Abstract

With the presence of negative organizational behaviors, not only is the employee’s productivity and job satisfaction affected, but the entire organizational performance of employees also declines. Workplace ostracism affects employees’ psychological well-being by fostering exhaustion of their emotional, psychological, and material resources, significantly influencing counterproductive work behavior. The present research also addresses the emerging negative workplace behaviors by studying the mediation of transactional and relational psychological contract breaches. The research has adopted a ‘quantitative research design’ followed by a survey approach to collect data from Pakistan’s healthcare sector employees. 420 questionnaires were disbursed among employees, of which 350 were received back, and 332 questionnaires were finalized after data cleaning and screening. Smart-Pls was used to analyze data and assess the association among different variables. Different tests were performed including the descriptive summary, validity (convergent and discriminant), model fitness and path analysis. Results indicated that WOC significantly impacts CWB. RPCB also significantly influences the CWB. TPCB insignificantly effects CWB and WOC significantly influences RPCB and TPCB. Mediation of TPS has been insignificant, whereas the mediation of RPS has resulted as significant. The present research holds considerable theoretical and practical importance as it provides practical insights to the managerial bodies of the healthcare sector in Pakistan to make strategies for vanishing such counterproductive work behaviors of employees that damage the morale and mental peace of other workers. The limitations of this research have also been addressed in the last section.

Impact Statement

This research examined how workplace ostracism leads to counterproductive work behaviors in healthcare employees in Pakistan, mediated by relational and transactional psychological contract breaches. A quantitative survey collected data from 350 employees, with 332 used after screening. Analysis with SmartPLS tested associations between workplace ostracism, contract breaches, and counterproductive behavior. Results showed workplace ostracism significantly impacted counterproductive behavior. Relational contract breach mediated this relationship, while transactional breach did not. The findings contribute theoretically by linking workplace ostracism to counterproductive behaviors through psychological contract violations. Practically, they suggest reducing ostracism and relational contract breaches to curb counterproductive behaviors in healthcare organizations. Limitations include the cross-sectional design and sampling from one sector in one region. Further research could use experimental, longitudinal approaches and more diverse samples. Overall, this highlights the need to address emerging negative behaviors like ostracism to maintain positive psychological contracts and productive work environments.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

Counterproductive work behaviors (CWBs) refer to any action employees engage in to harm their company and company members (Pletzer, Citation2021; Spector & Fox, Citation2002). Examples of such behavior that are identified as counterproductive include sabotage, drug abuse, employee theft, and aggression. On the basis of the nature of such behaviors, it is evident that numerous empirical evidence indicates their negative consequence on the well-being of organizational members (Bowling & Gruys, Citation2010). CWBs are examined as a common workplace deviance that highlights the negative work behavior of employees and becomes a significant cause of disadvantageous effects on individual and organizational outcomes (Kundi & Badar, Citation2021). Counterproductive work behaviors (CWBs) are detrimental to an organization and its members, and includes actions like drug and alcohol abuse, aggression, employee theft and sabotage. Considerable empirical evidence supports the idea that each kind of CWB that is studied has significant negative consequences for supporting organizations. This study diverges from mainstream thinking by studying Workplace Ostracism (WO) as a possible root cause for CWBs specifically in the context of the Health Care sector in Pakistan.

The vast number of empirical studies in existing literature focuses on forecasting of CWBs as a way to examine why individuals are involved in such behaviors and what measures can be taken to mitigate its impact on organizational performance (Kelloway et al., Citation2010), which illustrates the partial explanation of the broad range of organizational behavior (Cohen & Diamant, Citation2019). In this accordance, theory and research mainly focus on the deviation of employees while neglecting the managerial and organizational factors, which is a notable cause of developing CWBs. This study has been conducted to explore workplace ostracism among employees and how it is associated with counterproductive workplace behavior (CWB). WO, marked by exclusion and neglect, is recognized as a potent and distressing phenomenon (Gamian-Wilk & Madeja-Bien, Citation2021).

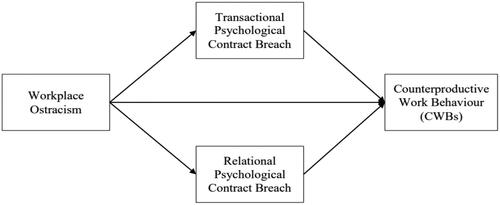

The researcher identified the existing gap and used this opportunity to indicate workplace ostracism as a significant determinant of CWBs, increasing employees’ negative behavior and enhancing their deviant work behavior. The theoretical model of this research paper examines that the impact of WO is likely to increase CWBs in employees, which triggers employees to retaliate. This study has started out by examining the literature on CWBs by looking into the relevant journals and checking to see if any new pieces of empirical or theoretical work have been done in the area. Furthermore, To address this research gap, a theoretical model is proposed, exploring the direct impact of WO on CWBs while considering the mediating role of transactional and relational psychological contract breach. Psychological contract breach (PCB), linked to job insecurity, is investigated as a potential mediator in the association between WO and CWBs, given the fact that psychological contract breach (PCB) partially enhance the job insecurity of employees (Ma et al., Citation2019).

Taking all this together, contributing to existing literature, this research also considers the unique context of the healthcare sector in Pakistan. This study provides a more comprehensive examination of CWBs within the broader healthcare context. The other novel contribution of this paper is the context of the geographical location and sector in which this study is conducted (i.e. the Health care sector of Pakistan), as only one dimension of this sector (nursing staff) has been examined by Attaullah & Afsar (Citation2021). Given the significant threats CWBs pose to organizational performance in the healthcare sector of Pakistan, this study addresses the pressing need for understanding determinants – WO, transactional psychological contract breach, and relational psychological contract breach – that manifest in CWBs.

2. Theoretical framework and hypothesis development

2.1. Workplace ostracism and counterproductive work behavior

Ostracism is the extent to which a person is ostracized or neglected by others in a job or organization (Howard et al., Citation2020). As far as ostracism is concerned, several studies, specifically in sociology, education, and psychology, have discovered that one of the most distinct, powerful, and regular occurrences in human life is ostracism. It is the same as a physical injury as indicated by FMRI (‘Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging’). On the other hand, when people are faced with ostracism it is quite common to say that they experience psychological distress, impaired cognitive function, and becomes aggressive towards others (Mao et al., Citation2018).

However, behavior and workplace ostracism are generally interconnected as they highlight the potential outcomes of ostracism in the workplace (Hitlan & Noel, Citation2009). Withdrawal is a common result of people experiencing ostracism in the workplace. Employees may become demotivated by the lack of interaction and become less engaged in their work and more disengaged from their colleagues. This can also influence the productivity of the organisation. Furthermore, some employees may retaliate or involve themselves in counterproductive behaviors to seek revenge or attention. Besides, job dissatisfaction arises due to ostracism (Yang & Treadway, Citation2018). The individual sense of belonging may erode due to ignorance and exclusion, affecting the work fulfillment targets. CWB can be manifested due to this dissatisfaction as employees tend to express their unhappiness and frustration through it. The norms of equity and fairness usually get violated by ostracism happening at the workplace, and employees do not get the opportunity to participate in social interactions (Gürlek, Citation2021). Negative emotions, resentment, and anger can be fostered by perceived injustice which may fuel CWB.

Employees may engage in acts like theft, sabotage, and spreading rumors in order to retaliate against the individuals when they experience ostracism. Individuals’ self-esteem and social identity get threatened by ostracism. Individuals tend to seek ways in order to restore their worth (Yan et al., Citation2014). Many individuals’ resort to CWB to regain their influence and perceived status by gaining attention and asserting power. Negative behaviors are normalized in an environment where ostracism exists, creating a toxic environment. A cycle of counterproductive actions is perpetuated within organizations through this social influence. Organizations need to foster a respectful and inclusive culture to address workplace ostracism. The likelihood of employees resorting to CWB, and the occurrence of ostracism can be lessened through collaboration, communication, and fairness within organizations.

