Abstract

This study aims to examine the effect of application costs, trust reciprocity, and self-efficacy on discouraged borrowers and the role of gender as a moderating variable. Our sample was 356 micro, small, and medium enterprise actors in the manufacturing industry in Central Java Province, Indonesia. The data was analyzed using the covariant-based structural equation modeling method. The results demonstrated that application costs, trust reciprocity, and self-efficacy significantly affect discouraged borrowers. However, the contextual role of gender is not fully proven because it can only weaken the self-efficacy effect of discouraged borrowers. This study enriches the literature by proposing discouraged borrowers from a demand factor perspective. In addition, it also offers policy suggestions for the banking industry to collaborate intensively with other stakeholders to increase banking digital literacy and build capacity to foster mutual trust and self-efficacy among micro, small, and medium enterprise actors.

IMPACT statement

The problem of lack of access to bank credit faced by micro, small, and medium enterprises is not only related to the problem of being unable to meet bank credit needs but also due to the willingness of MSMEs themselves to choose not to apply for credit from banks because of the concern that their application will be declined or what is commonly known as discouraged borrowers. This issue must be addressed to help micro, small, and medium enterprise actors mitigate their financing obstacles through better access to bank credit. Therefore, this study aims to analyze the factors that cause micro, small, and medium enterprises to become discouraged borrowers. This study will offer several policy actions to banks and related stakeholders regarding application fees, the development of e-banking features, and banking literacy to encourage micro, small, and medium enterprises to utilize banking financing.

Reviewing editor:

1. Introduction

Micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSME) actors greatly contribute to economic growth (Verma et al., Citation2020). For example, in developing countries like Indonesia, in 2022, the number of MSMEs reached 99% of the total business units, absorbed 96.9% of the workforce, and contributed to the gross domestic product of 60.5% (Kompas, Citation2023). However, MSME actors in Indonesia still often experience limited access to bank credit (Hutahayan, Citation2019; The Organisation for Economic Co-operation & Development, Citation2022; Wulandari et al., Citation2017) so they face the problem of a lack of financing. The Indonesian government has made efforts to make policies to minimize credit interest for MSMEs (Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs, Citation2022) but has kept the amount of MSME bank loans the same. Meanwhile, around 75% of MSMEs prefer to meet their capital needs from moneylenders (Cable News Network Indonesia, Citation2023). MSMEs must bear very high-interest rates, which often causes MSMEs to work only to pay their debts to moneylenders (Chakraborty & Mahanta, Citation2023).

The lack of access to bank financing for MSMEs is not only related to the problem of inability to meet bank credit requirements but also the choice factor of MSMEs themselves. It is possible that MSMEs have the adequate capacity to have bank credit, but their owners intend to do something other than apply for bank credit (Mardika et al., Citation2018; McCarthy et al., Citation2017). One of the reasons is the concern that their application will be declined or what is commonly known as discouraged borrowers. This phenomenon is common in countries like the United States of America, Eastern Europe, and several Central Asian countries (Gama et al., Citation2017). This issue must be addressed to help MSME actors mitigate their financing obstacles through better access to bank credits. Thus, it is important to comprehensively analyze the determinants of discouraged borrowers (Khan et al., Citation2021).

Several previous studies (Comeig et al., Citation2015; Fernández-Méndez & González, Citation2019; Menkhoff et al., Citation2012) have investigated what causes discouraged borrowers from the supply side, banks tend to incur information asymmetry and find it difficult to evaluate MSME actors’ creditworthiness. Based on the work of Kon and Storey (Citation2003), information asymmetry encourages banks to increase credit interest rates, demand complicated credit requirements, and require higher collaterals. Consequently, MSME actors incur higher credit rates, complicated credit requirements, and higher collaterals when applying for credits. Meanwhile, other research has investigated the demand side and found the cause related to location factors (Gama et al., Citation2017). Longer distances between banks and MSME actors increase application costs (Xiang & Worthington, Citation2015). Consequently, MSME actors consider their application costs higher regarding time spent traveling to the banks and filling in the application forms (Yazdanfar & Öhman, Citation2020).

Besides application costs, prior studies also indicate trust determines discouraged borrowers (Hirsch et al., Citation2018; Howorth & Moro, Citation2012; Moro & Fink, Citation2013). Transaction-based lending and relationship-based lending are the two factors that might help define the interaction between MSME players and banks. Transaction-based lending refers to formal relationships between MSME actors and banks, including their business feasibility, financial reporting quality and interest rates (Gray & Premti, Citation2021). Meanwhile, informal relationships, sometimes emotionally developed, are more frequently used in relationship-based lending, as evidenced by MSME actors’ trust in banks (De la Torre et al., Citation2010). Tang et al. (Citation2016) demonstrated that higher trust reduces discouraged borrowers. However, their study only analyzes MSME actors’ trust in banks, while bank credits are related to mutual trust between banks and MSME actors. Thus, a two-way trust or trust reciprocity between these entities is crucial. Trust reciprocity motivates MSME actors to trust in banks and consider banks to trust in their ability to meet credit requirements and repayment obligations. Accordingly, this study investigates the effect of application costs and trust reciprocity as a determinant of discouraged borrowers.

