ABSTRACT

Despite empirical evidence supporting clinical hypnosis for numerous conditions, its utilization in healthcare is limited due to skepticism and misconceptions. This review identifies and maps research on clinical hypnosis perceptions among the general population, healthcare patients, and more specifically patients with cancer. A systematic search following JBI PRISMA ScR guidelines was conducted in EBSCOhost, ProQuest, PubMed, and PMC, resulting in 18 peer-reviewed, English language articles (2000–2023). Most studies employed quantitative methods, which were complemented by some qualitative and one mixed-methods approach. The results found attitudes toward hypnotherapy, especially when administered by licensed professionals, are consistently positive; however, awareness of hypnosis remains low within the healthcare sector, particularly in cancer care. Although hypnotherapy was found to be useful, misinformation, a lack of understanding, and awareness persist. Few studies address the reasons behind people’s opinions or focus on integrating hypnotherapy into healthcare. Research investigating hypnosis attitudes in cancer care is scant, necessitating further exploration.

Berichterstattung und Kartierung von Forschungsergebnissen über die Wahrnehmung der klinischen Hypnose in der Allgemeinbevölkerung und bei Patienten, die eine Gesundheitsversorgung einschließlich Krebsversorgung erhalten : Eine Übersichtsarbeit

Malwina Szmaglinska, Deborah Kirk und Lesley Andrew

Zusammenfassung: Obwohl die klinische Hypnose für zahlreiche Erkrankungen empirisch belegt ist, wird sie aufgrund von Skepsis und falschen Vorstellungen im Gesundheitswesen nur begrenzt eingesetzt. In dieser Übersichtsarbeit werden Forschungsergebnisse über die Wahrnehmung der klinischen Hypnose in der Allgemeinbevölkerung, bei Patienten im Gesundheitswesen und insbesondere bei Krebspatienten identifiziert und dargestellt. Es wurde eine systematische Suche in EBSCOhost, ProQuest, PubMed und PMC durchgeführt, die den JBI PRISMA ScR-Richtlinien folgte und 18 begutachtete, englischsprachige Artikel (2000-2023) ergab. In den meisten Studien wurden quantitative Methoden angewandt, ergänzt durch einige qualitative Methoden und einen gemischten Ansatz. Die Ergebnisse zeigen, dass die Einstellung zur Hypnotherapie, insbesondere wenn sie von lizenzierten Fachleuten durchgeführt wird, durchweg positiv ist; allerdings ist ihr Bekanntheitsgrad im Gesundheitswesen, insbesondere in der Krebsbehandlung, nach wie vor gering. Obwohl die Hypnotherapie als nützlich eingestuft wurde, gibt es nach wie vor Fehlinformationen, Unverständnis und mangelndes Bewusstsein. Nur wenige Studien befassen sich mit den Gründen für die Meinungen der Menschen oder mit der Integration der Hypnotherapie in die Gesundheitsversorgung. Es gibt nur wenige Studien, die sich mit der Einstellung zur Hypnose in der Krebsbehandlung befassen, so dass weitere Untersuchungen erforderlich sind.

Rapport et cartographie des données de recherche sur les perceptions de l’hypnose clinique au sein de la population générale et des patients recevant des soins de santé, y compris des soins contre le cancer : Un examen approfondi

Malwina Szmaglinska, Deborah Kirk, et Lesley Andrew

Résumé: Malgré les preuves empiriques soutenant l’hypnose clinique pour de nombreuses pathologies, son utilisation dans les soins de santé est limitée en raison du scepticisme et des idées fausses. Cette revue identifie et cartographie la recherche sur les perceptions de l’hypnose clinique parmi la population générale, les patients en soins de santé, et plus spécifiquement les patients atteints de cancer. Une recherche systématique a été menée dans EBSCOhost, ProQuest, PubMed, et PMC, en suivant les directives JBI PRISMA ScR, ce qui a permis d’obtenir 18 articles en langue anglaise, évalués par des pairs (2000-2023). La plupart des études ont utilisé des méthodes quantitatives, complétées par quelques approches qualitatives et une approche mixte. Les résultats ont montré que les attitudes à l’égard de l’hypnothérapie, en particulier lorsqu’elle est administrée par des professionnels agréés, sont toujours positives ; cependant, sa notoriété reste faible dans le secteur des soins de santé, en particulier dans le domaine des soins contre le cancer. Bien que l’hypnothérapie ait été jugée utile, la désinformation, le manque de compréhension et le manque de sensibilisation persistent. Peu d’études s’intéressent aux raisons qui sous-tendent les opinions des gens ou se concentrent sur l’intégration de l’hypnothérapie dans les soins de santé. La recherche sur les attitudes vis-à-vis de l’hypnose dans les soins en cancérologie est rare et nécessite une exploration plus poussée.

Presentación de informes y mapeo de pruebas de investigación sobre las percepciones de la hipnosis clínica entre la población general y los pacientes que reciben atención sanitaria, incluida la atención oncológica : Una revisión sistemática exploratoria.

Malwina Szmaglinska, Deborah Kirk y Lesley Andrew

Resumen: A pesar de la evidencia empírica que apoya la hipnosis clínica para numerosas afecciones, su utilización en la asistencia sanitaria es limitada debido al escepticismo y a las ideas erróneas. Esta revisión identifica y mapea la investigación sobre las percepciones de la hipnosis clínica entre la población general, los pacientes sanitarios y, más específicamente, los pacientes con cáncer. Se realizó una búsqueda sistemática en EBSCOhost, ProQuest, PubMed y PMC, siguiendo las directrices JBI PRISMA ScR, que dio como resultado 18 artículos revisados por pares, en lengua inglesa (2000-2023). La mayoría de los estudios emplearon métodos cuantitativos, complementados por algunos cualitativos y un enfoque de métodos mixtos. Los resultados hallaron que las actitudes hacia la hipnoterapia, especialmente cuando es administrada por profesionales autorizados, son sistemáticamente positivas; sin embargo, su conocimiento sigue siendo escaso en el sector sanitario, especialmente en la atención oncológica. Aunque la hipnoterapia se consideró útil, persisten la desinformación, la falta de comprensión y el desconocimiento. Pocos estudios abordan las razones que subyacen a las opiniones de la gente o se centran en la integración de la hipnoterapia en la asistencia sanitaria. Las investigaciones sobre las actitudes hacia la hipnosis en la atención oncológica son escasas, por lo que es necesaria una mayor exploración.

