ABSTRACT

Human resource management (HRM) practices in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to increase employees’ job satisfaction are on the rise. Given that SMEs often adopt highly formalized HRM practices of large companies, for example, in the case of annual performance appraisals, we investigate the relationship between the degree of formalization of annual performance feedback and employees’ job satisfaction in the SME context. Using an experimental survey study design (N = 166) in a German SME, we find that employees receiving annual performance feedback with a high degree of formalization report lower job satisfaction directly after the annual performance feedback than those who are still to receive their feedback. In contrast, in the case of annual performance feedback with a low degree of formalization, employees report higher job satisfaction right after the annual performance feedback than employees before the feedback. Moreover, we find that employees’ feedback orientation is an important moderator in this relationship.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

HRM practices, such as performance management, and talent management, have a positive effect on company performance (Delaney & Huselid, Citation1996; Heilmann et al., Citation2018; Saridakis et al., Citation2016; Zheng et al., Citation2006). The most important HRM practice in this context is the annual performance appraisal, which addresses employees’ past performance and future development possibilities (DeNisi & Pritchard, Citation2006; Fletcher & Robinson, Citation2014; Kampkötter, Citation2017; Murphy & Cleveland, Citation1995; Selvarajan & Cloninger, Citation2012). This kind of performance feedback increases job satisfaction, helps improving employees’ performance and aligns employees’ behavior with the organization’s objectives (Anseel & Lievens, Citation2007; Drnovsek et al., Citation2023; Grubb, Citation2007; Mosquera et al., Citation2018; Rosen et al., Citation2006; Sparr & Sonnentag, Citation2008). While these insights are based on studies of large organizations, little is known about the effects of HRM practices and performance appraisals in SMEs (Carlson et al., Citation2006). Moreover, to date there is only limited empirical research investigating whether the effect of managerial interventions and employees’ reaction is in fact causal (Kampkoetter, Citation2017; Manthei et al., Citation2022).

When SMEs adopt HRM practices, the majority of SMEs overdo it and adopt overformalized methods and processes prevailing in large companies without verifying their organizational fit for the SME (Cunningham & Rowley, Citation2010; Heilmann et al., Citation2018; Krishnan & Scullion, Citation2017; Richbell et al., Citation2010). Following Heilmann et al. (Citation2018), we argue that simply adopting highly formalized HRM practices from larger organizations can be detrimental for SMEs, given that the context of SMEs is quite different from large organizations in terms of HRM challenges as well as the implementation of HRM practices. Specifically, Kaman et al. (Citation2001), Klaas et al. (Citation2012), Li and Rees (Citation2020) and Heilmann et al. (Citation2018) describe that work in SMEs is more agile (that is, more dynamic and adaptable), that there is more open dialogue, and employees do not just have to follow orders. Therefore, they encourage SMEs to implement their individual HRM practices that acknowledge and are sensitive to this specific context (Bloom et al., Citation2007; Heilmann et al., Citation2018; Sels et al., Citation2006). To better understand the potential causal effects of adopting highly formalized HRM practices—in this case annual performance feedback (APF)—in SMEs, we ask the following central research question: How does APF affect employees’ job satisfaction in SMEs, and which role does the degree of formalization play in this context?

In assessing this question we build on Wright (Citation1985) and Kohn (Citation2018), and argue that performance feedback may be a double-edged sword. On the one hand we know that formal procedures may give employees the feeling that management pays attention to HR issues, and thus increase employees’ job satisfaction (Heilmann et al., Citation2018; Ismail et al., Citation2016; Kaman et al., Citation2001; Kotey & Slade, Citation2005). On the other hand Grubb (Citation2007) and Kampkötter (Citation2016) highlight that the dark side of being formally appraised—that is, lower job satisfaction—materializes if the performance feedback predominantly reflects formal documentation with standardized forms and criteria to assess the employee as opposed to coaching the employee based on feedback characterized by mutual involvement (Lee, Citation2006). We hypothesize that this potential negative effect of highly formalized performance feedback on employees’ job satisfaction will dominate in SMEs, given that company culture, leadership and interactions in SMEs are most often characterized by low hierarchies, an open dialogue and a high employee involvement (Heilmann et al., Citation2018; Kotey & Slade, Citation2005). In contrast, a low degree of formalization in performance feedback, that is in line with the described communication habits in SMEs, will lead to the desired increase in employees’ job satisfaction.

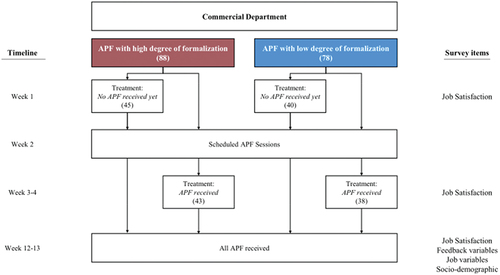

To answer our research question, we conducted an experimental survey study in a family owned German SME that has approximately 386 employees with an annual turnover of €46.8 million in 2018. We had the unique opportunity to conduct our experiment in a department with 166 employees, where two formats of annual performance feedback (APF) have been used used: While one group of employees (88) has always received APF with a high degree of formalization, the second group of employees (78) has always received APF with a low degree of formalization. Within this setting we tested the hypotheses that (a) an APF based on a formalized and predefined structure in terms of a standardized form (high degree of formalization) will lead to lower levels of job satisfaction, and (b) while keeping the content of the APF constant, an APF with a low degree of formalization leads to higher job satisfaction (Grubb, Citation2007; Lee, Citation2006). Moreover, building on Grubb (Citation2007) and Frederiksen et al. (Citation2020), we suggest that not all employees will perceive the same performance feedback setup as equally satisfying. Therefore, we introduce individual feedback orientation as an important moderator of the relationship between the performance feedback’s degree of formalization and employees’ job satisfaction.

Our analysis reveals that, in line with our hypotheses, there is a sizable effect of receiving APF with a high as well as a low level of formalization on job satisfaction. In our first experiment, where employees receive an APF with a high degree of formalization—employees report lower job satisfaction than employees before the performance feedback session. In our second experiment, where employees receive an APF with a low degree of formalization—we observe that employees report higher levels of job satisfaction right after the performance feedback session than beforehand. Moreover, for employees with a less formalized APF, we observe that employees with high levels of individual feedback orientation—those employees who like to have feedback and see feedback as a source of meaning for their work relationship (Dahling et al., Citation2010) profit from the less formalized APF and report much higher levels of job satisfaction compared to employees with low levels of individual feedback orientation.

This paper makes three contributions to the literature. First, while the current literature focuses mainly on large companies and their HRM practices, we conduct a study on APF in a German SME context. Building on Sels et al. (Citation2006), Bloom et al. (Citation2007) and Heilmann et al. (Citation2018), we theorize and provide empirical evidence that highly formalized HRM practices that are commonly used in large companies cannot simply be transferred to SMEs. Specifically, we show that while a high degree of formalization of the performance feedback negatively affects employees’ job satisfaction, a low degree of formalization stimulates employees’ job satisfaction.

Second, we show that the effect of APF is contingent upon the employee’s feedback orientation, further supporting the conjecture that the effects of performance feedback cannot be thoroughly investigated without considering an employee’s individual needs (Braddy et al., Citation2013; Grubb, Citation2007; Linderbaum & Levy, Citation2010). This ties in with the theory of London and Smither (Citation2002), which anticipates that feedback orientation is directly related to individual differences and how individuals receive and process feedback.

