Abstract

This paper employs Mikhail Bakhtin for a dialogic reading of dialectics, conceptualising how early childhood education (ECE) teachers’ political dialogues are opened up and closed down. Explorations of ‘political dialogue’, or how teachers respond to issues they deem of political concern, is pertinent for teaching’s inherently political nature. How such encounters are opened and closed has special significance for ECE teachers, who have expressed feeling professionally and politically silenced. Guided by a philosophical framing of the contradictions and jostling interplays between dialogism’s in-betweenness and dialectic’s one-ness, excerpts are analysed from a doctoral study involving 10 Victorian, Australian ECE teachers. This framing and analysis signal the potential ramifications of a dialectical closing down of ECE teachers’ political dialogues in addition to how dialogism’s in-betweenness fosters openness. Contemplating these language strategies, the paper highlights how a silencing divisiveness may transpire, prompting a need for genuine listening in the threshold in-between the self and other.

Introduction

This paper employs Mikhail Bakhtin’s philosophy for a dialogic reading of dialectics, conceptualising how early childhood education (ECE) teachers’ political dialogues are opened up and closed down. Investigations of teachers’ political dialogues, or how this workforce responds to issues they deem of political concern, may be pertinent for all educational sectors; however, this inquiry is particularly significant for ECE teachers. To begin with, they feel professionally and politically silenced (Molla & Nolan, Citation2020). In addition, they encounter considerable political concerns, such as challenging teacher-child ratios, high-stress, limited promotional opportunities, high sector turnover, increasing workloads and generally poor working conditions (Corr et al., Citation2017; Liu & Boyd, Citation2020; Productivity Commission, Citation2011). Simultaneously, they experience being undervalued and positioned as expendable; issues that were exacerbated by the pandemic (Westbrook et al., Citation2022). The significant challenges this workforce faces mark the importance of examining how ECE teachers’ political dialogues open up or close down these debates. Whilst the insights and provocations provided by this paper are of considerable relevance to ECE teachers, they may also be of use to teachers at all levels of education.

This paper employs a Bakhtinian dialogic reading of dialectics to conceptualise and interrogate the nuanced language strategies of ECE teachers’ political dialogues, and what arises as a consequence of these encounters. This dialogising appreciates all responses as full of the speaker’s ideology and intent, encouraging contemplation of the contradictions and jostling interplays between dialectic one-ness and dialogism’s in-betweenness. Consequently, a Bakhtinian reading of Socrates, Plato, Spinoza, Hegel, Marx and Engels, as well as Vygotsky’s dialectic is offered.

To investigate this phenomenon, excerpts from a larger doctoral study investigating 10 ECE teachers’ political dialogues from an Australian-centric Facebook group are analysed. Although the initial study was prompted by concerns around ECE teachers’ hidden voices, this paper was motivated by the conflicts between the teacher participants. To conceptualise such encounters, a philosophical framework was formed to interrogate this opening up and closing down of political responses. Bringing this data to bear on the philosophical framework, offers a means to conceptualise how and why ECE teachers may feel silenced through a dialectical closing down, how the strategic intent of such a manoeuvre potentially prompts political divisiveness, and signal the role of dialogism’s in-betweenness in fostering openness, encouraging genuine listening on the threshold of the self and other.

Teaching as a political dialogue during divisive times

Teaching has been described as a political endeavour (Alford, Citation2021; Johnson, Citation2014; Khokhar, Citation2019), with all teachers’ decisions ‘political (being motivated by a person’s beliefs and/or furthering the interests of specific groups)’ (Souto-Manning et al., Citation2019, p. 68). Nuanced investigations of how ECE teachers’ political dialogues are opened up as relational co-subjective exchanges that may foster ‘ever newer ways to mean’ (Bakhtin, Citation1981, p. 346), and are closed down through a silencing of divergent worldviews is, therefore, highlighted. In recent years, political tensions appear exacerbated by the pandemic, which framed ECE teachers as expendable babysitters (Westbrook, Citation2024; Westbrook et al., Citation2022). ECE teachers across Aotearoa, Australia, United States of America and the United Kingdom have been striking in response to these political issues (Boscaini, Citation2023; Specia, Citation2023; Wiggins & Leahy, Citation2023; Will, Citation2023). Hence, there is an ongoing need to mobilise responses to ongoing political issues, exploring how they are opened up and closed down.

The aforementioned ECE issues of political concern are situated within a global rise in political polarisation (Combs, Citation2020; Hoxworth, Citation2021), indicating a wider significance of how political dialogues are opened up and closed down. Politics are increasingly framed as impassable, with right-and-left-wing ‘ideological silos’, which frame counter ideologies as ‘a threat to the nation’s wellbeing’ (Geiger, Citation2014, p. 4). Within these tensions, those with differing views can be perceived as abhorrent foes, through a dehumanising ‘othering’ (Aschwanden, Citation2020; Finkel et al., Citation2020; Higgs, Citation2018). The complex and globalised significance of this phenomena demands a philosophically nuanced relational, language investigation, that is well suited to these challenging times.

Mikhail Bakhtin is an insightful philosopher for such an undertaking given his situated epoch of struggle and political unrest. Whilst a Bakhtinian investigation of political dialogues might be considered contentious, dialogism offers an advantageous means to conceptualise and investigate teachers’ political responses as language strategies (Westbrook, Citation2024). Experiencing tumultuous times on a far greater scale, Bakhtin lived from 1895 to 1975 in Russia during the fall of the Czars, rise of the Soviet Union, and throughout Stalin’s reign of terror. Holquist (Citation1984) describes how Bakhtin knew he was ‘living in an unusual period, a time when virtually everything taken for granted in less troubled ages lost its certainty, was plunged into contest and flux…. Generations were presented with unusual dangers and unique opportunities’ (p. xv, emphasis added). Although not comparable to the Soviet Union, the current epoch also appears to present unusual dangers, including the pandemic, living crisis, Anthropocene, rise of artificial intelligence, and exacerbated ECE crises. Ever the optimist (Emerson, Citation1997), Bakhtin facilitates an investigation of the unique opportunities that may arise from such challenges (Westbrook, Citation2024).

