?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This is a study about the servant leadership-organizational citizenship behavior debate aimed at examining the effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior through the mediating effect of perceived organizational politics. An explanatory research design and quantitative approach were employed. In the Ethiopian federal public sectors, data were collected using a standard questionnaire from 321 respondents. The present study employed social learning theory and social exchange theory to underpin the mechanism how perceived organizational politics mediates the effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior. To test hypotheses, the study employed structural equation modeling using AMOS software version 26. The findings of the study established that servant leadership has a positive and statistically significant effect on organizational citizenship behavior. In addition, servant leadership has a negative and statistically significant effect on perceived organizational politics. Likewise, perceived organizational politics have a negative and statistically significant effect on organizational citizenship behavior. As it is hypothesized, the finding of the structural equation analysis demonstrated that Perceived organizational politics mediated the effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior. This study is the first empirical study to use perceived organizational politics as a mediating role between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior.

IMPACT STATEMENT

Discover how leaders’ selfless service and employees’ positive contributions can shape a better work environment in Ethiopian public service organizations. This research delves into the link between servant leadership, organizational citizenship behavior, and the effect of perceived organizational politics. By examining these factors, we gain insights into how leaders’ servant behavior can influence employees’ willingness to go extra their job requirements. Ultimately, this study seeks to promote a culture of servant leadership, fostering trust, collaboration, and organizational effectiveness. By shedding light on these dynamics, we hope to inspire leaders and policymakers in Ethiopia and beyond to adopt practices that enhance employee engagement, and public service delivery.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

Organizational citizenship behavior is a key concept in organizational behavior that refers to extra-role employee behaviors that are not formally recognized or rewarded by the organization but that contribute to its effective functioning (de Geus et al., Citation2020; Khan et al., Citation2019; Sharma & Sangeeta, Citation2014). In organizational behavior literature, organizational citizenship behavior includes such as helping colleagues with work-related problems, volunteering for tasks beyond the job requirements, and being a positive ambassador for the organization (Brubaker et al., Citation2015; Huei et al., Citation2014; Turnipseed & Turnipseed, Citation2013). Organizational citizenship behavior has a significant effect on organizational effectiveness by promoting teamwork, encouraging collaboration, promoting a positive work environment, and fostering a sense of shared purpose (Dash & Pradhan, Citation2014; Huei et al., Citation2014; Ingrams, Citation2020; Obedgiu et al., Citation2020).

Organizational citizenship behavior holds significant importance and value in public service organizations (Ingrams, Citation2020). It enhances service delivery by improving efficiency and effectiveness (de Geus et al., Citation2020; Obedgiu et al., Citation2020). When employees engage in organizational citizenship behavior, they willingly assist colleagues, provide support, and contribute to a positive work environment, leading to increased efficiency, effectiveness, and quality of services provided to the public (de Geus et al., Citation2020). Moreover, it plays a pivotal role in fostering a positive organizational climate (Ingrams, Citation2020; Obedgiu et al., Citation2020). Employees that exhibit helpfulness and cooperation toward others contribute to the development of a supportive and positive work environment (Ingrams, Citation2020). This positive climate enhances employee satisfaction, morale, and commitment, ultimately leading to higher productivity and better outcomes in serving the public (Ingrams, Citation2020; Obedgiu et al., Citation2020). Overall, recognizing and encouraging organizational citizenship behavior can contribute to creating a culture of excellence and effectively fulfilling the mandate of serving the public interest.

Although numerous researchers have demonstrated that organizational citizenship behavior enhances organizational effectiveness, Kumasey et al. discovered that public service organization employees exhibit lower levels of commitment towards implementing organizational citizenship behavior compared to their private sectors. For this reason, public service organizations’ service delivery is inefficient (de Geus et al., Citation2020; Ingrams, Citation2020). It is essential to examine the causes of employees in public service organizations’ lack of commitment to displaying organizational citizenship behavior. It is recommended that further research be done to look at the factors that affect organizational citizenship behavior in public sector organizations by De Geus et al. (Citation2020). To end with, the study takes as an initial research gap to conduct the current study.

One of the best ways to promote organizational citizenship behavior is through the use of servant leadership (Amir, Citation2019; Bambale et al., Citation2015; Elche et al., Citation2020; Qiu & Dooley, Citation2022). The concept of servant leadership has gained increasing attention in recent years as a leadership approach that emphasizes the importance of serving the needs of employees, thereby fostering a positive work environment and promoting positive outcomes such as organizational citizenship behavior (Eva et al., Citation2019; van Dierendonck, Citation2011). Servant leadership is characterized by leaders who prioritize the well-being, growth, and development of their employees (Liden et al., Citation2008). They exhibit behaviors such as empowerment, support, and trust-building, which create a positive social exchange environment (Van Dierendonck & Nuijten, Citation2011). This positive social exchange fosters employee engagement and extra-role behaviors that go beyond their formal job requirements, leading to increased organizational citizenship behavior (Van Dierendonck & Nuijten, Citation2011; Liden et al., Citation2008). Beyond other types of leadership, servant leadership has strong linkages with organizational citizenship behavior, because servant leaders provide an example for their employees by acting with integrity, humility, and empathy (Dannhauser, Citation2007; Dittmar, Citation2006; Van Dierendonck & Nuijten, Citation2011). This example of good behavior might encourage employees to take similar acts (Ehrhart, Citation2004; Walumbwa et al., Citation2010). When employees witness a servant leader’s commitment to going above and beyond the call of duty, they are motivated to engage in organizational citizenship behavior (Bambale et al., Citation2015; Ehrhart, Citation2004).

Despite noted this importance, however; the nexus between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior were found to be inconsistent and inconclusive. For example, whereas some researchers (e.g. Harwiki, Citation2013; Strajhar et al., Citation2016) showed no significant relationship between the constructs, Mahembe and Engelbrecht (Citation2014) and Elche et al. (Citation2020) discovered a strong association between the constructs. For this reason, the study takes the ‘black box’ issue in the nexus between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior as a second research gap to carry out the present study. The ‘black box’ issue in the nexus undoubtedly demonstrates that there is a clear need for more study by taking into account any mediating or intervening variables that might help to understand how and why servant leadership affects organizational citizenship behavior. Due to this, previous researchers like Mahembe and Engelbrecht (Citation2014), Elche et al. (Citation2020), Gnankob et al. (Citation2022), Zia et al. (Citation2022) etc. contributed to a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms that explain the link between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior. While previous researchers has identified different mediating variables, there is still a need to better understand the underlying mechanisms that explain this link (Hanaysha et al., Citation2022; Zehir et al., Citation2013). In this respect, perceptions of organizational politics are considered as a relevant mediation variable in the nexus between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior. This is because some researchers are suggested that perceptions of organizational politics may play a mediating role in the link (Khattak et al., Citation2022; Qiu & Dooley, Citation2022). Perceptions of organizational politics refers to employees’ perceptions of the use of power and influence in the organization for personal gain or to further the interests of particular groups, often at the expense of others (Vigoda & Cohen, Citation2002).

