Abstract

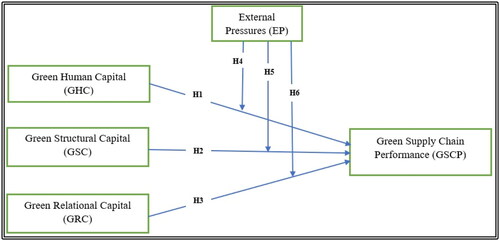

This paper examines the impact of Green Intellectual Capital (GIC) on Green Supply Chain Performance (GSCP). Further, the study examines the moderating role of external pressures (EP) on the relationship between GIC and GSCP. Data were collected from employees working in Egyptian hotels and tourism companies (N = 366). The collected data were analyzed using smart partial least squares (Smart-PLS) software. The current research indicated that there is a positive and significant impact of all GIC components on GSCP. The results also revealed that EP were found to moderate the relationship between GIC and GSCP. The study model was able to explain 63.1% of the variance in GSCP. The findings of this study serve as a pivotal yardstick for guiding corporate policy formulation, offering valuable insights to drive continuous improvements in supply chain management and performance. Furthermore, the research holds substantial implications for managerial strategies by shedding light on the potential of GIC and EP to elevate GSCP. Positioned as one of the initial studies to delve into the moderating role of EP in the relationship between GIC and GSCP, this research offers insights within an emerging market context.

1. Introduction

In the context of escalating global warming, dynamic changes in biodiversity, and the emergence of global health issues like Covid-19 pandemic (Joshi & Sharma, Citation2022), there has been a discernible adverse impact on the planet sustainability (Mohamed, Citation2023; Saeed et al., Citation2018). Consequently, a focal point for researchers, and practitioners lies in the identification and implementation of efficacious strategies aimed at fostering competitive advantage (Al-Khatib & Shuhaiber, Citation2022; Liao & Hu, Citation2007), through concentrating on environmental sustainability (Mohamed, Citation2023). Notably, manufacturing and service enterprises are alike seeking long-term sustainability objectives, primarily by curbing all sorts of pollution and demonstrating heightened awareness of the surrounding ecological milieu. In essence, these enterprises are urged to embrace the philosophy of “Going Green,” through concerting their efforts towards addressing the environmental ramifications in all their operations (Ahmed, Citation2022; Bansal & Roth, Citation2000).

The COVID-19 pandemic and the related disruptions have sparked heightened interest of practitioners and researchers to creating innovative practices to face such sudden change (Boiral et al., Citation2021; Gregurec et al., Citation2021; Naseeb & Metwally, Citation2022). The pervasive impact of the pandemic and telework mode has fundamentally altered the conception of corporate social responsibility and its related societal and business landscapes across nations (Donthu & Gustafsson, Citation2020; Kwok & Koh, Citation2021; Metwally et al., Citation2022), giving rise to innovative and ambitious environments while concurrently introducing significant upheavals within the business sphere (Al-Khatib & Shuhaiber, Citation2022; Altig et al., Citation2020; Sharma et al., Citation2020). All business activities including supply chain were impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic (Joshi & Sharma, Citation2022). The pandemic’s pervasive effect, characterized by recurrent closures and precautionary measures implemented by nations, has engendered disruptions and discontinuities in supply chains (Hohenstein, Citation2022; Metwally et al., Citation2020). Consequently, business organizations have experienced a concomitant erosion of their competitive value.

Moreover, the challenges stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic have reverberated across managerial, governmental, and public policy domains (Naseeb et al., Citation2020). Decision-making processes, particularly those pertaining to supply chain sustainability and the delicate equilibrium of local and global markets demand and supply (Muhammad et al., Citation2022; Tirkolaee et al., Citation2022), were characterized by heightened risks and uncertainties (Metwally et al., Citation2019; Metwally & Diab, Citation2023). Notably, amidst the myriad challenges, longstanding concerns related to environmental issues have garnered increased attention, signifying a departure from prior neglect, and prompting a reevaluation of their significance (Al-Khatib & Shuhaiber, Citation2022; Kusi-Sarpong et al., Citation2022). Having said this, it is apparent that the prosperity of organizations and enterprises is contingent upon the condition of their external environment, emphasizing the crucial aspects of cleanliness and safety. Further, environmental dimension is no longer a discretionary consideration for firms; rather, it has evolved into a strategic imperative and a competitive necessity for the establishment of competitive advantages (Al-Khatib & Shuhaiber, Citation2022; Frare & Beuren, Citation2022).

Within the literature of Management Accounting (MA), there is widespread acknowledgment of the integration of corporate strategic plans, with a particular emphasis on prioritizing sustainability initiatives (Asiaei et al., Citation2021). Sustainability control systems are theorized to assume a multifaceted role, not solely confined to enabling top management’s execution of sustainability initiatives through the promotion of core values and performance measurement (Arjaliès & Mundy, Citation2013). This strand of research deploys Resource-Based View (RBV) theory to explain that organizations endeavor to cultivate a sustainable competitive advantage by leveraging the outcomes derived from diverse resources. The strategic synthesis of these resources with various activities enables adding value not only to products but to services as well (Nagano, Citation2020). Building upon the RBV framework, scholars argue that organizations, driven by an interest in the external environment, can optimize the utilization of natural resources while concurrently minimizing waste (Barney et al., Citation2010; Hart, Citation1995). This strategic orientation can, in turn, propel these organizations towards attaining a competitive advantage (Al-Khatib & Shuhaiber, Citation2022).

While the Resource-Based View (RBV) offers valuable insights into competitive advantage, its valuation of intangible assets can be fraught with difficulty (Delgado-Verde et al., Citation2014; Jardon & Martínez-Cobas, Citation2019). This limitation sparked the emergence of two alternative perspectives: the Knowledge-Based View (KBV) and the Intellectual Capital-Based View (Delgado-Verde et al., Citation2014). KBV diverges from RBV by placing knowledge at the center of its analysis. Firms, through this lens, become dynamic entities actively engaged in the creation, storage, and application of knowledge (Delgado-Verde et al., Citation2014).

The other alternative theory is the Intellectual Capital-Based View (ICBV) which builds on RBV and directly embraces knowledge management practices (Jardon & Martínez-Cobas, Citation2019; Martín-de-Castro et al., Citation2011; Reed et al., Citation2006). This approach fills a gap in RBV, specifically its lack of clear measurement for intangible assets (Reed et al., Citation2006). By defining intellectual capital with elements like patents and tacit knowledge, ICBV offers a more concrete framework for analysis and testing. The current study will follow the ICBV in defining intellectual capital which encapsulates a firm’s unique knowledge stock, constituting a competitive advantage. This stock encompasses distinct knowledge embedded within the firm’s human (employee skills and expertise), structural (processes and routines), and relational (external partnerships) capital (Delgado-Verde et al., Citation2014; Reed et al., Citation2006).

Certainly, the imperative of supply chain sustainability emerges as a central facet in the pursuit of heightened value creation for customers (Avilés-González et al., Citation2017). Defined as an intricate web of interconnected relationships, the supply chain serves as a mechanism engineered to bolster profitability and furnish additional value to customers. The deliberate emphasis of organizations on the fluidity of products and services from production to end-users not only fosters customer satisfaction but also bestows a competitive advantage (Ivanov et al., Citation2017). Amidst the prevailing global environmental challenges, the concerted efforts of organizations in championing environmental initiatives within the supply chain are poised to optimize resource utilization, amplify operational efficiency, and abate the generation of waste (Al-Khatib & Shuhaiber, Citation2022; Permatasari et al., Citation2023).

As a result, such endeavors will facilitate realizing the socio-political, economic, and environmental sustainability objectives (Sony, Citation2019). This shift towards environmental responsibility, particularly in the context of green business aspects like Green Supply Chain Management (GSCM), is underscored by organizational and ethical pressures compelling firms to align with environmentally responsible practices (Liu et al., Citation2023; Park et al., Citation2022). GSCM is delineated as a set of managerial activities that devotes heightened attention to environmental concerns within the traditional supply chain framework (Abbas & Hussien, Citation2021; Ahmed, Citation2022; Micheli et al., Citation2020; Phuah & Fernando, Citation2015).

