Abstract

Empirical research on effective assessment feedback often falls short in demonstrating not just what works, but how and why. In this introduction to the special issue, ‘Psychological Perspectives on the Effects and Effectiveness of Assessment Feedback,’ we first synthesize the recommendations from review papers on the topic of feedback published since 2010. In multiple respects this synthesis points to a clear wish among feedback researchers: for feedback research to become more scientific. Here we endorse that view, and propose a framework of research questions that a psychological science of feedback might seek to answer. Yet we—and the authors of the diverse papers in this special issue—also illustrate a wealth of scientific research and methods, and rigorous psychological theory, that already exist to inform understanding of effective feedback. One barrier to scientific progress is that this research and theory is heavily fragmented across disciplinary ‘silos’. The papers in this special issue, which represent disparate traditions of psychological research, provide complementary insights into the problems that rigorous feedback research must surmount. We argue that a cohesive psychological science of feedback requires better dialogue between the diverse subfields, and greater use of psychological methods, measures, and theories for informing evidence-based practice.

There is no shortage of empirical research on the topic of effective feedback in education. Indeed, as a brief search of key academic databases can attest, this already enormous research literature continues to grow rapidly, with hundreds of new feedback papers each year. Researchers have established firmly that the effects of feedback on learning can be highly variable, in some circumstances even deleterious (Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007; Kluger & DeNisi, Citation1996; Wisniewski et al., Citation2019) and that achieving positive effects can involve surmounting numerous cultural, organizational, and psychological obstacles (Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007; Henderson, Phillips, et al., Citation2019). Yet despite thousands of published studies on effective feedback, researchers remain far from comprehensively understanding what causes feedback to be effective. In this special issue on the determinants of effective feedback, we feature four papers from research groups each taking very different empirical approaches to studying feedback processes, but each strongly guided by psychological methods, measures, and theory. In drawing together these different perspectives—and with additional insights from a fascinating commentary paper by Panadero (Citation2023)—we aim to synthesize emerging and complementary themes in the contemporary evidence-base and, broadly, to underscore the importance of psychological approaches for ensuring this evidence-base’s empirical robustness and reliability.

So, where is this vast literature headed? To open this special issue, here we first take a top-level, systematic look at what feedback researchers have argued—since the start of the last decade—are the priorities for moving feedback research forward. For the purposes of this article, we conceptualize feedback as a process rather than always as a product; namely, one “where the learner makes sense of performance-relevant information to promote their learning” (Henderson, Ajjawi et al., Citation2019, p. 17). Informed by our systematic review, we argue that psychological science approaches have a crucial role to play in moving our understanding forward more efficiently, particularly by asking and answering crucial questions about feedback mechanisms, by which we mean the hidden processes that cause or contribute to a measured outcome. We then go on to outline a framework of the types of psychological research questions that we believe a psychological science of feedback should seek to answer about these mechanisms of effective feedback, both when planning and designing research studies, and when interpreting and implementing their findings. Through a highly selective summary of some recent psychological studies that speak to these mechanisms, we highlight the need for feedback science to be cohesive and to promote sharing of evidence between different sub-disciplinary “silos.” To this end, we finish this introduction by outlining the excellent and diverse papers in this special issue.

Studying the effects and effectiveness of feedback

To ask what causes feedback to be effective, one must first consider what it means for feedback to be effective, or to have an effect, and how researchers measure these effects (Henderson, Ajjawi, et al., Citation2019). A common approach is to focus on what people think about the feedback information they receive, or how they describe their reactions to it. In this approach, feedback is typically taken to have been effective when people appraise it positively (e.g., Lizzio & Wilson, Citation2008). Indeed, much educational policy around assessment and feedback relies on learner satisfaction metrics as a principal source of data. In the United Kingdom, for instance, the annual “National Student Survey” is an enormously influential policy tool, wherein undergraduate students indicate their satisfaction by responding on rating scales to statements such as “Feedback on my work has been timely” and “I have received helpful comments on my work” (cf. the Australian “Course Experience Questionnaire”). Despite the influence of such tools, their key advantage as measures of feedback effectiveness is arguably their simplicity, rather than their validity. Indeed, by focusing on learners’ perceptions of the provision of feedback information, rather than on whether learners have been able to use it, such measures may fail to capture any valid indicator of effectiveness (Winstone, Ajjawi, et al., Citation2022).

Assessing the effectiveness of feedback by simply asking learners about their opinions and behaviors can be instructive, and notwithstanding questions over the statistical or consequential validity of quantitative self-report data (see Brown & Zhao, Citation2023, for a detailed treatment of these matters), much of the academic feedback literature takes a self-report approach. Indeed, in a systematic review on students’ engagement with feedback, we found that 55% of empirical studies included self-report survey data, with qualitative accounts gathered from focus groups and interviews included in 23% and 21% of empirical papers, respectively (Winstone et al., Citation2017). But one might reasonably argue that feedback, even if it is liked, and perceived as timely and useful, is not truly effective unless it has an objective impact upon learners’ subsequent outcomes. One common outcome-based approach in feedback research is to examine the extent to which a feedback intervention drives improvements in learners’ grades, or changes in their performance more generally, and research suggests that such improvements following feedback can be apparent even among very young learners (e.g., Fyfe et al., Citation2023). In second-language learning research, for example, a common outcome measure is the “repair rate,” which represents the extent to which learners “correct” aspects of their writing in response to feedback. In one such study, Chinese students “repaired” just 25% of the issues that their peers had identified in their English writing, and were more likely to repair the less-challenging issues than the more-advanced ones (Gao et al., Citation2019; see Aben et al., Citation2022, for similar findings from a study of Dutch students). Outcome-oriented approaches such as these arguably afford more objective indications of the effectiveness of feedback than do self-report data.

Yet even performance-outcome-oriented outcomes do not always equip researchers to understand why or how feedback is effective, and may even fail to detect important effects. As Henderson, Ajjawi et al. (Citation2019, p. 25) have argued,

subsequent performance may not actually represent the particular effect(s) of the feedback process that it is meant to be evidencing […] there may be a variety of effects arising from the initial feedback process that are not evident in the subsequent performance […] because the effect is harder to observe, such as emotional, motivational, relational or other changes.

Like Henderson and colleagues, we worry that assessing the effectiveness of feedback based solely on its subsequent effects on performance can only provide a partial understanding of the issues. Even more informative, in principle, are studies designed to shed light on the cognitive, motivational, interpersonal, affective, and even physiological impacts of receiving feedback (e.g., goal-setting, rapport-building, anxiety, or attention, to give just a few examples), and on how these processes affect the type or quality of feedback information that is given in the first place. In this special issue, for instance, Kent Harber (Citation2023) evaluates various social mechanisms that could explain why racially minoritized learners sometimes receive insufficient constructive critique from White instructors. In broad terms, psychological mechanisms represent the means by which giving and receiving feedback drives changes in behavior and performance, and understanding these mechanisms is critical to effectively theorizing and predicting the effectiveness of feedback. But many empirical studies on the effects of assessment feedback offer little insight into mechanism, and many are poorly theorized (Winstone et al., Citation2017). Moreover, despite a wealth of psychological theory that could provide a foundation for understanding feedback effects (e.g., Fong & Schallert, Citation2023, discuss how socio-emotional and socio-motivational theories can inform understanding of feedback), many theoretical models of feedback are purely descriptive. That is to say, they provide heuristic value and an intuitive sense of validity without necessarily holding explanatory or predictive power (see Panadero & Lipnevich, Citation2022 for an excellent and comprehensive overview).

