ABSTRACT

This study addresses landscape changes in the quilombola territories of the communities Alto Trombetas 1 and 2, on the banks of the Trombetas River. It also points out transformations that have taken place since the creation of federal conservation units and the installation of bauxite mining activities in the region. The production and management of overlaps involves a heterogeneous network of state actors, artifacts, and socio-technical apparatuses that materialize interventions in the landscape, in a web of government bodies, norms, and a discourse favorable to progress and profit. This overlap has made the communities organize themselves against the invasion of their lands and struggle constantly to give visibility to the effects of mining and conservation units. We conclude that the history of questionable interventions from different sectors of the state has compromised the coexistence of quilombola territories with other lives in the region. Also, the lack of monitoring and studies focused on the effects of mining on quilombola communities shows how environmental racism falls upon racialized bodies and territories. However, quilombola communities continue to resist in their ancestral territories.

RESUMO

Este artigo aborda as alterações de paisagem nos territórios quilombolas Alto Trombetas 1 e 2, que vivem às margens do rio Trombetas, e as transformações no ambiente desde a criação de unidades de conservação federal e da instalação de atividade minerária de bauxita na região. A produção e a gestão das sobreposições envolvem uma heterogênea rede de atores estatais, artefatos e aparatos sociotécnicos que materializam as intervenções na paisagem: órgãos governamentais, normas, discursos favoráveis ao progresso e ao lucro. Tais sobreposições exigiram das comunidades organização para enfrentar a invasão de suas terras e constante luta para visibilidade dos efeitos causados pela mineração e pelas unidades de conservação. Concluímos que o histórico de intervenções questionáveis de distintos setores do Estado comprometeu a coexistência dos territórios quilombolas com as demais vidas no lugar, bem como a falta de acompanhamentos e estudos voltados aos efeitos da mineração para as comunidades quilombolas demonstram as formas com que o racismo ambiental incide sobre corpos e territórios racializados. Entretanto, as comunidades quilombolas seguem resistindo em seus territórios ancestrais.

RESUMEN

Este artículo aborda los cambios paisajísticos en los territorios quilombolas Alto Trombetas 1 y 2, a orillas del río Trombetas, y las transformaciones en el medio ambiente desde la creación de unidades federales de conservación y la instalación de actividades mineras de bauxita en la región. La producción y gestión de superposiciones involucra una red heterogénea de actores estatales, artefactos y aparatos sociotécnicos que materializan intervenciones en el paisaje: organismos gubernamentales, normas, discursos favorables al progreso y al lucro. Tales superposiciones requirieron que las comunidades se organizaran para enfrentar la invasión de sus tierras y luchar por visibilizar los efectos causados por la minería y las unidades de conservación. Concluimos que la historia de intervenciones cuestionables de diferentes sectores del Estado comprometió la convivencia de los territorios quilombolas con otras vidas en el lugar. La falta de monitoreo y estudios enfocados a los efectos de la minería en las comunidades quilombolas demuestran las formas en que el racismo ambiental se centra en cuerpos y territorios racializados. Sin embargo, las comunidades quilombolas siguen resistiendo en sus territorios ancestrales.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE:

PALABRAS-CLAVE:

1. Introduction

This article aims to discuss changes in the landscape and in the life conditions of quilombola communities. They are part of the territories Alto Trombetas 1 and 2 and have continued to exist since the creation of federal conservation units and the start of bauxite mining that has occurred over time. These events have greatly affected the two quilombola territories located in the municipality of Oriximiná, in the state of Pará, Brazil. The territories defined as Alto Trombetas 1 and Alto Trombetas 2 are immersed in the Amazon and are bathed by the waters of the Trombetas River, a tributary of the Amazon River ().

Figure 1. Access to the quilombola community via the Trombetas River. Source: Author’s collection.

Note: Quilombola community houses on the Trombetas River.

The Brazilian Amazon is widely known for the occupation and resistance of indigenous peoples. However, enslaved black labor was also used in the colonization and exploration of this space. As compiled by Andrade (Citation1995) on the formation of quilombos in the region, enslaved people were taken to cattle and cocoa farms in the region around 1780. Quilombola communities were formed mainly after the escape of enslaved people, with the first records of punitive expeditions in the region dating back to 1812 (Andrade Citation1995).

However, the expeditions carried out against quilombos in the region did not mean the end of this movement. Historiography also shows that relations between enslaved people and non-black populations ranged between hostility and commercial exchange. As Gomes (Citation2015) points out, the “black field” was built from a large network of solidarity between enslaved people, freed people, and sympathizers; so, quilombos were not separated from society or from relationships with other non-human that made up the environment. Over the years, black communities took on different names, but the common factor was resisting enslavement. After the promulgation of the Federal Constitution of 1988, quilombolas became subjects of rights, with provided guarantees regarding territory titling and heritage protection (Article 68 of the ADCT and Articles 215 and 216).

Taking into account the diversity of self-applied denominations by black communities and considering that quilombola is an exogenous concept constitutionally established by the state, an effort was made to conceptualize this subject of rights. The term quilombola comes from debates held in academia, and it was especially encouraged by the Brazilian Anthropology Association (ABA) (Citation1994). ABA presented a broad concept encompassing ethnic groups that resisted historical oppression, with ways of life related to their own territory and specific trajectory, and with social organization established on the basis of the members’ belonging.

Our analysis is based on empirical research carried out by Julia Marques Dalla Costa between 2016 and 2022 with the quilombola communities of Alto Trombetas 1 and 2, located in the municipality of Oriximiná, western region of the state of Pará. The author participated in a series of activities at the quilombola territories, such as gatherings with leaders and representatives of public institutions, as well as field activities related to the author’s professional duties as an analyst from the Instituto Nacional de Colonização e Reforma Agrária [National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform] (Incra).