The efficacy of moving towards green supply chain can be gauged through diverse indicators, encompassing (a) the provision of environmentally friendly products and services, (b) the incorporation of novel and sustainable packaging methods, and (c) the curtailment of energy and natural resource waste (Jo & Kwon, Citation2021; Wu et al., Citation2012; Zhu et al., Citation2008b). Achieving these objectives necessitates the alignment of all resources, knowledge, and intellectual capabilities (Al-Khatib & Shuhaiber, Citation2022). Prior literature has accentuated the pivotal and constructive influence of intellectual capital in augmenting resources for the establishment and sustaining competitive advantages and overall enhancement of corporate performance (Al-Khatib, Citation2022; Dost et al., Citation2016). Given the acknowledged significance of intellectual capital as a precursor to performance improvement, several antecedent studies have concentrated on elucidating the positive association between GIC and GSCP (Al-Khatib, Citation2022; Al-Khatib & Shuhaiber, Citation2022; Khan et al., Citation2021; Mubarik et al., Citation2022; Shou et al., Citation2018; Shou et al., Citation2020).

The utilization of knowledge and skills, coupled with the effective deployment of intellectual capital by firms, amplifies their capacity for innovation. This innovation, in turn, has the potential to engender novel approaches for enhancing the supply chain. Hence, supply chain performance improvement not only amplifies operational efficiency but also augments value for customers (Al-Khatib & Shuhaiber, Citation2022).

Viewed through the framework of management control and environmental management, GIC is conceptualized as the amalgamation of existing skills and knowledge deployed within an organization for both organizational and environmentally activities and processes, thereby bestowing a competitive advantage (Malik et al., Citation2020; Yusliza et al., Citation2020). Rooted in the knowledge-based theory, it is posited that GIC plays a pivotal role in promoting knowledge sharing and experiences among individuals within the organization. This, in turn, is expected to facilitate the exchange of knowledge regarding environmental aspects and skills necessary for achieving sustainable performance outcomes (Yong et al., Citation2019; Yusliza et al., Citation2020).

Consequently, the strategic utilization of intellectual capital geared towards environmental initiatives by firms serves to enhance GSCP. This is achieved through the employment of novel skills and knowledge to elevate the operational efficacy and enhance GSCP (Dang & Wang, Citation2022; Khan et al., Citation2021; Ullah et al., Citation2022). Moreover, the judicious use of information resources and the adept management of information flow within supply chains augment organizational capabilities to confront operational risks and expedite firms’ responses to diverse environmental changes (Wankmüller & Reiner, Citation2020). This, in turn, contributes to an overall enhancement of GSCP (Al-Khatib & Shuhaiber, Citation2022; Jemai et al., Citation2020; Micheli et al., Citation2020).

Within the MA literature, empirical investigations highlight institutional theory as the predominantly employed theoretical framework in understanding change in all organizational aspects including GSCM. Institutional theory serves as a valuable tool for comprehending external factors that compel organizations to embrace specific activities or processes in response to pressures from government, community social norms, suppliers, or customers (Geng et al., Citation2017).

While institutional theory is extensively utilized to elucidate EP as precursors to the adoption of GSCM and their subsequent performance outcomes, it lacks prescriptive guidance for the actual execution of GSCM. Given the distinct cultural, legal, ethical, political, and behavioral contexts prevalent in different countries, these factors introduce additional dimensions that shape the dynamics of how these pressures affect the implementation processes and how those shape the end performance (Geng et al., Citation2017; Sarkis, Citation2012; Vanalle et al., Citation2017).

Particularly in developing countries where GSCM is still evolving, there exists a scarcity of studies examining environmental practices and their nexus with GSCP (Liu et al., Citation2015; Seuring & Gold, Citation2013). Calls within the literature emphasize the necessity to extend investigations into the impact of theories across diverse cultures to garner a more comprehensive understanding of their influence on implementation and performance outcomes (Diab & Metwally, Citation2020; Diab & Mohamed Metwally, Citation2019; Metwally & Diab, Citation2023).

Moreover, the interplay of governmental pressures, environmental regulations, and the emulation of successful models holds the potential to enhance organizational activities and bolster process efficiency, leading to a reduction of waste within the supply chain (Qi et al., Citation2021). This phenomenon is observable across various industries, and spans both developed and developing countries (Al-Khatib & Shuhaiber, Citation2022).

Hotels and tourism industry play a crucial role in Egypt’s economy and are significant contributors to the country’s overall development as the returns reached more than 13.6 $ billion in 2023 (Ahram, Citation2023). This sector represents one of the main industries that the Egyptian government care for and enhance its control, accountability, and environmental impact. This governmental care is made for many reasons. Tourism and hotels is very sensitive and changing sector as it face may vulnerabilities (El-Masry et al., Citation2022), contribute to the national income billions of foreign currencies annually, reduce overall unemployment rate in the country, increase the demand on local commodities, and in return enhance social and cultural dimensions (Elnagar & Derbali, Citation2020).

To keep this sector safe from climate change that is expected to produce heat waves, dust storms, storms along the Mediterranean coast and extreme weather events (UNICEF, Citation2023). These changes may affect the marine life in the Egyptian resorts and may affect the existence of some of the monuments in ancient Egyptian temples. These challenges pushed Egyptian government to move from its low ranking in the Sustainable Development Growth (SDG) Index, positioned at 82nd out of 165 countries with a score of 68.6 out of 100. The Sustainability Index for Egypt (S&P/EGX ESG) recorded a 7.4% decline in 2019, further emphasizing concerns about environmental sustainability in the country. These indices collectively highlight a pronounced challenge in achieving environmental sustainability in Egypt (Mohamed, Citation2023). Consequently, since 2021 and after the negative impact of covid-19, Egypt has implemented strict measures to address environmental concerns, including legislative initiatives and innovative financing mechanisms such as green bonds. The country has also set ambitious goals, encompassing wind energy, electric transport projects, green hydrogen production, solar energy, and low-carbon initiatives (Mohamed, Citation2023).

The above mentioned regulatory and structural changes in the Egyptian environment necessitates studying what are the implications of such change in the macro level on the operations of a big sector like hotels and tourism. The overarching objective of this investigation was to address two distinct research questions (RQs). The specific inquiries are outlined as follows:

RQ1: To what extent does GIC influence GSCP in the Egyptian hotels and tourism sector?

RQ2: Do EP exert a moderating influence on the relationship between GIC and GSCP in the Egyptian hotels and tourism sector?

2. Theoretical framework and hypotheses development

2.1. GIC and GSCP

2.1.1. Green human capital and GSCP

In the supply chain literature GSCM represents a contemporary paradigm aimed at environmental risk mitigation and waste reduction (Jabbour & de Sousa Jabbour, Citation2016; Sarkis, Citation2012). This concept is characterized by an integrative approach, emphasizing the amalgamation of environmental dimensions with traditional facets inherent in the supply chain framework (Kache & Seuring, Citation2017). GSCM, in essence, centers on the comprehensive evaluation of the environmental impact of products throughout all production stages, culminating in their delivery to the end customer (Lam et al., Citation2015).

Companies demonstrating a tendency to integrate environmental management practices into their supply chain operations are positioned to reduce waste, improve efficiency, and subsequently elevate the degree of sustainability (Bag & Rahman, Citation2023; Islam & Khan, Citation2013). Seminal investigations emphasize the transformative capacity of Green Supply Chain in enhancing GSCP by promoting the adoption of eco-friendly systems and incorporating technologies that mitigates negative impacts on the environment (Adhikari et al., Citation2019; Taş & Akcan, Citation2022). This, in turn, results in enhanced operations that reduce the costs across the chain operations (Jum’a et al., Citation2022), and enhance the reputation of participating companies (Do et al., Citation2020).

Numerous metrics have been postulated to gauge the GSCP (Mishra et al., Citation2017). The evaluation of GSCP extends to quantifying their effectiveness in mitigating adverse environmental impacts, including but not limited to air and water pollution (Jin, Citation2021; Pham & Pham, Citation2021; Thennal VenkatesaNarayanan et al., Citation2021). Additionally, the appraisal of GSCP encompasses the extent to which these chains optimize resource utilization, subsequently leading to waste reduction (Peng et al., Citation2020).

