Abstract

The OPEC governments mainly financed their budgets by relying on oil production, similar to many other governments globally. However, the world’s ongoing economic development, changes in countries’ political relationships, and exchange of sanctions could have adverse consequences for government financing, including healthcare. This study investigates whether economic sanctions have shifted governments’ healthcare financing from oil dependence. Quantitative data covering 2000 to 2020 were extracted from the WHO and assessed using a comparison of means Welch’s t-test. The results showed the independence of government healthcare financing from oil in Libya, Iraq, and Iran, evident in the absence of a response to changes in their sanctions programs, attributed to their long experience with sanctions. This is in contrast to Venezuela, where governmental healthcare financing was adversely affected after sanctions were imposed. With global economic uncertainty, continuous political changes, and the global transformation to green energy, this study suggests that countries worldwide maintain financing strategies other than dependence on oil, with constant revisions to global developments.

1. Introduction

Oil production derives the majority of finances from many governments via owned oil companies or by taxing fuel consumption and oil companies. Nearly two-thirds of OECD countries tax fuel at $2 per gallon or more, whereas five of them tax even more than $3 (Energy, 2019). Given the effect of COVID-19 on the oil industry in 2020, when oil prices plummeted to one of the lowest levels in history (Macrotrends, Citation2023), oil revenues exceeded 5% of the gross domestic product (GDP) of 20 countries globally that year (Global Economy, Citation2023). In addition, as per available statistics on global oil revenues, the average share of oil revenues to the GDPs of the world’s top ten countries ranged between 20% and 40% from the 1970s to 2020 (Global Economy, Citation2023). The number of countries with average oil revenue to GDP exceeding 20% could be higher if the average was calculated from the 1980s or the 1990s. These high levels of dependence on such funding sources, with no sustainable alternative in sight, could place government financing under significant pressure during economic turmoil.

Economies worldwide are continually exposed to the effects of global changes that could result from various reasons, such as economic instabilities, the spread of diseases, wars, and geopolitics. Leading countries often use economic sanctions in a way to influence foreign policies (Peksen, Citation2019), which could also be another reason for causing various damage to economies. For instance, the economic sanctions imposed in 2006 on Venezuela decreased GDP growth by 1.1 percentage points the following year (IMF, Citation2023; Seelke, Citation2020). However, the sanctions imposed on Iran in 1980, Libya in 1987, and Iraq in 1990 (Aloosh et al., Citation2019; Collins, Citation2004; Dyson & Cetorelli, Citation2017) caused 21.6%, 14.7%, and 64% reductions in GDPs, respectively, in the following year (IMF, Citation2023; World Bank, Citation2023a). Healthcare financing can be adversely affected by economic sanctions and has long-term ramifications.

Amidst the intricate landscape of heightened global uncertainties, a confluence of factors has intensified the risks linked to exclusive reliance on oil revenues. The far-reaching consequences of the COVID-19-induced economic downturn, the ongoing geopolitical and economic changes, and the rapid momentum towards sustainable energy solutions have accentuated the vulnerabilities inherent in traditional financial models centered around oil, underscoring the imperative for diversification in revenue streams and financial resilience. Against this multifaceted backdrop, where economic landscapes are evolving at an accelerated pace, this study is poised to delve into a critical facet of these financial dynamics by scrutinizing the interplay between economic sanctions, healthcare financing, and oil dependence. Therefore, this study aims to investigate whether intricate challenges posed by geopolitical changes have altered governments’ healthcare financing strategy, moving away from dependence on oil in an ever-changing world.

There is a large body of reliable evidence for healthcare financing. However, there is no evidence on whether economic sanctions have made governments’ healthcare financing independent of oil and whether they pursue alternative sources of financing. Although some studies have highlighted the effect of sanctions on governments and healthcare financing (Akbarialiabad et al., Citation2021; Asgardoon & Amirzade-Iranaq, Citation2022), and others have investigated the effect of sanctions on healthcare financing (Faraji Dizaji & Ghadamgahi, Citation2019), no evidence has contributed to whether sanctions have transmitted government healthcare financing away from dependence on oil.

A probing of the literature revealed more focus on investigating healthcare financing in relation to general healthcare aspects, such as aging and population growth (Jakovljevic et al., Citation2022), healthcare needs growth and sufficient spending (GBD, Citation2017; Reshetnikov et al., Citation2019), mortality (Budhdeo et al., Citation2015), health outcomes (Edney et al., Citation2018), pharmaceutical (Florido Alba et al., Citation2019), specific illness (Peter & Osagie, Citation2017), and affordability of healthcare expenditure, to fill specific gaps in important topics (Johnston et al., Citation2019; Keane et al., Citation2021). The literature is also rich in evidence on the effect of the 2008 financial crisis on healthcare (Jakovljevic et al., Citation2020; Karanikolos et al., Citation2016); for example, the effect of the crisis on suicide, mental health, access to health (Karanikolos et al., Citation2016), unmet healthcare needs (Pappa et al., Citation2013), and healthcare financing among European countries that received financial bailouts (Loughnane et al., Citation2019). However, no evidence of the economic sanctions that shifted governments’ healthcare financing from dependence on oil has yet been obtained.

When economic sanctions are investigated in relation to healthcare, the literature often focuses on indirect indicators, such as services and diseases, rather than financing. For example, the effect of economic sanctions was evident in the literature on life expectancy and mental health (Aloosh et al., Citation2019; Gutmann et al., Citation2021), COVID-19 (Karimi & Turkamani, Citation2021), pharmaceutical (Bastani et al., Citation2022; Setayesh & Mackey, Citation2016), child mortality (Dyson & Cetorelli, Citation2017; Gibbons & Garfield, Citation1999), patients with cancer (Shahabi et al., Citation2015), and access to healthcare (Asadi‐Pooya et al., Citation2022; Sen et al., Citation2013). The literature also provides evidence of the effect of sanctions on healthcare, with a focus on specific regions such as Yugoslavia (Garfield, Citation2001), Cuba (Roshan & Abbasir, Citation2014), Syria (Moret, Citation2015), and Haiti (Gibbons & Garfield, Citation1999), as well as on groups of countries for comparison purposes (Faraji Dizaji & Ghadamgahi, Citation2019; Garfield et al., Citation1995; Peksen, Citation2011).

