Abstract

This article examines how indigenous ontologies of gold, land, and rivers shape extractive practices, based on ethnographic field work in Ghana. I draw from political ecology to account for how invisible properties of the subsoil become entangled with social realities. In Ghana, understandings of the subsoil as more-than-material worlds inform rituals, taboos, and other protocols. Through such protocols, chiefs, spiritualists, and others emerge to govern subterranean access. This research shows that subterranean sovereignty extends beyond the state to include invisible forces of extractive landscapes, presenting ontological challenges to neoliberal land acquisition and gold privatization processes. The study also shows that mineral matters have resisting and intentional capacities that are constituted through resource making. Such resisting capacities contradict dominant views of resources, generating new understandings of resources as things that do not always become. The study suggests the need to attend to complicated forces of extraction and mining regulations. Such an approach is not merely epistemological intervention for addressing the subsoil’s invisible properties but provides important insights to reimagine contemporary extractive practices as ontological struggles over the subsoil wherein indigenous persons produce and challenge claims to land through more-than-material relationships with the environment.

基于在加纳的民族志实地工作, 本文探讨了黄金、土地和河流的土著本体论如何塑造采掘实践。根据政治生态学, 我诠释了底土的无形属性如何与社会现实交织在一起。在加纳, 将底土理解为超物质世界, 能诠释仪式、禁忌等礼仪。由此, 首领、通灵者等管理地下开采。研究表明, 地下主权延伸到国家范畴之外, 包含了采掘景观的无形力量, 对新自由主义土地征用和黄金私有化进程提出了本体论挑战。通过资源的制造, 矿物具有抵抗力和意识力。这种抵抗能力与主流的资源观点相矛盾, 从而产生了新见解: 资源是物品、而这些物品并非都能转变为资源。研究认为, 有必要关注开采和采矿法规的复杂力量。本文不仅提供了解决底土无形属性的认识论干预, 而且将当代采掘实践重新想象为对底土的本体论斗争。在这场斗争中, 土著人通过与环境的超物质关系来提出和挑战土地所有权。

Con base en trabajo de campo realizado en Ghana, este artículo examina el modo como las ontologías indígenas del oro, la tierra y los ríos dan forma a las prácticas extractivas. Me apoyo en la ecología política para explicar cómo las propiedades invisibles del subsuelo se trenzan con las realidades sociales. Los entendimientos del subsuelo como mundos más-que-materiales informan en Ghana los rituales, tabúes y otros protocolos. A través de tales protocolos, emergen los caciques, espiritistas y otros personajes como gobernantes del acceso subterráneo. Esta investigación muestra que la soberanía subterránea se extiende más allá del estado para incluir fuerzas invisibles de los paisajes de extracción, planteando retos ontológicos a los procesos neoliberales de adquisición de tierras y privatización del oro. El estudio muestra también que las materias minerales tienen capacidades de resistencia e intencionalidad que se constituyen por medio de la construcción de recursos. Tales capacidades de resistencia contradicen las visiones dominantes sobre los recursos, generando nuevos entendimientos de éstos como cosas que no siempre adquieren entidad. El estudio sugiere la necesidad de prestar atención a las complicadas fuerzas de extracción y a las regulaciones mineras. Tal enfoque no es una simple intervención epistemológica para abordar las propiedades invisibles del subsuelo, sino que provee visiones importantes para reimaginar las prácticas extractivas contemporáneas, como contiendas ontológicas sobre el subsuelo en las que personas indígenas producen y retan los reclamos por la tierra a través de relaciones más-que-materiales con el entorno ambiental.

Palabras clave:

“Gold is a spirit. It has capacities to appear and disappear,” claimed one miner in Odumasi, Ghana. In Ghana, such understandings are common among many miners when describing gold’s agential capacities. For some miners, gold is not a mere resource for exploitation, but a complex substance capable of resistance, reproduction, and interaction. It has capacities to remain hidden from view (i.e., disappear from site and sight) and such understandings often inform taboos, rituals, and other protocols with spirits. Through such protocols, chiefs, spiritualists, “big men,” and others emerge to govern subterranean access. Based on eight months of in-depth ethnographic field work, I examine how indigenous ontologies of gold, land, and rivers shape extractive practices in ways that are coconstituted with authority and mineral access.

In the last two decades, following the 2008 financial crisis, “small-scale” mineral extraction witnessed an unprecedented expansion of capitalist investment. In Ghana, a combination of market instability and subsequent high gold prices, geopolitical relations, neoliberal policies, and local socioecological conditions, including land tenure policies and geology, drive expansion in gold extraction. Numerous Ghanaian and foreign miners, particularly Chinese miners, became involved in gold mining (Crawford and Botchwey Citation2017; Hausermann and Ferring Citation2018). These recent operations, including foreign-controlled operations, are entangled in customary practices that mediate gold access.

In Ghana, dominant understandings link extractive practices to state–capital relations, including how national policies combine with global flows of capital to facilitate mineral exploitation (Hilson and Potter Citation2005), thereby exposing local people to mining vulnerabilities (Hausermann, Adomako, and Robles Citation2020; Adomako and Hausermann Citation2023), and limiting their access to land (Hilson and Garforth Citation2013; Hausermann et al. Citation2018). Recent studies, however, demonstrate that existing local socioecological conditions (Nyame and Blocher Citation2010; Hausermann et al. Citation2018) and people in extractive spaces complicate state–capital interests (Luning and Pijpers Citation2017; Hausermann, Adomako, and Robles Citation2020). For instance, Nyame and Blocher (Citation2010) revealed that cordial and often symbiotic relationships between local miners and traditional authorities are important for organizing informal mining on state-leased concessions for transnational operations. Also, geological understandings of gold deposits at varying depths allow for local extraction on large-scale companies’ concessions (Luning and Pijpers Citation2017).

Many of these studies, however, have examined extractive practices from Western geoscientific understandings of mineral deposits. Indeed, studies have shown that “miners all over the world” understand gold in ways that are radically “different from western geoscientific views” (Peluso Citation2018, 411; see also Nash Citation1993; Taussig Citation2010). Among many Ghanaians, subterranean worlds are more-than-material resources (van de Camp Citation2016; Rosen Citation2020). They are other-than-human domains and “spirit masters” of extractive landscapes (de la Cadena and Blaser Citation2018, 2). Such understandings illuminate other dimensions of the subsoil and allow for a particular kind of extractive practices and power relations that govern subterranean access.

This article draws from political ecology of extraction to consider the agency of matters hidden beneath the surface (Bebbington and Bury Citation2013; Bridge Citation2013). I engage local meanings and practices of the supernatural to address how invisible mattersFootnote1 of the subsoil become entangled with social realities. Spiritualizing the subsoil, I contribute to recent calls for ontologically diverse practices of extraction that mobilize subterranean politics (Murrey Citation2015; Theriault Citation2017). This approach allows for more-than-human practices, taking seriously the agency of spirits and their political capacities in extractive spaces. Rather than the straightforward protocols defined by mining laws, I demonstrate that gold access is negotiated through complex processes that often involve invisible forces in mining spaces. Foreign miners enter Ghana relatively unencumbered through geopolitical relations and development projects (Hausermann, Adomako, and Robles Citation2020), but they must deal with complicated on-the-ground realities of subterranean access. A more-than-human approach also provides insights into the disappearing capacities of minerals, including how absences inform material practices of rituals that enable resources to become. Countering narratives of resources’ becoming, I argue that such disappearing capacities mobilize subterranean politics, generating new understandings of resources as things that do not always become. Rather than viewing gold as inert, waiting for capitalist discovery and exploitation, I illustrate that the metal’s capacity to remain hidden from view is taken seriously.

In what follows, I examine how the subsoil has been constructed and understood in political ecology. Next, I discuss my embodied participation in the field and implications for knowledge production. I then situate Ghana’s gold mining in its current and historical contexts, detailing its spiritual entanglements. I delve into invisible forces as active participants in resource-making, attending to ontologies and meanings of extractive landscapes. I conclude by highlighting the benefits of engaging with ontologically diverse extractive practices in political ecology.