Green supply chains contribute to enhancing efficiency in firms’ processes and activities which in turn enhance firms’ sustainability and performance (Jemai et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, the impact of green supply chains extends to augmenting firms’ responsiveness to markets, fostering innovation in new products development (Daddi et al., Citation2021). Additionally, the adoption of green supply chains elevates the planning and implementation of proper CSR strategies, thereby fostering long-term improvements in the firms’ reputation (Huang et al., Citation2021).

Viewed through the framework of management control and sustainability perspectives GIC can be seen to be rooted in the knowledge-based theory, it is posited that GIC plays a pivotal role in promoting knowledge sharing and experiences among individuals within the organization. This, in turn, is expected to facilitate the exchange of knowledge regarding environmental aspects and skills necessary for achieving sustainable performance outcomes (Yong et al., Citation2019; Yusliza et al., Citation2020). An alternative view can be made through deploying Resource-Based View (RBV) theory to explain that organizations endeavor to cultivate sustainable competitive advantage. The strategic synthesis of these resources with various activities enables adding value not only to products but to services as well (Nagano, Citation2020). Building upon the RBV framework, scholars argue that organizations, driven by an interest in the external environment, can optimize the utilization of natural resources while concurrently minimizing waste (Barney et al., Citation2010; Hart, Citation1995). This strategic orientation can, in turn, propel these organizations towards attaining a competitive advantage (Al-Khatib & Shuhaiber, Citation2022).

While the Resource-Based View (RBV) offers valuable insights into competitive advantage, its valuation of intangible assets can be fraught with difficulty (Delgado-Verde et al., Citation2014; Jardon & Martínez-Cobas, Citation2019). The current study will follow the ICBV in defining intellectual capital to overcome the problems related to ignoring the intangible assets in the BBV. Having said this, the current study will concentrate on the three components of IC namely firm’s human capital (employee skills and expertise), structural capital (processes and routines), and relational capital (external partnerships) capital (Delgado-Verde et al., Citation2014; Reed et al., Citation2006).

To ensure the efficacy of GSCM and the enhancement of firms’ environmental performance, extant studies within the literature, exemplified by (Ganbold et al., Citation2021; Reaidy et al., Citation2021; Shah & Soomro, Citation2021), underscore the pivotal role of going green initiatives and how integrating environmental aspects in the chains enhance their performance. This integration manifests in various dimensions, including environmental cooperation with customers, where information pertaining to environment is shared with customers to foster improved green practices (Shah & Soomro, Citation2021). Furthermore, supplier integration entails fostering sustained collaborative partnerships between the organization and crucial suppliers, with a specific emphasis on strategic coordination in environmental initiatives and activities. This collaborative approach extends to joint decision-making processes related to environmental aspects (Zhang et al., Citation2020).

Further, GSCM enhancement hinges significantly on green internal integration, which revolves around orchestrating organizational endeavors spearheaded by senior management. This encompasses disseminating these initiatives throughout all organizational units and departments dedicated to devising and executing environmental initiatives within the supply chain (Song et al., Citation2017; Wong et al., Citation2020).

Numerous investigations have substantiated a strong correlation between green human capital (GHC) and GSCP (Chen, Citation2008; Maaz et al., Citation2022), concomitant with enhancements in sustainable performance (Jirakraisiri et al., Citation2021). Traditionally, human capital refers to the collective skills, knowledge, expertise, and capabilities possessed by individuals within a workforce or a particular organization. It encompasses the education, training, experience, and talents of individuals, which contribute to their ability to perform tasks, solve problems, and drive innovation within the organizational context (Kramer & Kroon, Citation2020).

From the perspective of the Natural Resource-Based View (NRBV), GHC encompasses the accrued experiences, capabilities, knowledge, and skill of employees pertinent to the surrounding environment, its protection, and being aware of the dangers that may harm it (Shoaib et al., Citation2021). Despite the inherent challenge in maintaining human capital due to the intangibility of Conserving established concepts within the cognitive domain of employees, human capital holds the potential to confer distinctive competitive advantages upon firms by fostering the generation of novel ideas and innovations (Al-Khatib, Citation2022; Mosey & Wright, Citation2007). Consequently, intellectual capital emerges as a critical determinant and precursor to success and performance enhancement (Curado, Citation2008; Kryscynski et al., Citation2021). In line with this perspective, (Bag & Gupta, Citation2020; Chiappetta Jabbour et al., Citation2019) underscore the significance of GHC as a fundamental resource in implementing GSCM practices.

Many studies in the literature have deliberated on the significance of GHC as a pivotal determinant for the success of GSCM (Agyabeng-Mensah & Tang, Citation2021; Yong et al., Citation2020; Yusoff et al., Citation2019). The acquisition of fundamental knowledge and skills by GHC enables the adept resolution of environmental challenges (Jirakraisiri et al., Citation2021), consequently enhancing the efficiency of processes (Sheikh, Citation2022). Furthermore, the presence of GHC catalyzes the generation of novel ideas, giving rise to unique environmental innovations that were hitherto non-existent and contributing to the enhancement of GSCP (Song et al., Citation2021). Further, numerous studies have underscored that GHC exhibits heightened receptivity to training and learning initiatives concerning environmental aspects. This receptivity, in turn, contributes to the augmentation of efficiency in GSCP by enhancing employees’ capabilities to address environmental risks (Acquah et al., Citation2021; Agyabeng-Mensah et al., Citation2019). Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: A positive association exists between the use of GHC and GSCP.

2.1.2. Green structural capital and GSCP

Structural capital pertains to the organizational capabilities inherent in firms, facilitating the transformation of ideas and innovations generated by staff into tangible and practicable assets that are accessible and exploitable within the organizational framework (Barão & da Silva, Citation2014; Chu et al., Citation2006). It may be interpreted as the accumulated result of knowledge gained through daily activities, knowledge sharing among employees, and interactions with external entities such as customers or suppliers (Barbery & Torres, Citation2019). Typically involving a range of procedures, policies, patents, knowledge repositories, and data (Asiaei et al., Citation2018), structural capital collaborates with human capital to furnish solutions to challenges confronted by the firm (Alkhatib & Valeri, Citation2024; Ullah et al., Citation2022).

Green structural capital (GSC) comprises a set of organizational capabilities, encompassing systems, protocols, databases, and patents focused on environmental preservation and adherence to green principles. These assets are owned and employed by the company (Benevene et al., Citation2021; Chen, Citation2008). This specialized form of structural capital plays a pivotal role in facilitating initiatives to protect the environment by furnishing essential infrastructure support for such endeavors (Amores-Salvadó et al., Citation2021; Yusoff et al., Citation2019). Additionally, GSC can aid management efforts in changing the dominating culture in the organization towards a more environmentally aware and caring culture (Koc & Ceylan, Citation2007). Its influence extends to guiding employees toward optimal environmental practices, providing support, and directing environmental programs within the organizational framework (Benevene et al., Citation2021).

The proclivity of companies towards engaging in CSR practices and their attentiveness to environmental concerns play a crucial role in enhancing the significance of GSC (Maaz et al., Citation2022). The prioritization of green orientation by senior management makes these companies more prone to integrating the experiences and knowledge held by employees, forming GHC, into everyday internal knowledge (Secundo et al., Citation2020). This internal knowledge is strategically employed for the formulation and execution of green programs and initiatives within the organizational framework.

Numerous investigations have substantiated the positive association between GSC and the enhancement of performance and sustainability (Al-Khatib & Shuhaiber, Citation2022), concurrently fostering the creation of competitive advantages (Susandya et al., Citation2019). Within the literature, GSC assumes a pivotal role in augmenting GSCP. This is accomplished by fostering the exchange of knowledge among all stakeholders aiming for having successful environmental plans (Ullah et al., Citation2022). Moreover, GSC empowers firms to harness their real capabilities aligning with the predetermined goals regarding higher GSCP which will lead to sustainable development and protecting the environment (Khan et al., Citation2021; Yong et al., Citation2019; Yusliza et al., Citation2020).

Despite the acknowledged significance of structural and its integral contribution in attaining sustainable development and enhancing performance, extant studies have confirmed that GSC contributes to the improvement of GSCP. This improvement is realized through the integration of organizational knowledge and technology capabilities within the supply chain, yielding superior performance outcomes (Mubarik et al., Citation2022)[36]. To enhance GSCP, a strategic focus on cultivating and developing key relationships with main stakeholders (i.e. customers and suppliers) is deemed imperative (Yu et al., Citation2021). Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: A positive association exists between the use of GSC and GSCP.