Third, within the entrepreneurship literature, our study complements a limited set of studies, including notable works such as Rigtering et al. (Citation2018) and Monsen et al. (Citation2010), that employ field experimental methods to elucidate authentic employee responses. Our experimental design substantiates the causal linkage between the reception of performance feedback and ensuing job satisfaction. Specifically, our study illuminates the causal effect of receiving APF with a low degree of formalization on job satisfaction and the causal effect of APF with a high degree of formalization on job satisfaction. This ensures that any difference observed is due to the reception of feedback.

Theoretical background and hypotheses

Formal procedures

Many SMEs know the situation: as the company grows, structures and an increasing degree of standardization of processes are needed to increase productivity and to further scale the business (Hornsby & Kuratko, Citation1990; Kotey & Slade, Citation2005).Footnote1 This also holds true for managing the human resources of the business more systematically (Kaman et al., Citation2001).

HR practices refer to various strategies, policies, and procedures that an organization implements to manage its human resources effectively (Heilmann et al., Citation2018). These practices are designed to attract, develop, motivate, and retain employees, ultimately contributing to the overall success of the organization (Becker & Huselid, Citation2006). HR practices encompass a wide range of activities, including recruitment, training and development, performance management, compensation and benefits, employee relations, and more (Bloom & Van Reenen, Citation2007; Carlson et al., Citation2006; Heilmann et al., Citation2018).

Annual performance feedback as a double-edged sword

Pearce and Porter (Citation1986) and Murphy and Cleveland (Citation1995) defined annual performance feedback as a special kind of feedback to employees about their performance in their job. Following DeNisi and Pritchard (Citation2006), this kind of performance feedback is a “discreet, formal, organizationally sanctioned event, usually not occurring more frequently than once or twice a year” (p. 245). It has been shown that many characteristics of this APF, for example, employee participation, goal achievement, perceived justice, and fairness, are positively linked to job satisfaction, resulting in guidelines how to design APF and to reduce subjectivity (Colquitt et al., Citation2001; Kampkötter, Citation2016; Nathan et al., Citation1991; Palaiologos et al., Citation2011; Taneja et al., Citation2023).

However, it has also been shown that formal APF is not the panacea for motivation and satisfaction, that there is no such thing as the “one and only” correct performance feedback format and system (Longenecker & Nykodym, Citation1996), and that the benefits and advantages are even often overestimated. Following Wright (Citation1985) and Longenecker and Nykodym (Citation1996), the mere existence of a formal performance feedback system does not guarantee an effective performance feedback. The meta-analysis of Kluger and DeNisi (Citation1996) shows that more than one third of all performance feedback sessions have low effectiveness (Behn, Citation2003; Grubb, Citation2007; Longenecker et al., Citation1987). Moreover, Grubb (Citation2007) highlights that neither employees nor supervisors favor formal performance feedback because formal documentation tends to demotivate, reduce performance, and lower job satisfaction.

Given these conflicting findings in the literature regarding the association between formal APF and employees’ job satisfaction, we develop arguments under which conditions we expect the effect (positive or negative) of formal APF to materialize in SMEs and their distinctive interaction and communication habits of low hierarchies, high employee involvement and open dialogue. Specifically, we argue that the degree of formalization of the APF plays a decisive role, as it may influence the satisfaction of the employee with the performance feedback itself, and likewise employees’ overall attitudes toward their work and job situation, resulting in changes in the level of job satisfaction (Jawahar, Citation2006).

Degree of formalization and job satisfaction

APF can differ enormously in terms of standardization and formality (Grubb, Citation2007; Lee, Citation2006; Wanguri, Citation1995). One extreme form of APF can be a highly formalized and standardized approach. A highly formalized APF describes an annual performance feedback session that follows a rigid performance evaluation form with strict criteria—for example, in terms of checklists, rating scales, or essay appraisals. The ratings and statements will be written by the appraiser alone, or it will be composed together with the employee. Sometimes employees complete a self-evaluation before the supervisor completes the performance feedback evaluation form. The APF with a high degree of formalization leaves little to no room for assessing the employee outside or beyond this predefined set of questions and rating categories (Grubb, Citation2007; Lee, Citation2006). Another extreme form might be an APF that represents a meeting between the employee and the supervisor without any explicit guidelines on how the meeting should be conducted. This format can be labeled as nonformalized APF.

APF with a high degree of formalization may lead to higher job satisfaction for three reasons. First, formalization of performance feedback may contribute to perceived fairness and accuracy from the employee’s perspective (Latham et al., Citation1993; Murphy & Cleveland, Citation1995). By implementing standardized forms for APF, subjectivity and favoritism in performance feedback can be mitigated (Frederiksen et al., Citation2017, Citation2020). This, in turn, enhances the employee’s perception of fairness and accuracy in the feedback, which may directly influence job satisfaction. The standardized approach provides a consistent framework for supervisors/appraisers, reducing the potential for biases and increasing the employee’s confidence in the feedback process. Second, a formal and highly structured APF may provide the employee with process-related certainty. Wanguri (Citation1995) argues that the absence of a formal and well-prepared evaluation may cause employees to feel slighted in the performance feedback process itself. This results from the lack of a feeling of fairness and accuracy and leads to employees being dissatisfied with the performance feedback process, which negatively impacts job satisfaction (Dusterhoff et al., Citation2013; Jawahar, Citation2006; Molvi, Citation2015). Third, a formal and highly structured APF can be described as more transparent, since the structure and criteria are known. As a result, there is no perception problem toward the performance feedback process which also reduces dissatisfaction (Dusterhoff et al., Citation2013; Jawahar, Citation2006; Molvi, Citation2015).

However, despite these potential advantages, employees may perceive the APF as overformalized, given the strict form and predefined criteria and assessment categories. As described by Grubb (Citation2007) and Lee (Citation2006), it conflicts with mutual involvement aiming at coaching the individual employee, instead of controlling and monitoring them. Moreover, it does not allow for assessing the employee outside or beyond this predefined set of questions and rating categories. A highly formalized APF may be perceived as a barrier in cooperative working relationships and it is seen as bureaucratic and defensive, regulating rather than taking care of professional development (Kampkötter, Citation2016; Wanguri, Citation1995).

We argue that in the context of SMEs the potential negative effects of highly formalized APF outweigh the potential positive effects. Specifically, we conjecture that despite the increased perceived fairness and accuracy of the APF with a high degree of formalization, employees in SMEs are used to and appreciate being involved, working cooperatively, and having open dialogue. Thus being forced into strict formal assessment criteria that leave little room for the individuality of the assessed employee will lead to lower job satisfaction.

Hypothesis 1 (APF with a high degree of formalization):

Employees’ job satisfaction is significantly lower after they receive APF with a high degree of formalization.

In contrast, in the case of an APF with a low degree of formalization, we expect the described negative effect of an APF—that materializes in the case of a high degree of formalization—not only to be absent, but argue that employees respond to the performance feedback with a low degree of formalization with higher job satisfaction. The lower degree of formalization in terms of less standardized and predefined forms, criteria, and assessment categories encourages the mutual exchange of information between the appraiser and the employee (Grubb, Citation2007). This type of APF enables supervisors and employees to speak freely, establishes constructive two-way communication, and is supportive during the feedback (Kaymaz, Citation2011). In this context Grubb (Citation2007) argues that supervisors also prefer more informal but effective leadership practices. “The wrong way is using standard forms and criteria, rather than mutual involvement with the employee and coaching for improved performance and contribution“ (Grubb, Citation2007, p. 3). Given that an APF with a low degree of formalization provides this opportunity for mutual involvement and a rather developmental approach, we expect employees’ job satisfaction to increase when receiving the APF.

Hypothesis 2 (APF with a low degree of formalization):

Employees’ job satisfaction is significantly higher after they receive APF with a low degree of formalization.