The study argues that servant leadership theory can support the possible mediating role of perceptions of organizational politics in the nexus between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior. According to the theory of servant leadership, leaders who prioritize helping others have the power to shape how their employees perceive their organizational climate and their inclination to engage in organizational citizenship behavior (Eva et al., Citation2019; Liden et al., Citation2008, Citation2014; Walumbwa et al., Citation2010). Servant leadership prioritizes fairness and justice to promote supportive work environment (Liden et al., Citation2014). By fostering an environment of fairness and justice, they reduce employees’ perceptions of political behaviors such as self-interest and favoritism (Khattak et al., Citation2022). Because of this, employees are more likely to think that the organization is fair and honest, which positively affects their willingness to engage in organizational citizenship activities (Byrne, Citation2005; Khan et al., Citation2019; Mathur et al., Citation2013; Shafiq et al., Citation2017). Based on this argument, the mediating role of perceptions of organizational politics is explained in the present study as: if leaders who are viewed as not servants by their subordinates run the risk of decline in citizenship behavior due to an increase in perceptions of organizational politics and vice versa. Therefore, examining the mediating role of perceptions of organizational politics in the nexus between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior is vital to advance a more inclusive understanding of the factors affecting organizational citizenship behavior. Since there are no empirical studies revealing the mediating role of perceptions of organizational politics, this study fills such a gap. To end with, the present study takes this as final research gap to conduct the present study. Therefore, this study will contribute in the literature by examining the nexus between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior with a mediating role of perceptions of organizational politics.

2. Review of literature

2.1. Organizational citizenship behavior

Chester Barnard’s Citation1938 theory of cooperative systems is credited with developing the concept of organizational citizenship behavior. Barnard defined organizations as cooperative systems in which individuals work together to achieve common goals (Barnard, Citation1938). Barnard also stressed that the ‘willingness of persons to contribute efforts to the cooperative system is indispensable’. These arguments suggest that the willingness to cooperate among employees is crucial for achieving organizational goals and objectives. Barnard’s (Citation1938) willingness to cooperate idea and organizational citizenship behavior are conceptually similar as they both are voluntary (Podsakoff et al., Citation2000). What Organ referred to organizational citizenship behavior as ‘discretionary behavior’ in the previous three decades was Barnard’s willingness to cooperate, which has been documented in the literature for more than seven decades (Bambale et al., Citation2015; Ocampo et al., Citation2018; Podsakoff et al., Citation2000).

Katz and Kahn’s (1966) concept of innovative and spontaneous behavior has been cited also as an important originator to the development of the concept of organizational citizenship behavior (Turnipseed, Citation2002). Katz and Kahn argued that innovative and spontaneous behavior is a form of extra-role behavior that goes beyond the formal job requirements and contributes to the effective functioning of the organization (Turnipseed, Citation2002). Katz and Kahn’s concept of innovative and spontaneous behavior shares some similarities with the concept of organizational citizenship behavior, which was developed by Organ (1988) several decades later (Chang et al., Citation2021). Both concepts refer to voluntary behaviors that go beyond formal job requirements and contribute to the effective functioning of the organization.

Smith, Organ and Near (Citation1983) were the first scholars to introduce the concept of organizational citizenship behavior. Smith et al. identified two subscales of organizational citizenship behavior: altruism and compliance. In 1988, Organ defined organizational citizenship behavior as individual behavior that is discretionary, not directly recognized by the formal reward system, and that in the aggregate promotes the effective functioning of the organization. Organ (1988) added three more dimensions (i.e. courtesy, civic virtue, and sportsmanship) to the existing two Smith et al.’s (Citation1983) organizational citizenship behavior dimensions. Now there are five organizational citizenship behavior dimensions (i.e. altruism, courtesy, civic virtue, conscientiousness, and sportsmanship). Organ’s (1988) concept of organizational citizenship behavior is believed to have originated from Barnard’s (Citation1938) (Ocampo et al., Citation2018). Researchers have used these dimensions to measures of organizational citizenship behavior and contribute to the effective functioning of the organization.

Researchers continued to investigate the development of organizational citizenship behavior conceptualization. Williams and Anderson (Citation1991) proposed a distinction between two types of organizational citizenship behavior (OCB): Organizational citizenship behavior directed toward the benefit of other individuals (OCBI) and Organizational citizenship behavior directed toward the benefit of the organization (OCBO). Over the four decades of organizational citizenship behavior research, the construct has been conceptualized in several ways. However, Podsakoff et al. (Citation2009) reported that the most popular conceptualizations are the dimensions developed by Williams and Anderson (Citation1991), which were later validated by Lee and Allen (Citation2002).

In recent years many scholars have begun to underscore the importance of organizational citizenship behaviors in public service organizations. Organizational citizenship behaviors findings have encouraged public service organizations to use citizenship behavior to increase organizational performance (de Geus et al., Citation2020). Obedgiu et al. (Citation2020) described that when engaging in organizational citizenship behavior, civil servants are seeking for ways of enhancing organizational performance by contributing to a better organizational culture and providing better services. Obedgiu et al. stated that organizational citizenship behavior is the possible solution in meeting citizen satisfaction as it is among the important factors influencing organizational efficiency. The community demands that all state apparatus be able to prepare a condition where state administration is able to support the smooth implementation of the duties and functions of the administration of government, along with their development and service, based on the principles of good governance (Obedgiu et al., Citation2020). Therefore, Organizational citizenship behaviors are advantageous to public service organization that strives to achieve extraordinary outcomes (Obedgiu et al, Citation2020). Public-sector leaders who encourage public servants to engage in organizational citizenship behaviors will contribute to lessen the bureaucratic red tape and ultimately improving organizational performance (De Geus et al., Citation2020).

Although previous research has shown that organizational citizenship behavior can improve public service organizational effectiveness, Kumasey et al. reported that public service organization employees are not as committed to engaging organizational citizenship behavior as compared to private sector employees, despite their continued enjoyment of job security and better conditions of service. But, organizational citizenship behavior has the potential to address government challenges, public demands and enhance efficiency and effectiveness (Obedgiu et al., Citation2020). When engaging in organizational citizenship behavior, civil servants are seeking for ways of enhancing organizational performance by contributing to a better organizational culture and providing better government services (Obedgiu et al., Citation2020). Within the public service organizations, Ingrams (Citation2020) assert that organizational citizenship behavior has special importance due to the relevance of generalized citizenship in government-citizen relationships and the goals of public administration reforms to achieve greater organizational responsiveness to citizens. De Geus et al., (Citation2020) also describe that, while growth was relatively steady in the private sector, studies in the public sector took longer to develop and have lately started to gather pace. Moreover de Geus et al., (Citation2020) stating that, there has so far been limited empirical and theoretical exploration regarding organizational citizenship behavior in the public service organization.

2.2. Servant leadership

The idea of servant leadership has its roots in ancient philosophy and religious texts. Servant leadership was prominence in spirituality (Mark 10:43) and exemplified by Jesus to his Disciples by stating that ‘Whoever wants to be a leader must be servant’. The idea has been initiated and introduced into contemporary social organizations by American Management and leadership scholar, Greenleaf in 1970s (Graham, Citation1991). When came up with the idea of servant leadership as an alternative leadership paradigm, Greenleaf argued it as a ‘better leadership approach that puts serving others-including followers, customers, and community, as the number one priority’. Greenleaf further stated that the servant-leader is servant first, it begins with the natural feeling that one wants to serve, to serve first (Bowman, Citation2005). This means that their primary motivation is to serve others, rather than to acquire power, wealth, or status (Bowman, Citation2005). Greenleaf believed that this natural desire to serve is what distinguishes servant-leaders from other types of leaders.