Despite the valuable contributions of studies on economic sanctions, financial crises, and level of financing in relation to various health aspects, the lack of evidence on whether economic sanctions have made governments’ healthcare financing independent of oil and whether they altered their strategies to alternative sources of financing creates a scientific gap. Advancing the literature by investigating this topic would fill certain knowledge gaps and be a crucial input to government plans to finance healthcare.

The Organization of Petroleum-Exporting Countries (OPEC) includes governments with current or previous economic sanctions. OPEC was founded in 1960 to regulate oil production among its members to ensure a more stable and efficient supply in the oil market (Kisswani et al., Citation2022). This mission was conducted by regulating the production portion of each member with constant revision to ensure that any increase or decrease in their portion was in line with market changes and needs (Kisswani et al., Citation2022). Since the foundation of OPEC, 16 members have joined the group, three of whom have suspended their membership for some time or permanently (OPEC, Citation2023).

There are seven countries with active OPEC membership received economic sanctions at different times. For example, the first economic sanctions imposed on Iran were in 1979 and Libya in 1986 (Aloosh et al., Citation2019; Collins, Citation2004). Iraq and Nigeria received the first sanctions in 1990 and 1992, respectively (Dyson & Cetorelli, Citation2017; Sklar, Citation1997), followed by Angola and Congo in 1993 (European Commission, Citation2023; Reliefweb, Citation2000), and Venezuela in 2006 (Seelke, Citation2020). Sanctions in Libya, Iraq, and Angola were lifted (UN, Citation2002, Citation2010; U.S. Department of the Treasury, Citation2023), whereas those in Iran were lifted for some time and imposed again (Aloosh et al., Citation2019). Venezuela has been sanctioned once (Rosales & Bull, Citation2020; Seelke, Citation2020), whereas Angola, the Congo, and Nigeria have been sanctioned multiple times (European Commission, Citation2023; Human Rights Watch, Citation1997; Reliefweb, Citation2000).

Healthcare systems are financed differently among active OPEC members who received sanctions but appear to be financed more privately. For example, healthcare in Iran is financed by social healthcare insurance and public funds. It is also financed privately, accounting for over half of the system, with a big share of out-of-pocket (OOP) (Dizaj et al., Citation2019; Zare et al., Citation2014). In Libya, the state has provided free healthcare services to citizens since the 1970s and the private sector was later involved in financing (El Taguri et al., Citation2008). When the revolution started in 2011, healthcare suffered from poor funding, and public finance was driven by different governments (El Oakley et al., Citation2013; Médecins Sans Frontières, Citation2016). In Iraq, according to the constitution, the public sector ensures citizens’ universal rights to healthcare (Jaff et al., Citation2018), with the private sector supplementing curative care; however, the private sector now finances most of this system (Al Hilfi et al., Citation2013; WHO, Citation2023b). In Venezuela, healthcare is financed publicly and privately but has one of the highest OOP in the world (Atun et al., Citation2015; Roa, Citation2018). This is similar to Nigeria, where the system is financed through different methods but predominantly through OOP (Uzochukwu et al., Citation2015). In Angola, the healthcare system is primarily financed by the government. It is also financed by nongovernmental organizations, private companies, and donors (Craveiro & Dussault, Citation2016; International Trade Administration, Citation2022). This is similar to the healthcare system in the Congo, where it is financed in different ways, such as the government, implementing partners, OOP, and donors (Laokri et al., Citation2018; Le Gargasson et al., Citation2014).

This study is structured across five integral sections. It commences with the methodology, offering a detailed exposition that elucidates the study design, sample selection, data collection methodologies, and the analytical tools employed. The subsequent results section presents a comprehensive overview of statistical and descriptive analyses, providing valuable insights into the sustainability of healthcare financing among countries. Moving to the discussion, these results undergo interpretation, scrutiny of implications, and the drawing of connections to existing literature, thereby enhancing our comprehension of the subject matter. In addition, the conclusion synthesizes the paramount insights gleaned from the study and proposes avenues for prospective research. Finally, the limitations section conscientiously acknowledges any encountered limitations that may impact the interpretation of the results.

2. Methodology

To serve the purpose of this study, the government healthcare financing to GDP was selected as the primary indicator for analysis, which has ability to demonstrate whether economic sanctions have made government healthcare financing independent of oil. As opposed to the absolute values typically used for investigations in specific countries or diseases (Turner, Citation2017; Zhang et al., Citation2010), this study performed aggregation, which allows for comparison among countries, as it permits the investigation of various explanatory variables and institutional systems (Gerdtham & Jönsson, Citation2000). In addition, the aggregation is more appropriate given that the study investigates whether economic sanctions have shifted government healthcare financing from dependence on oil. This is attributed to its capacity to reveal changes in the proportion of government healthcare financing to GDP, even if the absolute values remain the same, to ensure a better comparison among the countries included in the study. Moreover, the share of healthcare financing to GDP has been widely used in literature to investigate the policy impact on healthcare and the effectiveness of healthcare programs (Jakovljevic et al., Citation2022; Martin et al., Citation2014; Wagstaff et al., Citation2018).