Ontologies in Political Ecology of Extraction

Resource extraction has been central in political-ecological understandings of human–environment interactions. Scholars have engaged with how resource use, control, and access are negotiated (Bury Citation2005; Rolston Citation2013). Others have engaged with how subsoil entities enter, and become transformative of, social life (Perreault Citation2013; Rolston Citation2013).

Political ecology studies on mining have shed light on how subterranean resources have become spaces of capital accumulation (Bebbington and Bury Citation2013; Perreault Citation2013). Scholars have drawn attention to how state power over subterranean matters combines with capitalist accumulation of wealth to facilitate mineral exploitation and commodification, detailing how indigenous people’s lands have been appropriated and transformed into mining spaces (Bury Citation2005; Perreault Citation2013). Bury (Citation2005), for instance, illustrated how Peru’s mining sectors have been integrated into transnational networks of production, transforming land tenure policies, land-use patterns, and livelihood activities. Toxic substances produced from mining also accumulate on indigenous people’s farmlands and in water bodies, thereby removing people’s means of production and reproduction from the public sphere (Perreault Citation2013), and often inciting local contestations and mobilization against mining (Li Citation2015).

Recently, scholars have examined how the agency of nonhuman natures, “constitutive of and constituted within arrangements of substances, technologies, discourses, and practices,” shapes extraction (Perreault Citation2013; Richardson and Weszkalnys Citation2014, 16; Bakker and Bridge Citation2021). In Ghana, geology mediates local and transnational miners’ relations (Luning and Pijpers Citation2017). In the U.S. West, equipment, dirt, rocks, and other material substances mediate corporate-workers’ relationships (Rolston Citation2013). While advocating for the subsoil’s transformative roles, such a focus on material presence of minerals limits the political capacities of unseen matters.Footnote2

Recent scholarship has engaged with the agency of the unseen to address how invisible properties of the subsoil shape social outcomes through their absence. This scholarship emphasizes that resources’ becomingness is constituted through uncertainties that frame their potentialities (Labussière Citation2021; Marston and Himley Citation2021). Kama (Citation2021), for instance, illustrated how oil shale is made public in the “absence of large scale, commercially proven production” (58). Kama’s work is instructive in its insistence on the liveliness of absence, highlighting that although oil shales are not yet resources, they “lure both national politics and speculative capital as an oil economy to come” (58). While acknowledging absence as the subsoil’s specific characteristic, analyses have often ignored native conceptions of what makes resources become absent or present. These silences are more than racial; they are necessarily the articulation of ontological politics that perpetuate colonial presence and violence against other ways of knowing (de la Cadena Citation2010; Sundberg Citation2014). This article details some of the ways through which indigenous perspectives are well-situated to address this oversight.

Indigenous perspectives share similar views on invisible dimensions of the subsoil but emphasize that such particularities might not be revealed through experimental protocols as they do not share epistemic or ontological status with laboratory things (Blaser Citation2014; Gómez-Barris Citation2017). Detailing the difficulties in tracing their presence, de la Cadena (Citation2010) revealed that among some people in the Andes, the apu (a mountain) is not an object of extraction but an “earth-being” who demands offerings and appropriate behavior from the people while caring for them when properly propitiated. Whereas such entities mobilize mining contestations, in Ghana and elsewhere (Nash Citation1993; Taussig Citation2010), they enable extraction.

The turn to indigenous ontologies highlights the reciprocal relations of extractive landscapes while accounting for the force that connects matter to the being of matter. Among indigenous scholars, gold, land, and other biophysical entities are not mere actants in sociopolitical processes, as articulated by most Western scholars (Sundberg Citation2011; McElwee Citation2016), but beings enlivened with spirit, will, and knowing (Watts Citation2013). Watts (Citation2013), for instance, criticized materialists for treating land as dirt and thought as only possessed by humans. Theriault (Citation2017) similarly questioned the naturalization of state forest practices as an efficient way of environmental regulation without attending to invisible forest beings’ transformative roles in land-use practices.

Indeed, recently, scholars called for political ecology to promote “ontological multiplicity” to account for categories cast as “supernatural” or “creatures of human imagination” (Theriault Citation2017, 117; Hausermann Citation2021). Engaging with such perspectives, Theriault (Citation2017) argued that invisible beings “are no less significant in the (de)constitution of state power than many of the more directly observable agencies whose interactions we are accustomed to tracing” (114). Others suggest that “othering” supernatural entities enact universalizing claims that render certain categories illegitimate and (re) produce “colonial ways of knowing and being” (Sundberg Citation2014, 34; see also Blaser Citation2014). Others have also called for the theorization of the geologic in ways that account for the forces of “mute matter in lively bodies: a corporeality that is driven by inhuman forces” (Yusoff Citation2013, 790) while attending to resource ontologies, including how specific resources are known, experienced, and embodied by the people who work with them (Richardson and Weszkalnys Citation2014).

Following these authors, I broaden political ecology work through engagement with the supernatural. I delve into the subsoil without privileging the visible: What lies beneath the surface is hidden and not perceptible to the naked eye. I use the term ontology to mean world-making processes through complex intertwinement of human and more-than-human persons (Theriault Citation2017; Hausermann Citation2021). I use indigenous, local, and native ontologies to mean the articulation of non-Western ways of knowing and being (Blaser Citation2014; Hunt Citation2014). Here, spirits and matter operate as one and not as separate entities. I use the terms local, native, and indigenous interchangeably to mean primordial groups whose territories have become submerged within extractive landscapes. I use these terms in the context of how research participants understood themselves and their relationship with extractive landscapes.

Feminist Ethnographic Methodologies and the Making of Extractive Geographies

Reflexivity has been central in feminist ethnographic research. Pushing against the disembodied objective view from nowhere, scholars have used reflexive accounts to understand how researchers’ values, assumptions, and positionalities are constituted in knowledge production (Sultana Citation2007; Smith Citation2016). Hausermann and Adomako (Citation2021), for instance, illustrated how multiple, intersecting identities, including Whiteness, Blackness, and citizenship, shape knowledge about land-use practices. Researchers’ contradictory roles as insiders and outsiders also intersect with class, gender, and ethnic identities to influence field work experiences (Sultana Citation2007; Smith Citation2016).

Recently, scholars have encouraged researchers to scrutinize their assumptions and categories used to represent the world (Blaser Citation2014; Hunt Citation2014). Scholars have emphasized that researchers’ ontological assumptions, embedded in their training and experiences, shape the way they know and represent the world (Blaser Citation2014; Hunt Citation2014). For Hunt (Citation2014), such assumptions are rooted in (colonial) structures and spaces of knowledge production that shape how indigeneity is known and represented. Sundberg (Citation2014) also argued that when researchers present their ontological categories without positioning or acknowledging voices that articulate similar ontologies, they perpetuate colonial presence and silence other ways of knowing. To confront such ontological violence, some scholars have suggested that researchers must recognize their presence on the field as an engagement with indigenous bodies and territories (Hunt Citation2014; Gergan Citation2015). Others have encouraged researchers to disclose how they come to know and represent indigeneity (Blaser Citation2014) while doing an ethnography that allows for treating researchers’ embodied experiences as primary data (Theriault Citation2017).

Following these authors, I attend to how my multiple identities and ways of knowing, emerging from my being an AkanFootnote3 and training in Anglo-European philosophical tradition, affected the research. In the United States, I have been trained as a geographer, in the human–environment tradition, which emphasizes nonhuman objects as coconstituted in sociopolitical processes. In the geographies I grew up with, social reality is constituted through material and spiritual realms, where the realms of spirit and matter constantly interact in a system of intertwinement (Hausermann and Adomako Citation2021). Such understandings shaped the research questions and data interpretation.

