?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The current study aims to measure the effect of executive managers (EMs) features on the risk-taking level in Jordanian small- and medium-sized service firms. For data analysis purposes, ordinary least squares regression analysis was utilized. We used the screening sample approach. A sample of 72 small- and medium-sized service firms was utilized to collect the data, such as health care, consumer goods, electrical and technology, media and entertainment, and tourism/hotels, noting that these firms were listed on the Amman Stock Exchange/Jordan in the period between 2018 and 2022 using a quantitative method and regression analysis technique. The study used specific features of EMs. We applied the formula 'RISKi,t = β0 + β1GDRi,t t + β2AGE i,t + β3QUAL i,t + β4EXPi,t + β5OWN i,t + β6DUAL i,t + β7TENRi,t + β8ROA i,t + β9BMV i,t + β10SIZE i,t + β11LEV i,t + β12LIQi,t + β13 R&D i,t + ε………(1)'. To measure the risk-taking degree in SME service firms, the return on assets (ROA) standard deviation (SD) coefficient was utilized using the Pearson correlation coefficient among all the study variables. The results conveyed that there is a substantial negative association between experience, ownership, risk-taking, and the qualifications of EMs. Moreover, the EM's tenure and the service firms' degree of risk-taking were proven to have a significant positive relationship. Finally, gender, age, the duality of EMs, and risk-taking degree were deemed unrelated.

1. Introduction

The method of establishing and defining business strategies, as well as their aspects, which would influence the firm's interaction with the dynamic and volatile settings in which it works, has been demonstrated by several prior studies in the literature (e.g. Gupta et al., Citation2022; Loukil & Yousfi, Citation2022; Yousfi et al., Citation2022). The participation of executive managers (EMs) in this process is significant and effective. It has only examined how EMs affects risk in a small number of research (Atayah et al., Citation2022; Gengatharan et al., Citation2020; Martino et al., Citation2020). According to Loukil and Yousfi (Citation2022), for instance, EMs with strong attributes and management philosophies are more likely to adjust to emerging market shifts in developed nations than in developing ones. This implies that EMs in developed nations are more likely to embrace and invest in proactive, riskier initiatives inside their companies. Benischke et al. (Citation2019) looked at the link between diversity and the power characteristics of EMs, whereas Bouslah et al. (Citation2018) underlined that EMs' power features are important and based on their risk options: if they lean toward risk-averseness (i.e. risk-takers), this indicates that they favor regular and conventional projects (i.e. risky yet innovative). Additionally, they provide evidence that EMs with unique management style attributes mediate the relationship between EMs' risk-taking behaviors and remuneration in emerging markets; in contrast, Sunder et al. (Citation2017) noted that EMs who successfully embrace innovations would possess certain attributes, such as being more effective, open-minded to embracing new ideas in their organizations, and investing more in R&D in firms located in emerging markets.

According to recent research conducted by Atayah et al. (Citation2022), EMs with longer experience tend to be fewer risk-takers, less risk-averse strategists, and less risk-averse decision-makers than non-tenured professionals in emerging markets. Meanwhile, Martino et al. (Citation2020) noted that some characteristics of EMs, such as a high degree of schooling and a lengthy career horizon, are important predictors of risk-taking in emerging markets greater than in developed markets. Therefore, these studies provided evidence and suggested that EM profiles might influence risk-taking; in contrast, a very small number of studies examined the influence of EM traits on a firm's risk-taking in emerging markets. The influence of EM demographic traits on business risk-taking in Chinese initial public offerings (IPOs) was highlighted by Farag and Mallin (Citation2018). Their research demonstrated that EMs who are younger, have shorter tenure, and have had excellent education are more likely to take risks in their organizations. In addition, their study revealed that few female EMs are risk-adverse. Additionally, Gupta et al. (Citation2022) noted that EMs with incentive programs in place for Chinese SMEs would see a rise in their companies' innovation initiatives as well as activities like R&D spending, innovation performance, and sales of new products. On the other hand, EMs with advanced degrees and strong political relationships boost their companies' innovation efforts and growth-oriented projects in emerging markets. To assist the board of directors and shareholders in assigning and choosing the best EMs for their companies, the goal of this study is to determine the risk profile of EMs.

This study, in contrast to other research, examines the impact of EMs' characteristics, namely their age, gender, experience, ownership, dual nature, and tenure, on their willingness to take financial and strategic risks in emerging markets. The majority of earlier research on risk-taking in the literature has chosen to evaluate risk-taking from a financial or strategic perspective (e.g. Loukil & Yousfi, Citation2022; Martino et al., Citation2020, Benischke et al., Citation2019) in developed countries, while this study was conducted on Jordan as developing and emerging market. Nonetheless, March and Shapira's (Citation1987) investigation demonstrated a strong correlation between EM traits and risk-taking. Research by Lipson et al. (Citation2009) and Berk et al. (Citation1999) indicates that high growth prospects are positively correlated with low risks in emerging markets; however, Bhagat and Welch's (Citation1995) study notes that innovation initiatives exhibit a significant degree of result uncertainty.

Based on the data we have, this study is regarded as essential in addressing the issue of how EM traits affect the risk-taking of SM service firms in emerging markets. It is carried out on publicly traded firms in Jordan, a growing and emerging nation. This analysis uses a broader variety of risk-taking proxies than the study by Martino et al. (Citation2020), which focused on performance variability, namely the standard deviation of Tobin's Q, as a proxy for the firm's risk-taking. Consistent with the research conducted by Benischke et al. (Citation2019), this investigation aims to differentiate risk-taking choices about finance, investment prospects, and company expansion in emerging markets. We gathered EM features between 2018 and 2022 since the study's sample includes EMs' features across a longer time than Benischke et al. (Citation2019) do, which is thought to be useful information about them. Yes, a great deal of earlier research. Additionally, several earlier studies, including those by Yousfi et al. (Citation2022), Loukil and Yousfi (Citation2022), and Attia et al. (Citation2020), showed that over 50% of the companies listed on the SBF120 index had dualities in their organizational structures and violated the NRE legislation. The introduction of the Cop'e-Zimmermann law in 2011 sometimes referred to as the French gender quota law, increased pressure on listed companies to diversify their top-level management roles, according to research by Loukil and Yousfi (Citation2022). Thus, from 2001 to 2013, less than 0.3% of SBF120 EMs were female, a result of the growing number of female EMs nominated to the board of directors. Since Martino et al. (Citation2020) limited their investigation to family-controlled businesses in Italy; we chose to do a more thorough analysis of family businesses, which are common in both nations, to clarify their unique characteristics. To put it briefly, the EM profiles are not always diverse because they might come from the same social networks and have many of the same characteristics. The EMs are not believed to pose a serious threat to the company, especially when it comes to taking strategic risks, as they typically appear to be friends with or former board members. Finally, yet importantly, La Porta et al. (Citation2002) noted that a large number of French businesses rely on highly concentrated ownership with several identity owners. In the majority of these businesses, there is a single owner who has the majority stake and may act opportunistically at the expense of the minority shareholders, which might raise risk-taking to an extreme degree. In this study, we adopted the Bsoul et al. (Citation2022) model but focused on and conducted only on the SME service firms in Jordan as an emerging economy to collect accurate information in only one sector rather than using both sectors as done by Bsoul et al. study.

Thus, this research adds to the body of knowledge by examining the connection between the demographics of the EM and SM service firms' willingness to take chances in emerging markets. This study is considered as beneficial to shareholders, who are always looking for suitable chief executive officers to choose from, especially those who are highly skilled and informed in service organizations in Jordan, a developing nation. Therefore, they are making use of their riches and improving Jordan's place in the international economy. The present study centers on the significance of EMs' features (i.e. gender, age, qualifications, etc.) influence on small and medium-sized service firms' risk-taking using multiple factors as control variables in Jordan as an emerging market. Thus, this study aims to close several research gaps, as demonstrated in the following points:

The assessment of business and management literature did not address the main parts of the research that are unique to the peculiarities of EMs (gender, age, credentials, etc.) effect on the risk-taking of small and medium-sized service enterprises in Jordan, an emerging country.

