identities (Coşgel & Minkler, Citation2004). The development of a religious consumer society has driven marketers to incorporate religious brand positioning as individuals develop the need to belong (Mathras et al., Citation2016). The strategic positioning allows brands to serve as an outlet for personal expression and help individuals to indicate which groups they belong to Cleveland et al. (Citation2015). Companies develop the brand’s religious positioning in many ways. For instance, forever21 and chick-fil-A express their religious core values to their consumers through their communication materials and companies’ mission statements. Some companies prefer to express religious values more subtly, such as engaging in religious charity (R. L. Liu & Minton, Citation2018). Therefore, the religious branding concept effectively captures the religious target market. Religions have signs that may well be interpreted as brand logos, such as the cross for Christianity, the crescent for Islam, Ying-Yang for Taoism, and Lotus Flower for Buddhism (Stolz & Usunier, Citation2019).

The moderating role of religious brand positioning

As mentioned earlier, the relationship between nationalism and religions, rather than opposing each other, is a kind of continuum, as such individuals may have both nationalist and religious identities. Therefore, RBP was added as another moderator in the two-way interaction between NI and CBI to investigate whether religious positioning can strengthen the congruity between the brand and consumers’ NI. This three-way interaction also defines the boundaries in which RBP could affect this relationship.

Scholars developed an understanding of the relationship between nationalism and religion, describing the relationship as religion as not something outside nationalism but rather as a part that is intertwined, imbricated, and mutually coexisting (Brubaker, Citation1992; Mentzel, Citation2020). Rapid social changes threaten an individual’s self-identity, and the linking between religion and nationalism can be used to confront those periods of uncertainty (Kinvall, Citation2004). In some cases, even if nationalism becomes the primary motive of local consumption, religion becomes a supporting element of such a movement (Castelló & Mihelj, Citation2017; Rieffer, Citation2003). Kinvall (Citation2004) argued that nationalism and religion anchored people’s identity even when other aspects of their personal life may be fragmenting. The relationship between religiosity and the importance of claiming religion as a part of nationalism appears stable, which goes unmolested during modernization (Barry, Citation2020).

Religion offers its members a sense of identity that can be as important as nationalism. In fact, religion is one of the few essential elements of nationalism (Rieffer, Citation2003). Hence, in identity marketing, a religious positioning and nationalism approach could be deciding factors for consumption. A brand that positions itself as ‘being religious’ will likely strengthen consumers’ NI and foster emotional attachment, which goes beyond its functional value.

H3a RBP moderates the two-way interaction effects of NI and CBI such that the positive relationship between CBI and PI is stronger for brands with RBP among consumers with higher NI.

H3b RBP moderates the two-way interaction effects of NI and CBI such that the positive relationship between CBI and PI is weaker for brands without RBP among consumers with lower NI.

H3c The three-way interaction effect of CBI, NI, and RBP, whereby the positive relationship between CBI and PI is strongest when NI is high and when the brand possesses RBP.

displays the proposed structural model.

