ABSTRACT

Dolia were the largest type of pottery in the ancient world, capable of holding hundreds to as much as three thousand liters. Their shape and size facilitated wine fermentation, and also made them the most expensive and difficult type of pottery to produce. This paper discusses the production of dolia to explore the specialized skills, which consisted of both free and enslaved labor, necessary for the craft. Dolia were also produced alongside brick and tile products in workshops that supplied the building industry of Rome. Craftsmen trained to make dolia acquired considerable skills and usually advanced in the workshop. As a result, a type of professional identity developed, one that both reified and defied conventions since some workers were enslaved and/or manumitted. Finally, this paper briefly discusses the enslaved potter David Drake from nineteenth-century South Carolina to consider the limits of our knowledge about skilled and enslaved craftsmen.

Craft, professions, identity, and status

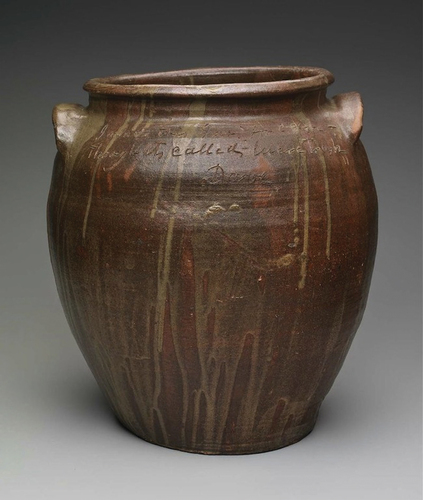

Over the last few years, numerous museums across the United States have been vying to collect large, utilitarian pots by the nineteenth-century enslaved African American potter David Drake, also known as Dave the Potter and, more disparagingly, Dave the Slave, paying upwards of $1.56 million for a single vessel (Kindy Citation2023). This recent surge of interest in David Drake’s wares culminated in a 2022 exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, ‘Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina’, demonstrating how David Drake’s pottery could provide a window into the brutal reality of a renowned potter (Chaney Citation2018; Koverman Citation1998; Spinozzi Citation2022). David Drake was known for his skill in making large storage jars (c. 25 to 40 gallons, or 90–150 liters) that were used to preserve different foods such as salted meats (). In fact, scholars have noted that the height of this industry, evidenced by an enormous 105-foot kiln in Edgefield, South Carolina, coincided with the rise of plantations, suggesting that these large storage vessels fostered the zenith of southern plantation economies. Considered some of the largest storage vessels of the time in the United States and often signed by David Drake himself, his work gives a glimpse into a talented potter who happened to be not only literate (which was forbidden then by the South Carolina Negro Act of 1740), but also poetic.

Figure 1. David Drake, 1857, made for Lewis J. Miles Pottery, large alkaline glazed stoneware vessel, with couplet ‘I made this jar for cash/though it is called lucre trash’. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. 1997.10. Harriet Otis Cruft Fund and Otis Norcross Fund. Photograph by Garth Clark.

Cobbling together different anecdotes, datable signed pots, and other evidence, scholars have been able to reconstruct traces of his life. He was likely separated from his family at an early age, never to see them again. Even the high value of his storage vessels was not enough to keep his family together; after his enslaver Harvey Drake died, Harvey’s sister sold and sent off David’s family to Louisiana. David himself had passed through the hands of several enslavers and at least five workshops before he was finally freed in 1863 under the Emancipation Proclamation and took the surname Drake from his former enslaver. At some point in his life, one of his legs was amputated, perhaps from an accident on the railroad or at work. The most likely explanation, however, was that it had to be amputated after his enslaver beat him severely as punishment for signing his works. Despite his talent and skills, David Drake faced grueling challenges and difficulties his entire life. His story cautions against conflating workshop hierarchy and craft talent with social status (especially between free and enslaved labor), agency, and quality of life.

Nearly two thousand years before David Drake’s time, highly skilled potters made Roman ceramic jars known as dolia, the largest type of pottery in the ancient Mediterranean, under demanding conditions ( and ). Because dolia could hold hundreds to as much as three thousand liters of valuable foods such as wine and olive oil, they were the most expensive type of pottery – costing 2,500 times more than common pottery and more than a month’s worth of wages for most manual laborers. They were also difficult to produce (Diocletian’s Price Edict 15.97; Cheung Citation2021, Citation2024; Cheung and Tibbott Citation2020; Peña Citation2007). Legally considered architectural elements due to their fixed nature, dolia were produced alongside bricks, tiles, and other heavy terracotta objects in the same workshops that supplied the building industry, known as opus doliare workshops (Ulp. Dig. 33.6.3; Steinby Citation1975, Citation1987). These workshops were particularly abundant around the city of Rome and its port city, Ostia.

