?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examines the relationship between corporate governance (CG), family ownership, and corporate performance in firms listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange (IDX). This research investigates whether CG practices influence both market-based performance (measured by Tobin’s Q) and accounting-based performance (measured by Return on Assets, ROA). We further investigate the moderating role of family ownership in this relationship. Our panel data analysis covers the period from 2014 to 2020, including firms from primary and secondary industries. The findings reveal a significantly positive association between CG implementation and corporate performance, indicating that good CG mechanisms enhance a firm’s market and accounting performance. However, family ownership weakens this relationship with market performance but has no significant impact on accounting performance. Family-controlled firms tend to exhibit weaker corporate governance practices and may undermine investor confidence, potentially leading to lower stock prices.

1. Introduction

Family firms are pivotal in global economies, contributing significantly to industrialization and economic growth (Cordeiro et al., Citation2018; Ho et al., Citation2020; Singla, Citation2020; Siregar & Utama, Citation2008). A family firm is a company founded, and its key activities are held by the family (del Carmen Briano-Turrent & Poletti-Hughes, Citation2017; Lee & Chu, Citation2017; Yeon et al., Citation2021). These firms often exert control through direct ownership or indirect mechanisms such as pyramid structures (Anderson & Reeb, Citation2003; Claessens et al., Citation2008; Li et al., Citation2016). Remarkably, even in the United States, approximately one-third of firms listed on the S&P 500 are family-owned (Yeon et al., Citation2021). Their economic significance is undeniable, with Chau and Leung (Citation2006) revealing that family firms on stock exchanges contribute around 62% of the United States gross domestic product (GDP).

In East Asian countries, family firms dominate the corporate landscapes (Li et al., Citation2016). Approximately two-thirds of the public firms in these regions exhibit concentrated family ownership. Furthermore, approximately 60% of these firms have top managers with familial ties to their shareholders. Family firms often exhibit greater stability and resilience than non-family firms, contributing significantly to GDP and serving as major employers worldwide (Marques et al., Citation2014). The Indonesian context exemplifies the positive impact of family firms on the national economy. Family firms in Indonesia contribute substantially 25% to the country’s GDP and are the largest employment providers. In 2014, family firms dominated the manufacturing sector on the Indonesia Stock Exchange, accounting for 50% of the sector’s profits (Pricewaterhouse Coopers (PwC), Citation2014).

In family firms, firm management primarily consists of family members, also shareholders. This arrangement positively impacts the firm, reducing relatively expensive agency costs and alleviating classic Type I agency conflicts (Saito, Citation2008). Consequently, this positively affects a firm’s share price, which tends to be higher than that of other firms (Badrul Muttakin et al., Citation2014; Ciftci et al., Citation2019; Manogna, Citation2021; Morck & Yeung, Citation2004). However, Jaggi and Leung (Citation2007) and Castillo-Merino and Rodríguez-Pérez (Citation2021) have reported negative stock market reactions to appointing family members in managerial roles in family firms. This indicates that, despite concentrated ownership, implementing CG mechanisms is crucial for ensuring sustained firm performance. Numerous studies have established a strong correlation between robust corporate performance and effective corporate governance (Beasley et al., Citation2009; Chow, Citation2021; Kyere & Ausloos, Citation2020; Wahyudin & Solikhah, Citation2017).

The study employs panel data regression with a generalized least squares (GLS) estimator, controlling for endogeneity through the general method of moments (GMM). Two regression models were used to analyze the effects of CG on corporate performance and the moderating role of family ownership. This research methodology facilitates a robust examination of the research questions and provides valuable insights into the complex relationship between CG, family ownership, and firm performance in the Indonesian context. The sample comprises firms listed on the Indonesian Stock Exchange (IDX) from 2014 to 2020. The selection of IDX is due to the dominance of family companies in publicly listed manufacturing companies, which is almost 50% (Pricewaterhouse Coopers (PwC), Citation2014). Corporate performance was evaluated from accounting-(ROA) and market stock-based (utilizing Tobin’s Q) perspectives. CG was measured using ASC, a comprehensive tool based on Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) principles that offers a nuanced assessment of governance quality. Family firms were identified using a binary approach based on ownership stakes held by family members. This study finds that CG significantly enhances corporate performance. Additionally, family ownership weakens this relationship with market performance, albeit without significantly affecting accounting performance. This finding suggests that family-controlled firms may exhibit less stringent corporate governance practices, potentially eroding investor confidence and negatively influencing stock prices.

This study makes several significant contributions to the literature. First, it advances our understanding of corporate governance in the context of family-owned firms in Indonesia. Examining how CG practices influence the performance of these businesses offers valuable insight into the nuanced dynamics of governance in family firms. Second, the finding has important practical implications for policymakers and regulatory authorities in Indonesia. Identifying family ownership as a moderating factor in the CG-performance relationship underscores the importance of tailoring governance policies to suit the unique characteristics of family firms. This study also contributes methodologically by employing robust analytical methods, including panel data regression, controlling the endogeneity issue, and using the ASC to measure CG.

Further, this study enriches the literature on corporate governance, particularly in the context of family firms, and offers practical guidance for policymakers and regulators. Finally, this study has practical implications for strengthening CG practices within family-owned firms. This reveals that family members’ interventions in a firm’s CG procedures have a detrimental impact. This highlights the importance of ensuring the complete independence of supervisory mechanisms, such as independent commissioners and audit committees, from majority shareholders’ interests. When these oversight roles are filled based on their proximity to majority shareholders rather than impartiality, their effectiveness in safeguarding minority shareholders’ interests diminishes.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides an overview of the pertinent literature and the evolution of the hypotheses. Section 3 outlines the data and research methodology. Section 4 presents the conclusions of the study. The concluding section summarises the findings and proposes potential paths for future research.