The three authors share the professional experience of being anthropology analysts associated to Incra, a federal public institution. In this way, monitoring the processes of quilombola land regulation and environmental licensing, we are interested in producing a joint analysis that presents and scrutinizes the connection between different human and other-than-human actors based on changes in the region’s landscape, on the struggles of quilombola communities, and on criticism of regional development projects, which include state interests and private sector initiatives.

The anthropological work through Incra was supported by ethnographic insertion into part of the quilombola communities’ daily lives and their struggles in the defense of their territorial and existential rights. Therefore, the research is inherently qualitative, as objectivity emerges from the reconstitution of identity relationships, ethnic sense of belonging, and reciprocity with ancestral places in which (and with which) practices of resistance are developed to face the suffered historical oppression. These are places where, in the limits of the relation with the surroundings, collective practices and exchanges are updated in the present time. In the case of the quilombola communities of Oriximiná, these relationships were woven in the mediations of Incra's anthropology-based technical work. That was the case for the free and informed consultation about enterprises’ environmental licensing process, as they affect the quilombola population and their relationships with other species, whose lives are also threatened by projects and interventions that produce drastic changes in landscapes.

Thus, as stated, this work is methodologically inspired by the fieldwork carried out by Julia Marques Dalla Costa, by documentary research, and by the analytical perspective of mapping associations between different human and other-than-human actors in the socio-technical networks in which development policies materialize. We consider it impossible to separate epistemological questions from political dimensions (Almeida et al. Citation2022), as our analytical choices and research interests are necessarily implicated by our cosmopolitics – in the sense that we do not conceive politics without cosmos or a cosmos without politics (Stengers Citation2018; Latour Citation2016).

Therefore, the option of approaching socio-technical networks, based on the overlapping interests of the state’s different technical sectors and the private capital regarding the implementation of a mining project, is related to the conditions under which this analysis can be carried out. In regards to land regularization and environmental licensing for quilombola communities, especially the ones from Alto Trombetas, our work as federal public servants is guided by the understanding of the history of the territory's occupation, its social organization, and how the interests of the state were consolidated in the region.

From the work with these groups, it was possible to think beyond the state bureaucracy’s knowledge available on the topic. However, a brief study cannot exhaust so much complexity. Approaching the theme from this perspective – of ontological disputes and possible coexistences in the face of expansionist developmental projects – brings the potential for future studies that can also highlight the speeches and perspectives of the struggling quilombola groups ( and ).

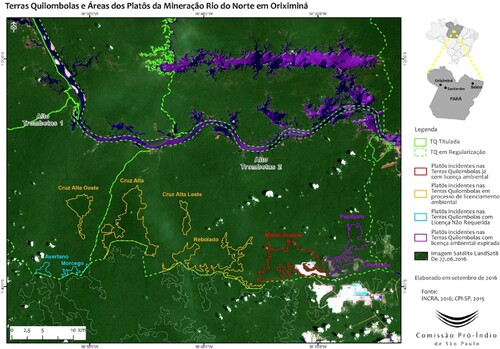

Figure 3. Bauxite mining plateaus in the Alto Trombetas quilombos. Source: São Paulo’s Pro-Indigenous Commission (CPISP).

Regarding the quilombola territories from Alto Trombetas, we present below an initial topic with historical information about the black occupation in the region and the mobilization that culminated in the foundation of the Association of the Remaining Quilombo Communities of the Municipality of Oriximiná (ARQMO). Regarding public land and environmental policies, in the next topic we track socio-technical networks according to their overlapping interests and actions in different spheres of the Brazilian state, as well as describe the implementation of mining activities in the Alto Trombetas region. The analysis continues as we address quilombola resistance practices in their territories, their disputes, and the effects of the interventions in the landscape by different state actors, artifacts, and socio-technical apparatuses.

2. Quilombos do Alto Trombetas

The quilombola communities of Alto Trombetas, located in Oriximiná, state of Pará, are recognized as protagonists in the struggle for the rights of these groups in Brazil. According to research (Andrade Citation1995; Andrade Citation2015; Incra Citation2017a and Citation2017b), fifteen communities live in two territories, traditionally occupied since the nineteenth century. The communities’ collective stories are related to the escape from enslavement by past generations and the possibility of acquiring freedom and establishing solidary relationships.

Historiography points out that enslaved labor had been widely used in cattle and cocoa farms in the western region of the current state of Pará since the eighteenth century. From the beginning of the nineteenth century, there are records of a large flow of slaves escaping from farms in the municipalities of Santarém, Oriximiná, Óbidos, and Alenquer. Escaping slavery led the quilombolas to the Trombetas River region, especially to areas where navigation was difficult. Among other occupations of land, in the first half of the nineteenth century runaway slaves founded in this area Quilombo Maravilha, the oldest quilombo mentioned by the residents of Trombetas. Quilombo Maravilha is where their roots are (Vicente Salles 1988 apud Andrade Citation1995). Numerous expeditions were undertaken throughout the nineteenth century to destroy quilombos whose existence became known. However, none of the expeditions caused the end of the settlements of runaway slaves in the region.

After the abolition of slavery in 1888, quilombola settlements were intensified in this region (Andrade Citation1995; Grupioni and Andrade Citation2015; Incra Citation2017a and Citation2017b). Due to this historical process, the quilombola communities of Abuí, Paraná do Abuí, Tapagem, Sagrado Coração, Mãe Cué, and Santo Antônio do Abuizinho were formed. Together they are the Quilombola Territory Alto Trombetas 1. Moura, Jamari, Curuçá, Juquirizinho, Juquiri Grande, Palhal, Último Quilombo/Erepecu, Nova Esperança, and Santa Lavoura form the territory called Alto Trombetas 2. Over more than a century of settlement, these communities developed a wide network of social relations consisting of close ties of kinship, solidarity, and reciprocity. These groups, which currently number more than 400 families, are spread along the Trombetas River and its lakes in an area of 351.377.2423 hectares.

