?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Courts are high-stakes institutions, where the influence of the use of legal technology (legaltech) may not be confined to the individuals utilizing the tools. The existing evidence is insufficient for predicting the approval of legaltech in court proceedings. We aimed to provide empirical support for utilizing the technology acceptance model by recognizing individuals’ perceptions of legaltech in court proceedings. Furthermore, we suggest possible distinctions in these perceptions between those with and without court experience, in the legal field versus others, men versus women, and younger versus older individuals. This study’s main purpose is to offer important insights into the determinants that impact the acceptability of legal technology within the Vietnamese court system. The findings were examined by applying the partial least squares structural equation modelling technique. Based on the results, the acceptance of technology in court proceedings is mostly influenced by views on its utility. Furthermore, trust is crucial and is influenced by perceived risk and expertise. It is recommended that policymakers and court administrators prioritize the enhancement of these aspects to promote the acceptance and utilization of legal technology in Vietnam’s courts, leading to more efficient and impactful judicial procedures.

1. Introduction

In recent years, attorneys have adopted new technologies, with legal technology (legaltech) facilitating the sector’s digital transformation. This requirement has become more apparent as courts have transitioned to operating electronically and virtually, a trend that will continue for the foreseeable future. This was a major factor in accelerating the adoption of legaltech by the sector as lawyers had to adapt to the changing legal environment and individuals’ needs and expectations. Business reports imply that in 2018, legaltech expenditure reached USD 1 billion, which is approximately four times more than the previous year (USD 233 million in 2017). This reflects the potential advantages of employing information technology solutions tailored to the legal industry. The global market for legal services is projected to grow to a record-breaking USD 1.011 trillion by 2021, from USD 925 billion in 2019, USD 886 billion in 2018, and USD 849 billion in 2017. Therefore, one could conclude that the future of the legal services sector is moving toward a technological revolution involving a business model change, process automation, and employment reduction (Bourke et al., Citation2020).

The incorporation of legaltech has provided the legal industry with numerous benefits, including e-filing systems and digital management of cases systems, which streamline and expedite court processes. This expedites case resolution, reduces the congestion of pending proceedings, and ensures that citizens receive justice timeously (Hartung et al., Citation2017). Access to justice can be improved for all individuals, specifically those in remote locations or with physical disabilities, through the use of new technologies. By allowing individuals to participate in court proceedings without their physical presence, online platforms, and video conferencing facilities promote inclusivity and accessibility. The use of technology can increase court proceedings’ openness and guarantee that they are fair and impartial (Abramovsky & Griffith, Citation2006). Digital court records, online access to case information, and live broadcasting of hearings can increase public confidence in the judicial system and promote court officials’ sense of accountability. Courts can efficiently organize and evaluate vast amounts of records regarding cases, judgments, and court decisions with the incorporation of digital systems and legaltech (Corrales et al., Citation2019). This allows for improved decision-making, the identification of patterns or trends, and the creation of more effective legal strategies. Utilizing new technologies in the court system can result in long-term cost savings (Corrales et al., Citation2019). Automated processes, paperless systems, and digital documentation reduce administrative costs, storage expenses, and the need for a physical infrastructure. Furthermore, the prime minister of Vietnam issued Decision No. 749/QD-TTg on the implementation of the National Digital Transformation Program through 2025, achieving it by 2030. Vietnam is one of the most advanced nations in the ASEAN region and in the top 50 countries in the world for digital transformation, application of novel technologies, and innovations; and will have established itself as the leading country in the region in a variety of sectors, including the legal judiciary (Bui & Nguyen, Citation2022).

According to Collins and Moons (Citation2019), technological advancements can make justice more accessible to the people and less complicated for the courts, which confront a multitude of challenges. For instance, Brazil has a whopping 78 million litigations pending (Brehm et al., Citation2020). Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic, which adversely affected mobility over the last 2 years (Legg, Citation2021), further highlighted the practical challenges of jurisprudence and the necessity for simple instruments, and thus, forced courts to employ technology (Muhlenbach & Sayn, Citation2019). The legaltech being used by court systems is currently extremely advanced. Before the pandemic, courts in a few nations were already utilizing such technology. Some Canadian provinces, for instance, were already utilizing algorithms to settle small claims. Similarly, Estonia stated that it was developing a minor claims algorithm to alleviate the court backlog. The United States also utilized programs that assist with risk assessment suggestions (Xu & Wang, Citation2021). Additionally, China utilized a dataset to alert a jury if a paragraph deviated greatly from the sentencing of historical cases and then created an e-court system (Dwivedi et al., Citation2021). Finally, even Vietnam itself already possessed an electronic filing system (Intellectual Property Office of Vietnam, Citation2020). Ideally, the decision regarding the use of technology in court proceedings should be largely based on jurimetrics data, including a meticulous review of the court rulings that included and excluded the technology instrument. However, the relevant data may not be accessible when making the initial decision to design or evaluate the instruments.

Almost all contentious aspects within the subject of legaltech, including evolutionary algorithm law and legislation on intelligent machines, are managed by people. However, individuals vary in their involvement within the judicial system and their impact on judicial decisions.

Similarly, other problems arise because humans are necessary for the creation and application of technology, and technology may be challenging for humans. For instance, legaltech necessitates new knowledge and abilities (Dubois, Citation2021; Suarez, Citation2020); however, few educational institutions provide courses or modules in legaltech (Ryan, Citation2021). The analysis was performed with PLS-SEM modeling. The correlation between hedonic motivation and behavioral intention is the strongest, followed by the correlation between perceived effectiveness and hedonic motivation. Improving the original Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology model is influenced by age, gender, and experience. By activating social support networks, universities can provide students with an enjoyable m-learning experience, according to the findings (Sitar-Tăut, Citation2021). Although several attorneys are able to adapt to the increasing technologically enhanced competition among legal advisory services, some are resistant to the shift (Brooks et al., Citation2020; Jalil & Sheriff, Citation2020; Muhlenbach & Sayn, Citation2019). Additionally, human behavioral and cognitive idiosyncrasies may distort the intended usage of the instrument (Engel & Grgić-Hlača, Citation2021). Therefore, understanding human perceptions and attitudes regarding related technologies may be necessary for the successful development and deployment of court proceedings technology.

Therefore, it is crucial to investigate people’s perceptions towards legaltech before implementing them. Notably, court clients and attorneys may be dissatisfied with the most advanced technology (Sandefur, Citation2019). However, there have been few studies on the perception of advanced legaltech; one study was undertaken to encapsulate the moral considerations of using technology within the legal system (Zhang et al., Citation2022), and two qualitative studies have analyzed the acceptability of using robotic lawyers in private legal practice (Fu & Mishra, Citation2022; Wang et al., Citation2018).

The technology acceptance model (TAM; Davis, Citation1989) has been implemented in many forms in numerous industries (Gunasinghe et al., Citation2019; Wang et al., Citation2021; Xu & Wang, Citation2021). Although legaltech has been in use for more than 20 years, there is a lack of research on its public perceptions. While some legaltech is created exclusively for lawyers, other types are geared towards automated application submission or other operations that concern customers and not legal professionals. Furthermore, there has been no definitive response to questions regarding people’s effect on court procedures and the use of artificial intelligence, as the public can lack the requisite knowledge or experience (Deeks, Citation2019). Technology acceptance appears to be the most accurate term, as it can be of interest to researchers, entrepreneurs, and policymakers; the elements of acceptance and use can drive the configuration of advanced technology and forecast its reception (Taherdoost, Citation2018).

