Abstract

We argue for a radical reconfiguration of existing theorizations of the “lively commodity”—beings captured, cultivated, and traded for their very lives—on more inclusive terms. Specifically, we advocate the inclusion of animals intended for dietary consumption, in recognition of the demonstrable centrality of encounters between human beings in their role as consumers and the animals and animal parts offered for sale in Hong Kong’s many wet markets to the processes of commodification. Based on semistructured interviews with vendors and consumers (n = 86) and a variety of modes of ethnographic observation (including narrative, photography, and several forms of videography), we analyze three groups of practices and strategies for structuring and negotiating productive encounters (which we label provoking motion, stimulating appetite, and maintaining life) observed in twenty-seven different wet markets across Hong Kong between June and September 2022. Our analysis also suggests critical issues and directions for future research rooted in, at minimum, crucial differences in the scalar, temporal, ecological, and ethical dimensions of diverse processes of lively commodification.

我们主张彻底重建更具包容性的“活物商品”(被捕获、培育和交易的活物)理论。应当考虑用于食材的动物;在香港生鲜市场中, 作为消费者的人类和出售的动物及其部位相互接触, 应当认识到这种接触在商品化过程中显著的中心地位。基于对供应商和消费者的半结构化采访(n = 86)和各种民族志考察方式(叙事、摄影和各类视频), 对2022年6月至9月香港27个生鲜市场进行了考察, 分析了构建和协商有效接触的三组实践和策略: 激发行为、刺激食欲和维持生命。针对活物商品化过程中尺度、时间、生态和伦理上的差异, 我们的分析还提出了未来研究的关键问题和方向。

Abogamos por una radical reconfiguración de las teorías existentes sobre la “mercadería viva” –seres capturados, cultivados y comercializados por sus propias vidas– en términos más inclusivos. Específicamente, nuestra pretensión busca la inclusión de los animales destinados al consumo alimenticio, en reconocimiento de la centralidad demostrable de los encuentros entre seres humanos en sus roles de consumidores, y los animales y partes de animales ofrecidos en venta en los numerosos mercados húmedos de Hong Kong, para los procesos de mercantilización. A partir de entrevistas semiestructuradas con vendedores y consumidores (n = 86) y una variedad de modos de observación etnográfica (que incluyen la narrativa, fotografía y varias formas de videografía), analizamos tres grupos de prácticas y estrategias para estructurar y negociar encuentros productivos (que nosotros etiquetamos como provocadores de movimiento, estimulantes del apetito y mantenedores de la vida)) observados en veintisiete diferentes mercados húmedos de todo Hong Kong, entre junio y septiembre de 2022. Nuestro análisis sugiere también aspectos y orientaciones críticas para investigaciones futuras arraigadas, por lo menos, en diferencias cruciales en las dimensiones escalares, temporales, ecológicas y éticas de los diversos procesos de mercantilización animada.

Hong Kong’s many wet markets provide fresh and affordable produce for millions of people every day, and also play a range of other roles in the city’s communities. They are the “heart” of the neighborhood (Cheung Citation2020) and a “habitual part of daily life” in Hong Kong (Bougoure and Lee Citation2009, 71). Wet markets influence urban development and provide spaces of social inclusion (Marinelli Citation2018), while also meeting a basic consumer demand for fresh food. Hong Kong residents consume an average of 54 g of fresh fish and 308 g of fresh vegetables every day, figures considerably higher than U.S. daily averages of 19 g of fish (including both fresh and frozen) and 210 g of vegetables (Cheung Citation2020). With some eighty major wet markets currently in operation across nearly every corner of the city, the trade in live and frozen seafoodFootnote1 also has an enormous and virtually incalculable ecological footprint. Behind even seemingly minor regulatory changes or fluctuations in the supply of or demand for specific products lurk a host of substantial social and environmental implications that can be especially difficult to predict.

The ability of wet markets to cultivate an atmosphere and promise of freshness is key to their success (Zhong, Crang, and Zeng Citation2020). As Robbins (2012) reminded, “Freshness isn’t natural. It is instead a product of capitalist transport, production, and processing” (231). Freshness of animals and animal parts meant for dietary consumption—often indexed by how recently they were alive or how “lively” they appear to be—is highly valued, and the demand for fresh produce has so far enabled wet markets to outcompete the city’s many supermarkets for particular items (Goldman, Krider, and Ramaswami Citation1999). Especially since the emergence of COVID-19, China’s wet markets have been under intensified scrutiny, so it is a suitable time for a more in-depth examination of their operations. Intensifying competition from supermarkets, threats from developers, and controversies around disease transmission (including COVID-19, SARS, and avian flu), among other factors, threaten their ongoing survival (Chan Citation2023).

There is a long history of competition between wet markets and supermarkets in Hong Kong, mainland China, and across Asia (Goldman, Krider, and Ramaswami Citation1999; Bougoure and Lee Citation2009; Mele, Ng, and Chim Citation2015). Whereas supermarkets struggle to meet consumer demand for freshness, wet markets have a reputation for poor service quality, unsanitary conditions, and—at least in certain quarters—inhumane treatment of animals (Goldman, Krider, and Ramaswami Citation1999; Bougoure and Lee Citation2009). Debates regarding the origins of COVID-19 have only made the “imperial knowledge” of safety standards and quality assurance regulations promoted by supermarkets (Freidberg Citation2007, 322) and the local knowledge often implicitly associated with wet markets harder to reconcile. Vendors use certain strategies to communicate quality and freshness of their products, and to attempt to sell inferior products at inflated prices. Consumers respond with a suite of skills and local forms of knowledge to select quality products and maximize value for money.

Taking the commodification of animals as live seafood products as a point of entry, this article explores the spaces and moments of encounter between vendors, consumers, and animals in Hong Kong’s wet markets. Drawing on recent work developing the concept of the “lively commodity” (Haraway Citation2008; Collard and Dempsey Citation2013; Collard Citation2014), we examine how local knowledges, practices, and strategies produce complex entanglements of value on competing terms through negotiations and other interactions that extend across temporalities measured in seconds to those that extend beyond lifetimes. In contrast to theorizations and analyses that sever companion, laboring, and other animals from those intended for dietary consumption (e.g., Collard and Dempsey Citation2013), we advance a more inclusive theory of the lively commodity. Through an analysis of three sets of practices and strategies extensively documented through field work involving vendors and consumers in twenty-seven different Hong Kong wet markets and other related spaces in 2022, we group these practices and strategies under the headings of provoking motion, stimulating appetite, and maintaining life. We argue that their elaboration strongly suggests an analytical and empirical imperative to extend investigations of the commodification of liveliness beyond the boundaries of collaboration and companionship.

The article proceeds through four remaining sections. First, we review recent literature on lively commodities, focusing especially on the connections between this concept and broader entanglements of the human and nonhuman world as well as competing understandings of value at work in different analyses. In the third section, we briefly elaborate the methodological approach of the larger project of which this article forms a part, including specific methods of data collection and analysis. We then present a summary analysis of the three sets of practices and strategies noted earlier as observed in Hong Kong’s contemporary wet markets, drawing on several distinct forms of observational and interview data. In the concluding section, we indicate just some of the possibilities for an expanded research agenda for the study of lively commodities within and beyond geography, which we argue is already an extant necessity.

