Abstract

Classical gardens in Suzhou were designed not only as an art of work but also for use in daily life. This study explored the tourist experience in the Net Master’s Garden in Suzhou, China, as a restorative environment based on attention restoration theory. Analysis of the results of the on-site questionnaire survey revealed three dimensions of perceived restorative characteristics: “fascination-compatibility”, “being away” and “extent”. Using multiple correspondence analysis, we also found three types of restorative experiences influenced by different activities and landscape impressions: a salient sightseeing experience, an immersive experience and a low restorative experience. In a salient sightseeing experience, when strolling visitors enjoyed the varying picturesque views, they perceived “fascination-compatibility” and “being away” more strongly. In an immersive experience, the visitors tended to do leisure activities, acquired a holistic sense of the garden, and perceived “extent” and “fascination-compatibility” more strongly. Visitors who acted more passively tended to perceive a low restorative experience. We think this study provides clues to expanding the meaning of garden visits from “appreciation” to “restoration” for both garden management and garden visitors. The classical garden might play a more important role in pleasure-derived leisure experiences in local areas, especially during times of the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. Introduction

Spending time in nature permits individuals to recover from mental fatigue (Kaplan & Kaplan, Citation1989; Ulrich et al., Citation1991; Ulrich, Citation1983). Gardens tend to provide a chance to experience nature as a nearby environment. Various studies have also suggested that gardens are a highly restorative environment (Cervinka et al., Citation2016; Elsadek et al., Citation2019; Kaplan & Kaplan, Citation1989; Lotfi et al., Citation2020; Tarek, Citation2021; Young et al., Citation2020). The restorative potential of historical gardens, however, has not received sufficient attention in prior research. Perhaps this is because the garden, both as a work of art and as a space for human activities, tended to be regarded as a paradox in discussions of garden design (Helmreich, Citation2008). Some studies suggest that the design of some historical gardens might be in accordance with the essence of contemporary landscape architecture as a space for rest, such as Daimyo’s gardens in Japan built in the Edo period (Shirahata, Citation1997; W. Li, Citation2010). How can historical gardens support the positive experience of restoration in the urban environment? This study intends to apply the theory of the restorative environment to explore the actual experience in the Net Master’s Garden in Suzhou, China, as a case study from the perspective of tourists.

Widely regarded as the best amongst present day Chinese gardens (Chen, Citation2018, p. 18), the classical gardens of Suzhou were “a landscape which was purely a work of art” (Copplestone, Citation1971, p. 108). Most of the gardens in Suzhou were private enclosures associated with houses in the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) or Qing Dynasty (1636–1912). As a part of the residence, the gardens were the locale for various recreation activities, such as parties, reading, and outdoor recreation in daily life (J. Sun, Citation2008). As a quiet and beautiful place for seclusion, a place for leisurely enjoyment, and sometimes as a festive space open to commoners, the gardens were not only a work of art to be appreciated, but also intended for functional daily use. The gardens’ characteristic open space within the urban space of Suzhou were mentioned in some historical studies of urban design in Suzhou (Xu, Citation2000). Now most of these gardens are open to the public and preserved as historical heritage sites. Beyond their function as a tourist attraction, the gardens can be seen as a place of recreation and cultivation (Chen, Citation2018, p. 71; Liu, Citation2005, p. 13), which is more accessible for local residents (J. Sun, Citation2009).

Attention restoration theory (ART) is a key part of Kaplan’s restorative environment theory. Kaplan called the environment in which people can recover from directed attention fatigue a restorative environment (Kaplan & Kaplan, Citation1989; Kaplan, Citation1995). Kaplan pointed out that four qualities characterizing person—environment exchange are important to a restorative experience. First, the person has a sense of being away geographically or psychologically. Second, the person’s attention is engaged effortlessly by some interesting or charming aspects of the environment, which is called “soft fascination”. The third quality is a sense of extent, which is defined by connectedness and scope. Compatibility is the fit between individual inclinations, actions and the environment. Some studies about gardens that used ART suggested that not only would the physical setting affect the level of the four restorative characteristics (Ivarsson & Hagerhall, Citation2008), an intensive positive relationship between the user and the garden is also important to make full use of a garden’s restorative potential (Cervinka et al., Citation2016). Restoration can be considered “the result of a complex place experience, in which cognitive, affective, social and behavioural components are considered together with the physical aspects of the environment” (Scopelliti & Giuliani, Citation2005).