2. Literature review and hypotheses development

2.1. Fundamental theories

In corporate governance, two foundational theories–agency theory and signal theory–offer valuable perspectives for understanding the dynamics between corporate governance practices, family ownership, and corporate performance. Agency theory posits that the separation of ownership (principal) from management (agent) can lead to conflicts of interest (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). This separation may induce managers to act in ways that prioritize their self-interest to maximize shareholder wealth (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976; Said et al., Citation2017; Wahyudin & Solikhah, Citation2017; Worokinasih & Zaini, Citation2020). The divergence of interests between shareholders and managers can result in agency conflicts, whereby managers pursue personal gains at the shareholders’ expense. These conflicts become particularly salient in firms with concentrated ownership structures, such as family-owned firms. Here, agency theory distinguishes between Type I agency conflicts, characterized by conflicts between shareholders and managers, and Type II agency conflicts, which manifest as conflicts between the majority and minority shareholders (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976).

Signaling theory, initially proposed by Spence (Citation1973), provides another lens through which to view corporate governance dynamics. This theory underscores the importance of information-sharing within a firm. Specifically, it suggests that firms communicate vital information about their financial health, prospects, and governance practices to investors and other stakeholders through signals (Casado-Díaz et al., Citation2014; Chau & Gray, Citation2010; Devie et al., Citation2020; Kim et al., Citation2021; Muttakin et al., Citation2015; Nguyen & Trinh, Citation2020; Prado-Lorenzo et al., Citation2009). Signals can be pivotal in influencing investor perceptions and behaviors in family firms. For instance, when family firms disclose sustainability reports or implement robust governance practices, they send signals to the market regarding their commitment to transparency and sound governance. These signals, in turn, may attract investors who perceive family firms as reliable and capable of maximizing their shareholder value. Signal theory, therefore, emphasizes the role of information disclosure in shaping stakeholder perceptions and firm performance (Spence, Citation1973).

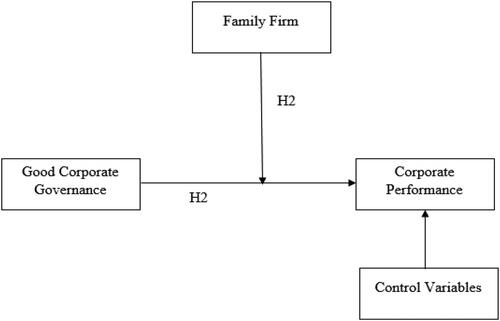

The combination of agency and signal theories provides a comprehensive framework for analyzing the intricate relationships between corporate governance, family ownership, and corporate performance (). By understanding the dynamics of agency conflicts and the power of signals, researchers and practitioners can gain deeper insights into how corporate governance mechanisms such as CG impact firms, especially those with family ownership. This theoretical foundation forms the basis for our investigation of the moderating effect of family ownership on the relationship between CG practices and corporate performance within the Indonesian context. (Aldhamari et al., Citation2020; Devie et al., Citation2020; Musallam, Citation2018; Rodriguez-Fernandez, Citation2016; Worokinasih & Zaini, Citation2020).

2.2. Corporate governance and corporate performance

Corporate performance, which indicates a firm’s operational efficiency and effectiveness (Chauhan et al., Citation2016; Mahrani & Soewarno, Citation2018; Mishra & Kapil, Citation2017), is pivotal for achieving set goals and maintaining market stability. Investors gravitate towards firms with stable stock prices because these reflect resilience in the face of market fluctuations (Nawawi et al., Citation2020). Therefore, ensuring consistent and robust performance is critical for businesses.

CG has emerged as a pivotal driver of robust performance within firms (Mahrani & Soewarno, Citation2018; Nawawi et al., Citation2020; Suhadak et al., Citation2019; Tjahjadi et al., Citation2021). CG is a vital mechanism to ensure that firms operate effectively and efficiently by mitigating the consequences of information asymmetry, which is a primary source of conflicts of interest. In agency theory, these conflicts manifest as two distinct types: Type I conflicts, characterized by disputes between management (agents) and owners (principals), and Type II conflicts, involving majority and minority shareholders. These conflicts are often rooted in disparities in information accessibility between these parties, with the strategic use of information being a potential advantage (Said et al., Citation2017; Wahyudin & Solikhah, Citation2017; Xue et al., Citation2020). When these conflicts arise between agents and principals or among majority and minority shareholders, they can severely disrupt a firm’s operations and derail its performance objectives (El Diri et al., Citation2020; Imamah et al., Citation2019). Hence, it is imperative to establish effective mechanisms for managing these conflicts. Through CG, a system of checks and balances is instituted internally within the firm’s components and externally between agents and principals (Kyere & Ausloos, Citation2020; Wahyudin & Solikhah, Citation2017). This reinforces a firm’s monitoring system, resulting in improved corporate performance. Consequently, it can be deduced that CG fosters an environment conducive to achieving and maintaining high levels of corporate performance. This is primarily attributable to the CG's capacity to quell conflicts of interest among principals and agents, as well as between majority and minority shareholders, while concurrently optimizing the efficiency and effectiveness of a firm’s operations.

From the above arguments, we tested the following hypothesis:

H1:

CG has a positive effect on corporate performance

2.3. The moderating effect of family firm

Extensive prior research has consistently highlighted the positive impact of CG on a firm’s overall performance (Aluchna et al., Citation2020; Chakroun et al., Citation2020; Chow, Citation2021; Gambo et al., Citation2019; Rodriguez-Fernandez, Citation2016). Implementing robust CG practices is a potent mechanism to bridge the information gap that typically separates management from capital providers, fostering heightened corporate performance (Chow, Citation2021; Lawal, Citation2011; Mishra & Kapil, Citation2017; Zaid et al., Citation2020). CG principles inherently encompass transparency and accountability standards, ensuring stakeholders have unfettered access to critical information. Nevertheless, it is essential to recognize that the influence of CG frameworks may not be uniform across all firms, particularly those characterized by concentrated shareholdings, such as family firms.