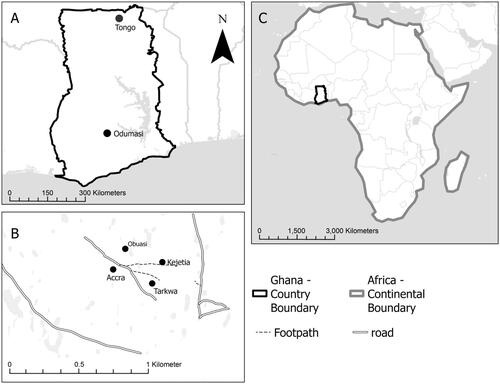

During the research process, the multiple identities I embodied created and broke down barriers, shaping what information people were willing to share. My relative privilege as a Ghanaian woman studying in a top U.S. university gave me easy access to government offices and mining sites. I interviewed government officials at District Assemblies, the Minerals Commission, and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Two communities, comprising Odumasi in southern Ghana and Tongo, including four mining enclaves—Kejetia, Obuasi, Accra, and Tarkwa—in northern Ghana, were selected (). The communities were selected based on mining types. Tongo is predominantly underground, whereas Odumasi is alluvia mining.

Figure 1. Study area’s location. (A) Study locations in Ghana’s context. (B) Mining enclaves in Tongo. (C) Map of Ghana in Africa’s context.

In Tongo, after my initial meeting with the chief, he offered an escort to introduce me to the miners. Although this introduction gave me easy access to the sites, ethnic and language differences became remarkable. It was MikeFootnote4 who helped me to navigate this barrier. Also, the privileges I carried in my body became prominent in people’s development expectations. Although from the Global South, I carried the privileges of Global North researchers. Communities in northern Ghana are home to numerous international and local nongovernmental organizations. People have become accustomed to how these organizations go into the communities to collect data and promise development projects. Many people saw me as an embodiment of privilege with capacities to bring development and themselves as in need of development, whereas others wanted me to convey their intimate concerns to governmental and international bodies.

I belong to the same ethnic group and speak the same language as the people of Odumasi. It would be erroneous to think that such social connections accorded me the privileges of an insider. When I first visited the site, people speculated I was not who I said I was. They often associated me with the state or the media. In Ghana, artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) has largely been constructed as illegal and dangerous in media and political discourses. Many miners feared arrest as state officials frequent mining sites. People often observed my embodied presence as I navigated mining spaces. My position on the field was negotiated through material and symbolic differences, visible in the pen and papers I carried. In Ghana, such materials are linked to the learned, a prestigious position often assigned to high-class educated elites. These materials were a constant reminder of my otherness, making me acknowledge that my nativeness does not mean people will automatically open up to me. I traversed emotional and extractive landscapes to dismantle suspicions and gain trust. Elsewhere (Hausermann and Adomako Citation2021), I detailed how my positionalities, including running with miners from the police and friendship ties, proved valuable.

Despite these ties, some miners were uncomfortable with me taking pictures or recording. Note-taking and observation, instead, became an important part of the research process. While I was observing and documenting mining practices, some miners insisted on reading my notes to make sure what I wrote was consistent with my intentions on the site. Others wanted to check that I wrote exactly what they said, and some wanted me to write down issues they felt needed addressing by the state.

I started the study with preliminary research in Summer 2017. In Summer 2018, I organized a series of meetings with miners, assemblymen, traditional authorities, and state officials. I used purposive sampling to select the communities, traditional authorities, and state officials. I used convenience sampling to recruit miners based on availability and willingness to participate in the study. Between July 2019 and December 2019, I conducted eighty-three interviews with people along intersecting axes of social difference. The interviews recorded on tape were later transcribed. In situations where respondents were uncomfortable with tape recordings, handwritten notes were taken, which I later compared with those of my field assistant, and typed every night.

Informal group discussion also became useful during break time or after work. In Tongo, it was common to find groups of miners resting while chatting under shady trees when there is no work. In Odumasi, miners commonly rest under bamboo trees or walk in groups when they leave work. These sites opened doors for me to recruit and speak with other miners. Spending time with miners under trees and walking with them from mining sites while having informal conversations allowed for intimate perspectives to be shared.

I used inductive and grounded theory approaches (Herbert Citation2010) to analyze the data. Grounded theory attends to emerging concepts rather than providing overarching preexisting themes that obscure empirical details. To compose such an empirically informed theory, I entered the transcribed data into ATLAS.ti software. I coded the data based on what a given part of the text tells. I developed a thematic framework based on emerging themes related to extractive practices, ontologies, and land acquisition processes. I organized and analyzed the concepts and themes that emerged textually.

Postcolonial (Re)Construction of Subterranean Sovereignty, Neoliberal Policies, and Mining

In Ghana, many people know the extractive landscape as a living being. The extractive landscape, although it might be unsettled by humans, is not empty, but occupied by spirits who manifest tangibly in the corporeal as mountains, rivers, and other biophysical entities, even as others remain invisible to the naked eye. There is also a greater awareness that the land and its resource wealth belong to the ancestors who were the first to cultivate relationships with the spirits (d’Avignon Citation2020). Individuals who claim ancestral or biogenetic connections to such posthumous persons have inherent rights to use the land. Extracting the land of its mineral wealth, however, requires permission from the spirits through direct negotiations with the chief and elders who act as custodians of the land. Part of the negotiation process also involves specific rituals and sacrifices that enlist religious authorities to perform mining rites on behalf of miners. Although miners have had a long history of accessing gold-producing lands through sacrificial offerings to spirits and face-to-face negotiations with traditional authorities, postcolonial policies complicated mineral land rights and acquisition.

Instead of ancestral ownership, the 1962 Minerals Act vested all mineral deposits in the state (Nyame and Blocher Citation2010). This declaration was new as it made a clear distinction between surface and subterranean ownership, which ontologically positioned subterranean mineral and surface rights in the state and traditional authorities, respectively, thereby making traditional authorities surface owners instead of subterranean mediators. The declaration also privileged state-authorized mining at the expense of all other land uses, denying individuals legal rights to mine outside state-controlled operations, despite the country’s long history of private indigenous mining (Nyame and Blocher Citation2010). This declaration rendered indigenous spaces invisible, setting the agenda for the appropriation of indigenous territories (Gómez-Barris Citation2017). Yet, private mining persisted as miners continued to negotiate land access via traditional authorities.

In the 1980s, the state liberalized the mining sector to promote large-scale foreign investment. This reform complicated the mineral acquisition process by introducing new mining actors while subcontracting the state’s power to control the subsoil. State regulatory bodies, including the Minerals Commission, were established to grant concession licensing to mining companies. Major policy changes, including eliminating import duties on mining equipment and reducing investment allowances, were also designed to promote foreign investment (Hilson and Potter Citation2005). These policy changes quickly expanded transnational gold exploitation with great impacts on farming, thereby pushing many farmers into ASM (Hilson and Garforth Citation2013). In 1989, small-scale mining was also formalized to create employment for Ghanaian entrepreneurial subjects via licensing schemes (Hilson and Potter Citation2005).

Despite reforms, mineral land acquisition has not gone without obstructions. After the state grants subterranean access, prospective miners must negotiate surface access with traditional authorities. Registered miners are often challenged with the burden of social licensing, particularly when the leased concession is in use by unregistered miners, which often forces mining companies to mine alongside unregistered miners (Luning and Pijpers Citation2017). Nyame and Blocher (Citation2010) highlighted that such operations on state-leased concessions are possible partly because the majority of gold-producing lands spatially fall within customary ownership. When the state declared itself as the ultimate owner of the subsoil, it did not address surface ownership. This loophole has allowed some miners to bypass the state as customary policies make no separation between surface and subsurface ownership. Also, according to neoliberal ideology, the state does not control “the financial-technical-logistical” means of gold production but facilitates the condition for the appropriation and dispossession of gold-producing lands (Emel, Huber, and Makene Citation2011, 73), thereby limiting the state’s sovereignty to the production of legal and proprietary conditions for capital to flow to mining areas. Among many miners, however, such an attempt to control the subsoil through paper contracts is new and means something different. Local miners have historically accessed mining rights from customary authorities through sacrificial offerings to spirits. Also, although neoliberal regimes allow for individuals to enjoy the monopoly of the subsoil as their exclusive property rights to the exclusion of all others (Emel, Huber, and Makene Citation2011), customary lands are not divided into private property to be claimed through paper contracts.

