Abstract

Organizations disclose environmental, social, and governance (ESG) information for various reasons, including mandatory reporting regulations. However, for environmentally sensitive corporations, ESG disclosure is not only a regulatory obligation. It also has the potential to promote corporate reputation. This study aims to uncover the motivating factors behind ESG disclosures in an emerging economy. The research methodology employed in the study includes (i) systematically reviewing literature following the PRISMA protocol to identify ESG disclosure motives, (ii) integrating fuzzy set theory with interpretive structural modelling (FISM) for developing a structural hierarchical model to understand the interactions between the motives, (iii) applying a fuzzy Matrice d’impacts croisés multiplication appliquée á un classment (Fuzzy MICMAC) approach to categorize the motives. The FISM model shows that organizations primarily disclose ESG information in response to regulatory and stakeholders’ pressures. The results further highlight the role of corporate ‘greenwashing’ behaviour and ethical considerations in ESG. The findings recommend that feasible regulations are crucial in improving ESG reporting quantity and quality. This research is one of the very few examining the motives behind ESG disclosures and a ‘stepping-stone’ to implementing mandatory ESG disclosure regulations. Understanding ESG disclosure motives will enable policymakers to draft policies that promote greater sustainability commitment.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

Sustainable development, which attempts to create peaceful cohabitation between humans and the environment, is based on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues (Wan et al., Citation2023). ESG issues and how organizations respond to them are currently top concerns among stakeholders. The concept of ESG, as a manifestation of sustainable development, integrates social justice, environmental preservation, and economic growth. It has evolved into a crucial metric for determining an organization’s overall performance as well as a significant driver for sustainable finance. ESG offers a feasible approach to the challenges posed by various phenomena, such as climate change, COVID-19, and the current economic downturn. Furthermore, social responsibility issues like financial fraud and environmental pollution have been growing significantly in recent years (Lee & Lee, Citation2022). ESG has evolved into a new competitive strategy that affects business decision-making (Galbreath, Citation2013) and aids organizations in maintaining a good corporate reputation (Flammer & Bansal, Citation2017). As a result, ESG is gaining momentum in global academic, practical, and policy discussions and is now considered a major social issue (Wan et al., Citation2023).

Sustainability issues and policies have slowly attracted more and more attention. ESG disclosure is said to have its roots in the broader movement towards corporate sustainability. It emerged in response to growing concerns relating to the effects of business practices on the environment, society, and corporate governance practices. The reliance on non-financial disclosures by stakeholders to recognize sustainable companies has led to an increasing supply of ESG reports. Investors now anticipate ESG information before making investment decisions in businesses. As such, ESG information requirements have gained vast attention globally. The goal of requiring the disclosure of information related to ESG is to offer recommendations on achieving environmental and sustainable goals. Similarly, it could promote sustainability by highlighting ESG activities and encouraging companies to improve them since no company would want to disclose having a negative impact on society.

ESG emerged as a sensitive issue attracting the attention of a large audience that could not be ignored (Zaccone & Pedrini, Citation2020). With the recent rise in ESG reporting awareness, businesses are now making commitments regarding ESG problems. This led to intense pressure on organizations to include ESG information in their annual reports. Unfortunately, organizations have ‘not yet had a marked impact on pressing social and environmental issues’ (Aragòn-Correa et al., Citation2020). Further, Di Tullio et al. (Citation2020) reveal that many firms publish ESG reports using non-accounting words and data, while others entirely ignore the mandatory disclosure rules. These failures may be attributable to the limited understanding of the ESG disclosure motives by these companies. Although statistics indicate a considerable shift towards ESG integration, little is known about the ESG disclosure motives (Zaccone & Pedrini, Citation2020). For instance, during the past five years, N100Footnote1 corporations disclosing environmental issues as a risk to their business increased from 28% in 2017 to 46% in 2022 (KPMG, Citation2022). Since 2017, firms have recorded a noticeable improvement in disclosing information about environmental issues, including climate change. However, ‘its growth does not reflect the urgency spelled out by the IPCCFootnote2’s ‘Code Red’ report in 2021, which called for urgent action to mitigate climate change’ (KPMG, Citation2022, p. 63).

Remarkably, extant literature has explored the practical issues revolving around ESG as a whole. Recent studies have identified organizational motives for disclosing ESG information in a fragmented and limited approach. Research has examined the drivers of ESG activities (e.g. Barros et al., Citation2022; Bizoumi et al., Citation2019) as well as its impacts both in developed and developing economies contexts (e.g. Larcker et al., Citation2022; Sassen et al., Citation2016). Few studies have explored the motives for integrating various sustainability strategies into practice (Vo et al., Citation2015). However, most of these motives are either discussed as a subset of a study with a distinctive focus (e.g. Arif et al., Citation2021; Broadstock et al., Citation2019; Fatemi et al., Citation2018) or on motives for disclosing a specific factor among the ESG ‘soup’, such as corporate social responsibility (CSR) (e.g. Dixit et al., Citation2022) or corporate environmental (e.g. Bui et al., Citation2020; Zhang et al., Citation2021) or corporate governance (e.g. Ronoowah & Seetanah, Citation2023). These studies, therefore, are not exhaustively focusing on ESG disclosure motives.

Notably, corporations disclose their ESG activities for various motives. It is unclear exactly what role and influence each of these motives plays. Given the complexity of ESG information, it is highly desirable for policymakers and researchers to have an extensive record of the disclosure motives and how these motives interact. Understanding ESG disclosure motives will not only help organizations have a better ESG performance leading to an improved impact on its stakeholders. It can also facilitate policymakers to draft ESG policies, which encourage and promote greater ESG commitment by organizations.

Although the literature provides empirical evidence of ESG disclosure motives, it is reasonable to consider that these motives may influence each other due to their ambiguous boundaries. However, the evidence of ESG disclosure motives is limited (Arif et al., Citation2021; Fatemi et al., Citation2018) from the perspectives comprehensively documenting relevant motives, or understanding the nature of the interactions among the motives. Thus, a thorough evaluation of the literature reveals a lack of evidence with a framework that considers all potential ESG disclosure motives to critically assess them. The existing research merely identifies the motives for ESG disclosure without delving into their interrelationships. This might lead to a more thorough examination of the complexities involved and a clearer understanding of the factors. A limited understanding of the relationships among the motives for ESG disclosure may give a limited perspective of its basic structure. Hence, Hopwood (Citation2009) suggested that it is probable that corporate ESG disclosure may be characterized by many distinct motives and recommended future research into the complexities of ‘corporate disclosure decision-making and for a deeper understanding of the(ir) interactions’. (2009, pp. 437–438). Therefore, understanding the interrelationships pattern is significant in gaining relevant insights for policymaking that would effectively and thoroughly address ESG issues. As Larcker et al. (Citation2022) emphasized, decisions regarding ESG would improve if they were based on empirical evidence and theoretical research in the domain. Hence, this study attempts to explore the motives of ESG disclosure practices in an environmentally sensitive industry. In line with this, the study aims to address the following research objectives;

To identify the relevant motives behind corporate ESG disclosures in an environmentally sensitive industry.

To establish the significant relationships between the motives to understand their importance in policy design.

To group these motives into subcategories that may assist in decision-making.

To address the aforementioned research objectives, the present study compiled an extensive list of motives via a literature review. FISM was employed to explain the contextual relations between these motives because of their subjectivity and the idea that the evaluation of their interrelationships relies on the experts’ opinions. FISM and its accompanying graphical representation, the Fuzzy MICMAC, are prominent techniques for describing contextual relationships among aspects indicating causes or driving factors of a certain issue.

The remainder of the paper is organized into the following sections. Section 2 outlines the motivations for ESG disclosure and examines the relationships in light of recent literature. Section 3 provides background information on the methodology, and Section 4 presents the modeling of ESG disclosure motives. Section 5 explains the findings and offers policy recommendations. Section 6 concludes and discusses future research directions.

2. Background of the study

2.1. ESG disclosures

The communication of firms’ sustainability objectives, more precisely, on its ‘environmental’, ‘social’, and ‘governance’ objectives and its progress towards attaining them, are regarded as ESG disclosure. The information disclosed enables stakeholders to evaluate organisations’ commitments toward sustainability, which will consequently influence their decisions in rewarding firms with higher ESG initiatives (Sarti et al., Citation2018). Organizations may also use ESG disclosure to manage public perceptions by reporting modifications in their policies regarding ESG matters (Fatemi et al., Citation2018).

