Abstract

Organizational inefficiency and ineffectiveness are often linked to identity crises within the organizational context. This systematic review seeks to enhance the comprehension of Organizational Culture (OC) as a crucial approach to addressing such crises. The study focusses on the measurements, perspectives, and orientations of OC, providing comprehensive analyses of recent research on the subject. Employing a systematic literature review methodology, rigorous screening criteria were applied to select articles from reputable databases, such as Science Direct, Elsevier, Taylor & Francis, JSTOR, Emerald, Springer, Wiley, SAGE, and Google Scholar. A total of 52 articles, meeting the defined selection criteria, underwent thorough review and analysis, yielding valuable insights. The findings emphasize the significant impact of OC on workplace dynamics, influencing employee interactions, treatment, and management. The dimensions most frequently explored within OC include innovation, teamwork, result orientation, masculinity, involvement, and power distance. This review delves into the existing literature on the creation and modification of OCs, utilizing three distinct perspectives: functional, leader-trait, and culture transfer. Cultural orientations are categorized into four main groups: workplace orientation, business orientation, system orientation, and group orientation. In conclusion, this study identifies limitations in current research and proposes potential future research directions, thereby contributing to the ongoing discourse on organizational culture and its implications for organizational effectiveness and efficiency.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Organizational Culture (OC) serves as a foundational set of beliefs shaped by the members of an organization through external adaptation or internal integration (Schein, Citation1992). Schein (Citation1992) pioneered an OC framework, extensively cited by scholars (e.g. Alvesson, Citation2002; Belias & Koustelios, Citation2014; Bhuiyan et al., Citation2020; Ipinazar et al., Citation2021; Latta, Citation2020; Reeder, Citation2020; Sarhan et al., Citation2020; Setiawan, Citation2020). Akhavan et al. (Citation2014) similarly define OC as a collection of fundamental assumptions, norms, values, and shared conduct transmitted to newcomers. Many researchers (e.g. Baird et al., Citation2018; Ouellette et al., Citation2020; Yip et al., Citation2020) concur that OC encompasses a common set of values, behaviors, conventions, attitudes, assumptions, and beliefs among organizational members.

As articulated by Hardcopf et al. (Citation2021), OC is a group attitude that evolves over time and proves resistant to modification once established. In line with Akhavan et al. (Citation2014), OCs significantly influence interpersonal interactions, behaviors, and communication among employees during day-to-day work. Consequently, OC emerges as a key organizational feature and situational aspect, exhibiting potential stability or flexibility that permeates all facets and activities of the organization. Groysberg et al. (Citation2018) categorize cultures as either stable, emphasizing authority, order, consistency, predictability, and the status quo, or flexible, characterized by adaptability, openness to change, learning, creativity, and innovation.

The impact of OC on employee job satisfaction (Yiing et al., Citation2009), organizational change (Bagga et al., Citation2022), productivity (Elsbach & Stigliani, Citation2018), and employee turnover (Bortolotti et al., Citation2015) has been extensively explored. Scholars have delved into various management subdomains, including organizational performance (Bwonya et al., Citation2020; Paais & Pattiruhu, Citation2020; Pathiranage et al., Citation2020; Wilderom et al., Citation2012), learning organization (Githuku et al., Citation2022; Ju et al., Citation2021; Nellen et al., Citation2020; Xie, Citation2019), causal and corrective OC (Hald et al., Citation2020), job satisfaction (Ahn & Hee, Citation2019; Belias & Koustelios, Citation2014; Sabuhari et al., Citation2020; Setiawan, Citation2020), innovation (Azeem et al., Citation2021; Büschgens et al., Citation2013; Hogan & Coote, Citation2014; Hussain et al., Citation2022; Le et al., Citation2020; Naveed et al., Citation2022; Zhen et al., Citation2021), artificial intelligence technology (Bilan et al., Citation2022), and environmental activity management (Baird et al., Citation2018; Dai et al., Citation2018; Tung et al., Citation2014).

The study of OC has garnered significant attention in academic literature due to its profound implications for organizational success and performance (Carvalho et al., Citation2023). Existing systematic reviews have contributed to our understanding of various aspects of OC, such as its relationship with competitive advantage, job satisfaction, innovation, sustainability, and digitalization. For instance, Ramos and Ellitan (Citation2022) provided a theoretical review of OC’s role in competitive advantage, while Belias and Koustelios (Citation2014) explored its connection with job satisfaction. Moreover, Isensee et al. (Citation2020) delved into the relationship between OC, sustainability, and digitalization. Despite these valuable contributions, there remains a notable gap in the literature regarding a comprehensive synthesis of the main dimensions, perspectives, and orientations in OC. By systematically reviewing and synthesizing existing literature, this study seeks to offer insights into the multifaceted nature of OC, thereby providing valuable guidance for both scholars and practitioners seeking to understand and leverage the power of organizational culture for enhanced performance and competitiveness. We present a comprehensive systematic review of OC studies conducted from 2014 to 2022, employing the five-step approach outlined by Deyner and Tranfield (Citation2009). The research questions guiding this review are as follows:

Research Questions:

What are the main dimensions of OC?

What are the primary perspectives influencing the creation and change of OC?

What are the predominant orientations of OC?

What promising avenues exist for further OC research?

The subsequent sections of this study include a detailed literature review, an in-depth description of the methodology employed, the presentation of results, discussions, suggestions for future research, theoretical and practical implications, conclusions, and limitations.

2. Literature review

2.1. Definition of organizational culture

OC is a set of norms, values, beliefs, and attitudes that guide the actions of all organization members and have a significant impact on employee behavior (Schein, Citation1992). Supporting Schein’s definition, Denison et al. (Citation2012) define OC as the underlying values, protocols, beliefs, and assumptions that organizational members hold, and it is strongly supported by the organizational structure and fundamental principles. In addition, Denison and Mishra (Citation1995) classified OC as having the following four characteristics: involvement, consistency, adaptability, and mission.

Most OC definitions commonly specify ‘OC’ as a shared characteristic among individuals within the organization (Denison et al., Citation2015; Yilmaz & Ergun, Citation2008). Some examples of these shared characteristics are beliefs, values, behavior norms, customs, rituals, and ways of making sense (Abdalla et al., Citation2020). Therefore, OC is a lens that may be used to see and analyze an organization (Parmelli et al., Citation2011).

OC includes sociocultural activities (Chatman & O’Reilly, Citation2016; Nzuva, Citation2022), recurring perceptual patterns (Scott & Allen, Citation2022), work procedures (Wilderom et al., Citation2012), sets of myths and symbols (Tulcanaza-Prieto et al., Citation2021), and, common attitudes and behaviors (Belias & Koustelios, Citation2014). OC encompasses deeper values and serves as a foundation for developing shared norms (Paais & Pattiruhu, Citation2020).

2.2. Organizational culture models

2.2.1. Hofstede’s model

Hofstede (Citation2011) identified six attributes of organizational cultures, namely: process-vs.-results-oriented, employee-vs.-job-oriented, professional-vs.-parochial, open-vs.-closed systems, tight-vs.-lose-control, and pragmatic-vs.-normative.

2.2.1.1. Process-oriented vs. results-oriented

Hofstede (Citation2011) argued that process-oriented organizations strongly emphasize technical expertise and established procedures, while results-oriented organizations emphasize outcomes.

2.2.1.2. Job-oriented vs. employee-oriented

Without employees, a business would struggle to accomplish its objectives. Employees are an organization’s most valuable asset. Hofstede (Citation2011) explained that job-oriented organizations are more concerned with an employee’s performance than their overall well-being, and vice versa refers to employee-oriented organizations.

2.2.1.3. Professional and parochial

This dimension can be used to categorize an organization’s members. The parochial perspective contends that members are identified with their work, whereas the professional perspective is linked to members who prefer to be associated with a recognized professional body. Hofstede (Citation2011) argued that, since most educated people identify with their profession, education level breeds the professional dimension and vice versa.

