Abstract

Corporations can be powerful engines of economic prosperity, but also for the public good more broadly conceived. But they need to be properly incentivized to fulfil these missions. We propose an innovative plan called the Corporate Social Assessment (CSA). Every four years, a randomly selected Citizens’ Assembly will meet to decide a grading scheme for assessing companies’ conduct. At the end of the cycle, a professional assessment body will grade the companies and rank them. The ranking will be the basis for subsidies to higher-tier companies, to be paid out of a fund to which all companies will contribute, to create a race to the top which financially rewards corporations taking public concerns seriously. The CSA radicalizes the corporate license to operate. To retain legitimacy in the eyes of wider segments of society, the proposal aims to democratize the way we hold corporations accountable for the power they wield.

1. Introduction

In 2019, Abigail Disney, the grand-niece of Walt Disney, said it was ‘insane’ that the Disney company’s boss was paid sixty-six million dollars in one year (Edgecliffe-Johnson Citation2019). She pointed out that this was more than a thousand times the amount a typical Disney worker is paid. She might have drawn attention to other dubiously ethical conduct at Disney. Leaks revealed that Disney has been funneling its profits through tax havens in Luxembourg and the Cayman Islands to try and reduce its taxes in Europe and the USA (Fitzgerald et al. Citation2014). And in the 2016 US elections, Disney spent 15 million dollars on lobbying and campaign contributions, donating to both Hilary Clinton and Donald Trump (Center for Responsive Politics Citation2016). Strikingly, all three issues (pay disparity, tax avoidance, and political favours), were completely legal. Cases where the current regulatory system has nothing to say about corporate conduct widely considered outrageous are common.

Corporations can be powerful engines of prosperity in a narrow economic sense, and for public value more broadly conceived. But they need to be properly incentivized to fulfil these missions. For a variety of reasons, current systems of incentives too often do not deliver. In response to widespread declining trust, big businesses have been making more noise about their ethics. For example, the Business Roundtable (Citation2019) (an association of leading US corporations) recently issued a new Statement on Corporate Purpose which pledged to serve a wide group of stakeholders (updating their older shareholder-centric statement). However, such initiatives lack credibility, and are often dismissed as ‘greenwashing’. Moreover, even taken seriously, they imply a problematic degree of unaccountable discretionary power for company directors. Something more radical is required.

We propose an innovative plan that we call the Corporate Social Assessment (CSA). Every four years, all large corporations will be graded according to their contribution to public value, with financial consequences attached to their grades. At the start, a randomly selected Citizens’ Assembly will meet to decide a grading scheme for assessing companies’ conduct. This grading scheme lays down the criteria of public value to which companies will be held. During the four years, companies work on realizing these criteria in their corporate activities. At the end, a professional assessment body will grade the companies and rank them according to their grades in ten equally sized tiers. The ranking will be the basis for subsidies to higher-tier companies, which will be paid out of a fund (the ‘CSA Fund’) to which all companies will contribute. The goal of these financial incentives is to create a race to the top which financially rewards corporations taking public concerns seriously.

We start with an overview of developments in the fields of regulation, corporate social responsibility, and environmental, social and governance reporting. At the end of this section, we situate the CSA proposal with respect to these developments. Section three then follows with a full sketch of the main features of our proposal. These two sections need to be read in light of each other (readers who first want to read the full proposal can read section 3 first). Out of this sketch flows a series of key challenges and motivations for the CSA. These we tackle in-depth in the remaining sections, drawing on literature on ranking and commensuration (section four), competition for public value (section five) and deliberative mini-publics (section six).

We would like to emphasize that we conceive of this as a programmatic paper. It is meant to stimulate discussion of the proposal’s desirability and feasibility, and its relation to other proposals and developments in the field. We have tried to incorporate as many considerations and objections as we could anticipate in the space of a paper, but we recognize that many of these points deserve longer treatments elsewhere.

2. Corporations, markets and regulation

This section situates the CSA in the larger literature on corporate governance, corporate regulation, and corporate social responsibility. We present a stylized version of the trajectory of developments in those fields. These developments share a common assumption that companies are failing to create public value. We understand ‘public value’ to include what economists standardly understand as social welfare or efficiency, but also, beyond this, ethical concerns, such as social justice and sustainability (Bennett & Claassen, Citation2022b). We do not define public value precisely in this paper because its definition is itself constantly (re-)formulated in the fields of corporate governance, regulation and corporate social responsibility that we draw on (ultimately, we will argue that it should be defined democratically). In this context, we present the idea of the CSA as a desirable extension of the latest developments in these fields.

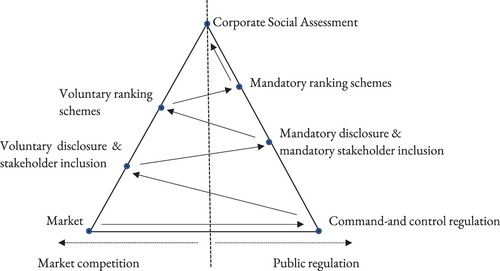

The trajectory is sketched along the lines of the pyramid in . The left-hand side represents market-based developments. They derive their effectiveness from delivering advantages in the competitive setting of the market. The right-hand side represents developments which are based on mandatory state regulation, hence coercive for those subject to them, and democratically legitimated to the extent that states are democratically organized.

The trajectory starts with market competition. If markets work well, they realize a variety of benefits. Well-functioning markets optimize the use of scarce resources in society given the state of technology (allocative efficiency) and they incentivize the development of new technologies to make most out of these resources (dynamic efficiency). These benefits are due to the competitive nature of markets, which is at the heart of the price mechanism. Firms extend these benefits of the market into areas where hierarchical organizations can be more efficient than decentralized contracting (Coase, Citation1937; Singer, Citation2018b). This serves the public good, in terms of maximizing social wealth.

As we know, however, markets may fail. There are a number of potential sources of market inefficiency (e.g. information asymmetries, externalities, imperfect competition) that reverse the social gains of market competition. Handbooks of regulation describe market failures as standard reasons for regulation, adding to these the above-mentioned broader concerns about social justice and sustainability (Baldwin et al., Citation2012; Feintuck, Citation2010). Health and safety, environmental, employment and other types of regulation are meant to protect stakeholders whose interests are put under pressure by market competition. Well-designed and effective regulation provides real incentives to businesses to take these interests into account. If it works well, the mandatory nature of regulation strongly pressures corporations to conform, and creates a level playing field between companies. Regulation in the post-war period often took a command-and-control form, with a multiplicity of discrete rules promulgated in advance. This has many advantages, including transparency, predictability and legal certainty.

The combination of markets and regulation could be called the ‘Friedman synthesis’, after Milton Friedman’s famous statement that businesses’ only social responsibility is to make profits for their shareholders (Friedman, Citation1970). He assumed that regulation would protect public interests. Thus, a neat division of labour between companies and state-regulators would ensue.

The rise of the field of corporate social responsibility (CSR) reflects a perceived failure of this market-regulation synthesis – the limits of command-and-control regulation in resolving market failures (Heath, Citation2014) and ‘justice failures’ (Singer, Citation2018a). A first source of failure is that regulation can be deliberately gamed. Businesses are sometimes very well acquainted with how to follow the letter of law while subverting the intentions behind it. Even worse, regulations themselves may be biased because of lobbying and/or softer forms of ‘capture’ of politicians and administrators during the processes of drafting, enacting, implementing and enforcing regulation (Néron, Citation2016; Stark, Citation2010). Second, some public concerns may not yet have been taken up by rule-makers, since new laws and rules often take a long time to implement, which is especially problematic in fast-changing, dynamic industries. This time-lag is a serious handicap. The protection of public values can fall between the cracks until new regulation catches with the new developments in business, by which time the industry may have moved on again. Third, globalization has led to a global regulatory gap, where multinationals operate across borders but public governance is weak in developing countries and absent at the global scale (Fuchs, Citation2007; Vogel, Citation2010).

