Abstract

This article suggests social entrepreneurship, driven by the focal point of Social Entrepreneurship Orientation, as a mechanism to safeguard the cultural heritage of George Town, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, through the case study of two entities - a legally registered organisation (ORG01) and an informal group (ORG02). Given the complex mechanism of social entrepreneurship, this study employed a qualitative approach utilising the Theory of Change framework to dissect the intricated aspects of social entrepreneurship initiatives into processes and challenges, focusing on inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes, and impacts. The key findings shed light on the roles of two entities embodying the characteristics of Social Entrepreneurship Orientation in their safeguarding efforts. Lastly, this article contributes to a practical understanding and possible development of a sustainable model for cultural heritage safeguarding by comprehending the social entrepreneurship process and aligning with Sustainable Development Goal 11 of fostering sustainable cities and communities.

1. Introduction

Historically, George Town became the intersection of multicultural society when it was turned into a free trading port by the British East India Company (Penang Port Commission, Citation2023; Jackson, Citation2013). Referring to , George Town, Penang is strategically positioned between China and the Indian subcontinent and served as a crucial commercial port for the British, facilitating trade and commerce between these two significant regions (Zhao et al., Citation2019).

Figure 1. Map Showing George Town’s Strategic Positioning between China and India. Note: The red circle highlights the geographic location of George Town, Penang, on the map. Source: Google Maps. (n.d.) (https://www.google.com/maps/@13.6960393,101.5092679,5z?entry = ttu).

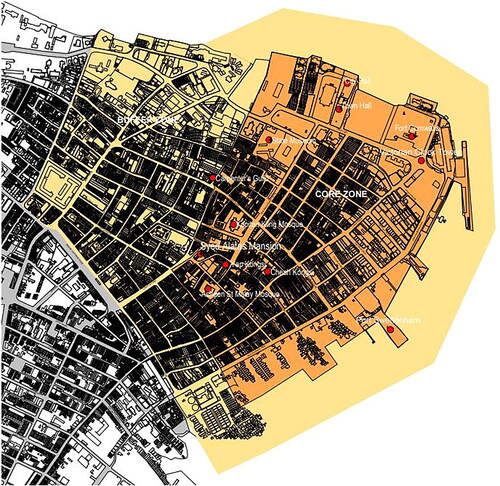

As an initiative to develop George Town, the British encouraged more settlers by allowing them to claim as much land as they could clear (Penang Port Commission, Citation2023). This has triggered a large wave of immigration from China and India to Malaya. Besides tangible items, the settlers also brought their intangible cultural heritage. It is indisputable that Penang possesses a unique cultural heritage where many religions and cultures meet and coexist due to the influences of British colonisation and mass emigration. As a result, George Town was awarded the UNESCO World Heritage Site (WHS) title in conjunction with Melaka on 7th July 2008 for having Outstanding Universal Values (OUVs); the title intends to preserve the cultural heritage for future generations (UNESCO, Citation2019). shows that 259.42 hectares in George Town fall under the Buffer and Core Zone (UNESCO, Citation2007). The inscription encloses the Core Zone and Buffer Zone, which surrounds and protects the Core Zone, ensuring holistic preservation of the heritage site (UNESCO, Citation2007).

Figure 2. Map of core and buffer zones of the historic city of George Town. Note: The dark orange area represents the Core Zone, covering 109.38 hectares, while the light orange area represents the Buffer Zone, covering 150.04 hectares. Source: UNESCO, Citation2007 (https://whc.unesco.org/en/documents/101085/).

Following the inscription, tourism in George Town UNESCO World Heritage Site (GTWHS) has boomed, and it has since gained attention from many stakeholders. Tourism-related activities contribute significantly to Penang’s economy and turn Penang into a bustling island (Ong, Citation2022). Even though the COVID-19 pandemic slowed the tourism sector, it is on a rebounding trend (Mok, Citation2023; Bernama, Citation2023; Solhi, Citation2021). Indisputably, the WHS title did more than promote and lift Penang to international status. However, it also protected the tangible cultural heritage (TCH), such as built heritage within the GTWHS, from being demolished to make room for high-rise and modernised buildings (Kaur, Citation2019). Unfortunately, there are some harmful effects from the listing, specifically on the intangible cultural heritage (ICH) – indirectly and unintentionally changes the social fabric in GTWHS, causing mass exodus and ceasing of traditional businesses (Foo & Krishnapillai, Citation2018; Teoh, Citation2018; Barron, Citation2017). After the exodus process, built heritage is often turned into hotels and cafes to cater to tourism-related activities with little to no elements of ICH attached as the living cultural heritage has taken them along during the exodus process. Apart from that, the property prices for the built heritage are constantly increasing, plus the prohibitive cost with tons of guidelines on upkeeping; those unable to sell or rent will eventually be abandoned and left to rot (Lo, Citation2020). Based on the latest official report by Penang Island City Council (MBPP) in 2020, there are reportedly 73 units of abandoned built heritage within GTWHS (Lo, Citation2020). Moreover, time-related factors, including globalisation, inflation, and social cohesion, threaten GTWHS’s cultural heritage in the long term.

Globally, it is a known fact that safeguarding cultural heritage is a long-term process that requires a constant flow of funds (Mekonnen et al., Citation2022; UNESCO, Citation2016). Nevertheless, one of the many obstacles in the safeguarding process is the need for more funds. Sadly, the dying of cultural heritage does not rank as a present issue requiring immediate action; thereby, it is less likely to receive enough attention and funding from the government and private sector. Governments have a statutory responsibility to provide funds to safeguard the cultural heritage, but with the shrinking of finances and increase in social issues, there is a gap left unmet. Factors such as inflation make safeguarding cultural heritage costs skyrocket, especially the cost of preserving built heritage. As Mohd Nawi et al. (Citation2020) mentioned, the risks and costs in conserving and preserving built heritage are higher and often more complicated given the rigid set of guidelines to maintain the built heritage’s authenticity. The disappearance of cultural heritage is viewed as a social issue because cultural heritage is a valuable shared asset that reflects past generations’ human legacy (Mekonnen et al., Citation2022; Harvey, Citation2019). Besides, safeguarding cultural heritage receives less attention and funds than other contemporary issues in sectors such as health, education, and environment (Singh & Lee, Citation2023; British Council, Citation2018); these sectors are deemed more vital.

For the past few decades, social entrepreneurship has emerged as a mechanism to accomplish social change by bridging gaps unmet by the government and private sector. Establishing social enterprises comes with the main aim of addressing targeted social and environmental issues. For instance, Hong Kong has proved that social entrepreneurship is an effective mechanism to safeguard cultural heritage through the revitalisation of abandoned built heritage, such as the Old Tai O Police Station and Lai Chi Kok Hospital, into a heritage hotel and an institution that operates as social enterprises and promoting of the Chinese Culture (CHO, Citation2022; JTIA, 2021; Chung, Citation2012). Therefore, social entrepreneurship is anticipated to positively impact the efforts of safeguarding the cultural heritage of GTWHS as it is proven that social entrepreneurship activities can solve contemporary social and environmental issues (Dickel et al., Citation2020; Zhang & Li, Citation2017; Dacin et al., Citation2010; Dees et al., Citation2001).

Given social entrepreneurship’s complex yet ambiguous circumstances, this article seeks to understand its process in the context of GTWHS. Although social entrepreneurship is practised widely, there is neither a core business model nor a unifying definition to pin down the term. Besides, Malaysia’s lack of a legal framework for social enterprise does not stop organisations and groups from working to safeguard GTWHS’s cultural heritage. Social entrepreneurship in Malaysia is still in its infancy but gaining traction. This article will analyse case studies of one organisation and one informal group in GTWHS to comprehend the social entrepreneurship process through the lens of Social Entrepreneurship Orientation (SEO) using elements from the Theory of Change (ToC). In this context, this article attempts to fill a research gap by anchoring on the perspective of business management – the role of social entrepreneurship in the effort to safeguard the cultural heritage in GTWHS. Apart from that, there is a lack of (social) entrepreneurship studies in safeguarding the cultural heritage within GTWHS, leaving an under-explored gap. Theoretically, this article also contributes to social entrepreneurship and cultural anthropology literature.

