Abstract

This article reports on research within multiple case studies of South African Not-for-Profit Organizations (NPO). The study modelled the enabling practices that managers and leaders of these NPOs deem necessary to sustain their service-led organizations in a changing and demanding environment. NPOs face various constraints affecting their survival, including those linked to people and talent, finances, resources, volunteering, and the ever-growing demand for social care. These constraints require managers and leaders of NPOs to identify enabling practices for survival, success, and sustainability. Daily routines in pursuit of strategies demonstrate apex fit-for-practice activities (a concept coined for this study) that include leadership, governance, organizational culture, resources and adaptivity. These activities translate into fit-for-purpose services for the ever-changing needs of beneficiaries. While corporates often focus on excellence and competitive advantage, the NPOs distinguished themselves through adaptable practices that instead met fitness criteria. This approach ensured the survival of NPOs in shrinking resource environments, and the continued service to beneficiaries. These enabling practices contribute to a conceptual model depicting the enablers for long-term survival in the NPO sector, as a novel contribution to the NPO sector, while also theorizing the nexus between fit-for-practice and organizational life cycle.

SUBJECTS:

Introduction

Not-for-profit organizations (NPOs) play an essential role in developing countries amidst widespread recognition that social needs continue to grow. The recent Covid19 pandemic underscored that NPOs are on the frontline of crises to meet community needs, yet they often lack sufficient financial support despite the increased demand for their services (Deitrick et al., Citation2020, p. 1). Grand challenges (Efstathiou, Citation2016; Fielding, Citation2017, Carton et al., Citation2023), such as global pandemics, forcibly remind society of these needs. While governments, and the for-profit sector, play important roles in meeting the needs of the communities, some needs are better met through NPOs (Girei, Citation2023; Wellens & Jegers, Citation2014). Yet, declining funds, exacerbated by grand challenge fallouts, are a situational reality amongst NPOs, jeopardizing their sustainability. Many have dissolved while attempting to meet the much-needed demands in the communities. At the same time, the hyper competition for financial resources, mainly through grants, further complicates the realities faced by these organizations. What this means is that NPOs are not only tasked with meeting ever-increasing service demands in their communities, they simultaneously have to strategize to survive, while also undertaking extensive compliance requirements or changes driven by evolving donor demands (Girei, Citation2023; Lundåsen, Citation2014). There are multi-layered expectations, therefore, from these organizations, which operate with lean staffing and face increased pressure to deliver amidst highly constrained resources (Asogwa et al., Citation2022; Banks et al., Citation2015).

Turning to popular management strategies on how to sustain not-for-profit organizations may have some value. Consulting firms that specialize in turnaround or innovative management practices may also be an option – but in a resource-scarce NPO (Batti, Citation2014), the available resources are most likely directed towards meeting the immediate needs of staff remuneration in order to service the community. Essentially, NPOs present a line of argument that revolves around constant trade-offs, balancing the increasing demands for services against a continuous questioning of the optimal model for survival and growth (Batti, Citation2014; Girei, Citation2023). Our in-depth familiarity with these dilemmas faced by NPOs, coupled with our collective drive to explore real-life accounts of what enables some NPOs to achieve strategic sustainability has prompted this research.

Context informing the current study

Our interest was not to affirm or refute what has already been established in literature in terms of management principles to guide NPOs. From the onset, we accept the universality of management principles and what they may offer NPOs. We believe that management practices need to be subject to re-evaluation prior to their application to the contexts prevailing in NPOs (Hume & Leonard, Citation2014). At the same time, we align with Pfeffer and Salancik (Citation2003) that the behavior of an organization, such as the longstanding NPOs selected in our research, can be understood by interrogating its context. Given all this, we wanted to hear the voices of the actual NPO managers and leaders in order to draw our conclusions by aligning their perspectives with what we know about management principles and practices.

Our research team comprised three qualitative researchers who have intimate knowledge based on experiences in the not-for-profit sector. The main researcher is a qualified physiotherapist with more than 50 years’ experience in management, advising different NPOs, and serving as founder member, volunteer, and executive manager at the Stroke Support Group before retirement. She grew up in a family involved in volunteering, and after retiring continues to volunteer, often serving as a mentor to managers. The second researcher also grew up in a family of volunteers and had daily engagements with NPOs. Additionally, she served as a custodian for a local NPO for several years and provided training to volunteers and workers within a number of NPOs. The third researcher has respectively served on boards and been a staff member of various NPOs, thereafter serving as a funding consultant and mentor for a wide range of local and international NPOs.

Our research efforts were driven by our belief that gaining insights from the implied or tacit knowledge of leaders and managers in longstanding NPOs would provide opportunities to contribute to the body of knowledge on enabling practices for survival. Our view of ‘survival’ was aligned to dimensions of sustainability and adaptability for fit-for-purpose operations, grounded in persistence and persisting, a state of continuing, being resolute or steadfast. Indeed, Sustainability is used in the language, or etymological sense, and refers to an organization’s ability to survive or persist as a quality of NGOs (Banks et al., Citation2015; Batti, Citation2014). Variations of the word are: sustained, sustaining, and survival, which all mean longstanding, or of long duration. We defined ‘longstanding’ in terms of the number of years in operation, and our minimum criteria for selecting NPOs for our research was 30 years. In our study, we also move beyond being fit-for-purpose (i.e. delivering on the much needed social care services) towards a position of what we term, fit-for-practice for long-term survival.

In addition to research on the application of management principles in NPOs, we confirm that research into NPO sustainability is not new (Batti, Citation2014; Hayman, Citation2016; Shava, Citation2019). The novel contribution of our study, however, is the granular lens that exploring daily strategizing opened up so that we could determine which enabling practices could be driven by over-stretched people over an extended period. How did these leaders and managers inhabit their strategy (Williamson, Citation2016) in meaningful ways so that the organization remained relevant, while also surviving during grand challenge times?

Literature review

A wide glimpse at research on NPO sustainability for the last decade identified, amongst others, Montgomery (Citation2015), who asks academics to assist in evidence-based decisions for sustainability strategies. His study focused on long-term sustainability, as in the current study, and looked at the different leadership needed at different stages of the organizational life cycle. Laurett and Ferreira (Citation2018) conducted a systematic literature review on the research dealing with strategies at not-for-profit organizations. The results convey strategy-related themes clustered around strategic management, strategic planning, strategy typology, innovation strategies, and the strategic management of human resources. According to Laurett and Ferreira (Citation2018), the focus of research since 2000 has been on improving the management of not-for-profit organizations. Also, Fonseca et al. (Citation2021) explored management and marketing strategies for survival amongst philharmonic bands as not-for-profit organizations. Fischer et al. (Citation2017) examined a pilot initiative in which philanthropic funders invited and supported not-for-profit organizations in the pursuit of restructuring efforts. Hatcher and Hammond (Citation2018) argued that not-for-profit organizations manage economic development differently than agencies directly controlled by local governments. Denison et al. (Citation2019) examined the extent to which reliance on major revenue sources by not-for-profit organizations affect the magnitude of total revenue volatility. Millesen and Carman (Citation2019) considered capacities in not-for-profit boards. Mason (Citation2020) considered the diversity and inclusion practices amongst not-for-profit associations. More recently, the disruptions in not-for-profit organizations caused by COVID-19 were explored by Newby and Branyon (Citation2021).