Feedback researchers’ recommendations for feedback research

The net effect of the limitations described in the previous section (i.e., the lack of insight into feedback mechanisms, the poor theorizing of feedback, the largely descriptive nature of existing feedback theory) is clear: educational research has far more empirical data about what supposedly works in making feedback effective, than explanations of how and why it works (and by extension, for whom and under which circumstances). That said, one of the most notable trends in the recent feedback literature has been a shift away from studying merely the delivery or transmission of feedback to learners, and toward studying how this feedback is received and used (Panadero & Lipnevich, Citation2022; Winstone et al., Citation2022). An important corollary of this shift is the assumption that the effectiveness of feedback processes should be measured by their impact on learners. To what extent has this shift in focus been accompanied by heightened research interest in measuring and explaining the causes of feedback’s effectiveness, and by concomitant calls for fundamentally different feedback research? To begin answering these questions, we systematically examined review papers on feedback published since the start of the last decade, seeking to synthesize what their authors saw as key priorities and recommendations for future research. Whereas synthesizing recommendations in this way has some precedence in the field of medicine (e.g., Pirosca et al., Citation2020), it appears to be novel as a methodology within educational research. Doing so serves two broad aims: it offers a snapshot of the contemporary feedback literature, and it provides a preview of how the literature may continue to develop. With these as our aims, it was most relevant for us to review only relatively recent literature, and therefore we opted to synthesize the recommendations of papers published since 2010.

Method

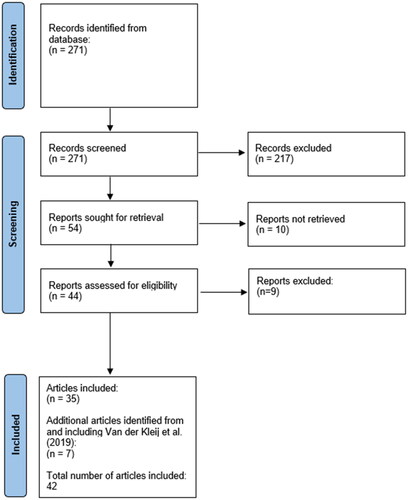

In late 2021 we used the electronic database Scopus to identify all English-language journal articles published since 2010 that were classified under document type as a “Review,” contained the word “feedback” in the paper title, and contained at least one of the word-stems “educat*,” “teach*,” “learn*,” or “student*” in the title, abstract, or keywords. The “Review” document type in Scopus includes narrative and systematic reviews, as well as meta-analyses and other evidence syntheses. As shows, these initial search criteria obtained 271 hits, for each of which we examined the title and abstract to evaluate whether they met four further inclusion/exclusion criteria: (1) they focused on the giving and/or receiving of feedback; (2) they focused on feedback as given by an educator, rather than by a peer, computer/automated feedback, or self-feedback; (3) they did not focus on motor feedback; (4) they focused on domain-general rather than domain-specific skills and effects. We assessed criterion (4) based on the title and abstract alone, and did not take into consideration the journal in which the paper was published. Work excluded under this criterion included papers on the effects of feedback on surgical skills in operating theaters, or in otolaryngological training. The rationale for excluding such articles was that the recommendations in these papers were typically focused on improving techniques or practices unique to those specialist fields, rather than recommendations for developing understanding of feedback processes per se.

By assessing these criteria based on the titles and abstracts, we excluded 217 papers, leaving 54 for which we attempted to download the full-text. For those papers we could access (n = 44), we read the Discussion section or equivalent, and applied one further exclusion criterion: papers were excluded if they contained no specific recommendations for future research beyond merely calling for further research. This final criterion removed another 9 papers (in itself a noteworthy finding), leaving 35 for inclusion in this review.

We observed that our initial search process had omitted some key recent review papers, in particular van der Kleij et al.’s (Citation2019) meta-review of students’ role in feedback processes. To enhance the breadth and completeness of our review, we therefore scrutinized all of the review papers synthesized by van der Kleij et al. (Citation2019), determining which were not captured by our main search yet would also meet our criteria. Doing so led to us adding six additional papers to our review, plus van der Kleij et al. (Citation2019) itself, for a total of 42 papers.

For each of the 42 papers, we extracted from the Discussion section (or equivalent) every section of text that offered an explicit or implicit recommendation for future research. We collated these extracts and, using an inductive coding process, the first author identified common thematic clusters of recommendations, and attempted to classify every extract into one or more of these clusters. Subsequently, the second author inspected the first round of coding, highlighted disagreements, and all disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Findings

Our analysis led us to identify 12 clusters or themes, plus an “Other” cluster that we do not discuss further, but which primarily captured recommendations unrelated to feedback or that were specific to a paper’s discipline of applied interest. For each of the 42 papers, we judged whether or not each cluster featured amongst its recommendations, as summarized in . Here we briefly describe these main clusters, but we focus our analysis primarily on the first seven, which we believe are most illuminating in terms of the directions that have been recommended for this literature.

Table 1. List of review papers included in our synthesis, detailing which of the clusters of recommendation-types featured within each paper.

Psychological mechanisms

Of particular interest given our focus upon explanatory accounts of feedback effects, several of these papers’ recommendations highlighted the need to understand psychological mechanisms that cause, or contribute to, the effects and effectiveness of feedback. Nevertheless, there were disappointingly few such calls, and even where they were made, broad observations about the lack of understanding of mechanism were rarely supplemented by specific reasoning about what remedies are needed:

We need a more in-depth understanding of the intermediate steps that explain how an initial intention to seek feedback may eventually lead to better performance. To date, virtually no theory with which to open this ‘black box’ has emerged in the literature on feedback-seeking behaviour. (Crommelinck & Anseel, Citation2013, p. 236)

A question that still deserves further investigation is what are the processes occurring between feedback reception, feedback acceptance, and the eventual subsequent changes. (Gabelica et al., Citation2012, p. 141)

Several authors pointed to mechanisms they felt needed further study in the context of their particular research questions, although these recommendations frequently alluded only to general varieties of mechanism (e.g., “cognitive processes,” “emotional responses,” “social development,” “attentional focus”), rather than pointing to specific questions that merited investigation. One notable exception was Fyfe and Brown (Citation2018), whose discussion of the effects of feedback on children’s mathematical reasoning (developed further by Fyfe et al., Citation2023) offered several specific recommendations targeted toward examining psychological mechanisms.