Partly as a response to these limits to regulation, CSR has been gaining popularity in the last decades. We understand CSR here as a voluntary undertaking, initiated by businesses themselves, sometimes supported by voluntary pressure from consumers (‘ethical consumerism’) and investors (‘socially responsible investing’). The advantage of this approach is its flexibility. Unlike traditional regulation, voluntary approaches are crafted ‘on the ground’ of business life. They can take new, unforeseen circumstances into account, and incorporate these across borders in the operations of the business. As a part of our stylized trajectory, we want to highlight two elements in this CSR movement. The first is voluntary disclosure. As CSR matured, it became more and more customary for investors and consumers to demand transparency about a firm’s concrete CSR results. This led to the development of practices of social/sustainable reporting, accounting and auditing (Barker & Mayer, Citation2017; Gray et al., Citation2014; Gray & Herremans, Citation2012; Rahom & Idowu, Citation2015). The second element is voluntary stakeholder inclusion. Realizing that CSR policies were about treating certain stakeholder groups well, companies realized that conversations with stakeholders would lead to better and more legitimate policies. The field of stakeholder theory was developed to address the importance of maintaining good relations with stakeholders (Donaldson & Preston, Citation1995; Freeman et al., Citation2010).

Nonetheless, CSR has two important limits of its own. First, given CSR’s voluntary nature, we cannot assume that a corporation’s profit will be best served by focusing on public value. In some cases, CSR will be at least potentially profitable for a company because some customers and investors will be prepared to pay more for greater social responsibility. However, the ‘market for virtue’ (Vogel, Citation2005) is limited, and this limits how far CSR can really incentivize good corporate behavior. Doing the right thing shouldn’t just be a niche marketing strategy that can only work for a few brands catering to the minority of consumers and investors who are willing to put their money where their mouths are. We concur with Cynthia Williams (Citation2018, p. 668), who in her review of the impact of CSR states that ‘the “business case” may never be strong enough to overcome the economic disincentives to invest in higher labour costs or expensive pollution abatement without a supportive regulatory framework that creates a level playing field for competition’.

Second, CSR initiatives are not democratically legitimated. Even with the best intentions, company views of public value may not match with those of the broader public. Decisions about which ethical goals a company should prioritize involve tricky moral trade-offs. For example, suppose a pharmaceutical company is reaping massive profits from their patents on an important vaccine. Even if we agreed that these profits were unjustifiable, the question of what response the company should prioritize is still wide open. Should they channel those profits directly back into researching more life-saving drugs? Put more of their intellectual property into the public domain? Provide discounted or free vaccines to humanitarian organizations and poorer countries? Leaving ethical decisions which affect societies at large to the discretion of shareholder-appointed boards of directors seems at odds with democratic commitments (Bennett, Citation2022; Bennett & Claassen, Citation2022a).

In response to these and other limits, we are now at the point where key CSR achievements are being turned into legal obligations. We see a ‘regulatory hardening’ of CSR (Berger-Walliser & Scott, Citation2018) on multiple fronts. Disclosure is moving from voluntary to mandatory. In the EU, a new Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive went into force on January 5, 2023, strengthening the requirement of an earlier non-financial reporting directive.Footnote1 The European Commission has proposed a Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), which is scheduled for adoption later in 2023. It contains mandatory due diligence provisions on environmental and human rights matters for corporations down their supply chain.Footnote2 Much less is being done to make stakeholder inclusion in corporate governance mandatory. There has been no lack of academics pleading for changes in corporate governance which would give a stronger voice to stakeholders (Davis, Citation2021; Strine, Citation2020). But only Germany and Austria have significant co-determination systems giving workers control rights alongside shareholders. These have been in place for half a century now. Resistance to mandatory stakeholder inclusion has so far prevented any moves towards corporate democratization.

Meanwhile, the market also moves on. The wild diversity in frameworks of reporting and accounting makes CSR performance hard to compare between firms. Hence their use is limited. The next move, having made CSR transparent, is to make performance commensurable. This means grading and ranking. Commercial rankings are provided by ESG rating agencies, which score companies on their performance in the areas of ‘Environmental’, ‘Social’ and ‘Governance’ (Pollman, Citation2022). Third-party non-profit initiatives have taken hold as well. In section 4, we will zoom in on the case of the Access to Medicine Index, which has by now been followed up by a range of other industry-specific indices, such as the Access to Nutrition Index, Access to Seeds Index, the Responsible Mining Index and others (Quak et al., Citation2019, p. 173).

These movements are still unfolding, but we attempt to look ahead, proposing what we take to be a normatively desirable future trajectory that builds on developments in the field so far. In particular, there are two aspects of the current system of voluntary rankings of companies’ public value performance that we believe should be pushed further. First, voluntary rankings should become mandatory as well. This would be a third iteration from the ‘market’ to the ‘public’ side in our stylized trajectory (see ). This would clean up the current unsatisfactory co-existence of multiple, diverging ESG ratings for the same companies (see section 4 hereafter). It would establish publicly sponsored and well-established bodies making indices which could be aggregated over all issue-areas. This forms one element of our CSA proposal (see the summary in the introduction, and the full proposal hereafter). But second, pushing the logic of current developments even further, once all companies are compared in a common framework of public value, a next market-based movement would be to turn this into a competition. This means introducing financial incentives for good performance in the ranking. After transparency and commensurability comes financialization. This is another element of our proposal: a CSA Fund.

In addition, we have also incorporated an enhanced democratic legitimation of the CSA, by proposing that a Citizen Assembly determines the goals to be achieved in each cycle of assessment. The reason for doing so lies in the fact that a ranking across companies and sectors cannot work with a selection of relevant stakeholders which would differ between companies. Many reform proposals in corporate governance that want to broaden the group of corporate constituencies beyond shareholders argue for the inclusion of workers (Ferreras, Citation2017; Greenfield, Citation2006; Hayden & Bodie, Citation2020). Others plea for empowering a broader range of stakeholders (Deakin, Citation2012; Scherer et al., Citation2012; E. Freeman & Evan, Citation1990). The CSA – given its range across the landscape of corporations as a whole – cannot just limit its composition to workers. Public value is a matter of interest for all citizens. The CSA can be an institutional nexus where society’s expectations of companies crystallize, providing legitimacy to corporate conduct that is in line with its demands (Claassen, Citation2023).

All in all, the CSA is a new proposal, but one which builds on current developments. Our goal is not to predict where this journey will go next, but to point out a promising way forward that connects to the path we have been travelling. We will now first outline the main elements of the proposal.Footnote3

3. The corporate social assessment in a Nutshell

This section describes six key elements of our proposal: (1) its scope, (2) the grading scheme, (3) the Citizens’ Assembly composing the scheme, (4) the assessment body, (5) the ranking of companies and (6) the financial incentives attached. To keep things simple we have presented only our preferred design choice for each of these elements. Still, we emphasize that we think the proposal is worth considering for those who object to particular design choices. The value of the proposal is not in any of the specifics, but in the broader idea that emerges when these elements are put together.