Methodology

Research design and data collection procedures

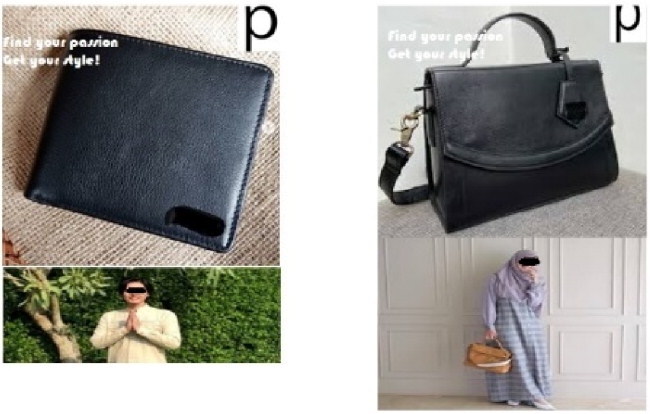

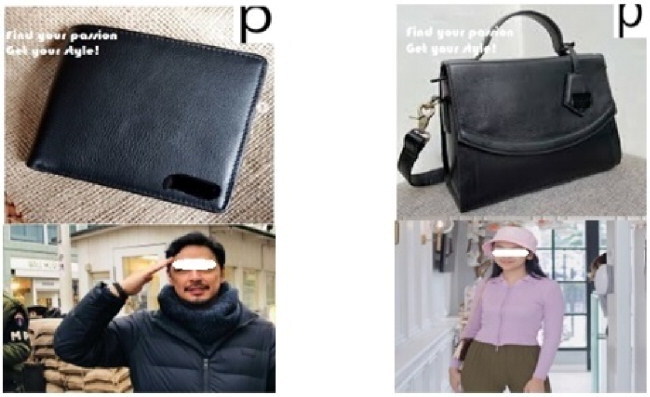

This present study employed a cross-sectional approach where a survey was conducted to collect the data. CBI, NI, and PI were measured using 5 points Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 =strongly agree). RBP was manipulated using dummy variables (0 = no RBP, 1 = with RBP). Three stimuli materials were used to help respondents in answering the questions. The first stimuli material was the brand advertising in the original form. The second was stimuli material displaying a nationalism cue (we used the official logo from the Indonesian Ministry of Tourism which informed the respondents that the brand is a 100% local product). The third stimuli materials displayed religious cues.

All three stimuli materials were presented in Appendix A. We put well-known Muslim, Catholic, and Christian celebrity figures in the stimuli materials to accommodate all respondents’ religious affiliations. Displaying a well-known religious figure effectively positions brands as ‘religious brands’ (Einstein, Citation2008), hence the stimuli conveyed the RBP. The instrument was developed based on previous studies and translated into Bahasa Indonesia. Back-translation was also applied to check the linguistic equivalence. In the first stage, the expert panel involving academicians and senior researchers was involved in assessing the scales. This help to ensure face and content validity (Odoom et al., Citation2020). Then, the stimuli materials and the scales were pre-tested on 30 respondents to ensure they recognized the nationalism cue and celebrities displayed in the stimuli materials. For celebrity figures, we proposed ten celebrities for each religious affiliation and asked the respondents to give their scores based on the celebrities’ perceived religiousness. The top-scored male and female celebrities were then chosen as the religious cue for stimuli materials. We also asked the respondents to read the questionnaire and revise the wording according to their suggestions.

According to the context of this study, we engaged with a small business owner located in Bogor Regency, producing clothes and apparel. This clothing apparel is a well-known local brand sold through social media (Facebook, Instagram). We request the owner’s permission to access their consumer database. We selected only consumers who made purchases within the last six months to ensure they could remember the brand they bought. We also asked for written permission to use two of their product items (each product for men and women) along with the brand logo in the stimuli materials with some modified advertising according to our objectives. Using the small business database, we could reach the respondents and request their participation in the survey. To effectively convey the messages of nationality, we only selected Indonesian consumers. Also, to avoid bias toward one religion, we chose Muslims, Catholics, and Christians, as these three religions represent the dominant religious affiliations in Indonesia. The respondents were invited to scheduled online meetings and were asked to fill out the online questionnaire during the meeting; thus, a proper understanding of the questions can be assured. We explained the objective of the survey with a request for consent to take part in the survey. The anonymity of the respondents was also assured. We offered monetary incentives to increase the response rate.

The respondents were divided into two groups. For the first group, we presented stimuli material 1 (the brand advertising in the original form) and asked respondents whether they could recall the brand name. We provided cues if they needed help remembering the brand name. Then we asked respondents to fill out the questionnaire in the CBI section. We then presented stimuli material 2 (stimuli with nationalism cue) to stimulate respondents’ nationalism and asked the respondents to complete the NI section. Again, we presented stimuli material 1 and asked the respondent to fill in the RBP and PI sections. We carried the same procedure for the second group. However, we presented both stimuli material 1 and stimuli material 3 (stimuli with the religious cue) before asking the main questions. To ensure the manipulation works effectively, we asked the respondents to give a score between 1 and 5 regarding the degree of the perceived religious image conveyed by both stimuli material 1 and 3 (1 = not religious at all, 5 = very religious). We again displayed stimuli material 3 before asking the respondents to complete the PI section. After three months, the survey collected 403 usable responses consisting of 198 respondents from group 1 and 205 respondents from group 2.

