Abstract

Environmental governance of transnational corporations is a global challenge. On one hand, these corporations can contribute to environmental protection through ecofriendly technologies and equipment. On the other hand, their activities can lead to environmental degradation and pollution. This article explores China’s due diligence legislation for environmental governance, including historical perspectives and future prospects. Chinese administrative law, relevant regulations, and the guidelines issued by Chinese trade associations are included.

© 2024 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

Governance of transnational corporations (TNCs) is a global challenge. Although international cooperation has produced agreements to enhance the responsible business conduct of TNCs in areas such as environmental protection and other human rights,Footnote1 the level of goals achieved to date through cooperation seems to be insufficient. In recent years, the United States and the European countries have launched campaigns for new laws that hold companies accountable for human rights and environmental abuses in their global operations and supply chains.Footnote2 Under these laws, companies would be required to conduct due diligence in relevant areas.

As the world’s third-largest country, China, which hosts a substantial number of TNCs, has recently shifted its attention toward the extraterritorial governance of these corporations. So far, several legal measures, including guidelines and regulations issued by trade associations and China’s Ministry of Commerce, have been taken or are under discussion in China. Relevant scholars and government officials have also begun to discuss the need for enacting a specific law that mandates due diligence for environmental protection in TNCs. The Chinese government appears to be determined to gradually enhance the governance of its TNCs. At present, the Chinese government appears to be unwilling to accept mandatory due diligence obligations concerning human rights except for environmental issues. The legal measures implemented by China regarding the governance of TNCs have been criticized for their insufficiency.Footnote3

This article aims to provide a comprehensive exploration of China’s due diligence legislation for environmental governance on TNCs, examining both historical perspectives and future prospects. The analysis encompasses various aspects, including the examination of Chinese administrative law and relevant regulations to identify official channels through which the government can intervene in the governance of Chinese TNCs. Moreover, an investigation into the guidelines issued by Chinese trade associations is conducted. Additionally, semistructured interviews were conducted with two in-house lawyers employed by Chinese TNCs operating in overseas markets to explore the conduct of Chinese TNCs in practice.

In the subsequent section, the evolution of due diligence legislation for TNCs is presented. The second section sheds light on the legal measures implemented or proposed by Chinese authorities and trade associations to regulate the environmental practices of TNCs. Moving forward, the third section critically analyzes the key features of due diligence legislation for TNCs in China. Finally, the fourth section provides an insightful assessment of the future development of the Chinese model.

Evolution of Due Diligence Legislation for Transnational Corporations

TNCs are defined as “incorporated or unincorporated enterprises comprising parent enterprises and their foreign affiliates”Footnote4 and play important roles in improving worldwide economic development. TNCs have both positive and negative effects on the environment. On one hand, they can contribute to environmental protection through the production and provision of ecofriendly technologies and equipment.Footnote5 On the other hand, their activities may lead to environmental degradation and pollution issues.Footnote6 Therefore, it is crucial to enhance the governance of TNCs, as proper corporate governance can help mitigate the negative environmental impact caused by their operations.Footnote7 The regulations governing corporate governance can also be applied to TNCs.

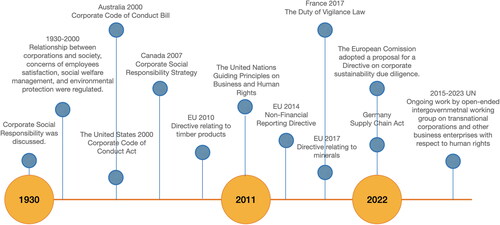

The modern understanding of corporate social responsibility (CSR) can be traced back to the 1930s, when the social responsibility of the private sector began to be discussed.Footnote8 Over time, the scope of CSR expanded to encompass the relationships between corporations and society, concerns regarding employee satisfaction, social welfare management, and environmental protection.8 Since 2011, there has been an emphasis on CSR addressing the latest social expectations by generating shared value as a primary business objective.Footnote9 Meanwhile, the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) were established, recognizing CSR at the international level and leading to its regulation in more countries. Furthermore, the UNGPs introduced human rights due diligence, which requires companies to identify, prevent, or mitigate actual or potential adverse human rights and environmental impacts. Subsequently, there were extensive deliberations on the enactment of various national regulations pertaining to due diligence, often labeled as “Corporate Code of Conduct,” “Due Diligence Law,” or “Supply Chain Act.” These regulations are designed to foster responsible business conduct and impose accountability on companies for their social and environmental impacts. Despite numerous prior attempts meeting with limited success, a notable shift occurred in the 2010s, with due diligence laws and supply-chain acts gaining traction and being implemented in several European countries.

In 2000, the United States introduced in the House of Representatives the Corporate Code of Conduct Act,Footnote10 which was one of the earliest attempts at due diligence legislation. This code mandates that companies with more than 20 employees in foreign countries must implement the code, either directly or through subsidiaries, subcontractors, affiliates, joint ventures, partners, or licensees (Section 3). The code includes requirements such as providing safe and healthy workplaces, ensuring fair employment practices, and upholding responsible environmental protection measures. To enforce compliance, the code stipulates that domestic authorities should prioritize entities that adopt and enforce the code, terminating contracts with noncompliant entities (Section 4). Additionally, the United States should establish a private right of action to investigate alleged violations of code compliance (Section 5).

Similarly, in Australia, the Corporate Code of Conduct Bill 2000 (Cth) was introduced in the Australian Senate on 6 September 2000. This code sets standards of conduct for Australian corporations engaged in business activities overseas. It also regulates reporting requirements and includes provisions for enforcement.Footnote11

In Canada, an Advisory Group recommended the development of a corporate social responsibility framework for Canadian extractive sector companies in 2007.Footnote12 In 2009, the Canadian government issued a policy regarding corporate social responsibility strategy for the Canadian international extractive sector. This policy proposed that Canada’s Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade and Natural Resources should regulate international corporate social responsibility performance guidelines for Canadian TNCs and establish an Office of the Corporate Social Responsibility Counsellor.

However, these early-stage due diligence initiatives were either unsuccessful or rejected by the relevant Parliaments. The reasons for the failures can be attributed to several factors. First, two decades ago, there was not a particularly high level of public awareness regarding the necessity of enhancing due diligence regulations for TNCs. Second, certain provisions within pertinent bills were overly stringent. As highlighted in the “Report on the Corporate Code of Conduct Bill 2000” issued by the Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia, the bill aimed to regulate a substantial number of corporate entities, potentially imposing a “heavy burden” on both companies and governments. Despite these challenges, these early legislative attempts are commendable and offer valuable insights for subsequent legislative endeavors.