A Bakhtinian entreaty

Bakhtinian dialogism is a relational philosophy where those, such as ECE teachers, are internally free, with a multiplicity of possible responses, whilst also being co-dependent upon their encounters with others (Frank, Citation2005). For dialogism, encounters occur on the threshold, whereby the self steps out from their views and values to consider the other’s, before stepping back to consummate their response (Neilson, Citation2000). This onto-epistemological process enables relational investigations of how ECE teachers’ political dialogues are opened up and closed down in co-subjective encounters, between the self and other. Such exchanges are ‘rich and tension-filled’ because words are not neutral or impersonal (Bakhtin, Citation1981, p. 295). They exist in other ‘people’s mouths’ and ‘contexts’ as opposed to in dictionaries, ‘serving other people’s intentions: it is from there that one must take the word, and make it one’s own’ (Bakhtin, Citation1981, p. 294). This appreciation enables nuanced language investigations of ECE teachers’ political dialogues, through an examination of populated, intentional words as relational responses. This conceptualisation facilitates an analysis of how ECE teachers alter dialogues in complex and complicated ways to further their strategic orientation; a Bakhtinian term that describes the intent and aim of a speaker’s chosen response. ECE teachers’ political dialogues are, therefore, not arbitrary. Their chosen words offer insights into their evolving worldviews and how these are opened up and closed down in their strategically orientated encounters with others.

Within threshold encounters, the self and other cannot step into another’s consciousness; insights are always refractively co-subjective, not conclusive, positivist truths, with implication for political dialoguers. Given these threshold boundaries, Neilson’s (Citation2000) Bakhtinian appreciation of political dialogues is of an ethical entreaty, continually querying,

how should I act – not because of a priori postulates or formal expectations of my duty or role – but how should I act given the imaginary but not fictional subjectivity of another who can answer me back – however radically different that subjectivity might be from my own. The question of what should I do becomes, for Bakhtin, how should I act toward this other. (p. 145)

Such dialogic entreaties affirm the ethics of how to respond. An encounter that seeks to understand the other, not to persuade, but to explore, and perhaps understand, what separates the self from the other, to learn through collective lenses (Wegerif e al., 2022).

Researchers are also brought into these thresholds (Sullivan, Citation2012). My insights into the ECE teachers’ political dialogues are my responses to their living encounters, which I meet with my co-subjectivity. I, therefore, lay no claim to conclusive, thematic or generalisable findings, but rather lay bare my interpretation of the political dialogues within the study. From these insights, I strategically aim to further discussions of this phenomena through a series of provocations, that may be of use to others in the sector. Hopefully this undertaking will prompt a further dialogic opening up of discussion surrounding this topic, as well as potential dialectic closing downs.

Dialectic and dialogic: Opening up and closing down political encounters

Whilst Bakhtinian dialogism emphasises the open, in-betweenness of existence, dialectics are philosophically entrenched in a closing down toward a single truth. Drawing upon Spinoza, Hegel, Marx, and Engels, as well as Vygotsky, White (Citation2014) tentatively describes dialectics as the seeking of ‘one-ness through the process of conflict or contradiction in or to explain concepts of the universe’ (p. 222). For Bakhtin, ‘the word dialectical…generally has pejorative overtones’ (Emerson, Citation1984, p. xxvi). Yet, in the spirit of dialogism, Bakhtin does not entirely dismiss dialectics, remaining open to these strategic orientations (White, Citation2014). In this way, he does not ‘narrow down debate by discrediting totally, or (on the other hand) by conferring exclusive authority’ (Emerson, Citation1984, p. xxxvii). Dwelling within these tensions, facilitates investigations of how ECE teachers’ strategic orientations may open up and close down ongoing co-relational exchanges. Dialogising this framework, I briefly introduce dialectic thinkers and thought, through my Bakhtinian reading, not as an exhaustive examination, but to conceptualise a means to investigate ECE teachers’ political dialogues.

Dialectics has been described as a ‘method of elimination’, whereby perceptions are tested and debated to locate their vulnerabilities and falsehood (Popper, Citation1940, p. 404); a strategic orientation that may close down ECE teachers’ political dialogues. Such one-ness, for Bakhtin is characterised as a monologue, affirming the same ideology that seeks to silence differing views and voices, reductively silencing divergent worldviews (Bakhtin, Citation1984). Wegerif et al. (Citation2022) contends Bakhtinian political dialogues are anti-democratic, due to this aversion to consensus. For ECE teachers’ responses, this monologic one-ness offers a means to investigate how strategic debating, intent on instilling a single truth, may close down political dialogues by positioning divergent worldviews as falsehoods.

However, Bakhtin, who has been described as looking in two directions at once (White, Citation2016), offers a means of appreciating how a strategic seeking of one-ness may foster an opening up of political dialogues (Sweet, Citation2016). In seeking a definitive truth, Socrates’ dialectic method propagated questions and then answers, which ought to be questioned relentlessly (Meyer, Citation1980). Such lively debate has the potential to be dialogised, if facilitating a ‘conflict of voices’ that open up to speakers’ ‘own ‘truths’’ (Bakhtin, Citation1986, p. 74). Subsequently, through the jostling of truths, ECE teachers’ political dialogues might foster a multiplicity of voices, opening up to the ‘contradictory complexity’ of ‘other-life-positions’ (Bakhtin, Citation1986, p. 74). ECE teachers’ political dialogues seeking a dialectic one-ness may, therefore, not always close down discussions, offering a ‘battle of voices’ (Bakhtin, Citation1986, p. 236). These many-voiced encounters might dialogise dialectics by rendering ‘untrue any externalizing and finalizing definition’ (Bakhtin, Citation1986, p. 59).