We point out that the social organization of these communities and the fight for their rights, especially for access and maintenance of their territories, gained new momentum after the promulgation of the Federal Constitution. In testimony during a public hearing in 2017, a leader from the Quilombola Territory Alto Trombetas 1 reported that in August 1988, when he was at the headquarters of Oriximiná, he found a copy of the Federal Constitution that had been recently published in a local newspaper. He said he read Article 68 of the ADCT and immediately realized that the communities in which he and his relatives had been living were quilombos.

In this way, the constitutional provision, which recognizes the quilombolas as subjects of rights, met the demands of the community members of Alto Trombetas. Therefore, they formally organized themselves and began the struggle for collective titling of their lands (Almeida Citation1994). To achieve this, the quilombola groups have led political mobilizations and endured varied processes of territorial expropriation, which were experienced at different times and with different social consequences. The main threats to the Alto Trombetas territories include bauxite mining, which began in the 1970s and whose activities are still the responsibility of the company Mineração Rio do Norte (MRN). Furthermore, in 1979, the Rio Trombetas Biological Reserve was created, with 407.759.21 hectares, and in 1989, the Saracá-Taquera National Forest, with 441.282.63 hectares.

In July 1989, before the creation of the national forest reserve, the Associação das Comunidades Remanescentes de Quilombos do Município de Oriximiná [Association of Remaining Quilombo Communities of the Municipality of Oriximiná] (ARQMO) was founded. This association is contemporary with the installation of the mining company in the region, that occupied part of the quilombola lands, and with the creation of the biological reserve, which prevented access to Brazil nut forests; ARQMO’s main motivation was to ensure the right to property in quilombola lands as guaranteed by the Constitution.

In December 1989, following the events mentioned above, a delegation from ARQMO went to Brasília to demand titling for quilombola lands, accompanied by members of the Parish of Oriximiná and of the Pro-Indigenous Commission of São Paulo, a non-governmental organization that assists quilombola groups in the region. It took seven years of mobilizations that resulted in the titling of quilombola territories in the region, including Boa Vista (1995) and Água Fria (1996), both neighboring the mining site.

According to Almeida (Citation1994, 522), “the mobilization categories reflect, to an appropriate extent, the type of intervention by the state apparatus.” It is noted that the social organization of the quilombola communities of Alto Trombetas was, at first, around the struggle for land. We affirm that this process unfolds into a struggle for lives, for the river, and for the possibility of existing in the place. These mobilizations arise as a result of state interventions in the communities’ ancestral territories.

Over time, the quilombola communities of Alto Trombetas found different ways to continue building alliances in defense of their territories. An example of this was the organization of the Centro de Estudos e Defesa do Negro no Pará [Center for Studies and Defense of Black People in Pará] (CEDENPA), one of the pioneering organizations in the fight for the rights of rural black communities, especially in the states of Pará and Amapá (Andrade Citation2015). This dialogue allowed different communities in the region to converge their demands for land and public policies.

The creation of the biological reserve took place in a context of intense military repression in the country. According to Brazilian legislation, no human interference is allowed after the installation of a fully protected conservation unit, under the claim of preserving the biota of the stipulated area. In any case, the work of technicians and public managers to create such a state apparatus comprises a new modality of human intervention, in the sense that it regulates access and interventions into the area. According to Barretto Filho (Citation2002), the creation of fully protected conservation units in the Amazon took place between the 1970s and 1980s, being closely linked to the country's development project at the time. As a result of such environmental legislation, the inhabitants of these protected areas had their prior existence ignored.

At the time, the federal government acted through the Instituto Brasileiro de Desenvolvimento Florestal [Brazilian Institute for Forestry Development] (IBDF), that later became the Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis [Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources] (Ibama), a federal institution that brings together a relevant number of actors, devices, techniques, and governmental socio-technical apparatuses that are essential for environmental issues in Brazil. The government forcibly removed entire communities from their traditional areas, as these occupations had started to affect the biological reserve – a fact that is recorded in the collective memory of the groups. As Little (Citation2018) notes, “the Brazilian Environmental Institute (Ibama) became for black people the symbol of the oppressive power of the state, as it created obstacles to the traditional use of natural resources of the territory” (16).

The need to act with the state, especially concerning territorial demands, promoted the organization of the quilombolas from Alto Trombetas into two distinct social groups, each with independent territorial claims. For this study, we will address the activities of the Alto Trombetas groups whose representative associations are under the umbrella of ARQMO.

3. Overlapping state interests and sociotechnical networks – federal conservation units and the establishment of mining in the region

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the Trombetas region underwent new changes with the boost of extractivism, especially of Brazil nuts. The location began to be occupied by landowners, the so-called coronéis das castanhas (chestnut colonels), who benefited from the Lei de Terras (Land Law) of 1850, which aggravated the country’s agrarian situation. The end of slavery culminated in the exploitation by outsiders of Brazil nut forests in the region.

The end of the colonels’ era coincided with the installation of federal conservation units in the region. Through Decree 84,018, the Trombetas River Biological Reserve was created in 1979 as a fully protected conservation unit that, following environmental legislation (Article 42 of Law 9985/2000), did not allow human interference nor direct use of natural assets. As highlighted in the decree, “any alteration of the environment, including hunting and fishing in the area, is prohibited, except for duly authorized scientific activities.” The main objective in creating this conservation unit was to protect the chelonian species of the region, and waterfall areas that are home to particular fauna and flora (Ibama Citation2004) ().

Figure 4. Arrau turtle hatchlings. Source: Author’s collection.