Few studies have experimentally examined legaltech’s acceptability (Fu & Mishra, Citation2022; Xu & Wang, Citation2017). Together, the findings of the aforementioned investigations (Tian et al., Citation2023) and another study provided the result that the widely applied technology acceptance paradigm (Ammenwerth, Citation2019; Hasani et al., Citation2017) is applicable to the legaltech sector. In the entire sample, the assumptions about the key TAM3 constructs—perceived usefulness of technology, perceived utility, and ease of use—were confirmed. Notably, the performance expectancy to employ the technology was operationalized as the intensity of one’s intent to use legaltech in court proceedings. Therefore, for people to accept legaltech in court proceedings, they must regard the technology as both valuable and convenient to use.

Although there have been studies on the adoption of technology in various industries in Vietnam, there are substantial gaps in the research regarding the influencing factors of acceptance of legaltech in Vietnam’s courts. Given the growing significance of technology in the legal industry and the potential benefits that technology adoption could bring to Vietnam’s judicial system, this gap is particularly significant. We seek to fill this gap by undertaking an exhaustive analysis of the factors that influence the adoption of legaltech in Vietnam’s courts, including perceived usefulness, perceived simplicity of use, and social influence. In this manner, our study can offer valuable insights into the challenges and opportunities associated with legaltech adoption in Vietnam, thereby informing the development of effective strategies to promote technology adoption in the country’s judicial system.

The TAM3 facilitates an understanding of the factors that influence user acceptance of new technologies (Davis et al., Citation1989; Venkatesh, Citation2000). In today’s fast-paced and rapidly changing technological environment, it is more essential than ever to comprehend how users perceive and adopt new technologies. The TAM3 provides a comprehensive framework for analyzing user acceptance, thereby helping organizations obtain valuable insights into the factors that influence user acceptance, enabling them to create and implement more effective strategies to promote the adoption of new technologies. This can ultimately result in increased productivity, innovation, and competitive advantage in the technology-driven law sector.

In spite of these issues, there is a dearth of empirical research examining how various individuals perceive legaltech in court proceedings. Consequently, this article investigates whether the acceptance and use of technology among individuals of various attributes, including age, gender, court expertise, and legal occupations may be used to assess the applicability of legaltech in a court system.

This research aims to contribute to the burgeoning subject of legaltech by investigating the acceptance of adoption of the technology in court proceedings among various demographic groups. It presents the conceptual contribution by evaluating the reliability of the TAM3 (Davis et al., Citation1989; Venkatesh, Citation2000) in the court setting for various demographic groups. In addition, relevant factors including perception risk and technology trust were added to the TAM3. Integrating expectations of equality into the methodological approach facilitated reflection on the perceptions of equality in court proceedings. Finally, examining individual inventiveness, age, judicial experience, and occupation (lawyer vs. others) enables one to comprehend the prospective distinctions between various types of individuals.

2. Conceptual framework foundation

2.1. The theories of technology acceptance model (TAM)

The concept of technology acceptance is not novel (Taherdoost, Citation2018), and the TAM is one of the simplest and most favored models used to explore the intention to adopt technology in many fields (Davis et al., Citation1989; Venkatesh, Citation2000; Wu et al., Citation2011). There are over 20 meta-analyses of TAM (Xiao & Ke, Citation2021), and several studies have examined the acceptance and use of technology in various domains. TAM has already been utilized within the legal domain (Fu & Mishra, Citation2022; Wang et al., Citation2018), albeit only in qualitative investigations and with a singular focus on the automation of attorneys.

Davis created TAM to identify the characteristics that drive user acceptance of technology (Muhlenbach & Sayn, Citation2019). TAM is a generally acknowledged model for defining user technology acceptance, supported by considerable empirical research. Two specific criteria, perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use, have been introduced and evaluated inside the TAM model. Perceived usefulness is defined as the potential user’s assessment of the subjective probability that the usage of a given system will improve their activity, whereas perceived ease of use is related to the efforts that the user anticipates when employing a particular technology. Namahoot and Rattanawiboonsom (Citation2022) proposed a model that examined a study adopting the technology acceptance model with additional constructs (i.e. innovativeness) and the mediating role of attitude and perceived risk of using the cryptocurrency platform in Thailand. While external circumstances also influence the likelihood that a user will adopt a technology, TAM explains around 40% (Freeman, Citation2016) of the diversity in users’ technology adoption behavior. TAM2 was developed to address the weaknesses of the TAM’s explanatory power. TAM3 by Venkatesh and Bala (Burke & Leben, Citation2020) incorporated the determinants of TAM’s perceived ease of use and usage intention components for robustness, whereas TAM2 solely concentrated on the drivers of TAM’s perceived usefulness and usage intention constructs. Additionally, TAM3 revealed a comprehensive conceptual model of the predictors of user adoption of innovation technology.

Numerous theoretical frameworks have been developed based on a literature review to examine user intentions, actual behavior, and acceptance of emerging technologies. These frameworks include the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), technology acceptance model (TAM), Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), and DeLone and McLean information system success model (DL&ML). In the realm of Internet banking and mobile payment business, a limited number of studies have employed the UTAUT model to investigate Internet banking adoption (Almaiah et al., Citation2022). The primary objective of this study is to examine the hypotheses by employing the ISSM-integrated framework, with UTAUT serving as the foundation for predicting customer satisfaction projections. We extended the TAM and incorporated the updated DL&ML framework. Almaiah et al. (Citation2022) conducted an initiative aimed at advancing the utilization of digital information in higher education. They proposed an integrative methodology encompassing measuring the volume of digital information flow and instructors’ influence on TAM constructs and perceived educational experience of digital information (DIE).

After introducing the TAM3 model, the research methodology, including a summary of the survey design, data collection, and data analysis, will be discussed. Next, the survey findings are provided, consisting of a breakdown of the survey’s demographics. In addition, a reliability study and model assessment of the TAM3 model are provided to demonstrate how users are influenced to utilize legaltech in court proceedings. Finally, there is a discussion of the study limitations, practical and theoretical consequences, conclusions, and potential for future research.

2.2. Hypotheses formulation

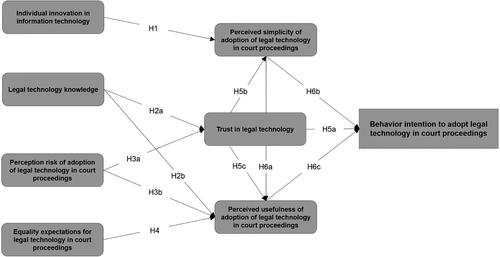

Following the assessments of the TAM3 (Venkatesh & Davis, Citation2000) and TAM2 (Venkatesh & Bala, Citation2012), we introduced external variables and linkages to the TAM. The literature is replete with a variety of TAM3 enhancements (Alarie et al., Citation2018; Moon & Kim, Citation2001; Ortega Egea & Román González, Citation2011; Tsai et al., Citation2020; Tung et al., Citation2008). However, external influences vary greatly across research disciplines (Feng et al., Citation2021). We investigated the effects of trust, risk perception, equality aspirations, legaltech insights, and individual inventiveness (the developed framework is shown in ).

Figure 1. Conceptual proposal for the study based on TAM3 of Venkatesh and Bala (Venkatesh & Bala, Citation2008).

2.2.1. Individual innovation in information and technology (IT)

We propose that the court’s adoption of IT can accelerate the diffusion of internal knowledge and encourage the integration of external knowledge. Individuals who demonstrate greater ingenuity in leveraging IT tools and technology will discover legaltech to be more user-friendly and intuitive. This hypothesis posits that an individual’s aptitude and inclination to introduce novel ideas and practices in the realm of information technology will exert a substantial and favorable influence on their opinion of the ease of utilizing legal technology (legaltech) within the framework of Vietnam’s judicial system. Individual characteristics, including innovativeness in digital technologies, may be predictive of fundamental TAM3 components, such as the behavioral acceptance of technology (Ciftci et al., Citation2021). In the scenario of adopting new legaltech, the speed of adopting creative solutions is strongly associated with expertise in regularly using multiple technologies. Additionally, it may have a forceful effect on how users perceive ease of use rather than on their orientation towards the use of advanced technology.