This dialogic entreaty is only possible when ‘no voice is done the ‘slightest violence’’ (Emerson, Citation1984, p. xxxvii). Such acts may potentially imbue a totalising victory (Bakhtin, Citation1990), which might close down ECE teachers’ political dialogues through a silencing annihilation of the other’s opposing worldviews. Emerson (Citation1984) differentiates dialectics and dialogue, stipulating

while voices “do battle” they do not die out—that is, no authority is established once and for all. Bakhtin’s prose style, I suggest, is subtly tied to this sensitivity toward coexisting authorities in the written word, and to his insistence on the inadequacy of any final hierarchy or resolution. (p xxxviii)

ECE teachers’ political dialogues that establish a resolute and vehement finalising hierarchy may, therefore, perish others’ voices, closing down encounters by strategically attempting to arrive at a conclusion.

Departing from Socrates, Plato sought dialectics as a justification and differentiation of answers to arrive at a conclusionFootnote1 (Meyer, Citation1980), a strategic orientation that may also close down ECE teachers’ political dialogues. For Plato, truth can be reached when several positions are confronted, overcoming opinion or doxa (Sfetcu, Citation2022). Dialogism cannot settle for this monologic singular, with truth split by the Russian language into istina and pravda. Istina is a universally propagated and received truth that is fixed and unified (Ballestrem, Citation1967; Sapienza, Citation2004). Conversely, pravda is each person’s unique, unitary or lived experiences of truth (Boym, Citation1994; Sapienza, Citation2004). The interanimation of these concepts enables investigations of how istina and pravda jostle in threshold encounters.

For Bakhtin, conclusive istina that seeks to overcome pravda, sometimes referred to as doxa, can delimit and objectivise dialogues (Alexander, Citation2019). This finalising can prompt a state of ‘death (nonbeing)’ due to being ‘unheard, unrecognized, unremembered’ (Bakhtin, Citation1984, p. 287). The strategic intent to reach a conclusive truth may be of particular concern to ECE teachers’ political dialogues, as they have repeatedly described themselves as being silenced and unrecognised (Fenech & Lotz, Citation2018; Molla & Nolan, Citation2020). Encouraging political dialogues, imbued with a multiplicity of voices that share the differing perspectives of the ECE community, offers a means to address the challenges this workforce faces.

Bakhtin offers polyphony as the highest form of dialogue, potentiating the in-betweenness of ECE teachers’ political dialogues. This concept has been defined as a ‘multiplicity of voices that remain distinct, never merge, and are never silenced by a more powerful majority’ (Shields, Citation2007, p. 36). For ECE teachers, polyphony may facilitate the articulation of divergent political dialogues, as diverse lived truths pravda are enabled through inclusive and empathetic interplays, enriching political discussions and fostering renewing co-becomings. Conversely, a monologic seeking of one-ness risks silencing these diverse truths. Consequently, encouraging ECE teachers’ political dialogues, in ways that embrace a polyphonic diversity of divergent lived truths, opening up to what these others may have to offer the sector and its workforce, which appears pertinent for affirming community voices.

Juxtaposing Plato’s treatment of doxa and Spinoza’s substance, is Hegel’s dialectical ‘determinate negation’ (Stewart, Citation1996, p. 57), which can result in a monologue that closes down teachers’ political dialogues. Although contentious and paradoxical (Ruddick, Citation2008), Spinoza’s singular substance (whilst among infinite attributes) is derived of God, giving rise to a form of dialectics (Lloyd, Citation2020; Lucash, Citation1995). ‘God-as-Substance is ‘expressed’ as a totality, both as Thought and as Extension’, whereby ‘the whole of reality is knowable’ (Lloyd, Citation2020, p. 197). Conversely, Bakhtin rejects monologic truth, istina, that can cast an other’s pravda as a voiceless object (Westbrook & White, CitationIn press). Such a strategic orientation may immobilise an ECE teacher’s political dialogue through a reductive closing down. Similarly, Hegel’s dialectic—an ongoing synthesis of theses and antitheses—enshrines contradictions and debate as a means of defining and determining falsehood, giving rise to a singular truth through the ‘unity of opposition’ (Maybee, Citation2020, p. 4), which silences diversity through this reductionism.

A Hegelian dialectic emphasises idealism’s thought-derived-truth, as opposed to a truth defined by external factors and realities. From this perspective, the objective and subjective are mutually inclusive, enabling reason to be reached through totality. In turn, this requires that debate can arrive at a ‘result, that only in the end is it what it truly is’ (Hegel, Citation1910, p. 11). I oversimplify Hegel’s ‘negative rationality’ (Wilhelm, 1992) as an inference of a singular truth via what it is not. In response to this, Bakhtin (Citation1986) contended ‘the unified, dialectically evolving spirit, understood in Hegelian terms, can give rise to nothing but a philosophical monologue’ (p. 26). That is to say, strategically undertaking debate and contradiction as a means of determining one truth through Hegelian negation, risks undermining ECE teachers’ political dialogues. Bakhtin contends that meaning cannot be codified to arrive at a conclusive truth, but rather, through a dialogic turn, ECE teachers’ political dialogues may be investigated for the complex, contradictory ways they are opened up and closed down, via a jostling of lived truth (pravda) and received truths (istina) at the threshold of ‘each moment’ (White, Citation2016, p. 19).

A strain of dialectics dialogism is not open to is dialectical materialism, with White (Citation2014) noting Bakhtin fundamentally rejected material forces. Marx and Engels extended on Hegelian dialectics, turning idealism ‘off its head’ (Engels & Marx, Citation1941, p. 44) by supplanting the primacy of materials over consciousness (Duquette, Citation1989). These ideas were developed by Marxism into dialectical materialism, positioning peoples as dependent on production and processes of change for consciousness and truth, with materiality as a superseding catalyst for cultural systems and values (White, Citation2014). Conversely, for Bakhtinian dialogism, communicative interplays are a source of ongoing interpretations and becomings. No materiality, person or ideology can have primacy over another, with consensus forever shifting at the threshold in-between, offering a ‘new path for political philosophy’ (Koczanowicz, Citation2016, p. 32). These ongoing communicative interplays facilitate nuanced and contradictory investigations of how ECE teachers’ political dialogues might be opened up and closed down through their strategic orientations.

