Abstract

This paper centers on the challenges posed by the pandemic crisis, examining the crucial organizational and strategic alignments, as well as the inherent paradoxes that are pivotal in nurturing competitiveness within the changed post-pandemic business landscape for small and medium-sized firms (SMEs). Encompassing nearly 90% of all global businesses, SMEs have a central role in driving social advance, fostering entrepreneurship, innovation, and facilitating sustainable economic development within their communities. As the recent COVID-19 pandemic crisis conveyed demanding challenges for businesses, understanding its complete impact requires a thorough appreciation of the adaptive measures and organizational changes in the new post-crisis landscape. To this end, we have conducted a systematic literature review by examining 88 published articles, proposing a tri-dimensional categorization of SME practices and behaviors based on the existing body of knowledge. The study highlights the inherent challenges erupted from the pandemic driven VUCA environment, stressing the importance of adaptability and innovation within SMEs. Effective leadership and adaptability are deemed vital for steering SMEs through external contingencies, as well as embracing digitalization, technology advancements, and governmental support. Nonetheless, further research is warranted to grasp SMEs adaptability on the post-pandemic normality, urging policymakers to prioritize innovation, networking, and international expansion.

1. Introduction

The beginning of 2020 marked a pivotal point in recent human history as the outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus that resulted in the COVID-19 pandemic, spread across the globe. This unprecedented health crisis had a profound impact on millions of citizens and businesses. In response to the new reality, governments implemented social distancing measures and mobility restrictions, leading to widespread lockdowns. These changes brought about significant disruptions in global supply chains, consumption behaviors, material shortages, increased labor costs, and the emergence of new digital-based business models (Zahra, Citation2022).

While the virological outbreak affected societies worldwide, the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic continue to reverberate within small and medium-sized firms (SMEs), which represent almost 90% of all businesses globally (Rao et al., Citation2022) and serve as economic pillars within their communities. SMEs play a crucial role in social, entrepreneurial, innovative, job creation, and sustainable development efforts (Al-Fadly, Citation2020; Terziovski, Citation2010). They hold significant importance in economic settings as they provide employment opportunities and contribute to sustainable growth and development in their communities (Hudson et al., Citation2001). Consequently, it is essential to recognize and understand the patterns exhibited by SMEs during the recent pandemic in order to develop coping mechanisms for the new post-pandemic normality that are tuned to volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) socio-economic environments.

Research in the field of SMEs acknowledges that these organizations face constraints in terms of both human and financial resources (Ayyagari et al., Citation2007). Therefore, it comes as no surprise that the external shock of the pandemic crisis had a more overwhelming effect on their processes (Simms et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, as the macroeconomic challenges posed by the pandemic affected businesses across sectors, an imbalance in competitive advantages between larger multinational firms (MNEs) and SMEs became evident (Fath et al., Citation2020). SMEs experienced a stronger crisis impact compared to their larger counterparts (Juergensen et al., Citation2020), resulting in reduced economic growth and financial recovery (Alves et al., Citation2020). However, SMEs possess enabling factors within their organizational structure and dynamic capabilities that enable them to efficiently leverage their assets and respond to external disruptions that threaten their future (Hudson et al., Citation2001). Some scholars (Beliaeva et al., Citation2020; Miocevic, Citation2021; Morgan et al., Citation2020) point to opportunity recognition, innovative orientation, and organizational ambidexterity as strategies to mitigate the challenges created by the pandemic landscape.

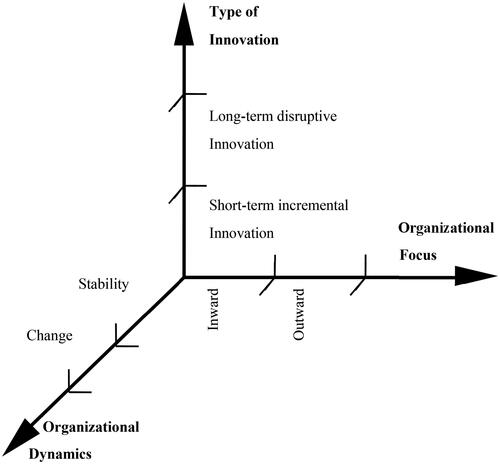

In the fiercely competitive landscape in which SMEs operate, with rapidly shrinking product cycles and constantly evolving business landscape (Ahmadi & Osman, Citation2020), influenced by the ever-changing external environment (Mäki & Toivola, Citation2021; Urbanska et al., Citation2021), the ability to adapt swiftly and strategically reconfigure competitive advantages in a VUCA environment, such as the one posed by the post-pandemic normality, becomes imperative for achieving future sustainable growth (Ahmadi & Osman, Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2021). While the pandemic crisis has sparked new research avenues on SMEs, with scholars focusing on understanding its influence on these organizations (e.g. García-Villagrán et al., Citation2020; Hussain et al., Citation2021; Kukanja et al., Citation2020; MacGregor Pelikanova et al., Citation2021), limited research is available to date that specifically addresses the challenges of adaptation and recovery in the new post-pandemic normal. Recognizing the importance of this issue, this study focuses on the challenges posed by the pandemic crisis and unveils the essential organizational patterns necessary to gain competitiveness in the new normal. To this end, we conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) on SMEs and the COVID-19 pandemic, proposing a tri-dimensional categorization of SME practices based on the literature: organizational focus, organizational dynamics, and the role of innovation.

Paradoxes are interconnected yet conflicting elements within interorganizational relationships (Smith & Lewis, Citation2011). Tensions embody the adverse aspect of organizational interactions, often involving rivalry, conflict, and predicaments (Tidström, Citation2014). Any opposing elements exhibiting interdependence can be classified as a paradox (Fortes et al., Citation2023). Paradoxes and tensions manifest at various levels within a business structure and strategy, such as cooperation vs. competition (Runge et al., Citation2022), rigidity vs. flexibility (Pressey & Vanharanta, Citation2016), and short-term vs. long-term orientation (Chou & Zolkiewski, Citation2018). As the new post-pandemic normality is highly complex and uncertain, businesses strive to manage and maintain a stability in their daily operations (McCann et al., Citation2023). However, managing these can be a dilemma. As past literature has devoted great efforts to comprehend the opposing tensions of organizational paradoxes (e.g. Ahmadi & Osman, Citation2020; Buekens, Citation2013; Fragkandreas, Citation2017), limited evidence is known regarding how SMEs are dealing with these organizational contradictions on the new VUCA macroeconomic context. Hence, we address three paradoxes that can be found throughout SMEs crisis literature: (i) change and stability; (ii) inward and outward focus; and (iii) short-term and long-term.

These chosen paradoxes capture the multifaceted challenges that SMEs face in the uncertain and disruptive post-pandemic context. The selection of each paradox was informed by the analysis of our gathered articles, in which we observed the contradictory nature of SMEs practices and response behavior amidst the pandemic-crisis, as well as the current predicaments in the new post-pandemic normality. As many authors have identified (e.g. Siahaan et al., 2022; Thorgren & Williams, Citation2020; Tan et al., Citation2022), the rapidly evolving business landscape has led SMEs to find a balance between the developing opportunities from the post-pandemic context while needing to ensure the required stability for their long-term survivability and sustainability. Hence, the paradox of change and stability revolves around the notion of taking advantages from these new opportunities while ensuring the stability to navigate the new turbulent contingencies.

As confirmed by previous literature, SMEs suffer from “liability of smallness,” often facing constrains in resources and expertise (e.g. Alves & Galina, Citation2020; McCann et al., Citation2023). Our study’s second paradox explores the pressure of managing internal strengths and resources while remaining outward-focused, capitalizing on external opportunities like the rise of digitalization and advancements in global commerce. In the post-pandemic landscape, balancing inward and outward perspectives is crucial for SMEs to adapt to new market dynamics and identify internal opportunities and networks (Ahmadi et al., Citation2020).

In the third paradox the focus of our study is innovation. While crucial for competitiveness (Yusof et al., Citation2023), SMEs might shy away from innovative practices due to limited knowledge, resources, or opportunity recognition (Alves & Galina, Citation2020). However, these businesses can often display higher levels of radical innovation (Tang et al., Citation2021). Therefore, we posit that the short-term incremental vs long-term radical innovation paradox holds significant value in the post-pandemic Landscape. SMEs can choose to pursue short-term incremental changes to improve existing processes, products, and services, or prioritize long-term radical innovation for long-term competitiveness and stronger adaptability in the new macroeconomic context.