Dare et al. (Citation2022) documented that self-efficacy motivates individuals to apply for bank credits. This finding can be further interpreted that MSME actors with high self-efficacy tend not to be discouraged borrowers. Self-efficacy refers to the extent to which an individual believes in his or her capacity to execute behaviors necessary to produce specific performance attainments (Bandura, Citation1997). If it is related to the context of the choice of financing sources, MSMEs who are confident in their capacity to manage their business, pay installments and interest on loans regularly have the potential not to avoid bank credit as a source of financing (Farrell et al., Citation2016). MSME actors tend to exhibit greater self-efficacy and acquire more resources like investor financing, equipment, and sponsorship (Maitlo et al., Citation2020). Hence, this study will also include self-efficacy as one of the factors expected to influence discouraged borrowers.

Gender also warrants further analysis because it likely weakens the effect of the determinants on discouraged borrowers. Several prior studies have discovered that banks tend to discriminate against female MSME actors because female entrepreneurs are riskier (Aristei & Gallo, Citation2022; Berguiga & Adair, Citation2021). Besides, females deal with more complicated credit requirements (De Andrés et al., Citation2021; Malmström & Wincent, Citation2018), making females less willing to take risky bank credits. Hence, gender can weaken the effects of application costs, trust reciprocity, and self-efficacy on discouraged borrowers, and this study uses gender as the moderating variable.

This study attempted to investigate the effect of application costs, trust reciprocity, and self-efficacy on discouraged borrowers among MSME actors in Indonesia and the role of gender as a moderating variable. The contribution of this study to the existing literature is to provide a better understanding of discouraged borrowers in at least two aspects. First, prior studies on discouraged borrowers have empirically demonstrated the determinants of discouraged borrowers in various countries, like India (Chakravarty & Xiang, Citation2013), China (Tang et al., Citation2016), Europe (Cowling et al., Citation2016) and Tanzania (Naegels et al., Citation2021). However, similar studies in Asian countries like Indonesia are still limited. Second, we included trust reciprocity and self-efficacy as the independent variables and gender as the contextual factor in our model, while these variables have not been explained before. Meanwhile, a practical contribution is to offer policy recommendations to reduce discouraged borrowers in MSME actors so that they will choose bank credit as an alternative source of financing to develop their business.

2. Literature review and hypothesis development

2.1. Theory of discouraged borrower

This study uses the framework of the theory of discouraged borrowers introduced by Kon and Storey, (Citation2003) to investigate what drives MSMEs to become discouraged borrowers. They use an institutional approach, extends the standard static adverse selection model of credit markets by integrating imperfect screening factors by banks and application cost borne by borrowers. In conditions of information asymmetry between banks and borrowers, banks are increasingly stringent in screening to avoid screening errors by rejecting ‘good’ borrower applications or approving ‘bad’ borrower applications. The quality of the screening carried out by the bank has discouraged MSMEs from applying for bank loans. In other words, discouraged borrowers arise because of the self-rationing mechanism of MSME actors who believe their credit will be rejected, so they are reluctant to apply for credit. In fact, the reluctance of MSME actors to apply for credit not only limits sources of financing but can also cause investment activities to become less than optimal, impacting business performance (Freel et al., Citation2012). In addition, discouraged borrowers are related to the scale of application costs. MSMEs can be discouraged from applying for bank loans when they bear higher application cost.

The theory of discouraged borrowers also posits the role of interest rate disparities charged by banks and money lenders. The smaller the difference, the greater the discouragement, so MSMEs are less likely to apply for a bank loan. Conversely, the greater the potential for MSMEs to seek alternative financing outside the banking sector. In summary, the theory of discouraged borrowers emphasizes economic perspectives, such as the application of costs and interest rates, to explain MSME’s discouragement decision, and it is still open to development by incorporating other perspectives. This study includes psychological factors such as trust, reciprocity, and self-efficacy. In addition, it also involves individual characteristics, especially gender, as a contextual factor, which moderates the effects of economic and psychological factors.

2.2. Application costs and discouraged borrowers

The theory of discouraged borrowers explains that information asymmetry in the banking industry makes it difficult for banks to identify MSME actors’ creditworthiness. Consequently, banks tend to increase interest rates and set complicated requirements to mitigate credit default risks (Le & Nguyen, Citation2019). Meanwhile, potential MSME actors will compare the costs of credit applications with their business profits. Kon and Storey (Citation2003) explained that application costs MSME actors’ sacrifices to apply for bank credits, consisting of time devoted to going to the banks, time devoted to complete credit requirements, costs to prepare reliable financial statements, and costs due to sharing their business information to external parties.