The Social Exchange Theory suggests that employees with negative experiences of workplace ostracism may engage in counterproductive work behavior as a form of retaliation toward supervisors or participate in another way that they feel evens out the mistreatment received. The Social Exchange Theory assumes that individuals have the tendency to bargain and exchange reciprocities in their work relationship (Stafford & Kuiper, Citation2021). Therefore, negative experiences of ostracism in working environment deviate from threshold of this reciprocity, and may have an impact on counterproductive behaviors in order to regulate the imbalances felt.

H1: Workplace ostracism positively influences counterproductive work behavior.

2.2. Workplace ostracism and transactional psychological contract breach

Ostracism, characterized by exclusion and neglect from the workplace, has significant implications for the employer-employee psychological contract (Ali Awad & Mohamed El Sayed, Citation2023). Specifically, the psychological contract is an exchange process between the employer and employee that includes the employee’s perception of mutual obligations and expectations of the parties involved (Ali, Citation2020). Transactional psychological contract breach capture violations of perceived transactional terms related to rewards, job security and performance feedback. According to studies conducted by Bari et al. (Citation2023), the role of workplace ostracism factors considerably into the correlate of transactional psychological contract breaches. When employees undergo ostracism, they are more prone to an increase in perceive violation of principles of social exchange, leading them to feel an intensification of transactional contract breaches (Kim & Jo, Citation2022). Once employees feel ostracized they are most likely to have emotions of breach transactional promises of fair treatment, recognition, and in terms of psychological rewards (Robinson, Citation2019). Bari et al. (Citation2023) identifies relational ostracism as a cause of a contract breach. When employees see themselves as targets of ostracism, it will be an interpretation of the violation of transactional agreement for fair and equitable treatment by organizational authorities (Robinson, Citation2019). Furthermore, the absence of legitimate explanations or an understanding of the causes of ostracism, also serves to strengthen the link between ostracism and perceived breach of transactional obligations (Gamian-Wilk & Madeja-Bien, Citation2021). The lack of trust and perceived injustice associated with ostracism also links to perceived breach of transactional obligations (Jahanzeb et al., Citation2022). Consistent with the predictions of Social Exchange Theory, this reasoning is based on the belief that workplace ostracism may cause feelings of violated obligations of a transactional nature in the psychological contract. Individuals who experience ostracism may interpret the act of being ignored as a breach of the promises or expectations made within the social exchange in relation to job security, favorable work conditions, and rewards (Qadir et al., Citation2021). According to the principles of social exchange, when individuals perceive obligations in the workplace relationship as having been violated, they may view this violation as a breach of the economic or transactional psychological contract, which has resulted in a failure in the mutually expected reciprocal exchanges (Memon & Ghani, Citation2020). Consequently, the following hypothesis can be formulated:

H2: Workplace ostracism positively influences Transactional psychological contract breach.

2.3. Workplace ostracism and relational psychological contract breach

Relational psychological contract breach specifically, refers to the perceived violation of the socio-emotional aspects of the employment, including trust, support and organizational justice (Tufan & Wendt, Citation2020). The interactive effects of workplace ostracism and relational psychological contract breach must be considered as an important issue to the social exchange process related to psychological contract breach, examining how social exclusion impacts upon wider psychological contract i.e. the nature of exchange between employees and the organization. The correlation between workplace ostracism and relational psychological contract breach is defined by a lot of studies (Bari et al., Citation2023; Chen & Song, Citation2019; Khan et al., Citation2021). According to Zhao et al. (Citation2019), workplace ostracism is associated with relational psychological contract breach, whereby employees that have been ostracized, they will tend to feel there is a breach in the unspoken terms regarding emotional support and interpersonal fairness.

Ostracism is a relational event as it occurs between a perceiver and a target (Pelliccio & Walker, Citation2022). When employees who perceived relational psychological contract breach are ostracized, they interpret the exclusionary behaviors as violative of the mutual understanding about fair treatment, respect and caring (Robinson, Citation2019). The place of emotional trust and security in the workplace can be impaired by the relational aspects of the psychological contract when individuals experience exclusion (Arasli et al., Citation2019). The emotional distress that comes with being ostracized, such as psychological distress and aggression, also contributes to relational misconduct which contributes to the breach (Bhatti et al., Citation2023).

Based on the social exchange theory perspective, it suggests that experiences of workplace ostracism will result in perceptions of relational psychological contract breach. Ones’ experiences workplace of ostracism the psychological contract underpins many of the core principles of social exchange which include trust, support and interpersonal fairness. Thus, this can be hypothesized that:

H3: Workplace ostracism positively influences relational psychological contract breach.

2.4. Transactional psychological contract and counterproductive work behavior

Transactional psychological contract breach refers to the violation from the perception of employees regarding specific employment deal of situational and explicit terms containing structural electronic terms, performance feedback, rewards and job security (Topa et al., Citation2022). There are several empirical studies in multiple frameworks reporting significant positive impact of transactional psychological contract breach on counterproductive work behavior (Bari et al., Citation2022; Ma et al., Citation2019; Protsiuk, Citation2019). When employees perceive a breach in transactional obligations (e.g. unfair treatment, lack of recognition, inadequate rewards), they are likely to enact in counterproductive work behavior in reactive, and sometimes as a coping mechanism (Adekanmbi, Citation2019). Counterproductive work behaviors as the result of a transactional breach lead to feelings of dissatisfaction, frustration and disillusionment by employees (Kim & Jo, Citation2022). These feelings, in turn, provide a vulnerable ground on which counterproductive behaviors begins to emerge. Because individuals perceive a breach in the fair exchange clause in the transactional contract, they will typically proceed to sabotage and/or theft, or in some cases aggression in order to restore, control or influence over their workplace (Low et al., Citation2021). This hypothesis is in agree with Social Exchange Theory that employees who perceived a breach in their transactional obligations such as unfair treatment, lack of recognition, and inadequate rewards may activate their CWB as a response or coping mechanism (Witten, Citation2019). To elaborate this theory, employees in their workplace use to engage their self in a social exchange where they expect for fair and reciprocal treatment (Cross & Dundon, Citation2019). Thus, this can be hypothesized that:

H4: Transactional psychological contract breach positively influences counterproductive work behavior.

2.5. Transactional psychological contract and counterproductive work behaviour

The dynamic interplay between relational psychological contract breach and counterproductive work behavior can provoke interest to explore the socio-emotional aspects of the employment relationship dynamics which influence employee’s action on deviant at workplace (Griep et al., Citation2020). Relational psychological contract breach represents where the employee they feel that their employer has violate socio-emotional aspects of the contract such as for example organizational justice, organizational trust and organizational support (Faruk, Citation2019). An employee who perceives a relational breach in the psychological contract, through the loss of trust, support and fairness, is more likely to respond with counterproductive work behavior, because emotion disturbance is most driven by relational psychological contract breach (Estreder et al., Citation2020). A relational breach in the psychological contract makes an employee feel betrayed, unjustly treated, and emotionally distressed, which is a perfect context for counterproductive behaviour to arise (Gulzar et al., Citation2021). Employee seeking to experience emotional equity are most likely to enact counterproductive work behaviours that include; sabotage, spreading rumours, and interpersonal aggression (Witten, Citation2019).