2.2.1.4. Open systems vs. closed systems

Organizational survival depends strongly on communication (Olum, Citation2011). An open system allows for the unrestricted flow of information throughout the organization, in contrast to a closed system where information is kept strictly confidential.

2.2.1.5. Tight vs. lose control

Some organizations have strong regulations with harsh consequences for members who violate them. In contrast, Others are more lenient and have fewer standards to follow; they are looser. Organizational tightness and looseness frequently change for legitimate reasons (Olum, Citation2011).

2.2.1.6. Pragmatic vs. normative

Hofstede (Citation2011) specified that Market-driven characteristics are the main feature of pragmatic cultures, while normative cultures view their role in the world as enforcing certain sacred laws. Individuals from normative cultures place more value on the organizational protocol.

2.2.2. Organizational culture profile (OCP) model

O’Reilly et al. (Citation1991) identified seven profiles, such as innovation, stability, respect for people, outcome orientation, attention, team, and aggression.

2.2.2.1. Innovation

The innovation profile focuses on an organization’s capacity to investigate new trends in its area of expertise. Such profile is supported by risks taking, taking advantage of opportunities as they present themselves, and being creative (O’Reilly et al., Citation1991).

2.2.2.2. Stability

According to O’Reilly et al. (Citation1991), stable businesses give their employees job security, are known for their predictability, and do not follow emphatic rules. In their updated OCP, Sarros et al. (Citation2005) replaced ‘predictability’ and ‘no emphatic rules’ with ‘calm’ and ‘low disagreement’.

2.2.2.3. Respect for people

The contributions of the organization’s employees are the only thing that keeps the organization running. When individuals in positions of leadership show respect for their subordinates, it inspires them to contribute their efforts to transforming organizations. This profile reveals a lot about an organization’s capacity for respecting, treating fairly, and tolerating its employees regardless of their behaviors (O’Reilly et al., Citation1991).

2.2.2.4. Outcome orientation

emphasis on the organization’s desire to accomplish its objectives and its high expectations for results (O’Reilly et al., Citation1991).

2.2.2.5. Attention

In this orientation, organization members value analytical awareness and place a strong emphasis on the necessity of precision and correctness of results, and they pay close attention to details (O’Reilly et al., Citation1991). The Hofstede (Citation2011) process orientation is associated with this profile.

2.2.2.6. Team

Collaboration and people-oriented behavior are part of team orientation (O’Reilly et al., Citation1991). This profile aims to develop an organization’s internal structures and create a stronger link among its members.

2.2.2.7. Aggressive

Through employment and other societal responsibilities, organizations position themselves to assist and address the demands of society (Mcauley et al., Citation2007). The outside environment where the organization is situated has an aggressive profile. The distinctive features of this profile are aggression, competitiveness, and social responsibility.

2.2.3. Organizational culture assessment instrument (OCAI)

The organizational Culture Assessment Instrument (OCAI) framework specified four main types of culture, such as clan, market, adhocracy, and hierarchy typologies. The fundamentals of the OCAI were derived from the ‘Competing Values Framework’ which was created by Cameron and Quinn (Citation2006). The framework evaluates culture based on external-internal dimensions and a focus on greater or lesser flexibility. The external-internal dimension categorizes an organization’s culture based on how it reacts to its external business or professional environment and how it addresses its internal organizational structure, respectively. More-or-less flexibility refers to a measurement of an organization’s capacity to respond to changes in its environment (Cameron & Quinn, Citation2006).

2.2.3.1. Clan

As stated by Cameron and Quinn (Citation2006), Organizational environments that foster cooperation and friendliness provide the position for clan cultures which elaborate, every organization has structures that enforce the unity of its workforce, management, employees, and, ultimately, its clients. The competing value framework’s internal and integration paradigms serve as the foundation for clan culture. The expressions of clan culture also include teamwork, full employee involvement in the business, and employee capability development.

Cameron and Quinn (Citation2006) argued that the clan culture is a method for gaining the loyalty, interest, and trust of staff members, which has a positive impact on an organization’s ability to perform activities. The clan culture adheres to the philosophy of Elton Mayo and is based on management theories. The study by Olum (Citation2011) revealed that the encouragement of informal groups, a positive work environment, employee engagement, and teamwork all contribute to higher productivity. According to Albayrak and Albayrak (Citation2014), communication is crucial in Clan culture. In the clan culture, employers are viewed as the parents and employees as the children. Ineffective clan communication fosters a chaotic environment. Effective communication benefits both employers and employees because it enables employers to communicate their vision to employees, resolve internal conflicts, and address various challenges. The concepts of clan and market cultures are essentially the same, but the audience is different because the market culture is geared toward customers, while the clan relationship is oriented toward employees.

2.2.3.2. Hierarchy

When an organization is thought of as having a hierarchy, the notion of rigid structures is brought to the forefront. Owners, top management, middle management, and mere workers are different categories of employees in an organization. This classification establishes the line of authority within an organization to ensure what, when, and how actions are taken to aid the objective’s achievement. Cameron and Quinn (Citation2006) argued that structures improve stability, accuracy, reliability, and consistency. This improves the organization’s internal standardization and the quality of its goods and services.

2.2.3.3. Adhocracy

Cameron and Quinn (Citation2006) stated that the keyword in this culture is ‘ad hoc’, which can be understood to mean a temporary way of running an organization. The impact of the business environment necessitates flexibility and informality within organizations. According to Worrall (Citation2012), adhocracy serves as the foundation for cultural change in organizations because of its capacity for environmental adaptation. This is not intended to imply that an organization will compromise on anything besides those issues that will give it a competitive edge or advantage over rivals. Cameron and Quinn (Citation2006) indicated that adhocracy’s achievement can be seen in how organizations are adopting new ideas.

2.2.3.4. Market

The term ‘market’ in the context of OC is highly figurative and does not necessarily refer to a physical market where buying and selling take place. Optimizing production costs and maximizing profit is a fundamental tenet of organizational management. The cutting edge of organizations in today’s competitive business environment is their capacity to compete in the market. According to Albayrak and Albayrak (Citation2014), if an organization is focused on its competitive bid, customers should be the central focus. Without customers, organizations cannot succeed and will lose their competitiveness.

2.2.4. Revised organizational culture profile (ROCP) model

O’Reilly et al. (Citation1991) OCP was revised by Sarros et al. (Citation2005) under the following different thematic areas:

2.2.4.1. People culture

Even if an organization is established to make a profit, understanding the employees’ behavioral patterns is also crucial to adapt employees centered strategy. People-oriented organizations strengthen their internal structures by offering necessary training and development to workers, by implementing reward programs to acknowledge workers’ contributions, and by maintaining a friendly working environment between management and employees (O’Reilly et al., Citation1991).

2.2.4.2. Business culture

The key feature of a business-oriented organization has become competition. Being out of competition would be strange for an organization because competition motivates the organization to define its qualities. Effective organizations always set themselves as a benchmark for others to follow. Organizations with the aforementioned characteristics are referred to as having a business culture (Sarros et al., Citation2005).

2.2.4.3. Environment culture

According to Mcauley et al. (Citation2007), Organizations are introduced to fulfill society’s mission. Some organizations prioritize social responsibility to fulfill their fair share of social obligations. Organizations are also governed by environmental forces like legal, political, and regulatory pressures. Thus, an organization can be classified as environmentally oriented because of its willingness to address these pressures.

2.2.4.4. Adaptation

The ability of the organization to respond to new developments or innovations in the industry is the main focus of the adaptation dimension (Mobley et al., Citation2005). This dimension reveals the organization’s openness to altering its practices or behaviors, its focus on the customer, and its culture of learning. As Cameron and Quinn (Citation2006) stated, this dimension can be referred to as the organization’s willingness to take a risk based on its competing value.