H1: Individual innovation in IT significantly and positively influences the perceived simplicity of legaltech.

2.2.2. Legaltech knowledge

Previous research has demonstrated the individual benefits of utilizing legaltech on both the number and quality of patents (Taherdoost, Citation2018). The process of digital transformation affects legal services, comprising a variety of elements, including legal consulting, client representation in court and out-of-court proceedings, legal documentation production, and other unclassified duties performed by applying specialized legal knowledge (Hartung et al., Citation2018). We suggest that knowledge utilization can facilitate the advancement of legaltech. We also aim to identify the cognitive dimension of legaltech trust, defined as an individual’s understanding of the current state of legaltech (Taherdoost, Citation2018). Consequently, the following hypothesis was developed:

H2a: Legaltech knowledge significantly and positively influences trust in legaltech.

H2b: Legaltech knowledge significantly and positively influences the perceived usefulness of adoption of legaltech in court proceedings.

2.2.3. Risk perception of adopting legaltech

In general, new technologies are accompanied by numerous risks, such as confidentiality, ambiguity, and unpredictability (Ballell, Citation2019; Osoba & Welser, Citation2017). These considerations are crucial in the legal sphere (Brooks et al., Citation2020; Salmerón-Manzano, Citation2021) when assessing the amplitude of harm caused by partiality or error.

Risk has been frequently added to the TAM3 in a variety of fields (Clothier et al., Citation2015; Tiwari & Tiwari, Citation2020), as risk perception can predict perceived utility (Featherman & Pavlou, Citation2003) and the inclination to directly employ the technology (Ikhsan, Citation2020). This type of TAM3 includes both trust and risk, as risk has a direct effect on trust (Clothier et al., Citation2015). According to TAM3’s hypothesis, external forces influence the intentions and behavior of utilizing advanced technologies via perceived usefulness, ease of use, and perceived utility. Consequently, the following alternative hypotheses were developed:

H3a: Risk perception of legaltech significantly and negatively influences trust in adoption of legaltech.

H3b: Risk perception of legaltech significantly and negatively influences the perceived usefulness of adoption of legaltech in court proceedings.

2.2.4. Expectations for equality regarding legaltech in court proceedings

Traditionally, challenges related to algorithmic fairness (Wachter et al., Citation2017; Xiang, Citation2021), focused on distributive justice, have received the most attention. This discussion emphasizes the equitable distribution of resources, such as in relation to discrimination issues (Xiang, Citation2021). However, procedural equality has recently received increased attention (Lee et al., Citation2019; Woodruff et al., Citation2018), as it is critical to ensure that ethical reasoning or the fairness of judgement procedures is not subsumed by the focus on outcome equality, particularly in the legal realm (Burke, Citation2020). The most powerful relationship was observed between performance expectancy and hedonic motivation. Information quality affects learning value the most since hedonic motivation is the behavioral use in the adoption of the new m-learning model in higher education (Sitar-Tăut & Mican, Citation2021). Thus, it is likely that expectations of justice have the greatest influence on the perceived utility of legaltech in court proceedings, which leads to the following hypothesis:

H4: Expectations of equality related to legaltech in court proceedings significantly and positively influence the perceived usefulness of legaltech.

2.2.5. Trust in legaltech

Trust is crucial in the initial phases of technological adoption (Ostrom et al., Citation2019). Additionally, trust in technology can be a great concern in the legal sector (Silva et al., Citation2018), often described as risk-averse, conservative, and resistant to change (Brooks et al., Citation2020). However, the assessment and analysis of the benefits and drawbacks of almost any innovation are vital for the provision of legal services. In numerous domains of study, the TAM3 is frequently associated with trust, and could thus accurately capture this aspect (Choi & Ji, Citation2015; Dirsehan & Can, Citation2020; Ejdys, Citation2018; Wu et al., Citation2011; Xu & Wang, Citation2021).

A meta-analysis was conducted to better comprehend the function with respect to computer systems (Da Xu et al., Citation2014). Using data from 128 articles, the significance value of the correlations between perceived usefulness, perceived simplicity, perceived risk, and equality expectations regarding advanced technologies were studied. Trust was strongly associated with each of the key TAM3 constructs: behavioral intention (r = 0.472), perceived effectiveness (r = 0.499), and perceived simplicity (r = 0.461). Using the following assumptions, we investigated the links involving trust and equality expectations in using technology in court proceedings, its perceived simplicity, and the usefulness of legaltech in court proceedings.

H5a: Trust in legaltech significantly and positively influences the behavioral intention to adopt legaltech in court proceedings.

H5b: Trust in legaltech significantly and positively influences the perceived simplicity of adoption of legaltech in court proceedings.

H5c: Trust in legaltech significantly and positively influences the perceived usefulness of adoption of legaltech in court proceedings.

2.2.6. Perceived usefulness and simplicity

The classic TAM postulates that several fundamental elements influence the cognitive and behavioral intention to adopt technology, including the attitude towards utilizing technology, perceived simplicity, and perceived usefulness (Davis, Citation1989). Newer versions (Venkatesh & Bala, Citation2008) and most extensions of the TAM avoid mentioning attitude towards the use of advanced technology (Alarie et al., Citation2018; Feng et al., Citation2021; Liu & Tao, Citation2022) and replace them with external variables, including individuality and normative trust, that were not included in the original TAM (Feng et al., Citation2021). According to the TAM3, perceived usefulness and simplicity are anticipated to positively influence attitudes towards employing technology (Davis, Citation1989). Additionally, the perceived simplicity of use positively influences perceived utility. By correlating the elements of the TAM and our study objectives, the following three principal hypothesized relationships were examined:

H6a: Perceived simplicity significantly and positively influences the perceived usefulness of adopting legaltech in court proceedings.

H6b: Perceived simplicity significantly and positively influences the behavioral intention to adopt legaltech in court proceedings.

H6c: Perceived usefulness significantly and positively influences the behavioral intention to adopt legaltech in court proceedings.

2.3. Moderating factors in the TAM3

This section investigates moderators, which are factors that influence the strength of the relationships across both independent and dependent variables. These include trust and the behavioral desire to employ legaltech in court proceedings.

2.3.1. Occupation

Research has demonstrated the meaning and significance of context-specific elements in determining technology acceptance (Feng et al., Citation2021); In the legal realm, court experience and belonging to the legal occupation are particularly relevant.

2.3.2. Court expertise

Judicial experience is a recognized variable that influences perceptions of the court’s trustworthiness, legitimacy, and justice (Alda et al., Citation2020). The majority of people do not comprehend how courts function or what to expect during a court session. Few people have appeared in court proceedings, and thus have based their opinions on media representations and other sources of information. Consequently, judicial experience may also be crucial for TAM3 connections. Therefore, all assumptions were examined and contrasted among even those without court proceedings expertise.

2.3.3. Age

While it may be challenging to use biological age to identify behaviors related to technology (Sitar-Tăut, Citation2021; Yang & Shih, Citation2020), age may influence attitudes about the implementation and use of legaltech in court proceedings. Age could be associated with impressions regarding courts (Petkevičiūtė-Barysienė, Citation2016) and expectations of justice (Bell et al., Citation2004). At least in Vietnam, older individuals are anticipated to have less faith in a judicial system that uses technology (Bui & Nguyen, Citation2022), owing to their status as digital immigrants (i.e. those who were raised and educated before the broad utilization of digital technologies). Thus, it is reasonable to assume that older individuals may find it more challenging to use legaltech during court proceedings. Accordingly, most assumptions were evaluated and contrasted between groups of older and younger individuals.