Larry C. Spears, the former CEO of the Greenleaf Center for Servant Leadership is another scholar who has contributed to the development of the concept of servant leadership (Van Dierendonck & Nuijten, Citation2011). Spears listed 10 essential traits of servant leaders, which include listening, empathy, healing, awareness, persuasion, conceptualization, foresight, dedication, community building and stewardship (Van Dierendonck & Nuijten, Citation2011). Farling, Stone, and Winston (Citation1999) were the first to empirically examine the servant leadership concept. According to Farling et al., servant leadership entails vision, trust, credibility, and service. Another servant leadership conceptualization comes from Laub (Citation1999). Laub (Citation1999) developed Organizational Leadership Assessment (OLA) tool for assessing the extent to which an organization exhibits servant leadership characteristics. Laub identified six measures of servant leadership: valuing people, developing people, building community, displaying authenticity, providing leadership and sharing leadership. Ehrhart’s (Citation2004) was another prominent scholar who contributed to the study of servant leadership. Ehrhart’s (Citation2004) developed Organizational Citizenship Behavior Servant Leadership (OCBSL) tool for assessing servant leadership. Ehrhart’s scale is a 14-item survey that leads to seven dimensions: (a) forming relationships with subordinates, (b) empowering subordinates, (c) helping subordinates grow and succeed, (d) behaving ethically, (e) having conceptual skills, (f) putting subordinates first, and (g) creating value for those outside organization. Another important contribution to the study of servant leadership comes from Barbuto and Wheeler in 2006 (van Dierendonck, Citation2011). Barbuto and Wheeler developed the Servant Leadership Questionnaire (SLQ) tool for assessing servant leadership scales. The servant leadership questionnaire consists of 23 items. The items are organized into five categories: Altruistic calling, emotional healing, persuasive mapping, wisdom and organizational stewardship. Liden et al. (Citation2008) developed Servant Leadership Scale (SLS) scale. Liden et al. studied the prior servant leadership taxonomies and created an instrument with nine dimensions: creating value for the community, emotional healing, conceptual skills, helping subordinates grow and succeed, putting subordinates first, empowering, behaving ethically and servant-hood. Finally, a multi-dimensional scale called the Servant Leadership Survey (SLS) was developed and validated by Dierendonck and Nuijten in 2011. The SLS scale consisted eight dimensions: empowerment, accountability, standing back, humility, authenticity, courage, forgiveness and stewardship. Overall, servant leadership is a multifaceted concept that has been defined and explored by a variety of scholars. Although all definitions of servant leadership vary in focus and methodology, they all share common idea i.e. meeting the needs of others and fostering a positive work environment.

There are some reasons why servant leadership preferable than other leadership styles for public service organizations: Public service organizations exist to serve citizens and the community (Denhardt & Denhardt, Citation2000). Similarly, servant leadership prioritizes the needs and interests of others, which aligns well with the mission and values of public service organizations (Ehrhart, Citation2004; van Dierendonck, Citation2011). Public service organizations are increasingly recognizing the importance of collaboration and teamwork in achieving their goals (Denhardt & Denhardt, Citation2000). In relation to this, servant leadership can help create a culture of collaboration and encourage employees to work together to achieve common goals (Khuwaja et al., Citation2020). Today, public service organizations are tasked with numerous missions, and demanded to look for solutions for multi-faceted institutional challenges and needs (Khuwaja et al., Citation2020). To realize these missions or mandates, they need leaders of modern times who are selfless, authentic, caring, ethical and able to provide genuine guidance in leading and making decisions (Miao et al., Citation2014). Thus, servant leadership characterized by the above features has now become demanding for public service organizations (Khuwaja et al., Citation2020). Khuwaja et al. (Citation2020) examined servant leadership in public service organizations and indicated that it is very important that leaders hold appropriate leadership styles like servant leadership to transform public service organizations. Miao et al. (Citation2014) also urged public leaders to serve not steer, the term servant leadership has found scant attention in the public sector literature. Therefore, like for other social organizations, servant leadership best fits to public service organizations. It aligns well with public service organizations mission and values.

2.3. Perceptions of organizational politics

There are three approaches that dominate the literature on organizational politics: (1) studies on influence tactics and actual political behavior (Kipnis et al., Citation1980); (2) studies on perceptions of organizational politics (Gandz and Murray, Citation1980); and (3) studies on political skill (Ferris et al., Citation2007). This study focused on perceptions of organizational politics. The Lewin idea that people react based on their perceptions of reality rather than on objective reality was the foundation of the perceptions of organizational politics approach (Kimura, Citation2012). For most employees within an organization, and indeed for the public in general, what determines an individual’s reaction to a particular situation is undoubtedly their perception rather than the reality of that situation per se (Cheng et al., Citation2019). Decades of empirical research have indicated that perceptions of organizational politics in the workplace have received negative responses from employees. Some researchers also argued that if the organizational environment is political, employees’ investment in the organization becomes more risky (Hochwarter et al., Citation2003). In a political environment, incentives are frequently given based on informal power structures rather than on contributions or efforts, and the rules may vary from day to day (Kimura, Citation2012). Because of this uncertainty, individuals are less likely to be confident that their efforts will produce any outcomes beneficial to themselves (Kacmar et al., Citation2013). Therefore, reducing employees’ perceptions of organizational politics should be viewed as an important issue both in the theory and practice of organizational management (Kimura, Citation2012).

Examining how organizational politics are perceived in public service organizations is crucial for a number of reasons. According to Cropanzano et al. (Citation1997) an employee’s general psychological health may be directly impacted by their perceptions of organizational politics. By examining these perceptions, public service organizations can identify sources of employee distress and implement strategies to mitigate negative effects, thereby promoting employee well-being (Grawitch et al., Citation2006). Previous research has shown differences in the implications of organizational politics between public service and private organizations. Organizational politics is higher in the public sectors than in the private sector (Vigoda-Gadot & Kapun, Citation2005). It implies that organizational politics has more damaging effect in public service organizations than private organizations. In this regard, Vigoda (Citation2002) discussed that, it is also important to note that the silent effect of politics in organization politics can spill over beyond the formal boundaries of public organizations. Vigoda added attitudes and behaviors of public servants toward citizens/clients partially reflect the effectiveness and efficiency of public administration. Higher levels of organizational politics may lead employees to exercise lower levels of performance (Vigoda, Citation2002). When public officials show hampered formal or informal outcomes, the citizens are negatively affected (Vigoda, Citation2002). Vigoda stated that, they obtain inferior services from discouraged public servants, and as a result, may develop a negative perception towards the entire public system. Therefore, employees need political skill to manage the perceptions of organizational politics (Vigoda, Citation2002). In conclusion, it is critical to study how organizational politics are perceived in public service organizations. It offers perceptions on the wellbeing of workers (Al Jisr et al., Citation2020). Public service organizations may create interventions and strategies that improve employee experiences, cultivate a healthy work environment, and increase overall organizational effectiveness by knowing these perceptions (Al Jisr et al., Citation2020). Given that political factors may have a big impact on Ethiopian public service organizations, studying this issue is very significant (Reda, 2021).

3. Conceptual framework

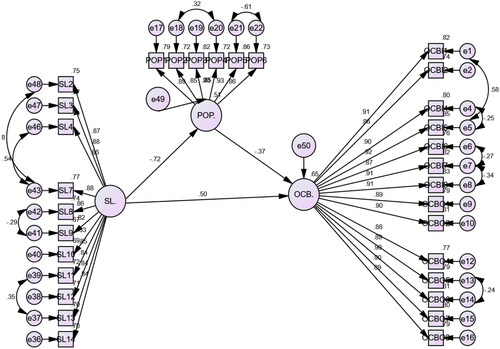

See .

Figure 1. Conceptual framework.Source: Ehrhart (Citation2004) and Vigoda-Gadot (Citation2007).