The theoretical foundations of ESG disclosure have been studied in past works (Alsayegh et al., Citation2020). These theories have explained the essence of disclosing ESG information by organisations. For instance, researchers explain ESG information disclosure using the stakeholder perspective (Huang, Citation2021; Jasni et al., Citation2019). Also, the existing belief that sustainability disclosure adds legitimacy to companies’ operations has been used to build ESG disclosure literature (Arif et al., Citation2021; Wang et al., Citation2020). However, there is no consensus on a single theory explaining corporations’ motives for ESG disclosure (Murphy & McGrath, Citation2013). Hopwood argues that ‘it is clear that a variety of motives may well be implicated in the production of environmental and sustainability reports’ (Hopwood, Citation2009, p. 438). Hence, future studies are encouraged to broaden ESG disclosure analysis in light of different theoretical perspectives (Taliento et al., Citation2019).

Traditional sustainability reporting differentiates ESG disclosures from financial information but may not define the interrelationship between risks, strategy, and other capital forms under firms’ control (de Villiers et al., Citation2017). ESG disclosure can be made on voluntary or mandatory requirements, depending on the authoritative guidelines. However, empirical evidence proves that ESG information disclosed voluntarily may be characterised by limited standards and comparability (Korca & Costa, Citation2021; Muslu et al., Citation2019). In contrast, mandatory disclosure policies are enforced and managed by the authoritative body of a concerned state. Since approaches for ESG disclosure are often not defined, there is some leeway in the expectations of what and how firms should disclose (Hahn et al., Citation2021). Motives for voluntary and mandatory ESG disclosures can be interconnected. For instance, a firm might need to adopt a voluntary disclosure standard for qualitative and comparable ESG disclosures of mandatory requirements. Hence, understanding the institutional motives of ESG disclosures and which specific issues firms must report are paramount.

2.2. Review of ESG disclosure motives

ESG disclosure motives are discussed in this section based on a systematic literature review. The Scopus database was employed as a proxy of source quality. This is because journals indexed in Scopus are considerately more inclusive than its equivalents (e.g. Google Scholar), meeting the strict quality standards (Donthu et al., Citation2021; Paul et al., Citation2021). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) procedure was used to retrieve records from the Scopus database. The keywords (‘ESG’ or ‘environment social and governance’) AND (‘disclosure or reporting or accounting’) AND (‘motive or driver’) were used to retrieve the articles considered for the review. The initial keyword search yielded 55 records. The authors rechecked the filtering procedure to confirm fit-for-purpose and validate the inclusion list of articles. The search results were then exported and saved as a separate Excel file for further review. In this instance, only articles that were published in scholarly journals and discussed at least one ESG disclosure motive were considered (48 articles). The eligible articles were subjected to an in-depth review and content analysis to identify the motives discussed therein. presents the details of keyword searches and records extracted from the Scopus database for the literature review.

Table 1. Details of the keyword search and the number of records extracted from the Scopus database, based on the PRISMA Flow.

2.2.1. Regulatory pressure

With the growing interest in sustainable investing, the demand for information regarding organizations’ ESG activities and regulations has steadily risen (Amel-Zadeh & Serafeim, Citation2018). However, as ESG disclosures continue to be voluntary in most countries (Muslu et al., Citation2019), the formats and contents of ESG disclosures continue to be uneven and unstandardized (Korca & Costa, Citation2021; Muslu et al., Citation2019). This motivates the need for mandatory ESG disclosure regulations. Hence, mandatory ESG disclosures are proposed to enhance the quality and quantity of ESG reports (Arif et al., Citation2021). Consequently, organizations engage in ESG disclosures because they have to comply with regulatory requirements. Thus, ESG disclosure motives are heavily influenced by reporting regulations (Lokuwaduge & Heenetigala, Citation2017) and these regulations are essential for improving ESG disclosure quality (de la Cuesta & Valor, Citation2013).

2.2.2. Stakeholder engagement

The most notable episode in the evolving ESG disclosure landscape is the increasing demand for collaboration among many stakeholders, including ESG organizations, governments, academia, sustainability practitioners, and others. Nowadays, companies and their boards are under unprecedented pressure from stakeholder groups to become more transparent by disclosing their ESG-related decisions (Balogh et al., Citation2022). Hence, more organizations are disclosing ESG information to meet the information requirements of all stakeholders (Khemir et al., Citation2019). Past researchers argue that stakeholder engagement is the key to improving firm ESG policies and sustainable growth (Lokuwaduge & Heenetigala, Citation2017). Further, ESG disclosure offers insights that can enhance the quality of communications between businesses and their stakeholders, leading to more successful business operations that meet the various stakeholders’ sustainability needs (Yip & Yu, Citation2023). The users of companies’ ESG reports are majorly their stakeholders who want to learn more about the influence of ESG issues on their interests. Thus, ESG disclosures are viewed as a response to stakeholder expectations (Aluchna et al., Citation2022).

2.2.3. Investors pressures

ESG investing has aroused the attention of mainstream investors, prompting firms to disclose their ESG information. This might be supported by the fact that any investor can profit from higher returns on equity investments following the disclosure of the firms’ ESG score (Parikh et al., Citation2023). For instance, in the United States, firms are increasingly publishing ESG reports in response to investors’ demand for accessible information about their ESG performance (Kimbrough et al., Citation2022). Investors use ESG information since it is economically significant to investment performance (Amel-Zadeh & Serafeim, Citation2018). Earlier evidence by Galbreath (Citation2013) posits that incorporating sustainable investing with ESG factors is the most prosperous and prominent investment strategy. Consequently, it is unsurprising that investors’ interest in sustainability is growing, and ESG investments are becoming more relevant (Gillan et al., Citation2021). According to Parikh et al. (Citation2023), investors today value ESG investing for two reasons. First, it actively promotes ethical investment practices. Second, ESG investing improves portfolio performance, growing returns while limiting portfolio risk. Moreover, the Benchmark ESG Survey in 2021 discovered that 85% of investors perceive ESG indicators to be more significant than other corporate data when determining their investment decisions (Agnese & Giacomini, Citation2023).

2.2.4. Gaining legitimacy

It can be argued that corporate managers can present improved ESG disclosures to legitimize their business operations, and they can employ ESG disclosures as a corporate veil to evade stringent investigation (Lokuwaduge & Heenetigala, Citation2017). According to the legitimacy perspective, companies disclose to increase their legitimacy among stakeholders as reporting is determined by factors mainly stakeholder pressures (de la Cuesta & Valor, Citation2013). Corporate decision-makers can add their operational legitimacy by promoting ESG disclosures. Hence, existing research demonstrates that companies disclose ESG information to address legitimacy and shareholder concerns (Figueroa et al., Citation2018; Michelon & Rodrigue, Citation2015).

2.2.5. Greenwashing behaviour

The evolving research on ‘greenwashing’ focuses on organizational actions to (1) overstate positive environmental performance to win over one or more stakeholders, as opposed to (2) fully disclosing both negative and positive ESG performance or (3) simply staying quiet (Lyon & Maxwell, Citation2011), or to ‘brownwash’ by disclosing information that undersells their environmental outcomes (Kim & Lyon, Citation2015). Fatemi et al. (Citation2018) argue that to ‘appear more ESG-conscious than it actually is’ (greenwashing), companies with strong ESG performance may choose to limit their ESG disclosure intentionally or even frantically downgrade their ESG practices (‘undue modesty’ or ‘brainwashing’; see Kim and Lyon (Citation2015). Therefore, one of the key issues with ESG disclosure is greenwashing, which is giving incorrect information or the idea that a firm is fairly environmentally conscious (Hameed et al., Citation2021). Large corporations may be under greater financial pressure and exhibit more greenwashing. Financial constraints drive companies’ decisions to engage in greenwashing, and as a result, the financial conditions influence this behaviour. However, these financial constraints can be mitigated, and greenwashing can be reduced through intermediation (Zhang, Citation2022).