This research provides a critical and analytical overview of SME practices during the pandemic, providing a comprehensive understanding of the crucial factors shaping SMEs in the new post-pandemic reality. The study makes valuable contributions to multiple actors. Firstly, it offers scholars and practitioners a holistic overview of the research body, covering various dimensions and themes related to pandemic-impacted SMEs. Secondly, it provides valuable guidance for SME owners/managers seeking support and direction in their efforts to understand and adapt their firm’s operations to become more resilient. Lastly, it offers a broad analysis supporting policymakers and government institutions in future endeavors related to the evaluation and improvement of SME performance. Given that the pandemic has exposed SMEs to numerous challenges, disrupting their ongoing activities, reducing revenues, and increasing financial risks (Dayour et al., Citation2020; Rao et al., Citation2022), the new reality brings forth additional challenges in the form of a more digitalized world and increased uncertainty in international markets (World Economic Forum, Citation2023). Our conclusions, presented through the tri-dimensional model, reflect the paradoxes arising from the post-pandemic reality. These paradoxes encompass contrasting perspectives, such as chance vs. stability, inward vs, outward perspectives, and short-term incremental vs. long-term radical innovation. Finally, we offer recommendations for future research in this domain.

The study is organized into five sections. After this introduction, Section 2 presents the methodological approach employed in our research, encompassing the data collection method and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline used in this review. Section 3 presents the comprehensive findings of the SLR, both in terms of content and context analysis. Section 4 addresses tri-dimensional model that reflects the paradoxes brought about to analyze the challenges SMEs face in the aftermath of the post-pandemic reality as a typical situation of a VUCA context. These paradoxes encompass divergent perspectives, including the balance between chance and stability, the tensions stemming from inward and outward perspectives, and the strategic choices between short-term incremental progress and long-term radical innovation. Lastly, section 5 presents the conclusions and recommendations for future research endeavors.

2. Theoretical background

The pandemic crisis had a profound impact on supply chains, leading to fragmentation, logistical constraints, and a scarcity of key resources, resulting in a significant imbalance between supply and demand (Morgan et al., Citation2020). While the full economic effect of this crisis on SMEs is yet to be fully understood, it is crucial to examine how these organizations adapted and reorganized their activities in the new post-pandemic reality. Crises can greatly influence an organization’s sustainability, continuity, and survivability, necessitating timely and assertive actions to secure its future (Beliaeva et al., Citation2020; Pearson & Clair, Citation1998). Crisis management has been extensively studied in various domains, including crisis impact, strategic leadership, contingency planning, and capabilities (Hong et al., Citation2012). However, much of the past research has focused on larger firms, and therefore, may not fully encompass the unique characteristics and dynamics of a health crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic in SMEs and its effect on the new post-pandemic reality.

Sustainable business practices rely on the interaction between firm-specific factors, such as financial and human resources, and macro factors, such as socio-economic environments (Rao et al., Citation2022). SMEs faced more pronounced challenges than ever before as the inevitable effect of the pandemic led many to suspend their business activities (Thorgren & Williams, Citation2020), decrease investments (Kraus et al., Citation2020), reduce their workforce (Cowling et al., Citation2020), and implement cost control measures (Corredera-Catalán et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, the global markets for these institutions were severely disrupted by rapid changes in technological advances, consumption patterns, and new business models (Tan et al., Citation2022). As such, SMEs need to be flexible and adaptable in order to address innovation, based on constant change and organizational readiness to deal with volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous environments.

Firms can respond to an economic crisis in several ways, either through internal-focused actions aimed at mitigating the negative impact of the crisis or externally, by modifying their surrounding environment (Beliaeva et al., Citation2020; Chattopadhyay et al., Citation2001). When facing crises, firms may adopt defensive approaches, reducing operational costs, limiting investments, and scaling back research and development activities (Beliaeva et al., Citation2020). Alternatively, they may choose offensive approaches by embracing proactive strategies such as innovation, investing in market growth, and promoting organizational learning (Alonso-Almeida & Bremser, Citation2013; Beliaeva et al., Citation2020). Alonso-Almeida and Bremser (Citation2013) proposed a concept of crisis management consisting of three spheres: crisis identification, proactive strategies, and reactive strategies. Proactive strategies are preventive in nature, involving the development of management strategies to strengthen the firm’s operations before, during, and after the crisis period (Alonso-Almeida & Bremser, Citation2013; Kukanja et al., Citation2020). On the other hand, reactive strategies, also known as responsive strategies, are unplanned and impulsive. These strategies involve ad-hoc management decisions, often resulting in disruptive changes within the organization, such as workforce reductions and expense reductions (Kukanja et al., Citation2020).

According to Wenzel et al. (Citation2021), SMEs have strategically responded to the pandemic crisis in various ways, including retrenching, persevering, innovating, or exiting. Retrenchment strategies aimed to reduce costs and expenses to counterbalance the decline in revenue, while persevering strategies focused on maintaining ongoing business strategies (Aničić & Paunović, Citation2022; Wenzel et al., Citation2021). In a study of Serbian SMEs conducted by Aničić and Paunović (Citation2022), it was found that 86% of the respondents used persevering strategies, while 67% employed retrenchment strategies. Similar findings were observed in the work of Thorgren and Williams (Citation2020), indicating that SMEs took immediate actions, irrespective of their expectations, to preserve resources, decrease negative cash flows, and reduce immobilization (Aničić & Paunović, Citation2022).

Building on the resource-based view (RBV) (Barney, Citation1991), dynamic capabilities research recognizes the importance of strategic change for firms to sustain and improve competitive advantages, ensuring both competitiveness and future sustainability (Alves & Galina, Citation2020; Dejardin et al., Citation2022). These capabilities are crucial in affecting how firms utilize, capitalize on, and acquire new resource configurations as the market evolves (Eisenhardt & Martin, Citation2000). This theory highlights an organization’s ability to adapt, integrate, and reconfigure internal and external resources in the face of changing environments (Teece et al., Citation1997).

Our first paradox of organizational dynamics arises from the tension between stability and change. While SMEs often exhibit greater levels of agility in their operations and strategies (Franczak & Weinzimmer, Citation2022), balancing these dynamic capabilities with the need for stability and continuity present a significant challenge, mainly as a result of their limited resources and knowledge (Freeman et al., Citation1983). The Dynamic Capabilities Theory (DCT) can help us understand how SMEs navigate this paradox. SMEs need to develop the ability to balance stability and change, leveraging existing resources while exploring new opportunities (Alves & Galina, Citation2020). This involves not only responding to external disruptions but also proactively shaping their competitive landscape through innovation and strategic adaptation (Kaur, Citation2020). Additionally, the RBV offers valuable insights into how SMEs leverage their internal resources and capabilities to achieve sustainable competitive advantages, such as balancing inward and outward perspectives (El Nemar et al., Citation2022). This means strategically allocating resources to capitalize on external opportunities while leveraging internal strengths (Cho & Linderman, Citation2020). These theories (DCT and RBV) shed light on how SMEs identify and exploit competitive advantages through short-term incremental improvements or long-term radical innovative practices.

Governments and policy measures played a crucial role in assisting the recovery and revitalization of SMEs in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. Unlike the 2007–2008 financial crisis, European policymakers recognize the utmost importance of supporting SMEs during this period (Juergensen et al., Citation2020). Policy packages were implemented, with the first phase focused on survival, aiming to minimize job losses, provide financial support, and prevent widespread insolvencies. As mentioned by Juergensen et al. (Citation2020), although the survival phase was crucial for ensuring viability, transitioning from this stage to the renewal and growth phase requires a well-planned sequence of policy packages. While initial measures such as loan guarantees, tax deferrals, debt payments, and subsidies have helped SMEs withstand the crisis (Juergensen et al., Citation2020), in the long run, these measures may not be sustainable enough to overcome the challenges posed by the post-crisis scenario. Therefore, policymakers must take the necessary steps to design and implement conducive environments that promote innovation, entrepreneurship, internationalization, networking, and infrastructural investment among these organizations (Juergensen et al., Citation2020; Pedauga et al., Citation2022; Trawnih et al., Citation2021). The significance of supportive and effective governmental support and policy design cannot be underestimated in times of economic uncertainty, as SMEs often struggle to cope with the challenges posed by economic downturns. Government entities and public policies play a crucial role in providing the required stability and support for businesses to ensure their survival and competitiveness in critical contexts (Caiazza et al., Citation2021; Hossain et al., Citation2022; Juergensen et al., Citation2020).