Within this journal, we noted that reporting on NPOs is not new. Nkabinde and Mamabolo (Citation2022) explored the strategies of social enterprises to guard against mission drift when faced with tensions from the funders. In 2022, Noori et al. (Citation2022) explored the effect of supply chain integration and challenges on NPO performance using evidence from Afghanistan. Earlier, Maguire and Ntim (Citation2016) evaluated the financial and compliance status of animal welfare NPOs using participants from the Coastal Carolina University in Conway, South Carolina. We believe the prevalence of research interests on NPOs within this journal serves as a catalyst to foster connections between researchers, practitioners and research with societal impact.

When looking at research on NPO sustainability within the South African context, only a few publications were located overall. As referenced earlier, Nkabinde and Mamabolo (Citation2022) analyzed the qualitative experiences of 13 South African social enterprises and presented strategies to prevent mission drift. While Singh and Bodhanya (Citation2014) did not explore the sustainability of NPOs per se, they considered the adoption of systems thinking methodology, known as Systems Dynamics, to examine NPOs. Iwu et al. (Citation2015) investigated the criteria for organizational effectiveness in not-for-profit organizations and used group interviews to obtain data. Their sample was taken from the list of NPOs registered with the Western Cape Government Department of Social Development. Martin-Howard (Citation2019) conducted qualitative case research to explore the barriers and challenges to service delivery and funding at a specific not-for-profit organization in South Africa.

Maboya and McKay (Citation2019) determined the financial conditions NPOs operate under in order to establish the reasons for not-for-profit organization vulnerability. They conducted in-depth interviews with 10 senior managers in the sector and found that donor relations management and finding new or additional donors preoccupy the minds of the not-for-profit organization leaders. Montgomery (Citation2015, pp. 26, 43) found that the sustainability of NPOs depends on their leadership, organizational culture, and decision-making ability. Montgomery (Citation2015, p. 104) focused mainly on leadership and leaders’ abilities and reported that the managers of NPOs in his study needed to know how to maintain sustainability. The Nkabinde and Mamabolo (Citation2022) study found that social enterprises engaged in multiple complementary strategies to manage the tensions between themselves and the funders. The most critical strategy is prioritizing those social impact-oriented projects that enrich their missions. The study also found that by establishing partnerships with funders, social enterprises were able to employ social effectual logic to inform their decision-making. Maboya and McKay (Citation2019) conducted their research by interviewing senior managers to examine the reasons for NPO vulnerability, and based on their findings, presented recommendations for financial resilience. Their research results indicated that SA legislative restrictions made it difficult and expensive to raise funds. These restrictions led to a heavy reliance on donors and resulted in finances becoming the main preoccupation of leadership (Maboya & McKay, Citation2019). Continuing with the sustainability theme, Lettieri et al. (Citation2004) found that the not-for-profit sector needs a strategy to overcome the complexity of its environment and the scarcity of resources. Merk (Citation2014) highlights the need for revision and quick strategy adaptation to survive. Merk’s (Citation2014) study focused on environmental factors, financial stability, and governance on sustainability, and listed 15 leadership attributes required to face the challenges of leading a sustainable organization. These attributes included being inspirational, having a high level of integrity, having deep sector-specific knowledge, strategic thinking, financial acumen, and being a collaborative decision-maker. Further to succession requirements, leaders should possess these attributes and, presumably, have organization-specific knowledge. Viganò and Salustri (Citation2015) researched the interaction between the for-profit sector and the not-for-profit sector (NPOs). They found that, in an economic crisis, the not-for-profit sector was an alternative provider of employment. Breneol et al. (Citation2022) conducted a scoping review to ascertain the translation of health system policies into practice. They identified strategies for adapting and implementing health system guidelines, related barriers and enablers, and indicators of success. Their findings confirm the need for research to strengthen the evidence base for improving the implementation and adaptation of health system guidelines in low-and middle-income countries.

Organizational lifecycle

Given our interest in the longstanding nature of NPOs, we found it appropriate and necessary to include the organizational lifecycle within our research enquiry. Within the organizational context, the organizational lifecycle comprises a set of organizational activities and structures that change over time as an organization grows and matures due to internal and external circumstances. Organizations may revert to previous stages or remain in a particular stage of development of progress towards decline or death. We recognise other researchers who already established the value of using the lifecycle for research on the sustainability of NPOs. For example, Montgomery (Citation2015) proposed using lifecycle stages to guide the leadership required for each stage of NPOs to renew strategy. The introductory phase of an organization would typically involve developing a product or service, and the style associated with this stage is entrepreneurial leadership (Montgomery, Citation2015). After this stage, growth and maturity develop when customers become aware of the product or, in the case of the not-for-profit sector, the service, and choose or need to use it. Additional financing and more services would require a different management and leadership style (Montgomery, Citation2015).

According to Lester, (Citation2004), the organizational life cycle theory was based on growth and maturity. Development depended on leadership and the ability to transform the organization to stay viable. Contributing factors to survival were organizational context, leadership style, and that small organizations are more geared towards sustainability than growth (Lester, Citation2004).

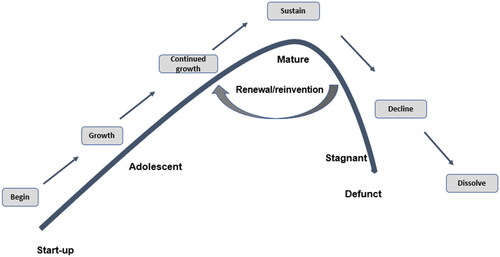

Phelps et al. (Citation2007) found no clarity regarding the number of stages or the exact parameters of each stage. They compared the stages in the content of models and found consistent patterning compared with perceived growth in the different stages and named them start-up, expansion, maturity, diversification, and decline. For our research, the Stevens (Citation2001) version of stages, which she developed for NPOs were used, namely: start-up; adolescent; mature; stagnant; and defunct. Our primary interest lay in NPOs that are in mature and stagnant stages, as we aimed to identify enabling practices that sustain and prevent decline. During these stages, strategic practices should be implemented, and current strategic plans should be evaluated with a focus on renewal and reinvention in order to survive. Renewal would indicate a return, either to enter the growth phase again, or to maintain the mature stage. Also of interest is that different projects may be at different stages of their own life cycles and could impact the survival and sustainability of the NPO in general. We did not aim to compare the organizational lifecycle with that of the for-profit sector. Our aim was to identify enabling practices by the participating organizations to sustain their services.

Research setting

South Africa has a rich history of NPOs that have served communities by offering support, including some NPOs that have been active since the 19th century. Examples of NPOs that may be well-known among a broader audience are, amongst others, the SAVF, which was established in 1904, the Catholic Women’s League, which was established in 1931, the SA Heart and Stroke Foundation, established in 1980, and the Gift of the Givers, which was established in 1992. Within the South African context, NPOs are required to register with the South African Department of Social Development. The SA NPO Act 71 of 1997 (South Africa (SA), Citation1997) governs the registration and governance of NPOs as a trust, company, or association of persons, sometimes called a voluntary organization (VA). Such registration provides the NPO with legitimacy, and allows them to apply for tax and donor exemption status. On 3 October 2019, the NPO Register in the Department of Social Development listed 220,116 registered NPOs in South Africa (Gastrow, Citation2019). By September 2020, 233 180 NPOs were registered with the Department. The annual growth in the number of NPOs may be indicative of increased societal needs for support.