The theory of discouraged borrowers also argued that MSME actors who incur higher application costs are less comfortable in applying for credits (Kon & Storey, Citation2003) and consequently less motivated to rely on bank credits as their financing sources. Prior empirical results also revealed that higher application costs increase discouraged borrowers (Gama et al., Citation2017). Accordingly, the following is the testable hypothesis:

H1:

Application costs positively affect discouraged borrowers

2.3. Trust reciprocity and discouraged borrowers

Trust should be reciprocal (Freel et al., Citation2012). While banks must trust in MSME actors, MSME actors must also trust in banks. Hence, this study focuses on trust reciprocity instead of one-sided trust. Trust from banks to borrowers can help compensate for information asymmetry and behavioral uncertainty in credit repayments (Moro & Fink, Citation2013). Banks that trust MSME actors borrowers tend to reduce their application costs (Hagendorff et al., Citation2023).

Conversely, MSMEs must also have confidence that banks believe in MSMEs (Martínez-Tur et al., Citation2020). MSME actors with greater trust in banks are more willing to apply for bank credits. However, they may have several psychological obstacles, like fear of rejected applications, higher interest rates, collaterals, and complicated credit procedures (Currall & Judge, Citation1995; Das & Teng, Citation1998). Thus, the trust reciprocity of MSME actors will likely reduce the fear that bank credit applications will be rejected, which will encourage MSMEs to apply for bank loans. Furthermore, the hypothesis formulation can be proposed as follows:

H2:

Trust reciprocity negatively affects discouraged borrowers

2.4. Self-efficacy and discouraged borrowers

MSME actors’ self-efficacy refers to individuals’ self-confidence to effectively manage and develop their businesses. Various obstacles like the fear of rejection, higher interest rates and collateral, and complicated credit procedures cause discouraged borrowers. Higher self-efficacy ensures that MSME actors can repay their credits. Consequently, they are more confident applying for credits (Cole & Sokolyk, Citation2016; Kon & Storey, Citation2003). Individuals with lower self-efficacy worry that they will be unable to develop their businesses.

Conversely, those with higher self-efficacy consider themselves capable of developing their businesses. Individuals with higher self-efficacy develop more positive feelings toward money and are arguably more willing to make decisions (Farrell et al., Citation2016), including applying for credits. Consequently, the following is the testable hypothesis:

H3:

Self-efficacy negatively affects discouraged borrowers

2.5. Gender as a moderator

Females and males exhibit different risk preferences (Alonso-Almeida & Bremser, Citation2015; Ammer & Ahmad-Zaluki, Citation2017). Female entrepreneurs are arguably less willing to take risks (Buratti et al., Citation2017). MSME actors unwilling to take risks tend to rely on more safe financing (Ginesti et al., Citation2018). Hence, the gender of MSME actors is also closely associated with their decisions to apply for bank credits. However, there are still pros and cons related to gender bias in applying for bank loans. Several studies have shown that female-managed MSMEs submit fewer credit applications than their male counterparts (Galli et al., Citation2020; Moro et al., Citation2017; Ongena & Popov, Citation2016), but Arcuri et al. (Citation2024) study shows that a lower application rate by female-led MSMEs is not proven. In fact, Hewa-Wellalage et al. (Citation2021) provide evidence that MSMEs managed by females are higher in submitting credit applications than those managed by males.

In Indonesia, most people adhere to a patriarchal culture, leading to the dominance of men as decision-makers. Even though MSMEs are managed by a wife, business strategic decisions, including finance, are still in the hands of the husband (Richard et al., Citation2013; Shohel et al., Citation2021). Thus, MSMEs led by females are likely reluctant to apply for bank credits because they still need the approval of their husbands.

Taking into account risk preferences and patriarchal culture, female entrepreneurs are predicted to strengthen the positive impact of application costs on discouraged borrowers. Gender is also contextual in the relationship between trust reciprocity and discouraged borrowers. The presence of female entrepreneurs can weaken the negative impacts of trust reciprocity and self-efficacy on discouraged borrowers. Hence, the following are the testable hypotheses:

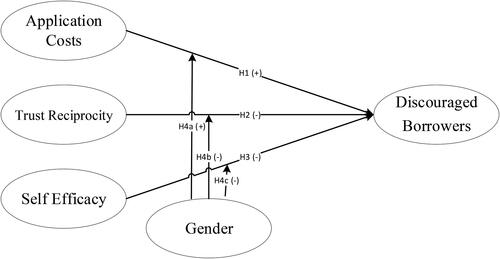

H4a:

Female entrepreneurs Gender tends to strengthen the positive effect of application costs on discouraged borrowers.

H4b:

Female entrepreneurs Gender tends to weaken the negative effect of trust reciprocity on discouraged borrowers

H4c:

Female entrepreneurs Gender tends to weaken the negative effect of self-efficacy on discouraged borrowers

The path of the relationship between the dependent, independent, and moderating variables in this study is visualized in . The application cost is expected to have a positive effect on discouraged borrowers. Meanwhile, trust, reciprocity, and self-efficacy have a negative effect. Furthermore, the presence of female entrepreneurs is predicted to strengthen the positive effect on application costs and weaken the negative effect of trust reciprocity and self-efficacy on discouraged borrowers.