Starting from the 2010s, several European countries have increasingly adopted due diligence laws to establish legally binding obligations for parent companies to identify and prevent adverse human rights and environmental impacts resulting from their own activities and the activities of the companies under their control. Notable examples include the Duty of Vigilance Law in France (2017)Footnote13 and the Supply Chain Act in Germany (2023).Footnote14

Generally, there are three generations of regulation in this regard (). The first generation, beginning with the European Union nonfinancial reporting directive in 2014, focused on due diligence reporting obligations.Footnote15 Another example is the UK Modern Slavery Act of 2015. The second generation, spanning roughly from 2010 to 2017, introduced comprehensive due diligence obligations, including risks identification, prevention actions, and mitigation measures. Examples from this period include European Union directives related to mineralsFootnote16 and timber products.Footnote17 The emerging third generation of laws, commencing with the Duty of Vigilance Law in France (2017), connects due diligence obligations to corporate liability and possesses binding features. Currently, international efforts are underway to establish an internationally binding instrument.Footnote18

Figure 1. Visual history of due diligence laws.

Source: Developed by the author based on literature review.

Considering these developments, it is crucial to explore how China enhances the governance of its TNCs through the adoption of due diligence regulations.

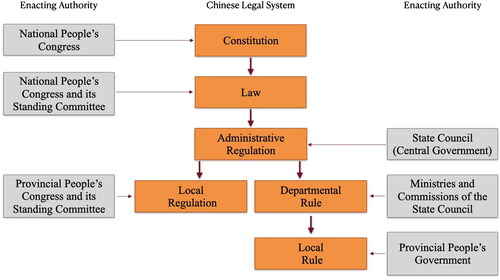

The legal framework in China boasts a rich historical tradition characterized by distinctive features. The recent amendment to the Legislation Law of the People’s Republic of China in 2023 delineates the authority of the Legislature and governments to promulgate a spectrum of legal instruments, including laws, administrative regulations, local regulations, and rules, each wielding distinct influence over societal governance, as shown in . The apex legislative bodies, the National People’s Congress and the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, possess the prerogative to enact and amend laws, endowing them with the highest legal authority. Simultaneously, the State Council is empowered to formulate administrative regulations, specifically for matters necessitating their elucidation in tandem with the provisions of laws or those falling within the purview of the State Council’s public administration functions and powers. Administrative regulations derive their efficacy from the legal framework. At the regional level, the People’s Congress and its Standing Committee within a province are authorized to promulgate local regulations, wielding jurisdiction solely within their respective administrative domains. Additionally, ministries and commissions of the State Council possess the authority to devise rules within their defined competencies, denoted as departmental rules. Similarly, provincial people’s governments may formulate rules applicable within their respective regions, termed local rules. The validity of these rules is contingent upon compliance with overarching laws and administrative regulations. It is imperative to underscore that notwithstanding the differences in nomenclature and jurisdiction, all laws, administrative regulations, and rules carry legal binding force. Their enforceability extends to judicial proceedings, affirming the comprehensive legal structure in China.

Figure 2. Hierarchical effectiveness of the Chinese legal system and enacting authorities.

Source: Developed by the author based on the Legislation Law of the People’s Republic of China.

Moreover, ministries and commissions within the State Council possess the authority to promulgate regulatory documents, falling under the category of soft laws. Unlike hard laws, which are legally binding and enforceable in court, soft laws, such as regulatory documents, are nonbinding regulatory instruments. These documents, while lacking legal enforceability, assume a voluntary character and wield diminished legal impact compared to laws sanctioned by the National People’s Congress, administrative regulations promulgated by the State Council, and departmental rules enacted by the affiliated institutions of the State Council. Despite their nonbinding nature, regulatory documents serve as guiding principles and offer insights into prospective legislative trajectories. At present, China’s regulatory landscape concerning the oversight of TNCs primarily encompasses departmental rules, regulatory documents, and national standards (prescribing technical specifications and precise criteria). Concurrently, the guidelines for TNCs disseminated by trade associations also play pivotal roles in shaping governance strategies.

Due Diligence Legislation for Transnational Corporations in China: An Overview

Currently, China ranks second on the list of countries with the largest number of TNCs.Footnote19 The environmental impact of Chinese TNCs is increasing due to the expansion of foreign direct investment in developing countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. At the same time, China is a significant participant in global supply chains, especially in the electronics, automotive, and infrastructure industries. Additionally, Chinese companies have made long-term energy and resource investments in many countries.Footnote20 It has been reported that some Chinese companies have caused environmental damage in host developing countries.3 From 2013 to 2020, there were 679 recorded instances of negative social, environmental, and human rights impacts of Chinese foreign investment activities.Footnote21 In response, local communities have filed lawsuits against Chinese companies in local courts, though the Chinese government prefers to resolve these disputes through negotiation. This preference is influenced by traditional Chinese cultural principles that prioritize harmony-seeking and exhibit a reluctance toward litigation.Footnote22 Simultaneously, the strong emphasis placed by Chinese governments on maintaining international reputation guides them to advise Chinese TNCs to address conflicts with local communities through negotiation and mediation. This advisory approach is designed to proactively prevent the involvement of Chinese companies in legal disputes.

Due diligence regulations in China are primarily established by government entities and private trade associations. The governance of TNCs in China has evolved through various stages in history, reflecting the country’s changing approach to TNCs oversight and management.

Government Policies

In contrast to TNCs of other countries and regions, a significant number of Chinese TNCs are state ownedFootnote23 and are obligated to adhere to specific regulations mandated by the government.Footnote20 Examples of such regulations encompass the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the State-Owned Assets of Enterprises (2008), the Guiding Opinions on Deepening the Reform of State-Owned Enterprises (2015), and the Measures for the Supervision and Administration of Overseas Investments by Central Enterprises (2017). Additionally, instructions from the Chinese government, encompassing environmental policies, have evolved over time, applying to all Chinese TNCs.

From 1949 to 1978

China was a closed economy and insulated from the world market from 1949 to 1978. The establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 marked the commencement of a 29-year period during which the nation’s economy remained isolated from international interactions, devoid of financial industry development and foreign investment activities. Until 1978, China had a single bank, the People’s Bank of China, and lacked insurance companies and other financial enterprises. Throughout this period, spanning from 1958 to 1978, the per-capita income of urban residents saw an increase of less than 4 yuan, while farmers experienced a modest growth of less than 2.6 yuan. The whole society was in short supply of materials,Footnote24 and the total value of import and export trade in 1978 was about US$20 billion.Footnote25 Importantly, foreign investment and relevant regulations were conspicuously absent during this era.