Questionnaires and measures

The questionnaire consists of three sections. The first section is the background of the study, including the request for consent to participate in the survey. The second section focuses on demographic profiling, which includes name and contact number (optional), religion, age, sex, monthly spending, education, and occupation. The third section contains the main questions of this study, employing five scales of Likert items (1: very disagree, 5: very agree). The CBI scales were adapted from Sauer et al. (Citation2012) and contain five items that have been validated by Popp and Woratschek (Citation2017). The CBI scales capture to what extent the brand shares the same identity and values with the consumers. The NI scales were adapted from Lilli and Diehl (Citation1999), containing eight items that reflect the collective identity as a nation. We created a dummy variable to represent RBP in which 0 = no religious cue and 1 = with religious cue. The PI scales were adapted from Duffet (Citation2015) and contain five items indicating the degree to which consumers will buy the brands. displays the variables’ definitions and their respective indicators.

Table 1. Variables and indicators.

Data analysis

SPSS 24.0 and Amos 22.0 were used in the data analysis. Hypothetical constructs were estimated as common factors assumed to cause their indicators (i.e. observed, or manifest variables) (Zhang et al., Citation2020). Further, this technique allows us to assess the relationship between variables. Thus, it derives a conclusion and formulates practical implications for managers and business owners (Hair et al., Citation2019). Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were employed to assess the sampling adequacy. Next, the common-method bias (CMB) was examined using Harman’s single-factor test to avoid systematic measurement error, leading to a spurious correlation between constructs (Cote & Buckley, Citation1987). Then, multicollinearity was assessed as it could increase parameter variance estimates, produce incorrect parameter estimates and implausible magnitude, and prevent the numerical solution of a model (Greene, Citation2000). This study involved large samples (more than 200 respondents); therefore, the central limit theorem could be applied. Hence the data distribution tends to be normal regardless of the shape (Field, Citation2009; Elliott & Woodward, Citation2007). The data analysis involves two steps. Firstly, the measurement model was examined by employing convergent and discriminant validity assessments. Secondly, hierarchical multiple regression was examined to assess the relationship between variables and to test the proposed hypotheses.

Results

Respondent’s demographic profiles

The respondents involved in this study were mainly ‘between 18 and 25 years old’ (35.92%), followed by ‘26 and 35 years old’ (23.06%). There were 77.67% Muslims, 9.71% Christians, and 10.44% Catholics; hence, the respondents represent Indonesia’s three major religious affiliations. Most respondents were female (51.70%) and mostly spent ‘between IDR 3 and 6 million’ monthly (39.56%). Most respondents have bachelor’s degrees (49.27%) and work in the private sector (32.52%). displays the respondent’s demographic profile.

Table 2. Respondents’ demographic profile.

Manipulation check, sampling adequacy, common method bias, and multicollinearity

The manipulation check was conducted using an independent sample t-test to ensure the religious cue worked as intended. The result showed a significant difference in the scores between no RBP and with RBP (t = 3.04; p < 0.012). The result implied that the stimuli materials effectively manipulated the respondent’s perception according to the intended purpose.

The KMO assessment of sampling adequacy showed a good value of 0.807. Hence the variables present a strong partial correlation. Bartlett’s test of sphericity also showed a significant value (p = 0.000); thus, the correlation matrix was not an identity matrix. Therefore, the data was suitable for factor analysis and could be further processed into a hypotheses assessment (Field, Citation2009). Subsequently, Harman’s one-factor test was employed to examine the common method bias, where all the items were entered into unrotated PCA. The first component with the largest eigenvalue explains 29.66% of the variance, which does not exceed the recommended cutoff value of 50 percent for all variances. This result indicates that common method bias was not an issue in this study (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). Subsequently, the predictors were introduced to multicollinearity assessment and showed that all tolerance values exceeded the minimum recommended value of 0.2 (Menard, Citation1995) (CBI = 0.691; NI = 0.568). Also, all indicators’ variance inflation factors (VIF) were below the maximum cutoff value of 10 (Hair et al., Citation1995) (CBI = 2.67; NI = 2.29). Therefore, multicollinearity was not an issue in this present study.

Convergent validity and discriminant validity

To further ensure the validity and reliability of the measurement, we further assess the convergent and discriminant validity, which help to establish a credible research design (Hair et al., Citation2014). The convergent validity assessment calculated the factor loading of each item, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE). As displayed in , the loading values were above 0.5, CR values were above 0.7, and the AVE was above 0.5, as Hair et al. (Citation2014) recommended. The goodness of fit also showed adequate fit (RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.05, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.95). Therefore, internal consistency for each construct was assured, and each item does measure the intended construct. Next, we assessed the discriminant validity using Fornell and Larcker criterion. As displayed in , the Fornell and Larcker criterion indicates that the square root of AVE for each construct was higher than the inter-construct correlations. The items related more strongly to their respective construct (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981).