Figuring Freshness and Flesh

Recent decades have seen an explosion of interest in nonhuman animals among geographers, especially in their many and varied relationships with human beings (Buller Citation2014; Hovorka Citation2017; Gibbs Citation2020). Concomitantly, a bevy of new concepts, methodologies, theoretical and philosophical perspectives, and political commitments have taken shape across the social sciences and humanities, developments by which geographical research has both contributed and benefited. The agency of nonhuman entities has been debated extensively, especially in dialogue with such thinkers as Donna Haraway, Bruno Latour, Elizabeth Povinelli, Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Sarah Whatmore, and others. Taken together, these debates and advances have highlighted the complex entanglements of the socionatures that exist at the intersection of the human and nonhuman. As Whatmore (Citation2002), Povinelli (Citation2016), Yusoff (Citation2018), and others have argued, demarcations of the living–nonliving, human–nonhuman are a foundational kind of politics of aesthetics (see also Rancière Citation2010; Gerlofs Citation2021). On these foundations of rationality—which things are alive or not alive, what it means to be alive or not alive, who gets to decide these questions, and why, and so on—social practices and political economies are established, reproduced, and challenged. It is now beyond question that these negotiations, contestations, and constructions produce inestimably consequential ecological implications as well. The specters of climate change—although the violences of its uneven manifestations make this an increasingly tenuous descriptor—mass extinctions, and enormous losses of biodiversity the extent of which we are only beginning to understand all underscore the significance of this nexus for our continuing ability to live on this, our deeply “damaged planet” (Tsing et al. Citation2017).

In a world dominated by capitalist social relations, human–animal interactions are overwhelmingly determined—in an enormous variety of ways—by the commodity form and by processes of commodification. Much of the contemporary work devoted to understanding these dynamics is undertaken according to classical or more contemporary principles of political ecology (e.g., Robbins 2012; Bridge, McCarthy, and Perreault Citation2015), especially in establishing a critical relationship with global capitalism and the particular formations that inhere in various geographical contexts. In some such investigations, nonhuman animals have been approached as a kind of “natural resource” that can be “harvested” for various kinds of consumption (e.g., Cronon Citation1991; St. Martin Citation2005; Wilson Citation2015). Others have examined the commodification or capture of animal labor, including what Barua (Citation2018) labeled the “metabolic” form of “animal work” (e.g., Barua Citation2018; Shell Citation2019) and that which Parreñas (Citation2012) called “affective work” (the provocation of specific feelings and experiences through encounter).

Animals have also been shown to factor in the value circuits of contemporary capitalism in numerous other ways. Examples include the production of “wild” experiences like safaris and hunts (Schroeder Citation2018), medical and product testing, ecological preservation or the performance of such, and other spaces of staged and largely passive encounter such as zoological parks, variously marketed as education or entertainment. Ontological and epistemological questions of value abound in the complex human–nonhuman relationships examined in this work, as do competing explanations as to how it is understood, pursued, and realized in each of these many different forms of interaction and the sociospatial conditions within which they are navigated. Where some see quasi-natural “alliance” of mutual advantage or “collaborative” mutual training in specific human–nonhuman relationships (e.g., Power Citation2012; Shell Citation2019), others see crude exploitation, inhumane behavior, 1or the rapacious despoiling of the natural world.

Responding in part to a lack of analytical clarity regarding the production of specifically capitalist value in these relationships, Collard and Dempsey (Citation2013, 2684) built on Haraway’s (Citation2008) theorizations of “lively capital” in proposing the “lively commodity.” In doing so, they “do not mean dead commodities derived from living things (for instance, agricultural commodities like meats, fruits, vegetables, and grains) but, rather, live commodities whose capitalist value is derived from their status as living beings” (Collard and Dempsey Citation2013, 2684). These and other researchers (e.g., Barua Citation2016a) have produced a growing body of work that examines various processes by which the circulation of value is realized through the attribution of life to animals in specific ways. Whether as companions, coworkers, or entertainers, lively commodities from monkeys and parrots to tigers and killer whales are captured, raised, groomed, trained, and otherwise transformed by the perverse alchemy of markets black, white, and gray to signal or produce a wide variety of use values built around differing notions of “liveliness.”

In each case, however, the value of a lively commodity abides in dialectical contradiction. Living beings resist embodying the use values they are ascribed—good for snuggling, beautiful to watch swim around a tank, able to carry large loads of raw materials or sniff out drugs, explosives, or bed bugs, and so on—both consciously and otherwise. They age, they injure, they become ill. They forget their training, try to escape, or become unpredictable or even violent. They require care and management beyond their purchasers’ expectations. Their use values also vacillate as with their movement along bipolar axes (e.g., too wild or tame, too young or old, too intelligent or not intelligent enough) in ways that can be difficult to manage.

Consumers and their preferences and capacities can also be rather capricious, whether at the scale of the individual consumer of a massive python who failed to appreciate the costs of its ownership to that of the citizenry of the member states of international trade agreements that govern the sale and transportation of live animals. To function as lively commodities, animals must therefore be maintained in states of suspension between any number of extremes that themselves are likely to shift throughout (and beyond) the life course of a given animal (Gillespie Citation2021; Bersaglio and Margulies Citation2022). Viewed through traditional categories of value theory, they must be presentable as sufficiently lively to convince a potential consumer of the quality of their use values while also commanding prices that allow their vendors to realize acceptable quantities of exchange value.

Crucial to the negotiation and realization of this value are the moments, spaces, and modes of encounter between human beings in their role as consumers and the animals whose liveliness is for sale (Barua Citation2016a; Ni’am, Koot, and Jongerden Citation2021). Such encounters play an indispensable role in the “active demonstrations of being full of life” through which liveliness is appreciated (Collard Citation2014, 153). As Collard and Dempsey (Citation2013, 2684–85) explained, “encounterability”—the capacity to be “seen and touched in the flesh”—is itself produced through processes of commodification. Vendors and their upstream partners work to produce specific kinds of encounters and distinct forms of encounterability in a variety of ways across different processes of commodification and the different agents and spaces of consumption pertaining to each.

The functional roles of those who curate these encounters have been interpreted in many competing ways. From something akin to the role of Ross’s (Citation2008) elite athletes or other spectacular performers—“an extremely gifted group of workers who go through the motions of labor all day,” using their abilities not “to materially transform something into something else but, rather, to merely perform these actions for the sake of performing them” (988, italics in original)—to something more like the role that factory management plays in Wright’s (Citation2006) comparative analysis of women in manufacturing or practitioners of agriculture or husbandry (cf. Barua Citation2016a). To better understand the unique role of the encounter, Haraway (Citation2008), Barua (Citation2016b), and others have challenged traditional Marxian binaries of use and exchange value through the idea of “encounter value.” For these authors, encounter value represents a distinct form of value generation, enrolling a complex and shifting set of “relationships among a motley array of living beings, in which commerce and consciousness, evolution and bioengineering, and ethics and utilities are all in play” (Haraway Citation2008, 46).

Much remains to be understood about the complex entanglements of liveliness and commodification, however. Tensions persist around how the laboring bodies of nonhuman animals are to be treated in theory and in practice, a question that meets with uneven political and scholastic appetites across contemporary global geographies and often even produces contradictory impulses within one person. Emergent theorizations of lively commodities offer a productive conceptual language, but thus far have focused nearly exclusively on human–animal relationships wherein nonhuman animals are forced into the role of “beast of burden” (e.g., performing specific work tasks at the direction of humans that would otherwise be done by humans or human-directed machines), “preserve” (e.g., for exhibition in a menagerie), or “companion” (e.g., as an exotic pet). Conspicuously neglected in these debates are explorations of nonhuman animals captured and cultivated for sale and consumption as food for human beings or for other nonhuman animals (e.g., pets, game, or livestock), which arguably represent some of the oldest, most persistent, most globally pervasive, and most taken-for-granted forms of lively commodification.