In place of material dialectics, Bakhtin (Citation1981) outlined how some forms of communication, such as authoritative discourse, are strategic language devices that seek to close down dialogue. This has implications for thinking about ECE teachers’ responses. Authoritative discourse ‘relies on the authority of the individual or institution for its truth claim’ (Sullivan, Citation2012, p. 368). This infused legitimacy can be strategically employed to unify others’ values with the speakers’ worldview. This language device is ‘indissolubly fused with its authority-with political power, and institution’ (Bakhtin, Citation1981, p. 343). In other words, ECE teachers’ employing this language device strategically infuse their political dialogues with hierarchical notions and persons, positioning their responses as a ‘magisterial script’ (Bakhtin, Citation1981). Because of the in-betweenness of the self and other, who are always ‘strategic dialogue partners’ (White, Citation2021, p. 1278), there are a multitude of ways one might respond to authoritative discourse. Such possibilities affirm how ‘no conclusion is ever capable of definitively putting an end to dialogue’ (Koczanowicz, Citation2016, p. 32), enabling investigations of how ECE teachers’ political dialogues are opened up and closed down in a given time and space, whilst also acknowledging that these communions may at later points foster discussions and silences.

Vygotsky is another dialectical thinker who has been tied to and in tension with Bakhtinian dialogism (White, Citation2014), with implications for conceptualising how ECE teachers’ political dialogues may be opened up and closed down. Informed by dialectical materialism, and Hegel’s notion of totality (Sullvian; 2010; White, Citation2014), Vygotsky proposed children’s material society and culture as transformative for their thinking, interactions and language (Sullivan, Citation2012). Through this lens, the development of consciousness occurs via organisational systems between the outer material world, and its social rules, with inner consciousness (White, Citation2014). In contrast to this, in Bakhtinian threshold encounters, dialoguers choose the extent to which they open up to the other’s ideas and values. This dialogic framing emphasises the significance of how lived truth pravda encounters and ingests received truth istina (Sullivan, Citation2012). This interplay affects how ECE teachers choose to integrate and respond to authoritative discourses and a monologic seeking of one-ness. I draw from my doctoral research to investigate these phenomena.

Method

Having offered a philosophical framing that conceptualises how ECE teachers’ political dialogues may open up and close down, this framing is now applied to excerpts from a doctoral study. This paper expands on initial efforts to investigate the strategic orientations of ECE teachers’ political dialogues, or how they responded to issues of political concern, shifting the framing and analysis to examine the strategic orientations of dialogic in-betweenness and dialectic one-ness. The significance of such an undertaking is to more richly interrogate the clashes and opportunities that eventuated within the ECE teachers’ political dialogues. These insights facilitate provocations that may be of use to ECE teachers and fellow community members in how they consider and utilise language strategies that open and close down political concerns, such as feeling silenced and expendable (Molla & Nolan, Citation2020).

Situated within an ECE Facebook groupFootnote2 a recruiting post was shared in a Phase One space (beyond the scope of this paper; see Westbrook, Citation2024), inviting ECE teachers to share their political dialogues, in a newly created Facebook Group. Phase Two was active from 31 September to 31 October 2020. As the researcher in this space, I engaged in discussions with these teachers to dialogise insights from the first phase, and encourage the sharing of their political dialogues, based on self-determined participation. Phase Two was capped at 10 members, on a first-come-first-serve basis, following Taylor et al. (Citation2015) advice. This number is optimal for ethical management and facilitation. Ethics for this research was gained from RMIT University and included the informed ethical consent of all participant data. I initially imagined the second phase would be a community space, affirming ECE teachers’ voices; however, it soon became apparent that it was a heated and contested space for the ECE teachers’ political dialogues, and how these were opened and closed down. This contestation encouraged a philosophical reconceptualisation of this phenomenon, which provides a tool for ECE teachers to (re)consider how to foster the in-betweenness of their political dialogues.

An opening up and closing down of political dialogues

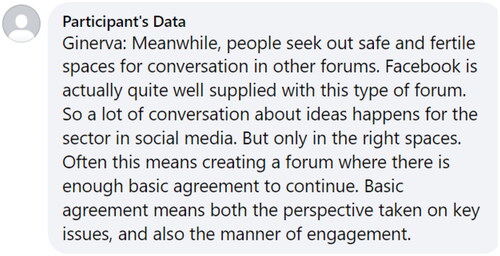

Although the second research phase suggested an opening up to the in-betweenness of the ECE teachers’ political dialogues, there also appeared to be an increasing dialectic closing down. Emphasising ways in-betweenness can be fostered, GinevraFootnote3 illustrates an example of how encounters were opened up: ‘safe and fertile …conversations… So a lot of conversations about ideas happen for the sector in social media’ (, emphasis added). The strategic dimensions included ‘enough basic agreement’, whereby ‘both perspectives taken on key issues, and also the manner of engagement’ (, emphasis added). The mentioning of multiple ‘perspectives’ appears to emphasise dialogism’s attempt to understand the other’s political dialogue through their lived pravda; an in-betweenness that may open up to the self and other by rejecting resolution, thus consensus by making space for divergent ideologies and voices. In mentioning the ‘manner of engagement’, this response could implicate the Bakhtinian assertion that dialogue can only flourish in coordinates where no violence is done to another’s dialogue. This potential damage implicates how dialectic strategic orientations that objectivise, and thus silence a teacher’s political dialogue, may close down encounters.