Aesthetic preference is central to a landscape observer’s thoughts, conscious experience and behaviour (Ulrich, Citation1986), and the aesthetically pleasing features of the environment can support a restorative experience (Kaplan & Kaplan, Citation1989; Kirillova & Lehto, Citation2016). Subjects psychologically and physiologically change through activities, and the subject’s activities are one of the factors that form the image of the landscape (Yashiro, Citation1992). Behaviour and an aesthetic response to the scene is both somewhat independent and a connected phenomenon that is important for understanding the interaction with the environment (Ulrich, Citation1986).

In this study, we obtained more insight into how visitors behaved, what kind of scenery impressed the visitor more, and how this is related to their feelings to identify more details about the kind of restorative experience a visitor might obtain in the garden.

2. Study site

The Master of Nets Garden, as the case study of this paper, is located in one of the residential districts in the old city centre. It was first built during the Song Dynasty (960–1279) but was abandoned later. During the reign of the Qing Dynasty in the 1700s, Song Zongyuan, a retired government official, bought the property and remodelled the garden. It was restored in 1958 and opened to the public and has been preserved as a world cultural heritage site since 1999. The Master of Nets Garden covers 5400 sq. metres. The much smaller “Garden of the Master of Nets” is famous for its elegance and regarded as representative of medium-sized classical gardens (Liu, Citation2005, p. 65). The garden is divided into three parts: the eastern residential area, the central landscape and three landscape courts located in the north, northwest and south of the garden. A visitor can make a tour of the pond in the central landscape (Figure ) or wander into the quiet courts (Figure ). The integration of architecture with nature was one of the achievements of the Chinese classical garden (Copplestone, Citation1971, p. 108), and in the garden, there are many buildings in which one might love to sit and linger a while. One can stand by the balustrade or be seated in the pavilion by the pond and linger in a veranda in the court to appreciate the scenery outside through a window.

3. Data collection and analytical procedure

A survey was conducted from 30 October 2021, to 14 November 2021 (approximately 13:00 to 17:00). The questionnaires were distributed at the exit of the Master of Nets Garden or the rest area, and supplementary explanations were provided for question items that tourists did not understand. A total of 270 questionnaires were distributed in this survey. After review, the disqualified questionnaires were eliminated, and 260 valid questionnaires were obtained, for an effective rate of 96.3%. SPSS 26.0 software was used to input the sample data and obtain descriptive statistics on the demographic characteristics to further understand the basic situation of the samples.

The questionnaire was concerned with respondents’ restorative experience in the Master of Nets Garden and consisted of five parts, worded in Mandarin Chinese. The first part contained basic background information about the tourist and their behavioural characteristics; the former included gender, age, educational background, occupation and monthly income, while the latter included the number of visits to the Master of Nets Garden and the estimated length of visit.

The second part of the questionnaire set out possible frequent behaviours in the garden and asked participants to indicate to what extent these activities formed the focus of their restorative experience using a 5-point rating scale (1 = did not do this; 5 = the main activity).

The third part of the questionnaire asked participants to assess which landscape elements of the garden were attractive, all based on a five-point Likert scale (1 = very unattractive; 5 =very attractive). This part included not only rockery, flowers, trees, pools, other garden landscape elements and the scenery composed of these elements but also natural conditions such as blue sky and white clouds, swaying branches and cool autumn wind. In this part we also showed some photos to the respondents to help them understand the scenery described in the questionnaire.

Based on earlier research related to ART theory, the fourth part of the questionnaire used a scale intended to collect data on four factors, compatibility, extent, being away and fascination, that were considered to be related to garden visits. The questions were taken from Lehto’s (Citation2013) Perceived Destination Restorative Qualities scale to assess the perceived component in the fourth part of the questionnaire. The response continuum consisted of a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly oppose) to 5 (strongly agree).