3. Research method

Our research population was MSME actors in the manufacturing industry in Central Java Province, Indonesia. Currently, the manufacturing industry has the largest contribution to the Indonesian economy. Meanwhile, the location selection was based on the consideration that Central Java is widely known to have many MSME centers. Data regarding the existence of each MSME actor who was the target of respondents was obtained from the Central Java Cooperative Office and survey results in the field. The sample selection used the purposive sampling method with the following criteria:

MSME actors who sought external finance three years ago but have yet to request bank credits.

MSMEs have been established for up to eight years.

The MSME owners were still at the core of all business decisions.

Data collection was carried out through a field survey method involving six enumerators. During the 14 days of the survey, 356 respondents were obtained, who were then used as the sample for this study. This sample size exceeded the minimum sample size of −100, as Hair et al. (Citation2019) suggested. If using Structural Equation Modeling analysis and the model contains five or fewer variables, each variable has more than three indicators with high item commonality.

depicts the respondents’ characteristics generated by the field survey.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of respondents’ characteristics.

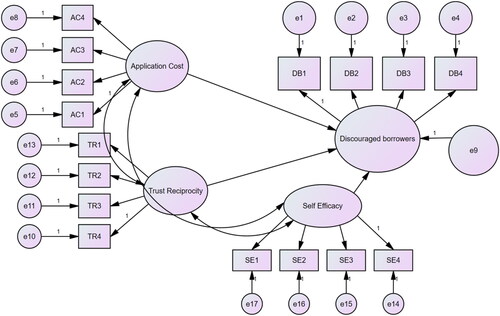

We measured the discouraged borrowers variable by using several indicators: not applying for credits out of fear of denied applications, too high interest rates, higher collaterals, and too complicated credit procedures. The indicators were adopted from Chakravarty and Xiang (Citation2013). The application cost (AC) variable was adopted by Kon and Storey (Citation2003) definition, which included costs incurred to complete credit requirements, time spent to fill in the forms, time spent to meet bank officers, and inconvenience in revealing business information. Next, the operationalization of the trust reciprocity (TR) variable encompassed MSME actors’ confidence that banks trust in their ability to provide collaterals, repay the credits, increase their business growth, and generate profits. The indicators were adapted from (Fehr & Gächter, Citation2000). The self-efficacy (SE) variable refers to individuals’ belief in completing tasks and responsibilities (Themanson & Rosen, Citation2015) and was measured with the indicators of the ability to generate consumers, promote products, manage finance, and produce high-quality products. The indicators were adopted from (Chen et al., Citation1998). The results of all variables above were measured using the 5-point Likert scale. Meanwhile, as the moderating variable, the gender variable (G) was measured with a dummy variable that equals one if the respondent is female and zero otherwise.

Data were analyzed using covariance-based structural equation modeling because it is more suitable for model testing, which is oriented to confirming a theory, in this case, discouraged borrower’s theory. This technique combines confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and multiple regression. In addition, this technique can analyze both observed and unobserved variables (Hair et al., Citation2019). Following Merhi et al. (Citation2021), we analyzed the moderating role of the gender variable by comparing the results of the female and male subsamples. Gender strengthens the effects of the independent variables on the dependent variable when the results in the male subsample are insignificant, and the results are significant for the female subsample. Conversely, gender weakens the impact of the independent variable on the dependent variable when the results are significant for the male subsample and not for the female subsample. However, gender cannot moderate when the results are insignificant for both subsamples.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Results

The convergent validity test was carried out to identify the validity of the indicators in measuring variables. In contrast, the reliability test using Cronbach’s alpha identified the consistency of the indicators in measuring the latent variables. In covariance-based structural equation modeling, the factor loading values ≥0.70 and Cronbach alpha ≥0.70 are acceptable (Hair et al., Citation2019). and present the results of the validity and reliability tests, suggesting that all indicators met the criteria because their values are ≥ 0.70.

Table 2. Validity and reliability test.

The results of the model fit test indicate the Chi-square of 313.329, a probability value of 0.176, GFI of 0.950, AGFI of 0.930, RMSEA of 0.010, and TLI of 0.997. demonstrates the complete results, implying that the model fits.

Table 3. Goodness of fit test.

indicates the results of the causality test. H1 indicates that application costs positively and significantly affect discouraged borrowers (ß = 1.056; p-value = 0.000). Next, H2 demonstrates that trust reciprocity significantly and negatively affects discouraged borrowers (ß = −0.105; p-value = 0.026). Lastly, H3 implies that self-efficacy negatively and significantly affects discouraged borrowers (ß= −0.145; p-value = 0.013). Thus, all hypotheses predicting the direct effects of application costs, trust reciprocity, and self-efficacy on discouraged borrowers are empirically supported.

Table 4. Causality test results.

Hypotheses 4a, 4b, and 4c emphasize the moderating role of gender in the effects of application costs, trust reciprocity, and self-efficacy on discouraged borrowers. indicates that for hypothesis 4a, there is no difference between males and females (p-value = 0.000). Meanwhile, for 4b, female MSME actors strengthen the relationship between trust reciprocity and discouraged borrowers. Lastly, for hypothesis 4c, gender weakens the impact of self-efficacy on discouraged borrowers. In sum, female entrepreneurs do not weaken the impacts of application costs and trust reciprocity on discouraged borrowers, while female entrepreneurs weaken the relationship between self-efficacy and discouraged borrowers.