2.3.4. Gender

Gender is another commonly studied demographic trait within the TAM3 (Hanham et al., Citation2021; Sindermann et al., Citation2020). However, outcomes have varied widely: some research has found no effect of gender (Dutta et al., Citation2018; Hanham et al., Citation2021; Sindermann et al., Citation2020; Sitar-Tăut, Citation2021) while other studies have (Sindermann et al., Citation2020; Subawa et al., Citation2021). Owing to a paucity of data on the subject of legaltech acceptance, we investigated gender disparities across the suggested model’s routes.

3. Research method

This study utilized the quantitative research technique of surveying. Inadequacies in surveying, identity biases, differences in how respondents interpret the research questionnaire, etc. can compromise the reliability and potential significance of the findings gathered. Nonetheless, this was essential for experimentally and objectively assessing people’s perceptions for the following reasons: (1) Facts on people’s attitudes towards court proceedings technology were collected to overcome reasonable issues. (2) The statistical methods permit measuring the applicability of the acceptance and use of technology in the court context, which is helpful for identifying and forecasting people’s different intentions to utilize technology in certain other slightly elevated contexts, including health care services (Ammenwerth, Citation2019). (3) Statistically evaluating the TAM3 and validating its elements throughout diverse groups of research enabled us to gain a preliminary knowledge of the model’s practical application boundaries. (4) A systematic examination of the framework permitted the evaluation of the links between the structures, thereby enhancing our understanding of the critical elements of how individuals perceive technology in court proceedings. Thus, despite quantitative approaches not being the most effective method for collecting individuals’ impressions of court and technology, it provides evidence regarding people’s opinions and a solid foundation for research.

3.1. Research sampling

The study model was evaluated by using survey questionnaire data. The inclusion criteria were to be practitioners of law, court experience, and age. This became advantageous in survey both younger adults (18–39 years old) and older adults (40 years old or older). Based on earlier studies that demonstrated changes in TAM3 characteristics between 30 and 40 years, the age barrier was relative (Tian et al., Citation2019). Next, it was preferred for a significant portion of the sample to have a background in law, i.e. to be in the profession. The snowball technique was utilized to investigate members of the existing groups.

3.2. Questionnaires

Based on a rigorous synthesis of the literature. The questionnaire had multiple components; the first piece assessed participants’ understanding of court-related legaltech. Six statements were presented to participants about six highly sophisticated technologies, including document verification and initial categorization, a system for decision making, which indicated acceptable fines for each issue, and algorithms for resolving weak case disagreements. For instance, respondents were exposed to the following statements: ‘In certain nations, judges have access to a program that provides a detailed assessment of the case, evaluates arguments, and identifies potential outcomes’. The participants were then required to identify with their level of knowledge on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 to 5. The five levels clarify the knowledge of people from different backgrounds: ‘I know nothing about this’, ‘I have noticed something about this’, ‘I have examined these technologies more closely’, ‘I am quite knowledgeable about these technologies’, and ‘I have utilized these or similar technology’.

On a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (absolutely agree), participants’ technology acceptance constructs were examined in the second part of the survey. The use of the seven-point scale for indicating acceptance and use of technology are widespread in TAM3, and are typically superior in terms of statistical concerns, such as distribution normality. Except for the information regarding legaltech constructs and an ATT scale item, these and all other items were changed or incorporated from the prior studies (presented in ).

Table 1. Study constructs, components, and references.

The third and fourth portions examined other dimensions, including risk perception, equality expectations, trust in advanced technologies, and individual innovation, on a Likert-type scale from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (absolutely agree).

Respondents were requested to provide their personal information, including court expertise, legal occupation, age, and gender.

A limited investigation (n = 30) was undertaken to evaluate the items’ readability and dependability. The participants in the pilot study completed the questionnaire and provided feedback on the clarity, language, and content of each section. The participants included attorneys, individuals with court expertise, and individuals from all three age groups. Cronbach’s alpha, a measure of internal consistency, was more than 0.7 across all scales, indicating that the questionnaire items were reliable.

Furthermore, our study was launched at the end of 2022, the unit of analysis of this study is the people, and those people belonging to the legal sector constitute the selected population. Specifically, we have carried out research on samples corresponding to Vietnamese. To generalize and extend the results of the research, the sample has been selected in Vietnam according to the ethics committee of Posts and Telecommunications Institute of Technology, Vietnam. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. When the interviews started, the research aims were communicated to the respondents, who were also informed that their participation was completely voluntary and that they might be able to terminate at any time. Respondents received their verbal, informed consent. To secure the confidentiality of respondents, transcripts were pseudonymized.

3.3. Examination of the data collected

Partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) was employed in the study using the software SmartPLS version 3.3.3 (Hair et al., Citation2022) as PLS-SEM accommodates itself better to exploratory studies and theoretical expansions than CB-SEM (Hair, Hult, et al., Citation2019; Hamdollah & Baghaei, Citation2016). Furthermore, the PLS-SEM is renowned for possessing stronger statistical ability to identify genuinely important correlations (Henseler et al., Citation2015). In accordance with the recommendations for PLS-SEM analysis (Hair et al., Citation2022), the measuring model was assessed first, followed by the structural equation model. Finally, the multi-group analysis methods were conducted to evaluate significant group differences across groupings.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic profile

The study was performed in Vietnam. The details of the research sample, which included a final sample of 208 participants, are listed in . The age range of the participants was 17–71 years, with a mean of 22.11 years (SD = 11.0 years). The sample comprised of 41 lawyers and 33 law students (35.54% of the total). Almost half of the participants had expertise in court proceedings: 125 individuals (60.05%), including 58 lawyers, 67 law students, and nine others (4.33%).

Table 2. Respondents’ profile.

4.2. Measurement model assessment

The measurement items were examined to evaluate consistency, reliability, concurrent validity, and divergent validity (Hair et al., Citation2020). The findings indicate a reasonable degree of consistency and concurrent validity (): Cronbach’s values were predominantly between 0.70 and 0.95, the composite levels of reliability were 0.70 ≤ CR ≥ 0.95, the average extracted variance was higher than 0.5, and factor loadings were mostly higher than 0.718 (Hair, Risher, et al., Citation2019). Additionally, the Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT) indicator of construct validity did not reach 0.9 () (Hair, Risher, et al., Citation2019).

Table 3. Measurement model results of the constructs [Means (M), standard deviation (SD), factor loading, Cronbach’s Alpha (α), composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE)].

Table 4. Discriminant reliability of structures: ratio of Heterotraits to Monotraits (HTMT).

4.3. Structural equation model validation

The structural equation model was evaluated by employing the following procedures (Sarstedt et al., Citation2021): verifying all collinearity concerns, examining the model’s reliability and validity, and hypotheses testing. Importantly, the research found that none of the predictors demonstrated significant levels (see ) of collinearity (VIF < 3) (Hair, Hult, et al., Citation2019; Hair et al., Citation2020; Hair & Sarstedt, Citation2021).

Table 5. The variation inflation factor (VIF) across variables.

The determination coefficient (R2) demonstrated the quality and consistency of the conceptual framework (Hair, Hult, et al., Citation2019; Hair et al., Citation2020; Hair & Sarstedt, Citation2021). Differences in behavioral intention (R2 = 0.639), perceived usefulness (R2 = 0.525), and trust in legaltech were marginally supported by the proposed model (R2 = 0.403). The approach was less effective (R2 = 0.287) at describing the perceived ease of using judicial technologies in court proceedings.