Translation acknowledgments: The Spanish, French, and German translations were conducted using DeepL Translator (www.deepl.com/translator).

Introduction

Although hypnosis has been practiced for centuries, its application in healthcare has become prevalent only in recent decades (Kihlstrom, Citation2018). Clinical hypnosis is a mind-body intervention that combines neuroscience and phenomenology (understanding and working with the subjective experience of the individual; Raz, Citation2011), using the mind to modify physical function and behavioral patterns to promote physical and psychological health (Elkins et al., Citation2012). The effectiveness of hypnotherapy has been demonstrated in medical conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS; Lee et al., Citation2014; Palsson, Citation2015), migraine headaches (Flynn, Citation2018), sleep disorders, and chronic pain (Adachi et al., Citation2014; Chamine et al., Citation2018). The terms hypnosis and hypnotherapy are commonly used interchangeably (Abramowitz et al., Citation2008; PoSA, Citation2009). In this review, the terms clinical hypnosis and hypnotherapy will be used synonymously.

Hypnotherapy’s effectiveness has been researched in cancer care. Hypnosis can be incorporated into oncology, as substantial evidence supports its effectiveness in five areas of cancer treatment: (1) improving tolerance to diagnostic and medical procedures, including highly stressful procedures such as interventional radiology, surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy (Berlière et al., Citation2018; Bertrand et al., Citation2018; Potié et al., Citation2016); (2) alleviating symptoms, distress, and common cancer-related side effects associated with radiation and chemotherapy, such as fatigue, anxiety, nausea, and vomiting caused by medication (Berlière et al., Citation2018; Carlson et al., Citation2018; Kravits, Citation2015); (3) pain management (acute and chronic; Facco et al., Citation2018; Jensen, Citation2011), particularly for invasive medical procedures (Elkins et al., Citation2012; Milling, Citation2023); (4) anxiety and emotional distress induced by cancer diagnosis and treatment (Chen et al., Citation2017) and other distressing symptoms, such as depression, sleep problems; and (5) improving the quality of life (QoL; Montgomery et al., Citation2013).

Nonetheless, a detailed examination of two government-funded studies exploring the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) among patients with cancer in the United States revealed that despite 30% of participants using CAM, hypnosis was the least utilized of all the therapies investigated (Given & Given, Citation1997a, Citation1997b). Notably, not a single patient reported using hypnosis for symptom management (Fouladbakhsh et al., Citation2005). Similarly, the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) report by Clarke et al. (Citation2015), which provided national data on the use of about 15 complementary health approaches in the adult U.S. population for the years 2002, 2007, and 2012, showed a consistently low use of hypnosis (0.1–0.2%). Although limited to the U.S. population, the NHIS can be regarded as a reliable source given its extensive population size (n = 88,962; Clarke et al., Citation2015).

Despite its reported effectiveness in managing most cancer-related symptoms, clinical hypnosis appears to be underutilized in healthcare settings, including cancer care (Gamus et al., Citation2012; Montgomery et al., Citation2013). This infrequent utilization is particularly noticeable when compared to other psychosocial CAM therapies, such as herbal supplements, spiritual healing/therapy (Fouladbakhsh et al., Citation2005), deep-breathing exercises or yoga (Clarke et al., Citation2015).

The objective of this scoping review is to gather and synthesize the available literature to provide an overall understanding of the views and attitudes toward clinical hypnosis among the general population, in healthcare, and in cancer care and to identify existing gaps in knowledge on the subject. Studies on cancer care are assessed independently due to the distinct symptom profile, diverse treatment approaches, and unique psychosocial implications of a cancer diagnosis. Additionally, our literature search revealed a higher number of studies focused on cancer compared to other patient conditions. The significant physical and amplified psychological challenges patients with cancer face (Mitchell et al., Citation2011) make understanding perceptions of hypnotherapy vital. Analyzing perspectives within cancer care helps pinpoint perceived benefits and implementation hurdles, guiding future research and practice.

Methods

This scoping review aims to evaluate the extent and nature of available evidence concerning public opinions and understanding of hypnotherapy’s efficacy in healthcare. A scoping review was selected as the most suitable method for integrating a diverse body of topics on hypnotherapy, including time and location, and examining a broader area to identify and describe concepts and research knowledge gaps (Crilly et al., Citation2010). To ensure rigor and transparency, the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidelines (Peters et al., Citation2020) were followed, and the review is reported in line with the PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR; Tricco et al., Citation2018).

The scoping review method, which is applicable to all evidence sources, facilitates the use of both inductive and deductive analytical frameworks. Key concepts in this scoping review are inductively developed and subsequently organized under deductive categories according to population groups selected. This approach ensures consistency, rigor, and a structured analysis of the literature while being guided by pre-established categories or themes (Pollock et al., Citation2023). Presenting studies on general population separately from patients allows for a clear presentation of evidence, facilitates the identification of trends, and highlights potential research opportunities. Analyzing general population perceptions of hypnotherapy uncovers adoption barriers or facilitators, while examining patient perspectives and interest informs healthcare providers’ decisions about hypnotherapy’s acceptability and implementation.

Search Strategy

A systematic search was undertaken using the following search terms to capture all relevant articles: ((view) OR (opinion) OR (attitude) OR (perception) OR (interest) OR (misconception)) AND ((hypnotherap*) OR (hypnosis)). The articles were searched using controlled vocabulary and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) descriptors. Relevant literature was identified by searching primarily CINAHL plus (including PubMed, PsychINFO, PsycArticles, Psychology, and Behavioral Sciences Collection), PMC, and ProQuest. Google Scholar, Embase, and ScienceDirect were searched to include other relevant peer-reviewed articles that matched the selection criteria. Specialist hypnosis journals manually searched for any additional information were: Australian Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, Contemporary Hypnosis: The Journal of the British Society of Experimental and Clinical Hypnosis, European Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, and Sleep and Hypnosis. The Australian Journal of Clinical Hypnotherapy and Hypnosis was rejected as it was not peer-reviewed.