Studies suggest that transnational companies are more likely to access land through the dual system than local miners (Nyame and Blocher Citation2010). Interviews with miners, however, complement reports on the explosive growth of transnational informal mining (Crawford and Botchwey Citation2017; Hausermann and Ferring Citation2018). Estimates speculate that about 85 percent of ASM miners operate outside the legal domain, leading some scholars to describe the sector as ungovernable (Peluso Citation2018). Such discursive-ontological division between “legality” and “illegality” is fluid, though, and fails to capture reality, as some miners move inside and outside state control (Peluso Citation2018).

Odumasi land is a registered large-scale concession operated by Owere Mining Company. The company operates alongside local informal mining despite its exclusive legal status. The ubiquitous nature of informal mining on this concession cannot be overemphasized, making some observers conclude that such activities have become intentionally tolerated by law enforcers. One EPA official articulated this intentional tolerance by remarking, “When we go to the field, we see them, we hear their machines. … By the time you get there, they are already gone.” The official’s statement articulates informal mining’s visibility. In Odumasi, informal mining is visible everywhere in homes, the community, and on major highways. Mining does not take place remotely as miners make public their presence. Stories circulate that some state officials demand regular monetary payments from unregistered miners to continue mining. Although some miners succumb to such demands, they often run to hide in bushes when state officials raid the sites. While on the field one day, one miner shouted, “Scatter, they (police) are here!” Suddenly, everybody started running. I, together with some miners, ran up a mountain. While on the mountain, we saw a group of uniformed men confiscating mining equipment. When I asked for an explanation, one pit owner responded, “It is money they want.” The pit owner received a phone call later, claiming it was one state official who called for negotiations. He disclosed that state officials frequent the site when payments are not forthcoming and concluded that if they demanded an unreasonable amount, he would buy new equipment. In Ghana, such negotiations are common and state officials use such strategies to benefit from unregistered mining.

In Tongo, mining lands are registered as small-scale concessions. Unregistered miners view these lands as communal and not private properties of concessionaires, however. One miner, for instance, explained, “We start digging anywhere … sometimes people make claims when we strike the vein.” While registered and unregistered mining coexist, the involvement of transnational miners in ASM has created tension among groups. Shaanxi Mining (Ghana) Limited’s (henceforth, Shaanxi, a Chinese company in Tongo) operation, by Ghana’s mining laws, is illegal as small-scale operations are a right for only Ghanaians. Some people complained about this state oversight, but it is rumored that Shaanxi makes regular monetary payments to high-ranking government officials to receive protection. Although such protection is nothing new, it illustrates the state’s contradictory role in promoting transnational “illegal” mining while cracking down on local unregistered miners.

In terms of national law, registered concessionaires have exclusive legal rights to gold-producing lands and unregistered miners often lack such status. Yet, unregistered miners benefit greatly from gold-producing lands due to customary relations. In Ghana, informal land acquisition is widely recognized. Some miners acknowledge the state’s legal space to rule, but they continue to regard the spirits as true owners of the subsoil. Miners have become embedded in the local sociopolitical landscape of mining and do not necessarily view the state as giving them permission to mine. Some miners trace ancestral connections to make land claims. As one miner in Odumasi remarked:

We will not let strangers (foreigners) take over our land. It is our ancestral inheritance. We are entitled to take what belongs to us.

Chiefs, Customary Lands, and Mineral Extraction

On 5 October 2022, Ghana’s President, Nana Akufo-Addo, appealed to chiefs to lead the fight against informal mining. While addressing the chiefs, the President stated:

You have been for centuries, the custodians and owners of the lands. … Indeed, 80% of the lands in this country continue to be under your custody. Much of it has been acquired through the blood and sacrifices of your ancestors. The remainder of the 20% which I hold in trust for the people of Ghana, derives from state acquisition from you … ultimately the welfare of the state of the land is our joint responsibility. Although by statute the minerals in the soil belong to the President in trust for the people. (JoyNews Citation2022)

Reference to the ancestors also illustrates how customary lands are entangled with deceased persons of extractive landscapes. As the president indicated, customary lands constitute about 80 percent of Ghana’s land surface, acquired through blood and sacrifices. Traditional authorities hold absolute ownership rights on behalf of their people, but accessing such lands requires permission from chiefs and individuals who hold usufruct rights. In Tongo, the Tindaana, the earth priest (Tindaama, plural), supervises land matters, whereas the chief or family elders disburse lands in Odumasi. This mode of land acquisition is informal, negotiated through face-to-face requests with landowners, and often sealed through symbolic gestures of drinks, offered as libations to spirits or tokens to show gratitude.

Interviews with miners, however, revealed that such tokens are now monetized, negotiated through financial payments or ore-sharing practices. Such practices explain how customary practices complicate profit-making while highlighting how capital articulates with customary authority. In Ghana, other studies report similar findings, highlighting how chiefs use their position to gain financial benefits from miners (Crawford and Botchwey Citation2017). In Tongo and Odumasi, ore-sharing practices and financial payments differ from site to site. On several of the sites, chiefs and landowners had representatives who monitor and record the amount of ore produced daily. Such proceeds are shared weekly in the ratio of 1:1:1 among landowners, miners, and financiers. Like other areas (Verbrugge Citation2015), landowners’ relatives also have the privilege of occupying high-ranking jobs as managers or guards, often in exchange for ore proceeds.

Other sites featured rent-seeking chiefs or landowners who charged GHC 300 (approximately US$59.30Footnote5) weekly per machine, regardless of how much ore is extracted (which can be up to GHC 10,000 [approximately US$1,976.70). With increasing ASM mechanization (Adomako and Hausermann Citation2023), the changfaFootnote6 has become common. There can be as many as twenty changfa on one site. Unlike concessionaires, machine owners do not have exclusive property rights to the land. Working on such lands requires verbal agreements with the chief or landowner. In both communities, some individuals rented land for a fee of GHC 200 (approximately US$39.50) weekly to miners. Other studies report chiefs who engage in outright sale of lands, despite customary prohibitions (Rosen Citation2020). The interviews also revealed chiefs or landowners who acted as financiers, investing in the operational expenses of mining. In most areas, such extractive investments drive ASM expansion (Verbrugge Citation2015; Hausermann et al. Citation2018).

Neoliberal Mining, Big Men, and Land Deals

Ghana’s ASM is largely characterized as poverty-driven (Hilson and Garforth Citation2013). Recent trends, however, also reveal miners who are neither poor nor dispossessed of lands (Hausermann and Ferring Citation2018). In Odumasi, foreigners were absent, but local investors financed machinery and related costs. Such foreign absence was surprising, given the ubiquitous nature of Chinese operations in Ghana. One site owner explained that “the Chinese came but they left because of unfavorable terms of business.” Others highlighted disapproval from landowners who view Chinese operations as ecologically damaging. Besides, all Odumasi land is a registered large-scale concession, although small-scale miners cohabitate with large-scale companies (Luning and Pijpers Citation2017), and often lease out such lands for foreign operations (Rosen Citation2020).

Whereas unfavorable conditions moved transnational capital out of Odumasi, in Tongo, local miners collaborate with foreigners to provide capital for machinery and concession licensing. Such a transnational element, particularly the Chinese, is worth mentioning as it illustrates how transnational capital articulates with local sociopolitical conditions. Scholars trace the Chinese involvement in ASM to China’s 1970s labor deregulation and increasing role as a donor and exporter of workers and equipment related to development projects (Hilson, Hilson, and Adu-Darko Citation2014). In recent decades, Ghana has borrowed billions of dollars from China to construct dams and roads. In connection with such projects, thousands of Chinese workers were imported (Hausermann, Adomako, and Robles Citation2020) and millions migrated later following China’s demand for gold and subsequent high gold prices. Before 2013, an estimated 50,000 miners migrated to Ghana, introducing excavators and other high-tech machinery (Hilson, Hilson, and Adu-Darko Citation2014; ). By 2013, foreign elements in ASM had exploded, gaining widespread media and political attention.

Until recently, foreigners could provide equipment and technical support on small-scale concessions. This arrangement resulted in prolific transnational control of ASM sites. In Tongo, whereas strangers have historically acquired lands through the Tindaama, gold discovery and related land deals have introduced new mining actors in the land tenure arrangements. Some concession holders have collaborated with transnational companies to negotiate gold access through chiefs, instead of the Tindaama. Colonial imposition of chieftaincy in northern Ghana facilitated such arrangements, but many continue to regard the Tindaama as legitimate authority over land matters, thereby creating various controversies among groups. One such controversy surrounds Shaanxi’s operations.

