Abstract

This study examines the effect of Green Human Resource Management (GHRM) practices on the retention of millennial employees in Indonesian technology startups, with an emphasis on the intervening roles of job expectations and self-efficacy. Utilizing Social Exchange Theory (SET) as its theoretical foundation, this study explores how GHRM initiatives influence perceptions of employees’ job expectations and self-efficacy, which in turn affect their intention to remain with the organization. The study’s methodology involved a quantitative analysis of 292 millennial employees’ responses using structural equation modeling (SEM) to examine data from various Indonesian technology startups. The findings indicated a strong positive relationship between GHRM practices and self-efficacy. Additionally, a medium-strength relationship was observed between GHRM practices and both job expectations and employee retention. Contrary to expectations, this study finds that job expectations and self-efficacy do not significantly mediate the relationship between GHRM practices and employee retention, indicating a more complex relationship between factors influencing retention decisions among millennial employees in this context. This study recommends a nuanced strategy for Indonesian technology startups to retain millennial talent through the implementation of GHRM practices.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Indonesia is the fourth most populous country globally (Sukmayadi & Yahya, Citation2020), with an estimated population of approximately 270 million individuals (Worldometer, Citation2024). The growing urban population in Indonesia suggests that public awareness of the need for education and modernization is increasing. According to the World Bank (Citation2024), the urban population is projected to reach 67% of Indonesia’s total population by 2050, an increase from 54% in 2010. Indonesia’s median age is 29.9 years, as estimated for 2024 (Worldometer, Citation2024). These data indicate that roughly half of the population is over 29.9 years old and the other half is under that age. Thus, it can be inferred that a significant portion of the population is in their productive years. Indonesia’s middle economic class is expanding rapidly (Dartanto et al., Citation2020), making it the largest in Southeast Asia.

The data suggest that Indonesia will be characterized by a workforce in the future that will demand diverse and varied forms of employment compared with previous generations. It is imperative for every organization to initiate measures to adapt to these changing requirements and effectively assimilate a skilled workforce from this emerging generation. According to Morrell and Abston (Citation2018), millennials exhibit distinctive attitudes towards work in contrast to other generations. As a result, organizations must adopt tailored compensation and benefit practices to foster motivation and engagement in this demographic. Deloitte (Citation2017) found that 66% of millennials intend to leave their companies within five years, and the financial cost of millennials is estimated to be over $30 billion per year (Adkins, Citation2016).

To mitigate the high turnover rates among millennials, it is crucial for organizations to prioritize job satisfaction (Chavadi et al., Citation2022), work-life balance (Bahar et al., Citation2022; Nabawanuka & Ekmekcioglu, Citation2021), and career advancement opportunities (Ivanovic & Ivancevic, Citation2018). Additionally, providing leadership prospects and fostering an inclusive and supportive work environment is essential (George & Wallio, Citation2017). By concentrating on these factors, organizations can enhance millennial employee retention and unlock their capacity to increase performance and productivity. Due to the growing emphasis on sustainability and environmental responsibility, organizations are increasingly adopting green human resource management (GHRM) as a strategic approach to fulfill their needs (Amrutha & Geetha, Citation2020; Paillé et al., Citation2020) and preferences of millennial employees, while also promoting environmental sustainability (Islam et al., Citation2023). GHRM involves incorporating environmental considerations into various human resource functions including recruitment, training, and performance management.

GHRM has become a strategic response to these expectations and is increasingly being adopted by organizations committed to environmental sustainability (Haddock-Millar et al., Citation2016; Maskuroh et al., Citation2023). GHRM practices, including green training and development, performance appraisal, and rewards, are believed to foster both organizational sustainability and employee retention, particularly among millennial employees (Islam et al., Citation2023; Piwowar-Sulej, Citation2021). However, the relationship between GHRM and millennial retention is complex and multi-faceted (Islam et al., Citation2021; Qadri et al., Citation2022). Some studies suggest that not all GHRM practices directly influence millennial retention (Hassan et al., Citation2021; Islam et al., Citation2021, Citation2023; Qadri et al., Citation2022). The efficacy of these practices may depend on how well they align with millennials’ psychological and physiological job satisfaction. This presents a notable research gap, particularly in understanding the complex influence of job expectations and self-efficacy on the interaction between GHRM practices and employee retention.

This study, grounded in Social Exchange Theory (SET) (Blau, Citation1964; Cook et al., Citation2013), explores the impact GHRM practices on the retention of millennial employees in Indonesian technology startups. SET posits that relationships in the workplace are built on mutual exchanges of rewards and benefits, providing a theoretical foundation for understanding how GHRM practices influence employee behavior and attitudes (Maskuroh et al., Citation2023). Growing evidence suggests that well-managed GHRM practices not only foster environmental responsibility but also enhance employee self-efficacy (Nisar et al., Citation2024). This enhancement, as indicated by Farooq et al. (Citation2022), is essential to empower employees to effectively engage in complex environmental challenges. The millennial generation, known for its vitality and adaptability, often brings about innovative approaches to career culture (Liu et al., Citation2019; Santos, Citation2018). These attributes make millennials particularly responsive to GHRM initiatives aligned with their values and aspirations.

The effectiveness of GHRM practices in retaining millennial employees in the Indonesian context, particularly in the growing sector of technology startups, remains an area ripe for exploration. This backdrop raises a pivotal question that lies at the heart of this study.

RQ1: How do GHRM practices influence job expectations, self-efficacy, and employee retention among millennial employees in Indonesian technology startups?

RQ2: How do job expectations and self-efficacy individually contribute to millennial employee retention in Indonesian technology startups?

RQ3: How do job expectations and self-efficacy mediate the relationship between GHRM practices and employee retention among millennials in Indonesian technology startups?

By examining GHRM through the lens of SET, this study aims to bridge the research gap by understanding how GHRM influences millennial employee retention, specifically in the dynamic context of Indonesian technology startups. This study investigated the potential roles of job expectations and self-efficacy as mediators in this relationship. This approach provides valuable insights into the interaction of these factors and their collective impact on employee retention, a crucial aspect for the sustainability and success of organizations in today’s workforce

In the second section, we explore the theoretical foundation, specifically focusing on SET, and the development of hypotheses for each aspect of the research. This section connects the underlying theoretical principles with the specific hypotheses that guide the empirical investigation. The third section of the research provides a detailed description of the study’s design, encompassing the methodology employed to investigate the hypotheses. This section is crucial because it outlines the approach taken to collect and analyze data, ensuring that the research is conducted systematically and rigorously. In the fourth section, we present an in-depth statistical analysis using the SmartPLS 4. This analysis is critical for testing the hypotheses and drawing conclusions based on the empirical data. This section presents a comprehensive examination of the results and provides insights into the relationships and effects identified in this study. The fifth section encompasses a discussion on each of the hypothesis. This section interprets the findings and connects them to the theoretical framework and the existing literature. The concluding section summarizes the key findings, implications, and limitations of this study.

2. Literature review

2.1. Social exchange theory (SET)

SET is a concept widely used in organizational behavior and human resource management (Blau, Citation1964), and posits that relationships are built on the reciprocal exchange of rewards and benefits. In the context of our model, this theory provides a valuable lens through which to view the interactions between employers and employees (Chernyak-Hai & Rabenu, Citation2018), particularly in terms of GHRM practices. Under SET, GHRM implementation can be seen as an organizational effort that goes beyond mere compliance with environmental standards or regulatory requirements (Aboramadan et al., Citation2021). This represents a significant investment in employee welfare and the global good, which can be perceived by employees as a beneficial and valuable initiative. In return, employees can reciprocate with increased loyalty, commitment, and desire to remain with the organization, thereby enhancing retention rates (Ekowati et al., Citation2023). This reciprocal exchange is central to understanding why GHRM may positively impact employee retention (Maskuroh et al., Citation2023).

