?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

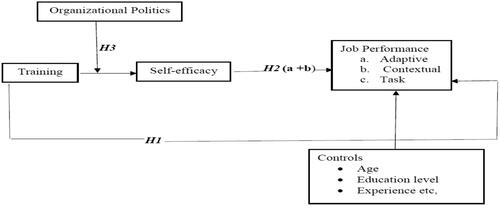

This study examines the effect of training practices on job performance in the public sector of a sub-Saharan African region. Building on social cognitive theory, this study integrates the mediating role of self-efficacy and the moderating role of perceived organizational politics to explain employees’ performance in public universities. This study is a quantitative survey using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to analyze the responses of 370 non-teaching staff members at public universities in Ghana. The findings show a positive and significant relationship between training and job performance. The study also finds that self-efficacy fully mediates the effect of training on task and contextual performance but partially on adaptive performance. The study further establishes that perceived organizational politics moderate the effect of training on contextual performance but not on self-efficacy and job performance. Again, perceived organizational politics moderated the relationship between self-efficacy and job performance. Based on the findings, this study provides two key practical implications for the leadership of public institutions in general and public universities. First, the human resources divisions of various public universities must concentrate on training to enhance job performance. Second, the directorate of human resources of public universities and all public sector institutions must devise strategies to minimize organizational politics, which negatively affects overall job performance. Implications for theory and practice are also discussed.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Globally, organizations rely on improved skills, knowledge, and capability of a talented workforce to create competitive advantage (Halawi & Haydar, Citation2018; Lin & Hsu, Citation2017; Showkat et al., Citation2023). Therefore, organizations continuously focus on improving employees’ job performance to enrich organizational performance to gain a competitive advantage (Chatterjee et al., Citation2023; Thevanes & Dirojan, Citation2018). Enhancing employee performance cuts across all sectors of the economy, such as agriculture, manufacturing, construction, and services. To enhance the performance of the service sector, there is a need to consider the work done by non-teaching staff in various universities. University non-teaching staff rarely achieve high job performance, which is influenced by several factors (Gyimah et al., Citation2022). Factors such as self-efficacy, training, promotion, and salary are likely to significantly affect job performance within the university context; hence, they deserve recognition and attention (Abu-Tineh et al., Citation2023). One of the crucial strategies for universities and organizations in general to gain a competitive advantage is to utilize training (Yang et al., Citation2023). Training is an important function in cultivating employees’ explicit and implicit knowledge, skills, and abilities and transfers employees into valuable resources to improve job performance (Lin & Huang, Citation2021). For these reasons, training has become a key variable in productivity drivers at the firm and national levels. For instance, in Part III under the Protection of Employment of the Ghana Labor Act 2003, Act 651 Section 10 (Rights of a Worker) indicates that it is the right of an employee to be trained and to help him/her to develop skills and be given information that applies to the job.

Current research studies on the subject have focused on how training practices affect job performance and suggest that employees’ job performance is dependent on the training received (Haryono et al., Citation2020; Kanapathipillai & Azam, Citation2020; Sheeba & Christopher, Citation2020). Although training has a positive relationship with job performance (Lyons & Bandura, Citation2022; Park et al., Citation2018), it is difficult to realize this when employees undergoing the training program lack self-efficacy. Several other studies, such as Mangkunegara and Agustine (Citation2016), argue that training partially affects employees’ job performance. Therefore, to achieve the full effect of training on job performance, the literature has suggested that the role of other factors, such as self-efficacy and environmental and organizational factors should be concurrently considered in the training-job performance relationship. For example, Park et al. (Citation2018) suggest that future studies on the relationship between training and job performance could look at other motivational factors such as self-efficacy and how it will influence job performance. Garavan et al. (Citation2021) suggest that environmental and organizational content moderators should be incorporated when examining the job performance of employees.

It is vital to understand the mediating and moderating roles of self-efficacy and perceived organizational politics in employee performance after training. This is because the training of employees does not automatically translate into performance unless they believe in their capabilities to do so, and resources for the training practice are made available to employees. Self-efficacy studies have consistently shown that it is one of the key factors that predict performance (Bandura, Citation2015; Carter et al., Citation2018; Yagil et al., Citation2023). Thus, self-efficacy influences learners’ behavior and transfer outcomes both directly and indirectly through its mediating effect on outcome expectations (Chiaburu & Lindsay, Citation2008; Grossman & Salas, Citation2011). For instance, Chiaburu and Lindsay (Citation2008) indicate that employees’ perceived training and self-efficacy positively influenced their motivation to perform. Stajkovic et al. (Citation2018) conclude that employees with high levels of self-efficacy are less likely to give up on the pursuit of their responsibilities and, therefore, perform better on their job. The behavior and actions that occur informally inside an organization are usually perceived as organizational politics. This encompasses individuals’ actions aimed at supporting their private interests, which may agree or disagree with those of other individuals (Bukhari & Kamal, Citation2015; Ferris et al., Citation2018). The individual actions directed toward achieving one’s own self-interest goals without regard for the well-being of others or the organization, which is referred to as organizational politics (Kacmar & Baron, Citation1999), is notable for both its pervasiveness and capacity to disrupt organizational processes and impact workers’ job performance and well-being. For example, Ahmad et al. (Citation2017) conclude that organizational politics have a significant and negative relationship with job performance.

Despite the impact of self-efficacy on the performance of trained employees coupled with burgeoning research on training-job performance relationships, there is a paucity of studies and inconsistencies in the literature on how self-efficacy and perceived organizational politics partially or fully affect the job performance of trained employees, particularly in developing countries (Mangkunegara, Citation2021). Meanwhile, these regions are emerging in terms of the labor force and hence need more training to build the strong human capital that would be used to increase productivity (Gyimah et al., Citation2023). This study sought to fill this gap by analyzing the influence of training practices on job performance, which is the mediating and moderating role of self-efficacy and perceived organizational politics on the job performance of non-teaching staff at public universities in Ghana.