From 1979 to 2000

From 1979, Chinese companies were allowed to invest abroad, but foreign investment decisions were closely controlled by the government.Footnote26 China adopted an “opening up” strategy at that time, and all overseas investments made by Chinese companies had to be approved by the National Development and Reform Commission and the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation.Footnote27 However, the government’s focus was primarily on the economic viability and political influence of the relevant foreign investment, rather than reviewing the behavior of TNCs abroad and their performance in environmental and human rights protection. As a result, from 1979 to 2000, China encouraged foreign investment activities for economic purposes, but environmental and human rights obligations were still missing from foreign investment policies during that time.

From 2001 to 2012

The Chinese government began implementing its “Going Out” strategy in 2001. At that time, the government encouraged Chinese companies to make foreign investments. The approval procedures for investment proposals were gradually reformed and became less complicated, for both small-scale and larger projects.Footnote27

During this period, the Chinese government began promoting corporate social responsibility among Chinese companies. Around 2010, China reformed its policies of prioritizing economic performance and expanded the competencies and financial and human resources of the Ministry of Environment.3 For example, in 2008, the Guidelines to the State-Owned Enterprises Directly under the Central Government on Fulfilling Corporate Social Responsibilities were adopted.Footnote28 This regulation, classified as a regulatory document, holds significance as it underscores the Chinese government’s acknowledgment of international concerns regarding corporate social responsibility performance. It emphasized that fulfilling social responsibilities could contribute to establishing a “responsible” public image for Chinese enterprises, enhancing their international influence, and portraying China as a responsible nation.Footnote28 This regulation specifically addressed areas such as “strengthening resource conservation and environmental protection” and “protecting the legal rights of employees.”Footnote28 Additionally, it advises relevant TNCs to establish a CSR information releasing system and a regular communication and dialogue mechanism. This proactive approach should enable enterprises to receive feedback from stakeholders promptly and respond effectively.Footnote28 However, it is important to note that this regulation is voluntary in nature, and its instructive significance outweighs its practical impact.

Additionally, during this period, specific due diligence regulations were established for certain sectorial TNCs, including both state-owned and non-state-owned companies. For instance, in 2009, the Chinese Ministry of Commerce and the State Forestry Administration published “A Guide on Sustainable Management and Utilization of Overseas Forest by Chinese Enterprises.” This regulatory document offers guidance on the harvesting, processing, and utilization of forests by Chinese companies operating overseas.Footnote29 The guide emphasizes that companies should take measures to minimize or mitigate the ecological and environmental impact of forest management activities, as well as safeguard high conservation value forests.Footnote29 It also recommends that relevant foreign investment companies establish a multistakeholder consultation and transparency system. Through this system, companies should publicly disclose the key components of their legal and effective forest management documents to local communities and stakeholders.Footnote29 It’s important to note that this regulation is voluntary in nature and does not possess legally binding force.

In conclusion, during this stage, the Chinese government started paying attention to the environmental responsibilities of its foreign investment companies and Chinese foreign affiliates began to focus on environmental protection concerns. The first official nonbinding guideline was established to guide relevant businesses during this time period.

From 2013 to the Present

In 2013, China announced its “One Belt, One Road” strategy, which strongly encourages foreign investment activities. During this period, the enactment of more due diligence laws expanded the scope of environmental governance for TNCs to include climate change and green finance. In the same year, the Ministry of Commerce of China issued the Environmental Protection Guidelines for Foreign Investment and Cooperation.Footnote30 This official regulatory document emphasizes that relevant companies are encouraged to adhere to the laws and regulations of the host country to engage in pollution prevention and environmental impact assessment.Footnote30 Notably, it was the first time that companies were encouraged to purchase environmental liability insurance as a means of reducing associated risks. Additionally, this regulatory document promotes the regular disclosure of environmental information by companies, including their plans to implement environmental protection laws and regulations, the measures they have implemented, and their environmental performance achievements.Footnote30

From 2021 to 2022, the Chinese central government introduced a series of regulatory documents, which fall under the category of soft law, to regulate the environmental due diligence obligations of Chinese TNCs in specific sectorsFootnote31 and overseas Chinese companies as a whole. One notable document is the Green Development Guidelines for Overseas Investment and Cooperation 2021.Footnote32 This regulatory document encourages Chinese TNCs to make foreign investment through establishing green overseas economic and trade cooperation zones. Companies involved are urged to promote green industries within the zone, fostering environmentally friendly practices like shared infrastructure, resource recycling, energy conservation, and carbon emission reduction.Footnote32 Additionally, the document introduces the promotion of green technology innovation, urging Chinese companies overseas to establish research and development (R&D) centers and to foster the development of global advanced green technologies.Footnote32 In 2022, the National Development and Reform Commission of China enacted the Opinions on Promoting Green Development under the Belt and Road Initiative.Footnote33 It highlights the importance of enhancing green financial cooperation and promoting capacity building in the field of green finance. Notably, the document also emphasizes the need for strengthened collaboration in addressing climate change, marking the first time this aspect has been specifically mentioned.Footnote33

During this period, China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment enacted the first hard law known as the Measures for the Administration of the Law-Based Disclosure of Environmental Information by Enterprises 2021.Footnote34 This regulation, classified as a departmental rule, is compulsory in nature, although its legal effect is inferior to laws passed by the National People’s Congress and administrative regulations passed by the State Council. Under this regulation, key pollutant-discharging entities, listed companies and their subsidiaries, and bond-issuing enterprises held liable for ecological or environmental law violations are obligated to disclose environmental information. The disclosed reports should include details on pollutant generation, control, and discharge, carbon emissions, ecological and environmental emergencies, and violations of ecological and environmental laws. The Ministry of Ecology and Environment, along with local departments, will make the enterprise’s environmental information available to the public on government websites. Authorities also have the power to require noncompliant enterprises to take corrective actions and to impose fines for failure to disclose environmental information.

Summary

summarize China’s due diligence legislation for the governance of TNCs, as issued by the government.

Table 1. Departmental Rules Containing Due Diligence Obligations

presents departmental rules related to the due diligence obligations of TNCs in China. and list relevant regulatory documents and national standards, respectively. The departmental rules, which are compulsory, impose obligations that must be adhered to by relevant TNCs. Noncompliance can lead to punishments according to the provisions outlined in these rules. It is important to note, however, that these departmental rules primarily focus on enhancing the administration and supervision of overseas investments by relevant enterprises. The due diligence obligations are mentioned in only a few provisions as recommendations.