Table 5. Results of the moderation test—by gender.

4.2. Discussions

The results demonstrate that application costs significantly and positively affect discouraged borrowers. In other words, higher application costs discourage MSME actors from applying for bank credits. Kon and Storey (Citation2003) suggest that application costs consist of costs incurred to complete credit requirements, time spent meeting bank officers, time filling out the forms, and inconvenience in revealing business information. Application costs require MSME actors to devote their money and time and become more accountable in producing business information. Understandably, application costs discourage MSME actors from applying for bank credits.

Conversely, banks use application costs as a self-rationing mechanism. Due to higher application costs, unbankable MSME actors are arguably unwilling to apply for bank credits (Han et al., Citation2009a, Citation2009b). However, the self-rationing mechanism is potentially harmful if initiated excessively because bankable MSME actors will be less willing to apply for credits due to higher application costs. Our findings supported Gama et al. (Citation2017) and Han et al. (Citation2009a, Citation2009b), who documented that application costs significantly and positively affect discouraged borrowers.

Our analysis revealed that trust reciprocity significantly and negatively affects discouraged borrowers. Higher trust reciprocity between MSME actors and banks motivates MSME actors to apply for bank credits. While application costs are arguably more transaction-based lending (more reliant on formal information), trust reciprocity is more relationship-based (more reliant on information from banks’ relationship with MSME actors). Despite higher application costs, MSME actors with higher trust reciprocity with their banks remain motivated to apply for bank credits (Moro & Fink, Citation2013). Trust reciprocity also helps banks mitigate discouraged borrowers. Our results supported Freel et al. (Citation2012), who observed that trust reciprocity significantly and negatively affects discouraged borrowers.

Self-efficacy significantly and negatively affects discouraged borrowers. Higher self-efficacy motivates MSME actors to have better business management skills and be more self-confident in applying for bank credits. They may not be disappointed if the bank rejects their application because they understand that closer cooperation with the bank is essential to grow their business. MSMEs realize the importance of sources of bank financing to generate short-term profits and develop their businesses. They do so by taking risks, making decisions during uncertainty, and being proactive in business opportunities (Savickas et al., Citation2009).

Contextually, gender only moderates self-efficacy. Female entrepreneurs considered more risk-averse (Lohse & Qari, Citation2014; Montford & Goldsmith, Citation2016; Moudrý & Thaichon, Citation2020) weaken the effect of self-efficacy on discouraged borrowers. Although having higher self-efficacy, female MSME actors are less willing to apply for bank credits than their male counterparts. This result also reinforces the view about the role of patriarchal culture in Indonesia, which places the husband as the financial decision-maker even though his wife handles daily business operations. The banking system in Indonesia also requires that applications for bank loans must be approved by the husband, so it does not allow female MSME managers to apply for bank loans independently.

Nevertheless, MSMEs frequently face internal financing problems to support their businesses (Breunig & Majeed, Citation2020). This study failed to demonstrate that gender moderates the impacts of application cost and trust reciprocity on discouraged borrowers. Both female and male MSME actors are equally reluctant to apply for bank credits when application costs increase. In a similar vein, both female and male MSME actors with higher trust reciprocity with their banks are equally more willing to cooperate with their banks to acquire financing sources.

5. Conclusions and implications

5.1. Conclusion

This study seeks to test the effects of application costs, trust reciprocity, and self-efficacy on discouraged borrowers and the role of gender in moderating those relationships. Six hypotheses can be developed based on the literature review results. Using 356 MSME actors in the manufacturing industry in Indonesia, the results demonstrated evidence supporting four hypotheses. The study revealed that application costs positively affect discouraged borrowers. Meanwhile, trust, reciprocity, and self-efficacy negatively affect discouraged borrowers. Further, gender only moderates the impact of self-efficacy on discouraged borrowers. In particular, female entrepreneurs significantly weaken the effect of self-efficacy on discouraged borrowers.

5.2. Theoretical implications

Our results contributed to the academic literature by supporting similar studies in various countries such as Central Asia and Eastern Europe, Australia, and Sweden, indicating that application costs are related, among other things, to time devoted to going to the banks and completing credit requirements as well as costs to prepare financial statements determine discouraged borrowers. Besides, we offer a more comprehensive discouraged borrowers model by highlighting that discouraged borrowers are not only affected by economic factors as postulated by the theory of discouraged behavior but also by psychological factors such as trust, reciprocity, and self-efficacy. To minimize discouraged borrowers, banks must trust in MSME actors, and MSME actors must also trust in banks. In addition, MSME actors need to have the confidence to be able to repay their credits. Unfortunately, gender has not been able to fully act as a contextual factor because it has only been proven to weaken the self-efficiency effect on discouraged borrowers.

