ABSTRACT

Qiaopi, remittance family letters that maintained networks between overseas Chinese and their families and relatives in China in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, have been recognised since 2013 by UNESCO as a ‘Memory of the World’, a piece of documentary heritage. Qiaopi have become a subject of prolific research in recent years, especially among historians. In this article, I attempt to explore what kind of resource—ethnographical, methodological, or moral—qiaopi letters as a ‘Memory of the World’ represent anthropology. To examine the world value of the qiaopi archives beyond their ‘function’ as cultural constructions of collective memory, this article places individual experience as a focus of concern upon three cosmopolitan stands to examine qiaopi family networks: (1) ethnographically, qiaopi are scrutinised as an individual practice stemming from a universal human truth for homing, insofar as they serve to articulate family networks across two disjointed worlds; (2) methodologically, qiaopi are read beyond their genre of expression with the approach of cosmopolitan interiority, in order to resonate the shared human affects that are felt in-between the lines of qiaopi letters; and (3) morally, to restore individual expressions within qiaopi family networks—including silences that are beyond expression and those lost in transition—with the aim of avoiding reinforcing discourses that seek to reduce the individuals into categorisations under cultural totalism.

Introduction

Qiaopi are remittance letters resulting from communication between Chinese migrants overseas and their families in China … Recently, qiaopi archives have successfully been included in the Asia Pacific Memory of the World register—some 170,000 items of personal correspondence tracing the fortunes of Chinese emigrants to South East Asia, Oceania and America in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The next goal is to be included in the Memory of the World Register next year … in order to reveal the value of qiaopi culture to the whole world.

It is a hot and humid summer evening in South China. I hear this commentary in ChaoshanFootnote1 dialect on the most popular local daily TV programme. Grandma Chang (my key informant, in her eighties) is watching the programme in her room, as this is one of her daily routines. When I step into her room and smile at her, I see that her eyes are glistening with tears. Immediately I feel that her response to the news with tears is somewhat incongruous with the expressive and excited voice of the anchor, who is using words like ‘successfully’ and ‘next goal’. Seeing Grandma Chang’s tears as they start to drip down her cheeks, for a fleeting moment, I find that this piece of news from such a popular local TV programme has far-reaching implications. To millions of older people in the Chaoshan region who are families of overseas Chinese like Grandma Chang, such news or even just the word qiaopi being broadcast in the news is emotionally fraught. They have an intimate relationship with qiaopi. Qiaopi were part of their everyday lives in the past: from anxiously awaiting a piece of qiaopi with remittance for the survival of their families to reading a piece of a qiaopi letter with joyful tears or sadness.

Yet, in such news, qiaopi are typically represented as a ‘shared’ or collective memory. The curator of the Qiaopi Archive in Shantou has just announced on the television that, ‘The uniqueness, authenticity and irreplaceability of qiaopi qualify them to be part of our collective heritage, our shared memory’. How? I say to myself. Since one’s memory is embodied in one’s mind, where does shared memory reside? Whose memory are we talking about when we talk about the ‘Memory of the World’? I wonder …

Field notes 2012-7-2, Shantou, China

[Qiaopi] record first-hand the contemporary livelihood and activities of Overseas Chinese in Asia, North America and the Oceania, as well as the historical and cultural development of their residing countries in the 19th and twentieth century. They constitute evidence of the Chinese international migration history and the cross-cultural contact and interaction between the East and the West. (UNESCO Citation2013)

The qiaopi-delivery business proliferated along with and in response to the large-scale waves of Chinese migration. It began with privately arranged remittance deliveries by individuals called shuike (couriers by sea). Later, it came to resemble a more formal postal service, operated by privately-owned overseas Chinese remittance bureaus. Eventually, it was incorporated into the Chinese national banking system in 1979.

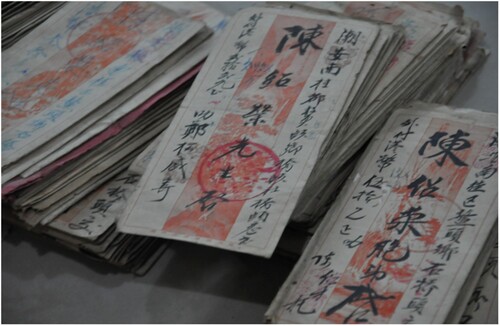

Nowadays, the qiaopi correspondence has faded away. Most of the surviving qiaopi have been collected and preserved by archives in Guangdong and Fujian in South China. The preservation and collection of tens of thousands of qiaopi in specially constructed archives and museums, together with the reconstruction of historical sites and newly built qiaopi theme parks, as well as various forms of media coverage, including local and national TV programs, represent the constitution of forms of collective consciousness and shared memory (See ).

If memory is an embodied phenomenon that is both individual and personal (Berliner Citation2005; Lambek and Antze Citation1996; White Citation2000), what does it mean when we talk about shared memory? How can the individual embodied memories of past practices associated with qiaopi production, transmission, and reception—such as a migrant’s experience of writing or sending qiaopi, or a family member’s anticipation, receipt, or reading of qiaopi—offer novel value in the present and future for a global audience? Moreover, what qiaopi means for Grandma Chang is very different from what it means to me, and it could be different for a global audience for whom the term may have very little cultural resonance. In my case, I do not possess any personal recollections directly linked to qiaopi. However, my grandfather shared with me stories about his siblings, who migrated to Thailand (xianluo fankeFootnote3) and how they used to send qiaopi home almost every month. These stories transport us back to an era long before my own birth, a time when it was a rarity for them to return to China, particularly before the 1980s. Although I never encountered these events firsthand, my emotional connection to qiaopi finds its origins in my childhood memories of the periodic homecomings of the fanke (my grandfather’s siblings) from Thailand. During their visits, they invariably bore gifts for us youngsters, including toys that were deemed cutting-edge for their time, such as remote-control helicopters and robot playthings. I distinctly recall the immense joy of showcasing and sharing these novel toys with my schoolmates; it made me feel as if I were radiating happiness. In addition to these gadgets, they also brought hongbao—red envelopes containing money, as well as clothing, typically second-hand. I still reminisce about the sheer delight of rummaging through stacks of these exotic Thai garments, which invariably carried a distinct, intriguing aroma of perfume. Trying on these dresses was an incredibly enjoyable experience, and even today, the euphoria of those moments remains vivid in my memory.

