?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The objective of the study was to determine the size of Ghana’s “underground economy” and the extent of tax evasion in Ghana. The underground economy in most countries is vital because it serves as a survival place for most people. However, their activities are mostly related to tax evasion because their economic activities are mostly concealed from government tax authority agencies. The study used the Multiple Indicator Multiple Cause (MIMIC) model to estimate the size of Ghana’s “underground economy”. The data was obtained from the World Bank country indicators, Economic Freedom and Bank of Ghana and its spans from 1990 to 2020. The study is one of the premier to estimate the size of Ghana’s “underground economy” using the MIMIC model. The study found that the average size of Ghana’s underground economy is about 44% of the official GDP of the economy and is primarily caused by tax burden, government integrity, unemployment, government spending, self-employment, inflation and the agricultural sector employment. The estimated tax evasion due to the presence of the “underground economy” is, on average, about 6.28% of GDP. Other findings from the study were that, while tax evasion negatively affects economic growth, the underground economy’s size positively affects economic growth in Ghana. We recommend that since the underground economy, to some extent, provides job security to some individuals within the country, their activities must be formalized by ensuring proper documentation and registration. Furthermore, the government should improve the ways of detecting tax evasion through intensive tax audit.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Our paper explores the underground economy and tax evasion, two hidden facets of Ghana’s economy that directly affects its citizens and the health of the economy at large. By revealing how economic activities conducted at the blindsight of government officials affect tax revenues, public services, and overall economic growth, we aim to shed light on matters that affect the quality of life of Ghanaians. We hope that our findings will be of interest to everyone who is concerned about fairness, transparency, and national development. Our ultimate goal as we investigate these matters in Ghana, is to advance a fairer and more promising future for every Ghanaian. Our study is not just about the numbers but central to it, is the creation of a better tomorrow for everyone.

1. Introduction

A country’s economic growth is not achieved in isolation from economic policies. The government possesses several economic policies both at the micro and macro levels to achieve economic growth. However, knowing that these economic policies are as powerful and good as the data that underpins them is prudent. Unfortunately, many of these economic policies are unsuccessful simply because the official data from which these policies were formulated are misleading because of the “underground economy”. This is because when a significant portion of the underground economy exists, it may lead to incorrect economic statistics, which eventually undermines the effectiveness of implemented economic policy initiatives (Schneider & Enste, Citation2002). For instance, key policy variables such as consumption, unemployment, labor force participation, and income will all be inaccurate when a significant portion of economic activity is kept under wraps from government officials. Also, as the underground economy expands, resources cannot be distributed among the various economic sectors equitably and efficiently, which tends to impede economic growth. This according to Yasmin and Rauf (Citation2003) will further raise the tax burden on formal economy workers which may eventually reduce public tax revenues and GDP growth.

Although the underground economy can contribute to economic growth by providing employment opportunities and generating income for people who might otherwise be excluded from the formal economy, it can also have negative consequences, such as reducing tax revenue, distorting market competition, and promoting criminal activity. The underground economy and its activities account for a sizeable portion of the economy of Ghana. While there is limited official data on its size, various studies and reports provide empirical evidence of its existence and impact. Ghana’s underground economy primarily comprises the agricultural sector, the informal sector, which includes street vendors, small businesses, and artisans (Ocran, Citation2018). It also includes illegal trade activities, such as smuggling, counterfeiting, and even prostitution (Ocran, Citation2018). Many of these businesses operate without formal registration or licenses and may not comply with labor or tax regulations. Moreover, with the advancement of technology and mobile phone penetration in the country, the underground economy has grown significantly, leaving most of their activities undetected by government authorities.

Among the primary issues associated with the underground economy is tax evasion (Pyle, Citation1989). According to Akoto (Citation2020), most tax evaders in Ghana are within the underground economy. Tax evasion could be seen as using unethical methods to reduce or avoid one’s tax obligation to the government (Jones et al., Citation2010). Tax evasion suffocates economic growth and development and tends to interfere with the delivery of high-quality public goods. Tax evasion tends to affect revenue mobilization, eventually affecting the country’s economic performance (Mu et al., Citation2023). Domestic revenue mobilization is crucial for achieving the SDGs as it provides the financial resources needed for development. However, in the case of Ghana, the country does little when it comes to revenue mobilization. For instance, Ghana’s expenditure far exceeds its accumulated revenue, coupled with increasing domestic and external government debt since 2006 (Asiama et al., Citation2014). However, Ghana’s quick response has been to widen the tax net to increase domestic revenue mobilization. This is because taxes remain the most significant way for nations to mobilize revenue. The tax net can be broadened by introducing new taxes, increasing old taxes, or increasing the number of citizens and firms paying taxes. However, in the quest to improve the tax revenue, most governments tend to introduce new taxes, either direct or indirect, which worsens the situation as it further burdens the few tax-law-abiding citizens who pay their taxes. Also, governments are mindful that underground economic dealings and tax rate adjustments are linked to slower economic growth through increased tax evasion, higher revenue losses, and higher budget deficits (Fethi, Citation2004). Hence, the available option for the government in the quest to widen the tax net is to reduce the proportion of individuals and firms engaging in the hidden economy or evading taxes.

However, observing and investigating the underground economy and tax evasion is quite challenging because of how secretive they are. As a result, researchers have adopted various methods to predict its size and the level of tax evasion across multiple jurisdictions due to its presence. However, it is prudent to note that these various methods employed in determining the underground economy can significantly impact its size and other economic growth indicators (Schneider & Buehn, Citation2016). In Ghana, studies on the underground economy size and its related issue of tax evasion are limited to the works of Asante (Citation2012) and Amoh and Adafula (Citation2019). However, there are several significant ways in which this study is different from past ones in Ghana. First, the MIMIC model was employed in determining the extent of the “underground economy” and tax evasion in Ghana. In the works of Asante (Citation2012) and Amoh and Adafula (Citation2019), they employed the indirect method, especially the Currency Demand Approach (CDA) in determine the size of Ghana’s “underground economy” and the level of tax evasion. However, there are several drawbacks to the use of this method which are primarily based on its assumptions. Some studies, like Aigner et al. (Citation1988) and Kirchgässner (Citation2017), have argued that the CDA can produce wildly unlikely outcomes when used to calculate the magnitude of the “underground economy”. Thus, according to these studies, the CDA tends to underestimate the magnitude of the sector in question.

For instance, one core premise of the CDA is that those who hide their economic activities do so using cash in their transactions to avoid paying taxes on such transactions (Amoh & Adafula, Citation2019). But this assumption may not necessarily be valid since not all operations within the sector use physical currency as a means of exchange (Emerta, Citation2010). Thus, many informal economic activities may be conducted using non-cash methods, such as bartering or informal credit arrangements. Therefore, assuming that physical cash is the only legitimate method of conducting economic activity within the underground economy can eventually lead to an underestimation of its size. Moreover, the rise of electronic payments systems in Ghana such as the mobile money can make it difficult in determining the size of the “underground economy” using the CDA. This is because these payment methods are not tracked in the same way as cash transactions, making it harder to determine the level of economic activity in the underground economy. Therefore, this procedure can undervalue the size and impact of the “underground economy”.

Again, Asante (Citation2012) and Amoh and Adafula (Citation2019) assume that the size of Ghana’s “underground economy” is caused by the level of tax burden alone in their currency demand approach. The growth of the “underground economy”, however, can be strongly impacted by other variables, including the effectiveness of regulations, taxpayer sentiments about the government, tax morality, and corruption (Schneider & Buehn, Citation2016). Therefore, if these other variables are included in the underground economy estimation, the values might be higher than the values reported in the studies of Asante (Citation2012) and Amoh and Adafula (Citation2019).