Our focus on the South African context is grounded in our local interests: the increasing demand for social care in a struggling economy with widespread government failure to meet the growing needs of the population and a highly unequal healthcare system. South Africa’s public sector is underfunded, contributing to an inefficent and excessively costly healthcare system (Rensburg, Citation2021). Also, Nkabinde and Mamabolo (Citation2022), confirmed that South African policymakers have not yet developed legal structures for social enterprises, which adds to the challenges faced by South African NPOs.

Research problem, question and exploratory approach

While we acknowledge the growth in NPOs and the increased demands for the services they offer, we also acknowledge that not all NPOs survive in the long-term. What we do not know is how longstanding NPOs have managed to survive while potentially facing the same or similar challenges of those who closed their doors. Put another way, we wanted to hear from the leaders and managers of NPOs that have been in existence for more than 30 years, what they see as the enabling practices that contribute to their sustainability. With our interest in NPO sustainability in general, and our duties as management scholars, we set out to bolster the literature around the embedded, tacit strategic knowledge of the sustainability of NPOs from the viewpoint of their managers and leaders. We also contextually aimed to understand how NPOs cope with and adapt to both external and internal challenges. This includes their ability to remain relevant or fit-for-purpose in the service delivery contexts in which they are situated. We also ultimately aimed to identify what fit-for-practice in the NPO context means. We phrased our research question as: What are the enabling practices of leaders and managers within longstanding NPOs, for survival and sustainability?

We focused on the managers and leaders of five longstanding NPOs since we consider them as people whose practices could be strategic. Further, as scholars of the strategy-as-practice perspective, we set out to determine the what and how of strategy practice, as described in the voices of the selected managers and leaders of the NPOs.

We set out to explore the normal, regular activities and how leaders and managers within the selected not-for-profit organizations responded to required changes while still delivering fit-for-purpose outcomes for governance and service delivery. We believed that a micro-level exploration of the lived realities of leaders and managers in longstanding NPOs would allow us to identify common themes and identify enabling practices and thereby contribute to the body of knowledge on how NPOs are able to remain sustainable. We situated our research within longstanding South African NPOs involved with social care in terms of supporting dimensions of poverty as well as people with mental or physical challenges. Only NPOs which were older than 30 years at the time of the research were incorporated in the research field because we believe that they have a proven history of sustainability or long-term survival and have been subject to changes in legislation during their existence. With a lifespan of at least 30 years, these NPOs may offer rich accounts of how they had to adjust to external and internal challenges. These adaptations may or may not have been connected with complex resourcing areas, such as: governance, staff and finances, legislative rulings, and changes in need of constituents to sustain services.

Conceptual framing

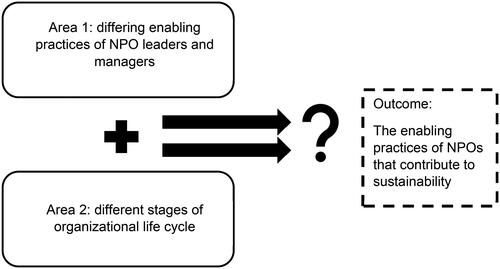

In our attempt to understand the enabling practices of leaders and managers within longstanding NPOs, we framed the study using the following central concepts ().

Area 1 is enabling practices as lived out by the practitioners, and Area 2 addresses the stages of the organizational life cycle. The study sought to discern the strategizing practices that enable survival and sustainability within the organizational life cycle. The question mark was the ‘black box’ of the research in terms of what the enabling practices to achieve sustainability were, and to ultimately show what fit-for-practice entails.

The main stages of interest in the current research therefore included mature-to-stagnant organizations. During these stages, we assumed strategic practices, and evaluation of current strategic plans should take place and be implemented with the view to renewal and reinvention to survive. Renewal would indicate a return to entering the growth phase again or to maintain the mature stage.

Complementary to our bespoke conceptual framework, we also reference the organizational lifecycle framing which we adopted for this study.

We established Area 2 upfront with our sampling of the NPOs as will be discussed below ().

Figure 2. Organizational lifecycle Source: Adapted from Stevens (Citation2001).

Our focus, thus, was on the knowledge and views of the participants as they are practiced in real-world settings following daily routines, which followed their organizational lifecycle stage and which promoted organizational sustainability and survival. We took an active role in defining what practices are enabling and the consequences of the patterns constructed within these practices. We coupled the data to theory. Through telling the story of this 5-year research project, we present the enabling practices and our assertion that NPO sustainability is enhanced through being fit-for purpose and engaging in fit-for-practice activities.

Methods

Our ontological assumption was that the research reality may be studied qualitatively through methodologies that use a situated and subjective stance, as recommended for strategy as practice theorising (Melin et al., Citation2003). Being ontologically open to a subjective standpoint, we took heed of the participants’ voices to complement the tacit and embedded dimensions of our research project.

To answer our research question, as well as to be sensitive to differing lifecycles, we opted for a multiple case study design that allowed us to analyse several sets of data from longstanding NPOs. Stake (Citation1995) indicates that multiple case studies offer the sites the opportunity to learn about differing complexities within a specific sectoral context, in this case, the NPO sector. The adoption of the multiple case design also meant that we were able to compare or dispute findings to uncover attributes or possibilities or to contribute distinctive factors Stake, Citation1995). These attributes were first explored within each participating case organization and then we refined our examination to focus on similar practices and challenges across the selected 5 case organizations. We did not set out to do a comparative case analysis. We felt the multiple case design also enabled data to be examined within each participating case organization and across the selected 5 case organizations. Ultimately, the NPOs that participated in our research were not compared to measure their successes, but similar practices and challenges were identified, and contributing factors were explored.

Sampling strategies: selecting the NPOs to participate in the research

The selected NPOs were recruited from various searches on the web using keywords such as stroke, parkinsonism, or quadriplegia, to search for registered organizations and locate possible participating organizations. Desktop research was conducted to ascertain the establishment dates of the identified NPOs, followed by directly contacting the NPOs to confirm the inclusion criteria and get initial support for their participation. The sampling process to identify the NPOs for participation in the research commenced in 2018 and continued until 2019 when ethical clearance was granted. Ethical clearance for this research was granted by the College of Economic and Management Sciences Ethics Review Committee at the University of South Africa (Ethics Certificate: 2019-CRERC_010 (FA)).

Our inclusion criteria for the NPOs required South African based and registered NPOs; being active for a minimum of 30 years; and being active in the social care sector. Each NPO was considered individually and represented by its leadership, whom we believed influences how the strategy is implemented to best fit the external and internal demands. Each NPO and participant, respectively, provided informed consent for the interviews with two individuals in managerial positions within the NPO. We requested each NPO to give us access to two individuals in managerial positions within the NPO. We required participants who were the executive managers leading the management team on a daily basis, or managers with executive positions in finance, administration, human resources, special projects, or individuals who had previous experience as board members or managers. However, their willingness to participate was possibly the most important criterion, as they contributed their time and knowledge without any obligation.

While the participating organizations had different structures and objectives, all served in social care and were registered with the South Africa Department of Social Development. Such variation within a phenomenon could best be described as stratified, which helps for an in-depth understanding and provides diversity in the research and provides for in-depth explorations of a phenomenon (Hesse-Biber & Leavy, Citation2010, pp. 274–275). Since the organizational leaders, as research participants, were from different levels of management with different service objectives, stratification was easily achieved. The five selected organizations helped produce adequate data to identify structures and patterns of practice within this context (Kleining & Witt, Citation2000). We are convinced that the participation of the five NPOs in our research was adequate, as this amounted to 10 individual interviews.