Note: Arrau turtle hatchlings at ICMBio’s Tabuleiro base on the Trombetas River.

Thus, the installation of a fully protected conservation unit conflicts with the ancestral land occupation of quilombola communities in the region. According to research, the experience of being expelled from their homes because of the creation of the biological reserve is very present in the memory of community members. In addition to forced and violent removals, the biological reserve prevented the exercise of activities that are crucial to the survival and maintenance of the quilombolas’ ways of life, such as extractivism (especially of Brazil nuts), hunting, and fishing. Environmental legislation saw the quilombolas, ancestral inhabitants of the region, as the cause of environmental changes. The Conservation Unit's 2004 Management Plan presents the existence of quilombola communities, the opening of fields and pastures, the occupation of the waterfall area, chelonian collecting, hunting, fishing, and extractive activities as “conflicting activities” (Ibama Citation2004).

With the conservation unit, the environmental agency established an office with personnel in the region to monitor the area and develop activities that align with the objectives of the unit. In the case of the biological reserve, the quilombola residents were targeted by this team, with the implementation of the unit being a factor for control and violence in quilombola communities. Under the justification of nature preservation, community members had their rights to come and go restricted (suspension of boat traffic at specific times due to chelonians’ nesting periods); were prevented from maintaining decent housing (prohibition of construction and house renovation); were not allowed to open cultivation areas; and were prohibited from consuming products of hunting, fishing, and extractive activities, all of this under the penalty of fines and seizure of material and equipment. The conservation unit promoted intense control over the lives of quilombolas, limiting and regulating a centuries-old activity of relationship with the environment, and it was a strong instrument to demobilize communities.

Brazil nut harvesting involves enormous traffic throughout the Alto Trombetas territory. The very delimitation of quilombola territories by the Brazilian state took into account the communities’ way of life, and it was only concluded after an agreement between the quilombola groups from the different territories in regards to the common use of the areas. Considering the importance of this activity, in 2011 the Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade [Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation] (ICMBio) signed terms of commitment with associations that represented quilombola territories to regulate nut harvesting in the biological reserve area. However, the term of commitment has an expiration date, so it needs to be renewed each new cycle. This logic of periodicity is in line with legislation that prescribes the removal of populations residing in areas that become conservation units. Therefore, in theory, there would come a time when the document would no longer need to be signed for the total withdrawal of traditional communities. Differently, reality shows that these groups struggle to remain in traditional territories that make sense within a logic of collective belonging, one which state documents and formalities are not fit to follow.

Ethnographic research such as Scaramuzzi’s (Citation2016) demonstrates that, for the quilombola communities of Alto Trombetas, Brazil nut forests cannot exist long-term without the permanence of other social actors. These make up networks of mutual help that involve humans and others-than-humans, such as agoutis, arumãs, and other plant species in the region. In this way, there is disagreement with the state's preservationist policy that considers quilombola communities as predatory agents of the environment and as threats to nut forests, other native plants, and animal species ().

Figure 5. Brazil nuts in a community from Alto Trombetas. Source: Author’s collection.

Note: Nuts inside the fruit.

Ten years after the creation of the biological reserve, the quilombola communities faced the creation of the Saracá-Taquera National Forest, in 1989. In Decree 98,704, which established the unit, the big news was the authorization of mining activities and the indication of the company that would be responsible for it. Mineral exploration to extract bauxite in the region began in the 1970s, and the National Forest decree from 1989 established that one of the unit's functions was to preserve mineral resources to be exploited by the company Mineração Rio do Norte (MRN).

Mining in Trombetas’ quilombola region has successfully taken place for 46 years. The construction of infrastructure and the mining activities began between 1976 and 1979. According to records (Incra Citation2017a), the initial production capacity was 3.35 million tons of bauxite per year, which expanded over the years. Furthermore, between 2003 and 2011, MRN invested in expansion projects, with its production capacity increasing from 11 million to 16.3 million tons of bauxite. The year 2005 had a production record, with 17.21 million tons of bauxite.

Therefore, the historiography of the region demonstrates the ancestry of the communities, which have secularized relationships of coexistence with Brazil nut trees, other extractive species, the Trombetas River, chelonians, among others-than-humans with whom they have historically lived. All these lives began to be equally threatened by the change in the environment due to the arrival of mining and the establishment of conservation units.

It is important to emphasize that the creation of conservation units obstructed and bureaucratized the coexistence of quilombola populations, under the justification that quilombola “anthropization” could harm the conservation of several native species of the region. However, these risks and impacts were relativized in over-exploitative projects carried out in mining. An example of this is the fact that, when the conservation units were created, the quilombolas were prohibited from consuming some animal species, such as chelonians, among others, and, due to the chelonian breeding areas at the beaches, entire communities were removed to “not interfere” with the reproduction of these animals.

Still, while quilombolas were prohibited from consuming chelonians, huge boats were entering the Trombetas River to load bauxite, altering the aquatic life of conservation units, without the prohibition of overexploiting these locations. In this sense, we highlight the role of mining and conservation units as pivots of expropriations against quilombola groups, as well as of alterations in their traditional ways of living. It is observed that most of the impacts caused by mining over the years were not followed by studies about quilombola communities and by proper compensation.

The Alto Trombetas 1 and 2 titling processes are among the oldest at Incra, having been initiated in 2004, and the identification and delimitation studies of territories began in 2007. With quilombola land regularization work underway at Incra, the situation administratively and legally defined as “overlapping interests of the state” was formalized, that is, when two rights equally guaranteed by the Federal Constitution clash. The right to title quilombola territories is guaranteed by Article 68 of the ADCT, and the right to an ecologically balanced environment is guaranteed by Article 225 of the Federal Constitution. Until 2020, Incra was only responsible for the land regularization of quilombos, while environmental licensing was managed by Fundação Cultural Palmares [Palmares Cultural Foundation]. It was only with the transference of this attribution of environmental licensing of quilombos to Incra that this issue also started being addressed by the institution.