Eligibility Criteria

In this review, research articles using qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods were considered. Studies assessing opinions, attitudes, views, perceptions, interests, and misconceptions of hypnosis in all healthcare settings were selected for subsequent filtering. The inclusion criteria were articles in English and peer-reviewed, encompassing all international publications. A focus on peer-reviewed literature was maintained in accordance with the JBI Scoping Reviews Guidelines (Peters et al., Citation2020); however, gray literature was not included against their recommendation. This approach was adopted to ensure a high-quality standard for studies exploring attitudes and perceptions, providing reliable findings. Only peer-reviewed literature was included, representing the highest-quality and most reliable source of research evidence within a specific field (Snyder, Citation2019) to maintain rigor and relevance considering the exploratory nature of this review.

The search was restricted by publication dates ranging from 2000 to 2023 due to limited publications before 2000 and a significant increase in research on the subject since 2000. Secondary sources such as meta-analyses and systematic reviews were excluded. Studies that only examined perceptions and attitudes toward hypnosis as a phenomenon, without providing sufficient data on attitudes or opinions regarding the clinical aspects of hypnosis, were also removed. Additionally, studies focusing solely on the use of hypnosis, without delving into attitudes or perceptions, were not considered.

Study Selection

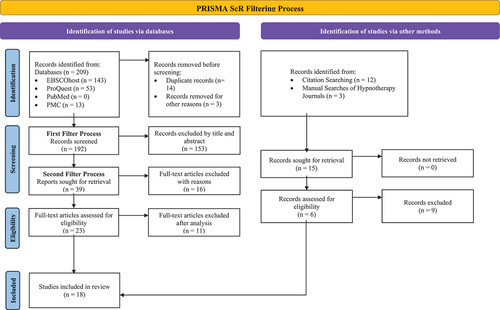

The studies were subjected to a two-tier filtering process (). The first round was to determine if the article was relevant to the search criteria. The strategy returned 209 articles through the main databases searched, with 15 more identified in the manual search. The process of inclusion/exclusion was undertaken first by examining titles alone, then titles and abstracts. Duplicates and studies that did not meet the search criteria were removed, leaving 39 articles.

The second tier assessed the full-text article’s relevance to the topic of the review. The primary objective was to identify the most relevant studies investigating opinions and attitudes on clinical hypnosis/hypnotherapy among the general public, patients in healthcare, and individuals undergoing cancer care. The search was conducted through a close reading of the full article. Sixteen studies were excluded as they did not satisfy the selection criteria. Lastly, a thorough examination of each article’s study findings was conducted, resulting in the exclusion of 11 articles identified through databases and nine from manual searches. Eighteen articles met the criteria and are included in the review. In this scoping review, no evaluation of study quality was conducted. This is because the aim of the review was to provide a comprehensive overview of all the available literature, irrespective of study quality (Munn et al., Citation2018).

Results

A preliminary search of the literature reveals that research with the general population mostly focuses on beliefs and attitudes toward hypnosis as a phenomenon (Carvalho et al., Citation2007; Gow et al., Citation2006; Green et al., Citation2006; Milling, Citation2012; Montgomery et al., Citation2018; Yu, Citation2004), the relationship between attitudes and hypnotic responsiveness (Accardi et al., Citation2013; Green, Citation2012; Molina & Mendoza, Citation2006; Molina-Peral et al., Citation2020; Shimizu, Citation2014), and on how expectations and beliefs predict outcomes (Green & Lynn, Citation2010) rather than the perceptions on clinical hypnosis and its efficacy in healthcare. Some studies focused on hypnosis within the broader CAM landscape (Boutin et al., Citation2000; Furnham, Citation2000; Harris & Roberts, Citation2008; Verhoef et al., Citation2005). Limited research has been undertaken on the perceptions and attitudes of individuals with cancer toward hypnotherapy as supportive care during treatment.

Eighteen articles met the selection criteria. Notably, this scoping review included a mixed methods study, in which quantitative findings were obtained from surveys conducted among the general population and qualitative findings from interviews conducted among patients with cancer. This dual-methodology study is considered unique in its approach and provides insights into two distinct population groups. The findings of this single article were diverse enough, in terms of the population groups they represented, that for clarity in presenting the findings, they were treated as two separate studies. Consequently, the review comprises a total of 19 studies, divided into three broad categories: (1) those that addressed the views among general population (n = 4; ); (2) those that focused on patients in healthcare (n = 10; ); and (3) in cancer care (n = 5; ).

Table 1. General Population

Table 2. Healthcare

Table 3. Cancer Care

Studies were conducted in various countries, including Spain, Scotland, Germany, Norway, Australia, Canada, and the UK, with the majority being conducted in the United States (n = 7). Studies were evenly spread among the years between 2000 and 2023. All but two studies drew exclusively on quantitative data, specifically studies that used cross-sectional surveys using standardized questionnaires. A summary of all included studies is in the summary tables.

General Population’s Views on Hypnotherapy

Four studies of the general public have been included, through which different perspectives on clinical hypnosis can be observed. Lind et al. (Citation2021) and Palsson et al. (Citation2019) focused on the views of the general adult population; Molina and Mendoza (Citation2006) examined psychology students who signed up for hypnosis training; and Emslie et al. (Citation2002) assessed views and perceptions of hypnosis in addition to other CAM therapies.

The two studies that specifically focused on the views of the public on clinical hypnosis surveyed approximately 1,000 adults each in the United States (Palsson et al., Citation2019) and Norway (Lind et al., Citation2021). These studies featured large sample sizes, ensuring a balanced representation of age and geographical distribution in the United States (based on the nine U.S. Census Bureau divisions) and age, education, income, and region division in Norway. By preventing self-selection bias, the studies provide a reliable insight into public perception. Both studies found that a significant proportion of the participants would consider seeking clinical hypnosis. In the study by Palsson et al. (Citation2019), 77.8% of respondents perceived clinical hypnosis as a useful modality in one or more areas of clinical application, while only 12.8% held a negative perception of it. Almost half of all respondents acknowledged hypnosis as a real phenomenon with moderate to strong scientific evidence, and over half (54.9%) of the participants who have not undergone hypnosis were willing to consider it. However, only 7.6% of all participants had undergone hypnosis. Similarly, Lind et al. (Citation2021) reported that 67% of participants expressed willingness to accept hypnosis in a clinical setting, although only 8% had previous experience with hypnosis. These findings suggest that the general public holds a positive view of clinical hypnosis as a supplementary approach to healthcare treatment. Although personal experience with hypnosis was limited, the overall perception indicated a receptiveness to its potential benefits.