Quality and rigor

Over one-third of these papers raised concerns around the quality and rigor of the evidence that exists in this literature, or about the extent to which the existing data can support valid claims:

A large range of possible moderators have been proposed, yet for the vast majority one reasonable conclusion is that the evidence is quite minimal in terms of quantity and/or strength. (Winstone et al., Citation2017, p. 22)

Whereas these concerns were often nonspecific or global, many did point to specific difficulties. For instance, several authors noted the low statistical power of many quantitative studies due to small sample sizes, and the use of unvalidated or unreliable measurement instruments (for a detailed treatment of this problem see Brown & Zhao, Citation2023). Others alluded to the common tendency to draw strong conclusions from single studies, and failures to consider or control for obvious confounds in study designs:

Many of the included studies were ‘one-off’, involved small numbers of participants and included sources of bias. This indicates the need for studies that involve more participants and are methodologically better designed and executed. (Johnson et al., Citation2020, p. 20)

the assessments used in most experiments contained very few items. In order to measure student learning with sufficient reliability, the number of items in the post-test should be satisfactory. Using high-quality instruments makes it possible to measure with high precision. (van der Kleij et al., Citation2011, p. 33)

Although blinding learners and teachers to educational interventions is often not feasible, we believe studies of feedback interventions could […] at least control for potential confounding factors. (Bing-You et al., Citation2017, p. 1351)

It was striking that several papers also noted a tendency for publications to provide insufficient methodological detail to afford effective replication or validation—or indeed even comprehension—of their findings:

we note a need for more detailed reporting of feedback interventions, with rich descriptions of the different components and rationale for their combination, in order to share experiences, build theory or synthesise evidence across studies. (Mattick et al., Citation2019, p. 364)

when preparing manuscripts, a detailed description of the sample, context, and procedures should be presented so that researchers, practitioners, and policy makers could judge whether the findings may or may not help them to answer specific questions or solve problems at hand. (van der Kleij & Lipnevich, Citation2021, pp. 368–369)

Finally, multiple author groups commented on inconsistencies in defining and operationalizing constructs, which cause difficulties in comparing and synthesizing evidence across studies:

we recommend to define, describe, and operationalize terms … in a more precisely [sic] manner. This allows researchers and practitioners to better understand the meaning of these terms and from there on use them, either in empirical or review studies as well as in classrooms. (Thurlings et al., Citation2013, p. 13)

This challenge faced by feedback researchers due to imprecise and divergent terminology was recently discussed by Panadero and Lipnevich (Citation2022) with reference to the so-called “jingle-jangle fallacies,” where different concepts are sometimes referred to using the same term, and different terms are sometimes used to refer to the same concept. As Block (Citation1995) argued, this imprecision “waste[s] scientific time… Together, these errors work to prevent the recognition of correspondences that could help build cumulative knowledge” (p. 210). In sum, these authors’ observations point to specific ways in which feedback researchers perceive the current literature as lacking in its capacity to afford robust, evidence-based claims. These points should be of concern to feedback researchers, but should also stimulate change.

Generalizability across settings, domains, populations, and cultures

Many of these reviews stressed the importance of establishing how well findings translate from the laboratory to the real-world, or from specific studied contexts to other, unstudied contexts. These papers identified several examples of such contexts across which findings may not be guaranteed to translate:

It would be necessary to conduct studies in more diverse settings, involving multiple disciplines at multiple institutions to make the findings more generalizable. (Hayes et al., Citation2017, p. 322)

in the data set, there was a lack of studies that investigated […] the learning of languages other than English. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution. (Li, Citation2010, p. 342)

Comparing across cultures, developmental levels and academic domains may greatly inform the field and allow for more nuanced understanding of student views on feedback and how these might relate to scholastic achievement outcomes. (Van der Kleij & Lipnevich, Citation2021, p. 369)

The above extracts are especially salient insofar that they raise questions about the cultural generalizability of feedback findings, given that most published feedback research has been conducted in Western cultures. Other authors shared similar concerns:

race and ethnicity have been found in previous research to moderate the effect of criticism on motivation […]. There is reason to believe that the effect of negative feedback may vary across cultures due to the greater value for effort over ability in more collectivist cultures. (Fong et al., Citation2019, pp. 155–156)

The question posed at this juncture is whether our western value and understanding of feedback can, or indeed is, relevant for other cultures? Exploration of this question […] necessitates further research. (Ossenberg et al., Citation2019, p. 396)

communication is becoming more and more intercultural because it involves participants who have different first languages and represent different cultures. The language and cultural backgrounds of learners influence the choices they make. […] More research into such issues can equip learners and teachers with language and intercultural communication skills to thrive in today’s diverse society. (Yousefi & Nassaji, Citation2021, p. 8)

Taken together, these authors’ arguments highlight the importance of exploring feedback effects in different populations and seeking to investigate effects across different participant groups.

Theoretical and conceptual grounding

A recurrent theme among these papers was a concern that much feedback research is atheoretical, with a severe lack of coherent explanatory frameworks that generate testable and falsifiable hypotheses:

The narrative synthesis is also limited by the lack of theoretical grounding in many of the primary studies, leading us to rely on inferences with respect to explanatory theories. (Hatala et al., Citation2014, p. 268)

Among the many intervention studies reviewed here, we frequently observed instances in which the authors gave no explicit theoretical account of how their endeavors might influence learners’ cognition or behavior. (Winstone et al., Citation2017, p. 34)

Whereas there was some clear consensus that theory in this field is lacking, little was suggested by way of remedies. Some author groups recommended specific theories, or broad theoretical approaches, that they felt should receive further attention, such as “socioconstructivist perspectives,” “cognitive load theory,” and “the Hattie and Timperley (Citation2007) model.” However, whereas some authors called for the application of specific theoretical orientations, they did not typically specify why or for what purpose. A small number specifically recommended a turn to psychology for valuable theory that would guide investigations and explain findings: an approach strongly endorsed by Fong and Schallert (Citation2023), who highlight several social psychological theories that offer exactly this kind of promise.

These observations align with those of a recent review on the use of theory in feedback research, whose authors demonstrated that only 37.5% of assessment and feedback papers that were published in key journals in 2020 engaged with educational theory (Nieminen et al., Citation2023). The authors called for engagement with a broader range of theories, as a way to “un-silo” the field and connect feedback research with other scientific domains, and to “protect researchers from reinventing the wheel” (p. 11). We return to these important points later.

Research methods and designs

The authors of these papers frequently commented on the kinds of studies that are needed in future, in terms of the research methods and designs that would be most beneficial. Two clear messages emerged from these recommendations. The first was a call for more widespread use of experimental methods and randomized trials, as a means to better answer questions about and to support stronger claims about the causality of observed effects (see also Gopalan et al., Citation2020):

Although a difficult area to research, more randomised controlled studies on a change in behaviour following feedback […] should be encouraged. (Saedon et al., Citation2012, p. 7)

To advance this field of knowledge, research programmes designed to systematically investigate the constituents required for effective feedback are needed. This is likely to involve a series of studies designed to isolate one factor at a time, with all other key influences on performance standardised. (Johnson et al., Citation2020, p. 20)

Numerous programs of psychological feedback research already embody the approach that Johnson et al. (Citation2020) recommended, whereby successive experiments systematically test, rule out, and support competing mechanistic explanations of an observed effect. Harber’s (Citation2023) paper illustrates one such experimental research program, and it is clear from the present review that there is a strong appetite for more of this type of work.

The second clear message from this cluster is that beyond the value of (quasi-)experimental methods, in fact the field would benefit from a much greater diversity of research methods. Authors of these papers recommended that certain research questions invite more qualitative work (e.g., Agius & Wilkinson, Citation2014), or more quantitative work (e.g., Bing-You et al., Citation2017), or mixed-methods work (e.g., Mattick et al., Citation2019), but some authors also specifically recommended greater use of psycholinguistic methods (e.g., Van der Kleij & Lipnevich, Citation2021), cognitive and neuroimaging/neurophysiological methods (e.g., Dion & Restrepo, Citation2016; Luft, Citation2014), well-validated survey research (Van der Kleij & Lipnevich, Citation2021), observational studies (Lyster et al., Citation2013; Thurlings et al., Citation2013), interview studies (e.g., Mattick et al., Citation2019), evidence syntheses and systematic reviews (e.g., Bing-You et al., Citation2017). In short, whereas there was a clear call for experimental approaches, there was equally a perception that a strong literature is one that accumulates evidence from diverse research designs.