Table 2. Regulatory Documents of Environmental Guidelines for Due Diligence

Table 3. National Standards on Due Diligence Obligations

The regulatory documents and national standards listed in and are also issued by the Chinese government and primarily focus on regulating the due diligence obligations of TNCs. However, it is important to note that these regulations fall under the category of soft laws in China. First, many of the regulatory documents are titled as “guidelines” and “opinions,” indicating their nonbinding nature. Second, the national standards are classified as recommended standards rather than mandatory requirements. Consequently, the impact of these regulations on Chinese overseas enterprises remains uncertain in practice.Footnote41

Trade Associations Guidelines

Trade associations have played a crucial role in enhancing due diligence legislation for the environmental governance of TNCs in China. In comparison to regulations enacted by governments, the guidelines issued by trade associations are often more comprehensive, advanced, and enforceable.

The development of trade associations in China can be traced back to three stages, aligning with the progress of market economy development and government reforms since China’s adoption of an “opening up” strategy in 1979. These stages reflect the evolving landscape of trade associations in China.

From 1979 to 1990

Before 1979, trade associations in China operated under the leadership of administrative agencies, primarily assisting them in implementing relevant regulations and policies. This differed significantly from the trade associations in the United States and the European Union. However, with the adoption of China’s “opening up” strategy in 1979, the government initiated the implementation of a “four separations” strategy. This strategy aimed to separate the functions of the government from those of enterprises, capital, business units, and market intermediary organizations through extensive research on foreign trade associations.Footnote42

Around 1988, numerous local trade associations were established, such as the China Chamber of Commerce of Metals, Minerals & Chemicals Importers & Exporters (CCCMC) and China National Textile and Apparel Council (CNTAC). Despite the establishment of these associations, they still maintained close relationships with relevant administrative agencies. Additionally, due to the limited foreign investment activities of Chinese companies at the time, these trade associations did not prioritize the due diligence obligations of their members.

From 1990 to 2012

From 1990 to 2012, the Chinese government implemented the “Dual Management” policy for nongovernmental organizations, including trade associations. According to this policy, trade associations were required to be accountable to both their registration authorities and business supervisory units.Footnote43 As a result, trade associations in China gained a certain level of independence as they were no longer considered part of specific administrative agencies. However, their development continued to be influenced by relevant administrative agencies due to their responsibilities toward both registration and business supervision.

With the growth of Chinese overseas investment, the CNTAC issued the first due diligence guideline, China Social Compliance 9000 for Textile & Apparel Industry, in 2005.Footnote44 This guideline addresses various fundamental human rights issues, including child labor, forced or compulsory labor, working hours, wages and benefits, discrimination, harassment, and abuse.Footnote45 It is worth noting that the guideline explicitly states that it does not impose additional legal obligations or alter the existing legal obligations of enterprises.Footnote45

From 2012 to the Present

From 2012 to the present, trade associations in China have become more independent from relevant administrative agencies. This shift occurred after the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in 2012, which issued development policies that called for the decoupling of trade associations from administrative agencies. These policies aimed to clarify the functional boundaries between trade associations and administrative agencies. As per these policies, any sponsorship, management, or affiliation relationship between trade associations and administrative agencies was to be abolished, and the administrative responsibilities of trade associations were to be stripped away. As of the end of 2021, more than 70,000 trade associations had been decoupled from administrative agencies.Footnote46

The current relationship between trade associations and administrative agencies is complex and subtle. While trade associations have gained autonomy and more flexibility to explore due diligence guidelines, they still experience indirect influence from administrative agencies. This intentional arrangement by the Chinese government allows trade associations to take the lead in developing and implementing regulations, serving as a reference for future legislation.

During this stage, Chinese overseas investment has expanded, leading trade associations to issue a broader range of guidelines. These guidelines have evolved from “social responsibility” guidelines to encompass more specific areas such as “sustainable” and “due diligence” practices.

Summary

provides a summary of China’s due diligence guidelines for the governance of TNCs issued by trade associations.

Table 4. Environmental Guidelines for TNCs Issued by Trade Associations

In comparison to the soft regulations implemented by the Chinese government, Chinese trade associations have taken a more proactive approach in issuing comprehensive guidelines on corporate social responsibility and sustainability. These guidelines aim to regulate the human rights and environmental protection obligations of foreign investment companies. From 2005 to 2018, trade associations such as CCCMC and CNTAC drew upon the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) GuidanceFootnote49 and developed a series of due diligence guidelines. Moreover, the CHINCA (China International Contractors Association) issued its Sustainable Infrastructure Guidelines in 2018 and Social Responsibility Guidelines in 2022, as indicated in .Footnote50 They all played significant roles in the governance of relevant TNCs. Notably, other trade associations such as the China Electronics Standardization Association, the China International Contractors Association, and the China Textile and Apparel Council have also released similar guidelines.Footnote51 These trade association guidelines exhibit a certain degree of commitment to promoting responsible business practices and sustainability across various sectors of the Chinese economy.

Additionally, over the period from 2005 to 2022, the guidelines issued by Chinese trade associations underwent a significant expansion in their scope and comprehensiveness. One notable example is the Chinese Due Diligence Guidelines for Mineral Supply Chain 2022, which draw upon relevant requirements from the European Union (EU) Conflict Minerals Regulation (2017/821)Footnote16 and the U.S. Dodd–Frank Act (Section 1502).Footnote52 These guidelines not only address the social responsibility of mineral companies but also provide detailed guidance on critical aspects such as processing, auditing, and monitoring throughout the mineral supply chain. The Guidelines for Responsible Overseas Investment of China’s Textile and Apparel Industry 2018 also regulate the exit strategy for investors, emphasizing their obligation to uphold social responsibilities both before and after the exit stage.Footnote53

Furthermore, assessment, grievance, mediation, and consultation mechanisms to enhance the effectiveness of due diligence practices were also established. Examples include the Mineral Supply Due Diligence Assessment Tool 2022,Footnote54 the Mineral Supply Chain Grievance Mechanism 2022,Footnote55 and the Mediation and Consultation Mechanism for the Mining Industry and Mineral Value Chain 2023.Footnote56 In contrast to regulatory documents set by governments, which generally advocate for the improvement of CSR among Chinese companies, the due diligence mechanisms instituted by trade associations are notably more specific and detailed. This specificity enhances ease of implementation. In detail, the mineral supply chain due diligence assessment follows a structured process consisting of risk identification and assessment, risk prevention and mitigation, internal and external assessment, reporting and dissemination, and providing or cooperating in remediation when appropriate.Footnote54 The grievance, mediation, and consultation mechanisms provide a platform for stakeholders to engage in dialogue and consultation, enabling the identification and investigation of grievances within responsible supply chain governance, as well as their proper handling and resolution.