Table 3. Convergent validity.

Table 4. Discriminant validity.

Hypothesis testing

We employed a four-step moderated hierarchical multiple regression analysis using Preacher and Hayes’s (Citation2008) PROCESS macro with 1.000 bootstrapped samples to test the proposed hypotheses. Step 1 controlled the age, religion, sex, monthly spending, education, and occupation. Step 2 added the main predictor (CBI). Step 3 examined the two-way interaction by adding NI as the first moderator. Step 4 examined the three-way interactions by adding RBP as the second moderator. All predictors were mean-centered to reduce the multicollinearity during moderation analysis and to achieve convergence during the moderated multiple regression analysis (Dalal & Zickar, Citation2012). displays the hierarchical multiple regression.

Table 5. Hierarchical multiple regression.

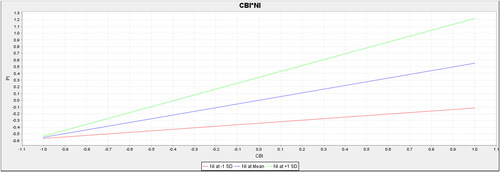

From the main effect regression (step 2), after controlling the age, religion, sex, monthly spending, education, and occupation, it is found that CBI positively influences PI (β = 0.320, p < 0.001). Therefore, the first hypotheses were accepted. Next, step 3 added NI as the moderator on the relationship between CBI and PI. It is found that NI positively moderates (strengthens) the positive relationship between CBI and PI (β = 0.328, p < 0.01). It is also found that the r2 increases by 0.022, indicating that more variation in PI could be explained by moderated interaction between CBI and NI than those of CBI alone. Therefore, the second hypothesis was accepted.

Further, displays the moderated interaction, showing the simple slope difference on the effect of CBI under high or low (±1SD) levels of NI. A steeper slope indicates that when NI is high (+1 SD), CBI has a stronger positive effect on the PI. In contrast, when NI is low (−1SD), CBI has a weaker positive effect on the PI. It implies that when the brand carries a national identity, it provides a stronger persuasion to purchase.

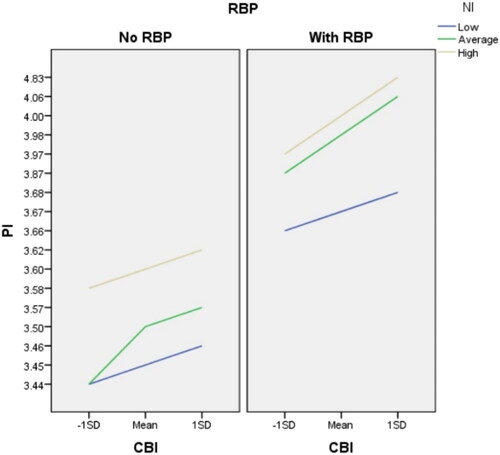

We assessed the three-way interaction effect between CBI, NI, and RBP. As seen in , the three-way interaction significantly affects the PI (β = 0.203; p < 0.05). Also, the r2 increases by 0.012, indicating that the three-way interaction between RBP, CBI, and NI could explain more variation in PI. We performed group analysis to examine the three-way interaction under two scenarios (no RBP vs. with RBP). The result showed that the two-way interaction between CBI and NI was not significant for no RBP (β = 0.011, t = 0.12, p = 0.83, f2 = 0.014). On the contrary, the two-way interaction was significant for with RBP (β = 0.12, t = 1.72, p = 0.015, f2 = 0.15). More precisely, in no RBP scenario, the effect of CBI on PI was nearly equal at low NI vs. high NI (β = 0.22, t = 1.34, p < 0.05 at low NI vs. β = 0.31, t = 1.54, p < 0.005 at high NI). On the other hand, in with RBP scenario, there is a significant difference in effect size between low NI vs. high NI (β = 0.29, t = 1.61, p < 0.001 at low NI vs. β = 0.43, t = 2.03, p < 0.000 at high NI). Therefore, H3a and H3b were accepted.