Family firms, defined as the level of share ownership maintained by the founding family, often perpetuate ownership. However, they are not without challenges, including potential conflicts, particularly between the majority and minority shareholders (Chiu et al., Citation2021; González et al., Citation2019; Ho et al., Citation2020; Kao et al., Citation2019; Saito, Citation2008). This struggle falls under Type II conflict within agency conflict theory. In family firms, the conflict between management (agents) and ownership (principals) tends to be mitigated by the representation of shareholder members in the firm’s management. It is important to acknowledge that majority shareholders, who can influence crucial decisions, may use their power to benefit themselves at the expense of minority shareholders, as suggested by previous studies (Ho et al., Citation2020; Kao et al., Citation2019; Saito, Citation2008).

Remarkably, more than 50% of firms in Indonesia are family-dominated in ownership structure, according to Siregar and Utama (Citation2008). This fact is supported by the PwC (Citation2014) survey in 2014, revealing that 50% of firms in the manufacturing sector are family firms. This underscores the potential for conflict, especially between majority and minority shareholders, necessitating effective CG mechanisms within these family-centric firms. Often holding a majority shareholder position, the family can significantly influence management policies. Family members frequently assume pivotal roles on the board of directors, such as CEOs and CFOs, presenting ample opportunities for expropriation by majority shareholders (Agrawal & Chadha, Citation2005; Aldamen et al., Citation2020; Chiu et al., Citation2021; Ho et al., Citation2020).

Neffe et al. (Citation2022) argue that familial altruism may lead to excessive family involvement, which can, paradoxically, be detrimental to the firm. The heavy involvement of family members can erode trust among shareholders, with concerns that the management might not prioritize the firm’s best interests and could potentially exploit the rights of minority shareholders (Agrawal & Chadha, Citation2005; Ciftci et al., Citation2019; Cordeiro et al., Citation2018; González et al., Citation2019). In this context, the CG mechanism is pivotal in curtailing opportunities for expropriation by majority shareholders through rigorous oversight of board policies and activities. Independent commissioners and audit committees serve as a bulwark against impropriety, allowing minority shareholders to exercise their right to access accurate information about a firm’s affairs (Rose, Citation2016; Rubino & Vitolla, Citation2014; Schäuble, Citation2019). However, it’s important to note that the appointment of independent board members should extend beyond mere compliance with regulations, ideally striving to enhance overall corporate performance (Burak et al., Citation2016; Chatterjee & Rakshit, Citation2020; Masmoudi Mardessi & Makni Fourati, Citation2020; Siregar & Utama, Citation2008). Conversely, elected board members often lack complete independence, and many maintain personal or business ties with the firm’s owner (Al-Absy et al., Citation2019). Based on this explanation, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2:

Family firm weakens the positive relationship of CG to corporate performance

3. Research methods

3.1. Data and sample

We select our sample from firms listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange (IDX) operating in both primary industries (such as agriculture and mining sectors) and secondary industries (including basic and chemical industry sectors, consumer goods sector, and other industries) for the observation period spanning from 2014 to 2020. The year 2014 was chosen as the initial year of observation in the study because a sustainability report was introduced in that year, which contained information on the company’s sustainability activities from the economic, social, and environmental segments. Sustainability reports published by listed companies in 2014 used GRI-4, which was later changed to GRI Standard. The observation period interval from 2014 to 2020 is expected to show a more consistent interaction trend between variables. A rigorous data screening and verification process was conducted to ensure the quality and completeness of the data, as presented in .

Table 1. Number of sample and research observations.

3.2. Variables definition and measurement

We measure the dependent variable, corporate performance, from two primary perspectives: accounting and market stock-based measurements. Accounting-based performance is quantified using return on assets (ROA), a reliable metric that significantly influences stakeholder assessments of corporate performance and decision-making (Dey, Citation2008; Purbawangsa et al., Citation2020). Additionally, consistent with previous research (Farooq et al., Citation2022; Gambo et al., Citation2019; Mishra & Kapil, Citation2017; Rose, Citation2016), we use Tobin’s Q. as proxy for market stock-based measurements. Meanwhile, for the robustness test, Accounting-based performance is quantified using return on equity by earning before interest & tax (ROEEBIT), and market stock-based measurements use market-to-book ratio (MBR) ().

Table 2. Definition and measurment of variables.

For the independent variable, CG, We measure using the ASC. It is a comprehensive and efficient instrument drawn from corporate annual reports, as Utama et al. (Citation2017) used. Developed based on OECD principles, ASC encompasses two levels of assessment: Level 1 consists of five main sections, each containing 179 items as guidelines, while Level 2 includes bonus and penalty components, with a composition of 11 bonus items and 21 penalty items. Bonus items provide additional points for exemplary governance practices, whereas penalty items deduct points for poor governance practices. The total Level 2 score is calculated by combining bonus and penalty scores (Utama et al., Citation2017). ASC offers a structured and detailed framework for evaluating CG, making it a suitable measurement tool for this research (Utama et al., Citation2017). It provides a comprehensive assessment of corporate governance practices by considering various dimensions and aspects, thus allowing for a comprehensive understanding of the quality of governance within each firm.

In this study, the moderating variable, a family firm is defined as a firm in which key activities and ownership stakes are held by family members (del Carmen Briano-Turrent & Poletti-Hughes, Citation2017; Lee & Chu, Citation2017; Yeon et al., Citation2021). The measurement of the family firm status followed the criteria established Chi et al. (Citation2015) and del Carmen Briano-Turrent and Poletti-Hughes (Citation2017), which employs a binary approach. Specifically, a dummy variable is assigned a value of 1 when the largest shareholder holds at least a 20% ownership stake as an individual; otherwise, it is assigned a value of 0. This binary measurement effectively distinguishes between family-owned and non-family-owned firms in the sample, allowing for the analysis of how family ownership moderates the relationship between CG practices and corporate performance outcomes.

This research includes various control variables used in previous studies, such as Cornett et al. (Citation2008) and Wahyudin and Solikhah (Citation2017): size, leverage, age of the firm, and regulation (Beasley et al., Citation2009; Gambo et al., Citation2019; González et al., Citation2019; Hoseini et al., Citation2019; Saito, Citation2008).