This article is structured into seven main sections: introduction, literature review, research methodology, findings, cross-case analysis, discussion, and lastly, conclusion.

2. Literature review

The lack of resources for safeguarding will threaten GTWHS’s cultural heritage. The disappearance of cultural heritage is a social issue, and this article suggested social entrepreneurship as a mechanism to address this contemporary social issue. First, a literature review on cultural heritage safeguarding and social entrepreneurship will be discussed, followed by SEO, as it helps to create a boundary in the organisations’ and groups’ selection process. Additionally, ToC, alongside the elements, will be discussed to understand the social entrepreneurship process, followed by a discussion of formal and informal groups.

2.1. The importance of cultural heritage safeguarding

Anthropologically, culture represents the shared system of explicit and implicit knowledge within a specific group, while heritage encompasses the cultural aspects transmitted through generations (Pappas & McKelvie, Citation2022; Hudelson, Citation2004). Cultural heritage embodies values, traditions, skills, knowledge, places, artistic expressions, languages, and values that signify a shared relationship within a community.

Established in 1945, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) aims to promote global peace, sustainable development, and human rights (UNESCO, Citation2024). Cultural heritage safeguarding is one of the major focus areas for UNESCO, involving protecting tangible and intangible elements, as it fosters a sense of identity and belonging within communities. Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11.4 emphasises the importance of safeguarding cultural heritage, explicitly targeting preserving cultural and natural heritage (United Nations, Citation2022). Stakeholders should strengthen efforts to safeguard cultural heritage because it contributes to resilience and sustainable development (Hosagrahar, Citation2017). Also, safeguarding cultural heritage is crucial for broader sustainability goals, including economic growth and poverty reduction (UNESCO, Citation2015). Despite UNESCO’s initiative to spearhead the efforts to safeguard cultural heritage through various conventions, it has yet to mitigate the inherent complexities and challenges associated with these safeguarding efforts. Hence, traditional safeguarding is insufficient when facing rapid social change and thereby requires a new adaptation, such as using sustainable mechanisms to safeguard cultural heritage.

This article focuses on understanding the significance of cultural heritage safeguarding within the context of GTWHS. Lastly, through comprehensive analysis, this article provides insights into social entrepreneurship as an effective mechanism for safeguarding cultural heritage.

2.2. The panorama of social entrepreneurship in Malaysia

The practices and contributions of social entrepreneurship may be publicly and widely gaining support and recognition, but the term itself is still trying to achieve validity academically (Karré & Meerkerk, Citation2023). Apart from being vaguely and boundaryless defined, social entrepreneurship also continues to challenge the functional perspective of business and economics with no core business model or specific economic measurement scales (Dickel et al., Citation2020; Weller & Ran, Citation2020; Wu et al., Citation2020; Abu-Saifan, Citation2012). The definition of social entrepreneurship is inconclusive, but the fundamental idea of social entrepreneurship is relatively simple and straight to the point; it is all about doing business and addressing any social issues that are left unsolved by the government and private sectors with its resources such as earned income, knowledge and skills, among others (MECD, Citation2023; Osberg & Martin, Citation2015; Doherty et al., Citation2014). Although social enterprises aim for profitability in the interest of sustainability, the primary goal always lies in addressing societal issues (Osberg & Martin, Citation2015).

Just a decade ago, the concept and activities of social entrepreneurship were hardly known or discussed in Malaysia (Abdul Kadir et al., Citation2019). In the past few years, social entrepreneurship has gained popularity and attracted the attention of many stakeholders, including the government. In 2015, the government recognised the importance of social entrepreneurship towards society and launched the Malaysia Social Enterprise Blueprint, which entailed a three-year strategic roadmap to support the development of social enterprises (DNA, Citation2015). Unfortunately, three years was inadequate for social entrepreneurship to be a self-sustaining sector nor to establish a legal framework to cater to social enterprises; the ambiguity and challenges in social entrepreneurship remain. Therefore, building on the work from 2018, the government launched the Social Entrepreneurship Action Framework 2030 (SEMy2030) in April 2022 to support and spur the development and growth of social entrepreneurship and social enterprise (Galimberti, Citation2022). With the SEMy2030, the Penang state government aspires to grow more social enterprises by 2030 (Moroter, Citation2023). Currently, a social enterprise in Malaysia is neither recognised as a conventional business nor a non-governmental organisation (NGO); instead, organisations can be accredited and formally recognised as one (MECD, Citation2023; Yeow & Ng, Citation2022). Even with the vagueness and challenges, it does not hinder social entrepreneurship activities. According to the data published by the Ministry of Entrepreneur and Cooperatives Development (MECD), there are currently 17 accredited social enterprises that have been operating for more than two years, and 223 more that have been operating for at least six months throughout Malaysia (MECD, Citation2023).

In the Malaysian context, MECD defines social enterprise as a legally registered entity, purpose-driven, and has a financially sustainable business model that aims to tackle social or environmental issues to achieve positive impacts on both the beneficiaries and the economy; these are also the criteria to get accredited (MECD, Citation2023). The most recent data from 2018 indicates an estimation of over 20,000 social enterprises in Malaysia, the number registered under micro, small, and medium enterprises, co-operatives, and NGOs, excluding associations/groups that are not legally registered (Loh, Citation2020; Lee, Citation2019; British Council, Citation2018). While there are over 81,000 registered charitable organisations, such as non-profit organisations (NPOs) and NGOs, there is a lack of coherence, and so far, there is no statutory body that regulates charities – hence, the rules and regulations are still blurry (Yeow & Ng, Citation2022; British Council, Citation2018). As of now, it is unclear how many exact numbers of social enterprises operate without being legally registered or being registered under other legal entities. This is a sign that the social entrepreneurship scenario in Malaysia is thriving, but challenges and ambiguities remain. However, the government recognised the importance of social entrepreneurship activities towards society and the economy and acknowledged the potential for social entrepreneurship to grow. Therefore, the government is working towards addressing the challenges to encourage more social entrepreneurship activities in Malaysia. While the government’s aspiration to encourage more social enterprises is a positive goal, it is crucial to assess the existing challenges faced by entities that carry out social entrepreneurship initiatives and if the framework is compelling enough to achieve this goal. The thriving social entrepreneurship scenario in Malaysia is promising. However, its full potential may remain unrealised without comprehensive data on informal groups. This lack of data hinders the ability to fully grasp the understanding of the social entrepreneurship landscape in Malaysia. In light of these challenges, the subsequent discussion will provide a framework for assessing the characteristics of entities engaged in social entrepreneurship initiatives.

2.3. Social entrepreneurship orientation

SEO is a concept that explains the characteristics of the organisation in practices and decision-making; it evolved from entrepreneurship orientation (EO) (Halberstadt & Spiegler, Citation2018). However, SEO differs from EO as social value creation was the main aim, not financial value creation (Gali et al., Citation2020; Kraus et al., Citation2017). Kraus et al. (Citation2017) established a scale to operationalise SEO with four dimensions, see .

Table 1. Dimensions from SEO.

