ABSTRACT

Objective

This study aims to fill in the gap by exploring the interrelationship among academic emotions, classroom engagement and self-efficacy in EFL learning among Chinese non-English majors in smart classrooms.

Methods

A total of 409 non-English majors in their first year from a Chinese university completed the revised version of the academic emotions scale, classroom engagement scale and self-efficacy scale and their interrelationship has been analysed by Structural Equation Modelling.

Results

Positive emotion significantly enhances classroom engagement, while negative emotion does not. Classroom engagement has a significant effect on promoting self-efficacy, which is influenced by both positive and negative emotions, with positive emotions having a greater impact. Specifically, classroom engagement mediates the relationship between positive emotion and self-efficacy, whereas it does not mediate between negative emotion and self-efficacy.

Conclusion

Smart classrooms can stimulate students’ positive academic emotions, increase their engagement in learning so as to enhance their self-efficacy.

KEY POINTS

What is already known about this topic:

Academic emotion, engagement and self-efficacy have significant influence on learning.

Self-efficacy plays a mediating role between students’ engagement and academic emotion.

Academic emotion is situational and influenced by such factors as classroom atmosphere.

What this topic adds:

The relationship among academic emotion, engagement, and self-efficacy in smart classrooms has been explored.

It has investigated the mediating role of classroom engagement between positive emotion and self-efficacy.

This study focuses on the academic emotions, engagement, and self-efficacy of Chinese English learners, offering a unique perspective in different cultural contexts.

Introduction

In Education Informatization 2.0 Action Plan issued in 2018, the Chinese Ministry of Education simply proposed to promote the practice of smart education and integrate artificial intelligence into teaching, and to drive the creation of new educational concepts, models, teaching content, and methods (Education Mo, Citation2018). Based on artificial intelligence, smart classroom teaching with smart technology makes smart education possible (Parinsi & Ratumbuisang, Citation2017). Following that, in 2020, Guidelines for Chinese College English Teaching was issued, which required universities to provide a favourable information technology environment for both teachers and students engaged in language teaching and learning, as well as encouraging teachers to use modern teaching methods appropriately to enhance the effectiveness of their instruction (Committee EDHECETG, Citation2020).In line with these trends, Chinese college English teaching has also moved to the smart classroom and utilized interactive technology to create and construct smart teaching models to enhance students’ learning experience. A smart classroom is just a physical classroom, designed to integrate advanced forms of educational technology in order to enhance the instructors’ ability to facilitate the students’ learning as well as the students’ ability to participate in formal educational learning experiences beyond what is possible in a traditional classroom (MacLeod et al., Citation2018). Classrooms are not only spaces for academic learning, but also emotional settings where students experience a wide range of emotions (Hargreaves, Citation1998; Zins et al., Citation2007).

Emotions have a significant impact on various aspects of human functioning, including learning, memory, motivation, psychological well-being, and neural functioning (Tyng et al., Citation2017).While academic emotions refer to various emotional experiences related to students’ academic learning, classroom teaching and academic achievement, including such a variety of emotions of delight, hope, anxiety, anger, relief, boredom, hopelessness and so on that are experienced by students upon learning about their academic successes or failures (Pekrun et al., Citation2002). Academic emotions are regarded as a key factor affecting learning due to their significant impact on students’ cognitive processes, motivation, engagement, and overall academic performances (Pekrun et al., Citation2002; Pekrun, Citation2006). Student engagement is effortful learning through interaction with the teacher and the classroom learning opportunities (Christenson et al., Citation2012), which is important to a student’s eventual academic success, cognitive development, long-term achievement and the quality of education (Kahu & Nelson, Citation2017; Skinner & Pitzer, Citation2012). Active engagement in classroom activities has a positive impact on English language learning, while passive engagement is detrimental to English learning. English is an important communication tool and particular attention should be given to its practical application. Thus, participation and interaction in college English classes are of particular importance. Self-efficacy as individuals’ beliefs in their abilities to perform a task (Bandura, Citation1986), is believed to affect students’ learning behaviour so as to have a powerful influence on their learning ability (Bandura, Citation1977). Students with high self-efficacy are able to monitor their learning effectively, which is an important characteristic of university students’ success (Hill, Citation1977). And learners’ self-efficacy for foreign language affects performance in different language domains (Raoofi et al., Citation2012).

From the above, it can be found that academic emotion, engagement and self-efficacy have significant effects on learning and play crucial roles in the learning process. And many studies have revealed how they affect students’ academic performances and how self-efficacy impacts engagement as a mediating role or how self-efficacy and academic emotions impact students’ engagements as mediating roles (Han & Ju, Citation2023; Li, Shi et al., Citation2020; Tomás et al., Citation2020; Wolverton et al., Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2022). While the above-mentioned studies primarily either focused on conventional teaching environments, with limited involvement in smart classroom settings or predominantly targeted elementary and middle school students. In terms of the study in the context of smart classroom, some researchers have highlighted the importance of teacher and social support, self-efficacy, and autonomous motivation in promoting deep cognitive engagement (Lu et al., Citation2022) and some have examined the relationship between college students’ classroom preferences in a smart learning environment and their learning engagement (Lu et al., Citation2022) and some explored the relationship between human-computer interaction and cognitive load as well as academic emotions (Nie et al., Citation2023). The above-mentioned studies have provided a solid foundation and valuable insights for the current study. However, they also highlight the relatively limited research on the relationships among academic emotions, classroom engagement, and self-efficacy, especially in the context of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teaching scenarios in China. Moreover, most studies often focus on self-efficacy as the mediating variable, with limited consideration given to engagement. Since the academic emotions of students are context-specific, which means that their academic emotions are influenced by the situations and experiences they encounter in the classroom, including classroom teaching quality, interactive learning, and classroom atmosphere (Efklides & Volet, Citation2005; Goetz et al., Citation2006; Xu & Gong, Citation2009). And the academic emotions in the smart classroom must be different from those in the traditional classroom. In view of the above, this study aims to explore the nature of academic emotions, engagement, and self-efficacy in the context of smart classrooms in EFL teaching and examine the relationship among the three and particularly in terms of examining engagement as a mediating role between the academic emotions and self-efficacy among EFL learners in China.