4. Results

4.1. Sample profile

Male and female respondents accounted for 41.9% and 58.1%, respectively. Approximately one-third were between the ages of 18–25 years (36.2%), and approximately one-third were between 26–35 years (35.0%). The remainder of respondents were largely from 34–35 years old (16.5) or 46–60 years old (8.5%). With respect to participants’ residence, as the survey was conducted in the COVID-19 pandemic, 185 respondents (71.1%) lived locally in Suzhou. Forty-seven respondents (18.1%) came from an area adjacent to Suzhou (Shanghai and Jiangsu Province), and 28 respondents (10.8%) came from different regions in the country. A total of 152 (58.5%) respondents were visiting the Master of Nets Garden for the first time. Nearly 50% of the respondents were revisiting the garden. Most respondents stayed for less than two hours, accounting for 86.2% of the total number of respondents.

4.2. The reliability and validity of the variables

Exploratory factor analysis was performed to verify the consistency of items related to visitor behaviour, impressions of the scenery and the perceived restorative nature of the garden. Based on principal component analysis, the Kaiser normalized maximum variance method was adopted for rotation. Items with factor loadings higher than 0.5 were retained from this analytical procedure and subjected to another round of exploratory factor analysis. The factors with eigenvalues over 1 were obtained, and the results of the factorial analysis of variables and Cronbach’s alpha test are presented in Tables .

Table 1. Rotated tourist behaviour component matrix

Table 2. Rotated tourist impressions of scenery component matrix

Table 3. Rotated tourists’ perception of restoration component matrix

Two factors were extracted from 6 items measuring tourist behaviour and explained 59.546% of the total variance. Factor 1 (31.495% total variance) is determined by the items “sitting to have a rest”, “appreciating the scenery”, and “walking around”, and we named it “activities related to appreciation”. Factor 2 was responsible for 28.052% of the total variance, including “reading or meditation”, “paying attention to the interpretation to understand garden history and culture” and “taking photographs or painting”, and we called it “leisure activities” (Table ). The two factors each have a Cronbach’s alpha over 0.6, and we assumed that the assessment scale’s internal consistency is acceptable.

The attractive scenery in the garden was categorized into three groups: the scenery in the central landscape section, the scenery of the courtyard and the natural conditions. The three factors explained approximately 63.308% of the variance and were labelled “centre section scenery”, “courtyard scenery” and “natural conditions” (Table ). Cronbach’s alpha for each factor is over 0.8, indicating that the items are highly correlated.

A total of 3 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were extracted from the 16 items of the tourist restorative experience perception scale, and the total variance explained was 66.572%, which was greater than 50% (Table ). Instead of the four-dimensional structure proposed in the earlier research of Harting et al. (Citation1997), the perceived restorative characteristics of the garden in this research appear to encompass three separate components. Fascination and compatibility were perceived as one factor, and we named it “fascination-compatibility”. The other two factors were labelled after the components in the earlier study as “being away” and “extent”.

4.3. The results of cluster analyses

The cluster algorithm was applied to the factor score obtained previously through the factorial analysis. The following is the final cluster centre output for K-means analysis. The final cluster centres reflect the characteristics of the typical case for each cluster.

The respondents were grouped into 3 clusters with different behavioural characteristics, using the factor scores for “activities related to appreciation” and “leisure activities” (Table ). Cluster 1 included 70 (26.9%) participants who scored high on both factors, with higher mean scores on the dimension of “leisure activities”. The respondents in this group not only enjoyed the scenery but were also more willing to carry out leisure activities and were named “explorers”. The respondents in cluster 2 included 84/260 (32.3%) participants and scored low in both dimensions. The group was named the “wanderers”, and their behaviour characteristics are reflected as aimless. Cluster 3 was the largest segment, with 106 (40.8%) participants, and displayed the highest mean for the factor “activities related to appreciation”. We called the respondents in this group “appreciators”.