Further, we plotted the simple slope of two scenarios (no RBP vs. with RBP) to investigate the difference in the interaction between NI, CBI, and PI. shows that the brand with RBP at any given CBI has a more significant effect on PI, either at high, average, or low NI, compared to no RBP. Consistent with our previous analysis, the simple slope test revealed that the difference between low NI-no RBP and high NI-no RBP was insignificant (p > 0.05). In contrast, the slope difference between low NI-with RBP and high NI-with RBP was significant (p < 0.05). The positive influence of CBI on PI was the strongest among consumers with high NI and was exposed to with RBP (β = 0.203, t = 1.22, t < 0.05). Therefore, H3c was accepted. The religious cue within a brand does not weaken the consumers’ nationalism and self-identification. Overall, a brand with a religious positioning exerts a stronger influence on consumers to purchase.

Discussion

The main idea of this present study was the vital role of congruency between brands and consumer identity. Further, this study seeks to understand the interaction between two seemingly contradictory identities; they are nationalism and religion. The three-way interaction effects between CBI, NI, and RBP were applied to investigate their effects on consumers’ PI under different scenarios. Our results revealed that all hypotheses were accepted.

This first hypothesis assessment confirms the findings from (Coelho et al., Citation2018; Gurau, Citation2012), which asserted that consumers always seek brands that fit their self-image, personality, and lifestyle. This present study uses apparel products as stimuli which could be categorized as low-involvement products. Consistent with the findings from (Coelho et al., Citation2018), consumers make purchasing decisions based on both functional benefits and emotional attachment. Also, more than 40% of the respondents come from the millennial generation (below 25 years old) and are more likely to seek brands that align with their personalities (Gurau, Citation2012). This emotional attachment reinforces the possibility of creating CBI, which develops consumers’ positive attitudes toward the brand.

The second hypothesis was also supported, accentuating that brands that carry nationalism cues strengthen the relationship between CBI and PI. The result was in line with those of Murshed (Citation2019), Coelho et al. (Citation2018), and Bulmer and Oliver (Citation2010). NI is associated with a sense of oneness with a nation, as respondents are aware of and accept that they belong to a nation (Carvalho et al., Citation2019). Likewise, brands that carry nationalism cues (such as slogans ‘helping national small business to recover or 100% local products’) in their promotion materials strengthen the congruity with the consumers. The brands guide the consumers’ emotional attachment by associating them with the nation they belong to. Moreover, this present study used a well-known local brand as a stimulus. As Murshed (Citation2019) argued, the local cues and nationalism messages promote consumers’ PI by activating their commitment to purchase local brands. Therefore, NI could help brands to win the competition even in a competitive low-involvement product category, mainly due to its affective positioning (Coelho et al., Citation2018).

Next, the three-way interaction assessment revealed a positive interaction between nationalism and religion. The seemingly contradictory identities were proved to be strengthening each other. The respondents feel that a perceived brand positioning strengthens their nationalism. The interaction eventually strengthens the interaction between CBI and PI. The result also showed that regardless of the respondent’s religious affiliation, nationalism and religious approaches could provide similar self-identification with the brands. It confirmed Kinvall (Citation2004) argument, which stated that nationalism and religion play an important role in people’s identity. The result also confirmed the argument from Barry (Citation2020), accentuating that religion has become a part of NI and goes unwavering during societal changes. In the context of local brands, respondents’ NI and religious value could become a primary motive for consumption (Castelló & Miheli, 2017). To some extent, religious value is in line with nationalism and plays a supporting element in a specific movement, such as promoting local consumption to accelerate economic recovery.

Conclusion

This present study revealed that both nationalism and religious identities could be co-existent within the brands and consumers. CBI was proven to influence PI positively. NI also strengthens the relationship between CBI and PI. Further, the three-way interactions revealed that brands with RBP create a stronger moderation effect of NI toward the relationship between CBI and PI. This study extends the brand-consumer research stream and sheds light on the interaction effects between two identities that seem to contradict each other. Our results revealed that individuals could possess both nationalism and religious identities. In marketing practice, the two identities do not reject each other nor weaken the overall brand messages. Marketers could develop communication strategies that involved both nationalism and religious context. These two approaches strengthen the consumers’ identification with the brand, increasing their intention to purchase.

Marketers may anchor their brand positioning strategies by emphasizing nationalism or religious cues. Moreover, marketers may find it beneficial to develop a thematic campaign emphasizing nationalist spirits, aiming to boost sales within specific periods without endangering the engraved brand positioning. Likewise, marketers could position their brands as ‘being local’ or national while customizing the promotion during religious festivals to create more engagement with the religious segments. In line with this study’s context, the findings contribute to a more flexible yet effective promotion strategy for small business owners to restore their business performance after the Covid-19 pandemic. For the government, the results contribute to policy insights that aim to increase small business knowledge and competencies in crafting the identity-based marketing campaign. As small businesses contribute to more than 90% of national business types, the revival of this sector will accelerate the national economic recovery.