The predictive sample technique (Q2) can be used efficiently as a predictive significance parameter (Chin, Citation2010; Fornell & Cha, Citation1994; Geisser, Citation1975; Stone, Citation1974). Using PLS and c, Q2 determines the predictive validity of a large, complex model. This method overlooks data for a given group of indicators when estimating parameters blindfolded, and then predicts the excluded portion based on the estimated parameters. Therefore, Q2 indicates how well empirically collected data can be reconstructed using the model and PLS parameters (Fornell & Cha, Citation1994). The block’s predictive measure depends on the following variables:

(1)

(1)

Where:

sum of squares of prediction error

sum of squares error using the mean for prediction

omission distance

Two differing forms of prediction techniques, cross-validated communality, and cross-validated redundant function, can be used to compute Q2. The primary result is achieved by identifying data points using the score of a latent variable, while the other is gained by predicting questionable blocks using the latent variables used for estimation. Chin (Citation2010) recommends applying the second approach to determine the predictive value of a large, sophisticated model.

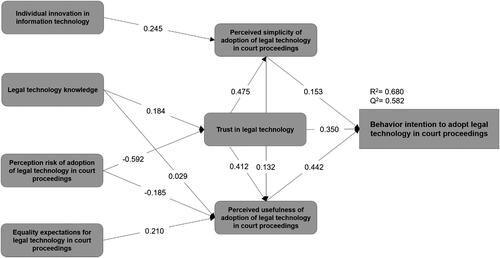

When PLS-SEM demonstrates predictive value for Q2 it employs an omission distance between 5 and 12 units. Cross-validated redundancy Q2 > 0.5 is considered a predictive model, according to the rule of thumb (Chin, Citation2010). We estimated the cross-validated redundancy Q2 of a large complex model depicted in .

Figure 2. Findings of the structural equation model evaluation.

The Stone–Geisser Q2 result was an additional important indicator of the model’s reliability (Hair, Hult, et al., Citation2019; Hair et al., Citation2022; Hair & Sarstedt, Citation2021). Blindfolding was carried out within SmartPLS based on EquationEquation 1(1)

(1) . The Q2 value of the proposed model was high for behavioral intention (Q2

0.582), moderate for trust in legaltech (Q2

0.333), and moderate for perceived usefulness of legaltech in court proceedings (Q2

0.430). Meanwhile, perceptions of the usability of legaltech in courts were lower (Q2

0.220).

The final assessment and monitoring of the study model’s quality was conducted through an examination of its forecasting performance. In accordance with Hair and Sarstedt (Citation2021), the PLSpredict function was subjected to a 10-fold cross cross-validation (Hair et al., Citation2022). The mean square root error (RMSE) for each indicator of those variables was comparable with both the PLS and the model of linear regression (LM) (Hair & Sarstedt, Citation2021). The findings indicate that the prediction accuracy of the research model was moderate. The PLS models generally had less RMSE error rates than the LM model for the majority of the variables.

Using the standard path coefficient (β) and t-statistics, this research examined the relationship between the independent and dependent variables (Hair et al., Citation2022). To measure the effectiveness of the coefficient of determination, 10,000 samples were used for bootstrapping. and illustrate the outcomes of the testing hypotheses.

Table 6. Findings from testing the hypothesis.

The first hypothesis involving the TAM3 relationships—that individual innovation in IT has a beneficial impact on the perceived usability of legaltech in court proceedings—was accepted (H1: β = 0.245; p = 0.001). Knowledge about legaltech influenced trust in legal technologies (H2a: β = 0.184; p = 0.000) and perceived usefulness (H2b: β = 0.029; p = 0.019). Additionally, the risk perception of legaltech in court proceedings had a substantial negative impact on perceived usefulness (H3b: β = 0.185; p = 0.003) and trust in legaltech (H3a: β = 0.292; p = 0.000). Furthermore, as anticipated, the expectation of equality for legaltech had a substantial positive impact on the perception of the utility of legaltech in court proceedings (H4: β = 0.210; p = 0.000). Subsequently, all three hypotheses about trust in legaltech were satisfied, indicating that trust strongly influenced all major TAM3 variables in a positive direction (H5a: β = 0.350; p = 0.000; H5b: β = 0.412; p = 0.000; H5c: β = 0.475; p = 0.000). Similarly, both hypotheses about perceived simplicity had a substantial positive impact with regard to perceived usefulness and behavioral intention, respectively (H6b: β = 0.153; p = 0.001; H6a: β = 0.132; p = 0.003). Finally, perceived usefulness significantly and positively influenced the behavioral intention to adopt legaltech in court proceedings (H6c: β = 0.442; p = 0.000).

The SmartPLS structural model’s findings are reported in . The coefficient of determination (R2) is undesirable when it is <0.19, poor if it is between 0.19 and 0.33, reasonable when it is between 0.33 and 0.67, and outstanding when it is over 0.67 (Tenenhaus et al., Citation2005). Each element exerts a moderate amount of impact. The respective measurements for PEU, PES, BEI, TRT, LTK, PER, EQE, and INI are around 0.866, 0.831, 0.790, 0.808, 0.732, 0.840, 0.791, and 0.850, respectively. In addition, the standardised root of the square residual (SRMR) must not exceed 0.08 to be considered a good model fit (Hair, Hult, et al., Citation2019; Hair, Risher, et al., Citation2019). This provided a reasonable result of 0.061 during evaluation.

4.4. Multiple-group comparisons

The objective of the multigroup assessment was to determine the impact of age, gender, legal occupation, and court experience. Incomplete samples were eliminated from the analysis, and every subset consistently exceeded the sample size (Hair, Risher, et al., Citation2019). The approach coefficients were compared among the groups, and cross-tabulation and comparison of group means were conducted.

4.4.1. Legal occupations

The multi-group approach did not identify any statistically significant distinctions across research model approaches. In addition, the suggested models were capable of explaining the intentions and behavior to adopt legaltech and the perceived effectiveness of the technology in court proceedings comparably for legal (R2 = 0.683) and other occupations (R2 = 0.665). However, this was less appropriate for explaining the perceived usefulness and ease of access for the legal occupations (R2 = 0.207) than for the other professions (R2 = 0.378). Surprisingly, the study identifies legal occupations’ trust in legaltech to be greater (R2 = 0.546) than for those pursuing other professions’ (R2 = 0.392).

4.4.2. Court expertise

The trust in legaltech (TRT) had a greater impact on the behavioral intention for using legaltech (BEI) in court proceedings among those without court experience (β = 0.492, p < 0.001) than among those with court experience (β = 0.259, p < 0.001). Ultimately, the suggested model described the perceived utility of legal technologies as much higher for individuals without court experience (R2 = 0.652) than for people with court experience (R2 = 0.483). Remarkably, the perceived ease of use (PES) had no influence on the behavioral intention to utilize technology in court proceedings (BEI) among groups without court expertise (β = −0.036, p = 0.612). The impact was found to be greatest in the group with court expertise (β = 0.268, p < 0.001).

4.4.3. Age

The findings of the multigroup examination by age revealed that the impact was insignificant across all investigated models and was most evident in the cluster of 19–40-year-olds. Knowledge regarding advanced legal technology had a minor but significant positive impact on the perceived usefulness of advanced legal technology in court proceedings (β = 0.092, p = 0.047); however, it remained insignificant among the older age group (>41 years old) (β = −0.058, p = 0.283). In addition, the assessment demonstrates that the perception of perceived ease of use (R2 = 0.460) and the usefulness of legaltech (R2 = 0.675) were more significant for older individuals than younger ones (PES: R2 = 0.234, PEU: R2 = 0.490).

4.4.4. Gender

Finally, gender impacts were also examined. The path coefficient found no statistically significant differences between men and women. However, men’s intentions to employ legaltech were better explained by the suggested model (R2 = 0.752) compared to women’s (R2 = 0.589).

4.5. Correlation of occupation and court expertise

The examination of the mean differences motivated the investigation of the observed association. Two-way statistical analysis of variance (two-way ANOVA) was conducted to examine the interrelations of occupation and court expertise. The relationship between trust in legaltech and behavior intent on employing legaltech in court proceedings was considerable. Regardless of the fact that both occupation and court experience affected legal knowledge about the technology, no correlation interactions were observed.