2.2.4.5. Consistency

Organizations are well-shaped as a result of the difficulties they face in carrying out their mission. However, a successful approach to problem-solving can become a benefit that the organization and its members share. In this dimension, internal structures are stressed, which consider reaching a consensus and making sure that all departmental goals line up with the overall objective of the organization (Denison & Mishra, Citation1995).

2.2.4.6. Mission

The organizational goals, visions, and strategic plans direct the organization’s path (Denison & Mishra, Citation1995). This dimension contends that organizations can be categorized according to how strongly they place a focus on achieving their objectives. The mission dimension strengthens the stability of organizations and directly affects them because it determines how, when, and in what activities they can engage.

2.2.4.7. Involvement

This dimension is characterized by developing, equipping, and maintaining the workforce of the organization through participation, collaboration, and capacity building (Denison & Mishra, Citation1995; Mobley et al., Citation2005).

2.2.5. Behavioural Norms Model

The Behavioral Norms Model is a widely recognized framework for understanding organizational culture. According to this model, organizational culture is shaped by behavioral norms that guide employee actions and interactions within the organization. These behavioral norms are the shared expectations and values that define how individuals should behave in the workplace (Cooke & Rousseau, Citation1988).

Research has shown that the Behavioral Norms Model can have a significant impact on organizational outcomes. For example, a study by Cameron and Quinn (Citation2006) found that organizations with a strong culture characterized by clear behavioral norms had higher levels of employee satisfaction and commitment. This suggests that when employees understand and internalize the behavioral norms of an organization, they are more likely to engage in behaviors that contribute to organizational effectiveness.

The Behavioral Norms Model also highlights the role of leadership in shaping organizational culture. Schein (Citation1992) argues that leaders play a critical role in establishing and reinforcing behavioral norms within an organization. Through their actions and communication, leaders can influence the values and expectations that guide employee behavior.

In summary, the Behavioral Norms Model emphasizes the importance of shared behavioral norms in shaping organizational culture. Understanding and aligning with these norms can lead to positive outcomes, such as increased employee satisfaction and commitment.

2.2.6. Model of Organizational Culture and Effectiveness

The Model of Organizational Culture and Effectiveness provides a comprehensive framework for examining the relationship between organizational culture and organizational effectiveness (Denison, Citation1990). This model suggests that certain cultural characteristics can enhance or hinder an organization’s ability to achieve its goals.

The model identifies four key dimensions of organizational culture: involvement, consistency, adaptability, and mission. Involvement refers to the extent to which employees are engaged and participate in decision-making processes. Consistency refers to the degree of alignment and coordination among different parts of the organization. Adaptability refers to the organization’s ability to respond and adapt to changes in the external environment. Mission refers to the clarity and alignment of organizational goals and values.

The Model of Organizational Culture and Effectiveness also highlights the importance of fit between organizational culture and the external environment. Organizations that are able to align their culture with the demands of the external environment are more likely to achieve high levels of effectiveness (Denison, Citation1990).

Our study aims to comprehensively examine the landscape of organizational culture and to effectively accomplish this task, it is essential to integrate and explore various organizational culture models. The link between these models lies in their complementary perspectives, each providing unique insights into different facets of organizational culture. Firstly, Hofstede’s model delineates key dimensions of organizational culture, such as process vs. results orientation, job vs. employee orientation, professional vs. parochial perspective, open vs. closed systems, tight vs. loose control, and pragmatic vs. normative approaches. These dimensions offer a foundational understanding of cultural variations within organizations. Secondly, the OCP model, alongside its revision, the ROCP model, delineates organizational cultures based on profiles, such as innovation, stability, respect for people, outcome orientation, attention, team, and aggression, as well as thematic areas like people culture, business culture, environment culture, adaptation, consistency, mission, and involvement. These profiles and dimensions provide a nuanced view of organizational cultures, focusing on aspects, such as adaptability, employee relations, and alignment with external demands. Thirdly, the OCAI offers a framework categorizing cultures into clan, market, adhocracy, and hierarchy typologies, assessing their external-internal dimensions and flexibility levels. This framework provides a structured approach to evaluating cultural dynamics within organizations, emphasizing flexibility and responsiveness to environmental changes. Fourthly, the Behavioral Norms Model elucidates the role of shared behavioral norms in shaping organizational culture, underscoring their impact on employee behavior and organizational outcomes. Lastly, the Model of Organizational Culture and Effectiveness offers a comprehensive framework linking cultural dimensions, such as involvement, consistency, adaptability, and mission to organizational effectiveness, highlighting the importance of alignment between culture and external demands. By integrating these diverse models, the systematic literature review can provide a holistic understanding of organizational culture, enriching scholarly discourse and informing practical interventions in organizational settings.

3. Methods and methodology

3.1. Study design

A systematic literature review design was used in this study following the guidelines of Paul and Criado (Citation2020). There are various types of systematic literature reviews, including structured reviews, framework-based reviews, bibliometric reviews, and meta-analysis reviews. Among these review methods, we preferred the structured review method to properly understand OC, identify trends, and draw any gaps in the existing literature. This strategy is advantageous because it enables the reviewer to recognize and emphasize the theories and structures frequently applied in OC research (Kunisch et al., Citation2015). This study also used the three-stage systematic review approaches introduced by Tranfield et al. (Citation2003): (1) outlining the review’s objectives in its planning phase; (2) reviewing the relevant articles; and (3) reporting the findings.

3.2. Data collection

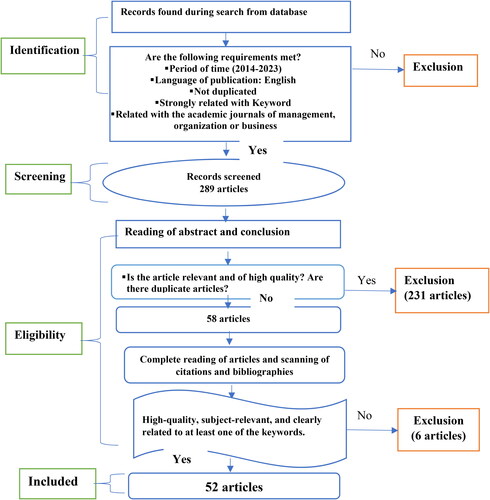

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to conduct our study. The study used some inclusion and exclusion criteria to screen the most relevant studies. The inclusion criteria include search boundary, time of publication, language, and search string. The search boundary was determined by focusing on academic journals in organization, management, and business. The search was limited to peer-reviewed articles published by English language in the past 9 years (from January 2014–December 2022). The search string was used as inclusion criteria by focusing on the theme of ‘OC’. The exclusion criteria include relevance, quality, and duplication. It was done by reading the abstracts and conclusions of downloaded articles from reputable databases, such as Science Direct, Elsevier, Taylor & Francis, JSTOR, Emerald, Springer, Wiley, SAGE, and Google Scholar. The relevance was determined by deciding whether articles fit the used keywords. The defined keywords for the search were ‘Organizational’, ‘business’, and ‘work’. These terms were cross-referenced with the term’s ‘culture’, ‘climate’, ‘norms’, ‘value’, and ‘practices’. To ensure quality, the study excluded unpublished articles, working papers, and conference papers. Duplicated articles were excluded by assigning codes to each article and by manual detection. The article screening procedure is summarized in .

3.3. Data analysis

In this study, descriptive and thematic content analysis was used to address predetermined review questions. The descriptive analysis provides readers with a brief background on the reviewed articles by presenting the results through tabulation, charts and describing the study’s characteristics (Tranfield et al., Citation2003). Moreover, thematic content analysis was used as a method of data analysis in this study. The researchers first manually encode the main issues addressed in the selected articles, and then an interpretative approach is used to analyze the results of the study.

4. Results

4.1. Types of research

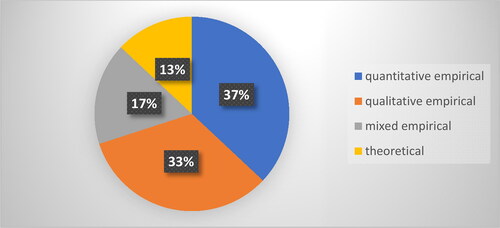

The below pie chart () shows the research methods used in selected papers. Based on the results, studies were divided into four categories: quantitative empirical research (37%), qualitative empirical research (33%), mixed empirical research (17%), and theoretical research (13%). We verified that 87% of the studies were empirical investigations.