The underground economy is a complicated and diverse phenomenon that includes not just currency transactions but also a wide range of other activities, whether legal or illegal, that are not fully covered by the CDA. The MIMIC approach in estimating the underground economy was proposed to resolve the weakness in the other methods, like the CDA. The fundamental hypothesis of the MIMIC model is that the underground sector can be viewed as an “unobservable variable” affected by several factors, such as tax burden, regulation quality, corruption, attitudes of taxpayers, and high transaction costs. The manifestation of the underground economy appears in various forms and simultaneously affects production, labor, and the money market. Therefore, describing or estimating it using just a single variable indicator and cause to capture this effect may lead to inconsistent results and estimates, but this has been the case with the CDA. For instance, in Ghana, the “underground economy” is characterized by a wide range of informal activities that are not entirely dependent on cash transactions (Ocran, Citation2018). Therefore, by employing the MIMIC model, this study seeks to provide detailed and comprehensive understanding into the landscape of the “underground economy”, this is due to the fact that the MIMIC model takes into considerations the simultaneous effect of several indicators and factors, like tax evasion, labor market informality, agricultural activities and unreported income, in its estimations.

Moreover, the MIMIC model was used in this study because the model when employed in studying the underground economy, will not only provide an estimation into its size, but also detects the various determinants and drivers of the underground economy (Nchor & Adamec, Citation2015). Unearthing the drivers and determinants of the “underground economy” in Ghana will help the government to know the specific variables to consider in the policy framework in quest to address the “underground economy” and tax compliance. Also, the MIMIC model is important because it provides a more precise assessment of the hidden economy than the other methods which mainly rely on a single indicator or source of data (Nchor & Adamec, Citation2015). By combining various indicators and causes, the model can provide a more accurate approximation of the size of the hidden sector than a single indicator could provide. The accurate estimation of the “underground economy” is vital for policymakers and researchers because it provides insight into the overall health of the economy and the potential for sustainable economic growth. Furthermore, an accurate estimate of the underground economy can help governments to design policies that encourage businesses and individuals to participate in the formal economy and to comply with tax and labor regulations.

Despite its importance in estimating the “underground economy”, the MIMIC model method has not been used thus far in developing countries because of the lack of data. Indeed, the applicability of the model approach is relatively restricted, even in cases where the data are accessible. A review of the literature reveals that the model approach in estimating the “underground economy” and tax gap may be the first of its kind in Ghana. Hence, it’s against this background that the study seeks to examine Ghana’s underground economy’s size and tax evasion to address economic growth.

2. Literature review

2.1. Conceptual review

The “underground economy” mostly consists of all economic activities that are not officially recorded or monitored by government authorities. This includes transactions that are conducted in cash or other non-traceable methods and can range from small-scale informal activities such as babysitting or gardening to large-scale criminal enterprises such as drug trafficking or smuggling. The “underground economy” is synonymously referred to as the informal, shadow, black, hidden, cash, or grey economy (Medina & Schneider, Citation2019). The underground economy is a complex phenomenon to study. This is because, in the quest to study the underground economy, researchers are often faced with how to conceptualize the underground economy. To others (Breusch, Citation2005; Draeseke & Giles, Citation2002; Mazhar & Méon, Citation2017; Schneider & Buehn, Citation2016), the existence of the underground economy cannot be observed, however, it manifests itself in several observable ways. The underground economy, in contrast, is defined by Feige (Citation1989) as any economic pursuits mostly carried out secretly or at the blindsight of government officials. Pyle (Citation1989) modify this definition by including the intention to engage in this economic activity. Thus, according to Pyle (Citation1989), it consists of those income-generated activities concealed at the blindsight of tax officials to evade paying taxes. According to Smith (Citation1997), “the underground economy consists of all market-based production of goods and services, whether legal or illegal, which escapes detection in the official estimates of GDP”. Therefore, this study operationalizes the “underground economy as the production of goods and services, whether legal or illegal, that escape the notices or regulations of authorities in an attempt to evade taxes”. This is because according to Tanzi (Citation1980:34) “taxes or restrictions alone are sufficient to bring about an underground economy”.

A serious problem that is closely tied to the operations of the “underground economy” is the level of tax evasion associated to the sector. As indicated earlier, tax evasion is the illegal means individuals or firms adopt to reduce their tax liability to the government (Jones et al., Citation2010). Therefore, the “underground economy” cannot be defined precisely in isolation from the concept of tax evasion. This is because the underground economy’s activities are primarily carried out to avoid paying different direct and indirect taxes that would otherwise be incurred if they were reported to the tax authorities. Therefore, it is appropriate to equate the “underground economy” with tax evasion (Pyle, Citation1989).

3. Issues of the underground economy

There are several issues associated with the underground economy, however, Pyle (Citation1989) argues that all these issues could be consolidated into four major issues; “size and measurement, participation, economic consequences, and policy implications”.

3.1. Size and measurement

The question of how vast the underground economy should be to warrant a safe economic atmosphere seems topical to most researchers in this field due to its implication for further analysis. This is because an ongoing argument suggests that there is an optimal level of informality that maximizes aggregate welfare, which will shrink over time due to the growth in the formal sector. Nevertheless, evidence suggests that after decades of focusing on the formal economy, the “underground economy”, instead of shrinking, is actually growing. Therefore, the question remains, what should be the actual size of the “underground economy”? In the quest to address this question has led to the development of various techniques and models on how to estimate the size of the “underground economy”. Direct, indirect, or model approaches are the three basic categories into which these techniques can be divided.

The direct approach is a microeconomic way of assessing the underground economy’s size. These methods are used to gain firsthand information regarding undeclared income from businesses and individuals involved in underground activities. The auditing of tax returns and administering questionnaires to people and businesses are the two approaches used in this approach (Orsi et al., Citation2012). The auditing approach uses the difference between income reported for tax reasons and that found through random checks to determine the extent of the “underground economy”. Whiles the survey method deals with administering questionnaires to households to know the income they earn as a result of the economic activities they engage in and what percentage of their income they submit to the tax authorities. Despite its advantage of providing in-depth information, studies like Schneider and Buehn (Citation2016), Fortin et al. (Citation2010), and Pyle (Citation1989) have all concluded that gathering such information from these individuals may be extremely difficult and problematic because people who mostly find themselves within the underground economy typically do not want to be identified. Therefore, there is a tendency for them to hide information that may influence findings and conclusions.

To resolve the shortcomings in the direct method of estimating the underground economy, studies like Kaufmann and Kaliberda (Citation1996), Feige (Citation1979), and Cagan (Citation1958) have proposed an indirect method of estimating this sector. Unlike the direct approach, which is micro and deals with the individuals in question, the indirect approach is macroeconomics in nature. According to Schneider and Enste (Citation2000), the indirect approach includes; ” … (i) the discrepancy between national expenditure and income statistics; (ii) the discrepancy between the official and actual labor force; (iii) the electricity consumption approach of Kaufmann and Kaliberda (Citation1996); (iv) the transaction approach of Feige (Citation1979); and (v) the currency demand approach of Cagan (Citation1958)”. Despite its widely used, several criticisms and shortcomings regarding the indirect method of estimating the underground economy exist. For instance, most of these methods estimate the underground economy using a single variable as an indicator and cause of the underground economy. But as defined by several researchers (Breusch, Citation2005; Draeseke & Giles, Citation2002; Mazhar & Méon, Citation2017; Pyle, Citation1989; Schneider & Buehn, Citation2016), the “underground economy” is simultaneously affected by several variables, which manifest itself in different ways within the economy. Therefore, not accounting for these possible variables may lead to inconsistent and inaccurate results. Also, not all transactions are paid in cash. Especially in developing countries, some activities are paid in kind or in the form of debt settlement (Schneider & Buehn, Citation2016). Therefore, assuming that the underground economy deals with cash payment alone may under-represent the underground economy.