Scope. Assessing all corporations in a jurisdiction would be very costly and probably unnecessary given how public concerns about corporate conduct generally cluster around larger firms. We therefore limit the assessment to corporations above a certain threshold size. For example, the scheme might use the EU classification, which defines small and medium sized enterprises as those with fewer than 250 employees and either annual turnover less than 50 million euros and/or a balance sheet less than 43 million euros.Footnote4 Such enterprises would be excluded from the assessment, which would only apply to companies larger than this. We would not include non-profit corporations, which are sufficiently different to merit separate treatment.Footnote5

Grading scheme. The assessment body should be provided with a flexible but focused grading scheme for making their assessments. This would give them criteria to work with, but at the same time discretion to judge the company’s conduct in each category. The idea is comparable to assessments in a job competition. Organizations looking for a new person may list criteria in a public place when looking for new personnel: ‘excellent presentation skills’, ‘familiarity with software’, ‘knowledge of civil law’, ‘speaks French’, etc. The job of the assessment body is to match candidates to the criteria. There will be room for discussion (candidate X is knowledgeable with software A, candidate Y with software B); there is room for comparative assessments (how good is her French, compared to that of the other candidate), but the criteria are still indispensable in focusing the assessment. The scheme would specify certain categories (e.g. tax avoidance, environment, corruption, discrimination, labour practices, supply chain, etc.), and assign a weight to each. For example, out of a total of 100 points, fifteen points might be available for environmental conduct, eight points might be available for discrimination and diversity in the workforce, etc. The grading scheme might also provide examples to assist assessors in its interpretation.

Citizens’ Assembly. The grading scheme is decided at the start of each new four-year cycle by a Citizens’ Assembly convened for that purpose. Around 150 citizens would be randomly selected to attend (perhaps with stratified sampling to ensure a representative sample regarding salient demographic variables such as gender, age, geography and socio-economic status (OECD, Citation2020, p. 82)). Citizens would be paid to attend meetings for a period of several months during which they would consider witness evidence from a range of relevant stakeholders and experts. The grading scheme will then be publicly promulgated as the basis of assessment for the next four years. The introduction and role of the Citizen Assembly is our response to worries about the democratic legitimation of a CSA. This is the main theme of section 6, hereafter.

Assessment Body. Individual companies would be graded using this scheme by a permanent body of professional experts. This process would be organized as an ‘arms-length’ or ‘quasi-autonomous’ organization publicly funded but not directly reporting to the elected government. In this way, the assessment body would reflect the practices of both public regulatory agencies and of non-profit ESG indexes. Naturally, as in these cases, there would need to be stringent rules against corruption and conflicts of interests. Indeed, we would recommend even stronger rules than currently exist in the public sector to prevent any possibility of a ‘revolving door’ between employment at the assessment body and at the companies being assessed. At the start of each four-year cycle, the first task for the next incoming Assembly would be to conduct a review of the assessment body’s work in the previous cycle. This would help hold the assessment body to account and give it direction for how to do its work in the future. It would also give the Assembly insight into practical problems that arise in the course of making assessments, some of which might be addressed in the grading scheme for the next cycle.

Ranking. The goal of the assessments is to assign companies into ten tiers, from Tier 1 (excellent) to Tier 10 (very poor). The set-up is competitive: only 10% of all scrutinized corporations get tier 1 status, 10% get tier 2 status, etc. Competitive classification is comparable to systems of ‘grading on the curve’ in education. The number of places in each bracket is limited, and relative performance of corporations determines their bracket. This creates a zero-sum game. It requires a two-step process.Footnote6 First, assessors score the companies on (say) a 100-point scale. Second, once all companies have been graded, they can be ranked according to their initial grades. We then move down the ranking dividing the total population of companies into ten equally sized groups. Companies who make up the top 10 percent of the ranking go into Tier 1, companies making up the next 10 percent go into Tier 2, and so on. Ranking is a pervasive practice in social life. Is it warranted to stimulate companies in the way we envisage? This is the main topic which we discuss in greater detail in section 4 hereafter.

Financial consequences. All corporations must contribute a ‘CSA fee’ to the CSA Fund in advance of each cycle. After the assessments, subsidies will be paid out of the fund depending on how companies have performed in the assessment. For example: as a group, tier 1 companies might receive 19% of the fund; the tier 2 group of companies, 17%; and so on down to Tier 10 companies receiving just 1%. The exact formula will require fine-tuning.Footnote7 This implies that – along a sliding scale – the top half of the ranking will be net-recipients from the competition, while the bottom half will be net-contributors. Fees and subsidies are calculated as a percentage of annual turnover so that they reflect the same proportional burden/incentive for each company. The fund should not raise revenue for the state, but merely exists to pay out the CSA subsidies, and so should be emptied at each round. Overall, this fund creates a competition for public value. Is this feasible and desirable? We address this question in section 5 hereafter.

With this overview in place, let’s now move to in-depth discussion of three of the core features of our proposal: first, the commensuration of corporate conduct in a ranking; second, turning this into a competition; and third, the democratic legitimation of the process though a Citizens’ Assembly.

4. Regulatory rankings: the challenge of commensuration

It’s a cliché that we live in an ‘audit society’, saturated by performance measures, standards, benchmarks and indicators (Power, Citation1997). To navigate in a complex and uncertain world, there may well be no alternative for rankings (Esposito & Stark, Citation2019). The CSA is part of that movement, and this raises both practical and normative questions. In this section, we focus on two challenges: the scoring of companies and the weighing of criteria (a third challenge, the selection of the criteria, is the subject of section six). We will address these challenges for the CSA through the rankings literature in sociology and organization studies (for overview, see Ringel et al., Citation2021). A particularly instructive example in this literature comes from a recent study of the Access to Medicine Index (AtMI), which assesses twenty leading pharmaceutical companies’ performance with respect to making medicines available in less developed countries (Mehrpouya & Samiolo, Citation2016; Citation2019). Since this is a good example of a social issue that could be included in the CSA as well, the lessons learned in this case will be pertinent for our purpose.

The first challenge is that scoring companies requires comparing their performances. The key operation at stake is commensuration: the construction of common metrics which enable comparability between otherwise incomparable entities. This may generate resistance, when the underlying processes or activities are deemed ‘incommensurable’, since the reduction of qualitative information to a numerical score necessarily omits important information (Espeland & Stevens, Citation1998, p. 327). Here the CSA can take its inspiration from a range of sector-based initiatives of ‘regulatory rankings’, rankings that have a double aim: to provide information to stakeholders in the field, but also to change the behavior of the organizations being ranked, be they city branding (Kornberger & Carter, Citation2010), IT vendors (Pollock & D’Adderio, Citation2012) or social media (Scott & Orlikowski, Citation2012). Rankings are an exercise in market-making, in that through their measurements they aim to stimulate competition between the organizations ranked. As such, they are an example of the ‘reactivity’ of objects (persons) who are being measured (Espeland & Sauder, Citation2007), as well as of the ‘performative’ nature of markets in general (Callon, Citation2007).

The challenge is to understand how – if at all – commensuration can come about. The foundation running AtMI has built up experience over the last two decades in bringing out its bi-annual reports. Mehrpouya and Samiolo’s study reveals how the foundation’s analysts meticulously work to render their company scores commensurable. For some indicators, quantitative data are easily available, but for many, evidence must be assessed to plot the companies’ scores on a scale from 0 to 5. These assessments are not a matter of ‘mechanical objectivity’ but of ‘trained judgment’ (Mehrpouya & Samiolo, Citation2016, p. 16).

That commensuration is a process requiring trained judgment by analysts comes out particularly clearly in the fact that the Access to Medicine criteria themselves sometimes had to be refined or even re-designed to create meaningful differences between companies. If companies cluster around (say) score 2 on a 0 to 5 scale for some indicator, this does little to stimulate competition between them. Criteria were defined in such a way that, ideally, at least one company would score 0 and one company would score 5. These measures reflect that the comparison is a relative, not an absolute one, and that scoring for this index is an effort at market-making by creating interesting differences, a work the authors dub the ‘politics of variability.’ They give the example of the indicator ‘the company commits to make available for free the products in the countries where the clinical trials for those products were carried out’. At first, a level 5 score for this indicator was specified as follows: ‘the company commits to the Declaration of Helsinki for international drug trials.’ But since most companies had made that commitment already, this was later changed into: ‘Company has a specific, detailed approach to post-trial access (…) which assures access to patient benefits in a large variety of different circumstances.’ (Mehrpouya & Samiolo, Citation2016, pp. 23–24).