The participating NPOs

The organizations served different communities and had different structures, which allowed for general and cross-group saturation (Onwuegbuzie et al., Citation2009, p. 6) of the research field. All five organizations opted to stay anonymous. For reporting purposes, we will use descriptive words that align to the core nature of the service offered by the NPOs, i.e. Nursing; Care; Housing; Mental wellness; and Neurological disease.

Within each of the five NPOs, the individual participants were, as targeted in our plan, senior managers, executive managers, and board managers, which aided the diversity of the research field. The participants came from different backgrounds and had different experiences. Interestingly, but not entirely unexpectedly, six of the ten participants were registered social workers. Based on the inclusion criteria of the sample, there was no prerequisite for years of experience. However, all participants had been in their positions for several years, some even for decades. Some of the participants were close to retirement age (i.e. 65).

Data gathering

Semi-structured interviews were best suited to elicit rich descriptions from the participants. We developed a set of interview questions from a pragmatic, grounded objective, keeping the theory of strategy in mind. The semi-structured modality enabled us to be flexible while remaining within the context of the research. We started each interview with a broad question: ‘Why are you successful?’ From here, we reverted to our set of broad questions and asked probing questions, while still allowing them to relate their experiences and express their opinions. The semi-structured interview guide was shared with all participants before the scheduled interview. The first section dealt with the successes of the organization and how these had been achieved. The second section explored the roles of individuals, such as the participants and the staff as a team, their routines and roles, their attributes, and the services rendered. The third section of the interview delved into the participants’ greatest fears, worst experiences, and best achievements. The interviews took place from mid-April 2019 to mid-June 2019 and were conducted at the respective participants’ normal context of practice. All interviews were voice recorded and transcribed. The participants vetted their transcriptions within member-checking criteria, to contribute towards trustworthiness. All the transcripts were found to be agreeable and correct by the individual participants.

The field: contextual details of the NPOs

This section offers contextual background on each of the five participating NPOs. We follow Englander (Citation2019), who posits that qualitative researchers view meaning as context-dependent, with context being more important than sample sizes. As indicated earlier, a descriptor that aligns to the nature of the services offered by each NPO is used. We established upfront the position of each NPO on the organizational lifecycle.

Case organization 1 and interview participants: Nursing (mature)

The NPO was founded in 1987 and remains active in palliative care to patients with progressive and advanced incurable disease. The NPO premises include a palliative terminal care facility, a training centre, offices, and a lucrative thrift shop. The NPO offers support to out-patients by visiting their homes. It also offers support to family members. The NPO extends its reach by offering palliative services in a nearby township. Training in palliative care is offered as an additional service. The NPO relies heavily on volunteers and donations as all services to beneficiaries are offered free of charge. For the most part, this NPO receives 95% of its funding from corporate donors, sponsorships, donations, and income generated by their charity shop.

Interview participant 1 was the executive manager who retired in 2022. Interview participant 2 was a senior manager in the NPO who joined the NPO as a volunteer when a family member needed palliative care offered by the NPO.

Case organization 2 and interview participants: Care (stagnant)

The NPO is a branch of a national organization that has been in operation in South Africa for over 60 years. The NPO offers services that focus on social problems within families, and their main beneficiaries are those within proximity of their offices. Their services also extend to townships. The NPO mostly focusses on child welfare and assists with adoptions, foster care, food parcels, and training. The Department of Social Development offers subsidies that cover a portion of the salaries of the staff.

Interview participant 1 was the director of the NPO and a registered social worker. Interview participant 2 was a senior manager and a social worker. Her main role was to source funding.

Case organization 3 and interview participants: Housing (mature)

The NPO was founded in 1961 and provides residential care for intellectually disabled adults (residents are intellectually compromised and are referred to as ‘villagers’ and need constant supervision from personnel). The NPO also functions as a work facility for these adults, who are involved in tasks such as bulk packaging or creating hand-made gifts. In the housing offered by the NPO, the concept of an extended family is promoted. The facility is situated on a smallholding, far from public transport. For this reason, most of the personnel live on the premises. Housing for residents is run as ‘a home away from home’. Some villagers have lived there for as long as 40 years and are now progressing toward old age and require different care. The NPO also extended its services to a community in a township to provide care to adults living with intellectual disabilities in that community, free of charge. The Department of Social Development offers subsidies that cover a portion of the staff salaries.

Interview participant 1 was the executive manager and a registered social worker. Interview participant 2 was a volunteer who served as a board member and was a parent of one of the residents.

Case organization 4 and interview participants: Mental wellness (mature-to-stagnant)

The NPO offers day care and social support for adult survivors of Acquired Brain Injury in Gauteng Province. The main facilities include areas for group therapy, a therapy gym, individual therapy rooms and administration offices. Volunteers include professionals as well as students from a nearby university who work on a rotational basis and under supervision. Group therapy sessions are facilitated by volunteering professionals and students. Activities and services are provided as part of their treatment. While being a registered NPO, this NPO does not receive a subsidy from the Department of Social Development and is largely dependent on donations. At the time of the interview, this NPO was under severe financial strain. The NPO serves as a training facility for physiotherapy students, and professional involvement translates into recognised Continuing Professional Development points.

Interview participant 1 was the executive manager and a registered social worker. Interview participant 2 was a former board member and mother of one of the injured adults receiving care.

Case organization 5 and interview participants: Neurological disorders (declining)

The NPO is part of a national organization that was established in 1967. The NPO functions independently from its premises on the outskirts of an industrial city. The NPO offers counselling and support, education and awareness as well as residential care for persons who have neurological disorders. Although the beneficiaries are of all ages, the NPO offers full-time housing for some of the adult beneficiaries who function at a high level, needing little supervision. The NPO relies on income generated from their thrift shop and from contracts fulfilled by the workshop on the premises. The shop and workshop are managed by beneficiaries as floor managers since most of them function at a high cognitive level. All beneficiaries need monitoring for their medical condition. Daily medication is controlled from the sickbay by nursing staff on the premises. All board members have been diagnosed with the same neurological condition and function on a high intellectual level. The NPO benefits from marketing and awareness campaigns run by the national association, but it does not receive funding for its operations and services. The Department of Social Development offers subsidies that cover a portion of the salaries of some of the staff.

Interview participant 1 was the executive manager and a registered social worker. Her main functions included financial management and administration. Interview participant 2 was a senior manager and a social worker.

Working within this field, as explained above, we applied the following data analysis strategies.

Data analysis: Data-information-Knowledge-Wisdom (DIKW)

For verification purposes, an independent co-coder was appointed to add a multi-level perspective and legitimacy to the first level of the analysis. Using multiple coders, we opted for open, inductive coding (Lambert & Loiselle, Citation2008). We clustered the codes into themes that established enabling practices of the NPOs. To systematize and manage the process and documents, we used Atlas.ti™. Overall, we aligned our process with that of Carspecken and Dennis (Citation2012) namely, the DIKW model (data, information, knowledge, and wisdom). According to these authors, these four stages are linked to how the human mind makes sense of, or processes data to gain insight and interpretative-constructivism into this concept. We organized the data through clusters of codes and early themes (information) into summative forms by deduction from theoretical points of departure (knowledge) to identify interrelationships towards answering the research questions in the form of findings (Breakwell, Citation2008, p. 347). During the analysis, the aim was to uncover the meanings expressed by participants to retain the essence of their tacit knowledge (wisdom). We wanted to uncover the practices that participants may take for granted or have considered as too mundane to be strategic, and these practices may or may not be strategic in isolation (Jarzabkowski et al., Citation2016). This means that we used ‘wisdom’ to interpret the practices as strategic through our research team’s immersive experience of such practices ‘in-use’ (Feldman, Citation2004; Jarzabkowski, Citation2004; Jarzabkowski & Kaplan, Citation2015).