5.3. Policy and managerial implications

This study also proposes several policy and managerial actions, among other things, that banks should aim to lower application costs, which have been one of the reasons preventing MSME actors from applying for bank loans. For example, bank officers proactively visit bankable MSMEs to offer credit and help fill out the required forms so that MSME entrepreneurs can save time applying for credit because they do not have to leave their jobs. The banking industry should continue to strive to develop e-banking features that will enable MSMEs to apply for banking loans online for a particular credit amount, reducing application costs. Besides, banks need to simplify credit requirements without sacrificing the prudential principle. In addition, the banking industry should collaborate intensively with other stakeholders, especially universities and local governments, to increase banking digital literacy and build capacity to foster mutual trust and self-efficacy among MSME actors.

5.4. Limitations and directions for future research

This study is inseparable from limitations, including not paying attention to the size effect. There is a strong possibility that the determinant effect of discouraged borrowers differs between micro and small to medium-scale businesses. Therefore, future research is expected to conduct discouraged borrowers studies based on business size to obtain better generalizations. In addition, this study has not considered aspects of risk preferences and behavioral biases such as the status quo. There is concern among MSME players that they will not be able to pay credit installments, and feelings of being satisfied with current business progress could be the cause of discouraged borrowers. Therefore, future research is expected to conduct discouraged borrowers studies based on business size, reference risk, and behavioral bias to obtain a complete discouraged borrowers determinant model and better generalization.

Author contributions

The authors contributed equally to the design and implementation of the research, the analysis of the results, and the manuscript’s writing. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Dhoni Rizky Widya Mardika

Dhoni Rizky Widya Mardika, a Doctoral Researcher at the Department of Management, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Kristen Satya Wacana, Indonesia. His research interests include financial management and personal finance. He published several articles in reputable international and national journals.

Theresia Woro Damayanti

Theresia Woro Damayanti is a Professor in Accounting at Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Kristen Satya Wacana, Indonesia. Her research interests include taxation and tax system evaluation. She was the author and co-author of several articles in reputable international journals.

Maria Rio Rita

Maria Rio Rita is an Associate Professor at Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Kristen Satya Wacana, Indonesia. Her research interests include entrepreneurship finance and personal finance. She has published a number of good-quality research.

Supramono Supramono

Supramono is a Professor in Finance at Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Kristen Satya Wacana. His research interests include behavioral finance and corporate finance. He published several articles in reputable international journals.

References

- Alonso-Almeida, M. D. M., & Bremser, K. (2015). Does gender specific decision making exist? EuroMed Journal of Business, 10(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1108/EMJB-02-2014-0008

- Ammer, M. A., & Ahmad-Zaluki, N. A. (2017). The role of the gender diversity of audit committees in modelling the quality of management earnings forecasts of initial public offers in Malaysia. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 32(6), 420–440. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-09-2016-0157

- Arcuri, M. C., Di Tommaso, C., & Pisani, R. (2024). Does gender matter in financing SMEs in green industry? Research in International Business and Finance, 69(June 2023), 102222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2024.102222

- Aristei, D., & Gallo, M. (2022). Are female-led firms disadvantaged in accessing bank credit? Evidence from transition economies. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 17(6), 1484–1521. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-03-2020-0286

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman & Company.

- Berguiga, I., & Adair, P. (2021). Funding female entrepreneurs in North Africa: Self-selection vs discrimination? MSMEs, the informal sector and the microfinance industry. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 13(4), 394–419. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-10-2020-0171

- Breunig, R., & Majeed, O. (2020). Inequality, poverty and economic growth. International Economics, 161, 83–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inteco.2019.11.005

- Buratti, A., Cesaroni, F. M., & Sentuti, A. (2017). Does gender matter in strategies adopted to face the economic crisis? A comparison between men and women entrepreneurs. In Entrepreneurship-Development Tendencies and Empirical Approach. Intechopen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.70292

- Cable News Network Indonesia. (2023). BRI Bertekad Bebaskan 45 Juta Pelaku UMKM dari Jerat Rentenir. https://www.cnnindonesia.com/ekonomi/20230228153345-78-918911/bri-bertekad-bebaskan-45-juta-pelaku-umkm-dari-jerat-rentenir.

- Chakraborty, P., & Mahanta, A. (2023). Asymmetric information, capacity constraint and segmentation in credit markets. Indian Growth and Development Review, 16(2), 158–192. https://doi.org/10.1108/IGDR-03-2022-0042

- Chakravarty, S., & Xiang, M. (2013). The international evidence on discouraged small businesses. Journal of Empirical Finance, 20(1), 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jempfin.2012.09.001

- Chen, C. C., Greene, P. G., & Crick, A. (1998). Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? Journal of Business Venturing, 13(4), 295–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(97)00029-3

- Cole, R., & Sokolyk, T. (2016). Who needs credit and who gets credit? Evidence from the surveys of small business finances. Journal of Financial Stability, 24(March 2014), 40–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2016.04.002

- Comeig, I., Fernández-Blanco, M. O., & Ramírez, F. (2015). Information acquisition in SME’s relationship lending and the cost of loans. Journal of Business Research, 68(7), 1650–1652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.02.012

- Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs. (2022). The government supports the empowerment of MSMEs through Increasing the portion of MSME loans to contribute greater to the national Economy. https://www.ekon.go.id/publikasi/detail/4651/perkuat-daya-saing-umkm-pemerintah-dorong-implementasi-kebijakan-pembiayaan-melalui-kredit-usaha-rakyat