In this particular case of qiaopi, we are compelled to ponder, whose memories are encompassed within the esteemed ‘Memory of the World’? What precisely does qiaopi, recognised by UNESCO as documentary heritage, signify as a ‘Memory of the World’? These inquiries prompt us to unravel the process of heritagisation and the construction of heritage and collective memory. Laurajane Smith argues that heritage is not an inherent reality but rather a result of discursive practices that serve cultural and political functions. As she puts it, ‘there is no such thing as heritage’ (Citation2006, 13). Smith posits that international heritage practices, such as those employed by UNESCO, excessively rely on established frameworks within the ‘authorized heritage discourse’, which presupposes that heritage inherently reflects national identity (Citation2006). According to Smith (Citation2015), definitions and ideas of heritage, as developed by national and international agencies like UNESCO, require critical examination and reassessment. Rodney Harrison (Citation2012) also challenges and reconsiders the connection between heritage and nation-building, contending that multiculturalism and diversity must be actively fostered rather than passively acknowledged as part of cultural heritage traditions. In this article, through the lens of qiaopi as a UNESCO-designated documentary heritage in the ‘Memory of the World’, I aim to disrupt and challenge the categorisations of heritagisation propagated by UNESCO, while reevaluating assumptions about migrant history. Furthermore, I seek to explore methodological concepts and approaches that extend beyond dominant socio-cultural and national discourses, transcending stereotypical categories of personal experience.

In particular, after describing how qiaopi culture has been constructed and represented in the hometowns of the Overseas Chinese in the first part of this article, I then shift the focus away from disembodied cultural constructions of collective memories of qiaopi towards individual embodied qiaopi practices, exploring what we can learn from qiaopi beyond their serving as representatives of a broader culture. Adopting a cosmopolitan perspective to approach migrants’ experiences, as Anne Sigfrid Grønseth (Citation2013, 6) points out, offers ‘a keyhole into a shared and reciprocal existential humanness that bespeaks a cosmopolitan morality of responsibility and solidarity with all human beings’. Cosmopolitanism, originating from the Greek combination of ‘cosmos’ and ‘polis,’ denotes the integration of engaging with the universal sphere (‘cosmos’) alongside active involvement in local community life (‘polis’) (Rapport Citation2007). It is an approach in which the ethnographic focus of anthropology is not culture but ‘Anyone’, the universal and yet individual human being (Rapport Citation2012). I investigate the ontology of qiaopi by scrutinising an individual’s qiaopi practice of homing and the crafting of a migrant family network, acknowledging migrants as individual letter writers, and writing letters while authoring their identities and their own lives (Gerber Citation2006). These qiaopi, I argue, not only provide us with a glimpse into the specific experiences of individuals, but they also bear witness to the human condition, where love and longing coexist with the ache of distance and the yearning for reunion. They possess the potential to shed light on broader aspects of the human condition that may resonate universally. Finally, I highlight the moral implications of emancipating individual experiences from a reductive categorisation and collective representation under cultural totalism. In doing so, I seek to connect the ‘Anyone’ of ‘a global audience’ with the shared human affects articulated and felt between the lines of qiaopi, and therefore to refresh its meaning in terms of being a ‘Memory of the world’.

In recent years, Qiaopi have become a subject of extensive research, especially among historians (significant works include Liu and Benton Citation2016, Citation2018; Benton, Liu, and Zhang Citation2018; Harris Citation2015; Liu and Zhang Citation2020). In this article, I attempt to explore what kind of resource—ethnographical, methodological, or theoretical—qiaopi letters as a ‘Memory of the World’ represent anthropology. This research is based on fieldwork and an archival study of qiaopi in Guangdong, China from 2011 to 2013, two follow-up visits in 2017 and 2019, and a phone interview conducted in 2020. I mainly conducted my fieldwork in the Chaoshan region of north-eastern Guangdong, a region that is the original homeland of approximately eight million Chinese diaspora (Huang, cited in Wang Citation2020, 127). I carried out archival research at the Shantou Qiaopi Museum and made visits to the homeland village of some qiaopi authors in order to collect oral history. During my fieldwork, I also conducted a research visit to qiaopi museums in the Wuyi areas in Guangdong, China.

Part I. Collective Memory of Qiaopi and Cultural Identity

From Folk Literature to Ritual Celebration

Long before qiaopi were recognised as part of the UNESCO ‘Memory of the World’ heritage in 2013, the expression of qiaopi culture had existed in various forms in the living society of the hometowns of the Overseas Chinese in South China for many decades. Like in the Chaoshan region, local ballads as folk literature demonstrate to us the historical migration and the collective memory of qiaopi:

[1]

A full boat of tears, a full boat of men;

One travels overseas just with a scrap of a wash-cloth.

Do not just send money back but also yourself;

Do not forget your parents and your wife in the bridal chamber.

[2]

A piece of qiaopi, two yuan of note.

Asking my wife:

to work hard and do not worry,

to nurture the children and warn them not to gamble,

to farm the field and feed the pigs.

I will return home to a reunion as soon as I make good money.

Besides these popular ballads, qiaopi continue to have relevance in the daily lives and ritual celebrations of the Chaoshan people. On the seventh day of the first month of the lunar year, Chaoshan people perform a traditional ritual: buying and cooking seven different kinds of vegetables and then eating them with all of their family. Over the course of my fieldwork, this story from Chaoshan folklore was frequently narrated to me:

There was an old man in Chaoshan, whose son migrated to Southeast Asia on the seventh of the first month of the lunar year and did not return for many years. The old man missed his son so much that every year on that day, he always added one more pair of chopsticks while setting the table, waiting for his son to come home. One year, because he had no money to buy any food, the old man picked up seven kinds of residual vegetable leaves from a vegetable stall for free and got back home to cook them together, and put them on a table. He added one extra pair of chopsticks as usual. Right at that moment, a pijiao (qiaopi deliverer) arrived and passed him a piece of qiaopi from his son with remittance. From that year, the date (the seventh day of the first month of the lunar year) has been called and celebrated as the ‘Seven-vegetable Festival’.