2.2.6. Management practices

Business managers are paying attention to ESG to communicate the scope and direction of their activities toward a sustainable environment and ethical society (Arif et al., Citation2021). According to a recent study by Rezaee and Tuo (Citation2017), managerial commitments and information content are crucial in determining the motivations and effects of ESG-related disclosures. In particular, proprietary cost plays a significant influencing role in ESG disclosures. As such, corporations engage in higher ESG disclosures to showcase their better management practices.

2.2.7. Expressing transparency and accountability

Although companies with risky behaviours can increase their ESG disclosure as a ‘window-dressing’ tactic, it is also possible that ESG disclosure improves transparency (Lueg et al., Citation2019). Similarly, Ioannou and Serafeim (Citation2017) suggest that ESG disclosure can increase transparency regarding corporate governance practices and social and environmental impacts. They contend that disclosing ESG-related information drives companies to address these issues efficiently to avoid disclosing poor ESG performance to their stakeholders (Ioannou & Serafeim, Citation2017). Additionally, it’s reasonable that transparency and accountability will result in broader ESG disclosure, which will help people understand how sustainability is related to economic value and, in turn, affect how businesses behave regarding ESG issues. According to a recent study by Chen, Liu, et al. (Citation2023), transparency in pollution information can motivate companies to further improve their environmental disclosure. Therefore, corporations use ESG disclosures to express their accountability and transparency.

2.2.8. Communicating ESG initiatives/performance

Considering the disclosure theory put forth by Dye (Citation1985), a firm’s ESG commitment can be used to predict its ESG disclosure behaviours. Thus, corporations with better ESG performance will likely disclose more about their ESG initiatives, while those with poor ESG performance will likely choose to disclose very little (Fatemi et al., Citation2018). The disclosure theory suggests that companies publicise their performance to differentiate themselves from lower performers while avoiding the negative effects of adverse selection (Akerlof, Citation1970). This is consistent with Cahan et al. (Citation2015), who argue that firms with good ESG performance attract beneficial publicity while realizing greater firm value or lower cost of capital. Thus, ESG disclosures can be inspired by companies’ interest in communicating their ESG initiatives and performance.

2.2.9. Attracting long-term investment

Investors’ interest in ESG information has grown rapidly. In an attempt to understand what motivates investors to utilize ESG information, Amel-Zadeh and Serafeim (Citation2018), discovered that most of the respondents (82%) claimed that ‘they use ESG information as it is financially material to investment performance’. Similarly, it is discovered that investors use public information at the firm level to interact with corporations or as input in the valuation model (Amel-Zadeh & Serafeim, Citation2018). Thus, long-term investors may find out whether the companies are environmentally conscious by merely relying on the firms’ ESG disclosures. Foreign investors will also seek information on companies’ environmental efforts to overcome regional disadvantages and close the information gap (Tsang et al., Citation2019). Further, foreign investors may recommend that management appoint sufficient independent directors to improve the firms’ disclosures, given that firms with a high foreign-investor ratio are more likely to voluntarily disclose ESG-related information (Kim et al., Citation2021). Further, recent evidence supports the motive of ESG disclosures for attracting long-term investment (Balp & Strampelli, Citation2022), demonstrating how long-term investors motivate businesses to enhance their ESG performance and prepare to disclose ESG reports.

2.2.10. Maintaining reputation

According to the social reputation theory, social reputation encourages companies to start sustainability practices (Cai et al., Citation2020) and disclosure (Lu et al., Citation2015), and reputational issues motivate firms to initiate ESG practices and disclosure (Huang & Wang, Citation2022). Thus, it is reasonable to expect companies to engage in sustainability practices to achieve a better social reputation (Uyar et al., Citation2022). Also, regulation and reputation appear to be the primary drivers behind improving ESG disclosure quality (de la Cuesta & Valor, Citation2013). Disclosure can be used to rationalize modifications in ESG policies or to restore damaged reputations (Cho & Patten, Citation2007). Hence, multinational companies operating in sectors with higher reputation risks have the highest disclosures (de la Cuesta & Valor, Citation2013). Many companies have increased their efforts to disclose ESG issues during the past decades to justify their decisions and enhance their reputation (Fatemi et al., Citation2018). Therefore, sustainability disclosure facilitates transparency, enhances corporate reputation, and motivates employees to support the firm’s objectives (Hahn & Kühnen, Citation2013).

2.2.11. Ethical consideration

Despite prior studies suggesting that ESG disclosure is driven more by financial rather than ethical reasons. Ethical considerations seem to play a significant role, particularly in Europe (Amel-Zadeh & Serafeim, Citation2018). This is consistent with the earlier view that engaging with businesses can affect change in the corporate sector and manage ESG issues. Therefore, firms may engage in ESG disclosure practices to address the concerns of ethically responsible investors.

2.2.12. Threat of punishment

A spectrum of corporate behaviours can be used by businesses to reduce or eliminate the possible financial risks of ESG lawsuits. On the one side of this spectrum, it is reasonable to assume that companies will be motivated to enhance their ESG performance and publish ESG reports, whether negative or positive, to show their dedication to ESG issues. On the other hand, Hopwood (Citation2009) argues that firms may be motivated to publish ESG reports intended to confuse readers and evade regulators’ scrutiny and possible civil claims. Thus, avoiding or mitigating the danger of class lawsuits and the ensuing severe financial penalties is one of the motives why some firms are increasing their ESG disclosures. According to Murphy and McGrath (Citation2013), deterrence theory, fuelled by the growing threat of ESG class actions, could motivate businesses to publish ESG reports. Therefore, the threat of punishment is one of the various motives for firms to strategically prepare and disclose ESG reports (Hopwood, Citation2009; Murphy & McGrath, Citation2013). presents the refined ESG disclosure motives identified following the PRISMA protocol outlined in Section 2.2.

Table 2. ESG disclosure motives.

2.3. Study context and research gap

Sustainable development research has shown great interest in India’s environmental performance, particularly considering the country’s recent gross domestic product (GDP) and per capita growth. India is the world’s third-largest carbon emitter annually, with a per capita emission of 1.5 metric tonnes per annum (de la Rue Du Can et al., Citation2019). According to the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB, Citation2023), it is evident that in recent years, industrial pollution in India has increased to alarmingly high levels. Sustainability issues vary widely across industries depending on their business operations and model (Halkos & Skouloudis, Citation2016). The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the de facto global standard for ESG, promotes industry-specific guidelines for ESG reporting (Boiral & Henri, Citation2017). Hence, practitioners and policymakers are increasingly interested in understanding industry-specific ESG disclosures.

The economic practices of environmentally sensitive industries are frequently criticized due to their detrimental effects on environmental and societal welfare (Orazalin & Mahmood, Citation2018). Consequently, companies in these industries tend to disclose their ESG performance most extensively (Halkos & Skouloudis, Citation2016). The oil and gas industry is a crucial driver of India’s accelerated economic expansion (Choudhary et al., Citation2018). The industry trajectories signify India’s increasing demand for natural gas, associated with economic and environmental impacts (Kumar et al., Citation2020). Therefore, the environmentally sensitive oil and gas industry is critical to discussions regarding sustainable development.

There have been few recent studies on the ESG performance of environmentally sensitive industries (e.g. Chen, Song, et al., Citation2023; Gündoğdu et al., Citation2023; Naeem et al., Citation2022). However, directly integrating ESG disclosure is challenging due to the macro-level viewpoint of the studies which emphasizes global issues over firm-specific ones (Chen, Song, et al., Citation2023). Considering the infancy of ESG literature, no prior research has concentrated on the substantive ESG disclosure motives in environmentally sensitive companies like the oil and gas industry. As there is a paucity of research on industry-specific ESG disclosures, it is crucial to understand the motives for ESG disclosure to address environmental concerns. Accordingly, this study’s implicit contribution is related to the Indian oil and gas industry since most companies in the industry are subject to mandatory ESG disclosure regulations. In light of this, the present research explores the fundamental motivations behind disclosing ESG information which advances earlier the understanding of sustainability reporting in environmentally sensitive industries (e.g. Arena et al., Citation2015; Emma & Jennifer, Citation2021).