Limitations and direction for further studies

This study has several limitations that future studies may address. This study only involved a low-involvement product category. The low-involvement product generally involves a minimum thought and effort; hence the consumers may purchase the brands as it represents a self-congruity without any other considerations such as price. Further study can investigate the nationalism and religious approach as it may provide different magnitudes for consumers in the high-involvement product category. Also, price variables can be included to examine the boundaries which limit the effect of nationalist and religious identities on purchasing behavior.

This study used fictitious advertising, which limits generalizability. In fact, consumers are exposed to cluttering advertisings in the marketplace. Further studies could investigate the type of advertising which could promote both nationalism and religious identity effectively in high-intensity advertising exposure settings. This present study only involved one product category (apparel). Further study may use stimuli within another product category as the consumers’ identification effect may provide different results.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Fachrurazi

Fachrurazi serves as a lecturer and researcher in the fields of Entrepreneurship – SMEs, Islamic Economics, Management, and Finance at the State Islamic Institute of Pontianak. Fachrurazi has also been actively involved for years in research, educational policy, and community economic empowerment at both local and national levels.

Sahat Aditua Fandhitya Silalahi

Sahat Aditua Fandhitya Silalahi is a senior researcher at the Center for Cooperative, Corporate, and People’s Economy, National Research and Innovation Agency. He has a keen interest in research in the fields of entrepreneurship, business and management, as well as small and medium enterprises.

Fauziah

Fauziah is a faculty member at the Faculty of Islamic Economic and Business IAIN Pontianak. In addition to teaching, she is also actively serving as the head of the internal supervision unit. Fauziah has a keen interest in the study of Islamic preaching, culture, and civilization.

References

- Aaker, D. A. (1995). Building strong brands. Free Press.

- Ahearne, M., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Gruen, T. (2005). Antecedents and consequences of customer-company identification: Expanding the role of relationship marketing. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(3), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.3.574

- Barrett, M., & Davis, S. C. (2008). Applying social identity and self-categorization theories to children’s racial, ethnic, national, and state identifications and attitudes. In S. M. Quintana & C. McKown (Eds.), Handbook of race, racism and the developing child (pp. 72–110). Wiley.

- Barry, M. (2020). The relationship between religious nationalism: A survey of post communist Europe. Journal of Developing Societies, 36(1), 77–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0169796X20902309

- Bieber, F. (2018). Is nationalism on the rise? Assessing global trends. Ethnopolitics, 17(5), 519–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2018.1532633

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). Contexts of child rearing: Problems and prospects. American Psychologist, 34(10), 844–850. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.844

- Brubaker, R. (1992). Citizenship and nationhood in France and Germany. Harvard Univ. Press.

- Bulmer, S. & Oliver, B. M. (2010). Experiences of bands and national identity. Australian Marketing Journal, 18(4), 199–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2010.07.002

- Busse, A. G. (2019). Religious nationalism and religious influence. Oxford University Press.

- Carvalho, S. W., Luna, D., & Goldsmith, E. (2019). The role of national identity in consumption: An integrative framework. Journal of Business Research, 103, 310–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.01.056

- Castelló, E., & Mihelj, S. (2017). Selling and consuming the nation: Understanding consumer nationalism. Journal of Consumer Culture, 18(4), 558–576. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540517690570

- Central Bureau of Statistics. (2022). Official release on economic development 2021. Central Bureau of Statistics.

- Chen, L., Halepoto, H., Liu, C., Kumari, N., Yan, X., Du, Q., & Memon, H. (2021). Relationship analysis among apparel brand image, self-congruity, and consumers’ purchase intention. Sustainability, 13(22), 12770. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212770

- Cleveland, M., Laroche, M., & Takahashi, I. (2015). The interplay of local and global cultural influences on Japanese consumer behavior. In C. L. Campbell (Ed.), Marketing in transition: Scarcity, globalism, &sustainability (p. 438). Springer International Publishing.