This study makes some key contributions to both literature and practice. First, the study employs social cognitive theory to explain this integrative training–job performance relationship through self-efficacy and its dependence on organizational politics. By so doing, the study advances training and performance research by drawing on the tenets of social cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation2015) to theoretically specify and validate training and job performance. Second, the study offers empirical evidence that will augment the discussion on the effect of training on employee job performance in relation to, perhaps, mediating and moderating variables. Third, this study provides evidence that self-efficacy plays a mediating role in the training-performance relationship, and this relationship is also dependent on organizational politics. Based on this assertion, this study makes a fourth contribution by theorizing that the suggested relationships will provide diverse perceptions in understanding the dynamics through which training improves job performance. Last but not the least, the study focuses on developing economy, particularly, Africa and Ghana to be precise. This will widen the range of empirical inquiries on training and the resultant benefits, which have mainly focused on European, American, and Asian contexts (Haryono et al., Citation2020; Lyons, Citation2020; Sheeba & Christopher, Citation2020). It is innovative to focus on the public sector of Ghana, particularly because performance studies have gradually begin to shift toward research in developing economies, including those in Africa (Bonsu et al., Citation2022; Mohammed et al., Citation2023; Sakyiwaa et al., Citation2020). For example, from the few studies from an African perspective (Olonade et al., Citation2020; Nsazi, 2013), the case of Ghana remains gray; hence, there is a need for more studies to fill this void in the literature.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The second section presents the theoretical background and hypothesis development. The third section covers the method; data employed, and study design. The fourth section also presents the analysis of the data employed whereas the fifth section discusses the empirical findings. The sixth section presents the conclusions and implications of the study, and the final section highlights the limitations and future directions of the study.

2. Theory and hypothesis

Social cognitive theory posits that people take part in intentional influence over their inspiration and that whatever a person does in life is dictated by this intentional influence (Bandura, Citation2015). The theory, therefore, argues that in every human institution, self-efficacy convictions are the focal instrument; they are conceived to affect everything from inspiration to a fulfilled life (Bandura, Citation2015). Bandura (Citation2015) further argued that if people are not convinced that they can accomplish the behavior required to achieve an expected goal, they would not participate in that behavior or would exert very little effort. Social cognitive theory suggests that people are more productive when they are motivated, which happens when they are convinced that they can participate in the behaviors required to attain their goals. Specifically, according to social cognitive theory, people with greater self-efficacy are bound to accept goals, set progressively more complex goals, and persevere on goals during challenges. These procedures, at that point, result in improved performance (Bandura & Locke, Citation2003; Locke & Latham, Citation1990). Anytime a person has an ambition, he is inspired to go through the necessary process, irrespective of the obstacles, to accomplish such ambitions. As indicated by Baron and Kenny (Citation1986), because people perform well on their tasks because of their motivation to achieve their set goals, goals act partially as mediators.

Although most studies and theories on self-efficacy usually concentrate on its positive impact, Bandura (Citation2015) opines that in an introductory setting, self-efficacy may negatively affect job productivity. In a preliminary context, Bandura (Citation2015) posited that self-doubt may not be bad. For instance, in a discussion on athletes, he noted that an athlete who sees him/her to be very effective in his abilities does not have much motivation to devote a lot of effort to tiresome preparatory practice in learning tasks. In this case, the level of doubt undoubtedly aids training. Hence, he opines that when people have great self-efficacy, they might not exert effort in preparation for a future task, because they are convinced that they have what it takes to succeed. Social cognitive theory postulates that self-efficacy is the fundamental instrument responsible for people’s motivation, productivity, and fulfillment in life (Bandura, Citation2015). That is to say, despite all the training that employees may receive, if they are not motivated by their inspiration to fulfill certain things in life that are connected to their role, training will not result in the expected outcome (performance). Although, overall, the theory concentrates on the positive impact of self-efficacy, there is some uncertainty regarding the role played by self-efficacy in overall performance.

2.1. Training and job performance

Training is a significant element in improving a firm’s human capital, capabilities, and organizational knowledge, thus strengthening its competitive advantage (Febrian et al., Citation2016; Gyimah et al., Citation2020; Idris et al., Citation2020). According to Dessler (Citation2006), training improves current and future job performance, as well as activities that serve to improve job performance. There are several ways to improve job performance, including by providing work training to employees (Haryono et al., Citation2020). Some previous scholars (including Nyaisu et al., Citation2017) conclude that training employees has a positive effect on staff job performance. This viewpoint stems from the goal-setting theory, which suggests that a minute a difficult task is given, the only rational course of action is to attempt and keep at it until it is accomplished, leading to performance (task, adaptive, and contextual). Bandura and Cervone (Citation1986) stress that goals perform a stimulating function, as they lead to better performance. Again, as observed by Smith et al. (Citation1990), if the task for which a goal is allocated is new to the individual in charge of accomplishing it, they would carefully plan to design strategies that would aid them in achieving their goals. Universities are mainly formal and thrive in employee training to improve performance. For non-teaching staff of universities to perform better, they need to be trained to achieve a competitive advantage. Therefore, this study hypothesizes the following:

: Training practices have a significant positive effect on employee performance

2.2. The direct and mediating roles of self-efficacy

As recognized by social cognitive theory, a strong sense of self-efficacy encourages the achievement of personal goals. People with high levels of certainty can handle challenging tasks and critical challenges. Self-efficacy makes people design challenging goals, stick to them, be more prepared to face failure, and regain their motivation after each situation (Bandura, Citation2012). In addition, self-efficacy helps address various phenomena such as changes in behavior, level of reactions, despair, and failure (Bandura, Citation2015). Self-efficacy is a significant variable that mediates the effect of dispositional variables on learning performance (Lazzara et al., Citation2021). It is likely that people already possess self-efficacy before entering a program or gain it in the course of training (Salas & Cannon-Bowers, Citation2001). Haccoun and Saks (Citation1998) suggested that training boosts self-efficacy while self-efficacy mediates the impact of training on training results.

Post-training self-efficacy plays two roles. First, it makes people to ponder about their learning outcomes and arrive at the conclusion that they are “able to do”; and secondly, this knowledge serves as motivation to increase a person’s readiness to perform (willingness to do). While Haccoun and Saks (Citation1998) take a positive stance on the likelihood that training programme designs might essentially result in decreasing self-efficacy. This is significant because the structure of the training program (content and assimilation difficulty) affects a person’s level of self-efficacy, with effects on the application of training. If the content of the training enables the attainment of knowledge, this increases self-efficacy levels and, as such, a positive effect on the application of training is possible. Individual-level variables (e.g., cognitive ability) play a role in self-efficacy of people (Bandura, Citation2012). Nevertheless, this study argues that self-efficacy encompasses the effects of these factors. Consequently, post-training self-efficacy is per the purposes of this study is defined as people’s perceived capacity to act as set by the training program. Self-efficacy is essential to the learning and development profession because available data demonstrate that it is connected to people’s performance (Guerra et al., Citation2022). Subsequently, self-efficacy has aided individuals in learning many new behaviors and an array of work-related skills. For instance, research indicates that self-efficacy expectations influence salesforce performance, academic research performance, workers’ attendance at work, enlisting people’s achievement in fundamental training, and managers’ decision-making capabilities (Lyons & Bandura, Citation2022).