Figure 2. Dolia at Ostia Antica. Photograph by AlMare. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ostia_Antica_Dolia.jpg

Figure 3. Gina Tibbott with a mid-sized dolium at the House of Stabianus (I.22) in Pompeii. Courtesy of the Ministry of Culture—Archaeological Park of Pompeii. Reproduction or duplication by any means is forbidden.

Although less poetic than David Drake’s inscriptions, dolia do preserve stamps that provide a wealth of information. The brick and dolium stamps of second-century opus doliare workshops reveal not only how the workshops combined the production of different objects, but also the organization of labor and roles and status of different craftsmen. Opus doliare stamps, in general, seem to have been used for both advertising to potential buyers and for internal purposes, i.e. bookkeeping. Brick stamps became standardized, featuring information about the figlinae, dominus, and officinator. Figlinae were ‘clay lands’ and referred to territorial districts owned or managed by the domini, ‘landlords’. Officinatores were entrepreneurs who could move from brickyard to brickyard and rent from different landlords, and probably oversaw the production of bricks. Dolium stamps were somewhat different. Found on the rims and/or shoulders of c. 20% of dolia in Ostia and Rome, the stamps were generally short with the name of one person, usually in the genitive, who was most likely the owner of the workshop. Some of the dolia featured a second stamp with another name, usually in the nominative to denote the maker or officinator of the dolium. Furthermore, dolium stamps provide insights into the ways craftsmen could train and learn in the workshop, as well as their status as free, enslaved, or freed (). Both the archaeological and epigraphic evidence point to opus doliare workshops manufacturing multiple products and clustering around other workshops, which provided a conducive work environment for exchanges, sharing, and pooling together of knowledge and resources. By the time craftsmen were trained to make dolia, they had acquired considerable skills and advanced in the workshop.

Figure 4. Stamps on dolium rim (III.14.3 no. 1, Ostia): PYRAMI ENCOLPI/AVG DISP°ARCARI (left-hand side) and AMPLIATVS°VIC°F (right-hand side). Courtesy of the Photographic Archive of the Archaeological Park of Ostia Antica.

This paper examines the archaeological and epigraphic evidence for the production of dolia in central Italy and southern Gaul from the late first century BCE through second century CE. It first surveys the logistics of dolium production, highlighting the distinctive skills needed to make such large vessels. Specialized skills, which consisted of both free and enslaved labor, workshop layout and dynamics, as well as the high value of the dolia, contributed to a type of professional identity, one that both reified and defied legal conventions since some workers were enslaved and/or manumitted. Various epigraphic material even provides the names and status of several dolium makers, enabling us to trace the trajectories of several individuals. Finally, this paper considers dolium makers alongside the enslaved potter David Drake to note the limits of our knowledge about skilled and enslaved craftsmen. Combining archaeological and ethnographic work with epigraphic evidence, this paper shows that professional accomplishments would not necessarily translate to fame, social status, wealth, or even freedom for craftspeople.

The logistics of making dolia

Because dolia were enormous and top-heavy pots, making them was challenging and time-consuming, and was considered the most specialized type of ceramic production in antiquity (Plato, Gorgias 514e, Laches 187b). Dolium production was unlike the production of smaller types of pottery on the wheel: it required mastery over a different set of materials and skills. Without an account from the ancient world about this process from the perspective of the dolium maker, we are instead informed by archaeological evidence as well as ethnographic studies on dolium-like vessels still made and used today, such as Greek pithoi (Blitzer Citation1990), Georgian qvevri (Barisashvili Citation2011), Spanish and Portuguese tinajas (Romero and Cabasa Citation1999), and Korean onggi (Kang Citation2015). Potters and workshops that still practice this scale of traditional pottery production shed light on how people in antiquity constructed these vessels, as well as the strategies they employed. Despite the millennia between ancient Rome and today, the production of large vessels was driven by many of the same concerns and material constraints that spanned across time.

Dolia were highly valued vessels not only because of the great quantity of material needed to build them (hundreds of kilograms of clay), but also because of the high levels of skill to shape and fire them, the amount of time required, and the risk of production flaws or even failure. Only the most experienced specialists produced dolia. Plato’s reference suggested that a potter learned their craft by ascending levels of difficulty, reaching dolia-making at the height of their training. Several experiments in recreating and using dolia for wine production have confirmed that a subpar vessel would be too porous and result in unhygienic conditions, oxidation of the wine, and even losses of wine (Caillaud Citation2020; Indelicato Citation2020). Still in the fourth century CE, potential customers were advised to visit the workshops to make sure the clay was of good quality and products sound prior to buying (Geoponika 6.3).

