ABSTRACT

For archaeology to address adequately the global challenges of climate change, it needs to resolve the Climate Heritage Paradox which consists of two contradictions. Firstly, in contemporary society, when humanity anticipates and prepares for climate change and associated transformations, archaeological and other cultural heritage predominantly look backward and emphasize continuities. Secondly, when humanity on Earth needs panhuman solidarity, trust, and collaboration to be able to face enormous global challenges together, archaeological and other forms of cultural heritage are still managed and interpreted within frameworks of national governance. There is, therefore, a need for developing new understandings of cultural heritage that (a) are predominantly about stories of change and transformation rather than continuity and spatial belonging, and (b) express a need for humanity to collaborate globally and overcome national boundaries. This will protect and enhance the benefits of archaeology and cultural heritage in the age of climate change.

How do we make sense of the past in a world where the future is not what it used to be?

(Marek Tamm Citation2022, 131)

A change of times

Climate change poses one of the biggest global challenges of our times. Its impact over the coming decades threatens many people’s ways of life and livelihoods, and it may require some to relocate elsewhere. To keep the worst consequences at bay, global carbon emissions must be reduced drastically, demanding a transformation of existing ways of using resources, not the least in industry, agriculture, transport, and energy use in buildings, affecting both how people work and how they spend their daily lives (https://ourworldindata.org/emissions-by-sector). In other words, we are witnessing a global climate crisis that questions established forms of writing the history of the human species (Chakrabarty Citation2021) and indeed some of the very patterns of behaviour that have emerged during the long co-existence of human and other beings on Earth, often deeply associated with cultural traditions and other expressions of heritage. Climate change requires humans to implement profound changes in their ways of life.

In this paper, I am suggesting that the discipline of archaeology is distracting from the real challenges by promoting the conservation of tangible remains in national heritage frameworks. In this way, archaeology is exhibiting what I call the Climate Heritage Paradox. I argue that for archaeology to address adequately the global challenges of climate change, it needs to resolve the Climate Heritage Paradox and contribute actively to enhancing global human resilience.

The Climate Heritage Paradox

The ‘Climate Heritage Paradox’ consists of two contradictions that cannot be resolved by current heritage practices and demand a re-conceptualization of the very notion of cultural heritage and how we manage it.

Firstly, in contemporary society, when humanity, maybe at a larger scale than ever before, anticipates and prepares for (climate) change and numerous transformations, archaeological and other cultural heritage look backward and emphasize continuities. Both archaeology and cultural heritage remain deeply immersed in a paradigm of sameness and identity, exemplified by the preservation and conservation of sites and objects and by narratives of specific cultural groups’ traditional knowledge and belonging into particular places rooted in deep pasts.

Secondly, when humanity on Earth needs panhuman solidarity, trust, and collaboration to be able to face enormous global challenges together, archaeological and other forms of cultural heritage are usually managed and interpreted within distinct frameworks of governance provided by individual nation-states. Indeed, cultural heritage is often the result of an existing national interest and often affiliated with a specific ethnic group, reifying and promoting cultural particularism.

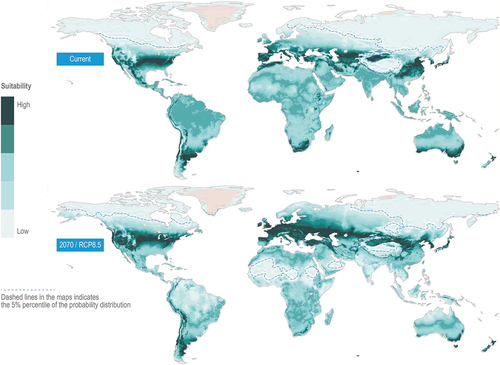

The predicament of the two paradoxes can be illustrated by two world maps depicting the projected geographical shift of the temperature niche in which humans historically have chosen to live (). The first map shows the status quo. The second map assumes that humans will be relocating (or will be relocated) in a way that would maintain a historically stable distribution with respect to temperature (Xu et al. Citation2020).

Figure 1. Projected geographical shift of the human temperature niche. Geographical position of the human temperature niche (ca 11–15°C mean annual temperature) projected on the current situation (top) and the RCP8.5 projected 2070 climate (bottom). The maps represent relative human distributions (summed to unity) for the imaginary situation that humans would be distributed over temperatures following the stylized double Gaussian model fitted to the modern data. The dashed line indicates the 5% percentile of the probability distribution. Source: Xu et al. (Citation2020) www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1910114117 (figure cropped, omitting a third map illustrating the difference between the two maps; CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

If you study the two maps carefully you will recognize two things. Firstly, there are clear changes between both distributions of human settlement locations, not the least in respect to the 5% percentile of the probability distribution. Secondly, the illustrated patterns bear no resemblance to the boundaries between existing nations or nation states but to geographical patterns and global temperature predictions. Precisely because there are state boundaries the exact distribution of future populations will not look like on the illustration, but the point is that there will be pressure on many nations and internal regions either due to people leaving or due to people arriving from elsewhere, as a result of climate change.

Although the exact figures of future movements of people due to climate change are uncertain (Heslin et al. Citation2019, 240–243), a scenario of extensive relocations is not pure speculation (Siders, Hino, and Mach Citation2019). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has been discussing the scale and impact of relocations of millions of people. In its Sixth Assessment Report, the IPCC (Citation2022, 64) stated that

In many regions, the frequency and/or severity of floods, extreme storms and droughts is projected to increase in coming decades, especially under high emissions scenarios, raising future risk of displacement in the most exposed areas (high confidence). Under all global warming levels, some regions that are presently densely populated will become unsafe or uninhabitable, with movement from these regions occurring autonomously or through planned relocation (high confidence).