To overcome all the shortcomings associated with the direct and indirect methods, Frey and Weck (Citation1983) proposed that a more complex methodology, the MIMIC model, could be used to estimate the complex nature of the “underground economy” (Breusch, Citation2005). The MIMIC model relies heavily on the statistical assumption and theory of unobserved variables, which indicates that the underground economy cannot be measured and observed directly, but there are multiple causes of this phenomenon resulting in multiple indicators to be measured. The model explicitly involves combining multiple economic indicators that are thought to be correlated with underground economic activity and using a statistical model to estimate the size of the “underground economy” based on these indicators. The MIMIC model is argued to produce a more reliable estimate compared to other statistical methods when calculating the size of the “underground economy” (Pyle, Citation1989; Schneider & Enste, Citation2000). Although the MIMIC model is subject to limitations such as the choice of variables and empirical limitations on data availability, Tedds & Giles (Citation2002) have argued that the strength of the MIMIC model far outweighs the weakness. Also, according to Cassar (Citation2001), this approach does not need restrictive assumptions compared to other methods. And according to Schneider and Enste (Citation2000), “this flexibility in the methodological application could lead to some progress in estimation techniques for the size and development of the informal economy, hence potentially superior to other estimation methods”.

3.2. Participation in the underground economy

Embedded in the definition of the “underground economy”, we can conclude that the sole participation in this sector is for tax purposes. People participate in this sector by either not reporting all their income to the tax authority to attract the appropriate tax or to avoid some labor market regulations (Pyle, Citation1989). According to Allingham and Sandmo (Citation1972), individuals would continue to evade taxes or participate in underground economy activities so long as the expected penalty is less than the standard income tax rate. Also, they argue that people participate in the underground economy because the consequence or penalty after detection or even the probability of detection is very low. Srinivasan (Citation1973), in his study, also concluded that a progressive tax rate incentivizes people to participate in the underground economy. Meanwhile, Christiansen (Citation1980) concluded that depending upon the precise nature of the relationship between the probability of detection and the penalty rate, an increase in the penalty rate might encourage evasion and hence participation in the “underground economy”. This theoretical conclusion is also consistent with Witte and Woodbury (Citation1985) when they also concluded that the individual would intend to report more of his income when there is an increase in the probability of agency action (such as the ability to audit and impose civil penalty).

Isachsen and Strøm (Citation1985) suggest that for people to risk working in the “underground economy”, the expected net wage must be greater than the net tax wage in the formal economy. They argue that individuals will devote more hours working in the “underground economy” as long as the wage rate in the formal sector is low. Interestingly, individuals’ decision to join the “underground economy” depends also on the interaction among tax evaders (Benjamini & Maital, Citation1985). For instance, individuals may feel reluctant to pay their taxes if tax evasion is common in the environment where they find themselves because it will be fair to them to evade too. But, if most taxpayers embrace taxes and frown on evasion in an environment, then any taxpayer might find it very difficult not to declare all of their income.

3.3. Economic consequences of the underground economy and tax evasion

Tax evasion and the “underground economy” have several implications for economic growth. One obvious consequence posed by the existence of the “underground economy” is that some incomes from economic activities go untaxed which tends to reduce government revenue. Therefore, every unit of the existence of the “underground economy” represents revenue loss for the government. When this happens, government revenue may be affected, which may eventually impact the number of public goods (roads, healthcare facilities, among others) produced by the government. The multiplier effect of this government revenue loss may significantly impact the economy’s growth. Furthermore, Pyle (Citation1989) argues that data about inflation and growth rates may be inaccurate if the underground sector takes a significant share of total economic activity. For instance, the government may decide to utilize monetary and fiscal expansionary measures to restore the economy to full employment potential (higher GDP and lower unemployment rate); however, because the economy is currently operating at, or very close to its maximum capacity but due to misinformation this instead of increasing output, could potentially increase the price of goods and services. Thus, with the presence of the “underground economy”, most government policy becomes ineffective.

The underground economy’s existence, growth, and tax evasion pose welfare losses upon society through inefficient use and allocation of resources (Pyle, Citation1989). Peacock (Citation1983) also argues that the presence of the “underground economy” may lead to inefficient uses of resources, both human and physical. According to Peacock (Citation1983), “some individuals with particular aptitudes and acquired skills that may be appropriate for the industry may choose to enter into any forms of employment (including self-employment) that are difficult to tax but in which they are less skilled and not so well trained”.

3.4. Policy issues

As argued by some scholars, the underground economy and tax evasion at some point possess some potential benefits to society. For instance, the underground economy serves as a lifesaving jacket for most people to find ends meet in times of crisis (Schneider & Enste, Citation2002). The sector sometimes provides additional employment opportunities and extra income to the needy population. However, despite some potential benefit to society at a particular time, the presence of the “underground economy” and tax evasion poses some threat to resource allocation, reduce government revenue, and renders some fiscal and monetary policies ineffective. This means there is an optimal level of informality and tax evasion that maximizes aggregate welfare. However, beyond this optimal point, the “underground economy” and tax evasion will greatly affect the economy.

Moreover, to eliminate evasion and the growing nature of the “underground economy”, policymakers must be able to set the law-enforcement variables (probability of detection and the severity of punishment) high enough to be greater than the tax rate. This will eventually ensure that no individual takes the chance of under-declaring their returns, and evasion would be eliminated because the penalty associated with evasion and underground economy participation would be higher than the actual tax rate evaded. Other studies like Clotfelter (Citation1983) and Graetz and Wilde (Citation1985) have argued that lowering the tax rate tends to increase compliance and reduce evasion and underground economy participation.

4. Theoretical underpinning

The endogenous growth theory is among the theories that tend to explain economic growth and how it is affected by the “underground economy”. According to the endogenous growth theory, the “underground economy” can have both positive and negative effects on economic growth, depending on the context and the prevailing circumstances (Goel et al., Citation2019). This theory emphasizes the role of innovation, knowledge accumulation, and human capital in driving economic growth. However, in the policy tool, these variables could be influenced by the existence of the “underground economy” (Grossman & Helpman, Citation1994). The “underground economy” could be seen from the lens of the endogenous growth theory as a potential source of innovation and productivity growth (Cziraky & Gillman, Citation2004). For instance, the underground economy may serve as a training ground for entrepreneurs and individuals in small businesses. This capacity building will lead to innovation, and knowledge spillovers, which tends to increase economic growth. Thus, entrepreneurs who operate in the underground economy may learn valuable skills and develop innovative strategies that can be applied in the formal economy, leading to productivity growth and economic development. Additionally, those without access to occupations in the regular sector may find employment prospects in the underground economy (Fugazza & Jacques, Citation2004). This can help reduce poverty and increase economic participation, leading to higher human capital and economic development.

However, the negative consequences of the “underground economy” on economic growth and development should not be ignored. From the lens of the endogenous growth theory, the underground economy can also lead to market distortions and create unfair competition (Singh et al., Citation2012). For example, firms that operate in the underground economy and evade taxes may have a cost advantage over firms that operate legally, leading to market distortions and the displacement of legal businesses. Moreover, the underground economy can also reduce government revenue, which can lead to a decline in public investments (Amoh & Adafula, Citation2019). Public investments, such as infrastructure, education, and healthcare, are essential for economic growth, and a decline in such investments can slow down economic development.