Furthermore, workplace ostracism to causes people to split the psychological contract that they have created while they were employed there and this breach also won’t allow people to perform their best when it comes to their daily tasks. The relational dynamics that are interrupted by ostracism may further contribute to CWB, but this is another issue that needs to be looked at in the future (Zappalà et al., Citation2022). A breach to the social and emotional aspects at work leads valuable condition to become dissatisfied and to engage in deviant actions (Azeem et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, work place ostracism influenced on counterproductive work behaviour through relational psychological contract breach is a sign of the intricacy of employees’ responses to relational psychological contract breach when social and emotional aspects are violated at work (Coyle-Shapiro et al., Citation2019).

According to the Social Exchange Theory, when employees foresee a violation in socio-emotional psychological contracts such as: trust, support, and fairness, it may produce counterproductive work behavior (Griep et al., Citation2020). Employees are in a reciprocated social exchange in the work place and they may expect to be treated fairly and supported with social contracts (Cross & Dundon, Citation2019). When the emotional reciprocity is violated in the relationship psychological contract, employees may display counterproductive work behavior as an indicator of betrayal, injustice, and resignation in the breach of social and emotional psychological contracts. The social and emotional psychological contract increases the possibility of counterproductive work behavior such as sabotage, rumors, and interpersonal aggression as individuals might try to restore equity of emotional at work (Mapira et al., Citation2023). Thus, this can be hypothesized that:

H5: Relational Psychological Contract breach positively influences counterproductive work behavior.

2.6. Mediation of transactional psychological contract breach

The perceived violation of implicit and explicit promises specifically made between the organization and employees in terms of employment is called a ‘Transactional Psychological Contract Breach.’ It generally occurs when employees cannot fulfill their obligations with respect to their organizations (Agarwal & Gupta, Citation2018). This may involve failure to provide a supportive work environment, career advancement opportunities, or fair compensation. By breaching the relationship between employer and employees, clear conditions appear in terms of CWB. It has been noted that the relationship between ‘workplace ostracism’ and ‘counterproductive behavior’ seems to be mediated and affected by a ‘Transactional psychological contract breach.’ In terms of workplace ostracism, it has been observed that ‘Transactional Psychological Contract Behavior’ acts as a catalyst as it gives rise to CWB (Jafri, Citation2011). Employees tend to involve themselves in such actions as their obligations and expectations fail to be fulfilled by the organizations (Montes & Irving, Citation2008). Employees tend to retaliate and engage in such actions to seek justice and retribution. Also, employees tend to view CWB as their only way to regain power, express their dissatisfaction as well as regain their expectations (Zagenczyk et al., Citation2011). Moreover, increased perceptions of TPCB can be due to ‘Workplace Ostracism’. Employees may perceive this behavior as violence against their fair treatment and expectations due to feeling ignored and excluded.

Furthermore, these feelings of TPCB may exacerbate the negative feelings particularly related to ostracism. It may intensify the likelihood of involving in CWB. TPCB can shape the perceptions of employees. An environment related to negative behaviors gets ignited when employees tend to breach the rules of the environment. In response to ‘WO,’ such behaviors tend to be ignited by the normalization of TPCB (Astrove et al., Citation2015). Transaction psychological contract breach may also negatively impact employees’ commitment. The commitment and loyalty of employees towards their organization get affected due to it. This arises reduced organizational commitment and the possibility of CWB involvement. Employees are normally complemented to play their part in the effectiveness of the organization. The trust between organizations and employees gets undermined due to transactional psychological contract breaches (Atkinson, Citation2007). Employees become willing to engage and cooperate in positive organizational behaviors when employees tend to breach (Chan, Citation2021).

Furthermore, the trust between the organization and employee relationship gets affected, which enhances the likelihood of involving in CWB as a means of self-interest. The negative emotions weaken organizational commitment and get intensified by the perception of TPCB. Thus, organizations need to focus much on positive psychological contracts and mitigate the occurrence of CWB.

Social Exchange Theory is a further reason this study has been brought into light as it out lines that the relationship amid workplace ostracism and counterproductive work behavior is moderated through the means of transactional psychological contract violation. According to the Social Exchange Theory, employees have a cooperative relationship with the organization they are a part of based on equitable treatment and the fulfillment of both implicit and explicit agreements (Paolillo et al., Citation2021). Thus, the mediation effect thus being further discussed is that’s the more the workplace ostracism goes on, the more the employees perceive transaction psychological contract violation, the more negative emotion they will perform and the less commitment they will commit. Thus, it can be hypothesized that:

H6: Transactional psychological contract breach positively mediates between workplace ostracism and counterproductive work behaviour.

2.7. Mediation of relational psychological contract breach

As far as RPCB is concerned, it generally occurs when employees perceive violence in terms of relational obligations. It can be violence in terms of support, trust, respect, or their relationship. However, a breach can occur by violating the relational expectations and undermining the relationship quality between supervisor and subordinate (Bari, Khan, et al., 2023). Many studies have found that RPCB mediates between these factors through the degradation of trust. Employees’ faith in their organization and supervisors is eroded by abusive supervision. As a result, when confronted with workplace ostracism, employees tend to see a breach in their relationship commitments, which may lead to a trust breakdown.

On the other hand, their hostile work environment was formed by a lack of trust, which may lead to employees engaging in CWB. Furthermore, RPCB influences the normative attitudes of employers. Employees typically believe the organization is not meeting their commitments and become involved in various CWB-related activities. However, negative sentiments and distress is generated through RPCB. By comprehending the mediating role of RPCB, organizations can interpret the significance of promoting trust and subordinate relationships (Montes & Irving, Citation2008).

Moreover, a ‘Relational psychological contract breach’ appears to mediate and alter the link between workplace ostracism and unproductive behavior. It has been discovered that ‘Relational Psychological Contract Behaviour’ significantly influences workplace ostracism through giving birth to CWB. However, employees often react and engage in such acts in order to seek justice and revenge (Salazar-Fierro & Bayardo, Citation2015). Furthermore, employees tend to see CWB as their only means of regaining authority, expressing unhappiness, and regaining their expectations. Furthermore, heightened perceptions of RPCB may be linked to ‘Workplace Ostracism.’ When social exclusion occurs to an individual it is no surprise that that individual tends to experience some sort of psychological distress, impaired cognitive function or aggression toward oneself or to others. Thus, RPCB sentiments may enhance negative sensations, particularly those associated with ostracism (Atkinson, Citation2007). It may increase the probability of being involved in CWB. RPCB can affect employee perceptions. When employees violate the environment’s norms, an environment conducive to undesirable behavior is created. RPCB impacts employees’ passion and loyalty to their organization (Aggarwal & Bhargava, Citation2010). This leads to decreased organizational commitment and increases the possibility of involvement in CWB. Employees are typically encouraged to contribute to the organization’s success. Negative emotions undermine organizational commitment and are exacerbated by RPCB perception.

Social Exchange theory can be linked to this relation as a possible theoretical framework. Based on cost-benefit analysis, this theory proposes that individuals tend to engage in social interactions (Li & Yu, Citation2017). Mutual obligations and expectations are outlined by the psychological contracts within an organization, as referred to by this theory (Birtch et al., Citation2016). A positive outcome is observed when these expectations are fulfilled, which fosters commitment, trust, and cooperation. Still, when there is a breach in that psychological contract, an imbalance between these factors is observed, which tends to give rise to negative outcomes and a desire to restore equity (Madden et al., Citation2017). Employees may tend to face isolation and exclusion in this context of workplace ostracism due to a breach of the psychological contract. This is usually observed in terms of fair treatment and social support.

