Abstract

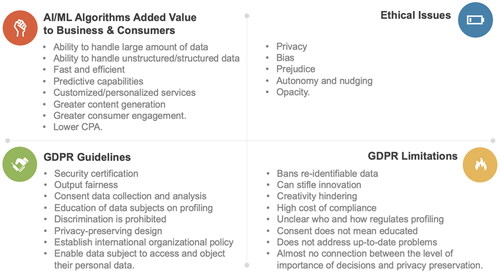

This research investigates the ethical and privacy issues arising from using AI andML in neuromarketing, framed by rule utilitarianism. It assesses the impact of these technologies on consumerprivacy and human rights through a combination of literature review, bibliometric analysis, and empirical data fromsurveys and interviews with experts in the US and Spain. The study reveals the tensions between the efficacy ofneuromarketing techniques and the imperative to protect consumer privacy, particularly in light of the GDPR’sinfluence on global practices. It emphasizes the need for internationally consistent ethical standards and consumerdata regulations, drawing from the comparative analysis of policies in the US and EU. The outcomes include policyrecommendations to minimize ethical risks and promote the responsible progression of neuromarketing. Theserecommendations guide companies and managers toward ethical transparency and accountability. Additionally, theresearch offers a policy framework for crafting ethical neuromarketing practices that reconcile technological progresswith consumer well-being, thereby contributing to broader discussions on embedding ethics within technological innovation.

IMPACT STATEMENT

Advances in neurotechnology are revolutionizing marketing strategies, allowing businesses to predict and influence consumer behavior with remarkable accuracy. This paper investigates the ethical challenges and privacy concerns associated with using artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) in neuromarketing. Through a comprehensive literature review and expert interviews, it explores how these technologies intersect with consumer rights and offers policy recommendations to address ethical dilemmas. This research examines the balance between marketing innovation and the safeguarding of individual privacy, contributing to the ongoing debate on the ethical use of AI in understanding consumer preferences.

1. Introduction

Neuromarketing is a quickly evolving research sector. Marketers now recognize that brain and biometric research can lead to a more in-depth understanding of consumer behavior and preferences (Fisher et al., Citation2010; de Oliveira & Giraldi, Citation2017; Srivastava et al., Citation2020; Pluta-Olearnik & Szulga, Citation2022; Sheth, Citation2021). While the sector is fast growing internationally, the US is one of the most significant regions in the global neuromarketing market, owing to end-user industries’ growing number of US-based market vendors and high investment in digital marketing (GMarket Data Forecast, Citation2022; Sengur & Goncalves, Citation2023). In this regard, neuromarketing strategies and applications are applied in several fields, such as market and marketing research, consumer behavior and preferences, and criminal justice.

Although neuromarketing research has developed, the current studies need more comprehensive insights into neuromarketing and marketing mix. Scholars (Alsharif et al., Citation2022; Goncalves et al., Citation2022; Alsharif et al., Citation2023a) have contributed significantly to the field, providing a comprehensive overview of neuromarketing, classification of neuroimaging and physiological tools that are currently used in the marketing mix, and highlighted neural responses of consumer’s behavior, such as emotions, attention, motivation, reward processing, and perception, to be considered in the marketing mix (Kaul, Citation2022). Their findings confirm the reliability of several tools in studying the marketing mix, such as advertising, brand, price, and product, including but not limited to electroencephalography, eye tracking, galvanic skin reaction (GSR), face coding, and many others. It is known today that the frontal and temporal gyri are correlated with pleasure/displeasure and high/low arousal. At the same time, the occipital lobe is linked to attention processes, and the hippocampus relates to long and short-term memory. Such findings provide valuable insights into the neural responses in marketing mix research.

This paper defines neuromarketing as the scientific study of the nervous system applied to marketing. It measures physiological and neural signals to gain insight into consumers’ behavior, motivations, preferences, and decisions, which can inform innovative advertising, product development, pricing, and other marketing areas. It utilizes brain imaging, scanning, or other brain measurement technologies to collect consumers’ reactions to marketing stimuli and evade the challenges of depending on consumers’ self-reports (Harrell, Citation2019; Brenninkmeijer et al., Citation2020; Parrish et al., Citation2020; Frederick, Citation2022; Halkiopoulos et al., Citation2022). Despite the large array of marketing research methods, through the use of neuroscience lab techniques, scientists, academics, and now marketers have realized that the answers given by the consumers are likely biased or skewed, consciously or unconsciously, due to the influence of stereotypes, cognitive biases, emotions, social and moral norms, and many other factors (BrandWatch, Citation2019; Casado-Aranda & Sanchez-Fernandez, Citation2022; Strieder, Citation2022).

Artificial intelligence (AI) has been used since the first half of the twentieth century. Many scholars have delineated technologies emulating the human brain to perform complex data analysis and decision-making tasks (Benbya et al., Citation2021; Berente et al., Citation2021; Nishant et al., Citation2023; Sengur & Goncalves, Citation2023). Over the decades, AI has been boosted and adjusted to perform more specific tasks like flying airplanes, driving cars, and analyzing complex data (Bhalla et al., Citation2020). Machine learning (ML) is an artificial intelligence subset related to statistics and data analysis (Ongsulee, Citation2017). ML algorithms are capable of learning patterns from training data sets, which can then be applied to various settings and targets such as populations, internet search engines, email filters, web-based services personalization and recommendations, banking and financial applications, and an ever-growing large array of applications running on digital devices. These algorithms are disseminated widely in the advertisement and marketing sectors, assisting throughout the consumer life cycle, learning continuously, much like humans, absorbing more knowledge, and becoming more intelligent. The more unstructured data the AI/ML algorithms process, the more precise the output they provide to users (Kietzmann et al., Citation2018; Neal et al., Citation2023).

Greater availability of neuromarketing technologies and often embedded AI software enables marketers to reduce the time spent analyzing consumer behavior and preferences, segmentation, and organizing targeting campaigns, thus increasing the marketing department’s productivity ratio. The general belief is that neuromarketing technologies and AI algorithms improve marketing and sales operations, consumer service, and personalization (Galli, Citation2022). AI and its elements are widely utilized throughout neuromarketing development and applications, from segmentation through direct marketing and targeting campaigns to relying on AI shopping assistants and chatbots. However, ML algorithms are mainly applied in the phases of segmentation and targeting due to their predictive and optimization abilities (Ma & Sun, Citation2020; Chang & Fan, Citation2023). Despite comprehensive studies on undermining social values and ethical considerations posed by chatbots and interactive AI/ML algorithms, they are occasionally underrated since they remain pretty hidden from the broader audience, users, and consumers.

Consumer emotion recognition-based experiments observe a tendency to investigate frontal and prefrontal cortex signals (Mouammine & Azdimousa, Citation2019). Many researchers found the use of electroencephalogram (EEG) favorable over functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in video advertisement-based neuromarketing experiments (Khurana et al., Citation2021; Yarosh et al., Citation2021; Alsharif et al., Citation2022; Alsharif et al., Citation2023b; Goncalves et al., Citation2023) due to its low cost and high time resolution advantages. Physiological response measuring techniques such as eye-tracking (ET), galvanic skin reaction (GSR) recording, heart rate (HR) monitoring, and facial mapping have also been found in these empirical studies exclusively or parallel with brain recordings (Kaheh et al., Citation2021; Şik & Soba, Citation2021; Goncalves et al., Citation2022). In consumer response prediction and classification, Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), Naïve Bayes, k-Nearest Neighbor (KNN), and Hidden Markov Model (HMM) have been performed with the highest average accuracy among other ML algorithms (Rawnaque et al., Citation2020; Raj et al., Citation2022; Kabanda, Citation2023). Corporations like Coca-Cola, Nestle, Proctor and Gamble, General Motors, Campbell, Frito-Lay, PayPal, Walmart, Home Depot, IKEA, and Target, to name a few, have all been noted as organizations that are actively engaging in neuromarketing research and AI/ML implantations. Such technologies and algorithms raise ethical concerns despite only a few public case studies exist to inform the public about them (Gurgu et al., Citation2020; Goncalves et al., Citation2022).