2.1.3. Green relational capital and GSCP

Firms possess the capacity to add value and gain competitive advantages by leveraging their network of relationships (Al-Khatib, Citation2022). Relational capital encompasses the firm’s proficiency in engaging with influential stakeholders in their context (Barbery & Torres, Citation2019). These relationships encapsulate the value garnered from internal or external sources (Al-Khatib, Citation2022). Relational capital plays a pivotal role in facilitating access to scarce resources, unavailable or hard to get information and knowledge, finally influential expertise through collaborative exchanges with associated parties (Xu et al., Citation2019). This collaborative engagement creates value for the firm’s customers by augmenting the production of competitive novel production (Alves et al., Citation2021).

Green Relational Capital (GRC) denotes the firm’s associations with primary stakeholders on matters related to environment and its management. These associations contribute significantly to gaining competitive advantage (Atiku, Citation2019). GRC serves as a source of information regarding the firm’s CSR practices and plans (Chen & Chang, Citation2013). This, in turn, fosters trust between stakeholders and the organization management (Al-Khatib, Citation2022). Additionally, the firm stands to benefit from GRC by enhancing learning, training, and accesses to knowledge capabilities (Benevene et al., Citation2021). This augmentation in capabilities elevates knowledge within the firm, subsequently leading to the emergence of novel green innovations (Rehman et al., Citation2021).

Numerous scholarly inquiries substantiate a positive correlation between GRC and GSCP. As elucidated by Wu et al. (Citation2022), the cultivation of GRC by firms engenders extensive sharing of information relating to environment among stakeholders, thereby diminishing waste and enhancing operational efficiency. Moreover, Lo et al. (Citation2018) underscores the pivotal role of GRC in fostering strategic alliances with stakeholders grounded in environmental stewardship, lending support to green manufacturing, and advancing environmental strategies throughout the entire supply chain (Yu & Huo, Citation2019).

Organizations emphasizing the establishment of strategic relationships rooted in environmental considerations can foster collaboration in quality management. This collaboration contributes to efficiency in using scarce resources and enhancing performance by curbing operational costs (Wu et al., Citation2022). Aligned with social capital theory, the establishment of enduring cooperative relationships among the firm, suppliers, and all collaborating entities is deemed a fundamental requisite for supply chain success (Wu et al., Citation2012). Consequently, GRC serves to intensify cooperation within the green supply chain, thereby augmenting overall performance (Yu & Huo, Citation2019). Emphasizing the significance of such collaboration, Pimentel Claro et al. (Citation2006) highlights its positive impact on addressing environmental and operational risks, as well as facilitating knowledge sharing among all involved parties. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: A positive association exists between the use of GRC and GSCP.

2.2. The impact of institutional pressures: External pressures moderating role

Numerous scholarly investigations have delved into the elements influencing the execution, methodologies, and outcomes of GSCP (Liu et al., Citation2012; Saeed et al., Citation2018; Wang & Zhang, Citation2023; Zhu et al., Citation2008a). These studies concluded that external pressures from government, laws and regulations, competitors, and clients directly and positively affect GSCM implementation and performance (Hall, Citation2000). Various theoretical perspectives, including stakeholder theory, institutional theory, and the RBV, have been employed to examine GSCM practices. In the current study we will concentrate on institutional theory as a proper way to explain external pressures in the name of institutional pressures.

Institutional theory views organizations as integral parts of a social system with distinct cultures and values, beyond mere production systems. Organizational decision-making operates within a framework of cultural values, norms, and behaviors shaped by external environmental influences (Gualandris & Kalchschmidt, Citation2014; Scott, Citation1987). Institutional theory perceives organizations as essential components of a broader social system characterized by unique cultures and values, extending beyond mere production systems. Decision-making within organizations is guided by a framework of cultural values, norms, and behaviors that are influenced by external environmental factors (Williams et al., Citation2009). This theory helps in comprehending the diverse external factors that compel organizations to initiate or adopt new practices (de Grosbois, Citation2016; DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983). In the context of institutional theory, three types of isomorphic pressures are emphasized. Coercive pressures encompass influences exerted by influential organizations upon firms, involving specific resources, adherence to legal requirements, or societal expectations (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983). The government holds the capability to apply external influence on companies through avenues such as tax deductions, subsidies, financing at low-interest rates, and a range of other incentives (Nie et al., Citation2016; Russi et al., Citation2016). Nevertheless, corporations could encounter potential bans or financial penalties for failure to adhere to certain governmental laws or regulations (Sarkis et al., Citation2010; Yang, Citation2018).

Normative pressures originate from the norms and standards established by the environment, grounded in cultural expectations within that particular context (Khalifa & Davison, Citation2006). Normative pressures can stem from a variety of sources, including educational institutions influencing cognitive behavior, industry professionals associated with groups and associations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) with a vested interest in a specific industry, and the broader public (Chu et al., Citation2017; DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983; Zhu et al., Citation2013). Suppliers and customers also constitute core components of these pressures (Chu et al., Citation2017; Zhu et al., Citation2013). Mimetic pressures influence organizations to mitigate uncertainty and risk by emulating or replicating processes or structures of other successful institutions (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983). In the face of significant changes in the external environment posing threats to their existence, organizations seek role models believed to have successfully confronted such challenges, endeavoring to modify themselves based on the practices of these exemplary organizations (Williams et al., Citation2009).

Within the framework of Institutional theory, organizations are compelled to adopt green practices for two main reasons: (1) compliance with laws, taxes, and fines, overseen by regulatory bodies either under government jurisdiction or industrial bodies; and (2) incentivizing the adoption of superior environmental and social practices. As a result, institutional pressures play a crucial role in motivating organizations to implement internal GSCM practices (Hanim Mohamad Zailani et al., Citation2012).

In a separate investigation conducted by Hanim Mohamad Zailani et al. (Citation2012), noteworthy findings revealed a substantial positive impact of coercive pressures (regulation and incentives) and normative pressures (customer influence) on the adoption of GSCM. This adoption, in turn, contributed to elevated environmental performance within the organization. Specifically, normative pressures originating from suppliers, customers, and the broader market were identified as significant influencers prompting the adoption (Zhu et al., Citation2013).

Likewise, in the event that a prominent competitor, having embraced a green strategy, garners favor from customers, it is probable that other companies within the same industry will tend to emulate such practices (Chu et al., Citation2018; Qi et al., Citation2021). Prior research has demonstrated that these three types of pressures can exert a positive influence on e-commerce transformation intention (Lin et al., Citation2020) and motivate firms to adopt sustainable supply chain management practices (Dai et al., Citation2021).

In the context of institutional theory, coercive, normative, and mimetic pressures are identified as factors impacting firms’ adoption of green product practices (Huang & Chen, Citation2022). In the contrary to this positive impact that institutional pressures have on the change process, many studies in the literature discussed decoupling in practice as a response to institutional pressures (Diab & Metwally, Citation2020; Diab & Mohamed Metwally, Citation2019; Hu et al., Citation2022; Metwally & Diab, Citation2021, Citation2023; Shahzad et al., Citation2022). Decoupling occurs when pressures fail to enhance or speed up the change process, if the social norm in the company or there are no successful competitor to follow and the only apparent pressure is coercive pressure, the pressures fail to change the status quo (Diab & Mohamed Metwally, Citation2019; Metwally & Diab, Citation2021). Unfortunately, either the pressures have no impact on the change or have a negative impact especially on the overall performance, as implicit resistance and showing up that the company is implementing while it is not will be the prevailing norm (Diab & Metwally, Citation2020; Diab & Mohamed Metwally, Citation2019; Hu et al., Citation2022; Metwally & Diab, Citation2021, Citation2023; Shahzad et al., Citation2022). Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4: EP moderate the relationship between GHC and GSCP.

H5: EP moderate the relationship between GSC and GSCP.