4. Hypothesis development

4.1. Servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior

Servant leadership may influence employee organizational citizenship behavior in a number of ways. Servant leaders significantly encourage organizational citizenship behavior by serving as role models for their employees (Ehrhart, Citation2004; Liden et al., Citation2014; Mahembe & Engelbrecht, Citation2014). Servant leaders consistently exhibit empathy, humility, and integrity (Liden et al., Citation2014). Employees are motivated to take these qualities and engage in organizational citizenship behavior by the actions of their leaders (Trong Tuan, Citation2017) For example, when a servant leader consistently goes above and beyond to support others, employees are more inclined to participate in organizational citizenship activities (Trong Tuan, Citation2017). Moreover, according to Bambale et al. (Citation2015), servant leaders who show a genuine care for their followers’ needs and treat them fairly may also encourage organizational citizenship behavior among their employees. Generally, when employees observe a servant leader’s commitment, they are motivated to engage in organizational citizenship behaviors that advance the organization’s performance as a whole (Bambale et al., Citation2015; Liden et al., Citation2008, Citation2014). Therefore, in light of the above argument, the current study proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Servant leadership has a positive effect on organizational citizenship behavior.

4.2. Servant leadership and perceptions of organizational politics

Servant leadership theory suggests that leaders characterized by their focus on serving others have the potential to shape employees’ perceptions of the organizational climate (Eva et al., Citation2019; Liden et al., Citation2008, Citation2014; Walumbwa et al., Citation2010). One area where servant leadership may have an influence is how people perceive their organization as political (Khattak et al., Citation2022). Organizational politics are characterized by self-interest, manipulation, and the pursuit of personal agendas, all of which can result in unfavorable and unhealthy working environments (Hochwarter, Citation2012). Servant leadership emphasizes justice and fairness. By encouraging an atmosphere of justice and fairness, Servant leadership reduce employees’ perceptions of political behaviors such as self-interest and manipulation (Khattak et al., Citation2022).

Moreover, servant leadership can influence perceptions of organizational politics by fostering transparency and trust (Kaya et al., Citation2016). By being transparent in their decision-making processes, servant leaders build trust with their employees (Thakore, Citation2013). When employees perceive their leaders as reliable and believe that decisions are made with honesty and fairness, their perceptions of organizational politics will be reduced (Kaya et al., Citation2016). In general, servant leaders create an environment where perceptions on political behavior are diminished by fostering an atmosphere of transparency and trust, advocating for justice and fairness, empowering of employees, and cultivating an ethical climate (Kaya et al., Citation2016). In light of the above argument, the current study proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2: Servant leadership has a negative effect on perceptions of organizational politics.

4.3. Perceptions of organizational politics and organizational citizenship behavior

How employees perceive organizational politics has a big influence on their organizational citizenship behavior (Tripathi et al., Citation2023). Employees who believe that there is a lot of organizational politics going on that is motivated by unfairness, bias, and self-interest may lose trust in the system and stop participating in organizational citizenship behavior (Kaur & Kang, Citation2020; Tripathi et al., Citation2023).

The impression of political behaviors fosters a hostile work environment and makes employees doubt the organization’s fairness (Ferris et al., Citation2007). Because of this, employees may be less likely to engage in organizational citizenship-that is, to assist colleagues and offer to take on extra work (Khattak et al., Citation2022; Randall et al., Citation1999). Previous scholars have examined the relationship between perceived organizational politics and organizational citizenship behavior and consistently found a negative association between perceptions of organizational politics and various facets of organizational citizenship behavior (Khattak et al., Citation2022; Obedgiu et al., Citation2020; Randall et al., Citation1999). These studies suggest that employees who perceive high levels of organizational politics are less likely to engage in discretionary behaviors that benefit the organization. In light of the above argument, the present study suggests the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: perception of organizational politics has negative effect on the organizational citizenship behavior

4.4. Perceptions of organizational politics as a mediating role between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior

The effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior can be explained by perceptions of organizational politics acting as a moderating role. Servant leadership, characterized by its focus on serving others, has the potential to shape employees’ perceptions of the organizational climate and their inclination to engage in organizational citizenship behavior (Kaya et al., Citation2016; Liden et al., Citation2008). Servant leaders make a positive work atmosphere, emphasizing to transparency, justice, and ethical decision-making (Liden et al., Citation2008). By promoting an environment of trust and honesty, servant leaders reduce employees’ perceptions of political behaviors such as self-interest and favoritism (Kaya et al., Citation2016). Consequently, employees are more likely to perceive the organization as fair and reliable, which positively influences their willingness to engage in organizational citizenship behavior (Liden et al., Citation2014). According to this line of reasoning, the mediating role of perceptions of organizational politics is explained as: leaders who are perceived by their employees as not being servants face the risk of failure in engaging organizational citizenship activities as a result of increasing perceptions of organizational politics, and vice versa. Thus, this study will contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms through which servant leadership affects organizational outcomes, highlight on the significance of minimizing perceptions of organizational politics. In light of the above argument, the present study suggests the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4: Perceptions of organizational politics mediate the nexus between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior, such that the positive effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior is weakened when perceived organizational politics is high.

5. Research methodology

5.1. Research setting

Ethiopian federal public sectors were the subject of the study. The headquarters of every federal public sector are located in Addis Abeba, the Ethiopian capital. Public sectors in Ethiopia are organized at the federal, regional, and local levels (Tensay & Singh, Citation2020). According to Tensay and Singh (Citation2020), federal public sectors have a macro-level impact on the social, economic, and political activities of the country. This argument led to the present study’s emphasis on federal public sectors.

5.2. Sampling procedures

A multi-stage random sampling procedure was employed, considering the nature of sectors as strata. The federal public sectors were first divided into three sectors (strata), and then two organizations were chosen at random from each sector. The sample organizations were chosen at random using this procedure: The researcher initially numbered all organizations in each category on a piece of paper, then mixed these slips and picked one slip at a time. According to Tensay and Singh (Citation2020), this study took 30% of the total organizations, demonstrating a reasonable representation of the population. In the second phase, simple random sampling techniques are employed to select the respondents.

The sample size was calculated using the formula developed by Mugenda at a 95% confidence level, as shown in the following equation.

where N = population size;

n = desired sample size

e = tolerance at desired level of confidence

The sample units are frontline employees. Based on the above formula, the sample size of the study was 345. However, Israel, 1992 suggested that researchers could add a 30% sample size to minimize the non-response rate. Therefore, the study used 449 samples. Moreover, regarding the structural equation model, sample size determination is critical because it is a large sample size statistical technique (Collier, Citation2020). According to Collier, a large sample size is necessary to improve the statistical power and trustworthiness of the results.

5.3. Measurements of variables

Servant leadership was measured by a 14-item servant leadership scale developed by Ehrhart (Citation2004). Van Dierendonck and Nuijten (Citation2011) described this scale as a one-dimensional model of servant leadership. Moreover, this scale has been used because of its wide acceptability in contemporary leadership research (Liden et al., Citation2014). It is also employed by recent researchers in public sectors (e.g. Gnankob et al., Citation2022; Shim & Park, Citation2019). Organizational citizenship behavior was measured by 16 items developed by Lee and Allen (Citation2002). Regarding this, Hameed Al-ali et al. (Citation2019) discussed that organizational citizenship behavior is best represented as a uni-dimensional measure. This scale has been employed by recent researchers in public sectors (e.g. Khattak et al., Citation2022). Perceptions of organizational politics were measured by a six-item scale developed by Hochwarter et al. (Citation2003). This measurement was employed in public sectors by Kacmar et al. (Citation2013).