Nevertheless, given the prevailing circumstances within the study area, Ghana, this study examines the effect of the “underground economy” and tax evasion on economic growth through the lens of the endogenous growth model. This is due to the fact that it is impossible to predict in advance how the shadow economy would affect economic growth in Ghana.

5. Empirical review

Although empirical works into Ghana’s “underground economy” size and the level of tax evasion is scanty, the study provides a through overview of empirical evidence conducted so far into this phenomenon in Ghana. This overview of empirical evidence is presented in Table .

Table 1. Empirical evidence

6. Methodology

Th study used secondary annual data from the World Development Indicator (WDI), the Bank of Ghana (BoG) and the Economic Freedom Index spanning from the years 1990 through 2020. Data availability, theory, and the fact that the variables statistically matched the model better were the three reasons that affected the sample period and variables employed.

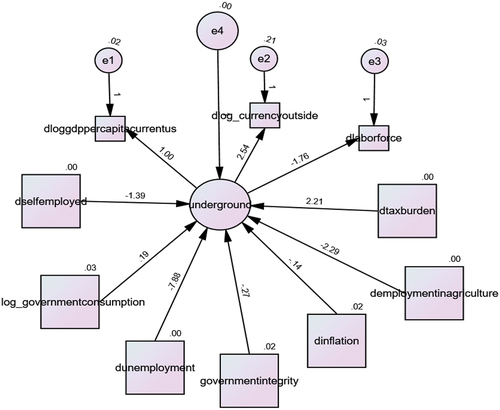

6.1. Underground economy

The study adopts the MIMIC model approach to calculate the size of Ghana’s “underground economy”. The MIMIC method views the “underground economy” as a “latent” variable because it cannot be immediately detected. According to Schneider et al. (Citation2010), “the model tests the consistency in an economic theory by examining actual data with the hypothesized relationships between observed (measured) variables and the unobserved (latent) variable”. Although the economic activities within the sector cannot be observed directly, its effects on the economy at larger is inevitable. As a result, the MIMIC method uses a Simultaneous Equation Model (SEM) to look at how the observable and unobservable variables are related. Figure provides the framework for the MIMIC model.

From the figure above, the underground economy’s size is caused by certain observable variables

. These causal variables provide incentives to people and businesses to engage in underground activities. Although these variables may not necessarily represent the underground sector, it has a replicate effect on the sector’s size. And since the size of the “underground economy” is represented by a latent variable

we can only observe the effect of these causal variables on certain indicators

. These indicators of the size of the “underground economy” can be directly observed and measured. Therefore, the MIMIC model tries to establish the statistical relationships that exist among the latent (unobserved) and manifest (observed) variables.

Mathematically, the MIMIC model can be described as

The “underground economy” is connected to its indicators and some set of observable causes in Equationequation (1)(1)

(1) and (Equation2

(2)

(2) ) respectively. The above equations could be solved by first solving for the reduced form of the equation. Hence the Reduced form equation will be;

Where is a matrix with dimension

and rank equal to 1 and

is a vector of dimension

which is normally distributed with zero mean and a constant variance. The reduced form equation can be estimated using the maximum likelihood estimator.

7. Empirical Models

7.1. Underground economy

According to Asiedu and Stengos (Citation2014), the leading causes or determinants of Ghana’s underground economy may include self-employment, tax burden, inflation, the size of government consumption, tax morale, social security payment, unemployment and institutional quality. The indicator variables reveal the existence of the “underground economy”. These may include the amount of labor participation in the official system, the amount of cash held outside the banking system, and growth in GDP per capita. Hence the hypothesized relationship between the latent (unobservable) variable and the observable causes and indicator variables is shown in the figure below. Figure shows MIMIC 7-1-3 model, thus, in this model, we will have seven multiple causes of the “underground economy” and three indicators of this economy.

The index of the “underground economy” is estimated by Equationequation (4)(4)

(4) ,

In Equationequation (4)(4)

(4) , “the structural coefficients are multiplied for the filtered data for stationarity and the latent variable is estimated in the same transformation of independent variables (first difference)”. The latent variable is now integrated to obtain the index for the “underground economy”. To generate a time series variable for the “underground economy”, a number of calibration procedures are proposed. However, due to several advantages, we used the calibration procedure proposed by Nchor and Adamec (Citation2015). According to Nchor and Adamec (Citation2015), the “underground economy” size can be estimated from the equation below.

In EquationEquation (5)(5)

(5) , “the size of the underground economy is generated as a percentage of the official economy.

is the estimated value of the latent variable at time t; The study selected the year 2004 as the based year in the calibration process because it is possible to build an average with eight different estimates and almost all the kinds of methodologies.

is the calculated MIMIC index at time t.

is the estimate of the underground economy in the base year. And

is the exogenous estimate of the underground economies in 2004. The exogenous estimate introduces into this model is helpful to guarantee greater truthfulness of the estimates. This exogenous information is chosen from a year in which several estimates of the underground economy exist”.

7.2. Tax evasion

The study adopted the model proposed by Feige (Citation1981) to estimate the value of tax evasion in Ghana. Thus, the value of tax evasion from the size of the “underground economy” was estimated by multiplying the size of the “underground economy” by the average tax rate (ATR). This is done on the assumption that the standard rate would have been paid on incomes had it not been concealed from tax officials. Mathematically it is represented as,

7.3. Tax evasion and economic growth

To estimate the effect of tax evasion on economic growth the study employed the Ordinary Least Square (OLS) specify below.

Real GDP was used to measure economic growth, TEGDP represents the percentage of tax evasion in the country, INF represents the inflation rate, GNS is the Gross national savings, PSI represents the public sector savings, FDI is the foreign direct investment, IRS is the interest rate, HSEXP is Health sector expenditure, and TERROLL is enrollment in tertiaries. We expect tax evasion to have a negative effect on economic growth.

7.4. Underground economy and economic growth

To estimate the effect of the “underground economy” on economic growth the study employed the Ordinary Least Square (OLS) specify below.

Real GDP was used as a measure for economic growth which is the dependent variable, FDI represents Foreign Direct Investment total, HSEXP is Health sector expenditure, TERROLL is enrollment in tertiaries, INF is Inflation rate, IR represent interest rate, UNEMPT represents unemployment rate and UE is the size of the “underground economy” measured as a percentage of GDP (own estimates). All variables except inflation, unemployment and interest rate, are expected to have a positive sign with economic growth. As already discussed, the sign of the underground economy on the formal economy cannot be determined a prior. Hence, we expect either a positive or negative sign.

8. Justification of variables

8.1. Causal variables

8.1.1. Tax and social security contribution burden

Tax burden remains a primary determinate of the underground economy in literature. Because when citizens are paying a greater portion of taxes, there is a high propensity to evade these huge taxes. The overall proportion of direct and indirect taxes, including social security contributions, expressed as a percentage of GDP is used to calculate the tax burden. According to Christopoulos (Citation2003), when direct and indirect taxes increases, “taxpayers move into the underground economy as quickly as they move out of it when they decrease”. Therefore, tax burden was expected to have a positive sign and effect on the underground economy.

8.1.2. Real government consumption

The size of the public sector is another cause why people engage in the underground economy. Because the public sector is mostly associated with a bureaucratic system which sometimes becomes problematic to follow and abide by, most people use the underground economy to hide from these bureaucratic regulations that exist within the public sector. An increase in the public sector and the degree of economic system regulation provides a relevant encouragement for people to participate in the informal sector (Aigner et al., Citation1988). Real government consumption is used in this study to proxy State activities’ presence, and the coefficient in the model is expected to have a positive sign.