As and when significant numbers of people will be displaced as a result of climate change (also known as climate refugees) and relocate or be subjected to future resettlement programmes, they will have to overcome their own and other peoples’ assumptions, long championed by archaeology, that specific cultural groups’ belong to particular spatial areas and enjoy a kind of ‘natural’ ownership of these territories and their deep heritage. It is not difficult to imagine and has often been pointed out that this place attachment will hinder or prevent successful relocations and thus make human adaptation to climate change emotionally more stressful and generally more difficult (Heslin et al. Citation2019; Simpson et al. Citation2023). More research about the consequences for heritage uses and values of human movement linked to climate change is therefore badly needed (Morel et al. Citation2022, 28–29). Addressing this issue is one way of responding to the UN Secretary-General António Guterrez’ statement in his Our Common Agenda report (Citation2021, 3) that ‘humanity’s welfare – and indeed, humanity’s very future – depend on solidarity and working together as a global family to achieve common goals’.

Essentialist and culturalist assumptions promoting ideas of distinct cultural identities associated with claims to the ownership of particular territories can undermine trust between members of different communities. As powerful symbols of group association and ‘tribal’ identity, cultural heritage can polarise, undermine social cohesion, and increase the risk of tensions and even violent conflict between communities perceiving themselves as rivals (EU Citation2021, 4). Varieties of cultural and social tribalism can distance people from each other and make divisions and violent conflicts between ‘us and them’ more likely than if they were to meet each other as individual specimen of the same human species, co-existing and inhabiting a single planet (Högberg Citation2016; Maalouf Citation[1996] 2012; Van der Laarse Citation2019; Vince Citation2022, 52f). The long-standing links between cultural heritage and nationalism, during the 20th century leading to two world wars, are well understood (most recently Bonacchi Citation2022). Concerning our own time, it has been documented how cultural heritage and its need of protection can still today be instrumentalised by military leaders to recruit and mobilise troops in ongoing wars (Isakhan and Akbar Citation2022). For the social anthropologist Sharon Macdonald (Citation2013, 162), it is an open question ‘whether it is possible to draw on memory and heritage to form new identity stories that include, rather than exclude, cultural diversity and “mixed” culture’. This is especially problematic when cultural heritage is linked to territorial claims and emotions of spatial belonging.

Because of these and other effects, safeguarding cultural heritage may mean maladaptation to climate change (Walsh et al. Citation2023). A recent policy report recommends additional research to ensure that perceptions and uses of cultural heritage that may incite conflicts over power and territory are explored in more depth (Ballard et al. Citation2022, 13–14). This corresponds with the call in another relevant report for more research on ‘culture- and heritage-based emplacement strategies to help displaced communities as well as to address the cultural impacts on receiving communities’ (Morel et al. Citation2022, 50). A particular role in this context might be played by intangible heritage (Aktürk and Lerski Citation2021). It may also be helpful to rethink the very idea of cultural heritage management and decouple it from stories of material, social, or spatial continuities over time, including a perceived necessity of protection and preservation (Holtorf Citation2015, Citation2018, Citation2020). Such rethinking goes hand in hand with the already perceptible shift in global cultural heritage policy, as described by Kathryn Lafrenz Samuels (Citation2018), from conservation to development and from national governments’ sovereignty to transnational governance patterns.

But where does all this leave archaeology and cultural heritage studies? Let us look at the extent to which the Climate Heritage Paradox appears in the thinking and practice of archaeologists and other cultural heritage experts in recent decades.

Addressing climate change in archaeology (and beyond)

In recent years, although more needs to be done, archaeologists and other heritage specialists have been successfully providing evidence about long-term environmental change and human adaptive responses to past crises (Ballard et al. Citation2022; Kohler and Rockman Citation2020; Lane Citation2015; Simpson et al. Citation2022). For example, in environmental studies, models of prehistoric climate variation and long-term human impacts on the environment have been used to discuss possible future trends (Rockström et al. Citation2009; Xu et al. Citation2020). Similarly, lessons from the past for responding, building resilience, and adapting to changing environmental conditions may be derivable from tangible cultural heritage and are directly relevant to the prospect of climate change (Van de Noort Citation2013). From archaeological understandings of past disasters and subsequent adaptation to existing hazards we can learn how past crises provide lessons for the present and may ultimately contribute to long-term human resilience (Degroot et al. Citation2021). By the same token, Turner et al. (Citation2020) argued with reference to case studies in China, the Mediterranean and the UK that knowledge gained through landscape archaeology can help stakeholders to imagine future land-use and management practices which are more sustainable than those of today in a changing climate. All such work does not suffer from the Climate Heritage Paradox and is not the subject of the present paper.

Archaeologists are also taking measures to mitigate climate change directly, e.g. by reducing their travelling or minimizing office space. And by pointing to long-term trends and implications of climate change for local or emblematic heritage sites they can communicate the urgency of mitigating climate change and advance climate action in society (Lafrenz Samuels Citation2018, 91–98; Shepherd et al. Citation2022). All this is not further considered in the present paper either.