Upon reviewing the list of articles, it’s evident that the selection encompasses a variety of research approaches, including conceptual papers, review papers, quantitative studies, qualitative studies, and mixed-methods analyses. This diversity poses challenges in terms of comparing and synthesizing findings across different types of research (See Appendix A).

4.2. Empirical studies

Some articles, such as Baird et al. (Citation2018), Hussain et al. (Citation2022), and Shuaib and He (Citation2021), provide empirical evidence through quantitative approaches like structural equation modeling (SEM) and partial least squares (PLS-SEM). These studies offer valuable insights into the relationships between organizational culture and various outcomes, such as organizational performance, employee commitment, and innovation.

Hosseini et al. (Citation2020) and Sarhan et al. (Citation2020) also contribute empirical evidence through quantitative methods, demonstrating the correlation between organizational commitment, leadership style, and organizational learning.

The qualitative studies, such as Kim and Toh (Citation2019) and Roos et al. (Citation2015), provide nuanced insights into the creation and change of organizational culture, highlighting the importance of leadership, cultural transfer, and organizational norms.

4.3. Literature reviews and conceptual papers

Conceptual papers like Binder (Citation2016) and Yip et al. (Citation2020) contribute theoretical discussions, emphasizing the impact of organizational culture on performance and outcomes. However, the lack of empirical evidence raises questions about the generalizability of their claims.

Review papers, such as Bosire and Kinyua (Citation2022) and Ouellette et al. (Citation2020), provide systematic reviews of existing literature, identifying gaps and offering insights into the conceptual, theoretical, and empirical landscape. However, these reviews may not contribute direct empirical evidence.

4.4. Publications per year

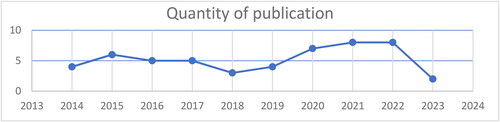

As we can observe from , the number of publications has been increasing since 2018, and the largest number of publications occurred in the years 2021 and 2023. This may be related to the growing interest of scholars in investigating contemporary organizational culture, which might result in increased researcher interest.

4.5. Analysis of studies by theme

The articles that meet the selection criteria are presented in this section. Based on a systematic analysis of selected articles, we divided studies into three main thematic categories, such as dimensions of OC, key perspectives of OC, and cultural orientations. The three main thematic categories that emerged from this rigorous process were not arbitrary but rather a result of a comprehensive and systematic review of the literature. Through a meticulous examination of the selected articles, a discerning pattern of recurring concepts and focal points within the realm of organizational culture surfaced, leading to the natural categorization into these three distinct themes. The authors’ approach in deriving these categories was methodologically sound, grounded in the collective essence of the literature, and serves as a robust foundation for organizing and presenting the diverse findings in a coherent and meaningful manner. This deliberate categorization not only aids in facilitating a nuanced understanding of the complex landscape of organizational culture but also enriches the scholarly discourse by providing a structured framework for readers to navigate the diverse dimensions, perspectives, and orientations inherent in the subject matter.

4.5.1. Organizational culture dimensions

Organizational culture dimensions focus specifically on the culture within organizations. Different researchers use different dimensions to measure organizational culture. Some studies used beliefs, norms, and workplace interactions to measure organizational culture. For instance, Yip et al. (Citation2020) stated that the basic values of an organization can be viewed as internalized normative beliefs that influence behavior. According to Ouellette et al. (Citation2020), values and norms are related to group beliefs and customs about the importance of particular behaviors, methods of doing work, and/or how to react to change. As Baird et al. (Citation2018) stated, organizational value includes teamwork, innovation, outcome orientation, and attention to detail. Also, Binder (Citation2016) points out values in NPO culture, which include innovation, environmental sustainability, & community service. In addition, Belay et al. (Citation2023) examined cultural dimensions, such as innovation, adaptability, collaboration, and ethical orientation in CSR practices.

Ouellette et al. (Citation2020) specified that the interactions between frontline workers and managers, as well as cooperation among coworkers, play a significant role in the development of OC at any organization. Hussain et al. (Citation2022) also found that interactions between employees and managers foster an innovative culture by contributing to the creation of new ideas, products, and services. Rohim and Budhiasa (Citation2019), confirm that the interactive OC is positively related to knowledge management and innovation.

Suifan (Citation2021) points out four different sub-systems that can be used to measure OC, including clan (people-oriented, friendly collaboration), hierarchy (process-oriented, structured control), market (results-oriented, competitiveness), and adhocracy (dynamic, entrepreneurial) cultures. Rostain (Citation2021), found that all of these sub-systems have a positive impact on the entrepreneurial orientation of firms. Shuaib and He (Citation2021) also confirmed that there is a significant association between innovation and OC dimensions, such as adhocracy, clan, market, and hierarchy culture. Moreover, Azeem et al. (Citation2021) also adopt adhocracy, clan, hierarchy, and market dimensions to measure OC. The study found that this culture influences the competitive advantage of organizations. Furthermore, the study also found that this culture encourages workforce innovation, knowledge sharing, and high-level business processes.

Bosire and Kinyua (Citation2022) measured OC based on power distance (power, authority, wisdom, and seniority), individualism vs. collectivism (value for achievement, rewarding systems, and individual group relationships), uncertainty avoidance (risk-taking and change), and masculinity (agreeableness, toughness, logical analysis, and quality of life). The study found that job design, decision-making, control structures, and reward systems are among the dimensions of OC.

According to Chang et al. (Citation2015), OC is measured as having cultures that are result-oriented, tightly controlled, job-oriented, closed-system, and professional-oriented. The study found that employee intention toward the knowledge management processes (knowledge creation, storage, application, and transfer) is positively associated with ‘results- and job-oriented’ cultures, whereas it is negatively associated with a tightly controlled culture. Additionally, Sarhan et al. (Citation2020) measured OC in terms of innovative, bureaucratic, and supportive dimensions. The study found that employees who work in bureaucratic and supportive environments are more committed to their organizations. Employees who work in an innovative environment, on the other hand, have a lower commitment to their organizations. Likewise, Hosseini et al. (Citation2020) measured OC in four dimensions: involvement, consistency, adaptability, and mission. The study found that leadership style and organizational learning have a significant impact on OC.

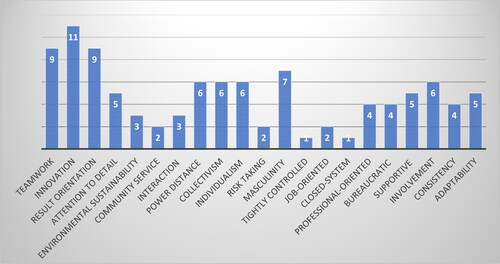

In summary, we described OC dimensions in the figure below based on a review of existing evidence ().

Based on our count result, the most frequently used OC dimensions are innovation culture (used 11 times), teamwork culture (9 times), result-oriented culture (9 times), masculinity (7 times), involvement, power distance, collectivism, and individualism (each used 6 times). However, the agreement about which dimension should be included in OC has varied from study to study.

4.5.2. Perspectives of OC

The division of studies into three main thematic categories—functional, leader-trait, and culture transfer perspectives was carried out systematically to ensure a robust and comprehensive categorization. Initiated by a thorough literature search, inclusion criteria were established to focus on studies pertaining to these specific organizational culture (OC) creation and modification perspectives. Through initial screening based on titles and abstracts, followed by a detailed full-text review, each study was assessed for alignment with the predefined themes. The thematic assignment underwent an iterative validation process, addressing disagreements through team discussions for a consensus-based approach. This systematic methodology, documented transparently, aimed to capture diverse OC perspectives, maintaining the reliability and validity of the categorization through well-defined inclusion criteria, rigorous screening, and iterative validation steps.