Empirically, Canrinus et al. (Citation2012) explored the connections between self-efficacy, work fulfilment, motivation, and commitment among teachers. The authors concentrated on how relevant indicators of teachers’ perceptions of professional identity (work fulfilment, commitment to work, self-efficacy, and alterations in level of motivation) are connected. Based on their analysis, they argue that classroom self-efficacy and relationship fulfilment play a major role in influencing the connections between these factors. Tojjari et al. (Citation2013) also in their studies analyzed the impact of self-efficacy on job satisfaction and performance in sports referees in Iran. Their study demonstrated that the general self-efficacy of sport referees has a significant influence on the intrinsic and extrinsic features of job satisfaction. While this effect is not significant for general factors of job satisfaction, it had an impact on their performance. In another study based on social cognitive theory, Salman et al. (Citation2016) investigated the effect of self-efficacy on workers’ job performance in Pakistan’s health sector and revealed that self-efficacy has a strong connection with job performance factors, such as job commitment, job satisfaction, and absenteeism. Hence, the second hypothesis of this study is as follows:

: Self-efficacy has a significant positive effect on employee performance

: Self-efficacy positively mediates the relationship between training practices and employee performance

2.3. Moderating role of perceived organisational politics

Politics in an organization represent machinations of personal interest that fit well with the concept of the social market (Khan & Chaudhary, Citation2023). The perception of organizational politics depends on an individual’s awareness of politics and reactions (Cooper-Thomas & Morrison, Citation2018). Organizational politics should not be understood as a concept that is only harmful and can undermine the organization’s ability to operate (Khan & Chaudhary, Citation2023). Thus, managers must make decisions and implement new methods to mitigate the adverse effects of politics in the organization. Perceived organizational politics can negatively impact job performance outcomes when employees believe that their work environment does not support them (Noori et al., Citation2022). Hence, the political climate perceived by members may cause a significant difference in the responses of employees toward their role in the organization (Awaah, Citation2023). Therefore, when individuals in an organization perceive the environment to be negative, they can reduce resources, actions, effective organizational change, job performance, and trust among managers and employees (Zhang et al., Citation2019).

In Ghana, organizational politics can take various forms, such as favoritism, power struggles, and the manipulation of information and resources (Awaah, Citation2023). These political behaviors can have a significant impact on employee attitudes towards training and job performance (Zhang et al., Citation2019). When employees perceive that promotions, rewards, and opportunities for growth are based on factors other than merit and performance, it can create a sense of unfairness and demotivation (Awaah, Citation2023). Additionally, organizational politics can create a culture of distrust and competition among employees (Akoto et al., Citation2022; Horsey et al., Citation2023). This may lead to a lack of enthusiasm for training initiatives and a decrease in job performance (Noori et al., Citation2022).

The literature has indicated that there is a negative relationship between organizational politics, performance, and satisfaction (Noori et al., Citation2022) as well as loyalty (Riaz et al., Citation2023). Specifically, a review of the literature indicates that the relationship between self-efficacy and job performance is based on the mechanistic condition of perceived organizational politics (Salman et al., Citation2016 and Tojjari et al., Citation2013). Therefore, there is a relationship between self-efficacy and job performance based on perceived organisational politics. Thus, the negative organizational politics perceived by an individual leads to less self-efficacy and decreases organizational attractiveness to encourage appropriate input (Jabbar et al., Citation2020). Therefore, the third hypothesis of this study is as follows:

: Perceived organisational politics moderate the role of self-efficacy in the relationship between training and job performance.

3. Methods

3.1. Study context and setting

The non-teaching staff of public universities in Kumasi, the second-largest city in Ghana, are selected to test our hypothesized model specified above. There are three (3) public universities: Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Akenten Appiah-Menka University of Skill Training and Entrepreneurial Development (AAMUSTED), and Kumasi Technical University (KTU). KNUST is the first and largest public tertiary institution in Kumasi, the entire Ashanti region, and the second oldest institution in Ghana. KNUST was established in 1951 as the Kumasi College of Technology, with the chancellor, chairman of the university council, and the vice-chancellor as the main leaders of the institution. The Akenten Appiah-Menka University of Skills Training and Entrepreneurial Development (AAMUSTED), was established on August 27, 2020, under Act 1026 of 2020 of the Parliament of the Republic of Ghana. AAMUSTED was formed from the College of Technology Education, Kumasi (COLTEK) and the College of Agriculture Education (CAGRIC), Asante-Mampong, which are campuses of the University of Education, Winneba. The University traces its history to the evolution of COLTEK and CAGRIC. COLTEK started as a Technical Teachers College (TTC) in 1966 and later metamorphosed into the Kumasi Advanced Technical Teachers College (KATTC) in 1978. Kumasi Technical University was founded in 1954 as the Kumasi Technical Institute and later promoted to a non-tertiary polytechnic rank under the Ghana Education Service. The Technical University Act 2016 (Act 1992) upgraded the former Kumasi Polytechnic to the present Kumasi Technical University. The university has a mission to be a center of experience for technological and entrepreneurial development.

There are two broad categories of staff in each of the selected institutions: teaching and non-teaching staff. While the teaching staff are mainly involved in academic work, the non-teaching staff ensure day-to-day administration and management of the university. Administrative and management issues such as staff and student welfare matters, employment and recruitment, and the like are some of the key tasks of university non-teaching staff (Sarpong-Danquah et al., Citation2018). The study population includes non-teaching staff of public universities in the Ashanti Region. According to the records of the three selected institutions, there is a total of 1816 non-teaching staff at the time the inquiries are made. The study includes non-teaching staff within lower-level and middle-level management positions in the study institutions across gender.

3.2. Study design and sample

The study uses cross-sectional survey data gathered through a questionnaire and employed both descriptive and inferential study designs for the analysis. Specifically, the study design is chosen to help establish the relationship between three variables: training, performance, self-efficacy, and perceived organizational politics (Sarantakos, Citation2005). To determine the representative sample size from the three institutions, the Krejcie and Morgan (Citation1970) sample size determination formula is utilized and applied to each campus center. Krejcie and Morgan’s (Citation1970) sample size determination is as follows:

(1)

(1)

where s = required sample size;

= the table value of chi-square for one level of freedom at the desired confidence level (3.841); N = the population size; P = the population proportion (assumed to be 0.50, since this will give the maximum sample size); and d is the degree of accuracy expressed as a proportion (0.05).