Perhaps most prominently, however, archaeologists and other cultural heritage specialists have invested much of their efforts to worrying about the risks of a negative impact of climate change on the preservation of archaeological and historical sites and the need for safeguarding tangible cultural heritage, especially in low-lying areas near the sea where they are vulnerable to the impact of sea-level rises and extreme weather conditions associated with climate change (e.g. Barthel-Bouchier Citation2013; Ballard et al. Citation2022; Fluck and Guest Citation2022; Fluck and Wiggins Citation2017; Harvey and Perry Citation2015; ICOMOS Citation2019; Sesana et al. Citation2021; Simpson et al. Citation2022). This concern follows from the heritage sector’s conservation ethics according to which the sector has the primary duty to conserve the non-renewable cultural heritage because of its inherent value for the benefit of future generations (Holtorf Citation2015, Citation2020).

In recent years, the commitment of the cultural heritage sector to conservation inspired increasing references to cultural heritage during the annual Conference of Parties (COP) of the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and in documents by global bodies such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC Citation2022) and the International Meeting on Cultural, Heritage and Climate Change (ICSM CHC) co-sponsored by the IPCC, the International Council of Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) and UNESCO (Morel et al. Citation2022; Simpson et al. Citation2022) where the focus is often predominantly on risks of ‘loss and damage’. In the same vein, a recent conference in March 2023 in Norwich, UK, was dedicated to measuring heritage loss and damage from climate change for effective policy reporting (Dunne Citation2023). One of the main ambitions of the meeting was to find ways of having the IPCC include more prominently in future assessment reports the impact of climate change on the survival of cultural heritage. In contexts such as these, it has been appreciated in recent years that national legal frameworks of heritage conservation open up for court cases through which governments may be obliged to act on climate change (Lafrenz Samuels Citation2018, 94–95).

This preoccupation with conservation is gradually changing, as scholars have been advocating ‘averting loss aversion’ (Holtorf Citation2015), ‘curated decay’ (DeSilvey Citation2017), ‘transformative continuity’ (Seekamp and Jo Citation2020), ‘managed retreat’ (Mach and Siders Citation2021), and ‘transformative change’ (Daly Citation2022), while generally acknowledging the need for “a fundamental rethink and transformation of cultural heritage management and policy” (Fatorić and Daly Citation2023) and relativising loss and damage: ‘[i]t is not so much loss that is problematic, but how individuals, communities and societies choose to deal with it’ (Fluck and Wiggins Citation2017, 167). It is increasingly accepted that the issues at stake are much larger than the preservation of some artefacts or monuments. Tangible and intangible forms of cultural heritage can complement each other. For example, a community working for a joint purpose to save a tangible common good of heritage can enhance intangible values of wellbeing, solidarity and trust, resulting in strong social coherence and associated social benefits. These values may ultimately be even more significant for building resilience against climate change than the objects they are seemingly about (Forster et al. Citation2022), and they may be achieved even if the preservation of the heritage itself fails.

Importantly, Kathryn Lafrenz Samuels pointed out (Lafrenz Samuels Citation2018, 88) that ”climate change is as much a social and political issue as it is an environmental one, and heritage researchers and practitioners miss a large part of the problem if the social impacts of climate change on cultural heritage are ignored”. Modified land use, shifting patterns of subsistence, population movements and the emerging social tensions and conflicts which, in the context of excessive capitalism and conspicuous consumption, are related to such processes (Simpson et al. Citation2023) all have an impact on, and are influenced by, cultural heritage representing and reinforcing particular cultural ways of life. These issues are therefore on the agenda of archaeologists and other heritage specialists engaging with climate change, too: “cultural heritage management can no longer be isolated from other societal challenges, but should embrace a vision in which cultural heritage is a vector for positive transformation within society and for the benefit of future generations” (Fatorić and Daly Citation2023, 6).

We can see in these trends that some of the established certainties of cultural heritage practice, such as a preferability of preservation, were assumed and are increasingly being challenged with new issues of concern emerging. At the same time, the Climate Heritage Paradox persists – demanding solutions for how to embrace fully the changes and transformations of managing cultural heritage necessary today in an unbounded global context.

Beyond the cultural heritage paradox

Resolving the Climate Heritage Paradox requires answers to two questions in particular:

What could it mean to imagine a cultural heritage that is predominantly about stories of change and transformation, e.g. as a result of relocation and displacement, rather than about stories of conservation, continuity and spatial belonging?

What could it mean to imagine a cultural heritage that expresses and enhances a perceived need for humanity to collaborate globally and overcome national and cultural boundaries?

In addressing change and transformation in relation to cultural heritage, it is helpful to consider the notion of culture first. Often, it is assumed that culture is a kind of collective dress (or straitjacket?) into which everyone is born, and which seemingly unchangeably consigns people to certain physical effects and looks of this dress while also locking them to a given collective identity associated with a specific delineated space. For example, if you are born in the year N as a member of culture A you are normally still perceived as a member of culture A in the year N + 50. However, culture can alternatively be perceived as the framework within which each person, at a given point in time, creatively makes sense of the world and gives meaning and value to their own and other beings’ lives, framed by concepts, norms, and memories that govern whom or what people trust and feel close to, that guide their thinking and behaviour in particular social contexts, and that allow them to imagine certain things about the future and not others. This is a perspective common in social anthropology and ethnography – once expressed by Clifford Geertz (Citation1993, 16, 20) when he stated that ethnography interprets ‘the flow of social discourse’ and thus ‘brings us into touch with the lives of strangers’. According to such an alternative understanding of culture (additionally inspired by Fornäs Citation2017), cultural heritage tells the story of how individual people have been making sense of the world, of themselves, and of each other, and how this has been changing over time (Holtorf Citation2018). For example, if you are born in the year N you are beginning a long journey into and through several cultural contexts, from upbringing and education to specific occupations and various social contexts in different places, subsuming both work and personal interests.