4.5.2.1. Functionality perspective

According to the functionality perspective, environmental changes are the main forces that influence the creation and change of OC (Kim & Toh, Citation2019). Following an extensive systematic review of the literature, we have divided the environmental factors that affect cultural creation and change into five subcategories: (i) ecological and man-made threats; (ii) market changes; (iii) rules and regulations; (iv) industry characteristics; and (v) technology.

Organizations have encountered numerous external threats that interfere with their daily activities. These include environmental hazards like disease prevalence, social (territorial) conflict, and natural disasters. According to studies (e.g. Bagga et al., Citation2022; Hällgren et al., Citation2018; Yip et al., Citation2020), organizations create cultures that help them survive and adapt to these threats.

As per an investigation conducted by Hällgren et al. (Citation2018), organizations facing threats from hazardous situations develop more rigid cultures with stricter standards of conduct, a stronger emphasis on hierarchy, accountability, and less tolerance for deviation. Gelfand and Erez (Citation2017) argued that hazardous conditions like natural disasters (i.e. severe weather, earthquakes, volcanoes, and floods) increase the cultural tightness of organizations. The tightness of the culture refers to the degree to which culture is linked to distinct norms, rules, and standards. For instance, tight organizations restrict people’s behavioral options by implementing autocratic systems, limiting media content, and enforcing strict justice (Dai et al., Citation2018; Harrington & Gelfand, Citation2014; Roos et al., Citation2015).

Additionally, organizational researchers (e.g. Bagga et al., Citation2022; Yip et al., Citation2020) have begun to investigate how diseases like COVID-19 affect OCs. Kim et al. (Citation2022) found that a culture of sanitation emerged as a result of the greater threat of disease, which influenced staff dressing (e.g. gloves, gowns, and masks) and physical composition (e.g. tiled floors, and washing stations).

In addition, Harrington and Gelfand (Citation2014) specified that rapid change in OCs can also result from repeated exposure to social conflicts (such as war). Wars can increase the degree of cultural tightness and cause cultural changes (Kim et al., Citation2022).

Studies (e.g. Gelfand & Erez, Citation2017; Kim et al., Citation2022; Weare et al., Citation2014) noted that most companies’ cultures have become less ethnocentric as a result of the significant market changes that have occurred in today’s globalized markets, which has led to the existence of a common culture among global organizations. To compete in the globalized market, organizations would have to develop new global structures and mindsets that integrate self-awareness and various global cultural values (Bagga et al., Citation2022).

Researchers (e.g. Azeem et al., Citation2021; Bukoye & Abdulrahman, Citation2022; Kim et al., Citation2019) have also found evidence of how external rules and regulations have changed OCs. Azeem et al. (Citation2021) stated that work standards, procedures, rules, and policies regulate organizational operations and characteristics. Researchers also found that environmentally friendly rules and regulations encourage organizations to develop eco-friendly cultures (Bhuiyan et al., Citation2020). Wozir and Yurtkoru (Citation2017) stated that, if there is a lot of uncertainty and risk in an organizational environment, it is more likely that policies, procedures, and rules will govern the organization to manage the uncertain environment.

Tulcanaza-Prieto et al. (Citation2021) found that the organization’s rules and regulations, which govern the conduct of particular groups of customers, coworkers, and other stakeholders, are part of the OC; as a result, employees need to recognize the company’s rules and regulations when they conduct business activities. According to Lau et al. (Citation2017), OC can also be observed in the ways that rules, procedures, policies, and regulations have an impact on how individuals behave in their work positions. Jabo (Citation2021) noted that an organization with a hierarchical culture has formalized structures, rules, and policies.

Cicea et al. (Citation2022) found that organizations are subject to mimetic influences from industries, resulting in cultural homogeneity within an industry. The OC is shaped by particular factors that are unique to each industry (Kim et al., Citation2022). Galea et al. (Citation2020) stated that firms within similar industries have more consistent cultural norms due to the inherent nature of their work. Redmond et al. (Citation2015) also compared military and non-military OC, and the result shows that military cultures tend to be more collectivist, hierarchical, aggressive, warrior-like, masculine, and strict in their chains of command.

Trade groups create the norms and procedures that control the participants in their industries. Trade associations serve as a forum for industry participants to discuss and co-create solutions to emerging issues. The created business community shares a common culture to address environmental change through workshops, conferences, and working groups (Lawton et al., Citation2017).

Kim et al. (Citation2022) found that to keep up with shifting consumer preferences as a result of changing technology, businesses have had to become more technologically and innovation-driven. Bilan et al. (Citation2022) also stated that the development of artificial intelligence has changed OC by helping them solve a wide range of organizational problems within a very short time. Similarly, Isensee et al. (Citation2020) specified that the adoption of digital technologies gives high self-esteem to organizational members.

Furthermore, Cascio and Montealegre (Citation2016) found that information and communication technology can change organizational structure and the way employees work. The study also confirmed that communication technologies have a significant impact on how employees interact with one another, perform their jobs, and organize themselves.

4.5.2.2. Leader-trait perspective

Studies mainly emphasized three key areas of the leader trait: the leader’s personality, the leader’s values, and the leader’s demographic attributes.

According to O’Reilly et al. (Citation2014), a leader’s personality is one of the main sources of OC. The study found that OC can be derived from CEO personalities. As O’Reilly et al. (Citation2014) found, CEOs’ willingness to adopt change was positively associated with flexible cultures; CEO conscientiousness was positively correlated with attention-to-detail cultures; and CEO agreeableness was inversely associated with a result-oriented culture. The study also found that CEOs who were perceived by their staff as more egocentric tended to have less integrity and less collaboration. Cortes et al. (Citation2021) also found that a leader’s personality influences how consistently he or she acts and makes decisions in organizational circumstances. The organizational members are then informed about what is important, what is to be expected, and how to behave based on the leaders’ consistent behavioral patterns. This sets the ‘tone’ for the business, which eventually creates OC.

Kim and Toh (Citation2019) also found that a leader’s values have the power to create and shape OC. The study argued that cultures within a group may reflect the values of the leader.

Demographic traits like gender and age are among the frequently studied topics in the literature regarding the creation and changing of the OC (Belias & Koustelios, Citation2014; Chatman & O’Reilly, Citation2016; Kim & Kim, Citation2015). Anderson et al. (Citation2014) found that younger leaders may be more innovative and change-oriented than older leaders due to their tendency for risk-taking and low resistance to change.

4.5.2.3. Cultural transfer perspective

Kim and Toh (Citation2019) found that when leaders are assigned to a new position, they create cultures in their current groups by drawing cultural experience from their prior positions. This means that the leaders brought the cultures of their previous groups into their current organization. For example, if leaders who had experienced tighter or looser cultures in their previous groups brought those cultures into their current position.

4.5.3. Organizational culture orientations

Organizational cultural orientations deal with broader cultural tendencies observed across different groups. Based on the review result, cultural orientations are mainly investigated under four categories, such as workplace orientation, business orientation, system orientation, and group orientation.

Workplace orientation includes attributes like fairness (Kim & Kim, Citation2015), tolerance (Harrington & Gelfand, Citation2014), opportunities for professional growth (Atuahene & Baiden, Citation2018; O’Reilly et al., Citation2014), praise for good performance (Suifan, Citation2021), enthusiasm for the job, being highly organized (Iii et al., Citation2014), being analytically minded (Atuahene & Baiden, Citation2018), and being willing to take risks (Kargas & Varoutas, Citation2015).

Business orientation is characterized by factors like being innovative (Iii et al., Citation2014), results-oriented (Bowers et al., Citation2017), reflective (Iii et al., Citation2014), and operational excellence (Carvalho et al., Citation2023).