The first step in dolium production began with collecting and preparing clay. Getting and preparing the raw materials for dolium production drew on practical knowledge and was similar to clay preparation for brick and tile production. Workers mined clay in the late summer or early autumn and then left it to weather to become more workable and less likely to have flaws and defects. Workers processed the clay by removing large impurities and adding temper and stable ballast. The groggy clay body characteristic of dolia, bricks, and tiles, used coarse clays high in alumina and silica, such as ground-up fired clay from discarded pottery, bricks, tiles. These were particularly stable and imparted strength and resistance against distortions, and against impurities that could cause radiating cracks during air-drying or firing. Because these issues made dolia vulnerable to production-based defects, workshops developed their own clay mixes with different additives, such as grog, sand, or plant fibers, to make the clay more workable and structurally strong (Carrato et al. Citation2019).

The next step was to form dolia, which was time-consuming and onerous skilled work. Based on ancient evidence and contemporary pottery production, these vessels were too large to throw on a standard pottery wheel and were usually coil-built over the course of several days or even weeks (Geoponika 6.3.4; Carrato Citation2017; Cheung Citation2024; Cheung and Tibbott Citation2020; Peña Citation2007). Evidence from dolia at Pompeii, Ostia, and Rome show that dolium makers built the dolia gradually with coils on a slow-turning wheel or turntable starting with a disc of clay to form a small base (). Seams on the dolia point to dolium makers progressively adding hand-squeezed or rolled coils to allow them to dry sufficiently to support the weight of the next coil, adding one to three coils each day. Potters generally smoothed the seams between the coils as the vessel was built up and sometimes paddled or scored surfaces of the coils to increase joining between coils. Seams on areas that were difficult to reach suggest that coils were c. 10 cm high. If the previous coil did not bond properly with the next, horizontal cracks could form between the seams, and even lead to the jar breaking.

Figure 5. Production and repair of dolia; (1)–(3) show evidence of producing dolia (coil building); (4)–(7) show evidence of dolium repair: (4) lead fills, (5) double dovetail tenons, (6) staples, and (7) hybrid repairs. Illustrated by Gina Tibbott.

The dolia in Ostia and Rome as well as other sites also showed that well-made dolia could still exhibit production defects such as horizontal cracks between improperly joined coils or vertical cracks, known as dunting, that developed when the ceramic body shed water unevenly during the drying process. Dolium repairs thus became critical and widespread not only for the use and maintenance of dolia, but also during their production (Cheung Citation2021, Citation2024; Cheung and Tibbott Citation2020; Peña Citation2007). Members of the workshop, whether the dolium makers themselves, other craftsmen, or contract workers, mended and reinforced dolia during the production process. They often identified and remedied defects or places of weakness before firing them in the kiln, and then filled those areas with lead and lead-based alloys after the vessels were fired. The neatness and consistency of the repairs point to the defects being formed before firing and the lead added after firing, a process confirmed by experimentation (Rando Citation1996).

Firing dolia was also a challenging and lengthy process. The hefty vessels had to be air-dried thoroughly for weeks to avoid explosions in the kiln, and loaded carefully not only due to their heftiness but also so the vessels would be evenly exposed, a process much trickier than loading standard-sized bricks and tiles. The firing process itself also required skill and expertise – too low a temperature and the vessels would be porous and leaky, too hot and they could become distorted or friable – and likely spanned several days, followed by several days for the kiln to cool gradually, otherwise the vessels would undergo thermal shock and crack. Due to the long drying times, the production of these large vessels probably took place during the warm, dry months of April to September, as did other ceramic and terracotta production, as well as the agricultural and shipping activities that surrounded wine production.

Organization of workshops

Dolium production needed not only highly specialized skill, but also significant capital and funding before the dolia could turn a profit. The lengthy production process meant that the vessels would not be finished until months after the work began. Making dolia therefore relied on a skilled labor force, abundant materials, and expensive equipment that required upfront capital, investments that only well-financed workshops could provide. Although ethnographic and archaeological work show the presence of itinerant potters making large storage jars on site, workshops during the Roman period provided a fixed space that enabled not only the installation of permanent structures and equipment, such as vats and kilns, but also the accumulation and transmission of knowledge (Christakis Citation1996; Day Citation1986). A survey of ceramic workshops in central Italy found that many workshops were set in the agro-processing and workshop areas of farms or villas. These rural workshops supplied the farm or villa with ceramic and terracotta products necessary for the operations on site, such as viticulture, olive oil production, and general construction (Olcese Citation2012; ). Workshops, especially larger ones, were also set near sources of important materials such as high-quality clay, water, and wood, as well as near other workshops (Goodman Citation2016). As early as the second century BCE, Cato described Trebla Alba and Rome as major production centers for dolia (de Agri Cultura 135). Archaeological evidence indicates that opus doliare workshops clustered along the Tiber River within 50 km of Rome supplied not only the city of Rome and its markets, but also more distant communities by the first century CE (Steinby Citation1975, Citation1987). Unfortunately, most of these sites are not well preserved, but one in southern Gaul provides insight into a dolium workshop’s layout and organization.