Despite AI/ML’s ubiquity across various technologies, industries, and healthcare, no comprehensive federal legislation regulates it in the US (Forrest, Citation2021). The executive branch continues to adopt directives and rulemaking that will impact the use of AI/ML. The US Congress has enacted and is considering several legislations regulating certain aspects of AI. In February 2020, the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) petitioned the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to conduct rulemaking concerning AI in commerce to define and prevent consumer harm from AI/ML products (Zhu & Lehot, Citation2022). Much of the governing legal framework is through cross-applicating rules and regulations governing traditional disciplines such as product liability, data privacy, intellectual property, discrimination, and workplace rights. Self-regulation and standards groups also contribute to the governing framework. In the context of recent advances in AI and the launch of policy documents and ethics guidelines worldwide, regulations must be developed in the US (Zhu & Lehot, Citation2022).

The European Union (EU), since 2017, has been working on its approach to AI (Ulnicane, Citation2022), developing key policy documents and strategically positioning it vis-à-vis other global players. The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) will affect AI companies that meet the established criteria for the EU. Article 22 of the GDPR states that a ‘data subject shall have the right not to be subject to a decision based solely on automated processing, including profiling, which produces legal effects concerning him or her or similarly significantly affects him or her’ unless certain conditions are present. One permitted setting is based on express and informed consent by the data subject. GDPR’s Article 22 will likely affect how companies approach AI transparency and bias (Zhu & Lehot, Citation2022).

Following Cambridge Analytica’s Facebook crisis in 2018, emphasis has shifted to the ethics of algorithms (Confessore, Citation2018), as the adoption of AI technologies for neuromarketing is rising continuously in all industries (McKinsey, Citation2021). Thus, if marketing professionals do not consider the ethical risks of algorithms in consumer behavior, preferences, segmentation, and targeting (Zulaikha et al., Citation2020), they may damage the brand’s reputation or lead to a substantial monetary loss for its implementations. An example is the lawsuit against Alphabet Inc., amounting to 5 billion US dollars. Google is blamed for consumer profiling even in private mode (Reuters, 2020) and then again in incognito (Southern, Citation2021). Hence, since neither neuromarketing nor AI has matured in research and theoretical frameworks, both enjoy disbelief and unethical behavior from certain groups (Rakić, Citation2021; Petrillo et al., Citation2022). As they include algorithms capable of collecting and interpreting data to mimic cognitive decisions and predict future behavior, it is becoming imperative to determine which ethical aspects should be considered and regulated when combining neurotechnologies and neuromarketing.

This study seeks guidelines to assist market researchers, marketing professionals, data scientists, and developers in using neuromarketing and AI/ML algorithms ethically for consumer behavior and preferences, consumer segmentation, and buyer targeting while maintaining the benefits provided to consumers and businesses across industries. It also seeks to promote a more morally sound use of neuromarketing algorithms by offering viable solutions to address its challenges, enhancing understanding by raising awareness of the concerns in applying neuromarketing methods, and providing direction for future studies and innovations. The findings and recommendations can help practitioners, researchers, and stakeholders make better decisions about utilizing and implementing neuromarketing.

The researchers’ major difficulties and challenges were rooted in the complex ethical implications of using AI/ML algorithms in neuromarketing. One challenge was navigating the intricate balance between leveraging advanced neurotechnology for marketing effectiveness and ensuring consumer privacy and autonomy. The research sought to understand how these technologies could be applied ethically within the bounds of differing international data protection laws.

The research’s achievements included a comprehensive analysis that synthesized insights from a systematic literature review, expert surveys, and interviews. This multi-pronged approach allowed the researchers to craft nuanced policy recommendations to mitigate the ethical issues identified. Moreover, by comparing practices across the U.S. and Spain, the research made strides in understanding the global impact of neuroethics in neuromarketing, positioning its contributions at the forefront of the international discourse on AI ethics in consumer marketing.

2. Literature review

In the US, little is known regarding how consumers cope with privacy and data security risks, especially in the neuromarketing field. It is known that such algorithms have been finding their way into e-commerce, social media, the Internet of Things (IoT), and national security (Jin, Citation2018), as the threat associated with neuromarketing algorithms, privacy, and data security is fundamental. Primarily data-driven, such threats can directly or indirectly relate to AI/ML algorithms and other data technologies. For instance, as the expected value of data generated by neuromarketing algorithms is enhanced as it accumulates, companies are prompted to gather, collect, and store even more data, regardless of whether they train ML algorithms or use AI. In addition, another primary concern today is the need for internationally accepted principles regulating a responsible and ethical attitude to processing and using personal data for training systems with AI/ML algorithms that use these systems in the interests of business (Camilleri, Citation2023; Ozmen Garibay et al., Citation2023).

2.1. Privacy and data security in the US and the EU

The US has no overarching legislation on consumer privacy or data security. Currently, neuromarketing AI/ML algorithms’ consumer protection policies are a patchwork of local and federal regulations, with a few federal laws explicitly addressing privacy protection. They all tend to be industry-specific. For instance, the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act of 1998 (COPPA) regulates online services for children under 13. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPPA) supplies data privacy and security provisions for medical records. The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) regulates how financial institutions deal with personal data (Jin, Citation2018).

Privacy is subject to federal regulation by sectors. The Department of Health and Human Resources (DHHS) enforces HIPPA in health care. The Federal Communication Commission (FCC) regulates telecommunication services. The Federal Reserve System monitors the financial sector, while the Security and Exchange Commission (SEC) focuses on public firms and financial exchanges. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) deals with terrorism and cybercrimes related to national security. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) addresses privacy violations and inadequate data security as deceptive and unfair practices following the 1914 FTC Act. FTC’s privacy enforcement focuses on ‘notice and choice’, emphasizing how firms’ data practice deviates from the privacy notice they disclose to the public. This enforcement authority covers almost every industry and overlaps with many sector-specific regulators.

For sectors not subject to GLBA, HIPPA, or COPPA, no legislation mandates privacy notice, but many firms provide it voluntarily and seek consumer consent before purchase or consumption. Some industries also adopt self-regulatory programs to encourage certain privacy practices. For instance, the Digital Advertising Alliance (DAA), a non-profit organization led by advertising and marketing trade associations, establishes, and enforces privacy practices for digital advertising (Gehl, Citation2016). While privacy notice is something that consumers can access, read, and consent to, most data security practices are only visible once someone exposes the data vulnerability (via data breach or white-hat discovery). Accordingly, FTC enforcement on data security focuses on whether a firm has adequate data security, not whether the firm has provided sufficient information to consumers (Jin, Citation2018).

The EU has followed the ‘human rights’ approach, which curtails transfer and contracting rights often assumed under a ‘property rights’ approach. The EU recognized individual rights of data access, processing, rectification, and erasure in the new legislation. With its broad and transnational scope of application, the impact of GDPR, which entered into effect in May 2018, will also affect numerous companies outside the EU. Still, its effectiveness in protecting data privacy remains to be seen. However, two challenges are worth mentioning: First, for many data-intensive products (say self-driving cars), data do not exist until the user interacts with the product, often under third-party support (say GPS service and car insurance). Should the data belong to the user, the producer, or third parties? Second, even if property rights over data can be clearly defined, it does not imply perfect compliance. Both challenges could deter data-driven innovations if the innovator obtains the right to use data from multiple parties beforehand.

Data protection standards are becoming increasingly high, and companies face the more complex task of evaluating whether their data processing activities are legally compliant, especially internationally. Data can easily cross borders and play a vital role in the global digital economy. The processing of personal data occurs in various spheres of economic and social activity. The progress in information technology and digital business transformations makes processing and exchanging such data considerably easier (Voigt & Dem Bussche, Citation2017; Dąbrowska et al., Citation2022). In this context, the EU adopted the GDPR to harmonize further the rules for data protection within the EU Member States and raise privacy for the affected individuals.

2.2. Ethical concerns with neuromarketing strategies and applications

As consumer behavior has always been a marketer’s goal, the emergence of consumer neuroscience promising to shed light on consumers’ preferences and motivations, businesses have been increasingly attracted to this field. For over a decade, most of the discussion regarding neuromarketing applications and ethics concerns has concentrated on its commercial implementations as consumers fear that the data compiled can be utilized unethically (Hensel et al., Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Casado-Aranda & Sanchez-Fernandez, Citation2022; Tiutiu & Dabija, Citation2023). Consumer manipulation and the lack of transparency have been the primary concern, as big data and AI are reshaping consumer privacy and data security risks (Hensel et al., Citation2017a; Trettel et al., Citation2017; Wang, Citation2022). There is an increasing number of FDA-regulated AI/ML algorithms in the US but insufficient public information on validation datasets. These algorithms make it difficult to justify clinical applications since their generalizability and bias cannot be inferred (Ebrahimian et al., Citation2022).