3.3. Regression model

This study uses panel data regression with a generalized least squares (GLS) estimator. Furthermore, it uses the generalized method of moments (GMM) to control for endogeneity (Ibrahim et al., Citation2020; Lin et al., Citation2020; Naciti, Citation2019; Pareek & Sahu, Citation2022). Model 1 is used to analyze the effect of CG on firm performance. In contrast, Model 2 is used to analyze the moderating effect of family ownership on the relationship between CG and corporate performance.

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

where FP is corporate performance; CG is the CG disclosure index; FF is Family firm; SIZE is the natural logarithm of total assets of the firm; LEV is the ratio of total debt divided by total assets equity; AGE is the number of years since incorporation; and REG is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if there are strict regulations in the environmental sector firm, and 0 otherwise.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Descriptive statistics

presents the descriptive statistics of all variables used in this research. The mean TBQ value during the observation period is 1.01, indicating that the market capitalization value is 1.01% of the firm’s total assets. This positive trend was caused by the condition of the Indonesian economy, which improved after being affected by the crisis in 2008. Legal and political stability have contributed to improved stock market capitalization in Indonesia. For the accounting performance measure, the mean value of ROA is 0.034, meaning that during the observation period, the profit earned by the firm is only 3.4% of the average total assets.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics.

Meanwhile, the mean value of family ownership is 0.236, meaning that only approximately 23.6% of the total observations are family firms. On average, firms exhibit relatively weak corporate governance practices, as indicated by a mean CG score of approximately 39.38. Our sample comprises firms with a wide range of total assets (SIZE), ranging from 18.67 to 25.82, demonstrating significant variation in their financial scales. Capital structure (LEV) also exhibits diversity, with a standard deviation of 2.162, indicating variations in debt-equity ratios among firms. Additionally, firm age (AGE) ranges from 6 to 119 years, underlining the heterogeneous nature of our dataset. Furthermore, environmental regulation exposure (REG) varies, with approximately 24.9% of firms operating under strict environmental regulations.

We also perform a pairwise correlation test for variables. As reported in , the results show that the correlation coefficient of CG disclosure (CG) on the four corporate performance variable measurements is 0.169 for MBR, 0.243 for TBQ, 0.210 for ROA, and 0.163 for ROE. Notably, a strong positive correlation exists between Tobin’s Q (TBQ) and Market-Based ROE (ROEEBIT) at 0.800, indicating that firms with higher market performance tend to have better market-based returns on equity. Additionally, the correlation between Return on Assets (ROA) and TBQ is positive and significant at 0.514, suggesting that firms with higher accounting-based performance (ROA) often exhibit superior market performance. This correlation aligns with the expected relationship between market and financial performance.

Table 4. Pearson correlation test.

Conversely, Family Firm (FF) ownership shows a negative correlation with TBQ at -0.120, indicating that family-owned firms may face challenges in achieving strong market performance. To conclude, we find significant correlations among independent variables, but not excessively high (below 0.800), suggesting no severe collinearity problem among the independent variables. This conclusion is supported by the opinion of Gujarati (Citation1995), who states that multicollinearity tends to be a concern when the pairwise correlation between two variables exceeds 0.80.

4.2 Main findings

presents the regression estimates used to test the hypotheses. Columns (1)–(3) analyze market performance (TBQ) with varying levels of CG and the moderating effects of family forms. Columns (4)–(6) investigate accounting performance (ROA) using similar variables. All columns include control variables and fixed effects of industry and year.

Table 5. Main results.

The findings reveal a robust and positive association between CG and TBQ across different models (columns (1) to (3)). CG consistently exhibits a highly significant positive effect on TBQ at the 1% significance level, implying that firms with stronger corporate governance practices tend to command higher market valuations. This result supports H1. In addition, these results align with the findings of several previous studies (Mahrani & Soewarno, Citation2018; Nawawi et al., Citation2020; Suhadak et al., Citation2019; Tjahjadi et al., Citation2021). Interestingly, the interaction term CG*FF, although significant at the 10% level in Column (2), suggests that family firms may influence the relationship between CG and TBQ. Family firms also have a significantly positive coefficient, implying a positive impact in shaping market performance. This result supports H2. In addition, these results align with the findings of several previous studies (Agrawal & Chadha, Citation2005; Ciftci et al., Citation2019; Cordeiro et al., Citation2018; González et al., Citation2019).

CG is an essential factor influencing the performance of family firms. The rules, procedures, and systems that govern a firm have significant implications for its performance (Harkin et al., Citation2020). Agency theory points to conflicts of interest arising from information asymmetry between agents and principals in firms (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). Type I agency conflicts can be mitigated in firms with concentrated ownership, such as family firms because larger shareholders have incentives to monitor managers (Ho et al., Citation2020). However, family-owned firms often grapple with Type II agency conflicts, characterized by conflicts between majority and minority shareholders. The controlling position of most shareholders in such firms can be exploited for personal gain at the expense of minority shareholders (Saito, Citation2008).

For ROA, the results presented in columns (4)–(6) show positive coefficients for CG at the 1% level, suggesting a consistently strong and positive influence on ROA. This finding implies that firms with superior corporate governance structures tend to achieve higher profitability. Unlike TBQ, the interaction term CG*FF does not significantly affect ROA in any model, emphasizing that family firms may not significantly impact profitability similarly to market valuation. These results suggest stronger corporate governance practices are associated with higher market valuations (TBQ) and enhanced profitability (ROA). However, the interaction between corporate governance and family firms, while noteworthy in the context of TBQ, does not seem to play a substantial role in the ROA.

4.3. Robustness analyses

4.3.1. Alternative measurements for firm performance

presents the additional analysis results employing alternative measurements for firm performance. This section focuses on the effects of corporate governance (CG), family firm (FF), and their interaction (CG*FF) on two distinct measures of firm performance: Market-to-Book Ratio (MBR) and Return on Equity (ROE).

Table 6. Alternative measurements for firm performance.