Molina and Mendoza (Citation2006) reported that participants with university-related knowledge of or experience with hypnosis held more positive views toward the practice than those without such experience. Exposure to hypnosis training or academic information resulted in more positive attitudes and eliminated the fear of hypnosis. Common adjectives used to describe hypnosis by study participants included interesting and therapeutic. However, among the negative descriptors, unknown, mystifying and discredited were most frequently chosen, indicating mixed views toward hypnosis. Emslie et al. (Citation2002) incorporated hypnosis in their assessment of interest and use of various CAM therapies. Two population-based surveys were conducted in northeast Scotland in 1993 and 1999. An assessment of changes six years after the initial survey revealed that 74% to 79% of respondents were aware of hypnotherapy. However, less than 5% utilized hypnosis, primarily using it for smoking cessation, stress management, and the alleviation of phobias. Approximately 37.7% believed that hypnotherapy should be provided by the U.K. National Health Service, with no significant change reported between 1993 and 1999 (Emslie et al., Citation2002).

Patients’ Views on Hypnotherapy

Ten studies investigated perceptions of clinical hypnosis in healthcare. Most studies conducted with patients (Barling & De Lucchi, Citation2004; Donnet et al., Citation2022; Glaesmer et al., Citation2015; Harris & Roberts, Citation2008; Hermes et al., Citation2004; Hollingworth, Citation2012; Miller et al., Citation2011; Pettigrew et al., Citation2004; Wang et al., Citation2003) showed positive attitudes toward hypnotherapeutic treatment, aligning with studies of the general public.

Hypnotherapy in Dental Procedures

Two studies investigating the use of hypnosis in dentistry were carried out in Germany. One study, involving 102 dental patients, revealed that 90% held positive opinions of hypnosis (Glaesmer et al., Citation2015). Conducted on patients undergoing tooth extraction, 80% of those who received hypnosis believed it reduced their fear during the procedure. Similar findings were reported by Hermes et al. (Citation2004) who focused on dental patients undergoing oral surgery. The study did not incorporate hypnosis but instead examined patients’ perceptions and interest in this technique. Out of the 310 patients surveyed, 86.5% agreed on the value of further research into the use of hypnosis in healthcare. When posed with the option of combining clinical hypnosis with local anesthesia before oral surgery, 71.6% were in favor. Only 6.1% rejected clinical hypnosis entirely, and 78.4% viewed hypnosis as a beneficial addition to clinical treatment. When asked about the utilization of hypnosis, 31% rated it as very useful and an additional 33.2% considered it generally useful. The majority of respondents were not only aware of the clinical application of hypnosis but also held positive attitudes toward it. However, some of these positive views were contingent on the availability of skilled guidance. Nevertheless, Glaesmer et al. (Citation2015) found that while 90% of respondents held positive attitudes toward hypnosis, only a fraction of them (22.5%) considered hypnosis to be grounded in science. These findings suggest that positive opinions toward hypnosis stem primarily from the belief that it can help treat clinical and psychological issues (Glaesmer et al., Citation2015; Hermes et al., Citation2004).

Hypnotherapy for Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

A study by Harris and Roberts (Citation2008) found hypnosis to be perceived as helpful for IBS, as 63.7% of IBS sufferers considered hypnotherapy a useful treatment modality. In a study by Donnet et al. (Citation2022) on 150 IBS patients, 55.3% of patients were anticipating hypnosis to be helpful for their condition prior to using hypnotherapy treatment. However, after the hypnotherapeutic intervention, 60.7% of all patients stated their opinion on hypnotherapy had changed to more positive and enthusiastic, 93.3% would use hypnotherapy for reasons other than IBS, and 100% would recommend it. What is more, 74% scored their recommendation as 10 out of 10.

Hypnotherapy in Other Medical Procedures

According to Hollingworth (Citation2012), hypnotherapy has a high level of acceptance among pregnant women in Australia. Their study conducted on 337 pregnant women found hypnosis to be perceived as a useful modality to reduce labor pain (90%), decrease anxiety (90%), and improve the overall experience of childbirth (50%; Hollingworth, Citation2012). In a study conducted in the United States involving pre-colonoscopy patients (n = 213) who used hypnosis before their procedure, positive perceptions of hypnosis were reported by 69.9% of participants. Nevertheless, approximately one-third (31.1%) of all participants reported unfavorable perceptions for unspecified reasons (Miller et al., Citation2011).

Hypnotherapy as Part of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM)

In addition to the study among IBS sufferers carried out by Harris and Roberts (Citation2008), three studies were conducted among patients on the use of clinical hypnosis among other CAMs. In one of these studies, performed with inpatients and outpatients undergoing surgery, 57% (n = 706) of patients used CAM at least once, and 25% were using CAM at the time of the survey. Wang et al. (Citation2003) found that although 21% expressed willingness to accept hypnosis as part of anesthesia care, only 0.6% were currently using it.

In a study involving 567 outpatients at a prominent municipal medical center in United States, Boutin et al. (Citation2000) found that while 42% reported using alternative therapies, hypnotherapy was utilized by a mere 3% of the respondents. It is noteworthy that 35% of patients were not aware of hypnotherapy, and 19% believed hypnotherapy should be offered. Similarly, Pettigrew et al. (Citation2004) conducted a study among 250 patients attending a women’s health clinic, revealing that only 4.8% of women were using hypnosis as part of their therapies, even though they rated its effectiveness as 3.04 out of 5. When asked to rate their knowledge and perceived effectiveness of 20 CAM therapies, hypnosis ranked near the bottom in both categories. However, the limited generalizability of the findings should be considered, as the sample included only females and data were collected in a single clinic. These studies further highlight the low usage of hypnotherapy as a CAM therapy, despite a considerable percentage of patients thinking it should be available.

