Abstract

This article examines the involvement of Beatrice, dowager Baroness Roos (d. 1415) in the making of art. Her patronage of masons and tomb-makers, glaziers and seal-makers, is explored in detail, showing her to have commissioned works from two of the most prominent English artists of the late medieval period. Her interest in the inventive use of heraldry and her role in the creation of a major monument in St Paul’s Cathedral is established. Her right to be acknowledged as the donor of the St William window in York Minster is reasserted, and her influence on its content and meaning is demonstrated. The gift of this window made Beatrice the single most important secular benefactor of York Minster, a fact that has not been acknowledged before in print, but was recorded by the medieval cathedral chapter in the glazing of the Minster’s western choir clerestory.

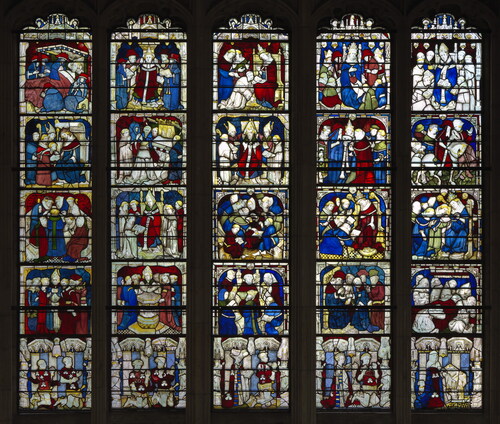

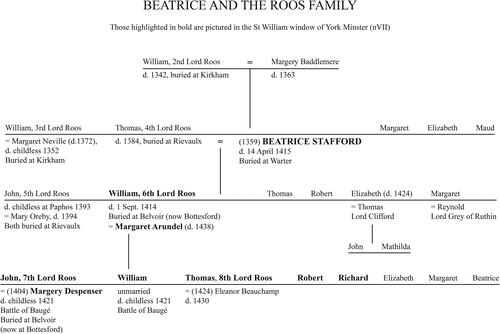

This paper reconsiders the evidence for the art patronage of Beatrice Stafford, dowager Baroness Roos (c. 1344–1415).Footnote1 In 1987, in the pages of this journal, the late Tom French first established her association with the St William window in York Minster (nVII), in an article that re-dated the window and identified the ