ABSTRACT

This paper is the result of an archaeological survey of what remains of the Romanesque chambers and staircases found within the west front of Lincoln Cathedral. It provides evidence, for the first time, that Remigius had begun to build a symmetrically planned west front, complementing the three arched bays to the west and the arch to the south, with a further one on the north west elevation, not the plain wall and low arch we see today. It is argued that, rather than an example of an early fortified church or lord’s tower, as proposed by some scholars, the Romanesque west front of Lincoln Cathedral has within it evidence of a liturgical architectural form which was to be developed fully in thirteenth century west fronts, most famously at Wells and Salisbury.

There is no façade either on the continent or in England that compares with the early west front of Lincoln Cathedral, its design is unique (Bilson Citation1911, 553; Saxl Citation1946, 105; Owen Citation1994, 18; Pevsner, Harris, and Antram Citation2002, 446) and it is the archaeological examination of certain chambers found within the central core and the north and south returns of the Romanesque west front which is the focus of this paper. There is a debate over which buildings may have inspired Remigius’ west front, recognizable by its expanse of undecorated wide jointed course ashlars with three arches and, to the north and south, a niche. Some scholars see comparisons with the Conqueror’s own church of St. Etienne, Caen (Abbaye-aux-Hommes) which was begun in 1063 and had its preliminary consecration in 1073 (Saxl Citation1946, 107; Fernie Citation2002, 110). Others have identified parallels with the Carolingian westwerk (Saxl Citation1946, 110) and the architecture of monuments such as the Porte-de-Mars, Reims (Owen Citation1994, 20). Quiney’s argument that the west front’s resemblance to a triumphal arch, in particular the Arch of Constantine, Rome, presents further options for research (Quiney Citation2001, 169, 170) is explored later in this paper.

It is not known exactly when Bishop Remigius, who transferred his episcopal church from Dorchester-on-Thames to Lincoln after 1072, began to build his church with its exceptional west front, only that some part of the cathedral, probably the east, was sufficiently completed for consecration in 1092 at the time of his death (see also, Appendix One: The construction and consecration of mediaeval churches). Under Bloet (1092–1123), the second Bishop of Lincoln, it is evident that further work on the west front was continued to Remigius’ design (Taylor Citation2010, 150).

It has been argued that the design for Remigius’ west front was to include towers. Saxl argues that the façade contained the essential features of ‘the Norman idea of the two-tower façade with buttresses’. He illustrated his paper with a reconstruction by Frankl of the first Lincoln façade supporting two high western towers (Saxl Citation1946, 108, 115, 117, figures 9, 10, 12). However, more recent scholars doubt that Remigius intended to include western towers, seeing Lincoln’s western massif as a ‘towerless rectangular block and arguing that if there were western towers they may have been built of timber (Fernie Citation2002, 262; Owen Citation1994, 18) (see also, Appendix Three: The unstable ground conditions of the cathedral site).

The body of Remigius’ church was gutted by fire during Alexander’s episcopy in either 1124 or 1141, Kidson arguing the former date (Owen Citation1994, 22–24). The austere west front favoured by Remigius had not impressed Alexander and, influenced by examples from both England and the Continent, he commissioned the insertion of three new doorways to replace those in the arched recesses. He embellished them with intricate decorative mouldings and above them an elaborately carved frieze (Zarnecki Citation1988, 36–89). It is likely that the Romanesque west front was finally completed during Geoffrey Plantagenet’s office (Bishop Elect. 1173–1183) when he made a gift of two bells for one of the newly completed western towers (Dimock Citation1877, 198). Geoffrey would have also been responsible for the interlaced arcading at the top of the façade and the inclusion of water-leaf capitals on the towers.

In 1185 the cathedral was damaged during an earthquake in which much of Alexander’s church was destroyed with only the west front, along with the newly built western towers remaining (see also Appendix Three: The unstable ground conditions of the cathedral site). It has been accepted that Hugh (1186–1200) began rebuilding the church in 1192; however, Stalley argues that the correct date for the commencement of the Gothic building is 1193 or 1194 (Stalley Citation2006, 144). Fortunately, Hugh decided, perhaps for economy, to keep the central Romanesque core of the west front with its austere five plain arched recesses.

The chambers found within the Romanesque west front at Lincoln

(See also, Appendix Two: The restoration history within the Romanesque west front of Lincoln Cathedral and the drawings of William Lumby.)

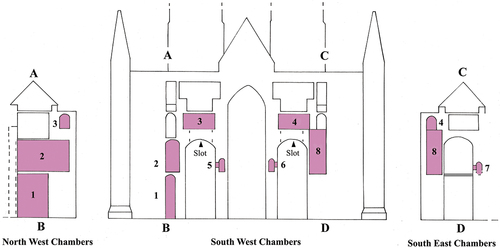

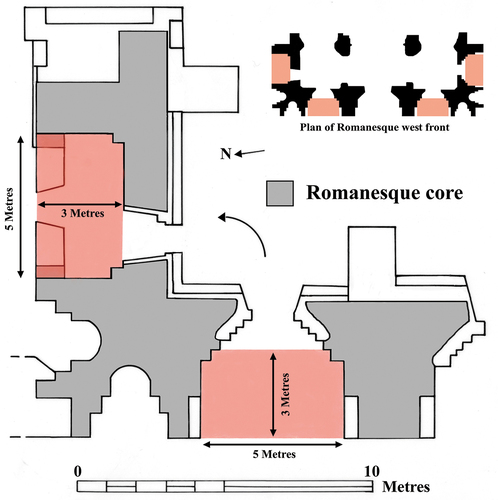

The Romanesque chambers and passageways that remain within the shell of the west front were almost destroyed by later alterations as they were absorbed into the fabric of the Gothic church. Often hard to access, the relationship of chambers to each other then became functionally irrelevant. The arrangement of the passageways and voids can best be visualized as a three-sided rectangular shape with the longest side to the west measuring 34 metres (including the now hidden north and south re-entrant angles), and the two shorter sides, measuring circa 14 metres, to the north and south. is a schematic diagram that shows the location of Romanesque chambers and voids within the west front. The north side houses the North West Chambers, the lower two are the focus of this paper (). To the west, and sitting above the north and south portals, are the Crossing Chambers, their floors penetrated by slots (. Below them, overlooking portals, are the western Buttress Chambers (. To the south east, the South East Buttress Chamber (. In the south western corner of the west front is the great South West Staircase (.

Figure 1. The location of the Romanesque chambers and voids within the west front of Lincoln Cathedral that are the focus of this paper. (1–2) North West Chambers. (3–4) North and South West Crossing Chambers. (5–7) North West, South West and South East Buttress Chambers. (8) The Great South West Staircase.

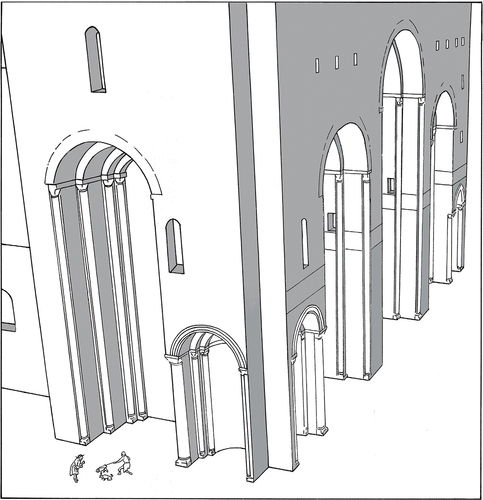

Figure 3. A conjectural reconstruction of the Romanesque Lincoln cathedral showing the North West Arched Bay.

Figure 4. A comparison of the plan of the north bay west front with the plan of the ground floor North West Chamber.

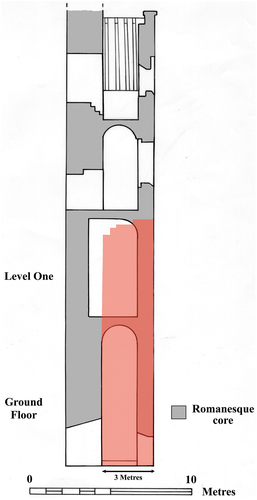

Figure 5. A section of the North West Arch placed within a section of the ground floor and levels one and two of the North West Chambers.

Figure 6. Looking west, a building break in vault of Level One North West Chamber just above the west elevation of the ground floor chamber.

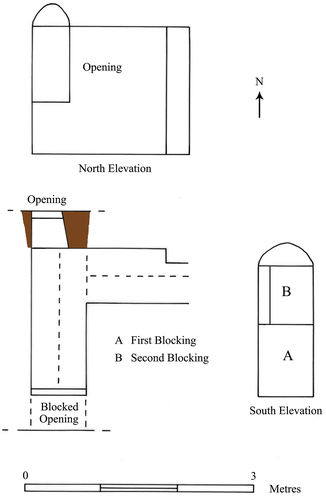

Hidden by the façade and now contained within the Morning Chapel, the north west elevation of the Romanesque core is unique in design and of great interest. To the west is a niche that mirrors those on the west front but following that we are confronted by a plain wall with two windows above and, at its base, a low arch (). The south elevation of the core follows the conventions established on the west front with a niche and embedded in the Ringers’ Chapel, an arched bay and, to the east, the South East Buttress Chamber (, and 2B).

The Romanesque west front of Lincoln Cathedral: the polychromy

It was common for Norman Buildings to be brightly painted (Fernie Citation2002, 280) and Lincoln Cathedral was no exception, Zarnecki commenting that the rough surface of the stone of the Corinthian ‘type’ capitals of the responds in the recesses of the west front may be for a key for a gesso base before paint was applied (Zarnecki Citation1988, 13). There is other evidence that the twelfth century visitor approaching the west front was met with areas of highly coloured and intricately carved sculpture and mouldings. This theatrical backdrop was intended to highlight the practice of the liturgy, most importantly the Palm Sunday procession when Christ's entry into Jerusalem is re-enacted. Running across the west front well within sight and just above the western doors, the band of sculptured panels was painted. Paint fragments taken from the panels from the north run of the frieze have been analysed and have shown that the sculptures were painted with white, yellow, blue, green, red, vermillion, purple, brown and black pigments. The arched recesses around the north, south and central doorways were embellished with decorative mouldings including chevron, fret motif and beak-head ornaments and paint discovered around the north portal suggests that the frieze colours were repeated on the three western doorways (Crawford Citation2013, 198–231, note 28). Other key focal points across the Romanesque west front were probably painted but traces of pigment have not yet been found. Remigius’ and Alexander’s brightly coloured west front was later to become the central part of the Gothic façade and here too there is evidence of extensive painted decoration, including on the capitals and lattice work (Butler and Clark Citation2015, 440). As well as Lincoln, painted areas have been identified in principal areas on the Gothic west fronts of Salisbury and Wells and Exeter cathedrals (Sinclair in Ayers Citation2000, 111–130).

At Lincoln, above the frieze, columns in the bands of blind arcading were of dark grey polished Purbeck marble, their shafts, bases and capitals contrasting with the pale stone behind. Purbeck marble was probably introduced to the west front after 1192 during the building of Hugh’s Choir when the use of quantities of a ‘costly material consisting of black stonework’ is remarked upon (Erlande-Brandenburg Citation2007, 132). Much of the Purbeck marble on the west front of Lincoln has now been replaced with plain stone but it was still a notable feature in the nineteenth century. It is recorded then that ‘the loss of Purbeck on the exterior of the Minster has been very great’, and that its frequent collapse often made the west front dangerous to approach (Buckler Citation1866, 66).

Other features of the early Romanesque west front: the ground floor and level one of the North West Chambers as an arched bay

It is remarkable that, to date, little comment has been made about the eccentric construction of the north elevation and the lower North West Chambers and how they fit uncomfortably within the plan of Remigius’ west front. The otherwise symmetrically planned west front with its three arched bays to the west and an arch to the south is noted by scholars but descriptions of the chambers and the low arch of the north west elevation is limited to their possible function as a garderobe, not to their incongruity. Only two writers state the obvious. Venables notes that ‘the loftier recess (is) not found on the north side’ (Venables Citation1883, 171) and Nicholson, after describing the ‘deeply recessed porches’ found at the west, continues with ‘the northern one (elevation) was not hollowed out into a porch’ (Nicholson and Fox Citation1926, 159).

This survey argues, for the first time, that Remigius had planned to build an arched bay that echoes those to the west and south of the west front on the north west side (). Measured drawings of the Romanesque west front and photographs hold clues to the builders original design. A scaled plan of the north west (or the south west or south east) bay superimposed within the plan of the North West Ground Floor Chamber fits remarkably well. At specific points, the width and depth of the North West Ground Floor Chamber and the north west bay are similar, and they both share the position of a pilaster/column base (). Further, a section of the north west bay superimposed within a section of the North West Chambers arch fits exactly under the Level Two Chamber and shares the south wall of the Ground Floor Chamber (). Also, within the line of the proposed arch, examination of the vault of the Level One Chamber reveals a building break directly above the west wall of the Ground Floor chamber ( and ).

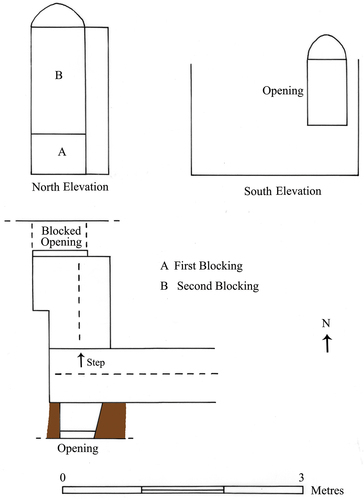

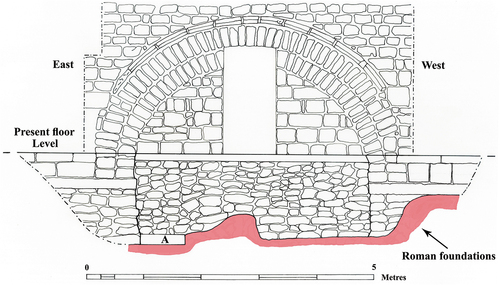

Archaeological evidence suggests that Remigius and his builders abandoned the construction of the north west arched bay due to underlaying features from a previous structure on the site. Pearson records that he instructed the Clerk of Works, John Smith, to dig a series of test pits ‘to determine the nature of the ground the west front sits on’ (Pearson 1874, 14, D&C ARK22/12). One of the excavations was in the Morning Chapel floor up against the arch in the wall of the Ground Level Chamber. Venables, who makes a brief comment on the excavation in his account of the cathedral published in 1883, reports that Smith’s excavation revealed that ‘a Roman base moulding was discovered with three steps and other fragments of a Roman building, and further comments “which the Norman workmen, found it easier to bridge over than to remove” provides a plausible explanation for the form of the north wall. Venables describes the Norman work as “an arch of construction, thrown across a place where a good foundation could not easily be obtained” (Venables Citation1883, 171). The lower part of is a copy of Smith’s drawing of his excavation against the arch. It shows that the mediaeval builders, faced by the Roman building, built directly on the remains in the west only to discover they dropped irregularly a further metre towards the east and included what Smith describes as an entrance with a set of steps to a building. The mediaeval builders maintained the level of their building by packing out the foundations with rubble. Clearly the Romanesque builders were unwilling to risk raising the massive north side of the west front above an arch on the same scale as those on the west and south side since it would have been over the unconsolidated remains of the earlier building (see also, Appendix Three: The unstable ground conditions of the cathedral site). The builders’ response to the problem was to increase the thickness of the rear wall of the space to make it at least twice as thick as the comparable wall of the arch on the south façade and create a hollow box structure. An arch was erected over the site of the buried remains and the walling above built to its full height.

Figure 9. The south elevation of the Morning Chapel arch including a copy of Smith’s 1877 drawing of his excavation through the chapel floor revealing Roman foundations. (A) ‘The entrance to some building. The fragment of masonry next westward appears to have been for the support of two other steps’.

A south portal to the west front

There may be another architectural feature we can add to Remigius’s west front. Access from the nave to the South East Buttress Chamber was removed during the Gothic rebuilding of the interior west front and the chamber was backfilled, probably in the nineteenth century. Its western opening, which once overlooked the southern arch bay, is now trapped within the Ringers Chapel and the outside of the opening is accessible from the thirteenth century staircase. The western Buttress Chambers openings have a purpose, their view, though limited, overlooks the north and south portals. By association, the opening of the South East Buttress Chamber may be an indication that Remigius’ plan included a door through the southern arch to the nave ((7) and 2B).

The perceived military or castle-like features of the early Romanesque west front

As the archaeological survey progressed it became apparent that the argument made by some scholars that the west front concealed chambers that were originally planned as military or castle-like features was not only unsustainable but ignored other more logical architectural alternatives. The proposition that a church can be defended like a castle is, of course, perfectly acceptable. Any strong, secure building can be used in exigence to repel attack, we have examples today in urban warfare. However, although arrows can be fired through an open space, that does not define it as an arrow loop, nor can the 2 m deep and 30 cm wide slots found above the north and south west portals at Lincoln be defined as having been built as functional machicolations because objects can be dropped through them. At Lincoln we are looking at the primary, not the incidental potential secondary, purpose for certain chambers in the Romanesque west front. Bates is clear about this difference, arguing that, at Lincoln, ‘we must distinguish between a building which might include features typical of fortifications and one which was itself fortified’ (Bates Citation1992, 17).

Discussion of the purpose of the west front occurs in the antiquarian papers of the late nineteenth and early twentiethcenturies (Venables Citation1883, 170; Buckler Citation1866, 181; Smith Citation1905–1906; Fox, in Nicholson and Fox Citation1926, 172). Attention was returned to it in the last quarter of the twentieth century, led by Richard Gem, who proposed a military function for the west block (Gem Citation1986), to be followed by Stocker and Vince, who saw it as forming part of a whole defensive set of buildings on the hilltop and acting as the vestibule to, or actual bishop’s hall (Stocker and Vince Citation1997).

Richard Gem’s paper, with an accompanying drawing of the completed Romanesque front by Terry Ball, were derived from close observation and their interpretation requires careful investigation. Gem confidently identifies Level One and the Ground Floor North West Chambers as a garderobe complex with ‘shoots (that) lead down into the lower chamber which could be cleaned out through the north archway’. The slots that penetrate the soffits below the North and South West Crossing Chambers are presented as ‘pierced machicolations, (and) a feature of great significance’. Further, the windows of the mural chambers of the North and West Buttresses were ‘presumably designed to serve as loops’. He argues that, within the south arch of the Romanesque west front there may have been an external wooden platform below the central window (now blocked) which may have served as a machicolation. Gem is the first to comment that the Daniel panel in the southern length of the Romanesque frieze appears to be inserted into a rectangular blocked opening and argues that it may have led to an external western gallery or fighting platform built for additional defence.

Gem also argues for a second chamber to the east of the North West Ground Floor Chamber and an additional large arch to the east of the South Arch (also with an external wooden platform). This hypothesis is based on his interpretation of a paper by John Smith in which Smith describes what he identifies as a second room at the east end of the Ground Floor Chamber after an excavation he made in the floor of the Morning Chapel. Gem accepts Smith’s observations as correct but, unfortunately, neither he (personal communication 2013), or independently this author, were able to source this or any of the other original notes or sketches made by Smith of this excavation. Without verification, the archaeology is uncertain, and we cannot be sure if what Smith discovered was a wall or part of a foundation, or from what period. For example, this survey has identified above the vaults of the Morning Chapel and directly above Smith’s eastern excavated area, a stub of wall which may have been part of the staircase buttress that once came down from Level Two of the North West Chambers to the nave floor. The staircase is included in Bilson’s plan of the Romanesque church set within Willson’s plan of the cathedral (Bilson Citation1911, plate 77). What Smith uncovered may have been part of the foundation for the staircase.

Gem found evidence for the additional south east bay by turning to test trenches made by John Bilson on the south west side of the aisle in which he uncovered the corner of a wall which he found difficult to account for ‘unless it was an opening in the aisle wall’ (Bilson Citation1911, 552). Gem argues that if the aisle was expanded at this point, it would support his reconstruction of a second bay to the east of the existing one (Gem Citation1986, 12–14, 15, 27, n. 35). This is a big step to take based on such scant evidence. To reflect for a moment on Bilson’s first comment on the confusing archaeology, this could be evidence not for a bay but for an opening out to the south side of the cathedral.

Gem argues that Remigius was motivated to fortify the west front of his church to prevent it from falling into hostile hands. A large, strong, stone building constructed just opposite the castle could be used as a siege work against it (Gem Citation1986, 20, 21). Of course, Gem has the advantage of hindsight, between 1140 and 1145 Lincoln and the castle area were the scene for much violence. William of Malmesbury claims that Stephen fortified the cathedral against the castle, though Henry of Huntingdon makes no mention of the event (Owen Citation1994, 23). However, 70 years before, at the time work on the cathedral had begun, the castle was well-garrisoned and provided with 20 of Remigius’ own knights. After William’s ‘harrying of the north’ and the defeat of Hereward the Wake there is no indication that Lincoln was under threat and after 1072 Remigius was not considered to require a castle guard (Bates Citation1992, 12). Later Alexander was to transfer his military duties to his castle at Newark.

Central to Gem’s argument that Remigius built a defensible west front is a text from Historia Anglorum by the chronicler Henry of Huntingdon (1080–1160) in which he describes the church built by Remigius as a ‘strong church’ which was ‘invincible to enemies’ (Gem Citation1986, 9).

Having, therefore, bought lands in the upper city itself, next to the castle which was distinguished by its very strong towers, he constructed a strong church in that strong place, a beautiful church in that beautiful place, dedicated to the Virgin of virgins; it was to be both agreeable to the servants of God and also, as time went on, invincible to enemies (Greenway Citation1996, 409). (Gem chooses the translation from T. Arnold, 1879 where ‘as time went on’ is ‘as suited the times’ (Gem Citation1986, 26:4).

Gem accepts Henry as a reliable source for the early history of the church and that there is no reason to doubt the accuracy of his description of Remigius’ building (Gem Citation1986, 9). However, Greenway points out that Henry’s Historia Anglorum, including his account of contemporary events, cannot be taken as an objective record. His work embodies a literary trope, a narrative description of events which conformed to what he saw as God’s overall plan and his quotations and allusions are largely biblical. Further, that ‘if we are to understand the text of the Historia Anglorum we need to recognise and filter the embellishing colours of rhetoric’. The prose of the historical books in the Historia Anglorum is, for the most part, influenced by the Psalms. They were central texts to mediaeval Christianity, and it is known that Henry was required to chant Psalm 78 daily and there are echoes of it throughout his written work (Greenway Citation1995, 110, 115; Citation1996, intro. 33, 49). In Psalm 78 a strong God is wrathful against his enemies, the incredulous and disobedient. However, further reading finds several instances where the Psalms can provide a more direct source for Henry’s description of the church at Lincoln. Psalm 18:2 ‘The Lord is my rock, and my fortress, and my deliverer; my God, my strength, in whom I will trust; my buckler, and the horn of my salvation, and my high tower’. Similarly, in Psalm 21:3 ‘For thou art my rock and my fortress’. Again, in Psalm 144:2 ‘The Lord … my goodness and my fortress; my high tower, and my deliverer: my shield’ (King James version). The emphasis on ‘strength’, and ‘fortress’ is surely what Henry was referring to when looking at the massive west front of Remigius’s church.

Stocker and Vince take Gem’s theory for the fortification of the west front further, arguing that Remigius built a two-story defensible great tower separate from the church and they are confident that ‘the archaeological evidence reported by Gem simply cannot be doubted’. They too identify the controversial chambers as a garderobe, accept the machicolations and arrow loops and see the great South West Staircase ‘as an important route way by which the lord would get from the first floor halls to his privy chambers’ (Stocker and Vince Citation1997, 227, 229, 230). With limited archaeological evidence they include hypothetical reconstruction plans of the ground and first floor of the tower. The chambers within the western buttresses are described as T-shaped with close parallels to examples in the White Tower, although, as Gem correctly notes, the Lincoln examples are an inverted L-shape. Examination of the plans of the White Tower shows that the L-shaped chambers found on the first floor are garderobes and on the second floor openings are accessed from a complete circuit of mural passages within the walls (Impey Citation2008). Neither examples share any resemblance to the Lincoln buttress chambers (or the perceived garderobes in the North East Chamber).

The controversial chambers

Moving now to the physical evidence in the building at the present time, the spaces identified as garderobes by Smith (Citation1905–1906, 98), Gem (Citation1986, 14) and Stocker and Vince (Citation1997, 229) need to be considered. Rectangular and orientated east to west, the North West Chambers are located within the north side of the Romanesque western façade ((1–2)). The Ground Floor Chamber () is behind the plain return wall of the north side of the west block and is a windowless enclosed space, 8.75 metres high with a barrel vault penetrated by two stone framed apertures (now blocked). It is accessed by a doorway set within an arch built into the south wall of the Morning Chapel. There is a second doorway from the nave. The chamber has a chamfered plinth to the east, west and south of the chamber, but not the north.

Level One can be identified from the outside by a barred window (blocked behind the glazing) just above the sculptured frieze. The chamber is isolated from other Romanesque features by the void created by the reworking of the façade and the insertion of the fourteenth century north west window. It can now only be reached by ladders from the floor of the nave via the ledge of the window inserted above the portal and then up through a rough entrance in the wall. The average height of the chamber’s barrel vault is 6.0 m. There is a building break in the vault directly above the west elevation of the Ground Floor chamber ( and ). The north elevation at the west end has a window (which has historically been used as a doorway) and to the east is another window blocked by a vault spar built as part of the Morning Chapel ceiling. The south elevation, from the east, has two piers inserted by Pearson to support the failing wall. Towards the south west corner of the chamber are two blocks of masonry, either side of today’s entrance, attributed by Pearson to Alexander’s masons and built to support the staircase in the north-west corner of the north tower. The east elevation has a large window, now blocked, inserted during the twelfth century. The west elevation has a window, again blocked. Within the chamber at floor level are burnt stones up to eight courses high. In the centre of the floor at the eastern end of the chamber are two sets of eight holes drilled through the concrete screed which identify the position of the chutes.

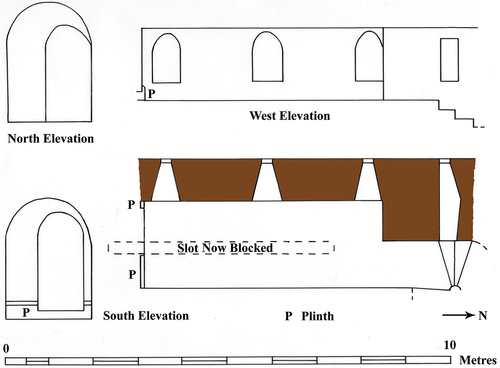

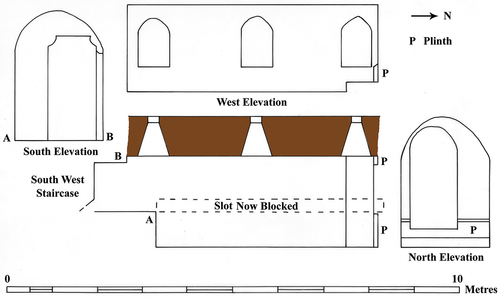

Described by Gem (Citation1986, 19) and Stocker and Vince (Citation1997, 229) as spaces to serve arrow loops, the North, South West and South East Buttress Chambers ( and ) are at the same floor level as Level One, The North West Chambers, and the present foot of the great South West Staircase.

The two western chambers are tucked within the buttresses either side of the central doorway to the cathedral. The north chamber has a window overlooking the north portal () and the south chamber a window overlooking the south portal. Both chambers are 2.5 m in height, an inverted-L in shape, and with a blocked opening facing south and north, respectively, overlooking the central arch and doorway ( and ). Once linked by a horizontal walkway across the inside of the west front, today the western chambers are accessible by intermural staircases from the ledges of the windows inserted above the north west and south west portals. Hidden within the Gothic façade of the Ringer’s Chapel, the western window of the infilled South East Buttress Chamber is accessible from the thirteenth century platform within the southern arch ().

The North and South West Crossing Chambers, identified as having machicolations by Gem (Citation1986, 12) and Stocker and Vince (Citation1997, 227) can be located by their west facing windows in the lower frieze of blind arcading above the left and right portals either side of the central arch ((3–4)). They are accessed from the south from the great South West Staircase then across the nave (‘Bank’s View’) to the northern chamber. The chambers, which are 2.60 m in height ( and ), each have a slot 5 m long and 30 cm wide in the floor (and now covered by concrete) that penetrates between the orders of the soffits of the north and south portals ( and ). Fourteenth century alterations to the central arch caused each slot to be reduced in length by 80 cm.

Comparing Lincoln’s controversial chambers with castle architecture

It is important to remember that Remigius’ west front is early, begun circa 1072, and though unfinished at the death of his successor Bloet, included the controversial chambers (Taylor Citation2010, 150–151). The identification of these features as a garderobe complex, mural chambers with arrow loops, and machicolations is pivotal to those who argue that Remigius built a defensible west front which included a residence. However, as we will see, the archaeological evidence shows the features do not conform to the conventional design for such facilities.

The garderobe chambers

The design of the perceived Lincoln garderobe chambers is unique and there are no parallels to be found in cathedral architecture. The earliest comparative castle examples of garderobes were built 70–80 years after Remigius’ death. They are in Chambois Castle keep, Orne, Normandy, 1165–1190, Middleham Castle keep Yorkshire, from the second half of the twelfth century (), Newcastle Castle keep 1168–1178 (), and Dover Castle keep, 1180–1190 (). There are fundamental differences between the layout of the garderobe suites of the three English castle examples and the first floor chamber at Lincoln (). The castle garderobes are small spaces separated by a passageway from the body of the building and located against an outer wall to allow chutes to discharge through the thickness of the wall, while at Lincoln the space is considerably larger and the ‘chutes’ occupy the centre of the floor at the east end of the chamber. There is no evidence that these chutes were separately partitioned. The castle garderobes each have a window loop directly behind the chute measuring (on average 50 cm at the inner edge and 20 cm at the outer sill). There is one window in the Lincoln chamber that is indirectly associated with a chute and is considerably larger (1.45 mat the inner ledge and 80 cm at the outer edge).

The North West ground floor chamber – the storage area for the latrine?

It is astonishing that no one has commented on the sheer size of the ground floor North West Chamber at Lincoln. The ground floor described by some as the storage area for the latrine has a floor area of 5 mby 1.95 m and its height to the top of the vault in 8.75 m. This would give the chamber a storage capacity of around 85,000 litres. When it was time for the chamber to be emptied the cleaners had an arch 4 m in width and 1.55 mhigh to unblock and work through. Surely, an impracticable and excessively large facility even for a most gregarious and status conscious bishop?