Barriers to Hypnotherapy Acceptance

Several barriers to the acceptance of hypnotherapy have been identified in the literature, including skepticism and fear, as well as perceptions of hypnotherapy as being expensive and time-consuming (Harris & Roberts, Citation2008). Additionally, misconceptions about hypnosis, particularly negative or false beliefs, can deter individuals from considering it as a therapeutic option. These include fears of losing control during hypnosis, concerns about potential risks, and the mistaken view of hypnosis as a magical, effortless cure. Such beliefs might lead to unrealistic expectations, as shown in the findings by Mendoza et al. (Citation2017). These findings are further supported by multiple studies, including those by Carvalho et al. (Citation2007) and Green (Citation2012), which illustrate that even participants who view hypnosis positively and find it useful may still harbor these misconceptions. Moreover, the lack of information (61.3%) and uncertainty about its therapeutic efficacy (53%) were found to be the main reasons for rejecting therapeutic hypnosis in dentistry (Hermes et al., Citation2004). Ensuring the demonstration and validation of hypnosis’s effectiveness in clinical settings can further aid in alleviating concerns regarding its therapeutic efficacy.

Views on Clinical Hypnosis in Cancer Care

Five studies focused on the views of clinical hypnosis in cancer care, which included individuals in active cancer treatment, survivorship, and outpatients’ opinions on hypothetically being diagnosed with cancer. Sohl et al. (Citation2010) examined the views of 115 adults recruited from a public area in a large metropolitan hospital in United States, assessing how likely they would be to use hypnosis to control the side effects of cancer and its treatment if they were to be diagnosed with cancer. A majority (89%) of participants were open to hypnosis as a tool to control the side effects of cancer therapy. Moreover, the inclination to use hypnosis appeared unrelated to variables such as gender, ethnicity, educational level, or age. This assertion contrasts with the findings of Zaza et al. (Citation2005). In their study, comprised of 292 patients with cancer participating in face-to-face individual interviews, participants were assessed on seven coping strategies. Only 13 out of the 292 patients had employed or were currently employing hypnosis. Within this patient group, 26% were unaware of the use of hypnosis in association with cancer therapy, while 19% expressed skepticism toward the practice. This indicates a notable discrepancy between the intentions expressed in a hypothetical scenario and the actual utilization of hypnosis when diagnosed with cancer.

Three other studies explored the experiences of hypnosis among participants with cancer. Taylor and Ingleton (Citation2003) conducted eight in-depth, semi-structured, qualitative interviews with women diagnosed with breast (n = 7) and colon (n = 1) cancer. The study focused on patients’ views after having participated in hypnotherapeutic interventions. The findings suggest that combining therapies as supportive care in cancer treatment helped patients cope. Patients appreciated an opportunity to express their feelings, and hypnotherapy helped them relax, sleep better, and resolve chemotherapy-related fear and side effects. The patients also reported having trouble with getting a referral for hypnotherapy, although the specific reasons for these challenges were not detailed. A limitation of the study was the lack of assessment of patients’ attitudes prior to starting the program. Consequently, it is impossible to determine whether these attitudes have changed (Taylor & Ingleton, Citation2003).

These findings are further supported by a similar pilot study conducted in Norway by Lind et al. (Citation2021), which involved five interviews with patients with cancer as part of a mixed- methods study. In this study, women scheduled for breast cancer surgery received hypnosis prior to mastectomy or lumpectomy. All participants reported positive experiences related to hypnosis, and none described unpleasant side effects or postoperative pain after surgery. Nonetheless, there was no evaluation of attitudes conducted before the intervention from which to make a comparison.

Mendoza et al. (Citation2017) conducted a similar study in United States, assessing the attitudes of patients with cancer toward hypnosis in relation to how attitudes affect the treatment outcome. The sample consisted of patients diagnosed with various types of cancer, with a majority (66%) being gynecologic cancer, either in active treatment or survivorship. The study used a crossover design, where 44 participants were randomized into two groups: one receiving hypnosis as an intervention and the other an education control condition. All participants received both treatments in a counterbalanced order. The study results demonstrated that hypnosis intervention paired with cognitive behavioral therapy improved attitudes toward hypnosis, with the positive changes remaining consistent at a 3–month follow-up. Specifically, when examining the “Help” factor which measures participants’ beliefs about the helpfulness of hypnosis, there was a notable increase in belief scores from pre-treatment to post-treatment, and this increased belief was sustained at the 3–month follow-up. Furthermore, these shifts in attitudes were correlated with improvements in treatment outcomes, reinforcing the importance of addressing these perceptions throughout treatment. The insights derived from this could aid clinicians in addressing specific misconceptions reported by patients (Accardi et al., Citation2013).

Discussion

The scoping review revealed a limited but insightful body of literature on the perceptions of clinical hypnosis among the general population and patients alike. The observed trends indicate that while clinical hypnosis has been perceived as effective, its utilization remains significantly low (Emslie et al., Citation2002; Pettigrew et al., Citation2004; Wang et al., Citation2003). The scholarly research commonly presented estimates of the use of hypnosis among complementary health approaches (Clarke et al., Citation2015). Notably, the perception has not changed, and the use of clinical hypnosis has not increased in over 20 years.

In healthcare settings, the acceptance of clinical hypnosis is high, even among individuals with no prior experience of hypnosis. After hypnotherapeutic intervention, attitudes are found to be even more positive and enthusiastic than they were before intervention (Donnet et al., Citation2022; Mendoza et al., Citation2017). Three studies found that only a minority of patients reject hypnotherapeutic intervention (Hermes et al., Citation2004; Miller et al., Citation2011; Palsson et al., Citation2019). The reasons behind rejection are mostly undetermined, other than having strong negative misconceptions and exposure to TV and stage hypnosis, with Gow et al. (Citation2006) affirming that such misconceptions influenced by media and stage hypnosis can foster negative attitudes. Contributing factors to the low adoption of clinical hypnosis include misconceptions about the nature of hypnosis, lack of understanding about its therapeutic applications, and limited exposure to its benefits in healthcare settings (Harris & Roberts, Citation2008; Hermes et al., Citation2004). The pattern of high awareness and perceived effectiveness coupled with low actual usage, suggests that further research is needed to explore the reasons behind the underutilization of hypnosis as a treatment option.

While it is encouraging to see a growing number of studies focusing on patients in healthcare rather than the general population, indicating an increasing interest in hypnosis research within healthcare, the amount of research conducted in a variety of healthcare contexts remains limited. This is also true for studies conducted specifically among individuals with cancer. The results indicate that among the population groups presented in studies on the perceptions and use of clinical hypnosis, patients had less fear and prejudice against hypnosis than the general public. They might also be more invested in wanting hypnosis to help with their conditions.