Climate change demands to adapt human culture in all its various manifestations to a new reality yet again, shaped by emerging challenges and their global consequences, which are bigger than humans can fully control. What matters is not so much preventing or minimizing loss and damage of the human legacy inherited from the past but to ensure the preconditions for the wellbeing of fellow human and indeed non-human beings living under changing circumstances in the present and the future. That is precisely why policy-making regarding climate change adaptation needs to embrace expertise on culture (Pisor, Lansing, and Magargal Citation2023). The concern with people’s future wellbeing does not only include accepting the possibility of change, transformation, including (some) loss, but also contributing actively and courageously to creative transformation and sustainable development (Guttormsen and Skrede Citation2022; Harvey and Perry Citation2015; Holtorf Citation2018, Citation2020; Holtorf and Kristensen Citation2024; Lafrenz Samuels Citation2016, Citation2018; Seekamp and Jo Citation2020). Arguably, it is precisely human adaptability, manifested among others in continuously shifting traditional knowledge and innovative uses and values of cultural heritage, that makes human culture resilient and sustainable over time (Walsh et al. Citation2023). It is not surprising that ICOMOS selected the theme ‘Heritage Changes’ for the Scientific Symposium (at the time of writing: to be) held during the 21st Triennial General Assembly in 2024 in Sydney.

At the same time, there is a risk that ‘culturalist understandings and frameworks’, combined with ‘a general understanding of heritage as a fixed and inherently conservative category’, result in heritage acting ‘as a potential barrier to change and adaptation, manifesting a kind of cultural drag’ (Shepherd et al. Citation2022, 49). When cultural heritage hinders transformational development too much, works against change and promotes backward-looking attitudes it is not helpful for adapting to the current climate predicament because it risks creating a barrier to constructive conversations about change (DeSilvey et al. Citation2021, 420).

Such conversations may be inspired by the example of prehistoric monuments. As I argued previously (Holtorf Citation2000–2008, Citation2002), the long life-history of monuments over several thousand years from the Neolithic until today can be understood as a sequence of changing contexts manifesting several thorough transformations as a result of being encountered and interpreted by different people and used or altered for different purposes. They persisted and overcame adversity not despite but because they changed so much. Fluck and Wiggings (Citation2017, 176) put it in a nutshell when they stated that ‘Heritage, by virtue of the fact that is has survived, is almost by definition resilient: we can and should celebrate this’.

In contemplating a global and transnational context for understanding cultural heritage, let us move from addressing change over time to emphasizing human unity across space. The rigid definition of culture I mentioned earlier locks people into a diversity of collective identities and territories that are to some extent matched by national boundaries. A more fluid notion of culture and heritage, tangible and intangible, could foreground the various continuously evolving ways of behaving and making sense of the world, paving the way to the recognition that, as human beings on Earth, we have much more in common with each other than what divides us (Maalouf Citation[1996] 2012). As humans we share nearly all our genes and many biological properties with each other, our lifetimes overlap, we are adaptable and capable of learning to make our lives work within given contexts, and we share a good number of values and reference points resulting from globalism. An appreciation of broadly shared human circumstances can lay the ground for enhanced social cohesion globally and a pan-human solidarity that will be needed in addressing the impact of climate changes on all living human and non-human beings including the recognition that the global costs of humanity’s climate transition needs to be shared fairly and justly among states.

This is pertinent also for the increasing number of people migrating between world regions as global nomads, whether as refugees, for work or for family reasons, resulting in increasing heterogeneity in many contemporary nation-states (Colomer and Holtorf Citation2019; Vince Citation2022; ). In fact, the arising hybridity is common and historically unremarkable: it appears to be ‘noteworthy only from the point of view of boundaries that have been essentialized’ (Nederveen Pieterse Citation2001, 220) and that remain being reified and fetishised by tangible cultural heritage conserved in the landscape.

Solutions for cultural heritage

Contrary to some of the original intentions, inscribed UNESCO World Heritage sites are, in practice, not usually considered to represent humanity’s shared identity and instead championed by their respective nation-states as symbols of their own cultural status and political merits. Patrick Rhamey (Citation2019, 33) points out that “states seek status as recognition of their importance” and receiving World Heritage status from UNESCO can attribute such status. That can make sense in a post-colonial context where emerging national identities can provide frameworks for societal development. But sometimes, as noted earlier for cultural heritage more generally, the 1972 Convention has become a medium for expressing global tensions and underpinning conflicts between peoples and nations. This is sad but, fortunately, it is also something that can be rectified: after all, according to the famous UNESCO phrase, since wars begin in the minds of humans, it is in the minds of humans that the defenses of peace must be constructed, too.

Despite its timeliness, it may in practice not be easy to replace the concept of national heritage with more global notions of cultural heritage linked to cosmopolitan or universal varieties of citizenship. There are, however, already some discernible trends towards cross-cultural and transnational forms of heritage governance that prioritise development over conservation while side-lining the significance of nation-states (Colomer and Holtorf Citation2019; Lafrenz Samuels Citation2016, Citation2018). The focus of the World Bank on heritage-based international development and the cosmopolitanisation of Holocaust remembrance provide pertinent examples (Lafrenz Samuels Citation2018: ch. 4; Macdonald Citation2013: ch. 8). Making heritage in this way more meaningful on a global level would complement rather than substitute viable local values, for example, in indigenous communities. My point is not about power and ownership but about meaning, interpretation, and what heritage could do.