Outcome variables and measures

Beyond recommending particular kinds of research methods, many of these author groups also invited further thought about outcome variables that would be more illuminating than those used most frequently at present. One of the most salient perspectives, noted by several author groups, is that feedback researchers have spent a lot of time assessing what learners say and think about feedback, but much less time directly measuring what learners actually do when receiving, engaging with, and acting upon feedback. These authors thus called for a more widespread use of behavioral outcome measures:

Fifteen of the 16 studies described self-reported rather than measured changes in behaviour. While self-reported measures of change in behaviour are highlighted as being quicker and easier than measuring actual behaviours, it is argued that healthcare systems are not concerned with changing health professionals self-reported behaviour, rather they want to change actual behaviour. (Ferguson et al., Citation2014, p. 9)

Most studies rely almost solely on students’ statements. Consequently, there is a major call for future research where students’ strategies for using feedback are investigated in vivo. (Jonsson, Citation2013, p. 71)

Clearly, it would be valuable to focus more on how learners actually behave when receiving feedback rather than principally on how they claim they behave. (Winstone et al., Citation2017, p. 32)

Authors also pointed to ways in which better outcome measures would afford more robust claims about the evidence gathered, such as through the inclusion of baseline measures, and the careful validation of psychometric scales and other survey instruments (Brown & Zhao, Citation2023). And just as the author groups in our review had recommended a greater diversity of research methods, many groups also recommended greater diversity in the kinds of outcome measures researchers should strive to collect, pointing for example to the potential informativeness of eye-tracking measures, fMRI, memory tests, emotion measures, and so forth. Agius and Wilkinson (Citation2014) did, however, note one potential disadvantage of such diversity, in that “The multiplicity of instruments used to measure feedback creates difficulties in comparing findings” (p. 558). Nevertheless, greater methodological diversity is likely to facilitate renewed focus on the behavioral impacts of feedback information.

Longevity and transfer of effects

In many cases, authors commented on the limited research evidence establishing the longevity of feedback effects:

However, we need to know about learning that endures months or even years later. (Fyfe & Brown, Citation2018, p. 174)

In addition, only one study looked at the change in behaviour over time, and in that study the follow-up was only five months. Therefore, it is not known whether the changes made are sustained over a longer period of time. (Ferguson et al., Citation2014, p. 10)

Beyond querying the durability of effects, these papers also noted other important questions that might necessitate longitudinal studies. First, as Fyfe et al. (Citation2023) also observe in their review of developmental research within this special issue, relatively little is known about transfer effects: that is to say, how and when the benefits of receiving feedback on one task might transfer to a different task or different situation:

The sociocultural and situated nature of learning is important in this respect and requires more research attention to establish how, in various situations, feedback can be transferred from one context to another. (Evans, Citation2013, p. 106)

It was also emphasized that longitudinal studies can sometimes uncover important effects that go unnoticed in short-term or cross-sectional studies:

Finally, it is important to examine learning effects using delayed retention tests, as what appear to be weaker immediate learning gains can translate into better long-term learning outcomes. (Hatala et al., Citation2014, p. 269)

it might be that certain feedback types and characteristics play a more prominent role at the beginning of a team experience when the team is formed and still needs to discover team requirements, challenges, and opportunities, while being less powerful at a later stage. (Gabelica et al., Citation2012, p. 141)

Whereas conducting high quality longitudinal studies is certainly challenging, gaining a detailed understanding of the mechanisms underpinning effective feedback is often likely to require elucidation of these longer-term details.

Contextual variables

Around half of the papers called for better understanding of contextual factors that determine the effects or effectiveness of feedback. In most cases, the authors of these papers pointed to specific contextual variables of interest. These included looking at how feedback operates across different tasks and forms of assessment (e.g., Li, Citation2010), and different instructional settings and organizational environments (e.g., Lyster et al., Citation2013; Ossenberg et al., Citation2019), and in particular the role that an organization’s “feedback culture” might play (e.g., Bing-You et al., Citation2017). Several researchers proposed more research to consider the role of interpersonal relationships between the feedback giver and receiver (e.g., Paterson et al., Citation2020; Yu et al., Citation2018).

Individual difference variables

Similarly, more than one-third of the papers recommended better understanding of individual-level factors that might moderate the effects or effectiveness of feedback. The list of proposed variables was long, but included (a) demographic variables such as age, gender, and culture, (b) socio-motivational variables such as self-esteem, values, volition, and “willingness to communicate,” and (c) academic variables such as level of knowledge or proficiency, and approaches to learning. Fyfe et al. (Citation2023) note evidence that a learner’s level of knowledge, in particular, may indeed be an important moderator variable even from an early age.

Aspects of the provision of feedback

One of the most common kinds of recommendations among these reviews was for more research that seeks to answer questions about the process of providing feedback, such as the effects of the mode or timing of delivery (e.g., Lyster et al., Citation2013), type of feedback (e.g., positive vs. negative; Hatala et al., Citation2014), and the tone or format of the feedback information (e.g., Swart et al., Citation2019). These kinds of recommendations were somewhat more frequent than were recommendations about the receiving of feedback, which is unsurprising given that educators’ focus has historically been—and continues to be—primarily on the responsibility of the feedback-giver in feedback processes (Winstone et al., Citation2022). Whereas we will not enumerate the many diverse proposals in this cluster, one recurrent theme stood out: the role of skill and experience in giving effective feedback:

Priority in both the empirical and non-empirical literature is given to providing a detailed understanding of attributes pertaining to the skills needed to give feedback. (‘skilful interactions’) (Ossenberg et al., Citation2019, p. 397)

It would be interesting to understand how highly experienced mentors, or those who know the individual feedback recipient, implicitly tailor their feedback. (Mattick et al., Citation2019, p. 365)

This kind of skill in feedback-giving is especially pertinent to some of the challenges raised by Harber (Citation2023), who asks to what extent training interventions could effectively debias the feedback that instructors give to racially minoritized learners.

Aspects of the receiving of feedback

These papers highlighted diverse factors whose effects upon learners’ receiving of feedback should be explored, which again we will not enumerate, but which included managing affect, individual receptivity to criticism, and the feedback receiver’s beliefs about and perceptions of the feedback giver and the feedback process. In general terms, many author groups emphasized the need for greater understanding of how feedback is received, appraised, and applied. For example, researchers argued that:

There is a great need for empirical research into how students take action based on feedback. (van der Kleij & Lipnevich, Citation2021, p. 367)

calls for continued research investigating the ways in which students appreciate, judge, and manage their affect before taking action are echoed by the current review. (Haughney et al., Citation2020, p. 8)

Such research is likely to require some of the varied methodological approaches outlined above.

Effectiveness and impact upon real-world outcomes

Finally, the most frequent cluster of recommendations, noted in 31 of the 42 papers, involved calls for more information on “what works” in terms of how feedback can transform real-world consequential outcomes such as learners’ performance, skills, goal-attainment, and clinical care (e.g., Crommelinck & Anseel, Citation2013; Gabelica et al., Citation2012). These papers also called for better understanding of factors that constrain the likelihood of these positive outcomes (e.g., Li, Citation2010). Their recommendations rarely contained additional insights into broad directions for the literature; but it is significant nonetheless—even if unsurprising—to document the consensus that understanding the impact of feedback is a key priority for future research.