Individual feedback orientation and job satisfaction

Organizations vary in their approach to how they conduct performance feedback, and employees themselves differ in their attitude toward dealing with feedback. This phenomenon, called feedback orientation, has been captured in various theoretical models in HR management (Ashford & Cummings, Citation1983). The individual’s feedback orientation, also known as “an individual’s overall receptivity to feedback” (London & Smither, Citation2002, p. 81), is a multidimensional construct and describes that every recipient responds to feedback uniquely. Individuals with a high feedback orientation perceive feedback as being of higher value and are, therefore, more likely to respond to it (Brett & Atwater, Citation2001). For these individuals, feedback is a possibility to improve task performance, achieve personal and career goals, and expand their abilities (Anseel et al., Citation2013). This would also reflect current debates explaining that there are employees who are proactive in their careers, here related to the concept of protean career orientation which explains self directed career development driven by personal values to achieve personal pride and success (Gaile et al., Citation2022).

Individuals who are low on feedback orientation tend to ignore and resist feedback (Blinebry, Citation2016). Due to the central role of feedback in APF sessions, it is expected that the degree to which one is defensive when receiving feedback will affect his or her satisfaction with this session (Linderbaum & Levy, Citation2010). London and Smither (Citation2002) stressed that a high feedback orientation lessens emotional reactions to feedback. High feedback orientation thus helps the individual to process feedback mindfully and thoughtfully and to leverage feedback effectively.

Individual feedback orientation as a moderator

We have argued that when APFs are highly formalized in SMEs, the potential negative impacts outweigh the potential positive impacts because employees in SMEs are used to—and value—being included and that one can openly and constructively engage in a dialogue (Heilmann et al., Citation2018; Kotey & Slade, Citation2005). In the highly formalized APF, we expect differences in the perception of the APF—as well as its effect on job satisfaction—more generally between individuals with high and low feedback orientation levels. Specifically, an individual with a high feedback orientation may perceive all kinds of APF as valuable and may be less negatively affected by the degree of formality. Moreover, given that higher feedback orientation entails that the individual can distance herself emotionally from the performance feedback (Linderbaum & Levy, Citation2010; London & Smither, Citation2002), the employee can also leverage the received performance feedback in a highly formalized APF.

Hypothesis 3 (Feedback orientation and APF with a high degree of formalization):

Employees with higher levels of individual feedback orientation will react less negatively to APF with a high degree of formalization than employees with lower levels of individual feedback orientation.

We have argued that when APFs with less formalization are used in SMEs, we expect that employees indeed reciprocate the performance feedback with higher job satisfaction, because it establishes a constructive two-way communication and the supervisor may be supportive during the feedback (Kaymaz, Citation2011). Employees with a high feedback orientation seek feedback continuously and are interested in feedback interactions, such as APF (Dahling et al., Citation2010). Therefore if these individuals face APF with a low degree of formalization, which stimulates an open exchange and inclusive discussion, an additional positive effect on job satisfaction is expected.

Hypothesis 4 (Feedback orientation and APF with a low degree of formalization):

Employees with higher levels of individual feedback orientation will react more positively to APF with a low degree of formalization than employees with lower levels of individual feedback orientation.

Context and experimental design

Company and organizational structure

The sample consists of commercial employees of a Software-as-a-Service company. The company is family owned, situated in Germany, has been offering software products throughout Europe for more than 20 years and has 386 employees. To test our hypotheses, we run an experimental survey study in two sales groups of the company with a comparable number of employees. They have core distributional functions toward the customer in generating revenue growth. A manager has disciplinary responsibility for all members of the respective groups and exclusively conducts all performance feedback sessions.

The uniqueness we exploit in the experiment is that this setting offers two different annual performance feedback formats, with one group of employees receiving APF with a high degree of formalization, and another group receiving APF with a low degree. Specifically, while the first group of employees has always received APF with a high degree of formalization, the other group has always received APFs with a low degree of formalization.

Employees in our field experiment are observed in their natural work environment. This is why the results we observe are more likely to have higher external validity and can be transferred to other contexts unlike results from an abstractly framed laboratory experiment (Harrison & List, Citation2004).

Annual performance feedback setting

An APF takes place with each employee in the last quarter of the year. This feedback session is conducted by the manager with each employee individually and lasts a maximum of two hours. All APFs independent of their degree of formalization (high or low), are comparable in terms of content. The following topics are specified by the general management to be discussed in an APF: feedback on behavior and working methods, the achievement of agreed targets, targets for the next year, training possibilities and general topics for the following year. However, the sessions clearly differ in the degree of formality, APF with a low degree of formalization and APF with a high degree of formalization. Employees in the respective groups are accustomed to either APF with a high or low degree of formalization, given that the two formats have been used as the standard APF within the company long before our study.

Annual performance feedback and monetary outcomes

In this company, employees do not have any variable pay component. Their work contracts only specify fixed wages and no performance-related part. Consequently, the outcomes of the APF are not directly linked to changes in the employees’ wages. Wage changes in this company, however, only occur discretionary (that is, based on tenure, or market developments). The fact that the APFs are not linked to monetary incentives allows us to reflect the current development in companies—aside from the strong emphasis on financial rewards and punishments in APF processes (Cappelli & Tavis, Citation2016).

Annual performance feedback with a high degree of formalization

The APF with a high degree of formalization follows a specific evaluation form with clear criteria and rating scales, using a rigid feedback evaluation sheet. This evaluation sheet is adhered to meticulously during the APF and there is no room to discuss other things. In line with Grubb (Citation2007) and Lee (Citation2006) this meets all criteria of highly formalized APF. The employees receive this feedback evaluation sheet two weeks before the appointment. The evaluation sheet consists of four sections (working conditions, work results and professional competencies, a summary of performance evaluation, and individual quantitative targets for the next year).Footnote2 The manager has to complete the feedback evaluation sheet for each employee, too. It is the same sheet the employee receives, the only difference being that the employee’s work results in the second section are only for the manager’s information about the employee’s performance. The scales for the work-related competencies are referred to as “evaluation by the supervisor.” Neither the employee nor the manager receives the other’s evaluation sheet before the session. During the APF, the evaluation sheets are the formal basis for the APF. During the APF, the evaluation sheets are discussed and summarized in one document. In the end, the manager and the employee have to sign the final evaluation sheet mutually.

Annual performance feedback with a low degree of formalization

The APF with a low degree of formalization does not follow any highly formalized form. The employees do not receive any preparation instructions or sheets before. Only an appointment with the name “Annual Performance Feedback” is agreed upon. The employees and the manager prepare themselves individually. The employee and the manager can determine the focus of the discussion themselves. However, the conversation content of this APF does not differ from the APF with a high degree of formalization, since it is clear to everyone which topics are discussed in an APF. As in the case of the APF with a high degree of formalization, the manager and the employee discuss working conditions, results, competencies and targets for the next year. However, to make the difference to the APF with a high degree of formalization clear: In the APF with a low degree of formalization there is no highly formalized structure in the conversation, the participants do not work through an evaluation sheet point by point, and no evaluation sheet is signed.

Field experimental survey study and treatments

To answer our research question, we conducted an experimental survey study (Kraus et al., Citation2016). We took advantage of the fact that performance feedback sessions are centrally scheduled and randomly divided employees with a scheduled performance feedback session into two separate treatments. We randomized employees into both treatments with a simple randomization technique: we flipped a virtual coin for each employee before the experiment.

In the treatment No APF received yet, employees received a link to a first short online survey about their job satisfaction one week before their performance feedback session, based on the single-item measure on job satisfaction (Staelens et al., Citation2016). In the treatment APF received, after the performance feedback had been concluded, we sent employees a link to the same short online survey, including the single-item measure on job satisfaction (Staelens et al., Citation2016).