The Construction of Qiaopi Museum

In recent decades, as part of the campaign to get qiaopi recognised as part of the UNESCO ‘Memory of the World’ heritage, local governments, private collectors, and qiaopi scholars from Fujian, Guangdong, and Overseas Chinese communities all over the world have worked together to ‘rescue’ qiaopi through preservation and improved access (Liu Citation2014). Together with the boom in Overseas Chinese Museums in post-Mao China (Wang Citation2020), qiaopi are ‘constructed’ as huaqiao (Overseas Chinese) wenwu (cultural relics), archived in Qiaopi museums. As Cangbai Wang points out in his new book on museum representations of Chinese diasporas, his fieldwork observations helped him realise that ‘what is called huaqiao wenwu is a cultural invention of early twenty-first-century China’ (Wang Citation2020, 2).

Take the Qiaopi Wenwu Guan (Qiaopi Cultural Relics Museum, usually referred to as ‘Shantou Qiaopi Museum’) in Shantou as an example.Footnote4 From the 1990s onwards, in the Chaoshan region in Guangdong, private individuals began collecting qiaopi, initially because of their interest in the stamps on the documents. Later they realised the historical value of the letters’ contents. In 1994, the Chaoshan History and Cultural Research Centre started to collect, organise and preserve qiaopi, either from uncompensated donations or through the purchase of family collections. The Qiaopi Wenwu Guan in Shantou was founded in April 2004 and is located within the building of the Chaoshan History and Cultural Research Centre. In 2010, the Chaoshan qiaopi were recognised as part of the official Chinese archive, belonging to the National Archive Resource system. In July 2013, the new qiaopi Archive was relocated to the old city centre in Shantou, and it now covers an area of 2,000 square metres over three floors and includes four exhibition sections and one archive section.

The first exhibition section, Special Background, consisting primarily of a photographic narrative, presents the hardship faced by overseas Chinese in their journeys by sea, the difficulty of their lives abroad, and their efforts to save every penny for their families in China. Objects that were brought from overseas by shuike (individual couriers by sea) have also been selected to illustrate the hardship of the migration. The second section, Special Operation, is dedicated to showing how the qiaopi business came into being through shuike delivery. Its displays consist of a collection of objects and some early qiaopi from the late Qing dynasty period. The third section, Special Ties, captures the development of the qiaopi business over a century. The fourth section, Special Heritage, documents the recent journey of how the qiaopi archives came to be assessed by UNESCO as part of the world’s documentary heritage.

In the archive section, there are more than 120,000 pieces of qiaopi, including over 40,000 pieces of original manuscripts and other scanned copies. There are piles of published qiaopi anthology, such as the Chaoshan Qiaopi Collection with 72 volumes in the first and the second series and over 60 volumes in the third series. Sourced from over 100,000 pieces of qiaopi, these volumes are compilations of qiaopi copies. Most of the qiaopi were sent by overseas Chinese from Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, the Philippines, and Burma. The principal means of cataloguing is according to the mailing address of the qiaopi recipients, arranged by county, town, village, and then family.

Piles of qiaopi, which had lain shrouded in dust here and there for half a century or more, have now been collected and repurposed as a kind of ‘collective memory’, and are housed in the archive with an outstanding new ‘identity’ as a Memory of the World.

From Regional to National Cultural Identity

The core spirit of ‘qiaopi culture’, the curator of the Shantou Qiaopi Museum neatly highlighted, includes ‘honesty and trustworthiness, hard work and perseverance, the courage of pioneers, and a heartfelt attachment to the homelands of huaqiao (Overseas Chinese)’ (People’s Government of Guangdong Province Citation2020). Stories carrying messages with the rather coherent and thematised qiaopi cultural discourse are told; they are either narrated in specially categorised museum exhibitions or theme park illustrations, carved on the facial expression of sculptures in those historical sites or intoned with expressive voices on popular local television channels and radio programs. In Shantou, the recent reconstruction of historical sites such as the restoration projects of the Shantou Old Community (Sio-kong-ng) and the Zhanglin Old Harbor (Zhanglin gu-gang), and the establishment of qiaopi theme parks including Xidi Park in 2016, are historical landmarks that showcase the Chaoshan emigration history and its regional cultural identity as the homeland of millions of Overseas Chinese. That is, besides open accessFootnote5 to the ‘collective memory’ in the form of the archive buildings and museum exhibitions, qiaopi have also entered into the lives of ordinary Chaoshan people through various forms of ‘emotional remembering’. As Christopher Cheng (Citation2019) argues, qiaoxiang, the homeland of Overseas Chinese, in general, becomes a ‘repository’ or ‘living museum’, serving as an enduring reminder of grassroots-based modernity in China. These take the form of visitors’ interactions and experiences in institutional sites of memory, through which a subjective sense of belonging is created, thereby possibly personalising collective memory (White Citation2000).

On 13 October 2020, Chinese President Xi Jinping visited the Shantou Qiaopi Museum and the old downtown area in Shantou, which has had the effect of ushering in a new boom in the collective memory of qiaopi. No longer merely a regional source of migration history, they have become a symbol of a national patriotic tradition. During his visit, Xi emphasised how qiaopi recorded the difficult entrepreneurial history of the older generation of Overseas Chinese and their strong attachment to their home and nation (People’s Government of Guangdong Province Citation2020). As Wang (Citation2020, 7) argues, ‘history museums have continued to serve as an important vehicle for promoting “patriotic education” and justifying the new political and economic agendas of the party-state in the post-socialist era’.

Yet, the question I continue to ponder remains: how may qiaopi as a ‘Memory of the World’ speak to a global audience, to ‘Anyone’ (Rapport Citation2012), unmarked from the messy reality of identities categorised by distinctions in history, culture, society, nation, ethnicity, religion, class, race or gender? Instead of writing about qiaopi as a collective memory from a disembodied vantage point, the next part of this article takes a phenomenological approach that considers lived experiences of memory (Lambek and Antze Citation1996) by examining qiaopi as a way for individual migrants to write their own memory and author their own identities while crafting their family network.