Very few studies have been applied to emerging nations; the majority of studies on this topic has been conducted in developed nations and focused on manufacturing firms rather than service.

While most of the earlier studies did not employ multiple factors as control variables, some of them thought that the features of EMs (i.e. gender, age, credentials, etc.) were a benefit and a formula that, if applied, may have a beneficial influence on small and medium-sized service enterprises' risk-taking in Jordan as an emerging market. Furthermore, using them in one model to include some control variables has not been the subject of much research.

The present study was built upon the subsequent components: The literature is included in Section 2, the study technique is shown in Section 3, and the data collection process is analyzed in Section 4. The study's limits, results, and suggestions are finally presented in Section 5.

2. Literature review

2.1. Adoption of trait theory

Gordon Allport was an early pioneer in the study of traits. This early work was viewed as the beginning of the modern psychological study of personality. The trait theory of personality proposes that people have specific and distinguished features and traits, and it will strengthen and intensify those traits that account for personality differences. Therefore, the trait approach is considered one of the main theories to explore and study personality. Trait theory proposes that individual personalities are a compound of broad dispositions (Fajkowska & Kreitler, Citation2018). Thus, a feature in a personality is considered a feature that meets three criteria: it should be consistent, stable, and vary from one person to another. Based on this definition, an EM feature can be thought of as a relatively stable feature that causes EMs to behave in certain ways in emerging markets (Worthy et al., Citation2020). In the literature, there are four trait theories of personality as follows: Allport's trait theory, Cattell's 16-factor personality model, Eysenck's three-dimensional model, and the five-factor model of personality. In this study, we will focus only on seven factors Ems's gender, age, expertise and experience, ownership, duality, and tenure are independent variables, while, the dependent variable will be risk-taking, which includes the standard deviation of the firm's return on asset ratio (ROA). There is a consensus among most theorists and psychologists that most people can be described based on their personality traits. Still, there are many theorists, who continue to debate the number of specific and basic traits that formulate human personality. While trait theory has an objectivity that some personality theories lack (such as Freud's psychoanalytic theory), it also has weaknesses. There are many common criticisms of trait theory that focus on the fact that traits are often poor predictors of behavior. It might be found that some individuals have high scores on some specific assessments for some specific traits, which means that some of them may not always behave that way in every situation. Additionally, trait theories do not address how or why individual personality differences develop or emerge in emerging markets.

2.2 Theoretical perspectives

This study's discussion about the relationship between EM features in small and medium service firms in emerging markets and risk-taking will be based on three theoretical viewpoints. This includes the upper echelons theory, which proposes that directors' features, standards, and specialized background affect their views and, consequently, their own judgments (Farag & Mallin, Citation2018; Sanders & Hambrick, Citation2007). In addition, their social, psychological, and behavioral features and traits (Attia et al., Citation2020; Yusuf et al., Citation2022) mainly influence the decisions they make. Similarly, this theory assures that the rationality of EMs toward decision-making is controlled by their cognition. Accordingly, based on the background features of the EMs, some of the long-term choices along with the level of performance can be predicted in emerging markets (Zhang & Rajagopalan, Citation2010). Additionally, prior research has depended on this theory in examining the relationship between EM features and other aspects related to decision-making in emerging markets. These include but are not limited to risk-taking (Gala & Kashmiri, Citation2022), research and development (R and D) spending (Vo et al., Citation2021), firm takeover (Li & Tang, Citation2010); innovation (Chen & Zheng, Citation2014); financial disclosure (Herrmann & Datta, Citation2006), and the behavior of cash holdings (Huang, Citation2013).

Second, the 'resource dependence theory' (RDT) indicates that having board members with diverse skills and knowledge aids in increasing firms' legitimacy and access to resources and experience (Pfeffer & Salancik, Citation1978). Thus, the researchers propose that various EM features (i.e. age and education) can help in forming diverse backgrounds for boards. To further explain, having female EMs as members of the board offer diverse resources and knowledge for the firm overall benefit (Barker & Mueller, Citation2002).

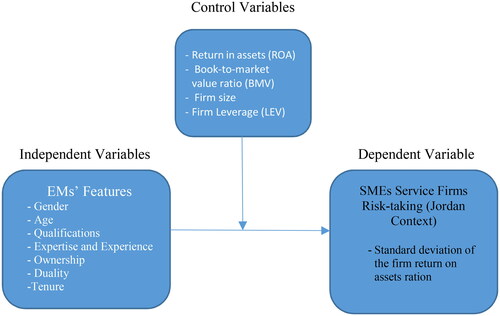

Third, based on the 'human skills and capital' theoretical point of view, an individual's experience, knowledge, education, and skills, is a vital factor in forming his/her perceptions and level of productivity. Hence, this affects the firm's overall performance in emerging markets (Devarajan et al., Citation2022). Consequently, having diverse human capital of diverse backgrounds and knowledge means having different experiences on a particular board of directors (Vo et al., Citation2021). Similarly, according to Yousfi et al. (Citation2022), having heterogeneous boards is much better than having homogeneous ones in terms of performance. An example is having a female board of director members since they have different perceptions than males. Hence, Farag and Mallin (Citation2018) ensure that heterogeneous boards display higher quality of management and the ability to overcome challenges imposed by the external environment in emerging markets. shows the conceptual framework with all the mentioned variables used in this study. , which illustrates the survey's information that includes all variables/dimensions, reliability values, no of questions, sources, and abbreviations.

Table 1. Illustrates the survey's information that includes all variables/dimensions, reliability values, #. of questions, sources, and abbreviations. (Source: Authors' own work).

2.3. EMs' demographic features and service firms' risk-taking

The level of competitiveness displayed by a company or organization is a result of various decisions made by those who are responsible in emerging markets. Most of them are by EMs. Moreover, in a highly dynamic and competitive environment, managers have to make risky decisions in order to survive or maximize performance in emerging markets (Hoskisson et al., Citation2017). According to the upper-echelon theory, such decisions made by EMs have to be socially and psychologically based on the features of EMs. Furthermore, prior research has attempted to examine the relationship between EM features and demographic features and taking risks. Among those features that were examined were age, education, gender, tenure, duality, ownership, and professional experience.

2.3.1. EMs gender

To discuss this further from the resource dependence theoretical point of view, having female directors in the board presents diverse perceptions and backgrounds. Despite contributing to 39% of the global workforce, because of a study conducted in 2021 by the World Bank, it is rarely that we find females gaining leadership positions in emerging markets. Likewise, Forbes mentioned that by 2021, 8% of women would lead the world's largest 500 businesses, while men hold top positions being the majority (Ghazi, Citation2022).

Noting that the percentage of female directors is much less than the males, many previous studies have attempted to measure the extent and willingness to risk-taking of female directors in comparison with males in emerging markets. Portrayed by Muhammad et al. (Citation2022) study where they studied one-hundred and ninety two non-financial publicly traded Italian enterprises during the time period between 2014 and 2018 as a sample. As they studied the moderating effect of board gender diversity on the association among firm governance features (i.e. the board size, EMs gender, board independence, ownership concentration, and EMs duality) and firm risk-taking in emerging markets. The results indicated that female executives are less willing to take-risks than male executives are in emerging markets. Similarly, a study by Vo et al. (Citation2021) based in Vietnam examined the impact of EMs gender on risk and performance in emerging markets. Where they took all publicly traded firms listed on Vietnam's two stock exchanges as a sample of the study, during the time from 2007 to 2015. Their study concluded that men have more confidence than women do, therefore, firms led by female directors' face less idiosyncratic and systemic risks. Moreover, they concluded that female EMs achieve higher profitability than male EMs, as female EMs bring more value to the organizations due to their unique perspectives and workstyles in emerging markets. However, other studies have an opposing view. Where a study incorporating a sample of eight-hundred and ninety two initial public offering (IPOs) listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges by Saeed and Ziaulhaq (Citation2019), has attempted to measure the impact of gender on taking risks. This study found female EMs have great towards risk-taking and are not afraid to do so. Yet, other studies found no significant correlation between gender and taking risks. An example is Aabo and Eriksen (Citation2018) study, which incorporated 475 US manufacturing firms as a sample during the time from 2010 to 2014. Finally, Faccio et al. (Citation2016) attempted to study the same correlation during the time period between 1999 and2009 through taking 132,590 firms from 41 Amadeus countries as a sample. Where they found that gender has an influence on risk-taking as they suggested that female EMs are keen to preserve their positions, therefore they avoid risk. Hence, their firms can experience lower leverage ratios and less volatile earnings.