The lack of knowledge and scientific information on hypnosis among the public has been a contributing factor to incorrect or low expectancies about the efficacy of hypnotic treatment reported over a long period, with reports of information being obtained primarily from media, friends, and family, rather than from licensed healthcare providers (Pettigrew et al., Citation2004). Yet, when deciding on hypnotherapeutic intervention, primary care physicians are considered the most influential source of information, and referrals made by a clinician are most readily accepted (Harris & Roberts, Citation2008).

Hypnosis has also been viewed more positively when conducted by a licensed healthcare provider or an accredited professional (Gow et al., Citation2006). This suggests healthcare professionals expanding their theoretical and practical knowledge of hypnosis would positively influence the public views.

Clinical Implications

This scoping review underscores the importance of fostering an accurate and up-to-date understanding of hypnotherapy among patients, particularly in cancer care, where hypnosis appears most needed and yet least used. Despite ample empirical evidence supporting hypnotherapy’s effectiveness across various symptoms and clinical applications, there remains limited insight into the reasons behind its underutilization in healthcare settings. Although the examined data were too heterogeneous for drawing highly specific conclusions, the synthesis reveals a promising outlook for integrating clinical hypnosis into standard healthcare practices across diverse cultural contexts.

Compared to other CAM therapies, hypnosis seems to be scarcely employed (Clarke et al., Citation2015; Fouladbakhsh et al., Citation2005). One possible reason is that hypnosis is not perceived as a pleasant and enjoyable experience, unlike other CAM techniques such as yoga and meditation, which are frequently portrayed as relaxing and spa-like experiences (Montgomery et al., Citation2018). Only a few studies have explored the perceptions and attitudes of patients with cancer toward hypnotherapy as supportive care during treatment, despite evidence supporting its efficacy in managing cancer-related symptoms, especially during chemotherapy (Richardson et al., Citation2007).

Not offering hypnosis as an option in healthcare settings may hinder patients’ autonomy in choosing their preferred treatment approach. This is particularly relevant as non-pharmacological approaches are being increasingly promoted, but hypnotherapy remains underutilized (Fouladbakhsh et al., Citation2005; Montgomery et al., Citation2018). Further research is needed to more clearly understand why hypnosis has not been widely adopted or integrated into healthcare. This additional research, particularly examining the potential benefits of hypnotherapy in cancer care, would contribute valuable insights to the growing body of evidence supporting the role of hypnosis in enhancing the well-being of patients with cancer. The inclusion of these studies in this scoping review emphasizes the need for further exploration and understanding of hypnotherapy’s role in healthcare settings, specifically cancer care.

The variations in awareness and usage observed across the studies signal the need for improved education and promotion of hypnosis as a viable treatment option within the medical community. This would empower patients to make informed decisions about their care and encourage healthcare professionals to consider hypnotherapy as a valuable non-pharmacological approach to symptom management and overall well-being.

Study Limitations

While published research suggests significant interest and positive attitudes toward hypnosis and its therapeutic potential, this review presents several limitations that may impact the findings. The exclusion of non-English language journals might have influenced the international representation of the findings by overlooking valuable research conducted in other languages and cultural contexts, thus limiting the comprehensiveness and diversity of perspectives on hypnotherapy’s efficacy in healthcare settings. Although studies involving various nationalities were included, only a few of the reviewed studies incorporated a sufficiently broad and large sample size, providing limited information on clinical hypnosis. Some areas of healthcare, such as colonoscopy, are represented by only one study on perceptions.

The absence of comparisons among individuals with different education and income levels in the reviewed studies raises the question of whether certain groups may hold more positive attitudes toward hypnosis due to education (i.e. higher education in psychology) or ability to afford the treatment modality. Additionally, the small sample sizes, participant recruitment limited to one location or clinic, and the overrepresentation of women in these studies pose limitations in terms of generalizability and the potential influence of gender on the findings. To address these limitations, future research should include other healthcare settings, more diverse populations, and larger sample sizes. It should also explore potential differences in attitudes across various demographic groups.

Conclusion

The studies in this scoping review indicate that clinical hypnosis has garnered interest across various healthcare domains. The research demonstrates generally positive attitudes among the general public and patients in multiple clinical fields. These studies emphasize that the perception of clinical hypnosis is influenced by factors such as knowledge, exposure, and accessibility. This review also unveiled a scarcity of published research focusing on people’s views and attitudes among the general public but also in the field of cancer care. Hypnosis has been proven effective for numerous medical conditions and symptoms, and it can significantly support the physical and psychological well-being of individuals living with cancer. However, given the limited number of available studies and the apparent impact of a lack of knowledge about the benefits of hypnosis, more research is warranted. This review may aid future studies in assessing the enablers and barriers that could impact the use of hypnosis as an adjunct in healthcare and cancer care settings. Research should also explore the reasons why patients do not elect hypnosis as part of their treatment. To promote the acceptance and utilization of hypnotherapy as a valuable therapeutic tool, further research should investigate the underlying reasons for its limited use, potential barriers, and the role of education in shaping perceptions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Davina Porock for her valuable input and contributions to this article through the course of its development.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study. This work is based on existing literature rather than original data collection, so there is no specific dataset to share.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abramowitz, E. G., Barak, Y., Ben-Avi, I., & Knobler, H. Y. (2008). Hypnotherapy in the treatment of chronic combat-related PTSD patients suffering from insomnia: A randomized, zolpidem-controlled clinical trial. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 56(3), 270–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207140802039672

- Accardi, M., Cleere, C., Lynn, S. J., & Kirsch, I. (2013). Placebo versus “standard” hypnosis rationale: Attitudes, expectancies, hypnotic responses, and experiences. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 56(2), 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2013.769087

- Adachi, T., Fujino, H., Nakae, A., Mashimo, T., & Sasaki, J. (2014). A meta-analysis of hypnosis for chronic pain problems: A comparison between hypnosis, standard care, and other psychological interventions. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 62(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2013.841471

- Barling, N. R., & De Lucchi, D. A. G. (2004). Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about clinical hypnosis. Australian Journal of Clinical & Experimental Hypnosis, 32(1), 36–52. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.200406623