H6: EP moderate the relationship between GRC and GSCP.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Measures and scale development

To evaluate the suggested hypotheses illustrated in , the employed methodology involved the utilization of the quantitative-deductive causal approach, which centers on the examination of hypotheses and causal connections. This approach facilitates the evaluation of the statistical associations between various constructs, thereby yielding an empirical comprehension of the associations between these constructs (Al-Khatib & Shuhaiber, Citation2022). Having said this, a survey was formulated according to existing research. The study variables’ measurements were borrowed from prior studies and adjusted as necessary to align with the present study’s context (Al-Khatib & Shuhaiber, Citation2022; Liu et al., Citation2012). A survey was administered to a sample of academic experts specializing in supply chain management and business analytics. The scale was fine-tuned based on their feedback. Following this, the scale was translated from English to Arabic, the local language in Egypt, to enhance accessibility for a broader participant base. The survey items were structured using a Likert scale with five points (1 being strongly disagree and 5 being strongly agree) to assess participants’ responses to the questionnaire items.

The survey in this study comprised two sections. The initial part focused on gathering written informed consent from participants, during which individuals explicitly expressed their willingness to participate in the study. then it was followed by gathering information about participants’ demographic characteristic. and the second section of the study delved into various aspects. The GIC scale, consisting of 16 items (GHC, GSC, and GRC), was employed, derived from the works of (Al-Khatib & Shuhaiber, Citation2022; Chen, Citation2008; Jirakraisiri et al., Citation2021; Maaz et al., Citation2022). Additionally, the EP scale, comprising five items, was adopted from the studies of Liu et al. (Citation2012) and (Wang & Zhang, Citation2023). For the measurement of the GSCP scale, six items were utilized, adapted from the works of (Al-Khatib & Shuhaiber, Citation2022; Maaz et al., Citation2022; Peng et al., Citation2020). All the chosen scales were constructed and tested in developing countries including Asian and middle eastern contexts (i.e. Jordan, India, and China). Having said this, these scales can be suitable to the Egyptian context which share many of the regulatory, cultural, and risk factors as well as the emergence of green supply chain as a new development to their old supply chains. Testing those scales in the Egyptian context extend the literature on developing countries and enhancing the operations and performance (Abdelazim et al., Citation2023; Diab et al., Citation2023; Metwally & Diab, Citation2021).

3.2. Research sample and data collection method

Data was compiled from hotels and tourism companies in Egypt. The selection of the hotels and tourism sector was based on its significance as one of Egypt’s primary industries, making a considerable contribution to both Egyptian economic growth and GDP. This contribution results in billions of foreign currencies being added to the national income on an annual basis, resulting in a decrease in the total unemployment rate within the country. Moreover, it also generates an increased demand for local goods, thereby fostering social and cultural development (Elnagar & Derbali, Citation2020). Consequently, in light of the adverse effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, Egypt has taken decisive measures since 2021 to address environmental concerns. These measures include the introduction of legislative initiatives and innovative financing mechanisms, such as the utilization of green bonds. Furthermore, the country has set ambitious targets encompassing various initiatives, such as the production of green hydrogen, the adoption of solar and wind energy, the implementation of low-carbon projects, and the development of electric transportation systems (Mohamed, Citation2023).

In order to acquire the requisite information, a method of convenience sampling was employed, with a particular focus on individuals employed within hotels and tourism establishments in Egypt. The process of data collection for this investigation initiated in December of the year 2023 and extended over a span of two months. Out of the 500 surveys dispersed, a total of 366 were successfully finished, yielding a noteworthy response percentage of 73.2%, and notably, no data was found to be missing.

Within the 366 valid responses, it was noted that 71.8% of the participants self-identified as male, constituting a total of 263 individuals, while 28.2% identified as female, totaling 103 individuals. Regarding educational level, a significant portion of respondents (59.6%) possessed a bachelor’s degree. Additionally, a substantial proportion of respondents (54.9%) were employed in non-administrative positions, as detailed in ().

Table 1. Employees’ profile.

Employees’ responses exhibited a broad range of average scores, showing a notable difference in their responses. Additionally, the values of Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for the research’s measurement scale items were all below 5, alleviating concerns about multicollinearity, as shown in ().

Table 2. Measurement model.

3.3. Data analysis methods

With multiple direct-influencing and moderating hypotheses, this study sought to explore the causal links among various constructs. Smart partial least squares (Smart-PLS) software, a nonparametric method created especially to handle latent components that cannot be directly observed, was used in the analysis phase of the current study (Henseler et al., Citation2009). Version 4 of the Smart-PLS software utilized Structural Equation Modeling Partial Least Squares (SEM-PLS) due to its empirical model implementation mechanism. SEM-PLS is recognized for its flexibility in handling models with both causal and simultaneous relationships. Notably, it is well-suited for estimating intricate models featuring numerous constructs, indicator variables, and structural paths without imposing distributional assumptions on the data. Significantly, SEM-PLS adopts a causal-predictive approach within Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), prioritizing prediction in statistical model estimation while still providing causal explanations for the structures. This approach effectively bridges the perceived gap between the emphasis on explanation in academic research and the importance of prediction, forming the basis for deriving practical managerial implications (Hair et al., Citation2019). In the social sciences, Smart-PLS is well known for producing dependable results, especially when examining correlations between several factors (Wetzels et al., Citation2009). When employing the SEM-PLS approach, it is imperative to guarantee the fulfillment of the subsequent requisites: (a) scrutinizing the loadings of indicators, (b) evaluating the reliability of internal consistency (composite reliability), (c) appraising the convergent and discriminant validity, and (d) subjecting the relationships and hypotheses to examination via the structural model.

4. Data analysis and results

4.1. Measurement model assessment

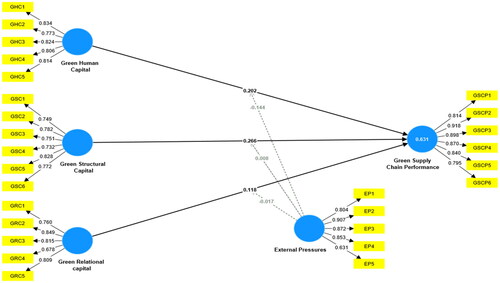

To evaluation of validity and reliability, we followed standard guidelines recommended by Hair et al. (Citation2021). This involved evaluating convergent and discriminant validity. Criteria such as C.R scores, outer loadings, and average variance extracted (AVE) values were evaluated for convergent validity. indicates that all values surpassed the recommended minimums (alpha Cronbach and C.R greater than 0.70, AVE greater than 0.50). and factor loadings above 0.70, Items with outer loadings between 0.40 and 0.70 would only be given consideration for deletion if improved composite reliability or AVE (Hair et al., Citation2021), but in this study, removal of specific items (GRC4, loading = 0.678 and EP5, loading = 0.631) would not significantly enhance these values, because the values for the construct were already above the recommended threshold. Overall, the measures used in the study were both reliable and valid (see ).

To establish discriminant validity, the study assessed cross-loadings, the Fornell-Larcker criterion, and Heterotrait Monotrait (HTMT) proportions (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Results in showed that outer-loadings for each latent variable consistently exceeded cross-loadings. revealed that AVE scores’ diagonal values were higher than inter-variable correlations, and the HTMT ratios in were below 0.90, aligning with (Leguina, Citation2015) criteria, thus reinforcing the study’s discriminant reliability.

Table 3. Cross-loadings indicators.

Table 4. Discriminant validity measures of scales.

4.2. Hypotheses testing

This study comprises six hypotheses—three direct-influencing hypotheses and three examining the moderating role of external pressures. The nonparametric bootstrapping method offered by Smart-PLS was used to test the associations between exogenous and endogenous constructs (Streukens & Leroi-Werelds, Citation2016). summarizes the results of the inner model test, illustrating path estimates and causal relationships among GIC components (GHC, GSC, and GRC) and GSCP, considering EP as a moderating construct. Path coefficients (β), calculated t values, and p values were used to assess these relationships.

presents the results of hypothesis testing, confirming the study’s proposed hypotheses (H1, H2, and H3) regarding the direct impact of GIC components on GSCP. All direct relationships were positive and statistically significant. For H1, the direct effect of GHC on GSCP was supported (β = 0.202; t-value = 2.945). Similarly, H2, focusing on the direct effect of GSC on GSCP, received support (β = 0.266; t-value = 3.640). The results of H3, exploring the direct effect of GRC on GSCP, were also positive and statistically significant (β = 0.118; t-value = 2.455).