Table 1. Dolium production sites in central Italy (Bergamini Citation2007; Olcese Citation2012; Tol and Borgers Citation2016).

The unique case of Saint Bézard à Aspiran in Gallia Narbonensis during the late first century BCE into the first century CE reveals an expansive rural estate that featured not only a large villa with urban amenities such as a bath complex, but also a large-scale viticultural enterprise and opus doliare workshop (Mauné et al. Citation2010). The villa’s wine production is evidenced by its large wine fermentation area with over 300 dolia sunk into the earth, together capable of holding 420,000–450,000 liters of wine. In order to supply the viticultural estate, the villa also featured a large ceramic and terracotta workshop, with multiple clay levigation tanks and kilns to manufacture dolia, amphorae, and bricks and tiles on site. The clay processing tanks, all clustered together, as well as the same groggy clay found across opus doliare products, suggest that workers prepared the clay in a central area for the workshop’s different products. The kilns, on the other hand, were designed for specific products and clustered according to their use. Some kilns were designated for the firing of sigillata pottery whereas a group of kilns, at least three, in the northeastern sector of the estate was used for the firing of dolia. The physical layout of the ceramic workshop suggests a division among the workers making the range of objects and dolium makers. Saint Bézard à Aspiran was not the only example of workshops producing multiple products. Even some of the earliest workshops producing dolia were also making heavy terracotta objects, most commonly bricks, tiles, amphorae, and coarseware pottery (Cheung Citation2024). Dolium production on its own was rare. Instead, both archaeological and epigraphic evidence points to the entanglement of dolium production with other ceramic and terracotta objects from its inception (Olcese Citation2012).

Dolium stamps from the region around the capital also reveal multiple workshops with more complex organization and dolium production being intertwined with the manufacture of other terracotta objects (CIL X, XIV, XV; Bloch Citation1947, Citation1948). Many workshops stamped their ceramic and terracotta products as a form of internal control over a workshop’s production. Stamps often affirmed and guaranteed the quality of a product, and included information for the customer, tracing the product back to the workshop and giving a sense of the workshops’ organization. Numerous workshop owners named in dolium stamps, such as the Fabianae and Sulpicianae, have also been found on other heavy terracotta objects, testifying to the range of products their workshops supplied (Lazzeretti and Pallecchi Citation2005). As the historian Pliny the Elder noted, heavy terracotta objects such as dolia, bricks, tiles, and pipes were in high demand in the Roman world, serving different needs, from viticulture to water management to construction (NH 35.56). Because these products shared the same groggy ceramic makeup and required the same equipment (kilns, tanks, et al.), opus doliare workshops usually diversified their production around these different products. Based on both the epigraphic and archaeological evidence, opus doliare workshops intertwined the production of dolium with construction materials, as nearly all the workshops that produced dolia also manufactured bricks and tiles, and offered different types of opportunities for the workers, including training and advancement within the workshop.

Learning and distinctions within the workshop

The frequent overlap between landowners and workshop managers mentioned on both dolium stamps and on brick stamps point to an organization of workers with different sectors of production entrusted to different positions (Lazzeretti and Pallecchi Citation2005; ). Often a workshop would have several workers in charge of construction materials, a different set overseeing dolium production, and another group in charge of mortaria, thick bowls used for pounding foods. Because tiles, bricks, dolia, and mortaria were all made of the same ceramic body, but each product required varying degrees of specialized craft knowledge and skill, workshops with larger workforces could have designated workers responsible for certain tasks (collecting clay, kiln firing) or products (bricks, tiles, mortaria, and dolia), and perhaps even opportunities to train and advance. Within an opus doliare workshop, different workers could learn and oversee the various steps for making a dolium, allowing them to specialize in the construction of these enormous vessels. Learning could even begin with other, simpler opus doliare products, such as brick-molding and then tile production to master control over groggy clay (tiles could easily warp) before advancing to larger objects such as basins, mortaria, and amphorae.

Table 2. Opus doliare workshops producing dolia and other terracotta (Lazzeretti and Pallecchi Citation2005).

Stamps found on various ceramic objects reveal the training and multiple skills of one such craftsman. Corinthus, an enslaved potter working in the workshop of C. Cluentius Ampliatus, not only stamped two dolia found in Pompeii, but had also signed a flanged tile. He has also been identified as the enslaved potter of Publius Cornelius Corinthus, who made a large, decorated terracotta jug, suggesting that the potter Corinthus not only oversaw general opus doliare production, but was also responsible for different ceramic goods – jugs, tiles, and dolia – and probably learned and ascended the ranks in the process (Spinazzola Citation1953). Corinthus gradually acquired different skills from pottery production on the wheel to working with groggy clay to making large tiles to making dolia. The production of tiles (and bricks, which used molds) entailed skills in working with groggy clay but was not as prone to failure or major losses as dolium production. The example of Corinthus shows a craftsman able to work his way up in the hierarchy of the workshop. Such skilled, enslaved craftsmen offered or could be rented or leased for their lucrative labor, as Corinthus was enslaved by P. Cornelius Corinthus but also worked for C. Cluentius Ampliatus at one point (Ulp. Dig. 16.3.1.9; Benton Citation2020).