Literature review and hypotheses development

Smart classroom and academic emotions

Different from traditional classroom, smart classroom equipped with modern technologies such as 3 G and 4 G, interactive learning, uninterrupted audio and video transmission, and recording and uploading the lecture in a website (Alelaiwi et al., Citation2015), is a physical classroom that incorporates advanced educational technologies to enhance the teaching capabilities of teachers and the learning efficiency of students. Sevindik (Citation2010) perceived the smart classroom as a new form that combines the human-computer interaction interfaces, related technologies, and traditional teaching methods in the field of electronics, creating an innovative, advanced, and flexible learning environment. It can be included that a smart classroom is a new form that combines electronic technology with teaching, creating an innovative and flexible learning environment to enhance teaching efficiency and facilitate personalized learning. In terms of the studies on the smart classroom, Jaechoon et al. (Citation2016) identified important factors influencing the effectiveness of smart classroom usage, including perceived usefulness and ease of use of the technology, system enjoyment, and the appropriate timing and manner of integrating information technology in the teaching process. According to Kwet and Prinsloo (Citation2020), the physical environment of a smart classroom facilitates teaching experience, technical application, data management, space environment, and technical environment. Zhang et al. (Citation2019) believed that the presence of interactive technologies in smart classrooms plays a significant role in enhancing student engagement across behavioural, cognitive, and affective dimensions. According to Goetz et al. (Citation2003), students’ involvement in socializing with teachers and peers in educational(classroom) setting can influence their academic emotions.

The concept of academic emotions was introduced by Pekrun, Gortz, Titz, and Raymond. and referred to positive and negative emotions directly related to academic learning, classroom teaching, and academic achievement as academic emotions (Pekrun et al., Citation2002). And academic emotions encompass not only the various feelings experienced by students upon attaining or failing in their academic endeavours, but also those experienced during classroom instruction (Yan & Guoliang, Citation2007). Human emotions can be conceptualized within a two-dimensional structure, where valence represents the horizontal dimension and arousal represents the vertical dimension. Valence refers to the pleasantness or unpleasantness of a stimulus, while arousal indicates the level of physiological activation (Citron et al., Citation2014, Van & Balsam, Citation2014; Russell, Citation2003). Taking into account the valence and arousal dimensions of emotion, academic emotions can be classified into four categories: negative low arousal academic emotions (NLA), including boredom, sadness, hopelessness and disappointment; negative high arousal academic emotions (NHA), including anger, anxiety, and shame; positive low arousal academic emotions (PLA), including relaxation, contentment, relief and positive high arousal academic emotions (PHA), including enjoyment, joy, hope and pride (Pekrun et al., Citation2002; Ravaja et al., Citation2004). Positive emotions often have a positive impact on learning, which can stimulate students’ intrinsic motivation, enhance their self-regulation efforts, and promote the use of more sophisticated learning strategies. Negative emotions often correlate with negative effects, such as anxiety and boredom, which can have adverse impacts on students’ academic performance (Pekrun et al., Citation2011) and overall satisfaction with their learning experiences (Daniels et al., Citation2009).Previous studies have shown that academic emotions influenced academic achievements of students (Corradino & Fogarty, Citation2016; Putwain et al., Citation2022).In the studies, Kim et al. just found that emotions can account for 37% of the variation in students’ academic performances in the course of maths (Kim et al., Citation2014).Due to the significant role that emotions play in academic performances, numerous studies have also been conducted to explore the factors influencing it (Xu & Gong, Citation2009).Although there are studies on the academic emotions in the e-learning context or examined the emotional contagion issues in smart classroom (Lee & Chei, Citation2020; Li, Gao et al., Citation2020), the research on academic emotions in the smart classroom, particularly in the context of English as a Foreign Language (EFL), is limited and lacks comprehensive exploration. Thus, based on the above, the first hypothesis is that in the context of EFL learning in the smart classroom, academic emotions are influenced and may exhibit distinctive characteristics(H1).

Student engagement and its relationship with academic emotions

Hu and Kuh (Citation2002) defined engagement as the quality of effort students themselves devote to educationally purposeful activities that contribute directly to desired outcomes. Classroom engagement can be categorized into overall student engagement and individual student engagement. Indicators such as student participation, attitude towards participation, modes of participation, depth of participation, and effectiveness of participation just serve as metrics for assessing classroom teaching (Li & Bai, Citation2011).The researches on classroom engagement focuses on various aspects, including the influencing factors of engagement, strategies to enhance participation, current status of participation, and measurement and evaluation of engagement (Delfino, Citation2019; DeVito, Citation2016; Kassab et al., Citation2023). Kundu et al. (Citation2021) investigated the effects of blended environment on students’ classroom engagement, and Ayçiçek and Yanpar Yelken (Citation2018) studied the effect of flipped classroom model on students’ classroom engagement in teaching English. But there is a scarcity of research on the engagement in the context of EFL teaching in higher education within smart classrooms.