3. Methodology

Interpretive structural modelling (ISM), introduced by Warfield (Citation1973), is used to uncover connections between specific factors that characterize a particular scenario. It is a theoretical graph technique that organizes identical concepts or factors into a direct graph, where these factors become the vertices, and their contextual interactions appear as the directed arcs or edges (Warfield, Citation1973). ISM helps researchers manage multiple variables in a complicated system by transforming these variables into simple hierarchical models of the system variables. The ISM technique is also a group learning process since it requires expert group judgment (consensus approach). It is interpretive because it uses the expert group’s collective judgment to give meaning to distinctive factors and determine whether and how each factor is related to others in the system. It is structural as the procedure produces a structural model showing how the system factors relate. Also, it is a modelling technique since the result is a digraph that presents system factors in a structured and hierarchical pattern.

The FISM is an extension of the original ISM (Warfield, Citation1973), which provides answers to questions like ‘what (basic construct/variable)’ and ‘how (which construct leads to which one)’, but does not specify ‘to what extent (a particular construct/variable leads to the other)’. Hence, FISM overcomes this limitation by integrating the degree of dominance of these interactions (Abbas et al., Citation2022).

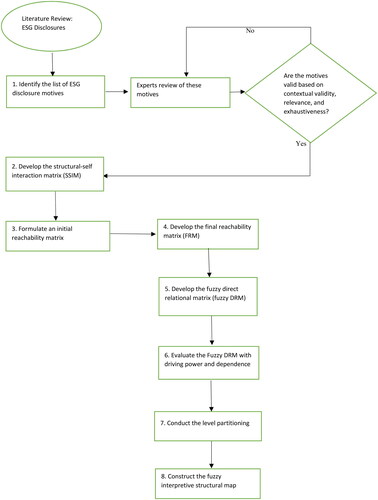

To address the first and second research objectives, this study adopted the methodological steps outlined in this section. The methodology has been discovered to present an insightful structure through a hierarchical graphical model of elements in prior research studying similar relationships across various contexts. The steps followed in this study are presented as follows and depicted in .

Step 1: Identify the factors under study. To some extent, these factors must be homogeneous about the subject being studied (e.g. the motivations behind ESG disclosure). This procedure could be done using various techniques, including surveys, focus groups, research, and literature review or combining both.

Step 2: As the structural model would be created by the judgments of a few domain experts, a structural self-interaction matrix (SSIM) is developed. One SSIM is generated for group decision since the group decides on consensus. The experts are requested to decide on the contextual relationship ‘R’ between two motives. Four symbols (V, A, X, and O) are used in the ISM approach to represent the relationship pattern among a pair of variables:

V; i is related to j but not in both ways;

A; j is related to i but not in both ways

X; i is related to j, and j is related to i (i.e. both directions);

O; no relation between i and j.

Step 3: Formulate an initial reachability matrix (IRM) for the SSIM by applying the rules stated in the previous step.

Step 4: Develop the final reachability matrix (FRM) by identifying transitive interactions, such that if variable ‘A’ is related to variable ‘B’ and variable ‘B’ is related to variable ‘C’, then A is automatically related to C (Qureshi et al., Citation2008).

Step 5: Develop a fuzzy direct relational matrix (fuzzy DRM) using FRM. The fuzzy set theory procedure uses the FRM as a binary direct reachability matrix. In doing this, experts’ opinion is used to replace these binary numbers with appropriate fuzzy values that consider the degree of dominance of each linked relationship. The resulting matrix is referred to as a Fuzzy DRM. Researchers using FISM are free to consider a factor’s degree of dominance when deciding whether or not to include it as related to another factor (Abbas et al., Citation2022). In this case, even the smallest (0.1) degree of interaction was regarded as a relationship by the authors.

Step 6: Evaluate the reachability (driving power) and antecedent (dependent power) among the variables. The Fuzzy DRM is used to estimate the driving power and dependence for each of the variables. The driving power of a factor is the total amount of factors it influences (itself inclusive). In contrast, the dependence power of a factor refers to the total amount of factors that might affect it (itself inclusive).

Step 7: Design level partitioning. The factors are divided into a hierarchical structure with k levels, which offers significant insights regarding these factors.

Step 8: Create the final digraph and remove the relationship of the reachability matrix and transitive links. The contextual relationships serve as the digraph’s edges, while the factors are shown as its vertices. Then, the final model is drawn by integrating the level partitions in Step 7.

3.1. Fuzzy MICMAC analysis

Examine the variables’ power that drives and depends. To extend the FISM and address the third research objective, the Fuzzy MICMAC analysis measures the driving power and dependence of the motives. These motives are categorized into four clusters by developing a map:

Variables with a high driving power and a low dependence are referred to as Independent variables.

Variables with strong driving power and strong dependence are termed linking variables.

Variables with strong dependence but poor driving power are dependent variables.

Variables with weak driving power and dependence are referred to as autonomous variables.

4. Dana analysis and results

The analysis procedures discussed in Section 3 are applied to ascertain the pertinent connections between the ESG disclosure motives.

4.1. Fuzzy ISM

To ascertain the relationship between the identified motives and, as a result, establish priority motives. The following steps are taken.

Step 1: Identify and list the variables under consideration. presents all of the set of ESG disclosure reasons. These motivations were discovered after a thorough literature review, as Section 2 explains.

Step 2: Construct an SSIM for the experts. To finalize the earlier identified motives and develop the SSIM, 5 experts from the Indian oil and gas industry associated with sustainability were consulted. This process was supervised and moderated by 2 academicians. Moderator 1 is an Associate Professor and a Director of a research centre in a private university who has published over 20 peer-reviewed journal articles in management and sustainability. Moderator 2 is an Associate Professor of management and the current Head of Sustainability of a private university with 12 years of teaching experience in Sustainability-related courses. Experts 1 and 2 are affiliated with upstream oil and gas companies with 5 and 7 years of experience, respectively. In contrast, Experts 3 and 4 are the Head of Sustainability at downstream oil and gas firms with 10 and 11 years of experience, respectively. Meanwhile, Expert 5 is the sustainability head of a business consultancy and services firm with 6 years of experience. All the experts have more than five years of expertise in sustainability and have managed ESG initiatives, particularly at the strategic level, for their respective organizations. They occupy positions at the top and middle of the industry and are sufficiently knowledgeable about possible motives for ESG disclosure in the sector. This indicates that the experts’ collective viewpoints and judgments correspond to those of their respective organizations.

The study and the associated questionnaire, created following the FISM framework, were explained to experts. First, experts’ opinion was requested regarding the identified ESG disclosure motives. With the guidance of the moderators, these motives are further evaluated from three perspectives, i.e. contextual validity, relevance, and exhaustiveness. Surprisingly, in this phase, the experts unanimously agreed that all the 12 motives gathered from the literature review were valid given the present state-of-the-art on ESG disclosure in the oil and gas industry. Further, equivalent codes were assigned to the motives for ease of depiction. Following the finalization, experts are requested to look into and describe every plausible contextual association between each pair of these motives. At this point, every variable is analyzed in conjunction with every other variable to determine ‘whether A leads to B’. Further, FISM also looks for a response to the question of how strongly ‘A leads to B’ for each ‘Yes’. The experts had some disagreements regarding the relationship patterns and degree of dominance among the motives, however, these were resolved following the moderators’ intervention. Following the step outlined in Step 2 of Section 3, each ‘Yes’ is then transformed into ‘V or X’ and ‘No’ into ‘A or O’ to generate an SSIM. presents the SSIM for the Experts’ consensus.

Table 3. Structural self-interaction matrix (SSIM).

Step 3: Converting the SSIM to the IRM. By replacing V, A, X, and O with 1 and 0, as indicated in Step 3 of Section 3, the SSIM can now be transformed into a binary matrix referred to as the IRM. The procedures for replacing 1s and 0s are in line with (Farris & Sage, Citation1975). The IRM corresponding to the SSIM from is shown in .

Table 4. Initial reachability matrix.

Step 4: Generate the final reachability matrix (FRM). Using Step 4 (Section 3), the FRM generated is shown in .

Table 5. Final reachability matrix.

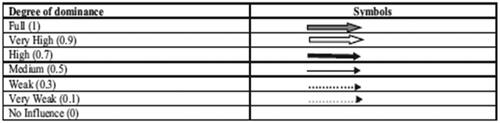

Step 5: Fuzzy direct relational matrix (Fuzzy DRM). Using the scheme shown in , the FRM is transformed into the Fuzzy DRM in line with the expert opinion. As described in Step 5 of Section 3, the procedure entails substituting the binary numbers with the interaction’s degree of dominance on an array (0,0.1,0.3…,1) from no impact to full dominance.