In this situation, at the supranational or transnational levels, a new programme could spearhead a particular global heritage of all humanity, going beyond the limitations of the existing 1972 Convention and making progress towards the unfulfilled universalist aspirations of the World Heritage List. Although ‘[t]he very name of “World Heritage” tends to suck all the air out of conversations around global heritage’, as Kathryn Lafrenz Samuels (Citation2018, 9) quipped, we could try and get better at realising the unique potential of the notion of a global heritage and in that way advance the prospects of humanity for the future (Holtorf Citation2022, Citation2023). This may involve asking questions like what it means to be human and what we value most about the accumulated human experience of Earth. It may also involve caring more for the heritage of human rights and the heritage of anti-racism (Shepherd et al. Citation2022, 47, 53).

Speculating for a moment – what might a provisional list of alternative criteria for outstanding universal value of global heritage look like that could truly transcend national boundaries and meet the global aspirations of the 1945 UNESCO Constitution and the UN Agenda 2030? The key might be to make global qualities transcending more narrow contexts part of the selection process for each site. In this vein, sites to be inscribed on a new Global Heritage List could be required to meet at least one of the four criteria:

To counter significantly suspicion and mistrust between the people of the world;

To promote in unique ways an understanding of the principles of dignity, equality and mutual respect for all humans, non-humans, and for the environment;

To enhance extensively the education of humanity for justice and liberty and peace; or

To advance in exceptional ways collaboration among people and nations through education, science and culture.

These formulations are taken almost directly from the 1945 UNESCO Constitution, with the environment being added from the Agenda 2030.

Given that even UNESCO World Heritage is governed by its member states, what kind of global heritage might enhance unified human identity and solidarity? A good example is the series of photographs the English beachcomber and activist Tracey Williams, entitled ‘Lego Lost at Sea’ (). Originally, much of the Lego came from the cargo ship Tokio Express that on 13 February 1997 lost a container with nearly 5 million pieces of Lego into the Sea off the coast of Cornwall (Williams Citation2022). But there were many other kinds of plastic trash to be found too, altogether representing not only the changing interface of natural and cultural heritage where plastic fragments in all sizes transform the environment but also telling the story of how global production and trade, consumption, and disposal of artefacts are interconnected through the oceans across which the raw materials, the finished product, and their deteriorating leftovers are shipped or float. Many million tons of plastic are being produced every year, and it is probably no exaggeration to state that all human beings use plastic in their daily life. Arguably, this plastic trash in the oceans and on the beaches marks one of the most important archaeological legacies of our age on Earth; it forms a distributed global heritage site promoting, among others, mutual respect for non-human lifeforms and the environment (criterium II above).

Figure 2. Panhuman identity? Toys and other plastic artefacts of the 20th century washed ashore on English beaches. Original illustration by Tracey Williams as part of the Lego Lost at Sea project (Williams Citation2022).

This example and what could be listed under the other mentioned criteria shifts the emphasis in stories of humanity from one of cultural diversity to one of global variation of a common predicament of living beings on Earth. On a planet that is changing rapidly, it is of considerable importance to celebrate the many interconnections and common interests between the various branches of humanity – and indeed between humans and other living beings. Advancing shared benefits of the human species by promoting common interests and responsibilities means to focus back on the original aims of UNESCO as defined in its 1945 Constitution.

Conclusion: heritage futures

Heritage futures is about the roles of heritage in managing the relations between present and future societies. It builds on an understanding of the perils of presentism and an associated commitment to futures literacy and foresight (Holtorf Citation2020, Citation2022). The future is uncertain but that does not mean it is futile to prepare for those parts of the future that can be anticipated.

There is an increasing interest in how the knowledge and skills of archaeologists and others can assist societies in reducing carbon emissions, enhancing their sustainability, and adapting to the impacts of climate change, even accepting loss. It was recently recognized that future research on cultural heritage should ensure that ‘future risks and opportunities of different perceptions and uses of cultural heritage for climate adaptation planning are investigated’. Moreover, ‘more research is needed on the potential of foresight and anticipation for policymaking regarding cultural heritage in relation to future climate change’ as well as ‘on the ways in which different cultural and historical responses can help us to envisage and plan multiple and alternative futures within the context of climate change’ (Ballard et al. Citation2022, 14, 17). As part of these developments, archaeology could not only tell us stories about different pasts but also about different futures, requiring us all to make use of the human powers of creativity and imagination.

Nick Brooks (Citation2023) argued recently that the climate crisis is to some extent the result of a failure of the imagination. Physically and socially, climate change will make the world a very different place, and people struggle to imagine how the world as they know it may be utterly transformed. Archaeology could help by telling stories about the many dramatic past transformations that have occurred during periods of rapid and severe climate change, requiring humans and other living beings to engage in ‘transformational adaptation’ of their lives. For example, between about 6400 and 5000 years ago snow and ice advanced at high latitudes and high altitudes, unprecedented extremes affected areas as far afield as Ireland and Iran, and deserts advanced across the northern hemisphere sub-tropics. Regions such as the Sahara provide dramatic evidence of these changes, in the form of rock art depicting large, humid climate fauna, and dry lake beds around which are scattered the remnants of prehistoric human occupation (Brooks Citation2013). Archaeology has the unique potential to demonstrate how large changes in climatic and environmental conditions precipitated profound changes in human society and culture. Indeed, all cultural heritage, tangible and intangible, can and should be seen in terms of change and creative transformation over time (Holtorf Citation2018, Citation2020; Seekamp and Jo Citation2020; Walsh et al. Citation2023).