2.3.2. EMs age

The correlation between EMs gender, qualities, and risk taking has been the center of attention of prior research. For example, younger EMs are characterized by being less experienced and knowledgeable, hence they focus on growth through taking riskier endeavors in emerging markets (Bertrand & Schoar, Citation2003). In addition, they make riskier decisions in order to strive their brands' positions in the firm. In contrast, older EMs are seen as more traditional in taking decisions and their management style in general, hence their risk-taking is lower (Hambrick & Mason, Citation1984). Despite this, the linkage between EMs gender and willingness to take risks produced conflicting results among researches. Where Loukil and Yousfi (Citation2022) has studied this relationship among non-financial firms that are listed on Singapore's SBF120 index during the time period between 2001 and 2013. The study found through utilizing the business leverage ratio that a relationship between the variables exists, due to the reason that the sample EMs were more inclined to indebt firms, which can be related to their age being possibly in their 40s or 55 years old on average.

In a study in Malaysia in the time period between 2009 and 2017, utilizing 6169 publicly traded companies as a sample, by Yeoh and Hooy (Citation2020). They found that family businesses EMs have higher willingness to take risks while they are still young, or in their 60s. However, those same EMs have less willingness to take risks concerning investment when in their 40s.

However, a study by Ferris et al. (Citation2019) showed that there is a negative linkage between EM's age and firms' willingness to rake risks, they examined a sample of 12,000 during the time period between 1999 and 2012. Yet, a study in China by Alqatamin et al. (Citation2017) suggested that younger EMs are more of risk takers than senior ones. Whereas, Muhammad et al. (Citation2022) study found a significant positive correlation between EMs age and financial risk-taking in emerging markets. Yet, Devarajan et al. (Citation2022) study in the United States found no correlation between EMs age and firm risk-taking.

2.3.3. EMs qualifications

The level of education of EMs has an effect on numerous ideas, viewpoints, and specialized advancements in a firm, its board, and choices in emerging markets (Anderson et al., Citation2011). A great number of prior research (e.g. Li et al., Citation2018; Qawasmeh & Azzam, Citation2020; Saeed & Ziaulhaq, Citation2019) suggested that highly educated EMs are more capable of dealing with new technology and ideology in addition to comprehending complex challenges and situations. Hence, they look for innovative businesses and investment opportunities, which are characterized with being open for development opportunities in emerging markets. Yet, the results about this topic are highly conflicting. Furthermore, Martino et al. (Citation2020) showed in their study results from a sample of 107 Italian family businesses listed on the Milan Stock Exchange. Where they studied the effects of EM features on the long-term risk-taking. They also demonstrated that the level of professional education that an EM has is negatively strongly associated with SME service firms' risk-taking. Which are results that Farag and Mallin's (Citation2018) disagree with, as they concluded that, a strong and positive link between EMs education and firm risk-taking exists, taking China as the case. On the other hand, EMs level of education is positively correlated with the capacity of family businesses to internationalize (Ramón-Llorens et al., Citation2017). Their results were based on research done during the time period of February and March 2011, where they took a sample of 187 Spanish family-owned firms. Finally, according to Loukil and Yousfi's (Citation2022), they found no connection between risk-taking and an EM's educational background. Thus, they suggested that postgraduate EMs educational level has minor effect on the volatility of stock returns.

2.3.4. EM expertise and experience

According to Loukil and Yousfi (Citation2022) study, EMs who have prior experience (in years), since they are more open-minded, like challenges, and support innovation, they will be more likely to make hazardous decisions and ideas in emerging markets. They are also excellent at handling novel and dangerous concepts. Furthermore, Herrmann and Datta (Citation2006) study assured that the EM's experience (in years) act as a reliable indicator of the EM's knowledge, values, and skills as well as a useful example of the EM's activities and strategic choices in emerging markets. Thus, the more experienced EMs are for working for other organizations, the more inclined they are to make decisions from a more general perspective (Zhang & Rajagopalan, Citation2010).

Similarly, Orens and Reheul (Citation2013) concluded in their analysis that firms with EMs who have past work experience (in years) tended to have lower leverage ratios, meaning they experienced less risks in emerging markets. Yet, Martino et al. (Citation2020) study assured that EMs of Italian family enterprises to risk-taking cannot be connected to their level of past experience (in years). Furthermore, Farag and Mallin (Citation2018) discovered a substantial positive linkage between SME service firms' risk-taking and EMs' experience (in years) in emerging markets. Where they concluded in their study that having, prior experience (in years) means taking advantage of opportunities, being open, innovative, and interesting to take-riskier endeavors.

2.3.5. EM ownership

Agency theorists believe -as mentioned by Jensen and Meckling's (Citation1976) study – that there is one way to maximize and leverage the shareholders' equity and reduce agencies' costs is by encouraging firms' directors to own their firms' equity. Thus, this can be achieved by compensating the EMs with the firm's equity. Therefore, the EMs who are interested and would like leverage and maximize their return on equity can go ahead with owning the firm's equity, which might induce them to invest in value-enhancing initiatives, and this could benefit the firm in the long-run in emerging markets (Jenkins & Seiler, Citation1990). In this way, most EMs can increase their returns through the acquisition of large ownership, which leads them to have stronger motives to undertake risky investments rather than non-shareholding EMs (Laeven & Levine, Citation2009). This means that high ownership of EMs might encourage extreme performance and involvement in risky activities, exposing, therefore, firms might face high losses (Sanders & Hambrick, Citation2007; Vo et al., Citation2021).

However, considering the agency theorists' perspective, permitting managers to own their firms' stock is an effective way to increase shareholders' equity and decrease agency pricing (Zhang, Citation2009). Which could be accomplished through providing directors with compensation from the firm equity. Hence, because they hold the firm's equity, EMs would be driven to increase their ROA in emerging markets. This is supposed to motivate them to take actions in regards to investing in initiatives that would add value and profitable for the overall benefit of the company (Jenkins & Seiler, Citation1990). When it comes to the agency theorists, they claim that EMs ownership influences the alignment between EMs and shareholders' interests in emerging markets (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). Hence, modifications to EMs risk-taking perceptions can occur (Beatty & Zajac, Citation1994). Correspondingly, EMs would take advantage of opportunities present in the emerging market in order to boost performance and exploit investment choices in a riskier manner (May, Citation1995).

In a study during the time period from 2009 to 2019, Kaur and Singh (Citation2019) examined the consequence of EM ownership on risk-taking, through taking 12 Nigerian listed deposit money banks as the sample of the study. They demonstrated that the ownership power of EMs has a significantly positive impact on risk-taking in emerging markets. Similarly, Hop (Citation2022) investigated the link between executive management's power and managerial risk-taking, through utilizing a sample of 362 Malaysian publicly traded companies during the time period from 2013 to 2019. The study found that institutional ownership of EMs has a significantly positive impact on managerial risk-taking in emerging markets. According to Math industries et al. (2016), high equity EM ownership could lead to an increase in SME service industry's risk-taking. Where their research was based on secondary information obtained from the UK's FTSE 350 index. As they were gathered from an unbalanced, panel incorporating 260 companies, during the time period between 2005 and 2010. Finally, Farag and Mallin (Citation2018) demonstrated in their findings that no statistically significant correlation exists between EMs ownership and risk-taking in emerging markets.