A psychological science of effective feedback

Our synthesis points to numerous diverging priorities for the future of feedback research, as one would reasonably expect for a field of research with such a rich, multidisciplinary history. But it also highlights distinct converging themes among these priorities. Notably, these papers called for a greater prominence of explanatory frameworks and theoretical reasoning in feedback research. They called for more rigorous, careful measurement of informative outcome variables, and called particularly for the empirical study of genuine behaviors rather than only opinions and beliefs. They called for the more frequent use of research methods that afford causal inferences, and that account for confounds. They called for understanding the generalizability of effects across diverse contexts, and of their longevity. And in some cases, at least in general terms, they called for understanding the mechanisms behind observed effects, rather than merely observing the effects themselves. In all of these respects, we conclude that feedback researchers wish for feedback research to become more scientific.

As psychological scientists, we wholeheartedly agree. We believe there is a clear space—indeed, a clear need—to forge a feedback science that moves the massive feedback literature forward in ways that engage pragmatically with its current limitations, and we elaborate on this point in the remainder of this paper. But because we saw relatively few specific calls to understand the mechanisms underlying effective feedback, we also wonder whether feedback researchers are yet asking all of the “right” questions. Indeed, the literature contains countless interesting demonstrations of apparently effective feedback interventions, but it is only through understanding their mechanisms that scientists can form and test predictions about whether the effects would replicate—especially in different contexts or different populations—, how to maximize them, and how to prevent negative side-effects.

Psychological mechanisms are frequently characterized in this literature as a “black box,”,” with feedback as an input, behavior as an output, and mysterious processes occurring in-between that are poorly understood (Lui & Andrade, Citation2022). Among the key goals of a psychological science of feedback should be to elucidate what goes on inside this black box, or as Lui and Andrade (Citation2022) put it, to “increase our understanding of what happens in the minds and hearts of students as they process feedback and assessment information” (p. 11). Doing so, we believe, involves not only enumerating the psychological processes that happen inside the “black box,” but also asking and testing meaningful research questions about these hidden processes: questions that afford rigorous measurement and falsifiable hypotheses.

Which questions should researchers be asking?

In Winstone et al. (Citation2017), we argued that feedback researchers and practitioners have frequently been too ready to implement feedback interventions without a clear articulation of how or why they might change learners’ behavior. We argued that having a clear, theoretically informed conception of the skills that any given intervention targets should be fundamental to how the intervention is designed, and equally importantly, to how its effectiveness is measured and evaluated. Building upon those earlier arguments, here we extend our focus to argue that scientific efforts to examine the effectiveness of feedback should involve questioning which psychological processes are implicated in that effect. For example, an increasing area of interest in feedback research is the concept of “feedback literacy,” the skills and capacities that support effective use of feedback (see Carless & Boud, Citation2018). Whereas the growing literature proposes that these feedback literacy skills should enable learners to make better use of feedback, there is limited evidence directly testing this assertion, or for seeking to understand how and why these capacities might influence behavior.

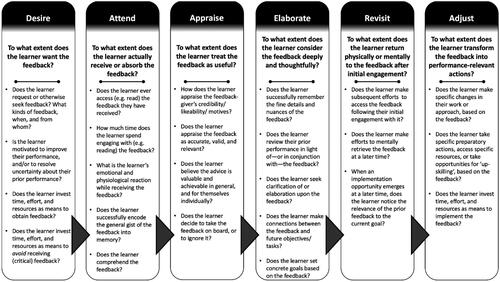

outlines a new descriptive framework of six phases of learners’ engagement with feedback, and it proposes a nonexhaustive list of questions that researchers might ask when attempting to explain why feedback might have—or did have—an effect on learners’ performance or outcomes. Considering some or all of these questions would position researchers to design and implement informative empirical evaluations of educational feedback interventions. That is to say, by considering carefully the possible psychological processes via which any putative feedback effect might work, researchers can make better decisions about behavioral measures to include in their evaluations, that would be more informative and provide greater explanatory power than would only assessing self-reports, or even changes in grades.

Figure 2. Descriptive framework of research questions to ask about mechanisms involved in feedback effects.

Before we unpack and illustrate this framework, let us first challenge a critical assumption about the existing research literature on feedback. Specifically, based on our synthesis of feedback researchers’ recommendations, one might reasonably conclude that a psychological science of feedback does not currently exist: that there is a dearth of theory-driven behavioral research for informing scientific understanding of feedback processes. Indeed, as we have noted above, our own prior systematic review on learners’ engagement with feedback revealed a heavy reliance on self-report methods, almost no use of (quasi-)experimental methods, and a research base that “remains highly fragmented and somewhat atheoretical” (Winstone et al., Citation2017, p. 31). Why is there so little behavioral science research—particularly experimental research—on feedback?

In fact, there is a great deal such research, dating back several decades. We illustrate some more-recent examples below, and indeed, the papers in this special issue cover several well-developed areas of behavioral—and in some cases experimental—feedback research. Yet it is common, and understandable, that reviews of assessment feedback tend to focus selectively on research conducted within pedagogic contexts. For instance, in our own systematic review we only included research that “discussed summative or formative feedback given in the context of education at any level, rather than in other contexts such as employment” (Winstone et al., Citation2017, p. 19). It seems clear that this criterion—necessary as a means of managing the scope of the review—was in part responsible for the exclusion of much relevant psychological evidence from other applied and non-applied contexts. In this way, we therefore propose that the recommendations of the 42 papers synthesized above—and indeed our own prior characterization of the feedback literature (Winstone et al., Citation2017)—under-represent an abundance of strong, scientific, and theory-driven work that is clearly relevant to feedback researchers: arguably including some of the most exciting and informative feedback research that exists. To demonstrate this point, we return to to consider the various “black box” processes that researchers might seek to understand and measure, highlighting psychologically informed studies that can already shed light on these processes.

Desire

Feedback is not always wanted, and psychological processes can therefore determine whether feedback even occurs. Two of the papers in our synthesis focused on feedback seeking (Anseel, Citation2017; Crommelinck & Anseel, Citation2013), a process often omitted from “black box” conceptions of feedback, but nevertheless reliant upon social psychological dynamics such as the anticipation of bias or prejudice (see Harber, Citation2023), and upon learners’ metacognitive appraisals of their understanding and skills (see Brown and Zhao, Citation2023). Yet as Cutumisu and Schwartz (Citation2018) pointed out, most feedback research looks only at feedback that is assigned to learners, rather than feedback that learners opt to receive. Those authors’ data suggest that the extent to which learners proactively choose to receive negative feedback is positively associated with the extent to which they revise their work, and with the quality of their final work (e.g., Cutumisu et al., Citation2015). Other behavioral research shows that people are more likely to request (and respond to) negative feedback when they perceive themselves as having expertise in a domain, even regardless of their actual expertise (Finkelstein & Fishbach, Citation2012).