- Berlière, M., Roelants, F., Watremez, C., Docquier, M. A., Piette, N., Lamerant, S., Megevand, V., Van Maanen, A., Piette, P., Gerday, A., & Duhoux, F. P. (2018). The advantages of hypnosis intervention on breast cancer surgery and adjuvant therapy. Breast, 37, 114–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2017.10.017

- Bertrand, A. S., Iannessi, A., Buteau, S., Jiang, X. Y., Beaumont, H., Grondin, B., & Baudin, G. (2018). Effects of relaxing therapies on patient’s pain during percutaneous interventional radiology procedures. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 7(4), 455–462. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm.2018.07.02

- Boutin, P. D., Buchwald, D., Robinson, L., & Collier, A. C. (2000). Use of and attitudes about alternative and complementary therapies among outpatients and physicians at a municipal hospital. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 6(4), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1089/10755530050120709

- Carlson, L. E., Toivonen, K., Flynn, M., Deleemans, J., Piedalue, K. A., Tolsdorf, E., & Subnis, U. (2018). The role of hypnosis in cancer care. Current Oncology Reports, 20(12), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-018-0739-1

- Carvalho, C., Capafons, A., Kirsch, I., Espejo, B., Mazzoni, G., & Leal, I. (2007). Factorial analysis and psychometric properties of the revised Valencia Scale of Attitudes and Beliefs Towards Hypnosis‐client version. Contemporary Hypnosis, 24(2), 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/ch.332

- Chamine, I., Atchley, R., & Oken, B. S. (2018). Hypnosis intervention effects on sleep outcomes: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 14(2), 271–283. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.6952

- Chen, P. Y., Liu, Y. M., & Chen, M. L. (2017). The effect of hypnosis on anxiety in patients with cancer: A meta-analysis. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 14(3), 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12215

- Clarke, T. C., Black, L. I., Stussman, B. J., Barnes, P. M., & Nahin, R. L. (2015). Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012. National Health Statistics Reports, 79, 1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25671660

- Crilly, T., Jashapara, A., & Ferlie, E. (2010). Research utilisation and knowledge mobilisation: A scoping review of the literature. National Institute for Health Research Service Delivery and Organisation Programme. https://pure.royalholloway.ac.uk/ws/files/17846460/Jashapara_Research_utilisation_2010.pdf

- Donnet, A. S., Hasan, S. S., & Whorwell, P. J. (2022). Hypnotherapy for irritable bowel syndrome: Patient expectations and perceptions. Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology, 15. https://doi.org/10.1177/17562848221074208

- Elkins, G., Johnson, A., & Fisher, W. (2012). Cognitive hypnotherapy for pain management. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 54(4), 294–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2011.654284

- Emslie, M. J., Campbell, M. K., & Walker, K. A. (2002). Changes in public awareness of, attitudes to, and use of complementary therapy in Northeast Scotland: Surveys in 1993 and 1999. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 10(3), 148–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0965229902000663

- Emslie, M., Campbell, M., & Walker, K. (1996). Complementary therapies in a local healthcare setting. Part I: Is there real public demand? Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 4(1), 39–42.

- Facco, E., Casiglia, E., Zanette, G., & Testoni, I. (2018). On the way of liberation from suffering and pain: Role of hypnosis in palliative care. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 7(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm.2017.04.07

- Flynn, N. (2018). Systematic review of the effectiveness of hypnosis for the management of headache. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 66(4), 343–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2018.1494432

- Fouladbakhsh, J. M., Stommel, M., Given, B. A., & Given, C. W. (2005). Predictors of use of complementary and alternative therapies among patients with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 32(6), 1115–1122. https://doi.org/10.1188/05.onf.1115-1122

- Furnham, A. (2000). How the public classify complementary medicine: A factor analytic study. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 8(2), 82–87. https://doi.org/10.1054/ctim.2000.0355

- Gamus, D., Kedar, A., & Kleinhauz, M. (2012). Hypnosis in palliative care. Progress in Palliative Care, 20(5), 278–283. https://doi.org/10.1179/1743291x12y.0000000025

- Given, B., & Given, C. (1997a). Family home care for cancer—A community-based model (Grant# R01 NR/CA01915). Funded by the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Nursing Research and the National Cancer Institute in collaboration with the Walther Cancer Institute, Indianapolis, IN.

- Given, B., & Given, C. (1997b). Rural partnership linkage for cancer care (Grant# R01 NR/CA56338). Funded by the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Nursing Research and the National Cancer Institute in collaboration with the Walther Cancer Institute, Indianapolis, IN.

- Glaesmer, H., Geupel, H., & Haak, R. (2015). A controlled trial on the effect of hypnosis on dental anxiety in tooth removal patients. Patient Education and Counseling, 98(9), 1112–1115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.05.007

- Gow, K., Mackie, C., Clohessy, D., Cowling, T., Maloney, R., & Chant, D. (2006). Attitudes and opinions about hypnosis in an Australian city. Australian Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 34(2), 162. https://www.londonhypnotherapyuk.com/publications/anxiety-and-sleeping-disorders-paper-final-proofs.pdf#page=48

- Green, J. P. (2012). The Valencia Scale of Attitudes and Beliefs Toward Hypnosis–client version and hypnotizability. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 60(2), 229–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2012.648073

- Green, J. P., & Lynn, S. J. (2010). Hypnotic responsiveness: Expectancy, attitudes, fantasy proneness, absorption, and gender. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 59(1), 103–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2011.522914

- Green, J. P., Page, R. A., Rasekhy, R., Johnson, L. K., & Bernhardt, S. E. (2006). Cultural views and attitudes about hypnosis: A survey of college students across four countries. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 54(3), 263–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207140600689439

- Harris, L. R., & Roberts, L. (2008). Treatments for irritable bowel syndrome: Patients’ attitudes and acceptability. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 8(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-8-65

- Hermes, D., Hakim, S. G., & Sieg, P. (2004). Acceptance of medical hypnosis by oral and maxillofacial patients. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 52(4), 389–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207140490886227

- Hollingworth, I. (2012). Knowledge and attitudes of pregnant women regarding hypnosis. Australian Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 40(1), 43. https://hipnosisclinica.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/australian-journal-of-clinical-and-experimental-hypnosis-11-2012.pdf#page=49

- Jensen, M. P. (2011). Hypnosis for chronic pain management: Therapist guide. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/med:psych/9780199772377.003.0006