2.3.6. EM duality

A great number of prior studies have tackled examining the relationship between risk-taking and firm governance. The literature now offers a variety of clarifications, in regard to the effect of EMs' duality on firms' willingness risk-taking in emerging markets. One viewpoint suggests that EMs duality impose a negative effect to make effective decisions, since they move responsibilities and management to the board. Hence, the firm would engage in riskier endeavors. On the other hand, EMs would take better decisions when they do not have duality, as they will look for less risky and costly decisions in emerging markets (Sayari & Marcum, Citation2018).

When EMs take the role as heads of the board, influences them to participate in creating firm strategies (i.e. R&D). Accordingly, their authority is boosted, hence their risk-taking increases (Attia et al., Citation2020). Similarly, Chen and Zheng (Citation2014) assured that duality gives EMs sense of empowerment, entrenchment, and support. Thus, reduces their inclination to act risky. Nevertheless, Anderson et al. (Citation2011) asserts that EMs' decisions in regards to risk-taking are influenced by the time consumed in dual roles in emerging markets.

Tackling Hop (Citation2022) study, they investigated EMs duality and risk-taking, where they utilized data from 40 cooperative banks and 40 listed commercial banks. Despite having unique conclusions for each group, the linkage between EM duality and risk-taking is, however, negatively correlated in cooperative banks whereas it is positively correlated in listed banks. Furthermore, studies by Loukil and Yousfi (Citation2022) and Kanakriyah (Citation2021) found a significant positive correlation among EM duality and risks in emerging markets. Likewise, Muhammad et al. (Citation2022) found that EM duality has a significant and positive relationship with unsystematic risk but a negative relationship with regular risk. Finally, during the time period from 2010 to 2018, Hunjra et al. (Citation2021) examined data from 116 listed banks in 10 Asian emerging markets. Where the study concluded that the linkage among EMs' duality and bank risk-taking is of significant positive nature.

2.3.7. EM tenure

Prior research demonstrates two opposing perspectives in regards to EM tenure. First, some EMs prefer staying in the same role for a longer period of time, hence they aim to advance firm's performance to increase the board members trust through making thoughtful decisions. (Loukil & Yousfi, Citation2022). On the other hand, some argue that short-tenured EMs would not mind taking riskier endeavors by staying innovative for the sake of establishing themselves on the spot in emerging markets. Farag and Mallin's (Citation2018) support this argument through their study findings, which found a negative correlation between EM tenure and firms' to take risks in Chinese-based IPOs. Furthermore, Ferris et al. (Citation2019) and Hoskisson et al. (Citation2017) concluded EMs with short tenure have a higher risk-taking in emerging markets.

Some researchers propose the argue that long-tenured EMs cannot be as concerned with boost their reputation with the board (Ferris et al., Citation2019; Gala & Kashmiri, Citation2022). As they hold high control levels and authority in the firm already (Chen & Zheng, Citation2014), are better able to endure pressure from the board (Loukil & Yousfi, Citation2022), or are decisively recognized within the organization and have control in administrative context (Li et al., Citation2018). Hence, they are less inclined to engage in risky events. Whereas, Huang (Citation2013) stated that as an EM's tenure increases, they turn to display higher dedication towards the overall firm strategy. Additionally, their principles and plan will in return become more fixated on the efficient administration of their businesses. Consequently, these EMs will begin to become less interested in starting becoming entrepreneurs, which means they would focus more on maintaining the current status quo in emerging markets. Thus, they become less likely to engage in risk-taking, in addition to having more restricted sources of information (Finkelstein & Hambrick, Citation1996). This discussion suggests that these conditions prevent firms from engaging in entrepreneurial activities, which results from withholding primary information in emerging markets. This goes in line with the empirical findings of Martino et al. (Citation2020), Ferris et al. (Citation2019), and Zhang and Rajagopalan (Citation2010), who indicated having a significant negative relationship between tenure of EMs and risk-taking.

In spite of the aforementioned findings, Faccio et al. (Citation2016) and Yousfi et al. (Citation2022) found that a positive and significant correlation among EMs' tenure and SME service firms' to take risks. While Mathew et al. (Citation2016) and Makhlouf et al. (Citation2018) that there is no significant correlation among taking risks and tenure.

3. Research methodology

3.1 Population, sample, and data gathering

The targeted population for this study was managers from all administrative levels of small and medium-sized service firms from emerging markets such as Jordan (i.e. owners, purchasing managers, supplying managers, planning managers, operations managers, etc.), and the total number of respondents for this study was 72. Therefore, all small and medium-sized service firms listed for the fiscal years in the period 2018 and 2022 on the Amman Stock Exchange (ASE), Ministry of Industry and Trade in Jordan (MIT), and other related ministries are considered a sampling frame. The sample for this study was the population, which includes construction, real estate, mining, metal refining, chemical, hospitals, pharmacies, cosmetics, food, beverages, clothing, shoes, gasoline, electrical firms, mobile accessories shops, sport centers, radio, TV, all-star hotels, and tourist agencies, etc., of small and medium-sized service firms due to the descriptive nature of this study. The lack of studies on EMs' features affects risk-taking in Jordan as an emerging market and ensures the representativeness that all members of the sample are 'given a known nonzero chance of selection' (Sekaran, 2000).

Each firm included in the sample met the following criteria:

Each firm must be in business for at least 5 years.

Each firm must have 10–249 employees.

The selected sample for this study using sample random sample method by applying a screening method, which is a process that extracts, isolates, and identifies a compound or group of components in a sample with the minimum number of steps and the least manipulation of the sample. Furthermore, this method, which entails making sure research participants, are qualified to offer insightful commentary. The most common ways to screen participants are through specifics in our call for participants or by having; them fill out a screening questionnaire before we chose them to participate. Simple inclusion requirements, like a maximum age, may apply, or you may need to collect more intricate information to guarantee that participants come from a variety of backgrounds and places. More basically, a screening method is a simple measurement providing a 'yes/no' response. This study believes that the features of the EMs that were taken into consideration do not change significantly over time. Hence, this study chose to focus on just five years' worth of data. Additionally, 2018 and 2022 were selected because 5 years in advance data is at least needed in order to calculate the risk variable.

Moreover, because their compliance with particular rules and laws may have an impact on the findings, the financial sector's firms were not included in the analysis. This study also eliminated firms that do not have comprehensive data for the independent and dependent variables. Furthermore, the information regarded in these study variables was obtained from ASE, and the annual reports concerning the relevant financial years. Thus, the sample ready to be studied included 72 SME service firms for analysis out of a total of 301 firms' year observations, depicting a 23.9% response rate. illustrates the method used to select the targeted sample.

Table 2. Illustrates the method used to select the targeted sample and the type of small and medium-sized service industries. (Source: Authors' own work).