SET can also explain the mediating role of job expectations and self-efficacy in this model. When an organization invests in GHRM practices (Khalifa Alhitmi et al., Citation2023), it sets certain expectations among employees regarding their role and the company’s commitment to sustainability. Fulfilling these expectations can lead to a positive exchange relationship in which employees feel that their needs and values are respected and met (Afsar et al., Citation2020). Similarly, enhancing employees’ self-efficacy through GHRM initiatives can be viewed as an investment in their personal and professional development (Tang et al., Citation2018), leading to a reciprocal increase in their engagement and commitment to the organization. SET provides a robust theoretical baseline for our model, explaining how the reciprocal nature of employer-employee relationships shaped by GHRM practices, job expectations, and self-efficacy can lead to enhanced employee retention, particularly within the millennial cohort. This theory emphasizes the importance of mutual benefits and reciprocity in organizational practices and employee responses (Meira & Hancer, Citation2021).

2.2. Hypothesis development

2.2.1. The effect of GHRM on employee retention

Research has increasingly emphasized that the millennial workforce, characterized by its unique values and preferences in the workplace, displays a pronounced inclination towards organizations that prioritize sustainability and environmental responsibility (Hassan et al., Citation2021; Islam et al., Citation2023; Qadri et al., Citation2022). The influence of generational change is essential in assessing the efficiency of GHRM in retaining millennial employees. Millennials, compared to previous generations, have consistently demonstrated a strong preference for workplaces that provide opportunities for growth and development while also aligning with their ethical and environmental values (Hershatter & Epstein, Citation2010; Weber, Citation2017). This generation is characterized by a heightened awareness of global issues, such as climate change and sustainability, which impact their choices and loyalty towards employers. GHRM practices, including initiatives such as green training, development programs that focus on sustainability, and the implementation of environmentally friendly policies and practices in the workplace resonate with these values (Islam et al., Citation2023; Maskuroh et al., Citation2023). These practices are not just superficial additions, but are deeply integrated into the strategic implementation of business operations, signaling a genuine commitment to environmental stewardship. The emphasis on green practices within an organization fosters a sense of purpose and fulfillment among millennial employees (Aboobaker et al., Citation2020). When they see their employers actively contributing to environmental sustainability, they reinforce their belief in the organization’s role in societal betterment (Catano & Hines, Citation2016). This alignment of personal and organizational values is crucial for enhancing job satisfaction and loyalty among millennials, thereby reducing their propensity to seek employment opportunities. The adoption of GHRM practices, therefore, has become a strategic tool not only in attracting millennial talent, but also in retaining them by fulfilling their desire for meaningful and responsible work.

Several studies have investigated the influence of GHRM practices on employee retention, particularly among the millennial generations. According to Islam et al. (Citation2021), green rewards and training significantly impact millennial retention in the hotel industry. Similarly, Al-Hajri (Citation2020) reports a positive association between GHRM practices and employee retention in the pharmaceutical industry. However, Islam et al. (Citation2023) discovered that the impact of GHRM practices on millennial turnover intention in the tourism industry is moderated by the work environment. These studies indicate that GHRM practices can significantly enhance employee retention, particularly among millennial employees. However, the specific mechanisms and contextual factors influencing this relationship warrant further investigation. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H1: GHRM positively influences employee retention.

2.2.2. The effect of GHRM on job expectations

The integration of green practices within an organization’s management system is seen not just as a commitment to environmental stewardship, but also as a strategic approach to enhancing employee engagement and satisfaction. Kuria and Mose (Citation2019), along with Brefo-Manuh et al. (Citation2017), highlight that when organizations adopt green practices, they signal a commitment to broader societal and environmental goals. Commitments are believed to significantly impact employees’ attitudes and beliefs regarding their work environments. Workers are increasingly looking for employers who demonstrate not only financial and operational success but also social and environmental responsibility. According to Harter (Citation2022), implementing GHRM practices can increase employee motivation and job satisfaction. Green practices often involve initiatives that create a more engaging and fulfilling work environment. Employees who observe tangible efforts made by their organization to positively impact the environment are often more motivated and prouder to participate in such an organization.

Research on GHRM and its impact on job expectations have yielded several significant findings. According to Chaudhary (Citation2018), GHRM has a significant influence on job pursuit intention, with organizational prestige mediating this relationship. This indicates that GHRM can attract young talent, especially those with strong environmental orientation. Beri et al. (Citation2020) further expansion on this by identifying a range of GHRM activities within HRM's functions, highlighting the potential for GHRM to enhance environmental efficiency. Aboramadan et al. (Citation2021) also found that GHRM boosts employees’ perceptions of green organizational support, which in turn enhances job performance and organizational citizenship behavior. Ahuja (Citation2015) also emphasized the need for a comprehensive framework for GHRM, which can lead to decreased costs, higher efficiency, and better management of employees. Collectively, these studies suggest that GHRM can positively influence job expectations by attracting talent, enhancing environmental efficiency, and improving job performance. Based on these findings, the second hypothesis was as follows:

H2: GHRM positively influences job expectations.

2.2.3. The effect of job expectations and employee retention

Millennials, known for their unique values and workplace preferences, place high value on factors such as work/life balance, flexibility, and opportunities for professional development. These preferences significantly impact job satisfaction and, consequently, loyalty and retention in an organization. Studies have shown that millennials approach job satisfaction differently than do previous generations. Linden (Citation2015) indicated that millennials seek more than just a paycheck from their jobs; they look for roles that provide them with a sense of purpose and opportunities for personal and professional growth. Kuron et al. (Citation2015) further elaborate that millennials value employers who offer flexibility in work arrangements, support for personal development, and a workplace culture that aligns with their own values. These expectations are not just ancillary benefits for millennials, but are central to their decision to remain with an employer. Understanding and meeting these job expectations is, therefore, key to retaining millennial talent. When organizations align their policies and practices with the aspirations of the millennial workforce, they create a more engaging and satisfying work environment. This alignment leads to increased job satisfaction among millennials, making them more likely to stay with the organization in the long term.

Factors such as job satisfaction (Sabbagha et al., Citation2018), organizational culture (Wright, Citation2021), benefits, and salary (Kryscynski, Citation2021) have been shown to influence employee retention. Bashir and Gani (Citation2020) emphasized the positive impact of compensation and organizational commitment on job satisfaction and retention. Employer branding can also influence staff retention and compensation expectations, as suggested by Bussin and Mouton (Citation2019). Together, these findings indicate that a combination of job satisfaction, organizational culture, compensation, and the workplace environment can significantly impact employee retention. Based on these findings, our third hypothesis is as follows:

H3: Job expectation positively influences employee retention.

2.2.4. The effect of GHRM on self-efficacy

GHRM practices serve the dual purpose of implementing environmentally friendly policies and empowering employees by boosting their confidence and ability to effectively contribute to environmental sustainability. Research indicates that when organizations engage in GHRM practices, they foster a work environment in which employees feel capable and equipped to undertake green initiatives. Studies by Kuria and Mose (Citation2019) and Farooq et al. (Citation2022) all highlight the positive impact of GHRM on employees’ self-efficacy. This is particularly crucial in environmental matters, where employees often face challenges that require not only technical skills, but also a belief in their ability to make a difference. GHRM practices, such as green training, environmental awareness programs, and the incorporation of sustainability goals into employee performance metrics contribute to developing a sense of efficacy among employees. When employees receive the necessary training and resources to implement green practices, they develop stronger beliefs in their capabilities. This enhanced self-efficacy motivates them to take initiative and engage more proactively in environmental activities within the organization.