Eight weeks after every employee had received the APF, we sent a separate survey to all employees to gather additional information about individual employee characteristics. In particular, we asked employees about the following: job satisfaction, individual feedback orientation, perceptions of the informal feedback environment, satisfaction with the APF, and additional control variables. The overall job satisfaction measure of the first part of the survey was repeated.

provides an overview of the timeline and events throughout the experiment. The week before the experiment, the group using APF with a low degree of formalization (APF with a high degree of formalization) had 115 (118) employees. In the former 78 (40 in APF received, 38 in No APF received yet), while in the latter 88 (45 in APF received, 43 in No APF received yet) responded to the initial online survey.Footnote3 Although not all employees responded to the initial online survey on job satisfaction, we observe no differences in attrition between the treatments. Moreover, we do not observe any attrition between the first short online survey and the second extensive online survey. We link the employees’ answers from the first to the second part of the experiment. To guarantee employees’ anonymity, we generated a unique employee identifier that was handed out to the employees before the experiment on a sheet of paper; we asked employees to keep this code until the end of the study. Since the first part of the survey—one week before the APFs—only referred to job satisfaction in general, and only after the APFs was the questionnaire on the feedback relevant questions sent out, we assume that participants were aware that a study was taking place, but not aware of the intervention. The anonymity was very important from the beginning, because we wanted to make sure that there was a high willingness to evaluate the APFs and that the employee did not have the feeling that the supervisor could subsequently draw conclusions about individual employees and the evaluations they had made.

Measures

Job satisfaction

Job satisfaction was measured in both parts of the evaluation by the single-item “How satisfied are you with your job?” on a 11-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (totally unhappy) to 10 (totally happy).Footnote4 We relied solely on this single-item measure for mainly three reasons. The first reason was that in our data, the single-item measure correlated highly with the dimensions of the multiple-item measures. A simple pairwise correlation between the single-item job satisfaction measure and the multiple-item measures reveals a correlation coefficient of at least .446 (p < .0001).Footnote5 The second reason is that existing research shows the construct validity of such a measure may be higher than that of multiple-item measures (Nagy, Citation2002; Poon, Citation2004). The third reason is that it can be shown that the single-item measure appears to be less influenced by temporal emotional factors linked to a particular job facet (Staelens et al., Citation2016). Consequently, observing the effect of our treatments on the single item measure would deliver much more robust evidence for the influence of feedback on job satisfaction.

Individual feedback orientation

To measure employees’ feedback orientation, we used the feedback orientation scale developed by Linderbaum and Levy (Citation2010). The individual feedback orientation comprises four distinct dimensions of feedback orientation. Cronbach’s alpha for the four dimensions is sufficient (between α = .77 and α = .91). For this paper, we do not differentiate between the four dimensions but aggregate and standardize them to one score for each employee, when testing our moderation hypotheses 3 and 4. This aggregated variable will be called Individual feedback orientation in the following analysis. We decided to ask about the individual feedback orientation in the second survey to obtain the general feedback orientation. In the first part of the survey, this question was deliberately not asked in order not to influence the individuals one week before the APFs, as we assumed that an explicit question on feedback orientation shortly before the APF could influence the employees too much and the goal of the experiment would certainly have been clear.

Feedback-related controls

Informal feedback environment

We use the feedback environment scale by Steelman et al. (Citation2004) to measure employees’ perceptions of the company’s informal feedback environment. This scale provides a measurement of the employee’s perceptions of the overall supportiveness for feedback in the workplace in seven dimensions: source credibility (expertise and trustworthiness); feedback quality (consistency and usefulness); source availability (amount of contact with source and ease of obtaining feedback); feedback delivery (the way feedback is delivered, including consideration for the person appraised); favorable feedback (perceived frequency of positive feedback); unfavorable feedback (perceived frequency of negative feedback); and promotes feedback-seeking (support and encouragement to seek feedback). Internal consistency is sufficient for all dimensions (between α = .75 and α = .92). For our study, we aggregate and standardize all responses to form one measure that captures the employees’ perception of the feedback environment (henceforth, Informal feedback environment).

Satisfaction with annual performance feedback

To measure the satisfaction with the annual performance feedback, we combine seven different dimensions previously used in the literature. These dimensions are (i) general satisfaction with the feedback session, (ii) satisfaction with the feedback procedures (Giles & Mossholder, Citation1990), (iii) the perceived utility (Greller, Citation1978), (iv) the accuracy of the feedback session (Stone et al., Citation1984), and three dimensions about the perceived fairness of the feedback session: (v) procedural (Keeping & Levy, Citation2000), (vi) distributional (Korsgaard & Roberson, Citation1995), and (vii) interactional fairness (Elicker et al., Citation2006). All dimensions are measures with multiple items on 5-to-7-point Likert-Scales (strongly disagree to strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha documents the internal consistency of each dimension and reaches at least .88. For our study, we aggregate and standardize all responses to form one measure that captures the individual employees’ satisfaction with the formalized feedback environment (henceforth, Satisfaction with APF).

Other controls

To control for job-related factors, we used the controls which are frequently used in the context of job satisfaction (Green & Heywood, Citation2008; Kampkötter, Citation2016). We ask employees about their organizational tenure (avg = 5.7 years), their monthly net income (avg = €2609), and their perceived job security., As sociodemographic controls, we ask for employees’ gender (41% are female), age (avg = 36.83 years), and marital status (46% are married).

Results

Before we analyze the results, we are going to test the validity of our randomization procedures.Footnote6 In particular, we check whether employees in the treatment APF received and No APF received yet are equally distributed on the observable characteristics that we elicit in the second survey. For this purpose, we use a probit regression analysis. In Table A5 we regress a dummy variable (1 if the employee was in the treatment APF received, 0 if the employee was in the treatment No APF received yet) on the self-reported observables such as age, gender, marital status, income, organizational tenure, perceived job security, the employee’s perception of the informal feedback environment and the employee’s feedback orientation. We estimate two separate models.

We observe that the randomization was only partially successful (seven out of nine observables remain insignificant). In model 1 for the employees receiving APF with a low degree of formalization—we observe that employees with higher individual feedback orientation and slightly more female employees are in the treatment APF received; in model 2 we observe that employees with a more positive attitude toward the informal feedback environment and less satisfied with the APF are in the treatment APF received. Thus, in the upcoming analysis, we will control for the respective variables.Footnote7

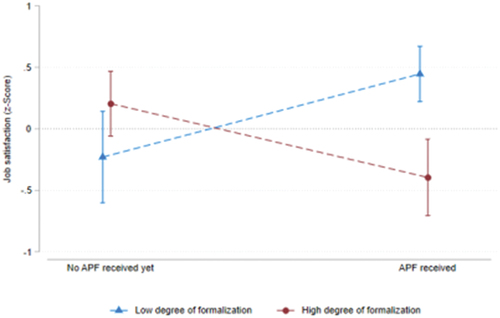

Annual performance feedback with a high degree of formalization

To test our hypothesis 1 we focus on employees receiving APF with a high degree of formalization. is the starting point for our analysis. The red line indicates the levels of job satisfaction. As visual inspection already reveals, we see those employees in treatment APF received report lower levels of job satisfaction than employees in treatment No APF received yet. Comparing the averages between both conditions highlights a significant difference (p = .0023, Mann–Whitney U-test). In regression models (1) to (3) of , we check the robustness of the observed pattern. We find that after including several control variables, the treatment dummy variable remains highly significant and negative, indicating that the APF with a high degree of formalization has a detrimental effect on employees’ job satisfaction. Interestingly, we observe that satisfaction with the APF and job security contribute positively to job satisfaction. Therefore, we find support for hypothesis 1.

Figure 2. Job satisfication and annual performance feedback.

Table 1. Job satisfaction and annual performance feedback.