Part II. A Cosmopolitan Perspective on Qiaopi Family Networks

You are—your life, and nothing else.

Jean-Paul Sartre, No Exit (1944)

Dear virtuous wife:

Please read this letter as if I were in front of you and we were seeing each other. I am truly pleased to read your letter.

Please understand me; I did not send money last time just because I had been too busy working; I do not have any special reasons. Don’t I know that you are a good wife? I asked because now the social atmosphere in China is changing. It goes without saying. I just wanted to encourage you to be patient and tolerant! Please don’t misunderstand it. I did not harbour any evil intentions or suspect you. Moreover, you have been serving my mother well and living a rather simple and frugal life for more than ten years without having any love affair. I truly admire you. Please be patient, as I believe it won’t be too long before our reunion. With regard to myself, I will definitely not create another family here. Please don’t worry about it. In your after-work time, I hope you can take care of my mother for me and nurture our son; it is important.

Let’s talk about other things next time; wishing you happiness and peace.

Zeng, 26 February 1958

Getting to Know Zeng: Qiaopi Archival Fieldwork

While poring over 3000 pieces of qiaopi authored by 45 migrants, Zeng was the first one I came across in my archival research. As soon as I opened the first volume of The Chaoshan Qiaopi Archives Selection (Wang Citation2011) housed in the Shantou Qiaopi Museum, I stumbled upon Zeng’s qiaopi. Zeng’s first qiaopi being collected in the volume marked his arrival in Thailand. This initial qiaopi, known as the ping’an pi (‘safe-and-sound letter’), was a customary expression aimed at reassuring loved ones back home after the migrant reached their destination. As I read his first piece qiaopi, I felt as if I were stepping into his household for the very first time, immersing myself in the essence of his narrative. His words introduced me to his mother, wife, son, and two sisters, making them come alive within the pages. In a way, Zeng’s family became the first household that I virtually ‘met’ within my ‘field site’. With each subsequent qiaopi written by Zeng that I read, the intricate layers of his life unfolded before me. During his time in Thailand, Zeng wrote 110 pieces of qiaopi, which, along with seven replies from his mother and son, have been compiled into a series, Chaoshan Qiaopi Archives Selection, and housed in the Shantou Qiaopi Museum. In the following, I will draw on these 117 pieces of qiaopi as a primary source of ethnographic data.

From his qiaopi, we have learned that Zeng was born in the 1920s in a village in Shantou, China. He left his wife, toddler son, and single mother at home when he migrated to Thailand in 1947, seeking income to support his family through remittances. Zeng embarked on his journey to Thailand when he was around twenty years old and did not return to his home in China until he reached his fifties. During his 26-year stay in Thailand, his primary objective was to send remittances back home every month. However, he encountered challenges in fulfilling this goal, as his qiaopi unveiled the complexities he faced along the way. He faced constant job insecurity, often working as a temporary assistant in a shop owned by his cousin. Zeng’s qiaopi reveal a sense of discontentment, exhaustion, and guilt that frequently plagued him. He made repeated efforts to explain the delays and sought forgiveness and understanding from his family. Moreover, as Zeng spent more than two decades away from home, his relationships, especially with his wife, underwent significant changes over time. Being apart for years proved to be a challenging experience for both Zeng and his wife. The burden of separation weighed heavily on them, leading to worries, anxiety, misunderstandings, and even harbouring suspicions. Patience wore thin, ‘unreasonable’ expectations arose, and a sense of mistrust permeated the lines of Zeng’s qiaopi.

Despite the constant hardships and challenges of upholding a distant marriage—a vast expanse both in the geographical distance and the passage of time—every piece of qiaopi Zeng wrote to his wife began with the tender, yet conventional salutation: ‘Dear virtuous wife: Please read this letter as if I were in front of you and we were seeing each other.’ This commonplace greeting in qiaopi correspondence can be firmly situated within the esteemed domain of classical epistolary traditions prevalent in traditional Chinese communication. In the realm of the classical Chinese epistolary genre, formulaic expressions, exemplified by Zeng’s employment of ‘I truly admire you’ in his qiaopi, were frequently harnessed. These linguistic conventions, governed by norms of language usage, grammar, and etiquette, held very importance. In essence, the act of demonstrating respect and affection through humble and meek language, harmoniously intertwined with the established macrostructure of qiaopi letters, emerges as an integral characteristic defining the qiaopi genre.

In qiaopi writing, the utilisation of specific set phrases and honorific expressions is a prevailing practice, strategically employed to attain particular rhetorical objectives. Spanning from the introductory salutations to the concluding courtesies, the qiaopi genre intricately conveys profound reverence for the elder generation while exuding an aura of respect and politeness in interactions with contemporaries (Chen Citation2017, 4–7). The composition of a qiaopi initiates with the employment of genre-specific salutations. While these customary epistolary expressions may not fully encapsulate the depth and breadth of the qiaopi author’s experiences, they serve as a platform upon which the qiaopi sender and its recipients can engage. Even if minimal sentiment is initially invested in these conventional greetings and formulaic phrases within a qiaopi missive, they lay the foundation for both parties, namely the migrants and their families, to commence a social interaction transcending the constraints of space and time (Chen Citation2017, 5).