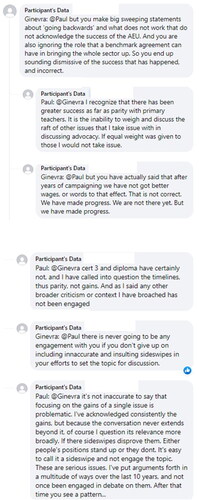

This closing down through a strategic seeking for one-ness can be found across several exchanges between two teachers’ political dialogues, whose opposing worldviews attempted to establish the ‘right’ way to respond. and illustrate these strategic orientations as Ginevra and Paul’s political dialogues position their ideology as correct, attempting to transform the other’s. Figure 2’s thread was situated against prior posts where Paul’s political dialogues criticised union and left-wing strategic orientations, stating these were ‘a complete waste of time’ (8 October 2020, emphasis added), impeding the possibility of opening up to the other’s political dialogue. In response, Ginevra’s post criticised Paul’s political dialogue as failing to acknowledge left wing politics and union achievements ‘by making big sweeping statements…that does not acknowledge the success of the AEU [Australian Education Union]’ (, emphasis added). Such replies infer Paul’s dialectic strategic intent as monologically closed to the other, potentially immobilising the complexities of Ginevra’s worldview and the possibilities that might arise from her strategic orientation.

These encounters appear to increasingly close down toward a silencing of and refusal to hear the other’s worldview. This interaction may have implications for a wider closing down and hostilities that have been described as fostered in such spaces (Tucker et al., Citation2018). Other dialectic orientations, intent on one-ness that seeks to determinately negate the other’s pravda, arrive at a wholly knowable istina, reality, may also silence truth pravda. With each speaker doing so, the political dialogue can be observed to close down due to positioning of their worldview beyond reproach, thus not open to the other’s.

Meanwhile, Ginevra’s previous posts were also inferred as strategically attempting to imbue a monologic authoritative discourse. Placing the teachers’ union beyond reproach fosters the hierarchies of authoritative discourse, which is not open to divergent ideologies, closing down any in-betweenness for a one-ness orientation. Bakhtin (Citation1981) described how authoritative discourse is an ‘indivisible mass; one must either totally affirm it, or totally reject it. It is indissolubly fused with its authority - with political power, an institution, a person - and it stands and falls together with that authority’ (p. 343, emphasis added). Ginevra’s prior political dialogue had called for ‘solidarity and loyalty’ (30 October 2020, emphasis added) with the union. This orientation appears to ‘totally affirm’ the union in ways that disallowed an opening up of discussions, entrenching a ‘correct way’ to respond to political issues and establishing a dialectic. Notably, this strategy was positioned as offering an unparalleled means for the ECE teacher’s political dialogues exacting change, with this being particularly pertinent for a silenced and voiceless workforce (Westbrook, Citation2023a). Closing down divergent dialogue can objectivise and delimit peoples and topics. Consequently, even political dialogues that are as supportive of the sector as unionisation (see Bussey et al., Citation2022) may foster a silencing voicelessness, if strategically oriented to a dialectic one-ness.

Further incorporating a dialectic strategic intent, Ginevra and Paul’s political dialogues can be read as attempting to negate one another’s worldview. Paul’s political responses persisted in asserting that the union lacks a comprehensive advocacy approach, contradicting Ginevra’s earlier posts about the effect union wins ‘have in bringing the whole sector up’ (, emphasis added). In response, Ginevra labelled Paul’s position as ‘dismissive of the success that has happened’ (, emphasis added). Paul’s dialectic strategic orientation is observed in his response, ‘either people’s positions stand up or they don’t’ (, emphasis added). This reply presents a dialectic conflict, with each reply further cementing the individual’s worldview and in turn attempting to ‘disprove’ the other’s as ‘incorrect’ (, emphasis added). Bakhtin (Citation1986) stated ‘dialectics is born of dialogue in order to return to dialogue on a higher level’ (p. 162). Yet, by refusing to open up to dialogism’s in-betweenness the encounters in (and ) do not reach this ‘higher level’, as their strategic orientations attempt to conquer the other’s worldview, negating an openness to explore divergent lived truth pravda. This refusal to be open to in-betweenness sacrifices an exchange of views, values and beliefs, and the potential to pave the way for new meanings and dialogues (Bakhtin, Citation1981).

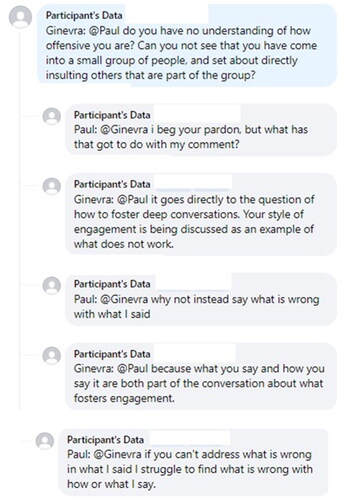

Engaging in opposing dialectic one-nesses that contradicted the other, the ECE teachers’ political dialogues precipitated a finalising closing down of encounters. Paul’s posts described, ‘I've presented arguments in various ways over the past decade without ever being engaged in a debate about them’ (, emphasis added). This statement suggests that, due to the absence of open political dialogue, Paul’s replies have been unheard and thus objectivised. Ginevra’s replies also noted that dialectics, which finalise the other, cease ‘deep conversations. Your style of engagement is being discussed as an example of what does not work’ (, emphasis added). Implicating such strategic orientations, Paul’s response asserts, ‘if you can’t address what is wrong in what I said, I struggle to find what is wrong with how or what I say’ (, emphasis added). Such encounters suggest the futility of political dialectics to open up discussion, as they tend to close down interactions through a strategic silencing of divergent ideologies.

A consequence of dialectic strategic orientations that repeatedly sought to highlight the falsehood of the other’s political dialogue, was the way this finality prompted frustration, which further closed down the encounter. Indicating this frustration, Ginevra’s response labels Paul’s authoritative dialectic posts ‘offensive’ and ‘directly insulting others’ (, emphasis added). As strategic orientations assert a single ‘right way’, this fostered a sense that the ECE teacher’s political dialogues were being increasingly silenced. The apparent dissatisfaction and potential resentment of a strategic seeking of totalising consensus highlights the limitations and consequences of dialectics, as well as how such orientations may close down political encounters. These dynamics illustrate one way in which political division is fostered. Bakhtin (1984) explained how the ‘hero always seeks to destroy that framework of other people’s words about him [or her] that might finalize and deaden [them]’ (p. 59). Similarly, the ECE teachers’ political dialogues appeared to strategically attempt to destroy the closed dialectic to have their truth pravda heard; however, by virtue of their dialectic intent, each is implicated as curtailing open-ended encounters that may facilitate ‘ever newer ways to mean’ (Bakhtin, Citation1981, p. 346). Consequently, attempting to shift the other’s ideology left little to no room for listening and considering another’s truth pravda.