- Coelho, P. S., Rita, P., & Santos, Z. P. (2018). On the relationship between consumer-brand identification, brand community, and brand loyalty. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 43, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.03.011

- Coşgel, M. M., & Minkler, L. (2004). Religious identity and consumption. Review of Social Economy, 62(3), 339–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034676042000253945

- Cote, J. A., & Buckley, M. R. (1987). Estimating trait, method, and error variance: Generalizing across 70 construct validation studies. Journal of Marketing Research, 24(3), 315–318. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151642

- Dalal, D. K., & Zickar, M. J. (2012). Some common myths about centering predictor variables in moderated multiple regression and polynomial regression. Organizational Research Methods, 15(3), 339–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428111430540

- Druckman, D. (1994). Nationalism, patriotism, and group loyalty: A social psychological perspective. Mershon International Studies Review, 38(1), 43–68. https://doi.org/10.2307/22261

- Duffet, Y. R. G. (2015). The influence of Mxit advertising on purchase intentions and purchase amid generation Y.R.G. Journal of Contemporary Management, 12(1), 336–359.

- Dugis, V. M. A. (1999). Defining nationalism in the era of globalization. Masyarakat Kebudayaan Dan Politik, 12(2), 51–57.

- Einstein, M. (2008). Brands of faith: Marketing religion in a commercial age (p. 92). Routledge.

- Elliott, A. C., & Woodward, W. A. (2007). Statistical analysis quick reference guidebook with SPSS examples (1st ed.). Sage Publications.

- Etengoff, C., & Rodriguez, E. M. (2020). Religious identity: Development on the self in adolescence identity. In S. Hupp & J. D. Jewell (Ed.), The encyclopedia of child and adolescent development (pp. 1–10). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119171492.wecad458

- Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS (3rd ed.). Sage Publications Ltd.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

- Gellner, E. (2006). Nations and nationalism (2nd ed.). Blackwell. (Original work published 1983).

- Gerth, K. (2011). Consumer nationalism. In D. Southerton (Ed.). Encyclopedia of consumer culture (pp. 280–282). SAGE.

- Greene, W. H. (2000). Econometric analysis (4th ed.). Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

- Gurau, C. (2012). A life stage analysis of consumer loyalty profile: comparing Generation X and Milennial consumers. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 29, 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761211206357

- Hair, J. F. J., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., Black, W. C. (1995). Multivariate data analysis, 3rd ed. MacMillan.

- Hair, F., Jr., Sarstedt, J., Hopkins, L. M., & Kuppelwieser, G. V. (2014). Partial last squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Ichwan, M. N., Salim, A., & Srimulyani, E. (2020). Islam and dormant citizenship: Soft religious ethno-nationalism and minorities in Aceh, Indonesia. Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations, 31(2), 215–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/09596410.2020.1780407

- Japutra, A., Ekinci, Y., Simkin, L., & Nguyen, B. (2018). The role of ideal self-congruence and brand attachment in consumers’ negative behaviour: Compulsive buying and external trash-talking. European Journal of Marketing, 52(3/4), 683–701. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-06-2016-0318

- Juergensmeyer, M. (2010). The global rise of religious nationalism. Australian Journal of International Affairs, 64(3), 262–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357711003736436

- Kaap-Deeder, J., Vansteenkiste, M., Van Petegem, S., Raes, F., & Soenens, B. (2016). On the integration of need-related autobiographical memories among late adolescents and late adults: The role of depressive symptoms and self-congruence. European Journal of Personality, 30(6), 580–593. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2079

- Kamenka, E. (Ed.). (1973). Nationalism, the nature, and evolution of an idea. ANU Press.

- Kim, C. K., Han, D., & Park, S. B. (2001). The effect of brand personality and brand identification on brand loyalty: Applying the theory of social identification. Japanese Psychological Research, 43(4), 195–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5884.00177

- Kinvall, C. (2004). Globalization and religious nationalism: Self, identity, and the search for ontolofical security. Political Psychology, 25(5), 741–767. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2004.00396.x

- Lazarevic, V. (2012). Encouraging brand loyalty in fickle generation Y consumers. Young Consumers, 13(1), 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1108/17473611211203939

- Lilli, W., & Diehl, M. (1999). “Measuring national identity” Arbeitspapiere (Working Paper), Mannheimer Zentrum für Europäische Sozialforschung, No. 10 (pp. 1–11).