The target sample of this research was SM-sized service firms operating in the Chambers of Commerce and Industry in Jordan located in the Middle East region using a random sampling technique. Most countries in the Middle East region have committed to fostering private sector-led inclusive growth, obtaining the adoption of policies to boost SM service firms' development. These reforms are at varying phases of advancement, which include Jordan country. Therefore, the SM service firms in the Arab World can play an important role in addressing the challenges of creating employment and diversifying economies. We mainly targeted these countries due to the majority of firms in these countries are SM service firms. SM service firms contribute a range of 30%–50% of GDP in Arab economies in general while reflecting around 70%–80% of the targeted and participated SME service firms in the three countries included in this study. It is estimated that SM service firms account for 80%–90% of firms in the MENA region (Herrmann & Datta, Citation2006) and around 97% in the Arab World (Gonzales-Bustos et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, we have good access to a large number of firms to participate to increase the response rate and to succeed in reaching the main objectives of this study. Additionally, the growth rate in the number of SM service firms has increased to high limits during the last two decades. In particular, SM service firms in these countries are a key source of new job creation focusing on recruiting talented candidates in emerging and developing countries, accounting for around 45% of new jobs (Ayyagari et al., Citation2015). The researchers focused in this study only on SM service firms for some reason, important points are summarized as follows:

All over the world, SM service firms in emerging markets play a vital role in national economies in most countries in general, in the Middle East region, Jordan in particular, and in various sectors. This type of company in emerging markets contributes to creating new job opportunities and benefits, in addition to its contribution to innovation, which will achieve environmental sustainability and greater growth. Moreover, these companies have great opportunities to contribute and participate in the regional and even global economy in many sectors, especially in the era of digitization and digital transformation.

Most of the governments of the Middle Eastern countries as emerging markets, especially the three countries included in the study, have worked during the last two decades to enhance the role of SM service firms in their countries. As well as those emerging from them, to participate and contribute to the globalized and digital economy and reaping its benefits depends largely on facilitating commercial and logistical procedures to increase their practical and operational capabilities and performance in general. This is in addition to lifting internal restrictions on this type of company by governments, facilitating the movement of their trade, mitigating the potential risks they may face, and raising their efficiency to increase the ability to maneuver and compete in a highly competitive, dynamic business environment to ensure the continuity of their business over time, as well as increasing investment and growth in various service and manufacturing sectors in emerging markets.

3.2. Instrument validity

According to Fraenkel and Wallen (Citation2003), validity is defined as 'the appropriateness, meaningfulness, accuracy, and utility of the precise conclusions a researcher draws based on the data they gather'. An instrument's validity guarantees that it can measure the intended idea. As a result, in order to attain a high degree of instrument validity, questionnaire surveys were sent to several experts and academics who assessed the questionnaire's validity and verified that it was relevant, meaningful, and applicable to the intended setting. Their advice and comments were very helpful.

3.3. Instrument reliability

According to Fraenkel and Wallen (Citation2003), reliability is defined as the 'consistency of scores or answers from one administration of an instrument to another, and from one set of items to another'. An instrument's reliability score shows the consistency and stability of the items it contains, as well as the extent to which it accurately measures the concept (Creswell, 1994). The most often used reliability test is Cronbach's alpha, which gauges an instrument's internal consistency. An alpha score greater than 0.7 will be considered acceptable in this study. All survey item values were found more than 0.70. The definition of Cronbach's α is:

where, K is the number of components,

the variance of the observed total test scores, and

the variance of component i for the current sample persons (Cronbach, Citation1951). summarizes all reliability values for all items used in the survey.

3.4. Variable definition and measurement

3.4.1. Dependent variables

SME service firms' risk-taking in Jordan is considered the dependent variable for this study, which includes the standard deviation of the firm return on assets ratio. Prior studies have quantified this variable using a variety of metrics. Some of which include the ROA ratio (Aabo & Eriksen, Citation2018; Gala & Kashmiri, Citation2022; Faccio et al., Citation2016; Gengatharan et al., Citation2020), leverage (Loukil & Yousfi, Citation2022), the SD of the firm stock return (Loukil & Yousfi, Citation2022; Yousfi et al., Citation2022), research and development expenditures (Hunjra et al., Citation2021). In addition to, the SD of the firm Tobin's Q ratio (Martino et al., Citation2020).

This study utilized risk-taking metric as the SD of firm's ROAs ratio. Hence, the SD of ROA shows the firm is earning volatility; riskier operations provide more unpredictable earnings (Zhang, Citation2009). Moreover, the SD of ROAs is considered a riskier firm policy, according to Gala and Kashmiri (Citation2022) and Gengatharan et al. (Citation2020), which yield more inconsistent returns and earnings. Due to its potential to accurately capture the total riskiness of decisions related to business investment, the volatility of ROA is a broadly used risk proxy on financial economics, in the literature. Additionally, we divide revenues before interest and tax to obtain the SD of ROA for four years ahead of the present year, at the bare minimum.

3.4.2. Independent variables

EMs features is serving as the study's independent variable. The EM features picked are the ones that have been widely used in prior research. Which in turn are foreseen to have an effect on how risk-taking is carried out by SME service firms. According to Nilmawati et al. (Citation2021) and Yusuf et al. (Citation2022), EM gender is signified as a pseudo variable with the value '0' if the EM is female and '1' if the EM is male. Furthermore, in their study, Martino et al. (Citation2020) and Ghazi (Citation2022) employed the qualifications and age of EMs. Where EM's age is resulted by subtracting the year of monitoring from the EM's birthdate. On the other hand, depending on the qualifications of EMs, is given a value of 'three' if he/she holds a PhD, is given 'two' if he/she holds a Master's degree, is given 'one' if he/she holds a bachelor's degree, and 0 if he/she does not have any of these qualifications. The time EMs spent working in this position throughout their career, even if it was at different SME service firms was also taken into account in emerging markets. Following the steps of Muhammad et al. (Citation2022) and Kanakriyah (Citation2021) studies, EM ownership and duality were included. Moreover, duality was utilized as a pseudo variable with the value 'one' if the EM serves as board chair and 'zero' if otherwise. In addition, EM's share of the firm's capital to its total assets ratio is used to calculate EM ownership. Finally, EM tenure is taken into consideration, which is measured based on the total number of years the EM has worked for the organization as EM in emerging markets (Hop, Citation2022; Hoskisson et al., Citation2017).

3.4.3. Control variables

When investigating the relationship between EM qualities and service firms' risk-taking, it is important to include a number of control variables in order to rule out other potential reasons. Many researches such as (e.g. Makhlouf et al., Citation2018; Chen and Zheng, Citation2014; Nilmawati et al., Citation2021), utilized ROA as one of the control variables to account for vast differences in management quality. It demonstrates how closely a company's profitability is related to its total assets. Loukil and Yousfi (Citation2022) claimed that ROA is able to provide a better explanation of firm risk-taking. Furthermore, Yeoh and Hooy (Citation2020) and Herrmann and Datta (Citation2006) to take into consideration the variation in the investment opportunities when it comes to taking advantage of the opportunities by the investors, which in turn determined firms' value, perform the book-to-market value ratio (BMV).

Investors' investment decisions are highly dependent on their readiness to offer a premium and their projections of how much future profit such firms will generate. BMV is more vulnerable to the predicted emerging market risk premiums, making it more likely to reflect risk (Barth et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, Peterkort and Nielsen (Citation2005) suggested that the BMV ratio might be utilized as a risk proxy. They also took into consideration the firm size as a control variable, following Hop (Citation2022), who discovered a correlation between risk and the size of the firm. The natural log of the total assets (e.g. Muhammad et al., Citation2022; Alhmood et al., Citation2020; Makhlouf et al., Citation2018; Vo et al., Citation2021) represents the size of the firm.

Finally, through by dividing total debt by total equity, we can get the firm leverage ratio, where a rise in debt in comparison with equity is probable to have an effect on the firm's performance. Similarly, a measurement of risk in firm financing is known as choice leverage (Devarajan et al., Citation2022). Which implies the leverage ratio, and the risk of default are highly connected, hence a negative aftermath on firm's net profitability is seen (Faccio, 2016). Similarly, a number of previous studies have utilized advantage as a measurement of risk-taking (e.g. Barth et al., Citation2022; Attia et al., Citation2020; Farag & Mallin, Citation2018; Muhammad et al., Citation2022).

3.5. Research regression model

The regression model as shown below has been created to investigate the association between service firm's risk-taking and the features of EMs:

(1)

(1)

where:

RISK: firm i risk-taking in year t

GDR: gender of firm i EM in year t.

AGE: age of firm i EM in year t.

QUAL: qualifications of firm i EM in year t.