Research shows a positive association between GHRM and self-efficacy. Farooq et al. (Citation2022) found that GHRM is positively associated with green creativity, and green self-efficacy mediates this relationship. This suggests that GHRM can enhance employees’ beliefs in their ability to contribute to environmental sustainability. Additionally, Ahuja (Citation2015) and Sathyapriya et al. (Citation2013) highlighted the role of GHRM in promoting sustainable practices and increasing employee awareness and commitment to sustainability, which can contribute to the development of self-efficacy. Similarly, Alreahi et al. (Citation2023) emphasized the importance of GHRM in the hotel industry, where it can enhance employees’ environmental awareness and responsibility, potentially leading to increased self-efficacy in this area. Based on these findings, our fourth hypothesis was as follows:

H4: GHRM positively influences self-efficacy.

2.2.5. The effect of self-efficacy on employee retention

Self-efficacy, which refers to an individual’s confidence in their ability to accomplish tasks and overcome obstacles, is a crucial factor in determining an employee’s engagement (Luthans & Peterson, Citation2002), satisfaction (Canrinus et al., Citation2012), and the ultimate decision to remain with an organization (Chami-Malaeb, Citation2021). This is particularly true for the millennial generation, who often prioritize environments that allow them to effectively utilize and develop their skills. Studies have shown that individuals with high self-efficacy are more likely to embrace challenges, view demanding tasks as opportunities for learning and growth, and experience a sense of accomplishment at work. Chami-Malaeb (Citation2021) and Fallatah et al. (Citation2017) demonstrated the positive impact of self-efficacy on employees’ attitudes towards their jobs and their likelihood of remaining with their employer. This is particularly relevant for millennials, who tend to prioritize personal and professional development in their career choices. Millennials with high self-efficacy are more likely to feel competent and effective in their roles, leading to higher job satisfaction and reduced likelihood of seeking employment elsewhere. They are also better equipped to handle the complexity and rapid changes in today’s work environment, making them valuable assets for any organization.

Research has also demonstrated a strong association between self-efficacy and employee retention. According to Potgieter and Mawande (Citation2017), self-efficacy and other employability attributes such as self-esteem significantly predict job retention in the financial sector. McNatt and Judge (Citation2008) also revealed that self-efficacy intervention can enhance job attitudes and decrease turnover, particularly among recent employees. Peterson (Citation2009) emphasized the role of career decision-making self-efficacy in managerial retention, suggesting that it can be improved through career development programs. Yurchisin and Park (Citation2010) further highlighted the importance of self-evaluated job performance, likely influenced by self-efficacy, in increasing employee retention in retail settings. Collectively, these studies emphasize the significance of self-efficacy in promoting employee retention across various industries, leading to our fifth hypothesis:

H5: Self-efficacy positively influences employee retention.

2.2.6. The mediating role of job expectations in GHRM on employee retention

GHRM plays a crucial role in fostering eco-friendly behaviors and attitudes in the workplace. The efficacy of GHRM in retaining employees is largely contingent on how these practices align with their job expectations. Research has demonstrated that implementing GHRM practices can lead to changes in the work environment, which in turn impacts employees’ perceptions and expectations about their jobs. Studies by Islam et al. (Citation2021), Qadri et al. (Citation2022), Leidner et al. (Citation2019), and Hameed et al. (Citation2020) suggest that when employees perceive their organization’s GHRM efforts as aligning with their own values and career aspirations, their satisfaction and commitment to the organization increase. This alignment is particularly significant in the context of job expectations, which encompasses not only the nature of the work and compensation, but also the work environment and the organization’s values. Job expectations act as a mediating factor in this context. These factors influence how employees interpret and respond to GHRM practices. If these practices meet or exceed employees’ expectations regarding environmental stewardship and corporate social responsibility, they enhance their job satisfaction and commitment, thereby increasing their likelihood of staying with the organization. Conversely, if GHRM practices fall short of employee expectations, the potential benefits of retention cannot be fully realized.

Exploring the complexities of millennial work-related expectations and objectives, this study provides a comprehensive understanding of the unique characteristics of career goals and daily work expectations within this demographic (Luscombe et al., Citation2013; Vui-Yee & Paggy, Citation2020). This distinction is essential because it emphasizes the importance of aligning organizational practices, including GHRM, with the intrinsic and extrinsic motivations of millennial employees (Broadbridge et al., Citation2007; Luscombe et al., Citation2013). According to Luscombe et al. (Citation2013), while millennials’ career goals could encompass broader ambitions and a "wish list" for their professional lives, their daily career expectations are more closely tied to the practicalities of their work environments and the nature of their job roles (Lindquist, Citation2008). This distinction between goals and expectations among millennial workers provides a fundamental perspective for comprehending how job expectations mediate the relationship between GHRM practices and employee retention. Considering that GHRM practices aim to align organizational objectives with environmental sustainability and employee well-being, the integration of these practices must resonate with millennial employees’ daily career expectations to effectively impact their retention. For example, the emphasis that millennials place on collaborative work environments, organizational fairness, and opportunities for training and development are aspects of daily work expectations that GHRM practices can directly influence (Jain & Lima, Citation2018). Based on these observations, we propose the following hypotheses:

H6: Job expectation mediates the effect of GHRM on employee retention.

2.2.7. The mediating role of self-efficacy in GHRM on employee retention

Self-efficacy, which refers to an individual’s belief in their ability to execute behaviors necessary for achieving specific performance outcomes, plays a crucial role in how employees perceive and engage in GHRM initiatives. The idea is that GHRM practices enhance self-efficacy, which, in turn, positively affects employee retention. Research by Carter et al. (Citation2018) and Judeh and Abou-Moghli (Citation2019) provides insights into this relationship. These studies indicate that when employees feel capable and empowered through GHRM practices such as training in sustainability and involvement in green initiatives, they boost their self-efficacy. This heightened sense of self-efficacy can lead to a greater sense of ownership and commitment towards the organization, influencing their decision to remain with the company. In this context, self-efficacy acts as a mediating factor between the implementation of GHRM practices and employee retention. This suggests that the direct impact of GHRM on retention is significantly enhanced when employees feel that they effectively contribute to the organization’s environmental goals. This sense of efficacy and accomplishment in green initiatives can be particularly motivating, leading to increased job satisfaction and lower likelihood of seeking employment elsewhere.

According to Judeh and Abou-Moghli (Citation2019), self-efficacy mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and intent to stay. The research demonstrates that self-efficacy does not merely correlate with transformational leadership but also serves as a partial mediator, indicating that the effect of transformational leadership on retention is both direct and indirect via self-efficacy. In the context of GHRM and employee retention, Judeh and Abou-Moghli (Citation2019) research can be argued to provide a compelling argument for considering self-efficacy as a mediating factor. GHRM practices that focus on incorporating environmental sustainability into HR functions can be more effective when they also aim to enhance employees’ self-efficacy. Farooq et al. (Citation2022) further expanded this discussion by examining the role of self-efficacy in mediating the relationship between GHRM and green creativity in luxury hotels and resorts. Based on these observations, we propose the following hypotheses:

H7: Self-efficacy mediates the effect of GHRM on employee retention.

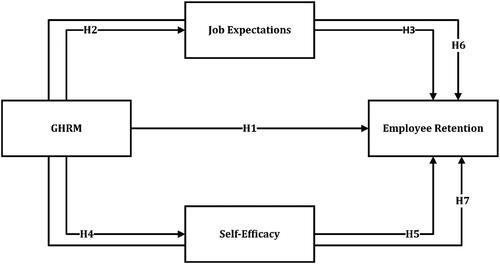

Following the development of our hypotheses, it is essential to outline a research framework that guides the empirical investigation of these hypotheses. This framework serves as a roadmap for examining the interrelationships among GHRM, job expectations, self-efficacy, and employee retention, particularly within the context of the millennial workforce. It aims to provide a structured approach to understanding how these elements interact and influence one another. The research model is illustrated in .