As we demonstrate through an investigation of the commodification of live seafood products in Hong Kong’s wet markets in the sections to follow, training a focus on nonhuman animals marketed for dietary consumption shows lively commodities in distinct relief, enrolling and producing motivations, attitudes, practices, and relationships meaningfully distinct from those examined by existing research, concomitantly encouraging new theorizations. By fundamentally altering the parameters of the situation of encounter, live seafood transactions (or potential transactions) therefore present a radical challenge to the conclusions of previous conceptions of the lively commodity. Although never entirely reducible to the crude pursuit of exchange value, vendors and consumers find themselves actively negotiating value in ways that enroll scientific, folk, and other forms of knowledge, often implicitly or obliquely. Such exchanges define, perform, arbitrate, and mete out life and death in encounters that can last mere seconds,Footnote2 and coalesce into routinized forms of practice, embodied knowledge, and unevenly distributed (and closely guarded) forms of localized common sense. In these encounters, a kind of value proposition is made by vendors, who use specific techniques and strategies to signal maximal use values to their clients, which they hope to parlay into maximal exchange values for themselves. Consumers come in search not of a warm body to cuddle or performer to put on display but rather for the physical, emotional, spiritual, and other forms of vitality they believe will come from consuming animal flesh.

The goal of consumers, in the main, is to identify and realize maximal value in these transactions, often by weighing cost against one expression or another of “freshness.” As Friedberg (2010) showed, freshness is no trivial thing in places where the consumption of fish is a quotidian part of life (e.g., Hong Kong), but rather is considered a vital and essential quality. As we demonstrate in the sections that follow, freshness and other determinative qualities are performed, challenged, and otherwise negotiated in practically infinite variations of practices. Although these practices unfold unevenly across extremely diverse and overlapping time scales, the definitive negotiation of the value of any lively commodity is typically limited to the moment and space of encounter.

Methods

A primary goal of our research has been to investigate the role that liveliness plays in the commodification of seafood products (animals and animal parts) in Hong Kong’s wet markets, prompted by the categorical exclusion of animals bound for dietary consumption in so much of the emergent literature on this topic. To better understand the processes of commodification, we adopted dynamic modes of ethnographic observation and conducted semistructured interviews at a geographically diverse selection of the city’s wet markets (twenty-seven in total) as well as two wholesale seafood markets located across all four of Hong Kong’s major regions—Hong Kong Island, Kowloon, the New Territories, and Lantau Island—between June and September 2022.

Overall, we conducted eighty-six interviews, featuring some forty-six vendors and forty consumers. Among other themes, vendors were asked questions regarding which products they sold live, how they maintained the quality of live seafood, the costs and benefits of selling live (rather than frozen) seafood, and the techniques and equipment required to keep their animals alive. Consumers were asked questions about their purchasing and consumption habits, the qualities they look for when purchasing live seafood and the tactics they use to discern them, and whether and why it was important to them to buy live seafood and to do so in wet markets as opposed to other places. Most interviewees were recruited on site at wet markets, but a smaller group of ten consumers were later recruited online via social media and interviewed over the phone.Footnote3 All interviews were conducted in Cantonese, and later translated and transcribed into English. These data were subsequently grouped and analyzed thematically by members of the research team, with special attention paid to both unique responses and insights and general patterns or consistencies among responses.

We supplemented our interview data with a wide range of systematic but dynamic modes of ethnographic observation adopted during field work sessions that far exceeded the time spent conducting interviews. Observations conducted by members of the research team were written in narrative form as field notes after each site visit, and a variety of cameras and related equipment were strategically deployed with the permission of vendors in many of the wet markets we visited. Some thirty waterproof action cameras were placed inside tanks containing live animals and were also used to capture unique footage of various transactions and transformations that would have been difficult to appreciate otherwise (e.g., being scooped out of a tank with live prawns, weighed, and wrapped in plastic after sale). Mirrorless and DSLR cameras equipped with specialized video and audio enhancements (e.g., remote microphones placed in display areas among live animals) were used to capture many hours of transactions and quotidian behaviors among consenting and cooperating vendors and consumers, as well as footage of live animals on display, being handled or processed, and being selected, inspected, and sold (some of the images and videos included in this article might be disturbing to viewers). We also captured hundreds of still images of facilities, animals, and environments. Members of the research team later reviewed this material in both individual and collective sessions, making further observations and grouping both visual materials and observations for thematic analysis alongside our interview data.

The acts of capturing and analyzing film and other audiovisual materials are not objective nor neutral, and the presence of cameras and other devices can and does alter research encounters (Clement Citation2019). During field work we noticed vendors and wholesalers appearing to handle animals with added care, and to modify their behavior in other ways while we were filming. Even so, we found video (and especially the accompanying audio) provided an especially rich and often unsettling observational experience beyond what narrative or still photography can convey, and thus an essential component of our methodological repertoire. Analyzing video footage collectively was also richly rewarding, as members of our team often reacted to and interpreted footage quite differently based on experiential, disciplinary, linguistic, and other differences.

This methodology allowed us to distill a host of practices and strategies into three major groups, which we present in the following section. We argue that when considered collectively, these compellingly demonstrate the significance of the encounter to everyday negotiations of value in the live seafood trade, and thus the necessity of a more inclusive theorization of the lively commodity.

Lively Commodification and Hong Kong’s Wet Markets

Provoking Motion

Among both vendors and consumers, motion of nearly any kind is generally treated as a significant indicator of both the liveliness and freshness of live seafood. Movement is suggestive of life and vigor and considered a primary index of value. Animals or animal parts that look less “alive” are widely assumed to be less delicious, and possibly even unsafe for consumption. Consumers were quick to offer such beliefs in interviews, often with a strong sense of certitude buffeted by a belief in their own discernment. Ms. Poon (personal communication, 17 August 2022), for instance, told us, “Fish that aren’t energetic taste fishy. … And it is easy to suffer from stomach pain after eating shellfish that aren’t fresh.” Similar arguments abound in wet markets, as in the following comments enthusiastically offered by Jackey Cheung (personal communication, 23 July 2022): “You can’t eat dead crabs! They are very mushy! They should be thrown away! This is the same for lobsters and shrimps!”

In response, vendors have developed a wide variety of practices and strategies to ensure customers perceive their products as active (and therefore safe and high in quality) in the moment of encounter. In some cases, movement is an attribute that need only be displayed as part of the commodification process, as some species of animals will move about readily with minimal or no effort required on the part of vendors. Storing fish in cold water, for instance, is a common general strategy for keeping fish moving. In most cases, however, vendors believe that motion must be provoked. The temporal dimensions of this belief and its associated knowledges and practices are critical, as it is only necessary that a given animal or animal part demonstrate motion within the space and moment of encounter, and provocations that exceed this mandate often pose significant risks and costs. A widespread practice among vendors, for instance, is the removal of one or more fish from a display tank to a plate, box, or table in the open air, as the asphyxiation they experience will induce them to “bounce” and “flop” in a predictably futile attempt to survive (see Video 1). Although practices vary somewhat, most vendors iterate this practice by replacing the performing fish roughly every fifteen minutes, as this is considered the optimum window for expressing motion without completely asphyxiating a given animal.