EXP: experience of firm i EM in year t.

OWN: share ownership of firm i EM in year t.

DUAL: EM duality for firm i in year t.

TENR: EM tenure for firm i in year t

ROA: return on assets ratio for firm i in year t.

BMV: book to market value ratio for firm i in year t.

SIZE: natural Logarithm of total assets for firm i in year t

LEV: leverage ratio for firm i in year t

LIQ: grow t

R&D: research and development t

: error term

This study is drawn on a sample of SMEs service firms in emerging markets that are listed on the Amman Stock Exchange (ASE) in Jordan between 2018 and 2022. It reached some of the following findings. First, EMs with long experience are likely tend to have debt to fund the firm's activities and they do not affect growth and innovation activities. In affecting firm risk-taking fact, old EMs belong to have good relationships with some board members or have served as a board member in other firms. Thus, EMs are less likely to challenge the firm and take risky or critical decisions. Another interpretation, related to the EMs in Jordanian context firms could be that EMs with long experience have long tenures (approximately on average 8 years), therefore, they are trying to avoid taking risks in their firms. In the same scenario, this study offers evidence that politically connected EMs in Jordanian SMEs have non-significant correlations with risk-taking, which means that there are good relations between the firms and political spheres in Jordan. Additionally, many policymakers have been signed EMs in high positions, thus, for sure they take into their consideration care their reputation, and they are likely to adopt conservative leadership. Third, the volatility of revenues declined in the presence of long-tenured EMs. In fact, long-tenured EMs lead to less board of directors' pressure and are not challenged by the directors' expectations. Particularly if the EMs were been board members themselves. In contrast, short-tenured EMs might have a good image in the marketplace and are more likely to have good relations with board members. Often, they relied on a conventional and conservative management style that does not drive major changes, which declines the volatility of revenues and debt funding.

However, EMs who own their firms, and have management, financial, and law certificates decrease the total risk in their firms and try to increase the growth rate of their assets. This outcome is consistent with Martino et al. (Citation2020) emphasizing that management, financial, and business programs attract more risk-averse and who are students that are more conformist. Thus, their business competencies and their specializations particularly in finance, law, and accounting domains will help them to tackle risks that might face their firms and achieve better emerging market and financial performance (Atayah et al., Citation2022). Finally, this study found that there is no correlation between science-educated EMs with firm risk-taking but might have an impact on declining liquidity risks through the increase of cash availability. Our outcomes present prove that the EM profile is a key determinant for the business strategy, particularly in terms of growth and research and development activities. Additionally, the EM's features such as qualifications, past professional experience, and the EM network as could influence the EM's risk preferences in emerging markets.

An effective way to determine the quality of management is through stock markets, since it incorporate stock prices with the demographics and features of EMs (Farag & Mallin, Citation2018). Likewise, Pan et al. (Citation2013) assure that having EMs who are competent, qualified, and highly experienced aid in reducing the ambiguity concerning management quality. Which in turn influences stock prices. Noting that prior research reinforced the fact that management quality contributes to firms' risk-taking and decision-making (Farag & Mallin, Citation2018; Sanders & Hambrick, Citation2007). A number of prior researches were found that have studied the impact of EM's qualities and features on firm performance (Farag & Mallin, Citation2018), in addition to novelty and stock return (i.e. Hunjra et al., Citation2021). Similarly, studies were found that examined the impact of EM's features on firm environmental conduct (i.e. Qawasmeh & Azzam, Citation2020), firm sustainable development (Chen & Zheng, Citation2014), leverage (i.e. Alawaqleh et al., Citation2021), and international (i.e. Saeed & Ziaulhaq, Citation2019). Despite this, researchers have attempted to study the impact of the features of EMs on SME service firms' risk-taking, on a small scale (Kaur & Singh, Citation2019, among others). Farag & Mallin (Citation2018) stated that EM's features could have an effect on a SME service firm's risk taking, confidence, and egoism to engage in risk-taking. However, it is worth mentioning that prior research gave the most attention to the impact of EM's features on accounting conservativism (Barth et al., Citation2022), real earnings management (Devarajan et al., Citation2022), and quality of audit (Gala & Kashmiri, Citation2022). Thus, based on the author's information, not any study has attempted to study the association between EM's demographics and SME service firm's risk-taking in Jordan, which is the aim of this current paper.

In an attempt to bridge the gap in the existing works, this study examined the impact of EMs' demographic features (i.e. gender, age, ownership, experience, qualification, duality, and tenure) on taking risks of the Jordanian businesses. Where the analysis of 72 SME service firms listed on the Amman Stock Exchange (ASE) in Jordan country showed a negative and significant linkage between EM's qualifications, experience, and ownership and SME service firms' to take risks. On the other hand, EM tenure and firm take risks were found to have a positive significant correlation. Likewise, the analysis showed that EM's gender, age, duality, and risk-taking variables are unrelated.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Descriptive statistics

For our variables in this study, summarizes the descriptive statistics as illustrated below. In regards to the dependent variable, RISK, the sample firms' average ROAs over a 5-year period, which assesses the risk-taking of EMs' of firms that they have faced, varied on average by 7.38% with an SD of 9.72%. This proposes that the propensity for risk-taking of EMs' among these firms varies. The sampled firms' average and minimum levels of risk-taking were 0.12% and 82.65%, respectively.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of quantitative variables. (Source: Authors' own work).

demonstrates that men make up about 96.34% of the risk-taking of EMs in the SME service firms in emerging markets that were taken as a sample of this study. This may be linked to the fact that the Jordanian culture does not prefer women holding such roles. This goes in line with the study findings of Alqatamin et al. (Citation2017), as they concluded that the risk-taking of EMs' found by men, which is managed by 94% of the Jordanian firms in the emerging markets they studied, applies to other nations and countries worldwide. An example is, in the UK and the USA, female risk-taking of EMs makes up just approximately 6% of the overall total risk-taking of EMs, while in the United Arab Emirates, a further 5% is accounted for, according to the 2012 Grant Thornton International Business Report. On the other hand, considering EMs' ages, the youngest EM is 31 and the oldest is 83. These insights are close to those demonstrated by Alawaqleh et al. (Citation2021), who found that the average risk-taking age of EM is 51.31 years. In addition, Tran and Pham's (Citation2020) study findings illustrate that the average risk-taking age of EMs' in Jordan is 53.65 years, with a range of 31 to 83 years. Similarly, these results indicate that the risk-taking EMs of the firms under study in the chosen sample had post-graduate degrees; the mean and SD for this variable are 1.03 and 0.64, respectively. Hence, the findings concerning the risk-taking of EMs' experience show that a firm's risk-taking of EMs typically served for 12 years in the sample service firms, which ranged from one to 56 years in emerging markets. These findings are aligned with Saeed and Ziaulhaq's (Citation2019) findings, who stated that 96% of the current risk-taking EMs' have previous professional experience.

The average risk-taking EM owns 1.99% of the service firm shares they work for, although this varies greatly among businesses, from 0% to as much as 58%. However, this proportion is a little lower than that given by Qawasmeh and Azzam (Citation2020), who claim that the risk-taking EMs' hold roughly 3.4% of the firm's shares. Moreover, this research finding reveals that about 15% of Jordan's risk-taking EMs' had previously served as chairs of the boards of the service firm. Similarly, the findings of this study are much higher than the 0.69% average duality for Jordanian service and manufacturing firms published by Kanakriyah (Citation2021). Finally, the tenure of risk-taking EMs' is approximately 8.76 years on average, with a prolonged term in the office of 51.5 years and a tenure period of 1 year. This finding is in alignment with prior research. Examples include the study by Martino et al. (Citation2020), who concluded that an Italian risk-taking EM's tenure is 7 years on average.