Common narratives about Shaanxi’s arrival in Tongo settle on deceit and lack of transparency. People claimed one concession holder, the owner of Yenyeya Mining Company (henceforth, Ben), brought Shaanxi on account of providing technical support to local miners, but Shaanxi has taken over mining operations in the community. Effectively enclosed from the community, some people claimed nothing about Shaanxi’s operation is small in scale. The company operates on fifty acres of land, employs more than 500 workers, and uses high-tech machinery to access deep deposits. A thirty-five-year-old miner illustrated this by explaining:

A certain man was operating the pit. Ben became the boss after the man left. When the boys [mining team] decided to register the pit, Ben told them to do the registration because he did not have money. When Ben’s brother became an MP [member of Parliament], he took Ben to Accra to do another registration in Ben’s name. Then Ben brought the Chinese. The Chinese made us understand they would help supply equipment … but they took over. They dug new shafts and drilled down. When their shaft met ours, they told us to stop working immediately. We moved to Bantama site and dug a new pit. Only to realize Shaanxi had already chopped [mined] the area. All the pits were in Shaanxi’s.

Historically, miners with financial difficulties have accessed support from local investors who provide capital for food and equipment. The involvement of foreigners in this practice, however, is leading to outright dispossession of mineralized lands. In contradiction to state officials’ claims that transnational ASM investments are outlawed, Shaanxi continues to partner with Yenyeya and Porbortaba Mining Groups, generating accusations of complicity for various groups. Anti-Shaanxi miners accuse Ben of fronting Shaanxi to dispossess the community of gold, and others suspect Ben’s brother’s involvement, claiming his election as an MP and subsequent registration of a concession in Ben’s name and Shaanxi’s arrival are not mere coincidence. Others suspect that high-ranking government officials, including the police and Minerals Commission, are involved in Shaanxi’s land deals, often citing the constant deployment of state police to protect Shaanxi’s interest and intimidate local miners whenever they protest Shaanxi’s operations.

Other narratives suggest that Shaanxi’s partners also deceived the chief of Gbane, a subchief of Tongo, to cede more than 747 acres of land to Shaanxi. The Tindaama petitioned the Tongo traditional council, who blocked the agreement on accounts of fraudulent acquisition and lack of diligent consultation. Shaanxi’s recent move to take over additional concessions has also created tension between the Tindaama and the paramount chief of Tongo. The Tindaama, who view Shaanxi’s land deals as disadvantageous to local miners, recently petitioned the EPA to disregard Shaanxi’s application for a permit under its new name, Earl International Group (GH) Limited. In support of Shaanxi, the chief appealed to the EPA to disregard the concerns of the Tindaama, claiming the company operates on his land.

The findings revealed that transnational mining is introducing new technologies and mining actors while reformulating land policies to dispossess lands. Yet, complex land tenure policies challenge such operations as traditional authorities often refuse to grant lands for transnational operations, thereby complicating neoliberal mining.

Spirited Landscapes, Rituals, and Spiritualists

“There is a river here … it does not want impurity. You cannot go there to mine. People fear they might encounter problems when they disturb it,” claimed one miner in Odumasi. In Ghana, gold mining is not just contractual relations with the state or other human subjects, but also ritual engagements with spirits, contrary to dominant views (Emel, Huber, and Makene Citation2011). Unlike neoliberal processes of mineral land acquisition, miners, through ritualization, enlist the land, rivers, and others in gold production. In local cosmologies, the land is the womb that contains deceased members of the community. Customs mandate that miners seek consent from the land and bodies whose remains are hidden in the land’s womb.

Rivers are also transformative beings whose powers are usually invoked when mining on river-populated lands. Such landscapes are feared to cause problems when offended. To avoid such encounters, custom mandates that miners working close to river bodies seek authorization and propitiate the spirits periodically. Failure to properly propitiate the spirits can present significant challenges to gold production.

For some miners, negotiations with supernatural authorities are as important as human authorities. Such negotiations often involve rituals that require spiritualist interventions. People often articulate the phrase “you need spiritual eyes to enter the spiritual realm,” to emphasize spiritualists’ mediating role in resolving spiritual matters. Like geologists’ calculative capacities, spiritualists often act as intercessors who assist miners to connect with invisible worlds. They perform rituals about land acquisition. The spiritualist often asks prospective miners to present sacrificial items in accordance with demands of the spirits. The intercessor offers these items to the spirits, through sacrifices, on behalf of the miners. In return, the spirits give blessings and protection to miners on conditions of regularly appeasing them and desisting from acts that are deemed detrimental. If the spirits refuse the sacrifice, additional sacrifices are made but continuous rejection is an indication of impending danger. In some cases, extraction can be delayed for weeks or months to make way for rituals.

The spirits also give instructions on taboo observances, including prohibited days of mining. In Odumasi, mining is not allowed on Tuesdays and other sacred days; in Tongo, mining is prohibited on Fridays. A male miner commenting on tragic encounters with spirit beings explained:

We don’t mine on Tuesdays. It is taboo. Tuesdays are rest days for the land. If you go to the site, you may see what you don’t like. … A woman went to farm on Tuesday some years back. She came home narrating her encounter with an airplane-like object falling from the sky. She fell sick and died three days later. … Some remain dumb and fall sick after such encounters.

The spirits can be vengeful when offended. You do not want to experience their wrath. They can punish those who fail to perform rituals. Sometimes, you will be working, and the machine will suddenly stop for no reason. Other times, the machine will not start. Certain rivers get angry for redirecting or blocking their channels. You will be working and suddenly, the water will sweep everybody downstream. Pits can collapse and everybody will die. The spirits can cause your machine to harm you. The attacks will not stop until sacrifices are made.

It is impossible to see the spiritual with your naked eyes. You need spiritual eyes. While I heard stories about aduro in mining, I experienced one when I worked as a chiselman. Each time we went to break the rocks, our master will give us aduro to rub our hands. Other times, he will sprinkle liquid-like substances on the land.

Spiritual transactions are traditionally paid with sacrificial offerings, but people revealed that some spiritualists now demand a percentage of the ore. Originally the role of traditional priests, the incursion of modern practices has also enrolled new intermediaries in gold production. In Ghana, occultic advertisements flourish on billboards along major highways and on radio and television stations, where spiritualists of all faiths promise prosperity. Instead of traditional priests, some miners enlist Islamic ritualists and Christian pastors for ritualistic purposes. Some people told numerous stories of Christian pastors who organize prayer sessions for both local and transnational companies (see also Rosen Citation2020). Such sacrifices are often carried out to replace traditional sacrifices or prevent public outrage, but they are informed by ideas about realities of spirits. Elsewhere, corporate-sponsored animal sacrifices, engaging anthropologists to honor sacred spaces, are common (Murrey Citation2015), suggesting that complex knowledge systems mobilize extractive landscapes.

Gold’s Ontologies and Extractive Practices

I belong to the Akan ethnic group and my ancestors settled around Lake Bosomtwe, Ghana. Growing up, adults told stories that the lake was a deity. People observed customary avoidances to maintain the sacredness of, and relationship with, the lake. Fishing, for instance, was not allowed on Sundays because it was the rest day for the lake. Similar stories about the spiritual nature of gold circulated in Tongo and Odumasi where people were often warned against careless interactions with the metal. Rumors circulated that some people went mad or died mysteriously after careless encounters with the metal. Although my research focus was to understand gendered organization of mining, such rumors led me to explore spiritual ontologies.