Patrick et al. (Citation2007) identified the social and emotional classroom environments as essential prerequisites for fostering students’ engagement with activities and tasks. Academic emotions may be associated with students’ learning engagement (Linnenbrink-Garcia & Pekrun, Citation2011). According to the broaden-and-build hypothesis of positive emotion (Fredrickson, Citation2001), positive emotions can enhance learners’ cognition, promote flexible thinking and creative problem solving, and encourage learners to put more effort and persistence into the learning process, which may enhance student engagement. In contrast, negative academic emotions may limit the cognitive resources required to perform learning activities. Pentaraki and Burkholder (Citation2017) conducted a comprehensive review to explore the emerging research evidence on the influence of emotions on students’ engagement, specifically focusing on the unique role that emotions may play in online learning. Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia (Citation2012) maintained that engagement mediates the relationship between emotions and learning. In this context, the second hypothesis of the current study is that in the smart classroom, the academic emotions have impact on Chinese EFL learners’ engagement (H2). And the third hypothesis following that in the context of EFL learning in a smart classroom, positive emotions significantly enhance student engagement compared to negative emotions (H3).

Academic self-efficacy and its relation with student engagement

Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s subjective judgement whether they have the ability to complete a specific behaviour (Bandura, Citation1977). Academic self-efficacy encompasses students’ beliefs and attitudes regarding their capabilities to attain academic success, which involves their confidence in their ability to fulfil academic tasks effectively and successfully learn the subject matter (Bandura et al., Citation1999; Schunk & Ertmer, Citation2000). Self-efficacy in EFL learning can be perceived as an individual’s personal evaluation of their competence in achieving English learning objectives and many studies have proved that self-efficacy is a predictor that learners successfully use various English autonomous learning strategies in their learning process (Bandura et al., Citation2003; Zhong & Wang, Citation2008). People with high self-efficacy can plan effectively, confidently and successfully in finishing a task or achieve goals while those with low self-efficacy attribute their failure to their low abilities and give up easily (Kurbanoğlu & Akin, Citation2010; Schunk & Mullen, Citation2012). It has been found that academic self-efficacy could consistently predict students’ academic achievement and the relationship between self-efficacy and actual academic engagement has been established empirically (Bong, Citation2008; Zimmerman et al., Citation1992). Therefore, it can be observed how important of individual’s self-efficacy is in learning and achieving school goals. One of the influencing factors of self-efficacy put forward by Bandura is physiological states, which means individuals’ affective states including enjoyment and abomination, satisfaction and depression, relaxation and anxiety would affect the self-efficacy (Bandura et al., Citation1999). In other words, positive or negative emotions may influence students’ self-efficacy. In terms of the relationship between self-efficacy and classroom engagement, Pintrich and De Groot’s study (Pintrich & Groot, Citation1990) has found that self-efficacy was positively related to learners’ cognitive engagement and academic self-efficacy can improve academic performance by increasing academic engagement (Meng & Zhang, Citation2023).Consequently, this study proposed the fourth and fifth hypothesis: The engagement has an impact on students’ self-efficacy in the context of EFL learning in a smart classroom(H4) and it has a mediating effect between academic emotions and self-efficacy (H5). Based on the hypothesis that the positive emotions significantly enhance student engagement compared to negative emotions, we propose the sixth hypothesis of this study: Positive emotions impacts self-efficacy in a significant way(H6).

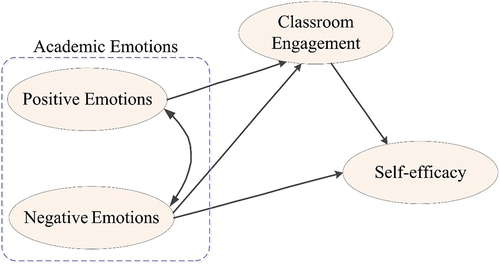

Based on the series of hypotheses above, the theoretical model of the current study is shown in which explains the relationship between academic emotions, student engagement and self-efficacy in EFL context in the smart classroom.

Research methods

Participants and procedures

The participants in this study were freshmen from School of Computer and Software Engineering of a university in the eastern part of China who enrolled in the autumn semester of 2022. As the research was conducted at a predominantly engineering-focused undergraduate institution, specifically in the School of Computer and Software Engineering, there are generally more male students at this institution than female students. Therefore, out of a total of 409 respondents who submitted questionnaires, 336 were males, while 73 were females. These students have been chosen because they have been studying college English courses in a smart classroom since their enrolment in their freshman year. After obtaining informed consent from the educational office of the university, an online questionnaire hosted by Wenjuanxing(https://www.wjx.cn/) was distributed to those students and they were provided with clear explanations regarding the questionnaire’s objectives and how their responses would be utilized for research purposes. And they were also ensured that their answers were anonymous and would in no way affect their examination scores. All the participants signed the informed consent form at the beginning of the study. In addition, this study was approved by the research committee of Anhui Institute of Information Technology and all procedures met its ethics standards (with approval no. 202102), the Helsinki Declaration in 1964, and other similar ethical standards.