Opus doliare workshops often employed enslaved workers, who could gain high positions within the workshop. At least 30% of the dolium stamps feature the title ser(vus/a), ‘slave’, which identified the makers or officinatores of dolia as enslaved. Some of these stamps also include a name in the genitive to identify the enslaver. C. Cornelius Felix, for example, has been attested on dolia in Rome, while his enslaved potters, Cimber and Calateus, have been attested on both bricks and dolia in Rome (Bloch Citation1947, 479–480). M. Fulvius and his dozen slaves also dominated the opus doliare scene, producing bricks, tiles, terracotta sarcophagi, and dolia for Rome, Ostia, and beyond (Bloch Citation1947, 299–310). Given the seasonality of ceramic production and agricultural work, having enslaved labor was one way to ensure a steady and reliable labor supply, which was crucial for craft specialization. The training to become a successful dolium maker was probably restricted to people who had access to the resources and means to complete a lengthy and (perhaps unpaid or low paid) apprenticeship (Groen-Vallinga and Tacoma Citation2017; Wendrich Citation2012; Laes Citation2015), but could also have offered social and economic resources for those from less wealthy families (Freu Citation2016; Vuolanto Citation2015). Most of these were probably talented slaves of wealthy owners or the workshop owners themselves who could afford, and invested in, a skilled workforce with specialized knowledge. Employing enslaved craftsmen in the opus doliare workshops likely enabled the workers to develop their skills and/or entrepreneurial profiles further, especially if they would eventually be manumitted and act as agents for their former enslaver (Broekaert Citation2016; Cohen Citation2023).

Working in an opus doliare workshop seemed to offer opportunities not only to learn and specialize within the workshop, but also social advancements such as manumission (Erdkamp Citation2015; Hawkins Citation2016, Citation2017; Weaver Citation1998). Multiple dolium stamps indicate that many of the dolium makers and/or officinatores were able to rise in the ranks, perhaps based on their performance and mastery of the craft. A significant number were enslaved and then manumitted and ‘promoted’ to supervisory roles, sometimes with enslaved workers of their own, suggesting the incentives in dolium production were substantial and even life changing. Such an arrangement could be advantageous to both parties, as freedmen often continued to benefit from their former enslaver’s resources, while masters could employ their trustworthy freedmen as agents without liability for their business deals (Broekaert Citation2016). Dolium stamps show that the officinatores C. Vibius Fortunatus and C. Vibius Crescens, initially slaves of C. Vibius Donatus, were manumitted and continued to work as officinatores (Bloch Citation1947, 564–565).

The epigraphic evidence for the Tossius family provides an even fuller view onto the internal dynamics, opportunities, and staff within a prominent opus doliare workshop (Gregori Citation1994). The Tossius workshop, along the Tiber River Valley, was prolific and widely distributed its ware, much of which was stamped, mostly across central Italy but even as far as southern Gaul during the first century CE (Carrato Citation2017). The opus doliare stamps from the Q. Tossius workshop document at least six individuals in the business, one of which, Q. Tossius Cimber, was first attested as a slave of Q. Tossius Ingenuus (Taglietti Citation2015; CIL XV 2501–2507; Bloch Citation1947, 504, 553, 556–558). He was later freed and then became an officinator, with two slaves of his own, Redemptus and Euphrastus, who produced opus doliare products. The stamps of imperially owned opus doliare workshops show even more complexity and opportunity among the enslaved and manumitted workers: one dolium was made by an enslaved vicarius (‘master-slave’) named Ampliatus, subservient to an enslaved arcarius (‘cashier’) named Pyramus who controlled the figlinae, who in turn was enslaved under the imperial dispensator (‘manager’ or ‘superintendent’) Encolpus, whose duties included administering the emperor’s properties (; Bloch Citation1947, 537; Gamauf Citation2023a, Citation2023b; Weaver Citation1998). Some of the imperial freedmen in imperial figlinae, which were particularly successful and the dominating opus doliare workshops by the third century, reached an especially elevated position and were even co-owners of some properties (Buongiorno Citation2023).