The ultimate abductive reasoning was from our interpretations (wisdom), guided by literature (knowledge) to ensure credibility (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2017; Mantere, Citation2008). The broad initial findings were confirmed through consensus deliberations amongst ourselves and with the co-coder. These discussions confirmed the essential similarities of codes for verification purposes. As part of using the interpretative-constructivism paradigm, we aimed to identify the enabling practices of longstanding NPOs. We perceived data saturation after interviewing the first three participating organizations and the same answers to the interview questions started to emerge. However, we decided to continue with the interviews to find potential new insights and honour the sample and ethical considerations.

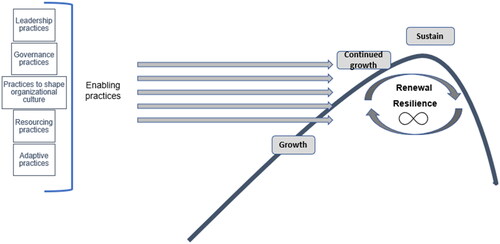

Enabling practices

The organizational life cycle served as a lens to aggregate themes toward assertions that affect renewal by enabling adaptation and development to become resilient fit-for-purpose entities. We grouped the enabling practices around five categories, namely: leadership practices, governance practices, practices to shape organizational culture, resourcing practices, and adaptive practices.

These five categories are not exclusive, but should be seen as interdependent and intricately woven into the fabric of the NPO context. We acknowledge that in this study these categories were identified through our lenses as qualitative researchers. We also include some verbatim quotes from the participants as evidence for our assertions. Further, we position our assertions within existing literature.

Leadership practices

It was clear early on in our research process that the managers of longstanding NPOs in the social services sector engage in strong leadership practices that exemplify values towards social care. It was noteworthy that some of the managers were parents or relatives of beneficiaries of the NPO, which may have added an additional dimension to commitment and interest. The following quote is indicative of the commitment:

Obviously, our patients come first whenever we have to do anything

…The experienced ones [social workers] are okay but it is sometimes still a battle for new or young social workers to follow the process. … how do you remove a child according to the Children’s Act, how to take a child to court, how to place the child in foster care, how to have the order renewed every two years.

As strategy champions, we proffer, based on our data, that the leadership provided a vision and direction and strategized towards inclinations of adapting continuously. Our assertion aligns to that of Veldsman (Citation2019) who confirms the importance of complex leadership practices to influence governance and behavior in the organization, and plays an important role in fit-for-purpose service delivery.

Setting strategic direction translates into strategic objectives. In this particular sector, strategic objectives are achieved by constant re-assessing, deemed to be a strategic practice to maintain service delivery within the available human resource power and financial resources, and this contributed to sustainability (Veldsman, Citation2019). The organizations started with a planned strategy, which needed frequent adjusting, and thus became adaptive.

Based on the dimensions of this theme, leading by example is necessary to establish a culture within the organization, guide renewal practices, and develop and implement strategic practices for survival (see Northouse, Citation2012; Duygulu & Ciraklar, Citation2009). As two of the participants stated:

You do need a special kind of person.

and

We don’t pay much, so commitment is big … it has to be commitment from all our role players. It’s the norm to go above and beyond.

The leadership of both the board and management emerged as important aspects in our research. While leadership and guidance were needed from the board, leading the management team had to do with day-to-day service delivery, and executive leaders guided their respective boards in strategy development. Leadership was found to be interactive, supportive, sympathetic, and steering personnel towards quality service delivery and towards the organization remaining fit-for-purpose. The overriding opinion and finding were that leaders need to be decisive and strong. Leaders also have to be alert to reporting requirements while regularly checking in with the personnel who are directly in touch with the beneficiaries’ needs and requirements.

As an organization we’ve also in the past done a lot of training for time management, stress release, things that specifically we see where there are needs.

In NPOs, leadership has the greatest need to be ‘job-fit’. According to Hailey and James (Citation2004, p. 343), ‘Effective NGO leaders are able to balance a range of competing pressures from different stakeholders in ways that do not compromise their identity and values’. Stakeholders of NPOs comprise partners, professionals, and other personnel, beneficiaries, volunteers, and the public. Leadership must attend to all these stakeholders’ needs, and must balance service delivery with financial uncertainty. Crisis management of customer relationships and beneficiaries is a daily occurrence, and support for problem-solving is part of the daily routine:

Social work is crisis management

Coping practices contribute to the situational knowledge unique to an organization and the individual; as was alluded to by the participants. The participating organizations in the current study acknowledged the development of protocols from experiences to handle situations. At a practical level, individuals within these organizations are the driving force for sustainable development and change (Joseph, Citation2014), which is also applicable to financial procurement and control.

A documented strategic framework [plan] is for a relatively short duration and reviewed annually. However, as the Third Sector is known for crisis management, occurrences in their services result in strategizing often, even daily if the need occurs.

The leadership style was viewed as important, not only as an expression of behavior, but also as an asset. Transformational leadership aims to empower followers (Montgomery, Citation2015; Rothschild, Citation1996), and training is provided to develop the confidence and potential of leaders. The interaction between leadership and team members can be found in frequent meetings and training sessions. NPOs present a special challenge for management, as they have to listen and respond to their operational environment (Fowler, Citation1991, p. 3). This view is supported by Neneh and Vanzyl (Citation2012). They further indicate that an entrepreneurial focus on survival, as highlighted by Montgomery (Citation2015), is important in the first three years of the organization. The dominance of entrepreneurial skills demonstrates leadership traits, such as risk-taking, innovativeness, and resilience. An entrepreneurial leadership style is critical for innovation in an ever-changing environment. For renewal, it could then be regarded that a combination of the transformational leadership that develops personnel, and entrepreneurial leadership styles that develop the organization, would be preferred, in the researcher’s view. The participants regarded constant feedback from the environment and training and re-training as most important in meeting the needs of employees and beneficiaries. Personnel would report situations in which leadership would react appropriately by training and adapting services. Leadership and leading are embedded in leaders’ personalities and commitment to the cause.

Finally, all participating organizations highlighted succession as a concern because most of the executive managers were close to retirement. The stability of leadership was regarded as essential to ensure continuity and develop organizational knowledge.

Governance practices

Within our theming process, we reminded ourselves what governance entails. We referred to the work of Wixley and Everingham (Citation2005) who stated that governance within NPOs combines policies and actual practices; it is achieved through various structures and then functions as a legal entity. According to Brown (Citation2010, p. 33), governance is high-level leadership and focuses on strategy, policy, compliance, and monitoring. Governance monitors financial, human, and organizational resources to enable the purpose and strategic objectives of the organization.