Instruments

A 17- item 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1(strongly disagree) to 5(strongly agree) was adopted for participants. These items were adopted by previous literature and adapted by previous scales to measure participants’ academic emotions (Yang, Citation2015), including 6 items of positive emotions and 4 items of negative emotions; classroom engagement (Fuchun et al., Citation2021) with 4 items and self-efficacy (Schwarzer & Born, Citation1997; Schwarzer et al., Citation1997) with 3 items in the EFL context in the smart classroom. For the purpose of obtaining accurate and reliable data, the questionnaire has been administered in the participants’ native language, which is Chinese. For some selected scale items originally in English, the researchers have translated them into Chinese and subjected them to a review by experts in English. Finally, the entire questionnaire is distributed to participants in Chinese. And the questionnaire items for each latent variable and their corresponding observed variables are shown in the following:

Table 1. Questionnaire items and corresponding observed variables for each latent variable.

While the questionnaire above was adapted from established maturity scales, a validity test was conducted to verify its reliability. The results of the validity testing in SPSS 25.0 are shown in as follows for Cronbach’s alpha coefficients and Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) sampling adequacy:

Table 2. Construct validity test.

From the above table, it is evident that there is a high level of consistency among different items within the measurement tool. Specifically, all three variables exhibit Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients exceeding 0.8, aligning with the well-accepted standards for internal consistency. Even for the variable with a Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of 0.79, it still meets an acceptable threshold (>0.7) (Schweizer, Citation2011). Furthermore, all variables demonstrate KMO values surpassing 0.7, indicating a high level of suitability for factor analysis. Therefore, the structural validity of all four latent variables has reached an acceptable level.

Structural equation modeling

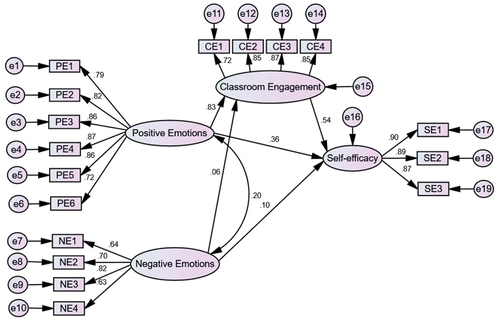

This study employed AMOS 25.0 to construct a Structural Equation Model (SEM) and performed parameter estimation using the maximum likelihood method. Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) is a quantitative statistical method employed in research that is capable of analysing variables. SEM is specifically designed for the identification and validation of causal models, representing a confirmatory approach that is well-suited for investigating relationships among factors in educational psychology research (Byrne, Citation2010). The SEM model fit results are shown in .

The key parameters of the SEM model are presented in :

Table 3. Key fitting parameters of the SEM model.

The above parameters indicate that the model has acceptable fit results. The value of CMIN/DF is 2.88 (p = 0.000), and the values of RMSEA (<0.08) and SRMR (<0.06) fall within the standard range, indicating a good fit of the model. Additionally, in terms of comparative fit indices, the parameters CFI, TLI, and NFI are all greater than 0.90. Therefore, it can be concluded that the proposed model in this study is effective.

Results

The results of the standardized parameters for the relationships between variables are presented in :

Table 4. Fitting results of the SEM model.

The SEM model results reveal that positive emotions (PE) have a significant positive effect on classroom performance (CE) (std. β = 0.83, 95% CI = 0.737 ~ 0.903, p = 0.000). On the other hand, negative emotions (NE) show a moderate effect on classroom performance (std. β = 0.06, 95%CI = −0.028 ~ 0.162, p = 0.191). Since p = 0.191 > 0.05, it indicates that negative emotions do not have a significant positive effect on classroom engagement. Taking into account the effects of PE→CE and NE→CE, it can be concluded that Hypothesis 2 (H2) is supported, indicating that students’ academic emotions influence their performances in English class, with positive emotions significantly promoting classroom performance. Furthermore, the influence of positive emotions (PE→CE) on classroom performance is significantly higher (std. β = 0.83, p = 0.000 < 0.05) compared to the impact of negative emotions (NE→CE) on classroom performance (std. β = 0.06, p = 0.191 > 0.05). This supports Hypothesis 3 (H3). What’s more, students’ classroom performance has a positive effect on self-efficacy enhancement (CE→SE) with a standardized loading factor of 0.54 (95% CI = 0.330 ~ 0.722, p = 0.000). This provides clear evidence for the acceptance of Hypothesis 4 (H4), indicating that students’ classroom engagement in EFL teaching in a smart classroom can contribute to the improvement of their self-efficacy. Finally, the positive impact of students’ positive emotion on self-efficacy (PE → SE) (std. β = 0.36, 95% CI = 0.175 ~ 0.571, p = 0.000 < 0.001) is significantly higher than the impact of negative emotion on self-efficacy (NE → SE) (std. β = 0.10, 95% CI = 0.039 ~ 0.180, p = 0.001), providing evidence for the acceptance of Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Regarding the mediating role of classroom engagement in the relationship between academic emotions and self-efficacy enhancement, this study has employed Bootstrap estimation with 5000 resamples in AMOS for calculation and evaluation (Preacher & Hayes, Citation2008). The results indicate a significant mediating effect of classroom engagement between positive emotions and self-efficacy enhancement (PE→CE→SE) with a β coefficient of 0.45 (95% CI = 0.290 ~ 0.621, p = 0.000). Since p < 0.05 and the confidence interval does not include 0, the results are regarded as reliable. Besides, the mediating effect of classroom engagement between negative emotions and self-efficacy enhancement (NE→CE→SE) is not significant, with a β coefficient of 0.03 (p = 0.165 > 0.05) and a confidence interval ofCI = −0.012 ~ 0.101 that includes 0. Therefore, the mediating hypothesis is not supported, suggesting that classroom engagement does not exhibit a mediating effect between negative emotions and self-efficacy enhancement. In summary, Hypothesis 5 (H5) is supported, indicating a significant mediating effect of classroom engagement between positive academic emotions and self-efficacy enhancement.