Annual performance feedback with a low degree of formalization

To test hypothesis 2 we focus on employees receiving APF with a low degree of formalization. Again, is the starting point for our analysis. The blue line indicates employee data from the APF with a low degree of formalization. Mean job satisfaction is higher in treatment APF received compared to No APF received yet. Comparing the averages between both conditions highlights a significant difference (p = .0073, Mann–Whitney U-test).

We utilize additional regression models to verify the robustness of this observation after controlling for several potentially relevant factors. In models (4) to (6) of , we predict employees’ job satisfaction, including all observable characteristics.

Model (4) includes only a dummy variable for the treatment (APF received) and confirms our observation from the nonparametric test. In model (5), we include employees’ perceptions about the informal feedback environment and their feedback orientation, which turn out to be insignificant. Our treatment dummy variable, however, remains highly significant. In model (6), we add additional control variables that remain insignificant for job satisfaction, except employees’ perception of job security, which is positively associated with job satisfaction. Nevertheless, in this model, our treatment variation remains highly significant. All in all, our analysis provides support for hypothesis 2.

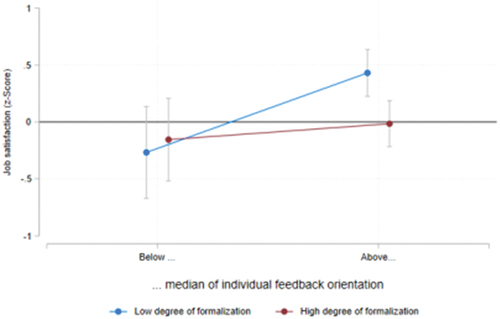

Job satisfaction, annual performance feedback and individual feedback orientation

Employee’s job satisfaction is higher (lower) after an APF with a low (high) degree of formalization. To gain a deeper understanding of how employees’ feedback orientation contributes to this effect, we analyze the survey data more closely. We categorize employees according to a median split of their feedback orientation. In , we plot their average job satisfaction for above and below median individual feedback orientation. The blue (red) lines indicate the data from the APF with a low (high) degree of formalization. As visual inspection already reveals, where the less formalized APF occurs, employees with above-median levels of individual feedback orientation report higher job satisfaction than employees with below-median levels of feedback orientation (p = .0101, Mann–Whitney U-test). No such difference can be observed for the employees who received highly formalized APF.

Figure 3. Job satisfaction, annual performance feedback, and individuals feedback orientation.

More evidence on this moderation effect of individual feedback orientation comes from a regression analysis. In , we include all employees from both groups and treatments. We predict job satisfaction. Model 1 includes a dummy variable for the respective group (1 if APF with a low degree of formalization), a dummy variable for the above level of individual feedback orientation (1 if above-median individual feedback orientation), and a dummy variable for whether the employee was in the treatment (1 if APF received). The positive and significant coefficient for “1 if above-median individual feedback orientation” indicates that employees with higher feedback orientation/receptivity report higher levels of job satisfaction. The other variables remain insignificant and highlight that there are no level effects between the groups and treatments when pooling the data from all our participants.

Table 2. Job satisfaction, annual performance feedback, and individual feedback orientation.

To investigate the moderating relationship of individual feedback orientation, we now interact the dummy variable with the indicator for high levels of individual feedback orientation in Model 2. The positive and significant coefficient of the interaction term indicates that feedback with a low degree of formalization has a larger effect on job satisfaction for employees with high levels of individual feedback orientation. In Model 3, we include additional control variables. The coefficients for the interaction term remain positive and significant. Taken together, we find support for hypothesis 4 but no support for hypothesis 3.

Discussion and conclusion

SMEs increasingly engage in HRM practices to increase company performance (Delaney & Huselid, Citation1996; Heilmann et al., Citation2018; Saridakis et al., Citation2016; Zheng et al., Citation2006). To that end, SMEs tend to adopt highly formalized practices from larger organizations, especially when they have reached a certain size. However, simply adopting highly formalized HRM practices from larger organizations, such as selection procedures of employees, job definitions, evaluations, performance feedback and compensation models, can be detrimental to SMEs as the context of SMEs differs significantly from that of large organizations in terms of HRM challenges (Heilmann et al., Citation2018; Li & Rees, Citation2021). Moreover, this formalism is often taken to extremes, and employees bemoan this extensive formalism (Adler & Borys, Citation1996; Heilmann et al., Citation2018; Hornsby & Kuratko, Citation1990; Kaman et al., Citation2001; Welbourne & Cyr, Citation1999).

Given this focus of prior studies on large organizations, our study investigates the relationship between the degree of formalization and employees’ job satisfaction for the case of the most important HRM practice, that is, annual performance feedback (Murphy & Cleveland, Citation1995; DeNisi & Pritchard, Citation2006; Fletcher & Robinson, Citation2014; Selvarajan & Cloninger, Citation2012; Kampkötter, Citation2017) in the context of SMEs. Moreover, there is only limited knowledge, whether the managerial interventions are actually causally related to a change in employees’ job satisfaction (Kampkoetter, 2017). Our findings reveal that employees’ job satisfaction changes significantly after the APF. More specifically, for employees receiving an APF with a low degree of formalization, job satisfaction increases; employees receiving an APF that is highly formalized, job satisfaction decreases. Moreover, we find that employees with a high feedback orientation experience a larger positive effect on job satisfaction in the case of the more open format (lower degree of formalization) as compared to employees with low feedback orientation.

Our study makes three contributions to the literature. First, while previous findings, for example, Boswell and Boudreau (Citation2002), Kampkötter (Citation2016) and Nathan et al. (Citation1991), are based on studies of large organizations that follow formalized performance feedback processes, we have examined the relationship in the context of an SME.

Second, we show that the effect of APF is contingent upon the employee’s feedback orientation, further supporting the conjecture that the effects of performance feedback cannot be thoroughly investigated without considering an employee’s individual needs (Braddy et al., Citation2013; Grubb, Citation2007; Linderbaum & Levy, Citation2010).

Third, our study demonstrates that field experiments can be leveraged even in small enterprises to generate evidence to improve HRM practices. We use a survey field experiment to overcome the limitations of traditional survey and longitudinal approaches (Lee & Son, Citation1998; Nathan et al., Citation1991; Selvarajan & Cloninger, Citation2012). This choice is crucial for several reasons. First, by conducting our research in a natural firm environment, we ensure that our findings are rooted in a real-world context. This enhances the external validity of our findings, making them more applicable and reflective of actual employee behaviors and attitudes in small firms. Second, a key strength of field experiments, and particularly relevant to our study, is the ability to infer causality with greater confidence. By manipulating the timing of performance feedback and observing its direct impact on job satisfaction, we establish a causal relationship that is less amenable to inference by other research designs. Diversity of participants is another key benefit of our field experiment approach. Small businesses often include a variety of employee roles and backgrounds, providing a rich tapestry of perspectives that makes them unique compared to larger firms. This diversity enriches our study by providing a more comprehensive understanding of job satisfaction across different employee demographics within the small business environment. In summary, our research reinforces the importance of field experiments in exploring dynamics within organizational settings. By using authentic responses of employees in small enterprises to performance feedback, our study makes a significant contribution to both the academic literature and the practice of business management.