In this perspective, this study proposes Social Exchange Theory as a viable framework for investigating the intervening mechanism, which rests on breach in the relational psychological contract in the mediation between workplace ostracism and counterproductive work behavior. When holding up the causal mechanism of Social Exchange Theory, individuals engage in behavior or engage in relationship within the organization based on underlying condition attributed to psychological contracts that are embedded within the social relationship and interactions (Knapp et al., Citation2020). In light of social exchanges, this can be hypothesized that:

H7: Relational psychological contract breach positively mediates between workplace ostracism and counterproductive work behavior.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and procedure

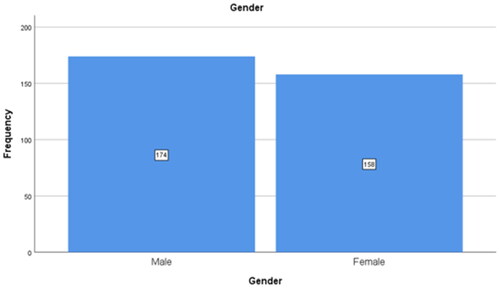

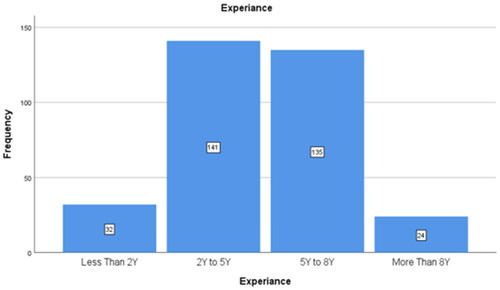

For data collection, we have adopted an online survey research strategy. One of the most common methods of data collection is a survey (Vitrano et al., Citation2021). Corresponding to the research aims and objectives along with the main idea of this study, the employees of healthcare sector were selected as the target audience. Therefore, the respondents of our study’s survey were the health sector employees. The first author of our study took in-charge of the data collection. The author contacted health sector employees via email. He informed them about the study’s purpose and asked them to partake in the survey. It was ensured that we collected the data from the most relevant target population to ensure the validity, authenticity, and quality of the responses. After one week of taking their consent, we sent them an invitation to complete the questionnaire via google forms. The invitation was sent through email to 420 employees. We have completed data collection in a single wave, as our study is cross-sectional. The cross-sectional approach allows us to collect the data in a single unit, saving our cost and time. For data collection, we have adopted a non-probability convenience sampling method. Participation was voluntary, and data was collected from only respondents willing to participate in the study at their convenience. We have received a total of 350 responses; after carefully analysing the collected data, it was found that 18 responses were not according to our criterion; they were either irrelevant or incomplete; thus, we eliminated those responses from further analysis. Hence, we kept a total of 332 authentic and accurate responses. Of these 332 participants, 158 were women, i.e. 47.59%, and 174 were men, i.e. 52.40%. Most respondents had a job experience of 2 to 5 years.

3.2. Questionnaire development and measures

The questionnaire was constructed in three sections. In the first section, a brief research purpose was explained to enhance the clarity and understanding of research purpose. In the second section, the demographics of the respondents were included. It included questions related to the respondent’s gender, working experiences and educational background etc. The third section involved questions related to the items concerning each variable. In this way the questionnaire was designed. To develop an effective questionnaire, we did an extensive literature review. The researcher carefully investigated the sources of item mention in . Before data collection, these questionnaires were adequately tested. Apart from checking the authenticity of the sources of items included in the questionnaire, the questionnaire was re-checked multiple times to ensure its accuracy. Moreover, the inculcation of previously validated scales ensured that the items were pre-tested.

Table 1. Measurement scales.

The study has five observable variables: ‘Workplace Ostracism, Transactional Psychological Contract Breach, Relational Psychological Contract Breach, and Counterproductive Work Behaviour.’ We have adopted a ‘5-point Likert scale which ranged from 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree to 5 = strongly agree’. For the measurement of these constructs, we have adopted scales from past researchers; we adopted these scales because they have been validated and authenticated. The details regarding each variable’s respective item through which these are measured. As the items were taken from the previously validated scales, therefore their validity and reliability were confirmed. The details of the measurement scale, their authors, the number of items, and an exemplary item from each scale are discussed in below:

3.3. Data analysis approach

For data analysis, we have utilized Smart-Pls. We have performed several tests, including descriptive statistics, data normality, validity, and other necessary tests. We have also performed an analysis of outliers and missing values to ensure that there is not any outlier and missing value existing in the data set. We have ensured that the data set is normal and valid. Through Smart-pls we have analyzed the measurement model of the study, and to ensure the validity of the items of the measurement scale, we have also tested the factor analysis test. Then, we conducted an analysis to test the study’s hypotheses to check if the hypotheses were valid and thus accepted or not valid, thus rejected.

Ethical considerations are very critical for performing an effective research study. According to Kaewkungwal & Adams (Citation2019), ethical considerations provide researchers with moral and ethical principles and guidelines regarding the research design and processes. We have followed ethical conduct throughout our study. In this regard, we have followed the following ethical standards and guidelines:

We informed the study’s participants about the purpose of our research

We established the confidentiality of respondents’ personal information

We kept the responses in a secured file

We asked for the respondents’ consent before data collection, and they could quit whenever they wanted to.

We are accountable for our conduct in this study.

3.4. Respondent summary of demographics

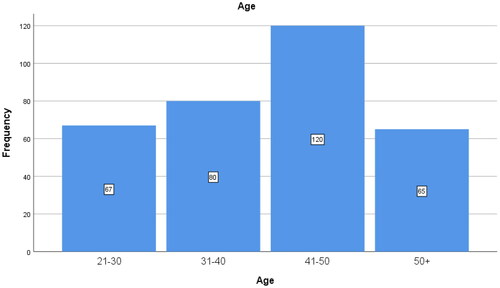

The first step in the data analysis was to assess the demographic traits of the research participants, as the data was gathered from 420 employees in the healthcare sector. After data cleaning and screening, the finalized questionnaires, 332, were analyzed. A fluctuation was observed in their demographic features, such as gender, age, and employees’ working experience, as illustrated in and . There were more male employees as compared to the female employees. Employees with working experience from 2 to 5 years and 5 to 8 years were more than the other categories available in survey forms. Whereas also indicated that the experience of employees was distinct. shows Gender of respondents and frequency. shows experience of respondents and frequency. shows age of respondents and frequency.

4. Analysis

4.1. Descriptive summary

After the demographic analysis, the descriptive analysis was performed to confirm data normality and the non-existence of any missing values or outliers and to ensure the overall accuracy of the data. depicts that against each variable, the cases reported were 332, indicating no missing values in the data. Furthermore, the minimum and maximum values also fall within the Likert scale range, indicating no outliers in the data. The values of skewness also indicated data normality. Therefore, the data was accurate enough to proceed with the analysis.

Table 2. Descriptive summary.

4.2. Reliability analysis

Results of the reliability analysis utilizing internal consistency approach indicated that the measured constructs have the required level of internal consistency (Kawakami et al., Citation2020). shows that the Cronbach’s alpha values of the CWB, RPCB, TPCB, and WOC constructs were above the recommended threshold of 0.7 (Bujang et al., Citation2018), signifying adequacy of the reliability. In addition, the composite reliability values throughout exceeded the acceptable value of 0.7, indicating high internal consistency and reliability of each construct. The AVE values, representing the proportion of variance captured by the latent variables (Hair et al., Citation2021), were within the acceptable range, and all constructs provided the required value, i.e. higher than 0.5. The above results indicate the high reliability of the measurement instruments, hence enhancing the construct credibility and trustworthiness of the study.