Closed-ended questionnaire was prepared in the present study to collect data. Kumar, 2011 indicated that a questionnaire is the most popular method used to collect quantitative data. To ensure uniformity of measurement scale across study variables, a five-point Likert scale type ranging from 5 (Strongly Agree) to 1 (Strongly Disagree) was employed for this study. The questionnaire has consisted of two parts. The first part was demographic variables that include gender, age, educational level, and experience of respondents. The second part consisted of the main study variables that were designed to gather data to answer the research questions. Before data are gathered, the validity and reliability of the research instrument were checked through the appropriate statistical procedure. Once this stage is done, the self-administered questionnaire was distributed to the participants of the study. Then, once the required response rate was achieved then the obtained was ready for analysis.

6. Data analysis and results

The statistical tools employed for this study were Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) plus AMOS software Version 26. AMOS is the most user-friendly of all the SEM software programs (Collier, Citation2020).

6.1. Characteristics of respondents

The demographic profile data (n = 321) result indicated that the majority of the respondents are male, married, hold bachelor’s degrees and are experienced. Specifically, revealed that, of the 321 respondents, 53.6% are male employees. The highest numbers of respondents’ ages were within the ranges of 31–40 years (38.3%). The next was within 41–50 years (29.3%). The third of them were within the 21–30 years age group (24%), and the rest of them were within the 51–60 years age group (8.4%). In terms of educational level, over half of them (54.8%) acquired a first-degree certificate. Those who obtained master’s degree status were 35.2%, and diplomas made up 10%. The highest number of employees regarding experience was between 6 and 10 years (28.7%), while the least were those who worked within 1–5 years (2.2%). Generally, the study can conclude that respondents are representative of the population in terms of gender, age, education, and experience.

Table 1. Demographic information.

6.2. Descriptive and correlational analysis

shows descriptive statistics and correlations among the study variables. This table reveals that the correlations between the research variables were in the expected direction. Servant leadership (SL) was positively correlated with organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) (r = 0.75, p < .01) and negatively correlated with perceptions of organizational politics (POP) (r = −0.71, p < .01). Perceptions of organizational politics (POP) was negatively correlated with organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) (r = −0.72, p < .05).

Table 2. Descriptive and correlation result.

6.3. Preliminary analysis

Before running directly into confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) operations, the study made a preliminary analysis of the accuracy of the data. It is widely documented that data preparation and screening are critical issues in structural equation model (SEM) (Hair et al., Citation2012). Therefore, this study examined the missing data. There were 10 missing values in the variable screening. More precisely, SL-10, SL-13, OCB-5, and POP-5 items have one missing value each. OCB-3 has two missing values. And POP-1 has four missing values. At the end, all missing values were treated by employing the imputation (series mean) method.

The study employed Mahalanobis distance to identify the potential outliers. A good rule of thumb is that if the p1 and p2 values are less than 0.001, these are cases denoted as outliers (Collier, Citation2020). Therefore, seven (7) observations were less than 0.001, so they are removed from the dataset. Regarding the normality test, the present study calculated the skewness and kurtosis, and it was found that the values are within the normal range, indicating that there is no problem with the normality of the data. Lastly, we examined the issue of multicollinearity by conducting the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and tolerance tests. The tolerance values were found to be greater than 0.10, and the VIF values were less than 3. Based on these results, we concluded that there is no multicollinearity concern in our study. Therefore, we assume that no multicollinearity problem exists. Generally, the current study discovered that data preparation and screening were properly analyzed, and the variables are eligible to enter into SEM analysis.

Since the data were gathered from one source, it might raise concerns about common method bias. Thus, to mitigate such issues, this study utilized Podsakoff et al. (Citation2003) suggestions of allowing the respondents’ answers to be confidential to avoid desirability bias. Moreover, the study also applied Harman’s one-factor analysis to check for common method bias. Harman’s one-factor test can be performed with confirmatory factor analysis, where all indicators are purposely loaded on one factor to determine model fit and are considered to have no common bias if the model is unfit (Collier, Citation2020). Accordingly, all indicators are loaded into one latent variable (i.e., Servant leadership in this case), and the result revealed that there is no common method bias in the model (CMIN/DF = 7.360, CFI = 0.792, TLI = 0.772, NFI = 0.768, GFI = 0.493, RMSEA = 0.141).

6.4. Evaluation of the measurement model

The current study hypothesized a three-factor measurement model (servant leadership, perceptions of organizational politics, and organizational citizenship behavior) aimed at validating the appropriate fitness of the proposed model. In relation to the factor measurement model, van Dierendonck (Citation2011) argued that servant leadership is considered the first-order factor. Similarly, Walumbwa et al. (Citation2010) argued that organizational citizenship behavior should be considered the first-order factor. Also, Crawford et al. (Citation2019) and Kacmar et al. (Citation2013) discussed perceptions of organizational politics as the first-order factor.

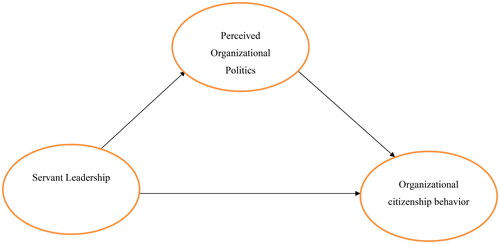

In SEM analysis, the measurement model is the first stage to be analyzed with the objective of testing the construct validity (convergent and discriminant validity) of the study variables. To assess convergent validity, factor loading, average variance extraction, and composite reliability were considered. The acclaimed values for factor loading are supposed to be greater than 0.70, for AVE at least 0.5, and for CR greater than 0.7. Thus, the CFA result of each construct is presented in , which displays that the factor loading of each indicator is beyond the threshold. Moreover, the AVE of each variable was above 0.5, and that of CR was greater than 0.7. The second objective of the measurement model is to test discriminant validity. Discriminant validity is the degree to which a variable is strictly different from others. To verify the discriminant validity, an overall CFA was conducted by combining the three constructs together (presented in ). The CFA result shows that the overall measurement model was properly fit with the sample data (χ2/df =2.495; RMR = 0.0301; CFI = 0.952; TLI = 0.946; and RMSEA =0.068), which is consistent with the fit indices of Hair et al. (2010). Model fit improvement was conducted in the study. The first improvement was that five items (i.e. SL-1, SL-5, SL-6, OCBI-3, and OCBO-3) from the indicators of servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior were removed due to low factor loadings (<0.70). According to Hair et al. (2010), factor loadings greater than 0.70 are better at explaining unobserved constructs in the study. The second improvement was that modification indices were checked and error terms were correlated.

Figure 2. Measurement model. Note: OCB = organizational citizenship behavior, POP = perceptions of organizational politics and SL = servant leadership. Source: AMOS Result (2023).

Table 3. Loadings, reliability, and convergent validity.

In the overall measurement model, discriminant validity is established when the square root of AVE for the construct is greater than its correlation with other constructs in the study (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Therefore, in the present study, discriminant validity was established. The results of discriminant validity are presented in .

Table 4. Discriminant validity of study variables.