Governance involves monitoring the norms and standards of services regarding professional requirements and adhering to legislation. As a practice, we translate governance into an activity ‘to govern’ or ‘act according to governance principles’. Within the practice of governance, we observed that all participants confirmed that governance is important to manage risks and resources within their available budgets and the need to prioritise accordingly and consider the stage of the life cycle. Governance was identified as the directive operating model for the leadership of the board to manage and monitor strategic objectives within the legislative parameters of the not-for-profit sector (Kantola et al., Citation2016). The literature research underscored the importance of governance as the standard of operations. Participating managers viewed it as important to adapt strategy toward the current needs in the community. They viewed governance as important to manage risks and resources within their available budgets, and to prioritise accordingly and consider the stage of the life cycle. This notion is supported by Braes and Brooks (Citation2011, p. 20) and Merk (Citation2014, pp. 42, 78).

What we found noteworthy is the reference, amongst most of the participants, that the NPO mission is the starting point for sound governance. This aligns with Lynch’s (Citation2006, p. 582) view that a strong sense of mission is needed to connect the purpose and the structure. While the structure of the participating organizations in the current study differed, the analysis indicated similar principles of governance. The efficiency and effectiveness of the governance practices added value and were part of the organizations’ fit-for-purpose practicing. Governance practices of leadership are the enablers of the ultimate objectives of the NPO.

Regular reporting to sponsors and partners is part of NPOs’ constant re-evaluation to ensure continued funding, to comply with legislation, and to determine whether their operations are applicable and viable. To be applicable, the managers indicated that services rendered to beneficiaries were a collection of core services with broad objectives, which allowed adapting to changes. To deliver the original objectives, the organizations maintained and developed the required standard of practice through constant training, developing teams, and recruiting volunteers. All services had a financial implication; hence, the reason to aim for financial independence. The participating organizations aimed to develop alternative sources of income, manage those enterprises, and retain their sponsors with shared objectives.

We are struggling to generate sufficient income to source relevant, capable staff and maintain the campus. Income from fees and [DSD] grant alone is not enough to keep [the NPO] afloat.

Governance was a priority for the leaders, as it forms part of the praxis of leadership. Compliance with the standard of practice and service was a priority, and personnel were trained in the organization’s culture. Their tacit knowledge was further evident in their protocols for challenging situations and when exceptional circumstances developed; leaders drew on previous knowledge to cope.

Practices to shape organizational culture

Managers in the current study strategized for survival through strong organizational cultures expressed through organizational commitment and a willingness to make personal sacrifices. The culture was further guided and demonstrated by leadership, which Siddiqi (Citation2001, p. 21) affirms as necessary. Lok and Crawford (Citation2004) similarly state that organizational commitment depends on innovative and supportive culture, job satisfaction, and a considerate leadership style. In our research, participants indicated that they wanted to work in their particular fields of service. This supports the notion of involvement in charity to support humanitarian causes, either by an individual or an organization, based on an altruistic desire to improve human welfare. The objectives, and overall mandate to offer social services, determined the participating organizations’ culture. Organizational culture is a particular mindset of members of an organization (Brown, Citation2010; Hofstede, Citation1998; Lewis et al., Citation2011). Organizational culture as an enabling practice and driver of value frequently emerged in the current study as a theme.

In general, organizational culture is regarded as emerging from colleagues’ shared belief, their attitudes, values, and norms of behavior, and standard of services delivered (Borgelt, Citation2013). Participating individuals alluded to the fact that they had an organizational culture of commitment, team effort, peer support, and development, culminating in a superior quality of their service. Organizational culture becomes a common outlook on how things are judged and valued on a conscious level.

I’ve seen people come in wheelchairs and drooling … and I’ve thought to myself ‘oh my word, this is awful!’ and I’ve seen them walking out and talking, … obviously they’re never going to be hundred per cent again, but getting out of a wheelchair, walking, talking, making sense – … that is wonderful!

To be part of the organizational culture is to belong and gain a sense of achievement in such an organization. Organizational culture was an intangible aspect evident during all the interviews and visits to the premises. It was found, together with leadership, to support all other aspects of the research and data. Participants expressed their pride in surviving as an organization and being part of the management of their respective NPOs.

Our ‘family’ [personnel] comes first and that is the attitude we carry forward … Attitudes makes the service better. Team effort produces a lot of what we deliver for the community. We’re a tight-knit team.

The entire research field highlighted and demonstrated a specific way of performing their daily and recurring activities, such as training and problem-solving. Aspects of the organizational culture were compassion and attitude towards the beneficiaries (shown as caring) and a determination to maintain service delivery despite the challenges. Problem-solving was part of the organizational culture, which developed in these organizations.

This is a calling … you need to have a passion to drive it … you look at this person as an adult – he’s got beard, he’s old, he’s grey. You’ve told him once or twice or maybe thrice what to do: it doesn’t sink in. So, the staff gets frustrated and they don’t understand, but that’s exactly what we do.

Organizational culture is shaped and affected by the kind of person involved in these organizations over an extended period. In this regard, integrity and honesty are essential, and work together towards the same objective. Each of the participating organizations had a particular service objective, which was dependent on finances, professionalism, and training, among other things. The attainment of objectives in a service organization is largely dependent on the individuals who deliver the services. However, the success of these individuals is influenced by the organizational culture.

There’s no turnover, they absolutely stick to their jobs even though we can’t compare to the Department’s salaries and benefits.

Training for newcomers toward organizational culture needs to be done through explicit instruction. Oftentimes, training is done implicitly for new employees to adapt to the organizational culture (Davies et al., Citation2000). Training is done in the form of workshops, meetings, and seminars. It should aim to modify individuals’ mindsets and implement focused strategies to develop entrepreneurial-like characteristics and ways of strategic decision-making (Neneh & Vanzyl, Citation2012, p. 8341).

We don’t have the benefits like … medical benefit or housing, or a pension fund … but a member of staff returned to work here as she can manage her family before coming to work because of the atmosphere and how we do things.

Resourcing practices

To deliver the original objectives, the organizations maintained and developed the required standard of practice through constant training, developing teams, and recruiting volunteers. For the current study, resources were regarded as those means to aid and support services and provide and build the capacity needed to implement strategic objectives. Financial and human capacities are central to resources in the not-for-profit sector (see Lewis et al., Citation2011). Practices in this section include planning, training, controlling, reviewing, marketing and volunteering. The challenges identified in this research were related to finances and service delivery, especially during personnel shortages. To overcome these challenges, the organizations might ensure an alternate income, and improve training and reporting to partners or sponsors (Khanal, Citation2006). Financial independence and best practice are linked to sustainability, with a balance between resources and objectives. Independence is ensured by strict handling of finances, improved delivery of services, and adequate reporting measures (Khanal, Citation2006). Most of the challenges that emerged in the current study were related to finances, legal issues, and personnel. Financial provision for the services needed is a priority.

At the time of this research, most projects were sponsored by external sources. Managing finances was indicated as essential for financial stability and independence (Montgomery, Citation2015; Merk, Citation2014). Consequently, finances needed to be managed stringently. The manager within the NPO that caters for neurological diseases stated that she taught herself to do regular management and even daily transfer of funds from one section of the business to another as part of her fit-for-purpose management of survival. All the participating organizations emphasised that sponsorships are regarded as important, even small donations. A major concern of the research field was paying salaries, as personnel are key to all service deliveries. All the participating organizations indicated that they never failed to pay salaries. Paying salaries was a high priority part of their culture and responsibility, and their greatest expense to enable services. A concern of leaders was that funders need to realise that salaries are crucial and therefore essential when it comes to funding projects. An important view expressed by several participants was that to address the challenge, the NPO could either become the preferred partner for the for-profit organization, or by adequate reporting for the public sector. Additionally, they suggested that the NPO could focus on serving the partners’ objectives in the for-profit sector where there is competition for funding other NPOs. Financial stability is dependent on the partners, and therefore a culture of reporting strengthens the relationship and mutual trust between the partner and the NPO. Reporting to the Department of Social Development is a legislative matter, and NPOs sign service level agreements for the subsidy of 50% of salaries. This reporting allows the Department of Social Development to determine future planning. Agreements between the NPO and the Department imply an obligation to report according to requirements of the DSD, which might change, often ‘a day or so before the reports need to be submitted’, according to one of the participating executive managers. The following quotes offer a glimpse into the realities of working with the Department.