Table 3. Reliability analysis.

4.3. Discriminant validity

The demonstration of evidence, for discriminant validity through the correlation matrix, shows that the square root of the AVE is greater than the inter-construct correlations (Kamis et al., Citation2020). This indicates that the measures are demonstrating adequate discriminant validity, as the amount of shared variance among the constructs is less than the variance captured by measures that reflect the constructs.

Table 4. Discriminant Validity.

4.4. VIF

suggests that there is no multicollinearity between the predictors concerning RPCB, TPCB and WOC as the VIF statistics are much less than 5.

Table 5. VIF.

4.5. Factor loadings

shows the results of cross-loading show the items have more correlation with their intended constructs than any other model construct. Each item is effectively capturing the variance associated with its designated latent variable which are substantially above the .50 threshold.

Table 6. Cross loadings.

4.6. R-square

shows that all the exogenous constructs illustrate that nearly 69.8% of variance in CWB is accounted for by RPCB, TPCB and WOC and this reflects good predictive ability of the model to explain the variation in counterproductive work behavior. R-squared of RPCB and TPCB shows 44.5% and 55.3% of variance of is explained by predictor variables in this model.

Table 7. R-square.

4.7. F-square

In the relevance of the exogenous constructs in explaining for the variance of CWB is shown from the F-square results. RPCB indicates that 26.1% of the variance in CWB is accounted for by the exogenous construct RPCB. However, TPCB has F-square value to a level of 2.90, which is within the significant level of 0.01. WOC only has a marginally significant effect at a value of 1.94, which is also within the level of significance at 0.01. The F-square value for TPCB, and WOC in predicting CWB are relatively low with the value 0.002 and 0.3, respectively which suggests that they have relatively low contribution to the variance in CWB. The F-square values have revealed that WOC when predicting RPCB and TPCB are 0.803 and 1.237 relatively which implies WOC has a significant effect on explaining the variances of both.

Table 8. F-square.

4.8. Model fitness

In the model-fit indices suggest a reasonably good fit between the estimated model and the saturated model. Both models demonstrate precisely the same SRMR value indicating strong alignment between the observed covariance matrix and the covariance matrix that the model predicts. d_ULS and d_G values of 2.761 and 0.995 demonstrating a close approximation between the estimated and saturated models. The chi-square values are statistically significant. NFI has a value of 0.719 which implies that the model has a moderate fit. Overall, the model is a goof-fit. shows Model Fittness.

Table 9. Model fitness.

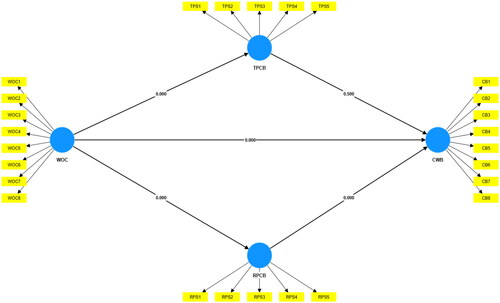

4.9. Hypotheses testing

state hypothesis testing. The direct hypotheses testing results show that for the hypotheses related to the relationships between the constructs are generally supported. For example, the influence of RPCB on CWB with p-value of .000 shows a significant relationship and thus this hypothesis is supported whereas the impact of TPCB on CWB (p-value of .5) demonstrates a non-significant relationship. For the WOC as the predictors of CWB, RPCB and TPCB are 0, suggests that these relationships are highly significant.

Table 10. Hypotheses testing.

shows SEM Model.

4.10. Mediation analysis

In the results of mediation hypotheses of WOC on RPCB and further on CWB has a P-value of 0.000 which indicate the significant effect of mediation thereby supporting the hypothesis. Conversely, the mediation hypothesis involving the TPCB is not supported at the significance level because the p value is .503 which is higher than the 0.05 threshold.

Table 11. Mediation analysis.

5. Discussion

The aim of this research was to assess the role played by workplace ostracism which results in counterproductive work behaviour. For this purpose, the researcher also tested the role played by transactional and relational psychological contract breach. The behavior of employees at the workplace is often affected by how the employee is treated at the workplace. If the employee is treated well and is appreciated, the employee will try to put more effort towards the tasks as a result of that good treatment. But if the employee is not treated well or feels cornered at the workplace, it will start reflecting in their behavior, negatively impacting employees’ productivity (Imran et al., Citation2023). Our study proposed seven hypothesized associations that have been tested through the implementation of statistical techniques. It also proposed that transactional and relational psychological contract breach mediate the relationship between workplace ostracism and counterproductive work behavior.

Our study has identified that workplace ostracism influences the counterproductive work behavior of employees. The reason behind this relationship and influence is very clear. Many studies have reported how workplace ostracism can destroy an employee’s productivity and behavior. Because activities of workplace ostracism harm not only the employee’s mental health but also productivity as the employee feels excluded and cornered from important decisions (Zaman et al., Citation2021). Such activities can provoke the rebellious thoughts of employees most of the time. Many employees feel such things to be unbearable as it harms their self-esteem and self-respect. Especially the feeling of being left out of the important matters of the organization makes a person more rigid (Haldorai et al., Citation2020). Our study suggests that this all ultimately affects the performance and productivity of an employee. It also causes the employee to have a counter behavior which may not seem good to the management.

The study has also tested the relationship between WOC and TPCB which has resulted to be significant. These findings also complement the studies discussed in section 2. This is because when an individual experiences ostracism they feel disconnected from their colleagues and organization (Sabir et al., Citation2024). As a result, their job satisfaction, motivation and commitment also decline (Manninen et al., Citation2023). Consequently, a breach in transactional contract might be observed by such employees due to unfair treatment at workplace.

Our findings have also supported a significant association between WOC and its impact on RPCB. These findings complement the research undertaken by (Bari et al., Citation2023; Nasir et al., Citation2023; Rai & Agarwal, Citation2017). RPCB also resulted to be significantly influence the CWB. These findings support the research findings of (Griep et al., Citation2023; Griep & Vantilborgh, Citation2018; Li & Chen, Citation2018). However, these psychological contract breeches undermine the trust of employees in an organization and negatively influence their performance. Consequently, their willingness to reciprocate with efforts which are beyond their basic job duties is also influenced. Mediation of TPCB resulted to be insignificant between WOC and CWB. But the mediation of RPCB resulted to be significant between WOC and CWB. These findings complement the research of Bari, Khan, et al. (2023). In this way, RPCB serves as a mechanism through which WOC results in CWB.

6. Theoretical implications

There are certain implications of this research study. First, our research study contributes to the existing literature. The reason is the variables used in this study. Few studies discuss workplace ostracism, counterproductive work behavior, transactional psychological contract breach, and relational psychological contract breach. Second, as our study is an empirical study, it also contributes to the empirical evidence. The results of our study can provide more strength to the existing empirical evidence. Third, the current research study provides a very elaborate research framework. It includes information about the relationship between the variables. It provides insight into the propositions that our study has made. It will help understand the relationship between variables. Fourth, our research study provides the empirical results and model. This can help build a theory as it tests the different propositions. Fifth, our research study has used workplace ostracism as the independent variable and counterproductive work behavior as the dependent variable. It means the research study examines the direct relationship between workplace ostracism and counterproductive work behavior. As many studies have not worked on this, discussing these variables can be a great opportunity. Another theoretical implication related to this is the use of transactional psychological contract breach and relational psychological contract breach as the mediating role.