Table 5. Structural parameter estimates.

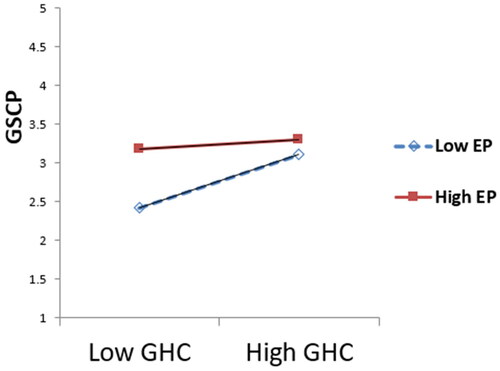

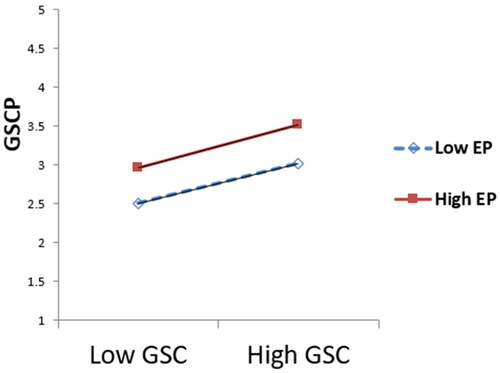

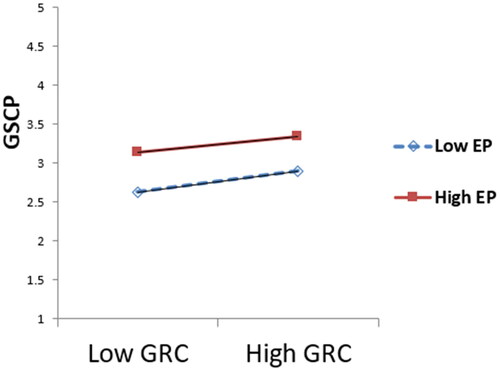

In examining the moderating role of external pressures in the relationship between GIC components and GSCP, H4 received support, while H5 and H6 did not, as their p values exceeded 0.05. The impact of external pressures on GSCP was positive and statistically significant (β = 0.240; t-value = 2.648). For H4, elucidating the moderating effect of the interaction of GHC with external pressures (GHC × EP), the result was negative and statistically significant (β = -0.144; t-value = 2.116). However, H5, explaining the moderating effect of the interaction of GSC with external pressures (GSC × EP), was not statistically significant (β = 0.008; t-value = 0.094). Similarly, H6, addressing the moderating effect of the interaction of GRC with external pressures (GRC × EP), was not statistically significant (β = -0.017; t-value = 0.305).

illustrates that the relationship between GHC and GSCP was shown to be diminished by external pressures, where the line is much steeper for Low EP, this shows that at Low level of EP, the impact of GHC on GSCP is much stronger in comparison to high EP. illustrate that external pressures have no moderating effect in the relationship between GSC and GSCP, where the line is much steeper for high EP, this shows that at high level of EP, the impact of GSC on GSCP is much stronger in comparison to Low EP. While illustrate that external pressures have no moderating effect in the relationship between GRC and GSCP, where the line is much steeper for Low EP, this shows that at Low level of EP, the impact of GRC on GSCP is much stronger in comparison to high EP. The model’s strong explanation quality and high explanation percent are indicated by the calculated R2 value of 0.63.1; as a result, the variance in endogenous constructs was 63.1 percent.

5. Discussion and conclusion

The current study examined the impact of GIC on GSCP based on the presence of external pressures from the surrounding context as a moderator in the Egyptian hotels and tourism industry. Hotels and tourism industry play a crucial role in Egypt’s economy and are significant contributors to the country’s overall development as the returns reached more than 13.6 $ billion in 2023 (Ahram, Citation2023). This sector represents one of the main industries that the Egyptian government care for and enhance its control, accountability, and environmental impact.

The study results revealed that there is a positive and significant impact of all GIC components on GSCP. Hence, all the first three hypotheses were accepted. The results also revealed that EP were found to have a negative impact on the relationship between GIC and GSCP. The percentage of the variance in GSCP was 63.1%.

Moreover, our study confirmed H1, affirming the favorable impact of GHC on GSCP. Consistent with prior research (Agyabeng-Mensah & Tang, Citation2021; Yong et al., Citation2020; Yusoff et al., Citation2019), a positive correlation was evident between GHC and GSCP. Employee expertise and proficiency in environmental matters contribute to heightened process efficiency and the mitigation of environmental risks stemming from supply chain operations (Acquah et al., Citation2021; Sheikh, Citation2022; Song et al., Citation2021). As an intangible asset, GHC significantly contributes to fostering environmental-focused organizational capabilities through the assimilation of knowledge, training initiatives, and the utilization of individuals’ tacit and accrued expertise. In that sense, Companies aspiring to attain superior GSCP can leverage the expertise of their employees by strategically investing in this organizational asset. This investment facilitates the generation of novel ideas, acquisition of skills, and development of knowledge pertaining to environmental aspects. Consequently, this approach contributes to the resolution of environmental challenges encountered within the supply chain (Jabbour & de Sousa Jabbour, Citation2016).

H2, indicating a significant and positive association between GSC and GSCP, was supported by our study. The presence of GSC notably augments the environmental performance within the supply chain. Consistent with prior research (Khan et al., Citation2021; Ullah et al., Citation2022; Yusliza et al., Citation2020), our findings align with the established causal link between GSC and enhanced GSCP. Previous studies have illustrated that GSC facilitates the advancement of firms’ environmental management capabilities (Khan et al., Citation2021; Ullah et al., Citation2022; Yusliza et al., Citation2020), thereby enabling them to achieve elevated levels of performance. Within the domain of the green supply chain (Benevene et al., Citation2021), firms leveraging structural capital dedicated to environmental initiatives employ information systems, knowledge management processes, and environmental-related systems. These practices contribute to the generation of new environmental value within manufacturing firms, consequently bolstering their sustainable performance (Al-Khatib & Shuhaiber, Citation2022).

Our study further affirmed H3, substantiating the positive influence of GRC on GSCP (Lo et al., Citation2018; Wu et al., Citation2022; Yu & Huo, Citation2019). GRC facilitates heightened collaboration on environmental dimensions by strategically leveraging relationships with key stakeholders, notably suppliers and customers (Al-Khatib & Shuhaiber, Citation2022). Prior studies have highlighted the significance of companies leveraging both internal and external connections to exchange information pertaining to environmental issues (Pimentel Claro et al., Citation2006). This practice enhances integration within the green supply chain (Wu et al., Citation2012), resulting in more efficient products and reduced operational costs throughout the supply chain (Wong et al., Citation2020). This underscores the Egyptian hotels and tourism companies’ emphasis on cultivating strategic internal and external relationships with key stakeholders, generating unique added value that significantly enhances GSCP.

The findings of the study regarding the moderating impact of EP are noteworthy, given that H4 was affirmed, while both H5 and H6 were rejected. As per the experimental outcomes, EP exhibited a moderating effect that was negative in the association between GHC and GSCP. According to institutional theory literature institutional pressures may lead to positive or negative impact. If it is giving a positive impact this means that the coercive rules and regulations are accepted by the community and became a social norm in the organization (Diab & Metwally, Citation2020; Diab & Mohamed Metwally, Citation2019; Metwally & Diab, Citation2023). While, the Egyptian government pressures the hotels and tourism companies to comply with the newly issued regulations this hinder the implementation as it faces implicit resistance and companies try to do box ticking to tell the government that we are complying while they are not, which DiMaggio and Powell (Citation1983) call decoupling in the isomorphic processes. In the contrary to this positive impact that institutional pressures have on the change process, this result conforms to many studies in the literature that discussed decoupling in practice as a response to institutional pressures (Diab & Metwally, Citation2020; Diab & Mohamed Metwally, Citation2019; Hu et al., Citation2022; Metwally & Diab, Citation2021, Citation2023; Shahzad et al., Citation2022).