Existing psychological research and theory can elucidate what feedback information people actively seek out, and when. It can also elucidate when people might avoid receiving valuable advice or information. For instance, in one of our favorite research programmes, university undergraduates were more willing to learn their risk of contracting an unfamiliar disease when they had been told that the potential obligations of contracting the disease were low (i.e., a short course of medication), rather than high (i.e., lifetime adherence to medication; Howell and Shepperd, Citation2013a). This so-called information avoidance has been studied more extensively in health psychology—where avoiding advice can be a matter of life and death—than in education. Yet the concept’s relevance to educators is plain to see, and behavioral research can point toward how avoidance might be mitigated. For example, students in similar studies were less likely to avoid the results of a health screening if they first affirmed their own self-worth, or if they were prompted to reflect on why they might avoid the information and why they might prefer to know it (Howell & Shepperd, Citation2012, Citation2013b).

Attend

Even the best, most constructive feedback can only be effective if the intended receiver receives and notices it in the first place, investing sufficient cognitive effort that the information has a hope of being absorbed. Understanding the mechanisms of attending to feedback, therefore, demands the study of cognitive processes, particularly attention and short-term memory, and studying how people intuitively react to feedback information, for example by measuring their immediate emotional and physiological responses. In one series of studies, we asked students to complete a persuasive writing exercise, and we later gave them generic written feedback comments that were ostensibly based on their own work. At random, some of those comments were written in an evaluative style (e.g., “You didn’t always demonstrate a sophisticated awareness of the issues”) and some in a directive style (e.g., “You should aim to demonstrate a more sophisticated awareness of the issues”; Nash et al., Citation2018). Shortly afterwards, we tested participants’ ability to recall the comments. Recall was poor, even after only a few minutes; but counterintuitively, participants were significantly more likely to recall comments that had been given in an evaluative style than those in a directive style, even though they paid equal attention to both kinds of feedback while reading (Gregory et al., Citation2020).

Research approaches and findings such as these can be valuable in understanding how cognitive factors determine the initial impact of a feedback message or intervention. Whereas at present there is a relative paucity of feedback research using memory measures such as ours, the use of eye-tracking and similar attentional techniques is growing, and there is likewise a real opportunity for researchers to capitalize upon psychological research methods that provide real-time physiological insights (see Timms et al., Citation2016 for an overview, and for one preliminary—albeit unsuccessful—attempt to gather galvanic skin response data to this end). More prevalent use of physiological measures in particular would be valuable for empirically testing theoretical accounts of emotional responses to feedback, which as Fong and Schallert (Citation2023) discuss, often afford conflicting predictions or explanations of effects.

Appraise

Assuming that a student notices and attends to their feedback, this does not guarantee they will accept it or treat it as acceptable. This receptiveness to feedback is likely influenced by a variety of socioemotional, sociocultural, and individual difference factors, which determine people’s likelihood of treating the feedback message as valid and achievable, treating the feedback sender as credible, and so forth (Brown & Zhao, Citation2023). For instance, just as self-affirming one’s own worth can play a role in people’s willingness to receive feedback, as described above, experimental evidence suggests that it can also shape people’s perceptions of the credibility and validity of critical feedback (e.g., Toma & Hancock, Citation2013). Such studies highlight that people appraise feedback information through the lens of how they perceive themselves and others, and that understanding this social psychological context is critical to how we understand effective feedback. Social psychologists have amassed a wealth of evidence on how people’s self-motives shape their willingness to accept critical information about themselves (cf. Hepper & Sedikides, Citation2012), and yet this large literature appears to have had relatively minimal explicit impact upon theory and understanding in educational feedback research.

In considering these appraisals of feedback, a consequence is that people will sometimes choose consciously to disregard advice they receive. In Wu and Schunn’s (Citation2021) recent work, secondary school students who received peer-feedback on a written assessment actively decided to ignore almost one-quarter of the “fixable” comments they received. Moreover, these decisions predicted the students’ actual behavior—when they intended to “fix” a problem, there was evidence of an actual fix in their revised assessment in 85% of cases, as compared with just 43% of the comments that students intended to ignore. Studies like Wu and Schunn’s nicely illustrate how gathering additional psychological measures can provide more informative insights than does solely looking at changes in students’ performance before vs. after feedback.

Elaborate

Feedback does not always simply tell recipients exactly what to do; people are rarely expected to implement advice without thought or question. Rather, feedback receivers must actively make sense of feedback, deeply contemplating the actions they need to take and the skills and resources they require to this end. To ensure that feedback “sticks” in memory over time, the receiver must also engage in deeper cognitive processing of the information beyond its initial attention-based encoding. And to realize its impact, learners may need to review their prior performance, seek opportunities to discuss and clarify the feedback, and set goals (Winstone et al., Citation2017).

Once again, these kinds of elaborative behaviors can be understood in terms of psychological mechanisms. In one fascinating set of studies, German university students completed a task that involved them learning novel Swedish—German word pairs (Abel & Bäuml, Citation2020). Next, they were given opportunities to improve their learning: at random, some students were asked to simply restudy the word-pairs, whereas others were asked to try to produce the German word based on each Swedish cue alone, and then they received corrective feedback. Importantly, once participants believed the study was over, they were left alone for five minutes. During this period, participants were offered some magazines to browse, and also left with the Swedish word-learning materials and some educational information about Sweden. The researchers found that not only did the retrieval-and-feedback approach improve students’ test performance—relative to merely restudying the word-pairs—but impressively, those in the retrieval-and-feedback group subsequently spent more time browsing the educational materials of their own volition. Findings like these provide insights into the mechanisms behind the benefits of corrective feedback that researchers like Fyfe et al. (Citation2023) have observed. Specifically, such findings suggest that corrective feedback can sometimes enhance learning not just because it provides the correct answers, but also because it motivates learners to reengage with the learned material itself.

Revisit

It is well established that even those learners who initially attend to and engage with the written feedback they receive rarely return to review their feedback on subsequent occasions (e.g., Robinson et al., Citation2013). And whereas not all feedback takes a written format, one might reasonably ask to what extent learners tend to revisit their feedback—either physically or mentally—when a future opportunity arises for them to apply it. That is to say, except in the rare cases where feedback can be implemented immediately upon receiving it, being able to use feedback effectively will typically involve the receiver proactively casting their mind back to it when it becomes relevant in future, and actively realizing its relevance to the current goal or task. This complex task involves higher-level cognitive processes, such as reasoning and abstraction skills that afford the capacity to make connections between a current task and information received in the past. It also, notably, relies on prospective memory—the ability to remember to carry out intentions at a later time—on which a vast psychological literature exists but has been drawn upon minimally by feedback researchers.

Research shows, for instance, that people typically exhibit more-successful prospective memory in tasks with event-based cues (i.e., remembering to do something when a particular event happens, or when a particular cue appears) than in tasks with time-based cues (i.e., remembering to do something at a particular time; see e.g., Sellen et al., Citation1997). Likewise, people exhibit more successful prospective memory when they have actively formed and visualized specific intentions about the circumstances in which they will enact an intention (see e.g., Gollwitzer, Citation1999). From these kinds of theory-driven psychological research, one can clearly appreciate why even the most well-intentioned learners who receive helpful advice might nonetheless fail to act upon that advice. And likewise, from such research one can envisage evidence-based interventions that might mitigate these cognitive failures. Based on the relative scarcity of research on these topics, we speculate that this “revisiting” process is the least understood of all the processes that underlie effective feedback. The process of mentally and physically revisiting feedback is, without doubt, an arena ripe with opportunities for further research.