Space, too, plays a key role in such practices. Hong Kong’s fabled density and perennially overheated land market ensure a steady pressure on the use of even the smallest of spaces, a reality that is often expressed in overcrowded display and storage tanks. Some vendors whose tanks do not leave enough room for fish to swim thus find performative asphyxiation to be their only option for demonstrating liveliness (Anonymous, personal communication, 22 June 2022). As Mr. Leung (personal communication, 27 July 2022) explained, this technique is particularly important for species that tend to be more sedentary, such as the common brown-marbled grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus; see ): “Customers want groupers that move! But let me tell you, groupers live in the cracks of rocks and corals. … They always choose to remain static but not dynamic … I pick one and throw it on the plate to let it bounce. … Now customers know that it is lively!” The animal’s instinctual resistance to its impending death is offered as proof of abundant, safe, and delicious life.

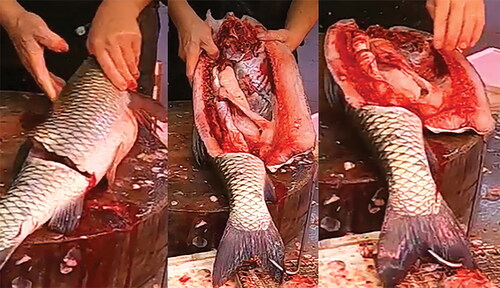

For some species, death is not only threatened or simulated but inalterably initiated so that an animal’s protracted expiration might provoke its most spectacular forms of movement. Vendors commonly chop animals into segments even before they are sold, enabling the severed body parts to perform a kind of involuntary dance on a horizontal or vertical display surface. The heads of some eels, for example, continue to writhe long after decapitation, reportedly due to their high oxygen efficiency, which allows them to function for a long period on the oxygenated blood left in their heads (Verheijen and Flight Citation2008). Eels’ gills are also close to their heads, which allows oxygen to continue to diffuse into their heads so long as their gills remain moist (Verheijen and Flight Citation2008). We recorded many encounters with still-moving, dismembered seafood in our field notes, as in the following excerpt:

Fish heads trying to breathe. Half an eel flapping around on a stainless steel tray with its mouth open. Fish arrayed on trays still twitching with sections of flesh cut off the tops of their bodies. A vendor cut a large fish in half length-wise and poked its still-beating heart with his finger. No questions asked, these fish are fresh! (22 June 2022, Pei Ho Street Market)

Vendors use strategies to enhance the movement of shellfish as well. Many vendors group abalones onto plates and sell them as “plate bundles” to avoid the inconvenience of having to weigh them to determine the price. Within fish tanks, the flesh of abalones would move due to the exposure to water and oxygen, and such movement persists for a short period even after abalones are scooped out and placed onto plates. Their movement on the plates tends to diminish over time due to the lack of water and oxygen, however. Therefore, it is common practice for vendors to put abalones back into the tank and scoop out a fresh set roughly every fifteen minutes (Anonymous, personal communication, 13 August 2022), to ensure that the flesh of the abalones stays in near-constant motion.

In other cases, vendors would “poke” or “brush” the muscular surfaces of shellfish to encourage movement (see Video 3). Many such tactics are species-specific or have species-specific variations. One vendor told us he will knock on the shells of scallops, as well as using his palms to “brush over” the meat of razor clams to trigger their nerves, causing their muscles to contract (Anonymous, personal communication, 13 August 2022). Another reported that he demonstrates the liveliness of tied-up Chinese mitten crabs to potential customers by making their eyes pop up:

The claws and legs of crabs are tied up completely, so it’s hard to see if their claws and legs moved. However, we can still knock them a little bit, to see if their eyes pop out. There isn’t much reaction if you hit the back of their shells, but if you hit the area behind their eyes, their eyes will pop up. They look different! (Anonymous, personal communication, 13 August 2022)

Even the liveliest animals tend to diminish in this capacity over time, and ultimately to die. When decline becomes obvious, vendors adopt a variety of tactics to conceal, deemphasize, or reframe this reality, and in some cases to compensate for it by making concessions in price. Rather than using terms like “dying” to describe fish that are relatively immobile or otherwise appear physically unwell, for instance, vendors prefer to describe such animals as “sleepy,” sometimes even suggesting that they might “wake up” very soon. A vendor we interviewed at Yau Ma Tei Market (Anonymous, personal communication, 28 July 2022) made this perfectly clear: “This is just a word game. Fishes are like humans, they sleep, but they just don’t wake up eventually like humans do.” As animals with limited mobility are quite difficult to sell, some vendors will immediately slaughter and fillet fish that are in obvious decline into smaller parts, rather than continuing to try to sell such “lifeless” fish whole (Mr. Lai, personal communication, 22 June 2022). This strategy is something of a trick, as vendors believe that even discerning consumers will cease to be suspicious of the freshness and quality of a fish that has been sacrificed in this way, instead imagining that the fish had just been selected for apportioned sale by a previous customer (and thus was a “choice” animal).

More straightforwardly, some vendors will offer a discount—even as much as 50 percent—for fish with specific deficiencies (e.g., fish that have begun to swim upside down, a tactic we took to calling “the upside-down discount” in the course of our research).Footnote4 For their part, consumers recognize the asymmetry of information they face in such transactions, and the uneven landscapes of scrupulousness built thereupon. Summarizing common skepticism, one consumer explained their approach to buying live crabs:

You can still eat crabs when they are in the process of dying. But after they have died for one to two hours, there would be bacteria. If vendors say, “Oh, the crab just died,” don’t believe them! You don’t know if it’s real! If a crab just died moments ago, it should still be able to move, but it would move slowly. That’s really a crab that has just died. If the crab doesn’t move at all, don’t even take it for free, because it would just waste your money on gas bills for cooking. … If you know that a vendor is honest, you should just go back to that stall. Lots of vendors assume that you know nothing about seafood, so they would lie to you. (Jackey Cheung, personal communication, 23 July 2022)

Stimulating Appetite

Much as with other lively commodities, animals must also demonstrate their liveliness with specific qualities—and avoid the demonstration of others—to be desirable in the moment of encounter with consumers. Issues of feeding, transportation, preparation, and display often take center stage in these dramas. A common and likely accurate belief among vendors is that consumers will find it distasteful to be confronted with the food—in whatever state of digestion it might be found—of the animals they themselves intend to eat. If fish are fed before or during their time on display, they are more likely to “vomit” or defecate. When fish are slaughtered and apportioned for sale on site or later prepared for consumption, their dismemberment could likewise reveal the partially digested contents of their digestive tracts. Thus, fish are commonly deprived of food by vendors to keep consumers from losing their appetites, as Mr. Leung explained (personal communication, 27 July 2022): “Oh, we cannot feed them, like, they will vomit after eating when they move. … So we will just starve them.” Perhaps as a preemptive response to critique of this starvation practice, several vendors we spoke with quickly shifted the blame to wholesalers: “We buy it from wholesale market, it’s not our responsibility to feed them” (Anonymous, personal communication, 28 July 2022); “Nah, we wouldn’t feed the fish. … It’s the work of the fish farm, we will not feed them during selling” (Anonymous, personal communication, 28 July 2022).