After computations, the sample sizes for the respective campus centers are as follows: KNUST (767), AAMUSTED (415), and KTU (166), making a total sample size of 936. In applying a sampling technique to enhance representatives, the researcher adopted a proportionate sampling technique to determine the proportion of non-teaching staff at each study institution. The proportionate sampling technique is given by

After obtaining the sample for each stratum, a systematic sampling technique was employed to identify respondents from a sampling frame (register). In doing so, the systematic sampling technique formula, , is used to arrive at the kth term.

After administering questionnaires to all 936 sampled participants from the three selected intuitions, 370 successfully filled questionnaires are retrieved after several follow-ups and visits. This represents an approximately 40% response rate, which is quite good for an empirical study of this nature. presents the demographics of the data based on which we justify that the sample size is representative of the non-teaching staff of public universities in Ghana. Hence, the study can make generalizations based on the findings.

Table 1. Demographic profile of respondents.

3.3. Measurement of variable

The study uses prevailing tested and validated questionnaires in the literature such as Awaah (Citation2023), Horsey et al. (Citation2023), Hochwarter et al. (Citation2003), Kirkpatrick (Citation1996), Pradhan and Jena (Citation2017), and Noori et al. (Citation2022). All items on the questionnaire are closed-ended, with the exception of section A (respondents’ demographics features) which collected nominal data. All other items on training, organizational politics, self-efficacy, job performance, and the control variables are ordinal data measured on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). The construct column in provides the items of each variable.

Table 2. Reliability and validity tests.

3.4. Reliability and validity measurement

Composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha reliability tests are employed in this study to estimate the consistency (reliability) of the instruments (Nkukpornu et al., Citation2020). A Cronbach’s alpha coefficient greater than 0.7, is enough to accept that the instrument is reliable and good for analysis (Hair et al., Citation2019; Jalloh et al., Citation2019). As reported in , all the factor loadings for each item are significant, ranging from 0.599 to 0.872, indicating strong convergent validity. In addition, AVE scores are generally above the threshold value of 0.5, demonstrating the validity of the instruments. Moreover, it can be observed that the composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s alpha values (CA) are also generally higher than the minimum cutoff point of 0.7, which also illustrates strong scale reliability.

Confirmatory factor analysis assessing the performance of the six factors suggests that the model provides a good fit to the data. Basing on the criterion as suggested by Kline (2004) and Hair et al. (Citation2019) that a good fit model should have a normed Chi-square (X2/df) of less than 5 as well as a comparative fit index (CFI) above 0.90; a standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) close to .04; and a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) less than 0.08, we can conclude that the model is a good fit. Again, the fitness of the sub-models in the six-factor model further emphasized the overall fitness of the model used in this study (). Thus, the model thoroughly accounts for all the dynamics and characteristics inherent in the data, and is therefore suitable for further analysis. All model fit indices for each construct exceed the standard criteria and demonstrated the adequacy of the proposed model to analyze the connection between training, self-efficacy, organizational politics, and employee performance.

Table 3. Validation of first order construct.

4. Results

Descriptive and correlation analyses (mean, standard deviation, and correlation coefficients) indicating the scope and degree of association of all the variables show that training had a significant positive relationship with self-efficacy and job performance (r = 0.139, p < 0,05; r = 0.258, p < 0.01). Although the association between training and organizational politics is positive, it is insignificant at the 5% significance level. Meanwhile, there is a significant positive association between organizational politics and job performance (r = 0.133, p < 0.05). indicates that it is possible to test the hypotheses (H1 – H3).

Table 4. Descriptive and correlation analysis.

4.1. Baseline (direct) SEM regression results

presents the estimates of the effect of training and self-efficacy and organizational politics on three indicators (task, contextual, and adaptive) of performance under each of the three models: (1), (2), and (3). There is a significant positive effect of training on adaptive performance (β = β = .24, p < 1%), as observed in model (3). However, the results reveal that there is no statistically significant relationship between training and task and contextual performance, as reported by models (1) and (2). Concerning the effect of organizational politics, there is a positive significant effect on task and contextual performance at 1% and 5% (β = .141, p < 1%, β = .08, p < 5%), respectively. Therefore, it can be conclude that organizational politics are relevant for increasing both task and contextual performance. On the contrary, there is no indication that organizational politics has an effect on employees’ adaptive performance, even at the 10% significance level, as observed in model (3) [β = -.006, p > 10%]. However, for the relationship between self-efficacy and job performance, all results from the three models indicated a significant positive relationship at the 1% significance level. Thus, self-efficacy generally improves employee performance.

Table 5. SEM regression analysis.