Table 4. Tourists’ behaviour clusters (n = 260)

The respondents were categorized into four groups using the factor scores for “centre section scenery”, “courtyard scenery” and “natural conditions” (Table ). The tourists in cluster 1 who were more impressed by the natural conditions can be called the “nature lovers”. Cluster 2 presented low values in all three factors and was labelled the “disinterested”. Cluster 3 presents a high mean for the factor “centre section scenery” and a negative mean for “courtyard scenery” and “natural conditions”, and this group labelled “the lake lovers” was identified as tourists who were impressed by the centre section scenery. Cluster 4 presents a high mean in all three factors, with the highest scores for “courtyard scenery”. The tourists in this cluster had a complete image of the garden, and were labelled “the garden lovers”.

Table 5. Clusters of tourists impressed with the scenery (n = 260)

The factors of the perceived restorative characteristics were grouped into 4 clusters by their factor scores (Table ). Respondents in cluster 1 tended to have a strong feeling of “fascination-compatibility” and “being away”, with higher scores in “fascination-compatibility”, and we called them “mesmerized”. The respondents in cluster 2 tended to have a strong feeling of “being away” and were labelled “escapists”. Respondents in cluster 3 tended to have a strong feeling of “extent” and “fascination-compatibility”, with higher scores for the factor of “extent” and negative scores for “being away”, and we called them “enjoyers”. Visitors in cluster 4 have low values in all three components of the restorative environment. We called the respondents in cluster 4 the “distracted”.

Table 6. Clusters of tourist perception of restoration (n = 260)

4.4. The nexus between tourists’ behaviour, impression of the scenery, and perception of the restorative environment

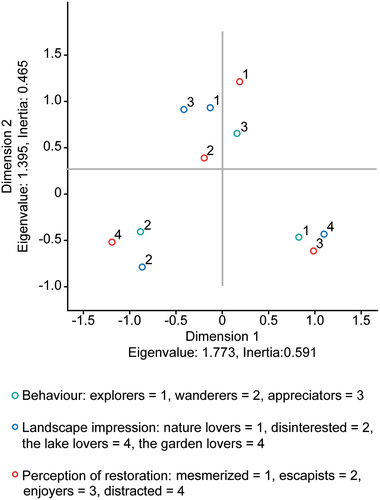

The three kinds of classifications obtained from the above cluster analysis were saved as categorical variables of tourist behaviour, landscape impression and perception of restorative environment (Behaviour: explorers = 1, wanderers = 2, appreciators = 3; landscape impression: nature lovers = 1, disinterested = 2, the lake lovers = 3, the garden lovers = 4; perception of restoration: mesmerized = 1, escapists = 2, enjoyers = 3, distracted = 4). Below is a multiple correspondence analysis for the purpose of studying the relationships between the three variables. After 23 iterations of the model, the comprehensive dimension is finally obtained, as shown in the table. Among the three variables, the proportion of interpretation provided by dimension 1 is 59.109% and that of dimension 2 is 46.498%. Dimension 1 and dimension 2 explain an average of 52.803% of the total information associated with the qualitative variables studied.

The information related to the respondents was grouped around two axes. According to the principles of correspondence analysis, different types of the same variable are similar when they are located in the same quadrant and close to each other. There is a correlation between different variables close to each other. Therefore, the tourists who were classified by behaviour as “appreciators”, who tend to enjoy the natural conditions as “nature lovers” or be impressed by the varied scenery in the centre section as “the lake lovers”, and the tourists who were classified as either “mesmerized” or “escapists” are combined into a group. In quadrant four, the second group of respondents are characterized by a tendency toward garden-based activities as “explorers”, having a whole image of the garden as “the garden lovers”, and having a strong feeling of “extent” and “fascination-compatibility” as “enjoyers”. The third group of tourists in quadrant three is formed by respondents who have an aimless behaviour pattern, who paid low attention to the scenery, and who have a low perception of restorative characteristics. These results are presented in Figure .