Data on healthcare financing were extracted from the global health expenditure database of the World Health Organization (WHO), with an available period from 2000 to 2020 at the time of the analysis (WHO, Citation2023b). During this period, the OPEC countries that received or lifted economic sanctions while being active members were included in the analysis. This will allow for better capturing of the effect of the sanctions if governments shift healthcare financing away from dependence on oil and ensure a more realistic comparison among countries. This is attributed to the fact that oil production—OPEC’s primary source of income—is regulated, which should eliminate any encounter action by governments to offset the effect of sanctions by increasing oil production. If not controlled for, it might crucially bias the actual effect. Moreover, the study limited the inclusion of countries to those with active membership for at least two years before and after the sanctions’ actions to enable testing of the effect.

This study defines the sanctions’ actions as major changes to the government’s sanctions program, which could be imposed, lifted, or both via the United Nations (UN), the European Union (EU), or the United States Department of the Treasury, either via one party or more. In this study, sanctions actions encompass all measures imposed on governments and economic activities, including all trade embargoes and financial restrictions. These encompass a spectrum of punitive measures directed not only at the governmental apparatus but also at various economic sectors, shaping a multifaceted approach that may include diplomatic isolation, freezing of assets, and restrictions on international trade.

Given the countries’ aforementioned inclusion conditions, Libya, Venezuela, Iraq, and Iran were found to fit within these conditions. For example, sanctions were lifted in Libya in 2004, Iraq in 2010, and Iran in 2015 before resuming in 2018 (Aloosh et al., Citation2019; UN, Citation2010; U.S. Department of the Treasury, Citation2023), where Venezuela received sanctions in 2006 (Seelke, Citation2020). The other three OPEC countries that had experienced sanctions did not fit within the inclusion criteria; therefore, they were excluded. For example, Angola has been an active member of OPEC since 2007 (Kisswani et al., Citation2022) but received sanctions in 1993, and more changes to its program took place in 2002 (Reliefweb, Citation2000; UN, Citation2002). This is similar to Congo, which received sanctions in the 1990s with some changes to its program before becoming a member of OPEC in 2018 (European Commission, Citation2023; Kisswani et al., Citation2022). Moreover, during the period covered in this study, no major changes were perceived in the Nigerian sanction program. Furthermore, it is worth mentioning that this study is fully aware that some countries might have had changes to their sanctions programs within the study period, such as sanctions lifted Iraq in 2003, which were previously imposed by the UN (European Commission, Citation2023). However, this study mainly focuses on major changes in sanction programs.

Statistical analysis categorized the data into two groups: pre- and post-sanctions actions. The analysis did not include the year of imposition or lifting of sanctions. Including this year in the period before or after the sanction action might bias either of them because the timing of the sanctions’ actions, which might include either period of a year with a double effect, should that significantly bias the study results if not controlled. Moreover, turning points emerged as critical milestones indicating substantial shifts in the economic and geopolitical landscapes of the countries under investigation–Venezuela, Libya, Iraq, and Iran. The identification of these turning points was integral to distinguishing pre- and post-sanction actions within each country. Detailed historical timelines for each country were meticulously crafted, chronicling key events leading up to sanction impositions and subsequent post-sanction periods. This comprehensive dataset involved an exhaustive review encompassing diplomatic developments, geopolitical events, and policy changes. The objective was to establish a chronological framework that captured the contextual factors influencing healthcare financing strategies, with exclusion to the turning points periods. This strategic exclusion ensures a concentrated examination of healthcare financing strategies during stable intervals, facilitating a nuanced analysis of trends and patterns. In this study, the independence of government healthcare financing from oil is defined as reporting no response in government healthcare financing to the sanctions’ actions given the condition that oil production among the included countries is controlled, where lifting sanctions is expected to yield an increase in government healthcare financing, as opposed to imposing sanctions.

Based on the available WHO data and to ensure the same period length before and after the sanctions’ actions, the lifting of sanctions was investigated in Libya from 2000 to 2003 as pre-lifting, 2005 to 2008 as post-lifting, and 2004 as the turning point that was not included in the analysis aligning with the lifting of sanctions (U.S. Department of the Treasury, Citation2023). In Venezuela, imposing sanctions was investigated, where the period from 2000 to 2005 was pre-imposing and from 2007 to 2012 was post-imposing, with 2006 as the turning point marked by sanctions imposed (Rosales & Bull, Citation2020; Seelke, Citation2020). In Iraq, the lifting of sanctions was investigated; from 2004 to 2009 was pre-lifting, and from 2011 to 2016 was post-lifting, with 2010 being the turning point coincided with lifting sanctions and reshaping geopolitical dynamics (UN, Citation2010). In Iran which uniquely had two turning points—2015, signifying the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, and 2018, marking the renewal of sanctions (Aloosh et al., Citation2019), lifting and imposing sanctions have been investigated. In lifting sanctions, the period from 2013 to 2014 was pre-lifting, and 2016 to 2017 was post-lifting, with 2015 being the turning point. In imposing sanctions, the period from 2016 to 2017 was pre-imposing, 2019 to 2020 was post-imposing, and 2018 was the turning point.

The mean changes in healthcare financing post-sanction and pre-sanction actions were analyzed using Welch’s t-test. This statistical method was applied to identify significant differences in study indicators, providing a comprehensive assessment of how government healthcare financing responded to sanction actions in the post-sanction period compared to the pre-sanction period for each of the four countries. This test was employed for being capable to measure the significance of the differences between means (Burke et al., Citation2014). Welch’s t-test is also appropriate for measuring the mean changes in two independent groups, especially if the sample size is small, as in the case of this study (Delacre et al., Citation2022). A two-sided t-test was performed, and the significance of the results was indicated at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels. The means of comparisons calculated the difference in the means of the two independent samples—post- to pre-sanction actions—where the significance value (p-value) of the difference was reported. The p-value represents the probability of a difference between the samples if the null hypothesis is true. The null hypothesis was that the difference would be zero. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA software version 14.0.