Although verification of such claims is currently beyond the reach of this stage of our research, we note here that some vendors argue that fish farms and wholesalers follow similar practices themselves, as in Mr. Leung’s contention (personal communication, 27 July 2022) that fish farms “will starve the fish for around two days before selling in the wholesale market.” Vendors are also often quick to point out that the animals they sell are perfectly capable of surviving starvation for certain periods. Pampus chinensis (Chinese silver pomfret) and Cheilodactylus zonatus (spottedtail morwong) can reportedly remain alive for up to three days in a tank without food, and some Epinephelinae (groupers) can survive up to four days in similar conditions. As one vendor explained to us, it is no problem for their fish to be deprived of food for up to seven days, as they “will just get thinner … it’s like a human” (Anonymous, personal communication, 28 July 2022). The assumed or observed resilience of animals—which remain demonstrably lively despite a lack of food—and the differentiated responsibilities ascribed upstream allow retail vendors to protect the appetites of their potential customers by preventing distasteful encounters.

Vendors and consumers are also keenly aware that encountering lively commodities is a multisensorial experience, and vendors make great efforts to curate the environs within which these encounters take place. Tactics for effective display are especially important in this regard. To stop the accumulation of foam and unsightly air bubbles on the surface of display tanks, vendors will commonly float a small piece of fried tofu (a “tofu puff”) on top, which is thought to keep the water clear (see ).Footnote5 Whereas some vendors place their fish in large, crowded tanks, others prefer to orchestrate their displays more carefully, even placing smaller vessels inside tanks to highlight particular qualities, arguing, for example, that “fish look better on small plates” (Anonymous, personal communication, 13 August 2022; see also ). Colors are also considered especially important, as was explained to us at the Ap Lei Chau Market (Anonymous, personal communication, 13 July 2022): “Shells look clearer in white light, while fish look shinier in yellow light.” Lighting, we were told, is an especially significant concern for vendors interested in making their products appear beautiful, lively, and delicious.

Figure 3. Yellow tofu puff on the top right corner of the lobster container on the left, 13 August 2022. Photo by K. Y. N. Poon.

Figure 4. “Fish look better on small plates,” Tung Yick Market, 13 August 2022. Photo by C. T. Y. Tsang.

Encounters are never purely visual, however. To the unfamiliar visitor, olfactory sensations can be the most immediate (and, anecdotally, the most discouraging). Even regular customers, however, are often acutely aware of minute differences in odors in the spaces of encounter. Understanding this, vendors take steps to ensure that their environments and their offerings produce only those odors that convey life and freshness. Air circulation is considered a must, both for this reason and in compliance with official regulations from Hong Kong’s Food and Environmental Hygiene Department, which governs most aspects of the city’s wet markets. Fans large and small abound in most markets, as do small air conditioning units and large climate-control infrastructures meant to both minimize olfactory and other discomforts.

When animals die, they are typically placed on ice immediately to delay the onset of unpleasant odors for as long as possible (Anonymous, personal communication, 6 September 2022). A cacophonous array of auditory inputs also fills these spaces during their operating hours: Cleavers and large knives chop though flesh of varying densities; scales are raked from skin with zealous, performative efficiency; and prices and offers are shouted and mumbled, commingling with all manner of requests, critiques, negotiations, banter, gossip, warnings, enticements, and instructions for cooking and eating. Hong Kong’s wet markets are themselves incredibly lively spaces, which any vendor will tell you is no accident. Also common were other physical and emotional responses to such taken-for-granted processes, as the following encounter recorded at the Yau Ma Tei Market demonstrates:

I watch a vendor take a fish out of the Styrofoam container, holding it softly between gloved hands. She places it down on the chopping board with one hand and with the other strikes its head hard with the blunt edge of a cleaver. The fish flaps so violently she must press it down on the chopping board and I can hear the loud slapping noise of its tail hitting the wood. She then cuts it up for sale and puts it into a plastic bag. (Field notes, 28 July 2022)

Figure 5. A vendor’s finger digs deep into a fish to create bloody freshness, Smithfield Wet Market, 15 July 2022. Photo by B. L. Iaquinto.

As with other elements of the encounter, though, there is an inescapable temporality to the meanings attached to animal blood: “… if the dissected fish is put above the ice for around one or two hours, blood will clot, and it is ugly” (Anonymous, personal communication, 28 July 2022). Consumers like Ms. Ho (personal communication, 19 August 2022) shared similar sentiments, explaining that she “may not choose those with clotted blood.”

When blood begins to look stale, viscous, or coagulated, some vendors will rinse the affected segments with water and cover them with a fresh gloss of blood from a more recently killed animal, a practice we witnessed on several occasions. As an experienced vendor explained, “People think blood implies freshness, so we will just add blood on [a fish], such that customers believe [the] dissected fish is fresh as well” (Anonymous, personal communication, 28 July 2022). After a purchase, however, visible blood quickly degenerates into an undesirable quality symbolizing unsanitary food among consumers (personal communication, 15 July 2022). Dissected parts, with or without organs attached, are thus wrapped in blue or transparent plastic bags before being quickly wrapped again in red ones that mask what blood might remain (see ; see also Video 4).

Figure 6. Blue, clear, and red plastic bags, Ap Lei Chau Market, 13 July 2022. Photo by B. L. Iaquinto.

In these and countless other ways, vendors work to ensure that encounters with their lively commodities—in this most crucial stage of their journey from tank to table—are productively piquant. Importantly, folk understandings of life and death create openings in the process of commodification, producing encounters quite distinct from those examined in the transformation of other lively commodities like exotic pets (whose inclusion in the commodity circuit is considered to stop at death; e.g., for Collard and Dempsey Citation2013). The bioeconomic circuit of lively commodification for dietary consumption relies on an encounterability that transcends the living, the soon-to-be-dead, and the once-living, wherein liveliness nevertheless remains ultimately determinative.

Maintaining Life

Even as vendors, consumers, and an array of nonhuman animals struggle to negotiate the boundaries of the contingent continuum of life–nonlife—at least until a productive encounter can be realized—vendors concomitantly strive to keep their captives firmly on the side of the living. In the ever-present competition between shiny new supermarkets and their noisy, shabby, wet market counterparts, an abundance of live offerings still gives the latter a definite edge. Although there are numerous important exceptions, many Hongkongers prefer to purchase their seafood and other fresh foods in wet markets, and many of these prefer to purchase live animals.Footnote6 Anecdotally, we were even told by vendors that their frozen stock was of higher quality, and that the costs were lower and profits higher in the sale of frozen rather than live seafood.Footnote7 “But for Cantonese,” as many vendors and consumers alike will readily argue, “they prefer the lively ones, and they will assess their liveliness” (Anonymous, personal communication, 4 August 2022). One vendor reasoned, “If all seafood were sold frozen, of course people would buy frozen food. But if there’s a choice between live seafood and dead seafood, of course people would purchase live seafood,” importantly also noting, “Hongkongers only visit stalls with seafood that are swimming” (Anonymous, personal communication, 13 August 2022).

Even to those who intend to purchase frozen seafood, we were told, the presence of live animals remains a crucial signifier and the major draw of the wet market. Aside from those practices already discussed, vendors adopt many additional strategies to prolong the lives of their lively commodities. Quite unlike their efforts to produce encounters with particular qualities (e.g., active motion or bloody freshness), however, those we group under the heading of “maintaining life” employ only the dispassionate arithmetic of the shopkeeper’s ledger. That is, these practices are more precisely aimed at staving off death than they are about preserving any particular sort of life.