The introduction of smart classrooms has brought about various changes in traditional teaching methods and learning environments. Through further exploration of the results from path analysis, it is evident that students exhibit diverse academic emotions during the learning process, including positive and negative emotions. These academic emotions have direct and indirect effects on students’ classroom engagement and self-efficacy. These findings provide clear support for Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Discussion

Smart classrooms are equipped with modern technologies, e.g., Learning Management Systems (LMS), high-speed Internet connection, high-resolution camera, and behavioural data analysis software and hardware systems. It aims to improve the efficiency of the classroom management and the effectiveness of learning and teaching (Yu et al., Citation2022). Smart classrooms have brought many advantages to EFL learning, and have promoted innovation in teaching methods and the use of teaching tools. With the aid of “cloud + terminal” learning activities and support services, teachers are able to create inquiry-based learning environments that stimulate the interest and engagement of students.

Compared to traditional classrooms, smart classrooms can provide more flexible and accessible ways of acquiring knowledge in English teaching. In this context, this study aims to examine how variables such as academic emotion, classroom engagement, and self-efficacy interact in EFL learning in smart classroom. Based on the previous results, it is found that students exhibit diverse academic emotions, including positive and negative emotions in the learning process in the smart classroom. And these academic emotions have direct and indirect effects on students’ classroom engagement and self-efficacy enhancement. A more in-depth and comprehensive discussion will be provided in the subsequent sections.

The analysis of structural equation models reveals that students’ academic emotion has an important influence on classroom engagement and self-efficacy in the scenario of a smart classroom. According to these findings, there is a close relationship between teaching characteristics and students’ academic emotions in the smart classroom setting.

First of all, it is found that in the context of smart classroom EFL learning, positive emotions have a significant impact on students’ engagement. It follows that students who experience positive emotions during the learning process, such as excitement, optimism, and confidence, are more likely to engage. It may due to the fact that a smart classroom environment may provide more opportunities for cultivating students’ positive emotions through the innovation of teaching methods and learning tools. The use of multimedia can enhance students’ positive emotions by making learning content more interesting, attractive, and appealing through the use of images, audio, video, and other forms of media. In addition to stimulating students’ curiosity and desire to explore, the virtual lab offers a learning experience that cannot be obtained in a real lab. Online quizzes can stimulate students’ sense of competition and accomplishment by providing immediate feedback and presenting their performances. The results of our study indicate that negative emotions do not have a significant impact on classroom engagement. In other words, students’ negative emotions, such as anxiety and worry, do not directly contribute to their engagement in class. Despite the fact that negative emotions do not encourage classroom engagement directly, attention still should be given to their potential impact because negative emotions may negatively affect students’ motivation, attention, and learning strategies, indirectly affecting their participation in class and their learning outcomes (Tzafilkou et al., Citation2021). As a result, teachers can promote positive emotions in students by creating a interactive learning environment and encouraging students’ interest and curiosity, thus improving their engagement in the smart classroom.

A further analysis also shows that students’ classroom engagement in the smart classroom contributes to their sense of self-efficacy. Engagement in the classroom reflects students’ ability to understand and apply knowledge. As students engage well in the classroom, they develop greater confidence in their ability to learn, which in turn increases their self-efficacy and helps them achieve better academic results (Hayat et al., Citation2020). Therefore, educators should be aware of students’ self-efficacy and provide them with ample support and encouragement to build their learning confidence, enabling them to face challenges with greater courage. Moreover, the results also indicate that positive emotions have a significant impact on self-efficacy. This implies that students are more likely to develop self-confidence when they experience positive emotions during the learning process, which is crucial for students’ motivation and academic achievement (Köseoglu, Citation2015).

Additionally, this study found that classroom engagement mediates the relationship between academic emotion and self-efficacy. The results indicate that classroom engagement is a significant mediator between positive academic emotion and self-efficacy. Students’ positive emotions could indirectly contribute to their sense of self-efficacy by increasing their engagement in class. In other words, when students experience positive emotions in the smart classroom, they are more likely to engage in the class and have stronger confidence in their learning ability, thereby strengthening their cognition and evaluation of their learning ability and increasing their self-efficacy. By creating a positive feedback loop, students can further stimulate their motivation to learn and achieve better academic results. There was, however, no significant mediation effect between negative emotions and self-efficacy. This suggests that classroom engagement has a relatively weak association between negative emotions and self-efficacy. Therefore, educators should cultivate positive emotions in students and encourage them to participate actively in smart classroom activities so as to enhance their self-efficacy and motivation in EFL learning.

Limitations

In this study, limitations include the possibility that the sample size may be limited to specific schools or regions, and is therefore not representative of the entire population of non-English majors in China. Moreover, although the survey scale has been revised, there may still be problems with self-report bias and subjectivity. Additionally, the study used a cross-sectional design, studying relationships at a specific point in time but is not conducive to observing changes in variables over time. To explore the long-term effects of smart classrooms on students’ academic emotion, classroom engagement, and self-efficacy, future research may adopt a longitudinal design. To increase the representativeness and generalization of the research, larger sample sizes and multi-centre studies across different schools or regions should be considered.