2.2.1. Lack of transparency

Neuromarketing-based methodologies on relevant marketing stimuli lack transparency and reliability. Different companies offer services based on proprietary computational methods, algorithms, and approaches that are not entirely available to the scientific community or validated. This opacity in the methodologies employed by some companies and their results makes it difficult for researchers and scientists to separate supported and unsupported claims of validity of the services offered by those companies. Such ambiguity reflects common misconceptions toward public opinion and users of these methodologies regarding the effectiveness of these technologies (Trettel et al., Citation2017; Neuwirth, Citation2022).

Considering the perceptions and perspectives regarding these limitations, challenges, and potential solutions of neuromarketing implementations (Kaul, Citation2022; Alsharif et al., Citation2023b), a gap in the literature exists regarding the factors impeding the growth of neuromarketing, such as ethical and manipulation concerns, the high cost, the need for specialized expertise, lack of proper knowledge and understanding, the lack of financial resources, the lack of labs and facilities, and time requirements. Despite these obstacles, several scholars (Goncalves et al., Citation2022; Alsharif et al., Citation2023b) suggest potential solutions to enhance the application of neuromarketing, such as establishing collaborative solid networks, providing labs and facilities, increasing financial resources, complying with laws and regulations, and reducing tools and experiment costs.

The potential of neuromarketing can only be exploited effectively if trust in the field and industry rises, which correlates strongly with ethical conduct (Trettel et al., Citation2017; Wicinski, Citation2022). A significant downside of this opportunity is that, predominantly, several commercial studies confirm and need help with such ethical issues. Academics and business practitioners have hailed the development of a regulatory, ethical guideline in neuromarketing (Ulman et al., Citation2015; Briesemeister & Selmer, Citation2020). Most of the extant ethics codes are relatively too general, which can be helpful but does not elucidate specific essential issues for marketers (Hensel et al., Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Hula, Citation2022a). Consequently, Hensel et al. (Citation2016, Citation2017a, Citation2017b) developed an extended guideline known as the Ethical Guidelines in Neuromarketing (EGNM) as part of the Neuromarketing Science and Business Association (NMSBA) Code of Ethics, which supplies guidelines on steering neuromarketing research ethically.

2.2.1.1. Predicting consumer choice

The first commonly perceived potential ethical issue is the fear that neuromarketing may completely predict consumers’ choices. Similar criticisms regarding such prediction have been applied to traditional marketing research and practice but are perhaps most accentuated in neuromarketing (Hula, Citation2022b). Provocative research seems to herald the power of neuromarketing, as when fMRI has been used to predict individuals’ choices and purchase decisions (Schwarz, Citation2022; Kislov et al., Citation2023), like an EEG (Zhu et al., Citation2022), indicating that brain activity can foretell a consumer’s preference much better than self-reporting their preferences. Despite the narrowness of the assumptions drawn from these studies, all referring to data regarding brain predictors of preference in a single context, critics perceive such neuromarketing practices as a possible infringement of consumers’ rights to privacy (Penrod, Citation2022). It assumes that neuroscience techniques propose an outlet into consumers’ minds and extract data that consumers are unaware of, supplying a means to recognize consumers’ choices before making them.

Privacy concerns may arise for those accepting to participate in neuromarketing research, but these do not seem to be significant ethical hindrances for most (Saad, Citation2020; Penrod, Citation2022). This apprehension needs to be corroborated on numerous levels. First, most consumers do not have their brains scanned or provide hormone samples to investigators; that merely happens in the context of empirical research analyses (Verhulst et al., Citation2019). Thus, an individual consumer is not the explicit subject of a privacy infringement. Instead, findings are delineated based on inference to the general public from a small experimental population sample, as in existing marketing, biomedical, and behavioral research. Second, those who partake in scientific research are subject to an informed consent process in which they are apprised of the research’s goals and risks of participating in the experiment.

The general public occasionally interprets neuromarketing results as deterministic predictors of their behavior or preferences as prevenient from hard science. This perception may be exacerbated when results are exaggerated, as characteristic of many neuromarketing companies. Numerous scholars consider this view of consumers’ characterizations based on neuromarketing insights as belittling, dangerous, and immoral (Howard, Citation2020; Torbert, Citation2021; Mau et al., Citation2023). Another concern is that firms attempting to predict consumer choices will see and treat consumers as mere automata, or robots, without liberty to choose or dignity. The charge is that neuromarketers treat consumers as if they were only things to be used as mere means to the neuromarketers’ ends (Penrod, Citation2022; May, Citation2023).

Neuromarketing prognoses are probabilistic rather than deterministic, and firms engaged in such experiments need not claim that consumers’ preferences and behavior are entirely determined. Firms should recognize that consumers are at liberty to preclude whether to buy or not a product, regardless of their likes and dislikes or neurobias (Garofalo & Gallucci, Citation2021; Nguyen, Citation2021). Neuromarketing does not rely on the contemptible sentiment of consumers. Still, consumers can be predictable even if they are at liberty to choose (Suhler & Churchland, Citation2009; Liljevall & Lillskog, Citation2023). If consumers’ choices were predictable through traditional or neuromarketing investigation, they might be seen as sheer factors with relative value instead of individuals, undermining their dignity and respect.

Predicting consumer behavior and preferences significantly differs from compelling and manipulating consumers against their will. Such predictions must maintain the rationality and the dignity of the consumers’ preferences being predicted. Nevertheless, the neuromarketing domain is far from such a level of prediction. Even when neuromarketing companies anticipate consumers’ choices, they need not treat consumers as a means to an end. Instead, they can assist consumers in obtaining products or services with a more efficient rationale for why they want or need them (Keller, Citation2000; Taghikhah et al., Citation2021).

2.2.2. Influencing consumer choice

A commonly perceived potential ethical issue is the fear among consumers that neuromarketing can be used to go beyond prediction and influence consumer choice. Successful neuromarketing, it is argued, might rob consumers of control, and make the marketed goods irresistible (Garofalo & Gallucci, Citation2021; Närväinen, Citation2023). Of course, shaping consumers’ choices is the goal of marketing generally, but does neuromarketing offer firms a unique and novel ability to find a ‘buy button’ in the brain?

While neuroscience might help improve predictions of consumer choice, there is no current evidence of a ‘buy button’ in the brain. There are areas of the brain coded for value and reward (Clithero & Rangel, Citation2013; Garofalo & Gallucci, Citation2021; He et al., Citation2021), particularly the anticipation of reward (Ali et al., Citation2022). Things that are more rewarding or valued activate these areas more intensely, but this is not equivalent to a ‘buy button’. It should be noted that neuromarketing does not create the stimulus it tests (e.g. advertisement, promotional video, etc.), nor does it seek to make it unconscious. This discipline analyzes how the consumer responds to the stimulus to find out how it works, i.e. which areas are attended more or if it manages to excite, among other aspects (Halkiopoulos et al., Citation2022). Thus, neuromarketing provides no unique path—even in principle—for optimizing a marketing message to render consumers unable to control their actions; for example, neuromarketing could not create a menu description of an entrée that compels patrons to purchase that item any more than traditional marketing techniques could. In addition, even if it were plausible, targeting a person to define the optimal stimuli for their preferences would be impracticable (Martínez-López et al., Citation2020; Tirandazi et al., Citation2022).

Research has shown that supraliminal but unattended primes can significantly affect consumer behavior (Fitzsimons et al., Citation2002; Ferraro et al., Citation2009; Harmsel, Citation2021; Cheng et al., Citation2022). There is growing evidence that marketing information to which consumers are exposed can significantly affect their preferences, even when they were unaware that their choices and selections were being influenced or were exposed to brand information (Hayes et al., Citation2021; de Ridder et al., Citation2022; Goncalves et al., Citation2023). For example, a study by Goncalves et al. (Citation2023) manipulated the number of times consumers were exposed to photographs and videos of four leading road bicycles: Look, Specialized, Trek, and Pinarello. At the experiment’s end, consumers’ biosignals were analyzed to predict which brands consumers would prefer. The experiment analysis showed that consumers who participated in the experiment had different preferences depending on the age, gender, and aesthetics of each brand. While some consumers experienced surprise when exposed to a brand, others experienced disgust. Such an experiment clearly and causally demonstrated the power of marketing manipulation on consumers’ behavior that operates outside of conscious awareness. However, it could not predict consumers’ preferences, mainly due to neuro bias and the small population sample size (only nine subjects). However, it argued that consumers respond more favorably to a progressive combination of stimuli, from static posters and photos to videos, instead of only one type of stimuli. The study also showed that over-stimulation tends to lead to feelings of disgust.