The south elevation of the ground floor chamber includes a doorway from the nave and at least since Smith, the first to publish the argument that the chambers were a latrine (Smith Citation1905–1906, 98), it has been assumed by scholars not to be an original feature. For example, Gem, when defending his garderobe attribution for the chamber, writes that the ‘solid south wall isolated it from the church’ (Gem Citation1986, 15). Examination of the doorway though shows that the argument that it is a ‘post-latrine’ feature is not proven. Restoration work (most probably by Godfrey) has destroyed much of the archaeology of the doorway but there is evidence for an earlier arched doorway, though from which period it is difficult to ascertain.

Since the building of the Morning Chapel in the thirteenth century the hood mould above the southern arch has been redundant. Indeed, one might question why the mould was originally thought necessary (unless just as a decorative motif) if the arch was meant to be blocked (as access to a latrine) for most of the time. Today, in need of repair and missing label stops, the mould sits amongst the restored eleventh century façade above and to the west of it and the twelfth century façade to the east. Lumby was the first to publish a reconstruction drawing of the Romanesque north west elevation of the cathedral which shows that, over the last 230 years, changes have been made to the arch, and the doorway and wall beneath it. Lumby shows the doorway to the ground floor chamber as shorter and not cutting through the voussoirs of the second arch as it does today. In his description of the chamber Lumby comments that ‘the door is so low that one must stoop to go into it’, there is a small slit window either side of the doorway (Lumby Citation1791, 2 plate 10, fig 1). The windows are included in a sketch by Pugin (circa 1820) and in Willson’s 1835 plan of the cathedral. By the time Smith (Citation1877) drew an elevation drawing of the arch only the east window had survived. Today, the windows have gone, though evidence of their position can be found from the chamber side.

The mural chambers with loops

It is argued that the North, South West and, by association, the South East Buttress Chambers were built as mural chambers with arrow-loops but ,when we look to castles for a comparison, we find that arrow loops or slits were developed long after Remigius’ death and are of a specific design. Kenyon agrees that it is in the late twelfth century that loops are introduced in castle architecture (Kenyon Citation1990, 52), with Dover Castle, circa 1185–1190, one of the earliest examples (Renn Citation2011–2012, 175). Arrow loops are described as a tall vertical slit on average 5 cm wide made to give passage of a fletched arrow through the wall and widening inside to an embrasure (Renn Citation2011–2012, 175). The loop should command as wide a view of the exterior as possible enabling the archer to fire down and narrow slots must be designed to prevent enemy archers from easily firing in (McNeill Citation1992, 94, 95). The openings in the L-shaped Buttress Chambers do not resemble the castle loops described above. The rectangular openings overlooking the north and south west portals are, on average, 91 cm in height, 50 cm wide, 50 cm deep and the sills are 67 cm from floor level. Archers wishing to use them as loops would find they have a limited firing range and, even after leaning right out of the opening, see little of the north and south approaches to the cathedral. The limited range of fire is shown in . Keeping back in the chamber archer X could only make oblique shots towards the north west or south east approaches to the west front. Archer Y could not deviate much from the horizontal and hitting the stonework directly opposite. If the archer was foolish enough to lean right out of the chamber opening, they would need to be aware that directly above them was a so-called machicolation.

The machicolations

There are no known examples of slot machicolations in castles in England from this period that can be compared with the design of the slots in the floor of the North and South West Crossing Chambers at Lincoln. Further, it can be strongly argued that west front slots were not built as functional machicolations. As Kidson notes, the late eleventh century is early for machicolations in castles, let alone cathedrals (Owen Citation1994, 20). Broadly contemporary with Lincoln’s west front are the White Tower and the donjon at Chepstow, but neither has machicolations. Nor do early gatehouses like Lincoln Castle Westgate and Prudhoe, both c.1100. Although no longer surviving there is probably a machicolation over the entry passage in the forebuilding at Norwich from c.1120 and there is one at Castle Rising from c.1140 measuring approximately 1mby 50 cm ( and ).

Figure 23. First floor of Castle Rising keep showing the location of the machicolation within the arch above the entrance staircase.

Although scholars have argued that the Lincoln structures closely compare with the machicolations found in castles, they have paid little attention to their relative construction and, most importantly, their comparative size. However, if we compare the construction of a typical functional slot machicolation as described by Harris with the structures that penetrate the floor of the Lincoln west front Crossing Chambers, we discover there is a marked difference. Harris argues that a functional slot machicolation requires ‘building a number of arches from the ground up supporting a wall at high level forward of the main plan of the wall and with a slot between the two plans and sloping back the main wall’ In contrast, the slots in the Lincoln examples are long (5 m), thin (30 cm wide) and with parallel sides, 2 mdeep at the centre of the arch above the doorway. Interestingly, Harris also argues that some machicolation like constructions may have a non-military significance (Harris Citation2009–2010, 192, 194) and this is a theme expanded by Bonde, who discusses the role of the non-functional machicolation as symbolic protection (Bonde Citation2008, 51). Later, this paper will argue that the slots found within the western arches at Lincoln were built to facilitate sacred liturgical rites.

Alternative, non-military functions for the controversial chambers

The lower North West Chambers, North and South West Buttress Chambers have been described as a prison and a treasury. From the twelfth century onwards, the cathedral was used by the ecclesiastical authorities as an exhibition place for malefactors to perform penances (Owen Citation1994, 133). In the sixteenth century a secure place called Le Wynde is mentioned as the cathedral prison and by the eighteenth century its location is identified as Level One of the North West Chamber (Cole Citation1915, XXXIII). However, it is now thought that the prisoners were incarcerated somewhere else, perhaps in the Cathedral Close. The idea that the lower North West Chambers were a prison was thought by Venables as absurd, who argued that the upper chamber was an ideal strong room for the cathedral’s treasury (Venables Citation1883, 172, 173). There is certainly precedent for this, and church towers have been used as safe places for valuables during troubled times. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for 1070 records that the monks of Peterborough Cathedral hid the church treasures in the steeple when warned of the advance of Hereward the Wake (Swanton Citation2003, 205). The Peterborough account is cited as an example of an Anglo-Saxon tower being used as a treasury and that there are continental examples of towers put to the same use (Taylor Citation2011, 827). From circa 1150 treasuries are often found as upper chambers on the north side of important churches (Huitson Citation2014, 219). It is credible, therefore, that Level One of the North West Chambers at Lincoln was available, if required, to serve as a treasury or store. Certainly, at some point security of the chamber was considered, for the west window of the Level One Chamber is the only opening in the west front to be protected by iron bars.

The North and South West Buttress Chambers have been interpreted as study rooms. Venables described them as ‘small cells, just large enough to contain a stool and a desk and may have served as studies for the ecclesiastics of the church’ (Venables Citation1883, 172).

The west front of Lincoln Cathedral as a spiritual locus and theatre

Having dismissed the argument the Romanesque west front was built to include military-like features we need now to consider a plausible alternative use for the disputed chambers. Firstly, returning to the comparison between the early west front at Lincoln and Roman monumental architecture and in particular the Arch of Constantine, with its symbolic importance to Christianity. The Lincoln west front has similar width and placings of the three arches as the monument (Quiney Citation2001, 169, 170) and they both share a band of sculptures across the front just above the right and left portals.

Remigius had commissioned a towerless rectangular block that alluded to a triumphal arch, but it was primarily a church, and the architecture was envisaged for a different kind of theatre, as he would have been aware of not only the allusions to temporal power and imperialism of his west front but also its overt spiritual symbolism. Possibly inspired by the description of the Heavenly Jerusalem, ‘The city had a great and high wall. In the wall were twelve gates’, with ‘three gates on the east, three gates on the north, three gates on the south, and three gates on the west’ (Revelation 21:12–13, King James version), Remigius’s church, too, has a great, high wall with three gates on the west side.