In the context of contemporary and future climate change, I argued in this paper that it is pertinent to try and overcome the Climate Heritage Paradox by developing an understanding of cultural heritage that (a) is predominantly about stories of change and transformation rather than of conservation, continuity, and spatial belonging, and (b) expresses and enhances a perceived need for humanity to collaborate globally and overcome national boundaries. Addressing the Climate Heritage Paradox in this way means moving attention from safeguarding objects and the national heritage to which they are said to belong to protecting and enhancing the benefits of archaeology and cultural heritage for all beings on Earth. It also means recognizing the significance of culture for climate change adaptation (Pisor, Lansing, and Magargal Citation2023).

Perhaps never before has the potential of cultural heritage to contribute actively to managing the relations between present and future societies been more important than now. It seems as if the very existence of a future humanity (and indeed of many other living beings on Earth) is at stake in the Anthropocene – whether that may be due to warfare, environmental pollution, global inequalities, artificial intelligence, nuclear weapons, new viruses, or especially climate change. Culture and heritage may be part of the solution, not the least when it is rethought along the lines suggested in this paper so that it can – perhaps to a larger extent than ever before – increase human (and non-human) wellbeing and contribute to sustainable development now and in the future.

Acknowledgments

The ideas here described as the Climate Heritage Paradox were first proposed on a poster presented at the International Co-sponsored Meeting on Culture, Heritage and Climate Change in 2021. Some short passages are based on Holtorf Citation2023. For comments and suggestions to a penultimate version I would like to thank Nick Brooks, Elena Maria Cautis, Joanne Clark, Anders Högberg, and Hana Morel. Two referees prompted me to clarify a few issues, for which I am grateful. The final version was prepared while holding a Getty Conservation Guest Scholarship in Los Angeles. I am particularly grateful to Tracey Williams for preparing and supplying Figure 2.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Cornelius Holtorf

Cornelius Holtorf is Professor of Archaeology and holds a UNESCO Chair on Heritage Futures at Linnaeus University in Kalmar, Sweden. His research interests include archaeology and cultural heritage in the contemporary world, heritage theory, and heritage futures. He is co-editor (with A. Högberg) of the volume Cultural Heritage and the Future (Routledge 2021).

References

- Aktürk, Gül, and Martha Lerski. 2021. “Intangible Cultural Heritage: A Benefit to Climate-Displaced and Host Communities.” Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 11 (3): 305–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-021-00697-y.

- Ballard, Christopher, Nacima Baron, Ann Bourgès, Bucher, Bénédicte, Cassar, May, Daire, Marie-Yvane, Daly, Cathy et al. 2022. “White Paper on Cultural Heritage and Climate Change: New Challenges and Perspectives for Research.” Joint Programming Initiatives “Cultural Heritage and Global Change” (JPI CH) and “Connecting Climate Knowledge for Europe” (JPI Climate). https://www.heritageresearch-hub.eu/white-paper-cultural-heritage-and-climate-change-new-challenges-and-perspectives-for-research/ .

- Barthel-Bouchier, Diane. 2013. Cultural Heritage and the Challenge of Sustainability. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast.

- Bonacchi, Chiara. 2022. Heritage and Nationalism. Understanding Populism Through Big Data. London: UCL Press.

- Brooks, Nick. 2013. “Beyond Collapse: Climate Change and Causality During the Middle Holocene Climatic Transition, 6400–5000 Years Before Present.” Geografisk Tidsskrift-Danish Journal of Geography 112 (2): 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/00167223.2012.741881.

- Brooks, Nick. 2023. “Heritage, Climate Science & the IPCC.” Paper Presented at the Conference “Measuring Heritage Loss and Damage from Climate Change for Effective Policy Reporting, U.K.: University of East Anglia, March 30.

- Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 2021. The Climate of History in a Planetary Age. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Colomer, Laia, and Cornelius Holtorf. 2019. “What is Cross-Cultural Heritage? Challenges in Identifying the Heritage of Globalized Citizens.” In Cultural Heritage, Ethics and Contemporary Migrations, edited by Cornelius Holtorf, Andreas Pantazatos, and Geoffrey Scarre, 147–164. London: Routledge.

- Daly, Cathy. 2022. “Climate Action and World Heritage: Conflict or Confluence?” In 50 Years World Heritage Convention: Shared Responsibility – Conflict & Reconciliation, edited by Marie-Theres Albert, Roland Bernecker, Claire Cave, Anca Claudia Prodan, and Matthias Ripp, 239–251. Cham: Springer.

- Degroot, Dagomar, K. Anchukaitis, M. Bauch, J. Burnham, F. Carnegy, J. Cui, K. de Luna, et al. 2021. “Towards a Rigorous Understanding of Societal Responses to Climate Change.” Nature 591 (7851): 539–550. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03190-2.

- DeSilvey, Caitlin. 2017. Curated Decay. Heritage Beyond Saving. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- DeSilvey, Caitlin, Harald Fredheim, Hannah Fluck, Rosemary Hails, Rodney Harrison, Ingrid Samuel, and Amber Blundell. 2021. “When Loss is More: From Managed Decline to Adaptive Release.” Historic Environment 12 (3–4): 418–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/17567505.2021.1957263.

- Dunne, Saisy. 2023. “Loss and Damage: How Can Culture and Heritage Loss Be Measured and Addressed?” Carbonbrief, April 5. https://www.carbonbrief.org/loss-and-damage-how-can-culture-and-heritage-loss-be-measured-and-addressed/.

- EU. 2021. “Concept on Cultural Heritage in Conflicts and Crises.” Council of the European Union, European External Action Service. 9962/21. https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-9962-2021-INIT/en/pdf.

- Fatorić, Sandra, and Cathy Daly. 2023. “Towards a Climate-Smart Cultural Heritage Management.” WIREs Climate Change 14:e855. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.855.