Potential insights and provocations

These ECE teachers’ strategic orientation, asserting the ‘correctness’ of their own political dialogue, left little space for listening and considering the truth pravda of the other in the above excerpts. As Bakhtin (Citation1986) highlights, ‘the soil of monastic idealism is the least likely place for a plurality of unmerged consciousnesses to blossom’ (p. 26). Because of the strategic seeking of one-ness, it appeared the ECE teachers felt their political dialogue was constrained and objectified. Therefore, this attempted closing down meant that little could blossom beyond the encounters. Such discussions indicate why ECE teachers may feel silenced and unrecognised, given the strategic intent of dialectical one-ness, which sought to negate a plurality of polyphonic truth pravda. Consequently, one-ness strategic orientations may foster reductive discussions bound to a ‘monologically perceived and understood world; there is no presumption of a plurality of equally valid consciousnesses, each with its own world’ (Bakhtin, 1984, p. 7). In other words, dialectic ideologies and worldviews narrow what responses are possible. Divergent views and avenues are conceivably advantageous for ECE’s multiple community members and ongoing advocacy battles, such as the sector’s ongoing fight for recognition, fair pay and improved working conditions, potentially offering diverse responses

This analysis identifies how political exchanges can become divisive when closed down by dialectics because they exacerbate the polarity that characterises the current epoch (Finkel et al., Citation2020). If ECE teachers are seeking language strategies to open up responses to current crises, such as challenging teacher-child ratios, high sector turnover and increasing workloads, a response is problematising orientations that seek to persuade the other toward the self’s political ideology. Whilst seeking to point out the falsehoods and contradictions may prompt further dialogue—doing battle through a plurality of views—this orientation may also prompt frustration and a silencing that closes down discussions. When considering the challenges the ECE sector faces, the ways in which colleagues make space to hear, and perhaps affirm, one another’s political dialogues is clearly significant. By contrast, strategic orientations that attempt to coerce the other appear futile because of their tendency to impede polyphony, through their polarising effects and silencing of the diversity of lived truths.

What arose from the ECE teachers’ dialectic strategic orientations suggests the need for political dialogues that embrace in-betweenness; being open to listen to the other’s political dialogue, as a means to understand their lived truth pravda, and the dimensions prompting their worldviews. Such an entreaty does not dictate the self and other agree. Instead, this provocation encourages a polyphonic diversity of worldviews and consideration of what this multiplicity of ideologies might have to offer. ECE teachers have been characterised by enduring stereotypes of a white, feminised workforce, solely in service of others (Westbrook, Citation2023a), which fosters a discourse of stagnation. The ‘dynamic and ever-evolving ECE sector (May, 2009), and the nuanced responses from teachers (Oosterhoff et al., Citation2020), make such stagnation unlikely’ (Westbrook, Citation2023a, p. 75). Consequently, encouraging a plurality of polyphonic ECE teacher political dialogues may better reflect the present complexities of the ECE sector and its workforce.

Subsequently, even ECE teacher political dialogues deemed inconvenient are positioned as having value, enabling tensions that speak to multiple lived experiences, and worldviews, which might otherwise be silenced or unheard. This appeal emphasises the importance of listening to others’ responses, as a means of fostering strategies and spaces, fertile with divergent practitioners’ rich ideologies and truth pravda. This provocation runs counter to a focus on speaking up, which is potentially contradictory for a workforce that feels silenced (Molla & Nolan, Citation2020); however, it is a provocation that may alleviate feelings of being unheard, by encouraging fellow community members to actively engage in listening in open ways. Consequently, opening one’s political dialogues up to one another within threshold encounters may enable richer ideological co-becomings.

In keeping with these insights, the provocations offered are reconceptualised as a series of tangible entreaties. These points offer actionable practices ECE teachers might pursue to foster political dialogues, strategically orientated toward dialogic in-betweenness:

Seek to understand the perspective of the other, and how their worldview is formed through their time and space, as opposed to attempting to convince or point out the flaws in their lived truth.

Consider what the political dialogue of the other has to offer, even if inconvenient or divergent from the self’s ideology.

Foster spaces and encounters that enable a polyphonic plurality of unmerged voices, to equally respond. This is achievable if not supplanting a single political dialogue as authoritative.

Reflect on how distinct, polyphonic voices might problematise and improve ECE discourses through the affirmation of a plurality of political dialogues, as well as how these interplays might facilitate co-becomings.

Concluding thoughts

In this paper, a Bakhtinian dialogic examination of dialectic one-ness has been undertaken, drawing insights from the analysis of doctoral data on ECE teachers’ political dialogues. The investigation has unpacked how dialectics tends to contribute to the closing down of political encounters, while dialogism’s in-betweenness may foster an opening up of relation co-becomings. Strategic orientations that close down discussions, via the pursuit of dialectic one-ness and the affirmation of one’s own worldview, can lead to a sense of finality, being silenced, unheard, and further entrench divisions. The subsequent provocations seek to offer strategies to resist this closing down

The provocations underscore the value of genuine listening within political dialogues, emphasising the importance of engaging with in-betweenness in the threshold between the self and other. The strategic intent to convince others of a ‘correct’ one-ness of response has been questioned, advocating instead for orientations that seek a better understanding of the political dialogue of others, rooted in their truth pravda. Additional provocations are offered regarding the placing of one’s political worldview into a state of dialogic openness and self and other in-betweenness. This involves resisting the temptation to assert one’s ideologies as an absolute truth (istina) that strategically seeks an affirming one-ness, encouraging an openness to the other’s lived truth (pravda) and what this may have to offer. Situated in early childhood education, this paper provides further insight into how teachers navigate political issues, and an analysis of how different strategic orientations open up and/or close down political discussion.