Table 6. Scheme for the degree of perceived dominance.

The integration of the fuzzy notion rationalizes and enhances the visibility of the exact degree of impact in the fuzzy direct connection (see ). Since alternate relationships depicted by the letter ‘V’ in the SSIM may or may not indicate the exact same level of influence. For instance, although there is a ‘V’ form of the relationship between ‘regulatory pressures’, ‘investors pressures’, and ‘greenwashing behaviour’, nevertheless, the degree of dominance varies slightly. Furthermore, the degree of influence can differ in an ‘X’ type interaction where two motives are influencing one another, for example, investors’ pressures and expressing transparency and accountability.

Table 7. Fuzzy direct reachability matrix.

Step 6: Evaluate the Fuzzy DRM with reachability set and antecedent set among the motives. Further, the Fuzzy DRM is broadened to obtain the driving power and dependence of the motives by totaling all rows and columns, as shown in .

Table 8. Fuzzy direct reachability matrix with driving power and dependence.

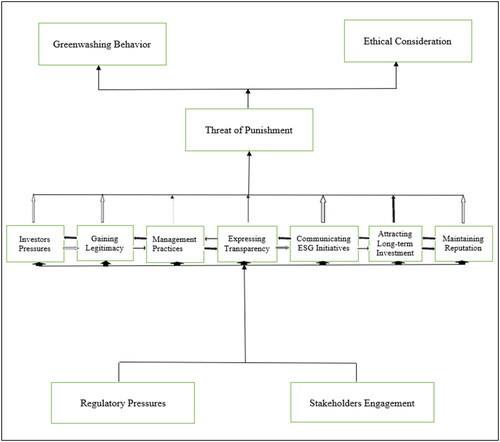

Step 7: Establish level partitions. Each variable possesses a reachability set and an antecedent set in the FRM (Warfield, Citation1974). The variable in question and any additional variables it might aid in achieving make up the reachability set of that variable (Nishat Faisal et al., Citation2006). The variable plus any additional variables that could affect it make up an antecedent set for that particular variable (Nishat Faisal et al., Citation2006). For each variable, the intersection among the reachability set and antecedent set can be determined. The top level of the FISM hierarchy is occupied by motives with identical reachability and intersection sets, which will not assist in achieving other motives above their level. The top-level motivator is then eliminated from the following iteration. In , the outcomes for iterations I through IV are presented (see Appendices A–D). The results demonstrate that Level I encompass greenwashing behaviour and ethical considerations. Level II only covers the threat of punishment. While Level III includes seven motives, Level IV entails two motives, i.e. regulatory pressure and stakeholder engagement. The defined levels support the construction of the FISM model.

Table 9. Level partitioning.

Step 8: Construct the fuzzy interpretive structural map. The level partitions from Step 7 are used to construct the hierarchical structure of these motives. The motives are placed in a hierarchy according to their corresponding levels. After establishing a defined hierarchy, the next step is determining the direction of the relationships within and among the variables. This is accomplished by drawing bi-directional lines at a specific level and in between levels following a specific degree of the arrows’ thickness and regularity (see ). The final developed model is referred to as the FISM model and is shown in .

Figure 2. FISM model symbols.

Source: Abbas et al. (Citation2022).

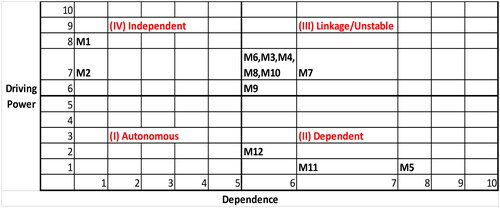

4.2. Classification of motives: fuzzy MICMAC analysis

The MICMAC analysis is primarily used to investigate the interdependence and power of the variables under consideration. In the present study, MICMAC analysis makes identifying the driving forces behind the general structure easier. The sum of all values defined in the columns and rows of the fuzzy DRM shown in will indicate each motive’s driving power and dependence. All identified motivations can be graphically presented into four distinct quadrants using fuzzy MICMAC analysis, as illustrated in . These quadrants are explained as follows:

Quadrant 1 (Autonomous motives): The low driving power and low dependence characterized the motives in this quadrant. These motives are rarely part of the system. Surprisingly, the current model has no elements in this quadrant. The absence of ESG disclosure motives in this quadrant signifies the stability of the overall model.

Quadrant 2 (Dependent motives): ESG disclosure motives in this quadrant possess significant dependencies but little driving power. Greenwashing behaviour (M5), Ethical consideration (M11), and Threat of Punishment (M12) are the ESG disclosure motives in this quadrant.

Quadrant 3 (Linkage/Unstable motives): ESG disclosure motives in this quadrant have significant driving power and dependence. Since these motives are regarded as unstable, any action taken to address them will also have an impact on other motives. These motives show a self-feedback mechanism. The motives in this quadrant includes M3, M4, M6, M7, M8, M9, and M10.

Quadrant 4 (Independent/Driving motives): Those motives that have high driving power but low dependence appear in this quadrant. Typically, the major motives are those that have a very strong driving power because they are responsible for driving the entire system. The two motives in this quadrant include Regulatory pressure (M1) and Stakeholder engagement (M2).

5. Results and discussions

An essential yet neglected aspect of ESG is understanding corporate ESG disclosure motivations. Using a qualitative approach based on stakeholder and legitimacy theories, this research identified 12 factors motivating ESG disclosure practices. All these 12 motives were confirmed to be valid at the current phase of ESG disclosure as per experts’ consensus. shows the links between the 12 evident ESG disclosure motives. These motives were organized into a four-level hierarchical model using FISM. The study discusses some interesting findings by comparing the results with extant literature. The factors at the higher levels of the hierarchy are influenced by those at the lower levels. Greenwashing behaviour and ethical consideration motives are present at Level I, as seen in . The threat of punishment is the only Level II motivating factor. Among the Level III disclosure motives are investors’ pressure, gaining legitimacy, management practices, expressing transparency, communicating ESG initiatives, attracting long-term investment, and maintaining reputation. Regulatory pressure and stakeholder engagement are placed at Level IV. The fuzzy MICMAC analysis further highlights the absence of an autonomous motive, implying that although regulatory pressures and stakeholder engagement appear independent regardless of other motives, they have more driving power than dependence.

According to the experts’ perspectives, Greenwashing behaviour and Ethical consideration are the ultimate factors motivating ESG disclosures for the Indian oil and gas industry. These motives, which are at the top of the hierarchical model, can be attained by other factors located at a lower level of the hierarchy. Although motivation studies rarely address greenwashing as an underlying motive driving ESG disclosure, few recent studies have shed light on the impact of greenwashing in motivating ESG disclosure. For instance, Zhang (Citation2022) demonstrates that highly leveraged companies may have increased financial pressure and thus exhibit more greenwashing behaviour. Similarly, a prior study by Yu et al. (Citation2020) states that ESG disclosures are unreliable and that a company’s greenwashing practices affect investment choices involving ESG variables. Thus, the findings of the present study extend the results of previous studies on the influence of firms greenwashing behaviours in ESG disclosure. Due to the lack of universal standards for ESG disclosures, concerns over ‘greenwashing’ have grown (de Silva Lokuwaduge & De Silva, Citation2022). In light of this, it is important to recognize the power of greenwashing and ethical considerations despite the dominance of several lower-level motivations.

The results also highlight seven motives of the linkage/unstable cluster: investors’ pressure, gaining legitimacy, management practices, expressing transparency, communicating ESG initiatives, attracting long-term investment, and maintaining reputation. These motives are highly unstable hence, any decision to respond to them will impact other motives and provide additional insight into themselves. The first motivating factor (i.e. investor pressure) influences the individual’s need for ESG reports for economic decision-making rather than the firms’ internal requirements. This is consistent with earlier evidence that organizations are disclosing more ESG information to meet the requirements of stakeholders, especially investors since it is economically significant to investment performance (Amel-Zadeh & Serafeim, Citation2018; Kimbrough et al., Citation2022). The other six motives, on the other hand (i.e. gaining legitimacy, management practices, expressing transparency, communicating ESG initiatives, attracting long-term investment, and maintaining reputation) relate to the motivations for ESG disclosures to achieve specific economic benefits. These motives were considered significant motives behind ESG disclosures. Nevertheless, the measures initiated regarding them may not be effective, as the findings suggest that other factors highly impact them.