Adjust

Finally, making feedback effective involves the recipient taking action, by taking goal-compatible preparatory steps, and adjusting their behavior in ways that follow from the advice they received. As we noted above, in the education literature the impact of feedback has often been indexed by self-reports or changes in grades, but adjustment can also take countless other forms. Fyfe et al. (Citation2023) demonstrate, for example, how developmental psychologists have assessed children’s changing ability to solve reasoning problems, or to fluently produce written outputs, following corrective feedback. In this way, psychology illuminates a great deal about the circumstances in which people do and do not change their behavior in response to advice or correction. Another fascinating line of behavioral work, for instance, shows that people’s tendency to act upon advice depends on how much they have invested in receiving that advice (Gino, Citation2008). In that work, undergraduate participants tried to win money by answering quiz questions, and they had an opportunity to seek advice on the answers to the questions. Unsurprisingly, participants were much more likely to seek advice when it was “free” (advice sought 95% of the time) than when seeking advice came at a financial cost (56% of the time). But more importantly, participants enacted the feedback—by changing their provisional answers—to a greater extent when it had been costly, than when it had been free. Studies like this provide insights into the psychological mechanisms that can underpin the actual use of feedback to adjust behavior.

Applying the framework

Our descriptive framework in is exactly that: a framework. Like many of the “theoretical models” in the literature, it affords no specific theoretical predictions. But it does highlight questions that might be productively asked about a feedback intervention or effect with an eye to considering its mechanisms, and it provides a means of conceptually organizing these questions. We contend that this framework can guide feedback research regardless of the type of learner (e.g., K-12 or College Education) or feedback modality (e.g., written feedback or verbal feedback; audio, video, or screencast feedback).

To illustrate this framework with an example, consider a recent interesting study by Hattie et al. (Citation2021), who quantitatively analyzed the formative feedback comments received on draft assignments by over 3000 high school and university students, examining how the types of comments they received would predict the change in their grades between draft and final submission. Hattie et al.’s analysis showed that the best predictor of grade improvement was the total amount of feedback given. However, the extent of improvement was specifically associated with the amount of so-called “where-to-next" feedback given: that is to say, comments that centered on the learner’s next steps for developing their work or skills. This interesting finding makes sense in the context of a tradition of educational research that emphasizes the value of future-facing, action-oriented advice (e.g., Dawson et al., Citation2019; Sadler et al., Citation2023). But psychologists and practitioners might reasonably ask next: why did students who received these kinds of comments improve their grades the most? What is/are the mechanism(s)?

offers candidate suggestions. Were students who received more “where-to-next" feedback perhaps more likely to accept the feedback, because the feedback-giver’s written style when giving such comments made them appear more caring or credible? Did the specificity of these comments lead students to perceive less effort or difficulty being required for improving their work? Were these comments briefer and therefore more likely to be read in full? Or did they involve more concrete language that was easier to understand or to absorb? Did the constructive style of these feedback comments encourage students to seek additional clarification? Did these comments invite students to spend more time thinking deeply and elaboratively about their next steps? Any of these accounts is plausible in principle—although some might be straightforward to rule out based on the data—and would be testable in future with well-selected psychological research methods. Moreover, the answers to these questions are critical to how Hattie et al.’s (Citation2021) important findings might be applied in learning contexts. Specifically, understanding this mechanism could afford greater understanding of the contexts and circumstances in which giving lots of “where-to-next" feedback to learners is most effective, and where it might have little impact.

Suppose, for instance, that researchers found "where-to-next" comments to be associated with grade improvement principally because they create a more positive, supportive impression of the feedback-giver, causing learners to trust the feedback. In this hypothetical scenario one might predict—and could empirically validate—that "where-to-next" comments are beneficial mainly in those feedback dialogues for which initial trust-building is a primary concern. Based on this reasoning we might anticipate no benefits—or even negative effects—when such comments are given within well-established, trusting relationships for example, or in cultural contexts where compliance to authority has greater paramountcy than does interpersonal trust. But now consider a different explanatory account: suppose that "where-to-next" comments are associated with grade improvement principally because they tend to involve more concrete, understandable language than do other kinds of feedback comments. If that were the case, then one might have no reason to expect the benefits of these comments to depend on the interpersonal or cultural contexts described above. But finding empirical support for this account might instead lead one to conclude that focusing educators’ resources on giving lots of “where-to-next" advice is a poor use of those finite resources, when what learners really need is clearer advice. Last, consider a third explanatory account. Because social dynamics can shape the kinds of advice that feedback-givers give (e.g., Harber, Citation2023), suppose that the giving of “where-to-next” feedback is actually a consequence of learning environments’ effectiveness, rather than a cause. For example, the same positive features of learning environments that foster strong student learning may also foster educators’ confidence in offering constructive, “where-to-next” feedback to students. If this causality were true, then there would be no reason to expect—at least based on these findings alone—that changing the kinds of feedback we give to learners would make any discernible difference to their outcomes.

To emphasize, these scenarios and predictions are hypothetical. But they underscore the point that understanding mechanism is critical to how scientists and practitioners make sense of feedback effects, determine their replicability and generalizability, and apply them effectively and responsibly to real-world learning contexts. By foregrounding psychological questions about mechanisms, researchers can be better equipped to select informative outcome variables and appropriate research methods for evaluating feedback interventions. And just as importantly, doing so allows researchers to better identify relevant theory and empirical evidence that already exists in the psychological literatures, but that is otherwise easily overlooked when focus is placed solely on performance-based “impact.”

Is it sufficient merely to ask the ‘right’ questions?

Here we have argued that a psychological science of feedback should be tasked with asking—and answering—questions about mechanisms that underpin feedback effects. In doing so, researchers, journal editors, reviewers, and other beneficiaries all have important roles to play in ensuring robust scientific standards. These colleagues are well positioned to drive forward this field’s scientific credentials, ensuring that published empirical studies have a strong theoretical grounding and that high standards of quality and rigor are met. In this respect, gatekeepers can incentivize researchers to go beyond merely ensuring that their data support their claims, and toward using methods and measures that afford stronger, more informative claims. Moreover, although not suggested by any of the papers in our review, it would be remiss not to mention that an effective psychological science of feedback must increasingly prioritize transparency and reproducibility, adhering to the open science concepts and approaches that are already transforming many scientific disciplines for the better (see Gehlbach & Robinson, Citation2021, and other contributions to their recent special issue of this journal on “Educational Psychology in the Open Science Era”).

But we have also observed above that educational researchers sometimes underestimate the wealth of theory-driven behavioral research on feedback mechanisms that already exists, even whilst those same researchers bemoan the absence of theory-driven, behavioral research. It is therefore clear that merely asking and answering scientific research questions about psychological mechanisms is not, in and of itself, sufficient to stimulate the integration of this science into educational research. To grasp even what is already known about the science of feedback, let alone to foster the further advancement of such a science, researchers must take steps to disrupt the silo-ing of relevant behavioral research. Indeed, even those few studies we described above—to illustrate the various phases of our framework—were published in journals that span social psychology, cognitive psychology, consumer research, behavioral medicine, human-computer interaction, instructional science, and organizational behavior. Each of these (sub)fields, and many others, contains feedback researchers each with their own theoretical perspectives, specialist research methods and techniques, and foundational literatures. And so, unlike the very cohesive community of educational researchers who conduct feedback research and who publish in specialist education journals, the behavioral science of feedback enjoys far less cohesion and community. We might contend that much of the more “scientific” feedback research tends not to be published in outlets commonly frequented by education researchers, and indeed, that even those feedback researchers who take more-scientific approaches would find it impossible to synthesize the cumulative evidence scattered across so many disparate literatures.