System orientation is defined by attributes like individual responsibility (Atuahene & Baiden, Citation2018; Baird et al., Citation2018; Iii et al., Citation2014), having a clear guiding philosophy (Atuahene & Baiden, Citation2018), hierarchical structure (Belias & Koustelios, Citation2014; Bortolotti et al., Citation2015; Kargas & Varoutas, Citation2015), compartment among groups (Saha & Kumar, Citation2018), and clear lines of authority (Atuahene & Baiden, Citation2018; Ramos & Ellitan, Citation2022; Sarhan et al., Citation2020). Group orientation includes teamwork (Hald et al., Citation2020), coordination (Belias & Koustelios, Citation2014), and mutual dependency (Belias & Koustelios, Citation2014; Yaari et al., Citation2019).

4.6. Organizational culture dimensions and cultural orientations

The distinction between ‘organizational culture dimensions’ and ‘organizational cultural orientations’ lies in their scope, focus, and conceptualization within the study of organizational culture. Organizational culture dimensions primarily refer to specific aspects or facets of culture within organizations, often measured through beliefs, norms, behaviors, and interactions among employees. On the other hand, organizational cultural orientations encompass broader cultural tendencies observed across different groups, which may include workplace, business, system, or group orientations.

Organizational culture dimensions, as depicted in the provided paragraphs, delve into the internal dynamics of organizational culture. Researchers often use various dimensions, such as innovation, teamwork, hierarchy, market orientation, and adhocracy to measure and understand organizational culture. These dimensions highlight specific aspects of organizational behavior, norms, and values that shape the overall culture within an organization. For example, studies by Baird et al. (Citation2018) and Suifan (Citation2021) explore dimensions like teamwork, innovation, and market orientation to characterize organizational cultures.

In contrast, organizational cultural orientations take a broader view, examining cultural tendencies across different domains or orientations. Workplace orientation, business orientation, system orientation, and group orientation are examples of such broader categories. These orientations capture overarching cultural traits and values that may influence organizational behavior but extend beyond the confines of individual organizational dynamics. For instance, workplace orientation may encompass attributes like fairness, tolerance, and opportunities for professional growth, as noted by various studies, such as Kim and Kim (Citation2015) and O’Reilly et al. (Citation2014).

In addition, the distinction between dimensions and orientations lies in their levels of specificity and generalizability. Organizational culture dimensions provide a granular understanding of specific cultural elements within organizations, facilitating detailed analysis and measurement. In contrast, organizational cultural orientations offer a broader perspective, allowing researchers to assess cultural trends and tendencies across diverse contexts.

Moreover, while dimensions focus on internal organizational dynamics, orientations acknowledge the influence of broader societal and environmental factors on organizational culture. For instance, system orientation may reflect cultural values related to hierarchical structures and individual responsibility, which could be influenced by societal norms and expectations beyond the organization itself.

5. Discussions

The systematic review revealed a comprehensive overview of the research landscape on organizational culture. Notably, the majority of the studies (87%) employed empirical methods, with quantitative (37%) and qualitative (33%) research being predominant. This indicates a robust foundation for understanding organizational culture based on real-world observations and experiences. The increasing trend in publications since 2018, peaking in 2021 and 2022, suggests a growing scholarly interest in contemporary organizational culture. This surge may be attributed to the evolving nature of work environments and the recognition of organizational culture as a critical factor in organizational success.

The identified organizational culture dimensions reflect the multifaceted nature of this construct. The most frequently used dimensions include innovation culture, teamwork culture, result-oriented culture, masculinity, and involvement, among others. However, the lack of consensus on the inclusion of specific dimensions across studies underscores the complexity and subjectivity in defining organizational culture. The diverse perspectives indicate that organizational culture is a nuanced concept influenced by various factors and is open to interpretation.

The functionality perspective emphasizes environmental factors as primary drivers of organizational culture. The findings highlight the impact of external threats, market changes, rules and regulations, industry characteristics, and technology on shaping organizational cultures. Notably, the recent investigation into the effects of events like the COVID-19 pandemic on organizational cultures reflects the dynamic nature of these influences. The findings underscore the adaptive nature of organizations, aligning their cultures with external challenges and opportunities.

The leader-trait perspective provides valuable insights into how leadership qualities, including personality, values, and demographic attributes, contribute to organizational culture. CEOs, in particular, emerge as pivotal figures whose traits shape organizational values and behaviors. This perspective emphasizes the influential role of leaders in setting the tone for organizational culture, reinforcing the idea that leadership is a crucial factor in cultivating a desired organizational culture.

The cultural transfer perspective introduces the idea that leaders bring cultural experiences from their previous positions, impacting the culture of their current organization. This highlights the interconnectedness of organizational cultures across different contexts and the role of leadership transitions in cultural continuity or change. Understanding these dynamics is essential for organizations seeking to manage and leverage cultural transfer during leadership transitions.

The identified cultural orientations—workplace, business, system, and group orientations—offer a nuanced understanding of the diverse aspects contributing to organizational culture. Workplace orientation, encompassing fairness, tolerance, and opportunities for professional growth, reflects the employee-centric aspects of organizational culture. Business orientation emphasizes innovation and results, aligning organizational culture with strategic goals. System orientation highlights the structural and hierarchical aspects, while group orientation underscores the importance of teamwork and collaboration.

In sum, the findings from the systematic review, offer a deeper understanding of organizational culture’s dimensions, perspectives, and orientations. The nuanced insights provided pave the way for further exploration and application in both academic and practical contexts.

6. Implications

The implications derived from this systematic review significantly contribute to advancing the practical, theoretical, and methodological understanding of recent OC publications. Our study not only evaluates the present state of OC but also provides insights into emerging trends, addressing a critical gap in the existing literature. To enhance the content, we explicitly emphasize the need for future research endeavors to delve deeper into specific areas uncovered in our review, fostering a more nuanced understanding of the complexities within organizational culture and laying the groundwork for more targeted investigations.

On a practical level, our research assumes a crucial role in aiding organizations in decision-making processes related to their cultural dynamics. By elucidating key aspects of OC, our findings empower managers to make informed choices, contributing to the development of robust organizational culture strategies. In response to the comments received, we have further emphasized the practical implications of our work, illustrating its immediate relevance and applicability in real-world organizational contexts.

Furthermore, our study now places a heightened emphasis on the managerial understanding of organizational culture, illustrating how our findings can stimulate firms to proactively formulate and implement effective OC strategies. By incorporating this emphasis, our manuscript encourages organizations to not only recognize the importance of culture but also to actively engage in cultivating and adapting their cultural framework to align with evolving needs and objectives.

In addition to these refinements, our systematic review now provides an enriched exploration of how culture is created and changed within organizations. This nuanced analysis delves into the underlying mechanisms and drivers, shedding light on the dynamic processes that shape and reshape organizational culture over time.

7. Conclusion

In undertaking this comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of OC, we have endeavored to provide a nuanced understanding of critical factors pertaining to OC. Spanning a broad time range from 2014 to 2023, our review draws from a diverse array of databases and journals, underscoring the thoroughness of our exploration. Our commitment to methodological rigor is evident in the systematic approach applied to literature selection and analysis, enhancing the credibility of our findings and contributing to the reliability of the insights presented.

By addressing the fragmentation in organizational culture literature, our study represents a novel contribution, updating the field since the last major review. Our key findings illuminate the profound impact of OC on employee behavior, workplace dynamics, and organizational treatment. Noteworthy OC dimensions, including innovation, teamwork, result orientation, masculinity, involvement, and power distance, emerge as recurrent focal points in the literature.

It is crucial, however, to acknowledge the limitations inherent in our review process and the studies under consideration. Recognizing the potential for biases introduced by the scope of our literature search and the variability in study quality, we remain transparent about these constraints. We encourage readers to interpret our findings with a nuanced understanding of these limitations. Furthermore, we emphasize the practical implications of our study, offering guidance for future research and practice in organizational culture. By systematically addressing gaps and consolidating insights, this review serves as a valuable resource for shaping the trajectory of both scholarly inquiries and practical implementations in the realm of organizational culture.