The study also performed Welch’s t-test on government healthcare financing to total government spending as a second indicator to identify any patterns in government healthcare financing that differ from the study primary indicator. This indicator has also been perceived as a primary indicator of changes in governments’ healthcare financing and was deemed appropriate for comparison among countries (Loughnane et al., Citation2019). This indicator is seen as a core indicator for healthcare financing systems (WHO, Citation2023a) and an important measure for policymakers to observe developments in health outcomes (Edeme et al., Citation2017; Kim & Lane, Citation2013). This study also conducted further descriptive analysis on study both indicators to analyze trends in healthcare financing (Haralayya, Citation2021).

3. Results

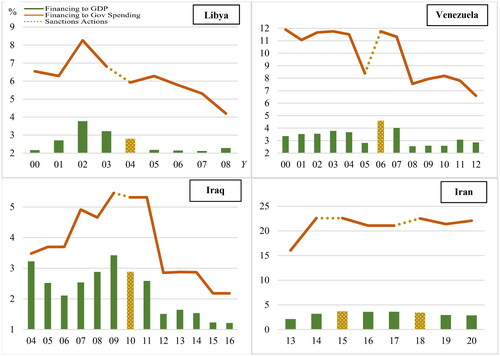

The comparison of the mean results among the included countries indicates approximately the same results in the study’s two indicators (see ), where both have also shown the same trends within the investigated period (see ). For example, the government healthcare financing to GDP in Libya post-lifting the sanctions declined significantly by 0.8% (p = 0.10) compared to the previous period. Simultaneously, government healthcare financing to total government spending declined significantly by 1.6% (p = 0.03) (see ). In addition, both indicators showed declining trends post-lifting compared with pre-lifting (see ).

Table 1. Welch’s t-test results for means changes in governments’ healthcare financing post-sanctions actions compared to pre-sanctions actions.

In Venezuela, government healthcare financing to GDP post-sanctions declined significantly by 0.5% (p = 0.09) compared to pre-sanctions. Meanwhile, the government healthcare financing to total government spending declined significantly by 2.8% (p = 0.00). In addition, both indicators imply declining trends post-sanctions.

In Iraq, government healthcare financing to GDP post-lifting declined significantly by 1.1% (p = 0.00) compared to pre-lifting. Concurrently, the government healthcare financing to total government spending declined significantly by 1.2% (p = 0.05). Moreover, trends in both study indicators showed declines in the post-lifting period compared to the prior period.

In Iran, government healthcare financing to GDP post-lifting of sanctions in 2015 increased by 0.9% (p = 0.33) compared to pre-lifting. Simultaneously, government healthcare financing to total government spending increased by 1.7% (p = 0.68). Furthermore, government healthcare financing to GDP post-sanctions in 2018 declined significantly by 0.7% (p = 0.01) compared to pre-sanctions. During the same period, the government healthcare financing to total government spending increased by 0.6% (p = 0.30). In addition, both study indicators showed upward trends post-lifting sanctions in 2015, but post-imposing sanctions in 2018, upward trends were shown only in government healthcare financing to total government spending.

4. Discussion

Throughout the study period, government healthcare financing in the majority of the investigated countries revealed independence from oil, which was obvious in the absence of a response to economic sanctions’ actions, by varying degrees of response among countries. With the anticipated burdens or eases that sanctions’ actions could cause to economies, surprisingly, the government healthcare financing in Libya, Iraq, and Iran in both study indicators either showed significant declines in periods post-sanction actions or stability in financing. For example, both study indicators showed significant declines in Libya and Iraq post-lifting sanctions, while they showed more stability in Iran, given that the sanctions were lifted and imposed again. However, Venezuela was the only country that responded to the imposed sanctions, where both study indicators declined significantly post imposing sanctions, implying their dependence on oil for financing. These results suggest that governments with long experience with economic sanctions have freed their government healthcare financing from dependence on oil. This long experience could have led governments to set financing strategies that made them resilient to ongoing global economic and political developments compared to governments with no previous experience.

For instance, in the investigated period from 2013 to 2020 in Iran, the study both indicators showed broad stability, given that the country went through three periods of sanctions, ignoring the rebounding world economies after the 2008 financial crisis when oil prices increased to levels above $100 up to 2014 (Macrotrends, Citation2023). Neither did they respond to the following plummet in oil prices, which declined to a low of $20 in 2016 (see ). None of the study indicators responded either to the COVID-19 outbreak or its ramifications on economies (Ceylan et al., Citation2020; Qin et al., Citation2021). In fact, the country’s economy did not respond to the pandemic; the GDP increased by 3.3% during the pandemic, while the world economies shrank by 3.1% that year (World Bank, Citation2023a). Such stability in government healthcare financing, with no response to crucial global economic changes, suggests that the country’s experience of sanctions since 1979 has made government healthcare financing independent of oil (Aloosh et al., Citation2019).

Government healthcare financing in Libya declined post-lifting the sanctions when the government could have benefited from the country’s stabilized economic and political situation post-lifting the sanctions (Kreiw, Citation2019) and the oil prices that traded between $80 and above $150 before the outbreak of the 2008 financial crisis to increase healthcare financing or alleviate some of the declines (Macrotrends, Citation2023). The unanticipated contradictory response to lifting sanctions by study both indicators suggests that government healthcare financing could have been independent of oil, encouraged by the government’s experience with the economic sanctions that first took place in 1987 (Collins, Citation2004).