Conclusion

Dolium makers underwent specialized and challenging training to construct valuable, large-scale dolia for the fermentation and storage of liquid products, and the pride they took in their skills, craft knowledge, and products could lead to a type of professional identity, distinctive both within the workshop and beyond it (Joshel Citation1992; Lis and Soly Citation2017; Tran Citation2017; Verboven and Laes Citation2017). One’s professional and occupational identity could be shaped by a range of factors, from the layout and size of the workshop to the types of interactions with customers and other workers (Flohr Citation2016). Hierarchy within the workshop seems likely based on the opus doliare stamp evidence. Individuals entrusted with making or overseeing the production of dolia would have had their own stamps to mark the expensive vessels with their names, further distinguishing them from the rest of the workshop.

A final example of such professional distinction can be found on a peculiar stone funerary altar along the Via Appia near the ancient town of Calatia in Campania, commissioned by a man named Lucius Aurelius Sabinus in the late first or second century CE (, CIL X 403 = 483; Zimmer Citation1982). In the Latin portion of the bilingual Greek and Latin text, L. Aurelius called himself a doliarius, an unusual and rare Latin word meaning ‘dolium maker’. Lucius Aurelius Sabinus chose not to include other information about himself. Also engraved into the stone funerary altar was a depiction of three jars: a large amphora in the foreground and, in the background, two dolia standing upright, perhaps a representation of the vessels that the doliarius fabricated. He must have also commanded some wealth, at least enough to commission a stone funerary altar and, as the Latin inscription also specifies, ‘for himself and his own’, while the Greek portion of the inscription names a L. Aurelius Lapynos Onagris and Aurelius, individuals who might have worked (and were possibly enslaved) under L. Aurelius Sabinus.

Figure 6. A funerary altar for a doliarius. Illustrated by Gina Tibbott after Zimmer (Citation1982).

Although L. Aurelius Sabinus and other dolium makers might have reaped some benefits of being a storage jar potter, the life of David Drake, with which we began, cautions us against conflating craft skill and occupational success with wealth or status. While an occupational or professional identity could have been a source of pride, income, and perhaps even a path to freedom, it is unclear even among the named workers what they had to endure or sacrifice to reach their positions within the workshop. Were dolium makers punished if they made a mistake? Did training entail certain forms of discipline? Why were some dolium makers manumitted, but not others, and at what rates? Manumission granted conditional freedom, with some manumitted officinatores still working for the same workshops and enslavers-turned-employers. Furthermore, some of the enslaved, and then manumitted, officinatores might have gained financially and socially, but many more enslaved workers never came close to reaching those ranks and their names, and existence, have not been recorded. ‘Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina’ featured several signed works by David Drake, but it also showcased pottery made by anonymous enslaved potters in Edgefield. David Drake’s and dolium makers’ work might have fetched high prices, but their enslavers, who could be enslaved themselves, and the pottery workshop owners were the ones who pocketed the profits and wielded considerable power over their fates (Cohen Citation2023).

Acknowledgement

I thank Kim Bowes, Jared Benton, and the two anonymous reviewers for their feedback and engagement with the article. This publication was supported by the Princeton University Library Open Access Fund.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Caroline Cheung

Caroline Cheung is Assistant Professor of Classics at Princeton University. Her research primarily concerns the socio-economic history of the late Republic and Roman Empire, with a focus on ancient agriculture and food; technology, craft production, and labor; and urban and rural relations. She is the author of Dolia: The Containers That Made Rome an Empire of Wine, forthcoming with Princeton University Press in 2024. She participates in various archaeological projects in Italy.

References

- Barisashvili, G. 2011. Making Wine in Qvevri—A Unique Georgian Tradition. Tbilisi: Biological Farming Association, Elkana.

- Benton, J. T. 2020. The Bread Makers: The Social and Professional Lives of Bakers in the Western Roman Empire. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bergamini, M. 2007. Scoppieto 1: Il territorio e i materiali. Florence: All’Insegna del Giglio.

- Blitzer, H. 1990. “KOPΩ NEÏKA: Storage Jar Production and Trade in the Traditional Aegean.” Hesperia 59 (4): 675–711. https://doi.org/10.2307/148081.

- Bloch, H. 1947. I bolli laterizi e la storia edilizia romana: Contributi all’archeologia e alla storia di Roma. Rome: Comune di Roma, Ripartizione antichità e belle arti.

- Bloch, H. 1948. The Roman Brick Stamps Not Published in Volume XV 1 of the “Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum”. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Studies in Classical Philology.

- Broekaert, W. 2016. “Freedmen and Agency in Roman Business.” In Urban Craftsmen and Traders in the Roman World, edited by A.I. Wilson and M. Flohr, 222–253. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Buongiorno, P. 2023. “Social Status ‘Without’ Legal Difference. Historiography and Puzzling Legal Questions About Imperial Freedmen and Slaves.” In The Position of Roman Slaves: Social Realities and Legal Differences, edited by M. Schermaier, 67–86. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Caillaud, C. 2020. “Pour une meilleure compréhension des vinifications antiques en dolia: Approches expérimentales et ethnographiques.” In Nouvelles recherches sur les dolia: L’exemple de la Méditerranée nord-occidentale à l’époque romaine (Ier s. av. J.-C.–IIIe s. ap. J.-C.), edited by C. Carrato and F. Cibecchini, 141–156. Montpellier: Editions de l’Association de la Revue archéologique de Narbonnaise.