8.1.3. Unemployment

The unemployment rate on the underground economy’s size is not clearly stated in the literature. Medina and Schneider (Citation2019) argue that unemployment in the formal sector would compel people to participate in informal economic activities, indicating a favorable correlation between the two. However, Tedds & Giles (Citation2002) also argue that the unemployment rate has an inverse effect on the “underground economy”. This is because a rise in unemployment has the propensity to reduce GDP growth. And because GDP has a positive correlation with the underground sector, it will force it to reduce. On this basis, Tanzi (Citation1999) draws the equivocal conclusion that there is no clear correlation between the unemployment rate and the “underground economy”. Therefore, the expected sign of unemployment rate on the underground economy is unclear.

8.1.4. Self-employment

The percentage of the self-employed labour force contributes significantly to the underground economy (Dell’anno, Citation2003). Self-employed activities are usually associated with non-filing of tax returns and failure to keep records. According to Wondimu and Birru (Citation2020), the informal economy is directly related to the rate of self-employed people in the country. Therefore, in our MIMIC model, we expect that the rate of self-employed people in Ghana will positively relate to the underground economy.

8.1.5. Agricultural sector employment

The size of the agricultural sector contributes significantly to the informal sector and has, over the years, been used as a proxy for the informal sector due to several reasons, such as a lack of formal regulations in the sector, with majority of their activities done at the blindsight of the tax authorities. Again, workers in Ghana’s agricultural sector are mostly engaged in indecent work since they do not contribute towards any social security. Thus, although these workers make some profits and benefits, they mostly do not contribute anything to the tax authorities regarding tax or social security. Therefore, the agricultural employment size is expected to affect the underground economy positively.

8.1.6. Institutional quality

Corruption remains one crucial determinant of underground economic activities. According to Fijnaut & Huberts (Citation2000), “corruption is an umbrella concept covering all or most types of integrity violations or unethical behaviour”. Therefore, government integrity is used to proxy the quality of state institutions in the study. Governmental integrity measures how free a country is of corruption (Fredriksson et al., Citation2007). According to the OECD (Citation2017), “government integrity is the alignment of government and public institutions with larger principles and norms of behaviour that protect the public interest while avoiding corruption”. Nchor and Adamec (Citation2015) argues that people are engaged in the informal sector because of weak government regulatory laws. According to Wondimu and Birru (Citation2020), an improvement in the fight against corruption in a given country will reduce economic activities with the underground sector. Therefore, we expect that government integrity will negatively affect the size of the “underground economy” in Ghana.

8.1.7. Inflation

Inflation’s role in affecting the underground economy’s presence and growth over the years has been underestimated. According to Crane and Nourzad (Citation1986), inflation rates positively influenced tax evasion and underground economy participation. This is because when prices of goods and services keep increasing, the individual intends to conceal some of his income to keep up with the bundle of goods and services they can purchase. Therefore, inflation is expected to affect the underground economy’s size positively.

8.1.8. Indicator variables

8.1.8.1. Real Gross Domestic Product (variable of scale)

Real GDP in this study is chosen as a reference variable for identification purposes and its theoretical implications. The relationship between real GDP and the “underground economy” is ambiguous and cannot be determined a prior (Dell’anno, Citation2003). In situations of economic downturn, the most immediate effect on the formal economy is the loss of jobs. This tends to drive most individuals into the underground economy because it serves as a “life jacket” for businesses and people who are having financial difficulties; as a result, it rises as the GDP falls. However, due to the decrease in GDP, the demand for goods and services within the underground economy may also decrease, eventually offsetting the earlier effect.

8.1.8.2. Currency in circulation outside of banks

Undoubtedly, most payment for goods and services within the “underground economy” is only made with cash and no cheque or credit card to avoid auditing controls. Due to this assumption, the “underground economy” size can be estimated by comparing the actual cash demand with the expected cash demand in situations with no “underground economy”. The presence of the “underground economy” is expected to positively affect the currency in circulation outside the banks or the demand for money.

7.1.8.3. Labor participation rate

Labor participation is used as an indicator for the presence of the “underground economy” because studies like Tanzi (Citation1999) have shown that in situations of economic depression the most immediate effect on the formal economy is loss of jobs and this tends driving most of the individuals into the underground economy. Therefore, a decline in the official labor force participation rate could indicate an increase in the size of the underground sector. Therefore, the underground economy is expected to affect labor participation in the official system negatively.

9. Results and discussion

9.1. Descriptive statistics

The descriptive statistics for key important variables employed in the study are presented in Table . The results indicated that, on average, GH₵ 3774.9439 million are in circulation outside the bank domain with a standard deviation of GH₵ 3962.6907. Over the years, currency outside the banks has been used to proxy the existence of the underground economy, where higher deviations represent a higher underground economy (Amoh & Adafula, Citation2019). Therefore, such an average and standard deviation would imply that there is much money in circulation in Ghana outsides the banks, which may influence the size of the “underground economy”.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics

Again, Table reveals that real GDP has an average of GH₵ 2652.305445 with a standard deviation of GH₵ 3842.3227. Furthermore, the labor force participation rate in the formal economy in Ghana has an average of 72.83, with a standard deviation of 2.622. Again, it was evident from the summary statistics above that in Ghana, the tax burden on citizens is 78.3185 per cent on average, with a standard deviation of 5.409 per cent, indicating higher taxes on individuals in the country. A higher tax burden generally means that taxpayers are required to pay a larger percentage of their income or wealth in taxes to the government which affect their available money to spend or save. Tax revenue to GDP, a proxy for the average tax rate in Ghana, has an average of 14.3717 per cent of GDP with a standard deviation of 2.9359 per cent of GDP. From Table , we realize that the agricultural sector employment, on average, constitutes 49.73 per cent of the total employment in the country, with a standard deviation of 8.609 per cent. This implies that, under the years of consideration, almost half of the total employment in Ghana can be seen in the agricultural sector. The mean for unemployment and self-employment is 6.1 per cent and 83.107 per cent, respectively, with a standard deviation of 1.6876 and 5.4356 per cent, respectively. Government Integrity was found to be 41.598 per cent on average, with a standard deviation of 10.3745. Government integrity is the ability of government to fight corruption and corrupt practices. The score of government integrity ranges between 100 and 0 inclusive, where 100 indicates very little corruption and 0 indicates a very corrupt government. Therefore, a mean of 41.59 suggests the government is doing quite well when it comes to corruption, although it is not totally eradicated in the country. Again from Table above, the inflation rate had a mean of 19.7 per cent and a standard deviation of 13.13 per cent.

10. Stationarity test

In order to avoid spurious regression and unreliable estimates, the stationary properties of the variables used in the study were verified using the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) and the Phillip Perron (PP) approach both at levels and differenced. The results are presented in Tables in the Appendix. Table shows the results from the stationarity test conducted using the lead variables at levels. From the table, we realise that all the test static values from both the ADF test and PP test are, in absolute terms, less than all the critical values except that of government consumption which is greater than the critical values. Therefore, since the static test values are less than the critical values except that of government consumption, we reject the null hypothesis and conclude that the data is not stationary at their levels except for government consumption, which has a unit root at their level data. The study proceeded further to check the data’s stationarity when the variables have been differenced. The result is presented in Table . When the data was differenced, we realise from the results shown in Table that all the variables except government consumption become stationary, with their test statistic being greater than the critical values. Thus, the variables have their statistical properties to be constant when their differences are taken.

11. MIMIC model estimates

In order to estimate the size of the “underground economy”, the study used the MIMIC model to examine the structural and measurement model for the underground economy. There were seven (7) casual variables to predict the country’s underground economy with three (3) indicator variables as presented in Figure . The results from the Maximum Likelihood Estimator (MLE) are presented in Table .