Based on these insights, we are able to derive practical implications for HRM practices in SMEs, for example, complementing the work from Heilmann et al. (Citation2018). Our findings have significant consequences for the design of APF. First and foremost, companies must be aware that APF always has an influence on job satisfaction, at least in the short term. Furthermore, this study provides evidence that the degree of formalization in the APF session plays an important role for job satisfaction. In contrast to prior findings, showing that highly formalized conversation should actually give the employee particularly precise feedback with a positive on job satisfaction (Latham et al., Citation1993; Murphy & Cleveland, Citation1995), we find the contrary. A highly formalized APF has a negative effect on employees’ job satisfaction in the SME context. By committing themselves to the APF in written form (that is, signing the evaluation sheet), employees might automatically link it with promotion and monetary outcomes. This can cause disappointment afterward or fear and anxiety. The results by Kampkötter (Citation2016) point in a similar direction. He stressed that performance feedback with monetary outcomes leads to higher job satisfaction, and performance feedback without any monetary outcomes can be detrimental. He indicated that this type of performance feedback raises expectations, and organizations “may then be better off without performance feedback processes that give feedback but no rewards” (Kampkötter, Citation2016, p. 767).

Similarly, our results can be linked to prior studies arguing that the introduction of formal HRM practices is likely to affect small business advantages such as flexibility and informality negatively, which small businesses should rather take full advantage of (Bryson & White, Citation2018; Heilmann et al., Citation2018; Kaman et al., Citation2001). While SMEs with a minimum of formal HRM practices usually have highly motivated and satisfied employees, employees’ motivation decreases with the introduction of HRM practices especially when based on extensive formal procedures (Adler & Borys, Citation1996; Bryson & White, Citation2018; Kaman et al., Citation2001). Following Bryson and White (Citation2018), Kalleberg and Buren (Citation1996), Kaman et al. (Citation2001) and Li and Rees (Citation2020), this can be attributed to the fact that with formal HRM practices, employees’ feeling—for example, in relation to participation, autonomy, information sharing, and open communication—decreases. Thus, SMEs are advised to not give up their advantage to provide a participatory, flexible and informal work environment that allows for an open dialogue. These satisfying conditions from an employee’s perspective are highly at risk—when introducing, for example, too rigid performance feedback systems—and employees’ job satisfaction may vanish as a result. In an era where digitalization is continually advancing, there exists the potential for performance feedback systems to reach new levels of sophistication. This technological progress might lead managers to favor highly formalized and standardized performance metrics over informal and interactive feedback as the foundation for Annual Performance Reviews (APRs). These metrics may reflect a high degree of accuracy and reduce perceived supervisors“ subjectivity, but fail to recognize that the exchange between supervisor and employee serves other purposes (for example, mutual involvement and coaching) which are essential for employees” satisfaction (Grubb, Citation2007; Lee, Citation2006). Preserving an informal and participatory approach will become even more important in the future.

Limitations and future research

Despite the insights provided in this study and the advantages of experimental survey studies, some limitations regarding the direct comparison of APF with a low degree of formalization and APF with a high degree of formalization need to be addressed.

Employees differ between the two groups. We observe that employees receiving APF with a low degree of formalization are older (p = .040, MWU-test), more likely to be male (p = .001, chi-squared test), earn a higher income (p = .003), and perceive their job as more secure (p = .0001, MWU-test) than employees receiving APF with a high degree of formalization. Although in principle, it would be possible to control for these differences in regression models, it might well be that the employees differ on other unobservable characteristics of employees, and it is clear that their assignment to the corresponding feedback group is nonrandom.

As we know from the literature on performance feedback, greater latitude for supervisors can lead to subjectivity and favoritism in APF (Frederiksen et al., Citation2017, Citation2020). Of course, this cannot be ruled out in principle. However, in our study we did not find evidence for this.

Moreover, annual performance feedback sessions are conducted by two different supervisors. Although they receive similar leadership training, it might well be that the way they interpret their leadership role differs and might confound our observations comparing APF with a high degree of formalization and APF with a low degree of formalization. Since the supervisor for each group remains the same between the treatments, the effects of receiving feedback on job satisfaction are sound, directly comparing APF with a high degree of formalization and APF with a low degree of formalization need to be interpreted with caution.

In addition, the fact that our study was performed in a German SME implying that the SME with 386 employees is larger than the usual 250 employee threshold used in the broader European context, might limit the generalizability of our results. While this potential limitation is inherent in field experiments in general, the presented causal effects should be—if at all different—even stronger in smaller enterprises. Given that the informality tends to be lower in smaller enterprises, the perceived mismatch between highly formalized APFs and the more flexible interaction between employees and their supervisors should be even more pronounced.

While our study provides valuable insights into the impact of annual performance feedback (APF) on job satisfaction in small firms, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations of the field experiment employed. A first consideration is the nature of our field experiment. Although it was designed to mimic natural conditions as closely as possible, employees were aware that the study was related to job satisfaction. This awareness, although not explicit in the experimental design or its objectives, may have subtly influenced their responses or behaviors. For instance, employees, cognizant of the focus on job satisfaction, might have subconsciously altered their responses due to a response bias. This bias, often stemming from a tendency to project a positive image, might lead to overemphasizing positive aspects of their job satisfaction or downplaying any dissatisfaction, thereby skewing the authenticity of their responses. Furthermore, the knowledge of being part of a job satisfaction assessment could have instigated a behavioral change, akin to the Hawthorne effect (Adair, Citation1984), where employees modify their behavior not because of the actual intervention (the APF in this case) but due to their awareness of being observed or studied. This alteration in behavior could have been both conscious and unconscious, as employees might respond to the implied expectations of the study.

Furthermore, their perception of the performance feedback itself could have been influenced. With the knowledge that their feedback was being particularly noted, employees might have accorded more significance to the APF, or conversely, approached it with a certain skepticism. This altered perception could have a direct impact on how they internalized and responded to the feedback, as well as on their responses in the subsequent survey. While the aforementioned factors—response bias, behavioral changes, and altered perceptions of feedback—are valid considerations, they may not substantially compromise the integrity of our study for two key reasons. First, the randomized nature of the APF inherently reduces the likelihood of these factors uniformly influencing all participants. This randomization ensures that any potential biases or behavioral changes are likely to be distributed across conditions of the experiment, rather than systematically skewing the results in one direction. Second, the study was conducted in a real-world setting, which inherently encompasses and, to some extent, neutralizes these variables as part of the natural dynamics of any workplace. In everyday work environments, employees are frequently subjected to varying degrees of awareness about organizational changes and initiatives, and their responses naturally adapt to these conditions. Therefore, the impact of such awareness in our experiment potentially mirrors the typical dynamics in a workplace, contributing to the ecological validity of our findings. Thus, while these factors are important to acknowledge, they do not significantly detract from the overall validity and applicability of our study’s conclusions.

Another important limitation is communication among employees. In the workplace, it is difficult to completely prevent or monitor discussions among employees about ongoing initiatives. While no formal measures were taken to restrict communication, and management and supervisors did not report any significant discussions about the survey or the APF process, the possibility of informal conversations influencing the experiment cannot be completely ruled out. Such interactions, colloquially referred to as “coffee machine conversations,” could potentially lead to perceptions of being part of an experiment or influence responses to the surveys, albeit to an extent that we believe to be minimal.

Last, the debate regarding the optimal metric for evaluating job satisfaction—whether single-item or multiple-item scales—has consistently been a central discussion in organizational research. In our study, while both measures were employed, our primary analysis leaned prominently toward the single-item measure for the following reasons.

The primary reason behind our preference for the single-item measure was its inherent ability to provide a comprehensive overview on an employee’s job satisfaction. As our research centers around annual performance feedback, covering a range of broad subjects, it was vital to capture an overall sentiment. The single-item measure allowed us to capture this overall sentiment, avoiding possible biases toward any topic or aspect.