In Iraq, it was also expected that the government would benefit from lifting sanctions post-2010 to increase healthcare financing, given that oil prices exceeded $150 when the world economy rebounded after the 2008 financial crisis (Macrotrends, Citation2023). This could be attributed to the country being one of the top oil producers (Statista, Citation2023) and having the largest share of oil revenue to GDP globally (U.S. Department of Energy, Citation2019; World Bank, Citation2023b). However, both indicators declined significantly post-lifting sanctions, indicating that government healthcare financing is independent of oil. The contrary response of the two indicators suggests that government healthcare financing could have been financed via resources other than oil due to the government’s long period under sanctions that exceeded 20 years (Dyson & Cetorelli, Citation2017). The observed contrary response could also be due to the country’s political instability post-lifting sanctions, which could have prevented the economy from reaching its full potential production capacity (Thgeel, Citation2021). Another reason could be the healthcare system has transformed to be more privately financed, where the private healthcare financing share to total healthcare financing has increased significantly since 2012 (Al Hilfi et al., Citation2013; WHO, Citation2023b).

On the other hand, Venezuela was the only country where government healthcare financing was adversely affected by imposing sanctions, consequently increasing the private healthcare financing share to total healthcare financing (WHO, Citation2023b). Although government healthcare financing could have been affected by the financial crisis, overall financing showed downward trends post-sanctions, and except for 2007, neither of the two indicators showed financing levels post-sanctions higher than pre-sanctions (see ). This response suggests that government healthcare financing could have been dependent on oil, as no previous experience with sanctions has urged the government to utilize alternative financing resources.

The literature review highlighted that the increase in government healthcare financing to GDP could be due to a decrease in GDP (Faraji Dizaji & Ghadamgahi, Citation2019). To control for this effect, this study performed analysis on government healthcare financing to GDP and to total government spending, where both indicators gave broadly similar results (see ). Moreover, both indicators were investigated in line with GDP growth and government’s total actual spending to observe any different trends. Only in Libya did government healthcare financing to GDP change differently from GDP growth, though the difference was low and observed only pre-lifting sanctions (Country Economy, Citation2023; WHO, Citation2023b; World Bank, Citation2023a). Government healthcare financing to total government spending also changed differently from government’s total actual spending; nonetheless, the contrary changes were marginal because of the small change in government’s total actual spending (Country Economy, Citation2023; WHO, Citation2023b).

In Iraq, government healthcare financing to GDP and to total government spending followed the same pattern as GDP growth and government’s total actual spending or showed no changes. Different trends were observed in 2012 and 2016, where government healthcare financing to GDP declined to 1% in both years due to the high increase in GDP, and government healthcare financing to total government spending declined to 2.5% in 2012 due to the high increase in government’s total actual spending that year (Country Economy, Citation2023; WHO, Citation2023b; World Bank, Citation2023a). In Iran, the government healthcare financing to GDP throughout the investigated period was stable at levels between 3% and 3.5%, even with changes in GDP, where no contrary trend was observed (WHO, Citation2023b; World Bank, Citation2023a). This is similar to the government healthcare financing to total government spending, which was maintained at 20% with marginal changes, given the constant and high increases in government’s total actual spending (Country Economy, Citation2023; WHO, Citation2023b). In Venezuela, no contrary trends are observed for GDP growth or total government’s total actual spending (Country Economy, Citation2023; WHO, Citation2023b; World Bank, Citation2023a).

Among the investigated countries, only government healthcare financing in Iran showed independence from oil, with stability in financing during the investigated period, given the three different periods of sanctions the economy went through, indicating a positive experience with sanctions. The imposition of sanctions could indeed have put the economy under pressure, as reflected in the country’s long period of hyperinflation and depreciation in its currency value (Hemmati et al., Citation2023; Ture & Khazaei, Citation2022). In addition, running the economy with oil independence could have led to dismiss a greater chance for the economy to reach its full potential production capacity, which could have otherwise stimulated growth and increased the size of the economy. However, being among the largest 40s economies in the world -at the time of conducting this study (World Bank, Citation2021), with independence from oil implies strength in the government-maintained financing strategy. It also indicates the possibility of other countries, across the world particularly those highly dependent on oil, maintaining financing strategies that could make them independent of oil and resilient to global economic and political changes, especially with the world transforming to green energy (Su et al., Citation2023).

5. Conclusion

This study examines whether economic sanctions have shifted governments’ healthcare financing from dependence on oil. With the varying effect of sanctions on the investigated countries, most governments have shifted their healthcare financing from dependence on oil, evident in the absent response to sanctions’ actions. The long experiences of Libya, Iraq, and Iran with sanctions could have urged them to maintain healthcare financing strategies to utilize resources other than oil.

In contrast to Venezuela, where government healthcare financing post-sanctions struggled to maintain financing levels as prior, since it was the country’s first experience with sanctions, indicating a high dependence on oil for financing. Subsequently, the share of private healthcare financing to total financing increased significantly, which should temporarily alleviate the pressure on government healthcare financing. However, such a shift could have adverse consequences for the healthcare system in the long term.

The shortsighted nature of government healthcare financing and the irregular revision of measures to the world’s economic and political developments could make government healthcare financing unable to meet internal or external shocks that could deteriorate healthcare conditions unless such approaches are reversed. The economic uncertainty that is driven by COVID-19, the war in Ukraine, world inflation with its extended ramifications on financial markets, in addition to the world percentage of aging, population growth, and spread of chronic diseases, might cause further burdens on government healthcare financing in the medium and long term.

Given such challenges with the instability of oil prices and the world’s transformation to green energy, this study suggests that countries dependent on oil for financing should not focus on short term financing plans but should urge maintaining financing strategies that free their healthcare financing from dependence on oil with continuous revision of the world’s ongoing changes. It also suggests further investigation of the Iranian healthcare system to understand the potential reforms applied and what strategies have been utilized to maintain stabilized levels of government healthcare financing given the changes to their sanctions program.

6. Study limitations

While this study provides valuable insights into the dynamics of government healthcare financing amid economic sanctions, it is essential to acknowledge certain limitations that may impact the interpretation of the results. Firstly, the study relies on a short period of historical data in some countries, which might affect the quality of the results. Additionally, the scope of the study is limited to four countries—Venezuela, Libya, Iraq, and Iran—potentially restricting the generalizability of the findings. The geopolitical landscape is dynamic, and unforeseen events or policy changes could influence government healthcare financing strategies beyond the scope of this study. Furthermore, the exclusion of certain turning points in the analysis, while providing a focused examination, might overlook nuances that could affect the overall understanding of the subject matter. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the results and implications of the study.