Approach to Read Beyond Qiaopi Genre: Cosmopolitan Interiority

As I delved deeper into the ‘field site environment’—after reading around 3000 pieces of qiaopi archives—while getting familiar with the established conventions of the Chinese epistolary genre characteristic of qiaopi, when I re-read Zeng’s 110 pieces of qiaopi, I discovered that I had learned to discern the subtle nuances of his distress and discontent. These unspoken sentiments occupied the realms both within and beyond the written words. Methodologically, to apprehend the unvoiced expressions interwoven in the text, to perceive emotions that transcended the confines of written language, necessitated my role as an ethnographer to intimately ‘follow’ the inner thoughts and feelings of a qiaopi author throughout the trajectory of their epistolary endeavours. But how then should one ‘follow’ the trail left by in letters? The answer, I would argue, is not to be found from the surface of the qiaopi texts themselves but comes from the very process of a reader’ subjective engagement with the qiaopi author’s flow of consciousness. In essence, qiaopi are not seen as inert historical documents merely ‘representing’ a particular culture. Instead, they are read and ‘re-enacted’ (Collingwood Citation1999) as dynamic ethnographic situations that emerged and took shape through the ‘interiority’ (Rapport Citation2008) of their authors. ‘Interiority’, as Rapport (Citation2008, 330) defines, ‘is an individual’s inner consciousness, the continual conversation one has with oneself’. Collingwood (Citation1999) advocates ‘re-enactment’ (a technique of disciplined imagination) as a method to know the interior experiences of historical actors. By active engagement in reading a qiaopi, here we could understand the reading as a historical re-enactment, reconstructing it mentally and performing it again in imagination, in this case, the very process of writing qiaopi—what to write as well as what not to and how to write. That is, we understand (qiaopi) writing as a living process of coming-into-being. In what follows, let me elaborate how a reader may give life to the qiaopi text through ‘re-enactment’ and through the recognition of and acknowledgement of the undercurrent of consciousness beneath the surface of the text by taking a closer look at the piece of qiaopi above that Zeng sent to his wife as an example:

Living in two disjointed worlds, qiaopi were the only means of maintaining a connection with his wife in China. Writing the qiaopi to his wife while thinking of her, Zeng’s mind might have been getting more and more detached from its immediate environs. All the surroundings might have been gradually dissolving into the background while images of his wife would come into the foreground in his mental landscape. He was taking the opportunity of ‘talking’ (in the form of qiaopi writing) to his wife to have a conversation with himself:

He expressed how grateful he was to his wife for taking care of his mother and looking after his son at home, and indicated his admiration for her by pointing out that she had been faithful ‘more than ten years without having any love affair’. He might have been having an argument with himself at the same time, thinking to himself: My wife has also not had an easy time. I should trust her. She is a good wife. I should know that. I shouldn’t create another family here even though it’s been so difficult to be alone here for so long and could not return home. His praise for his wife may have served to take away any excuse to start another family abroad.

He then wrote down ‘I truly admire you’ to reassure himself about any unsettling doubts, both with regard to his wife’s fidelity and his own.

When he was attempting to persuade his wife to ‘be patient’ and to offer her hope for their reunion, part of him might also have been attempting to give hope to his other part that had grown weary of living alone for 11 years.

To further overcome his weariness and lack of hope, he took a chance by making a promise to his wife as well as to himself: ‘I will definitely not create another family here’.

He continued to reassure himself by imploring his wife–‘Please don’t worry about it’.

Zeng’s dialogical relationship with himself that emerges in the course of preparing his qiaopi may be interpreted as a form of his ‘interiority’. As his pen moved, the mental image of his wife became clearer, feelings were sensed, doubts were countered, and promises were made. Self-knowledge, too, also possibly advanced. It was a visit to his interior world. Zeng’s intimate knowledge was expressed through the process of preparing qiaopi. That is, writing qiaopi, then, becomes not just a way of making a home (Chen Citation2013) but also a way of knowing the self. If a home is better understood as ‘where one best knows oneself’ (Rapport and Dawson Citation1998, 9), then for an individual like Zeng, writing qiaopi would experience a process that I call ‘homing’. I use the term ‘homing’ to describe a visit to one’s inner world and gaining knowledge of the self.

Homing, as a deep feeling felt by an individual, is a mental yet bodily state of feeling at home within oneself. Homing might also be considered a human experience that resonates universally. Here, Zeng’s qiaopi not only offer insights into his individual experiences (‘polis’) but also testify to the universal human condition (‘cosmos’), where love and yearning to coalesce amidst distance, expressing the desire for reunion. This cosmopolitan outlook enables individuals to navigate their distinct lives within their particular contexts (‘polis’) while cultivating awareness and admiration for universal human experiences (‘cosmos’). As a method for an anthropological approach to qiaopi, ‘cosmopolitan interiority’ can be understood here as the interplay of the ethnographer and his or her interlocutor; both are ‘cosmopolitan human actors’ (Rapport Citation2012) who together try to give form to each other’s worlds through engagement with the other’s interiority, and in the process, they create new knowledge and new ways of knowing. Yet, it is worth highlighting that employing a cosmopolitan interiority in qiaopi archival research cannot guarantee access to a solid set of knowledge; rather, it implies that research is an iterative and getting-to-know process, as Zeng’s case shows us.

Despite his promise to his wife not to start a new family abroad, Zeng took a second wife in Thailand after about five years he had made the promise not to do so. From that point onwards, for about seven years, no qiaopi were found in the collection that was addressed to his wife in China. Those that have been preserved are only directed to his mother and son. Without a divorce from his first wife in China, he was obligated to fulfil his duties towards both homes, which was a very common phenomenon in the history of Nanyang migration, which Chen Da (Citation1939) called the ‘dual family system’. His life was moving on, new struggles emerged, and his attitude to his wife changed while his self-recognition shifted.

After Zeng’s mother passed away in September 1969, Zeng wrote an emotional letter to his wife in China:

Dear virtuous wife:

Now you are the most senior person at home so you should be in charge of all the things for the household. You should discipline ZS (Zeng’s son), which is crucial. You should also take care of yourself in everyday life. In your last letter, you mentioned that a large amount of money is required for mother’s bai-ri-ji (worship on the first one hundredth day after death), but I don’t think so; please keep it simple and minimize costs. I have attached 300 Hong Kong dollars this time for spending on mother’s bai-ri-ji. Now I am getting old; you should always think twice before spending any money. I myself have been living a very frugal life here!

Let’s talk about other things next time, and I wish you peace.

Zeng, 3 December 1969

Dear virtuous wife:

I have well received your messages in your last letter, but the whole family should not rely on me alone for its finances. ZS is a father now; he should also take some responsibility. I am old now and can’t earn more money through my own business. I now work for others and earn only about 300 Hong Kong dollars per month. … It has cost about 8,000 Hong Kong dollars for ZS’s wedding and my mother’s funeral affairs. I truly think that ZS should work to support the family. My life in Thailand is very hard. I work about 13 h everyday. Physically I am also very thin and weak … Moreover, before ZA got married, I had sent two letters to stop his marriage since he couldn’t even support himself. I told him that life would become more difficult once married. He didn’t believe my words. What’s the point of rushing to have one more generation?