- Kihlstrom, J. (2018). Hypnosis: Applications. In Reference module in neuroscience and biobehavioral psychology. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-809324-5.21772-0

- Kravits, K. G. (2015). Hypnosis for the management of anticipatory nausea and vomiting. Journal of the Advanced Practitioner in Oncology, 6(3), 225. https://doi.org/10.6004/jadpro.2015.6.3.4

- Lee, H. H., Choi, Y. Y., & Choi, M. G. (2014). The efficacy of hypnotherapy in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 20(2), 152–162. https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm.2014.20.2.152

- Lind, S. B., Jacobsen, H. B., Solbakken, O. A., & Reme, S. E. (2021). Clinical hypnosis in medical care: A mixed-method feasibility study. Integrative Cancer Therapies, 20, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/15347354211058678

- Mendoza, M. E., Capafons, A., & Jensen, M. P. (2017). Hypnosis attitudes: Treatment effects and associations with symptoms in individuals with cancer. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 60(1), 50–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2017.1300570

- Miller, S. J., Schnur, J. B., Montgomery, G. H., & Jandorf, L. (2011). African-Americans’ and Latinos’ perceptions of using hypnosis to alleviate distress before a colonoscopy. Contemporary Hypnosis & Integrative Therapy, 28(3), 196. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26566440

- Milling, L. S. (2012). The Spanos attitudes toward hypnosis questionnaire: Psychometric characteristics and normative data. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 54(3), 202–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2011.631229

- Milling, L. S. (2023). Hypnosis for acute and procedural pain. In L. S. Milling (Ed.), Evidence-based practice in clinical hypnosis (pp. 77–107). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000347-004

- Mitchell, A. J., Chan, M., Bhatti, H., Halton, M., Grassi, L., Johansen, C., & Meader, N. (2011). Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: A meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncology, 12(2), 160–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(11)70002-x

- Molina, J. A., & Mendoza, M. E. (2006). Change of attitudes towards hypnosis after a training course. Australian Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 34(2), 146. https://www.londonhypnotherapyuk.com/publications/anxiety-and-sleeping-disorders-paper-final-proofs.pdf#page=32

- Molina-Peral, J. A., Rodríguez, J. S., Capafons, A., & Mendoza, M. E. (2020). Attitudes toward hypnosis based on source of information and experience with hypnosis. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 62(3), 282–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2019.1584741

- Montgomery, G. H., Schnur, J. B., & Kravits, K. (2013). Hypnosis for cancer care: Over 200 years young. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 63(1), 31–44. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21165

- Montgomery, G. H., Sucala, M., Dillon, M. J., & Schnur, J. B. (2018). Interest and attitudes about hypnosis in a large community sample. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, & Practice, 5(2), 212–220. https://doi.org/10.1037/cns0000141

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- Palsson, O. S. (2015). Hypnosis treatment of gastrointestinal disorders: A comprehensive review of the empirical evidence. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 58(2), 134–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2015.1039114

- Palsson, O., Twist, S., & Walker, M. (2019). A national survey of clinical hypnosis views and experiences of the adult population in the United States. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 67(4), 428–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2019.1649538

- Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18(10), 2119–2126. https://doi.org/10.11124/jbies-20-00167

- Pettigrew, A. C., King, M. O. B., McGee, K., & Rudolph, C. (2004). Complementary therapy use by women’s health clinic clients. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, 10(6), 50. https://www.proquest.com/docview/204828855/abstract/2FFF09B96BDA45A1PQ/1?accountid=7014

- Pollock, D., Peters, M. D., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Alexander, L., Tricco, A. C., Evans, C., de Moraes, É. B., Godfrey, C. M., Pieper, D., Saran, A., Stern, C., & Munn, Z. (2023). Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 21(3), 520–532. https://doi.org/10.11124/jbies-22-00123

- PoSA. (2009). A review of the department of health’s report into hypnosis: Definition of hypnosis: ‘Hypnosis’ and ‘hypnotherapy’ are often used interchangeably. http://www.parliament.sa.gov.au/NR/rdonlyres/77C502EC-F1C3-40CA-9CE7-E3466A091ABA/13770/29thReportReviewofDeptofHealthReportintoHypnsosi.pdf

- Potié, A., Roelants, F., Pospiech, A., Momeni, M., & Watremez, C. (2016). Hypnosis in the perioperative management of breast cancer surgery: Clinical benefits and potential implications. Anesthesiology Research and Practice, 2016, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/2942416

- Raz, A. (2011). Does neuroimaging of suggestion elucidate hypnotic trance? International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 59(3), 363–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2011.570682

- Richardson, J., Smith, J., McCall, G., Richardson, A., Pilkington, K., & Kirsch, I. (2007). Hypnosis for nausea and vomiting in cancer chemotherapy: A systematic review of the research evidence. European Journal of Cancer Care, 16(5), 402–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00736.x

- Shimizu, T. (2014). A causal model explaining the relationships governing beliefs, attitudes, and hypnotic responsiveness. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 62(2), 231–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2014.869142

- Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104, 333–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

- Sohl, S. J., Stossel, L., Schnur, J. B., Tatrow, K., Gherman, A., & Montgomery, G. H. (2010). Intentions to use hypnosis to control the side effects of cancer and its treatment. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 53(2), 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2010.10404331

- Taylor, E. E., & Ingleton, C. (2003). Hypnotherapy and cognitive‐behaviour therapy in cancer care: The patients’ view. European Journal of Cancer Care, 12(2), 137–142. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2354.2003.00371.x

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Tunçalp, Ö. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/m18-0850

- Verhoef, M., Epstein, M., Brundin-Mather, R., Boon, H., & Jones, A. (2005). Introducing medical students to CAM: Response to Oppel et al. Canadian Family Physician, 51(2), 191. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15751558

- Wang, S. M., Caldwell-Andrews, A. A., & Kain, Z. N. (2003). The use of complementary and alternative medicines by surgical patients: A follow-up survey study. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 97(4), 1010–1015. https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ane.0000078578.75597.f3

- Yu, C. K. C. (2004). Beliefs and attitudes of Chinese regarding hypnosis and its applications. Contemporary Hypnosis, 21(3), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1002/ch.295

- Zaza, C., Sellick, S. M., & Hillier, L. M. (2005). Coping with cancer: What do patients do? Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 23(1), 55–73. https://doi.org/10.1300/j077v23n01_04