7. Practical implications

Our research study shows a huge impact of workplace ostracism on the counterproductive work behavior of employees. For this reason, the study has certain implications for practice. These implications are towards the sector, organization, managers, and employees. First, there are some great implications for managers as managers are one of the most important people within the organization. It is a fact Leitão et al. (Citation2022) that if managers create such an environment that can appreciate the hard work of the employee or point out the mistake of an employee rather than staking the self-esteem, it will make the employee’s behavior much better. This will benefit not only the employee and manager but also the organization. Second, this study also has implications for the organization. Organizations can have an idea about how much productivity or behavior of the employee can be affected by the ostracism activities of the management. This will help the organization to see how to handle such problems. Third, there are implications of this study for the employees too. The employees are the ones that perform the tasks and report to authorities. If they are not treated well, it will cause an outrage. Employees can have certain ways to handle the situation when there is workplace ostracism. Sometimes reporting to the higher authorities may help. It can help the employees to see how they can withstand such situations. Fourth, it has implications for the healthcare sector and its authorities for considering this situation.

8. Limitations and future research indications

The work done in this research study also has a few limitations which provides a directed way toward future research. First, future researchers should use the time-series data to see if there is any difference in results by collecting data at two different points in time. This is because the current research study has used cross-sectional data, which may cause common method bias. It can also be problematic as such factors might affect the results between two points. Second, the researchers should conduct further studies in developed countries to see how they cope with these issues or how the results change. Our research study was conducted in Pakistan, a developing country and may already have some organizational issues. This study has also used the healthcare sector for this study. Future research should be conducted in other sectors. Third, future researchers should collect data from other populations and may choose a different sampling method. Fourth, the data collection method, such as face-to-face or online interviews, can also be used in future research as the current research study has used a survey questionnaire which might not feel extremely reliable. Similarly, for data analysis, the researchers can use techniques like Regression or Multi-Regression rather than Structural Equation Modeling and AMOS like this study.

For future studies, researchers can use regression as the technique of analysis. They can also use Structural Equation Modeling AMOS. Fifth, the current research has used no moderator in this study. For future research, variables like Al Harbi et al. (Citation2019), leadership, training, etc., can be used as mediating or moderating variables. Similarly, factors such as self-respect and self-esteem Takhsha et al. (Citation2020) can also be used as the dependent variables to see how workplace ostracism can affect employees. Also, the effect of supervision can be seen in the counterproductive work behavior of employees.

9. Conclusion

The current research study presents a framework that discusses the relationship between workplace ostracism and the counterproductive work behavior of employees. This study is conducted in the health sector of Pakistan. It also examined the mediating role of transactional psychological contract breach and relational psychological contract breach. Through the implementation of statistical techniques in accordance with Smart-Pls, the researcher has performed data analysis. Our study shows that workplace ostracism has a great influence on the counterproductive work behavior of employees. RPCB also resulted to be significantly influencing CWB, WOC significantly effects RPCB, WOC also resulted to be significantly affect TPCB. It also proved that a transactional psychological contract breach does not mediate the relationship between workplace ostracism and counterproductive work behavior of the employees. Another relationship being tested in this research paper is whether the relational psychological contract breach mediates the relationship between workplace ostracism and counterproductive work behavior of the employees or not. This proposition is also proved right, which means it mediates the relationship. The study describes how bad the effect of workplace ostracism, such as excluding the employee from important meetings, events, decisions, etc., can be for the employee. It not only affects an employee’s job but also causes the employee to have an outrage and emotional outburst towards others. Such a study provides insight into how workplace ostracism causes counterproductive work behavior in the employees and why employees behave in a certain way after being victims of such a thing. This study has implications for employees, sectors, organizations, and managers to better understand the consequences of not controlling the workplace ostracism activities within the organization.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Muhammad Rizwan Sabir

Muhammad Rizwan Sabir is an PhD Scholar in Business Administration from The Superior University Lahore, Pakistan. His area of interests are human behavior, human resource management and Organizational Behavior. Currently, he is working as Deputy Director in Cybercrime Wing, Federal Investigation Agency (FIA), Pakistan.

Muhammad Bilal Majid

Muhammad Bilal Majid earned his PhD in Business Management from Malaysia. Currently, he is working as an Assistant Professor at The Superior University, Lahore, Pakistan. His area of interest are brand management, consumer psychology. marketing management and general management.

Muhammad Zia Aslam

Muhammad Rizwan Sabir is an PhD Scholar in Business Administration from The Superior University Lahore, Pakistan. His area of interests are human behavior, human resource management and Organizational Behavior. Currently, he is working as Deputy Director in Cybercrime Wing, Federal Investigation Agency (FIA), Pakistan.

Muhammad Zia Aslam earned his PhD in Management from University of Malaya, Malaysia. Currently, he is working as an Assistant Professor at The Superior University, Lahore, Pakistan. His area of interest are general management, organizational behavior and human resource management.

Abdul Rehman

Abdul Rehman earned his PhD in Human Resource Management from UK. Currently, he is serving as an Chairman at The Superior University, Lahore, Pakistan. His area of interest are human resource management, leadership and organizational behavior.

Sumaira Rehman

Sumaira Rehman earned her PhD in Entrepreneurship from UK. Currently, she is serving as an Rector at The Superior University, Lahore, Pakistan. Her area of interest are entrepreneurship, leadership and work force diversity.

References

- Adekanmbi, F. P. (2019). Influence of leadership styles, psychological contract breach and work stress on workplace deviant behaviours. University of Johannesburg.

- Agarwal, U. A., & Gupta, R. K. (2018). Examining the nature and effects of psychological contract: Case study of an Indian organization. Thunderbird International Business Review, 60(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.21870

- Aggarwal, U., & Bhargava, S. (2010). Predictors and outcomes of relational and transactional psychological contract. Psychological Studies, 55(3), 195–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-010-0033-2

- Al Harbi, J. A., Alarifi, S., & Mosbah, A. (2019). Transformation leadership and creativity: Effects of employees pyschological empowerment and intrinsic motivation. Personnel Review, 48(5), 1082–1099. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-11-2017-0354

- Ali Awad, N. H., & Mohamed El Sayed, B. K. (2023). Post COVID-19 workplace ostracism and counterproductive behaviors: Moral leadership. Nursing Ethics, 30(7-8), 990–1002. https://doi.org/10.1177/09697330231169935

- Ali, H. (2020). Mutuality or mutual dependence in the psychological contract: A power perspective. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 42(1), 125–148. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-09-2017-0221

- Arasli, H., Arici, H. E., & Çakmakoğlu Arici, N. (2019). Workplace favouritism, psychological contract violation and turnover intention: Moderating roles of authentic leadership and job insecurity climate. German Journal of Human Resource Management: Zeitschrift Für Personalforschung, 33(3), 197–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/2397002219839896

- Astrove, S. L., Yang, J., Kraimer, M., & Wayne, S. J. (2015). Psychological contract breach and counterproductive work behavior: A moderated mediation model. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2015(1), 11094. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2015.11094abstract

- Atkinson, C. (2007). Trust and the psychological contract. Employee Relations, 29(3), 227–246. https://doi.org/10.1108/01425450710741720

- Attaullah, M., & Afsar, B. (2021). Workplace ostracism and counterproductive work behaviors in the healthcare sector: A moderated mediation analysis of job stress and emotional intelligence. Dynamic Relationships Management Journal, 10(1), 73–92. https://doi.org/10.17708/DRMJ.2021.v10n01a05

- Azeem, M. U., Bajwa, S. U., Shahzad, K., & Aslam, H. (2020). Psychological contract violation and turnover intention: The role of job dissatisfaction and work disengagement. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 42(6), 1291–1308. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-09-2019-0372