Surprisingly, both the regulatory pressures and stakeholder engagement motives are identified as having independent features (see ). Although these variables have minimal dependence power, they have higher driving power. Given that they are the most significant motives affecting ESG disclosures, they may be viewed as the most important of all these motives. The results are consistent with Choudhary et al. (Citation2018), which suggest regulatory compliance and brand reputation are among the main factors driving environmental accounting in the Indian oil industry. Moreover, the results of this study are in line with the relevant literature, highlighting in particular that ESG disclosure motives are influenced by reporting regulations (Lokuwaduge & Heenetigala, Citation2017) and stakeholder engagement (Khemir et al., Citation2019). Regulation is also essential for enhancing ESG disclosure quality (de la Cuesta & Valor, Citation2013), and better ESG-related disclosures are more likely to be made by corporations with higher reporting quality (Hamad et al., Citation2023). Therefore, more feasible regulations are crucial in improving ESG reporting quantity and quality.

5.1. Research implication

Theoretically, this paper contributes in many essential ways. First, to the authors’ best knowledge, it is the first study to offer insights into ESG disclosure motives of environmentally sensitive industry by employing a qualitative approach. These detailed motives will not only aid in improving researchers’ general understanding of the ESG disclosure phenomenon but will also serve as a basis for more future quantitative empirical studies. Researchers can investigate additional captivating dimensions of ESG disclosure by studying these comprehensive motives. In general, this qualitative exploratory study strengthens studies that quantitatively assessed ESG disclosure motives by offering additional insights, particularly in an emerging economy. Second, this study is a first step toward understanding how these motives interact with one another. It supports the widely held belief that some of the motivations are interconnected. For instance, Zhang (Citation2022) suggests that financial constraints drive companies’ decisions to engage in greenwashing. This research also sheds new light on the hierarchically ordered structure of ESG disclosure motives and indicates that oversimplifying the motives to just one standalone level would be a significant oversight. Therefore, it is reasonable to infer that these results provide a strong foundation for conceptualizing future quantitative analyses to understand the causal relationships between motives. Third, ESG research has yet to extensively use qualitative methods like FISM based on stakeholder and legitimacy theories. Contrary to other qualitative techniques, the layered interview and FISM approach’s unique benefits enable the discovery of correlations and dominance between the motives. This shows that researchers may effectively adopt this approach to examine comparable questions, such as why other organizational stakeholders (e.g. investors, creditors, suppliers) require ESG information. Hence, this method can be used in future research to produce more insightful results.

6. Conclusion and future research

The motives for disclosing ESG information will directly affect the quantity, quality, and attributes of the report (Arif et al., Citation2021). These motives range from crucial regulatory and stakeholders’ pressures to greenwashing behaviour and ethical considerations that affect the success of ESG disclosure in the long run. Consequently, regulatory pressures and stakeholder engagement serve as a foundation for the entire hierarchical framework, as seen in the developed model. Adopting universal reporting frameworks may have some impact on these motivations since firms will need to comply with the requirements in their ESG disclosures. Stakeholders will find it easier to compare reports and thoroughly assess the content using these frameworks (Tschopp & Nastanski, Citation2014). These frameworks, therefore, will encourage companies to provide reliable ESG information (Kouloukoui et al., Citation2019; Michelon et al., Citation2015). They will also solidify the foundation of the other motives. Thus, the power of the other motives located at higher levels of the hierarchy will be impacted, if not much, at least somewhat. As a result, the influence of greenwashing behaviour and ethical considerations, which are at the top of this model, will also be moderated. The Level II (tactical) and Level III (operational) motives (with strong driving power) occupy the middle positions in the FISM hierarchy and are quite unstable. These motives should also be considered carefully. Ultimately, this study suggests that the best way to facilitate comprehensive ESG disclosures would be to initially manage the strategic (level IV) motives. Then, monitoring the tactical motives will result in addressing the performance (level I) motives. The results of this study will help decision-makers identify the primary motives of ESG disclosure, which calls for persistent government intervention to ensure that legal frameworks are put in place. Hence, decisions regarding ESG would be enhanced if they were supported by empirical evidence (Larcker et al., Citation2022).

The present study is limited to motivations for disclosing ESG information by environmentally sensitive industry in an emerging economy. Future studies may explore the other contextual elements or stakeholders associated with ESG reporting. The proposed model is based on a review of the literature and the opinions of experts in the industry. Hence, the model is recommended to be taken to the next level by future studies to test its validity to either support or criticize the findings herein. Additionally, present corporate initiatives and the associated barriers to comprehensive ESG disclosures may be of interest as a recent study by Di Tullio et al. (Citation2020) shows that many organizations publish ESG reports using non-accounting terms and data, while others completely disregard the mandatory disclosure regulations. Surprisingly, Edmans (Citation2023) proposed that there should be a less quantitative focus on ESG, which could lead to two distinct research paths. One is to compile qualitative evaluations of ESG, as qualitative aspects are especially prone to market mispricing since some investors embrace ‘ESG-by-numbers’ strategies. The other is to continue using numerical data but to focus on quality as opposed to quantity. Thus, this study offers an understandable framework and classification of the motivations for corporate ESG disclosures, with implications and insights for ESG stakeholders. Also, it adds to the extant literature by providing explicit context on ESG disclosure, which is expected to set the ‘prelude’ to implementing mandatory ESG disclosure regulations.

Author contributions

R.A.P. conceptualized and designed the study and interpreted findings; M.S.K. performed the data collection, analysis, and drafting of the manuscript; V.S. revised it critically for intellectual content and the final approval of the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Muhammad Sani Khamisu

Muhammad Sani Khamisu is a Research Fellow at Symbiosis International (Deemed University), India. He holds a Master’s degree in Accounting and Finance and is currently pursuing a PhD in Environmental Accounting. His main research areas include issues related to environmental, social and governance (ESG), sustainability accounting, international finance, international education and sustainable development.

Ratna Achuta Paluri

Ratna Achuta Paluri is an ardent academician with more than 20 years of experience in business education and research. She holds a Ph.D. in Management and an M.B.A. in Finance. She is an Associate Professor at Symbiosis Institute of Operations Management, Nashik. She is a registered PhD guide in the area of Management. Her research areas include Managerial Economics, International Business, Consumer Finance and Corporate Social Responsibility.

Vandana Sonwaney

Vandana Sonwaney, an MBA in Marketing and PhD in Management, has versatile experience in research training, marketing, academics and Institution Management for over 26 years. She is currently the Director and professor at Symbiosis Institute of Operations Management. She is also a registered PhD guide in the area of Management. Her research areas include Operations Management, Education, Marketing Research, Corporate training, and Academic and institution management.

Notes

1 The largest 100 companies in each of 58 countries, territories and jurisdictions (5800 companies in total).

2 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Code Red for humanity reporting.