8. Future research agenda

In recognizing its contributions, this study underscores its limitations and puts forth directions for future research. To further enhance our understanding of OC, it is advisable to integrate existing knowledge, thereby contributing to the development of a more comprehensive OC theory while addressing concerns related to validity and reliability. Avenues for exploration in future studies include delving into diverse cultural structures, resolving challenges associated with leaders’ prior experiences, and incorporating a broader spectrum of cultural contexts.

In building upon the foundation laid by this research, it is crucial for future systematic reviews to identify and address any gaps in the existing literature. Comparative studies, particularly in developing countries, present a promising avenue for expanding awareness and enriching our understanding of OC dynamics. Moreover, investigating the intricate association between OC and financial performance deserves dedicated attention in future research endeavors. By embracing these suggestions, researchers can contribute to the refinement and advancement of our comprehension of organizational culture.

9. Limitations of the study

Despite its strengths, this systematic review has limitations. The exclusion of pre-2014 contributions and the reliance on nine databases and English-language articles limit its scope. The keyword-based search may have missed relevant concepts. Future research can overcome these limitations by broadening search criteria and employing additional databases. Subjectivity in the content analysis could be mitigated using systematic review software tools, such as the recommended ‘Alceste software’.

Author contributions

Addisalem Tadesse Bogale collaborated closely in conceptualizing and structuring the systematic review, actively participating in data analysis and interpretation, providing critical feedback and revisions to enhance clarity and coherence, and sharing accountability for the integrity and accuracy of the research. Kenenisa Lemi Debela conceived and designed the review, including formulating research questions and selection criteria, conducting data analysis, drafting the manuscript, and addressing identified gaps and challenges within the field. Both authors jointly conducted data analysis and interpretation, drafted the paper, and critically revised it. Both authors provided final approval for the published version and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data associated with this manuscript is publicly available and can be accessed through the online database namely: Science Direct, Elsevier, Taylor & Francis, JSTOR, Emerald, Springer, Wiley, SAGE, and Google Scholar. Researchers and interested parties are encouraged to retrieve the data from this repository for further analysis and verification.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Addisalem Tadesse Bogale

Addisalem Tadesse Bogale is currently pursuing a PhD at the Department of Management, College of Business and Economics, Jimma University, Ethiopia. He obtained his Master of Business Administration (MBA) from Jimma University and his Bachelor of Arts degree in Management from Addis Ababa University, both in Ethiopia. With a keen interest in academia, Addisalem has contributed significantly to scholarly discourse, having published 11 articles in international journals. Additionally, he has shared his expertise by teaching management courses at Ambo University’s Woliso campus, alongside various private universities and colleges.

Kenenisa Lemi Debela

Dr. Kenenisa Lemi Debela is an Associate Professor of Management at Jimma University, College of Business and Economics, Department of Management. Dr. Kenenisa pursued his BA degree in Accounting and Finance and Masters of Business Administration (MBA) from Jimma University in 2006 and 2010 respectively and PhD in Management Studies from Punjabi University, India in 2016. Dr. Kenenisa Lemi is engaging in teaching and learning, research and community service endeavors. He Publish 41 articles at National and International Journals. Dr. Kenenisa was engaging in administrative activities as head of the department of Accounting and Finance, Ethics officer, Vice Dean, Dean of the College of Business and Economics and Vice President for Administration and Students’ Affairs of Jimma University. Dr. Kenenisa is a coordinator and Co-PI for SUSTAIN Project, a collaborative project between Jimma University, Mizumbe University and Norwegian Business School.

References

- Abdalla, W., Suresh, S., & Renukappa, S. (2020). Managing knowledge in the context of smart cities: An organizational cultural perspective. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 16(4), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.7341/20201642

- Ahn, H. J., & Hee, S. (2019). Relationship between organizational culture and job satisfaction among Korean nurses: A meta-analysis. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing Administration, 25(3), 157–166. https://doi.org/10.11111/jkana.2019.25.3.157

- Akhavan, P., Sanjaghi, M. E., Rezaeenour, J., & Ojaghi, H. (2014). Examining the relationships between organizational culture, knowledge management and environmental responsiveness capability. VINE, 44(2), 228–248. https://doi.org/10.1108/VINE-07-2012-0026

- Albayrak, G., & Albayrak, U. (2014). Organizational culture approach and effects on Turkish construction sector. APCBEE Procedia, 9, 252–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcbee.2014.01.045

- Alvesson, M. (2002). Understanding organizational culture. SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Anderson, N., Potočnik, K., Zhou, J., Potocnik, K., & Zhou, J. (2014). Innovation and creativity in organizations: A state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1297–1333. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527128

- Atuahene, B. T., & Baiden, B. K. (2018). Organizational culture of Ghanaian construction firms. International Journal of Construction Management, 18(2), 177–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2017.1301043

- Azeem, M., Ahmed, M., Haider, S., & Sajjad, M. (2021). Technology in Society Expanding competitive advantage through organizational culture, knowledge sharing and organizational innovation. Technology in Society, 66(June), 101635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101635

- Bagga, S. K., Gera, S., & Haque, S. N. (2022). The mediating role of organizational culture: Transformational leadership and change management in virtual teams. Asia Pacific Management Review, 28(2), 120–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2022.07.003

- Baird, K., Su, S., & Tung, A. (2018). Organizational culture and environmental activity management. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(3), 403–414. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2006

- Belay, H. A., Hailu, F. K., & Sinshaw, G. T. (2023). Linking internal stakeholders’ pressure and corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices: The moderating role of organizational culture. Cogent Business & Management, 10(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2229099

- Belias, D., & Koustelios, A. (2014). Organizational culture and job satisfaction: A review. International Review of Management and Marketing, 4(2), 132–149.

- Bhuiyan, F., Baird, K., & Munir, R. (2020). The association between organisational culture, CSR practices and organisational performance in an emerging economy. Meditari Accountancy Research, 28(6), 977–1011. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-09-2019-0574

- Bilan, S., Šuleř, P., Skrynnyk, O., Krajňáková, E., & Vasilyeva, T. (2022). Systematic bibliometric review of artificial intelligence technology in organizational management, development, change and culture. Business: Theory and Practice, 23(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3846/btp.2022.13204

- Binder, C. (2016). Integrating organizational-cultural values with performance management. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 36(2–3), 185–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/01608061.2016.1200512

- Bortolotti, T., Boscari, S., & Danese, P. (2015). Successful lean implementation: Organizational culture and soft lean practices. International Journal of Production Economics, 160, 182–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2014.10.013

- Bosire, D. O., & Kinyua, G. M. (2022). Industry structure as an antecedent of organizational performance: A review of literature. The International Journal of Business & Management, 10(4), 136–148. https://doi.org/10.24940/theijbm/2022/v10/i4/BM2204-021

- Bowers, M. R., Hall, J. R., & Srinivasan, M. M. (2017). Organizational culture and leadership style: The missing combination for selecting the right leader for effective crisis management. Business Horizons, 60(4), 551–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2017.04.001

- Bukoye, O. T., & Abdulrahman, A. H. (2022). Organizational culture typologies and strategy implementation: Lessons from Nigerian local government. Policy Studies, 44(3), 316–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2022.2051467

- Büschgens, T., Bausch, A., & Balkin, D. B. (2013). Organizational culture and innovation: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30(4), 763–781. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12021

- Bwonya, J. E., Martin, O., & Okeyo, W. O. (2020). Leadership style, organizational culture and performance: A critical literature review. Journal of Human Resource & Leadership, 4(2), 48–69.

- Cameron, K. S., & Quinn, R. E. (2006). Mechanism of recombinant human growth hormone accelerating burn wound healing in burn patients. Chinese Journal of Burns, 16(1), 22–25.