5. Discussion

This study identified the perceived restorative characteristics of the classical garden, and to understand the restorative experience in different situations, this study applied correspondence analysis to reveal the relationship between tourists’ behaviour patterns and general types associated with impressions of the landscape and perceptions of restorative characteristics.

5.1. Perceptions of the restorative characteristics of the garden

The research suggests that as a restorative environment, the characteristics of the garden can be perceived by three independent dimensions.

Two of the characteristics perceived from the restorative experience described in ART—fascination and compatibility—were grouped into one dimension in this research. Fascination is the central component of a restorative environment, refers to a related extended sequence of fascinating elements and attracts people effortlessly. Compatibility refers to resonance or alignment between the individual’s needs and what the environment offers (Kaplan & Kaplan, Citation1989). According to the findings of this research, fascination and compatibility were understood in terms of one interlinked aspect. Kaplan mentioned, “When the fascinating stimulus fit one’s purpose, it would be felt both fascinating and compatible” (Kaplan, Citation1995). We think this kind of perceived characteristic of “being both fascinating and compatible” in the garden might be related to a salient feature of Chinese garden design, which is to create “harmony” between nature and human occupants. The ideology of traditional Taoism maintains that “nature and man are one”, reflecting the idea that nature is harmonious and that man belongs to nature. Influenced by this ideology, all cultural artists after Tao Yuanming of the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317–420) emphasized the harmonious rhythm of the universe as the highest state of artistic creation, and the basic determination of whether a creation counts as art was summarized in the ability to express the realm of “heaven and humans” (Wang, Citation1990, p.301,p.444). In practice, to create this “artistic conception”, the designer should not only be good at creating the scene but also emphasize aspects of the garden composition that make the human figure blend well into the scenery (Chen, Citation1984, p. 25), so that humans were “in the wildest of the landscape paintings” but not outside of the picture. The aesthetic not only attracted people to splendid landscape drawings but also induced feelings of connection between the individual personality and the landscape in nature (X. Sun, Citation2013). That idea is reflected in the questionnaire items “I found the destination fascinating” and “this kind of place fit me well”. We speculated that the visitor might also achieve resonance with the artistic conception of “landscape and man as one”, which is embodied in the physical object on display and has a sense of fascination and compatibility integrated together.

Being away is another perceived characteristic of the garden as a restorative environment. The away dimension can be understood in terms of two aspects. The first aspect is to be away physically, such as “be very different from my daily environment”. The garden was not designed as a green space in the city but refers instead to the “small world” that is independent, self-contained and pure, creating a unique character (Y. Li, Citation2005, p. 305). As a distinctive space in the urban environment, even for the tourists from Suzhou, the garden environment is not merely a nearby place but a different setting than the usual urban environment. Another aspect is to be away mentally, such as “I could forget about my obligations” and “I felt free from all the things that I normally have to do”. Notably, a philosophy and practice around the identity of a recluse had been developed since the Wei—Jin Southern and Northern Dynasties (220–589), and played a role in the development of the literati gardens (Wang, Citation1990, pp. 203–215). Gardens in China implied an escape from reality and a life in seclusion and symbolized escape and freedom (Zhang, Citation2021). We speculated that this cultural meaning would contribute to the sense of escapism.

The third factor is extent. Making a limited space produce feelings of infiniteness is a long-standing basic principle of the garden layout. The technique of “exposing” and “hiding” in space is often used to give a sense of scope as well as connectedness and the perceived elements of the environment as seen as a portion of some larger whole (Peng, Citation1986, p. 24). Extent can also be experienced in conceptual domains, such as in images (Harting et al., Citation1997). In gardens, the names of scenic spots and calligraphic landscapes can also inspire the imagination (Cheng & Peng, Citation2022; Peng, Citation1986, p. 11),such as “月到风来(the Moon Come with Breeze)”is reminiscent of the moonlight in autumn. The sense of extent can qualify the garden as an environment, so that it is more than merely an unrelated collection of impressions; the garden provides enough to see, experience, and think about (Kaplan, Citation1995), such as “doing varied things in the garden” and “exploring extensively in the garden”.