- Fluck, Hannah, and Kate Guest, eds. 2022. “Climate Change and Archaeology.” EAC Symposium Proceedings. Internet Archaeology, 60. https://intarch.ac.uk/journal/issue60/index.html.

- Fluck, Hannah, and Meredith Wiggins. 2017. “Climate Change, Heritage Policy and Practice in England: Risks and Opportunities.” Archaeological Review from Cambridge 32 (2): 159–181.

- Fornäs, Johan. 2017. Defending Culture – Conceptual Foundations and Contemporary Debate. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Forster, Johanna, Clare Shelton, Carole S. White, Agathe Dupeyron, and Alena Mizinova. 2022. “Prioritising Well-Being and Resilience to ‘Build Back better’: Insights from a Dominican Small-Scale Fishing Community.” Disasters 46 (S1): S51–S77. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12541.

- Geertz, Clifford. 1993. The Interpretation of Cultures [1973]. London: Fontana.

- Guterres, António. 2021. Our Common Agenda. Report of the Secretary-General. New York: United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/content/common-agenda-report/.

- Guttormsen, Torgrim S., and Joar Skrede. 2022. “Heritage and Change Management.” In Routledge Handbook of Sustainable Heritage, edited by Kalliopi Fouseki, May Cassar, Guillaume Dreyfuss, and Kelvin A. K. Eng, 30–43. London: Routledge.

- Harvey, David C., and Jim Perry, eds. 2015. The Future of Heritage as Climate Change. Loss, Adaptation and Creativity. London: Routledge.

- Heslin, Alison, Natalie Delia Deckard, Robert Oakes, and Arianna Montero-Colbert. 2019. “Displacement and Resettlement: Understanding the Role of Climate Change in Contemporary Migration”. In Loss and Damage from Climate Change, Climate Risk Management, Policy and Governance, edited by Reinhard Mechler, Laurens M. Bouwer, Thomas Schinko, Swenja Surminski, and JoAnne Linnerooth-Bayer, 237–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-72026-5_10.

- Högberg, Anders. 2016. “To Renegotiate Heritage and Citizenship Beyond Essentialism.” Archaeological Dialogues 23 (1): 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1380203816000076.

- Holtorf, Cornelius. 2000–2008. “Monumental Past: The Life-Histories of Megalithic Monuments in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (Germany).” Electronic Monograph. University of Toronto: Centre for Instructional Technology Development. http://hdl.handle.net/1807/245.

- Holtorf, Cornelius. 2002. “Excavations at Monte da Igreja Near Évora (Portugal), from the Life-History of a Monument to Re-Uses of Ancient Objects.” Journal of Iberian Archaeology 4:177–201.

- Holtorf, Cornelius. 2015. “Averting Loss Aversion in Cultural Heritage.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 21 (4): 405–421.

- Holtorf, Cornelius. 2018. “Embracing Change: How Cultural Resilience is Increased Through Cultural Heritage.” World Archaeology 50 (4): 639–650. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2018.1510340.

- Holtorf, Cornelius. 2020. “Conservation and Heritage as Creative Processes of Future-Making.” International Journal of Cultural Property 27 (2): 277–290. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0940739120000107.

- Holtorf, Cornelius. 2022. “To Adapt to a Changing World, Heritage Conservation Needs to Look Toward the Future.” The Conservation, September 22. https://theconversation.com/to-adapt-to-a-changing-world-heritage-conservation-needs-to-look-toward-the-future-190468.

- Holtorf, Cornelius. 2023. “Towards a World Heritage for the Anthropocene.” In Rethinking Heritage in Precarious Times, edited by Nick Shepherd, 111–126. London: Routledge.

- Holtorf, Cornelius, and Troels Myrup Kristensen. 2024. “Reconsidering Heritage Destruction and Sustainable Development in a Long‑Term Perspective.” In The Routledge Handbook of Heritage Destruction, edited by A. González Zarandona, E. Cunliffe, and M. Saldin, 413–423. London and New York: Routledge.

- ICOMOS. 2019. “The Future of Our Pasts: Engaging Cultural Heritage in Climate Action. Heritage and Climate Change Outline.“ ICOMOS: Climate Change and Heritage Working Group. https://www.icomos.org/en/77-articles-en-francais/59522-icomos-releasesfuture-of-our-pasts-report-to-increase-engagement-of-cultural-heritage-in-climate-action.

- IPCC. 2022. “Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability.” In Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by Hans-Otto Pörtner, Debra C. Roberts, Melinda M.B. Tignor, Elvira Poloczanska, Katja Mintenbeck, Andrés Alegría, Marlies Craig, Stefanie Langsdorf, Sina Löschke, Vincent Möller, Andrew Okem, Bardhyl Rama. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844.

- Isakhan, Benjamin, and Ali Akbar. 2022. “Problematizing Norms of Heritage and Peace: Militia Mobilization and Violence in Iraq.” Cooperation and Conflict 57 (4): 516–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/00108367221093161.

- Kohler, Timothy, and Marcy Rockman. 2020. “The IPCC: A Primer for Archaeologists.” American Antiquity 85 (4): 627–651. https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2020.68.

- Lafrenz Samuels, Kathryn. 2016. “Transnational Turns for Archaeological Heritage: From Conservation to Development, Governments to Governance.” Journal of Field Archaeology 14 (3): 355–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/00934690.2016.1174031.

- Lafrenz Samuels, Kathryn. 2018. Mobilizing Heritage. Anthropological Practice and Transnational Prospects. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Lane, Paul J. 2015. “Archaeology in the Age of the Anthropocene: A Critical Assessment of Its Scope and Societal Contributions.” Journal of Field Archaeology 40 (5): 485–498. https://doi.org/10.1179/2042458215Y.0000000022.