For the Market-to-Book Ratio (MBR), we find across columns (1) to (3) that CG exhibits a strong and statistically significant positive influence on MBR at the 1% significance level. This suggests that firms with robust corporate governance practices tend to have higher market valuations than their book values. Additionally, the interaction term CG*FF shows significance at the 10% level in Column (3). This implies that the presence of family firms within the corporate structure may modulate the relationship between corporate governance and MBR. However, the effect is relatively weaker than CG's direct impact of CG. In the context of this analysis, family firms may either enhance or attenuate the positive impact of corporate governance on MBR, depending on specific circumstances.

Columns (4)–(6) show that CG has significantly positive coefficients, indicating that firms with effective corporate governance structures tend to generate higher returns on equity. However, the interaction term CG*FF does not appear to significantly affect ROE in any of the models, which is consistent with the main findings. This suggests that in the context of ROE, the presence of family firms may not significantly moderate the relationship between corporate governance and profitability.

4.3.2. Other robustness tests

For robustness, we employ lagged models to investigate the impact of corporate governance (CG) and family firm status (FF) on firm performance over multiple periods, including t + 1, t + 2, and average (AVE), which represent the average return on assets over t, t + 1, and t + 2. Additionally, we introduce alternative performance measurements, such as the Market-to-Book Ratio (MBR) and Return on Equity (ROE), to assess the consistency of our findings across diverse metrics. These robustness tests address the temporal dimension of corporate governance effects and offer a more holistic perspective on the influence of family firm status on performance.

As reported in , the results show that for the TBQt model, CG has a significantly positive impact on firm performance, showing that stronger corporate governance practices contribute to enhanced performance. Nevertheless, the presence of a family firm does not seem to exert a significant influence on TBQt; however, an interesting interaction arises. The CG*FF interaction term reveals a negative association with TBQt, signifying that family firm status moderates the positive relationship between corporate governance and performance for the current period (t). Extending the analysis to subsequent periods, the TBQt+1, TBQt+2, and TBQAVE models highlight the positive impact of CG on firm performance. Conversely, family firms appear to have a diminished role in affecting performance as they lack statistical significance. Remarkably, the moderating effect of the family firm, as represented by the interaction term CG*FF, is only significant for TBQt+1, suggesting that family firms moderate the CG-performance relationship mainly in the immediate future.

Table 7. Other robustness tests.

For the return on assets (ROA), we find that CG positively influences ROAt, indicating that effective corporate governance practices enhance profitability. By contrast, family is found to negatively impact ROAt, implying that family firms may face challenges in achieving higher profitability. The interaction term CG*FF is significant, suggesting that the family firm moderates the relationship between corporate governance and profitability. In this case, the family firm enhances the positive effect of CG on ROAt. When assessing ROAt over different time horizons (ROAt+1, ROAt+2, and ROAAVE), CG positively impacts profitability for ROAt+1 and ROAt+2. However, FF is not significant. The CG*FF interaction term remains significant for ROAt+1 and ROAt+2, indicating that FF continues to moderate the relationship between CG and profitability in the short to medium term.

In summary, these robustness tests reveal that corporate governance, family firm status, and their interactions play a nuanced role in shaping firm performance. While CG consistently enhances performance, the presence of FF introduces complexities, particularly in moderating the CG-performance relationship. These findings emphasize the importance of considering temporal dynamics and firm-specific characteristics to understand the multifaceted interplay between corporate governance, family ownership, and firm performance.

This study’s results align with agency theory and signaling theory. The positive effect of CG on company performance shown in the results of this study strengthens the agency theory that a good CG mechanism will reduce conflicts of interest between principals and agents so that company goals can be easier to achieve and improve. On the other hand, this result is also in line with signaling theory, which shows that a high score on the CG mechanism implemented by the company can increase the trust of stakeholders, which in turn has a positive impact on company performance, both accounting performance and market performance.

5. Conclusion

This study delves into the intricate relationship between corporate governance disclosure (CGD) and firm performance within the Indonesian business landscape. The findings unequivocally highlight the pivotal role of CGD in shaping corporate performance, emphasizing its positive impact, which is weakened in family firms. Additionally, this study bolstered its credibility by applying robustness tests, including lagged models and alternative performance metrics. Within the framework of a two-tier management system, as observed in Indonesia, the effective implementation of a robust CG mechanism has emerged as a powerful driver of corporate performance. This study demonstrates that CG substantially and positively influences overall corporate performance, encompassing both market and accounting dimensions. Nonetheless, a concentrated ownership structure, particularly within the context of family firms, can attenuate the favorable effects of CG implementation on corporate performance.

This study has significant implications for corporate governance practices, particularly in family-owned firms. This study emphasizes the crucial role of Corporate Governance Disclosure (CGD) in enhancing the performance of Indonesian family firms. For companies, implementing sustainability report disclosure, in the long run, can improve company performance due to the positive image of the company’s operational environment. However, companies can consider the costs of implementing and disclosing social responsibility to balance costs and benefits. Government regulations should be designed to involve minority shareholders in the selection process of board and audit committee members within family firms. This approach ensures higher professionalism and independence in their pivotal roles. Such regulatory steps can potentially elevate corporate governance standards, promoting better performance and integrity in Indonesian family-owned businesses and similar contexts worldwide. However, it is important to note that this study relied on secondary data, specifically archival data, from the datasets. This limitation means that the analysis primarily focuses on what is available in the documented records, potentially overlooking the practical intricacies of corporate governance mechanisms. In addition, the limitation of family company measurement that uses dummy variables based on the percentage of family share ownership (at least 20%), may also impact the results of this study. Future research could bridge this gap by incorporating qualitative data from direct observations or interviews, offering a more holistic view of corporate governance practices and strengthening the research findings.