Table 3. Estimates from the MIMIC model

The Chi-square, Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) were used to evaluate how well the proposed model fits the data. Since the probability value of 0.081 is higher as compared to the alpha level of 0.05, we fail to reject the null hypothesis of good fit and conclude that the hypothesized model and the observed data fit pretty well. This conclusion is supported by the CFI value of 0.76 and the GFI value of 0.905. The conclusion was based on the suggested cutoffs of 0.9 stipulated by Hu and Bentler (Citation1999) and Kenny, Kaniskan and McCoach (Citation2014).

In Table , we realize that the effect of the tax burden on the “underground economy” achieved its positive expected sign. This means that an increase in the level of the tax burden on the citizens will increase underground economy activities. Likewise, a decrease in tax burden will cause a significant decrease in underground economy activities. This is because higher tax burdens are a result of higher taxes (Feige, Citation1990), and when the burdens of taxes are high on individuals, their only weapon to mitigate this burden is to conceal their economic activities from government authorities to avoid paying those taxes which will eventually increase the underground economy activities. We realize from the results present in Table that this causal effect of the tax burden on the “underground economy” participation is significant at the 1 per cent level because its p-value of 0.002 associated with the test statistic is less than the conventional 5 per cent alpha level. This conclusion is consistent with the Srinivasan (Citation1973) and Yitzhaki (Citation1974) model, suggesting that higher taxes will lead to more people participating in the underground economy. Again the study is consistent with several empirical studies, such as Clotfelter (Citation1983), Crane and Nourzad (Citation1986), Feige (Citation1990), and Song and Yarbrough (Citation1978).

The tax burden remains a primary determinate of the underground economy in the literature. Because when citizens are paying a greater portion of taxes, there is a high propensity not to comply or evade these huge taxes. From our results, it is evident that there is a strong relationship between the tax burden and the size of the “underground economy”. We realize that a percentage change in the tax burden will cause almost a double and half percentage change in the underground economy activities. This confirmed the studies of Dell’Anno et al. (Citation2007), and Amoh and Adafula (Citation2019) when they concluded that an increase in tax burden would lead to a high “underground economy”. According to Amoh and Adafula (Citation2019), when individuals feel that the tax they are paying are high and pose a huge burden on them, they are encouraged now by either not making their activities known to the tax authorities or underreporting their revenue to attract less tax. This decision eventually will increase the underground economy.

For instance, available data from the Bank of Ghana shows that, after the announcement of the imposition of the Electronic Transfer Levy (E-Levy) in November 2021, the value of transactions done using the mobile money platform declined drastically from GH₵86.1 billion at the time of announcement to GH₵76.2 billion as at January 2022 indicating a drop of GH₵9.9 billion in value. According to the Bank of Ghana, the value will further decrease after the implementation because individuals feel that using the online payment platform will be costly due to the high taxes and charges, the burden will be high, and therefore, they will now have no option but to move out of that platform and find another way to still operate without not paying the huge taxes, which will eventually increase the size of the “underground economy”. Thus taxpayers may be encouraged to engage in tax-evading activities as long as the tax burden is huge (Amoh & Adafula, Citation2019).

From the results presented in Table , we realize that final government consumption, which was used to represent the size of the public sector, attained its expected positive sign with the “underground economy”. Thus, it is evident that increasing government spending or the size of the public sector will eventually increase the “underground economy”. The results show that a percentage increase in the size of the public sector will increase the size of the “underground economy” by 18.9 per cent. This relationship was found to be significant at 5 per cent significance level. This effect was consistent with the studies of Aigner et al. (Citation1988), who postulated that an increase in the size of the public sector and the degree of economic system regulation provide a relevant encouragement for individuals to participate in the “underground economy”. According to Tedds and Giles (Citation2002), huge regulation burden tends to affect the hidden economy positively. Thus, “more State” in the market will increase regulation, eventually incentivizing people to operate in the underground economy. Another way to view this is that increasing the state interference will crowd out the private sector by forcing them to increase their participation in the underground economy.

From the study, we also realize that the coefficient on government integrity attends its negative expected sign with the size of the underground economy. In order words, we found out that government integrity is negatively related to the size of the underground economy in Ghana. Such that if government integrity should increase by one percentage point, then there will be an inverse response on the underground by decreasing its size by 26.7 per cent. Increasing government integrity will mean an increase in transparency and the government’s ability to fight corruption and corrupt individuals. However, when governments cannot be trusted to deal with corruption, transparency and accountability, it loses their integrity in the sights of the citizens, which will eventually encourage more people to evade taxes due to the government, hence increasing the size of the “underground economy”. The study results are consistent with the conclusions from Medina and Schneider (Citation2019) and Wondimu and Birru (Citation2020).

According to Wondimu and Birru (Citation2020), institutional quality negatively affects the size of the “underground economy” estimations. Thus, if the quality of state institutions improves or does better in the fight against corruption, then it will be expected that the size of informal economic activities will reduce. Again, people are engaged in the informal sector because of weak government regulatory laws. A recent survey by Barometer (Citation2021, April 12) reveals that “Ghanaians are more willing to pay taxes if they perceive the government as doing a good job of delivering basic services and preventing corruption”. This is to say that majority will conceal their economic activities from the government by participating in the “underground when they do not trust that the government can deliver on its promise.

Studies like Batrancea et al. (Citation2013), Wahl et al. (Citation2010) have concluded that when citizens trust the tax authority and the government, it enhances voluntary compliance with tax laws, therefore decreasing their participation in the underground economy. Corruption, a chronic problem that can stymie growth in developing countries, is one element weakening public trust. Bertinelli et al. (Citation2020) found that tax officers’ involvement in receiving bribes from small businesses resulted in a considerable decline in tax compliance in Mali. Although the government and other previous governments have declared a zero-tolerance to corruption, the majority (84%) of Ghanaians, according to the Afro barometer survey, still postulate that tax officials are corrupt and will, for that matter, not pay their taxes to corrupt individuals. With this distrust in the tax process and officials, there is a higher indication of an increase in Ghana’s underground economy size, as indicated in Table .

Institutions are responsible and mandated for ensuring that citizens and businesses comply with tax and auditing principles. As said earlier, the quality of institutions has a high tendency to decrease tax evasion and underground economic activities. Studies like Witte and Woodbury (Citation1985) have argued that when institutions take responsibility for auditing people and prosecuting them for civil fraud and imposing a penalty on them, it has a high deterrent effect which will eventually push many people out of participating in the “underground economy”.

Again, it can be seen from Table that the size of agricultural employment is negatively related to the underground economy size in Ghana. Thus, an increase in the size of the agricultural sector in Ghana will decrease the country’s underground sector. Although this was not the expected sign, the effect appears to be significant in explaining the size of the underground in Ghana. This is because Ghana’s agricultural sector has gone through several transformations and modernization over the years. With several programmes that are specific to the sector, like Cocoa Life and Planting for Food and Jobs, among others, the sector has received formal recognition from the government and serves as an avenue for job creation and employment for many. This has tend to reduce people’s participation in underground economic activities. Also, most agricultural sector workers receive a lot of incentives and subsidies like free provision of seedlings, fertilizers, and even scholarship education for their relatives from the government. Such provisions decrease the tax burden on the participants in the agricultural chain industry, eventually decreasing participation in the underground economy. Also, in most cases, before these incentives and packages are rolled out to the industry players, they are registered, and records are taken to make their business and operation formal to the government.