References

- Abbas, H., Asim, Z., Ahmed, Z., & Moosa, S. (2022). Exploring and establishing the barriers to sustainable humanitarian supply chains using fuzzy interpretive structural modeling and fuzzy MICMAC analysis. Social Responsibility Journal, 18(8), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-12-2020-0485

- Aboud, A., & Diab, A. (2018). The impact of social, environmental and corporate governance disclosures on firm value. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 8(4), 442–458. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAEE-08-2017-0079

- Agnese, P., & Giacomini, E. (2023). Bank’s funding costs: Do ESG factors really matter? Finance Research Letters, 51, 103437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2022.103437

- Akerlof, G. A. (1970). The market for ‘lemons’: Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84(3), 488. https://doi.org/10.2307/1879431

- Alsayegh, M. F., Abdul Rahman, R., & Homayoun, S. (2020). Corporate economic, environmental, and social sustainability performance transformation through ESG disclosure. Sustainability, 12(9), 3910. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093910

- Aluchna, M., Roszkowska-Menkes, M., & Kamiński, B. (2022). From talk to action: The effects of the non-financial reporting directive on ESG performance. Meditari Accountancy Research, 31(7), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-12-2021-1530

- Amel-Zadeh, A., & Serafeim, G. (2018). Why and how investors use ESG information: Evidence from a global survey. Financial Analysts Journal, 74(3), 87–103. https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v74.n3.2

- Aragòn-Correa, J. A., Marcus, A. A., & Vogel, D. (2020). The effects of mandatory and voluntary regulatory pressures on firms’ environmental strategies: A review and recommendations for future research. Academy of Management Annals, 14(1), 339–365. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2018.0014

- Arena, C., Bozzolan, S., & Michelon, G. (2015). Environmental reporting: Transparency to stakeholders or stakeholder manipulation? An analysis of disclosure tone and the role of the board of directors. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 22(6), 346–361. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1350

- Arif, M., Sajjad, A., Farooq, S., Abrar, M., & Joyo, A. S. (2021). The impact of audit committee attributes on the quality and quantity of environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosures. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 21(3), 497–514. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-06-2020-0243

- Azimli, A., & Cek, K. (2023). Can sustainability performance mitigate the negative effect of policy uncertainty on the firm valuation? Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal. Ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-09-2022-0464

- Balogh, I., Srivastava, M., & Tyll, L. (2022). Towards comprehensive corporate sustainability reporting: An empirical study of factors influencing ESG disclosures of large Czech companies. Society and Business Review, 17(4), 541–573. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBR-07-2021-0114

- Balp, G., & Strampelli, G. (2022). Institutional investor ESG engagement: The European experience. European Business Organization Law Review, 23(4), 869–904. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40804-022-00266-y

- Barros, V., Verga Matos, P., Miranda Sarmento, J., & Rino Vieira, P. (2022). M&A activity as a driver for better ESG performance. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 175, 121338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121338

- Bizoumi, T., Lazaridis, S., & Stamou, N. (2019). Innovation in stock exchanges: Driving ESG disclosure and performance. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 31(2), 72–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/jacf.12348

- Blomqvist, A., & Stradi, F. (2022). Responsible investments: An analysis of preference – The influence of local political views on the return on ESG portfolios. The European Journal of Finance, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/1351847X.2022.2137423

- Boiral, O., & Henri, J. F. (2017). Is sustainability performance comparable? A study of GRI reports of mining organizations. Business & Society, 56(2), 283–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650315576134

- Broadstock, D. C., Managi, S., Matousek, R., & Tzeremes, N. G. (2019). Does doing ‘good’ always translate into doing ‘well’? An eco‐efficiency perspective. Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(6), 1199–1217. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2311

- Bui, B., Houqe, M. N., & Zaman, M. (2020). Climate governance effects on carbon disclosure and performance. The British Accounting Review, 52(2), 100880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2019.100880

- Cahan, S. F., Chen, C., Chen, L., & Nguyen, N. H. (2015). Corporate social responsibility and media coverage. Journal of Banking & Finance, 59, 409–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2015.07.004

- Cai, X., Gao, N., Garrett, I., & Xu, Y. (2020). Are CEOs judged on their companies’ social reputation? Journal of Corporate Finance, 64, 101621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2020.101621

- Chen, H., Liu, S., Yang, D., & Zhang, D. (2023). Automatic air pollution monitoring and corporate environmental disclosure: a quasi-natural experiment from China. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 14(3), 538–564. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-07-2022-0385

- Chen, S., Song, Y., & Gao, P. (2023). Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance and financial outcomes: Analyzing the impact of ESG on financial performance. Journal of Environmental Management, 345, 118829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.118829

- Cho, C. H., & Patten, D. M. (2007). The role of environmental disclosures as tools of legitimacy: A research note. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 32(7–8), 639–647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2006.09.009

- Choudhary, P., Srivastava, R. K., & De, S. (2018). Integrating greenhouse gases (GHG) assessment for low carbon economy path: Live case study of Indian national oil company. Journal of Cleaner Production, 198, 351–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.032

- CPCB (2023). Industrial pollution control. Central Pollution Control Board. Retrieved from https://cpcb.nic.in/online-monitoring-of-industrial-emission/

- de la Cuesta, M., & Valor, C. (2013). Evaluation of the environmental, social and governance information disclosed by Spanish listed companies. Social Responsibility Journal, 9(2), 220–240. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-08-2011-0065

- de la Rue Du Can, S. D. L. R., Khandekar, A., Abhyankar, N., Phadke, A., Khanna, N. Z., Fridley, D., & Zhou, N. (2019). Modeling India’s energy future using a bottom-up approach. Applied Energy, 238, 1108–1125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.01.065

- de Silva Lokuwaduge, C. S., & De Silva, K. M. (2022). ESG risk disclosure and the risk of green washing. Australasian Business, Accounting and Finance Journal, 16(1), 146–159. https://doi.org/10.14453/aabfj.v16i1.10

- de Villiers, C., Venter, E. R., & Hsiao, P.-C. K. (2017). Integrated reporting: Background, measurement issues, approaches and an agenda for future research. Accounting & Finance, 57(4), 937–959. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12246

- de Vincentiis, P. (2023). Do international investors care about ESG news? Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 15(4), 572–588. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRFM-11-2021-0184

- Di Tullio, P., Valentinetti, D., Nielsen, C., & Rea, M. A. (2020). In search of legitimacy: A semiotic analysis of business model disclosure practices. Meditari Accountancy Research, 28(5), 863–887. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-02-2019-0449

- Dixit, S., Verma, H., & Priya, S. S. (2022). Corporate social responsibility motives of Indian firms. Journal of Modelling in Management, 17(2), 518–538. https://doi.org/10.1108/JM2-07-2020-0190

- Donthu, N., Kumar, S., Mukherjee, D., Pandey, N., & Lim, W. M. (2021). How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 133, 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.070

- Dye, R. A. (1985). Disclosure of nonproprietary information. Journal of Accounting Research, 23(1), 123. https://doi.org/10.2307/2490910

- Edmans, A. (2023). The end of ESG. Financial Management, 52(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/fima.12413

- Emma, G. M., & Jennifer, M. F. (2021). Is SDG reporting substantial or symbolic? An examination of controversial and environmentally sensitive industries. Journal of Cleaner Production, 298, 126781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126781

- Farris, D. R., & Sage, A. P. (1975). On the use of interpretive structural modeling for worth assessment. Computers & Electrical Engineering, 2(2–3), 149–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/0045-7906(75)90004-X

- Fatemi, A., Glaum, M., & Kaiser, S. (2018). ESG performance and firm value: The moderating role of disclosure. Global Finance Journal, 38, 45–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfj.2017.03.001

- Fazzini, M., & Dal Maso, L. (2016). The value relevance of ‘assured’ environmental disclosure. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 7(2), 225–245. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-10-2014-0060

- Figueroa, E. G., Solano, S. E., Montoya, D. A., & Casado, P. P. (2018). The business legitimacy and its relationship with the corporate social responsibility: Analysis of Mexico and Spain through the case method. In Organizational legitimacy (pp. 197–215). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75990-6_12

- Flammer, C., & Bansal, P. (2017). Does a long‐term orientation create value? Evidence from a regression discontinuity. Strategic Management Journal, 38(9), 1827–1847. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2629

- Galbreath, J. (2013). ESG in focus: The Australian evidence. Journal of Business Ethics, 118(3), 529–541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1607-9

- Garcia, A. S., Mendes-Da-Silva, W., & Orsato, R. J. (2017). Sensitive industries produce better ESG performance: Evidence from emerging markets. Journal of Cleaner Production, 150, 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.02.180

- Giannarakis, G., Konteos, G., & Sariannidis, N. (2014). Financial, governance and environmental determinants of corporate social responsible disclosure. Management Decision, 52(10), 1928–1951. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-05-2014-0296

- Gillan, S. L., Koch, A., & Starks, L. T. (2021). Firms and social responsibility: A review of ESG and CSR research in corporate finance. Journal of Corporate Finance, 66, 101889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2021.101889

- Gündoğdu, H. G., Aytekin, A., Toptancı, Ş., Korucuk, S., & Karamaşa, Ç. (2023). Environmental, social, and governance risks and environmentally sensitive competitive strategies: A case study of a multinational logistics company. Business Strategy and the Environment, 32(7), 4874–4906. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3398