Acknowledgements

I extend my deepest gratitude to the teacher participants who gave their time to be part of this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Platonic dialogues also foster an opening up of discussions as they are driven by questions, to which no ‘stable’ answer is offered (Clay, Citation2010), further prompting considerations of how dialectics can prompt dialogues.

2 The selection of Facebook groups as a research site, and the impact this may have had on the political dialogues, is beyond the scope of this article, although is explained in depth in Westbrook (Citation2023b, Citation2024).

3 This, and all other teacher participant names are anonymising pseudonyms.

References

- Alexander, R. (2019). Whose discourse? Dialogic Pedagogy for a post-truth world. Dialogic Pedagogy: An International Online Journal, 7, E1–E19. https://doi.org/10.5195/dpj.2019.268

- Alford, J. (2021). Opinari: Teachers as agents of change: You don’t have to be a detective to be a special agent. Practical Literacy: The Early and Primary Years, 26(1), 4–5. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.666333703790942

- Aschwanden, C. (2020). Why hatred and othering of political foes has spiked to extreme levels. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-hatred-and-othering-of-political-foes-has-spiked-to-extreme-levels/

- Bakhtin, M. (1981). The dialogic imagination: Four essays (C. Emerson, Ed.; M. Holquist & C. Emerson, Trans.). University of Texas Press.

- Bakhtin, M. (1984). Rabelais and his world (H. Iswolsky, Trans.; 1st ed.). Indiana University Press.

- Bakhtin, M. M. (1986). Speech genres and other late essays (C. Emerson & M. Holquist, Eds.; V. W. McGee, Trans.; 1st ed.). University of Texas Press.

- Bakhtin, M. M. (1990). Art and answerability: Early philosophical essays (M. Holquist, Ed.; V. Liapunov, Trans.; 1st ed.). University of Texas Press.

- Ballestrem, K. G. (1967). The Soviet concept of truth. In E. Laszlo (Ed.), Philosophy in the Soviet Union: A survey of the mid-sixties (pp. 30–48). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-7539-5_3

- Boscaini, J. (2023, November 9). Thousands of SA teachers rally for better pay, conditions at second strike in months. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-11-09/south-australia-teachers-strike-reject-government-pay-offer/103082966

- Boym, S. (1994). Common places: Mythologies of everyday life in Russia. Harvard University Press.

- Bussey, K., Henderson, L., Clarke, S., & Disney, L. (2022). The role of the Australian Education Union Victoria in supporting early childhood educators during a global pandemic. In L. Henderson, K. Bussey, & H. B. Ebrahim (Eds.), Early childhood education and care in a global pandemic (pp. 181–195). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003257684-14

- Clay, D. (2010). Platonic questions: Dialogues with the silent philosopher. Penn State Press.

- Combs, J. (2020). Seven tips for political dialogue. University of Dayton. https://udayton.edu/blogs/dialoguezone/20-03-09-seven-tips-for-political-dialogue.php

- Corr, L., Cook, K., LaMontagne, A. D., Davis, E., & Waters, E. (2017). Early childhood educator mental health: Performing the ‘National quality Standard’. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 42(4), 97–105. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.355099924274238

- Duquette, D. A. (1989). Marx’s idealist critique of Hegel’s Theory of society and politics. The Review of Politics, 51(2), 218–240. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0034670500048099

- Emerson, C. (1984). Introduction. In Problems of Dostoevsky’s poetics. University of Minnesota Press. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb.08865

- Emerson, C. (1997). The first hundred years of Mikhail Bakhtin. Princeton University Press.

- Engels, F., & Marx, K. (1941). Ludwig Feuerbach & the outcome of classical German philosophy. International Publishers Co.

- Fenech, M., & Lotz, M. (2018). Systems advocacy in the professional practice of early childhood teachers: From the antithetical to the ethical. Early Years, 38(1), 19–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2016.1209739

- Finkel, E. J., Bail, C. A., Cikara, M., Ditto, P. H., Iyengar, S., Klar, S., Mason, L., McGrath, M. C., Nyhan, B., Rand, D. G., Skitka, L. J., Tucker, J. A., Van Bavel, J. J., Wang, C. S., & Druckman, J. N. (2020). Political sectarianism in America. Science (New York, N.Y.), 370(6516), 533–536. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abe1715

- Frank, A. W. (2005). What is dialogical research, and why should we do it? Qualitative Health Research, 15(7), 964–974. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305279078

- Geiger, A. (2014, June 12). Political polarization in the American public. Pew Research Center - U.S. Politics & Policy. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2014/06/12/political-polarization-in-the-american-public/

- Hegel, G. W. F. (1910). The phenomenology of mind. S. Sonnenschein.

- Higgs, R. (2018). Ideology and political divisiveness. The Independent Review, 22(4), 638–640.

- Holquist, M. (1984). Prologue. In Rabelais and his world (1st ed., pp. xiii–xxiii). Indiana University Press.

- Hoxworth, L. (2021, February 1). Is constructive political dialogue possible in 2021? UVA Today. https://news.virginia.edu/content/constructive-political-dialogue-possible-2021

- Johnson, J. E. (2014). Play provisions and pedagogy in curricular approaches. In E. Brooker, M. Blaise, & S. Edwards (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of play and learning in early childhood (pp. 180–191). Sage Publications. http://web.a.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.lib.rmit.edu.au/ehost/ebookviewer/ebook/bmxlYmtfXzgwMTYwNV9fQU41?sid=b32a8c0d-57bb-46b8-97a5-657c0d17a5c7@sessionmgr4007&vid=0&format=EK&lpid=navpoint-26&rid=0

- Khokhar, R. (2019). Analysis of representation in children’s picture books. http://hdl.handle.net/10315/40939

- Koczanowicz, L. (2016). Between understanding and consensus: Engaging Mikhail Bakhtin in Political thinking. In K. Jezierska & L. Koczanowicz (Eds.), Democracy in dialogue, dialogue in democracy: The politics of dialogue in theory and practice (pp. 21–36). Taylor & Francis Group.