Conclusion

This study has adopted structural equation modelling to examine the relationship between students’ academic emotion, classroom engagement and self-efficacy of EFL learning in smart classrooms in China, and the following conclusions are drawn: The first thing to note is that positive emotions have a significant impact on students’ classroom engagement while negative emotions do not have a significant impact. The second finding is that students’ engagement promotes self-efficacy. Thus, it is concluded that positive emotions have a significant impact on improving students’ self-efficacy, while negative emotions have no noticeable effect. Based on further analysis, it is evident that classroom engagement act as a mediator between positive emotion and self-efficacy, while it does not mediate the relationship between negative emotion and self-efficacy. Smart classrooms provide a personalized learning environment that promotes student development and enhances learning experiences. Students’ academic emotions, classroom engagement, and self-efficacy are closely correlated with the teaching characteristics of smart classrooms. Educators should make full use of the diversified teaching tools and interactive ways of smart classrooms to create a positive learning atmosphere, cultivate students’ positive academic emotions and encourage students’ learning interest and engagement to enhance their self-efficacy.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge people who participated in this study by filling in the questionnaires.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alelaiwi, A., Alghamdi, A., Shorfuzzaman, M., Rawashdeh, M., Hossain, M. S., & Muhammad, G. (2015). Enhanced engineering education using smart class environment. Computers in Human Behavior, 51, 852–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.061

- Ayçiçek, D. D. B., & Yanpar Yelken, T. (2018). The effect of flipped classroom model on students’ classroom engagement in teaching English. International Journal of Instruction, 11(2), 385–398. https://doi.org/10.12973/iji.2018.11226a

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Bandura, A., Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Gerbino, M., & Pastorelli, C. (2003). Role of affective self-regulatory efficacy in diverse spheres of psychosocial functioning. Child Development, 74(3), 769–782. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00567

- Bandura, A., Freeman, W. H., & Lightsey, R. (1999). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 13(2), 158–166. https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.13.2.158

- Bong, M. (2008). Effects of parent-child relationships and classroom goal structures on motivation, help-seeking avoidance, and cheating. The Journal of Experimental Education, 76(2), 191–217. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.76.2.191-217

- Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Christenson, S. L., Reschly, A. L., & Wylie, C. (Eds.). (2012). Handbook of research on student engagement. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Citron, F. M. M., Gray, M. A., Critchley, H. D., Weekes, B. S., & Ferstl, E. C. (2014). Emotional Valence and arousal affect reading in an interactive way: Neuroimaging evidence for an approach-withdrawal framework. Neuropsychologia, 56, 79–89. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.01.002

- Committee EDHECETG. (2020). Guidelines for college English teaching (2020 ed.). Higher Education Press.

- Corradino, C., & Fogarty, K. (2016). Positive emotions and academic achievement. Applied Psychology Opus.

- Daniels, L. M., Stupnisky, R. H., Pekrun, R., Haynes, T. L., Perry, R. P., & Newall, N. E. (2009). A longitudinal analysis of achievement goals: From affective antecedents to emotional effects and achievement outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(4), 948–963. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016096

- Delfino, A. (2019). Student engagement and academic performance of students of Partido State University. Asian Journal of University Education, 15(3), 42–55. doi:10.24191/ajue.v15i3.05

- DeVito, M. (2016). Factors influencing student engagement [ Unpublished Certificate of Advanced Study Thesis]. Sacred Heart University, http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/edl/11

- Education Mo. (2018, April 25). Notice from the ministry of education on issuing the action plan 2.0 for education informatization [EB/OL]. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- Efklides, A., & Volet, S. (2005). Emotional experiences during learning: Multiple, situated and dynamic. Learning & Instruction, 15(5), 377–380. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2005.07.006

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. The American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.56.3.218

- Fuchun, Z., Ya, T., Yahong, N., & Xiulan, Y. (2021). Development of a measurement scale for student classroom engagement in the flipped classroom model. Jiangsu Higher Education, 4, 66–72. doi:10.13236/j.cnki.jshe.2021.04.011

- Goetz, T., Frenzel, A. C., Pekrun, R., & Hall, N. C. (2006). The domain specificity of academic emotional experiences. The Journal of Experimental Education, 75(1), 5–29. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.75.1.5-29

- Goetz, J., Kiesler, S., & Powers, A. (2003). Matching robot appearance and behavior to tasks to improve human-robot cooperation. In Proceedings RO-Man 2003: The 12th IEEE International Workshop on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (pp. 55–60). https://doi.org/10.1109/ROMAN.2003.1251796

- Han, Z., & Ju, H. (2023). The relationship between physical activity and academic engagement among college students-the mediating chain effect of trait mindfulness and self-efficacy. Revista de Psicología del Deporte (Journal of Sport Psychology), 31(4), 195–205. https://mail.rpd-online.com/index.php/rpd/article/view/1009

- Hargreaves, A. (1998). The emotional practice of teaching. Teaching & Teacher Education, 14(8), 835–854. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(98)00025-0

- Hayat, A. A., Shateri, K., Amini, M., & Shokrpour, N. (2020). Relationships between academic self-efficacy, learning-related emotions, and metacognitive learning strategies with academic performance in medical students: A structural equation model. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-01995-9

- Hill, W. F. (1977). Learning: A survey of psychological interpretations (3rd ed.). Thomas Y. Crowell.