Striking a balance between minimal investment of resources and maximal return at the point of sale generally results in a low bar for the quality of life afforded to presale animals in the wet market. During our research, vendors routinely remarked, in one way or another, that “there isn’t anything special” about the measures required to maintain the life of their stock (Anonymous, personal communication, 13 August 2022). With a wave of the hand or lilt of the head, many told us that it’s “just … the temperature!” (Anonymous, personal communication, 13 June 2022) that needs occasional adjustment, and that only basic equipment and infrastructure (e.g., “just air conditioners, air pumps, and water,” Anonymous, personal communication, 3 August 2022) are necessary. “I just pay attention to the water temperature and saltiness” (Anonymous, personal communication, 13 August 2022), one vendor explained casually, and another responded to our questions about care and maintenance by flatly stating, “We just don’t really have to manage the fish tanks except cleaning the glass” (Anonymous, personal communication, 6 September 2022). Positioning a fish close to a human being might be rhetorically useful when explaining the former’s tolerance for prolonged starvation, but vendors are typically quick to differentiate between obedience to necessity and wasteful naivete in the care of presale animals more generally. As Elaine (personal communication, 13 August 2022) concluded, one should only aim to keep them alive, to “maintain their lifespan, but not their quality.”

Among other factors, seasonality plays an important role in the life span of live seafood products. Elaine (personal communication, 13 August, 2022) explained to us that live seafood have different “optimal” seasons for consumption: “if the weather is cold, shellfish become fat, and if the weather is hot, shellfish become slim.” Like most other vendors, Elaine uses her own experience and knowledgeFootnote8 to manage her offerings throughout the year. Overall, there seems to be a consensus that the quality of live seafood is at its lowest point during the summer in Hong Kong, as the hot temperatures facilitate bacterial growth and cause easy spoiling. Transportation and storage in warm seasons can compound these problems, as one vendor elaborated: “It is easier for products to die in the truck compared to wet markets due to the absence of air-conditioning. … And products also survive better during the winter as the weather is already cold. During summer, the water temperature is harder to maintain” (Anonymous, personal communication, 22 June 2022).

A “bare minimum” approach to the well-being of live seafood is generally understood to extend upstream as well, with effects that can sometimes frustrate the efforts of retail vendors. As we ourselves observed and as we were told by vendors, animals are generally handled and transported with little care between harvesting and final sale. They often arrive in Hong Kong’s wholesale and retail markets via truck, a process that involves a good deal of violence and “spillage” produced by rough handling and poor travel conditions. As vendor To Gor explained:

Some fishes arrive at the store with their tummies flipped as they may have experienced motion sickness in the delivery truck. Like, the fishes have gone through a long journey prior to arriving at the store. They have left their original location for about ten to twenty hours. So, there definitely will be dead fishes. (personal communication, 6 September 2022)

Vendor Choi Yau Yau (personal communication, 13 August 2022) has resorted to selling their signature product—Mugil cephalus (flathead mullets)—frozen, having experienced the reality that “fishes will collide with each other and develop bruises” if they are transported alive, which “customers can easily notice.” Some consumers note, however, that this lack of care is typically carried on even after animals arrive at wet markets, as in Mr. Yip’s (personal communication, 19 August, 2022) account of watching shrimp and venus clams being thrown carelessly into tanks from high up in the air (causing them to develop bruises and cracks in their shells). Overcrowding (see ), poor sanitation practices, and other issues are common and widely accepted.

Vendors and consumers alike tend to be unsentimental about such practices and their impacts on the animals concerned. Vendor To Gor offered an insightful comparison as part of the rationale for this approach:

Well, we aren’t even keeping the fishes as pets. … We are just selling them. … We will just see when the fishes are about to die. … They die about three days after arriving at the [market]. It’s just a short time period. … This is different from Ocean Park [an amusement park with aquariums in Hong Kong], where the fishes are displayed for public viewing, and there are specialists to help enhance the well-being and attractiveness of fishes. We, vendors, just hope to sell all products as soon as possible. So, we don’t really pay attention in maintaining the well-being of seafood. (personal communication, 6 September 2022)

The temporal dimensions of the commodification process are also quite different from those associated with many other kinds of lively commodities. Whereas companion animals and other lively commodities must remain encounterable long after they are sold, live seafood products need only be so until the moment their final transaction is realized. Although this distinction has been treated by many analysts as sufficient grounds to bracket such animals off from the conceptual domain of the lively commodity, we insist that the demonstrable centrality of the encounter to their commodification and the negotiation and realization of their value be taken more seriously, irrespective of the generally brief duration of such encounters in practice. The liveliness of the lobster is no less important than that of the puppy, only differently so.

Coda: Counting Calories

Although the future of Hong Kong’s wet markets is uncertain, they remain central to everyday life even despite negative associations with the COVID-19 pandemic, an uncertain regulatory environment, and growing pressure from supermarkets and other retailers widely considered more “modern.” Many Hongkongers depend on wet markets as an affordable source of food, employment, or both. and their closure or diminution could exacerbate issues as diverse as food insecurity, unemployment, and gentrification. In satisfying daily nutritional requirements for a major share of the city’s nearly 8 million residents, these spaces also serve as crucial junctions of a political economy with incredibly dynamic scalar dimensionality and, concomitantly, uneven and shifting gravity. Buyers and sellers unconsciously conspire across information asymmetries at the intersection of knowledge, self-interest, and technology to transform nature into commodities valorized because of their liveliness. We have argued that encounters between consumers and animals—and therefore the encounterability of the latter—are demonstrably necessary to the process of lively commodification. That is, these are productive encounters (see Haraway Citation2008).

Given this imperative, we see no compelling reason to segregate such beings from others trafficked, transformed, and traded for such purposes as entertainment, collaboration, and companionship. We offer the foregoing analysis as only a very modest indication of the promise of the more inclusive theorization of the lively commodity we advocate. Gathering these processes of transformation and the bodies they enroll under a single conceptual umbrella, however, should not suggest a universal internal consistency. Rather, the inclusion of animals traded live for dietary consumption forces a reconsideration of the diversity of processes of lively commodification anchored in the encounter. In the case of the wet markets of contemporary Hong Kong, the practices and strategies we have organized under the headings provoking motion, stimulating appetite, and maintaining life suggest several theoretical insights as well as new directions for future research, which we briefly highlight in this conclusion.

The first and most obvious implication of an expanded theorization of lively commodification is scalar; accounting for even some of the animals traded as food necessarily enlarges the spatiotemporal, political-economic, and ecological dimensions of this analytical and empirical landscape. Such large industries and populations (e.g., fishing and fish raising) generate large material effects in the world, which might require different kinds of analysis to be more fully appreciated. A visit to any of Hong Kong’s wet markets at virtually any time on any day should make this enormity immediately and inescapably obvious, from the mountains of Styrofoam and plastic containers piled high on the streets each day, and the labor, machines, vehicles, infrastructures, and other resources enrolled in the near-constant frenzy of deliveries of live animals to the unseen investments of energy, space, and time required to assemble even a single operating stall.

Even small shifts in regulation, regional climate, consumer preferences, or countless other factors with some bearing on this industry might generate substantial consequences. For example, if the current ratio of fresh to frozen fish should change even slightly overall across the city’s wet markets—say, in pursuit of the larger margins on the latter anecdotally reported by vendors—we would expect major changes in the aggregate use of labor, materials, energy, space, and time, to say nothing of the myriad effects each and all these changes might imply within and beyond Hong Kong. The continuing relevance of the encounter with liveliness to the commodification of fish, then, is no trivial affair, despite the often idiosyncratic, tacit, and peculiar expressions of its most potent factors (e.g., folk knowledges, practices, preferences, beliefs, and experiences) and the ways in which these are learned, reproduced, and challenged in everyday life.