- Liu, Y., & Boyd, W. (2020). Comparing career identities and choices of pre-service early childhood teachers between Australia and China. International Journal of Early Years Education, 28(4), 336–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2018.1444585

- Lloyd, G. (2020). Reconsidering Spinoza’s ‘rationalism’. Australasian Philosophical Review, 4(3), 196–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/24740500.2021.1962647

- Lucash, F. (1995). Spinoza’s dialectical method. Dialogue, 34(2), 219–236. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0012217300014682

- Maybee, J. E. (2020). Hegel’s dialectics. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2020/entries/hegel-dialectics/

- Meyer, M. (1980). Dialectic and questioning: Socrates and Plato. American Philosophical Quarterly, 17(4), 281–289.

- Molla, T., & Nolan, A. (2020). Teacher agency and professional practice. Teachers and Teaching, 26(1), 67–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2020.1740196

- Neilson, G. (2000). Looking back on the subject: Mead and Bakhtin on reflexivity and the political. In C. Brandist & G. Tihanov (Eds.), Materializing Bakhtin (pp. 142–163). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230501461

- Oosterhoff, A., Oenema-Mostert, I., & Minnaert, A. (2020). Constrained or sustained by demands? Perceptions of professional autonomy in early childhood education. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 21(2), 138–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949120929464

- Popper, K. R. (1940). What is dialectic? Mind, XLIX(194), 403–426. https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/XLIX.194.403

- Productivity Commission. (2011). Early childhood development workforce study. Australian Government Productivity Commission.

- Ruddick, S. (2008). Towards a dialectics of the positive. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 40(11), 2588–2602. https://doi.org/10.1068/a40274

- Sapienza, F. (2004). Mikhail Bakhtin, Vyacheslav Ivanov, and the rhetorical culture of the Russian third renaissance. Philosophy and Rhetoric, 37(2), 123–142. https://doi.org/10.1353/par.2004.0018

- Sfetcu, N. (2022). Plato, The Republic: On justice – dialectics and education. MultiMedia Publishing.

- Shields, C. M. (2007). Bakhtin primer. Peter Lang.

- Souto-Manning, M., Rabadi-Raol, A., Robinson, D., & Perez, A. (2019). What stories do my classroom and its materials tell? Preparing early childhood teachers to engage in equitable and inclusive teaching. Young Exceptional Children, 22(2), 62–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096250618811619

- Specia, M. (2023, March 15). Teachers join wave of public service strikes as U.K. unveils budget. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/15/world/europe/uk-teachers-strike.html

- Stewart, J. (1996). Hegel’s Doctrine of determinate negation. Idealistic Studies, 26(1), 57–78. https://doi.org/10.5840/idstudies19962611

- Sullivan, P. (2012). Qualitative data analysis using a dialogical approach. Sage.

- Sweet, D. R. (2016). Star wars in the public square: The clone wars as political dialogue. McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers.

- Taylor, S., Bodman, S., & Morris, H. (2015). Politics, policy and teacher agency. In D. Wyse, R. Davis, P. Jones, & S. Rogers (Eds.), Exploring education and childhood: From current certainties to new visions (pp. 157–170). Routledge.

- Tucker, J., Guess, A., Barbera, P., Vaccari, C., Siegel, A., Sanovich, S., Stukal, D., & Nyhan, B. (2018). Social media, political polarization, and political disinformation: A review of the scientific literature. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3144139

- Wegerif, R., Schinkel, A., & Yacek, D. (2022). Beyond democracy: Education as design for dialogue. In J. Culp, J. Drerup, & I. de Groot (Eds.), Liberal democratic education: A paradigm in crisis (pp. 157–179). Brill. https://doi.org/10.30965/9783969752548_010

- Westbrook, F. (2024). Crisis inciting carnivalesque: Early childhood teachers’ political strategies. Policy Futures in Education, 0(0), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/14782103241226518

- Westbrook, F. (2023a). Reconceptualising early childhood teachers’ responses as political dialogues. Knowledge Cultures, 11(3), 60–81. https://doi.org/10.22381/kc11320234

- Westbrook, F. (2023b). How to analyse emojis, gifs, embedded images, videos, and urls: A Bakhtinian methodological approach. Video Journal of Education and Pedagogy, 1–25.

- Westbrook, F., Redder, B., & White, E. J. (2022). A ‘quint-essential(ised)’ ECE workforce: Covid19 and the exploitation of labour. In L. Henderson, H. Ebrahim, & K. Bussey (Eds.), Early childhood education and care in a global pandemic: How the sector responded, spoke back and generated knowledge (pp. 196–210). Routledge.

- Westbrook, F., & White, E. J. (In press). Whose truth?: A dialogic interplay with online political dialogue(s). Philosophy of Education, 80(1).

- White, E. J. (2014). Bakhtinian Dialogic and Vygotskian Dialectic: Compatabilities and contradictions in the classroom? Educational Philosophy and Theory, 46(3), 220–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2011.00814.x

- White, E. J. (2021). Mikhail Bakhtin: A two-faced encounter with child becoming(s) through dialogue. Early Child Development and Care, 191(7-8), 1277–1286. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2020.1840371

- White, E. J. (2016). Introducing dialogic pedagogy: Provocations for the early years. Routledge.

- Wiggins, A., & Leahy, B. (2023, November 21). Teachers’ strike ‘biggest in NZ education history’, Minister seeks solutions. NZ Herald. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/teacher-strikes-nz-maps-show-locations-of-marches-schools-closed/FP3MF5YCFNHOTMF2A2BTXSDGPI/

- Will, M. (2023, October 30). Teacher strikes, explained: Recent strikes, where they’re illegal, and more. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/teacher-strikes-explained-recent-strikes-where-theyre-illegal-and-more/2023/10