And so we believe not only that feedback research must become more scientific, but also that feedback science must become more cohesive. Educational researchers must find ways to better integrate existing research and theory from across diverse subdisciplines of psychology, and indeed psychologically informed research from business, marketing, health sciences, and other disciplines. To this end, forums are needed—perhaps professional societies, journals, conferences—in which diverse feedback science can be brought together under a unified umbrella. This kind of scientific community would stand to foster interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary collaborations, which would lend themselves to tackling some of the most stubborn limitations of the current feedback literature, such as the weak evidence of the transfer and generalizability of effects. It would afford a greater diversity of perspectives, and of research methods and outcome measures. And as Nieminen et al. (Citation2023) proposed, it would improve the cohesiveness of theory and evidence, affording more-unified theoretical perspectives and preventing unnecessary duplication of efforts.

This special issue

In sum, establishing a cohesive psychological science of feedback requires spaces—literal and metaphorical—in which the behavioral feedback research from diverse subfields of psychology and other psychologically-informed disciplines can appear side-by-side, brought together such that researchers from one “silo” can benefit from theoretical developments in other “silos,” and build bridges that foster inter-silo collaboration. In the spirit of fostering and inspiring this kind of cohesion, this special issue features four substantive papers that we suspect would rarely feature alongside one another in the same journal, nor perhaps at the same academic conference. Yet all four papers are written by psychologists working on understanding the effects and effectiveness of feedback through different lenses, and whose work raises complementary questions and conclusions about the research, practice, and mechanisms of receiving feedback. In bringing these papers together, we aim to draw readers’ attention to the insights that these multiple lenses bring to how the effectiveness of feedback is conceptualized, measured, and evaluated.

In the first paper, Fyfe et al. (Citation2023) draw upon developmental psychology research—which we see as receiving insufficient attention in the educational feedback literature—asking to what extent children aged 3–11 benefit from receiving corrective feedback, and to what extent there are known developmental changes or individual differences in such benefits. They review empirical work conducted in three applied domains—literacy, mathematics, and problem-solving—highlighting a wealth of feedback science that already exists in the developmental psychology literature. In many ways, Fyfe et al.’s observations from these studies with children parallel the adult feedback literature. In particular, Fyfe et al. point to considerable variability in feedback benefits, with corrective feedback sometimes having negative rather than positive effects. They highlight that whereas there is good evidence of the short-term benefits of receiving such feedback, there is far less evidence in respect of longer-term benefits and of their transfer to new tasks. And they describe a lack of cohesiveness in this developmental literature that often precludes stronger conclusions. This lack of cohesiveness is not due to any lack of robust scientific approach, rigorous experimental designs or behavioral outcome measures, nor to an absence of good theoretical grounding. Rather, it is a product of how research investigations even within this specialist field have been “siloed”: researchers in different groups have been asking related questions using different methods and tasks, each using narrow samples of differently-aged children, thus making it difficult to isolate the root cause of developmental effects.

The second paper, by Fong and Schallert, takes a social psychological perspective by exploring the interplay of motivation and emotion theories as they pertain to the impact of feedback on learning. Structured around five key questions concerning learners’ responses to feedback, their review identifies significant potential for such theories to elucidate the mechanisms via which feedback is effective. For example, they suggest that automated feedback might have limited effectiveness because it fails to replicate the social dynamics of effective feedback interactions: notably, learners’ perceptions of credibility, trust, and relatedness. Yet many of the opportunities for theoretical synthesis that Fong and Schallert identify represent areas for future exploration, rather than areas in which robust synthesis is already occurring. Indeed, they argue that feedback research and motivational research have largely developed along two parallel paths with limited integration or synthesis. Once more, we see the importance of “de-siloing” for a cohesive psychological science of feedback. Fong and Schallert’s work provides a roadmap for how a such a science might fruitfully capitalize upon the sciences of emotion and motivation, in particular by drawing on common psychological methods from those domains—such as experience sampling—to disentangle competing explanations of observed effects in feedback contexts.

The third paper in this special issue, by Harber, draws upon a very different social psychological perspective. Harber overviews a rich experimental literature that demonstrates a “positive feedback bias” when White instructors give feedback to racially minoritized learners. Specifically, studies show that White instructors tend to offer overly positive feedback to such learners and conceal hints at criticism, perhaps in conscious or subconscious efforts to avoid appearing prejudiced. Harber proposes a new theoretical model to account for diverse findings in this literature, and considers the impact that disingenuous praise could have on minoritized learners’ engagement with feedback, and self-esteem. We believe this paper will fascinate educational researchers and feedback-givers who may not have contemplated their susceptibility to implicit bias in these respects, nor how this bias might be mitigated. But we also see it as providing an example of highly programmatic, theory-driven feedback science, wherein researchers have not only demonstrated a robust effect, but also attempted to systematically disentangle competing accounts of its psychological mechanisms as a means to inform robust, evidence-based feedback interventions for real learners. We are particularly excited to see this literature continue unfolding in the Open Science era.

In the fourth paper, Brown and Zhao adopt a psychometric perspective, offering a defence of the use of self-report inventories in feedback research. As we have discussed, many feedback researchers criticize the field’s over-reliance on students’ perceptions of feedback as a proxy for feedback effectiveness. Brown and Zhao make an important contribution to the special issue by arguing the potential for self-report measures to advance understanding of effective feedback, but also by documenting the extent to which this potential is currently untapped. They propose that, in principle, self-report measures can be valuable because of their structured and replicable approach to measurement. Yet in their review of instruments that assess students’ perceptions of feedback, just ten met their threshold for being considered “high-quality” in terms of psychometric properties. Their analysis has important implications for the role of self-report measures within a cohesive psychological science of feedback. First, they found only one study in which robust self-report inventory measures were empirically demonstrated to relate to behavioral outcomes. Like Brown and Zhao, we believe that self-reports can be informative, but we lament the lack of strong evidence that existing measures do indeed predict real-world behaviors and outcomes. Second, mirroring the findings of our present synthesis, Brown and Zhao argue that studies on students’ perceptions of feedback must better demonstrate the transfer of the outcomes of feedback perceptions across domains, and demonstrate stronger approaches to replication across cultural contexts. Third, they observe that the papers they reviewed were published in a wide range of disciplinary areas with medical, educational, and management foci, yet rarely in Psychology journals. They question why, given the psychological roots of studying students’ perceptions, this approach has not been of greater contemporary interest to psychologists.

To complete the special issue, Panadero’s commentary draws together several key themes that emerge from the target papers individually and in combination. Noting that there might be an ongoing “paradigm shift” in how researchers understand and study feedback processes empirically, Panadero highlights how these ongoing changes mirror those that have already occurred in the related research domain of self-regulated learning. By considering the tasks ahead for feedback researchers through the lens of self-regulated learning research, we believe Panadero’s commentary provides another important caution to these researchers against reinventing the wheel. Indeed, our earlier arguments about “de-siloing” apply in this context too, as there clearly are important lessons to learn from the evolution of other topics in educational psychology, heeding which could serve to propel feedback research forward with greater efficiency and impact. Using the special issue papers as exemplars of the current state of the feedback literature, Panadero points to aspects of a paradigm shift that are already in full swing, and to others that are likely to follow.

Conclusion