Key Features of Due Diligence Regulation in China

Environmental Focus in Chinese Due Diligence

Besides environmental protection, it is important to note that there are other human rights issues, which encompass a wide array of rights inherent to all individuals, spanning civil, political, economic, social, and cultural dimensions. When comparing due diligence legislation governing TNCs in China with that of other countries and regions, it becomes apparent that China’s government-issued regulations primarily emphasize environmental issues.

Notably, there is an ongoing movement in other countries and regions to establish mandatory due diligence legislation of all human rights issues.Footnote57 This legislative push began in 2017 with the enactment of the French Duty of Vigilance Law,Footnote13 and in 2023 the German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act came into effect.Footnote14 Furthermore, the European Commission released its Proposed Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence on 23 February 2022.Footnote58 Similarly, the United States is also following the EU’s lead in formulating comprehensive due diligence legislation that addresses all human rights impacts across the entire value chain.Footnote52 These developments require businesses to comply with due diligence requirements of both environmental protection and other human rights issues. Also, they entail penalties for those that fail to prevent relevant adverse impacts.

In contrast to the models implemented in most other countries, the current development of due diligence regulations issued by government in China primarily centers around environmental protection, with less emphasis on other human rights issues (as evidenced in ).Footnote59 This orientation can be attributed to two key factors. First, the Chinese government, in alignment with international consensus, acknowledges the pivotal role of environmental protection and perceives the reinforcement of obligations in this domain as instrumental in bolstering China’s global reputation. Consequently, there exists a heightened inclination within the Chinese government to augment environmental governance among Chinese TNCs. Second, an analysis report from the Chinese government underscores China’s proactive stance in establishing independent criteria for safeguarding human rights, distinctly excluding environmental protection.Footnote60 This deliberate effort is designed to challenge what is characterized as “prevailing Western-developed concepts and content.” Concurrently, the Chinese government resists adopting the corresponding elevated human rights protection standards within the state and for Chinese TNCs. This unique approach positions China on a trajectory aimed at asserting its distinct perspective on human rights protection, representing a deliberate deviation from conventional Western frameworks.

Trade Associations Guidelines as Legislative Experiment

In contrast to due diligence legislation in other countries and regions, the guidelines issued and implemented by trade associations in China can be seen as a legislative experiment for Chinese lawmakers.

Influenced by the principles of Tai-Chi, a traditional Chinese philosophy symbolizing the harmony of different forces, governance in China embraces the coexistence of both formal regulatory mechanisms and informal approaches. China has a tradition of leveraging nonofficial governance and nonliteral regulations.Footnote61

Consequently, sensitive and controversial issues are sometimes entrusted to nonofficial regulations, allowing the government to observe their implementation and effects before deciding on potential legislation. For instance, prior to the adoption of the “opening up” strategy in 1979, the state practiced collective ownership and egalitarian distribution. During this period, as enthusiasm for production among the Chinese people waned and economic development faced challenges, some local areas in Anhui Province experimented with the household contract system without official policies but with the tacit approval of the government.Footnote62 Similarly, before the official establishment of the Special Economic Zone, certain cities in Guangdong and Fujian Province began implementing “opening up” measures, with their effects being observed and supervised by the Chinese government.Footnote63 These instances illustrate the tradition of nonofficial and nonliteral governance serving as an experimental ground for policymakers and legislators in China. Sensitive and contentious issues often find regulation through nonofficial means, which may eventually be formalized into official policies and laws.

The due diligence guidelines issued by trade associations potentially represent a pioneering legislative experiment for Chinese policymakers. First, recognizing certain human rights issues as “sensitive and controversial,” the Chinese government temporarily refrains from direct legislation on these matters. There remains the possibility that China will introduce subsequent legislation based on the observed effects of implementing relevant guidelines issued by trade associations, which is similar to the examples just illustrated. Second, the Chinese central government has underscored the importance of fully considering the opinions of trade associations in formulating administrative regulations, rules, and regulatory documents.Footnote64 Illustrative examples of such regulations include the “Measures for the Administration of the Law-Based Disclosure of Environmental Information by Enterprises 2021,” shaped by the information disclosure requirements articulated in relevant trade association guidelines.

At present, trade associations, supported by the Chinese government, wield influence over Chinese authorities through documents that include guidelines for environmental and human rights due diligence. This influence has prompted the Chinese government to deepen its understanding of due diligence laws, leading to the development of related regulations.Footnote65 Meanwhile, these guidelines surpass government-enacted counterparts in both comprehensiveness and stringency,Footnote66 earning tacit approval from the Chinese government. By directing companies to align with the emerging global trend of due diligence legislation, these guidelines play a crucial role.

However, as discussed in the preceding section, any legislation addressing human rights issues and standards would distinctly reflect Chinese perspectives, drawing from the experiences gained through Chinese foreign investment activities. It is prudent to maintain ongoing scrutiny of the evolving landscape of due diligence legislation in China.

Prospects for the Future of Chinese Due Diligence Legislation

In light of the global movement toward mandatory human rights due diligence legislation and the continued growth of Chinese foreign investment activities, this section delves into the pivotal choices facing the Chinese government regarding its due diligence legislation. Specifically, three key directions are explored: the transition toward mandatory legislation, the reluctance to encompass a wider range of human rights issues, and leveraging international initiatives to enhance the effectiveness of due diligence practices.

Moving Toward Mandatory Legislation

In response to the global trend of mandatory due diligence legislation, the Chinese government has recognized the importance of moving toward a mandatory framework. Currently, China has implemented a mandatory law that mandates companies to disclose environmental information.Footnote34 This shift indicates a transition from soft law to hard law, signaling the development of environmental due diligence regulations. The Measures for the Administration of the Law-Based Disclosure of Environmental Information by Enterprises, which came into effect on 8 February 2022, require companies to compulsorily disclose significant environmental information. The regulation establishes requirements and specific procedures for environmental information disclosure. Violations of the provisions outlined in this regulation can result in fines and penalties.Footnote34

This regulation can be seen as the initial step taken by the Chinese government in developing due diligence legislation for environmental governance of TNCs. At present, the Chinese government is placing significant attention on environmental protection due diligence obligations and demonstrating a more cooperative attitude on the international stage. It is anticipated that more mandatory regulations will be enacted in the future, although the focus is likely to remain within the realm of environmental governance. Concurrently, as previously discussed, Chinese due diligence legislation for TNCs is profoundly shaped by the policies of the supreme leadership body. This body prioritizes both the international reputation of China and the establishment of independent criteria for addressing human rights issues. Consequently, the legislative process is contingent on the attitudes and directives of the central government.