The view expressed by Dorothy Owen that the west block functioned as the site for liturgical events (Owen Citation1983, 198, 199) has not received sufficient attention and requires serious consideration as it provides an alternative explanation for architectural features regarded by some as military. Klukas is unequivocal in his description of the primary purpose of the mediaeval church building arguing that it ‘was first and foremost a space in which to perform the sacred drama of the Christian liturgy’ and that ‘structure, scale, and decoration were all subordinate to the cultic requirements of Mass and Divine Office’. In Europe there is little information about pre-fourteenth-century liturgy. However, in England we know something about liturgical practice from the Romanesque period (Klukas Citation1983, 136) and Lincoln is fortunate in that we have some evidence, though fragmentary, of its early liturgical practices.

As at York and Old Sarum, Remigius established a secular chapter at Lincoln based around the combination of the principal dignitaries of Dean, Precentor, Chancellor, and Treasurer. The liturgical model Remigius chose is questioned. Giraldus and John of Schalby suggest that Remigius followed the model of Rouen, but others have argued that he adopted the practices of Bayeux. What is certain is that the evolution of secular chapters in Normandy and England had no pre-ordained model and a diocesan arrangements developed slowly within a broadly accepted framework (Bates Citation1992, 25). There is detailed evidence for how liturgical rites were practiced from the thirteenth century onwards and by then six of the nine secular cathedrals, Lincoln, London, Chichester, Wells, Exeter and Lichfield had accepted the Sarum Rites or uses of the Cathedral church of Old Sarum which were based on those of Rouen. However, we also know a little about the rites practiced in Lincoln the early twelfth century. When Gilbert of Sempringham, who had been clerk to bishop Robert Bloet and ordained by bishop Alexander, was establishing his new order in the mid-twelfth century he used the same Holy Week practices and other rites based on those that were used at Lincoln. These included seeing the great west door of the cathedral as of fundamental symbolic importance (Owen Citation1983, 199).

The Sarum liturgy interpreted the west door as the threshold to the Heavenly Jerusalem leading from the life in this world to the eternity that lies beyond. On Palm Sunday and Holy Week Christ’s entry into Jerusalem was staged there, the liturgy instructing that a choir should be placed ‘in eminentiori loco’ in a high place above and over the central west door for boys to sing Gloria, laus et honour, as the procession passed underneath (Sampson Citation1998, 170 and; Ayers Citation2000, 75). Lincoln followed a similar Palm Sunday Sequence. It is recorded that instructions were given for a gallery for a choir to be built over the central west door. Examination of the Lincoln Western Buttress Chambers (argued by some to serve arrow loops) shows that both have openings (now blocked) overlooking the central western arch. These open spaces may have provided access to the wooden gallery ( and ). It can also be argued that the chambers themselves played a part in the ceremony and were early examples of singers’ galleries or holes. Later, by the thirteenth century at Wells and Salisbury, wooden galleries across the west door had evolved into singers’ galleries and holes built as part of the architecture of the west front. Further, we know that at Lincoln on Ascension Day, the relics of the church were washed, and a pall was hung on the front of the church (that is the west front), where the choir halted to sing Non vos relinquam orphanous’ (Owen Citation1994, 118, 119). It is entirely possible that the slots through the floors of the North and South West Crossing Chambers (argued by some to be functional machicolations) (–) were used for hanging banners or palls from above the north and south west portals, a view that Kidson shares (Owen Citation1994, 20) (). It has been argued that the Lincoln west front had facilities for displaying relics. The Daniel panel in the southern length of the Romanesque frieze looks to be inserted into a rectangular blocked opening that rises three courses above the frieze. Further, it has been argued that the great South West Staircase once descended a few steps lower to the opening in the frieze and led to a small platform on the west front that was built for displaying relics or images (Dixon Citation2009, 4). However, recent restoration work on the southern frieze has found solid, original, and undisturbed core work behind the Daniel frieze with no indication that there was once an opening (Clark, personal communication 2020).

Figure 25. A conjectural reconstruction of a banner displayed through the slot in the floor of the South West Crossing Chamber.

The staircases found in the western corners of the west front at Wells are unusually large and it is argued that they were built to provide a sub-processional route from the western galleries and across the triforium for Palm Sunday and other feasts (Sampson Citation1998, 170). The great South West Staircase within the Lincoln west front starts at the same level as the Buttress Chambers and level one of the North West Chambers and at the top serves the North and South West Crossing Chambers ((8)). With a diameter of 3.45 m, it is one of the largest in mediaeval Europe and its size may be explained by the important part it took in the liturgical practices performed at and within the west front.

The decline in the ceremonial importance of the Romanesque west front of Lincoln Cathedral

In the eleventh and twelfth centuries the symbolic importance of the west front at Lincoln, especially the central door with its attendant liturgical practices, was paramount. However, by the mid-thirteenth century, the focus of interest for the church had changed. Even the frieze, from being an essential part of the west front, was seen to have lost its purpose. The sequence of narrative sculptured panels broken; their overall message invalidated. By 1240, the last two (unfinished) panels depicting the Building of the Ark and the Deluge were partly obscured by the south west Gothic façade and the vaulting of the Consistory Court (now the Ringers’ Chapel). Many of the changes to the west front appear to have begun after the canonization of Hugh in 1220 and by 1280 the church was possibly encouraging visitors to go to the east of the church, the Angel Choir, and the shrine of St Hugh. Above the newly commissioned south-eastern door to the shrine pilgrims were met with more didactic iconography, a sculpture of Christ sitting in judgement, surrounded by angels surmounting the gaping mouth of hell.

In the middle of the fourteenth century, Welbourne further diminished the impact of the Romanesque west front by removing the figures from the frieze above the central west door and greatly remodelling the area for the insertion of the Gallery of Kings. Further large sections of the frieze were destroyed when large windows were inserted above the north and south portals. Structural changes were also made within the west front. Examination of the slots in the floor of the North and South West Crossing Chambers show they were fully usable until Welbourne’s alterations to the central arch included new staircases down to the Crossing Chambers which partly blocked each slot by 80 cm (Taylor Citation2020, 155, 157, 159). The Gothic façade was also, at some early time, included in the reappraisal of the west front. It is not recorded when the western entrances to the Morning Chapel and the Consistory Court (now Ringers’ chapel) were blocked. The first credible illustration of the western exterior of Lincoln Cathedral is by Wenceslaus Hollar, circa 1672, and it shows the chapel entrances sealed with stone (as have all illustrations of the west front until the nineteenth century). John Buckler unblocked the entrances between 1859–1866, describing the condition of the uncovered stone of the two recessed entrances as ‘masonry fresh from the quarry cannot look more brilliant’ (Buckler Citation1886, 87).

Conclusion

In the search for a meaning for the unusual architectural details located within the Romanesque western block of Lincoln Cathedral and their identification by some as defensible features, the prime function of the medaieval church as a space built to facilitate sacred liturgical rites has been forgotten. Research has shown that the North West Chambers were not a garderobe complex but an architectural compromise, potential storage spaces created when an arched bay, intended to complement those on the west and south side of the west front, was abandoned after the discovery of fundamental structural problems. The slots through the soffits of the north and southwest arches were not “neck-breakers’’ but designed for hanging devotional tapestries, the openings overlooking the arched bays, singers holes with the chambers behind them providing access to a platform for a choir located above the central door. The eleventh and twelfth century visitors to the west front of the cathedral were not intimidated by the threat of weaponized machicolations and arrow loops, they believed they were approaching the symbolic city gate to the Heavenly Jerusalem. The Romanesque west front was made to be awe-inspiring, an elaborate and colourful stage backdrop but by the late thirteenth century its symbolic importance had declined, the church redirecting the visitor to the potentially lucrative attraction of the shrine of St Hugh.

There are now no standing façades of contemporary major English churches to compare to the planned towerless rectangular block of Remigius’ west front at Lincoln. The Romanesque west front of Lincoln Cathedral is unique. It should be recognized and celebrated as preserving evidence of early liturgical architecture that has been lost in the subsequent redevelopment of contemporary cathedrals.