SMEs operating within a global framework face the complexities of navigating intricate services and products, unforeseen technological advancements, and perpetually evolving market dynamics that influence customer decision-making (CitationÇiçeklioğlu, 2020). The inherent dynamism stemming from the volatile, uncertain, ambiguous, complex, and ambiguous socio-economic context (also referred to as the VUCA phenomenon) calls for effective leadership, coordination, and management within organizations (Ahmadi & Osman, Citation2020; Çi̇çekli̇oğlu, Citation2020). Considering the current business landscape, SME owners and managers are faced with the crucial task of skillfully navigating their organizations through the challenging circumstances of the post-pandemic context, while managing the complex relationship of internal tensions and paradoxes, such as change vs. stability, inward vs. outward, and short-term vs. long-term perspective. However, as Fortes et al. (Citation2023) rightly point out, paradoxes should not be viewed solely as problematic issues but rather as daily challenges that test the organizational and strategic relationships of an organization. By effectively mapping these elements, SMEs can enhance their operational efficiency and contribute to reducing levels of internal tension within the company while fostering higher ambidexterity.

3. Methodology

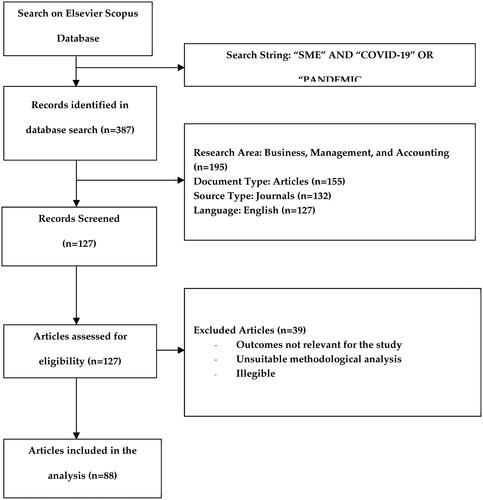

An SLR employs a reliable and meticulous methodology to explore, evaluate, and assess existing literature (Greenhalgh, Citation1997; Tranfield et al., Citation2003). SLRs are used to interpret all available research in a specific field, providing an unbiased and comprehensive evaluation of relevant knowledge while recognizing existing insights and potential guidelines for future research (Tranfield & Denyer, Citation2009). In this study, we respected the PRISMA guidelines, which enhances the review and analysis process through an accurate and detailed checklist (Page et al., Citation2021), as shown in .

For this study, we chose the Scopus database, a leading database for peer-reviewed publications (Talapatra et al., Citation2019), known for its comprehensiveness compared to other databases (Devi & Srivastava, Citation2022). In the data collection process, we considered only journal papers in their final form, excluding conference proceedings, book chapters, and reports, as journal articles are considered the most validated knowledge in the field of management (Podsakoff et al., Citation2005).

The selected articles were retrieved using the search terms “SME” and “COVID-19” or “Pandemic” in the title, abstract, and/or keywords. The search string combination used was the one that yielded the largest number of relevant publications on the topic. Furthermore, as we aimed to conduct a holistic and all-inclusive analysis of SME practices during the pandemic, we did not restrict the search to a specific dimension of knowledge, timeframe, or theory. The initial search resulted in a total of 387 articles.

The search was then limited to articles belonging to the business, management, and accounting area (n = 155), published in their final stage (n = 132), and written in English (n = 127). We assessed the 127 articles for eligibility in our analysis by applying an inductive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Ribau et al., Citation2018). After a rigorous analysis of the abstracts and keywords, we excluded 39 articles that did not meet the criteria of relevance to our research, as they lacked significant findings and topics. The final sample consisting in 88 eligible articles for analysis.

Following an interpretative analysis and based on the article topics, findings, and core ideas (Ribau et al., Citation2018), we identified and categorized the articles into three themes: (i) organizational focus; (ii) organizational dynamics; and (iii) role of innovation. Based on these themes, we will proceed to propose a tri-dimensional categorization of the literature.

4. Findings

This section proceeds with the presentation of our findings by employing a rigorous content and inductive thematic analysis (Hossain et al., Citation2022; Rêgo et al., Citation2021). Our analysis is conducted within the framework of our proposed tridimensional model, which enables a comprehensive exploration and evaluation of the collected articles.

4.1. Content analysis

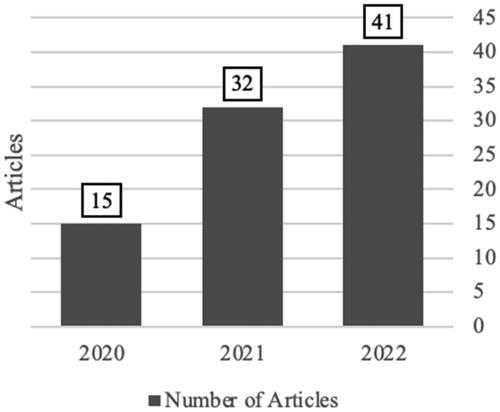

The COVID-19 pandemic has sparked a surge in research literature, with exponential growth since 2020 (). This unprecedented event has paved the way for various research avenues in international business (Klyver & Nielsen, Citation2021), finance (Calabrese et al., Citation2022), innovation (Kowalik & Pleśniak, Citation2022), digitalization (Kusuma et al., Citation2022), dynamic capabilities (Ashiru et al., Citation2022), crisis management (Kukanja et al., Citation2020), strategic management (Cepel et al., Citation2020), among others. These studies have shaped and defined the future directions in the research domain of SMEs.

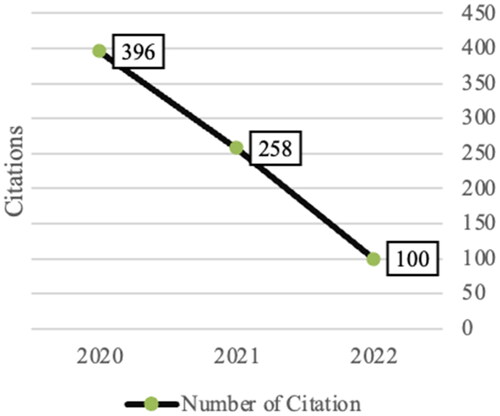

The temporal evolution of articles can be observed in , illustrating the increasing trend in research activity on this subject. However, the number of citations follows a declining trend. Articles published in 2020 have an average of 26.4 citations per article, followed by 2021 with an average of 8 citations per article, and 2022 with an average of 2.4 citations per article, as shown in .

The analysis of the 88 articles included in this paper reveals that they have been published in a total of 71 different outlets. It is worth noting that most of the journals in our sample have only published one article on this topic, with a few exceptions. As shown in , the Journal of Industrial and Business Economics stands out with the highest number of citations, totaling 142. These citations are primarily attributed to the article by Juergensen et al. (Citation2020), where the authors examine the impact of COVID-19 on European SMEs and the corresponding policy responses. Following closely, the Research in International Business and Finance journal ranks as the second most cited, with a total of 67 citations. The International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship comes in third place with 62 citations, spread across two published articles.

Table 1. Most cited journals.

In our sample, we found multiple research designs (), ranging from conceptual articles to case studies. Remarkably, almost half of the studies follow a quantitative research design; these 37 articles have provided the empirical based analysis on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in SMEs. Within these, many have used in their study primary and secondary data sources in the form of questionnaires, interviews, and qualitative observation. In spite of the fact that studies of a quantitative nature embody the largest share in our sample, conceptual articles manage to capitalize the biggest number of citations within the literature – with an average of 26.6 citations per article. Qualitative research articles represent the third highest number with 15 articles, followed by mixed approach with nine articles.

Table 2. Research methodologies in the sample.