Rankings may well be greeted with hostility by their targets. In a classic study of rankings of US law firms, Espeland and Sauder showed how these rankings provoked different institutional and emotional reactions amongst the people working in the ranked organizations, including apathy, resistance and manipulation (Sauder & Espeland, Citation2009). Similarly, AtMI experienced strong resistance from industry at first, but the legitimacy of the index became more accepted over the course of several cycles of reports (Mehrpouya & Samiolo, Citation2016, p. 28). More worryingly, a ranking may be highly effective in setting up the wrong incentives. The metrics used may focus organizations to perform well on the ‘metrics’ at the expense of attention for (broader, less easily quantified) issues not captured by the metrics (or even with negative effects on these issues). The phenomenon has been described as ‘goals gone wild’ in the management literature (Ordóñez et al. Citation2009).Footnote8 Responding to this problem, the AtMI indicators are described as ‘empty frame to be filled by companies’ initiatives’ (Mehrpouya & Samiolo, Citation2016, p. 28). Such more open criteria invite less of this incentive problem, although it makes them harder to judge – a balance needs to be struck here.

The experience of the AtMI and similar initiatives show that reasoned judgments about company performance can be made. This never generates a completely objective assessment, since any process of commensuration is itself a social construction. But ‘trained judgment’ can do the job, as it does in higher education when professors rank students, in science committees where grant proposals are graded, in law courts when judges calibrate the length of a prison sentence by comparing sentences in previous cases, in jury sports where performances are ranked, and in countless other social contexts. Although a work requiring time, resources and skills, the scoring part is the least contentious part of the process, we would argue, compared to the weighing of criteria (and their selection, which we deal with in section six).

The second challenge, then, is to weigh the various indicators and criteria with respect to each other. For the AtMI, analysts choose and define ‘indicators’ and then combine them to create ‘criteria’: there are seven criteria in the Index, each of which is made up of varying numbers of indicators. However, the formula for weighing the criteria to come up with the overall grades is done by the ‘Expert Review Committee’, in which various stakeholders are represented, such as NGOs, a representative of the World Health Organization, and companies themselves. This is deemed to be a more ‘political deliberation’ organ compared to the technical role of the analysts. In the context of our CSA, this too would be a more political function. Therefore we propose to allocate this task to the Citizen Assembly which also selects the criteria (see section 6). The weighing of criteria should reflect the normative expectations that citizens have of companies. This distribution of labour is reminiscent of the politician/civil servant dividing line, a functional boundary between the more political and the more technocratic side of the process of governing.

The CSA’s task is more difficult than the AtMI’s. The AtMI only assesses twenty companies in one industry, with respect to one (albeit multidimensional) issue. The CSA aims to assess corporations across a much wider range of issues. A tricky issue is whether the criteria should be adjusted for companies in different industries. It might seem intuitively unfair to directly compare the environmental footprint of an oil company with a law firm. However, if some industries have systematic ethical failings, allowing those industries lower standards simply because of their poor performance in the past would defeat a large part of the purpose of the CSA. The real problem is not so much that some industries have lower ethical standards than others, but that some ethical issues are more salient (‘material’) in some industries than others.Footnote9 The carbon emissions of an accountancy firm, for example, are simply not that important in judging its ethical credentials, whereas issues of corruption and tax avoidance will loom far larger.

To deal with this problem, our preferred solution would be to define different weighing schemes for different sectors.Footnote10 Certain issues will be material in all sectors (e.g. corruption, or employment issues), other issues will be material in only some sectors, and to different extents. While accommodating this in sector-specific weighing schemes might be challenging at first for a single Assembly, over several iterations of the CSA cycle experience can accumulate as to how to do this well. The key thing is to incentivize companies to focus on those issues which it is actually most socially important for them to focus on, given the type of business they do. It is up to the Citizens’ Assembly to weight the different categories so that the aggregate grades reflect citizens’ considered judgments about priorities and trade-offs between different values or social problems.

The most widely used aggregate rankings of companies’ public value are the ESG rankings which have proliferated in the last 15 years, with different providers offering their rankings to investors. These rankings have been criticized for the poor correlation between them. The research suggests there are four main factors behind this divergence (Dimson et al., Citation2020; Kotsantonis & Serafeim, Citation2019). First, there are differences in metrics used. For example, one study found 20 different indicators for measuring ‘employment health and safety.’ (Kotsantonis & Serafeim, Citation2019, p. 51). The second factor is how the group of companies is benchmarked; this includes the problem of variability discussed above as well as the choice of peer group (universal or industry-based), also discussed above. The third factor is missing data due to a lack of mandatory disclosure, and the way ESG-providers impute a score when data for a company is missing. Some give a ‘0’ when companies fail to report data, others give a much higher score based on peer group data (Kotsantonis & Serafeim, Citation2019, pp. 54–56). Fourth is the different weights given to each of the three pillars of ‘E’, ‘S’ and ‘G’ in the ratings. These too vary considerably between ESG providers (Dimson et al., Citation2020, p. 78).Footnote11

A CSA would eliminate these sources of divergence. By definition, it would mandate companies to report the relevant data. But additional research suggests that with enhanced disclosure the divergences even increase (Christensen et al., Citation2022). Hence the design choices in the other three factors mentioned – and also highlighted in our discussion of the AtMI – are key. The CSA would ensure convergence by using one set of metrics, one benchmark methodology, and one set of weights. These design choices are not value-neutral, which is precisely why it is important they be democratically legitimated, as we will discuss further in section 6.

5. Competition for public value

A society-wide ranking of the most important companies would bring them into a competition with each other, a mandatory competition for public value creation with a financial pay-out. We will now reflect on this competitive character of the CSA, which – as explained in section 2 – we see as one of the two main innovations of the proposal, compared to the rankings established by private intermediaries such as the AtMI, which amount to a form of ‘private governance.’ We will reflect on possible factors which will influence the effectiveness of such a competition, as well as its overall desirability as a steering mechanism for the public good.

The CSA aims to set up desirable dynamics towards public value creation. In each new period, corporations who have received tier 2 status for their performance in the previous cycle will know that they have to create at least as much public value as corporations who scored tier 1 status. Corporations with current tier 1 status, knowing this, will have to improve themselves even further to remain ahead of these competitors. The assessment system, if it works well, sets into motion a ‘race to the top’ (Mehrpouya & Samiolo, Citation2016, p. 23, 25), a virtuous circle with corporations competing to achieve or maintain tier 1 status, with ever higher levels of public value creation as a result. In achieving such competitive effects, the CSA makes use of price signals, just like the market it is meant to correct. When corporations are embedded in market competition and subject to the CSA, they will have two sets of competitions to participate in simultaneously. When a course of action is profitable, but would be penalized by the CSA, then the CSA counterbalances the market’s effects. If the CSA’s effect would financially outweigh the market’s effect, then there now is a business case for not implementing the strategy. Corporations will have to find a way to balance their success in both arenas, both of which work on their bottom lines.

The question is: will this competition work as envisaged? The literature on rankings offers mixed evidence. In some cases, rankings seem to offer clear incentives with real effects. As Espeland & Sauder report in their study of US law schools: ‘nearly every admissions director interviewed reported that students’ decisions correlate with rankings: if a school rank declines, they lose students to school to which they had not lost them in the past and vice versa’ (Espeland & Sauder, Citation2007, p. 12). However, in other cases, the effects are less clear. A study on the AtMI’s global effects argues that the effect of the ranking is inconclusive: ‘the question remains to what extent it contributes to the improvement of public health around the globe’, noting that ‘even though various pharmaceutical companies are developing access programmes, they are also fiercely protecting their patents, thereby weakening developing countries’ abilities to provide good health care to their population’ (Quak et al., Citation2019, p. 199). Finally, a study of a ranking in the food waste industry concludes that the lowest-ranked companies displayed no interest in competing: ‘Ranks only trigger desire when the actors believe they can achieve a high-ranking position and that attaining such a position will benefit them. If these opportunities are not seen, they accept their position with indifference and turn instead to those competitions that promise better results’ (Arnold, Citation2021, p. 113). What to make of this?