The proposed research framework is structured around the central theme of GHRM and its impact on millennial employee retention mediated through job expectations and self-efficacy. The framework begins with GHRM practices, which are posited to directly influence both job expectations and employee self-efficacy. These two factors Job expectations and self-efficacy are hypothesized to mediate the relationship between GHRM practices and employee retention.

3. Methodology

The methodology section of this paper outlines the approach used to investigate the relationship between GHRM, job expectations, self-efficacy, and employee retention among millennial employees in Indonesian technology startups.

3.1. Sample and sampling procedure

The sample frame and procedure for this study were meticulously designed to ensure the accuracy and representativeness of the results (Saunders et al., Citation2009; Sekaran & Bougie, Citation2016). Initially, the sample size was determined using the G*Power software, a tool widely recognized for its efficacy in statistical power analysis. This process ensured that the chosen sample size was sufficient to detect the effects studied, thereby enhancing the reliability of the research findings. A total of 457 millennial employees from 36 start-up technology companies across Indonesia were initially approached. These individuals were selected using a random sampling method, which supports the creation of a diverse and representative sample (Lind et al., Citation2018; Sekaran & Bougie, Citation2016). This method is particularly effective in minimizing selection bias and ensuring that the sample accurately reflects the broader population of millennial employees in the Indonesian technology sector (Suwarni et al., 2020).

However, to ensure the quality and integrity of the data, certain criteria were set for the inclusion of responses in the final analysis (Fahlevi et al., Citation2022). Respondents who completed the questionnaire in less than two minutes were excluded from the study. This criterion was established based on the rationale that such a short response time might indicate a lack of thoughtful engagement with questions, potentially leading to unreliable data. Additionally, responses in which participants selected the same option throughout the questionnaire were excluded. This measure was intended to identify and remove potential cases of response bias or disengagement, where respondents might not genuinely reflect on and respond to each question (Gotz et al., Citation2010).

After these criteria were applied, the total number of valid responses was reduced to 436. This represents a participation rate of over 93%, indicating a robust response rate that adds to the credibility and reliability of the research findings. The high participation rate, coupled with rigorous data filtering criteria, ensures that the study’s results are based on thoughtful, engaged responses, and accurately reflect the perceptions and experiences of millennial employees in Indonesian technology startups.

3.2. Respondent demographics

This study focuses on millennial employees as a strategic choice, reflecting the unique characteristics and workplace dynamics of this demographic (Afridi et al., Citation2023; Winter & Jackson, Citation2016), particularly within the context of Indonesia’s rapidly evolving technology sector. Millennials, typically identified as individuals born between 1981 and 1996, constitute a significant and influential segment of the workforce. Their distinct values, attitudes, and expectations towards work make them particularly relevant for studies examining GHRM, job expectations, self-efficacy, and employee retention.

Millennials are characterized by their digital proficiency, which has grown during the rise of the digital age (Dries et al., Citation2008; Purnama et al., Citation2021). This aspect is critical in the context of technology start-ups, where adaptability and familiarity with digital technologies are paramount. Millennials are known for their value-driven work ethics. They often seek employment that is not only financially rewarding, but also aligns with their personal values, particularly concerning social and environmental responsibility. This trait is essential for understanding the impact of GHRM practices, as millennials are likely to respond positively to sustainable and ethical workplace initiatives (Abbas et al., Citation2022a, Citation2022b). Millennials are recognized for their desire for work-life balance and opportunities for professional growth and development. These expectations significantly influenced job satisfaction and retention decisions. By focusing on millennial employees in Indonesian technology startups, this study aims to gain insights into how this generation’s unique workplace preferences and expectations are influenced by GHRM practices and how these, in turn, affect their self-efficacy and retention within their organizations (Mushtaq et al., Citation2022). This demographic focus ensures that the findings of the study are relevant and applicable to the current and future landscapes of human resource management in the technology sector.

3.3. Data collection

Data were collected through structured questionnaires distributed to selected employees of 36 startup technology companies. These questionnaires were designed to gather comprehensive information on employees’ perceptions and experiences with GHRM practices in their organizations, job expectations, self-efficacy levels, and intentions or decisions regarding job retention.

3.4. Measurements

We carefully selected the established scales from previous studies to accurately assess each key variable. These scales were chosen based on their relevance and reliability in previous research. The measurement of GHRM practices was based on a scale developed by Tang et al. (Citation2018). This scale effectively captures the extent to which organizations implement environmentally friendly HR practices including green training, development, performance appraisal, and rewards. It is designed to assess how these practices are perceived by employees and their impact on their attitudes and behaviors towards environmental sustainability in the workplace. The measurement of job expectations aligned with the scale proposed by Maden et al. (Citation2016). This scale evaluates various aspects of job expectations that millennials consider important, such as career advancement opportunities, work-life balance, organizational values, and the degree of autonomy in the workplace. This helps us understand how these expectations influence job satisfaction and commitment.

For assessing self-efficacy, the study utilized the scale developed by Schyns and Von Collani, (Citation2002). This scale measures employees’ beliefs about their capability to exercise control over their own functioning and environmental events. This scale is particularly relevant for understanding how self-efficacy in environmental initiatives and general workplace tasks impacts employees’ engagement and retention. Employee retention was measured using Yamamoto’s (Citation2011) scale. This scale provides insight into the factors that influence an employee’s intention to stay with an organization, including job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and perceived alternatives to their current job. It is instrumental in determining how GHRM, job expectations, and self-efficacy contribute to retaining employees, especially within the millennial demographic context.

3.5. Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using SmartPLS 4, a statistical software tool widely used for partial least squares structural equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) (Ringle et al., Citation2020; Sarstedt et al., Citation2017). PLS-SEM is particularly suited for exploratory research where the goal is theory building, making it an appropriate choice for this study. SmartPLS 4 allows for the effective handling of complex models and multiple variables, facilitating the analysis of the relationships and interactions among GHRM, job expectations, self-efficacy, and employee retention.

3.6. Ethical considerations

The research protocol for this study was duly approved by the Ethics Committee of Pelita Bangsa University, as evidenced by the approval number PBUEC/2024-03/02. This section outlines the ethical principles that were upheld during the course of the research, highlighting the commitment to adhering to both the university’s guidelines and the broader ethical standards established in the field.

3.7. Informed consent process

This section clarifies the process of obtaining informed consent from participants. It emphasizes the thorough disclosure made to the participants about the study’s goals, procedures, potential hazards, and advantages, thereby ensuring their comprehension and voluntary involvement. The procedure for obtaining consent, whether in written or verbal form, is detailed, with particular attention given to the assurances provided to participants regarding their right to withdraw and the measures taken to safeguard their privacy and confidentiality.

4. Results

4.1. Profile respondents

A detailed profile of the respondents is compiled (). This profile provides crucial insights into the demographic composition of the participants and offers a comprehensive overview of the individuals who contributed their perspectives to the study. The data encapsulates various demographic attributes, such as age range, gender distribution, education level, job position, company size, tenure at the current company, industry type, and geographical location. Understanding these demographics is essential for interpreting the findings of this study within the appropriate context.

Table 1. Profile respondents.