Reluctant to Include Other Human Rights Issues in the Short Term

In practical terms, the Chinese government approaches international human rights cooperation with caution due to concerns that human rights issues may be exploited by other countries as a tool against China.Footnote67 China generally places greater emphasis on economic and social rights compared to civil and political rights.Footnote68 As discussed earlier, the influence of politics is significant in shaping due diligence regulations for TNCs in China. Consequently, it is anticipated that the Chinese legislature may exhibit reluctance in incorporating additional human rights issues within the foreseeable future.

Simultaneously, recognizing the importance of helping Chinese companies adapt to and familiarize themselves with relevant due diligence regulations in the EU and the United States, the Chinese government may seek to create space for trade associations to address human rights due diligence matters and guide relevant enterprises in complying with these new laws. As previously mentioned, trade associations in China maintain close relationships and cooperation with the government. The due diligence guidelines issued by these trade associations can serve as a valuable reference for Chinese legislators, facilitating the understanding of due diligence laws in other countries and regions. Such an approach is advantageous in maintaining the competitiveness of Chinese companies.

Enhancing Due Diligence Legislation Through International Initiatives

Generally, China prefers to ratify legally binding international agreements of trade and investment, and has been careful to avoid making agreements about national security and sovereignty issues, and human rights ones.Footnote69 However, to strengthen international standing, since 2013 when China proposed the “One Belt, One Road” initiative, the government of China has shown a more open attitude toward international obligations.Footnote70 This shift is exemplified by China’s commitment, announced by the President in September 2021, to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 and cease support for new overseas coal power projects without exceptions.Footnote71

Since June 2014, an intergovernmental working group has been established within the UN framework, and is drafting a binding treaty on human rights issues of business.Footnote72 In 2022, the intergovernmental working group shared suggested proposals for amendments to the third revised draft of the binding treaty. The potential implementation of these binding international agreements would play an important role in enhancing Chinese binding due diligence legislation. Also, the future legislation at both the international level and the Chinese national level should be further observed.

Conclusions and Future Research

The study is dedicated to exploring the application of due diligence law as a mechanism to strengthen environmental governance of TNCs in China. The Chinese government has taken significant steps since 2008 by implementing various regulations that primarily prioritize environmental protection in relation to TNCs. Additionally, trade associations have played a crucial role in complementing government regulations by issuing comprehensive and practical due diligence guidelines, essentially serving as legislative experiments for Chinese legislators. Currently, there is a noticeable shift in Chinese due diligence legislation, transitioning from a voluntary approach to a mandatory one, while also distinctively addressing environmental concerns separately from human rights issues in the short term. It is noteworthy that the issuance of binding due diligence regulations to bolster CSR governance has become an inevitable trend, and China must actively progress in this direction. Throughout this evolution, mandatory international agreements are anticipated to play a pivotal role in fortifying Chinese binding due diligence legislation further.

Future research should center on understanding effective and innovative pathways to implement human rights due diligence mechanisms that address the fundamental needs of enhancing the governance of TNCs. Ongoing exploration of human rights due diligence regulations involving TNCs is expected at both the international and national levels, particularly in regions like the United States, the European Union, and China, which are home to many major TNCs. Therefore, long-term observation and analysis of relevant international cooperation in this area are crucial for further understanding and advancement.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Zehua Tian

Dr. Zehua Tian is an associate research fellow at the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Great Bay Area Research Institute at the Law School, Guangzhou College of Commerce. She holds a PhD in law from the University of Macau, and her research focuses on the extraterritorial application of environmental law, environmental governance of transnational corporations, and online dispute resolution.

Notes

1. United Nations Commission on Human Rights, United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (New York: United Nations Commission on Human Rights, 2011).

2. For instance, the Slave-Free Business Certification Act of 2022 and the Corporate Governance Improvement and Investor Protection Act of 2021 in the United States, as well as the Duty of Vigilance Law of 2017 in France and the Supply Chain Act of 2021 in Germany.

3. D. Shinn, “The Environmental Impact of China’s Investment in Africa,” International Policy Digest (2015), https://intpolicydigest.org/2015/04/08/the-environmental-impact-of-china-s-investment-in-africa (accessed 30 June 2023).

4. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, “World Investment Report 2007: Transnational Corporations, Extractive Industries and Development,” (2007), https://unctad.org/en/Docs/wir2007p4_en.pdf (accessed 30 June 2023).

5. R. Fowler, “International Environmental Standards for Transnational Corporation,” Environmental Law 25, no. 1 (1995): 1–30.

6. M. Finger and D. Svarin, “Transnational Corporations and the Global Environment,” in D. D. Zhang, ed., Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 1–31. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.489.

7. M. Anderson, “Transnational Corporations and Environmental Damage: Is Tort Law the Answer?,” Washburn Law Journal 41, no. 2 (2002): 399–425.

8. L. Agudelo, L. Johannsdottir, and B. Davidsdottir, “A Literature Review of the History and Evolution of Corporate Social Responsibility,” International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility 4, no. 1 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1186/s40991-018-0039-y (accessed 30 June 2023).

9. M. Porter and M. Kramer, “Creating Shared Value,” Harvard Business Review (2011): 1–17, https://www.communitylivingbc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Creating-Shared-Value.pdf (accessed 30 June 2023).

10. United States Congress, Corporate Code of Conduct Act. H. R. 4596, 106th Congress, 1990–2000.

11. The Corporate Code of Conduct Bill (2002), https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_Legislation/Bills_Search_Results/Result?bId=s259 (accessed 30 June 2023).

12. S. Seck, “Home State Regulation of Environmental Human Rights Harms as Transnational Private Regulatory Governance,” German Law Journal 13 (2012): 1363–85.

13. LOI No. 2017-399, 27 March 2017.

14. E. Gilligan, “Mandatory Human Rights Due Diligence: An Issue Whose Time Has Come,” Corporate Justice Coalition (2019), https://corporatejusticecoalition.org/news/issue-whose-time-come (accessed 19 June 2023).

15. Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 amending Directive 2013/34/EU as regards disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large undertakings and groups.

16. Regulation (EU) 2017/821 of the European Parliament and the Council of May 2017 laying down supply due diligence obligations for Union importers of tin, tantalum and tungsten, their ores, and gold originating from conflict-affected and high-risk areas.

17. Regulation (EU) No. 995/2010 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 October 2010 laying down the obligations of operators who place timber and timber products on the market.

18. United Nations Human Rights Council, Open-ended intergovernmental working group on transnational corporations and other business enterprises with respect to human rights, https://www.ohchr.org/en/hr-bodies/hrc/wg-trans-corp/igwg-on-tnc (accessed 30 June 2023).

19. G. Grace, “The Rise of Chinese TNCs, BRICS, and Current Global Challenges,” (2016), https://www.tni.org/en/article/the-rise-of-chinese-tncs-brics-and-current-global-challenges (accessed 1 July 2023).

20. S. Zadek, G. Long, and J. Wickerham, “Advancing the Sustainability Practices of China’s Transnational Corporations,” International Institute for Sustainable Development (2010), https://www.iisd.org/system/files/publications/advancing_sustainability_corp.pdf (accessed 30 June 2023).

21. Business & Human Rights Resource Centre, https://www.business-humanrights.org/en (accessed 30 June 2023).

22. B. K. Y. Wong, “Traditional Chinese Philosophy and Dispute Resolution,” Hong Kong Law Journal 30 (2000): 304–19.

23. Caixin News, “The list of Chinese Largest 100 Transnational Corporations in 2020” (2020), https://luruquan.blog.caixin.com/archives/235745 (accessed 23 November 2023).

24. J. Matthews, “Despite Announcements of Factory Reforms, Work Remains Slack,” Washington Post, 28 July 1978.

25. National Bureau of Statistics of China, “1978 Nian Yi Lai Wo Guo Jing Ji She Hui Fa Zhan De Ju Da Bian Hua [Great Changes in China—Economic and Social Development From 1978],” http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2013-11/06/content_2522445.htm (accessed 1 July 2023).

26. X. Gong and A. Boute, “For Profit or Strategic Purpose? Chinese Outbound Energy Investments and the International Economic Regime,” Journal of World Energy Law & Business 14, no. 4 (2021): 345–62.

27. J. Zhang, Jieying, and X. Zhou. “Thoughts on Policy-Making of China’s Overseas Investments against the Background of the ‘Going Out’ Strategy,” Guo Ji Mao Yi [International Trade] 4 (2007): 27.

28. State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council, “Guan Yu Zhong Yang Qi Ye Lv Xing She Hui Ze Ren De Zhi Dao Yi Jian (Guidelines to the State-Owned Enterprises Directly under the Central Government on Fulfilling Corporate Social Responsibilities),” (2008).

29. Ministry of Commerce of China and the State Forestry Administration, “Zhong Guo Qi Ye Jing Wai Sen Lin Ke Chi Xu Jing Ying Li Yong Zhi Nan (A Guide on Sustainable Management and Utilization of Overseas Forest by Chinese Enterprises),” (2009).

30. Ministry of Commerce and Ministry of Environmental Protection, “Dui Wai Tou Zi He Zuo Huan Jing Bao Hu Zhi Nan (Environmental Protection Guidelines for Foreign Investment and Cooperation),” (2013).

31. Ministry of Ecology and Environment, Ministry of Commerce, “Dui Wai Tou Zi He Zuo Jian She Xiang Mu Sheng Tai Huan Jing Bao Hu Zhi Nan (Guidelines for Ecological Environmental Protection of Foreign Investment Cooperation and Construction Projects),” (2022).

32. Ministry of Commerce and the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, “Dui Wai Tou Zi He Zuo Lv Se Fa Zhan Gong Zuo Zhi Yin (Green Development Guidelines for Overseas Investment and Cooperation),” (2021).

33. National Development and Reform Commission et al., “Guan Yu Tui Jin Gong Jian ‘Yi Dai Yi Lu’ Lv Se Fa Zhan De Yi Jian (Opinions on Promoting Green Development under the Belt and Road Initiative),” (2022).

34. China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment, “Qi Ye Huan Jing Xin Xi Yi Fa Pi Lou Guan Li Ban Fa (The Measures for the Administration of the Law-Based Disclosure of Environmental Information by Enterprises),” (2021).

35. State-Owned Asset Supervision & Administration Commission of the State Council, “Zhong Yang Qi Ye Jing Wai Tou Zi Jian Du Guan Li Ban Fa (Measures for the Supervision and Administration of Overseas Investments by Central Enterprises),” (2017).

36. National Development & Reform Commission (including former State Development Planning Commission), “Qi Ye Jing Wai Tou Zi Guan Li Ban Fa (Measures for the Administration of Overseas Investment of Enterprises),” (2018).

37. Ministry of Commerce et al., “Zhong Guo Jing Wai Qi Ye Wen Hua Jian She Ruo Gan Yi Jian (Opinions on Development of a Culture by Chinese Enterprises Oversea),” (2012).

38. State Administration for Market Regulation and Standardization Administration, “She Hui Ze Ren Zhi Nan (Guidance on Social Responsibility),” (2015).

39. State Administration for Market Regulation and Standardization Administration, “He Gui Guan Li Ti Xi Zhi Nan (Compliance Management Systems-Guidelines),” (2017).

40. State Administration for Market Regulation and Standardization Administration, “She Hui Ze Ren Guan Li Ti Xi Yao Qiu Ji Shi Yong Zhi Nan (Social Responsibility Management Systems-Requirements with Guidance for Use),” (2020).

41. An interview with Y. Tang and Y. Han, former heads of the legal department in the overseas division of a major state-owned enterprise and a private enterprise in China.

42. C. Jing and Y. Li, eds., Development Report on China’s Trade Associations & Chambers of Commerce (Beijing: Social Science Academic Press, 2014).

43. M. Wang, “She Hui Zu Zhi: Cong Shuang Chong Guan Li Dao Fen Ji Guan Li (Social Organizations: From Dual Management to Hierarchical Management),” Aisixiang (2012), https://www.aisixiang.com/data/54295.html (accessed 12 June 2023).

44. CNTAC, China Social Compliance 9000 for Textile & Apparel Industry (2005), http://www.csc9000.org.cn/down.php?lm=26 (accessed 08 June 2023).