The commodification of liveliness examined here is also governed by temporalities that differ markedly from those analyzed in previous research. Unlike pets and performers, animals traded to be eaten typically do not need to remain encounterable beyond the final point of sale. Most often, the time of individual encounters is also extremely brief compared with those of other lively commodities, as consumers tend to choose their live seafood products very quickly in our experience (often these encounters are measured in mere seconds). This brevity, however, does little to diminish the significance of the encounter, as the elaborate practices and strategies examined here clearly illustrate. This suggests that any number of differences even beyond the intentions of the ultimate consumer of any lively commodity (e.g., in the material qualities of animals and their environments, cultural norms and practices, or regulatory contexts) could exert pressure on the dimensions of the encounter. Encounters with lively commodities represent concentrations of productive effort expended over far longer periods of time, often in many iterations. When a consumer selects which fish to eat for dinner, the collective value of this work is often negotiated and realized in the space of a single, incredibly consequential minute. Any theory of lively commodities, then, should account for the differentiated temporalities of commodification and their likely distinct implications.

Vendors and consumers operate on the understanding that the lively commodities traded in Hong Kong’s wet markets will ultimately be killed and will consequently have relatively short lives. As noted earlier, this is commonly referenced as justification for their treatment, along with any number of other arguments and assumptions, many of which are highly localized. We were routinely told that beyond keeping them verifiably alive, fish need not be cared for because they will not be around long enough, or because they will just be killed and eaten, or because they do not have emotions or intelligence, or because they do not feel pain, or, summarily, because they are not human. In many cases such perspectives are offered with placid nonchalance, although some interactions included moments of seeming slippage in such logics, as when vendors quickly shift the responsibility for feeding fish upstream. Such attitudes and the practices and regulation they inform are indicative of another underappreciated dimension of lively commodification, what we might call differential ethics (cf. Yam Citation2022).

Certainly, it is widely understood that contextual distinctions (e.g., geography, history, culture, political economy) structure attitudes and practices concerning which animals are eaten by humans and how the latter treat the former. Aside from such spatiotemporal variation, however, we insist that the limits of lively commodification are likewise determined by a host of differences rooted in, at minimum the nature of animals (e.g., kind, appearance, supposed or observed qualities and features); the conditions of encounter and exchange (e.g., time of day/month/year, location, weather and climate, regulation); prospective clientele (e.g., prevailing cultural norms, local and regional politics, identities and meanings attached to places/groups/activities, expectations for regulatory compliance, access to information, tastes and preferences); and the prospective use values of the commodities concerned (e.g., cuddling, performing tasks, providing delicious caloric sustenance).

Beyond any consideration for the welfare of the animals involved, buying seafood at a traditional, local wet market has its own ethical dimensions as well, especially in an era of profound uncertainty in postcolonial Hong Kong. For many, it simply represents a time-tested strategy for survival or responsible wealth management—a primary indicator of morality for many—as shopping at local wet markets is widely thought to be cheaper than shopping at supermarkets. For others, it holds special cultural, spiritual, or political purchase. The forces that attract locals to wet markets and the knowledge that governs the ethical standards practiced therein are themselves always in flux, however, an exemplary reality that must inform the ethical dimensions of lively commodification more generally.

The specter of COVID-19 and the larger geopolitical cleavages it has further revealed and exacerbated continue to place enormous pressure on questions of animal treatment, making differential ethics in this arena a substantially more complex and difficult prospect than it might otherwise be. The origin of COVID-19 remains a divisive issue in Hong Kong (and elsewhere) and a highly sensitive one. The use or consumption of animals in religious or spiritual practices as well as non-Western medicine is also a continuing source of tension on multiple fronts. Nationality and (maritime) territory also appear to be playing an increasingly important but also increasingly obscure role in the regulation and official discussion of seafood in the region.Footnote9 These and many other pressing considerations militate against facile or rigid normative analyses even while the transnational nature of so much contemporary seafood production necessitates such work. Future work on lively commodities must therefore also seek to contend with the currents below and beyond the shallows of the market where retailer vendors and consumers conduct their negotiations.

In this article, we have argued that paying attention to the everyday practices and knowledges at work in Hong Kong’s wet markets forces us to radically expand both the theoretical and empirical parameters of the concept of the lively commodity. The commodification of animals bound for dietary consumption relies no less on the production of specific kinds of encounters than do the processes associated with the commodification of animals for labor, entertainment, or companionship. Analyzing the practices and strategies associated with the negotiation and realization of the value of live seafood products poses critical scalar, ecological, temporal, and ethical challenges to existing theorizations, setting the terms for a more inclusive research agenda to which this article seeks to contribute. Viewed in their proper diversity, the implications of lively commodification for the future of life on this planet can hardly be ignored, choppy as these waters might be.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (39.4 MB)Acknowledgments

We are thankful for comments received when presenting this work at various fora, including the American Association of Geographers annual meeting in Denver in 2022, and at the Hong Kong Studies annual conference and the University of Melbourne’s School of Geography, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences in 2023. We are also grateful for the supportive comments from the two anonymous reviewers and for the editorial support of Kendra Strauss.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s site at: https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2024.2304200

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ben A. Gerlofs

BEN A. GERLOFS is an Assistant Professor and Deputy Head of the Department of Geography at The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, SAR, China, where he is also Director of the Cartographica Laboratory and Library and a Research Fellow of the Urban Systems Institute. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interests include the dynamics of urban change across spatiotemporal scale, the politics of aesthetics, and comparative urbanism.

Benjamin Lucca Iaquinto

BENJAMIN LUCCA IAQUINTO is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Geography at the University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong, People’s Republic of China. E-mail: [email protected]. His research explores the political and environmental implications of tourism mobilities.

Kylie Yuet Ning Poon

KYLIE YUET NING POON is a PhD Student in the Department of Geography at the University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90024. E-mail: [email protected]. Her research interests include the everyday experiences of Southeast Asian male migrant domestic helpers in Hong Kong, and the sales of lively commodities in Hong Kong’s wet markets.

Cathy Tung Yee Tsang

CATHY TUNG YEE TSANG is an MA Student in the Department of Geography at McGill University, Montréal, QC, Canada H3A0G4. E-mail: [email protected]. Her research interests include the commodification of liveliness in Hong Kong’s wet markets, and the livelihoods and everyday politics and resistance of Hmong rural-to-urban migrants in Kunming, Yunnan Province, China.

Notes

1 Establishing consistent terminology remains a particularly fraught exercise for our research. For the purposes of this article we have elected to use the terms seafood and seafood products to describe any and all marine or semimarine animals bought and sold in Hong Kong’s wet markets.

2 This temporality calls into question Collard and Dempsey’s (Citation2013) categorical dismissal of animals bound for slaughter as meat. As we demonstrate, the moment of encounter is crucial to the sale of live seafood products, and the production and performance of liveliness are of singular, determinative significance in such encounters.

3 As most participants recruited in person were aged between forty and seventy-five, younger consumers in their twenties and thirties were recruited via the social media pages of live seafood businesses to increase the diversity of our data set.

4 Many animals ultimately die before they are sold, despite vendors’ efforts.

5 These tofu puffs are reportedly perfectly edible and are occasionally advertised as such.

6 Notable exceptions include several religious groups (e.g., Buddhists) and many expatriates.

7 Many vendors sell both frozen and live seafood products, although live animals tend to occupy far more space and a considerably larger share of a given vendor’s offerings.

8 Such knowledge includes the nature and timing of reproductive seasons, as animals shift metabolic energies in ways that are generally understood to affect the texture and flavor of their flesh.