With the importance of EP in improving GSCP (Dai et al., Citation2021; Hall, Citation2000; Hanim Mohamad Zailani et al., Citation2012; Lin et al., Citation2020), the empirical results revealed that there was no moderating role for EP with GRC and GSC on GSCP. Although previous literature has emphasized the importance of EP in improving GSCP, the study results are different as the Egyptian government recently though to catch up in going green and most of the pressure in the market is coercive, and by time there will be change to GSCM in Egyptian hotels and tourism companies. Giving time will lead to successful examples that mimic it as well will become a social norm in the sector to compete in the implementation process.

6. Implications

This study bears multiple theoretical implications. Its principal contribution lies in devising a conceptual model probing the relationships among GIC dimensions, EP, and GSCP within the Egyptian hotels and tourism industry. While previous studies have explored the association between GIC and GSCP, this research distinguishes itself by centering on the environmental facets of these connections and investigating the extent to which firms benefit from EP.

Grounded in Resource-Based View (RBV), the study reinforces prior findings indicating that directing organizational efforts towards bolstering robust GIC augments supply chain sustainability and elevates GSCP. However, it accentuates the discernible and substantial role of GHC in GSCP. Furthermore, this research illuminates the linkage between social capital and its interplay with environmental management and sustainability—an area warranting future exploration in academia. Nonetheless, some findings deviated from previous literature, particularly in revealing a lack of statistical significance for the interaction among EP, GSC, GRC, and GSCP.

The implications extend to administrators and supply chain managers in Egyptian hotels and tourism companies. The study confirms the positive impact of all GIC components on GSCP, prompting managers to invest in enhancing employee skills and experience, thereby elevating green capital and augmenting supply chain sustainability. Emphasis on organizational policies fostering environmental preservation, incentivizing innovative environmental thinking among employees, and documenting these innovations is crucial. The study underscores the moderating impact of EP on the relationship between GIC and GSCP, indicating the need for policymakers and managers to strategize on embedding green initiatives as social norms to counteract the adverse effects observed.

7. Limitations and future research directions

Although the study results contribute to literature and theory and have several implications, the current study faces several limitations. Its reliance on cross-sectional data necessitates caution when generalizing findings, suggesting the potential benefit of employing longitudinal or panel data for a deeper understanding of construct relationships. Additionally, exploring diverse contexts, countries, and cultures can offer richer insights into the relationships between GIC and GSCP. This can be done through integrating qualitative methods, such as interviews, alongside quantitative approaches which could enrich future investigations.

Moreover, forthcoming studies might explore intermediary concepts such as green innovation or practices in green human resource management, delving deeper into their underlying causal relationships. This could offer a more thorough comprehension of the topic by capturing subtle opinions, insights, and contextual information that may not be adequately explained by quantitative data alone.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, M.I.B.H. and A.B.M.M.; methodology, M.I.B.H. and A.B.M.M.; software, M.I.B.H. and A.B.M.M.; validation M.I.B.H. and A.B.M.M.; analysis and interpretation of the data M.I.B.H. and A.B.M.M.; the drafting of the paper M.I.B.H. and A.B.M.M.; revising it critically for intellectual content M.I.B.H. and A.B.M.M.; funding acquisition, M.I.B.H. and A.B.M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional review board statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the deanship of the scientific research ethical committee, King Faisal University (project number: 5,612, date of approval: 31 March 2024).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data are available upon request from researchers who meet the eligibility criteria. Kindly contact the corresponding author privately through e-mail.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mohammed Ibrahim Buhaya

Mohammed Ibrahim Buhaya C-KPI, CMA, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Accounting at the School of Business, King Faisal University. He holds a Master of Science in Accountancy from Akron University, USA, and a PhD in Accounting from Brighton University, UK. Dr. Bu haya has experience in administrative roles, having served as Acting Head of the Quantitative Methods Department and Vice Dean of the School of Business. His research interests center on management accounting practices and changes in management accounting.

Abdelmoneim Bahyeldin Mohamed Metwally

Abdelmoneim Bahyeldin Mohamed Metwally PhD, CMA, FHEA, is an assistant professor of accounting in College of Business Administration, King Faisal University, Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia; and an assistant professor and former head of accounting department in Faculty of Commerce, Assiut University, Assiut, Egypt.

References

- Abbas, T. M., & Hussien, F. M. (2021). The effects of green supply chain management practices on firm performance: Empirical evidence from restaurants in Egypt. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 21(3), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/14673584211011717

- Abdelazim, S. I., Metwally, A. B. M., & Aly, S. A. S. (2023). Firm characteristics and forward-looking disclosure: the moderating role of gender diversity. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 13(5), 947–973. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAEE-04-2022-0115

- Acquah, I. S. K., Agyabeng-Mensah, Y., & Afum, E. (2021). Examining the link among green human resource management practices, green supply chain management practices and performance. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 28(1), 267–290. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-05-2020-0205

- Adhikari, A., Biswas, I., & Avittathur, B. (2019). Green retailing: A new paradigm in supply chain management. In Management Association, I. R. (Ed.), Green business: Concepts, methodologies, tools, and applications (pp. 1489–1508). IGI Global, Hershey.

- Agyabeng-Mensah, Y., Esther Nana Konadu, A., & George Nana Arko, K. (2019). The mediating roles of supply chain quality integration and green logistics management between information technology and organisational performance. Journal of Supply Chain Management Systems, 8(4), 1–17.

- Agyabeng-Mensah, Y., & Tang, L. (2021). The relationship among green human capital, green logistics practices, green competitiveness, social performance and financial performance. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 32(7), 1377–1398. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMTM-11-2020-0441

- Ahmed, N. M. M. (2022). The moderating effect of environmental management accounting practices on the relationship between green supply chain management practices and corporate performance of Egyptian manufacturing firms. Scientific Journal for Financial and Commercial Studies and Researches (SJFCSR), 3(2), 475–507.

- Ahram, O. (2023). Egypt’s tourism revenues hit a record $13.6 bln in FY 2022/2023. Retrieved May 1, 2024, from https://english.ahram.org.eg/News/509648.aspx.

- Al-Khatib, A. W. (2022). Intellectual capital and innovation performance: the moderating role of big data analytics: evidence from the banking sector in Jordan. EuroMed Journal of Business, 17(3), 391–423. https://doi.org/10.1108/EMJB-10-2021-0154

- Al-Khatib, A. W., & Shuhaiber, A. (2022). Green intellectual capital and green supply chain performance: Does big data analytics capabilities matter? Sustainability, 14(16), 10054. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610054

- Alkhatib, A. W., & Valeri, M. (2024). Can intellectual capital promote the competitive advantage? Service innovation and big data analytics capabilities in a moderated mediation model. European Journal of Innovation Management, 27(1), 263–289. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-04-2022-0186

- Altig, D., Baker, S., Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N., Bunn, P., Chen, S., Davis, S. J., Leather, J., Meyer, B., Mihaylov, E., Mizen, P., Parker, N., Renault, T., Smietanka, P., & Thwaites, G. (2020). Economic uncertainty before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Public Economics, 191, 104274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104274

- Alves, H., Cepeda-Carrion, I., Ortega-Gutierrez, J., & Edvardsson, B. (2021). The role of intellectual capital in fostering SD-Orientation and firm performance. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 22(1), 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-11-2019-0262

- Amores-Salvadó, J., Cruz-González, J., Delgado-Verde, M., & González-Masip, J. (2021). Green technological distance and environmental strategies: the moderating role of green structural capital. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 22(5), 938–963. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-06-2020-0217

- Arjaliès, D.-L., & Mundy, J. (2013). The use of management control systems to manage CSR strategy: A levers of control perspective. Management Accounting Research, 24(4), 284–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2013.06.003

- Asiaei, K., Jusoh, R., & Bontis, N. (2018). Intellectual capital and performance measurement systems in Iran. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 19(2), 294–320. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-11-2016-0125

- Asiaei, K., Rezaee, Z., Bontis, N., Barani, O., & Sapiei, N. S. (2021). Knowledge assets, capabilities and performance measurement systems: a resource orchestration theory approach. Journal of Knowledge Management, 25(8), 1947–1976. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-09-2020-0721

- Atiku, S. O. (2019). Institutionalizing social responsibility through workplace green behavior. In S. O. Atiku (Ed.), Contemporary multicultural orientations and practices for global leadership (pp. 183–199). IGI Global.