While these studies demonstrate that behavioral research can elucidate strategies to influence consumers’ choices outside their awareness, they can also show that neuromarketing does not deserve any particular moral opprobrium and is certainly not the only way to influence consumers outside their conscious awareness (Carrington et al., Citation2010; Penrod, Citation2022; Reith, Citation2022). Critics might respond that all such unconscious influences—whether neuroscientific or not—are remote control. However, this reply conflates consciousness with control (Suhler & Churchland, Citation2009; Kalaganis et al., Citation2021), for example, as in the study by Goncalves et al. (Citation2023).

Such physiology-based marketing allows a better understanding of consumers’ decisions (Nanda et al., Citation2019; Mumtaz et al., Citation2021). Consumers decide freely, and neuromarketing tries to provide an answer to why they make specific choices by analyzing physiological factors that consumers cannot control, as well as their stated justifications (Bočková et al., Citation2021; Royo-Vela & Varga, Citation2022). This combination of data is relevant, given that consumers are unaware of all the factors that influence their choices. There is often a cognitive dissonance between the reasons they argue and the physiological responses triggered in their body. The current paradigm states that emotions are taken emotionally and justified a posteriori rationally (Mandolfo & Lamberti, Citation2021; Srinivasa, Citation2022; Seth & Mahato, Citation2023).

2.2.3. Brain and biometric data Overclaiming and manipulation

Some analysts argue that overclaiming, erroneous data sharing, and stealth marketing are significant causes for this industry’s lack of trust. Overclaiming is exaggerating brain and biometric data, which may emerge for the benefit of the company subsidizing the experiment where the outcomes are skewed in favor of their corporate objectives or adjusted based on a firm’s agenda (e.g. holding or maintaining consumers). Nonetheless, researchers (Thomas et al., Citation2017; Penrod, Citation2022a, Citation2022b) argued that overclaiming causes expectations to be inapplicable to what the research can reasonably deliver. In addition, falsely highlighted findings are often shared publicly to augment market share by employing anxiety or fear or the opposite, extremely optimistic (and inaccurate) data, which misleads the consumer into completing a purchase they otherwise would not have done. They argued that the ethical concern with the idea that neuromarketing is manipulative is that it arrests or overrides the consumer’s independence and autonomy. Even worse, stealth marketing, a marketing practice based on subtle persuasive cues provided by neuroscience insights, can potentially impact consumers below their conscious awareness (Mule, Citation2021; Penrod, Citation2022a, Citation2022b). Such practice is one of the top ethical concerns for the neuromarketing sector.

2.2.4. Protection of human subjects

Neuromarketing experiments demand human subjects, which can be challenging when the enrollment processes are ethical. There is a large and diverse number of potential human subjects, from individuals with disabilities, babies, and college students looking for some perks, all vulnerable and in an industry with almost no oversight or laws to protect them (Stanton et al., Citation2017; Thomas et al., Citation2017; Spence, Citation2020; Wicinski, Citation2022). Regarding consumer subjects, privacy is paramount (Belascu, Citation2020; McQuoid-Mason, Citation2022).

2.2.5. Reliability of results: Socioeconomic status and racism

Knowing that brain activity can be distinctively based on phenomenology, neuroscientists and neuromarketing scholars should be instructed to concentrate on a more diverse, multi-racial, human subjects experiment population sampling to achieve legitimate results, a rarely mentioned topic (Schibuk, Citation2022). Given that the typical participants in neuromarketing experiments are primarily from a white middle-class background, any insights drawn from these studies for global organizations targeting multicultural communities may be inadequate or misleading due to the limited racial diversity in the sample, as the subjects are drawn from societies that are Western, educated, industrialized, wealthy, and democratic. It is not appropriate to generalize the behavior of such individuals to the vast majority of humanity living under varying circumstances (Farah, Citation2017; Levrini & Jeffman dos Santos, Citation2021; Goncalves et al., Citation2022, Citation2023). Researchers incur the risk of reproducing scientific racism by omitting racial experiences that do not fit or are too tricky to understand in neurobiological calculations (Krieger, Citation2021; Rollins, Citation2021).

No human brain exists out of context; human brains are lived experiences that affect how they behave and how the body reacts (Greely, Citation2021; Nguyen et al., Citation2023). Because of this, neuromarketing investigators should assess how socioeconomic status (SES) and racism affect the brain and biometric activity (Agyeman et al., Citation2022; Goncalves et al., Citation2022). fMRI experiments have demonstrated that SES has an effect and encountered distinctions in how brain systems are engaged for executive functions that have not been observed in behavioral analyses (Farah, Citation2017; Merz et al., Citation2019; Saarikivi et al., Citation2023).

Using Diffusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging (dMRI), Assari and Boyce (Citation2021) showed that the impacts of SES indicators on cerebellum cortex microstructure and integrity are more fragile in black than white households. Such result aligns with Marginalization-related Diminished Returns (MDRs), defined as diminished effects in the SES index for blacks, minority groups, and other races compared to whites (Assari & Boyce, Citation2021). Other researchers (Masten et al., Citation2011; Atlas, Citation2021; Hamler et al., Citation2022) found that in reaction to being socially excluded by whites, black subjects seemed more distressed, significantly demonstrating more social pain-related neural activity and diminished emotion regulatory neural activity.

In addition to the lack of representation in lab population sampling, biometric analysis and secondary tools should be revisited for their effectiveness in testing multiracial diverse subjects; one such tool is AI/ML, often used as a secondary neuromarketing tool. Researchers use AI/ML algorithms to collect and analyze data from other neuro tool sources, enabling a more in-depth and reliable understanding of consumer behavior and preferences (Hawkins, Citation2022; Kliestik et al., Citation2022; Srivastava & Bag, Citation2023). However, some challenges are the proliferation of groupthink, insularity, and arrogance in the AI community, to name a few (Metz, 2021; Bedoya, Citation2022; Goncalves et al., Citation2022). AI/ML algorithms have not yet learned to recognize the differences and peculiarities among black faces because the images used to train it mainly had been of white faces, and neuromarketing researchers may not be accounting for this disparity (UN News Global Perspective Human Stories, Citation2020; Tippins et al., Citation2021).

2.3. Ethical concerns with ML algorithms in consumer behavior and preferences

One reason for introducing ML algorithms in neuromarketing is the increasing global market competition. Marketers seek a path to satisfy consumer needs while also delivering better service. However, understanding consumers’ demands requires greater spending. According to recent studies, almost half of the global corporations have already invested in developing ML algorithms, while nearly a quarter of them are in the learning stage and hope to integrate them into their business platforms accordingly (Lee & Shin, Citation2020; Hayes et al., Citation2021; Jaiswal et al., Citation2022). Hence, a significant strength of ML is its ability to manage a massive amount of unstructured data, such as text, video, and images (Adnan & Akbar, Citation2019; Ma & Sun, Citation2020; Velkova, Citation2023), very quickly and efficiently, saving time and money for marketers when analyzing thousands of consumer data segments.

These corporations investing and deploying ML algorithms benefit from comprehensive data analysis to align consumers’ needs and demands with market decisions (Adnan & Akbar, Citation2019; Velkova, Citation2023). Marketers best respond to consumer demands through segmentation (Velkova, Citation2023). As consumers are grouped and profiled, algorithms reduce the need for consumer analysis and observations (Velkova, Citation2023) by learning and making such information readily available to marketers. Another advantage of neuromarketing and ML algorithms is their predictive capabilities, as once an algorithm has recognized patterns in trained data, it can quickly forecast consumer product or service preferences (Ma & Sun, Citation2020; Velkova, Citation2023). ML algorithms can anticipate human behavior by modeling an extensive array of variables, matching products/services, and clients’ demands (Kotras, Citation2020). After segmenting a consumer base, targeting is the next step in the marketing strategy, requiring a thinking and more complex algorithm (Huang & Rust, Citation2022; Velkova, Citation2023), as the process requires features such as judgment, knowledge, decision-making skills, and, thus, more complex algorithms. Recommendation engines or predictive modeling are often adopted in these targeting processes (Liu & Chen, Citation2019; Huang & Rust, Citation2022).