One day, while chatting with Ato, a team leader in Odumasi, I asked why women are limited to specific extractive activities. Ato explained that gendered extraction has much to do with sacredness of objects and mining spaces than the activity itself. For Ato and many miners, gold is not a mere object of extraction. People’s understandings of gold go beyond its physical and geological properties. To such miners, gold is a spirit and material substance simultaneously. It has capacities to appear or resist extraction, contrary to dominant views (Richardson and Weszkalnys Citation2014). Underground, some miners indicated that gold can appear physically like a mystical snake or hen-like object. People used such appearances to mean physical manifestation of the gold deity, claiming such gold cannot be extracted because of its supernatural powers. This hen-like gold is not deposited in rocks but moves underground. It rarely appears, and encounters with such metal portend impending doom, warranting ritual sacrifices to continue mining in peace. An underground miner in Odumasi explained:

We all rush to the site upon hearing gold has appeared. Gold moves around. It does not stay in one place. Gold underground can illuminate and dim alternately like light. Gold is a spirit that can appear like a hen with chicks. The hen is the spirit gold and has powers to disappear. You can only touch the gold-bearing rock by pricking your fingers and pouring the blood on it.

Money from [the sale of] gold is spirit. Once you get the money, it will just vanish, or you spend it unnecessarily until you realize everything is gone.

Not all miners accept the affective capacities of gold, however. Here, religion plays an important role in shaping people’s knowledge systems and practices. Although knowledge about the spiritual nature of gold is widespread among people of all faiths—including Catholics, Protestants, and Moslems—for some Pentecostal Christians, gold does not possess any spirit or disappears when reacting with bodily fluids, although they acknowledge people express such ideas. This strand of Christians, though, acknowledges witchcraft powers and other malicious spirits on mining sites. In Ghana, indigenous ontologies and practices continue to shape Christian practices. Instead of blood sacrifices, some Christians sprinkle holy water and anointing oil on mining concessions as purification objects to hasten gold production. Christian miners also emphasize the power of Jesus’s blood and the Holy Spirit as a potent force to increase gold production. Such understandings are in line with local ontologies that present gold as an active, transformative entity capable of resisting extraction and able to be courted to appear.

In Ghana, gold’s disappearing capacities inform material practices of rituals. Such practices, including blood spills, provide miners with extractive capacities while revealing contradictions in gold’s agentic capacities. Thus, although the metal has capacities to remain invisible, rituals and spiritualist interventions can hasten gold production. Like geologists’ calculative practices and laboratory techniques (Marston and Himley Citation2021), these practices are also constituted in the potential supply of gold.

Spiritual Display of Powers and Accusations of Illicit Accumulation

Ghana’s gold field is a site of physical and spiritual contestation, often generated through gold’s absences and presences. In both communities, occultic narratives and accusations proliferate and Christians and Moslems alike are implicated in such accusations. Rumors of occultic practices are gendered and classed, however, following similar narratives in Ghanaian movies, media, and research, on accounts that rituals afford wealth accumulation (Rosen Citation2020). In Ghana, overly rich men are often suspected of using magical means to accumulate wealth. Some miners recount similar stories of powerful male miners who engage supernatural powers to extract gold. Stories of male team members who engage rituals to draw gold from neighboring pits are also common, often generating controversies over pit invasion. While on the field one day, one male team accused another team of using juju to draw gold from their pit. One miner quickly concluded, “That is why you extract more gold daily while we found less.” For some miners, such controversies are a manifestation of spiritual warfare, resolved by engaging supernatural powers to guard against pit invasion.

Others told chilling stories of powerful individuals who engage supernatural forces to extract gold and the life force of less powerful workers. Scholars have linked the workings of such insidious forces to global capital accumulation, wherein people produce immense wealth for the empowerment of others (Rosen Citation2020). In Odumasi, people often cite an incident of pit collapse that killed about sixty male miners. Stories circulate that some miners seeking to be rich overnight spiritually induced the pit to collapse. Similar stories were told in Tongo. On 23 January 2019, Shaanxi blasted an explosive that killed sixteen male miners. A forty-four-year-old son of Tunde (the owner from whose pits the deceased had been working) narrated that the deceased were working in Tunde’s pit in search of gold while Shaanxi blasted the explosive. They (deceased) inhaled excessive poisonous gas and became too weak to pull their bodies to the surface. Community members drew the boys’ bodies from the pit one after the other, but sixteen of them died from suffocation shortly after rescue. Although the proximate cause of death was smoke inhalation, common narratives settled on spiritual attacks. From Tunde’s son’s accounts, the death of the miners infuriated the youth of Tongo and the families of the deceased, who stormed Tunde’s house. Demanding mob justice and holding sticks in the air, the youth chanted war songs while calling for Tunde’s blood to spill the same way the boys’ blood had spilled. Occupants of the house fled for their lives. Properties were vandalized. It took the intervention of the state police and military to calm down the situation. The enraged youth accused Tunde of using the boys for juju because it was in his pit the boys met their untimely demise. In Ghana, such deaths generate anger and accusations as people claim they are spiritually induced to hasten gold production. For some miners, though, such deaths are greatly valued. Tunde’s son narrated how some miners refused to help rescue the boys by continuing to crack rocks under the ground while they watched the boys gasp for breath. Some people described the incident as a sacrifice to bloodthirsty spirits who offer quick money in exchange for blood. Some miners view blood sacrifices as the most potent form of gold attraction, commonly articulated in the statement, “When pits claim lives, we get more gold.”

As pit deaths have become common, so too are occultic accusations. By Tunde’s son’s accounts, Tunde had bought a brand new car, the most expensive in the village, a day before the incident occurred. Tunde’s act of bringing a new car to the village was described as an extravagant display of wealth, a common behavior of “big men” and male miners whenever they “strike big.” Single-handedly, he also covered the bills of all those who went to the hospital for treatment. People claimed they had seen Tunde’s wife and daughters sharing money from a bag full of money intended for people claiming to be victims of the explosion. When the boys began to die one after the other, people quickly linked their deaths to Tunde’s display of wealth in public. Suspecting his involvement in blood money rituals, people quickly accused him of using the boys for juju.

Some people suspect, however, that the disgust toward Tunde was enhanced by jealousy as some natives claim strangers are taking over their ancestral lands. Although a migrant from southern Ghana, Tunde’s multiple statuses—as a concession holder, equipment owner, and a “big man”—have positioned him as a de facto customary authority to contest Yenyeya and Porbortaba Mining Groups’ operations, a company owned by a native of Tongo. In Tongo, people who make ancestral claims to land are natives, whereas all others are strangers or migrants. Gold discovery and concession registration, however, have introduced new powerful actors like Tunde while reformulating the grounds on which land claims are made. Whereas Tongo natives claim ancestral ownership, Ghanaians who are nonnatives draw on citizenship and nationality to make land claims. It is common to hear nonnatives invoking race and nationality to differentiate their operations from foreign operations, often casting them as foreigners or strangers. Whereas claims of ancestral connection differentiate natives from nonnatives, discourses of nationality, which blur such distinction by lumping all Ghanaians as citizens, mobilize contestation against transnational operations.

In Tongo, other concessionaires accused Shaanxi of using sophisticated technologies to invade their pits. Shaanxi’s constant use of explosives was commonly described as ritual murder and a weapon against local miners. Stories circulated that Tunde and Ben originally operated separate pits on one concession until Ben broke away to register a separate concession under the Yenyeya Mining Group. To the displeasure of Tunde, still relying on manual labor, Ben brought in Shaanxi to provide equipment and technical support. Anti-Shaanxi miners claimed, “Shaanxi is everywhere under the ground,” invading almost all concessions. In direct retaliation, Tunde and other mining groups sunk tunnels to connect their pits with Shaanxi’s, allowing for easy movement from one pit to another. A thirty-five-year-old male miner who claimed to be Ben’s former worker explained that they invade Shaanxi’s side of the concession by offering a percentage to Shaanxi’s security personnel. Again, attention to verticality of mineral deposits is important. Bridge (Citation2013) argued that verticality “induces problem of access,” “affording additional means of control” (55–56). Although physically enclosed, vertical holes have enabled local miners’ invasion into Shaanxi’s space as the underground is often viewed as a “no man’s land” where the fittest survive. Yet, navigating such holes has been the cause of many deaths (Adomako and Hausermann Citation2023).