Lincolnshire Archives: Architects’ reports to the Dean and Chapter Lincoln Cathedral

D&C ARK22 Location: Lincolnshire Archives

D&C ARK22/12 Mr Pearson (December 1874) Report on the west front

D&C ARK22/19 Mr Pearson (1893) Report on north-west tower

File: A/4/13 Report of Clerk of Works 1874–7

WORKS ARCHIVE – LINCOLN CATHEDRAL

DR/16 Robert S Godfrey (1922–32) Executive reports special repairs

Acknowledgements

This survey would not have been possible without the inspiration and advice of the Lincoln Cathedral archaeologist (retired) and colleague, Philip Dixon. I would like to thank Jenny Alexander for her valuable advice when reading the early drafts of this paper. I would also like to thank the staff in the Cathedral Works Department and at the Cathedral Library for their help and practical support, the staff of Lincolnshire Archives, the Society of Antiquities, and the Victoria and Albert Museum for their help in finding documents, drawings, and photographs. I would like to thank Pamela Marshall for her comments on castle defences and Jonathan Clark for his comments on Lincoln Castle and recent restoration work on the south section of the Romanesque frieze. I am grateful for support and advice received from colleagues from the Department of Archaeology at the University of Nottingham and the help over the years with the survey of the west front from 20 enthusiastic Nottingham University students. I am, as always, indebted to my wife Claire for her support and encouragement.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Ayers, T., ed. Sampson, J. Sinclair. E. 2000. Salisbury Cathedral, the West Front. A History and Study in Conservation. Chichester: Phillimore & Co Ltd.

- Bates, D. 1992. Bishop Remigius of Lincoln 1067–1099. Lincoln Cathedral Publications, 25. Lincoln: The Honywood Press.

- Bilson, J. 1911. “The Plan of the First Cathedral Church of Lincoln.” Archaeologia 62 (plate 77): 543–64. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261340900008304.

- Blum, P. Z. March, 1991. “The Sequence of the Building Campaigns at Salisbury Cathedral.” The Art Bulletin 73 (1): 6–38. https://doi.org/10.2307/3045776.

- Bonde, S. 2008. Fortress-Churches of Languedoc. Architecture, Religion, and Conflict in the High Middle Ages. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Buckler, J. C. 1866. A Description and Defence of the Restoration of the Exterior of Lincoln Cathedral. Oxford: Rivingtons.

- Butler, L., and J. Clark. 2015. “Behind the Romanesque Frieze at Lincoln Cathedral.” Archaeological Journal 172 (2): 423–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/00665983.2015.1014625.

- Cocke, T. 1986. “The Architectural History of Lincoln Cathedral from the Dissolution to the Twentieth Century.” In Medieval Art and Architecture at Lincoln Cathedral, Brit. Archaeol. Assoc. Conf. Trans, edited by T.A Heslop and V. Sekules, 148–157. Vol. 8.

- Cole, R., ed. 1915. Chapter Acts of the Cathedral Church of St Mary of Lincoln, AD1520–1536. Notes on Le Wynde, V, II, 38, 112, 118 Vol. 15. Lincoln: Lincoln Record Society.

- Crawford, C. 2013. “Investigating the Polychromy of Lincoln’s Romanesque Frieze Panels, and Its Contribution to the Architectonics and Overall Rhetoric of the Cathedral.” Journal of Architectural Conservation 1 (3): 198–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556207.2013.871857.

- Dimock, J. F., ed. 1877. “Giraldi Cambrensis, Opera.” In Life of Remigius and Life of St Hugh of Burgundy, and John of Schalby. Lives of Bishops of Lincoln, 7, London: Longman.

- Dixon, P. 2009. “The Blocking at the Base of the Great Stair.” Unpublished report to Dean and Chapter, Lincoln Cathedral.

- Erlande-Brandenburg, A. 2007. “The Building of Lincoln Cathedral by Bishop Hugh.” In The Metrical Life of St Hugh, in Cathedral Builders of the Middle Ages, edited by C. Gaston, 131–134, London: Thames and Hudson.

- Fernie, E. 2002. The Architecture of Norman England. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gem, R. 1986. “Lincoln Minster: Ecclesia Pulchra, Ecclesia Fortis.” In Medieval Art and Architecture at Lincoln Cathedral, Brit. Archaeol. Assoc. Conf. Trans, edited by T.A Heslop and V. Sekules, 9–28. Vol. 8.

- Greenway, D. 1995. “Authority, Convention and Observation in Henry of Huntingdon’s Historia Anglorum.” Proceedings of the Battle Conference, Anglo-Norman Studies, 18: 105–122.

- Greenway, D. 1996. Henry, Archdeacon of Huntingdon, Historia Anglorum, the History of the English People. Clarendon Press Oxford.

- Harris, J. 2009–10. “Machicolation: History and Significance.” The Castle Studies Group Journal 23: 193,194.

- Huitson, T. 2014. Stairway to Heaven. The Functions of Medieval Upper Spaces. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Impey, E., ed. 2008. The White Tower. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Kenyon, J. 1990. Medieval Fortifications, 170. Leicester: Leicester University Press.

- Klukas, A. 1983. “The Architectural Implications of the Decreta Lanfranci.” Anglo-Norman Studies VI:136–171. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781787449138

- Lumby, W. 1791. Vestusta Monumenta. Plates for Vol. 3, X, XI. London: Society of Antiquaries.

- McNeill, T. 1992. English Heritage Book of Castles. London: B.T. Batsford/English Heritage London.

- Musson, R. 2008. Earth Hazards and Systems, the Seismicity of the British Isles to 1600, British Geological Survey. Internal Report OR/08/049.

- Nicholson, C., and F. Fox. 1926. “Lincoln Cathedral.” RIBA Journal 33 (6): 159–179.

- Owen, D. 1983. “The Norman Cathedral at Lincoln.” Anglo-Norman Studies VI:188–199. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781787449138.

- Owen, D. ed. 1994. Kidson, P. “Architectural History.” In A History of Lincoln Minster, 14–46. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pevsner, N., J. Harris, and N. Antram. 2002. The Buildings of England, Lincolnshire. 2nd ed. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, Penguin.

- Quiney, A. 2001. “In Hoc Signio. The West Front of Lincoln Cathedral, Essays in Architectural History, Essays in Architectural History Presented to John Newman.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain 44: 163–171. https://doi.org/10.2307/1568745.

- Renn, D. 2011–12. “Arrow-Loops in the Great Tower of Kenilworth Castle: Symbolism Vs Active/Passive ‘Defence.” The Castle Studies Group Journal 25: 175–179.

- Sampson, J. 1998. Wells Cathedral West Front, Construction, Sculpture and Conservation. Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing.

- Saxl, F. 1946. “Lincoln Cathedral: The Eleventh-Century Design for the West Front.” Archaeological Journal 103: 105–18.

- Smith, J. 1905–1906. “Architectural Drawings of Lincoln Cathedral in Norman Times.” AASR 28: 95–98.

- Stalley, R. 2006. “Lapides Reclamaeunt Art and Engineering at Lincoln Cathedral in the Thirteenth Century.” The Antiquaries Journal 86: 131–147. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003581500000081.

- Stocker, D., and A. Vince. 1997. “The Early Norman Castle at Lincoln and a Re-Evaluation of the Original West Tower of Lincoln Castle.” Medieval Archaeo 41: 223–33. https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/library/browse/issue.xhtml?recordId=1139671

- Swanton, M., ed. 2003. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles. London: Phoenix Press.

- Taylor, D. 2010. “The Early West Front of Lincoln Cathedral.” Archaeological Journal 167 (1): 134–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/00665983.2010.11020795.

- Taylor, D. 2020. “An Archaeological Survey of the West Front of Lincoln Cathedral with Specific Reference to its Early Development.” Ph.D. thesis, University of Nottingham.

- Taylor, H. 2011. Anglo-Saxon Architecture. Vol. 3. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Venables, E. 1883. “The Architectural History of Lincoln Cathedral.” Archaeological Journal 40 (1): 159–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/00665983.1883.10852084.