Based on the identified overlap between quilombos and conservation units, negotiations were initiated within the scope of the Federal Administration to resolve the controversy between the organizations responsible for implementing the two public policies: on the one hand, Incra, and on the other, ICMBio, forming a network of actors linked to spheres of the state. During the years that followed, counting only with the participation of public institutions, the federal government's negotiations did not make significant progress. Environmental agencies presented proposals that consisted of removing communities or significantly reducing their traditional territories. This period was marked by a strong conservationist discourse, in which environmental agencies could not see compatibility between traditional communities and environmental reserves. However, after years and without any consensus on the situation, the negotiations needed to be discussed in another way to try to produce results.

The impetus for significant advance to occur was the court decision handed down in 2016 against ICMBio, responsible for the federal conservation units, and Incra, responsible for the titling of quilombos. Together, these federal institutions carried out the titling of the Alto Trombetas quilombos. Once the court ruling determining the titling of the territories was handed down, both the agrarian and environmental authorities established a direct channel for dialogue through an Interinstitutional Work Group, from 2016 onwards. Thus, the technical studies that presented the territorial proposal of the quilombola communities were published in 2017 ().

Figure 6. State servants and quilombolas from Alto Trombetas 1. Source: Author’s collection.

Note: Teams from Incra and the Fundação Cultural Palmares with quilombolas from Alto Trombetas 1.

The publication of Incra studies generated a concrete fact that has had diverse implications for the communities. Due to the publicity of the territorial proposal, ICMBio began to be held accountable and monitored by quilombolas and non-governmental organizations, concerning activities within the quilombos’ limits. In addition to the overlapping with conservation units, mining enterprises could no longer fail to consult quilombola communities to obtain the many licenses required to operate in the plateaus. Before Incra's technical reports had been published, federal legislation did not consider it mandatory to consult quilombola communities to issue licenses for mining activities.

Thus, until the Alto Trombetas’ technical reports were materialized with due publication within the administrative plan, the licensing body was not obliged to consult nor did it consider the limits of quilombola areas when issuing environmental licenses. The mining company even started a controversy with the licensing institution (Ibama) to question the right to free, prior, and informed consultation as provided for in the ILO Convention 169, because, according to the MRN, the quilombolas were not the target public of this instrument. After a long debate in the federal administration, the state's understanding that the quilombolas were part of the Convention 169 was consolidated, ending questions of this nature.

From 2017 on, with the reports duly published, a new phase of negotiations began and, this time, the quilombola communities of Alto Trombetas were included in the debate. Previously, there was an understanding that government bodies should reach an agreement and then present it to the communities for consultation. In contrast this new period was marked by the inclusion of communities in discussions regarding the government's plan for the issue. Meetings were held in Brasília and in the territories to discuss the terms of conciliation. In 2017, for the first time, all government intitutions that followed the process went together to a quilombola territory to expose the issue, solve doubts, and discuss with the communities the proposed solutions that had been designed jointly among technicians from environmental bodies and leaders of quilombola communities.

Considering the different projects undertaken over time – from the exploitation of Brazil nut forests during slavery, the creation of conservation units, until the advent of mining – numerous socio-technical mediations were employed. That is, such policies were made possible through the emergence of networks made up of different actors, domains (Latour Citation2019) and techniques, such as nut forests, CUs, turtle hatchlings to be “protected,” Ibama and ICMBio offices, legislation, the National Forest reserve, bauxite, mining machines, reports, concession terms, etc.

In this context, in which countless socio-technical apparatuses act to implement the policies and techniques that transform places, the concept of Plantationocene helps us think about places where multispecies exercise coexistence (Haraway, Citation2023) and how these places are reduced to “markets of consumable resources” (Ferdinand Citation2022). However, to expand the critique of the Plantationocene (Haraway Citation2015; Tsing Citation2019), we need to recognize and point out that the plantation as a past has not only shaped the logic of racialization of the environment and deprived quilombola populations from being subjects of rights in their ancestral lands, but it has also reproduced, amplified, and expanded colonial forms of inhabitation, living, and production nowadays.

In other words, the critical descriptions of the policies of the Plantationocene must also highlight the centrality of racial dynamics (Davis et al. Citation2019), that continue to be exercised in disputes concerning the possible futures in places targeted by economic super-exploitation. However, critical descriptions need to be embodied in the countless forms of struggle and resistance in lived and inhabited territories that resist as a tireless source of healing resources (Anjos and Silva Citation2004). Moreover, these territories and their peoples bring together strategies and technologies developed locally, generation after generation, as practices of resistance to the degradation of lives and biodiversity.

4. Disputes and effects of interventions on the landscape

We can see that the production and management of overlaps involves a heterogeneous network of state actors, artifacts, and socio-technical apparatuses that materialize interventions in the landscape: government bodies, norms, and discourses favorable to progress and profit, among others. It is observed that different “domains” (legal, political, economic, etc.) are in association during the actions involved in the dispute over what may exist on the banks of the Trombetas River and in the surrounding forests. It is evident that the actions of different human and more-than-human actors are entangled, based on the different agencies that occur in these diverse networks.

Such sociotechnical networks are not taken analytically as physical places, but as hybrid associations that materialize the social. In other words, such connections between different actors, who act among themselves, produce effects on the relationships in which they are associated. In this case, disputes involving the policies of conservation units, the struggles of quilombola communities, and bauxite mining expansion projects.