The respondent profile for this research provides a detailed demographic breakdown of the 436 participants, all of whom are millennial employees born between 1981 and 1996, thus falling within the age range of 24–39 years. This age group is particularly significant, as it captures the essence of the millennial generation, offering insights specific to this cohort’s workplace preferences and behaviors. The gender distribution among the respondents showed a slight male predominance, with 55% male and 45% female participants. This balance offers a diverse perspective on the workplace dynamics and perceptions of GHRM practices. In terms of educational background, the majority of the respondents (71%) held a bachelor’s degree, 24% had a master’s degree, and 5% had other educational qualifications. This high level of education indicates a well-informed and skilled workforce, which is typical in the technology sector.

The job positions of the respondents varied, with 63% occupying mid-level positions, 31% occupying entry-level roles, and a smaller segment (6%) holding senior or management roles. This distribution suggests that the findings of this study predominantly reflect the perspectives of mid-career professionals. The companies represented in this study are of moderate size, with an average of 50 to 200 employees. This size range is typical of startups and medium-sized enterprises in the tech industry, which are often characterized by dynamic and innovative work environments. Regarding tenure at their current company, 40% of the respondents had been employed for less than two years, 35% for 2–5 to years, and 25% for more than five years. This variation in tenure length provides a broad perspective on employee retention factors across different stages of employment. This study focuses on technology startups, which are a rapidly growing and evolving sector in Indonesia. The respondents are spread across major cities in Indonesia, ensuring geographical diversity that reflects the widespread nature of the technology industry in the country.

4.2. Common method bias

In empirical research, particularly when using survey data, it is crucial to assess the extent of common method bias, a form of measurement error that can occur if the data for the predictors and outcomes are derived from the same source. To address this, we conducted a Common Method Bias Test using Harman’s Single-Factor Test (Kock, Citation2015), a widely recognized technique for detecting the presence of such a bias in research data. The following table presents the results of this test, conducted using Principal Component Analysis (PCA).

The results of Harman’s Single-Factor Test, presented in , indicate that the variance explained by a single factor was only 22.7%. This is significantly below the 50% threshold that is commonly used to indicate a serious level of common method bias. This low percentage is indicative of minimal common method bias in our study, suggesting that the data and resultant findings are not overly influenced by this type of bias. The use of PCA in this test allowed for a nuanced analysis of the data structure, further reinforcing the reliability of these findings. This outcome provides confidence in the validity of the research methodology and integrity of the data collected, ensuring that the conclusions drawn from the study are based on sound empirical evidence.

Table 2. Common method bias test.

4.3. Measurement model

This study employed a comprehensive measurement approach to ensure the validity and reliability of the constructs. Each construct is measured using a set of indicators. The following table presents the key statistical measures for these constructs. The table includes Outer Loading (Convergent Validity), Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Composite Reliability, and Cronbach’s Alpha for each construct (Hair et al., Citation2017), providing a detailed overview of the measurement model’s robustness

demonstrates the strength and reliability of the measurement scales used in this study. The Outer Loading values, which reflect convergent validity, are well above the acceptable threshold of 0.50 for all indicators, indicating that each item strongly relates to its respective construct. This confirmed the appropriateness of the selected items for measuring each construct. The AVE for each construct exceeded the recommended benchmark of 0.50, suggesting that a significant portion of the variance in the indicators was accounted for by their respective constructs. This finding affirms the construct validity of the measures used in this study. The Composite Reliability and Cronbach’s alpha values for all constructs were above the generally accepted thresholds of 0.70 and 0.60, respectively, indicating high internal consistency. This suggests that the items within each construct reliably and consistently measured the underlying concept.

Table 3. Measurement model.

4.4. Discriminant validity

A crucial step in the analysis process is to assess discriminant validity to ensure the distinctiveness of the constructs used in our study. This aspect of validity determines whether the constructs in the model are truly unique, and not merely reflections of other variables. The Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio is a widely used method for evaluating discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modelling (Hair et al., Citation2017; Ringle et al., Citation2020) such as PLS-SEM. The following table presents the HTMT ratios of the constructs.

The results in show the HTMT ratios for each pair of constructs. An HTMT value below 0.90, or more conservatively to 0.85, is generally considered to indicate good discriminant validity. In our study, the HTMT values between all pairs of constructs were well below the thresholds. For instance, the HTMT ratio between GHRM and Job Expectations was 0.82, suggesting that while these constructs are related; they are distinct from each other. Similarly, the ratios between GHRM and Employee Retention (0.78) and Job Expectations and Employee Retention (0.75) reinforce the notion that these constructs are unique and do not overlap significantly. The HTMT ratios for self-efficacy with other constructs, such as 0.70 with GHRM, 0.68 with Job Expectations, and 0.65 with Employee Retention, further confirm that self-efficacy is a distinct construct within the model. The clear distinction between each pair of constructs ensures that the model measures different concepts, and that the relationships observed are not due to overlapping construct definitions. This strengthens the reliability of the research model and validity of the conclusions drawn from the analysis (Lind et al., Citation2018).

Table 4. HTMT ratio for discriminant validity.

4.5. PLS Predict

To assess the predictive capabilities of our model, we used the Partial Least Squares (PLS) prediction method, which is crucial for evaluating how well our model can predict unseen data. This analysis is particularly important in structural equation modeling as it provides evidence of the model’s practical applicability. The PLS Predict method yields several key metrics: Q2 for predictive relevance, Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) (Ringle et al., Citation2020). The following table presents the results of the PLS prediction analysis for each construct.

The results presented in indicate the model’s strong predictive capability. For each construct, the Q2 value was greater than zero, indicating good predictive relevance. Specifically, Job Expectations showed the highest predictive relevance, with a Q2 of 0.62, suggesting that the model is particularly effective in predicting this construct. The RMSE and MAE values complement the Q2 results by providing insight into the accuracy of the model. Lower RMSE and MAE values are desirable because they indicate smaller prediction errors. For instance, GHRM has an RMSE of 0.12 and an MAE of 0.09, reflecting good accuracy in predictions. Similarly, Job Expectations, with an RMSE of 0.10 and an MAE of 0.08, demonstrate even stronger predictive accuracy. Employee Retention, while having a slightly lower Q2 of 0.48, still showed satisfactory predictive relevance and accuracy. Self-efficacy also exhibits good predictive relevance and accuracy, aligned with other constructs in the model.

Table 5. PLS predict.

4.6. Structural model

To comprehensively evaluate the relationships and influences among the constructs in our study, we conducted a series of statistical tests, the results of which are presented in . This table merges the findings from the path coefficient test, R-squared value analysis, Direct Effect Test, and Indirect Effect Test. These analyses collectively offer insights into the strength and significance of the relationships between GHRM, Job Expectations, Self-Efficacy, and Employee Retention as well as the predictive power of the model (Sarstedt et al., Citation2017).

Table 6. Path coefficient, R-square, direct, and indirect effects.

The results in provide a detailed overview of the relationships between the key constructs. The Path Coefficient Test revealed a strong relationship between GHRM and Self-Efficacy and medium relationships with job expectations and employee retention. This indicates that GHRM practices have a considerable impact on self-efficacy and moderately influence job expectations and retention. The R-Square values show that a significant proportion of the variance in Job Expectations, Employee Retention, and Self-Efficacy is explained by the model, with Employee Retention having the highest variance at 67.6%. This suggests that the model effectively captured the factors influencing these constructs. The direct effects test aligns with the Path Coefficient Test results, confirming the strength and direction of these relationships. However, the Indirect Effect Test indicates that the mediating effects of job expectations and self-efficacy on the relationship between GHRM and Employee Retention are not statistically significant. This suggests that, while GHRM directly influences these constructs, its impact on employee retention is not significantly mediated through job expectations or self-efficacy.