- Bari, M. W., Abrar, M., Fanchen, M., & Qurrah-tul-ain. (2022). Employees’ responses to psychological contract breach: The mediating role of organizational cynicism. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 43(2), 810–829. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X20958478

- Bari, M. W., Khan, Q., & Waqas, A. (2023). Person related workplace bullying and knowledge hiding behaviors: Relational psychological contract breach as an underlying mechanism. Journal of Knowledge Management, 27(5), 1299–1318. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-10-2021-0766

- Bennett, R. J., & Robinson, S. L. (2000). Development of a measure of workplace deviance. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 349–360. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.3.349

- Bhatti, S. H., Hussain, M., Santoro, G., & Culasso, F. (2023). The impact of organizational ostracism on knowledge hiding: analysing the sequential mediating role of efficacy needs and psychological distress. Journal of Knowledge Management, 27(2), 485–505. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-03-2021-0223

- Birtch, T. A., Chiang, F. F., & Van Esch, E. (2016). A social exchange theory framework for understanding the job characteristics–job outcomes relationship: the mediating role of psychological contract fulfillment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(11), 1217–1236. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1069752

- Bowling, N. A., & Gruys, M. L. (2010). Overlooked issues in the conceptualization and measurement of counterproductive work behavior. Human Resource Management Review, 20(1), 54–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.03.008

- Bujang, M. A., Omar, E. D., & Baharum, N. A. (2018). A review on sample size determination for Cronbach’s alpha test: a simple guide for researchers. The Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences: MJMS, 25(6), 85–99. https://doi.org/10.21315/mjms2018.25.6.9

- Chan, S. (2021). The interplay between relational and transactional psychological contracts and burnout and engagement. Asia Pacific Management Review, 26(1), 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2020.06.004

- Chen, R., & Song, J. (2019). Effect of workplace ostracism on counterproductive work behavior–-Psychological contract breach as the mediator. UTCC International Journal of Business and Economics (UTCC IJBE), 11(2), 3–23.

- Cohen, A., & Diamant, A. (2019). The role of justice perceptions in determining counterproductive work behaviors. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(20), 2901–2924. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1340321

- Coyle-Shapiro, J. A.-M., Pereira Costa, S., Doden, W., & Chang, C. (2019). Psychological contracts: Past, present, and future. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 6(1), 145–169. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012218-015212

- Cross, C., & Dundon, T. (2019). Social exchange theory, employment relations and human resource management. In Elgar introduction to theories of human resources and employment relations (pp. 264–279). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Estreder, Y., Rigotti, T., Tomás, I., & Ramos, J. (2020). Psychological contract and organizational justice: the role of normative contract. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 42(1), 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-02-2018-0039

- Faruk, S. (2019). The effect of psychological contract, organizational justice and organizational support on psychological contract breach: the mediating effect of trust.

- Ferris, D. L., Brown, D. J., Berry, J. W., & Lian, H. (2008). The development and validation of the Workplace Ostracism Scale. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1348–1366. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012743

- Gamian-Wilk, M., & Madeja-Bien, K. (2021). Ostracism in the workplace. Special Topics and Particular Occupations, Professions and Sectors, 4, 3–32.

- Griep, Y., & Vantilborgh, T. (2018). Let’s get cynical about this! Recursive relationships between psychological contract breach and counterproductive work behaviour. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 91(2), 421–429. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12201

- Griep, Y., Hansen, S. D., & Kraak, J. M. (2023). Perceived identity threat and organizational cynicism in the recursive relationship between psychological contract breach and counterproductive work behavior. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 44(2), 351–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X211070326

- Griep, Y., Vantilborgh, T., & Jones, S. K. (2020). The relationship between psychological contract breach and counterproductive work behavior in social enterprises: Do paid employees and volunteers differ? Economic and Industrial Democracy, 41(3), 727–745. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X17744029

- Gulzar, S., Ayub, N., & Abbas, Z. (2021). Examining the mediating-moderating role of psychological contract breach and abusive supervision on employee well-being in banking sector. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1959007. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1959007

- Gürlek, M. (2021). Workplace ostracism, Syrian migrant workers’ counterproductive work behaviors, and acculturation: Evidence from Turkey. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 46, 336–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.01.012

- Hair, J. F., Jr, Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., Ray, S., Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). Evaluation of reflective measurement models. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: a Workbook, 3, 75–90.

- Haldorai, K., Kim, W. G., Phetvaroon, K., & Li, J. (. (2020). Left out of the office “tribe”: The influence of workplace ostracism on employee work engagement. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(8), 2717–2735. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04-2020-0285

- Hitlan, R. T., & Noel, J. (2009). The influence of workplace exclusion and personality on counterproductive work behaviours: An interactionist perspective. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 18(4), 477–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320903025028

- Howard, M. C., Cogswell, J. E., & Smith, M. B. (2020). The antecedents and outcomes of workplace ostracism: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(6), 577–596. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000453

- Imran, M. K., Fatima, T., Sarwar, A., & Iqbal, S. M. J. (2023). Will I speak up or remain silent? Workplace ostracism and employee performance based on self-control perspective. The Journal of Social Psychology, 163(1), 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2021.1967843

- Jafri, H. (2011). Influence of Psychological Contract Breach on Organizational Commitment. Synergy, 9(2), 311–324.

- Jahanzeb, S., Bouckenooghe, D., & Baig, M. U. A. (2022). Does attachment anxiety accentuate the effect of perceived contract breach on counterproductive work behaviors? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 52(9), 809–822. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12879

- Kaewkungwal, J., & Adams, P. (2019). Ethical consideration of the research proposal and the informed-consent process: An online survey of researchers and ethics committee members in Thailand. Accountability in Research, 26(3), 176–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2019.1608190

- Kamis, A., Saibon, R. A., Yunus, F., Rahim, M. B., Herrera, L. M., & Montenegro, P. (2020). The SmartPLS analyzes approach in validity and reliability of graduate marketability instrument. Social Psychology of Education, 57(8), 987–1001.

- Kawakami, N., Thi Thu Tran, T., Watanabe, K., Imamura, K., Thanh Nguyen, H., Sasaki, N., Kuribayashi, K., Sakuraya, A., Thuy Nguyen, Q., Thi Nguyen, N., Minh Bui, T., Thi Huong Nguyen, G., Minas, H., & Tsutsumi, A. (2020). Internal consistency reliability, construct validity, and item response characteristics of the Kessler 6 scale among hospital nurses in Vietnam. PloS One, 15(5), e0233119. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233119

- Kelloway, E. K., Francis, L., Prosser, M., & Cameron, J. E. (2010). Counterproductive work behavior as protest. Human Resource Management Review, 20(1), 18–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.03.014

- Khan, K., Nazir, T., & Shafi, K. (2021). The effects of perceived narcissistic supervision and workplace bullying on employee silence: The mediating role of psychological contracts violation. Business & Economic Review, 13(2), 87–110. https://doi.org/10.22547/BER/13.2.4

- Kim, S. M., & Jo, S. J. (2022). An examination of the effects of job insecurity on counterproductive work behavior through organizational cynicism: Moderating roles of perceived organizational support and quality of leader-member exchange. Psychological Reports, 00332941221129135, 332941221129135. https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941221129135

- Knapp, J. R., Diehl, M.-R., & Dougan, W. (2020). Towards a social-cognitive theory of multiple psychological contracts. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29(2), 200–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2019.1709538

- Kundi, Y. M., & Badar, K. (2021). Interpersonal conflict and counterproductive work behavior: The moderating roles of emotional intelligence and gender. International Journal of Conflict Management, 32(3), 514–534. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCMA-10-2020-0179