Halberstadt and Spiegler (Citation2018) and Kraus et al. (Citation2017) mentioned that regardless of which (legal) structures, organisations that possess the characteristics of social entrepreneurship and concurrently operate to address societal issues are to be considered social enterprises. Furthermore, social entrepreneurship activities can be found in all types of organisations, regardless of the (legal) structure, as long the earned income or available resources are used to solve societal and environmental issues. As the number of organisations and groups carrying out social entrepreneurship activities in Malaysia remains vague and needs to be clarified, it impedes and raises many questions regarding which types of activities, business models or organisations should be considered part of the social entrepreneurship spectrum. Therefore, SEO can help create functional boundaries in the selection process based on the focus and scope of organisations and groups contributing to the safeguarding efforts in GTWHS. As argued by Martin and Osberg (Citation2007), it is vital to establish boundaries in social entrepreneurship because the term would be insignificant and meaningless if it is left too wide open; therefore, boundaries are essential. Also, a boundary that is too narrow is deemed meaningless (Wanyoike & Maseno, Citation2021). Therefore, SEO can justify the inclusion of organisations and groups working to safeguard cultural heritage in GTWHS, regardless of their (legal) structure.

On the other hand, applying the lens of SEO in safeguarding efforts goes beyond delineating boundaries in the social entrepreneurship process; it also highlights the significance of each dimension. Social innovativeness is essential in addressing the challenges in safeguarding efforts, emphasising the importance of an organisation’s creative problem-solving skills. Social risk-taking emphasises that an organisation is willing to go the extra mile and accept ambiguities, which is vital in addressing ever-changing issues faced during safeguarding efforts. Simultaneously, social proactiveness urges an organisation to pursue opportunities actively while aligning with the nature of cultural heritage issues. Lastly, socialness emphasises the organisation’s commitment to creating social value by prioritising positive social impacts over financial gain. In the context of GTWHS, SEO provides detailed insights into how organisations, irrespective of their (legal) structures, play a role in safeguarding efforts through social entrepreneurship activities.

2.4. Theory of change

ToC will be used as an underlying framework to study the process of social entrepreneurship. There has yet to be a consensus on how to describe and define a ToC or an exact set of methodologies to utilise it (Davies, Citation2018; Serrat, Citation2017; Vogel, Citation2012). Stein and Valters (Citation2012) broadly defined and summarised ToC into a set of "if…then" statements – if represents a set of intervention(s) and then represents the outcome(s). For instance, if parents continue to teach and speak to their children in Penang Hokkien instead of Mandarin, then the lifespan of Penang Hokkien will be prolonged for generations to come. On the contrary, ToC is narrowly defined and directly linked to positive social change (Ruff, Citation2021; Bacq, Citation2017) - ToC is expected to be used for social impact and change. However, it is not exclusively applicable to only positive social change. There are different definitions for ToC, but the shared core elements are similar. Thus, this makes ToC a very flexible yet methodical model to examine the links between activities and expected outcomes while considering the contexts of the initiative(s). Given the complexity of social issues in which the solutions are often not off-the-shelf, ToC can fragment the social entrepreneurship process and, in parallel, provides comprehensive illustrations on how and why change(s) is expected to occur (Bacq, Citation2017; Serrat, Citation2017; Vogel, Citation2012). ToC comprises multiple key elements; see .

Table 2. Key elements from ToC.

The mapping of ToC is relatively flexible, allowing initiators (or social entrepreneurs) to design, implement and assess the progress effectively (Serrat, Citation2017; Stein & Valters, Citation2012). The ToC model can be presented in various ways, provided that it incorporates the five key elements: inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes and impacts (Bacq, Citation2017; Vogel, Citation2012). Therefore, ToC is a helpful model guiding organisations in navigating the complexity of social problems and developing solutions to solve them (Serrat, Citation2017; Vogel, Citation2012).

In this article, ToC serves as an essential framework for understanding the social entrepreneurship process by offering an organised approach linking activities with expected outcomes(s), particularly in safeguarding the cultural heritage of GTWHS. Safeguarding efforts are complex and multifaceted and often lack readily available solutions (Wagner & Clippele, Citation2023). By utilising ToC, organisations and informal groups engaged in safeguarding efforts can comprehensively analyse the inputs, activities, and outputs, align them with expected outcomes, and ultimately lead to transformative impacts. Lastly, the flexibility of ToC can accommodate the challenges that arise from the safeguarding process, allowing effective and fast planning of initiatives and implementation in the context of GTWHS.

2.5. Formal and informal groups

A formal group, also known as a legally registered organisation, is an entity that is officially recognised by the Malaysian government and operates within the legal framework and regulations. In contrast, an informal group operates collectively and represents an association formed by individuals united by common interests; such a group primarily exists to fulfil its members’ social and psychological needs (Cross, Citation2018; Mullins, Citation2010). Unlike formal organisations, informal groups are generally more adaptable and flexible due to the lack of rigid policies, hierarchical structure and predefined common goals during their formation (Mullins, Citation2010). Due to its flexibility, informal groups can swiftly respond to threats or directional changes, as they are not constrained by official procedures or administrative processes (Cross, Citation2018). This article will explore these two entities and their contributions to social entrepreneurship in the effort to safeguard cultural heritage.

3. Methodology

This article employed qualitative techniques to explore and understand the process of social entrepreneurship within GTWHS. Considering social entrepreneurship’s multifarious complexity, a case study method was employed as deemed appropriate. According to Creswell and Creswell (Citation2018), the case study method enables the acquisition of more affluent and deeper explanations and descriptions of a unique or rare phenomenon. Additionally, Yin (Citation2018) mentioned that case study research is beneficial when investigating a phenomenon within a real-life context, allowing for an in-depth exploration and understanding. The sampling frame is limited to organisations and informal groups safeguarding cultural heritage in GTWHS. Given the relatively small and potentially less publicly recognised population, snowball sampling was employed as the recruitment technique.

The primary data collection for this study occurred between October 2022 and April 2023 and involved conducting interview sessions with key informants representing one organisation and one informal group. Each interview lasted between 60 and 150 minutes. Interviews were conducted face-to-face and through Google Meet. A similar set of open-ended questions was used, focused on the elements of the ToC to examine the social entrepreneurship processes within the organisation and informal group. After obtaining key informants’ consent, interviews were recorded and transcribed for analysis. The analysis involved coding the interview transcripts, generating themes, and subsequently reviewing and refining these themes to explain the social entrepreneurship process in the organisation and the informal group’s efforts in safeguarding cultural heritage. Considering ethical aspects, the name of the organisation and the informal group were anonymised as ORG01 and ORG02, respectively. This measure ensures the privacy and confidentiality of key informants and the entities they represent, aligning with ethical standards in qualitative research.

In this study, one key informant from each entity was interviewed. The decision to interview only one individual from each entity was based on several factors:

Distinctiveness of the Phenomenon: Within GTWHS, social entrepreneurship initiatives represent a relatively unique field, with limited entities actively safeguarding cultural heritage.

Depth of Insight: In qualitative research, the emphasis is placed on gaining in-depth insights rather than broad data collection. This is achieved by concentrating on a single key informant, particularly individuals serving as board members. This approach ensures the capture of perspectives from influential decision-makers and obtains comprehensive insights into social entrepreneurship initiatives and safeguarding efforts within each entity.

Resource Constraints: Considering the limited resources inherent in qualitative research, interviewing multiple key informants from each entity may not be practical. This study optimised resource allocation by selecting one key representative while ensuring the richness and depth of collected data.

Additionally, the cultural and political sensitivities of the key informants were respected throughout the research process. Apart from that, researchers also remained open to feedback from key informants, allowing them to express any concerns about the cultural and political significance of the study, specifically the political implications. Besides, researchers also considered confidentiality; no questions about the financial well-being of the organisation and the informal group were asked unless willingly shared by key informants. These ensured that the research process was conducted ethically, promoting a more inclusive and accurate representation of the complex interactions between the safeguarding efforts and social entrepreneurship within GTWHS.