Following the miners’ deaths, a local group called the Concerned Citizens of Tallensi organized a protest, accusing Shaanxi of causing tension among community members. The group petitioned the state to revoke the license of Shaanxi on grounds of illegal use of explosives to kill miners. Citing numerous deaths recorded in the community since the company’s operation, the group immediately secured a court injunction to suspend Shaanxi’s activities. People whose views align closely with the group speculated that Shaanxi and partners deployed occultic powers to attack the boys. Stressing the importance of blood spills in gold production, people cited the “careless” and constant use of explosives as a deliberate attempt to spill blood. One miner stressed, “They know the more blood they spill, the more gold they will get.” Shaanxi, on the contrary, alleged miners had been trespassing on the company’s concession by using neighboring pits to steal gold. Following court action, Shaanxi’s workers took to the streets of Tongo protesting the government’s decision to revoke Shaanxi’s license and called for the arrest and prosecution of Tunde. Protesters carried placards with various inscriptions—“Stop the galamsey [ASM] ritual murder now” and “Protect genuine foreign investors.”

Many others describe the boys’ deaths as eventualities of occultic practices, blaming the miners themselves for their demise. With abounding rumors about spiritual attacks, some people claim some miners have turned to spiritualists for protection against such attacks. People with this perspective speculated that some of the boys went to a ritualist for protection, suspecting others might attack them mysteriously. Failing to honor the conditions of the rituals, the ritualist’s deities took their lives as a sacrifice. Others concluded that the boys’ continual failure to properly propitiate the spirits for the spiritual services rendered caused their demise. Many others used the slogan “quick money, quick death,” to describe the boys’ deaths as eventualities of illicit accumulation. People believe the outcome of quick wealth through magical means is always tragic and untimely where the spirits constantly make unreasonable sacrificial demands until one can no longer meet them. Stories circulated about houses that have become unhabitable as the ghosts of the bodies used for such rituals hunt the house. Others told stories of people who suddenly went mad after engaging in blood money rituals. Houses and cars suddenly burned to ashes for no apparent reason. Wealth, accumulated through blood money rituals, is widely condemned and stigmatized as violent and unethical, commonly inflicted with sudden loss of wealth, untimely death, and mysterious illness. In Ghana, such accusations are based on suspicions, flourishing on material presence of gold, the death of miners, or both. Successful gold producers are often accused of extracting gold and human vitalities through invisible forces. Such suspicions and rumors illuminate other processes through which materialities of “others” become appropriated, but they also incite violence against successful gold producers, thereby illuminating how embodied subjectivities, power, and inequalities are produced and exercised.

Conclusion

The last two decades have witnessed an explosive growth of mining in Ghana. Although the state formalized mining to attract local and foreign investments, the “formalization” process did not account for the role of invisible forces. Rather than the straightforward process defined in mining laws, this study has demonstrated that Ghana’s gold mining is entangled in customary practices that complicate neoliberal processes of land acquisition and gold privatization. In Ghana, getting access to gold is not as smooth as what is normally crafted in mining laws. Gold access is negotiated through complex processes with spirits, chiefs, and others who present ontological challenges to neoliberal extraction. Chiefs, for instance, could refuse to cede land for mining, and spirits can reject sacrifices or delay extraction to make way for rituals. These findings support claims that the state–capital subject is just another actor in a web of relational networks with other actors working to control the subsoil (Bridge Citation2014; Gergan Citation2015).

Relatedly, the study has highlighted the subsoil’s agency in resource becoming. Rather than viewing matters of the subsoil as passive, waiting for capitalists’ assembling from below the ground, miners in Ghana do not downplay the energetic capacities of subterranean matters in resource making. Gold, for instance, is not just dragged from underground to the surface, but flows of energy to and from the metal are taken seriously. Gold can resist extraction by becoming absent, raising questions about resources’ becoming. Despite acknowledging such temporalities and potentialities (Kama Citation2021; Labussière Citation2021), there is a lack of scholarship on native conception of resources’ absences or presences. This research suggests the need to rethink such temporalities as resources do not always become. In Ghana, resources’ becomingness is not always through material processes of resource making (Kama Citation2021), but also through embodied ritual sacrifices to spirits.

As scholars explore the link between bodies and territories (Adomako and Hausermann Citation2023), spiritual ontologies, particularly claims of ancestry, in relation to how bodies become geologic materials and subsequent extraction of their personhoods (Yusoff Citation2018), can deepen understandings of subterranean sovereignty and the Anthropocene. Although there have been important engagements with invisible environments, analyses have largely focused on geologic becoming of the human (Yusoff Citation2013) or resource becoming of mineral matters (Kama Citation2021), ignoring the thing or force that makes humans or minerals become. In Ghana, deceased members of extractive landscapes whose remains have ecologically become are active participants in resource making, and through interactions with such bodies, indigenous people have produced the extractive landscape in ways that require spiritual and social licensing before mining begins. This research suggests the need to engage with such ontologies as the becoming of resources is intimately tied to the invisible forces of mining landscapes.

Finally, the study highlights that ontologically diverse practices render the subsoil knowable and extractable and that political ecologists can benefit greatly by engaging with the multiplicity of forces that shape extraction. In Ghana, human subjects work closely with spirits to make resources. With notable exceptions (Nash Citation1993; Taussig Citation2010), such spiritual intertwinements have received relatively little attention. Whereas political ecologists have shed light on multiple practices of extraction, spiritual practices have remained on the margin. Even where there has been important engagement with spirits (Li Citation2015), analyses have remained limited to material practices. This research demonstrates that ritual practices are also embodied material practices that provide miners with extractive capacities. The article suggests the need to further explore spiritual dimensions of human relationships to extractive landscapes as resource struggles are more-than-material practices.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Dr. Heidi Hausermann and Dr. Pamela McElwee for their comments and guidance. I also thank Joseph Oduro Appiah, Zoey Walder-Hoge, and the three anonymous reviewers for their generous comments and all Ghanaians who contributed to this research. This research was supported by Rutgers Human Ecology Department, Geography Department, Center for African Studies, and Graduate School.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Janet Adomako

JANET ADOMAKO is an Assistant Professor in the Departments of Geography and Environmental Studies and Sciences at Bucknell University, Lewisburg, PA 17837. E-mail: [email protected]. She uses ethnographic methods to study gender, resource ontologies, and health vulnerabilities in small-scale mining.

Notes

1 These are entities whose presences or absences are not perceptible to the naked eye.

2 These are objects with qualities that are not evident or present.

3 This is the largest ethnic group in southern Ghana.

4 A high school teacher and research assistant who helped with translation and notetaking. I used pseudonyms to represent Mike and research participants to ensure anonymity.

5 This conversion was made while doing field work in 2019.

6 This is a Chinese-made machine for crushing rocks.

7 Here, this is a destructive force induced through rituals in exchange of money or power.

References

- Adomako, J., and H. Hausermann. 2023. Gendered landscapes and health implications in Ghana’s artisanal and small-scale gold mining industry. Journal of Rural Studies 97:385–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.12.028.

- Bakker, K., and G. Bridge. 2021. Material worlds redux: Mobilizing materiality within critical resource geography. In The Routledge handbook of critical resource geography, ed. M. Himley, E. Havice, and G. Valdivia, 43–56. London and New York: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780429434136.

- Bebbington, A., and J. Bury. 2013. Political ecologies of the subsoil. In Subterranean struggles: New dynamics of mining, oil, and gas in Latin America, ed. A. Bebbington and J. Bury,1–25. Austin: University of Texas Press. doi: 10.7560/748620.

- Blaser, M. 2014. Ontology and indigeneity: On the political ontology of heterogeneous assemblages. Cultural Geographies 21 (1):49–58. doi: 10.1177/1474474012462534.

- Bridge, G. 2013. The territory now in 3D! Political Geography 34:55–57. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2013.01.005.

- Bridge, G. 2014. Resource geographies II: The resource–state nexus. Progress in Human Geography 38 (1):118–30. doi: 10.1177/0309132513493379.

- Bury, J. 2005. Mining mountains: Neoliberalism, land tenure, livelihoods, and the new Peruvian mining industry in Cajamarca. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 37 (2):221–39. doi: 10.1068/a371.

- Crawford, G., and G. Botchwey. 2017. Conflict, collusion and corruption in small-scale gold mining: Chinese miners and the state in Ghana. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 55 (4):444–70. doi: 10.1080/14662043.2017.1283479.