- Hahn, R., & Kühnen, M. (2013). Determinants of sustainability reporting: A review of results, trends, theory, and opportunities in an expanding field of research. Journal of Cleaner Production, 59, 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.07.005

- Hahn, R., Reimsbach, D., Kotzian, P., Feder, M., & Weißenberger, B. E. (2021). Legitimation strategies as valuable signals in nonfinancial reporting? Effects on investor decision-making. Business & Society, 60(4), 943–978. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650319872495

- Halkos, G., & Skouloudis, A. (2016). Exploring the current status and key determinants of corporate disclosure on climate change: Evidence from the Greek business sector. Environmental Science & Policy, 56, 22–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.10.011

- Hamad, S., Lai, F. W., Shad, M. K., Khatib, S. F. A., & Ali, S. E. A. (2023). Assessing the implementation of sustainable development goals: Does integrated reporting matter? Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 14(1), 49–74. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-01-2022-0029

- Hameed, I., Hyder, Z., Imran, M., & Shafiq, K. (2021). Greenwash and green purchase behavior: An environmentally sustainable perspective. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 23(9), 13113–13134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-01202-1

- Hoang, H. V. (2023). Environmental, social, and governance disclosure in response to climate policy uncertainty: Evidence from US firms. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 26(2), 4293–4333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-022-02884-5

- Hopwood, A. G. (2009). Accounting and the environment. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 34(3–4), 433–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2009.03.002

- Hsueh, L. (2017). Transnational climate governance and the global 500: Examining private actor participation by firm-level factors and dynamics. International Interactions, 43(1), 48–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050629.2016.1223929

- Huang, D. Z. X. (2021). Environmental, social and governance (ESG) activity and firm performance: A review and consolidation. Accounting & Finance, 61(1), 335–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12569

- Huang, K.-C., & Wang, Y.-C. (2022). Do reputation concerns motivate voluntary initiation of corporate social responsibility reporting? Evidence from China. Finance Research Letters, 47, 102611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2021.102611

- Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2017). The consequences of mandatory corporate sustainability reporting, No. 11–100.

- Jasni, N. S., Yusoff, H., Zain, M. M., Md Yusoff, N., & Shaffee, N. S. (2019). Business strategy for environmental social governance practices: Evidence from telecommunication companies in Malaysia. Social Responsibility Journal, 16(2), 271–289. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-03-2017-0047

- Khemir, S., Baccouche, C., & Ayadi, S. D. (2019). The influence of ESG information on investment allocation decisions. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 20(4), 458–480. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAAR-12-2017-0141

- Kim, E., Kim, S., & Lee, J. (2021). Do foreign investors affect carbon emission disclosure? Evidence from South Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10097. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910097

- Kim, E.-H., & Lyon, T. P. (2015). Greenwash vs. Brownwash: Exaggeration and undue modesty in corporate sustainability disclosure. Organization Science, 26(3), 705–723. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2014.0949

- Kimbrough, M. D., Wang, X. (., Wei, S., & Zhang, J. (. (2022). Does voluntary ESG reporting resolve disagreement among ESG rating agencies? European Accounting Review, 33(1), 15–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2022.2088588

- Korca, B., & Costa, E. (2021). Directive 2014/95/EU: Building a research agenda. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 22(3), 401–422. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAAR-05-2020-0085

- Kouloukoui, D., Sant’Anna, Â. M. O., da Silva Gomes, S. M., de Oliveira Marinho, M. M., de Jong, P., Kiperstok, A., & Torres, E. A. (2019). Factors influencing the level of environmental disclosures in sustainability reports: Case of climate risk disclosure by Brazilian companies. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 26(4), 791–804. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1721

- KPMG (2022). Big shifts, small steps, Survey of sustainability reporting 2022.

- Kumar, P., & Firoz, M. (2022). Determinants of environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosures of top 100 Standard and Poor’s Bombay Stock Exchange firms listed in India. Sri Lanka Journal of Social Sciences, 45(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.4038/sljss.v45i1.8074

- Kumar, V. V., Shastri, Y., & Hoadley, A. (2020). A consequence analysis study of natural gas consumption in a developing country: Case of India. Energy Policy, 145, 111675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111675

- Larcker, D. F., Tayan, B., & Watts, E. M. (2022). Seven myths of ESG. European Financial Management, 28(4), 869–882. https://doi.org/10.1111/eufm.12378

- Lee, C. C., & Lee, C. C. (2022). How does green finance affect green total factor productivity? Evidence from China. Energy Economics, 107, 105863. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2022.105863

- Lokuwaduge, C. S. D. S., & Heenetigala, K. (2017). Integrating environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure for a sustainable development: An Australian study. Business Strategy and the Environment, 26(4), 438–450. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1927

- Lu, Y., Abeysekera, I., & Cortese, C. (2015). Corporate social responsibility reporting quality, board characteristics and corporate social reputation. Pacific Accounting Review, 27(1), 95–118. https://doi.org/10.1108/PAR-10-2012-0053

- Lueg, K., Krastev, B., & Lueg, R. (2019). Bidirectional effects between organizational sustainability disclosure and risk. Journal of Cleaner Production, 229, 268–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.379

- Lyon, T. P., & Maxwell, J. W. (2011). Greenwash: Corporate Environmental Disclosure under Threat of Audit. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 20(1), 3–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-9134.2010.00282.x

- Michelon, G., & Rodrigue, M. (2015). Demand for CSR: Insights from shareholder proposals. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal, 35(3), 157–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969160X.2015.1094396

- Michelon, G., Pilonato, S., & Ricceri, F. (2015). CSR reporting practices and the quality of disclosure: An empirical analysis. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 33, 59–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2014.10.003

- Murphy, D., & McGrath, D. (2013). ESG reporting – Class actions, deterrence, and avoidance. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 4(2), 216–235. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-Apr-2012-0016

- Muslu, V., Mutlu, S., Radhakrishnan, S., & Tsang, A. (2019). Corporate social responsibility report narratives and analyst forecast accuracy. Journal of Business Ethics, 154(4), 1119–1142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3429-7

- Naeem, N., Cankaya, S., & Bildik, R. (2022). Does ESG performance affect the financial performance of environmentally sensitive industries? A comparison between emerging and developed markets. Borsa Istanbul Review, 22, S128–S140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2022.11.014

- Nishat Faisal, M., Banwet, D. K., & Shankar, R. (2006). Supply chain risk mitigation: Modeling the enablers. Business Process Management Journal, 12(4), 535–552. https://doi.org/10.1108/14637150610678113

- Orazalin, N., & Mahmood, M. (2018). Economic, environmental, and social performance indicators of sustainability reporting: Evidence from the Russian oil and gas industry. Energy Policy, 121, 70–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.06.015

- Parikh, A., Kumari, D., Johann, M., & Mladenović, D. (2023). The impact of environmental, social and governance score on shareholder wealth: A new dimension in investment philosophy. Cleaner and Responsible Consumption, 8, 100101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clrc.2023.100101

- Paul, J., Lim, W. M., O’Cass, A., Hao, A. W., & Bresciani, S. (2021). Scientific procedures and rationales for systematic literature reviews (SPAR‐4‐SLR). International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12695

- Qureshi, M. N., Kumar, D., & Kumar, P. (2008). An integrated model to identify and classify the key criteria and their role in the assessment of 3PL services providers. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 20(2), 227–249. https://doi.org/10.1108/13555850810864579

- Rezaee, Z., & Tuo, L. (2017). Voluntary disclosure of non-financial information and its association with sustainability performance. Advances in Accounting, 39, 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adiac.2017.08.001

- Ronoowah, R. K., & Seetanah, B. (2023). Determinants of corporate governance disclosure: Evidence from an emerging market. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 13(1), 135–166. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAEE-10-2021-0320

- Sakuma-Keck, K., & Hensmans, M. (2013). A motivation puzzle: Can investors change corporate behavior by conforming to ESG pressures? 367–393. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2043-9059(2013)0000005023

- Sarti, S., Darnall, N., & Testa, F. (2018). Market segmentation of consumers based on their actual sustainability and health-related purchases. Journal of Cleaner Production, 192, 270–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.04.188

- Sassen, R., Hinze, A.-K., & Hardeck, I. (2016). Impact of ESG factors on firm risk in Europe. Journal of Business Economics, 86(8), 867–904. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-016-0819-3