Authors’ contributions

Azwir Nasir: Conception and design of study, Acquisition of data, Interpretation of data, Drafting the manuscript for initial submission. Wan Adibah Wan Ismail: Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Interpretation of data, Drafting the manuscript for initial submission. Khairul Anuar Kamarudin: Conception and design of study, Analysis of data, Interpretation of data, Drafting the manuscript for initial submission. Atika Zarefar: Conception and design of study, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data. Armadani: Conception and design of study, Drafting the manuscript for initial submission.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the editor, two anonymous referees, and workshop participants at Universitas Riau, Indonesia, Universiti Teknologi Mara, and Universiti Utara Malaysia for insightful and constructive comments. Armadani would like to thank Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP) from the Ministry of Finance Republic Indonesia for granting the scholarship and supporting this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The financial data that support the findings of this study are available from Thomson Refinitiv database. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. The corporate governance data are publicly available in IDX Indonesia stock exchange website.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Azwir Nasir

Azwir Nasir is an Associate Professor at Riau University. He received her Ph.D. in Accounting from Universiti Selangor Malaysia, Malaysia in 2016. His research interests financial accounting, market-based accounting research, corporate governance and financial reporting. Azwir has published various articles in top peer reviewed accounting journals, among others, Investment Management and Financial Innovations, Problems and Perspectives in Management, Contemporary Economics and International Journal of Economic Research.

Wan Adibah Wan Ismail

Wan Adibah Wan Ismail is an Associate Professor at Universiti Teknologi Mara, Malaysia. She received her Ph.D. in Accounting from Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand in 2012. She also holds a professional qualification from Chartered Institute of Management Accountants (CIMA), United Kingdom and a Bachelor of Commerce and Management (Hons) from Lincoln University, New Zealand. Her research interests are in the field of financial reporting; particularly on earnings quality, earnings management, corporate governance, auditing, and corporate ownership. Her research has been published in top peer reviewed accounting journals, among others, International Journal of Auditing, Managerial Auditing Journal, Pacific Accounting Review, Journal of Applied Accounting Research, Accounting Research Journal, Asian Review of Accounting, Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, and Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting.

Khairul Anuar Kamarudin

Khairul Anuar Kamarudin is an Associate Professor at the University of Wollongong in Dubai. His research interests include auditing, market-based accounting research, corporate governance and financial reporting. Khairul has published various articles in top peer reviewed accounting journals, among others, International Journal of Auditing, Journal of Contemporary Accounting and Economics, Managerial Auditing Journal, Journal of International Accounting Research, Pacific Accounting Review, Journal of Applied Accounting Research, Accounting Research Journal, Asian Review of Accounting, Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting and Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research.

Atika Zarefar

Atika Zarefar is an Assistant Professor at Riau University, Indonesia. She graduated from Indonesia University. Her current research focuses include financial accounting, corporate governance, and sustainability reporting quality. She has published article in in top peer reviewed accounting journals, namely Business: Theory and Practice.

Armadani

Armadani is magister student at Airlangga University, Indonesia. His current research focuses include financial accounting, corporate governance, and sustainability reporting quality. He has published article in in top peer reviewed accounting journals, namely Journal Dinamika Akuntansi.

References

- Agrawal, A., & Chadha, S. (2005). Corporate governance and accounting scandals. The Journal of Law and Economics, 48(2), 371–406. https://doi.org/10.1086/430808

- Al-Absy, M. S. M., Ismail, K. N. I. K., & Chandren, S. (2019). Corporate governance mechanisms, whistle-blowing policy and real earnings management. International Journal of Financial Research, 10(6), 265–282. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijfr.v10n6p265

- Aldamen, H., Duncan, K., Kelly, S., & McNamara, R. (2020). Corporate governance and family firm performance during the Global Financial Crisis. Accounting & Finance, 60(2), 1673–1701. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12508

- Aldhamari, R., Mohamad Nor, M. N., Boudiab, M., & Mas’ud, A. (2020). The impact of political connection and risk committee on corporate financial performance: Evidence from financial firms in Malaysia. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 20(7), 1281–1305. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-04-2020-0122

- Aluchna, M., Mahadeo, J. D., & Kamiński, B. (2020). The association between independent directors and company value. Confronting evidence from two emerging markets. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 20(6), 987–999. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-08-2019-0263

- Anderson, R. C., & Reeb, D. M. (2003). Founding-family ownership and firm performance: Evidence from the S&P 500. The Journal of Finance, 58(3), 1301–1328. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6261.00567

- Badrul Muttakin, M., Khan, A., & Subramaniam, N. (2014). Family firms, family generation and performance: Evidence from an emerging economy. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 4(2), 197–219. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAEE-02-2012-0010

- Beasley, M. S., Carcello, J. V., Hermanson, D. R., & Neal, T. L. (2009). The audit committee oversight process. Contemporary Accounting Research, 26(1), 65–122. https://doi.org/10.1506/car.26.1.3

- Burak, E., Erdil, O., & Altindağ, E. (2016). Effect of corporate governance principles on business performance. Australian Journal of Business and Management Research, 05(07), 08–21. https://doi.org/10.52283/NSWRCA.AJBMR.20150507A02

- Casado-Díaz, A. B., Nicolau-Gonzálbez, J. L., Ruiz-Moreno, F., & Sellers-Rubio, R. (2014). The differentiated effects of CSR actions in the service industry. Journal of Services Marketing, 28(7), 558–565. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-07-2013-0205

- Castillo-Merino, D., & Rodríguez-Pérez, G. (2021). The effects of legal origin and corporate governance on financial firms’ sustainability performance. Sustainability, 13(15), 8233. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158233

- Chakroun, S., Salhi, B., Ben Amar, A., & Jarboui, A. (2020). The impact of ISO 26000 social responsibility standard adoption on firm financial performance: Evidence from France. Management Research Review, 43(5), 545–571. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-02-2019-0054

- Chatterjee, R., & Rakshit, D. (2020). Association between earnings management and corporate governance mechanisms: A study based on select firms in India. Global Business Review, 24(1), 152–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150919885545

- Chau, G., & Gray, S. J. (2010). Family ownership, board independence and voluntary disclosure: Evidence from Hong Kong. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 19(2), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2010.07.002

- Chauhan, Y., Lakshmi, K. R., & Dey, D. K. (2016). Corporate governance practices, self-dealings, and firm performance: Evidence from India. Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics, 12(3), 274–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcae.2016.10.002

- Chau, G., & Leung, P. (2006). The impact of board composition and family ownership on audit committee formation: Evidence from Hong Kong. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 15(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2006.01.001

- Chi, C. W., Hung, K., Cheng, H. W., & Lieu, P.-T. (2015). Family firms and earnings management in Taiwan: Influence of board independence. International Review of Economics and Finance, 36, 32–42.