The sample of 88 articles included a combined total of 754 citations; however, the Scopus database accounted for citations in only 63 of these articles. highlights the ten most cited articles within our sample. Notably, Juergensen et al. (Citation2020) emerged as the most highly cited among them, with 142 citations. The authors analyzed the impact of the pandemic on European manufacturing SMEs and suggested policy renewal to promote innovation, internationalization, and networking, thereby moving beyond short-term survival (Juergensen et al., Citation2020). The article by Caballero-Morales (Citation2021) stands as the second most highly cited publication, accumulating a total of 67 citations. The study outlines a methodological approach for SMEs to innovate and target new markets with limited resources, emphasizing the significance of digital resources in facilitating networking and research-based product design during the pandemic crisis (Caballero-Morales, Citation2021).

Table 3. Top-10 most cited articles.

4.2. Contextual analysis

4.2.1. Categorization scheme for SMEs in the post-pandemic normality

To address the inherent tensions and paradoxes in SMEs responses to the pandemic, we developed a tridimensional categorization, as depicted in . This framework explores the contradictions and interdependencies through three axes representing opposing perspectives. Notably, the model recognizes the paradoxical nature of SME responses, where short-term survival strategies coexist with long-term strategic concerns.

Drawing from Juergensen et al. (Citation2020), the model reflects the nuanced interplay between the immediate need for governmental support and the imperative for SMEs to strategically position themselves for sustainable post-crisis growth. Accordingly, integrating governmental support into our tridimensional framework is not just a reflection of immediate survival needs, but an acknowledgement of its enduring influence on organizational focus, dynamics, and innovation.

The first axis examines the tension between stability and change. Some companies and their employees may find themselves stuck in their current modus operandi, struggling to navigate the complexities brought about by the new patterns of digital transition and the need to adapt to sudden changes. On the other hand, there are those who actively embrace change, internalize external shifts, and actively seek survival through a forward-looking approach.

The second axis revolves around inward and outward perspectives. Inward-focused companies tend to isolate themselves, relying on reactive effort to adjust to new challenges. This insular approach can hinder success. In contrast, outward-focused companies embrace a long-term orientation, actively engaging with change, and remaining receptive to the challenges faced by competitors dynamics. They also leverage governmental support to leverage the advantages offered by public policies.

The third axis addresses the tensions between short-term incremental and long-term radical innovation. In the face of a digitalized world, firms play a critical role in developing new innovation competencies to navigate the contextual changes they must overcome. This axis explores the tensions arising from the need for companies to engage in both short-term incremental innovations to address immediate challenges and long-term radical innovations to drive sustained growth. These three axes capture the complexities and contradictions faced by SMEs in the new post-pandemic reality, providing a framework to analyze and understand their strategic responses.

4.2.2. Organizational dynamics

As the reality of the pandemic unfolded, many SMEs swiftly restructured their capabilities and processes to adjust to the unsettling new context (Cankurtaran & Beverland, Citation2020). However, due to their inherent liability of smallness, many SMEs struggled to adapt rapidly to the new challenges (Ashiru et al., Citation2022). According to Yeon et al. (Citation2022), environments characterized by high uncertainty require firms to utilize their responsive capabilities, making it crucial for SMEs to translate overwhelming challenges into manageable organizational responses. Dynamic capabilities play a central role in implementing responsive strategic goals and achieving competitive outcomes (Gnizy et al., Citation2014; Yeon et al., Citation2022). These capabilities can be described as distinctive organizational and strategic processes through which firms renew and acquire new or existing configurations of resources (Eisenhardt & Martin, Citation2000). Dynamic capabilities are essential for enhancing and promoting a firm’s performance by extending its resources, competencies, routines, and processes (Dejardin et al., Citation2022). While dynamic capabilities are considered crucial for organizational efficiency and strategic response (Wang et al., Citation2021), cultivating these attributes is more challenging for SMEs compared to larger firms (Hernández-Linares et al., Citation2021). Moreover, larger firms, due to their greater resource bundles, possess superior financial leverage to maintain and advance their ongoing operations during economic downturns, making them more proficient at enduring challenging economic times (El Chaarani et al., Citation2022; Lee et al., Citation2012). However, our sample findings highlight the exceptional centrality of dynamic capabilities for SMEs, contributing to their success in an increasingly competitive business landscape that demands higher levels of adaptability and flexibility (Hernández-Linares et al., Citation2021). Nonetheless, unlike their larger counterparts, SMEs may find it challenging to renew their resources (Wang & Shi, Citation2011).

Only in recent years have scholars focused their efforts on the distinctive features of SMEs and their dynamic capabilities (e.g. Dejardin et al., Citation2022; Soluk & Kammerlander, Citation2021). However, despite the growth in research in this domain, empirical findings remain scarce and ambivalent (Hernández-Linares et al., Citation2021). The existing literature has provided crucial insights into quantifying the role of dynamic capabilities, strategic response, and SME performance in navigating the fierce landscape complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic (Dejardin et al., Citation2022; Quansah et al., Citation2022; Soluk & Kammerlander, Citation2021). Among the analyzed sample, findings suggest the positive effects of dynamic capabilities. For instance, Clampit et al. (Citation2022) found that SMEs that nurture dynamic capabilities outperformed those that did not. Furthermore, firms with higher levels of dynamic capabilities can develop the necessary resilience capabilities to improve their competitive position in the face of common challenges.

4.2.3. Organizational focus

4.2.3.1. Inward-focused

Within our sample, we have identified numerous recommendations aimed at helping SMEs improve their competitiveness and mitigate the adverse effects of the pandemic crisis. These recommendations include incentives to innovate, the ability to pivot, coping strategies, learning strategies, and the implementation of digitalization measures such as e-business platforms (Klyver & Nielsen, Citation2021; Morgan et al., Citation2020; Rozak et al., Citation2023). Efficient crisis management requires a comprehensive analysis that involves careful planning, effective communication among management members, and a readiness to adapt, revise, and make necessary changes to the firm’s ongoing operations (Kukanja et al., Citation2020, Citation2021). These factors are crucial for enhancing adaptability in the post-crisis context.

According to Pedersen et al. (Citation2020), a crisis can be understood in five different phases: (1) pre-crisis normality; (2) emergence; (3) occurrence; (4) aftermath; and (5) post-crisis normality. The pre-crisis phase involves measures aimed at preventing a crisis. As suggested by Bundy et al. (Citation2017), this phase includes changes in the organization’s internal culture, improving stakeholder relationships, and preparing the firm for possible managerial changes. The emergence phase is characterized by more evident signs of an impending crisis. During this phase, organizations still have the opportunity to prepare for the crisis (Ashiru et al., Citation2022; Bundy et al., Citation2017; Pedersen et al., Citation2020). As suggested by Hong et al. (Citation2012), firms can enhance their preparedness by investing in innovation, market diversification, and insurance.

The occurrence phase requires organizations to implement actions and responses promptly. Decision-making speed becomes critical during this phase, as many assessments must be made on an ad hoc basis (Pedersen et al., Citation2020). Following the occurrence phase, responses and actions are set in motion with the goal of recovering from the crisis shock (Pedersen et al., Citation2020). The final phase is the post-crisis phase, where organizations return their operations to normality.

Leadership is one of the most crucial elements in organizational focus, particularly for SMEs. Leadership dictates the decision-making process, motivates the workforce, builds, and maintains relationships both inside and outside the firm, and sets a clear direction for the organization’s future and vision (Quintana et al., Citation2015; Van Wart, Citation2012). Leadership has been analyzed through various evaluations, including leadership styles, leadership models, leadership theories, and management styles (Mihai, Citation2021). SME owners, who often play a central role within their organization, serve as the backbone of the firm. They strategically shape the pursued strategies, manage operations, and significantly influence the organization (Widianto & Harsanto, Citation2017). Creating a streamlined organizational structure is crucial for SMEs as procedural management can lead to internal tensions and a reduction in the organization’s decision-making ability during unstable conditions (Fasth et al., Citation2022).

4.2.3.2. Outward-focused

SMEs operate within a fiercely competitive landscape (Avlonitis & Salavou, Citation2007), which dictates the development of effective managerial strategies to overcome market challenges and external factors (Graves & Thomas, Citation2006). This demands adaptability, flexibility, and dynamism amidst increasing uncertainty and market pressures, especially in a post-pandemic scenario. In highly unstable environments, it is essential to find a balance between exploitation and exploration, as these two strategies are crucial for long-term performance and survival (Kang et al., Citation2021; Kim et al., Citation2015). Nonetheless, as Kang et al. (Citation2021) point out, achieving this balance presents a great challenge for resource-constrained SMEs, due to the increasing strategic complexity demanding different structures and skills. In this sense, attaining ambidexterity can become challenging.