- Cowling, M., Liu, W., Minniti, M., & Zhang, N. (2016). UK credit and discouragement during the GFC. Small Business Economics, 47(4), 1049–1074. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9745-6

- Currall, S. C., & Judge, T. A. (1995). Measuring trust between organizational boundary role persons. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 64(2), 151–170. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1995.1097

- Dare, S. E., Van Dijk, W. W., Van Dijk, E., Van Dillen, L. F., Gallucci, M., & Simonse, O. (2022). How executive functioning and financial self-efficacy predict subjective financial well-being via positive financial behaviors. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 44(2), 232–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-022-09845-0

- Das, T. K., & Teng, B. S. (1998). Between trust and control: Developing confidence in partner cooperation in alliances. The Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 491–512. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1998.926623

- De Andrés, P., Gimeno, R., & de Cabo, R. M. (2021). The gender gap in bank credit access. Journal of Corporate Finance, 71, 101782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2020.101782

- De la Torre, A., Martínez Pería, M. S., & Schmukler, S. L. (2010). Bank involvement with SMEs: Beyond relationship lending. Journal of Banking & Finance, 34(9), 2280–2293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2010.02.014

- Farrell, L., Fry, T. R. L., & Risse, L. (2016). The significance of financial self-efficacy in explaining women’s personal finance behaviour. Journal of Economic Psychology, 54, 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2015.07.001

- Fehr, E., & Gächter, S. (2000). Fairness and retaliation: The economics of reciprocity. Advances in Behavioral Economics, 14(3), 510–532. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.229149

- Fernández-Méndez, C., & González, V. M. (2019). Bank ownership, lending relationships and capital structure: Evidence from Spain. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 22(2), 137–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brq.2018.05.002

- Freel, M., Carter, S., Tagg, S., & Mason, C. (2012). The latent demand for bank debt: Characterizing “discouraged borrowers. Small Business Economics, 38(4), 399–418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-010-9283-6

- Galli, E., Mascia, D. V., & Rossi, S. (2020). Bank lending constraints for women-led SMEs: Self-restraint or lender bias? European Financial Management, 26(4), 1147–1188. https://doi.org/10.1111/eufm.12255

- Gama, A. P. M., Duarte, F. D., & Esperança, J. P. (2017). Why discouraged borrowers exist? An empirical (re)examination from less developed countries. Emerging Markets Review, 33(3), 19–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2017.08.003

- Ginesti, G., Drago, C., Macchioni, R., & Sannino, G. (2018). Female board participation and annual report readability in firms with boardroom connections. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 33(4), 296–314. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-07-2017-0079

- Gray, S., & Premti, A. (2021). Transaction-based lending and accrual quality. Managerial Finance, 47(1), 36–58. https://doi.org/10.1108/MF-01-2019-0012

- Hagendorff, J., Lim, S., & Nguyen, D. D. (2023). Lender trust and bank loan contracts. Management Science, 69(3), 1758–1779. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2022.4371

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., Black, W. C., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate Data Analysis. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119409137.ch4

- Han, L., Fraser, S., & Storey, D. J. (2009a). Are good or bad borrowers discouraged from applying for loans? Evidence from US small business credit markets. Journal of Banking & Finance, 33(2), 415–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2008.08.014

- Han, L., Fraser, S., & Storey, D. J. (2009b). The role of collateral in entrepreneurial finance. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 36(3–4), 424–455. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5957.2009.02132.x

- Hewa-Wellalage, N., Boubaker, S., Hunjra, A. I., & Verhoeven, P. (2021). The gender gap in access to finance: Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Finance Research Letters, 46(A), 102329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2021.102329

- Hirsch, B., Nitzl, C., & Schoen, M. (2018). Interorganizational trust and agency costs in credit relationships between savings banks and SMEs. Journal of Banking & Finance, 97(5), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2018.09.017

- Howorth, C., & Moro, A. (2012). Trustworthiness and interest rates: An empirical study of Italian SMEs. Small Business Economics, 39(1), 161–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-010-9285-4

- Hutahayan, B. (2019). Factors affecting the performance of Indonesian special food SMEs in entrepreneurial orientation in East Java. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 13(2), 231–246. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-09-2018-0053

- Khan, S. U., Khan, N. U., & Ullah, A. (2021). The ex-ante effect of law and judicial efficiency on borrower discouragement: An international evidence. Asia-Pacific Journal of Financial Studies, 50(2), 176–209. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajfs.12334

- Kompas. (2023). Crowdfunding Schemes in the Capital Market Can Be an Alternative for MSME Capital. https://www.kompas.id/baca/english/2023/07/16/en-skema-urun-dana-di-pasar-modal-bisa-jadi-alternatif-permodalan-umkm

- Kon, Y., & Storey, D. (2003). A theory of discouraged borrowers. Small Business Economics, 21(1), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024447603600

- Le, C. H., & Nguyen, H. L. (2019). Collateral quality and loan default risk: The case of Vietnam. Comparative Economic Studies, 61(1), 103–118. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41294-018-0072-6