- Liu, F., Li, J., Mizerski, D., & Soh, H. (2012). Self-congruity, brand attitude, and brand loyalty. European Journal of Marketing, 46(7/8), 922–937. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561211230098

- Liu, R. L., & Minton, E. A. (2018). Faith filled brands: The interplay of religious branding and brand engagement in the self-concept. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 44, 305–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.07.022

- Marx, A. (2005). Faith in nation: Exclusionary origins of nationalism. Oxford Univ. Press.

- Mathras, D., Cohen, A. B., Mandel, N., & Mick, D. G. (2016). The effects of religion on consumer behavior: A conceptual framework and research agenda. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 26(2), 298–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2015.08.001

- McMillan, D. W., & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 14(1), 6–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6629(198601)14:1<6::AID-JCOP2290140103>3.0.CO;2-I

- Menard, S. (1995). Applied logistic regression analysis (Sage university paper series on quantitative application in the social sciences, series no. 106) (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Mentzel, P. C. (2020). Religion and nationalism? Or nationalism and religion? Some reflections on the relationship between religion and nationalism. Genealogy, 4(4), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4040098

- Morgan, N. A., & Rego, L. L. (2009). Brand portfolio strategy and firm performance. Journal of Marketing, 73(1), 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.73.1.59

- Murshed, N. A. (2019). Nationalism role on local brands preference: Evidences from Turkey clothes market. International Journal of Science and Research, 8(11), 259–269. https://doi.org/10.21275/ART20202447

- Mylonas, H., & Tudor, M. (2021). Nationalism: What we know and what we still need to know. Annual Review of Political Science, 24(1), 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-101841

- Odoom, R., Agbemabiese, G. C., & Hinson, R. E. (2020). Service recovery satisfaction in offline and online experiences. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 38(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-09-2018-0422

- Palitsky, R., Sullivan, D., Young, I. F., & Schmitt, H. J. (2020). Religion and the construction of identity. K. E. Vail & C. Routledge (Ed.), The science of religion, spirituality, and existentialism (pp. 207–222). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-817204-9.00016-0

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Popp, B., & Woratschek, H. (2017). Consumer-brand identification revisited: An integrative framework of brand identification, customer satisfaction, and price image and their role for brand loyalty and word of mouth. Journal of Brand Management, 24(3), 250–270. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-017-0033-9

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

- Rieffer, B. A. (2003). Religion and nationalism. Ethnicities, 3(2), 215–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796803003002003

- Sauer, N. S., Ratneshwar, S., & Sen, S. (2012). Drivers of consumers brand identification. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 29(4), 406–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2012.06.001

- Shokri, M., & Alavi, A. (2019). The relationship between consumer-brand identification and brand extension. Journal of Relationship Marketing, 18(2), 124–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332667.2018.1534064

- Sirgy, M. J., Johar, J., Samli, A. C., & Claiborne, C. B. (1991). Self-congruity versus functional congruity: Predictors of consumer behavior. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 19(4), 363–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/009207039101900409

- Smith, A. D. (1999). Ethnic election and national destiny: Some religious origins of nationalism ideals. Nations and Nationalism, 5(3), 331–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1354-5078.1999.00331.x

- Soper, J. C., & Fetzer, J. S. (2018). Religion and nationalism in global perspective. University Press.

- Stolz, J., & Usunier, J. C. (2019). Religion as brands? Religion and spirituality in consumer society. Journal of Management, Spirituality, and Religion, 16(1), 6–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2018.1445008

- Vikas, K., & Nayak, J. (2014). The role of self-congruity and functional congruity in influencing tourists’ post visit behaviour. Advances in Hospitality and Tourism Research, 2(2), 24–44.

- Wassler, P., Wang, L., & Hung, K. (2019). Identity and destination branding among residents: How does brand self-congruity influence brand attitude and ambassadorial behavior? International Journal of Tourism Research, 21(4), 437–446. https://doi.org/10.1002/jty.2271

- Ysseldyk, R., Matheson, K., & Anisman, H. (2010). Religiosity as identity: Toward an understanding of religion from a social identity perspective. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868309349693

- Zhang, M. F., Dawson, J. F., & Kline, R. B. (2020). Evaluating the use of covariance-based structural equation modeling with reflective measurement in organizational and management research: a review and recommendations for best practice. British Journal of Management, 32(2), 257–272. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12415

Appendix A:

Stimuli materials

Stimuli 1 The original brand advertising

Stimuli 2 With nationalism cue

Stimuli 3 With religious cue Muslims

Catholics

Christians