Accordingly, the result demonstrates that both lawyers and non-attorneys with court expertise have comparable levels of trust in legal technology. However, when an individual lacked court proceedings expertise, their occupation became significant; for illustration, lawyers without court proceedings experience had less trust in legaltech than other lawyers. A comparable trend was found for individuals with neither court proceedings expertise nor legal occupation; this was strongly linked to the weakest desire to use legaltech in court proceedings. However, lawyers with court proceedings expertise were more likely to adopt legaltech in court proceedings. Significantly, most of the 24 applicants without court proceedings expertise were university students (21 students).

5. Discussion and implications

This study contributes significantly to the body of knowledge on legaltech acceptability, although it has several limitations. An additional contextual variable introduced into the model is legaltech expertise. The cognitive aspect of knowledge is absent in many studies of technology acceptance. TAM3 could not predict the role of technology-specific knowledge. Consequently, the concept of introductory knowledge is based on the theory of innovation diffusion (Dearing & Cox, Citation2018; Rogers, Citation2010). People typically lack theoretical and regulatory knowledge of how courts operate and how to evaluate their performance, making the knowledge component arguably crucial in the legal sector. As a result, it was expected that people would lack expertise in the legal technological field. This investigation confirmed that people did not have much expertise in the legal technological field. One of the restrictions is related to the sample size. Specifically, this study utilized a diverse subsample of attorneys, including law school students. Analyzing the perceptions of legal understudies as a systems approach can further the results of judgment in a short period of time. However, further research with more focused datasets would substantially assist future research on this topic.

5.1. Theoretical implications

TAM3 considers the particularities and contextual elements of each field. In this study, we added numerous legaltech-relevant constructs to the TAM3. First, trust in legaltech was selected because confidence in technology is a key and well-studied component in the context of technology adoption (Wu et al., Citation2011). In particular, trust in a lawful technology development dimension does not always define the form or other attributes of legaltech, and participants of the study were exposed to several types of more complicated advanced legal technology, including a decision aid system for judges and a file mechanization tool that categorizes records based on whether they provide a legitimate foundation. Trust in legaltech increased the favorable perception of its use in court proceedings, its utility, and its ease of use. Surprisingly, trust was observed to be crucial in determining the perceived usefulness and perceived ease of employing legaltech in court proceedings, potentially because of the perception that courts are extremely complex institutions. In turn, the understanding of legaltech and the perception of risk influences trust.

Individuals almost certainly have a limited understanding of legaltech. This study examines the general risk associated with the employment of legal technology in court proceedings. The perceived risk had a detrimental impact on the perceived trustworthiness and effectiveness of legaltech. These outcomes mirror the findings of technological adoption studies conducted in other disciplines (Bui & Nguyen, Citation2022; Wang et al., Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2022). Given the magnitude of the effect of risk on trust, legaltech’s risk perception appears to be of great importance to individuals. Notably, several studies have examined the direct effect of perceived risk on behavioral intent to utilize technology (Jeon et al., Citation2020; Tiwari & Tiwari, Citation2020). Therefore, defining the impact of a perceived threat on people’s intent to promote advanced technology used in court might aid in the comprehension and connectivity of people’s perceptions of legaltech. While this study did not focus on specific types of risk, such as finance or data protection threats (private information was almost the sole aspect discussed) (Tiwari & Tiwari, Citation2020), particular aspects of risk can be investigated in a more in-depth study, in which participants are provided with additional information regarding the use of legaltech in courts.

The legal framework (Legg, Citation2021) predicted expectations of justice in this study. Furthermore, the respondents were requested to assess how much they would perceive the ethical implications, speech, and other characteristics of judicial proceedings that would use legaltech. Individuals have high expectations for the equality of judicial proceedings that utilize legaltech. Expectations of equality have a direct impact on the perceived utility of legaltech in court proceedings. The outcomes may suggest that users have extremely high expectations for automation systems and expect the court to resolve any disputes that arise. The relationship between equality expectations for court processes, including legaltech, and the perceived benefits of these technologies highlights the necessity of investigating the elements of the performance expectancy of legaltech.

Due to the traditional nature of the legal field, this study’s model was expanded to include individual innovation in IT. Those within legal professional groups were found to be equally inventive as those with other occupations. Individual innovation in computer technology has a positive effect on the perceptions of legaltech’s usability in court proceedings. Therefore, the more imaginative the population, the simpler it will be for them to apply legaltech in court proceedings. These results are comparable to those of other disciplines (Şahin et al., Citation2022).

Inside this research, the majority of participants from the legal occupation lacking court proceedings experience were college students; however, this may not suggest that they have the lowest trust in the use of legaltech in court since they are young. Currently, few universities teach legaltech (Janoski-Haehlen, Citation2019), and academics, and occasionally even legaltech researchers, may be more or less tolerant of legaltech. Occupation, court experience, age, and gender moderate numerous correlations within the analyzed model. Most significantly, professional and court experiences influence both trust and behavioral intentions to encourage the use of legaltech in court proceedings. Surprisingly, lawyers without court proceedings experience had the least confidence in legaltech and were the least supportive of its usage in court. Likewise, attorneys with court proceedings experience were most receptive to the use of legaltech in court proceedings. One possible reason for these disparities in the perception of legaltech is that lawyers had a greater knowledge of legaltech than other participants in our research. Therefore, it would be intriguing to investigate how legal expertise and court experience shape the adaptation of legaltech.

Age and gender may be other considerations for legaltech acceptance. Knowledge of legaltech had little effect on its perceived applicability among younger individuals and no effect among older individuals. In general, these results show that the understanding of legaltech may influence the perspectives of younger individuals more than that of older individuals. As human conceptions of artificial intelligence may vary with age, further research should be performed to discuss age disparities in perceptions of legaltech (Ballell, Citation2019; Lee & Rich, Citation2021).

5.2. Managerial implications

The findings of this research demonstrate that culture may account for some of the variance in attitudes regarding legaltech in court. For instance, support for legaltech may depend on confidence in the judicial system, in addition to confidence in legaltech itself. However, mistrust of the court may also arise because of notable cases and occurrences, including the emergence of a fraud detection system in Vietnam. Since technological advancement has not been uniform across nations, the varying automation levels that have previously been attained in courts may influence the behavioral intent to employ legaltech in courts.

The findings of this research are also useful for applying information on practical judicial decision-making before and after the installation of a particular instrument that could be of great use to the proposed model. The combination of jurimetrics and people’s opinions on the tool’s many qualities may provide the finest insights into the tool’s effectiveness. Additionally, the data may alter the opinions and perceptions of individuals. Additional research is required to address these difficulties.

The expectations of equality for legaltech constitute the discovery of novel dimensions of attitudes toward technology in court proceedings. Given that justice is the primary objective of court activity, equality preconceptions are directly linked to the perceived utility of legaltech in court proceedings.

Additionally, our research showed that those from legal occupations have lower expectations of equality than the general population. As a result of widespread cynicism towards legaltech, expectations of equality may be reduced. Alternatively, attorneys may believe that judicial proceedings can become less equitable and may not believe that legaltech significantly increases their equality. Lawyers are often involved in investigations of public opinion regarding judges; therefore, examining the perspectives of both the public and lawyers could enhance our understanding of court equality.

Furthermore, performance expectancy of use had little impact on the behavioral intent to promote legaltech in court among non-lawyers. The absence of a correlation between perceived ease of use and behavioral intention indicates that additional research on the perceived usefulness and ease of use of legaltech is required. It is possible to hypothesize that people without court proceedings expertise are not concerned with the use of legaltech in this domain. Accessibility of use predicts behavioral intent to use legaltech among individuals with judicial expertise. Accordingly, it is beneficial to consider the court experience.