- Carvalho, A. M., Sampaio, P., Rebentisch, E., McManus, H., Carvalho, J. Á., & Saraiva, P. (2023). Operational excellence, organizational culture, and agility: Bridging the gap between quality and adaptability. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 34(11–12), 1598–1628. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2023.2191844

- Cascio, W. F., & Montealegre, R. (2016). How technology is changing work and organizations. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 3(1), 349–375. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-041015-062352

- Chang, C. L., Hsing., & Lin, T. C. (2015). The role of organizational culture in the knowledge management process. Journal of Knowledge Management, 19(3), 433–455. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-08-2014-0353

- Chatman, J. A., & O’Reilly, C. A. (2016). Paradigm lost: Reinvigorating the study of organizational culture. Research in Organizational Behavior, 36, 199–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2016.11.004

- Cicea, C., Țurlea, C., Marinescu, C., & Pintilie, N. (2022). Organizational culture: A concept captive between determinants and its own power of influence. Sustainability, 14(4), 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042021

- Cooke, R. A., & Rousseau, D. M. (1988). Behavioral norms and expectations: A quantitative approach to the assessment of organizational culture. Group & Organization Studies, 13(3), 245–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/105960118801300302

- Cortes, S., Andres, M., Cortes, F., & Herrmann, P. (2021). Sharing strategic decisions: CEO humility, TMT decentralization, and ethical culture. Journal of Business Ethics, 178(1), 241–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04766-8

- Dai, J., Chan, H. K., & Yee, R. W. Y. (2018). Examining moderating effect of organizational culture on the relationship between market pressure and corporate environmental strategy. Industrial Marketing Management, 74(June 2017), 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2018.05.003

- Denison, D. R. (1990). Corporate culture and organizational effectiveness. In Corporate culture and organizational effectiveness (pp. xvii, 267–xvii, 267). John Wiley & Sons.

- Denison, D. R., & Mishra, A. K. (1995). Toward a theory of organizational culture and effectiveness. Organization Science, 6(2), 204–223. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.6.2.204

- Denison, D. R., Mishra, A. K., Science, O., & Apr, N. M. (2015). Toward a theory of organizational culture and effectiveness toward a theory of organizational culture and effectiveness. Organization Science, 6(2), 204–223. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.6.2.204

- Denison, D., Nieminen, L., & Kotrba, L. (2012). Diagnosing organizational cultures: A conceptual and empirical review of culture effectiveness surveys. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(1), 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2012.713173

- Deyner, D., & Tranfield, D. (2009). Producing a systematic review. In D. A. Buchanan & A. Bryman (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational research methods (pp. 671–689). Sage Publications Ltd.

- Elsbach, K. D., & Stigliani, I. (2018). Design thinking and organizational culture: A review and framework for future research. Journal of Management, 44(6), 2274–2306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317744252

- Galea, N., Powell, A., Loosemore, M., & Chappell, L. (2020). The gendered dimensions of informal institutions in the Australian construction industry. Gender, Work & Organization, 27(6), 1214–1231. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12458

- Gelfand, M. J., & Erez, M. (2017). Cross-cultural industrial organizational psychology and organizational behavior: A hundred-year journey. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 514–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000186

- Githuku, G. K., Kinyua, G., & Muchemi, A. (2022). Learning organization culture and firm performance: A review of literature. International Journal of Managerial Studies and Research, 10(2), 38–50. https://doi.org/10.20431/2349-0349.1002005

- Groysberg, B., Lee, J., Price, J., & Cheng, J. Y. (2018). The leader’s guide to corporate culture: how to manage the eight critical elements of organizational life. Harvard Business Review, 96, 44–52.

- Hald, E. J., Gillespie, A., & Reader, T. W. (2020). Causal and corrective organisational culture: A systematic review of case studies of institutional failure. Journal of Business Ethics, 174(2), 457–483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04620-3

- Hällgren, M., Rouleau, L., & Rond, M. de. (2018). A matter of life or death: How extreme context research matters for management and organization studies. Academy of Management Annals, 12(1), 111–153. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2016.0017

- Hardcopf, R., Liu, G. (.,)Jason, R., Shah, G., & R., Shah. (2021). Lean production and operational performance: The influence of organizational culture. International Journal of Production Economics, 235(March 2020), 108060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2021.108060

- Harrington, J. R., & Gelfand, M. J. (2014). Tightness-looseness across the 50 united states. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(22), 7990–7995. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1317937111

- Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014

- Hogan, S. J., & Coote, L. V. (2014). Organizational culture, innovation, and performance: A test of Schein’s model. Journal of Business Research, 67(8), 1609–1621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.09.007

- Hosseini, S. H., Hajipour, E., Kaffashpoor, A., & Darikandeh, A. (2020). The mediating effect of organizational culture in the relationship of leadership style with organizational learning. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 30(3), 279–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2019.1680473

- Hussain, I., Mujtaba, G., Shaheen, I., Akram, S., & Arshad, A. (2022). An empirical investigation of knowledge management, organizational innovation, organizational learning, and organizational culture: Examining a moderated mediation model of social media technologies. Journal of Public Affairs, 22(3), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2575

- Iii, C. A. O. R., Caldwell, D. F., Chatman, J. A., & Doerr, B. (2014). The promise and problems of organizational culture: CEO personality, culture, and firm performance. Group & Organization Management, 39(6), 595–625. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601114550713

- Ipinazar, A., Zarrabeitia, E., Maria, R., Belver, R., & Martinez-de-Alegría, I. (2021). Organizational culture transformation model: Towards a high performance organization. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management, 14(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.3926/jiem.3288

- Isensee, C., Teuteberg, F., Griese, K., & Topi, C. (2020). The relationship between organizational culture, sustainability, and digitalization in SMEs: A systematic review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 275, 122944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122944

- Jabo, D. N. (2021). Assessing the interdependence between organizational culture and performance in the construction industry. Management Knowledge and Learning, 20, 79–87.

- Ju, B., Lee, Y., Park, S., & Yoon, S. W. (2021). A meta-analytic review of the relationship between learning organization and organizational performance and employee attitudes: Using the dimensions of learning organization questionnaire. Human Resource Development Review, 20(2), 207–251. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484320987363

- Kargas, A. D., & Varoutas, D. (2015). On the relation between organizational culture and leadership: An empirical analysis. Cogent Business & Management, 2(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2015.1055953

- Kim, H., & Kim, J. (2015). A cross-level study of transformational leadership and organizational affective commitment in the Korean local governments: Mediating role of procedural justice and moderating role of culture types based on competing values framework. Leadership, 11(2), 158–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715013514880

- Kim, T., Chang, J., & Kim, T. (2019). Organizational culture and performance: A macro-level longitudinal study. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 40(1), 65–84. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-08-2018-0291

- Kim, Y. J., & Toh, S. M. (2019). Stuck in the past? The influence of a leader’s past cultural experience on group culture and positive and negative group deviance. Academy of Management Journal, 62(3), 944–969. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.1322

- Kim, Y. J., Toh, S. M., & Baik, S. (2022). Culture creation and change: Making sense of the past to inform future research agendas. Journal of Management, 48(6), 1503–1547. https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063221081031

- Kunisch, S., Menz, M., & Ambos, B. (2015). Changes at corporate headquarters: Review, integration and future research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 17(3), 356–381. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12044

- Latta, G. F. (2020). A complexity analysis of organizational culture, leadership and engagement: Integration, differentiation and fragmentation. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 23(3), 274–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2018.1562095

- Lau, P. Y. Y., McLean, G. N., Hsu, Y. C., & Lien, B. Y. H. (2017). Learning organization, organizational culture, and affective commitment in Malaysia: A person-organization fit theory. Human Resource Development International, 20(2), 159–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2016.1246306

- Lawton, T. C., Rajwani, T., & Minto, A. (2017). Why trade associations matter: Exploring function, meaning, and influence. Journal of Management Inquiry, 27(1), 5–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492616688853

- Le, H. M., Nguyen, T. T., & Hoang, T. C. (2020). Organizational culture, management accounting information, innovation capability and firm performance. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1857594. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1857594