Sixteen years have passed since the beginning of debates about the state’s overlapping interests between quilombola territories and conservation units. Much of this time involved fruitless debates and no progress in which the sustainability of quilombola communities’ way of life would be truly considered. As we have seen, since 2016 dialogs have intensified and taken a more constructive direction, and the key to this change was the inclusion of quilombola communities in the debate. Currently, the environmental agency is committed to titling the quilombola communities of Alto Trombetas, so that they can coexist with the mining units. In an unprecedented way, ICMBio will title quilombola communities within a fully protected conservation unit, which marks a paradigm shift for the issue of protected areas in Brazil.

While the agenda of conservation units and quilombola territories reached a new level of debate, mining exploration in the region went the opposite way, with activities expanding in intense conflict with quilombola communities. Bauxite mining begins with the exploration of plateaus, that are previously defined with authorization from the national mining body. After the authorization for exploration, environmental licensing for the work is awarded, with each plateau having its own licensing. To remove bauxite, total suppression of plants is necessary, that is, the complete extraction of all flora ().

Figure 7. Ship to load bauxite in Porto Trombetas. Source: Author’s collection.

Note: Ship parked to load bauxite in Porto Trombetas, municipality of Oriximiná/PA.

In the context of the environmental disasters of Brumadinho and Mariana dams, which occurred respectively in 2015 and 2019, the enormous risks and impacts to the affected population became evident, as well as the impact on rivers and countless species threatened by the exploitation of these projects (Zhouri Citation2018). From this, the concern of mining companies in mitigating the knowledge about the negative effects of minerals over-exploitation has emerged. An example of this was the numerous attempts by the mining company that exploits bauxite in the Trombetas River to differentiate itself from the company that produced the disasters in Mariana and Brumadinho. Below, we selected two excerpts from statements in the Brazilian press in defense of this mineral exploration. The statements are clear about the intention to safeguard the exploratory activities that occur in Oriximiná and to proclaim such activities as indispensable for development ().

Table 1. Speeches in defense of mineral exploration in Oriximiná.

Both speeches attempt to differentiate bauxite mining and to present it as “good” mining, sustainable, impact-free. Above all, they appeal to the supposed benefits that this activity brings to the national economy, as well as to the harm to “development” if bauxite mining’s image were associated with the activities that led to the environmental disasters that have occurred because of mining. We highlight that there are 27 MRN bauxite tailings dams, 25 of which are located within the Saracá-Taquera National Forest, and the other two are in the mining company's port area, which is 430 meters from Quilombo Boa Vista (Wanderley Citation2021) ().

Figure 8. Effects of bauxite mining on the Trombetas River and forests. Source: Carlos Penteado for São Paulo’s Pro-Indigenous Commission.

Note: Batata Lake, close to the Trombetas River, silted up by bauxite waste (photo from 2016).

At this point, bauxite mining has transformed the lifestyles of the populations involved, as there was, for example, forced appropriation of quilombola lands, which severely affected biodiversity, especially the Trombetas River and the lives associated to it. Furthermore, mining did not bring decent jobs and, as quilombolas pointed out, “mining made the community [us] think it was just like a city. If we want to eat fruit, we have to buy it. We even buy flour, because it [the mining company] has slowly taken this from us” (Amarildo, leader of the quilombo Boa Vista, in an interview with Repórter Brasil, Borges and Brandford Citation2020).

The reality pointed out by Amarildo outlines the local reality. While quilombola communities work for recognition and compensation for decades-long mining, they are neighbors of the mining company and use some services and facilities that have been installed close to their territories. However, the relationship is historically difficult. The mining company carries out activities that are part of its social responsibility portfolio, but they do not fall into the category of compensation and mitigation for mining impacts. The activities must be evaluated and thought about with the communities’ participation, within the environmental licensing process, but this relationship has just occurred more recently. In other words, the years of mining activities and the implementation of the mining company's village and ports were not discussed, and had no offset for their impact. Quilombola communities, therefore, were included in this process long after major impacts had affected their territories and ways of life, without any sign of compensation.

The destruction of biomes, the elimination of local economies, and the annihilation of territorialized ways of being, doing, and living are some of the consequences highlighted in research on the violence of affectations (Zhouri Citation2018). At this point, we propose a “friction” (Camana Citation2020; Tsing Citation2019) between critical approaches concerning developmental policies and the countless ecological simplifications that arise from the plantation expansion mindset, that is, the expansion and forced appropriation of immense biodiverse areas that are now considered functional, naturally and legitimately destined for economic accumulation. Although we do not refer to a classic plantation perspective in the cases of the affected quilombola communities analyzed here, a mindset of flattening countless ways of life, from human and other-than-human populations, prevails. These populations have secularized relationships of coexistence in these places, and their existence is disregarded and precluded by mining overexploitation policies. Moreover, these populations are inhibited from exercising traditional forms of management that historically have not prevented species from being preserved, as protectionist policies claim.

However, we observe that environmental racism and the racialization of land uses are decisive explanatory keys to understanding how the discourse of landscape predation is stabilized and normalized, as the exploitative logic of capital and of large corporations has been affecting racialized bodies, their ancestral knowledge, and their inhabited territories at an accelerated pace.

5. Final considerations

The research addressed aspects of the struggles of quilombola communities that make up the Alto Trombetas 1 and 2 territories to continue existing on the banks of the Trombetas River, despite changes in the landscape and changes in living conditions, since the creation of federal conservation units and the advent of bauxite mining. The changes produced countless effects on their territories and changed these populations’ possibilities of living and working in their biodiverse ancestral places, once these became fully protected conservation units, or even functional areas for mining exploration.