In contrast, outward-focused firms can be depicted by their proactive approach towards innovation, adaptability, and opportunity seeking behavior, displaying high levels of organizational ambidexterity (Ahmadi et al., Citation2020). It is recognized that ambidextrous firms Their enhanced absorptive capacity, a key dynamic capability, empowers them to recognize and attain value from new, external information and opportunities (Liu & Laperche, Citation2015; Yu, Citation2022).

According to the RBV (Barney, Citation1991), firms must capitalize on their valuable, rare, and non-replicable resources, pivoting them to differentiate themselves from competitors. In the new post-pandemic crisis context, it becomes crucial for SMEs to carefully evaluate their enabling factors and redirect their organizational focus towards shaping new and disruptive business models.

4.2.4. Innovative practices

4.2.4.1. Short-term incremental innovation

Incremental innovation involves steadily refining or improving existing processes, products, services, and technologies (De Vries & Verhagen, Citation2016; Yusof et al., Citation2023). Due to their limited resources, SMEs are intrinsically more rely heavily on incremental innovation as their primary source of innovative practice (Du, Citation2021). This strategy offers short-term gains in efficiency and performance, particularly valuable for SMEs with constrained technological and expertise resources (Xu, Citation2020; Eriksson & Szentes, Citation2017).

While the potential for groundbreaking advancements through incremental innovation may be limited (Calabrese et al., Citation2005), the knowledge-based view suggests that consistent innovation efforts and accumulated knowledge are crucial for achieving both innovative advances and firm performance (Du, Citation2021). As observed in our sample, innovation is a key driver of competitive advantage, productivity, brand value, and financial turnover (Duran et al., Citation2016; Henley & Song, Citation2020; Kyvik, Citation2018). Notably, fostering innovative strategies has been linked to increased preparedness for incoming crises shocks, enhancing organizational resilience, and driving economic development in SMEs (El Chaarani et al., Citation2022; Falahat et al., Citation2020; Hong et al., Citation2012).

The pandemic crisis had a severe impact on the survival prospects of many SMEs. According to Adam and Alarifi (Citation2021), innovative practices in external knowledge, leadership, and workforce activities positively affect SMEs’ survival indicators. They also found that the importance of innovation on SME performance outweighs its influence on their survival, indicating that managerial innovation practices have a greater impact on short-term performance compared to long-term performance (Adam & Alarifi, Citation2021).

Despite having limited economies of scale and scope and weaker absorptive capacity, SMEs often make significant investments in high-risk innovation activities, which is known as the SMEs innovation paradox (Fragkandreas, Citation2017; Ortega-Argilés et al., Citation2009). During economic downturns, the inherent paradoxes associated with innovation become more apparent (Buekens, Citation2013). When examining the level of innovation within a specific company and its impact on R&D activities, direct and indirect mechanisms can be considered (Ortega-Argilés et al., Citation2009). The direct mechanism relates to the internal development of products, processes, and services within the firm, while the indirect mechanism considers the company’s absorptive capacity and knowledge acquisition, leading to higher innovative performance (Ortega-Argilés et al., Citation2009).

4.2.4.2. Long-term radical innovation

Unlike incremental innovation’s focus on exploration, radical innovation is inherently exploitative, driven by novelty and disruptive change (De Vries & Verhagen, Citation2016). It demands higher levels of resources, extensive development, and experimentation (Eriksson & Szentes, Citation2017; Yusof et al., Citation2023). Nonetheless, while offering potentially greater long-term gains, radical innovative practices carries a longer timeframe for realizing return on investment compared to incremental approaches, making the latter often more suitable for SMEs seeking to immediate performance improvements (Eriksson, Citation2017).

Strategic factors such as market orientation, technology policy, and entrepreneurial orientation support innovative practices (Salavou & Lioukas, Citation2003). SMEs often prioritize radical transformations to effectively compete with larger firms, as innovation can range from incremental enhancements to radical changes (Salavou & Lioukas, Citation2003). Ambidextrous firms have the capacity to pursue distinct goals simultaneously, such as exploiting/exploring, efficiency/adaptability, and incremental/radical innovation (De Clercq et al., Citation2014; De Visser et al., Citation2010; March, Citation1991). Competitiveness demands that firms possess ambidexterity and the ability to engage in both incremental and radical innovation processes (Tushman & O’Reilly, Citation1996). In our sample, SMEs actively pursuing radical innovative practices achieved higher scientific and technological advancements, contributing to the overall performance and capabilities of the firm (Ighomereho et al., Citation2022; Kowalik & Pleśniak, Citation2022; Zhang et al., Citation2022). Caballero-Morales (Citation2021) found that innovation served as a key instrument for SMEs during the pandemic, improving their product and market placement and facilitating networking within their industry.

According to Zhang et al. (Citation2022), innovation is directly linked to the age of firms. Older firms tend to be more restricted by their existing resources and embedded market and consumer orientation, resulting in a higher likelihood of engaging in incremental innovation practices. On the other hand, younger firms, in their quest to break through established markets, are more likely to explore radical innovative ideas and potentially generate more positive returns from innovative practices.

R&D activities are highly influenced by proximity to the technological frontier, with SMEs experiencing growth triggered by high-tech environments and technologically advanced regions (Hölzl, Citation2009; Ortega-Argilés et al., Citation2009). As emerging technologies, including digitalization, hold immense potential to foster innovation and provide competitive advantages (Solberg et al., Citation2020), the advent of the new digital revolution expands the scope of firms beyond traditional supply and value chains, enabling the establishment of thriving innovation ecosystems and valuable network configurations (Radicic & Petković, Citation2023; Xu, Citation2020).

Improving technology capacity has been found to significantly increase revenue and innovative output for small firms (Doerr et al., Citation2021). However, SMEs face several barriers to digitalization, which hinder their ability to drive innovation and achieve overall firm performance. These barriers include limited financial and human resources, internal resistance to change, and overall digital illiteracy (Estensoro et al., Citation2022; Radicic & Petković, Citation2023). Although SMEs often engage in innovation without explicit investments in R&D or dedicated R&D departments, they can still demonstrate similar levels of innovation as R&D-focused firms by effectively incorporating management practices that facilitate interactive learning from various internal and external knowledge sources (Radicic & Petković, Citation2023; Thomä & Zimmermann, Citation2020). Moreover, non-R&D SMEs can recognize digitalization as a means to stimulate innovation, organizational learning, and interactive learning (Estensoro et al., Citation2022; Radicic & Petković, Citation2023; Solberg et al., Citation2020).

5. Categorization scheme

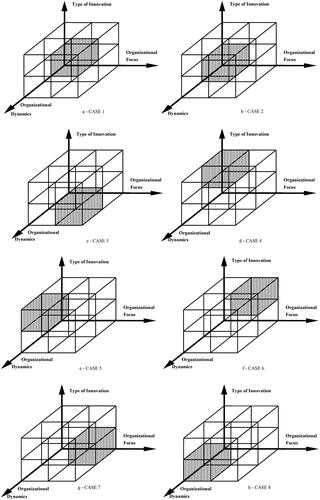

Considering the factors mentioned earlier, there are eight scenarios depicted in , each implying distinct propositions for SMEs.

Figure 5. Tridimensional categorization of SMEs practices. (a) Case 1, (b) Case 2, (c) Case 3, (d) Case 4, (e) Case 5, (f) Case 6, (g) Case 7, (h) Case 8.