5. Discussion

Millennials are the most occupied employees in several industrial companies in Indonesia; therefore, it is interesting to keep millennial employees staying in their jobs, considering that this millennial generation finds it difficult to survive in a company. The significant relationship between GHRM practices and self-efficacy emphasizes the critical role that environmental sustainability plays in empowering employees. This finding is consistent with Farooq et al. (Citation2022), who demonstrated that GHRM practices enhance employees’ green creativity by increasing their green self-efficacy. This suggests that when organizations implement GHRM initiatives, they not only promote environmental sustainability but also significantly boost employees’ confidence in their ability to contribute to these green goals. This empowerment is particularly important for millennials, who value meaningful work and the opportunity to make a positive impact (Hershatter & Epstein, Citation2010). In the context of Indonesian technology startups, where agility and innovation are essential, enhancing self-efficacy through GHRM could be a strategic move to attract and retain millennial talent by aligning with aspirations for impactful work (H1 is accepted), in this case GHRM is in a leading position, employees crave to be appreciated and effective in their duties (J. Purcell & Hutchinson, Citation2007), (Kowalski & Loretto, Citation2017). GHRM stimulates the need for green employee behavior and commitment (Rubel et al., Citation2020). Employee green work engagement affects employee behavior (Pham et al., Citation2020); (Shahzad, Citation2020), in which employees have job expectations that they can survive in a company if they feel self-efficacy (Abun et al., Citation2021); (Consiglio et al., Citation2016). This study states that GHRM has a positive and significant effect on job expectations (Yoon et al., Citation2012); (Ryan & Wessel, Citation2015) (H2 is accepted).

The GHRM diversity policy focuses on eligibility to support equal opportunities for all employees, and employees highly expect job expectations (Jordan et al., Citation2019). Green HRM is a tool to develop green skills among employees, such as awareness and motivation, in order to encourage them to participate in important initiatives (Shen et al., Citation2018), which is very interesting for millennial generations who are very prone to retention to stay. Millennials do not like working in one place for a long time (Santos, Citation2018). On the other hand, when the turnover rate is reduced by any activity, it will increase the retention rate, which means HRM practices help increase employee retention (Deshwal, Citation2015); (Yadav, Citation2017). This study states that GRHM has a positive and significant effect on employee retention (H3 is accepted). GHRM practices such as compensation are very supportive in employee retention reviews, showing that GHRM practices help increase employee retention.

Employee retention is beneficial for both the company and employees, and the leader is the most responsible for employee retention. A superior leader must be able to attract and retain the best talent from his employees; however, employees will survive in the company with some expectations that employees want (Mule, Citation2022). Companies find it difficult to find and retain employees with extraordinary talent because of the competition and scarcity of skilled employees (Kuldeep et al., Citation2021). Companies whose employees stay with them in the long term can save both time and money. Retaining the best talent is key to driving organizational growth. Millennials are career-oriented and ready to change jobs if there is a mismatch in skills and job requirements; therefore, it is very important to retain employees by providing expectations in their work according to their talent (Chavadi et al., Citation2022; Mule, Citation2022). This study found that employee retention has a positive and significant effect on job expectations (H4 is accepted). Employee retention plays an important role in bridging the gap between macro-strategy and micro-behavior in organizations. Organizations that are unable to retain talented employees are considered to have retention problems (Heery & Noon, Citation2008). In fact, many leaders feel insecure if they are unable to maintain valuable staff. Self-efficacy determines behavior and changes in employee behavior. Muhangi (Citation2017) states that teachers are required to be successful and able to handle several things, not even because they are less skilled or lack knowledge, but because they lack self-confidence, which shows that self-efficacy is very important, but not directly related to employee retention. This study found no direct relationship between self-efficacy and employee retention (H5 is accepted).

The study’s results contradict conventional knowledge by revealing that job expectations and self-efficacy fail to significantly mediate the relationship between GHRM and employee retention. This outcome runs counter to theoretical frameworks based on SET and previous empirical evidence, leading to a more nuanced understanding of the factors that contribute to employee retention in the startup context (H6 is rejected) and (H7 is rejected) to mediate the impact of GHRM on employee retention can be attributed to several factors. First, considering the respondent profile, which predominantly includes millennial employees in technology startups, it is possible that these demographic values direct and tangible aspects of employment (such as workplace culture, immediate job benefits, and career growth opportunities) over abstract constructs, such as job expectations or self-efficacy. Millennials, known for their desire for immediate gratification and quick career progression, might respond more significantly to direct GHRM initiatives impacting their day-to-day work life rather than the broader, long-term constructs of job expectations or self-efficacy. Moreover, in the fast-paced and innovation-driven environment of technology startups, millennial employees may prioritize direct engagement and recognition of the indirect benefits of self-efficacy or job expectations. The implication is that while GHRM practices enhance job expectations and self-efficacy, they may not directly lead to greater retention among millennial employees. This finding could be indicative of the broader landscape in which Indonesian startups function, where rapid change and the appeal of entrepreneurial opportunities could overshadow the impact of job expectations and self-efficacy on retention decisions.

6. Conclusion, implication, and limitation

This study found that GHRM significantly affects self-efficacy and job expectations; however, contrary to the initial hypotheses, these factors do not mediate the relationship between GHRM and employee retention. Instead, the impact of GHRM on retention was more direct. These findings have practical implications for HR practitioners and organizational leaders in technology startups, suggesting that while fostering self-efficacy and aligning job expectations with organizational goals are important, these factors alone may not be sufficient to retain millennial talent. Instead, focusing on direct GHRM practices that enhance the work environment and provide immediate benefits could be more effective in retaining the staff. This study recommends a nuanced strategy for Indonesian technology startups to retain millennial talent through the implementation of GHRM practices. Although such initiatives have a positive impact on self-efficacy and are generally well received with respect to job expectations, startups may need to incorporate these practices within a broader strategic framework that takes into account the diverse motivations of millennial employees. By integrating environmental sustainability into the core business model and innovation strategies, startups can make green practices a natural and intrinsic aspect of their organizational culture.

Our research expands the applicability of SET to the domain of GHRM and millennial employee retention, offering valuable theoretical and practical perspectives. By comprehending and applying these perspectives, technology startups in Indonesia and other countries can implement more effective HR strategies that not only support environmental sustainability but also cultivate a dedicated, involved, and productive workforce. A limitation of this study is its specific focus on the millennial cohort of Indonesian technology startups, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other industries or generational groups. Additionally, reliance on self-reported measures may introduce response bias. Future research could explore the impact of GHRM in different organizational contexts and examine other potential mediating variables that may influence the relationship between GHRM and employee retention.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Setyaningrum and Soelistya; methodology, Fahlevi.; software, Purwati.; validation, Desembrianita; formal analysis, Ratnasari; investigation, Fahlevi.; resources, Setyaningrum and Soelistya; data curation, Ratnasari; writing—original draft preparation, Setyaningrum and Soelistya; writing—review and editing, Fahlevi, Purwati, Ratnasari, & Desembrianita.; visualization, Purwati; supervision, Ratnasari & Desembrianita; project administration, Fahlevi; funding acquisition, Setyaningrum, Soelistya, Ratnasari, Purwati, Desembrianita. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made by request to the corresponding authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Retno Purwani Setyaningrum

Retno Purwani Setyaningrum, Professor in Management at the Magister Management Program at the Universitas Pelita Bangsa, Indonesia with additional duties as Senate of the Universitas Pelita Bangsa. Research focus in the fields of Human Resource Management, Leadership, Organizational Behavior, Strategic Management, and Entrepreneurship.

Sri Langgeng Ratnasari

Sri Langgeng Ratnasari, Professor in Management at the Postgraduate Program at the Universitas Riau Kepulauan, Batam, Indonesia with additional duties as Chancellor of the Universitas Riau Kepulauan. Research focus in the fields of Human Resource Management, Organizational Behavior, Strategic Management, and Educational Management.