- Zarnecki, G. 1988. Romanesque Lincoln. The Sculpture of the Cathedral. London: Honeywood Press.

Appendices

The practical difficulties of constructing a large complex stone building have not always been appreciated. For example, Fernie (Citation2002, 90) is happy to argue that ‘churches can be built with astonishing speed’ and that Lanfranc’s cathedral at Canterbury took just 10 years to build. The construction time for a notable building is often attributed to the historic dates of the person who commissioned them. Thus, Lincoln’s first Romanesque cathedral is argued to have been built between 1072 and 1092. However, it is now known that when Remigius died some part of his church, most probably the east end, was ready for consecration but the west front was still incomplete, the historic construction dates differing from the archaeological phases of the building (Taylor Citation2010, 137–150).

There were practical restraints limiting the activities of the mediaeval builder. The building season in northern Europe was from March to October, that is 8 months per year, after which frost could threaten the set of the lime mortar. Progress was also limited by the availability of cut and carved stone (Ayers Citation2000, 24–31). It is possible that Remigius and Lanfranc’s builders were blessed with mild winters and excellent logistics, but the implications of this restricted building timeline are great. For example, Remigius is argued to have built his church in 20 years. If the builders were restrained by a construction year of only 8 months, the cathedral was built from its foundation in the equivalent of 13 years and Lanfranc’s Canterbury in the equivalent of 7 years. Both, if taken literally, were astonishing building achievements.

The confusion between the construction and the consecration dates of churches may be partly explained if it is noted that a 1237 papal legate decree made into law a practice that may have already been in place, clarifying when a church should be consecrated. It stated that with no exceptions, all cathedrals and conventual or parish churches ‘whose walls had been completed must be consecrated within two years of that time, even if the structure remained unfinished after the two years had elapsed’ (Blum Citation1991, 21).

Appendix

The restoration work within the west front is extensive and is recognized by this survey as a distinct building phase, identified and separated from the Romanesque and Gothic work. After a fire, and then an earthquake that destroyed the body of the church, the Romanesque west front was again submitted to an ambitious building campaign which placed a further immense load upon foundations not designed to take such weight (see also, Appendix Three: The unstable ground conditions of the cathedral site). Concerns were first raised about the state of the west front in the eighteenth century when damage to the walls below the towers was noted and substantial amounts of masonry were added at ground floor level and voids filled in by James Gibbs and James Essex (Cocke Citation1986, 151–152). The two most effective restoration campaigns began in 1870 with John Pearson who was appointed as cathedral architect, along with his Clerk of Works John Smith. His reports to the Dean and Chapter, which included occasional hand drawn illustrations, described the precarious structural condition of the chambers in the west front. The external wall of Level One of the North West Chambers is described as thin and leaning northwards, the vaulting of the chamber was in a very unsatisfactory state, and the east wall was perished. Pearson recommends that five piers with arches (he builds two) be built on the south side of the chamber and firmly pinned up to the vault to support the massive wall above in Level Two. The North and South West Buttress Chambers were also structurally unsound. Pearson says of them, ‘these chambers (are) separate excepting by mere threads (from) the front part of the legs (bay piers). Where the windows are the separation is complete’ (D&C ARK22/19). The floors and the arched ceilings of the galleries of the North and South West Crossing Chambers are described as completely separated from the walls of the western towers by very large and serious cracks. On the floor the cracks were up to 5 inches (12.7 cm) wide and extended right and left through walls, floors, ceilings, steps and staircases (D&C ARK22/12). Pearson’s approach to restoration was to support the west front with wooden scaffolding and use wedges to push the masonry back into shape securing the whole structure with a cage of steel bars attached to wall plates. He then replaced the shattered stone within. Pearson was unable to examine the underlying structural faults within the west front and western towers and his interventions only provided a temporary solution to its problems (Cocke Citation1986, 154).

Some 25 years later the condition of the west front was continuing to cause concern. Major repairs were begun under the direction of the civil engineer Francis Fox and architect Charles Nicholson with their Clerk of Works, Robert Godfrey. Godfrey kept Weekly and Executive Reports (DR/16) between 1922 and 1932 on the progress of the work with his assistant, Sam Smith, making a photographic record of the repairs. For the restoration, the latest contemporary building techniques were employed. Grout under pressure was injected into the walls and the floors were reinforced with delta bronze clamps. Their work finally stabilized the west front and the two towers. The south elevation of the Ground Floor of the North West Chambers is dominated by a doorway from the nave which is characterized by remedial work (most probably by Godfrey). In Level One Godfrey made extensive restorations to the stonework and laid a steel and concrete screed floor. The use by Godfrey of reinforced concrete for the floors of many chambers and passageways within the west front raised their level by several centimetres.

The drawings of plans and elevations of the Romanesque west front of Lincoln cathedral by William Lumby give a valuable insight into the controversial chambers after Welbourne’s fourteenth century alterations and before Pearson’s and Godfrey’s nineteenth and twentieth century restorations. In 1791, Lumby contributed two plates of illustrations to Vestusta Monumenta showing elevations and plans of the Romanesque west front. Lumby is the first to illustrate level one, that is, the spaces and staircases directly above the nave floor of the west front. According to Lumby’s plan of level one of the west front there is a doorway (now blocked, probably by Pearson) at the base of the Great South West Staircase with steps descending to the walkway across the west front to the Western Buttress Chambers. Further, Pearson’s and Godfrey’s restorations of the Western Crossing Chambers reconfigured and strengthened the north and south walls of both chambers. Lumby’s illustration of the North West Crossing Chamber show the south elevation without the wall and door it has now, and at the north end of the chamber, the stairwell from the North West Tower connects directly with the stairs down to Level Two of the North West Chambers. Lumby also illustrated the north elevation of the South West Crossing Chamber as an uninterrupted staircase leading up to Bank’s View. Today, there is a step within the chamber leading to an arched doorway before the staircase.

Appendix

In his unpublished 1874 Report on the west front to the Dean and Chapter, Pearson argues that the soft compressional nature of the footings of the west front were not able to withstand the effect from the vast weight resulting from the building and repeated raising of the towers. He describes in detail the stratification of exploratory test pits. He notes that the footings of the western towers rest on solid masonry of different dates but that sits directly on what appears to be a few centimetres of topsoil followed by a 90 cm band of clay and gravel before the natural rock. After his examination of the substantial structural damage to the substructure of the west front, Pearson concluded that ‘There can be little doubt that Remigius never contemplated any such superstructure as Bishop Alexander raised upon his work’ (Pearson D&C ARK22/12).

Mediaeval builders had not yet mastered the science of the engineering behaviour of earth materials and were not averse to the opportunist use of Roman or Saxon structures as foundations for their own work. At Lincoln Castle the west wall is built upon Roman foundations and the Lucy Tower motte is supported by them on the southside (Clark, personal communication, 2020). These building experiments were successful. When builders at Lincoln Cathedral came across Roman remains while constructing the north west face of the west front they were quite happy to follow the top of a Roman wall on the western side until they discovered they were on the threshold of a building. The cathedral workmen had then to adjust their building technique accordingly (see ). The cathedral builders were to ignore the unstable ground conditions of the cathedral site with notable adverse consequences. Archaeological investigation has revealed why, circa 1237/39, parts of the crossing tower collapsed, reducing the centre of the cathedral to ruin. Under the eastern side of the transept and the first bay of St Hugh’s choir lies a massive Roman wall, 3.66 m wide, and the collapse of the tower may have been caused by the differential stress caused by the wall (Stalley Citation2006, 141).

Further, the effect of the 1185 earthquake that destroyed the body of Alexander’s church together with its experimental stone vaults may have been exacerbated by the ground conditions. The earthquake has been analysed in an internal report by the British Geological Survey, which argues that the cathedral might have been particularly vulnerable due to geotechnical reasons (Musson Citation2008, 23).