The control variable statistics imply that, the average and SD of ROA are 3.52% and 17.17%, respectively. Accordingly, service firms in Jordan make an average return on total assets of 3.52%. Moreover, the sample firms' BMV has a mean of 1.67 with a SD of 10.6%. The mean of the firm size tested by the natural logarithm of the whole assets is 8.78, with a SD of 0.487. Finally, the average (SD) of firm leverage is 41.76% (29%), indicating that 38% of non-financial firms listed on ASE are financed by debt in emerging markets.

4.2. Correlation analysis

exhibits the Pearson correlation coefficients for all constructs of the study. It demonstrates that risk-taking EM AGE has a positive relationship with TENR and EXP in emerging markets. OWN and DUAL have a positive correlation. Furthermore, OWN is negatively related to QUAL in emerging markets. The positive correlations between AGE, TENR, and EXP are logical and straightforward; as time passes in emerging markets (increase in EM age), the risk-taking EMs' life and job experience increases, as does tenure, which signifies the length of time the EM has held the existing/same position. Except for EXP. and TENR in emerging markets, which are positively correlated, all of the correlation coefficients between the independent elements are <0.70. The correlation between EXP and TENR is positively highly correlated at 0.7875. The high correlation (more than 70%) could have an impact on the analysis. To confirm that no multicollinearity problems exist, we calculate the variance inflation factor (VIF), as illustrated in the last column of , which shows that no multicollinearity problems exist because all VIF values are less than ten as recommended by Gujarati (Citation2003).

Table 4. Pearson correlation matrix. (Source: Authors' own work).

4.3. Regression analysis

The data are analyzed using multiple regression techniques to analyze the collected data and be able to test the correlation among the SME service firm's risk-taking EM features. The outcomes of the analysis are demonstrated in . Where the F-statistic indicates the validity of the model for analysis purposes, as it was found significant at the 5% level (p ≤ .05). Similarly, the R2 value of 0.563 implies that 56.3% of the variation in firm risk-taking is accounted for by the variables of the model.

Table 5. Results of the ordinary least square regression. (Source: Authors' own work).

All independent variable coefficients regarding risk-taking EM features (GDR, AGE, QUAL, EXP, OWN, DUAL, and TENR) and the control variables (ROA, BMV, SIZE, and LEV) are shown in . Due to the lack of statistical significance for the GDR coefficient, it is suggested that the risk-taking EM's gender has no effect on risk-taking in the service sector in emerging markets. Despite this, and given that 99% of the executives of companies with ASE listings are males, this result is considered unclear and uncertain. These results are aligned with those of Gala and Kashmiri (Citation2022), who found no relation between gender and risk-taking in service firms. On the other hand, Nilmawati et al. (Citation2021), Orens and Reheul (Citation2013), and Yousfi et al. (Citation2022) studies, which utilized the SD of ROA, found a negative and significant association among risk-taking EMs' gender and service firms' towards risk-taking. Hence, they oppose this finding.

When it comes to the age variable, the AGE coefficient likewise reveals no association between risk-taking EMs' age and service firms. Unlike expectations, these results may have been reached because the sample majority were in their middle years in emerging markets, which are aligned with Ferris et al.'s (Citation2019) findings. They are also aligned with Gala and Kashmiri's (Citation2022) and Aabo and Eriksen's (Citation2018) findings; however, they used various risk-taking proxies to show the same results. However, when utilizing different risk-taking proxies. Whereas, Farag and Mallin's (Citation2018) and Chen and Zheng's (Citation2014) study findings revealed a statistically significant and negative correlation between the variables. Yet, according to Devarajan et al. (Citation2022), a correlation between risk-taking EMs' age and the SD of ROA measures is negative nature in emerging markets.

The QUAL Coefficient was found to be significant and negative at the 1% level, which demonstrates that the educational background of risk-taking EM's has a negative effect on the service firms, and vice versa. This indicates that risk-taking EMs' with more advanced degrees (PhD, MBA, and Bachelor's) are less drawn to risk-taking, which is also aligned with the upper echelon theory. This is because risk-taking EMs' education progresses; they will learn how to avoid faults and failures and to strive toward the firm's long-term prosperity. On the contrary, Makhlouf et al. (Citation2018) concluded that there is no relationship between any of the five risk-taking proxies utilized and EM features and qualifications in their study. On the other hand, Yeoh and Hooy (Citation2020) concluded, by utilizing two other proxies that there is a significant and positive linkage between risk-taking EMs' features and qualifications and the SME service firm.

The coefficient on EXP is found to be statistically significant and negative at the 10% level (p = .065), suggesting that risk-taking EMs' tend to engage in less risky decisions and actions the more they gain professional experience. They tend to adopt a conservative style of thinking, leadership, and management, thus reducing the service firm's operational ROA. Loukil and Yousfi's (Citation2022) study findings emphasized the significant negative correlation between risk-taking EMs' expertise and service firms' risk-taking, utilizing five risk-taking extents. Furthermore, they ensure that the need for debt financing and stock return volatility will decrease as risk-taking EMs gain more expertise. However, the results of the current study oppose the Tran and Pham (Citation2020) study findings, as they discovered a significant positive relationship between firm risk-taking and EMs' professional experience. In addition, they suggested that risk-taking EMs' with more professional experience are more likely to engage in risky decisions and activities. In this case, they become more motivated to be more creative and implement riskier changes. On the other hand, (Alawaqleh et al., Citation2021) found that no correlation exists between risk-taking EMs' experience and service firms' willingness to take risks.

The coefficient on OWN for risk-taking EMs' ownership is negative and significant at the 1% level, which demonstrates that a big interest in the firm's shares presented by risk-taking EMs may limit his/her willingness to take risks. This could be explained by risk-taking EMs' desire to guard their ownership from losses and, as a result, refrain from taking on any risky actions or decisions. Furthermore, this current study's findings are aligned with Faccio et al.'s (Citation2016) study findings. Their study revealed a significant negative association between risk-taking EMs' ownership and the risk-taking of their firms, especially when measured using the ROA standard deviation. Yet, we can still consider the relationship between variables important despite determining risk through leverage. However, it moves in the opposite direction. In contrast to the aforementioned results, Muhammad et al. (Citation2022) found that a substantial positive link between ownership and risk-taking exists when measured using the ROA standard deviation.

Because the risk-taking EM's DUAL coefficient is not statistically significant, it does not affect the EM's risk-taking. Hence, this finding is in line with Muhammad et al. (Citation2022), who reached the same findings by utilizing our risk-taking proxy. Likewise, Makhlouf et al. (Citation2018) also reached similar findings by utilizing four distinct risk-taking proxies. However, the study by Kaur and Singh (Citation2019) demonstrated the relationship between two risk proxies and duality, which was found to be positive. Finally, the association between duality and risk-taking varies between cooperative and listed banks; where listed banks have a positive correlation, while cooperative banks have a negative correlation (Hop, Citation2022).

At the 10% level, TENR, the last independent variable, shows a positive statistically significant coefficient. This suggests that the longer the risk-taking EMs hold this position, the more likely it is that they will engage in the EM's risk-taking. As they have built up their reputation and career in the emerging marketplace. Hence, they are less concerned about losing their positions and are less subject to the BoD imposing pressure. Hence, they are more inclined to take risks, be open to innovation, and come up with new business ideas. The results of Yusuf et al. (Citation2022), Gala and Kashmiri (Citation2022), Yeoh and Hooy (Citation2020), Gengatharan et al. (Citation2020), Devarajan et al. (Citation2022), Qawasmeh and Azzam (Citation2020), and Gala and Kashmiri (Citation2022) all indicated that tenure is unrelated to risk-taking despite utilizing diverse risk-taking measures, which are in contrast to their findings. Martino et al. (Citation2020) utilized five risk-taking proxies, where they discovered that two proxies have a link with the risk-taking EMs' tenure, while there are three proxies seen as unrelated.