4.2. Mediation—moderation results

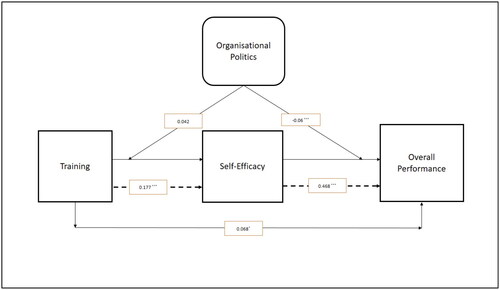

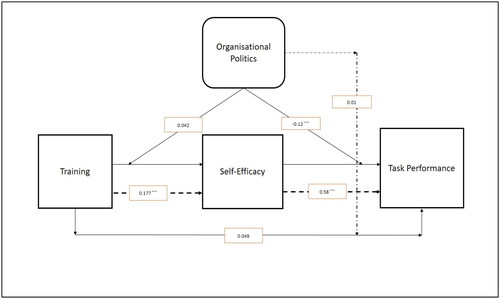

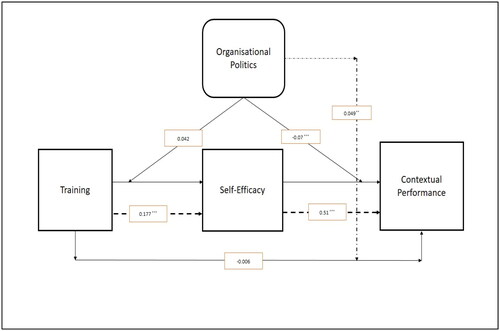

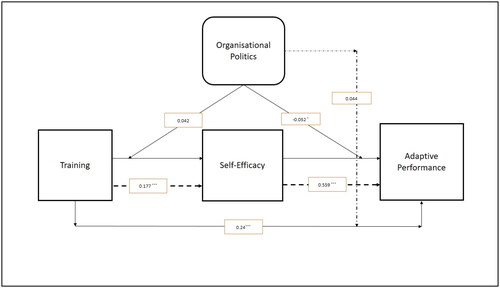

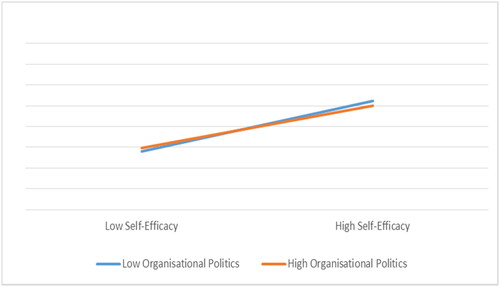

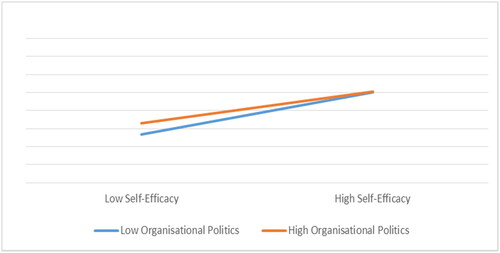

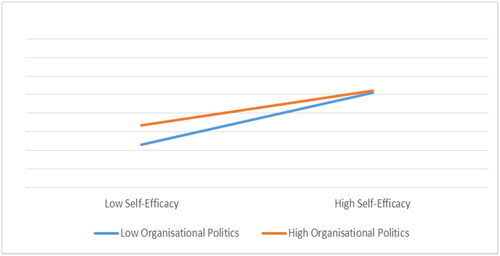

This study further investigates whether organizational politics moderated the effect of training and self-efficacy on performance. The results from Model (1) indicate that organizational politics moderates the effect of self-efficacy on task performance (β = −.012, p < 1%), but not the relationship between training and task performance (β = .01, p > 10%, ns). In Model (2), the effects of both training (β = .049, p < 5%) and self-efficacy (β = −.07, p < 1%) on contextual performance are moderated by organizational politics. On the other hand, Model (3) reports that the interaction of organizational politics and training (β = −.044, p > 10%, ns) does not have any statistical effect on adaptive performance. In contrast, the results show that the interaction between organizational politics and self-efficacy (β = −.052, p < 10%) has a small but significant negative effect on adaptive performance (). show a graphical representation of these relationships.

Figure 2. Path Diagram of the Effect of Training, Self-Efficacy and Organisational Politics on Overall Performance.

Figure 3. Path Diagram of the Effect of Training, Self-Efficacy and Organisational Politics on Task Performance.

Figure 4. Path Diagram of the Effect of Training, Self-Efficacy and Organisational Politics on Contextual Performance.

Figure 5. Path Diagram of the Effect of Training, Self-Efficacy and Organisational Politics on Adaptive Performance.

The mediating role of self-efficacy in the relationship between training and performance measures is then examined with and without the moderating effect of organizational politics. It can be observes from that self-efficacy mediates the effects of training on adaptive, task, and contextual performance. The nature of the mediation effect is identified to be full with the training-task and training-contextual performance relationships but partially mediates the effect of training on adaptive performance (0.10, 95% bias-corrected CI [0.024 0.170], 0.11 at a 95% bias-corrected CI [0.027 0.178], -0.091 at a 95% bias-corrected CI [-0.159 -0 .024], respectively). There is no indication that self-efficacy mediates the effect of organizational politics on performance measures. Focusing on the moderated mediation effect of self-efficacy, it can be observed that controlling for the effect of organizational politics does not instigate any significant change in the mediating role of self-efficacy. Thus, organizational politics do not moderate the mediation effect of self-efficacy on the relationship between training and performance measures. presentthe plot of the moderation effect of training and self-efficacy on performance measures at various levels of organizational performance.

Figure 6. Plot of the Moderation of Organisational Politics on Self-Efficacy – Adaptive Performance Relationship.

Figure 7. Plot of the Moderation of Organisational Politics on Self-Efficacy – Contextual Performance Relationship.

Figure 8. Plot of the Moderation of Organisational Politics on Self-Efficacy – Task Performance Relationship.

Figure 9. Plot of the Moderation of Organisational Politics on Training – Adaptive Performance Relationship.

Table 6. Mediating effect of self-efficacy (indirect effect).

5. Discussion of findings

The findings from the direct regression results indicate that training had a significant positive effect on adaptive performance against task and contextual performance. This implies that an enhancement in the training programs for the university staff, particularly non-teaching staff, and increases the capacity of the staff to adapt to conditions within the working environment rather than enabling them to improve their task and contextual performance. Based on this result, hypothesis is supported. This finding is in line with Wamwayi et al. (Citation2016), who find that training needs appraisal, length of training, training method, and training feedback positively affect the productivity of non-teaching employees in their study of public universities in Kenya. In other words, for universities to improve the productivity of their staff in order to gain competitive advantage, training programs should be highly considered in any decision aimed at driving changes and modifications in the structure and process of business at universities. According to the literature, a fast-paced digital world requires employees to have the knowledge, skills, and capabilities required to adapt to new processes and production methods. Through training, the findings of this study suggest that non-teaching staff will be able to acquire the capabilities needed to fuel their drive to adapt and use new processes and systems within the university environment.

Regarding the mediating role of self-efficacy in the relationship between training practices and job performance, the results indicate that the nature of the mediating role of self-efficacy is dependent on the dimension of performance under investigation. Concerning the impact of training on adaptive performance, the findings of this study suggest partial mediation of self-efficacy. However, for task and contextual performance indicators, the results of this study suggest that self-efficacy fully mediates the effect of training on task performance. This implies that training can only lead to higher task and contextual performance because there is a resultant increment in the self-efficacy of the non-teaching staff. This confirms the findings of Haccoun and Saks (Citation1998), which conclude a similar mediating effect of self-efficacy on the relationship between training and employee performance. The findings further indicate that a higher level of self-efficacy is required to improve task, contextual, and adaptive performance; thus, hypotheses and

are all supported. Again, Tojjari et al. (Citation2013) report that the self-efficacy of sports referees is a significant contributor to the intrinsic and extrinsic elements of job satisfaction. Workers with high self-efficacy usually work hard to learn how to carry out new tasks because they are sure that their hard work will be successful. On the other hand, workers with low self-efficacy might exert less effort to learn and perform complex tasks because they are unsure that their efforts would be successful.