An important distinction is between ‘direct’ and ‘indirect’ competition (Werron, Citation2014). Direct competition is over a scarce resource, such as two countries competing over a territory, or two athletes over a prize. Given the scarce nature of the resource, the competition generates an immediate incentive effect for the competitors. Indirection competition is for the attention, prestige and recognition of a constructed audience. Here the uptake is more complex, since it depends on whether the stances of the audience (their judgments about the reputation of the ranked competitors) will feed back into the competition. In the case of the ranking of US law schools, the main audience of the rankings is the prospective students, whose choice the rankings hope to facilitate. The rankings measure the quality of schools, i.e. how they treat their students. But these students’ choices are also the scarce resource that the schools happen to be competing for. There is an immediate effect from a student’s perception of a law school’s reputation, and their choice where to apply. The object of the ranking, the audience targeted, and the scarce resource all align. In the case of the AtMI, the perception of its audiences has a much less direct target. The audiences are diverse: companies, investors, governments, NGOs. These may have varying motives (not) to care about the ranking, and factor the ranking into their decisions. Most importantly, the targeted audiences do not include the objects of the ranking, i.e. the ‘patients, doctors, hospitals, and like in Index Countries’ whose ‘powerless gaze’ is deemed ‘irrelevant in organizing the competitive game’ (Samiolo & Mehrpouya, Citation2021).

This point has pertinence for the CSA as well. A CSA as described in section 3, but without the financial incentives, would induce reputation effects to the extent that consumers, investors and workers who wish to favour more ethical companies could use the tiers as a heuristic in assessing companies. These reputational effects could be enhanced by forcing companies to display their tier prominently in certain contexts, such as corporate documents, contracts and even advertisements. However, so far market-based reputation effects have not been effective in making companies pay the true social and ecological price for their activities. One reason for this can derived from the case of the AtMI: the stakeholders whose interests are being neglected often do not have the bargaining power to enforce internalization of their ‘externality’. (Other reasons for the failure of reputation effects can range from the opacity of public value performance to stakeholders’ unwillingness to put their money behind their moral convictions). In this context, providing financial incentives on the basis of CSA-outcomes opens up the prospect for companies to align their financial interests with enhanced public value performance.

Even if we may expect companies to be in principle interested in their financial performance, the extent to which they are may still depend on the size of the incentive. We would expect a CSA to need adjusting over time to optimize companies’ incentives to reach higher tiers. The strength of the incentives is a function both of the overall size of the fund and of how unequally the subsidy is allocated between tiers. The risk of setting the incentives too low is obvious: the system will have little impact on improving corporate conduct. The risks of setting the incentives too high are more subtle. Companies might become too focused on satisfying the CSA and insufficiently focused on actually providing valuable products to customers. Overly high rewards might lead those who do well initially to do better and better, while those who do poorly initially fall into a vicious spiral. Companies in higher tiers might use the subsidy to fund philanthropic activity to boost their standing in subsequent rounds. Conversely, companies in the bottom tiers might be pushed towards bankruptcy, and desperation might perversely make them more ruthlessly profit-oriented rather than more socially responsible. Optimizing the incentive strength is something that will become much easier over time after the system can be observed in operation. It may be wise to err on the side of caution to begin with, and then strengthen the incentives until corporations are responding as desired.

Finally, introducing financial incentives raises a broader question about whether this is the appropriate way to incentivize ethical behavior. This can be phrased as a moral critique, i.e. that companies should not care for environmental degradation, slave labour or any other public value issue because it pays, but simply because it is morally required. But it can also be phrased as a practical critique: that providing financial incentives is counterproductive becasue it would crowd out intrinsic motivation.

We are not convinced that the moral critique has much bite in this context. A comparison with debates over the ethical permissibility of carbon trading may help to show this. Sandel (Citation2005) argues that carbon markets are morally problematic because they commodify the intrinsic, non-monetary value of nature. Against this, Simon Caney and Cameron Hepburn argue – convincingly in our eyes – that carbon markets should be seen as a means to an end. The end (protecting the global atmosphere) may be intrinsically morally valuable, but this is compatible with using markets as a means to that end. In the same way, we protect ancient ruins by charging a price to visitors – the price doesn’t make cultural heritage less intrinsically valuable (Caney & Hepburn, Citation2011, p. 221).

As to the practical critique, the literature on the crowding out effect shows that intrinsic motivation can be displaced by introducing monetary incentives in certain contexts. However, the relevance of this literature here is not straightforward. First, the crowding out effect is only damaging when there is an important fund of intrinsic motivation to displace. Given that current funds of intrinsic motivation have not so far managed to improve current levels of environmental destruction and worker exploitation around the world, this may not be the case. Second, the literature shows the crowding out-effect works against the price effect, but doesn’t cancel it. In the end, it is a contextual empirical question which of the two effects is more sizeable. Finally, there can also be crowding-in effects: introducing monetary incentives can alert people to the value of a good or performance formerly undervalued (Frey, Citation2012). The CSA could bring alignment between many employees’ valuations of social and environmental performance, and the organizational pressures to realize corporate profits that provide the larger context for their work.

Ultimately, the CSA aims to break down the market/morality dichotomy now often associated with CSR. The diverse manifestations of public value could become an organizational purpose like any other, defensible both as a morally worthy pursuit and as something that creates financial value to the organization.

6. The citizens’ assembly

The third main feature of our proposal is the role of the Citizens’ Assembly. To recap, our proposal involves both a permanent professional assessment body and a Citizens’ Assembly convened every four years. The Assembly’s task is firstly to review the work of the assessment body in the previous cycle, and then to decide on the grading scheme for the next cycle. A Citizens’ Assembly is one version of what are often known as a ‘deliberative mini-publics’: ‘bodies comprised of ordinary citizens chosen through near random or stratified selection from a relevant constituency, and tasked with learning, deliberating, and issuing a judgement about a specific topic, issue or proposal’ (Warren & Gastil, Citation2015, p. 562). We begin by explaining the value we see in giving a Citizens’ Assembly this central role. We then tackle the question of why such an Assembly should be thought competent, especially on a relatively large open-ended issue like corporate conduct.

The Assembly’s function is to give democratic legitimacy to the CSA. More precisely, the Assembly provides two valuable democratic goods: better information and greater impartiality. These points can be seen through a contrast with a more traditional regulatory system.

Having an Assembly write the grading scheme allows the public to transmit their preferences about corporate conduct in a much more fine-grained way than can be achieved through electoral politics. Regulators ultimately derive their legitimacy from elected politicians who derive their legitimacy from voters, but very few voters are likely to have much knowledge or interest in the work of any particular regulatory body. Public preferences about corporate conduct are transmitted to regulators only in very broad brushstrokes. Politicians must optimize for electoral advantage against the background of an inattentive and uninformed citizenry. This can lead to policies that do not advance what citizens would see as the public interest on further reflection (Achen & Bartels, Citation2016). In response to their lack of information about citizen preferences, many government agencies employ a variety of processes for public consultation. In a sense, the Assembly takes this device to the next level by codifying it and making it harder to manipulate or ignore.