There’s a lot of pressure from the Department, which is our main financial partner. …you dance the tune they play…

and

The constant issue of funding keeps one from not sleeping at night.

Related to financing is the need for the NPOs to provide an independent income. All the participating organizations acknowledged the importance of creating their own sources of income to make themselves less dependent on donations and partners. To stay appropriate in their service delivery, organizations have to determine continuously, and in conjunction with their partners, what the needs of the beneficiaries are, and to change their strategy or adapt their services accordingly, keeping available resources in mind. In addition to adapting to circumstances, the participating organizations engaged in new ventures and continuously coordinated the activities of their personnel and the processes that they followed to improve and adjust their services. All services had a financial implication; hence, the reason to aim for financial independence. The view of participating organizations was to develop alternative sources of income and manage those enterprises, and to retain their sponsors with shared objectives.

Adaptive practices

Strategy outcomes are mediated by the documented planning and are often adjusted according to the daily changes in circumstances reported by the various role players, which are influenced by internal and external circumstances. The general finding was that strategic formulation was top-down but was influenced by reporting needs from all levels of the organization. Formal planning was generally done for three years because the participating organizations regarded the period as long-term owing to uncertain environments. All the organizations adapted their strategy or service plans annually to prioritise and adapt objectives. Service plans are regularly required for funding from the Department of Social Development as a partner. For the most part, finances and, to a lesser extent, personnel uncertainty, are the main reasons for constant review. This relatively short term may benefit the adapting practices and regularly renew the stage of the organizational life cycle.

It’s much easier for us to manage a three-year plan because sometimes you can’t do things in a year… and you don’t know if you’re going to have money. We do strategic planning for three years and every year as well. … that we do as a work plan, our goals for the year

These adaptive strategic practices focused on internal changes, such as training and providing adequate personnel, driven by the available funding and the needs of the beneficiaries.

Successful organizational strategies consider the needs of all levels of personnel and all governance and operational objectives from the bottom up, rather than enforcing them from the top down (Davies et al., Citation2000). According to Merk (Citation2014), ‘top-down solutions are both ineffective and inefficient’ (p. 4). The strategic frameworks by participating organizations emanated from the board as a guiding and legislative directive, under the guiding influence of management. The development of their strategy is done according to the prescribed legislation and organizational architecture and has to be reported to the Department of Social Development as part of legislative requirements.

Given the complexities in this sector and the various crises that develop, NPO leaders and managers are tasked with strategizing in a messy reality where, for example, the Covid-19 pandemic affected their sponsors, which had direct implications affecting all future strategic planning. Crises can be immediate, unpredictable, and have short- or long-term effects which all require immediate adapting with possible long-term implications. Apart from one participant who said their management is always in crisis mode, all participants confirmed that all kinds of incidents happen incessantly, requiring immediate strategic responses (practices), which affected linear strategic implementation. Continued adapting is in line with our view of non-linear strategic implementation. The sustainability of an organization lies in its performance in response to changes and challenges (Bell et al., Citation2012; Kazlauskienė & Christauskas, Citation2008, p. 23). Scholars confirm that ‘companies are striving to achieve long-term benefit by adopting sustainability activities as core of corporate strategy’ (Goyal et al., Citation2013, p. 362). The practices identified were first measuring outcomes and then adapting services.

We saw that needs of the communities changed, so we changed. When the Department moved into that area, we moved over to another area [township name withheld] where there were no services.

and

Stay focused on what we can do and what we are doing, and don’t make plans for huge things that we can’t do. Focus on doing on what we have to do in this environment

Adaptive practices involve rethinking and relearning when strategy and resources change while keeping the focus on the core vision. The participants indicated that external and internal environments affect the ability and need to adapt.

Some of the adaptive practices for financial stability were evident and altered the structure due to financial strain. Changes were made in service delivery to accommodate changes in external and internal environments.

We all adapt our routines to accommodate what is asked for, what is needed. We are adaptable, and I think change is inevitable

… also important is that we have never changed our core business. We have stuck to our core business.

All NPOs showed the ability to change their objectives and structure, while retaining vision veracity. However, if they face difficulties due to inadequate capacity, they cease operations.

The participating organizations focused on and planned towards future objectives and made plans to improve their financial position. Future planning was regarded as essential, as the beneficiaries’ needs change continuously. Adapting strategic objectives to the needs of people in the environment has a positive influence of renewal on the organizational life cycle, as the adjusting operations prevent projects from stagnating or becoming inappropriate. There were examples of major adapting measures, in agreement with the view that resilience in an organization responds to disruptive events and involves the ability to withstand disjointedness (Burnard & Bhamra, Citation2011). The ability to re-direct and re-assess aids renewal. Objective planning is also important in developing and appointing personnel to enhance the commitment of individuals and strengthen the organizational culture.

Resilience is regarded as an intangible part of an organization. It is influenced by external and internal environments (Willcoxson & Millett, Citation2000, p. 93), intellectual and moral discipline, and training (Hayward & Sparkes, Citation1984, p. 273). Resilience relies on the presence of goals and objectives (vision), decision-making processes, reward systems, and compliance with requirements, such as behavior, communication, and interaction with external elements. Resilience implies adapting to circumstances; it depends on the reaction of personnel, commitment, and leadership. The adapting capabilities, priorities, management styles, and other organizational factors affect both organizational culture and life cycle, and they may change over time (Tam & Gray, Citation2016, p. 18). Resilience as adaptive practice featured strongly in the analysis and will be further discussed as part of extending the organizational life cycle.

We established early on that participating managers agreed that their organizational strategies need to be adapted toward the current needs in the community. Based on our research, we define fit-for-practice as the synergistic collation of the organizational vision or mandate or purpose, the needs in the community it serves, the NPO’s position in the organizational lifecycle, the internal and external variables, and the optimal alignment between the leadership style, the organizational culture, and the activities. Fit-for-practice requires an inherent ability, and a willingness, to adapt to change. Such adapting practices or strategic fit is an operational positioning in accordance with the internal and external environment.

Participants in this research mentioned continuous adapting measures when any aspect of their governance, service delivery, and resources was affected. Willcoxson and Millett (Citation2000, p. 93) also found resilience to be dependent on the reaction to changes in external and internal environments, and on the way humans react during adapting to changes. Adapting was seen by participants as a constant reaction and as part of their organizational culture.

We are struggling to generate sufficient income to source relevant, capable staff and maintain the campus. Income from fees and [DSD] grant alone is not enough…

Organizations in the current study attained resilience by adapting service to reach new goals and objectives through decisively changing direction and altering processes and behavior to align with external requirements. In the same vein, some theorists describe resilience as adapting to circumstances by the positive reaction of personnel, commitment, and leadership (Maull et al., Citation2001, p. 1; Pinho et al., Citation2014). Adapting capabilities and other organizational factors positively affect and alter the organizational life cycle, as endorsed by Tam and Gray (Citation2016, p. 18). Adaptation that results in resilience is essential for survival and sustainability in the service level, as discussed in the section on renewal practices within the organizational life cycle.