Broadly, the focus surrounding AI/ML algorithm ethics has been on the opacity of how these algorithms reach decisions. No one knows how an algorithm makes a specific decision and why. While an algorithm makes decisions on a chess game or checkers, no one cares (Loi et al., Citation2021; Shin et al., Citation2022). However, when an ML algorithm decides whether a consumer obtains a loan or not or is racially or socioeconomically discriminated against, several ethical issues arise. Consumers deserve and potentially are entitled to an explanation of how decisions to accept or decline a loan were reached since such digitally automated decisions may harm the consumer whose loan has been declined. The same is true when a consumer is discriminated against. While not physical, such harms can significantly impact consumers’ lives, credit scores, and socioeconomic status due to an algorithm’s decision.

2.4. Principles of ethics

Whether neuromarketing algorithms are ethical or not, and whether these algorithms’ decision outputs concerning consumers are moral, correct, or wrong, such applications may be harmonized and able to be performed by comprehending the various viewpoints of ethics. The principles of ethics are split into four branches: meta, applied, descriptive, and normative. Meta-ethics is concerned with developing a broad understanding of ethics (Allan, Citation2015; Seif-Farshad et al., Citation2021; Poulsen & Christensen, Citation2023). Normative ethics focuses on developing ethical standards and responsible behavior (Copp, Citation2005; Laczniak & Murphy, Citation2019; Remišová et al., Citation2019; Liu et al., Citation2020). Applied ethics concentrates on pragmatic quandaries or controversial issues (Leese et al., Citation2019; Bang et al., Citation2022; Mason, Citation2023). Descriptive ethics concentrates on people’s behavior and moral standards (Hämäläinen, Citation2016; Laczniak & Murphy, Citation2019; Forbes et al., Citation2020; Jiang et al., Citation2021a, Citation2021b).

This study leans on the theories of normative ethics to assess which actions are ethical while responding to the research questions. The three broad types of normative ethics are consequentialism/utilitarianism, virtue ethics, and deontology (Harsanyi, Citation1977; Portmore, Citation2020; Ranganathan, Citation2022). Although within the same branch, each imbues distinct values and beliefs. Utilitarianism, similar to consequentialism, shares various tenets. While consequentialism does not specify any desired outcome, utilitarianism defines good as the outcome (Rachels & Rachels, Citation2012; Scheyer, Citation2019; Gesang, Citation2021; Andersen, Citation2022): an action is ethical if the overall benefits outweigh the widespread harm (Rogerson et al., Citation2017; Sætra, Citation2020). Deontology undervalues the outcome and questions the act’s morality instead. Nevertheless, virtue ethics drives the individual toward achieving the ultimate goal while maintaining high standards of excellence (Scheyer, Citation2019; Gal et al., Citation2020; Gesang, Citation2021; Penrod, Citation2022a) and practicing good traits such as compassion, respect, and generosity.

Several scholars have investigated the ethical risks of AI/ML algorithms (Stanton et al., Citation2017; Hensel et al., Citation2017b; Kritikos, Citation2018; Magalhães, Citation2018; Susser, Citation2019; Sample et al., Citation2020; Sætra, Citation2020; Attié et al., Citation2021; Sidorenko at al., Citation2021; Tsamados et al., Citation2021), but the emphasis has not explicitly been on those in neuromarketing (Clark, Citation2020). As a result, the literature on ethical issues of such algorithms and how they emerge in the neuromarketing industry is addressed in this study.

3. Objectives and research questions

The literature cited in this study is more about privacy and data security than neuromarketing AI/ML algorithms due to the scarcity of more specific data. The extant literature lacks explicit guidance on how neuromarketing AI/ML algorithms can continue to operate effectively and ethically. For this purpose, two regions were studied and compared: the US, for its lack of an ethical consumer protection guideline such as EU’s GDPR, and Spain, due to the close collaboration of research on the theme by three of the authors, and to assess how the EU’s GDPR impacted countries in the EU, such as Spain, in the protection of consumers’ privacy. Another goal was to draw a comparison between the two countries, one subject to GDPR and the other absent from any country-wide comprehensive guideline, intending to identify challenges in ethical frameworks and opportunities compared to the lack of similar regulations in the US. This research attempts to answer how neuromarketing algorithms can create and retain value within the ethical boundaries of consumer behavior and preferences, segmentation, and targeting.

3.1. Theoretical framework and conceptualization

Although many ethical theories exist, each with differing points of view, this study adopts rule utilitarianism as a framework for analysis. Its premise is that an act must maximize the overall good for society and adhere to specific regulations (Bowen, Citation2020). In this research context, a utilitarian framework can be operationalized by evaluating the consequences of neuromarketing practices powered by AI/ML algorithms in terms of overall benefit or harm to society. Descriptively, this framework would assess existing neuromarketing strategies to determine how they align with maximizing consumer welfare and protecting privacy. Normatively or prescriptively, it would guide the creation of policies and practices prioritizing actions yielding the greatest aggregate utility. Neuromarketing strategies should increase business profits and enhance consumer satisfaction and trust without infringing privacy rights. The utilitarian approach advocates for neuromarketing strategies that support the common good by being transparent, non-manipulative, and respectful of consumer autonomy and data protection norms.

When rule utilitarianism is applied to neuromarketing algorithms in Europe, the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU sets the limits, protecting universal values based on law and democracy (De Gregorio, Citation2018; Ivanova, Citation2021). In such a case, rule utilitarianism classifies these algorithms as unethical if they ignore human rights or if the benefits they deliver to individuals do not exceed the risks. Nonetheless, connecting distinct modes of profiling with Foucauldian thought on governing, pattern-based categorizations in data-driven profiling, safeguards such as the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU or its data-protection framework lose their applicability to a diminishing role of the tools of the anti-discrimination framework (Van Den Meerssche, Citation2022).

Some consumer protection laws and regulations apply to neuromarketing algorithms in the US. For instance, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) enforces consumer protection laws and regulations prohibiting unfair or deceptive marketing practices, including some guidelines for using neuromarketing techniques (Savage, Citation2019; Alarcon & Ha, Citation2020; Galli, Citation2022). The FTC has also brought enforcement actions against companies that have used deceptive or unfair neuromarketing techniques (Wexler & Thibault, Citation2019; Bakir, Citation2020). Some examples include brainwave analysis and biometric data collection in advertising and marketing. Additionally, some states have consumer protection laws that apply to neuromarketing algorithms. For instance, California has a data privacy law, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), which gives consumers the right to know what personal information is being collected about them and opt out of selling their personal information (Baik, Citation2020; Mulgund et al., Citation2021). Nevertheless, no comprehensive federal law currently regulates neuromarketing algorithms in the US, allowing for gaps in consumer protections, particularly concerning emerging AI/ML algorithms, augmented and virtual reality, and other neuro technologies that existing laws and regulations may not cover (Luna-Nevarez, Citation2021; Kalkova et al., Citation2023).

Against this backdrop, this study endeavors to conduct a systemic review of the field of neurostrategy to scrutinize the isolated and fragmented attempts of conjoining neuromarketing and neuroethics in the extant literature and fill various gaps that are currently limiting the field, such as lack of (a) a formal research agenda; (b) knowledge about the concepts at the confluence of neuromarketing and neuroethics; and (c) clarity about what is ‘hot’ and what is ‘not’ in the field (Cristofaro et al., Citation2022). The following questions drove this study phase before conducting semi-structured interviews: a. What are the dominant concepts at the junction of neuromarketing and neuroethics? b. What are the broader links between these concepts? c. How has the scholarly discourse around neuroethics evolved? d. Which trends are gaining traction within neuroethics research? e. What propositions can be developed to advance empirical assessment in neuroethics related to AI/ML algorithms? A thematic (conceptual) and semantic (relational) analysis of the literature was conducted to attempt to answer these questions.