The coefficients on ROA and SIZE are also significant and negative in emerging markets, which illustrates that a firm's willingness to take risks declines as it increases in size and ROA. In addition, the book-to-market ratio and risk-taking are significantly positively correlated, as demonstrated by the coefficient on BMV. Nevertheless, as the LEV variable does not have a significant coefficient, it means that no association between leverage and firms' risk-taking can exist.

4.4. Control variables effect

The regression analysis was conducted to estimate the impact of the risk-taking EMs' features on the SM-sized service firms' risk-taking with the role of the control variables (i.e. GDR, AGE, QUAL, etc.) shows the results of the regression analysis.

Table 6. The regression analysis on the dependent variablesTable Footnote*. (Source: Authors' own work).

Two models were used to explain the behavior of the variables under study. The first model shows the role of the control variables on the dependent variable (risk-taking EMs' features on the SM-sized service firms' risk-taking), while the second variable explains the behavior of all the variables, including all dependent variables (i.e. GDR, AGE, QUAL, EXP, OWN, DUAL, and TENR). By looking at the first model, it is noted that the unstandardized coefficient of the following control variables was high (i.e. AGE: 'β = 0.886, Sig.=0.031 < 0.05', QUAL: 'β = 0.672, Sig.=0.014 < 0.05', EXP: 'β = 0.723, Sig.=0.026 < 0.05', DUAL: 'β = 0.669, Sig.=0.043 < 0.05', and TENR: 'β = 0.561, Sig.=0.036 < 0.05'), moreover, the significant values of the mentioned variables were significant; all values were <0.05. Whereas, the unstandardized coefficients of the other control variables (i.e. GDR: 'β = −0.024, Sig. = 0.746 > 0.05', and OWN: 'β = −0.045, Sig. = 0.524 > 0.05') were low and had negative effects, moreover, the insignificant values of the mentioned two variables were insignificant (Stockemer, Citation2019). This indicates that there is a clear impact of some risk-taking EMs' features on the SM-sized service firms' risk-taking, while others have not. In the second model, all the variables were entered to assess their impact on the dependent variable/SM-sized service firms' risk-taking. The analysis revealed only ROA: 'β = 0.624, Sig. = 0.030 < 0.05', BMV: 'β = 0.744, Sig. = 0.006 < 0.05', and LEV: 'β = 0.857, Sig. = 0.022 < 0.05' have a strong significant impact on the risk-taking EMs' features on the SM-sized service firms' risk-taking. However, the same model does not demonstrate a significant impact of the control variables through the firm's size (β = −0.024, Sig. = 0.648 > 0.05), on the relationship between risk-taking EMs' features on small and medium-sized service firms' risk-taking variables, since it has no significant effect (Stockemer, Citation2019). The second model justifies the results were interpreted by the first model.

5. Conclusions and implications

This study, which was limited to the SME service firms, looked into how risk-taking EMs' characteristics affected the risk-taking propensities of SME service companies in Jordan as an emerging market, both a developed and developing nation. An analysis of the connection was conducted using yearly earnings volatility, employing a sample of 72 SME service businesses that were registered on the ASE between 2018 and 2022. The study's conclusions serve as a useful guide for investors to take into account EM traits, particularly when evaluating the risks connected to companies they wish to invest in and when determining the risk of a business throughout the investment decision-making process. It also gives regulators insight into how crucial it is to consider risk-taking EMs' characteristics when creating risk-taking procedures in emerging markets. In a similar vein, the board of directors ought to focus primarily on risk-taking EMs' caricaturists and qualities, particularly EM tenure, since this characteristic raises EM's exposure to risks that may have a negative impact on the company. This study is, therefore, thought to be the first of its sort in Jordan. Furthermore, the empirical findings show that risk-taking EMs' qualifications, experience, and ownership of the SME service firms' shares have a negative and substantial impact on the risk-taking of SME service firms in Jordan as an emerging market. Furthermore, the ROA ratio and business size have a negative and considerable impact. The study's findings indicate that there is a strong positive correlation between the book-to-market ratio of the company and the risk-taking EM's tenure. Nevertheless, it has also been discovered that the risk-taking behavior of SMEs in the service sector does not correlate with the risk-taking EM's age, gender, dualism, or firm leverage ratio. Additionally, the results of this study show that an EM's risk-taking decreases as their degree of education, experience, and skill as the risk-taking EMs' in the SEM service business increases, as does their share ownership. Conversely, more risk-taking would follow an increase in the risk-taking EM's tenure. Similar to this, stock markets may be seen as a mirror of the risk-taking EM's characteristics, and how the risk-taking EM's professional, experienced, informed, and risk-averse traits can influence its characteristics, since these characteristics may have a major impact on stock prices. Therefore, this study has examined aspects of the risk-taking EMs in the SME service firm as well as the businesses' readiness to take risks in Jordan since it is believed that uncertainty regarding the management quality and competency of the risk-taking EMs' is a crucial issue that might affect shareholders' viewpoint. As a result, a broad comprehension of these factors' effects may be obtained.

5.1. Theoretical implications

This study has several theoretical implications. First, this study was conducted to investigate the effect of risk-taking EMs' features on SME service firms in Jordan as an emerging market, which included age, gender, qualifications, expertise and experience, ownership, duality, and tenure criteria, using regression analysis to examine the association between the risk-taking EMs' features and firm's risk-taking, represented by the standard deviation of the firm's return on assets ratio in one study model, and in one academic range. Furthermore, it inserted the control variables represented by return on assets (ROA), book-to-market value ratio (BMV), firm size, and firm leverage ratio for examining the effect of risk-taking EMs' features on SME service firms' risk-taking, thus, it requires the inclusion of several control variables to rule out more alternative explanations. Therefore, this study contributed to providing a valuable contribution to the theories related to the human capital theory, which centres on the idea that investments in people and employees, such as education, expertise, and knowledge, increase workers' productivity and skills while reducing the probable risks in their workplace (Goldin, Citation2016). The second is the trait theory of personality, which proposes that people have specific and distinguished features and traits, and it will strengthen and intensify those traits that account for personality differences. Therefore, the trait approach is considered one of the main theories to explore and study personality. Trait theory proposes that individual personalities are a compound of broad dispositions (Fajkowska & Kreitler, Citation2018). Thus, a feature in a personality is considered a feature that meets three criteria: it should be consistent, stable, and vary from one person to another. This study also focused on its great contribution to the inclusion of control variables as moderated factors and the extent of their impact on the relationship between risk-taking EMs' features and SME service firms' risk-taking, and the focus was on this by analyzing the research data. There was a shortage and a clear gap in studying control variables as a moderator factor in the relationship of risk-taking Ems' features with SME service firms' risk-taking. This study contributes greatly to an in-depth understanding and study of causal relations that include risk-taking EMs features and the ability to analyze them in various operations and activities in serving firms in developing countries. It also works to increase understanding of risk-taking EMs' features and the great importance that services must take into account now.

Furthermore, this study presents a set of theoretical implications, as follows: First, the empirical results demonstrate that SME service firms' risk-taking in Jordan is negatively and significantly influenced by risk-taking EMs' qualifications, expertise, and experience, and ownership of the SME service firms' shares. Second, the findings show that the risk-taking EMs' features are negatively and significantly influenced by firm size and ROA ratio. Third, the findings of this study also show; it has a significant positive relationship with the risk-taking EM's tenure and the firm's book-to-market ratio. However, it is also found that there is no correlation between SME service firms' risk-taking and the risk-taking EM's gender, age, duality, or firm leverage ratio. Fourth, the study finding illustrates that an increase in the risk-taking EM's qualifications level, expertise, and experience as risk-taking EM features of an SEM service firm, and share ownership decrease the EM's risk-taking. Fifth, if the risk-taking EM's tenure increases, the risk-taking would increase as well. Finally, stock markets can be seen as a reflection of the risk-taking EM's features, how knowledgeable, experienced, professional, and risk profile can affect the risk-taking EM's features, since these features might reflect on stock prices significantly.

5.2. Managerial implications