- d’Avignon, R. 2020. Spirited geobodies: Producing subterranean property in nineteenth-century Bambuk, West Africa. Technology and Culture 61 (2):20–48. https:// doi: 10.1353/tech.2020.0069.

- De la Cadena, M. 2010. Indigenous cosmopolitics in the Andes: Conceptual reflections beyond “politics.” Cultural Anthropology 25 (2):334–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1360.2010.01061.x.

- De la Cadena, M., and M. Blaser. 2018. Introduction: Pluriverse proposals for a world of many worlds. In A world of many worlds, ed. M. De la Cadena and M. Blaser, 1–22. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Emel, J., M. T. Huber, and M. H. Makene. 2011. Extracting sovereignty: Capital, territory, and gold mining in Tanzania. Political Geography 30 (2):70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2010.12.007.

- Gergan, M. D. 2015. Animating the sacred, sentient and spiritual in post‐humanist and material geographies. Geography Compass 9 (5):262–75. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12210.

- Gómez-Barris, M. 2017. The extractive zone: Social ecologies and decolonial perspectives. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Hausermann, H. 2021. Spirit hospitals and “concern with herbs”: A political ecology of healing and being-in-common in Ghana. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 4 (4):1313–29. doi: 10.1177/2514848619893915.

- Hausermann, H., and J. Adomako. 2021. Positionality, “the field,” and implications for knowledge production and research ethics in land change science. Journal of Land Use Science 17 (1):211–25. doi: 10.1080/1747423X.2021.2015000.

- Hausermann, H., J. Adomako, and M. Robles. 2020. Fried eggs and all-women gangs: The geopolitics of Chinese gold mining in Ghana, bodily vulnerability, and resistance. Human Geography 13 (1):60–73. doi: 10.1177/1942778620910900.

- Hausermann, H., and D. Ferring. 2018. Unpacking land grabs: Subjects, performances and the state in Ghana’s “small‐scale” gold mining sector. Development and Change 49 (4):1010–33. doi: 10.1111/dech.12402.

- Hausermann, H., D. Ferring, B. Atosona, G. Mentz, R. Amankwah, A. Chang, K. Hartfield, E. Effah, G. Y. Asuamah, C. Mansell, et al. 2018. Land-grabbing, land-use transformation and social differentiation: Deconstructing “small-scale” in Ghana’s recent gold rush. World Development 108:103–14. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.03.014.

- Herbert, S. 2010. A taut rubber band: Theory and empirics in qualitative geographic research. In The Sage handbook of qualitative geography, ed. D. DeLyser, S. Herbert, S. Aitken, M. Crang, and L. McDowell, 117–20. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Sage.

- Hilson, G., and C. Garforth. 2013. “Everyone now is concentrating on the mining”: Drivers and implications of rural economic transition in the eastern region of Ghana. Journal of Development Studies 49 (3):348–64. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2012.713469.

- Hilson, G., A. Hilson, and E. Adu-Darko. 2014. Chinese participation in Ghana’s informal gold mining economy: Drivers, implications and clarifications. Journal of Rural Studies 34:292–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.03.001.

- Hilson, G., and C. Potter. 2005. Structural adjustment and subsistence industry: Artisanal gold mining in Ghana. Development and Change 36 (1):103–31. doi: 10.1111/j.0012-155X.2005.00404.x.

- Hunt, S. 2014. Ontologies of indigeneity: The politics of embodying a concept. Cultural Geographies 21 (1):27–32. doi: 10.1177/1474474013500226.

- JoyNews. 2022. #NoToGamsey: President Akufo-Addo meets with National House of Chiefs at Manhyia Palace – News desk. JoyNews, October 5. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uk9o6q_MXEg&ab_channel=JoyNews.

- Kama, K. 2021. Temporalities of (un) making a resource: Oil shales between presence and absence. In The Routledge handbook of critical resource geography, ed. M. Himley, E. Havice, and G. Valdivia, 57–67. London and New York: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780429434136.

- Labussière, O. 2021. A coalbed methane “stratum” for a low-carbon future: A critical inquiry from the Lorraine Basin (France). Political Geography 85:102328. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102328.

- Li, F. 2015. Unearthing conflict: Corporate mining, activism and expertise in Peru. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. doi: 10.1515/9780822375869.

- Luning, S., and R. J. Pijpers. 2017. Governing access to gold in Ghana: In-depth geopolitics on mining concessions. Africa 87 (4):758–79. doi: 10.1017/S0001972017000353.

- Marston, A., and M. Himley. 2021. Earth politics: Territory and the subterranean—Introduction to the special issue. Political Geography 88:102407. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2021.102407.

- McElwee, P. D. 2016. Forests are gold: Trees, people, and environmental rule in Vietnam. Seattle: University of Washington Press. doi: 10.20495/seas.6.2_390.

- Mohammed-Nurudee, M. 2022. “We don’t want any mining activities on our land”—Mampong Traditional Council insists. JoyNews, November 27. https://www.myjoyonline.com/we-dont-want-any-mining-activities-on-our-land-mampong-traditional-council-insists/.

- Murrey, A. 2015. Invisible power, visible dispossession: The witchcraft of a subterranean pipeline. Political Geography 47:64–76. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2015.04.004.

- Nash, J. C. 1993. We eat the mines and the mines eat us: Dependency and exploitation in Bolivian tin mines. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Nyame, F. K., and J. Blocher. 2010. Influence of land tenure practices on artisanal mining activity in Ghana. Resources Policy 35 (1):47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2009.11.001.

- Peluso, N. L. 2018. Entangled territories in small-scale gold mining frontiers: Labor practices, property, and secrets in Indonesian gold country. World Development 101:400–16. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.11.003.

- Perreault, T. 2013. Dispossession by accumulation? Mining, water and the nature of enclosure on the Bolivian Altiplano. Antipode 45 (5):1050–69. doi: 10.1111/anti.12005.

- Richardson, T., and G. Weszkalnys. 2014. Introduction: Resource materialities. Anthropological Quarterly 87 (1):5–30. doi: 10.1353/anq.2014.0007.

- Rolston, J. S. 2013. The politics of pits and the materiality of mine labor: Making natural resources in the American West. American Anthropologist 115 (4):582–94. doi: 10.1111/aman.12050.

- Rosen, L. C. 2020. Fires of gold: Law, spirit, and sacrificial labor in Ghana. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Sarpong, S. 2017. Sweat and blood: Deific interventions in ASM in Ghana. Journal of Asian and African Studies 52 (3):346–62. doi: 10.1177/0021909615587366.

- Smith, S. 2016. Intimacy and angst in the field. Gender, Place & Culture 23 (1):134–46. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2014.958067.

- Sultana, F. 2007. Reflexivity, positionality and participatory ethics: Negotiating fieldwork dilemmas in international research. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 6 (3):374–85.

- Sundberg, J. 2011. Diabolic caminos in the desert and cat fights on the Rio: A posthumanist political ecology of boundary enforcement in the United States–Mexico borderlands. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 101 (2):318–36. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2010.538323.

- Sundberg, J. 2014. Decolonizing posthumanist geographies. Cultural Geographies 21 (1):33–47. doi: 10.1177/1474474013486067.

- Taussig, M. T. 2010. The devil and commodity fetishism in South America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Theriault, N. 2017. A forest of dreams: Ontological multiplicity and the fantasies of environmental government in the Philippines. Political Geography 58:114–27. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2015.09.004.

- van de Camp, E. 2016. Artisanal gold mining in Kejetia (Tongo, northern Ghana): A three-dimensional perspective. Third World Thematics 1 (2):267–83. doi: 10.1080/23802014.2016.1229132.

- Verbrugge, B. 2015. The economic logic of persistent informality: Artisanal and small‐scale mining in the southern Philippines. Development and Change 46 (5):1023–46. doi: 10.1111/dech.12189.

- Watts, V. 2013. Indigenous place-thought and agency amongst humans and non humans (First Woman and Sky Woman go on a European world tour!). Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 2 (1):20–34.

- Yusoff, K. 2013. Geologic life: Prehistory, climate, futures in the Anthropocene. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 31 (5):779–95. doi: 10.1068/d11512.

- Yusoff, K. 2018. A billion black Anthropocenes or none. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.