Investigating neuroethics through advanced bibliometric methods allows for a more robust, systematic, and comprehensive literature review (Kaur, Citation2023). Hence, this study contributes to the literature by laying down solid foundations of neuroethics based on machine-based identification of the core concepts and their relationships. Moreover, it offers a bibliometric mapping of the AI/ML-related neuromarketing and neuroethics research themes from 2019 through 2023, revealing the trends and bridging the gaps in this relatively novel field of scholarship.

4. Methodology

In addition to a survey and semi-structured interviews with expert academics and business practitioners from the field, both scientometric analysis and systematic literature review techniques have also been employed to analyze the literature thoroughly.

4.1. Study design

To provide further insight into the ethical issues concerning the combination of neuromarketing and AI, the design of this study is qualitative exploratory. Data collection methods were based on critical literature reviews, a survey, and semi-structured interviews with subject matter experts from the US and Spain to bridge academic and industry perspectives regarding the overarching question. The answers provided by these two groups were analyzed to understand best and compare the level of awareness of each group related to neuroethics, consumer privacy protection and legislation, and more internalized ethical guidelines adopted when considering neuromarketing initiatives and respective use of AI/ML algorithms. The findings from the literature review were adapted from similar research methods in this field (Xiao & Watson, Citation2019; Jöhnk et al., Citation2021), built upon during the interviews, fostering a critical thinking process and providing a comprehensive understanding of the status quo.

4.2. Participants

Several scholars (Coper Joseph, Citation2014; Adams, Citation2015; Galvin, Citation2015; Vogel et al., Citation2019; Gill, Citation2020) argue that an adequate number of interviews for qualitative research should range between five and 20, depending on its scope. Considering such ranges, using a random snowball sample selection approach, the authors invited several business and academic experts via LinkedIn or through professional connections at universities and corporations using or proficient in neuromarketing algorithms to answer the online survey and indicate if they would be willing to be interviewed. Few of those who answered the survey were willing to be interviewed. We ended up with 14 interviewees who were not gender-matched: Seven experts in the US and seven in Spain. They all had diverse backgrounds and years of experience in neuromarketing (see ). They were interviewed to maximize the diversity of opinions and find similarities and differences among them (Yin, Citation2014; Alamri, Citation2019). None of them had collaborated in the creation of an ethical code in neuromarketing.

Table 1. List of participants’ profile.

lists all participant’s profiles. Regarding the US interviewees, a total of seven interviews were carried out. The sample was not gender-matched (30% male, 70% female) aged 25 to 54 years (M = 36 years, SD = 9 years), 42% had a Ph.D., and 85% had more than five years of experience in the field. For Spaniard interviewees, a total of seven interviews were carried out. However, at the end of the session, one interviewee requested that the data be erased, which was promptly granted. The sample was also not gender-matched (33% male, 67% female) in an age range of 40 to 63 years (M = 51 years, SD = 11 years), 67% had a Ph.D., and 83% had more than five years of experience in the field.

4.3. Ethical aspects

Semi-structured interviews were conducted via Zoom in the interviews’ native language, English and Castilian, respectively, to create an atmosphere of trust and tranquility in which they felt free to express their opinions on such a sensitive subject as ethics and neuroethics (Jehn & Jonsen, Citation2010; Islam & Aldaihani, Citation2022). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and their permission was sought for a voice recording of the session.

4.4. Data collection and analysis

The semi-structured interviews were conducted in May and June 2023 across Spain and the US, delivered in Castilian and English, correspondingly, through Zoom or Microsoft Teams. Each session lasted between 45-60 minutes. Participants were selected using purposive snowball sampling to ensure a diverse representation of the study’s target demographic, with ethical consent obtained digitally before the interviews. Digital recordings were meticulously transcribed and, where necessary, translated into English, followed by a retranslation to Castilian for cross-verification of translation accuracy. NVivo, a qualitative data analysis software, was used to identify themes, ensuring analytical rigor. Measures such as member checking and triangulation were incorporated to ensure reliability and validity. The researcher’s influence was minimized through reflexive practices, and all data were handled with strict adherence to confidentiality and data protection protocols. Follow-up interactions were scheduled as needed to clarify participant responses and deepen the understanding of emergent themes.

4.4.1. Methodical literature review and scientometric analysis

To minimize subjectivity and arbitrariness in the current systematic analysis and review, this study followed the guidelines and principles outlined by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement and checklist (Radua, Citation2021). The bibliometric mapping was conducted using VOSViewer, which was selected over R-tools and the like for the bibliometric analysis primarily due to its user-friendly interface and specialized capabilities tailored for bibliometric data. Unlike other tools, such as R, which requires data analysis and visualization programming skills, VOSViewer provides a more accessible platform, especially for less-skilled coding users. Its advanced visualization features allow for the creation of high-quality, interpretable bibliometric maps, simplifying the complex data interpretation process. VOSViewer’s design is optimized for handling bibliometric data sources like Web of Science and Scopus, enabling efficient data importation and network creation. Additionally, the support community for VOSViewer is dedicated to bibliometrics, offering focused assistance and updates that are particularly beneficial for this research field.

4.4.1.1. Eligibility criteria

The journal articles, theses, dissertations, editorials, reviews, books, book chapters, proceeding papers, and scientific texts that somehow address neuromarketing, neuroethics, and the application of AI/ML algorithms to neuromarketing formed the initial criteria for eligibility for this review. Along with published articles, early access articles in Web of Science’s business or management category were part of the studies under consideration. Moreover, the eligibility criteria included scientific texts written in English. Furthermore, studies published (or available as early review) at the confluence of neuromarketing and neuroethics were part of this review.

4.4.1.2. Information source

In conducting bibliometric analysis, including diverse document types such as full-text articles, reviews, editorials, proceedings, abstracts, technical papers, and chronologies is imperative for a comprehensive synthesis of academic discourse and scientific advancement. Full-text articles provide the core substance of research findings; reviews offer synthesized knowledge and identify trends; editorials present insights and scholarly opinions that reflect the field’s dynamics; proceedings capture the cutting-edge research presented in conferences; abstracts allow for rapid appraisal of research scope; technical papers present detailed technical findings; and chronologies map the historical progression and milestones in a discipline (Aria & Cuccurullo, Citation2017). This multifaceted approach enables a robust understanding of the research landscape, scholarly communication patterns, and the evolution of thought within a field, thereby supporting the identification of seminal works and emerging trends critical for academic and practical applications. As this research scope enwrapped fast-changing and ever-evolving technology updates, only resources from January 1, 2019, through May 31, 2023, were reviewed, including scientific papers, web-based articles, and secondary statistical data.

The Clarivate Analytics Web of Science Core Collection database was used to extract the most valuable and high-impact research data from other existing databases (such as Scopus, EBSCO, and Google Scholar). Web of Science database was specifically chosen for this study for five reasons: (1) It is the most updated database for bibliometric studies, which includes most of the papers published as well as recently accepted by reputable journals (Kaur, Citation2023; Rialti et al., Citation2019); (2) It covers wide variety of publication formats such as full-text articles, reviews, editorials, proceedings (journals and book-based), abstracts, technical papers, and chronologies. SCOPUS covers a wide range of document types; however, chronologies, timelines of historical events, or developments in a particular subject area are not standard document types cataloged in SCOPUS, as they focus on scientific documents and their bibliographic information rather than on providing historical timelines like a chronology (Kaur, Citation2023); (3) It includes more than 90 million records in comparison to 69 million records on Scopus (Moral-Muñoz et al., Citation2020); (4) It has broader temporal coverage than that of Scopus (Kaur, Citation2023); and (5) It provides consistent results for the same query used with similar search parameters over time (Kaur, Citation2023; Marzi et al., Citation2020). Thus, Web of Science is particularly suitable for this study as it provides the most updated, accurate, efficient, and reliable database with the broadest temporal coverage for performing a robust analysis of machine-readable scientometric data (Wilden et al., Citation2019).

Moreover, the choice of the database is consistent with prior bibliometric studies in business management research, such as Kaur (Citation2023), Marzi et al. (Citation2020), Rialti et al. (Citation2019), and Wilden et al. (Citation2019). In addition, Kaggle, Mordor Intelligence (Mordor Intelligence, Citation2021), and Statista were utilized to access secondary quantitative data, such as the adoption rates of AI/ML techniques in the neuromarketing field and public opinion survey results for data privacy concerns. Furthermore, this research relied on online blogs, reports, and articles to aggregate more detailed illustrated data about the algorithms’ application in neuromarketing and their inherently hidden ethical risks. The online papers help derive insights about the companies that have adopted automated targeting and personalization and recent scandals in the media arising from the data collection and analysis with neuromarketing’s ML algorithms. Language limitations have meant that the list of companies and media is far from exhaustive, but this article aims to contribute to a more extensive research process.