Peace.

Zeng, 12 May 1970

For instance, by examining the common phenomenon of the so-called ‘dual family system’ (Chen Citation1939) through an exploration of Zeng’s interiority as expressed between the lines of his qiaopi writing, we can understand how the dual family implies the migrant’s dual self. We can approach the ‘social phenomenon’ of the ‘dual family system’ with a qiaopi author’s rich and vivid individual feelings to make sense of the struggle, sentiments, love, and desperation of the situation.

It must be noted, however, that employing cosmopolitan interiority as a methodological approach in qiaopi research imposes certain limits and challenges. For example, many qiaopi were not written by the Nanyang migrants themselves, but by daixie (dictation for the illiterate) agents, who wrote qiaopi on behalf of the migrants or wrote qiaopi replies on behalf of the migrants’ families in China. This is because many Nanyang migrants were illiterate or insufficiently skilled in writing to make themselves legible or felicitously adhere to the conventions of the qiaopi genre. For those qiaopi not written by daixie, some are written in a rather unpractised fashion, informally employing homophones drawn from local dialects and containing many infelicities. We know, however, informed by a piece of Zeng’s qiaopi, that Zeng penned qiaopi in his own hand. Whether written by daixie or by an unskilled hand, the ethnographer faces challenges in her efforts to make sense of the qiaopi author’s interiority, as much those that are ‘lost in transition’ must remain silent.

Let me be clear about what I mean by ‘lost in transition’: it is those parts of a message that are not conveyed in a given act of communication. This may include information, experiences, or emotions that are untranslated, untold, unsaid, unwritten, or undocumented in the course of transmitting qiaopi from sender to recipient. For instance, when a migrant asked a daixie to write a message for him, there must have been an oral articulation first of the migrant’s experience and then a rearticulation of his oral speech in the daixie’s written text. Even if a migrant managed to convey what he wanted to write in a felicitous manner, still, crucial content or strong emotions that he was keen to express but chose not to must therefore remain silent. In other instances, the spatial distance between the migrants and their families in China might have contributed to failures in communication between them. In such cases, misunderstandings would occur, proliferate, and possibly produce further failures (of various kinds). As we can see in Zeng’s case, for his family in China, there seems to be little awareness of what Zeng had been experiencing in Thailand, and vice versa. We also must consider those who lost their lives on the journey across the ocean before gaining the opportunity to send even their first qiaopi (ping’an pi, ‘safe-and-sound qiaopi’) home.

Hence, further concerns emerge: can we consider these instances of untranslatability and infelicity as vital components of ethnographic praxis? If so, then what role might those failures in communication play in an anthropological exploration of qiaopi? Might we conceive of limits and impossibility not as a loss or indicative of failure but instead as a way to humbly ground our anthropological knowledge as open and without end? Or should we consider an acceptance of untranslatability as a defining feature of the human condition (Carson, cited in Rapport Citation2015)?

Beyond the Cultural Totalism of Qiaopi: De-label the Individual

Last but not least, why does it matter to approach qiaopi with a cosmopolitan perspective? Besides what I have addressed above as its methodological potential to create resonances for ‘a global audience’ with qiaopi as instances of ‘Memory of the World’, it also has political and moral implications. How might an approach possibly speak intelligibly both to other scholars and its research subjects, to policy and the public without falling into the tautological fallacy of presumed categories?

In many recent research on the historical Chinese Nanyang migration, migrants are labelled as huaqiao (Overseas Chinese) in a predetermined manner embedded within ideologically-loaded discourses where subject identity is defined by patriotism (e.g. Zhang and Huang Citation2016, 100–102; Zhang and Li Citation2016), nostalgia for the homeland (e.g. Wang and Yang Citation2007; Zhang and Huang Citation2016, 97–100), traditional clan culture (e.g. Chen Citation2016 Zhang and Huang Citation2016, 95–97), hardship and ambitions (e.g. Chen Citation2016, 91–92), and good faith within a morality-based credit system (e.g. Chen Citation2016, 92; Jia Citation2016). Due to its teleological framing, most of the findings from qiaopi archival research ultimately reinforce the very socio-cultural or historical discourses from which they emerge. In other words, the migrants’ individual stories drawn from qiaopi letters serve only as evidence to support or explain the dominant (though implicit) assumptions regarding their very framing; that is, they utilise an individual phenomenon to explain the socio-cultural phenomenon within a predetermined framework. It is, a kind of deductive reasoning that presents itself as inductive, empirical scholarship. Such an approach is blind to individual agency and creativity beyond or against the existing socio-cultural discourses in which it is embedded.

The overarching presence of collective memory and any generalisation regarding the representation of the Overseas Chinese must nevertheless take the form of reductive cultural constructions. Studies of qiaopi as documents of migrant identities are no different. Attributions of such a symbolic totality to qiaopi culture ‘negates the infinity of otherness, replacing it with the “solitude” of sameness—as if all were knowable and categorizable in the same way, in one way’ (Rapport Citation2019, 72). It ‘treats as fundamental the practice of cultural traditions and communities defining the identity of their members and the worlds in which they operate’ (Rapport, in this volume). Cultural fundamentalism, as Michael Jackson (Citation2019, 13) put it, ‘provides beleaguered people with a spiritually uplifting and politically powerful sense of shared identity’.

Since there are social or political assumptions attached to a label such as huaqiao (Overseas Chinese), efforts at de-labelling become a means by which to achieve emancipation for an individual from those assumptions. For the migrants, to remove labels is to liberate them from dominant assumptions imposed by the external world, academia, governments, mass media, local populations, and so on. To anthropologists, to de-label is first and foremost a refusal to reinforce existing assumptions, and then, if possible, to challenge those epistemological assumptions. Cosmopolitan interiority as anthropological inquiry (morally) and ethnographic research (methodologically) can be a potential way to disrupt (and potentially to complicate) the dominant narratives of the migrants’ experience, and thus challenge the epistemological assumptions about them.