In contrast, we recognize the intrinsic depth and granularity of the multiple-item scales. By addressing various dimensions of a construct, these scales provide a nuanced snapshot of job satisfaction. Such depth becomes especially valuable when the aim is to delve into how specific facets of job satisfaction might be influenced by distinct interventions or stimuli. Our supplementary analyses (see Table A6), involving the principal component factor analysis of the multi-item scale, aimed to capture this depth in a singular cohesive metric. While this approach provided additional layers of insight, it is important to note that they are not identical to our initial findings based on the single-item measure. This divergence underscores the complexities and intricacies inherent in these measures and the phenomena they attempt to capture.

Both measures come with their unique sets of advantages and limitations. While the single-item measures provide brevity and a panoramic perspective, they can sometimes be seen as superficial. Conversely, multiple-item scales, in spite of their detailed insights, might introduce challenges like redundancy, respondent fatigue, and potential overcomplication (Nagy, Citation2002; Wanous et al., Citation1997).

In conclusion, our study’s primary inclination toward the single-item measure of job satisfaction was a contextually informed choice, especially in the background of annual performance feedback. By also venturing into the multiple-item scale, we hoped to offer a richer, albeit occasionally divergent, perspective, thereby enriching the ongoing discourse in organizational research.

Despite these limitations, which at the same time provide fruitful avenues for future research endeavors, this paper provides an essential step toward understanding the relationship between APF and job satisfaction. Moreover, it introduced an important boundary condition on the employer side, that is, the formal structure of the performance feedback, as well as an essential moderator (feedback orientation) on the employee side.

A first avenue that warrants further exploration in the context of performance feedback and employee satisfaction is the role of employee expectations. In general, we know that companies are prepared to take action if performance is below their expectations (Cyert & March, Citation1963; Kuusela et al., Citation2016), that poor performance requires change (Zhang & Rajagopalan, Citation2004) and that in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in particular, they are also extremely proactive in this change (Umans et al., Citation2023).

It is also plausible that in some settings, particularly in SMEs that have not historically used formal appraisal methods, the shift to formal performance appraisal may alter employee expectations. Previous literature suggests that unmet expectations, especially when they involve significant departures from previously established norms, can lead to negative outcomes, including lower job satisfaction (Bezdrob & Šunje, Citation2021; Irving & Hansen, Citation2010). In our study, our design ensured that employees’ expectations of feedback remained consistent because we did not examine the transition from high to low feedback formalization or vice versa. The company in our study had established the formats of providing APF either with a high or low degree of formalization in the two groups long before our study took place.

Instead, our study focused on measuring satisfaction before and after feedback was provided, while contrasting employee responses to two different levels of feedback formalization. This design minimized the potential confounding influence of changing employee expectations. However, the broader organizational context offers a rich tapestry of factors that can shape employee reactions to performance feedback. Indeed, the alignment (or misalignment) between employee expectations and the chosen feedback method may be an important determinant. Organizations contemplating a change in feedback methods, especially one that departs from established practices, may need to carefully manage employee expectations. Such management could include clear communication, training, or gradual introduction of new feedback methods to ensure that the transition is smooth and employee satisfaction is maintained.

Introducing a new feedback mechanism within companies brings opportunities for growth and improvement, yet it is important to acknowledge that such implementations can also introduce a host of challenges. One prominent challenge is resistance to change among employees. People often become accustomed to existing feedback processes, and the introduction of a new mechanism might be met with skepticism, reluctance or lack of motivation (Katz & Ellen, Citation1982; Szulanski, Citation1996). Overcoming this resistance requires clear communication about the benefits and rationale behind the new approach, along with providing adequate training and support to ensure a smooth transition (Björkman & Lervik, Citation2007). Inconsistency in the application of the new feedback mechanism is another hurdle that companies might face. Different teams or managers might interpret the guidelines differently, leading to uneven experiences for employees or a feeling that the practices have been forced upon the employees (Björkman & Lervik, Citation2007). Standardizing the implementation and providing clear guidelines can help ensure that the mechanism is applied consistently across the organization.

A second direction for future research can be drawn directly from our results. As the result of our measurement three months after the formal feedback sessions reveal, the differences in job satisfaction completely vanished (a comparison of job satisfaction between the treatments yield insignificant results; APF with a low degree of formalization: p = .749; APF with a high degree of formalization: p = .634, respectively; MWU test). Although we cannot entirely rule out that external events lead to a change in job satisfaction, it is an open question of how organizations can design APFs that have a lasting impact. The not that long lasting, but positive effect of APF with less formalization could thus encourage managers to give feedback in shorter intervals to maintain the positive effects permanently. This can be implemented easily, especially in SMEs, due to the flatter hierarchies and more manageable organizational size and structure. Thus, future studies could investigate whether shorter feedback intervals and feedback sessions taking place throughout the year (for example, after specific milestones are reached or projects are completed) can lead to a continuous positive effect of APFs.

Third, while our findings illuminate the transient nature of the negative effects of formal performance appraisals, they also open the door to a more nuanced understanding of performance feedback mechanisms. Given that the detriments of formal appraisals dissipate over time, and considering their inherent benefits, an optimal strategy might involve a hybrid approach. Organizations could benefit from integrating both formal and informal appraisals into their feedback processes. For instance, a formal review could be conducted annually, setting clear expectations, aligning individual goals with organizational objectives, and providing an official record of performance. This could be complemented by more frequent, informal feedback sessions, which may address real-time concerns, offer ongoing support, and nurture employee development. Such a combination might serve to harness the advantages of both feedback formats, ensuring a continuous feedback loop while mitigating the short-lived negatives of formal appraisals. By balancing the strengths of each system, organizations can aim for a holistic approach to performance evaluation, fostering both employee well-being and organizational efficiency.

Last, our study focused on the employees’ perspective on APFs and their effect on job satisfaction; we omitted the supervisors. According to Grubb (Citation2007), performance feedback, following a formal structure, discourages leadership behavior. Frederiksen et al. (Citation2020) added several assessment consequences in formalized performance evaluation systems. Therefore, field experiments could be designed that investigate the reaction of supervisors, for example, when highly formalized performance feedback sessions are abolished or the company transitions from a highly formalized to a less formalized type of APF. Moreover, research that investigates both perspectives, supervisors, and employees, would provide further insights into how to optimize a company’s formal feedback settings.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (499.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2024.2326576

Notes

1 While there is no universal definition of what constitutes an SME (Audretsch & Guenther, Citation2023; Zahoor & Al-Tabbaa, Citation2020), we follow the conventional definition of an SME in the German context as being an enterprise with less than 500 employees and less than €50 million in annual sales (Pahnke & Welter, Citation2019).

2 In Figure A1 in the Appendix, we display the original “Annual performance feedback form.”

3 Given our sample size of approximately N = 80, we explored the relationship between potential effect sizes (Cohen’s d) and statistical power. This analysis informs the reader of the potential effect sizes our study is powered to detect. A Cohen’s d of approximately .6 yields a power of 1-β = .75, suggesting that our sample size is adequate to detect medium-sized effects with reasonable statistical power.

4 All constructs we measure and correlations appear in the Appendix in Tables A1, A2, and A3.

5 See Table A4 in the Appendix.

6 All data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors, upon request.

7 Recall that we elicited the observable characteristics almost nine weeks after the APF; thus, it is improbable that our treatment had a lasting effect on the employees’ feedback orientation.