4.4.1.3. Search strategy

Following the best practices suggested in the literature to select a search query (Kaur, Citation2023), an in-depth analysis of the abstracts, author’s keywords, and literature reviews of published research articles at the junction of neuromarketing and neuroethics for AI/ML driven applications were conducted to assist in the identification of concepts that are being used in the scholarly discussion. After several iterations to define a broad research query, the following query was selected and implemented to capture the essence of neurostrategy effectively:

Written in English; keywords, title, and summary in English. These criteria were chosen to link the study objective to the research area, with a series of exclusion criteria applied to the latter. The inclusion criteria considered the following search queries:

‘neuromarket* algorithms AND marketing’, ‘artificial intelligence OR machine learning AND ethics’, ‘artificial intelligence OR machine learning AND neuromark*’, ‘personalized market* AND consumer privacy’, ‘ethical issues AND neuromark* algorithms’, ‘ethical AI’, ‘GDPR and neuromarket*’, ‘GDPR and AI’, ‘ethical theories and neuromarket* algorithms’, and ‘neuroethics and algorithms’.

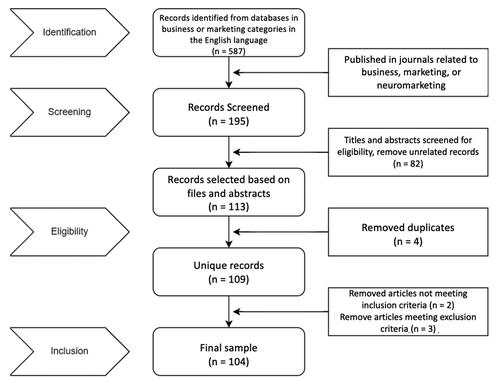

4.4.1.4. Selection process

The above search query returned 587 results, with the language (English) and categories (business and marketing) filters in place. To refine these results, only the studies published in business, marketing, or neuromarketing journals were filtered out for further analysis. This selection process resulted in an initial sample of 195 studies. After that, a revision of the title and abstracts of these articles was conducted to determine the relevance of each article to the scholarly discourse about neuromarketing and neuroethics related to AI/ML algorithms applications. This manual review process weeded out 82 articles that were completely unrelated to the field (e.g. results for the search term market* leading to topics covering traditional marketing strategies, 4 P-7P strategies, robots, ML application strategy; or search for term neuroethics resulting into hits that involved studies on neurology studies; or search for the term neural* yielding results on studies dedicated to AI/ML neural networks). This process resulted in 113 studies that were considered for further screening. In the next step, four duplicate records were removed, which resulted in 109 unique studies. These studies were then analyzed in-depth based on the full text, and the following inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to them:

Inclusion Criterion: The articles focused on the application of neuromarketing concepts, knowledge, or methods to investigate the application of AI/ML algorithms or neuroethics ramifications of such algorithms on consumer privacy, GDPR, consumer segmentation, selection and/or its outcomes, such as competitive advantage or enhanced neuromarketing strategies.

Exclusion Criterion: The exclusion criteria used to select the documents were research articles, review articles, letters to the editor, conference summaries, and lectures. No geographical restrictions were applied as studies from different continents relating to the variables and research areas found in the SCOPUS and Web of Science databases was considered in the review. Also excluded were studies focusing on the utilization of neuromarketing and neuroethics in other niche branches of management, such as NeuroIS, NeuroFinance, neurostrategy, neuro decision-making, etc., which were intentionally not included in the sample to dedicate this study.

After applying these inclusion and exclusion criteria to the initially identified data set of 109 studies, two did not meet the inclusion criterion and, thus, were not considered for further analysis. On the other hand, three studies were excluded based on the exclusion criterion. Furthermore, the reference lists of all articles retrieved from the search were subjected to manual review to identify additional studies that may fit the objectives of this study, but no additional relevant articles were identified. Hence, the final data set comprised 104 focal articles (86 journal articles, six book chapters, seven proceeding papers, three editorial materials, and two reviews), comparable to the sample size of similar studies in the field (Ascher et al., Citation2018). A flowchart depiction of this process is shown in .

4.4.2. Online survey

An online survey was set up in Qualtrics, containing 25 questions. Seven covered sociodemographic data, and four assessed the respondent’s perceived relationship between neuromarketing and AI/ML. Six evaluated the respondents’ general knowledge of ethical codes related to the discipline/industry, and seven assessed the ethical risks of AI/ML algorithms perceived at universities and the business environment. The last question asked respondents about their interest in being interviewed and, if so, their contact information.

Since this study relied on the EU’s GDPR as a consumer privacy guideline and aimed to compare best practices in the ethical use of AI/ML algorithms for neuromarketing in the US and the EU, data were collected in Spain and the US. The population selection criteria comprised Spaniards and American academic experts or business professionals in the digital and neuromarketing discipline/industry, directly or indirectly involved with AI/ML algorithms as developers or users (e.g. engaged with digital or neuromarketing, advertising), with at least three years of related experience and a member of a higher education institution or a company involved in the development or use of AI/ML algorithms for digital or neuromarketing applications. A total of 735 email invitations to complete the online survey were sent. These were gathered from prospects sourced from LinkedIn and the researchers’ connections with academic research institutions and business experts in the US and Spain. Then, a snowball approach was adopted by asking respondents to forward the survey link to other prospects they knew and met the survey criteria. The snowball sampling technique was chosen over other approaches, such as purposeful sampling, due to its effectiveness in reaching a specialized population that is difficult to access. This research delves into the niche intersection of neuromarketing, neuroethics, and AI/ML algorithms, so identifying subjects with the requisite expertise and experience was challenging. Snowball sampling allowed for utilizing the networks of initial participants to identify subsequent subjects, thereby capitalizing on the interconnectedness of professionals in this specialized field. This approach broadens the reach within a targeted community by leveraging personal connections. It increases the likelihood of including participants with the deep, nuanced knowledge necessary to contribute valuable insights to the study.

4.4.3. Semi-Structured interviews

The interviewees were selected based on their field of expertise, professional experience, and research activity. The selection criteria included expertise in neuromarketing algorithms or ML expertise, marketing, digital marketing, and ethics. The diverse respondents being interviewed were crucial in thoroughly answering the research questions, including researchers in these fields, corporate marketing representatives, data scientists, AI/ML professionals, ethics, and marketing professionals,

Since this study was conducted when the COVID-19 pandemic was still lingering, protecting the health and safety of respondents and researchers was among the top priorities. The interviews were conducted via Zoom. First, the interviewees were contacted via email. Then, a research prospectus, an invitation to the interview, an informed consent form, and a list of the main questions to be asked during the interview were provided. The respondents’ identity and confidentiality were protected by generating a code for each of them, but their current occupation/position and primary demographic data can be found in . The interviews were transcribed and anonymized. The interview transcripts were coded and analyzed using NVivo, which has robust tools to facilitate the systematic coding and analysis of semi-structured interviews, allowing the organization, categorization, and retrieval of text efficiently.

5. Research findings

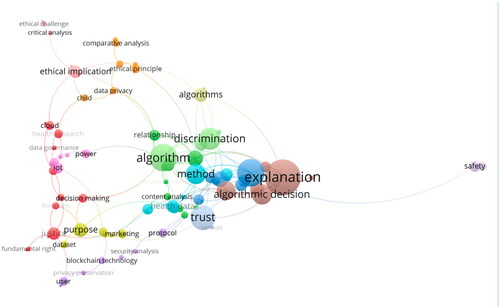

The following are the results of various bibliometric analyses undertaken to unveil the field’s conceptual structure. Semantic relatedness (e.g. the frequency and proximity with which the concepts co-occur in the text) has been studied, and various maps of meaning have been generated to systematically answer this study’s research questions based on a few bibliometric indicators.