To sum up this second part of the article, let me get back to Zeng and the crucial decision he made to disconnect himself from the family network he had been diligently crafting for more than 26 years:

To my wife and my son:

Please read this letter as if we were seeing each other. Due to the quantity of gold ornaments I brought back home last year, you must have thought that I have lots saved up here in Siam. In haste, you have started building a new floor! … You are all wrong, however! Last year, I, as a wage earner, had used up all that I had saved over more than twenty years. I am now more than fifty years old. I worry even about myself. My income is inadequate to meet my expenses. How can I have money for you to build a new floor? Please don’t kid yourself.

In addition, is it true that the last time, when my boss returned to China, the whole family, including the kids, visited him with the intention of begging for more gold ornaments and money? … You are all shameless! I felt so ashamed of you when my boss mentioned to me ‘your whole family’s begging visit’. The stuff I had already brought home last year was rather considerable. You are so greedy! …

Let’s talk about other things next time, and wishing you golden peace.

Zeng, 12 July 1974

Conclusion

To conclude, this article presents an example of exploring qiaopi from two different perspectives: as a disembodied collective memory, and a different one from how individuals write their own memories and craft their family networks through qiaopi practice. I elaborate on how qiaopi have been constructed as a collective memory epistemologically in the first part of the article, and methodologically, as a means through which to recover individual yet cosmopolitan interiority in the second part. In attempting to restore individual expressions within qiaopi family networks including those spaces of silence beyond expression and those lost in transition, I argue that we may avoid reinforcing discourses that seek to label individuals with reductive categorisations and resist cultural totalism. Furthermore, this case study of qiaopi with two distinct approaches may offer us a glimpse into the implications of examining networks with a cosmopolitan perspective: to recognise individual members within networks not as a means but as the end of whose existence is for themselves to define, and therefore to foreground how the structural power–the social arrangements, cultural conventions or historical constraints–are interpreted, experienced, and potentially re-constituted by individuals; even the realities of life are not necessarily always smooth, fulfilled, translatable, or to be heard. For those lost in transition, they may exist in personal memory, literature, art, museum exhibitions, or as echoes of history heard in individual imaginations, like a ‘memorable’ moment that I had during my fieldwork when I first visited the Wuyi Overseas Chinese Museum in Jiangmen, China:

I was in the museum, walking through from one exhibition hall to another. Suddenly I turned into a dark corridor. Without any mental preparation, I was immediately horrified by several men dressed in white shirts in this dark, silent and still place. Taking a deep breath, I tried to compose myself before I reopened my eyes to look at them again, carefully. Together with their white shirts, what dazzled my eyes in the darkness was a few white china bowls on the floor, empty, with chopsticks on top of them. I soon realised that this was just a display, demonstrating a scene from a corner in the bottom cabin when xia-nanyang (Chinese labourers migrated to Southeast Asia) in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. There were four clay figures sitting on the floor, all male. Realising that they were just clay figures on display, some of my fear dissipated, but at the same time it stirred my emotions. In this gloomy space the air seemed moist and cold, as if I were in the cabin back then. Very shocked, I ended up sitting down on the floor, leaning on the wall of the pathway, imagining that I was in the cabin, in the limited space of the cabin on a ship for more than a month at sea; hungry most of the time; without a window, light, fresh air, even the space to walk …

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 The Chaoshan region consists of three cities: Chaozhou, Shantou, and Jieyang in Guangdong, China. The term ‘Chaoshan’ is used to describe both the language and culture of this region. As one of the Chinese Han ethnic groups, the Chaoshanese speak the Chaoshan dialect – a member of the Southern Min language family, one of the major subdivisions of spoken Chinese.

2 People from southern Fujian and the Chaoshan region in Guangdong also call qiaopi ‘fanpi’ (foreign letters) or ‘pi’ (letters). Qiaopi are also known as ‘yinxin’ (which literally means ‘money letters’) in the Wuyi areas of the Cantonese-speaking region in Guangdong province in China.

3 Xianluo is the former name of Thailand (Siam) in Chinese and fanke is a common name for Chinese living overseas in Chaoshan dialect; xianluo fanke literally means Thai foreign relatives.

4 I have introduced the Qiaopi Museum in Shantou for ‘Fresh from the Archives’ on Dissertation Reviews, see: http://dissertationreviews.org/archives/10164.

5 Most of the qiaopi in the archive in Shantou are open to the public and researchers; in some circumstances, access to original documents may be restricted depending on the physical condition of the documents.

References

- Benton, Gregor, and Hong Liu. 2018. Dear China: Emigrant Letters and Remittances, 1820–1980. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Benton, Gregor, Hong Liu, and Huimei Zhang. 2018. The Qiaopi Trade and Transnational Networks in the Chinese Diaspora. London: Routledge.

- Berliner, David. 2005. “The Abuses of Memory: Reflections on the Memory Boom in Anthropology.” Anthropological Quarterly 78 (1): 183–197. http://10.1353anq.2005.0001.

- Chen, Da. 1939. Emigrant Communities in South China: A Study of Overseas Migration and its Influence on Standards of Living and Social Change. Shanghai: Kelly and Walsh.

- Chen, Shuhua. 2013. “Making Home Away from Home: A Case Study of Archival Research of the Nanyang Emigration in China.” Durham Anthropology Journal 18 (2): 59–71.

- Chen, Youyi. 2016. “Qiaopi: Chaoren Youxiu Chuangtong Jiafeng de Lishi Jianzheng” (“Qiaopi: The Historical Evidence of Fine Family Tradition of Chao People”).” In The Research on Qiaopi, edited by Jianhuai Chen, 86–93. Guangzhou: Jinan University Press.

- Chen, Shuhua. 2017. “Cosmopolitan Imagination: A Methodological Quest for Qiaopi Archival Research.” Yearbook in Cosmopolitan Studies 3 (1): 1–27. https://ojs.st-andrews.ac.uk/index.php/ycs/article/view/1385.