In general, the artistic conception and the salience of the garden as a historical and cultural location contribute to the three factors of the perceived restorative characteristics. The insight that a garden is a work of art and a restorative environment to experience would not be a paradox for a garden visit.

5.2. Perceived restorative characteristics in different situations

The four different components in ART theory would likely be of different strengths as predictors of restoration in different situations (Ivarsson & Hagerhall, Citation2008). One approach to this issue is to consider what activities and visual impressions are particularly likely to enhance each of the three characteristics of a restorative environment. This helped us understand the type of restorative experience that different activities and visual impressions are most likely to elicit.

The Chinese garden was designed not only like a framed picture for appreciation from a fixed angle but also to “re-create the experience of a wandering or rambling in a vaster landscape” (Copplestone, Citation1971, p. 108). We speculated that the respondents in the first quadrant had this kind of experience. In this situation, the picturesque view keeps varying, while the visitor wanders or rambles in the garden, and they are impressed by nature or the scenery around the pond that imitates a lake and perceive the harmony of nature (Su et al., Citation2022). The respondents who pursued pleasure stimulated by the scenery felt both fascination and compatibility, and they had a stronger sense of “being away” from the “vaster landscape”, which is quite different from the surrounding urban environment. We determined respondents in the first quadrant had a salient sightseeing experience.

The respondents in the second quadrant were more likely to do leisure activities and appeared to be not only interested in the scenery in the centre section but also impressed by the courtyard scenery resulting in a strong sense of “extent”. Kaplan said, “To achieve the feeling of extent, it is necessary to have interrelatedness of the immediately perceived elements, so that they constitute a portion of some larger whole” (Kaplan & Kaplan, Citation1989, p. 182). In this situation, the courtyard landscape might strengthen the sense of interrelatedness of the scenery in view. By reading, taking photos and exploring the history, they spend more time enjoying the general environment of the garden. We speculated that through these activities, the respondents have more chances to think or experience in the garden. The respondents in quadrant 2 might be more “engaged mentally”, rather than impressed by the visual landscape, and had an immersive experience in the garden.

The respondents in the third quadrant seemed to have an experience with low restorative characteristics. If the respondents acted aimless and did not have a deep impression of the landscape, they seemed to have a lower perception of the restorative characteristics. The classical garden became a tourist destination in the 1950s and was affected by preservation as cultural heritage site. It is popularly held that “the gardens south of the Yangtze are the best in China, and the gardens of Suzhou are the best of the area south of the Yangtze”. In a process of developing as tourist sites, the Suzhou classical garden was identified as a symbol of Suzhou and was encoded as a consumer object for tourists. Culler believes that tourists are engaged in semiotic projects, and they expect interesting things to happen to them (Culler, Citation1981). We speculate that when the gardens were consumed as a sign system, visitors tended to behave passively, and the garden visitor experience appropriate to tourism might be perceived as less restorative.

6. Conclusion and implication

This research provides an approach for identifying the characteristics of the classical garden as a location that interacts with people by using attention restoration theory. In this research, we found that the perceived restorative characteristics of the garden can be understood from three dimensions: “fascination-compatibility”, “being away” and “extent”. Furthermore, using multiple correspondence analysis, we found three types of restorative experiences that different activities and visual impressions are most likely to elicit: a salient sightseeing experience, an immersive experience and a low restorative experience. In a salient sightseeing experience, while the visitor wandered in the garden and enjoyed the varying picturesque views while walking, they perceived “fascination-compatibility” and “being away” more strongly. In an immersive experience, the visitors tended to engage in leisure activities in the garden, acquired a whole image that did not immediately meet the eye, and perceived a sense of “extent” and “fascination-compatibility” more strongly. Visitors with low perceived restorative characteristics tended to be more passive in doing something or enjoying the scenery.