- Avilés-González, J. F., Avilés-Sacoto, S. V., & Cárdenas-Barrón, L. E. (2017). An overview of tourism supply chains management and optimization models (TSCM – OM). In P. Vasant & K. M (Eds.), Handbook of research on holistic optimization techniques in the hospitality, tourism, and travel industry (pp. 227–250). IGI Global.

- Bag, S., & Gupta, S. (2020). Examining the effect of green human capital availability in adoption of reverse logistics and remanufacturing operations performance. International Journal of Manpower, 41(7), 1097–1117. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-07-2019-0349

- Bag, S., & Rahman, M. S. (2023). The role of capabilities in shaping sustainable supply chain flexibility and enhancing circular economy-target performance: an empirical study. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 28(1), 162–178. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-05-2021-0246

- Bansal, P., & Roth, K. (2000). Why companies go green: A model of ecological responsiveness. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 717–736. https://doi.org/10.5465/1556363

- Barão, A., & da Silva, A. R. (2014). How to value and monitor the relational capital of knowledge-intensive organizations. In M. M. Cruz-Cunha, F. Moreira, & J. Varajão (Eds.), Handbook of research on enterprise 2.0: Technological, social, and organizational dimensions (pp. 220–243). IGI Global.

- Barbery, D. C., & Torres, C. L. (2019). The importance of leadership, corporate climate, use of resources, and strategic planning in family business. In J. M. Saiz-Álvarez & J. M. Palma-Ruiz (Eds.), Handbook of research on entrepreneurial leadership and competitive strategy in family business (pp. 212–230). IGI Global.

- Barney, J. B., Ketchen, D. J., Wright, M., Hart, S. L., & Dowell, G. (2010). Invited editorial: A natural-resource-based view of the firm: Fifteen years after. Journal of Management, 37(5), 1464–1479. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310390219

- Benevene, P., Buonomo, I., Kong, E., Pansini, M., & Farnese, M. L. (2021). Management of green intellectual capital: Evidence-based literature review and future directions. In Sustainability, 13(15), 8349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158349

- Boiral, O., Brotherton, M.-C., Rivaud, L., & Guillaumie, L. (2021). Organizations’ Management of the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review of business articles. In Sustainability, 13(7), 3993. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073993

- Chen, Y.-S. (2008). The positive effect of green intellectual capital on competitive advantages of firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 77(3), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9349-1

- Chen, Y.-S., & Chang, C.-H. (2013). Utilize structural equation modeling (SEM) to explore the influence of corporate environmental ethics: the mediation effect of green human capital. Quality & Quantity, 47(1), 79–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-011-9504-3

- Chiappetta Jabbour, C. J., Sarkis, J., Lopes de Sousa Jabbour, A. B., Scott Renwick, D. W., Singh, S. K., Grebinevych, O., Kruglianskas, I., & Filho, M. G. (2019). Who is in charge? A review and a research agenda on the ‘human side’ of the circular economy. Journal of Cleaner Production, 222, 793–801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.03.038

- Chu, P. Y., Lin, Y. L., Hsiung, H. H., & Liu, T. Y. (2006). Intellectual capital: An empirical study of ITRI. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 73(7), 886–902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2005.11.001

- Chu, Z., Xu, J., Lai, F., & Collins, B. J. (2018). Institutional theory and environmental pressures: The moderating effect of market uncertainty on innovation and firm performance. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 65(3), 392–403. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2018.2794453

- Chu, S. H., Yang, H., Lee, M., & Park, S. (2017). The impact of institutional pressures on green supply chain management and firm performance: Top management roles and social capital. Sustainability, 9(5), 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9050764

- Curado, C. (2008). Perceptions of knowledge management and intellectual capital in the banking industry. Journal of Knowledge Management, 12(3), 141–155. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270810875921

- Daddi, T., Heras-Saizarbitoria, I., Marrucci, L., Rizzi, F., & Testa, F. (2021). The effects of green supply chain management capability on the internalisation of environmental management systems and organisation performance. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(4), 1241–1253. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2144

- Dai, J., Xie, L., & Chu, Z. (2021). Developing sustainable supply chain management: The interplay of institutional pressures and sustainability capabilities. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 28, 254–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.04.017

- Dang, V. T., & Wang, J. (2022). Building competitive advantage for hospitality companies: The roles of green innovation strategic orientation and green intellectual capital. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 102, 103161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2022.103161

- de Grosbois, D. (2016). Corporate social responsibility reporting in the cruise tourism industry: a performance evaluation using a new institutional theory based model. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(2), 245–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1076827

- Delgado-Verde, M., Martín de Castro, G., Navas-López, J. E., & Amores-Salvadó, J. (2014). Vertical relationships, complementarity and product innovation: an intellectual capital-based view. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 12(2), 226–235. https://doi.org/10.1057/kmrp.2012.59

- Diab, A., Abdelazim, S. I., & Metwally, A. B. M. (2023). The impact of institutional ownership on the value relevance of accounting information: evidence from Egypt. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 21(3), 509–525. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRA-05-2021-0130

- Diab, A., & Metwally, A. B. M. (2020). Institutional complexity and CSR practices: evidence from a developing country. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 10(4), 655–680. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAEE-11-2019-0214

- Diab, A. A. A., & Mohamed Metwally, A. B. (2019). Institutional ambidexterity and management control. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 16(3), 373–402. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRAM-08-2017-0081

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

- Do, A., Nguyen, Q., Nguyen, D., Le, Q., & Trinh, D. (2020). Green supply chain management practices and destination image: Evidence from Vietnam tourism industry. Uncertain Supply Chain Management, 8(2), 371–378. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.uscm.2019.11.003

- Donthu, N., & Gustafsson, A. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on business and research. Journal of Business Research, 117, 284–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.008

- Dost, M., Badir, Y. F., Ali, Z., & Tariq, A. (2016). The impact of intellectual capital on innovation generation and adoption. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 17(4), 675–695. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-04-2016-0047

- El-Masry, E. A., El-Sayed, M. K., Awad, M. A., El-Sammak, A. A., & Sabarouti, M. A. E. (2022). Vulnerability of tourism to climate change on the Mediterranean coastal area of El Hammam–EL Alamein, Egypt. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 24(1), 1145–1165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01488-9

- Elnagar, A., & Derbali, A. M. S. (2020). The importance of tourism contributions in Egyptian economy. International Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Studies, 1(1), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.31559/IJHTS2020.1.1.5

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and Statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150980

- Frare, A. B., & Beuren, I. M. (2022). The role of green process innovation translating green entrepreneurial orientation and proactive sustainability strategy into environmental performance. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 29(5), 789–806. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-10-2021-0402

- Ganbold, O., Matsui, Y., & Rotaru, K. (2021). Effect of information technology-enabled supply chain integration on firm’s operational performance. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 34(3), 948–989. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-10-2019-0332

- Geng, R., Mansouri, S. A., & Aktas, E. (2017). The relationship between green supply chain management and performance: A meta-analysis of empirical evidences in Asian emerging economies. International Journal of Production Economics, 183, 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2016.10.008

- Gregurec, I., Tomičić Furjan, M., & Tomičić-Pupek, K. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on sustainable business models in SMEs. In Sustainability, 13(3), 1098. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031098

- Gualandris, J., & Kalchschmidt, M. (2014). Customer pressure and innovativeness: Their role in sustainable supply chain management. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 20(2), 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2014.03.001

- Hair, J., Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage publications.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hall, J. (2000). Environmental supply chain dynamics. Journal of Cleaner Production, 8(6), 455–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-6526(00)00013-5

- Hanim Mohamad Zailani, S., Eltayeb, T. K., Hsu, C. C., & Choon Tan, K. (2012). The impact of external institutional drivers and internal strategy on environmental performance. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 32(6), 721–745. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443571211230943

- Hart, S. L. (1995). A natural-resource-based view of the firm. The Academy of Management Review, 20(4), 986–1014. https://doi.org/10.2307/258963

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In R. R. Sinkovics & P. N. Ghauri (Eds.), New challenges to international marketing (pp. 277–319). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Hohenstein, N.-O. (2022). Supply chain risk management in the COVID-19 pandemic: strategies and empirical lessons for improving global logistics service providers’ performance. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 33(4), 1336–1365. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-02-2021-0109