4. Findings

This section examines the findings derived from exploring one legally registered organisation and one informal group. To reiterate, the inscription of George Town as a UNESCO World Heritage Site has introduced significant changes to its social fabric, posing risks to the survival of cultural heritage and potentially leading to its extinction. In response to this challenge, social entrepreneurship has emerged as a suggested approach to safeguarding cultural heritage, leveraging its ability to address various global social and environmental issues.

4.1. Case study 1: Legally registered organisation (ORG01)

Located inside GTWHS, ORG01 has been established and operated since the 1980s. They are the first NGO that strives to be a committed guardian of cultural and natural heritage in Penang. ORG01 is the first NGO in Penang dedicated to safeguarding the built heritage, even those outside GTWHS; ORG01 played a vital role in advocating for protecting these architectural treasures. Their decade-long campaign succeeded when George Town was awarded the UNESCO WHS title in a joint designation with Melaka. The primary momentum behind ORG01’s initiative to pursue the WHS title was safeguarding built heritages, specifically the clan jetties. However, Peng Aun Jetty and Koay Jetty succumbed to urban development in 2006, 2 years before the UNESCO title award (Liew, Citation2022). Fortunately, the remaining clan jetties are now protected and guided by UNESCO guidelines and criteria. Post-inscription, ORG01 has been clearly articulating their concern about over-tourism that will eventually change the social fabric in GTWHS. ORG01 has been emphasising the need to safeguard cultural heritage in GTWHS; this aligns with its mission to preserve Penang’s cultural heritage and natural heritage and its vision to promote cultural diversity, preserve built heritages, revitalise the inner city and local communities, and encourage sustainable tourism activities. ORG01 continues to be a vanguard of cultural heritage preservation in Penang.

4.1.1. Inputs

A diverse range of inputs represents the resources for ORG01, reflecting typical funding mechanisms for NGOs. ORG01 principally relies on monetary sources such as subscription fees, grants, sponsors and donations - ORG01 sustains itself based on a volunteer-driven structure. As the key informant expressed, "As one of the board members, I do not draw a salary, but I think it is worth to sustain the operation, so we all come in as volunteers to help" (Key Informant 1, Citation2022). Board members serve voluntarily, highlighting the organisation’s commitment to safeguarding cultural heritage over any financial gain. In ORG01, members come from various backgrounds and expertise to help sustain the operation. Apart from its members, ORG01 has significant grassroots support from local communities, scholars and UNESCO officers. ORG01 was founded by a group of culturally aware Penangites (residents of Penang) who were exposed to Western culture and education - a group of same-minded people set it up. Internationally, ORG01 receives support from overseas NGOs, associations, and foundations across Southeast Asia. However, the key informant also mentioned, "This is an NGO, and you are welcome to contribute in any way you can" (Key Informant 1, Citation2022). These contributions will significantly help the organisation achieve its primary goal of safeguarding the cultural heritage in GTWHS.

4.1.2. Activities

ORG01 has been at the vanguard of safeguarding cultural heritage in GTWHS, initiating various activities as an NGO since the 1980s. Currently, built heritages within GTWHS are relatively safe as UNESCO guidelines shield them. The information also affirmed that "For Penang, indeed, we serve as the spokesperson for all heritage-related matters" (Key Informant 1, Citation2022). This grants the organisation the authority to issue official statements and publicly advocate for its stances. ORG01 has been actively protesting and raising awareness about the negative impacts of ominous developments, such as the demolitions of clan jetties to make way for high-rise buildings. ORG01’s commitment to safeguarding built heritage was proved by its decade-long campaign and lobbying for the UNESCO title, showing its dedication to protecting built heritage.

Following the inscription, ORG01 has focused on addressing concerns about over-tourism and its negative impacts on the communities and ICH of GTWHS. This shift has led ORG01 to actively safeguard ICH by adopting various approaches to raise awareness of the importance of ICH. One of the strategies involves organising workshops conducted by traditional artisans, allowing the public to participate and gain insights into the unique cultural heritage of GTWHS and hoping to raise more awareness. Additionally, ORG01 has initiated a praiseworthy effort to encourage the transmission of traditional skills, crafts and knowledge from living cultural heritage practitioners by allowing the public to nominate traditional artisans for the Living Heritage Award. As articulated by the key informant, this initiative aims to “encourage all these skilful artisans to continue their trades, but with one condition – they must pass the skill to the next generation. Without imparting the knowledge, they will not be recognised. This is crucial for the sustainability and continuation of the skills” (Key Informant 1, Citation2022). Recipients of this award receive a fixed amount of money annually. This award expresses appreciation towards the living cultural heritage and, at the same time, incentivises transmitting cultural heritage to the next generation.

Over the years, ORG01 has established a robust local and international network. ORG01 is well-known for its efforts in safeguarding cultural heritage - NGOs from overseas frequently seek guidance and ideas from ORG01, and these relationships are reciprocal. A robust network and partnerships are vital for ORG01. Acknowledging the importance of financial sustainability, ORG01 conducts various cultural and educational programmes open to its members and the public, such as heritage tours, educational talks, and outings. ORG01 has also set up a small corner selling Penang heritage-related merchandise and books in its office and online. Despite its achievements, ORG01 remains committed to its mission of cultural heritage safeguarding.

4.1.3. Outputs

While outputs are typically measurable, ORG01 did not specifically maintain records detailing the number of saved built heritage, the quantity of safeguarded ICH or the number of cultural and educational programs conducted. The key informant stated, "We did not specify which buildings we saved. Instead, we raise funds to restore the building" (Key Informant 1, Citation2022). ORG01 successfully advocated for the revitalisation of built heritage transformed into a fancy restaurant, religious museum, and place of worship. The quantification of ICH is reflected in the number of traditional artisans nominated and awarded by ORG01. The UNESCO title awarded to Penang is also a significant output from ORG01’s activities. Further, numerous immeasurable outputs, such as raised awareness, established networking, and partnerships, have contributed to ORG01’s impact throughout its many years of operation.

4.1.4. Outcomes

ORG01’s outcomes can be categorised into short-term and long-term, ranging from 1 to 3 years and 4 to 6 years, respectively. For the short-term outcomes, ORG01’s cultural heritage tours, educational workshops, and programs are vital in increasing public understanding and curiosity about GTWHS’s cultural heritage, indirectly raising awareness. From its wealth of experience, ORG01 is a source of inspiration for other charitable organisations aiming to embark on the safeguarding journey. As for the long-term outcomes, ORG01 expects increased revitalisation of built heritage and encourages the passing down of more traditional skills and knowledge to future generations.

4.1.5. Impacts

Impacts often unfold gradually, generally taking seven years or more to manifest. Reflecting on ORG01’s activities, for instance, the UNESCO title campaign, the impacts have exceeded the suggested timeline of seven years. Over a decade later, the UNESCO award protected the built heritage and elevated Penang to international status, and it contributed significantly to Penang’s economy. The revitalised built heritage continues to serve its practical purposes while being preserved for future generations. Additionally, the ongoing initiative of the Living Cultural Heritage award ensures the transfer of traditional skills and knowledge to future generations. Finally, the multifaceted initiatives from ORG01 increase awareness and contribute to retaining the unique identities within GTWHS.

4.1.6. Analysis of case study 1

Over the years, ORG01 has functioned as an NGO and embarked on various initiatives, such as advocacy works, public stances and engagements, and awareness campaigns. ORG01 operates on a volunteer-based model and relies on diverse support, including subscription fees, sponsors, grants, and donations. The organisation prioritises sustainability over monetary gains. Established in the 1980s, ORG01 is committed to pursuing its mission and vision by engaging in various activities to maintain the authenticity and historical significance of GTWHS and safeguard its cultural heritage. These efforts have resulted in the UNESCO title awarded to Penang and Melaka, contributing to economic growth through increased tourism and repurposing of built heritage.