- Chiu, J., Chung, H., & Hung, S.-C. (2021). Voluntary adoption of audit committees, ownership structure and firm performance: Evidence from Taiwan. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 57(5), 1514–1542. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2019.1635449

- Chow, Y. P. (2021). Business founders and performance of family firms: Evidence from developing countries in Asia. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 15(2), 217–239. https://doi.org/10.1108/JABS-03-2019-0095

- Ciftci, I., Tatoglu, E., Wood, G., Demirbag, M., & Zaim, S. (2019). Corporate governance and firm performance in emerging markets: Evidence from Turkey. International Business Review, 28(1), 90–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2018.08.004

- Claessens, S., Feijen, E., & Laeven, L. (2008). Political connections and preferential access to finance: The role of campaign contributions. Journal of Financial Economics, 88(3), 554–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2006.11.003

- Cordeiro, J. J., Galeazzo, A., Shaw, T. S., Veliyath, R., & Nandakumar, M. K. (2018). Ownership influences on corporate social responsibility in the Indian context. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 35(4), 1107–1136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-017-9546-8

- Cornett, M. M., Marcus, A. J., & Tehranian, H. (2008). Corporate governance and pay-for-performance: The impact of earnings management. Journal of Financial Economics, 87(2), 357–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2007.03.003

- del Carmen Briano-Turrent, G., & Poletti-Hughes, J. (2017). Corporate governance compliance of family and non-family listed firms in emerging markets: Evidence from Latin America. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 8(4), 237–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2017.10.001

- Devie, D., Liman, L. P., Tarigan, J., & Jie, F. (2020). Corporate social responsibility, financial performance and risk in Indonesian natural resources industry. Social Responsibility Journal, 16(1), 73–90. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-06-2018-0155

- Dey, A. (2008). Corporate governance and agency conflicts. Journal of Accounting Research, 46(5), 1143–1181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679X.2008.00301.x

- El Diri, M., Lambrinoudakis, C., & Alhadab, M. (2020). Corporate governance and earnings management in concentrated markets. Journal of Business Research, 108, 291–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.013

- Farooq, M., Noor, A., & Ali, S. (2022). Corporate governance and firm performance: Empirical evidence from Pakistan. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 22(1), 42–66. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-07-2020-0286

- Gambo, J. S., Terzungwe, N., Joshua, O., & Agbi, S. E. (2019). Board independence, expertise, foreign board member and financial performance of listed insurance firms in Nigeria. International Journal of Management, Accounting and Economics, 6(11), 780–794.

- González, M., Guzmán, A., Pablo, E., & Trujillo, M.-A. (2019). Is board turnover driven by performance in family firms? Research in International Business and Finance, 48(April 2018), 169–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2018.12.002

- Gujarati. (1995). Gujarati: Basic econometrics (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Harkin, S. M., Mare, D. S., & Crook, J. N. (2020). Independence in bank governance structure: Empirical evidence of effects on bank risk and performance. Research in International Business and Finance, 52, 101177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2019.101177

- Ho, J., Huang, C. J., & Karuna, C. (2020). Large shareholder ownership types and board governance. Journal of Corporate Finance, 65(June), 101715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2020.101715

- Hoseini, M., Safari Gerayli, M., & Valiyan, H. (2019). Demographic characteristics of the board of directors’ structure and tax avoidance: Evidence from Tehran Stock Exchange. International Journal of Social Economics, 46(2), 199–212. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-11-2017-0507

- Ibrahim, G., Mansor, N., & Ahmad, A. U. (2020). The mediating effect of internal audit committee on the relationship between firms financial audits and real earnings management. International Journal of Scientific and Technology Research, 9(4), 816–822.

- Imamah, N., Lin, T.-J., Suhadak, S. R., Handayani & Hung, J.-H. (2019). Islamic law, corporate governance, growth opportunities and dividend policy in Indonesia stock market. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 55(March), 110–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2019.03.008

- Jaggi, B., & Leung, S. (2007). Impact of family dominance on monitoring of earnings management by audit committees: Evidence from Hong Kong. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 16(1), 27–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2007.01.003

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

- Kao, M. F., Hodgkinson, L., & Jaafar, A. (2019). Ownership structure, board of directors and firm performance: Evidence from Taiwan. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 19(1), 189–216. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-04-2018-0144

- Kim, S., Lee, G., & Kang, H. G. (2021). Risk management and corporate social responsibility. Strategic Management Journal, 42(1), 202–230. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3224

- Kyere, M., & Ausloos, M. (2020). Corporate governance and firms financial performance in the United Kingdom. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 26(2), 1871–1885. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.1883

- Lawal, B. (2011). Board dynamics and corporate performance: Review of literature, and empirical challenges. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 4(1), 22–35. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v4n1p22

- Lee, T., & Chu, W. (2017). The relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: Influence of family governance. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 8(4), 213–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2017.09.002

- Li, D., Lin, H., & Yang, Y. W. (2016). Does the stakeholders-corporate social responsibility (CSR) relationship exist in emerging countries? Evidence from China. Social Responsibility Journal, 12(1), 147–166. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-01-2015-0018

- Lin, W. L., Ho, J. A., Ng, S. I., & Lee, C. (2020). Does corporate social responsibility lead to improved firm performance? The hidden role of financial slack. Social Responsibility Journal, 16(7), 957–982. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-10-2018-0259

- Mahrani, M., & Soewarno, N. (2018). The effect of good corporate governance mechanism and corporate social responsibility on financial performance with earnings management as mediating variable. Asian Journal of Accounting Research, 3(1), 41–60. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJAR-06-2018-0008

- Manogna, R. L. (2021). Ownership structure and corporate social responsibility in India: Empirical investigation of an emerging market. Review of International Business and Strategy, 31(4), 540–555. https://doi.org/10.1108/RIBS-07-2020-0077

- Marques, P., Presas, P., & Simon, A. (2014). The heterogeneity of family firms in CSR engagement. Family Business Review, 27(3), 206–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486514539004

- Masmoudi Mardessi, S., & Makni Fourati, Y. (2020). The impact of audit committee on real earnings management: Evidence from Netherlands. Corporate Governance and Sustainability Review, 4(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.22495/cgsrv4i1p3

- Mishra, R., & Kapil, S. (2017). Effect of ownership structure and board structure on firm value: evidence from India. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 17(4), 700–726. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-03-2016-0059

- Morck, R., & Yeung, B. (2004). Special issues relating to corporate governance and family control. Special Issues Relating to Corporate Governance and Family Control.