Self-employment is frequently associated with underdeveloped countries, and such activities are counted as formal employment, provided they are registered. Inadequate control of such self-employment operations, on the other hand, could lead to an increase in underground economic activity (Nchor & Adamec, Citation2015). Self-employment was also seen to have an inverse relationship with the underground sector in Ghana. This is primarily because there is a positive relationship between agricultural sector employment and self-employment in Ghana, as shown in Table . The agriculture sector in Ghana is primarily owned and operated by private individuals. Again, the Planting for Food and Job Programme has enrolled many private businesses into the agricultural supply chain, increasing agricultural sector employment (Tanko et al., Citation2019). Therefore, warranting the inverse effect on the “underground economy”. Unemployment and inflation rate was found to affect the “underground economy” negatively. Although the effect of inflation on the “underground economy” is not significant, that of unemployment is significant. Although the effect of unemployment on the size of the “underground economy” is unclear in literature, it was evident from our study that there is an inverse relationship in Ghana. However, the results from this study contradict the findings of Amoh and Adafula (Citation2019) when they found a positive relationship between unemployment and the underground economy in Ghana. However, according to Tanzi (Citation1999), this effect will only be true if people in the workforce who are traditionally known as unemployed make a living through unreported activities. If not, according to Tanzi (Citation1999), this effect will be a result of a measurement problem. The conclusion from our study confirms the findings of Tanzi (Citation1999) and Giles & Tedds (Citation2002) when they contend that since the “underground economy” has a positive correlation with GDP growth, a rise in unemployment will lead to a decline in the underground sector. Moreover, according to Tanzi (Citation1999), the official unemployment rate is less correlated with the underground economy because of the heterogeneous compositions of the labor force within the underground economy.

From Table , we realize that the money in circulation outside the domain of banks in Ghana is a significant indicator of the presence of the “underground economy”. Thus, it is evident from Table that there is a positive relationship between the currency in circulation and the size of the “underground economy”. This means that as the presence of the underground increases, the money in circulation outside banks also increases. It is prudent to note that these findings are consistent with several studies like Nchor and Konderla (Citation2016), Nchor and Adamec (Citation2015), Schneider and Buehn (Citation2016), and Amoh and Adafula (Citation2019). This is so because most transactions within the “underground economy” are primarily done with cash or kind as the medium of exchange, and it is mainly outside the banks or institutions to avoid taxes. In Ghana, for instance, the growing nature of our digital space and the use of mobile money for business transactions has led to the drastic increase in our currency in circulation outside the bank’s domain. Available data from the Bank of Ghana (BoG) demonstrates that over $99 billion (GH561 billion) in mobile money transactions were made in 2020, while the volume of cheques and cash transactions in the country stood at $29 billion. This means that a more significant percentage of the financial transactions in the country were done outside the banks. Furthermore, since these transactions did not pass through the banks, there is a higher tendency of evading taxes either by underreporting or not reporting at all, which will eventually increase the “underground economy” participation. Therefore, the growing currency demand outside the financial institutions is a strong indication of the presence of the “underground economy” (Feige, Citation1979, 1980).

The labor force participation in the formal economy was found to be a significant indicator of the presence of the “underground economy” in Ghana. Thus, the study shows that labor force participation in the formal economy negatively affects the “underground economy”. Such that when employment in the formal economy increases, it will significantly decrease the size of the underground economy. And when people lose their jobs in the formal sector, their immediate way of surviving is to engage in underground economic activities. These findings is consistent with Nchor and Konderla (Citation2016), Nchor and Adamec (Citation2015), Schneider and Buehn (Citation2016) and support the hypothesis of Martino (Citation1980) when he concluded that the lower labor force participation in the formal sector is as a result of the thriving underground economy.

When labor force participation in the formal economy is low, it can create incentives for individuals to engage in informal, unreported economic activities to earn income. This can increase the size of the “underground economy” and result in lost tax revenue for the government. On the other hand, when labor force participation in the formal economy is high, it can reduce the size of the “underground economy” by providing individuals with legal employment opportunities and reducing the incentives to participate in informal economic activities. This can result in increased tax revenue for the government and a more stable and productive economy.

Policies that promote labor force participation in the formal economy can help reduce the size of the “underground economy”. For example, policies that improve access to education and job training, increase the availability of legal employment opportunities and reduce the regulatory and tax burdens on businesses can all encourage more people to participate in the formal economy. Additionally, policies that improve the efficiency of government services, reduce corruption, and enhance the rule of law can help increase trust in the formal economy and reduce the incentives to engage in informal economic activities.

12. Estimation of the underground economy

In order to estimate the “underground economy’s” size as a percentage of GDP, the study used an exogenous value of 45 percent as the base year and this was obtained from the study of Medina and Schneider (Citation2019). Table presents the summary statistics of Ghana’s underground economy.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics of the underground economy percentage of GDP

From Table , we realize that in Ghana, on average, the underground economy constitutes about 44 per cent of the official GDP of the economy, with a standard deviation of 4.7 per cent. This result is relatively consistent with the estimates from Medina and Schneider (Citation2019) and Schneider et al. (Citation2010) who recorded an average of 40.7 per cent of official economy from 1999 to 2007. The maximum value of the “underground economy” is 49.96 per cent of GDP, and the minimum value is 37.22 per cent of GDP. Figure presents the trends in the “underground economy” over the years.

Figure 3. Trend in the size of the underground economy in Ghana, 1990–2020.

From Figure , we realize that Ghana’s underground economy has not been constant but has increasingly varied across the years. The highest values of the underground economy were obtained in 1990 and 2012, while the lowest value was obtained in the year 2000. The estimates from this study seem to be higher than the values obtained by Amoh and Adafula (Citation2019), and Ocran (Citation2018) but seems to be consistent with the estimates of Asante (Citation2012) and Schneider (Citation2005). This discrepancy between the estimate from Amoh and Adafula (Citation2019), and Ocran (Citation2018) and this current study is largely due to the methodological approach used by these studies. Amoh and Adafula (Citation2019) and Ocran (Citation2018) assume that the size of Ghana’s “underground economy” is affected by the tax burden alone in their currency demand approach. However, we realize that other factors such as the government integrity, employment in the agricultural sector, the size of the public sector, self-employment, unemployment and corruption affects the size of Ghana’s underground economy. Therefore, by including these other factors in the estimation of the “underground economy”, the values will be higher than the values reported in the studies of Amoh and Adafula (Citation2019) and Ocran (Citation2018). Again, from our estimation, the underground economy’s size for the past five years (since 2016) has been declining at a decreasing rate.

13. Tax evasion

The study proceeded to examine the extent of “tax evasion” or revenue loss due to the presence of the “underground economy”. The “underground economy” participation is primarily associated with tax evasion. According to Pyle (Citation1989), people participate in this sector by either not reporting all their income to the tax authority to attract the appropriate tax or to avoid some labor market regulations. Table presents the summary statistics of tax evasion in Ghana due to the underground economy was estimated.

Table 5. Tax evasion as a percentage of GDP

From Table , it is evident that in Ghana, the value of tax evasion due to the presence of the “underground economy” is 6.28 per cent of GDP annually on average, with a deviation of 1.29 per cent. In other words, the amount of revenue the country losses on average is about 6.28 per cent of the total size of the economy. Again, it is evident from the study that the level of tax evasion in Ghana rages from 4 per cent of GDP to 9.6 per cent of GDP. This result relatively seems to confirm the findings of Asante (Citation2012), who found out that tax evasion in Ghana ranges from 4 per cent to about 14 per cent of GDP, with an average of 7 per cent of GDP. For countries like Ghana, this amount lost may be very significant in contributing to the nation’s development. The trend in the value of tax evasion as a result of the “underground economy” is presented in Figure .