- Carrato, C. 2017. Le dolium en Gaule Narbonnaise (Ier a.C.-IIIe S. p.C). Contribution à l’histoire socio-économique de la Méditerranée nord-occidentale. Mémoires 46. Bordeau: Ausonius Edition.

- Carrato, C., V. Martínez Ferreras, J.-M. Dautria, and M. Bois. 2019. “The Biggest Opus Doliare Production in Narbonese Gaul Revealed by Archaeometry (First to Second Centuries A.D.).” ArcheoSciences 43 (1): 69–82. https://doi.org/10.4000/archeosciences.6257.

- Chaney, M. A., ed. 2018. Where is All My Relation?: The Poetics of Dave the Potter. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Cheung, C. 2021. “Precious Pots: Making and Repairing Dolia.” In The Value of Making: Theory and Practice in Ancient Craft Production, edited by H. Hochscheid and B. Russell, 171–188. Turnhout: Brepols.

- Cheung, C. 2024. Dolia: The Containers That Made Rome an Empire of Wine. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Cheung, C., and G. Tibbott. 2020. “The Dolia of Regio I, Insula 22: Evidence for the Production and Repair of Dolia.” In Fecisti Cretaria: Dal frammento al contest; studi sul vasellame ceramic del territorio vesuviano, edited by M. Osanna and L. Toniolo, 175–185. Studi e ricerche del Parco archeologico di Pompei, 40. Rome: ‘L’Erma’ di Bretschneider.

- Christakis, K. S. 1996. “Craft Specialization in Minoan Crete: The Case for Itinerant Pithos Makers.” Aegean Archaeology 3:63–74.

- Cohen, E. 2023. Roman Inequality: Affluent Slaves, Businesswomen, Legal Fictions. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Day, P. M. 1986. “The Production and Distribution of Storage Jars in Neopalatial Crete.” In Problems in Greek Prehistory: Papers Presented at the Centenary Conference of the British School of Archaeology at Athens, Manchester, edited by E.B. French and K.A. Wardle, 499–508. Bristol: Bristol Classical Press.

- Erdkamp, P. 2015. “Agriculture, Division of Labour, and the Paths to Economic Growth.” In Ownership and Exploitation of Land and Natural Resources in the Roman World, edited by P. Erdkamp, K. Verboven, and A. Zuiderhoek, 18–39. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Flohr, M. 2016. “Constructing Occupational Identities in the Roman World.” In Work, Labour and Professions in the Roman World, edited by K. Verboven and C. Laes, 147–172. Leiden: Brill.

- Freu, C. 2016. “Disciplina, Patrocinium, Nomen: The Benefits of Apprenticeship in the Roman World.” In Urban Craftsmen and Traders in the Roman World, edited by A.I. Wilson and M. Flohr, 183–199. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gamauf, R. 2023a. “Dispensator: The Social Profile of a Servile Profession in the Satyrica and in Roman Jurists’ Texts.” In The Position of Roman Slaves: Social Realities and Legal Differences, edited by M. Schermaier, 125–164. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Gamauf, R. 2023b. “Peculium: Paradoxes of Slaves with Property.” In The Position of Roman Slaves: Social Realities and Legal Differences, edited by M. Schermaier, 87–124. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Goodman, P. 2016. “Working Together: Clusters of Artisans in the Roman City.” In Urban Craftsmen and Traders in the Roman World, Oxford Studies on the Roman Economy, edited by A. Wilson and M. Flohr, 301–333. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gregori, G. L. 1994. “Un nuovo bollo doliare di Q. Tossius Cimber.” Publications de l’École Française de Rome 193 (1): 547–553.

- Groen-Vallinga, M. J., and L. E. Tacoma. 2017. “The Value of Labour: Diocletian’s Prices Edict.” In Work, Labor and Professions in the Roman World, edited by C. Laes and K. Verboven, 104–132. Leiden: Brill.

- Hawkins, C. 2016. Roman Artisans and the Urban Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hawkins, C. 2017. “Contracts, Coercion, and the Boundaries of the Roman Artisanal Firm.” In Work, Labour, and Professions in the Roman World, edited by K. Verboven and C. Laes, 36–61. Leiden; Boston: Brill.

- Indelicato, M. 2020. “Columella’s Wine: A Roman Enology Experiment.” EXARC Journal. https://exarc.net/ark:/88735/10485.