5.1. Case 1: externally-focused disruptive innovators

Case 1 ((a)) encompasses SMEs that thrive in highly dynamic environments. They exhibit a prominent emphasis on proactive actions directed externally and target radical innovation with long-term disruptive potential. This scenario can be considered optimal for generating competitive advantages as it allows companies to leverage their organizational strengths through efficient and radical innovation processes, adopt internal dynamics in assimilating emerging market and industry patterns, and a dedicated focus on obtaining the necessary components to demonstrate competence and effectiveness in challenging circumstances. Urbanska et al. (Citation2021) highlight that SMEs possess high levels of adaptability to evolving environments and fluctuating market conditions, showcasing their ability to quickly adapt their economic activities to gain competitive advantages. This notion is further supported by the fact that SMEs often align themselves with changing environmental conditions by adopting new technological advancements, innovative practices, and exploratory learning to ensure their continuity (Gavrila & de Lucas Ancillo, Citation2021; Olejnik & Swoboda, Citation2012; Todericiu, Citation2021; Wahid & Zulkifli, Citation2021). However, exploitation and exploration represent two distinct learning endeavors that compete for the organization’s focus and resources (Ahmadi & Osman, Citation2020). Therefore, to consistently update their strategies and capabilities, SMEs require higher capabilities from their human and financial assets to effectively respond to market and industry competitiveness (Patel et al., Citation2013). In this scenario, SMEs are expected to have high levels of crisis management as they stay informed about their surroundings, external trends, and prepare in advance for any contingencies. Furthermore, SMEs in this scenario can serve as examples of ambidextrous organizations, as they are highly proactive in internal processes, pursuing both exploitation and exploration processes (Tushman & O’Reilly, Citation1996).

5.2. Case 2: internally-focused stable incremental innovators

Case 2 ((b)) involves SMEs engaged in short-term incremental innovation, with an inward organizational focus and a preference for maintaining stability in their structure. This is the worst-case scenario for SMEs. Due to limited financial and personnel resources, many SMEs direct their internal organizational efforts toward securing financial stability, consciously avoiding uncertain and risky investments (Saci & Mansour, Citation2023). Consequently, despite their organizational flexibility, many SMEs only embrace technological advancements or venture into unexplored business domains when industry pressures or imminent jeopardy to their survival compel them to do so, as observed in our sample (Hossain et al., Citation2022; Patma et al., Citation2020; Rakshit et al., Citation2021). While striving to improve their competitive advantages and maintain business longevity (Ogrean & Herciu, Citation2021), they must remain reactive and adaptable to external macroeconomic changes, as this balance is fundamental for building organizational resilience and fostering competitiveness in the post-pandemic normality (Manfield & Newey, Citation2018). Furthermore, companies in this case are likely to exhibit low levels of crisis management as they maintain a strong internal focus and dynamics. Consequently, there may not be an active culture of crisis management, making them more susceptible to external shocks within their organization.

5.3. Case 3: agile incremental innovators

Case 3 ((c)) reflects SMEs engaged in short-term innovation, with an outward organizational focus and changes in their organizational dynamics. According to our findings, this case represents a significant portion of SMEs’ modus operandi. Although these SMEs have active innovation processes, they tend to prioritize ongoing improvements of their offerings and services rather than venturing into radical innovative practices (e.g. Falahat et al., Citation2020; Kusuma et al., Citation2022; Rozak et al., Citation2023). As previously mentioned, SMEs can readily embrace innovation if they have the necessary resources and capabilities (Udomdech et al., Citation2019; Wang et al., Citation2010). However, radical innovations require additional investments and entail excessive risks, leading many SMEs to disregard them (Davis et al., Citation2016; Udomdech et al., Citation2019). In this scenario, we observed SMEs that, despite their commitment to staying abreast of industry and market trends, adopt incremental approaches to innovation due to financial constraints and the liability of smallness (Urbanska et al., Citation2021). This can be seen in SMEs adopting digitalization in their operations. According to Radicic and Petković (Citation2023), digitalization has proven to be a valuable asset for SMEs at the organizational level, driving innovative development and contributing to competitive capabilities during and after the pandemic crisis. As digitalization facilitates operational efficiency improvements, it has become central for SMEs during and after the pandemic, especially considering the impact of lockdowns and social distancing measures (Ogrean & Herciu, Citation2021; Radicic & Petković, Citation2023; Škare & Soriano, Citation2021).

5.4. Case 4: internally-focused stable disruptive innovators

Case 4 ((d)) mirrors SMEs with a focus on long-term radical innovation, inward organizational focus, and stability in organizational dynamics. In this scenario, companies prioritize internal dynamics and stability, choosing not to pursue change extensively. However, they engage in radical innovation processes. From a practical standpoint, this scenario can be debated. As mentioned earlier, radical innovation processes are usually associated with higher expenses and require greater skills and knowledge within the organization (Davis et al., Citation2016). Therefore, in a scenario where SMEs have a dynamic focus on stability and lack an outward focus on gaining competitiveness, they may not be as capable of making significant innovative investments. The lack of outward focus may lead to a more conservative approach to investments, prioritizing stability and continuity of existing operations over seeking new growth and business opportunities. SMEs that prioritize stability may be more cautious in taking on the risks associated with radical innovation, fearing that it may disrupt the achieved balance and operational continuity (Simms et al., Citation2022). However, it is crucial to note that innovative practices and the pursuit of competitive advantages are not limited to large-scale investments. Even in a scenario with a dynamic focus on stability, companies can adopt more incremental strategies and approaches to improve their existing products, processes, or services (Azar & Ciabuschi, Citation2017; Salavou & Lioukas, Citation2003; Udomdech et al., Citation2019). Incremental innovative improvements can help SMEs maintain competitiveness within their markets, even without significant investments in radical innovation (Salavou & Lioukas, Citation2003). Furthermore, it is important to consider that business landscapes are constantly changing and subject to profound transformations (Zhang et al., Citation2015). Even though firms may prioritize short-term stability, they must adapt and innovate to remain competitive in the future (Zahra, Citation2022). Therefore, SMEs need to find a balance between stability and the ability to reshape their operations. In this context, SMEs with a focus on stability may experience slower adoption of digital technologies compared to companies with a dynamic focus on change and outward adaptability. Consequently, these SMEs may lack the competitive capabilities, dynamic capabilities, and crisis management required to keep up with the rapid evolution of business markets in the post-pandemic normality.

5.5. Case 5: internally-focused dynamic disruptive innovator

Case 5 ((e)) represents companies with a long-term focus on radical innovation, an internal dynamic centered around change, and an inward organizational focus. In this scenario, SMEs exhibit a high level of internal dynamism, characterized by the implementation of highly flexible business strategies to mitigate disruptions during times of crisis. These companies foster a culture that enhances their dynamic capabilities, increasing their capacity to respond effectively to external crises. As mentioned earlier, economic downturns may result in increased investment in innovation processes to develop internal capabilities that can protect the business from market shocks (Adam & Alarifi, Citation2021; El Chaarani et al., Citation2022; Falahat et al., Citation2020). In our sample, many companies shifted their focus to innovation as a means to cultivate defensive mechanisms and gain competitive advantages (Bongso & Hartoyo, Citation2022; Caballero-Morales, Citation2021; Nani & Ndlovu, Citation2022; Saroso et al., Citation2022). Consequently, there is an emphasis on radical innovation processes within this case.

5.6. Case 6: externally-focused stable disruptive innovator

Case 6 ((f)) depicts SMEs that prioritize radical innovation processes, with organizational dynamics centered around stability and an outward focus. These companies demonstrate a high level of adaptability in their organizational focus, actively seeking out new trends to foster competitive competencies. However, they may exhibit low organizational focus in terms of their structure, which can be attributed to the organizational deficiencies commonly observed in SMEs (Ashiru et al., Citation2022; Urbanska et al., Citation2021). Despite being agile in their business strategies, many of these SMEs lack the capital and human resources competencies that larger companies possess (Hong et al., Citation2012; Hudson et al., Citation2001). This scenario may also reflect companies that do not invest in fostering and developing their internal dynamic capabilities. In such cases, leadership practices can play a crucial role in enhancing the focus on external trends. Our sample findings indicate that leaders have a significant influence on how an organization operates, particularly in small and medium-sized enterprises (Mihai, Citation2021; Widianto & Harsanto, Citation2017). Mihai (Citation2021) found that leadership style is highly influenced by the maturity level of the firm, with younger firms tending to have a more autocratic approach while older and more mature firms can operate efficiently with liberal leaders, such as adopting a laissez-faire leadership style. However, it is important to note that leadership alone is not solely responsible for guiding the path of an organization during a crisis. Decision-making processes in SMEs are highly influenced by the business owner’s perceptions, principles, background, and vision (Vargo & Seville, Citation2011).