Despite the asymmetrical nature of local transformations following the creation of federal conservation units in quilombola territories, after many years it is known that the environmental agency has changed its understanding of whether quilombolas pose harm and threat environmental conservation. The major current understanding in force is that these people are essential for preserving the environment and fighting climate change. In any case, such recent advances in this regard come from the quilombola struggles in Alto Trombetas. Despite the imposition of institutional rules concerning land occupation, boat traveling in specific areas, practices on traditional cultivation of Brazil nut forests, and hunting and fishing activities such as collecting chelonians, the communities have continued to come up with their own strategies to fight against forms of violation and arrests that have historically put these actors in the basement of modernity (Ferdinand Citation2022).

The proposition of black anthropocenes, as suggested by Kathryn Yusoff (Citation2018), informs us on the supposed absorbing qualities of racialized bodies (from a colonial perspective). These bodies are historically the ones that have taken the burdens related to toxicity exposure, such as in territories dominated by monoculture or mining, besides being the bodies that cushion the violence related to conflicts over access, use, and permanence in the land. The violence experienced by the quilombolas from Alto Trombetas resonates with such analysis in the sense of a pursuit to name the many voids within local experiences, as such experiences encompass multiple scales and extractivist economies that instill anti-blackness (or, environmental racism), by implementing policies and projects based on the plantation model.

Despite the rapidly growing expansion of mining in the region, most of the impact derived from such private enterprises throughout the years has not been followed by studies focused on the quilombola communities, nor by due offset for their losses. Both state interventions (which at first, in the name of environmental conservation, reproduced environmental and institutionalized racism addressing the quilombolas’ ways of living) and the installation of private projects in the region fell preferably upon racialized bodies and territories, regardless of the right to free, prior, and informed consultation as guaranteed by ILO’s C169.

On the other hand, the quilombolas’ struggle to remain in their territories and to maintain the biodiverse practices of each traditional territory of the Alto Trombetas region, add to the debate and to a new analysis of the expanding meaning of environmental justice and cosmopolitics. Based on Malcom Ferdinand’s contributions, Fagundes (Citation2022) reflects on a third resemanticization of quilombo as a category. His view converges, in this sense, with the presented practices of quilombola resistance as a possibility for “the aquilombamento [aquilombonation] of humans and non-humans as a practice of ecological resistance” (Fagundes Citation2022, 314).

In this way, the ethnographic situation addressed in our work accounts for a long trajectory of black resistance, with mobilization and practices that have built territories for interspecies alliances that co-produce sociodiversity and biodiversity (Fagundes Citation2022). Also, such alliances expand our understanding of quilombola struggles beyond something limited to the struggle for access and permanence on the land, that is, to the titling of traditionally occupied territories.

Our contribution to the debate aimed at reflecting on quilombola struggles and disputes over landscape changes in the Alto Trombetas region, as researchers from inside the state structure, with know-how on quilombola public policies of land regularization and environmental licensing. Other more substantial analyses, especially the ones done from the perspective of the subjects in struggle, will contribute to the improvement of future research. In any case, in this article, we intended to look at this arena of conflicts from a place linked to technical-scientific disputes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Julia Marques Dalla Costa

Julia Marques Dalla Costa holds a master's degree in Social Anthropology from the University of Brasilia, where she also graduated in Social Sciences with a major in Sociology and in Anthropology. She is a Social Policies Analyst and is currently an advisor to the Vice Minister of Rural Development and Family Farming, working in the areas of land governance and traditional peoples and communities. Between 2014 and 2023, she worked on the land regularization of quilombola territories and environmental licensing in quilombola areas for INCRA. She is a researcher associated with the Laboratory of Ethnography of Institutions and Practices of Power (Leipp) at the University of Brasilia and a member of the Anthropologist's Professional Insertion Committee of the Brazilian Anthropology Association.

Vanessa Flores dos Santos

Vanessa Flores dos Santos is a PhD Candidate and holds a master's degree in Social Anthropology from the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (PPGAS-UFRGS), and a Bachelor's degree in Social Sciences from the Federal University of Santa Maria. She is an affiliate researcher at the Anthropology and Citizenship Center (NACi) Department of Social Anthropology (UFRGS - Porto Alegre/ Brazil). Flores dos Santos works as an analyst in agrarian reform and development/anthropology at the National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA).

Eleandra Raquel da Silva Koch

Eleandra Raquel da Silva Koch is a social scientist. She holds a master's degree in Sociology and a PhD in Rural Development from the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul. She works as an analyst in agrarian reform and development/anthropology at the National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform. She is an associate researcher in the Technology, Environment and Society research group at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul.

References

- ABA – Associação Brasileira de Antropologia. 1994. Documentos do Grupo de Trabalho sobre as comunidades Negras Rurais. Florianópolis: Boletim Informativo NUER, n.1.

- Almeida, Alfredo W. B. 1994. “Universalização e localismo: Movimentos sociais e crise dos padrões tradicionais de relação política na Amazônia.” In A Amazônia e a crise da modernização, edited by M. A. D’Incao and I. M. Silveira, 517–532. Belém: Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi.

- Almeida, Jalcione, Ângela Camana, Lorena Cândido Fleury, Marília Luz David, Camila Dellagnese Prates, and Gabriel Bandeira Coelho. 2022. “Em favor das associações: Uma homenagem à sociologia de Bruno Latour (1947–2022).” Sociologias 24 (61): 142–168.

- Andrade, Lúcia M. M. de. 1995. “Os Quilombos da Bacia do Rio Trombetas: Breve Histórico.” Revista de Antropologia 38 (1): 79–99.

- Andrade, Lúcia M. M. de. 2015. “Quilombolas em Oriximiná: desafios da propriedade coletiva.” In Entre Águas Bravas e Mansas – índios e quilombolas em Oriximiná, edited by Denise F. e Grupioni and Lúcia M. M. de Andrade, 194–209. São Paulo: Comissão Pró-Índio de São Paulo, Iepé.