- Hu, S., & Kuh, G. D. (2002). Being (dis)engaged in educationally purposeful activities: The influences of student and institutional characteristics. Research in Higher Education, 43(5), 555–575. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020114231387

- Jaechoon, J., Jeongbae, P., Hyesung, J., Yeongwook, Y., & Heuiseok, L. (2016). A study on factor analysis to support knowledge based decisions for a smart class. Information Technology and Management, 17(1), 43–56. doi:10.1007/s10799-015-0222-8

- Kahu, E., & Nelson, K. (2017). Student engagement in the educational interface: Understanding the mechanisms for student success. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(1), 1–14. doi:10.1080/07294360.2017.1344197

- Kassab, S. E., Al-Eraky, M., El-Sayed, W., Hamdy, H., & Schmidt, H. (2023). Measurement of student engagement in health professions education: A review of the literature. BMC Medical Education, 23(1), 354. doi:10.1186/s12909-023-04344-8

- Kim, C., Park, S. W., & Cozart, J. (2014). Affective and motivational factors of learning in online mathematics courses. British Journal of Educational Technology, 45(1), 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2012.01382.x

- Köseoglu, Y. (2015). Self-efficacy and academic achievement–A case from Turkey. Journal of Education Practice, 6(29), 131–141.

- Kundu, A., Bej, T., & Rice, M. (2021). Time to engage: Implementing math and literacy blended learning routines in an Indian elementary classroom. Education and Information Technologies, 26(1), 1201–1220. doi:10.1007/s10639-020-10306-0

- Kurbanoğlu, İ., & Akin, A. (2010). The relationships between university students’ chemistry laboratory anxiety, attitudes, and self-efficacy beliefs. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 35(8), 48–59. doi:10.14221/ajte.2010v35n8.4

- Kwet, M., & Prinsloo, P. (2020). The ‘smart’ classroom: A new frontier in the age of the smart university. Teaching in Higher Education, 25(4), 510–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1734922

- Lee, J.-Y., & Chei, M. J. (2020). Latent profile analysis of Korean undergraduates’ academic emotions in E-learning environment. Educational Technology Research & Development, 68(3), 1521–1546. doi:10.1007/s11423-019-09715-x

- Li, W., & Bai, W. (2011). Research on student participation in reflective asynchronous E-learning model. Journal of Distance Education, 25(3), 14–20.

- Li, W., Gao, W., & Sha, J. (2020). Perceived teacher autonomy support and school engagement of Tibetan students in elementary and middle schools: Mediating effect of self-efficacy and academic emotions. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 50. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00050

- Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., & Pekrun, R. (2011). Students’ emotions and academic engagement: Introduction to the special issue. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(1), 1–3. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.11.004

- Li, J., Shi, D., Tumnark, P., & Xu, H. (2020). A system for real-time intervention in negative emotional contagion in a smart classroom deployed under edge computing service infrastructure. Peer-to-Peer Networking and Applications, 13(5), 1706–1719. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12083-019-00863-8

- Lu, K., Shi, Y., Li, J., Yang, H. H., & Xu, M. (2022). An investigation of college students’ learning engagement and classroom preferences under the smart classroom environment. SN Computer Science, 3(3), 205. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-022-01093-1

- Lu, G., Xie, K., & Liu, Q. (2022). What influences student situational engagement in smart classrooms: Perception of the learning environment and students’ motivation. British Journal of Educational Technology, 53(6), 1665–1687. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13204

- MacLeod, J., Yang, H. H., Zhu, S., & Li, Y. (2018). Understanding students’ preferences toward the smart classroom learning environment: Development and validation of an instrument. Computers & Education, 122, 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.03.015

- Meng, Q., & Zhang, Q. (2023). The influence of academic self-efficacy on university students’ academic performance: The mediating effect of academic engagement. Sustainability, 15(7), 5767. doi:10.3390/su15075767

- Nie, J., Yuan, Y., Chao, X., Li, Y., & Lv, L. (2023). In smart classroom: Investigating the relationship between human–computer interaction, cognitive load and academic emotion. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 1–11. doi:10.1080/10447318.2023.2190257

- Parinsi, M. T., & Ratumbuisang, K. F. (2017). Indonesian mobile learning information system using social media platforms. International Journal of Mobile Computing and Multimedia Communications, 8(2), 44–67. doi:10.4018/ijmcmc.2017040104

- Patrick, H., Ryan, A. M., & Kaplan, A. (2007). Early adolescents’ perceptions of the classroom social environment, motivational beliefs, and engagement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(1), 83–98. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.1.83

- Pekrun, R. (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educational Psychology Review, 18(4), 315–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-006-9029-9

- Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Frenzel, A. C., Barchfeld, P., & Perry, R. P. (2011). Measuring emotions in students’ learning and performance: The achievement emotions questionnaire (AEQ). Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(1), 36–48. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.10.002

- Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., & Perry, R. P. (2002). Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educational Psychologist, 37(2), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3702_4

- Pekrun, R., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2012). Academic emotions and student engagement. In S. Christenson, A. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 259–282). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_12

- Pentaraki, A., & Burkholder, G. (2017). Emerging evidence regarding the roles of emotional, behavioural, and cognitive aspects of student engagement in the online classroom. European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning, 20(1), 1–21. doi:10.1515/eurodl-2017-0001