We observe that organizational politics do not have a statistically significant positive effect on task and contextual performance, but not on adaptive performance. Notwithstanding this mixed effect, evidence indicates that it negatively moderates the effect of self-efficacy on task, contextual, and adaptive performance. Thus, , which states that the path from self-efficacy to performance outcomes is leveraged by organizational politics, is strongly supported. However, this study did not find any evidence that organizational politics moderated the effect of training on self-efficacy.

However, we find that the effect of training on contextual performance can be moderated by the existence of organizational politics. This result therefore demonstrates the varied effect of organizational politics at the workplace and is indicative of the fact that stakeholders handle organizational politics with some level of circumspection and tone; the mixed findings concord with the study by Ugwu et al. (Citation2014), who argue that bad political behavior negatively influences the productivity of workers and decreases overall organizational productivity, while great political behavior positively influences the performance of workers and raises organizational productivity. In addition, Abbas and Raja (Citation2014) and Vigoda-Gadot (2007) report that the perception of organizational politics has a mixed effect on performance.

6. Conclusion and implications

6.1. Conclusion

This study aims to examine the role that self-efficacy plays in enhancing the benefit of training on employees’ job performance in the organization. Additionally, the study further investigates how organizational politics influences self-efficacy in its mediation role in the relationship between training and job performance. The structural equation modeling technique is employed to analyze the data with the help of a survey questionnaire from 370 non-teaching staff of public universities in Kumasi, Ghana, which are randomly sampled. We suggest that job training practices can influence employee performance due to the resultant improvement in self-efficacy. This work highlights that training on its own does not necessarily result in an increment in the job performance of non-teaching staff, unless self-efficacy is actualized or boosted.

6.2. Theoretical implications

Theoretically, the current study has pointed out the heterogeneous effect of organizational politics and how an uncontrolled political climate within the workplace can be harmful to employees’ self-efficacy and extending their performance on the job. On its own, organizational politics is identified as a boosting task and contextual performance; however, it minimizes the effect of self-efficacy on task and contextual performance. Therefore, it can produce net harm or benefit depending on the direct effect size on performance measures (particularly task and contextual performance). This calls for circumspection of the extent to which politics are practiced and encouraged at the workplace, particularly among non-teaching staff. Furthermore, the study highlighted the significance of training in boosting the adaptive performance of non-teaching staff. This emphasizes the critical role that training plays in managing change and motivating employees to take up new challenges and improve the status quo in the workplace. The study therefore theorizes that training targeted at improving skills, competence, and instilling a sense of self-belief among workers is vital for improving employee performance.

6.3. Practical and managerial implications

Our findings have the following implications for management and practice. First, there is a need for managers (university management) to periodically build workers’ capacity to improve their level of self-efficacy. Based on the result that training increases self-efficacy, which enhances work outcomes, we again recommend that human resource managers concentrate on training regimes that not only improve the task capacity of the working staff, but also build their level of self-efficacy. In this regard, training that requires mentorship and coaching or job training is recommended compared with training through symposiums and conferences. Through coaching or mentoring, workers receive advice and support from supervisors, which is likely to enhance self-efficacy. Finally, employers must put systems and measures in place to balance the level of politics in the workplace. Politics itself is not a bad thing; the problem is that when it is unchecked, it negatively impacts employees’ output, which may accumulate and jeopardize work outcomes. There is a need for authorities to handle organizational politics at some level of circumspection and tact. Therefore, it is important for every political maneuver to be regulated.

7. Limitation and further studies

This study had some limitations that need to be acknowledged. The first issue to recognize as far as the limitations of the study are concerned is the complexity of job performance. Job performance is complex, multi-faceted, and underpinned by several variables; the researcher concentrates on only two mainstream variables directly related to the research problem and topic under study. Again, the use of only closed-ended items in collecting the data made it impossible for respondents to provide unsolicited responses. Moreover, although the use of triangulation in collecting research data significantly improves the validity of the data, questionnaires are the only instrument used to collect data. Future studies can take the opportunity and include more variables that may affect job performance and examine their relationship. Furthermore, future studies can take advantage of triangulation in data collection by including other designs, such as interviews and other qualitative means, in addition to the quantitative design employed in the current study.

Author’s contributions

Claudia Omari Somuah: Collected the responses for analysis; data analysis or perform the analysis, and draft the paper. Henry Kofi Mensah: Conceived the research idea, supervised and validate the analysis. Prince Gyimah: Designed the analysis, revised the paper, and supervised.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data availability statement will be made available on request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Claudia Omari Somuah

Claudia Omari Somuah is a PhD student at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. She is an Assistant Registrar and a part-time lecturer at the Akenten Appiah-Menkah University of Skills Training and Entrepreneurial Development. Her research interests are in Human Relations, Organizational Development and Socially responsible HRM.

Henry Kofi Mensah

Henry Kofi Mensah holds a PhD in Organizational Development from the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST). Henry is an Associate Professor of Management at KNUST, and has over 10 years’ experience in teaching and researching Organizational Behaviour, Business Sustainability, Responsible Management and Small Business Strategy.

Prince Gyimah

Prince Gyimah is a Lecturer at the Department of Accounting Studies Education, Akenten Appiah-Menka University of Skills Training and Entrepreneurial Development, Ghana. He received his PhD in Accounting from Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, and is actively involved in research covering the areas of accounting, business, or management.

References

- Abbas, M., & Raja, U. (2014). Impact of perceived organizational politics on supervisory-rated innovative performance and job stress: Evidence from Pakistan. Journal of Advanced Management Science, 2(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.12720/joams.2.2.158-162

- Abu-Tineh, A. M., Romanowski, M. H., Chaaban, Y., Alkhatib, H., Ghamrawi, N., & Alshaboul, Y. M. (2023). Career advancement, job satisfaction, career retention, and other related dimensions for sustainability: A perception study of Qatari public school Teachers. Sustainability, 15(5), 4370. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054370

- Ahmad, J., Akhtar, H. M. W., Rahman, H., & Muhammad, R. (2017). Effect of diversified model of organizational politics on diversified emotional intelligence. Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 13, 375–385.