Djoko Soelistya

Djoko Soelistya is a practitioner born in Surabaya on September 8, 1967. He began his career in the business world in 1989. Upon obtaining a Master’s degree in Management, he embarked on another service path by starting to teach in the field of education as a lecturer in the Master of Management Program at the Graduate School of Muhammadiyah University of Gresik. He is actively engaged in scholarly work, having authored several textbooks, reference books, monographs, and published reputable articles in national and international journals.

Titik Purwati

Titik Purwati is a lecturer at Programme of Economic Education, of Universitas Insan Budi Utomo, Malang. She obtained her Bachelor’s degrees in Economic Education in Universitas Negeri Malang, Indonesia. Then her Master’s degree in Management, of Universitas Brawijaya and Doctoral Programme in Economic Science, Merdeka University, Malang. Additional duties as Chief of LP P M in Universitas Insan Budi Utomo. Research focus in the field of Human Resource Management, Medium, Small and Micro Business, and Entrepreneurship.

Eva Desembrianita

Eva Desembrianita is an lecturer at Universitas Muhammadiyah Gresik, she specializes in management studies. Eva serves as a permanent faculty member, actively contributing to the academic community at Universitas Muhammadiyah Gresik. Her commitment to education and her academic role are evident in her dedication to her students and her scholarly pursuits. Eva is highly respected both as a scholar and an educator in her field.

Mochammad Fahlevi

Mochammad Fahlevi, the Founder of Privietlab Research Center, is a distinguished academic and researcher renowned for his expertise in management, business economics, corporate governance, and health management. currently working as a faculty member at Bina Nusantara University, one of the leading universities in Indonesia.

References

- Abbas, A., Ekowati, D., Suhariadi, F., Fenitra, R. M., & Fahlevi, M. (2022a). Human capital development in youth inspires us with a valuable lesson: Self-care and wellbeing. In Self-Care and Stress manage for academic well-being (pp. 80–101). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-6684-2334-9.ch006

- Abbas, A., Ekowati, D., Suhariadi, F., Fenitra, R. M., & Fahlevi, M. (2022b). Integrating cycle of prochaska and diclemente with ethically responsible behavior theory for social change management: Post-covid-19 social cognitive perspective for change. In Handb. Of Res. On Global Networking Post COVID-19 (pp. 130–155). IGI Global; Scopus. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-8856-7.ch007

- Aboobaker, N., Edward, M., & K.a, Z. (2020). Workplace spirituality and employee loyalty: An empirical investigation among millennials in India. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 14(2), 211–225. https://doi.org/10.1108/JABS-03-2018-0089

- Aboramadan, M., Kundi, Y. M., & Becker, A. (2021). Green human resource management in nonprofit organizations: Effects on employee green behavior and the role of perceived green organizational support. Personnel Review, 51(7), 1788–1806. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-02-2021-0078

- Abun, D., Nicolas, M. T., Apollo, E. P., Magallanes, T., & Encarnacion, M. J. (2021). Research in business & social science employees ‘ self -efficacy and work performance of employees as mediated by work environment. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science, 10(7), 1–15.

- Adkins, A. (2016). Millennials: The Job-Hopping Generation. Gallup.Com. https://www.gallup.com/workplace/231587/millennials-job-hopping-generation.aspx

- Afridi, S. A., Shahjehan, A., Zaheer, S., Khan, W., & Gohar, A. (2023). Bridging generative leadership and green creativity: Unpacking the role of psychological green climate and green commitment in the hospitality industry. SAGE Open, 13(3), 21582440231185759. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231185759

- Afsar, B., Bibi, A., & Umrani, W. A. (2020). Ethical leadership and service innovative behaviour of hotel employees: The role of organisational identification and proactive personality. International Journal of Management Practice, 13(5), 503–520. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMP.2020.110003

- Ahuja, D. (2015). Green HRM: Management of people through commitment towards environmental sustainability. International Journal of Research in Finance and Marketing, 5(7), 50–54.

- Al-Hajri, S. A. (2020). Employee retention in light of green HRM practices through the intervening role of work engagement. Annals of Contemporary Developments in Management & HR,)2(4), 10–19. https://doi.org/10.33166/ACDMHR.2020.04.002

- Alreahi, M., Bujdosó, Z., Kabil, M., Akaak, A., Benkó, K. F., Setioningtyas, W. P., & Dávid, L. D. (2023). Green human resources management in the hotel industry: A systematic review. Sustainability, 15(7), 5622. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010099

- Amrutha, V. N., & Geetha, S. N. (2020). A systematic review on green human resource management: Implications for social sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 247, 119131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119131

- Bahar, A. K. M. M., Islam, M. A., Hamzah, A., Islam, S. N., & Reaz, M. d (2022). The efficacy of work-life balance for young employee retention: A validated retention model for small private industries. International Journal of Process Management and Benchmarking, 12(3), 367–394. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPMB.2022.122202

- Bashir, B., & Gani, A. (2020). Testing the effects of job satisfaction on organizational commitment. Journal of Management Development, 39(4), 525–542. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-07-2018-0210

- Beri, K., Thakur, P., & Gupta, G. (2020). Green human resource management review on methodology. Journal of Critical Reviews, 7(9), 1340–1343.

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Justice in social exchange. Sociological Inquiry, 34(2), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.1964.tb00583.x

- Brefo-Manuh, A. B., Bonsu, C. A., Anlesinya, A., & Odoi, A. A. S. (2017). Evaluating the relationship between performance appraisal and organizational effectiveness in Ghana: A comparative analysis of public and private organizations. International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management, 5(7), 532–552.

- Broadbridge, A. M., Maxwell, G. A., & Ogden, S. M. (2007). Students’ views of retail employment: Key findings from Generation Ys. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 35(12), 982–992. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590550710835210

- Bussin, M., & Mouton, H. (2019). Effectiveness of employer branding on staff retention and compensation expectations. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v22i1.2412

- Canrinus, E. T., Helms-Lorenz, M., Beijaard, D., Buitink, J., & Hofman, A. (2012). Self-efficacy, job satisfaction, motivation and commitment: Exploring the relationships between indicators of teachers’ professional identity. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 27(1), 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-011-0069-2

- Carter, W. R., Nesbit, P. L., Badham, R. J., Parker, S. K., & Sung, L.-K. (2018). The effects of employee engagement and self-efficacy on job performance: A longitudinal field study. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(17), 2483–2502. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1244096

- Catano, V. M., & Hines, H. M. (2016). The influence of corporate social responsibility, psychologically healthy workplaces, and individual values in attracting millennial job applicants. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue Canadienne Des Sciences du Comportement, 48(2), 142–154. https://doi.org/10.1037/cbs0000036

- Chami-Malaeb, R. (2021). Relationship of perceived supervisor support, self-efficacy and turnover intention, the mediating role of burnout. Personnel Review, 51(3), 1003–1019. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-11-2019-0642

- Chaudhary, R. (2018). Can green human resource management attract young talent? An empirical analysis. Evidence-Based HRM: a Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship, 6(3), 305–319. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBHRM-11-2017-0058

- Chavadi, C. A., Sirothiya, M., & M R, V. (2022). Mediating role of job satisfaction on turnover intentions and job mismatch among millennial employees in Bengaluru. Business Perspectives and Research, 10(1), 79–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/2278533721994712

- Chernyak-Hai, L., & Rabenu, E. (2018). The new era workplace relationships: Is social exchange theory still relevant? Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 11(3), 456–481. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2018.5

- Consiglio, C., Borgogni, L., Di Tecco, C., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2016). What makes employees engaged with their work? The role of self-efficacy and employee’s perceptions of social context over time. Career Development International, 21(2), 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-03-2015-0045

- Cook, K. S., Cheshire, C., Rice, E. R., & Nakagawa, S. (2013). Social exchange theory. In Handbook of social psychology (pp. 61–88). Springer.