6.5. Evaluation of the structural model

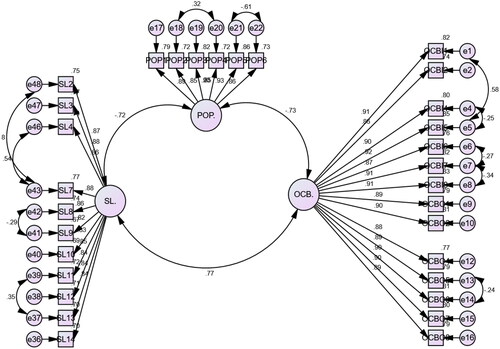

The second stage of SEM analysis is evaluating the structural model. Prior to testing the Hypothesis, first the structural model fitness with the theory was validated based on the fit measurement indices. The resulting model provided a good fit for the data: CMIN/df = 2.495, CFI = 0.952, TLI = 0.946, SRMR = 0.0338 and RMSEA = 0.068. shows the structural proposed model proposing the mediation effect of perceptions of organizational politics between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior. In this model, the path from servant leadership to perceptions of organizational politics as well as the path from perceptions of organizational politics to organizational citizenship behavior was found statistically significant. Moreover, servant leadership and perceptions of organizational politics together account for 65% of the variance in organizational citizenship behavior, indicating that both servant leadership and perceptions of organizational politics are critically relevant factors in enhancing organizational citizenship behavior.

6.6. Hypothesis testing

To test the Hypothesis of the study, the study employed SEM. As it is displayed in , the SEM analysis result demonstrated that servant leadership has a significant positive effect on organizational citizenship behavior (β = 0.674, t = 8.955, p < .05), supporting Hypothesis 1. Likewise, servant leadership has a significant negative effect on perceptions of organizational politics (β = −0.941, t = −13.562, p < .05), supporting Hypothesis 2. Similarly, perceptions of organizational politics have a significant negative effect on organizational citizenship behavior (β = −0.374, t = −6.879, p < .05), supporting Hypothesis 3. The fourth Hypothesis of the study was to test the mediation effect of perceptions of organizational politics between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior. In the AMOS analysis, the researcher performed 5000 number of bootstraps using a biased confidence interval of 95%. The result revealed that the mediation effect was significant (β = 0.352, p < .05), supporting Hypothesis 4. Furthermore, the direct effect was also found significant (β = 0.674, p < .05). Hence, perceptions of organizational politics mediated the effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior. A summary of the mediation analysis is presented in .

Table 5. structural model assessment.

Table 6. Indirect effect of perceptions of organizational politics.

6.7. Discussion

The study examined the mediating effect of perceptions of organizational politics between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior. To study the mediation effect, the effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior was examined at the first stage. The result shows that servant leadership has significant effect on the organizational citizenship behavior in the federal public service organizations in Ethiopia. This finding is consistent with earlier studies (Aziz et al., Citation2018; Elche et al., Citation2020; Khattak et al., Citation2022; Mahembe & Engelbrecht, Citation2014; Trong Tuan Citation2017). For example, Elche et al.’s (Citation2020) study found that employees’ organizational citizenship behavior is significantly impacted by a supervisor’s servant leadership. Additionally, Trong Tuan (Citation2017) came to the conclusion in their research that organizational citizenship behavior of public sector employees was significantly predicted by servant leadership. Furthermore, researchers such as Aziz et al. (Citation2018) have demonstrated that servant leaders are typically seen favorably by their subordinates, which eventually translates into improved organizational citizenship behavior. According to a study by Elche et al. (Citation2020) servant leadership in public service organizations has a strong relationship with employees’ organizational citizenship behavior because servant leaders focus on the needs of their followers and recognize their responsibility to followers. Elche et al. (Citation2020) further said that organizational citizenship behavior has been favorably associated in the research with servant leadership, which places a strong emphasis on improving people, organizations, and communities. The presence of organizational citizenship behavior in an organization can increase effectiveness through mechanisms such as increased organizational productivity, more effective use of scarce resources or increased organizational flexibility (Mahembe & Engelbrecht, Citation2014). To this end, the study agreed that when public service organizations policy advocates desire to incite the citizenship behaviors of the employees in the organizations, they should be worried about whether or not the leaders are servants. Simply said, leaders within the public service organizations should be promoting leading by example (van Dierendonck, Citation2011).

The second stage was to examine the effect of servant leadership on perceptions of organizational politics. The result revealed that servant leadership has a negative effect on perceptions of organizational politics. This means that servant leaders can reduce employee’s perceptions of organizational politics. Employees’ perceptions of organizational politics refer to their perceptions about the way politics or power is exercised within their organization (Hochwarter et al., Citation2020). When employees perceive their organization is a political arena, they believe power struggles, conflicts of interest, and favoritism are commonplace in their workplace (Gandz & Murray, Citation1980; Hochwarter et al., Citation2020; Mintzberg, Citation1985). This can create a negative work environment that can lead to lower levels of organizational effectiveness (Hochwarter et al., Citation2020; Mintzberg, Citation1985). These perceptions of organizations politics is influenced by the behavior of leaders and colleagues. In relation to this, Khattak et al. (Citation2022) stated servant leadership is particularly important in organizational cultures characterized by high perceptions of organizational politics. This means that, servant leaders can help to reduce perceptions of organizational politics by prioritizing the needs of their followers, treating employees fairly and ethically. In other words, if leaders show servant behavior, their employees are thus more likely to learn other-serving behavior and reduce their perception of organizational politics. Conversely, if leaders behave not servant, their subordinates are thus more likely to learn self-serving behavior and increase their perception of organizational politics.

The finding of the study supports previous studies conducted by scholars such as Kaya et al. (Citation2016) and Khattak et al. (Citation2022). According to Kaya et al. (Citation2016), employees are less likely to perceive politics within the organization when they believe that their leaders are looking out for their best interests and are committed to fostering a healthy work environment. According to Khattak et al., servant leaders may lessen the detrimental effects of organizational politics on staff employees and the organization as a whole by fostering a culture of trust and cooperation. One of a leader’s main duties is to create an atmosphere that is fair, healthy, and supportive for the employees (Khattak et al., Citation2022). This can help to reduce the level of organizational politics and positively impact organizational effectiveness. Generally, the study is carried out in federal public service organizations in Ethiopia, and the findings show that perceptions of not servant leadership trigger individuals’ perceptions of organizational politics. Therefore, public service organization should promote servant leadership that can reduces perception of organization politics and ultimately improve the organizational effectiveness.

The third stage was to examine the effect of perceptions of organizational politics on organizational citizenship behavior. The study found that a perception of organizational politics has negative effect on organizational citizenship behavior. The negative effect means if employees perceive more self-serving behavior of others, they will not be motivated for organizational citizenship behavior. This study supports the findings of previous research (e.g. Khan et al., Citation2019; Tripathi et al., Citation2023). When employees perceive that organizational politics are prevalent in their workplace, they may become disengaged and less committed to the organization (Karatepe, Citation2013). This can lead to a decline in organizational citizenship behavior, as employees may be less willing to go beyond their job to help others or advance the goals of the organization (Tripathi et al., Citation2023). (Politics in organization can foster a competitive atmosphere where workers are more concerned with accomplishing their personal objectives than with assisting their coworkers or the organization as a whole (Khan et al., Citation2019). As a result, employee willingness to help others and work together on tasks might have a negative impact on organizational citizenship behavior (Karatepe, Citation2013; Tripathi et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, employees who experience organizational politics may cultivate suspicious of their leaders and peers (Randall et al., Citation1999). As a result, employees may become less inclined to take engage in building relationships with others, which might result in a decline in organizational citizenship behavior. Generally, organizational politics have a negative effect on organizational citizenship behavior by creating a disengaged work environment, creating distrust, and promoting a culture of fear (Khan et al., Citation2019). Organizational politics are a distraction for public service organizations, so in order to promote organizational citizenship behavior, organizations should work to minimize organizational politics and create a supportive and collaborative work environment.