We hope that these findings might be of relevance for both garden management and garden visitors seeking a restorative experience. This research provided an approach for garden management to understand what kind of garden experience would be had from the perspective of visitors and provided clues for promoting the garden as a place for restoration. We speculated that the activities and impressions of the landscape seemed to be triggers of the three different components of the restorative characteristics the visitors felt. It seems that the pleasure associated with the garden experience will be multiplied for certain visitors. The restorative experience was seen as a basis for the person’s liking for and attachment to the place (Hartig & Staats, Citation2003). Previous research has shown there is a positive relationship between place attachment and pro-environmental behaviours (Ramkissoon et al., Citation2013). In addition to the maintenance of the landscape, enriching the garden visit experience with leisure activities also seems important for active management. It might engage the visitor to enjoy their time in the garden more rather than appreciate the garden only as a work of art, and a more positive attitude towards the garden can be expected.

From a visitor angle, this research suggested that a visitor who intends to get away from their daily hassles might choose to visit the garden. As an appreciator or user, even if visitors are not proficient in garden art, they might be motivated to visit by the expectation of mental restoration and establish a positive affective bond with the garden. COVID-19 is leading us to re-consider our existing behaviors to promote healthier lifestyle (Ramkissoon, Citation2020). More visitors of the classical gardens open to the public came from local areas during the COVID-19 pandemic. Tourists’ perception determine the decision making of health and wellness tourism consumption (Majeed & Ramkissoon, Citation2020). Not only being a heritage tourism resource but also a health and wellness tourism destination, the garden is of escalating importance in the city environment and might play a more important role in pleasure-derived leisure experiences.

7. Geolocation information

Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, China

Acknowledgments

We thank all the visitors for patiently answering the questionnaire and the staff of the Net Master’s Garden for their assistance during the survey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jianbing Sun

Jianbing Sun Her research interests include landscape architecture and heritage tourism.

Xiaoli Cheng

Xiaoli Cheng Her research interests include environmental psychology and heritage tourism.

Changhong Zhao

Changhong Zhao Her research interests include Japanese culture and comparative culture study.

References

- Cervinka, R., Schwab, M., Schönbauer, R., Hämmerle, I., Pirgie, L., & Sudkamp, J. (2016). My garden – my mate? Perceived restorativeness of private gardens and its predictors. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 16, 182–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2016.01.013

- Chen, C. (1984). Shuo Yuan. On Chinese gardens. Tongji University Press.

- Chen, C. (2018). Suzhou gardens. Tongji University Press.

- Cheng, D., & Peng, M. (2022). Research on the formation of poetic conception of small hill and osmanthus fragrans pavilion in the Master-of-Nets Garden. Art and Performance Letters, 3(1), 84–90. https://doi.org/10.23977/artpl.2022.030118

- Copplestone, T. (1971). World architecture: An illustrated history. Paul Hamlyn Ltd.

- Culler, J. (1981). Semiotics of tourism. The American Journal of Semiotics, 1(1), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.5840/ajs198111/25

- Elsadek, M., Sun, M., Sugiyama, R., & Fujii, E. (2019). Cross-cultural comparison of physiological and psychological responses to different garden styles. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 38, 74–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2018.11.007

- Hartig, T., & Staats, H. (2003). Guest editors’ introduction: Restorative environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 23(2), 103–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(02)00108-1

- Harting, T., Korpela, K., Evans, G. W., & Garling, T. (1997). A measure of restorative quality in environments. Scandinavian Housing&planning Research, 14(4), 175–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/02815739708730435

- Helmreich, A. (2008). Body and soul: The conundrum of the aesthetic garden. Garden History, 36(2), 273–288.

- Ivarsson, C. T., & Hagerhall, C. M. (2008). The perceived restorativeness of gardens – assessing the restorativeness of a mixed built and natural scene type. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 7(2), 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2008.01.001

- Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(3), 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2

- Kaplan, S., & Kaplan, R. (1989). The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. Cambridge University Press.