References

- Adair, J. G. (1984). The hawthorne effect: A reconsideration of the methodological artifact. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69(2), 334–345. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.69.2.334

- Adler, P., & Borys, B. (1996). Two types of bureaucracy: Enabling and coercive. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393986

- Anseel, F., Beatty, A. S., Shen, W., Lievens, F., & Sackett, P. R. (2013). How are we doing after 30 years? a meta-analytic review of the antecedents and outcomes of feedback-seeking behavior. Journal of Management, 41(1), 318–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313484521

- Anseel, F., & Lievens, F. (2007). The long-term impact of the feedback environment on job satisfaction: A field study in a Belgian context. Applied Psychology, 56(2), 254–266. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2006.00253.x

- Ashford, S. J., & Cummings, L. (1983). Feedback as an individual resource: Personal strategies of creating information. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 32(3), 370–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(83)90156-3

- Audretsch, D. B., & Guenther, C. (2023). Business economics in a pandemic world: How a virus changed our economic life. Journal of Business Economics, 93(1–2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-023-01135-x

- Becker, B. E., & Huselid, M. A. (2006). Strategic human resources management: Where do we go from here? Journal of Management, 32(6), 898–925. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206306293668

- Behn, R. D. (2003). Why measure performance? different purposes require different measures. Public Administration Review, 63(5), 586–606. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6210.00322

- Bezdrob, M., & Šunje, A. (2021). Transient nature of the employees’ job satisfaction: The case of the it industry in Bosnia and Herzegovina. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 27(2), 100141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2020.100141

- Björkman, I., & Lervik, J. E. (2007). Transferring HR practices within multinational corporations. Human Resource Management Journal, 17(4), 320–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2007.00048.x

- Blinebry, A. L. (2016). The Impact of a Supportive Feedback Environment on Attitudinal and Performance Outcomes [ Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Missouri.

- Bloom, N., Bloom, D., & Reenen, J. (2007). Measuring and explaining management practices across firms and countries. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(2), 1351–1408. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2007.122.4.1351

- Bloom, N., Bloom, D. & Reenen, J. (2007). Measuring and explaining management practices across firms and countries. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122, 1351–1408. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.922368

- Boswell, W., & Boudreau, J. (2002, 03). Separating the developmental and evaluative performance appraisal uses. CAHRS Working Paper Series, 16(3), 391–412. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012872907525

- Braddy, P. W., Sturm, R. E., Atwater, L. E., Smither, J. W., & Fleenor, J. W. (2013). Validating the feedback orientation scale in a leadership development context. Group & Organization Management, 38(6), 690–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601113508432

- Brett, J. F., & Atwater, L. E. (2001). 360 feedback: Accuracy, reactions, and perceptions of usefulness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(5), 930–942. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.930

- Bryson, A., & White, M. (2018). Hrm and small-firm employee motivation: Before and after the great recession. ILR Review, 72(5), 001979391877452. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793918774524

- Cappelli, P., & Tavis, A. (2016). The performance management revolution. Harvard Business Review, 94(10), 58–67.

- Carlson, D. S., Upton, N., & Seaman, S. (2006). The impact of human resource practices and compensation design on performance: An analysis of family‐owned SMEs. Journal of Small Business Management, 44(4), 531–543. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2006.00188.x

- Colquitt, J. A., Conlon, D. E., Wesson, M. J., Porter, C., & Ng, K. Y. (2001). Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 425–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.425

- Cunningham, L., & Rowley, C. (2010). Small and medium-sized enterprises in china: A literature review, human resource management and suggestions for further research. Asia Pacific Business Review, 16(7), 319–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602380903115948

- Cyert, R., & March, J. (1963). A behavioral theory of the firm. Prentice Hall.

- Dahling, J. J., Chau, S. L., & O’Malley, A. (2010). Correlates and consequences of feedback orientation in organizations. Journal of Management, 38(2), 531–546. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310375467

- Delaney, T., & Huselid, M. (1996). The impact of human resource management practices on perceptions of organizational performance. Academy of Management Journal, 39(4), 949–969. https://doi.org/10.2307/256718

- DeNisi, A. S., & Pritchard, R. D. (2006). Performance appraisal, performance management and improving individual performance: A motivational framework. Management and Organization Review, 2(2), 253–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8784.2006.00042.x

- Drnovsek, M., Slavec, A., & Aleksić, D. (2023). “I want it all”: Exploring the relationship between entrepreneurs’ satisfaction with work–life balance, well-being, flow and firm growth. Review of Managerial Science, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-023-00623-2

- Dusterhoff, C., Cunningham, J. B., & MacGregor, J. N. (2013). The effects of performance rating, leader–member exchange, perceived utility, and organizational justice on performance appraisal satisfaction: Applying a moral judgment perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 119(2), 265–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1634-1

- Elicker, J. D., Levy, P. E., & Hall, R. J. (2006). The role of leader-member exchange in the performance appraisal process. Journal of Management, 32(4), 531–551. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206306286622

- Fletcher, L., & Robinson, D. (2014). Measuring and understanding engagement. Employee Engagement in Theory and Practice, 01, 587–627. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203076965

- Frederiksen, A., Kahn, L., & Lange, F. (2020). Supervisors and performance management systems. Journal of Political Economy, 128(6), 2123–2187. https://doi.org/10.1086/705715

- Frederiksen, A., Lange, F., & Kriechel, B. (2017). Subjective performance evaluations and employee careers. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 134, 408–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2016.12.016

- Gaile, A., Baumane-Vītoliņa, I., Kivipõld, K., & Stibe, A. (2022). Examining subjective career success of knowledge workers. Review of Managerial Science, 16(7), 2135–2160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-022-00523-x

- Giles, W. F., & Mossholder, K. W. (1990). Employee reactions to contextual and session components of performance appraisal. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75(4), 371–377. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.75.4.371

- Green, C., & Heywood, J. (2008, 02). Does performance pay increase job satisfaction? Economica, 75(300), 710–728. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0335.2007.00649.x

- Greller, M. (1978). The nature of subordinate participation in the appraisal interview. Academy of Management Journal, 21(4), 646–658. https://doi.org/10.2307/255705

- Grubb, T. (2007). Performance appraisal reappraised: It’s not all positive. Journal of Human Resource Education, 1, 1–22.

- Harrison, G., & List, J. (2004). Field experiments. Journal of Economic Literature, 42(4), 1009–1055. https://doi.org/10.1257/0022051043004577

- Heilmann, P., Forsten-Astikainen, R., & Kultalahti, S. (2018). Agile HRM practices of smes. Journal of Small Business Management, 58(6), 1291–1306. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12483

- Hornsby, J., & Kuratko, D. (1990). Human resource management in small business: Critical issues for the 1990s. Journal of Small Business Management, 28(1), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225870002500103

- Irving, P. G., & Hansen, S. (2010). Met expectations: The effects of expected and delivered inducements on employee satisfaction. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 82(2), 431–451. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317908X312650

- Ismail, Y., Hashim, J., & Hassan, A. (2016). Formality of hrm practices matters to employees satisfaction and commitment. Journal of Human Resources Management and Labor Studies June, 4(1), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.15640/jhrmls.v4n1a2

- Jawahar, I. M. (2006). Correlates of satisfaction with performance appraisal feedback. Journal of Labor Research, 27(2), 213–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-006-1004-1

- Kalleberg, A., & Buren, M. (1996). Is bigger better? organization size and job rewards. American Sociological Review, 61(2), 47. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096406

- Kaman, V., McCarthy, A., Gulbro, R., & Tucker, M. (2001). Bureaucratic and high commitment human resource practices in small service firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 24(1), 33–44.

- Kampkötter, P. (2016). Performance appraisals and job satisfaction. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(5), 750–774. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1109538

- Kampkötter, P. (2017). Performance appraisals and job satisfaction. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(5), 750–774. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1109538

- Katz, R., & Ellen, T. J. (1982). A knowledge‐based intervention for promoting carpooling. Environment and Behavior, 27(5), 650–678. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916595275003

- Kaymaz, K. (2011). Performance feedback: Individual based reflections and the effect on motivation. Business and Economics Research Journal, 2(4), 115–134.

- Keeping, L. M., & Levy, P. E. (2000). Performance appraisal reactions: Measurement, modeling, and method bias. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(5), 708–723. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.5.708