The final stage was examining the mediating role of perceptions of organizational politics between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior. The study found that the effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior has not only direct effect but also an additional mediating effect. In present study, perceptions of organizational politics is negatively (competitively) partial mediated the effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior. This means that servant leaders have the ability to decrease the perception of politics by placing emphasis on their employees treating with fairness and ethics (Khattak et al., Citation2022). When employees perceive their work environment as less political it increases the likelihood of them actively participating in organizational citizenship behavior (Islam et al., Citation2013; Kacmar et al., Citation2013; Vigoda-Gadot, Citation2007). In contrast when employees perceive their work environment as political, they may feel that their leaders are more concerned with their own interests rather than the interests of their employees and result lower levels of organizational citizenship behavior. The finding of the study supports previous studies conducted by Ehrhart (Citation2004) and Qiu and Dooley (Citation2022), who claimed that there is a mediated rather than direct link between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior. However, Ehrhart (Citation2004) and Qiu and Dooley (Citation2022) suggested organizational justice as a mediator in this link, and the present study emphases on organizational politics as playing a similar role. In relation to this, scholars have claimed that, though organizational politics and organizational justice are distinct concepts, they are similar since they both aim to represent how employees view fairness and justice in the workplace (Andrews & Kacmar, Citation2001; Byrne, Citation2005; Kaya et al., Citation2016; Mathur et al., Citation2013; Vigoda-Gadot, Citation2007). Organizational politics refer to the use of power to achieve personal goals rather than organizational goals (Vigoda & Cohen, Citation2002). Employees who perceive high levels of organizational politics may believe that decisions are being made based on personal interests or favoritism, rather than objective criteria (Vigoda-Gadot, Citation2007). This can lead to a sense of unfairness or injustice among employees who feel that they are being treated unfairly or that their contributions are not recognized or valued (Hochwarter et al., Citation2020; Kaya et al., Citation2016). Similarly, organizational justice refers to employees’ beliefs about the fairness of the procedures and outcomes in the workplace (Ehrhart, Citation2004). Employees who perceive high levels of organizational justice believe that decisions are being made fairly and that they are being treated equitably. This can lead to a sense of fairness and justice among employees who feel that they are being treated fairly and that their contributions are being recognized and valued (Byrne, Citation2005; Mathur et al., Citation2013). For this reason, scholars have argued that the ideas of organizational politics and organizational justice are similar since they both aim to represent how employees perceive fairness and justice at work.

The study finding is also much in line with the same idea previously suggested by Ferris and Rowland (Citation1981) who claimed that perceptions of the workplace mediate between leadership and organizational citizenship behavior. Ferris and Rowland (Citation1981) discussed that employees who have positive perceptions of their workplace tend to be more engaged and productive, while those with negative perceptions may experience lower performance. On the other hand, leaders who are perceived as unfair, unsupportive, or untrustworthy may contribute to negative perceptions and lower performance (Ferris & Rowland, Citation1981). According to Saleem (Citation2015), the significant mediating effect of organizational politics indicates that an effective leader will not only assist the organization in achieving its aims but will also be responsible for creating a fair, just, and healthy environment that meets the needs and expectations of the employees. Overall, the results of the study explain and confirmed public sector major issue i.e. servant leadership helps to improve employees organizational citizenship behavior. Apart from improving organizational citizenship behavior, these styles also help to reduce perception of organizational politics which in most scenarios exert negative impact and damage relationships among key variables.

7. Conclusion

The study examined to show empirical evidence of how servant leadership could positively affect organizational citizenship behavior but also minimize the negativity of political perceptions in Ethiopian federal public service organizations. The results of the correlation for servant leadership, organizational citizenship behavior and perceptions of organizational politics showed strong relationships. This implies that servant leadership, organizational citizenship behavior and perceptions of organizational politics share many attributes in common and an increase in performance of one of them may add values for increment of another. The study also showed that the direct effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior was positive and significant. The effect of servant leadership on perceptions of organizational politics was also negative and significant. Moreover, the effect of organizational citizenship behavior on perceptions of organizational politics was negative and significant. As a final point, perceptions of organizational politics negatively mediated the servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior link. This finding suggests that public sector leaders apply servant leadership in their day-to-day leadership practices helps to advance employee’s organizational citizenship behavior by reducing perceptions of politics. Overall, this study offered theoretical and empirical support for perceptions of organizational politics as a mediator of the servant leadership–organizational citizenship behavior links. To this end, the study concluded when Ethiopia public service organizations policy advocates wish to provoke the citizenship behaviors of the employees, then, they should be concerned about servant leadership who are employed in these institutions. By focusing on servant leaders, public service organizations can make improvements in important outcomes that benefit the organization. The contribution of such practices is vital in improving organizational effectiveness.

8. Implications

8.1. Theoretical implications

This study contributes to the literature on perceived organizational politics by demonstrating its mediating role in the relationship between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior. Previous studies have shown the links between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior, but, to the best knowledge of the current researcher, no study so far has been done about the mediation mechanisms of perceptions of organizational politics. This is the first study conducted on servant leadership and its effect on organizational citizenship behavior through the mediating effect of perceptions of organizational politics using Ethiopian public service organizations, and it found that perceptions of organizational politics are one mechanism to explain the effects of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior. Therefore, it may help enhance the body of knowledge or literature with regard to the practices and interactions between servant leadership, perceptions of organizational politics, and organizational citizenship behavior in public service organizations in different contexts.

8.2. Practical implications

The following actions may be taken by public service organizations to encourage organizational citizenship behavior and enhance organizational effectiveness: The first is that servant leadership should be implemented by public service organizations. Leaders may act as role models for their employees by prioritizing the needs of their workers and exhibiting traits like empowerment, humility, and empathy. Secondly, public service organizations should encourage an environment of fairness. By promoting transparency in decision-making processes and ensuring equitable allocation of opportunities and resources, they may mitigate the appearance of organizational politics. Thirdly, establishment of systems to recognize and reward organizational citizenship activity is necessary for public service organizations. Rewarding employees who consistently exhibit these behaviors is a good way to motivate them to take part in organizational citizenship.

9. Limitations and future research

Despite all the contributions and implications made by the research highlighted above, it also has some limitations. The first is the generalizability of the results; although the researcher tried to capture the maximum number of federal public service organizations operating in Ethiopia, only six were selected. Therefore, in the future, this research can be conducted at all federal public service organizations. Second, this research can be conducted in the future by private organizations as well. Third, the study used cross-sectional research methods to examine the actions of selected variables; hence, researchers could have carried out longitudinal research and come to different conclusions. Fourth, the current researcher collected data for the predictors and criterion variables from one source. The use of only self-reported measures is vulnerable to the social desirability effect and the influence of common method variance, which may inflate the responses of the participants. A supervisor-rated organizational citizenship behavior in future exploration of these variables may reflect a picture of relationship patterns with more precision. Therefore, future researchers should collect data from different sources.

Ethical consideration

The author obtained respondent consent before collecting the data.

Tables1 Cogent.docx

Download MS Word (46.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data will be presented upon request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Addisu Debalkie Demissie

Addisu Debalkie Demissie has been served in leadership positions in various public sectors, including Head of Industry and Investment Department, Head of Trade and Market Development Department, and Head of Civil Service and HRM Department at Gondar City Administration. Currently, he is a PhD candidate in College of Business and Economics, Department of Management, University of Gondar. He obtained his MA and BA degrees from University of Gondar and Mekelle University, respectively. His research areas include strategic management, strategic leadership and organizational behavior.

Abebe Ejigu Alemu

Abebe Ejigu Alemu is logistics management professor in the Department of Logistics Management, International Maritime College Oman; Professor of Marketing and Supply Chain Management, School of Management, Mekelle University. He has contributed countless research publications presented in international and national journals; presenting several papers in international and national conferences and workshops.