The grading scheme records citizens’ considered preferences about corporate conduct: what kind of conduct citizens find (un)acceptable and (crucially) how conduct in different areas should be prioritized and traded-off. However, the Assembly does not simply record pre-existing opinions but gives representatives relevant information about the subject and time to reflect on it. For this reason, deliberative mini-publics are sometimes said to have a counterfactual character, reflecting the enlightened version of public opinion were people to be better informed and more reflective (Fishkin, Citation2018).

A second aspect of legitimacy that the Assembly assists with is impartiality. As we discussed above in section 2, traditional models of regulation are vulnerable to problems of gaming and regulatory capture. The Assembly can help to mitigate these problems. Random selection upsets any patterns that might lead to regulatory capture, such as the ‘revolving door’ between regulators and their targets, or a similar socialization and demographic make-up on both sides (Guerrero, Citation2014). This was precisely why random selection was so heavily employed in pre-modern republics such as Venice or Athens, where elite capture was an existential threat (Vergara, Citation2020). The greater democratic legitimacy of the CSA in these two respects allows it to take a more flexible approach than traditional command-and-control regulation, which is constrained to a more-rule based approach because of its distance from democratic legitimation.

Many are doubtful that random citizens are competent to perform such an intellectually difficult task. However, even if we set aside purely theoretical arguments (e.g. Landemore, Citation2013) there is good empirical evidence for the epistemic capacities of deliberative mini-publics. One recent survey concludes that ‘mini-publics enact a form of inclusive deliberation that far surpasses the quality of political discourse of most other political institutions, be they legislatures and their committees or expert commissions or other forms of participatory governance’ (Smith & Setälä, Citation2018; see also Curato et al., Citation2017; Dryzek et al., Citation2019).

This evidence comes in various forms. James Fishkin and his collaborators have found that deliberation tends to shift participants’ opinions in informed and reasoned ways. For example, participants in a California mini-public evaluated a proposal for lengthening terms of office in the state legislature from two to four years. The proposal went from 33% approval at the start to 80% by the end of deliberation. Deliberators ‘became less concerned with the argument that increasing the terms would make the legislators “less responsive to their districts”’, and more persuaded by the argument that ‘increased state legislative terms will let them spend less time campaigning and fundraising and more time legislating’. The deliberators moved away from a simplistic narrative and towards the consensus view of political scientists that short term lengths reduce rather than enhance responsiveness (Fishkin, Citation2018, p. 144). Other studies have similarly found that deliberating participants are able to see through attempts by elites to frame issues in misleading ways (Niemeyer, Citation2011). An alternative methodology has been developed to operationalize measures of ‘discourse quality’ in a purely formal way that is amenable to quantitative analysis; deliberative mini-publics have performed well on such measures (Bächtiger & Parkinson, Citation2019). Of course, these good outcomes rely on a deliberative mini-public being set up in the right way; a consensus on best practice has emerged which is summed up in a recent (Citation2020) OECD report.

Although many experiments in deliberative mini-publics have now been carried out, most of them do not feature the kind of decision-making power or the wide-ranging topic of discussion that the envisioned CSA Assembly does. The case that comes closest is probably the French Citizens’ Convention for Climate, initiated in 2019 in response to the yellow vest protest movement. Most of the Convention’s proposals were included in a 2021 act of parliament, although (contrary to the Prime Minister’s prior promise), many were watered down. Researchers attending the Convention noted its professionalism, arguing the Convention was able to implement a model of ‘experts on tap, not on top’: making extensive use of relevant expertise while carefully guarding their own autonomy (Landemore, Citation2020, p. 192). The Convention is similar to the proposed CSA Assembly in two ways. First, the Convention was not merely advisory and did not merely evaluate an existing proposal, but was empowered to draft a new set of provisions. Second, climate change, like corporate conduct, is a very wide wide-ranging topic (the Convention broke down into committees on Food and Agriculture, Employment and Industry, Transportation, and Lifestyle and Consumption). Despite the French government’s backsliding about implementing the provisions, the Convention’s success demonstrates the viability of using an Assembly for the kind of role it is put to in the CSA.

Other bodies such as the 2004 British Columbia Citizens Assembly on Electoral Reform, the 2018–2019 Irish Citizens’ Assembly (on several topics) and the 2020 UK Climate Assembly were not as empowered or wide-ranging as the French Convention. However, they share two common themes. First, the assemblies generally seem to have featured high-quality deliberation and produced high-quality outputs. Second, assemblies have experienced the greatest political success on topics (abortion, electoral reform, climate change,) where mainstream political parties were reluctant to take stances on or were seen as illegitimate or failing. In this respect, corporate conduct seems a relatively good fit, since it is also a topic on which the political system is often seen to be failing and on which politicians are reluctant to take strong stances.

To buttress our case for the Assembly’s competence it may help to highlight how we would expect the broader civil society to respond. Most of the time in deliberative mini-publics is spent considering evidence, and this phase of the process is where most opinion changes among participants take place (Goodin & Niemeyer, Citation2003; Thompson et al., Citation2021). Hence presenting a balanced diet of evidence representing a diversity of credible viewpoints has been a crucial ingredient of successful deliberative mini-publics. This has usually involved giving the major stakeholders on the topic a chance to make submissions to or witness before the mini-public. For the CSA we would expect to see industry associations, unions and pressure groups taking a prominent role. Recent decades have already seen a significant increase in campaigning and lobbying activities seeking to influence corporate decisions rather than governments (Crouch, Citation2011; Vogel, Citation2010). The CSA would provide a centralized focus for debates about corporate conduct which are currently often diffuse and fragmented. These debates in the broader public sphere and the testimony of civil society organizations would offload a lot of important epistemic work for the Assembly. Surfacing issues of concern, identifying central disagreements and even proposing text for the grading scheme would all happen in the stakeholder submissions at least as much as in the Assembly itself. This lessens the epistemic burden on the Assembly members, who are not required to be creative or to have subject-specific expertise, but instead come to a judgement on the basis of the testimony they have received.

Because extant deliberative mini-publics have been one-off events, they do not tell us how the public sphere would develop in response to a regular Citizens’ Assembly. However, we can look to parallels with other democratic institutions. The participatory budgeting process of Porto Alegre, Brazil, is a quite different kind of democratic experiment. This process was conceived as a way for citizens to directly participate in government, with city budgeting occurring in meetings open to all citizens. Baiocchi’s (Citation2005) research shows this process stimulated a notable thickening of civil society, with secondary associations growing to take an important role in formulating proposals and organizing participation in the process. More familiarly, a similar process of cognitive offloading takes place in any elected legislature. Elected representatives rely heavily on the epistemic labour of a dense network of think tanks and pressure groups, and we would expect something similar to occur with the CSA Assembly.

So far little work has been done on deliberative mini-publics in relation to corporations, probably because mini-publics have focused on public policy questions and CSR is often not considered in that category. Pek et al. (Citation2023) propose using mini-publics within multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) (the classic example of which is the Forest Stewardship Council) to increase the representation of marginalized views and balance dominant corporate voices within an MSI. They propose selecting participants from members of the MSI and ‘all otherwise affected actors’ (Citation2023, pp. 120–122). However, achieving the desired balance of representation requires a lot of discretion in defining the population and weighting the sampling of the different constituencies within it. This negates a lot of the point of random selection: that it is simpler, less contentious, and harder to corrupt or bias than any process involving human judgement. In contrast, the CSA uses a deliberative mini-public not as part of a politics of interests (stakeholders negotiating fair terms of co-operation) but rather a politics of judgement (impartial citizens deliberating on what is in the common good). This, it seems to us, is the only way diffuse, unarticulated and non-human interests can be served on equal terms with the interests of well-organized stakeholders. Sampling equally from the whole population allows one to leave questions of justice up to the Assembly itself, rather than implicitly presuming a conception of justice through the weights attached to different stakeholder constituencies.