9 In August 2023, Hong Kong announced that it would ban imports of seafood from ten Japanese prefectures in response to the releasing of waste water from the Fukushima nuclear power plant into the Pacific Ocean, despite Japanese assurances that the planned release was endorsed by the International Atomic Energy Agency. Many have interpreted this ban as rooted at least as much in geopolitical tensions between Beijing and Tokyo as in concerns over food safety, although official sources have flatly dismissed such appraisals (see Lo, Cheung, and Liu Citation2023).

References

- Barua, M. 2016a. Lively commodities and encounter value. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 34 (4):725–44. doi: 10.1177/0263775815626420.

- Barua, M. 2016b. Nonhuman labour, encounter value, spectacular accumulation: The geographies of a lively commodity. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 42 (2):274–88. doi: 10.1111/tran.12170.

- Barua, M. 2018. Animal work: Metabolic, ecological, affective. Fieldsights, July 26. Accessed December 11, 2023. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/animal-work-metabolic-ecological-affective.

- Bersaglio, B., and J. Margulies. 2022. Extinctionscapes: Spatializing the commodification of animal lives and afterlives in conservation landscapes. Social & Cultural Geography 23 (1):10–28. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2021.1876910.

- Bougoure, U., and B. Lee. 2009. Service quality in Hong Kong: Wet markets vs supermarkets. British Food Journal 111 (1):70–79. doi: 10.1108/00070700910924245.

- Bridge, G., J. McCarthy, and T. Perreault. 2015. Editor’s introduction. In The Routledge handbook of political ecology, ed. T. Perreault, G. Bridge, and J. McCarthy, 3–18. London and New York: Routledge.

- Buller, H. 2014. Animal geographies I. Progress in Human Geography 38 (2):308–18. doi: 10.1177/0309132513479295.

- Chan, V. 2023. Markets made modular: Constructing the modern “wet” market in Hong Kong’s public housing estates, 1969–1975. Urban History 50:799–817. doi: 10.1017/S0963926822000153.

- Cheung, J. 2020. Inside wet markets, the heart of neighbourhood life in Hong Kong. Zolima City Mag, July 14. Accessed December 11, 2023. https://zolimacitymag.com/inside-wet-markets-the-heart-of-neighbourhood-life-in-hong-kong/.

- Clement, S. 2019. GoProing: Becoming participant-researcher. In Feminist research for 21st century childhoods, ed. B. D. Hodgins, 149–58. London: Bloomsbury.

- Collard, R. C. 2014. Putting animals back together, taking commodities apart. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 104 (1):151–65. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2013.847750.

- Collard, R. C., and J. Dempsey. 2013. Life for sale: The politics of lively commodities. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 45 (11):2682–99. doi: 10.1068/a45692.

- Cronon, W. 1991. Nature’s metropolis: Chicago and the great West. New York: Norton.

- Freidberg, S. 2007. Supermarkets and imperial knowledge. Cultural Geographies 14 (3):321–42. doi: 10.1177/1474474007078203.

- Freidberg, S. 2010. Fresh: A perishable history. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Gerlofs, B. A. 2021. Seismic shifts: Recentering geology and politics in the Anthropocene. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 111 (3):828–36. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2020.1835458.

- Gibbs, L. M. 2020. Animal geographies I: Hearing the cry and extending beyond. Progress in Human Geography 44 (4):769–77. doi: 10.1177/0309132519863483.

- Gillespie, K. 2021. The afterlives of the lively commodity: Life-worlds, death-worlds, rotting-worlds. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 53 (2):280–95. doi: 10.1177/0308518X20944417.

- Goldman, A., R. Krider, and S. Ramaswami. 1999. The persistent competitive advantage of traditional food retailers in Asia: Wet markets’ continued dominance in Hong Kong. Journal of Macromarketing 19 (2):126–39. doi: 10.1177/0276146799192004.

- Haraway, D. 2008. When species meet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Hovorka, A. J. 2017. Animal geographies I: Globalizing and decolonizing. Progress in Human Geography 41 (3):382–94. doi: 10.1177/0309132516646291.

- Lo, H. Y., W. Cheung, and O. Liu. 2023. Hong Kong to ban Japanese seafood imports from 10 prefectures after country announces plan to release Fukushima waste water starting Thursday. South China Morning Post, August 22. Accessed December 11, 2023. https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/health-environment/article/3231886/hong-kong-leader-john-lee-calls-immediate-curbs-japanese-seafood-after-country-announces-plans.

- Marinelli, M. 2018. From street hawkers to public markets: Modernity and sanitization made in Hong Kong. In Cities in Asia by and for the people, ed. Y. Cabannes, M. Douglass, and R. Padawangi, 229–57. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Mele, C., M. Ng, and M. B. Chim. 2015. Urban markets as a “corrective” to advanced urbanism: The social space of wet markets in contemporary Singapore. Urban Studies 52 (1):103–20. doi: 10.1177/0042098014524613.

- Ni’am, L., S. Koot, and J. Jongerden. 2021. Selling captive nature: Lively commodification, elephant encounters, and the production of value in Sumatran ecotourism, Indonesia. Geoforum 127:162–70. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.10.018.

- Parreñas, R. J. S. 2012. Producing affect: Transnational volunteerism in a Malaysian orangutan rehabilitation center. American Ethnologist 39 (4):673–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1425.2012.01387.x.

- Povinelli, E. 2016. Geontologies: A requiem to late liberalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Power, E. 2012. Domestication and the dog: Embodying home. Area 44 (3):371–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4762.2012.01098.x.

- Rancière, J. 2010. Dissensus: On politics and aesthetics. London: Bloomsbury.

- Robbins, P. [2004] 2012. Political ecology. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Ross, R. B. 2008. Contradictions of cultural production and the geographies that (mostly) resolve them: 19th-century baseball and the rise of the 1980 Players’ League. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 26 (6):983–1000. doi: 10.1068/d4408.

- Schroeder, R. 2018. Moving targets: The “canned” hunting of captive-bred lions in South Africa. African Studies Review 61 (1):8–32. doi: 10.1017/asr.2017.94.

- Shell, J. 2019. Giants of the monsoon forest: Living and working with elephants. New York: Norton.

- St. Martin, K. 2005. Disrupting enclosure in New England fisheries. Capitalism Nature Socialism 16 (1):63–80. doi: 10.1080/1045575052000335375.

- Tsing, A., H. Swanson, E. Gan, and N. Bubandt, eds. 2017. Arts of living on a damaged planet: Monsters of the Anthropocene. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Verheijen, F. J., and W. F. G. Flight. 2008. Decapitation and brining: Experimental tests show that after these commercial methods for slaughtering eel Anguilla anguilla (L.), death is not instantaneous. Aquaculture Research 28 (5):361–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2109.1997.tb01053.x.

- Whatmore, S. 2002. Hybrid geographies: Natures, cultures, spaces. London: Sage.

- Wilson, R. 2015. Mobile bodies: Animal migration in North American history. Geoforum 65:465–72. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.04.001.

- Wright, M. 2006. Disposable women and other myths of global capitalism. London and New York: Routledge.

- Yam, S. Y. S. 2022. Towards a differential ethics of belonging in a transnational context: Navigating the Hong Kong movement in the US in 2020 and 2021. Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 43 (3):29–62. doi: 10.1353/fro.2022.0023.

- Yusoff, K. 2018. A billion black Anthropocenes or none. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Zhong, S., M. Crang, and G. Zeng. 2020. Constructing freshness: The vitality of wet markets in urban China. Agriculture and Human Values 37 (1):175–85. doi: 10.1007/s10460-019-09987-2.