- Joshel, S. 1992. Work, Identity, and Legal Status in Rome. Norma, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Kang, D. J. 2015. Life and Learning of Korean Artists and Craftsmen. New York: Routledge.

- Kindy, D. 2023. “Their Enslaved Ancestor’s Pottery Sells for over $1 Million. They Get Nothing.” The Washington Post, April 2, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2023/04/02/dave-potter-enslaved-descendants/.

- Koverman, J. B., ed. 1998. I Made This Jar: The Life and Works of the Enslaved African-American Potter, Dave. Columbia: McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina.

- Laes, C. 2015. “Masters and Apprentices.” In A Companion to Ancient Education, edited by W.M. Bloomer, 475–482. Chichester, Malden: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Lazzeretti, A., and S. Pallecchi. 2005. “Le figlinae “polivalenti”: la produzione di dolia e di mortaria bollati.” In Interpretare I bolli laterizi di Rome r della valle del Tevere: produzione, storia economica e topografia, edited by C. Bruun, 213–228. Rome: Institutum Romanum Finlandiae.

- Lis, C., and H. Soly. 2017. “Work, Identity and Self-Representation in the Roman Empire and the West-European Middle Ages: Different Interplays Between the Social and the Cultural.” In Work, Labour, and Professions in the Roman World, edited by K. Verboven and C. Laes, 262–290. Leiden: Brill.

- Mauné, S., B. Durand, C. Carrato, and R. Bourgaut. 2010. “The villa of Quintus Iulius Pri(…) at Aspiran (Hérault). A domanial centre in Gaul Narbonesnsis (Ist-Vth c. A.D.).” Pallas Revue d’études antiques 84 (84): 111–143. https://doi.org/10.4000/pallas.3383.

- Olcese, G. 2012. Atlante dei siti di produzione ceramica (Toscana, Lazio, Campania e Sicilia): con le tabelle dei principali relitti del Mediterraneo occidentale con carichi dall’Italia centro meridionale, IV secolo a.C.-I secolo d.C. Rome: Quasar.

- Peña, J. T. 2007. Roman Pottery in the Archaeological Record. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rando, G. 1996. “Le antiche riparazioni in piombo sui dolia provenienti dal relitto della nave romana del Golfo di Diano Marina.” In Atti del convegno internazionale della ceramic, Albisola superiore, maggio 1996. http://www.pinorando.com/Atti/atti-convegno-albisola.pdf.

- Romero, A., and S. Cabasa. 1999. La tinajería tradicional en la cerámica Española. Barcelona: Ediciones CEAC.

- Spinazzola, V. 1953. Pompei alla luce degli nuovi scavi dell’Abbondanza (Anni 1910–1923). Rome: Libreria dello Stato.

- Spinozzi, A., ed. 2022. Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Steinby, E. M. 1975. “La cronologia delle figlinae doliari urbane dalla fine dell’età repubblicana fino all’inizio del III sec.” Bullettino della Commissione Archeologica Comunale di Roma 84:7–132.

- Steinby, E. M. 1987. “Indici complementari ai bolli doliari urbani (CIL. XV,1).” Acta Instituti Romani Finlandiae 11.

- Taglietti, F. 2015. “Dolia e coperchi di dolia: Problematici assortimenti.” In Opus Doliare Tiberinum: atti delle giornate di studio (Vitero 25–26 ottobre 2012), edited by M. Spanu, 267–291. Viterbo: Dipartimento di Scienze dei Beni Culturali, Università degli Studi della Tuscia.

- Tol, G., and B. Borgers. 2016. “An Integrated Approach to the Study of Local Production and Exchange in the Lower Pontine Plain.” Journal of Roman Archaeology 29 (1): 349–370. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047759400072172.

- Tran, N. 2017. “Ars and Doctrina: The Socioeconomic Identity of Roman Skilled Workers (First Century BC–Third Century AD) 246.” In Work, Labour, and Professions in the Roman World, edited by K. Verboven and C. Laes, 246–261. Leiden: Brill.

- Verboven, K., and C. Laes, eds. 2017. Work, Labour, and Professions in the Roman World. Leiden: Brill.

- Vuolanto, V. 2015. “Children and Work. Family Strategies and Socialisation in Roman and Late Antique Egypt.” In Agents and Objects: Children in Pre-Modern Europe, edited by K. Mustakallio and J. Hanska, 97–112. Rome: Institutum Romanum Finlandiae.

- Weaver, P. 1998. “Imperial Slaves and Freedmen in the Brick Industry.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 122:238–246.

- Wendrich, W., ed. 2012. Archaeology and Apprenticeship: Body Knowledge, Identity, and Communities of Practice. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Zimmer, G. 1982. Römische Berufsdarstellungen. Berlin: Gebrüder Mann Verlag.