- Akoto, E., Owusu, E., Gyimah, P., Acheampong, A., & Adu-Brobbey, V, Henderson State University, USA. (2022). Cultural profile as determinant of work outcomes in a collectivist context. Journal of Global Awareness, 3(2), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.24073/jga/3/02/07

- Awaah, F. (2023). Does organisational politics moderates the relationship between organisational culture and employee efficiency? Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences, forthcoming. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEAS-12-2022-0264

- Bandura, A. (2012). On the functional properties of perceived self-efficacy revisited. Journal of Management, 38(1), 9–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311410606

- Bandura, A. (2015). On deconstructing commentaries regarding alternative theories of self-regulation. Journal of Management, 41(4), 1025–1044. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315572826

- Bandura, A., & Cervone, D. (1986). Differential engagement of self-reactive influences in cognitive motivation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 38(1), 92–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(86)90028-2

- Bandura, A., & Locke, E. A. (2003). Negative self-efficacy and goal effects revisited. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.1.87

- Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (2001). Self‐efficacy beliefs as shapers of children’s aspirations and career trajectories. Child Development, 72(1), 187–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00273

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Bonsu, A. B., Appiah, K. O., Gyimah, P., & Owusu-Afriyie, R. (2022). Public sector accountability: do leadership practices, integrity and internal control systems matter? IIM Ranchi Journal of Management Studies, 2(1), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/IRJMS-02-2022-0010

- Bukhari, I., & Kamal, A. (2015). Relationship between perceived organizational politics and its negative outcomes: Moderating role of perceived organizational support. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 30(2), 271–288.

- Canrinus, E. T., Helms-Lorenz, M., Beijaard, D., Buitink, J., & Hofman, A. (2012). Self-efficacy, job satisfaction, motivation and commitment: Exploring the relationships between indicators of teachers’ professional identity. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 27(1), 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-011-0069-2

- Carter, W. R., Nesbit, P. L., Badham, R. J., Parker, S. K., & Sung, L. K. (2018). The effects of employee engagement and self-efficacy on job performance: A longitudinal field study. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(17), 2483–2502. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1244096

- Chatterjee, S., Chaudhuri, R., Vrontis, D., & Giovando, G. (2023). Digital workplace and organization performance: Moderating role of digital leadership capability. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 8(1), 100334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2023.100334

- Chiaburu, D. S., & Lindsay, D. R. (2008). Can do or will do? The importance of self-efficacy and instrumentality for training transfer. Human Resource Development International, 11(2), 199–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678860801933004

- Cooper-Thomas, H. D., & Morrison, R. L. (2018). Give and take: Needed updates to social exchange theory. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 11(3), 493–498. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2018.101

- Dessler, G. (2006). A framework for human resource management: Pearson Education India.

- Febrian, F. K., Maarif, S., & Hubeis, A. (2016). The role of leadership, motivation and training on employee performance in PT XYZ. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 6(8), 119–125.

- Ferris, G. R., Bhawuk, D. P., Fedor, D. F., & Judge, T. A. (2018). Organizational politics and citizenship: Attributions of intentionality and construct definition. In Attribution theory (pp. 231–252). Routledge.

- Garavan, T., McCarthy, A., Lai, Y., Murphy, K., Sheehan, M., & Carbery, R. (2021). Training and organisational performance: A meta‐analysis of temporal, institutional and organisational context moderators. Human Resource Management Journal, 31(1), 93–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12284

- Grossman, R., & Salas, E. (2011). The transfer of training: what really matters. International Journal of Training and Development, 15(2), 103–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2419.2011.00373.x

- Guerra, R., Bierwiaczonek, K., Ferreira, M., Golec de Zavala, A., Abakoumkin, G., Wildschut, T., & Sedikides, C. (2022). An intergroup approach to collective narcissism: Intergroup threats and hostility in four European Union countries. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 25(2), 415–433. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430220972178

- Gyimah, P., Appiah, K. O., & Appiagyei, K. (2023). Seven years of United Nations’ sustainable development goals in Africa: A bibliometric and systematic methodological review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 395, 136422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136422

- Gyimah, P., Appiah, K. O., & Lussier, R. N. (2020). Success versus failure prediction model for small businesses in Ghana. Journal of African Business, 21(2), 215–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2019.1625017

- Gyimah, P., Otoo, J. A., Zoiku, S., & Krapah, E. O. (2022). Nexus between the COSO framework and the effectiveness of internal control systems: Public universities’ perspectives. Euro Med J. of Management, 4(4), 315–331. https://doi.org/10.1504/EMJM.2022.127445

- Haccoun, R. R., & Saks, A. M. (1998). Training in the 21st century: Some lessons from the last one. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 39(1-2), 33–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0086793

- Hair, J. F., Page, M., & Brunsveld, N. (2019). Essentials of business research methods. Routledge.

- Halawi, A., & Haydar, N. (2018). Effects of training on employee performance: A case study of Bonjus and Khatib and Alami Companies. International Humanities Studies, 5(2), 24–45.

- Haryono, S., Supardi, S., & Udin, U. (2020). The effect of training and job promotion on work motivation and its implications on job performance: Evidence from Indonesia. Management Science Letters, 10(9), 2107–2112. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2020.1.019

- Hochwarter, W. A., Kacmar, C., Perrewé, P. L., & Johnson, D. (2003). Perceived organizational support as a mediator of the relationship between politics perceptions and work outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 63(3), 438–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00048-9

- Horsey, E. M., Guo, L., & Huang, J. (2023). Ethical party culture, control, and citizenship behavior: Evidence from Ghana. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01698-8

- Idris, I., Adi, K. R., Soetjipto, B. E., & Supriyanto, A. S. (2020). The mediating role of job satisfaction on compensation, work environment, and employee performance: Evidence from Indonesia. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 8(2), 735–750. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2020.8.2(44)

- Jabbar, H., Chanin, J., Haynes, J., & Slaughter, S. (2020). Teacher power and the politics of union organizing in the charter sector. Educational Policy, 34(1), 211–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904819881776

- Jalloh, B. M. Y., Appiah, K. O., & Gyimah, P. (2019). Does gender affect loan default? EuroMed J. of Management, 3(1), 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1504/EMJM.2019.099956

- Kacmar, K. M., & Baron, R. A. (1999). Organizational politics. Research in Human Resources Management, 1, 1–39.

- Kanapathipillai, K., & Azam, S. F. (2020). The impact of employee training programs on job performance and job satisfaction in the telecommunication companies in Malaysia. European Journal of Human Resource Management Studies, 4(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.46827/ejhrms.v4i3.857

- Khan, A., & Chaudhary, R. (2023). Perceived organizational politics and workplace gossip: the moderating role of compassion. International Journal of Conflict Management, 34(2), 392–416. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCMA-07-2022-0121

- Kirkpatrick, D. (1996). Revisiting Kirkpatrick’s four-level model. Training and Development, 50(1), 54–57.

- Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), 607–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447003000308

- Lazzara, E. H., Benishek, L. E., Hughes, A. M., Zajac, S., Spencer, J. M., Heyne, K. B., Rogers, J. E., & Salas, E. (2021). Enhancing the organization’s workforce: Guidance for effective training sustainment. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 73(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpb0000185

- Lin, C. Y., & Huang, C. K. (2021). Employee turnover intentions and job performance from a planned change: the effects of an organizational learning culture and job satisfaction. International Journal of Manpower, 42(3), 409–423. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-08-2018-0281

- Lin, S. R., & Hsu, C. C. (2017). A study of impact on-job training on job performance of employees in catering industry. International Journal of Organizational Innovation, 9(3), 125A.

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting and task performance. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Lyons, E. (2020). The impact of job training on temporary worker performance: Field experimental evidence from insurance sales agents. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 29(1), 122–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/jems.12333

- Lyons, P., & Bandura, R. (2022). Coaching to enhance learning and engagement and reduce turnover. Journal of Workplace Learning, 34(1), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWL-04-2021-0037

- Mangkunegara, A. P. (2021). The role of transformational leadership in building work engagement and performance of business company managers. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 24, 1–19.

- Mangkunegara, A. P., & Agustine, R. (2016). Effect of training, motivation and work environment on physicians’ performance. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 5(1), 173–188. https://doi.org/10.5901/ajis.2016.v5n1p173

- Mohammed, M., Gyimah, P., & Adisa, I. (2023). Drivers and challenges of social media usage in Ghana’s local government administration. In Public sector marketing communications, volume ii: traditional and digital perspectives (pp. 131–153). Springer International Publishing.

- Nkukpornu, E., Gyimah, P., & Sakyiwaa, L. (2020). Behavioural finance and investment decisions: does behavioral bias matter. International Business Research, 13(11), 65. https://doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v13n11p65

- Noori, R., Shoaib, S., & Mujtaba, B. G. (2022). Antecedents and consequences of perception of organizational politics: Empirical evidence for public sector universities in Eastern Afghanistan. Public Organization Review, 23(4), 1477–1503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-022-00685-y

- Nyaisu, A., Muya, J., & Ngacho, C. (2017). The influence of employee training implementation on job performance: A case of the non-teaching staff of the University of Kabianga, Kenya. International Journal of Social Science and Information Technology, 3(5), 2138–2146.

- Olonade, Z. O., Ajibola, K. S., & Omotoye, O. O. (2020). Antecedents of perceived job commitment among employees of local government in Ilesha metropolis. Quest Journal of Management and Social Sciences, 2(2), 225–239. https://doi.org/10.3126/qjmss.v2i2.33272

- Park, S., Kang, H. S., & Kim, E. J. (2018). The role of supervisor support on employees’ training and job performance: an empirical study. European Journal of Training and Development, 42(1/2), 57–74. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-06-2017-0054

- Pradhan, R. K., & Jena, L. K. (2017). Employee performance at workplace: Conceptual model and empirical validation. Business Perspectives and Research, 5(1), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/2278533716671630

- Riaz, A., Jamil, S. A., & Mahmood, S. (2023). Organizational politics and affective commitment of expatriates: Moderating role of Islamic work ethics. Asian Journal of Business Ethics, 12(2), 419-439.

- Sakyiwaa, L., Gyimah, P., & Nkukpornu, E. (2020). Preferred investment vehicles of salaried workers of universities in Sub-Saharan Africa. EuroMed J. of Management, 3(3/4), 288–305. https://doi.org/10.1504/EMJM.2020.113091

- Salas, E., & Cannon-Bowers, J. A. (2001). The science of training: A decade of progress. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 471–499. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.471

- Salman, M., Khan, M. N., Draz, U., Iqbal, M. J., & Aslam, K. (2016). Impact of self-efficacy on employee’s job performance in health sector of Pakistan. American Journal of Bossiness and Society, 1(3), 136–142.

- Sarantakos, S. (2005). Social research (Third Edition). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sarpong-Danquah, B., Gyimah, P., Poku, K., & Osei-Poku, B. (2018). Financial literacy assessment on tertiary students in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Ghanaian perspective. International Journal of Accounting and Financial Reporting, 8(2), 76–91. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijafr.v8i2.12928

- Sheeba, M. J., & Christopher, P. B. (2020). Exploring the role of training and development in creating innovative work behaviors and accomplishing non-routine cognitive jobs for organizational effectiveness. Journal of Critical Reviews, 7(4), 263–267.

- Showkat, S., Wani, T., & Kaur, J. (2023). “New Normal” implications for global talent in the wake of economic nationalism and slowdown. Thunderbird International Business Review, 65(1), 161–175. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.22270

- Smith, K. G., Locke, E. A., & Barry, D. (1990). Goal setting, planning, and organizational performance: An experimental simulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 46(1), 118–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(90)90025-5

- Stajkovic, A. D., Bandura, A., Locke, E. A., Lee, D., & Sergent, K. (2018). Test of three conceptual models of influence of the big five personality traits and self-efficacy on academic performance: A meta-analytic path-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 120, 238–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.08.014

- Thevanes, N., & Dirojan, T. (2018). Impact of training and job involvement on job performance. International Journal of Scientific and Management Research, 1(1), 1–10.

- Tojjari, F., Esmaeili, M. R., & Bavandpour, R. (2013). The effect of self-efficacy on job satisfaction of sport referees. European Journal of Experimental Biology, 3(2), 219–225.

- Ugwu, K. E., Ndugbu, M., & Okoroji, L. I. (2014). Organizational politics and employees’ performance in private sector investment: A comparative study of Zenith Bank Plc. and Alcon Plc. Nigeria. European Journal of Business and Management, 6(26), 103–116.

- Vigoda‐Gadot, E. (2007). Leadership style, organizational politics, and employees’ performance: An empirical examination of two competing models. Personnel Review, 36(5), 661–683. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480710773981

- Wamwayi, S. K., Iravo, M. A., Elegwa, M., & Gichuhi, A. W. (2016). Role of training needs assessment in the performance of non-teaching employees at management level in public universities in Kenya. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 6(8), 242–257.

- Yagil, D., Medler-Liraz, H., & Bichachi, R. (2023). Mindfulness and self-efficacy enhance employee performance by reducing stress. Personality and Individual Differences, 207, 112150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2023.112150

- Yang, M., Al Mamun, A., & Salameh, A. A. (2023). Leadership, capability and performance: A study among private higher education institutions in Indonesia. Heliyon, 9(1), e13026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13026

- Zhang, Q., Sun, S., Zheng, X., & Liu, W. (2019). The role of cynicism and personal traits in the organizational political climate and sustainable creativity. Sustainability, 11(1), 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010257