However, with the increase in tourism, ORG01 shifted its attention to safeguarding the ICH, considering that the built heritages within GTWHS are relatively safe under the UNESCO guidelines. The Living Cultural Heritage Award ensures that traditional skills, craftsmanship, and knowledge are passed down to the next generation. Aside from that, ORG01 has also established many networks throughout the years and is often asked for guidance and ideas by other NGOs. These relationships are reciprocal, where mutual assistance and benefits exchange occur.

Before the UNESCO inscription, ORG01 realised they needed more than protests to prevent skyscrapers from replacing built heritages. They adjusted their strategies proactively to advocate and lobby for the UNESCO title. Post-UNESCO inscription ORG01 prompted further strategy adjustment due to concern about over-tourism that eventually changed the social fabric within GTWHS. In order to facilitate the transmission of traditional skills and knowledge and simultaneously document the ICH, a group of selected living cultural heritage was given a yearly monetary award and recognition to encourage the passing down of skills.

ORG01 is constantly fighting for a balance between safeguarding cultural heritage and tackling destructive development projects that might harm the cultural heritage within GTWHS. This often involves navigating the delicate terrain of socioeconomic interests due to its dependency on various grants and donations. Lastly, this case study highlights the strategies employed by ORG01 in safeguarding efforts and the adaptability in response to changes and challenges while trying to stay sustainable by embodying the principles of social entrepreneurship.

4.2. Case study 2: Informal group (ORG02)

ORG02 is an informal group established in 2015 by former members of ORG01 in response to their volunteer work. Despite operating outside of the framework of a legal entity in Malaysia, they identified themselves as an NGO, and the public recognised them as such. ORG02 is adopting a social media-orientated approach to reach their expected outcomes: safeguard the OUVs within GTWHS. Cross (Citation2018) mentioned that informal groups, like ORG02, form and evolve naturally, driven by individuals interacting to fulfil common goals, which may align differently with the main objectives of formal organisations. The formation of ORG02 is rooted in the shared goal of safeguarding cultural heritage through advocacy works and addressing heritage-related challenges - usually only within GTWHS. ORG02 focuses more on raising alerts related to built heritage as they express that well-maintained buildings would indirectly and directly contribute to safeguarding ICH - as ICH is typically brought along during the exodus of residents, traditional traders and artisans. Neglecting this risks GTWHS being delisted and the extinction of cultural heritage. Apart from that, ORG02 stresses the importance of safeguarding efforts and respecting the UNESCO listing and is working to steer away from transforming GTWHS into a pro-tourism and pro-development state. Lastly, while recognising the ideal situation of earning income through consultation services, the founders have preferred utilising personal funds to avoid potential obligations, expectations and requirements that may come with external funding, which may jeopardise the expected outcomes of ORG02.

4.2.1. Inputs

As an informal group, ORG02 is financially independent as they do not receive any form of monetary support from its members or the public. ORG02 mainly relies on members who volunteer to diligently monitor and report any illegal renovations or possible (re)development projects that may put built heritage at risk of demolition. This approach is facilitated by modern technology, as emphasised by the key informant, "I have volunteers who take photos around GTWHS. With access to the Internet and various mapping and Geographic Information System (GIS) applications, I can manage ORG02 from anywhere in the world. This allows me to be just as effective, if not more so" (Key Informant 2, Citation2023). These alerts are then disseminated through social media platforms to raise awareness and attention among authorities, journalists, and the general public. Apart from that, ORG02 is also actively collaborating and working with overseas NGOs dedicated to cultural heritage preservation, underlining the significance of networking for acquiring knowledge and skills. ORG02 is still working with ORG01 occasionally to highlight severe heritage-related issues and challenges to reach a broader audience. ORG02 also emphasises community engagement, regularly visiting GTWHS communities to converse with residents, traditional traders and artisans to comprehend their concerns regarding changes in the social fabric due to UNESCO inscription and subsequently sharing these insights on their social media platform. The informant articulated, "Our objective is to bolster awareness in a more impactful manner. Our preference is for increased engagement and support from the authorities and other same-minded NGOs, not financially, but for collaboration and mutual involvement" (Key Informant 2, Citation2023). Additionally, ORG02 welcomes individuals with expertise in architecture, engineering, town planning and heritage conservation to contribute to their initiatives.

4.2.2. Activities

In pursuit of their expected outcomes, ORG02 concentrates on advocacy works and online awareness campaigns. ORG02 firmly believes in reporting any discrepancies and threats within GTWHS to the relevant authorities, if not directly to UNESCO, because early intervention is necessary to mitigate threats and erosion to the cultural heritage. The chain of command for complaints to UNESCO appears intriguing and complex. According to the key informant, "UNESCO does not engage directly with the state government or NGOs. Instead, all communications go through the federal government, disseminating the information to the state government and NGOs" (Key Informant 2, Citation2023). The joint UNESCO WHS listing between George Town and Melaka obligates the federal government to manage all communications. Additionally, UNESCO needed time to examine complaints before reverting or listing any heritage sites or ICH in danger. This complex bureaucratic structure challenged the efficiency of the safeguarding efforts.

Therefore, ORG02 actively exposes potential threats through its role as an informal group—for instance, the Campbell Street Market, one of the oldest markets in Penang with Victorian-style architecture, faces a possible partial demolition to make way for a redevelopment project (Dermawan, Citation2023). To address this threat, ORG02 promptly raised awareness through social media, providing historical contexts of the market and updates to the public. As ORG02 has no authority or power to stop any illegal renovations or demolitions, ORG02 is actively exposing information and activities deemed illegal or unethical that will harm the OUVs in any way.

Besides advocacy, ORG02 organises free workshops for contractors and shares educational videos on appropriate materials and methods to renovate and preserve the built heritage. Other than that, ORG02 also documents ancient tombstones that have been unearthed to pave the way for development projects. ORG02 also shares details of any development projects on its social media platform to increase and attract public attention.

The key informant acknowledges that while most members are pro-heritage conservation, its advocacy efforts focus on individuals, particularly younger audiences, who may still need to know the importance of heritage conservation. Therefore, ORG02 often dissect complex issues into digestible segments before posting anything on its social media platform, intending to capture public interest and draw attention to its concerns. Leveraging the power of social media, ORG02 adopts a methodical approach – according to the key informant, "We utilize social media to its fullest potential, often withholding information to generate interest before unveiling key issues. By gradually building anticipation over several days, we ensure they have maximum impact when we reveal the current concerns" (Key Informant 2, Citation2023).

Besides, ORG02 also actively engages with the community, such as gathering opinions from residents, traditional traders and artisans affected by issues like over-tourism, rising rents, and the impact of increased commercial establishments on their living conditions.

Lastly, operating as an informal group, the range of activities undertaken by ORG02 is flexible and diverse. ORG02 is not constrained by any bureaucratic procedures, thus allowing ORG02 to swiftly adapt and tackle any emerging threats to its group or OUVs.

4.2.3. Outputs

While outputs are usually quantifiable, ORG02 does not systematically keep track of its advocacy works. The key informant stated, "We are so busy moving forward; our documentation is on our social media platforms because we are just always moving forward and switching from project to project" (Key Informant 2, Citation2023). Therefore, the social media platform of ORG02 acts as a means to document and assess its advocacy works and workshops. However, one of the noticeable endeavours but immeasurable output is initiating discussions concerning heritage-related issues with the State Heritage Commissioner of Penang. ORG02 indicates a desire to increase engagements with federal and state governments. Other outputs, such as awareness raised, community engagements, and networking, defy easy quantification.

4.2.4. Outcomes

In the long run, ORG02 anticipates several outcomes beyond immediate advocacy impacts. ORG02 aims to encourage increased responsibility and awareness among the general public through constant advocacy and community engagement to foster a shared commitment to protect cultural heritage. By bringing heritage threats to light, ORG02 seeks to prompt the community, public, authorities, and even international bodies like UNESCO to engage actively in the initiatives and discussions of safeguarding efforts. From that, ORG02 hopes to engage with the relevant authorities to address heritage concerns and to influence the safeguarding policy.