Resilience

Although resilience could occur in different stages of the life cycle to sustain services, in this instance of older organizations, the practice was found in the more established phases of the life cycle, reflected as the area above the dotted line in . We present, on a novel level, the stage of resilience with its attendant renewal, as the infinity symbol – ∞ –to indicate a continuous practice of iterating to reassess, retrain and adapt the internal environment to maintain fit-for-purpose around the particular services rendered in the external environment. In this formulation, it is resilience that defines survival or sustainability. Identifying resilience and renewal, at this stage of the lifecycle, while concluding that an integrated system of practices contributes to the survival and sustainability of an organization, are our modest contributions to theory. Resilience comes from adapting to needs, reviewing and renewing services, and even expanding the scope of the NPO to extend the organizational lifecycle in response to societal need.

We conclude that the enabling practices towards NPO sustainability or resilience are situated in fit-for-practice leadership, governance, organizational culture, resources, and adaptability, which ultimately contribute to an extension and a renewal within the organizational lifecycle.

Our findings revealed enabling practices that aid NPO sustainability. Our account of the enabling practices, based on our analysis of data gathered from managers and leaders of longstanding NPOs, provides NPO boards and managers with practical guidance to aid them towards survival. We confirm that there is no one easy answer to sustainability, and accept that NPO sustainability is a complex system of integrated practices and contributions that are aligned to unique contexts. Leaders are the main role player or driving force in the quest for survival. For practices to be enabling, they need to be balanced by the organizational knowledge, the consideration of needs of the communities being served, and the rules that govern operations.

We’re going to stay as we are until we get money for whatever other project we want to do.

Conclusion

This article reported on our research where we explored sustainability from the perspectives of longstanding NPOs. However, it is equally important to explore the flip side of the coin – to understand the factors that contribute to the closure or failure of NPOs. Additionally, the observations and lived experiences of beneficiaries may offer a voice to what they believe NPO sustainability means. A subsequent research phase may involve long-standing NPOs to evaluate the impact of grand challenges and how these NPOs ‘coped’. Furthermore, to enhance leadership theory’s role in creating value, investigating specific leadership styles and individual attributes could offer valuable inputs for succession planning and appointments.

While our approach contributes to the understanding of NPO sustainability, we acknowledge some limitations in our overall approach. The sample size was confined to five willing NPOs providing social care services for at least 30 years. The participants were leaders or managers who were responsible for delivering a service to specific beneficiaries. The study was not extended to NPOs delivering services in other contexts. This restriction was based on the criteria of willing NPOs that met specific conditions and agreed to participate within a defined timeframe. The study adopted enabling strategic practices as its theoretical lens, employing a qualitative approach, and it is important to recognize that alternative theories and methodologies may provide different perspectives.

Our research extended the management theory of enabling practices within the nexus of life cycle stages using South African NPOs associated with social care as the context. Holistically, the research has extended management research through bringing together a confluence of two theoretical, yet also quite pragmatic, perspectives: Strategy as Practice and Organizational Life Cycle. Through identifying a critical strategizing ‘set’ associated with the mature, sustainable stage of the life cycle, management scholars and practitioners gain insights into how a niche public good, in the case of NPOs, may be formulated, practiced and maintained. While this research has focused on the third sector, there is the potential analytical potential to translate these lessons learned to the private sector and identify those applicable strategizing sets that sharpen for-profit sustainable competitive advantage. Through thoughtful disaggregation into the micro strategizing pathways of intent (governance, for instance being broken down into daily oversight mechanisms for accountability, as an example), the five practices could become accessible for strategic formulation and planning providing staff with anchor points for their daily praxis. Furthermore, the practices uncovered show a useful balance between stable or ‘tight’ organizational dimensions alongside the unavoidable but generative ‘loose’ complexity dimensions needed to manage within the current and future global order.

Specifically, having a deeper understanding of these strategizing practices provides knowledge on the leadership qualities needed in the different stages of the organizational lifecycle and, crucially, differentiated the notion of resilience spanning specific stages. Ultimately, such knowledge may be important for survival and NPO capability. Our findings also confirm the assertion of Montgomery (Citation2015) that the sustainability of NPO depends on quality leadership. The current study contrasts with the usual sustainability research, which normally has a financial objective and pertains to the for-profit or environmental sectors. NPO sustainability is informed by enabling practices situated in an inherent ability and willingness to adapt to change as organizations inevitably move through the parallel inevitabilities of time and change. The study has gone some way to opening the ‘black box’ of the research and to elucidate the enabling practices which achieve sustainability, and ultimately show what fit-for-practice entails.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interested is reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ingrid Vorwerk Marren

Ingrid Vorwerk Marren is an independent consultant of Business Management. She has practical experience of management in different settings: physiotherapy departments in state hospitals, a private physiotherapy practice, national professional organizations, and as executive manager of a non-profit organization. Ingrid is registered at The University of Pretoria as a volunteer to mentor students. She is also a volunteer advisor to SMEs in need of strategic guidance. She conducted her research for a PhD at the University of South Africa on survival strategies of non-profitable organizations using the strategy-as-practice perspective.

Annemarie Davis

Annemarie Davis is an associate professor in Strategic Management in the Department of Business Management at the University of South Africa. She conducted her doctoral research on middle managers using the strategy-as-practice perspective. She is a qualitative researcher with a focus on micro-strategizing practices, and favours studies on organizational change and the middle manager context.

Charmaine M. Williamson

Charmaine Williamson is currently an academic advisor to universities around Higher Degrees (PhD and M) candidates in the fields of academic argument, writing, theory, and qualitative methodologies, including facilitating ATLAS.ti support. She has also worked with not-for-profits in terms of good governance and fundraising. She also has an appointment at the Business School of Netherlands in International Management. She is a Research Fellow at the University of South Africa. She has published several peer-reviewed articles/chapters and is an Associate Editor of the International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches.

References

- Asogwa, I. E., Varua, M. E., Datt, R., & Humphreys, P. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on the operations and management of NGOs: Resilience and recommendations. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 31(6), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-12-2021-3090

- Banks, N., Hulme, D., & Edwards, M. (2015). NGOs, states, and donors revisited: Still too close for comfort? World Development, 66, 707–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.09.028

- Batti, R. C. (2014). Challenges facing local NGOs in resource mobilization. Humanities and Social Sciences, 2(3), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.hss.20140203.12

- Bell, J., Soybel, V. E., & Turner, R. M. (2012). Integrating sustainability into corporate DNA. Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance, 23(3), 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcaf.21755

- Borgelt, K. (2013). First and second order leaders and leadership: A new model for understanding the roles and interactions between leaders and managers working in contemporary Australian-based ogranisations undergoing change [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Charles Darwin University.

- Braes, B., & Brooks, D. (2011). Organisational resilience: Understanding and identifying the essential concepts. In M. Guarazio, G. Reniers, C.A. Brebbia, F. Garzia (Eds.), Safety and security engineering IV (pp. 117–128). WIT Press. https://doi.org/10.2495/SAFE110111

- Breakwell, G. M. (Ed.). (2008). Doing social psychology research. John Wiley & Sons.