7. Conclusion

This article has proposed an innovative approach to keeping business corporations accountable to the public good. A randomly selected Citizens’ Assembly will write criteria for how much weight should be given to different aspects of good corporate conduct. Companies will be graded using this scheme and then ranked based on their grades. Highly ranked companies will be subsidized at the expense of lower ranked companies.

We showed how this proposal can resolve difficulties encountered in the dialectic of regulation and CSR. Regulatory systems are often inflexible, rules are gamed and regulators can be politically compromised. CSR allows for greater flexibility, but its ultimately voluntary nature allows many companies to free ride and makes it hard for ethical firms to be competitive outside niche markets. ESG rating and ranking schemes attempt to improve the treacherous epistemic landscape of CSR, but their diversity and divergence create further uncertainty. Moreover, the field of CSR lacks democratic input in defining what public value means. The CSA attempts to marry the entrepreneurial flexibility of CSR and the market-making competitiveness of ESG ranking schemes with the mandatory financial incentives only the state can provide. Moreover, it democratically legitimates the process using a Citizens’ Assembly.

Along the way, we have responded to what we take to be the most serious objections to our proposal, concerning the possibility of commensuration, the prospects for creating competition for public value and the competence of ordinary citizens. Before concluding we want to briefly mention three more. In each case, these are just initial suggestions that require more work in the future.

First is the important question of how the CSA should treat multinational corporations, since these are precisely the companies that tend to attract the most ethical opprobrium. Ideally, the assessment should be implemented at both supranational and national levels, with the supranational level being global or regional (e.g. European Union). This would exempt companies that meet a global size threshold from undergoing national assessments in every jurisdiction. However, due to practicality and political feasibility, it is more likely that the assessment will initially be implemented at the national or regional level. In this absence of a global system, jurisdictions face a dilemma of extraterritoriality. Limiting the assessment to a national jurisdiction would exempt parent companies from responsibility for their subsidiaries’ foreign activities, while a fully extraterritorial approach would disregard other countries’ self-determination. We would recommend a middle way which gives some consideration to companies conduct abroad in the assessment, perhaps focusing on human rights violations (Ruggie, Citation2013). Ultimately, the decision on how to balance extraterritoriality should be made democratically by the Assembly, and stakeholders from other countries could be invited to provide testimony to help the Assembly decide.

Second are concerns about political feasibility. On some level, we want to defend the legitimacy of advancing proposals on their merits without having to immediately consider their implications in the current political climate. Nonetheless, we think that the CSA is not such a heavy lift as it may initially appear. One should not assume the CSA will be opposed by business interests simply because it attempts to make businesses accountable to the public good. Since the CSA is revenue-neutral there will be a firm that stands to gain financially for every firm that stands to lose. Moreover, many people in business want to do the right thing but are held back by the incentive structures they operate within (Heath, Citation2018). Many already want their companies to be more considerate of public purposes, and the CSA is a way of making public purpose pay.

A related fear is that the CSA would not be viable in the long term because taking action against corporate malpractice would prompt companies to flee to more lenient jurisdictions (Ciepley, Citation2019). Our reading of the evidence suggests that such a flight of capital is unlikely, although beneficiaries of the status quo will naturally wish us to believe the threat is real (Bell & Hindmoor, Citation2014; Mooij & Ederveen, Citation2008) Moreover, if the CSA was taken up by a jurisdiction on the scale of the EU or the USA (and became a pre-requisite for trading in these markets), most companies would find the offer very difficult to refuse. In any case, this worry is not specific to the CSA proposal: it posits a broader problem for any kind of social democratic policy that might not advance the interests of the investor class.

Finally, one might worry that the proposal is simply too radical. Sensible policy-making should proceed gradually and respect the wisdom embedded in existing institutions. However, as we argued ins section 2, the CSA can actually be seen as a culmination of existing tendencies in the field of regulation, CSR and ESG ratings. Moreover, as the CSA could itself be implemented in a gradual way, starting out without any financial commitments and then sharpening the financial incentives over time as participants learn how to make the process work best. We expect an iterative process in which the grading scheme produced by the first Assembly will be a starting point that gets refined over time.

Many particulars remain to be fleshed out. If nothing else, we hope to provoke creative thinking about the kinds of tools democratic societies can employ to better discipline corporations to serve the public good.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the following people for their written comments on earlier drafts: Jonathan Benson, Barbara Bziuk, Thomas Ferretti, Dorothea Gädeke, Anna Gerbrandy, Fergus Green, Roy Heesakkers, Maurits de Jongh, Chi Kwok, Tadhg O Laoghaire, Hanno Sauer, Philipp Stehr, Tully Rector, Dick Timmer, Jeroen Veldman. We also thank various audiences for giving feedback, especially David Ciepley, Kees Cools, Hanoch Dagan, Roberto Frega, Nina van Heeswijk, Constantijn van Aartsen, Marco Meyer, Valerii Saenko, and others. A special thanks goes to the reviewers of this journal, whose incisive comments have considerably improved the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Michael Bennett

Michael Bennett is a lecturer in philosophy at Nottingham Trent University. He works in the interdisciplinary tradition of politics, philosophy and economics, and his research focuses on the relationship between capitalism and democracy. He has published on topics including corporate governance, business ethics, campaign finance and epistemic democracy.

Rutger Claassen

Rutger Claassen is professor of Political Philosophy and Economic Ethics, at the Department of Philosophy & Religious Studies, of Utrecht University. He has worked on various topics in political philosophy, such as theories of autonomy and liberalism, the capability approach to social justice, property theory, and the role of corporations. He is the Principal Investigator of the ERC-sponsored project Business Corporations as Political Actors (2020-2025).

Notes

3 The CSA bears some similarities with Thomas Pogge’s plan for creating a ‘Health Impact Fund’, a competition for public funds for health care improvements (Hollis & Pogge, Citation2008). After completing this article, Christian Felber’s (Felber, Citation2019) book was brought to our attention, which also has some similarities. Felber proposes companies create ‘Common Good Balance Sheets’ (p. 24) and attach financial consequences (p. 33). But his proposal does not create a separate Fund, but a regular (annual?) audit (p. 32), because it doesn’t rank companies between each other. It also doesn’t use citizen assemblies.

5 This follows standard practice in which non-profit organizations and for-profit corporations are usually subject to significantly different regulations. Of course, if the CSA is seen to work well for for-profit corporations something similar might be worthwhile for the non-profit sector, but we do not tackle this question here.

6 The competitive scheme needs an ordinal ranking of all companies in the jurisdiction. However, it is not humanly possible for a single person to directly rank every company in relation to all other companies. Something like the 100-point scale is therefore needed to provide a means of comparison for aggregating the judgments of various assessors into a single ranking.

7 Minimally, adjustments will be needed to account for uneven distributions of company sizes (turnovers) through the tiers.

8 See also the discussion of performance targets in (Ellemers and de Gilder Citation2022, 129–33).

9 Materiality is a concept from sustainability accounting denoting the relevance of an issue. It can refer to the impact of a sustainability issue on financial performance (single materiality) or – also - to the impact of the company performance on the sustainability issue (double materiality). The latter is what is meant here.

10 This is one way of dealing with the materiality issue. Alternatively, one reviewer suggested establishing different competitions for different issues (each of which apply across all companies). Thus one would have separate CSA’s for (say) environmental issues, human rights issues, etc.

11 A quantitative study of the importance of three factors (choices in scope, measurement and weights) in accounting for divergence, is (Berg et al., Citation2022). On the socially constructed origins of the divergences see (Eccles & Stroehle, Citation2018).

References

- Achen, C. H., & Bartels, L. M. (2016). Democracy for realists: Why elections Do Not produce responsive government. Princeton University Press.

- Arnold, N. (2021). Avoiding competition: The effects of rankings in the food waste field. In Competition: What It Is and Why It happens (pp. 112–130). https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780192898012.003.0007.