- Musallam, S. R. (2018). The direct and indirect effect of the existence of risk management on the relationship between audit committee and corporate social responsibility disclosure. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 25(9), 4125–4138. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-03-2018-0050

- Muttakin, M. B., Khan, A., & Subramaniam, N. (2015). Firm characteristics, board diversity and corporate social responsibility: Evidence from Bangladesh. Pacific Accounting Review, 27(3), 353–372. https://doi.org/10.1108/PAR-01-2013-0007

- Naciti, V. (2019). Corporate governance and board of directors: The effect of a board composition on firm sustainability performance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 237, 117727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.117727

- Nawawi, A. H. T., Agustia, D., Lusnadi, G. M., & Fauzi, H. (2020). Disclosure of sustainability report mediating good corporate governance mechanism on stock performance. Journal of Security and Sustainability Issues, 151–170. https://doi.org/10.9770/jssi.2020.9.j(12)

- Neffe, C., Wilderom, C. P. M., & Lattuch, F. (2022). Emotionally intelligent top management and high family firm performance: Evidence from Germany. In European Management Journal, 40(3), 372–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2021.07.007

- Nguyen, X. H., & Trinh, H. T. (2020). Corporate social responsibility and the non-linear effect on audit opinion for energy firms in Vietnam. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1757841. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1757841

- Pareek, R., & Sahu, T. N. (2022). How far the ownership structure is relevant for CSR performance? An empirical investigation. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 22(1), 128–147. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-10-2020-0461

- Prado-Lorenzo, J.-M., Gallego-Alvarez, I., & Garcia-Sanchez, I. M. (2009). Stakeholder engagement and corporate social responsibility reporting: The ownership structure effect. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 16(2), 94–107. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.189

- Pricewaterhouse Coopers (PwC). (2014). Survey Bisnis Keluarga Indonesia. 2014 (Issue November).

- Purbawangsa, I. B. A., Solimun, S., Fernandes, A. A. R., & Mangesti Rahayu, S. (2020). Corporate governance, corporate profitability toward corporate social responsibility disclosure and corporate value (comparative study in Indonesia, China and India stock exchange in 2013-2016). Social Responsibility Journal, 16(7), 983–999. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-08-2017-0160

- Rodriguez-Fernandez, M. (2016). Social responsibility and financial performance: The role of good corporate governance. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 19(2), 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brq.2015.08.001

- Rose, C. (2016). Firm performance and comply or explain disclosure in corporate governance. European Management Journal, 34(3), 202–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2016.03.003

- Rubino, M., & Vitolla, F. (2014). Internal control over financial reporting: Opportunities using the cobit framework. Managerial Auditing Journal, 29(8), 736–771. https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-03-2014-1016

- Said, R., Joseph, C., & Sidek, N. Z. M. (2017). Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosure: The moderating role of cultural values. Developments in Corporate Governance and Responsibility, 12, 189–206. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2043-052320170000012013

- Saito, T. (2008). Family firms and firm performance: Evidence from Japan. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 22(4), 620–646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjie.2008.06.001

- Schäuble, J. (2019). The impact of external and internal corporate governance mechanisms on agency costs. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 19(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-02-2018-0053

- Singla, H. K. (2020). Does family ownership affect the profitability of construction and real estate firms? Evidence from India. Journal of Financial Management of Property and Construction, 25(1), 107–124. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMPC-08-2019-0067

- Siregar, S. V., & Utama, S. (2008). Type of earnings management and the effect of ownership structure, firm size, and corporate-governance practices: Evidence from Indonesia. The International Journal of Accounting, 43(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intacc.2008.01.001

- Spence, M. (1973). Job market signaling. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(3), 355–374. https://doi.org/10.2307/1882010

- Suhadak, S., Mangesti Rahayu, S., & Handayani, S. R. (2019). CG, financial architecture on stock return, financial performance and corporate value. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 69(9), 1813–1831. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-09-2017-0224

- Tjahjadi, B., Soewarno, N., & Mustikaningtiyas, F. (2021). Good corporate governance and corporate sustainability performance in Indonesia: A triple bottom line approach. Heliyon, 7(3), e06453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06453

- Utama, C. A., Utama, S., & Amarullah, F. (2017). Corporate governance and ownership structure: Indonesia evidence. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 17(2), 165–191. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-12-2015-0171

- Wahyudin, A., & Solikhah, B. (2017). Corporate governance implementation rating in Indonesia and its effects on financial performance. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 17(2), 250–265. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-02-2016-0034

- Worokinasih, S., & Zaini, M. L. Z. B. M. (2020). The mediating role of corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosure on good corporate governance (CG) and firm value. Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, 14(1), 88–96. https://doi.org/10.14453/aabfj.v14i1.9

- Xue, B., Zhang, Z., & Li, P. (2020). Corporate environmental performance, environmental management and firm risk. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(3), 1074–1096. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2418

- Yeon, J., Lin, M. S., Lee, S., & Sharma, A. (2021). Does family matter? The moderating role of family involvement on the relationship between CSR and firm performance. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(10), 3729–3751. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-03-2021-0315

- Zaid, M. A. A., Abuhijleh, S. T. F., & Pucheta-Martínez, M. C. (2020). Ownership structure, stakeholder engagement, and corporate social responsibility policies: The moderating effect of board independence. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(3), 1344–1360. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1888