Disclosure statement

There are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Salem Al Mustanyir

Dr. Salem Al Mustanyir, a senior economist, brings extensive experience from various national and international companies, universities, and public organizations. His wide expertise encompasses economics, accounting, finance, investment, insurance, risk management, business intelligence, data, and artificial intelligence. Dr. Al Mustanyir’s research focus spans a broad spectrum, covering areas such as health economics, sustainable finance, economic of data, energy and oil markets, smart cities, investment in artificial intelligence, labor market, policy impact assessment, and the development of performance indices for public and private sectors.

References

- Akbarialiabad, H., Rastegar, A., & Bastani, B. (2021). How sanctions have impacted Iranian healthcare sector: A brief review. Archives of Iranian Medicine, 24(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.34172/aim.2021.09

- Al Hilfi, T. K., Lafta, R., & Burnham, G. (2013). Health services in Iraq. Lancet (London, England), 381(9870), 939–948. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60320-7

- Aloosh, M., Salavati, A., & Aloosh, A. (2019). Economic sanctions threaten population health: The case of Iran. Public Health, 169, 10–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2019.01.006

- Asadi‐Pooya, A. A., Nazari, M., & Damabi, N. M. (2022). Effects of the international economic sanctions on access to medicine of the Iranian people: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 47(12), 1945–1951. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.13813

- Asgardoon, M. H., & Amirzade-Iranaq, M. H. (2022). Adverse impacts of imposing international economic sanctions on health. Archives of Iranian Medicine, 25, 182–190.

- Atun, R., de Andrade, L. O. M., Almeida, G., Cotlear, D., Dmytraczenko, T., Frenz, P., Garcia, P., Gómez-Dantés, O., Knaul, F. M., Muntaner, C., de Paula, J. B., Rígoli, F., Serrate, P. C.-F., & Wagstaff, A. (2015). Health-system reform and universal health coverage in Latin America. Lancet (London, England), 385(9974), 1230–1247. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61646-9

- Bastani, P., Dehghan, Z., Kashfi, S. M., Dorosti, H., Mohammadpour, M., & Mehralian, G. (2022). Challenge of politico-economic sanctions on pharmaceutical procurement in Iran: A qualitative study. Iranian Journal of Medical Sciences, 47(2), 152–161. https://doi.org/10.30476/IJMS.2021.89901.2078

- Budhdeo, S., Watkins, J., Atun, R., Williams, C., Zeltner, T., & Maruthappu, M. (2015). Changes in government spending on healthcare and population mortality in the European Union, 1995–2010: A cross-sectional ecological study. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 108(12), 490–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076815600907

- Burke, S., Thomas, S., Barry, S., & Keegan, C. (2014). Indicators of health system coverage and activity in Ireland during the economic crisis 2008–2014: From “more with less” to “less with less. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 117(3), 275–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.07.001

- Ceylan, R. F., Ozkan, B., & Mulazimogullari, E. (2020). Historical evidence for economic effects of COVID-19. The European Journal of Health Economics, 21, 817–823.

- Collins, S. D. (2004). Dissuading state support of terrorism: Strikes or sanctions? (An analysis of dissuasion measures employed against Libya). Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 27(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10576100490262115

- Country Economy. (2023). Genqeral government expenditure. https://countryeconomy.com/government/expenditure

- Craveiro, I., & Dussault, G. (2016). The impact of global health initiatives on the health system in Angola. Global Public Health, 11(4), 475–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2015.1128957

- Delacre, M., Lakens, D., & Leys, C. (2022). Correction: Why psychologists should by default use Welch’s t-test instead of Student’s t-test. International Review of Social Psychology, 35, 92–101.

- Dizaj, J. Y., Anbari, Z., Karyani, A. K., & Mohammadzade, Y. (2019). Targeted subsidy plan and Kakwani index in Iran health system. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 8, 98–107.

- Dyson, T., & Cetorelli, V. (2017). Changing views on child mortality and economic sanctions in Iraq: A history of lies, damned lies, and statistics. BMJ Global Health, 2(2), e000311. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000311

- Edeme, R. K., Emecheta, C., & Omeje, M. O. (2017). Public health expenditure and health outcomes in Nigeria. American Journal of Biomedical Science & Research, 5, 96–102.

- Edney, L. C., Haji Ali Afzali, H. H. A., Cheng, T. C., & Karnon, J. (2018). Mortality reductions from marginal increases in public spending on health. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 122(8), 892–899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.04.011

- El Oakley, R. M., & Ghrew, M. H., et al. (2013). Consultation on the Libyan health systems: Towards patient-centred services. The Libyan Journal of Medicine, 8, 57–65.

- El Taguri, A., Elkhammas, E., Bakoush, O., Ashammakhi, N., Baccoush, M., & Betilmal, I. (2008). Libyan national health services the need to move to management-by-objectives. The Libyan Journal of Medicine, 3(2), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.4176/080301

- European Commission. (2023). EU sanctions map. https://www.sanctionsmap.eu/#/main/page/legend

- Faraji Dizaji, S., & Ghadamgahi, Z. S. (2019). The impact of economic sanctions on public health expenditure (evidence of developing resource-exporting countries). Economic Research, 19, 71–107.

- Florido Alba, F., García-Agua Soler, N., Martín Reyes, Á., & García Ruiz, A. J. (2019). Crisis, public spending on health and policy. Revista Española de Salud Pública, 93.