- Anjos, José Carlos Gomes dos, and Sérgio Baptista Silva, eds. 2004. São Miguel e Rincão dos Martimianos: ancestralidade negra e direitos territoriais. Porto Alegre: Editora da UFRGS.

- Barretto Filho, H. T. 2022. “Preenchendo o Buraco da Rosquinha: Uma análise antropológica das unidades de conservação de proteção integral na Amazônia brasileira.” Boletim da Rede Amazônia Diversidade Sociocultural e Políticas Ambientais 1 (1): 45–49.

- Borges, Thais, and Brandford, Sue. 2020. “Mina de bauxita deixa legado de pobreza e poluição em quilombo do Pará.” Repórter Brasil, 7 July. https://reporterbrasil.org.br/2020/07/mina-de-bauxita-deixa-legado-de-pobreza-e-poluicao-em-quilombo-do-para/.

- Camana, Ângela. 2020. “Moçambique é um Mato Grosso no meio da África.” In O desenvolvimento e suas fricções em torno ao acontecimento do Prosavana. 2020. 274 f. Thesis (Doctorate in Sociology). Programa de Pós-Graduação em Sociologia. Porto Alegre: Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. https://lume.ufrgs.br/bitstream/handle/10183/217710/001121728.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Davis, Janae, Alex A. Moulton, Levi Van Sant, and Brian Williams. 2019. “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, … Plantationocene?: A Manifesto for Ecological Justice in an Age of Global Crises.” Geography Compass 13 (5): e12438. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12438.

- Fagundes, Guilherme Moura. 2022. “Sociedade contra a Plantation: Uma ressemantização ecológica dos quilombos.” In Uma Ecologia Decolonial – Pensar a Partir do Mundo Caribenho, edited by M. Ferdinand, 314. São Paulo: UBU.

- Ferdinand, M. 2022. Uma Ecologia Decolonial – Pensar a Partir do Mundo Caribenho. São Paulo: UBU.

- G1. 2020. Mineração Rio do Norte completa 41 anos de operação em Porto Trombetas, no Pará. G1, Santarém, 13 August. https://g1.globo.com/pa/santarem-regiao/noticia/2020/08/13/mineracao-rio-do-norte-completa-41-anos-de-operacao-em-porto-trombetas-no-para.ghtml.

- Gomes, Flávio dos Santos. 2015. Mocambos e Quilombos. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

- Grupioni, F. Denise, Andrade M. M. Lúcia (orgs). 2015. Entre Águas Bravas e Mansas, índios & quilombolas em Oriximiná. São Paulo: Comissão Pró-Índio de São Paulo, Iepé.

- Haraway. Donna, J. 2023. Ficar com o problema: Fazer parentes no chthluceno. Tradutora: Ana Luiza Braga; Graziela Marcolin. São Paulo. N-1 Edições.

- Haraway, D. 2015. “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin.” Environmental Humanities 6 (1): 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3615934.

- Ibama – Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis. 2004. Plano de Manejo da Reserva Biológica do Rio Trombetas. Documento elaborado por STCP Engenharia de Projetos LTDA. Brasília: IBAMA/MMA.

- Incra – Instituto Nacional de Colonização e Reforma Agrária. 2017a. Relatório Técnico de Identificação e Delimitação (RTID) das Comunidades Quilombolas do Alto Trombetas 1. Relatório Antropológico elaborado por Júlia Otero dos Santos em 2008. Santarém: INCRA.

- Incra – Instituto Nacional de Colonização e Reforma Agrária. 2017b. Relatório Técnico de Identificação e Delimitação (RTID) das Comunidades Quilombolas do Alto Trombetas 2. Relatório Antropológico da Comunidade Quilombola Moura elaborado por Teresa Cristina da Silveira em 2014. Relatório Antropológico de Jamari/Último Quilombo elaborado por Nirson Medeiros da Silva Neto em 2014. Santarém: INCRA.

- Latour, Bruno. 2016. Cogitamus: Seis cartas sobre as humanidades científicas. São Paulo: Editora 34.

- Latour, Bruno. 2019. Investigação sobre modos de existência: Uma antropologia dos modernos. Petrópolis: Vozes.

- Little, Paul E. 2018. “Territórios sociais e povos tradicionais no Brasil: por uma antropologia da territorialidade.” Anuário Antropológico 28 (1): 251–90.

- Revista Alumínio. 2019. Especial Mineração de Bauxita: Como é feita a extração e qual a importância da atividade para o Brasil. Revista Alumínio, 30 September. https://revistaaluminio.com.br/especial-mineracao-de-bauxita-como-e-feita-a-extracao-e-qual-a-importancia-da-atividade-para-o-brasil/#:~:text=Mas%20vale%20destacar%20que%20a,cidades%20e%20comunidades%20do%20entorno.

- Scaramuzzi, Igor Alexandre Badolato. 2016. Extrativismo e as relações com a natureza em comunidades quilombolas do rio Trombetas/Oriximiná/Pará. Doctoral thesis: Universidade Estadual de Campinas.

- Stengers, Isabelle. 2018. “A proposição cosmopolítica.” Revista do Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros (69): 442–464. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-901X.v0i69p442-464

- Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2019. Viver nas ruínas: Paisagens e multiespécies no antropoceno. Brasília: IEB Mil folhas.

- Wanderley, Luiz Jardim. 2021. Barragens de mineração na Amazônia: O rejeito e seus riscos associados em Oriximiná. São Paulo: Comissão Pró-Índio de São Paulo.

- Yusoff, Kathryn. 2018. A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None. Minneapolis, MN: The University of Minnesota Press.

- Zhouri, Andréa, ed. 2018. Mineração, violências e resistências: Um campo aberto à produção de conhecimento no Brasil. Marabá: Editorial iGuana; ABA.