In Figure , the study found some fluctuations in the trends of tax evasion in Ghana. The amount of tax evasion increased from its lowest value of 4 per cent of GDP in 1992 to its highest values of 9.61 and 9.64 per cent of GDP in 2004 and 2005, respectively. However, the value of tax evasion later declined drastically in 2006 from the 9.64 per cent of GDP attained in 2005 to 6 per cent of GDP in 2006. This decline in the level of tax evasion was because the country then was beginning to reap the benefits of macroeconomic and structural reforms and nearly 15 years of political stability (OECD, Citation2006). There was significant growth in domestic revenue mobilization, efficient expenditure management, and debt relief granted under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) debt relief programme, as well as debt reduction promises from the G8, all helped to strengthen the government’s fiscal condition at the time (OECD, Citation2006).

Again, we realize that the amount of revenue loss to the state, although it has been fluctuating over the last decade, is around the average of 6.4 per cent of GDP. In contrast, the amount of tax evasion in the country for the last four years, thus from 2016 to 2020, has fallen below the average of 6.4 per cent of GDP. This is because of the performance of the revenue authority in increasing its domestic revenue mobilization through the implementation of digital systems at most of the revenue collection checkpoints to reduce corruption. Also, the declining trend in the level of tax evasion ratio to GDP since 2016 is mainly due to the rapid economic growth experienced by the country at that point.

14. Relationship between tax evasion and underground economy

The relationship between tax evasion and the underground economy has received much scholarly work across several jurisdictions. This is because embedded in the definition of the “underground economy” is a principal motive of evading taxes by concealing activities from tax authorities (Pyle, Citation1989). Therefore, to add to the literature, the study examined the relationship between tax evasion, the underground economy, and tax revenue to GDP in the country. The results from the correlation analysis are presented in Table below.

Table 6. Relationship among tax revenue, tax evasion, and the underground economy

Table shows a positive relationship between tax evasion and the size of the “underground economy” in Ghana. Although this relationship is insignificant, it means that as the size of the underground economy increases (decreases), the value of tax evasion will also increase (decreases). This finding confirms the hypothesized definitions of Pyle (Citation1989). Thus, according to Pyle (Citation1989), “the underground economy may consistently perfectly legitimate activities, resulting in transactions (either in kind or for payment) between individuals, which are then hidden from the authorities, principally the tax authorities”. Therefore, activities carried out in the informal economy are mostly done so as to avoid the requirement of paying different direct and indirect taxes that would normally be involved with disclosing them to tax authorities. Therefore, underground economy participation and tax evasion will always have a positive relationship. Again this current study provides enough confirmation for several empirical works, such as Blackburn et al. (Citation2012), Emerta (Citation2010), Nchor and Konderla (Citation2016), and Amoh and Adafula (Citation2019), concerning the relationship that exists between the size of the underground and the level of tax evasion. Furthermore, according to Bekoe (Citation2012), tax evasion can erode the equity of a tax system by making honest taxpayers feel disappointed and enticed to join the decision to evade and engage in underground activities.

Also, the study found out that there is an inverse relationship between the size of the “underground economy” and tax revenue in Ghana. Although this relationship may be insignificant, it implies that an increase (decrease) in the “underground economy” participation will decrease (increase) the amount of revenue available to the state. We also realize a positive relationship between tax evasion and tax revenue in Ghana. If tax revenue increases (decreases), tax evasion has a higher propensity to increase (decrease). In Ghana, an increase in tax revenue does not necessarily mean an increase in the number of people who pay taxes but an increase in the tax rate or the number of taxes to be paid. And as suggested by the theoretical model of Allingham and Sandmo (Citation1972) and Srinivasan (Citation1973), a progressive tax rate tends to affect evasion positively. Therefore, although the revenue might increase due to the rise in the tax rate, it will eventually cause some economic agents to evade these taxes.

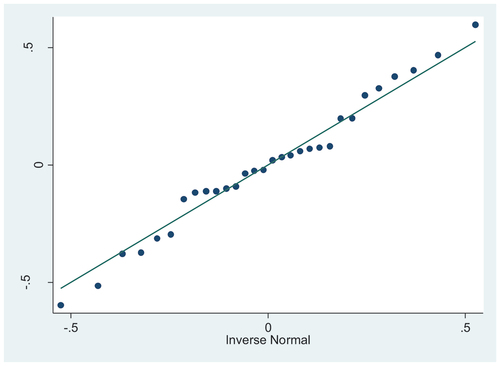

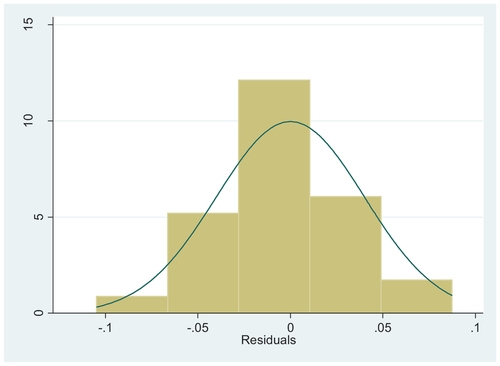

15. Effect of tax evasion on economic growth

The Ordinary Least Square (OLS) approach was used to analyze how tax evasion affects economic growth. The results obtained from the regression analysis are presented in Table . The model appears to be significant (6722.07, 0.000) with explanatory powers of 98.84 per cent and a constant variance (Breusch-Pagan test static of 1.03 with P-value, 0.3106). Also, the residuals plot (Figure , Appendix) suggests that the residuals are normally distributed and significant using the Shapiro-Wilk test (test static = 0.95436, P-value = 0.22093). Also, with a Durbin-Watson test value of 2.32235, we can conclude that the residuals are independent and uncorrelated.

Table 7. Effect of tax evasion on economic growth

From Table , we realize that the coefficients of inflation, interest rate and public sector savings were not significant, although they attained their expected sign. Foreign direct investment has a significant positive effect on economic growth in Ghana. This means that for the country to experience adequate and significant growth, some measures must be implemented to increase foreign investment in the country. The size of the government savings, government expenditure on health and tertiary school enrollment all achieved its expected positive sign on economic growth, and it was significant.

Tax evasion tends to affect economic growth negatively. Thus, from Table , we realize that when there is a unit increase in the level of tax evasion, it will cause economic growth to decrease by 36.2 per cent. However, when there is a percentage point decrease in tax evasion, economic growth is expected to increase by 36.2 per cent. This effect of tax evasion on economic growth is significant at a 5 per cent significance level and is consistent with the findings of several studies like Bekoe (Citation2012), Cerqueti and Coppier (Citation2011), and Omodero (Citation2019). Firms that evade taxes may have a cost advantage over firms that operate legally, which can lead to market distortions and the displacement of legal businesses (OECD, Citation2004). This can harm economic growth by discouraging legitimate businesses from investing and expanding.

According to Roubini and Sala-I-Martin (Citation1995), where “tax evasion” is perceived to be high, the government’s optimal policy is to suppress the financial sector to increase the face value of taxation. Such a government policy will reduce the efficiency of the financial sector, increase intermediation costs, reduce the amount of investment and eventually reduce the rate of economic growth. Hence, “tax evasion” affects the economic growth of a country negatively. Furthermore, our findings are consistent with Lin and Yang’s (Citation2001) conclusion that public goods are not productive in and of themselves. According to Lin and Yang (Citation2001), when tax rates are high, resources are shifted from the inefficient public sector to the productive private sector to enhance economic growth. However, the government receives little benefit from these growths from the private sector.