- Garfield, R. (2001). Economic sanctions on Yugoslavia. Lancet (London, England), 358(9281), 580. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05713-0

- Garfield, R., Devin, J., & Fausey, J. (1995). The health impact of economic sanctions. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 72(2), 454–469.

- Gerdtham, U.-G., & Jönsson, B. (2000). International comparisons of health expenditure: Theory, data, and econometric analysis. Handbook of Health Economics, 1, 11–53.

- Gibbons, E., & Garfield, R. (1999). The impact of economic sanctions on health and human rights in Haiti, 1991–1994. American Journal of Public Health, 89(10), 1499–1504. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.89.10.1499

- GBD. (2017). Evolution and patterns of global health financing 1995–2014: Development assistance for health, and government, prepaid private, and out-of-pocket health spending in 184 countries. Lancet (London, England), 389(10083), 1981–2004. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30874-7

- GBD. (2017). Future and potential spending on health 2015–40: Development assistance for health, and government, prepaid private, and out-of-pocket health spending in 184 countries. Lancet (London, England), 389(10083), 2005–2030. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30873-5

- Global Economy. (2023). Oil revenue: Country rankings. https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/oil_revenue/

- Gutmann, J., Neuenkirch, M., & Neumeier, F. (2021). Sanctioned to death? The impact of economic sanctions on life expectancy and its gender gap. The Journal of Development Studies, 57(1), 139–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2020.1746277

- Haralayya, B. (2021). Study on trend analysis at John Deere. Iconic Research and Engineering Journals, 5, 171–181.

- Hemmati, M., Tabrizy, S. S., & Tarverdi, Y. (2023). Inflation in Iran: An empirical assessment of the key determinants. Journal of Economic Studies, 50(8), 1710–1729.

- Human Rights Watch. (1997). The role of the international community. https://www.hrw.org/legacy/reports/1997/nigeria/Nigeria-10.htm

- International Trade Administration. (2022). Angola—Country commercial guide, infrastructure in healthcare sector. https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/angola-infrastructure-healthcare-sector

- IMF. (2023). Real GDP growth, Annual percent change. https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDP_RPCH@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD

- Jaff, D., & Tumlinson, K., et al. (2018). Challenges to the Iraqi health system call for reform. Hamadan, A. Health System, 3, 9–12.

- Jakovljevic, M., Lamnisos, D., Westerman, R., Chattu, V. K., & Cerda, A. (2022). Future health spending forecast in leading emerging BRICS markets in 2030: Health policy implications. Health Research Policy and Systems, 20(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-022-00822-5

- Jakovljevic, M., Timofeyev, Y., Ranabhat, C. L., Fernandes, P. O., Teixeira, J. P., Rancic, N., & Reshetnikov, V. (2020). Real GDP growth rates and healthcare spending: Comparison between the G7 and the EM7 countries. Globalization and Health, 16(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00590-3

- Johnston, B. M., Burke, S., Barry, S., Normand, C., Ní Fhallúin, M. N., & Thomas, S. (2019). Private health expenditure in Ireland: Assessing the affordability of private financing of health care. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 123(10), 963–969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.08.002

- Karanikolos, M., Heino, P., McKee, M., Stuckler, D., & Legido-Quigley, H. (2016). Effects of the global financial crisis on health in high-income OECD countries: A narrative review. International Journal of Health Services: Planning, Administration, Evaluation, 46(2), 208–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020731416637160

- Karimi, A., & Turkamani, H. S. (2021). U.S.-imposed economic sanctions on Iran in the COVID-19 crisis from the human rights perspective. International Journal of Health Services: Planning, Administration, Evaluation, 51(4), 570–572. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207314211024912

- Keane, C., Regan, M., & Walsh, B. (2021). Failure to take-up public healthcare entitlements: Evidence from the medical card system in Ireland. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 281, 114069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114069

- Kim, T. K., & Lane, S. R. (2013). Government health expenditure and public health outcomes: A comparative study among 17 countries and implications for US health care reform. American International Journal of Contemporary Research, 3, 8–13.

- Kisswani, K. M., Lahiani, A., & Mefteh-Wali, S. (2022). An analysis of OPEC oil production reaction to non-OPEC oil supply. Resources Policy. 77, 102653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.102653

- Kreiw, R. (2019). Impact of the political instability on the Libyan economy. Knowledge International Journal, 31(1), 61–67. https://doi.org/10.35120/kij310161k

- Laokri, S., Soelaeman, R., & Hotchkiss, D. R. (2018). Assessing out-of-pocket expenditures for primary health care: How responsive is the Democratic Republic of Congo health system to providing financial risk protection? BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 451. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3211-x

- Le Gargasson, J. B., Mibulumukini, B., Gessner, B. D., & Colombini, A. (2014). Budget process bottlenecks for immunization financing in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Vaccine, 32(9), 1036–1042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.12.036

- Loughnane, C., Murphy, A., Mulcahy, M., McInerney, C., & Walshe, V. (2019). Have bailouts shifted the burden of paying for healthcare from the state onto individuals? Irish Journal of Medical Science, 188(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-018-1798-x

- Macrotrends. (2023). Crude oil prices: 70-year historical chart. https://www.macrotrends.net/1369/crude-oil-price-history-chart

- Martin, A. B., Hartman, M., Whittle, L., & Catlin, A. (2014). National health spending in 2012: Rate of health spending growth remained low for the fourth consecutive year. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 33(1), 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1254

- Moret, E. S. (2015). Humanitarian impacts of economic sanctions on Iran and Syria. European Security, 24(1), 120–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2014.893427

- Médecins Sans Frontières. (2016). Health system in a state of hidden crisis. https://www.msf.org/libya-health-system-state-hidden-crisis

- OPEC. (2023). OPEC brief history. https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/about_us/24.htm

- Pappa, E., Kontodimopoulos, N., Papadopoulos, A., Tountas, Y., & Niakas, D. (2013). Investigating unmet health needs in primary health care services in a representative sample of the Greek population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10(5), 2017–2027. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10052017

- Peksen, D. (2011). Economic sanctions and human security: The public health effect of economic sanctions. Foreign Policy Analysis, 7(3), 237–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-8594.2011.00136.x

- Peksen, D. (2019). When do imposed economic sanctions work? A critical review of the sanctions effectiveness literature. Defence and Peace Economics, 30(6), 635–647. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2019.1625250

- Peter, S. I., & Osagie, O. (2017). Impact of government healthcare financing on tuberculosis in Nigeria. Yobe Journal of Economics, 4, 93–105.