- Kirillova, K., & Lehto, X. (2016). Aesthetic and restorative qualities of vacation destinations: How are they related? Tourism Analysis, 21(5), 513–527. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354216X14653218477651

- Lehto, X. Y. (2013). Assessing the perceived restorative qualities of vacation destinations. Journal of Travel Research, 52(3), 325–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287512461567

- Li, W. (2010). A research on an act of viewing in Saien Garen of the Kii Glan. Landscape Research Japan, 73(5), 363–366. https://doi.org/10.5632/jila.73.363

- Li, Y. (2005). Cathay’s idea-design theory of Chinese classical architecture. Tianjin University Press.

- Liu, D. (2005). Classical gardens of Suzhou. China Architecture & Building Press.

- Lotfi, Y. A., Refaat, M., El Attar, M., & Salam, A. A. (2020). Vertical gardens as a restorative tool in urban spaces of New Cairo. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 11(3), 839–848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2019.12.004

- Majeed, S., & Ramkissoon, H. (2020). Health, wellness, and place attachment during and post health pandemics. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 573220. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.573220

- Peng, Y. (1986). Analysis of the traditional Chinese garden. China Architecture & Building Press.

- Ramkissoon, H. (2020). COVID-19 place confinement, pro-social, pro-environmental behaviors, and residents’ wellbeing: A new conceptual framework. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2248. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02248

- Ramkissoon, H., Smith, L. D. G., & Weiler, B. (2013). Testing the dimensionality of place attachment and its relationships with place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviours: A structural equation modelling approach. Tourism Management, 36, 552–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.09.003

- Scopelliti, M., & Giuliani, M. V. (2005). Choosing restorative environments across the lifespan: A matter of place experience. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 24(4), 423–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2004.11.002

- Shirahata, Y. (1997). 大名庭園 (Diaimyo’s garden). Kodansha.

- Sun, J. (2008). A historical study on the characteristics of the Chinese private garden used in daily life during the Qing period. Landscape Research Japan Online, 1, 28–33. https://doi.org/10.5632/jilaonline.1.28

- Sun, J. (2009). Evaluation for the classical garden of Suzhou as an open space in the district using the contingent valuation method. Urban Studies, 16(8), 64–68.

- Sun, X. (2013). Life conception, picturesque conception, artistic conception, on the artistic stages and expressions of literati’s enjoyable landscape gardens. Landscape Architecture, 107(06), 26–33. https://doi.org/10.14085/j.fjyl.2013.06.014

- Su, X., Wang, C., Zhou, X., & Qin, R. (2022). Research on the healthy thoughts of Chinese literati garden: Taking the Master-of-Nets Garden as an example. Journal of Human Settlements in West China, 37(5), 59–66. https://doi.org/10.13791/j.cnki.hsfwest.20220509

- Tarek, S. (2021). Enhancing biophilia as a restorative design Approach in Egyptian Gardens. Proceedings Artic. https://doi.org/10.38027/ICCAUA2021242N12

- Ulrich, R. S. (1983). Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. In I. Altman & J. F. Wohlwill (Eds.), Behavior and the natural environment (pp. 85–125). Springer US.

- Ulrich, R. S. (1986). Human responses to vegetarian and landscapes. Landscape & Urban Planning, 13, 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-2046(86)90005-8

- Ulrich, R. S., Simons, R., Losito, B. D., Fiorito, E., Miles, M. A., & Zelson, M. (1991). Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environment. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 11(3), 201–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80184-7

- Wang, Y. (1990). 园林与中国文化 (Gardens and Chinese culture). Shanghai People’s Publish House.

- Xu, Y. (2000). The Chinese city in space and time: The development of urban form in Suzhou. University of Hawaii Press.

- Yashiro, M. (1992). On systematic methods of landscape planning and design. Journal of the Japanese Institute of Landscape Architects, 56(2), 146–153.

- Young, C., Hofmann, M., Frey, D., Moretti, M., & Bauer, N. (2020). Psychological restoration in urban gardens related to garden type, biodiversity and garden-related stress. Landscape and Urban Planning, 198, 103777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103777

- Zhang, L. (2021). Comparative study of restorative environment theory and rehabilitation thoughts of Chinese Classical Garden. China Ancient City, 35(03), 46–51. https://doi.org/10.19924/j.cnki.1674-4144.2021.03.007