- Leitão, M., Correia, R. J., Teixeira, M. S., & Campos, S. (2022). Effects of leadership and reward systems on employees’ motivation and job satisfaction: An application to the Portuguese textile industry. Journal of Strategy and Management, 15(4), 590–610. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSMA-07-2021-0158

- Li, H.-Y., & Yu, G.-L. (2017). A multilevel examination of high-performance work systems and organizational citizenship behavior: A social exchange theory perspective. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 13(8), 5821–5835. https://doi.org/10.12973/eurasia.2017.01032a

- Li, S., & Chen, Y. (2018). The relationship between psychological contract breach and employees’ counterproductive work behaviors: The mediating effect of organizational cynicism and work alienation. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1273. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01273

- Low, Y. M., Sambasivan, M., & Ho, J. A. (2021). Impact of abusive supervision on counterproductive work behaviors of nurses. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 59(2), 250–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12234

- Ma, B., Liu, S., Lassleben, H., & Ma, G. (2019). The relationships between job insecurity, psychological contract breach and counterproductive workplace behavior: Does employment status matter? Personnel Review, 48(2), 595–610. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-04-2018-0138

- Madden, T. M., Madden, L. T., Strickling, J. A., & Eddleston, K. A. (2017). Psychological contract and social exchange in family firms. International Journal of Management and Enterprise Development, 16(1/2), 109–127. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMED.2017.082543

- Manninen, S. M., Koponen, S., Sinervo, T., & Laulainen, S. (2023). Workplace ostracism in healthcare: Association with job satisfaction, stress, and perceived health. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 1, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15934

- Mao, Y., Liu, Y., Jiang, C., & Zhang, I. D. (2018). Why am I ostracized and how would I react?—A review of workplace ostracism research. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 35, 745–767. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-017-9538-8

- Mapira, N., Mitonga-Monga, J., & Ukpere, W. I. (2023). Counter-productive work behaviors: The right or misguided path? Journal of Namibian Studies: History Politics Culture, 36, 1414–1431.

- Memon, K. R., & Ghani, B. (2020). The relationship between psychological contract and voice behavior—a social exchange perspective. Asian Journal of Business Ethics, 9(2), 257–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-020-00109-4

- Montes, S. D., & Irving, P. G. (2008). Disentangling the effects of promised and delivered inducements: Relational and transactional contract elements and the mediating role of trust. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1367–1381. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012851

- Nasir, S., Nasir, N., Khan, S., Khan, W., & Akyürek, S. S. (2023). Exclusion or insult at the workplace: responses to ostracism through employee’s efficacy and relational needs with psychological capital. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 36. 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-07-2023-0282

- Paolillo, A., Sinval, J., Silva, S. A., & Scuderi, V. E. (2021). The relationship between inclusion climate and voice behaviors beyond social exchange obligation: The role of psychological needs satisfaction. Sustainability, 13(18), 10252. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810252

- Pelliccio, L. J., & Walker, S. (2022). What is an interpersonal ostracism message? Bringing the construct of ostracism into communication studies. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 30(2), 172–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/15456870.2020.1859509

- Pletzer, J. L. (2021). Why older employees engage in less counterproductive work behavior and in more organizational citizenship behavior: Examining the role of the HEXACO personality traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 173, 110550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110550

- Protsiuk, O. (2019). The relationships between psychological contract expectations and counterproductive work behaviors: Employer perception. Central European Management Journal, 27(3), 85–106. https://doi.org/10.7206/cemj.2658-0845.4

- Qadir, M. S., Shah, M. A. A., Ali, M. Z., & Imtiaz, M. H. (2021). The effect of abusive supervision and workplace ostracism on knowledge hiding behavior of the healthcare employees.

- Rai, A., & Agarwal, U. A. (2017). Linking workplace bullying and work engagement: The mediating role of psychological contract violation. South Asian Journal of Human Resources Management, 4(1), 42–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/2322093717704732

- Robinson, C. L. (2019). Justice, peace, and belonging: The effect of negative emotions on distributive justice and ostracism. Seattle Pacific University.

- Sabir, M. R., Majid, D. M. B., Aslam, D. M. Z., Rehman, C. A., & Rehman, P. (2024). Does workplace ostracism lead to counterproductive work behavior in healthcare employees: The role of transactional and relational psychological contract breach. Sumaira, Does Workplace Ostracism Lead to Counterproductive Work Behavior in Healthcare Employees: The Role of Transactional and Relational Psychological Contract Breach.

- Salazar-Fierro, P., & Bayardo, J. M. (2015). Influence of relational psychological contract and affective commitment in the intentions of employee to share tacit knowledge. Open Journal of Business and Management, 03(03), 300–311. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2015.33030

- Spector, P. E., & Fox, S. (2002). An emotion-centered model of voluntary work behavior: Some parallels between counterproductive work behavior and organizational citizenship behavior. Human Resource Management Review, 12(2), 269–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4822(02)00049-9

- Stafford, L., & Kuiper, K. (2021). Social exchange theories: Calculating the rewards and costs of personal relationships. In Engaging theories in interpersonal communication (pp. 379–390). Routledge.

- Takhsha, M., Barahimi, N., Adelpanah, A., & Salehzadeh, R. (2020). The effect of workplace ostracism on knowledge sharing: the mediating role of organization-based self-esteem and organizational silence. Journal of Workplace Learning, 32(6), 417–435. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWL-07-2019-0088

- Topa, G., Aranda-Carmena, M., & De-Maria, B. (2022). Psychological contract breach and outcomes: A systematic review of reviews. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15527. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315527

- Tufan, P., & Wendt, H. (2020). Organizational identification as a mediator for the effects of psychological contract breaches on organizational citizenship behavior: Insights from the perspective of ethnic minority employees. European Management Journal, 38(1), 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2019.07.001

- Vitrano, D., Altarriba, J., & Leblebici-Basar, D. (2021). Revisiting Mednick’s (1962) theory of creativity with a composite measure of creativity: The effect of stimulus type on word association production. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 55(4), 925–936. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.498

- Wang, Y., Li, Z., Wang, Y., & Gao, F. (2017). Psychological contract and turnover intention: The mediating role of organizational commitment. Journal of Human Resource and Sustainability Studies, 05(01), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.4236/jhrss.2017.51003

- Witten, R. (2019). Exploring the role of employee entitlement in counterproductive work behaviour. Stellenbosch University.

- Yan, Y., Zhou, E., Long, L., & Ji, Y. (2014). The influence of workplace ostracism on counterproductive work behavior: The mediating effect of state self-control. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 42(6), 881–890. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2014.42.6.881

- Yang, J., & Treadway, D. C. (2018). A social influence interpretation of workplace ostracism and counterproductive work behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 148(4), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2912-x

- Zagenczyk, T. J., Gibney, R., Few, W. T., & Scott, K. L. (2011). Psychological contracts and organizational identification: The mediating effect of perceived organizational support. Journal of Labor Research, 32(3), 254–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-011-9111-z

- Zaman, U., Nawaz, S., Shafique, O., & Rafique, S. (2021). Making of rebel talent through workplace ostracism: A moderated-mediation model involving emotional intelligence, organizational conflict and knowledge sharing behavior. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1941586. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1941586

- Zappalà, S., Sbaa, M. Y., Kamneva, E. V., Zhigun, L. A., Korobanova, Z. V., & Chub, A. A. (2022). Current approaches, typologies and predictors of deviant work behaviors: A scoping review of reviews. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 674066. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.674066

- Zhao, M., Chen, Z., Glambek, M., & Einarsen, S. V. (2019). Leadership ostracism behaviors from the target’s perspective: A content and behavioral typology model derived from interviews with Chinese employees. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1197. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01197