Furthermore, the workshops on using correct materials and methods for built heritage preservation aim to have a long-term impact on ensuring contractors and built heritage owners adopt built heritage-friendly practices - so that the built heritage will be in good condition for many years. Overall, ORG02 expects a snowball effect, where its activities contribute to a cultural shift, fostering a sense of pride and responsibility for safeguarding the cultural heritage - and securing broader support within GTWHS.

4.2.5. Impacts

Although ORG02 is a relatively young informal group and taking into consideration that impacts usually need more than seven years to be seen, its activities have initiated notable changes. ORG02 enable the opinions and voices of the community within GTWHS to be heard and has garnered attention from the public and relevant authorities regarding heritage-related issues. Furthermore, ORG02 has consistently emphasised respecting the UNESCO listing, hoping to influence and increase the safeguarding efforts of various stakeholders. Lastly, the lime plaster workshops conducted by ORG02 are expected to impact the community by enhancing knowledge and skills related to the restoration of built heritage, ensuring proper preservation for many years.

4.2.6. Analysis of case study 2

ORG02 operates as an informal group that distinguishes itself from conventional NGOs or businesses by relying solely on internal means for funding - opting out of any external funding. This funding strategy has enabled ORG02 to be flexible in changing its strategies to address new threats or obstacles without facing bureaucratic constraints - the legal framework does not bind ORG02. Founded in 2015, it is ORG02’s choice and part of its strategy of not legally registering as an NGO or enterprise. The key informant stated that if ORG02 received any external funds, it might go sideways with its expected outcome, as external funding often comes with strings attached. Nevertheless, even without a legal framework and operating primarily through social media, ORG02’s impactful advocacy work is not hindered. The driving of discussions with the State Heritage Commissioner indicates a level of impact. Besides, the lime plaster workshops also contribute to long-term impacts by enhancing knowledge and skills in preserving built heritage.

However, managing heritage sites and safeguarding cultural heritage takes much work, effort and money. For ORG02, the need for more engagements from relevant authorities increased the complexities of the safeguarding efforts; the advocacy work has resulted in some influential stakeholders refusing engagements. The key informant stated that ORG02 is ready to collaborate pro bono, with no cost, with the relevant authorities and governmental agencies to safeguard the cultural heritage within GTWHS.

Advocacy work by ORG02 goes beyond raising awareness; to do advocacy work, it requires in-depth research, knowledge acquisition and evidence collection - this has positioned ORG02 as an expert in cultural heritage preservation. These elements are vital in persuading a diverse range of stakeholders about the importance of cultural heritage and the necessity of its preservation efforts. Without these, all communications and posts from ORG02 risk being dismissed as irrelevant clutters. Besides that, advocacy efforts also extend to influencing politicians, decision-makers, and policymakers to ensure that safeguarding cultural heritage remains a priority on their agenda. While ORG02 faces hurdles and obstacles, its approach and strategy illustrate the significant potential of informal groups in leading impactful advocacy and educational initiatives to safeguard cultural heritage within GTWHS.

5. Cross-case analysis

As presented in below, this cross-case analysis offers comprehensive insights into ORG01 and ORG02 in the safeguarding efforts within GTWHS.

Table 3. Comparative analysis of ORG01 and ORG02.

The above table concisely compares ORG01 and ORG02. It highlights key differences in legal frameworks, funding sources, activities, focus on preservation, collaborations, challenges, outcomes, and strategies for adaptability and sustainability. This cross-case analysis provides insights into how these entities operate and approach cultural heritage safeguarding within GTWHS, showcasing their unique characteristics and strategies.

6. Discussions

Even though ORG01 and ORG02 shared the same expected outcome, they somehow demonstrated different strengths in the four SEO dimensions - social innovativeness, risk-taking, social proactiveness, and socialness.

In terms of cultural heritage safeguarding, ORG01 and ORG02 exhibit innovative approaches in different manners. To ensure the survival of heritage arts, ORG01 inspires traditional artisans and craftsmen to be innovative by encouraging them to transform the end products into arts but still stay within the traditional boundary. For instance, ORG01 encourages traditional shoemakers to turn wooden clogs into various sizes as decorations, as they are no longer a common option for footwear. This strategy not only safeguards the continuity of heritage arts but also reinforces traditional crafts by integrating contemporary themes, such as decorative art - ensuring their relevance in today’s world. Additionally, ORG01 is willing to innovate in community engagements, such as planning to include interactive technology in its heritage workshops to attract more youngsters.

On the other hand, ORG02 demonstrates innovativeness by utilising social media for advocacy work to reach a wider audience. ORG02 displays an innovative use of technology for social impact - their ability to adapt and use contemporary communication channels to reach a broader audience and rally support for safeguarding initiatives; this is particularly relevant in the contemporary digital era, where connectivity and outreach are essential. Even though ORG01 and ORG02 display social innovativeness in their approaches, the degree to which they implement it in their social entrepreneurship initiatives varies.

In the dimension of social risk-taking, ORG01 and ORG02 exhibit opposite traits; this has significantly influenced their ability in safeguarding efforts. ORG01 adopts a risk-averse standpoint by avoiding significant risks in safeguarding initiatives and sustaining its operation. In contrast, ORG02 is a risk-taker, especially obvious in its active advocacy works. One of the main strategies of ORG02 is to disclose misconduct that risks potential backlash and possible redelegation of one of its founders. Therefore, ORG02 demonstrates its willingness and readiness to take risks in advocating for the cause of cultural heritage safeguarding. The risk appetites of ORG01 and ORG02 show the differences in their strategies for addressing challenges and potential outcomes.

As for social proactiveness, ORG01 and ORG02 show distinct approaches. These strategies hold significant implications and present solutions to challenges, thereby influencing the long-term sustainability of their safeguarding initiatives. ORG01 appears to have shifted from a proactive to a more reactive stance due to several challenges the organisation is facing internally. Despite that, ORG01 is willing and planning to change its usual way of conducting workshops and tours to attract younger audiences. Conversely, ORG02 proactively interacts and engages with communities, such as seeking opinions and feelings from residents and traditional artisans about the UNESCO inscription - it is a proactive element in their safeguarding efforts to understand the communities better. It shows that ORG01 and ORG02 navigate differently in this dimension.

The dimension of socialness reveals that ORG01 and ORG02 display dedication to creating social value and staying sustainable simultaneously. ORG01 redirects all its earnings towards meeting its expected outcome. Similarly, ORG02 also exhibits the same commitment, except through internal means to fund its safeguarding efforts. Apart from that, ORG01 and ORG02 show strong networking and partnership; as both key informants mentioned, safeguarding cultural heritage is a collective effort. Thereby, in this sense, networking and partnerships are important. Even though there are differences between the financial models, ORG01 and ORG02 share similar dedications to their social causes.

The dimensions unfold unique insights into how ORG01 and ORG02 represent and enact social entrepreneurship principles in their respective efforts to safeguard cultural heritage within GTWHS. Apart from promoting cultural heritage safeguarding, their safeguarding efforts and initiatives also contribute directly to making GTWHS inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable, which aligns with the spirit of SDG 11: Sustainable cities and communities, specifically 11.4, promoting the conservation of cultural heritage. Hence, their efforts have a broader significance and are beyond the local context of GTWHS.