- Cheng, Christopher. 2019. “Looking Beyond Ruins: From Material Heritage to a Grassroots-Based Modernity in Southern China.” Journal of Chinese Overseas 15 (2): 234–257. https://doi.org/10.1163/17932548-12341403.

- Collingwood, R. G. 1999. The Principles of History: And Other Writings in Philosophy of History. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gerber, A. David. 2006. Authors of Their Own Lives: Personal Correspondence in the Lives of Nineteenth Century British Immigrants to the United States. New York: New York University Press.

- Grønseth, Anne Sigfrid, ed. 2013. Being Human, Being Migrant: Senses of Self and Well-Being. New York: Berghanh Books.

- Harris, Lane J. 2015. “Overseas Chinese Remittance Firms: The Limits of State Sovereignty, and Transnational Capitalism in East and Southeast Asia, 1850s–1930s.” The Journal of Asian Studies 74 (1): 129–151. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911814001697.

- Harrison, Rodney. 2012. Heritage: Critical Approaches. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Jackson, Michael. 2013. The Wherewithal of Life: Ethics, Migration, and the Question of Wellbeing. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Jackson, Michael. 2019. Critique of Identity. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Jia, Junying. 2016. “Yi Tiyiju Wei Ge’an Kaocha Jindai Minnan Qiaopiju Xinyong” (“Exploring the Moral-Based Credit System among Qiaopiju: A Case Study of Tianyiju”).” In The Research on Qiaopi, edited by Jianhuai Chen, 116–127. Guangzhou: Jinan University Press.

- Lambek, M., and P. Antze. 1996. “Introduction: Forecasting Memory.” In Tense Past: Cultural Essays in Trauma and Memory, edited by Paul Antze, and Michael Lambek, xixx–xviii. New York: Routledge.

- Liu, Jin. 2014. “Qiaopi Shenyi Gongzuo Licheng Gaishu’ (‘An Overview of the Process of Biding for UNESCO’s Documentary Heritage Status for Qiaopi’).” In Zhongguo Huaqiao Lishi Bowuguan Kaiguan Jinian Tekan (Commemorative Issue for the Opening of the Overseas Chinese History Museum of China), edited by Zhuobin Li, 203–210. Beijing: Zhongguo Huaqiao Chubanshe.

- Liu, Hong, and Gregor Benton. 2016. “The “Qiaopi Trade and its Role in Modern China and the Chinese Diaspora: Toward an Alternative Explanation of Transnational Capitalism.” The Journal of Asian Studies 75 (3): 575–594. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911816000541

- Liu, Hong, and Huimei Zhang. 2020. “Singapore as a Nexus of Migration Corridors: The Qiaopi System and Diasporic Heritage.” Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 29 (2): 207–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/0117196820933435.

- People's Government of Guangdong Province. 2020. Accessed October 28, 2020. http://www.gd.gov.cn/gdywdt/zwzt/scgd/zjhw/content/post_3101590.html.

- Rapport, Nigel. 2007. “An Outline for Cosmopolitan Study, for Reclaiming the Human through Introspection.” Current Anthropology 48 (2): 257–283. https://doi.org/10.1086/510473.

- Rapport, Nigel. 2008. “Gratuitousness: Notes towards an Anthropology of Interiority.” The Australian Journal of Anthropology 19 (3): 331–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1835-9310.2008.tb00357.x.

- Rapport, Nigel. 2012. Anyone: The Cosmopolitan Subject of Anthropology. Oxford: Berghahn.

- Rapport, Nigel. 2015. “Anthropology through Levinas: Knowing the Uniqueness of Ego and the Mystery of Otherness.” Current Anthropology 56 (2): 256–276. https://doi.org/10.1086/680433.

- Rapport, Nigel. 2019. “Anthropology through Levinas (Further Reflections): On Humanity, Being, Culture, Violation, Sociality, and Morality.” Current Anthropology 60 (1): 70–90. https://doi.org/10.1086/701595.

- Rapport, Nigel, and Andrew Dawson. 1998. Migrants of Identity: Perceptions of Home in a World of Movement. New York: Berg.

- Smith, Laurajane. 2006. Uses of Heritage. London: Routledge.

- Smith, Laurajane. 2015. “Intangible Heritage: A Challenge to the Authorised Heritage Discourse.” La Revista d'Etnologia de Catalunya, en anglès 40: 133–142.

- UNESCO. 2013. “Memory of the World.” Accessed September 11, 2020. https://en.unesco.org/memoryoftheworld/registry/264/.

- Wang, Cangbai. 2020. Museum Representations of Chinese Diasporas: Migration Histories and the Cultural Heritage of the Homeland. London: Routledge.

- Wang, Weizhong, and Qunxi Yang. 2007. Chaoshan Qiaopi Jianshi (Chaoshan Qiaopi History). Hong Kong: Gongyuan chuban youxian gongsi.

- Wang, Weizhong, ed. 2011. Chaoshan Qiaopi Dang’an Xuanbian [1] (Chaoshan Qiaopi Archives Selection [1]). Hong Kong: Tianma Chuban Youxian Gongsi.

- White, Geoffrey. 2000. “Emotional Remembering: The Pragmatics of National Memory.” Ethos (berkeley, Calif ) 27: 505–529. https://doi.org/10.1525/eth.1999.27.4.505.

- Zhang, Jing, and Qinghai Huang. 2016. “Cong Minnan qiaopi lan jindai zhonghua wenhua de kuaguo chuancheng” (“Exploring the Cultural Continuity in Modern China Through the Study of Southern-Fujian Qiaopi”).” In The Research on Qiaopi, edited by Jianhuai Chen, 94–103. Guangzhou: Jinan University Press.

- Zhang, Guoxiong, and Jingyao Li. 2016. “Yuanze yu Shihuai: Dalishi Beijingxia de Geren Minyun—Xinjiapo Huaren Zhengchaojiong Jiashu Jiedu” (“from Grudge to Understanding: The Destiny of an Individual in a Special Historical Period—Correspondence of the Zheng Chaojiao Family from Singapore”).” Paper presented at the symposium on international migration correspondence, jiangmen. Accessed September 20, 2020.