45. CNTAC, China Social Compliance for Textile & Apparel Industry Principles and Guidelines (2005), http://www.csc9000.org.cn/d/file/p/2023/02-03/876e38a82f9021c6444d422517f4eeca.pdf (12 June 2023).

46. Chinese Communist Party News Network, http://cpc.people.com.cn/n1/2022/0825/c64387-32510884.html (accessed 14 June 2023).

47. CHINCA, “Guide on Social Responsibility for Chinese International Contractors,” (2012 and 2022).

48. CHINCA, “Guidelines of Sustainable Infrastructure for Chinese International Contractors,” (2018), https://www.chinca.org/EN/info/18013108264011 (accessed 03 March 2024).

49. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, “The OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas” (2016).

50. Lorenz & Partners, “Offshore Planning for Chinese Companies: Risks and Solutions” (2019), https://lorenz-partners.com/download/china/NL110E-Offshore-planning-for-Chinese-companies-Feb19.pdf (accessed 15 June 2023).

51. China Electronics Standardization Association, http://www.cesa.cn/index (accessed 15 June 2023); China International Contractors Association, http://www.chinca.org/EN (accessed 15 June 2023); China National Textile and Apparel Council, http://www.cntac.org.cn (accessed 15 June 2023).

52. R. Miller, “The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act: Title VII, Derivatives” (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service [CRS], (2019).

53. CNTAC, “Guidelines for Responsible Overseas Investment of China’s Textile and Apparel Industry” (2018).

54. CCCMC, Mineral Supply Due Diligence Assessment Tool (2022), https://www.cccmc.org.cn/kcxfzzx/zyzx/gj/ff80808181489d3201820f4c33dd1240.html (accessed 14 June 2023).

55. CCCMC, Mineral Supply Chain Grievance Mechanism (2022), https://www.cccmc.org.cn/kcxfzzx/zyzx/gj/ff80808183e3a11c01845a1a939510a5.html (accessed 14 June 2023).

56. CCCMC, Mediation and Consultation Mechanism for the Mining Industry and Mineral Value Chain (Pilot Version) (2023), https://www.cccmc.org.cn/kcxfzzx/zyzx/al (accessed 14 June 2023).

57. S. Chance, “Code of Conduct for Multinational Corporations,” Business Law (ABA) 33 (1977–1978): 1799–820.

58. European Commission, Proposal for a Directive on corporate sustainability due diligence and annex, https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/proposal-directive-corporate-sustainable-due-diligence-and-annex_en (accessed 19 June 2023).

59. United Nations (General Assembly), “International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,” Treaty Series 999, 171 (1966).

60. Y. H. Zhang, “Quan Mian Zheng Que Li Jie Ren Quan Gai Nian, Ren Quan Hua Yu Yi Ji Hua Yu Ti Xi (Comprehensively and Correctly Understand the Concept of Human Rights, Human Rights Discourse and the Discourse System),” People.cn (2017), http://theory.people.com.cn/n1/2017/0728/c143843-29435562.html (accessed 25 November 2023).

61. R. Huang, 1587: A Year of No Significance: The Ming Dynasty in Decline (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1982).

62. “Gai Ge Kai Fang Gu Shi: Da Bao Gan De Gu Shi (The Story of Reform and Opening Up: The Narrative of the Household Contract System),” Sohu (2018), https://www.sohu.com/a/282218366_317270 (accessed 27 November 2023).

63. “Zhong Gong Zhong Yang Guo Wu Yuan Pi Zhun Guang Dong Sheng Wei Fu Jian Sheng Wei Guan Yu Dui Wai Jing Ji Huo Dong Shi Xing Te Shu Zheng Ce He Ling Huo Cuo Shi De Liang Ge Bao Gao (The Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council Approved Two Reports from the Guangdong Provincial Committee and the Fujian Provincial Committee on the Implementation of Special Policies and Flexible Measures for Foreign Economic Activities [1979] No. 50)” (1979), https://zgydata.hinews.cn/127-20210506111444-60935f2451bcc.pdf (accessed 27 November 2023).

64. Office of the State Council, “Guo Wu Yuan Ban Gong Ting Guan Yu Zai Zhi Ding Xing Zheng Fa Gui Gui Zhang Xing Zheng Gui Fan Xing Wen Jian Guo Cheng Zhong Chong Fen Ting Qu Qi Ye He Hang Ye Xie Hui Shang Hui Yi Jian De Tong Zhi (Notice of the General Office of the State Council on Fully Listening to the Opinions of Enterprises and Trade Associations and Chambers of Commerce in the Process of Formulating Administrative Regulations, Rules and Administrative Regulatory Documents) [2019] No. 9” (2019), https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2019-03/13/content_5373423.htm (accessed 27 November 2023).

65. L. Sun, “Speaking at the International Seminar on Supply Chain Due Diligence Legislations: Trends and Challenges” (2022), https://live.baidu.com/m/media/pclive/pchome/live.html?room_id=7409509940&source=h5pre (accessed 15 June 2022).

66. CCCMC and GIZ, “Guidelines for Social Responsibility in Outbound Mining Investment,” http://images.mofcom.gov.cn/csr2/201812/20181224151850626.pdf (accessed 23 May 2023).

67. Y. Guo and S, Mei, “Ren Quan Pai” Lv Da Lv Bai (The United States Play ‘Human Rights Card’ with Failure as Usual),” Qiu Shi (2021), http://www.qstheory.cn/qshyjx/2021-10/23/c_1127987400.htm (accessed 20 June 2023).

68. D. Desierto, “The Revived Debate Over Development and Human Rights: Economic Self-Determination, Sovereignty, and Non-Discrimination in State Policies,” Blog of the European Journal of International Law (2018), https://www.ejiltalk.org/the-revived-debate-over-development-and-human-rights-sequenced-or-selective-compliance (accessed 15 June 2023).

69. M. Parry and U. Jochheim, “China’s Compliance with Selected Fields of International Law,” European Parliamentary Research Service, PE 696.207, (2021).

70. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, “Carry Forward International Rule of Law and Improve Economic and Trade Rules for Securing High-Quality Belt and Road Development” (2021), https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/wjbxw/202111/t20211113_10447812.html (accessed 30 June 2023).

71. J. Xi, “Speaking of President Xi Jinping at 75th United Nations General Assembly,” 2021.

72. L. Zamfir, “Towards a Binding International Treaty on Business and Human Rights,” European Parliamentary Research Service, PE 620.229 (2018).