7. Conclusion

The case studies of ORG01 and ORG02 present insights into the role of social entrepreneurship in safeguarding cultural heritage. Despite their differences in characteristics, both entities exhibit a commitment to their goals, utilising innovative strategies, risk-taking, and proactive approaches to create social value. The ToC framework provides a practical lens for understanding how these entities tackle societal problems like the loss of cultural heritage. However, obstacles related to power dynamics and engagement with authorities hinder their effectiveness – highlighting potential challenges in the social entrepreneurship field. Future research should explore the implications of social entrepreneurship and SEO across diverse organisational structures and contexts, improving discourse and developing sustainable safeguarding models. The fragmented regulatory environment and lack of official data on informal groups with social entrepreneurship initiatives in Malaysia pose challenges for social enterprises, highlighting the need for more supportive policies. This article suggests that integrating SEO principles can enhance and strengthen the role of social entrepreneurship in safeguarding efforts, even beyond formal social entrepreneurship structures. While this study offers insights, its scope is limited, and external factors may influence the applicability of SEO principles. Lastly, despite these limitations, this study provides a fundamental grasp of how social entrepreneurship initiatives contribute to safeguarding efforts within GTWHS through the lens of ORG01 and ORG02, laying the groundwork for practical social entrepreneurship applications for future research.

Authors’ contributions

J.L., J.W.O. and K.A.A. contributed substantially to the conception and design of the work. J.L. is responsible for drafting the manuscript, and J.W.O. and K.A.A. provided support and valuable input during the writing process and supervision throughout the research process. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content, gave final approval for the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring the accuracy and integrity of every component, and committed to appropriately investigating and resolving any questions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author, J.W.O., upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Joey Law

Joey Law is a Ph.D. candidate at the Faculty of Management, Multimedia University, Malaysia, focusing on social entrepreneurship and cultural heritage. She is concurrently enhancing her skills in supply chain management through a professional development program (Weiterbildung) sponsored by the German government. Her experience in multinational organisations significantly enriches both her research and professional development.

Jeen Wei Ong

Ong Jeen Wei is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Management, Multimedia University, Malaysia. He also serves as the Director of Alumni Engagement, Career, and Entrepreneurship Development. Jeen Wei earns his PhD (Management) in Entrepreneurship and Strategic Management. His main research interests include entrepreneurship, strategic management, agriculture business and technology adoption, sustainable issues in management, and small and medium enterprises.

Kamarulzaman Ab. Aziz

Kamarulzaman Ab. Aziz is currently a professor at the Faculty of Business and a member of the Centre of e-Services, Entrepreneurship, and Marketing (CESEM). Before transferring to the current faculty, he was the Deputy Dean (R&D) of the Faculty of Management, and the founding Director of the Entrepreneur Development Centre (EDC), at Multimedia University. He was also the founding president of the AKEPT Young Researchers Circle (AYRC). His research interests include Entrepreneurship, Commercialization, Project Management, Technology and Innovation Management.

References

- Abdul Kadir, M. A. B., Zainudin, A. H., Harun, U. S., Mohamad, N. A., & Che Harun, N. H. A. (2019). Malaysian social enterprise blueprint 2015-2018: What’s next? ASEAN Entrepreneurship Journal, 5(2), 1–19.

- Abu-Saifan, S. (2012). Social entrepreneurship: Definition and boundaries. Technology Innovation Management Review, 2(2), 22–27. https://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/523

- Bacq, S. (2017). Social entrepreneurship exercise: Developing your “Theory of Change. Entrepreneur and Innovation Exchange, 1, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.17919/X9Z96J

- Barron, L. (2017). “UNESCO-cide”: does world heritage status do cities more harm than good?. The Guardian, August 30. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/aug/30/unescocide-world-heritage-status-hurt-help-tourism

- Bernama. (2023). Penang tourism sector sees resilient rebound after borders reopen. Bernama, February 8. https://www.bernama.com/en/business/news.php?id=2162759

- British Council. (2018). The State of Social Entrepreneurship in Malaysia. Pioneers Post (pp. 28–58). https://www.pioneerspost.com/news-views/20190312/malaysia-profit-proves-problematic

- CHO. (2022). Conserve and Revitalise Hong Kong Heritage - Commissioner for Heritage’s Office (9). www.heritage.gov.hk. https://www.heritage.gov.hk/en/about-us/commissioner-for-heritages-office/index.html

- Chung, J. K. H. (2012) Adaptive Reuse of Historic Buildings through PPP A Case Study of Old Tai-O Police Station in HK [Paper presentation]. The 2nd International Conference on Management, Economics and Social Sciences.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative & Mixed Methods Approaches (5th ed.). Sage Publication.

- Cross, D. O. (2018). Impact of informal groups on organisational performance. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management, 6(9), 686-694. https://doi.org/10.18535/ijsrm/v6i9.em04

- Dacin, P. A., Dacin, M. T., & Matear, M. (2010). Social entrepreneurship: Why we don’t need a new theory and how we move forward from here. Academy of Management Perspectives, 24(3), 37–57. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMP.2010.52842950

- Davies, R. (2018). Representing theories of change: technical challenges with evaluation consequences. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 10(4), 438–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439342.2018.1526202

- Dees, J. G., Emerson, J., & Economy, P. (2001). Enterprising Nonprofits: A Toolkit for Social Entrepreneurs. Wiley.

- Dermawan, A. (2023). Heritage advocates not happy over construction of five-storey block within GTWHS | New Straits Times. NST Online, April 5. https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2023/04/896561/heritage-advocates-not-happy-over-construction-five-storey-block-within

- Dickel, P., Sienknecht, M., & Hörisch, J. (2020). The early bird catches the worm: an empirical analysis of imprinting in social entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Economics, 91(2), 127–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-020-00969-z

- DNA. (2015). Malaysia unveils social enterprise blueprint. Digital News Asia, May 14. https://www.digitalnewsasia.com/digital-economy/malaysia-unveils-social-enterprise-blueprint

- Doherty, B., Haugh, H., & Lyon, F. (2014). Social enterprises as hybrid organizations: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 16(4), 417–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12028

- Foo, R., & Krishnapillai, G. (2018). Preserving the intangible living heritage in the George Town World Heritage Site, Malaysia. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 14(4), 358–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2018.1549054

- Gali, N., Niemand, T., Shaw, E., Hughes, M., Kraus, S., & Brem, A. (2020). Social entrepreneurship orientation and company success: The mediating role of social performance. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 160, 120230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120230

- Galimberti, S. (2022). Real commitment needed to achieve SEMy2030 objective. New Straits Times, April 26. https://www.nst.com.my/opinion/columnists/2022/04/792087/real-commitment-needed-achieve-semy2030-objective

- Google Maps. (n.d). Google Maps. Retrieved February 10, 2024, from Google Maps website: https://www.google.com/maps/@13.6960393,101.5092679,5z?entry=ttu

- Halberstadt, J., & Spiegler, A. B. (2018). Networks and the idea-fruition process of female social entrepreneurs in South Africa. Social Enterprise Journal, 14(4), 429–449. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-01-2018-0012

- Harvey, E. (2019). Climate Change and the Loss of Cultural Heritage - UNA-USA. UNAUSA. https://unausa.org/climate-change-and-the-loss-of-cultural-heritage/

- Hosagrahar, J. (2017). Culture: at the heart of SDGs. UNESCO, 1, 12–14. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000248116

- Hudelson, P. M. (2004). Culture and quality: an anthropological perspective. International Journal for Quality in Health Care: journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care, 16(5), 345–346. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzh076

- Jackson, A. (2013). Buildings of empire. In Google Books. OUP Oxford. https://books.google.de/books?id=_Rv7AAAAQBAJ&pg=PA7&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Karré, P. M., & Meerkerk, I. V. (2023). The challenge of navigating the double hybridity in the relationship between community enterprises and municipalities. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 1, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2023.2263772

- Kaur, B. (2019). Clan jetties Unesco listing boon or bane? New Straits Times, July 7. https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2019/07/502201/clan-jetties-unesco-listing-boon-or-bane

- Kraus, S., Niemand, T., Halberstadt, J., Shaw, E., & Syrjä, P. (2017). Social entrepreneurship orientation: development of a measurement scale. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 23(6), 977–997. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-07-2016-0206

- Key Informant 1. (2022). Interview [Face-to-Face]. October 5.