5.7. Case 7: externally-focused stable incremental innovator

Case 7 ((g)) represents companies with a high outward organizational focus, low organizational dynamism, and a tendency towards short-term incremental innovation. Despite their outward focus, these companies do not exhibit significant levels of internal or innovative dynamism, making it unlikely for them to develop sustainable business practices and organizational ambidexterity. As mentioned by Urbanska et al. (Citation2021), the ability of SMEs to quickly adapt to changes in the external landscape is crucial for their survival in uncertain economic contexts. Striking a balance between inward and outward focus is essential for achieving long-term sustainable growth and economic development in SMEs (Fasth et al., Citation2022). In order to adapt rapidly to uncertainties, firms require strategic agility and responsiveness to external exigencies (Ashiru et al., Citation2022). The revision and adaptation of business strategies and organizational focus in response to changes in the macroeconomic environment determine how businesses can navigate unforeseen circumstances. Quansah et al. (Citation2022) found that SMEs employ three sets of adaptive practices: continuous learning and process improvement, leveraging reciprocal relationships, and effective communication. These adaptive organizational practices enable SMEs to successfully adjust in high uncertainty by taking assertive actions in the face of external shocks.

5.8. Case 8: internally-focused dynamic incremental innovators

Finally, Case 8 ((h)) consists of SMEs that demonstrate high internal dynamism, an organizational focus centered internally, and engage in incremental innovation processes. Similar to Case 7, SMEs in this category are unlikely to develop the required competitive advantage to gain a strong position in the post-pandemic normality. The impact of the pandemic crisis on SMEs was heterogeneous, with some experiencing growth, some being significantly unaffected, and others suffering from the crisis (Klyver & Nielsen, Citation2021). SMEs pursuing narrower retrenchment strategies anticipated decreasing turnover, while those adopting broader persevering strategies expected increased turnover (Klyver & Nielsen, Citation2021). Technological advancements play a crucial role in fostering competitive advantages, improving organizational ambidexterity, and accelerating innovation, as observed in our sample (Rozak et al., Citation2023). The pandemic crisis has acted as a catalyst for digitalization, leading SMEs to engage more extensively with digital platforms in order to reach new markets, drive revenue, and enhance customer service (Rupeika-Apoga et al., Citation2022; Usai et al., Citation2021). Digitalization has proven to be an effective tool in crisis management, aiding decision-making, market diffusion, improving efficiency and productivity, increasing scalability and reach, reducing operational costs, and enhancing customer engagement (Endrődi-Kovács & Stukovszky, Citation2022; Hussain et al., Citation2021; Rupeika-Apoga et al., Citation2022).

6. Conclusion

6.1. Theoretical and managerial implications

This SLR aimed to shed light on how SMEs have responded to the dynamic and challenging circumstances arising from the COVID-19 pandemic over the past three years. We were rooted with the ambition to synthesize valuable insights from current body of knowledge to guide SME owners, managers, practitioners, and scholars in navigating the complexities of the post-pandemic landscape.

Our study has several implications and contributions to SME owners, managers, policymakers, and practitioners. For SME owners and managers we have introduced a novel tridimensional categorization of SMEs practices. This model, informed by the inherent paradoxes of the post-pandemic context, provides a strong theoretical foundation for future research efforts on the specific aspects of SME behavior and strategies. Second, fostering an internal culture of adaptability and flexibility enables owners and managers to identify and seize opportunities presented by the dynamic context and paradoxical challenges. Third, a balanced innovative strategy is crucial. Prioritizing both short-term incremental improvements and longer-term transformative innovations are mandatory if SMEs want to secure competitive advantage in the evolving market.

Fourth, as found in the work of Juergensen et al. (Citation2020), policymakers assume a central role in supporting SMEs during the crisis period. The role of policymakers in enabling and supporting SMEs is vital to ensure a favorable environment for enhancing their innovative practices, resilience, and sustainable growth in the post-pandemic landscape. Policymakers can also enhance networking opportunities for SMEs, like the creation of industry clusters, and knowledge transfer programs, and internationalization support to increase SMEs’ resilience in the face future exogenous crises.

6.2. Concluding remarks and future research

This article emphasizes that the nature of organizational practices in SMEs fundamentally revolves around paradoxes, such as stability vs change, inward vs outward, and radical vs incremental. In order to thrive, it is crucial for SMEs to recognize and leverage these paradoxes as unique opportunities to embrace their idiosyncrasies and shape their future in the post-pandemic reality.

During economic downturns, companies are pressured to realign their strategic focus, and SMEs must prioritize decision-making to ensure their long-term prospects and enhance their competitive advantages. Our analysis reveals that SMEs are strongly influenced by their internal dynamics and external environment, highlighting the significance of strategic adaptability as a dynamic capability for effectively adapting to post-crisis challenges (Ahmadi & Osman, Citation2020; Dejardin et al., Citation2022; Klyver & Nielsen, Citation2021; Soluk & Kammerlander, Citation2021). Previous literature has also shown that both alignment (stability) and adaptability (change) can benefit SMEs (De Clercq et al., Citation2014). While alignment enables efficient execution of current operations, adaptability facilitates the reconfiguration and rejuvenation of activities, reducing counterproductive inflexibilities (De Clercq et al., Citation2014; De Visser et al., Citation2010). Among the articles in our sample, findings provide evidence supporting the prevalence of an entrepreneurial mindset and adaptability among SMEs (e.g. Bivona & Cruz, Citation2021; Simms et al., Citation2022; Sutrisno et al., Citation2022; Syarief, Citation2021). Proactiveness and willingness to take risks were identified as crucial influences in overcoming the negative impact of the pandemic crisis. Innovation, organizational learning, skill enhancement, and competence development can stimulate and facilitate the advancement of a firm’s financial standing (Buekens, Citation2013). Maintaining balance within the organization is essential for SME owners and managers, and effective leadership plays a pivotal role in ensuring sustained success in an ever-changing and unpredictable business environment. Therefore, adopting an impactful leadership approach becomes crucial for bolstering and fostering organizational effectiveness in VUCA contexts as those presented in the aftermath of the post-pandemic reality.

In dynamic and ever-changing environments, businesses must balance optimizing existing operations and exploring new avenues for economic growth, which is seen as essential for fostering greater innovativeness (De Clercq et al., Citation2014). The advent of the fourth industrial revolution proves to be a timely advantage for SMEs, as they display ambidexterity in enhancing existing processes while expanding into groundbreaking concepts (Endrődi-Kovács & Stukovszky, Citation2022). Since the beginning of the industrial revolution, the introduction of new technologies and practices has created disparities among firms, particularly between those with the means and knowledge to adopt and implement these advancements and those without. This analogy holds true in the post-pandemic context. Although digitalization has been present for many decades, its widespread use by consumers and firms has only recently become prominent, largely due to the ubiquity of digital-enabled portable devices such as smartphones, laptops, and tablets in our daily lives (Sunarjo et al., Citation2021). Looking ahead, there will be opportunities for investment in digital technologies, not only as critical support for marketing activities but also in enhancing internal efficiency, productivity, organizational learning, knowledge, and fostering innovation (e.g. Juergensen et al., Citation2020; Radicic & Petković, Citation2023; Usai et al., Citation2021).

During periods of economic downturns, the involvement of governments and public policies becomes crucial in providing financial assistance to SMEs (Çela et al., Citation2022; Siahaan et al., 2022). This was evident during the initial stages of the pandemic when policymakers took immediate action to mitigate the consequences of the global health crisis (Aničić & Paunović, Citation2022). However, as the world transitions to a new post-pandemic reality, there is still a need for government initiatives that specifically target SMEs facing critical challenges.

The current macroeconomic context is characterized by increasing inflation rates, international trade tensions, and geopolitical conflicts that have significantly disrupted supply chains (World Economic Forum, Citation2023). In light of this situation, policymakers should reevaluate their policies to effectively respond to the post-pandemic context. Structural policies should prioritize and address the revitalization and development of SMEs, focusing on fostering innovation, international expansion, and collaborative networks to effectively tackle the forthcoming challenges (Juergensen et al., Citation2020).