- Pintrich, P., & Groot, E. (1990). Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(1), 33–40. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.82.1.33

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.40.3.879

- Putwain, D. W., Wood, P., & Pekrun, R. (2022). Achievement emotions and academic achievement: Reciprocal relations and the moderating influence of academic buoyancy. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(1), 108–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000637

- Raoofi, S., Tan, B. H., & Chan, S. (2012). Self-efficacy in second/Foreign language learning contexts. English Language Teaching, 5(11), 60. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v5n11p60

- Ravaja, N., Kallinen, K., Saari, T., & Keltikangas-Järvinen, L. (2004). Suboptimal exposure to facial expressions when viewing video messages from a small screen: Effects on emotion, attention, and memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 10(2), 120–131. doi:10.1037/1076-898X.10.2.120

- Russell, J. A. (2003). Core affect and the psychological construction of emotion. Psychological Review, 110(1), 145–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.110.1.145

- Schunk, D. H., & Ertmer, P. A. (2000). Self-regulation and academic learning: Self-efficacy enhancing interventions. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 631–649). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012109890-2/50048-2

- Schunk, D. H., & Mullen, C. A. (2012). Self-efficacy as an engaged learner. In S. Christenson, A. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 219–235). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_10

- Schwarzer, R., & Born, A. (1997). Optimistic self-beliefs: Assessment of general perceived self-efficacy in thirteen cultures. World Psychology, 3(1-2), 177–190.

- Schwarzer, R., Born, A., Iwawaki, S., Lee, Y.-M., & Zhang, J. X. (1997). The assessment of optimistic self-beliefs: Comparison of the Chinese, Indonesian, Japanese, and Korean versions of the general self-efficacy scale. Psychologia: An International Journal of Psychology in the Orient, 40(1), 1–13. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01096.x

- Schweizer, K. (2011). On the changing role of Cronbach’s α in the evaluation of the quality of a measure [editorial]. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 27(3), 143–144. doi:10.1027/1015-5759/a000069

- Sevindik, T. (2010). Future’s learning environments in health education: The effects of smart classrooms on the academic achievements of the students at health college. Telematics and Informatics, 27(3), 314–322. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2009.08.001

- Skinner, E. A., & Pitzer, J. R. (2012). Developmental dynamics of student engagement, coping, and everyday resilience. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 21–44). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_2

- Tomás, J. M., Gutiérrez, M., Georgieva, S., & Hernández, M. (2020). The effects of self‐efficacy, hope, and engagement on the academic achievement of secondary education in the Dominican Republic. Psychology in the Schools, 57(2), 191–203. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22321

- Tyng, C. M., Amin, H. U., Saad, M. N. M., & Malik, A. S. (2017). The influences of emotion on learning and memory. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1454. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01454

- Tzafilkou, K., Perifanou, M., & Economides, A. A. (2021). Negative emotions, cognitive load, acceptance, and self-perceived learning outcome in emergency remote education during COVID-19. Education and Information Technologies, 26(6), 7497–7521. doi:10.1007/s10639-021-10604-1

- Van Volkinburg, H., & Balsam, P. (2014). Effects of emotional Valence and Arousal on time perception. Timing & Time Perception ( Leiden, Netherlands), 2(3), 360–378. 10.1163/22134468-00002034

- Wang, Y., Cao, Y., Gong, S., Wang, Z., Li, N., & Ai, L. (2022). Interaction and learning engagement in online learning: The mediating roles of online learning self-efficacy and academic emotions. Learning & Individual Differences, 94, 102128. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2022.102128

- Wolverton, C. C., Hollier, B. N. G., & Lanier, P. A. (2020). The impact of computer self-efficacy on student engagement and group satisfaction in online business courses. Electronic Journal of E-Learning, 18(2), 175–188. doi:10.34190/EJEL.20.18.2.006

- Xu, X. C., & Gong, S. Y. (2009). Academic emotions and its influencing factors. Advances in Psychological Science, 17(1), 92–97.

- Yang, X. (2015). A study of the academic emotions of English majors and their influencing factors in classroom environment: A case study of CBI course in a Northeastern University [ Doctoral thesis]. Shanghai International Studies University.

- Yan, D., & Guoliang, Y. (2007). The development and application of an academic emotions questionnaire. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 39(5), 852–860.

- Yu, H., Shi, G., Li, J., & Yang, J. (2022). Analyzing the differences of interaction and engagement in a smart classroom and a traditional classroom. Sustainability, 14(13), 8184. doi:10.3390/su14138184

- Zhang, Y., Hao, Q., Chen, B., Yu, H., Fan, F., & Chen, Z. (2019). Research on college students’ classroom engagement and its influencing factors in smart classroom environment—Using educational technology research method course as an example. China Educational Technology, 384, 106–115.

- Zhong, Y., & Wang, W. (2008). An empirical study on self-efficacy in English learning among non-professional students in a multimedia environment. Journal of Sichuan International Studies University, 24(6), 142–144.

- Zimmerman, B. J., Bandura, A., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1992). Self-motivation for academic attainment: The role of self-efficacy beliefs and personal goal setting. American Educational Research Journal, 29(3), 663–676. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312029003663

- Zins, J. E., Bloodworth, M. R., Weissberg, R. P., & Walberg, H. J. (2007). The scientific base linking social and emotional learning to school success. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 17(2–3), 191–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/10474410701413145