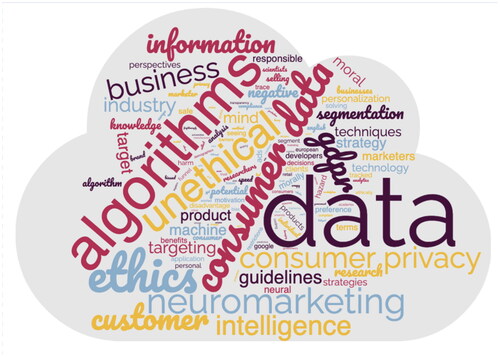

5.1. Dominant concepts at the junction of neuromarketing and neuroethics

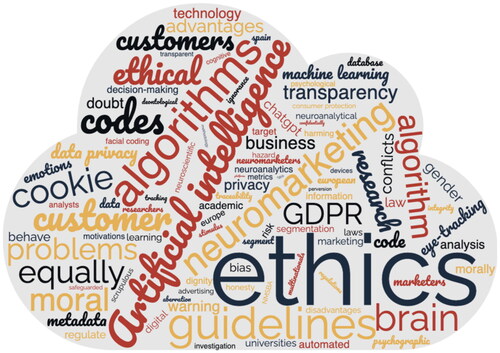

and are word clouds extracted from the interview transcripts of the US and Spain interviewees. They underline the main themes in the minds of the interviewees when asked about their understanding and opinions about neuromarketing’s AI/ML algorithms’ applications at the junction of neuroethics. For American interviewees, the word ‘data’, followed by ‘algorithms’ and ‘consumer data’, were the highlights in the word cloud as it has the highest co-occurrence index in the sample. Nonetheless, the perimeter of the word cloud reveals the amplitude of other vital topics. It can be expected, therefore, that in the quest to develop a more ethical approach to neuromarketing AI/ML algorithms, awareness of what may be considered ‘unethical’, ‘consumer privacy’, ‘ethics’, and many other factors is warranted.

Figure 2. US Sample Word cloud: Data, followed by algorithms and consumer data, were the main themes with the highest co-occurrence index in the sample.

Figure 3. Spain Sample Word cloud: Ethics, followed by a concern with artificial intelligence, algorithms, guidelines, and neuromarketing, were the main themes with the highest co-occurrence index in the sample.

For the Spanish word cloud, the word ‘ethics’, not data as with the American sample, takes center stage, followed by a concern with ‘artificial intelligence’, ‘algorithms’, ‘guidelines’, and ‘neuromarketing’.

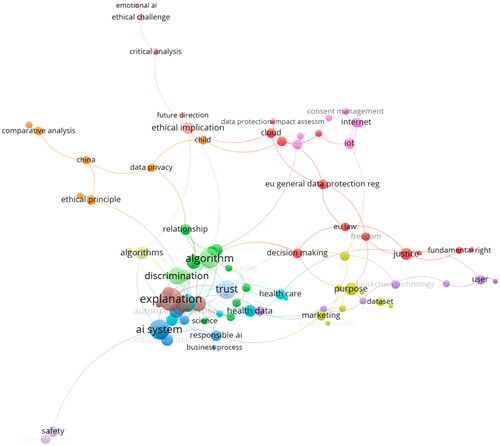

and are the result of a co-word analysis performed using VosViewer as an analytical tool to understand the conceptual structure of the field. Accordingly, the results are interpreted on the comparative positions of words and their dispersion along the dimensions, i.e. closer words are more similar in distribution. The co-word analysis depicted in , showing the association of strength of these major themes, suggests that the foundational concepts at the junction of neuromarketing AI/ML algorithms and ethics can be distinguished into nine different networks of concepts, listed in order of magnitude:

Figure 5. Neuromarketing and Neuroethics Bibliometric Analysis - Fractionalization of total link strength.

Network 1 focuses on constructs attempting to explain algorithm decisions and safety implications.

Network 2 is focused on trust, content analysis, data, marketing applications, and its purposes.

Network 3 emphasizes the vital interest of researchers in the issues related to algorithms, discrimination, relationships, and content analysis, among secondary interest in data and health applications.

Network 4 underlines researchers’ interest in neuromarketing and neuroethics, especially in neuromarketing methods, applications, protocols, and other minor interest themes such as content analysis and data management.

Network 5 highlights insights from related topics such as AI/ML algorithms, the purpose of such algorithms, marketing, and datasets.

Network 6 focuses on ethical implications, challenges, data governance, GDPR, the cloud, decision-making, freedom, and power.

Network 7 underscores consumer justice, focusing on fundamental rights, freedom, decision-making, data governance, and datasets. This network also includes analyzing the role of various significant factors it intersects, such as trust, risk, algorithms, methods, implicit knowledge, and gestures, in individual decision-making.

Network 8 is less significant than the first four networks. However, it concentrates on the more technological aspects of neuromarketing and AI/ML algorithms, including blockchain technology, privacy preservation, user/consumer privacy protection, protocols, and security analysis.

Network 9 embodies subtopics related to comparative analysis, ethical principles, data privacy, and children’s exposure to such technologies, with several interlinks to algorithms, trust, and ethical implications networks.

Another bibliometric angle of analysis, a thematic map analyzed through a fractionalization of total link strength, the total strength of the co-authorship links of a given researcher with other researchers, is shown in . It reveals additional critical neuromarketing, AI/ML algorithms, and neuroethics themes. This map reveals various research themes’ centrality (importance) and density (development). As shown, AI systems, responsible AI, emotional AI, business processes, data protection impact assessment, consent management, and automation represent important themes being researched. Hence, scholars in the field must continue to work towards further developing these themes, given their importance for foundational as well as future research in the field of neuromarketing’s use of AI/ML algorithms and neuroethics.

The bibliometric analysis also shows a thematic evolution of topics over recent years, demonstrating how the research in the field has evolved. It shows that even though the research on understanding AI/ML algorithms application in neuromarketing has been growing fast, the scholarly focus on neuroethics, including broad ethical considerations of such applications, possibly prompted by regulations, such as the EU’s GDPR and the new US’s CPRA, which became effective in January 2023. Moreover, increased interest can also be seen in interlinked topics such as neurotech (e.g. EEG, MEG, fMRI, GSR, eye-tracking, pupilometry, face coding, AI/ML algorithms, emotional AI, etc.), neuromanagement, IoT, cloud technologies, blockchain. Nevertheless, since consumer decision-making is a significant theme, scholars are encouraged to continue researching this field.

5.2. Online survey results

The survey dataset records responses from 60 digital and neuromarketing professionals from the US and Spain. The respondents’ gender distribution indicates that 40% (24) identified as male, while 56.67% identified as female. Additionally, 3.33% preferred not to disclose their gender. Regarding nationality, 12% were from the US, 27% were from Spain, and 3% chose the ‘Others’ category, while 58% did not specify their countries directly.

The survey aimed to gather insights into the participants’ opinions and awareness regarding the ethical dimensions of AI/ML and neuromarketing. Participants were asked for opinions regarding specific statements related to the research topic and select their level of agreement on a Likert scale ranging from 1-5, where 5 indicates strong agreement:

Neuromarketing and artificial intelligence are complementary and should not be used separately. – Out of 57 participants, 46% agreed, 11% strongly agreed, and 28% disagreed.

Neuromarketing benefits from artificial intelligence. – Of 57 responses, 60% agreed, 23% strongly agreed, and 9% disagreed.

Using machine learning algorithms for consumer/consumer preferences segmentation and targeting has many benefits. – Out of 57 responses, 82% agreed or strongly agreed, while 12% disagreed or strongly disagreed.

Participants were asked to select statements on which they agreed. The top five most selected statements, with each receiving more than 30 responses, included:

I understand how AI can be used in neuromarketing.

There are some disadvantages to using machine learning algorithms for consumer preference segmentation and targeting.

I understand how neuromarketing specifically benefits from AI.

The use of AI should have limits when applied to neuromarketing.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are there to help the corporate operations and marketing teams have a wide neuromarketing scope to convey massive value to AI’s potential data.

For the second part of the survey regarding ethical considerations, participants were asked to select Yes or No to the following questions:

Are you aware of any codes of conduct or other written agreements for ensuring ethical businesses, or are the employees, for example, trained to behave morally? – Of 54 responses, 54% replied yes, 33% no, and the remaining were unsure.

Are you aware of current guidelines data scientists use to limit moral hazard to individuals? – Out of 54 responses, 61% replied no, 28% yes, and the remaining were unsure.