- Maalouf, Amin. [1996] 2012. In the Name of Identity. Violence and the Need to Belong. New York: Arcade.

- Macdonald, Sharon. 2013. Memorylands. Heritage and Identity in Europe Today. London: Routledge.

- Mach, Katharine J., and A. R. Siders. June 18, 2021. “Reframing strategic, managed retreat for transformative climate adaptation.” Science 372 (6548): 1294–1299. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abh1894.

- Morel, Hana, William Megarry, Andrew Potts, Jyoti Hosagrahar, Debra Roberts, Yunus Arikan, Eduardo Brondizio, et al. 2022. “Global Research and Action Agenda on Culture, Heritage and Climate Change.” Project Report. Charenton-le-Pont, France & Paris: ICOMOS & ISCM CHC.

- Nederveen Pieterse, Jan. 2001. “Hybridity, so What? The Anti-Hybridity Backlash and the Riddles of Recognition.” Theory, Culture & Society 18 (2–3): 219–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/02632760122051715.

- Pisor, Anne, J. Stephen Lansing, and Kate Magargal. 2023. “Climate Change Adaptation Needs a Science of Culture.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 378:20220390. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2022.0390.

- Rhamey, Patrick. 2019. “Status and the Protection of Heritage Sites in Times of Conflict.” In Heritage Revivals – Heritage for Peace, 32–35. Bucharest: Romanian National Commission for UNESCO. https://www.cnr-unesco.ro/uploads/media/revista_HERE_eng.pdf.

- Rockström, Johan, Will Steffen, Kevin Noone, Åsa Persson, F. Stuart Chapin III, Eric F. Lambin, Timothy M. Lenton, et al. 2009. “A Safe Operating Space for Humanity.” Nature 461:472–475. https://doi.org/10.1038/461472a.

- Seekamp, Erin, and Eugene Jo. 2020. “Resilience and Transformation of Heritage Sites to Accommodate for Loss and Learning in a Changing Climate.” Climatic Change 162:41–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-020-02812-4.

- Sesana, Elena, Alexandre S. Gagnon, Chiara Ciantelli, JoAnn Cassar, and John J. Hughes. 2021. “Climate Change Impacts on Cultural Heritage: A Literature Review.” WIREs Climate Change 12 (4). https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.710.

- Shepherd, Nick, Joshua Benjamin Cohen, William Carmen, Moses Chundu, Christian Ernsten, Oscar Guevara, Franziska Haas, et al. 2022. ICSM CHC White Paper III: The Role of Cultural and Natural Heritage for Climate Action: Contribution of Impacts Group III to the International Co-sponsored Meeting on Culture, Heritage and Climate Change, Charenton-le-Pont and Paris: ICOMOS & ISCM CHC.

- Siders, A. R., Miyuki Hino, and Katharine J. Mach. 2019. “The Case for Strategic and Managed Climate Retreat.” Science 365 (6455): 761–763. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax8346.

- Simpson, Nicholas P., Portia Adade Williams, Katharine J. Mach, Lea Berrang-Ford, Robbert Biesbroek, Marjolijn Haasnoot, Alcade C. Segnon, et al. 2023. “Adaptation to compound climate risks: A systematic global stocktake.” iScience 26 (2): 105926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.105926.

- Simpson, Nicholas P., Scott Allan Orr, Salma Sabour, Joanne Clarke, Maya Ishizawa, R. Michael Feener, Christopher Ballard, et al. 2022. “ICSM CHC White Paper II: Impacts, Vulnerability, and Understanding Risks of Climate Change for Culture and Heritage.” Contribution of Impacts Group II to the International Co-sponsored Meeting on Culture, Heritage and Climate Change, Charenton-le-Pont and Paris: ICOMOS & ISCM CHC.

- Tamm, Marek. 2022. “Future-Oriented History.” In Historical Understanding: Past, Present and Future, edited by Zoltán B. Simon and Lars Deile, 131–140. London: Bloomsbury.

- Turner, Sam, Tim Kinnaird, Elif Koparal, Stelios Lekakis, and Christopher Sevara. 2020. “Landscape Archaeology, Sustainability and the Necessity of Change.” World Archaeology 52 (4): 589–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2021.1932565.

- Van de Noort Robert. 2013. Climate Change Archaeology: Building Resilience from Research in the World’s Coastal Wetlands. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Van der Laarse, Rob. 2019. “Europe’s Peat Fire: Intangible Heritage and the Crusades for Identity.” In Dissonant Heritages and Memories in Contemporary Europe, edited by Tuuli Lähdesmäki, Luisa Passerini, Sigrid Kaasik-Krogerus, and Iris van Huis, 79–134. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vince, Gaia. 2022. Nomad Century. How to Survive the Climate Upheaval. Dublin etc: Allan Lane.

- Walsh, Matthew J., Sean O’Neill, Anna Marie Prentiss, Rane Willerslev, Felix Riede, and Peter D. Jordan. 2023. “Ideas with Histories: Traditional Knowledge Evolves.” Arctic 76 (1): 26–47. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic76991.

- Williams, Tracey. 2022. Adrift. The Curious Tale of the Lego Lost at Sea. Lewes: Unicorn.

- Xu, Chi, Timothy A. Kohler, Timothy M. Lenton, Jens-Christian Svenning, and Marten. Scheffer. 2020. “Future of the Human Climate Niche.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 117 (21): 11350–11355. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1910114117.