- Lohse, T., & Qari, S. (2014). Gender differences in deception behaviour—The role of the counterpart. Applied Economics Letters, 21(10), 702–705. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2013.848020

- Maitlo, Q., Pacho, F. T., Liu, J., Bhutto, T. A., & Xuhui, W. (2020). The role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in resources acquisition in a new venture: The mediating role of effectuation. SAGE Open, 10(4), 215824402096357. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020963571

- Malmström, M., & Wincent, J. (2018). Bank lending and financial discrimination from the formal economy: How women entrepreneurs get forced into involuntary bootstrapping. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 10, e00096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2018.e0009

- Mardika, D. R. W., Damayanti, T. W., & Supramono, S. (2018). Understanding the determinant of SME owners’ intention to have bank credit. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 17(1), 165–174. https://doi.org/10.17512/pjms.2018.17.1.14

- Martínez-Tur, V., Molina, A., Moliner, C., Gracia, E., Andreu, L., Bigne, E., & Luque, O. (2020). Reciprocity of trust between managers and team members. Personnel Review, 49(2), 653–669. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-08-2018-0319

- McCarthy, S., Oliver, B., & Verreynne, M.-L. (2017). Bank financing and credit rationing of Australian SMEs. Australian Journal of Management, 42(1), 58–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/0312896215587316

- Menkhoff, L., Neuberger, D., & Rungruxsirivorn, O. (2012). Collateral and its substitutes in emerging markets lending. Journal of Banking & Finance, 36(3), 817–834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2011.09.010

- Merhi, M., Hone, K., Tarhini, A., & Ameen, N. (2021). An empirical examination of the moderating role of age and gender in consumer mobile banking use: A cross-national, quantitative study. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 34(4), 1144–1168. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-03-2020-0092

- Montford, W., & Goldsmith, R. E. (2016). How gender and financial self-efficacy influence investment risk taking. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 40(1), 101–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12219

- Moro, A., & Fink, M. (2013). Loan managers ‘ trust and credit access for SMEs. Journal of Banking & Finance, 37(3), 927–936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2012.10.023

- Moro, A., Wisniewski, T. P., & Mantovani, G. M. (2017). Does a manager’s gender matter when accessing credit? Evidence from European data. Journal of Banking & Finance, 80, 119–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2017.04.009

- Moudrý, D. V., & Thaichon, P. (2020). Enrichment for retail businesses: How female entrepreneurs and masculine traits enhance business success. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 54, 102068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102068

- Naegels, V., Mori, N., & D’Espallier, B. (2021). The process of female borrower discouragement. Emerging Markets Review, 50(3), 100837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2021.100837

- Ongena, S., & Popov, A. (2016). Gender bias and credit access. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 48(8), 1691–1724. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmcb.12361

- Richard, O. C., Kirby, S. L., & Chadwick, K. (2013). The impact of racial and gender diversity in management on financial performance: How participative strategy making features can unleash a diversity advantage. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(13), 2571–2582. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.744335

- Savickas, M. L., Nota, L., Rossier, J., Dauwalder, J.-P., Duarte, M. E., Guichard, J., Soresi, S., Van Esbroeck, R., & Van Vianen, A. E. M. (2009). Life designing: A paradigm for career construction in the 21st century. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75(3), 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.04.004

- Shohel, T. A., Niner, S., & Gunawardana, S. (2021). How the persistence of patriarchy undermines the financial empowerment of women microfinance borrowers? Evidence from a southern sub-district of Bangladesh. PLoS ONE, 16(4), e0250000. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250000

- Tang, Y., Deng, C., & Moro, A. (2016). Firm-bank trusting relationship and discouraged borrowers. Review of Managerial Science, 11(3), 519–541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-016-0194-z

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2022). Financing SMEs and entrepreneurs 2022: An OECD scoreboard. https://www.oecd.org/cfe/smes/financing-smes-and-entrepreneurs-23065265.htm

- Themanson, J. R., & Rosen, P. J. (2015). Examining the relationships between self‐efficacy, task‐relevant attentional control, and task performance: Evidence from event‐related brain potentials. British Journal of Psychology (London, England: 1953), 106(2), 253–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12091

- Verma, S., Shome, S., & Patel, A. (2020). Financing preference of listed small and medium enterprises (SMEs): Evidence from NSE Emerge Platform in India. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 13(5), 992–1011. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-04-2020-0100

- Wulandari, E., Meuwissen, M. P. M., Karmana, M. H., & Oude Lansink, A. G. J. M. (2017). Performance and access to finance in Indonesian horticulture. British Food Journal, 119(3), 625–638. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-06-2016-0236

- Xiang, D., & Worthington, A. (2015). Finance-seeking behaviour and outcomes for small- and medium-sized enterprises. International Journal of Managerial Finance, 11(4), 513–530. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMF-01-2013-0005

- Yazdanfar, D., & Öhman, P. (2020). The 2008–2009 global financial crisis and the cost of debt capital among SMEs: Swedish evidence. Journal of Economic Studies, 48(6), 1097–1110. https://doi.org/10.1108/JES-02-2020-0064