Interestingly, the studied model is better adapted to describe intent to support the legalization of technology in court among men than among women. Gender was evenly distributed across all sample groups (field of work, judicial expertise, and age), although there were more women than men in the sample. As a result, no correlation was found between masculinity and any other features of the sample. Therefore, in this investigation, women viewed technology as more beneficial than men did. Moreover, there were no further changes in the groups’ opinions based on gender.

Furthermore, legaltech knowledge influences confidence in these technologies. In particular, awareness of existing legaltech increases confidence. Exceptionally, for a sample group of 18- to 39-year-olds, experience did not influence the perception of the benefits of legaltech in court proceedings throughout this research (the impact was particularly weak). The absence of a substantial correlation between understanding and perceived utility suggests that all perceptions of the usability of legaltech in court proceedings may have originated from causes other than information about the technologies available. For instance, understanding how courts operate in general, trust in courts, and expectations of equality in court processes may have a greater influence on the perception of the usefulness of legaltech than on knowledge about current legaltech.

6. Limitations and future direction research

6.1. Limitation

There exist several limitations that require thoughtful investigation when interpreting the results of the study. The study’s sample size was constrained to a particular cohort of judges and court personnel in Vietnam, perhaps restricting the applicability of the results to different settings or demographics. The research was dependent on data obtained through self-reporting, a method that is susceptible to response biases and may not fully represent the genuine opinions and actions of the participants. Furthermore, the research primarily concentrated on the acceptance of legal technology, neglecting to take into account other significant variables that may impact its adoption. Finally, it should be noted that the cross-sectional character of the study design imposes constraints on the capacity to demonstrate causal links between variables. The aforementioned constraints indicate that additional research is important to acquire a thorough comprehension of the acceptability of legal technology inside the courts of Vietnam.

6.2. Future direction research

Examining the factors that impact the perceptions and attitudes of judges and lawyers toward legal technology could yield significant insights. This may entail an examination of many human attributes, including but not limited to age, gender, and experience, as well as an analysis of the impact of organizational, cultural, and societal issues. Furthermore, the examination of comparative research encompassing other countries or legal systems has the potential to illuminate the contextual discrepancies in the acceptability of legal technology. This study aims to ascertain optimal strategies and policy recommendations for enhancing the usage of legal technology in Vietnam. Finally, an examination of the influence of legal technology on the efficiency, efficacy, and equity of court proceedings could yield empirical data regarding the potential advantages and obstacles linked to its adoption.

7. Conclusion

This study sought to understand how individuals feel about the use of legaltech in court proceedings and identify the most crucial predictor of people’s preparedness to accept modern technologies given the possible lack of understanding. Furthermore, it analyzed how differences in individuality affected perceptions of artificial intelligence and other court proceedings technologies. Thus, this research contributes to the growing body of literature on people’s perspectives and attitudes towards legaltech by providing statistics on people’s motivations for using legaltech in court proceedings.

The perceived value of legaltech is the most important element in predicting court support for legaltech. In turn, the perceived usefulness may be influenced by trust in legaltech, perceived risk, and knowledge about legaltech. Similar to other individual innovations in other contexts, including health and education, the results indicate that individuals are interested in utility, usability, and other difficulties. Additionally, expectations of justice are also a major consideration; for instance, larger aspirations may enhance preconceptions of helpfulness. Importantly, getting deeper insights, data, and understanding about the efficiency of technology might shift preconceptions. Despite this, persons of varying degrees of awareness may nevertheless keep divergent views, depending on additional factors. In addition, the multigroup analyzes undertaken in this study have led us to believe that the acceptance and use of the technology models can be utilized to analyze the technology acceptance of both lawyers and the general community. This gives direction for the design and deployment of the technology.

Given the rapid advancement of legaltech, the author believes this investigation represents the first of several approaches to obtain more insights into its acceptability in court proceedings. A systematic review of people’s opinions of court proceedings technology may uncover more particular concerns. Clearly, an investigation into where justice and several other legal occupations require new technologies is long overdue. While additional research is required to better comprehend the varying perspectives of various social groups about legaltech in court proceedings, the current study indicates that individual inventiveness, legal industry, court proceedings, expertise, age, and even gender may influence the judgments of individuals. These findings may have diverse ramifications for the advancement and application of technology.

Ethical approval

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of Posts and Telecommunications Institute of Technology, Vietnam. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

When the interviews started, the research aims were communicated to the respondents, who were also informed that their participation was completely voluntary and that they might be able to terminate at any time. Respondents received their verbal, informed consent. To secure the confidentiality of respondents, transcripts were pseudonymized.

Author contributions

N.N.A.D., V.P.N., and B.K.H. performed the measurements. N.N.A.D., V.P.N., and B.K.H were involved in planning and supervised the work. N.N.A.D., V.P.N., and B.K.H. processed the experimental data, performed the analysis, drafted the manuscript, and designed the figures. N.N.A.D., V.P.N., and B.K.H. performed the study calculations. N.N.A.D., V.P.N., and B.K.H. aided in interpreting the results and worked on the manuscript. All authors have read and final approval of the version to be published; Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Acknowledgements

We are also grateful for the insightful responses, experiences, ideas, and opinions offered by the anonymous experts in Vietnam. The generosity and expertise of one and all have improved this study in innumerable ways and saved it from many errors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data used in this study can be obtained from V. P. Nguyen.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ngoc Anh Dao Nguyen

Ngoc Anh Dao Nguyen is a lecturer at Ho Chi Minh University of Banking, teaching courses in Composition, Copyright, and Intellectual Property Law. She received the 2020 award for Outstanding Classroom Instructor from Ho Chi Minh University of Banking for teaching undergraduate economics and law courses. Her published works include several books on copyright and intellectual property law.

Van Phuoc Nguyen

Van Phuoc Nguyen is a lecturer at the Posts and Telecommunications Institute of Technology, teaching courses in E-Business Management, International Business. Nguyen’s recent publications include articles on the challenges of artificial intelligence.

Kim Hieu Bui

Kim Hieu Bui is the Dean of the Faculty of Law at Ho Chi Minh City University of Foreign Languages and Information Technology, teaching courses in Economics and Law. His research includes articles on Artificial Intelligence, Fintech, and ICT legal and regulation research.

References

- Abramovsky, L., & Griffith, R. (2006). Outsourcing and offshoring of business services: How important is ICT? Journal of the European Economic Association, 4(2–3), 1–23. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40005125 https://doi.org/10.1162/jeea.2006.4.2-3.594

- Alarie, B., Niblett, A., & Yoon, A. H. (2018). How artificial intelligence will affect the practice of law. University of Toronto Law Journal, 68(supplement 1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3138/utlj.2017-0052

- Alda, E., Bennett, R., Marion, N., Morabito, M., & Baxter, S. (2020). Antecedents of perceived fairness in criminal courts: A comparative analysis. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 44(3), 201–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924036.2019.1615521

- Almaiah, M., Al-Otaibi, S., Lutfi, A., Almomani, O., Awajan, A., Alsaaidah, A., Alrawad, M., & Awad, A. (2022). Employing the TAM model to investigate the readiness of M-learning system usage using SEM technique. Electronics, 11(8), 1259. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11081259

- Ammenwerth, E. (2019). Technology acceptance models in health informatics: TAM and UTAUT. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 263, 64–71. https://doi.org/10.3233/SHTI190111

- Ballell, T. R. (2019). Legal challenges of artificial intelligence: Modelling the disruptive features of emerging technologies and assessing their possible legal impact. Uniform Law Review, 24(2), 302–314. https://doi.org/10.1093/ulr/unz018

- Bell, B. S., Ryan, A. M., & Wiechmann, D. (2004). Justice expectations and applicant perceptions. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 12(1–2), 24–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0965-075X.2004.00261.x

- Bourke, J., Roper, S., & Love, J. H. (2020). Innovation in legal services: The practices that influence ideation and codification activities. Journal of Business Research, 109, 132–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.057

- Brehm, K., Hirabayashi, M., Langevin, C., Munozcano, B. R., Sekizawa, K., & Zhu, J. (2020). The future of AI in the Brazilian judicial system (pp. 1–20). Retrieved from https://itsrio.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/SIPA-Capstone-The-Future-of-AI-in-the-Brazilian-Judicial-System-1.pdf

- Brooks, C., Gherhes, C., & Vorley, T. (2020). Artificial intelligence in the legal sector: Pressures and challenges of transformation. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 13(1), 135–152. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsz026

- Bui, T. H., & Nguyen, V. P. (2022). The impact of artificial intelligence and digital economy on Vietnam’s legal system. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law, 9(8), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-022-09927-0

- Burke, K. S. (2020). Procedural fairness can guide court leaders. Court Review, 56(2), 76–78.