- Qin, X., Godil, D. I., Khan, M. K., Sarwat, S., Alam, S., & Janjua, L. (2021). Investigating the effects of COVID-19 and public health expenditure on global supply chain operations: An empirical study. Operations Management Research, 15(1-2), 195–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-020-00177-6

- Reliefweb. (2000). The UN sanctions committee on Angola: Lessons learned? https://reliefweb.int/report/angola/un-sanctions-committee-angola-lessons-learned

- Reshetnikov, V., Arsentyev, E., Boljevic, S., Timofeyev, Y., & Jakovljević, M. (2019). Analysis of the financing of Russian health care over the past 100 years. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. MDPI, 16, 1848–1853.

- Roa, A. C. (2018). The health system in Venezuela: A patient without medication? Cadernos de Saude Publica, 34(3), e00058517. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00058517

- Rosales, A., & Bull, B. (2020). Into the shadows: Sanctions, rentierism, and economic informalization in Venezuela. European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, 0(109), 107–133. https://doi.org/10.32992/erlacs.10556

- Roshan, N. A., & Abbasir, M. (2014). The impact of the US economic sanctions on health in Cuba. International Journal of Resistive Economics, 2, 20–37.

- Seelke, C. R. (2020). Venezuela: Overview of US sanctions. Current Politics and Economics of South and Central America, 13, 21–27.

- Sen, K., Al-Faisal, W., & AlSaleh, Y. (2013). Syria: Effects of conflict and sanctions on public health. Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England), 35(2), 195–199. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fds090

- Setayesh, S., & Mackey, T. K. (2016). Addressing the impact of economic sanctions on Iranian drug shortages in the joint comprehensive plan of action: Promoting access to medicines and health diplomacy. Globalization and Health, 12(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-016-0168-6

- Shahabi, S., Fazlalizadeh, H., Stedman, J., Chuang, L., Shariftabrizi, A., & Ram, R. (2015). The impact of international economic sanctions on Iranian cancer healthcare. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 119(10), 1309–1318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.08.012

- Sklar, R. L. (1997). An elusive target: Nigeria fends off sanctions. RASPOS, 4, 19–38.

- Statista. (2023). Daily production of crude oil in OPEC countries from 2012 to 2021. https://www.statista.com/statistics/271821/daily-oil-production-output-of-opec-countries

- Su, C. W., Chen, Y., Hu, J., Chang, T., & Umar, M. (2023). Can the green bond market enter a new era under the fluctuation of oil price? Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 36(1), 536–561. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2022.2077794

- Thgeel, A. (2021). Ten years after the Arab Spring political and security reflection in Iraq. https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/amman/17676.pdf

- Ture, H. E., & Khazaei, A. R. (2022). Determinants of inflation in Iran and policies to curb it. IMF Working Papers, 2022(181), 1. https://doi.org/10.5089/9798400220555.001

- Turner, B. (2017). The new system of health accounts in Ireland: What does it all mean? Irish Journal of Medical Science, 186(3), 533–540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-016-1519-2

- UN. (2002). Angola: Security Council lifts sanctions against UNITA. https://news.un.org/en/story/2002/12/53702-angola-security-council-lifts-sanctions-against-unita

- UN. (2010). Security Council takes action to end Iraq sanctions, terminate oil-for-food programme as members recognize ‘major changes’ since 1990. https://press.un.org/en/2010/sc10118.doc.htm

- U.S. Department of Energy. (2019). Fuel taxes by country. https://afdc.energy.gov/data/10327

- U.S. Department of the Treasury. (2023). U.S. announces easing and lifting of sanctions against Libya Treasury to issue general license lifting much of economic embargo. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/js1457

- Uzochukwu, B. S., Ughasoro, M. D., Etiaba, E., Okwuosa, C., Envuladu, E., & Onwujekwe, O. E. (2015). Health care financing in Nigeria: Implications for achieving universal health coverage. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice, 18(4), 437–444. https://doi.org/10.4103/1119-3077.154196

- Wagstaff, A., Flores, G., Hsu, J., Smitz, M.-F., Chepynoga, K., Buisman, L. R., van Wilgenburg, K., & Eozenou, P. (2018). Progress on catastrophic health spending in 133 countries: A retrospective observational study. The Lancet. Global Health, 6(2), e169–e179. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30429-1

- WHO. (2023a). General government expenditure on health as a percentage of total expenditure on health. https://www.who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry/imr-details/92

- WHO. (2023b). Global health expenditure database. https://apps.who.int/nha/database/Select/Indicators/en

- World Bank. (2021). GDP (Current US$). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?most_recent_value_desc=true&year_high_desc=true

- World Bank. (2023a). GDP growth (annual %). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG

- World Bank. (2023b). The World Bank in Iraq. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/iraq/overview

- Zare, H., Trujillo, A. J., Driessen, J., Ghasemi, M., & Gallego, G. (2014). Health inequalities and development plans in Iran: An analysis of the past three decades (1984–2010). International Journal for Equity in Health, 13(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-13-42

- Zhang, P., Zhang, X., Brown, J., Vistisen, D., Sicree, R., Shaw, J., & Nichols, G. (2010). Global healthcare expenditure on diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 87(3), 293–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2010.01.026