- Dartanto, T., Moeis, F. R., & Otsubo, S. (2020). Intragenerational economic mobility in Indonesia: A transition from poverty to the middle class in 1993–2014. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 56(2), 193–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2019.1657795

- Deloitte. (2017). The 2017 Deloitte Millennial Survey—Apprehensive Millennials: Seeking stability and opportunities in an uncertain world. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/About-Deloitte/gx-deloitte-millennial-survey-2017-executive-summary.pdf

- Deshwal, S. (2015). Leadership styles and retention of teachers in private primary schools in bushenyi-ishaka municipality, Uganda. International Journal of Applied Research, 1, 344–345.

- Dries, N., Pepermans, R., & De Kerpel, E. (2008). Exploring four generations’ beliefs about career: Is “satisfied” the new “successful? Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23(8), 907–928. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940810904394

- Ekowati, D., Abbas, A., Anwar, A., Suhariadi, F., & Fahlevi, M. (2023). Engagement and flexibility: An empirical discussion about consultative leadership intent for productivity from Pakistan. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2196041

- Fahlevi, M., Aljuaid, M., & Saniuk, S. (2022). Leadership style and hospital performance: Empirical evidence from Indonesia. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(911640), 911640. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.911640

- Fallatah, F., Laschinger, H. K. S., & Read, E. A. (2017). The effects of authentic leadership, organizational identification, and occupational coping self-efficacy on new graduate nurses’ job turnover intentions in Canada. Nursing Outlook, 65(2), 172–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2016.11.020

- Farooq, R., Zhang, Z., Talwar, S., & Dhir, A. (2022). Do green human resource management and self-efficacy facilitate green creativity? A study of luxury hotels and resorts. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(4), 824–845. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1891239

- George, J., & Wallio, S. (2017). Organizational justice and millennial turnover in public accounting. Employee Relations, 39(1), 112–126. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-11-2015-0208

- Gotz, O., Liehr-Gobbers, K., & Krafft, M. (2010). Evaluation of structural equation models using the partial least squares (PLS) approach. Handbook of Partial Least Squares: Concepts, Methods and Applications, 1(3), 691–711.

- Haddock-Millar, J., Sanyal, C., & Müller-Camen, M. (2016). Green human resource management: A comparative qualitative case study of a United States multinational corporation. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(2), 192–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1052087

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.) Sage.

- Hameed, Z., Khan, I. U., Islam, T., Sheikh, Z., & Naeem, R. M. (2020). Do green HRM practices influence employees’ environmental performance? International Journal of Manpower, 41(7), 1061–1079. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-08-2019-0407

- Harter, J. (2022). Is quiet quitting real (p. 22). Gallup. https://www.celynarden.com/uploads/2/0/1/3/2013557/is_quiet_quitting_real_.pdf

- Hassan, M. M., Jambulingam, M., Narayan, E. A., Islam, S. N., & Zaman, A. U. (2021). Retention approaches of millennial at private sector: Mediating role of job embeddedness. Global Business Review, 097215092093228. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150920932288

- Heery, E., & Noon, M. (2008). A dictionary of human resource management. A Dictionary of Human Resource Management, https://doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780199298761.001.0001

- Hershatter, A., & Epstein, M. (2010). Millennials and the world of work: An organization and management perspective. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(2), 211–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9160-y

- Islam, M. A., Hack-Polay, D., Haque, A., Rahman, M., & Hossain, M. S. (2021). Moderating role of psychological empowerment on the relationship between green HRM practices and millennial employee retention in the hotel industry of Bangladesh. Business Strategy & Development, 5(1), 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsd2.180

- Islam, M. A., Jantan, A. H., Yusoff, Y. M., Chong, C. W., & Hossain, M. S. (2023). Green human resource management (GHRM) practices and millennial employees’ turnover intentions in tourism industry in Malaysia: Moderating role of work environment. Global Business Review, 24(4), 642–662. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150920907000

- Ivanovic, T., & Ivancevic, S. (2018). Turnover intentions and job hopping among millennials in Serbia. Management:Journal of Sustainable Business and Management Solutions in Emerging Economies, 24(1), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.7595/management.fon.2018.0023

- Jain, N. D. C., & Lima, N. A. (2018). Green HRM: A study on the perception of Generation Y as prospective internal customers. International Journal of Business Excellence, 15(2), 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBEX.2018.091916

- Jordan, S. L., Ferris, G. R., & Lamont, B. T. (2019). A framework for understanding the effects of past experiences on justice expectations and perceptions of human resource inclusion practices. Human Resource Management Review, 29(3), 386–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2018.07.003

- Judeh, M., & Abou-Moghli, A. A. (2019). Transformational leadership and employee intent to stay: Mediating effect of employee self-efficacy. International Journal of Academic Research Business and Social Sciences, 9(12), 301–314. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v9-i12/6725

- Khalifa Alhitmi, H., Shah, S. H. A., Kishwer, R., Aman, N., Fahlevi, M., Aljuaid, M., & Heidler, P. (2023). Marketing from leadership to innovation: A mediated moderation model investigating how transformational leadership impacts employees’ innovative behavior. Sustainability, 15(22), 16087. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152216087

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100101

- Kowalski, T. H. P., & Loretto, W. (2017). Well-being and HRM in the changing workplace. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(16), 2229–2255. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1345205

- Kryscynski, D. (2021). Firm-specific worker incentives, employee retention, and wage–tenure slopes. Organization Science, 32(2), 352–375. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2020.1393

- Kuldeep, C., Rojhe, V., Singh, N., & Rao, A. (2021). Investigating talent management as a strategy to promote employee retention in higher education institutions. In Emerging trends in management sciences. YICCISS.

- Kuria, M. W., & Mose, T. (2019). Effect of green human resource management practices on organizational effectiveness of universities in Kenya. Human Resource and Leadership Journal, 4(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.47941/hrlj.319

- Kuron, L. K. J., Lyons, S. T., Schweitzer, L., & Ng, E. S. W. (2015). Millennials’ work values: Differences across the school to work transition. Personnel Review, 44(6), 991–1009. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-01-2014-0024

- Leidner, S., Baden, D., & Ashleigh, M. J. (2019). Green (environmental) HRM: Aligning ideals with appropriate practices. Personnel Review, 48(5), 1169–1185. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-12-2017-0382

- Lind, D. A., Marchal, W. G., & Wathen, S. A. (2018). Statistical techniques in business & economics (17th ed., p. 897). McGraw Hill Education.

- Linden, S. (2015). Job expectations of employees in the millennial generation [Dissertation], Walden University]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1721470393?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true&sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses

- Lindquist, T. M. (2008). Recruiting the millennium generation: The new CPA. The CPA Journal, 78(8), 56.

- Liu, J., Zhu, Y., Serapio, M. G., & Cavusgil, S. T. (2019). The new generation of millennial entrepreneurs: A review and call for research. International Business Review, 28(5), 101581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2019.05.001

- Luscombe, J., Lewis, I., & Biggs, H. C. (2013). Essential elements for recruitment and retention: Generation Y. Education + Training, 55(3), 272–290. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911311309323

- Luthans, F., & Peterson, S. J. (2002). Employee engagement and manager self-efficacy. Journal of Management Development, 21(5), 376–387. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710210426864

- Maden, C., Ozcelik, H., & Karacay, G. (2016). Exploring employees’ responses to unmet job expectations: The moderating role of future job expectations and efficacy beliefs. Personnel Review, 45(1), 4–28. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-07-2014-0156