In this study, we introduced a categorization system for SME practices based on the articles in our sample. This framework revolves around three crucial elements: organization dynamics, organizational focus, and the role of innovation. By examining these constructs and their inherent dimensions, we emphasize the importance of adopting radical innovative practices, shifting perspectives towards new patterns of digital transition, and embracing change with a long-term organizational orientation. This would be the ideal scenario, depicted in (b). Additionally, we recognize that SME practices are inherently paradoxical and interconnected, as they embrace disruptive changes while adapting to the external context (Ahmadi & Osman, Citation2020; Alhusen & Bennat, Citation2021; Udomdech et al., Citation2019; Urbanska et al., Citation2021). However, it is also important to refer that it is mandatory for firms to be aware and have resources and capabilities to be prepared to move away from the most basic scenario presented in (a) to embrace change, a long-term innovation orientation and outward organization focus. For that it is clear that public policy needs to be supportive as well.

Considering the economic challenges caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, typically volatile, uncertain, ambiguous, and complex, it is crucial for SMEs to reassess their entire business framework. The new post-pandemic era, following the typical VUCA context, will likely differ significantly from the pre-pandemic era, necessitating adjustments and redirection in strategic planning and business orientation to foster sustainable practices and align visions with future challenges. To optimize the advantages derived from the paradoxical nature of change vs stability, inward vs outward, and radical vs incremental, SMEs must consider the determinants that influence the adoption of these practices, both internally (e.g. management, leadership, capabilities, resources, strategic operations, innovative behavior, technology adoption) and externally (e.g. markets, industries, governmental entities, public policies, financial assistance).

While SMEs are highly adaptable and flexible organizations, this advantage can be a double-edged sword. Their informal structures, centered around the owner or manger, can hinder decision-making. The “liability of smallness” further exacerbates this challenge, as limited resources and specialized knowledge obstructs their ability to make thoughtful long-term decisions. Consequently, these firms may resort to short-term fixes or incremental innovative practices to address immediate problems, neglecting long-term solutions. This approach can provide SMEs temporary relief but can ultimately harm their long-term survivability by overlooking external opportunities and falling behind competitors that prioritize strategic innovation and long-term growth. Furthermore, building and maintain dynamic capabilities is crucial for them to become more resilient to future disruptions.

The lack of formal structures makes SMEs more vulnerable to external shocks, raising questions about applicability of the key themes of our study. First, adopting an outward perspective, embracing change, and pursuing long-term innovation present challenges due to resources constraints. Limited resources translate to deficiencies in market research, competitive analysis, external networks, R&D efforts, and specialized knowledge. Additionally, limited access to external financing hinders internationalization and expansion into new markets. Consequently, their choices to pursue short-term, inward, and stable processes are largely driven by constrains in organizational capabilities, risk management, resources, and financing. Given these complexities, future research should investigate how organizational dynamics, focus, and innovation manifest and are fostered across diverse SMEs.

This paper provides valuable insights from the pandemic crisis to the existing literature, while also categorizing key organizational factors essential for preparing for the emerging post-pandemic normality. However, further research is needed to fully understand the patterns of adaptability and effectiveness exhibited by SMEs in the post-pandemic landscape. Our study highlights the significance of organizational dynamics, organizational focus, and proactive innovative behavior. Despite the dedicated research on SMEs during the pandemic, only a limited number of studies have explored these constructs in the VUCA post-pandemic context. Therefore, future research should address the knowledge gap by investigating how SMEs can successfully adapt to the new reality, the dynamic capabilities needed to embrace the VUCA-based challenges and how owners and managers can pivot their organizational structures to become more competitive. Some of the recommendations are shown in .

Table 4. Recommendation for future research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created this study.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rafael Castro

Rafael Castro received his Bachelor’s degree in Management from IPG, Guarda, followed by a Master’s degree in Economics from the University of Aveiro, Portugal. Currently, he is pursuing his PhD in Marketing and Strategy jointly at the University of Aveiro, University of Minho, and University of Beira Interior (Portugal). His main research interests are strategic management, entrepreneurship, innovation, and small-and-medium sized businesses.

António Carrizo Moreira

António Carrizo Moreira is an Associate Professor with Habilitation at DEGEIT, University of Aveiro, Portugal. António holds an MBA from Porto Business School. He holds a Ph.D. in Management from the University of Manchester, England.

References

- Adam, N. A., & Alarifi, G. (2021). Innovation practices for survival of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in the COVID-19 times: The role of external support. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 10(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-021-00156-6

- Ahmadi, M., & Osman, M. H. M. (2020). Exploitative dominant balanced ambidexterity solving the paradox of innovation strategies in SMEs. International Journal of Business Innovation and Research, 21(1), 79–107. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBIR.2020.104033

- Ahmadi, M., Mohd Osman, M. H., & Aghdam, M. M. (2020). Integrated exploratory factor analysis and data envelopment analysis to evaluate balanced ambidexterity fostering innovation in manufacturing SMEs. Asia Pacific Management Review, 25(3), 142–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2020.06.003

- Al-Fadly, A. (2020). Impact of Covid-19 on SMEs and employment. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 8(2), 629–648. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2020.8.2(38)

- Alhusen, H., & Bennat, T. (2021). Combinatorial innovation modes in SMEs: Mechanisms integrating STI processes into DUI mode learning and the role of regional innovation policy. European Planning Studies, 29(4), 779–805. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2020.1786009

- Alonso-Almeida, M. D. M., & Bremser, K. (2013). Strategic responses of the Spanish hospitality sector to the financial crisis. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 32, 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.05.004

- Alves, J. C., Lok, T. C., Luo, Y., & Hao, W. (2020). Crisis challenges of small firms in Macao during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers of Business Research in China, 14(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11782-020-00094-2

- Alves, M. F. R., & Galina, S. V. R. (2020). Measuring dynamic absorptive capacity in national innovation surveys. Management Decision, 59(2), 463–477. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-05-2019-0560

- Aničić, Z., & Paunović, B. (2022). The Covid-19 crisis and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Serbia: Responsive strategies and significance of the government measures. Journal of East European Management Studies, 27(3), 404–433. https://doi.org/10.5771/0949-6181-2022-3-404

- Ashiru, F., Adegbite, E., Nakpodia, F., & Koporcic, N. (2022). Relational governance mechanisms as enablers of dynamic capabilities in Nigerian SMEs during the COVID-19 crisis. Industrial Marketing Management, 105, 18–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2022.05.011

- Avlonitis, G. J., & Salavou, H. E. (2007). Entrepreneurial orientation of SMEs, product innovativeness, and performance. Journal of Business Research, 60(5), 566–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.01.001

- Ayyagari, M., Beck, T., & Demirguc-Kunt, A. (2007). Small and medium enterprises across the globe. Small Business Economics, 29(4), 415–434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-006-9002-5

- Azar, G., & Ciabuschi, F. (2017). Organizational innovation, technological innovation, and export performance: The effects of innovation radicalness and extensiveness. International Business Review, 26(2), 324–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2016.09.002

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

- Beliaeva, T., Shirokova, G., Wales, W., & Gafforova, E. (2020). Benefiting from economic crisis? Strategic orientation effects, trade-offs, and configurations with resource availability on SME performance. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 16(1), 165–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-018-0499-2

- Bivona, E., & Cruz, M. (2021). Can business model innovation help SMEs in the food and beverage industry to respond to crises? Findings from a Swiss brewery during COVID-19. British Food Journal, 123(11), 3638–3660. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-07-2020-0643

- Bongso, G., & Hartoyo, R. (2022). The urgency of business agility during COVID-19 pandemic: Distribution of small and medium business products and services. Journal of Distribution Science, 20(6), 57–66. https://doi.org/10.15722/jds.20.06.202206.57

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Buekens, W. (2013). Coping with the innovation paradoxes: The challenge for a new game leadership. Procedia Economics and Finance, 6, 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(13)00133-0

- Bundy, J., Pfarrer, M. D., Short, C. E., & Coombs, W. T. (2017). Crises and crisis management: Integration, interpretation, and research development. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1661–1692. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316680030

- Caballero-Morales, S.-O. (2021). Innovation as recovery strategy for SMEs in emerging economies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Research in International Business and Finance, 57, 101396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2021.101396

- Caiazza, R., Phan, P., Lehmann, E., & Etzkowitz, H. (2021). An absorptive capacity-based systems view of Covid-19 in the small business economy. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 17(3), 1419–1439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-021-00753-7