- Baiocchi, G. (2005). Militants and citizens: The politics of participatory democracy in porto alegre. Stanford University Press.

- Baldwin, R., Cave, M., & Lodge, M. (2012). Understanding regulation. Theory, strategy, and practice (2nd ed). Oxford University Press.

- Barker, R., & Mayer, C. (2017). “How should a ‘Sustainable corporation’ Account for natural capital?” Said Business School Research Papers, no. 2017–15.

- Bächtiger, A., & Parkinson, J. (2019). Mapping and measuring deliberation: Towards a New deliberative quality. Oxford University Press.

- Bell, S., & Hindmoor, A. (2014). The structural power of business and the power of ideas: The strange case of the Australian mining Tax. New Political Economy, 19(3), 470–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2013.796452

- Bennett, M. (2022). Managerial discretion, market failure and democracy. Journal of Business Ethics, 185(1), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05152-8

- Bennett, M., & Claassen, R. (2022a). Taming the corporate leviathan. How to properly politicize corporate purpose. In M. Bennett, H. Brouwer, & R. Claassen (Eds.), Wealth and power: Philosophical perspectives (pp. 145–165). Routledge.

- Bennett, M., & Claassen, R. (2022b). The corporate power trilemma. Journal of Politics, 84(4), 2094–2106. https://doi.org/10.1086/717851

- Berg, F., Kölbel, J., & Rigobon, R. (2022). Aggregate confusion: The divergence of ESG ratings. Review of Finance, 1315–1344. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfac033

- Berger-Walliser, G., & Scott, I. (2018). Redefining corporate social responsibility in an Era of globalization and regulatory hardening. American Business Law Journal, https://doi.org/10.1111/ablj.12119

- “Business Roundtable Redefines the Purpose of a Corporation to Promote ‘An Economy That Serves All Americans.’”. (2019). August 19, 2019. https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans.

- Callon, M. (2007). What does It mean To Say that economics Is performative? In D. MacKenzie, F. Muniesa, & L. Siu (Eds.), Do economists make markets? On the performativity of economics (pp. 311–357). Princeton University Press.

- Caney, S., & Hepburn, C. (2011). Carbon trading: Unethical, unjust and ineffective? Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplement, 69, 201–234. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1358246111000282

- Center for Responsive Politics. 2016. Top individual contributors: all federal contributions. OpenSecrets. https://www.opensecrets.org/overview/topindivs.php?cycle=2016&view=fc.

- Christensen, D. M., Serafeim, G., & Sikochi, A. (2022). Why is corporate virtue in the Eye of The beholder? The case of ESG ratings. Accounting Review, 97, https://doi.org/10.2308/TAR-2019-0506

- Ciepley, D. (2019). Can corporations be held to the public interest, or even to the Law? Journal of Business Ethics, 154(4), 1003–1018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3894-2

- Claassen, R. (2023). Wealth creation without domination. A fiduciary theory of corporate power. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 26(7), https://doi.org/10.1080/13698230.2022.2113224

- Coase, R. H. (1937). The nature of the firm. Economica, 4(16), 386–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0335.1937.tb00002.x

- Crouch, C. (2011). The strange Non-death of Neo-liberalism. Polity Press.

- Curato, N., Dryzek, J. S., Ercan, S. A., Hendriks, C. M., & Niemeyer, S. (2017). Twelve Key findings in deliberative democracy research. Daedalus, 146(3), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1162/DAED_a_00444

- Davis, G. (2021). Corporate purpose needs democracy. Journal of Management Studies, 58(3), 902–913. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12659

- Deakin, S. (2012). The corporation as commons: Rethinking property rights, governance and sustainability in the business enterprise. Queen’s Law Journal, 37(2), 339–381.

- Dimson, E., Marsh, P., & Staunton, M. (2020). Divergent ESG ratings. Journal of Portfolio Management, 47(1), https://doi.org/10.3905/JPM.2020.1.175

- Donaldson, T., & Preston, L. E. (1995). The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. The Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 65–91. https://doi.org/10.2307/258887

- Dryzek, J. S., Bächtiger, A., Chambers, S., Cohen, J., Druckman, J. N., Felicetti, A., & Fishkin, J. S. (2019). The crisis of democracy and the science of deliberation. Science, 363(6432), 1144–1146. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw2694

- Eccles, R. G., & Stroehle, J. (2018). Exploring social origins in the construction of ESG measures. SSRN Electronic Journal, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3212685

- Edgecliffe-Johnson, A. (2019). Abigail Disney Criticises Chief's ‘Insane’ $65.7m Pay. April 22, 2019. https://www.ft.com/content/b1c68f4c-651a-11e9-9adc-98bf1d35a056.

- Ellemers, N., & De Gilder, D. (2022). The moral organization. Key issues, analyses, and solutions. Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Espeland, W. N., & Sauder, M. (2007). Rankings and reactivity: How public measures recreate social worlds. American Journal of Sociology, 113(1), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1086/517897

- Espeland, W. N., & Stevens, M. L. (1998). Commensuration As a social process. Annual Review of Sociology, 24(1), 313–343. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.313

- Esposito, E., & Stark, D. (2019). What’s observed in a rating? Rankings as orientation in the face of uncertainty. Theory, Culture and Society, 36(4), https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276419826276

- Feintuck, M. (2010). Regulatory rationales beyond the economic: In search of the public interest. In R. Baldwin, M. Cave, & M. Lodge (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of regulation (pp. 39–63). Oxford University Press.

- Felber, C. (2019). Change everything. Creating an economiy for the common good. Zed Books.

- Ferreras, I. (2017). Firms as political entities. Saving democracy through economic bicameralism. Cambridge University Press.

- Fishkin, J. S. (2018). Democracy when the people Are thinking: Revitalizing our politics through public deliberation. Oxford University Press.

- Fitzgerald, A., Guevara, M. W., Bowers, S., Clerix, K., Díaz-Struck, E., Carvajal, R., Cabra, M., Knus-Galán, M., Obermayer, B., Bové, L., & Kleinnijenhuis, J. 2014. New leak reveals Luxembourg tax deals for Disney, Koch Brothers empire. International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, December 9, 2014. https://www.icij.org/investigations/luxembourg-leaks/new-leak-reveals-luxembourg-tax-deals-disney-koch-brothers-empire/.

- Freeman, E., & Evan, W. (1990). Corporate governance: A stakeholder interpretation. The Journal of Behavioral Economics, 19(4), 337–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-5720(90)90022-Y

- Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J., Wicks, A., Parmar, B., & De Colle, S. (2010). Stakeholder theory. The state of the Art. Cambridge University Press.

- Frey, B. (2012). Crowding Out and crowding In of intrinsic preferences. In E. Brousseau, T. Dedeurwaerdere, & B. Siebenhuner (Eds.), Reflexive governance for global public goods (pp. 75–83). Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Friedman, M. (1970). “The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.” The New York Times Magazine.

- Fuchs, D. (2007). Business power in global governance. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Goodin, R. E., & Niemeyer, S. J. (2003). When does deliberation begin? Internal reflection versus public discussion in deliberative democracy. Political Studies, 51(4), 627–649. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0032-3217.2003.00450.x

- Gray, R., Brennan, A., & Malpas, J. (2014). New accounts: Towards a reframing of social accounting. Accounting Forum, 38(4), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2013.10.005

- Gray, R., & Herremans, I. (2012). Sustainability and social responsibility reporting and the emergence of the external social audits: The struggle for accountability? In The Oxford handbook of business and the natural environment (pp. 405–424). https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199584451.003.0022

- Greenfield, K. (2006). The failure of corporate Law. The University of Chicago Press.

- Guerrero, A. A. (2014). Against elections: The lottocratic alternative. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 42(2), 135–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/papa.12029