- Key Informant 2. (2023). Interview [Google Meet]. April 14

- Lee, M. (2019). Malaysia: Profit proves problematic. Pioneers post, March 12. www.pioneerspost.com. https://www.pioneerspost.com/news-views/20190312/malaysia-profit-proves-problematic

- Liew, J. X. (2022). Gentrification Harming Clan Jetties Site. The Star Newspaper, November 24. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2022/11/24/gentrification-harming-clan-jetties-site

- Lo, T. C. (2020). Heritage buildings left to rot. The Star, August 20. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2020/08/20/heritage-buildings-left-to-rot

- Loh, J. (2020). Social enterprises in Malaysia – an emerging employment provider. Malay Mail, June 17. https://www.malaymail.com/news/what-you-think/2020/06/17/social-enterprises-in-malaysia-an-emerging-employment-provider-jason-loh/1876306

- Martin, R. L., & Osberg, S. (2007). Social entrepreneurship: The case for definition. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 29–39.

- MECD. (2023). About Social Enterprise. Kuskop.gov.my. https://www.kuskop.gov.my/index.php?r=site/index&id=11&page_id=22&articleid=6839&language=en

- Mekonnen, H., Bires, Z., & Berhanu, K. (2022). Practices and challenges of cultural heritage conservation in historical and religious heritage sites: evidence from North Shoa Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Heritage Science, 10, 2–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-022-00802-6

- Mohd Nawi, N. H., Che Haron, R., & Kamarudin, Z. (2020). Risk cost analysis in Malay heritage conservation project. Planning Malaysia, 18(12), 48–58. https://doi.org/10.21837/pm.v18i12.742

- Mok, O. (2023). Penang’s tourism industry sees strong rebound, expects full recovery by end of 2023. Yahoo! News, March 11. https://malaysia.news.yahoo.com/penang-tourism-industry-sees-strong-024155632.html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAA9eNsM2tjGwONqTlAG_c-0nbO3KT4duC_bqAZqOv2Fmkbu28RJTOnjmVD0-4sAO0PDy_sAhbdVFikwvryH8Dm-PJ3YEMEGlK3mw3dxwqjtuCpn_zzE84L12aUJjJrFl2UvURD3BEEIhed7Lfq1cPro0k3_i8CgMJm7NtcUn1dA_

- Moroter, T. (2023). Penang hopes to grow more social enterprises by 2030. Buletin Mutiara, March 21. https://www.buletinmutiara.com/. https://www.buletinmutiara.com/penang-hopes-to-grow-more-social-enterprises-by-2030/

- Mullins, L. J. (2010). Management and Organisational Behaviour (9th ed., pp. 311–313). Financial Times Prentice Hall.

- Ong, W. L. (2022). Penang’s Economy in the Immediate Post-Pandemic Period: Excelling in a Challenging Environment. Penang Institute. https://penanginstitute.org/publications/issues/penangs-economy-in-the-immediate-post-pandemic-period-excelling-in-a-challenging-environment/#:∼:text=Penang's%20economy%20is%20led%20by%20manufacturing%20and%20tourism%2Drelated%20activities

- Osberg, S., & Martin, R. (2015). Two keys to sustainable social enterprise. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2015/05/two-keys-to-sustainable-social-enterprise

- Pappas, S., & McKelvie, C. (2022). What is culture? Retrieved February 15, 2024, from livescience.com website: https://www.livescience.com/21478-what-is-culture-definition-of-culture.html

- Penang Port Commission. (2023). Penang port commission - history penang port. Penangport.gov.my. https://penangport.gov.my/en/public/history-penang-port

- Rodríguez-Ramírez, A., Zapata-Domínguez, Á., & Ramírez-Plazas, E. (2022). Theoretical analysis of the social entrepreneur’s mode of being. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 1, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2022.2128393

- Ruff, K. (2021). How impact measurement devices act: the performativity of theory of change, SROI and dashboards. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 18(3), 332–360. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRAM-02-2019-0041

- Serrat, O. (2017). Theories of change. In Knowledge Solutions (pp. 237–243). Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-10-0983-9_24#

- Singh, N. B., & Lee, Y. (2023). An analysis of factors affecting malaysia’s youth unemployment rate. International Journal of Management, Finance and Accounting, 4(1), 68–86. https://doi.org/10.33093/ijomfa.2023.4.1.5

- Solhi, F. (2021). Penang tourism industry badly hit | New Straits Times. NST Online, September 10. https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2021/09/725960/penang-tourism-industry-badly-hit

- Stein, D., & Valters, C. (2012). Understanding Theory of Change in International Development. Justice and Security Research Programme, JSRP Paper 1, 3–15. JSRP.

- Teoh, S. (2018). UNESCO listing both a boon and bane for George Town. The Straits Times, January 16. www.straitstimes.com. http://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/unesco-listing-both-a-boon-and-bane-for-george-town

- UNESCO. (2007). UNESCO World Heritage Centre - Document - Melaka and George Town, The inscribed property and the buffer zone of the Historic city of Melaka and George Town. Retrieved February 12, 2024, from Unesco.org website: https://whc.unesco.org/en/documents/101085/

- UNESCO. (2015). Intangible cultural heritage intangible cultural heritage and sustainable development. https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/34299-EN.pdf

- UNESCO. (2016). International funds supporting culture. UNESCO. https://en.unesco.org/protecting-our-heritage-and-fostering-creativity/international-funds-supporting-culture

- UNESCO. (2019). World heritage. UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/pg.cfm?cid=160

- UNESCO. (2024). History of UNESCO. Retrieved February 15, 2024, from Unesco.org website: https://www.unesco.org/en/history

- United Nations. (2022). Goal 11: Sustainable cities and communities. The Global Goals. https://www.globalgoals.org/goals/11-sustainable-cities-and-communities/

- Vogel, I. (2012). Review of the use of “Theory of Change” in international development. In UK Department of International Development (pp. 8–22). UK Department of International Development. https://www.theoryofchange.org/pdf/DFID_ToC_Review_VogelV7.pdf

- Wagner, A., & Clippele, M. S. (2023). Safeguarding cultural heritage in the digital era – A critical challenge. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law - Revue Internationale de Sémiotique Juridique, 36(5), 1915–1923. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-023-10040-z

- Wanyoike, C. N., & Maseno, M. (2021). Exploring the motivation of social entrepreneurs in creating successful social enterprises in East Africa. New England Journal of Entrepreneurship, 24(2), 79–104. https://doi.org/10.1108/NEJE-07-2020-0028

- Weller, S., & Ran, B. (2020). Social entrepreneurship: The logic of paradox. Sustainability, 12(24), 10642. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410642

- Wu, Y. J., Wu, T., & Sharpe, J. (2020). Consensus on the definition of social entrepreneurship: a content analysis approach. Management Decision, 58(12), 2593–2619. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-11-2016-0791

- Yeow, J. Y., & Ng, B.-K. (2022). Empowering and sustaining social enterprises. The Edge Markets, September 6. https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/empowering-and-sustaining-social-enterprises

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case Study Research and applications: Design and Methods (6th ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Zhang, Y., & Li, Y. (2017). A literature review on social enterprise. Research on Modern Higher Education 3. https://doi.org/10.24104/rmhe/2017.03.01006

- Zhao, L., Wong, W. B., & Hanafi, Z. B. (2019). The evolution of George Town’s urban morphology in the Straits of Malacca, late 18th century-early 21st century. Frontiers of Architectural Research, 8(4), 513–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2019.09.001