Assefa Tsegay Tensay

Assefa Tsegay Tensay is associate professor management in the College of Business and Economics, Department of Management, University of Gondar. He has contributed several research publications, and he does research in strategic human resource management, organizational behavior and leadership.

References

- Al Jisr, S., Beydoun, A. R., & Mostapha, N. (2020). A model of perceptions of politics: Antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Management Development, 39(9/10), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-12-2019-0503

- Amir, D. A. (2019). The effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior: The role of trust in leader as a mediation and perceived organizational support as a moderation. Journal of Leadership in Organizations, 1(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.22146/jlo.42946

- Andrews, M. C., & Kacmar, K. M. (2001). Discriminating among organizational politics, justice, and support. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(4), 347–366. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.92

- Atta, M., & Muhammad, J. K. (2016). Perceived organizational politics, organizational citizenship behavior and job attitudes among university teachers. Journal of Behavioural Sciences, 26(2), 21–38.

- Aziz, K., Awais, M., Hasnain, S. S. U., Khalid, U., & Shahzadi, I. (2018). Do good and have good: Does servant leadership influence organizational citizenship behavior? International Journal of Scientific and Technology Research, 7(4), 7–16.

- Bambale, A. J., Shamsudin, F. M., & Subramaniam, C. a (2015). Effects of servant leader behaviors on Organizational Citizenship Behaviors for the Individual (OCB-I) in the Nigeria’s utility industry using Partial Least Squares (PLS). International Journal of Management and Sustainability, 4(6), 130–144. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.11/2015.4.6./11.6.130.144

- Barnard, C. I. (1938). The functions of the executive. (Vol. 11). Harvard university press.

- Bowman, R. F. (2005). Teacher as servant leader. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 78(6), 257–260. https://doi.org/10.3200/TCHS.78.6.257-260

- Brubaker, T. A., Bocarnea, M. C., Patterson, K., & Winston, B. E. (2015). Servant leadership and organizational citizenship in Rwanda: A moderated mediation model mission pour la Nouvelle Créature. Servant Leadership: Theory and Practice, 2(2), 27–56.

- Byrne, Z. S. (2005). Fairness reduces the negative effects of organizational politics on turnover intentions, citizenship behavior and job performance. Journal of Business and Psychology, 20(2), 175–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-005-8258-0

- Chang, W., J, Hu, D., C, & Keliw, P. (2021). Organizational culture, organizational citizenship behavior, knowledge sharing and innovation: A study of indigenous people production organizations. Journal of Knowledge Management, 25(9), 2274–2292. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-06-2020-0482

- Cheng, J., Bai, H., & Yang, X. (2019). Ethical leadership and internal whistleblowing: A mediated moderation model. Journal of Business Ethics, 155(1), 115–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3517-3

- Collier, J. E. (2020). Applied structural equation modeling using AMOS. Applied Structural Equation Modeling Using AMOS. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003018414

- Crawford, W. S., Lamarre, E., Kacmar, K. M., & Harris, K. J. (2019). Organizational politics and deviance: Exploring the role of political skill. Human Performance, 32(2), 92–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2019.1597100

- Cropanzano, R., Howes, J. C., Grandey, A. A., & Toth, P. (1997). The relationship of organizational politics and support to work behaviors, attitudes, and stress. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 18(2), 159-180. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199703)18:2<159::AID-JOB795>3.0.CO;2-D

- Dannhauser, Z. (2007). The relationship between servant leadership, follower trust, team commitment and unit effectiveness. [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Stellenbosch.

- Dash, S., & Pradhan, R. K. (2014). Determinants and consequences of Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A theoretical framework for Indian manufacturing organisations. International Journal of Business and Management Invention, 3(1), 17–27. http://www.ijbmi.org/papers/Vol(3)1/Version-1/C03101017027.pdf

- de Geus, C. J. C., Ingrams, A., Tummers, L., & Pandey, S. K. (2020). Organizational citizenship behavior in the public sector: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Public Administration Review, 80(2), 259–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13141

- Denhardt, R. B., & Denhardt, J. V. (2000). The new public service: Serving rather than steering. Public Administration Review, 60(6), 549–559. https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-3352.00117

- Dittmar, J. K. (2006). An interview with Larry Spears. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 13(1), 108–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/10717919070130010101

- Ehrhart, M. G. (2004). Leadership and procedural justice climate as antecedents of unit-level organizational citizenship behavior. Personnel Psychology, 57(1), 61–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2004.tb02484.x

- Elche, D., Ruiz-Palomino, P., & Linuesa-Langreo, J. (2020). Servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating effect of empathy and service climate. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(6), 2035–2053. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-05-2019-0501

- Eva, N., Robin, M., Sendjaya, S., van Dierendonck, D., & Liden, R. C. (2019). Servant leadership: A systematic review and call for future research. The Leadership Quarterly, 30(1), 111–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.07.004

- Farling, M. L., Stone, A. G., & Winston, B. E. (1999). Servant leadership: Setting the stage for empirical research. Journal of Leadership Studies, 6(1-2), 49–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/107179199900600104

- Ferris, G. R., & Rowland, K. M. (1981). Leardership, job perceptions, and influence: A conceptual integration. Human Relations, 34(12), 1069–1077. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872678103401204

- Ferris, G. R., Treadway, D. C., Perrewé, P. L., Brouer, R. L., Douglas, C., & Lux, S. (2007). Political skill in organizations. Journal of Management, 33(3), 290–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307300813

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Gandz, J., & Murray, V. V. (1980). The experience of workplace politics. Academy of Management Journal, 23(2), 237–251. https://doi.org/10.2307/255429

- Gnankob, R. I., Ansong, A., & Issau, K. (2022). Servant leadership and organisational citizenship behaviour: the role of public service motivation and length of time spent with the leader. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 35(2), 236–253. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-04-2021-0108

- Graham, J. W. (1991). Servant-leadership in organizations: Inspirational and moral. The Leadership Quarterly, 2(2), 105–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/1048-9843(91)90025-W

- Grawitch, M. J., Gottschalk, M., & Munz, D. C. (2006). The path to a healthy workplace: A critical review linking healthy workplace practices, employee well-being, and organizational improvements. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 58(3), 129. https://doi.org/10.1037/1065-9293.58.3.129

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 414–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0261-6

- Hameed Al-Ali, A., Khalid Qalaja, L., & Abu-Rumman, A. (2019). Justice in organizations and its impact on organizational citizenship behaviors: A multidimensional approach. Cogent Business & Management, 6(1) https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2019.1698792

- Hanaysha, J. R., Kumar, V. V A., In’airat, M., & Paramaiah, C. (2022). Direct and indirect effects of servant and ethical leadership styles on employee creativity: Mediating role of organizational citizenship behavior. Arab Gulf Journal of Scientific Research, 40(1), 79–98. https://doi.org/10.1108/AGJSR-04-2022-0033

- Harwiki, W. (2013). The influence of servant leadership on organization culture, organizational commitment, organizational citizenship behavior and Employeesâ€TM Performance (Study of outstanding cooperatives in East Java Province, Indonesia). Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies, 5(12), 876–885. https://doi.org/10.22610/jebs.v5i12.460

- Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2014.962683

- Hochwarter, W. A. (2012). The positive side of organizational politics. Politics in organizations: Theory and research considerations (pp. 27–65). Routledge.

- Hochwarter, W. A., Kacmar, C., Perrewé, P. L., & Johnson, D. (2003). Perceived organizational support as a mediator of the relationship between politics perceptions and work outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 63(3), 438–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00048-9