- Burke, K. S., & Leben, S. (2020). Procedural fairness in a pandemic: It’s still critical to public trust. Drake Law Review, 68(4), 685–706.

- Chin, W. W. (2010). How to write up and report PLS analyses. In V. Esposito Vinzi, W. Chin, J. Henseler, & H. Wang (Eds.), Handbook of partial least squares. Springer handbooks of computational statistics. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-32827-8_29

- Choi, J. K., & Ji, Y. G. (2015). Investigating the importance of trust on adopting an autonomous vehicle. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 31(10), 692–702. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2015.1070549

- Ciftci, O., Berezina, K., & Kang, M. (2021). Effect of personal innovativeness on technology adoption in hospitality and tourism: Meta-analysis. In J. L. Stienmetz, W. Wörndl, & C. Koo (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism 2021 (pp. 162–174). Springer International Publishing.

- Clothier, R. A., Greer, D. A., Greer, D. G., & Mehta, A. M. (2015). Risk perception and the public acceptance of drones. Risk Analysis, 35(6), 1167–1183. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12330

- Collins, G. S., & Moons, K. G. M. (2019). Reporting of artificial intelligence prediction models. Lancet, 393(10181), 1577–1579. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30037-6

- Colquitt, J. A. (2001). On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 386–400. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.386

- Corrales, M., Fenwick, M., & Haapio, H. (2019). Legal tech, smart contracts and blockchain. Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6086-2

- Da Xu, L. D., He, W., & Li, S. (2014). Internet of things in industries: A survey. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, 10(4), 2233–2243. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2014.2300753

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–339. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

- Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1989). User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science, 35(8), 982–1003. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.35.8.982

- Dearing, J. W., & Cox, J. G. (2018). Diffusion of innovations theory, principles, and practice. Health Affairs, 37(2), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1104

- Deeks, A. (2019). The judicial demand for explainable artificial intelligence. Columbia Law Review, 119(7), 1829–1850. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/26810851

- Dirsehan, T., & Can, C. (2020). Examination of trust and sustainability concerns in autonomous vehicle adoption. Technology in Society, 63, 101361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101361

- Dubois, C. (2021). How do lawyers engineer and develop legaltech projects? A story of opportunities, platforms, creative rationalities, and strategies. Law, Technology and Humans, 3(1), 68–81. https://doi.org/10.5204/lthj.v3i1.1558

- Dutta, B., Peng, M.-H., & Sun, S.-L. (2018). Modeling the adoption of personal health record (PHR) among individual: The effect of health-care technology self-efficacy and gender concern. The Libyan Journal of Medicine, 13(1), 1500349. https://doi.org/10.1080/19932820.2018.1500349

- Dwivedi, Y. K., Ismagilova, E., Hughes, D. L., Carlson, J., Filieri, R., Jacobson, J., Jain, V., Karjaluoto, H., Kefi, H., Krishen, A. S., Kumar, V., Rahman, M. M., Raman, R., Rauschnabel, P. A., Rowley, J., Salo, J., Tran, G. A., & Wang, Y. (2021). Setting the future of digital and social media marketing research: Perspectives and research propositions. International Journal of Information Management, 59, 102168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102168

- Ejdys, J. (2018). Building technology trust in ICT application at a university. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 13(5), 980–997. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJoEM-07-2017-0234

- Engel, C., & Grgić-Hlača, N. (2021). Machine advice with a warning about machine limitations: Experimentally testing the solution mandated by the Wisconsin Supreme Court. Journal of Legal Analysis, 13(1), 284–340. https://doi.org/10.1093/jla/laab001

- Featherman, M. S., & Pavlou, P. A. (2003). Predicting e-services adoption: A perceived risk facets perspective. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 59(4), 451–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1071-5819(03)00111-3

- Feng, G. C., Su, X., Lin, Z., He, Y., Luo, N., & Zhang, Y. (2021). Determinants of technology acceptance: Two model-based meta-analytic reviews. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 98(1), 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699020952400

- Fornell, C., & Cha, J. (1994). Partial least squares. In R. P. Bagozzi (Ed.), Advanced methods of marketing research (pp. 52–78). Blackwell.

- Freeman, K. (2016). Algorithmic injustice: How the Wisconsin Supreme Court failed to protect due process rights in State v. Loomis. North Carolina Journal of Law & Technology, 18, 75–106.

- Fu, J., & Mishra, M. (2022). Fintech in the time of COVID − 19: Technological adoption during crises. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 50, 100945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2021.100945

- Geisser, S. (1975). The predictive sample reuse method with applications. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 70(350), 320–328. https://doi.org/10.2307/2285815

- Gunasinghe, A., Hamid, J. A., Khatibi, A., & Azam, S. M. F. (2019). The adequacy of UTAUT-3 in interpreting academician’s adoption to e-learning in higher education environments. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 17(1), 86–106. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITSE-05-2019-0020

- Hair, J. F.Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2019). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

- Hair, J. F., Howard, M. C., & Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069

- Hair, J. F., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). Data, measurement, and causal inferences in machine learning: Opportunities and challenges for marketing. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 29(1), 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.2020.1860683

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2022). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hamdollah, R., & Baghaei, P. (2016). Partial least squares structural equation modeling with R. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation, 21(1), 1–16.

- Hameed, I., Mubarik, M. S., Khan, K., & Waris, I. (2022). Can your smartphone make you a tourist? Mine does: Understanding the consumer’s adoption mechanism for mobile payment system. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2022, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4904686

- Hanham, J., Lee, C. B., & Teo, T. (2021). The influence of technology acceptance, academic self-efficacy, and gender on academic achievement through online tutoring. Computers & Education, 172, 104252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104252

- Hartung, M., Bues, M. M., & Halbleib, G. (2018). Legal tech: A practitioner’s guide. CH Beck.

- Hartung, M., Bues, M.-M., & Halbleib, G. (2017). Legal tech. Beck/Hart.

- Hasani, I., Chroqui, R., Okar, C., Talea, M., & Ouiddad, A. (2017). Literature review: All about IDT and TAM. Berrechid, Morocco: National School of applied sciences.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Ikhsan, K. (2020). Technology acceptance model, social influence and perceived risk in using mobile applications: Empirical evidence in online transportation in Indonesia. Jurnal Dinamika Manajemen, 11(2), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.15294/jdm.v11i2.23309

- Intellectual Property Office of Vietnam (2020). Viet Nam’s intellectual property strategy until 2030: Driving force for development of intellectual property assets. Retrieved from https://www.most.gov.vn/en/news/753/viet-nam's-intellectual-property-strategy-until-2030–driving-force-for-development-of-intellectual-property-assets.aspx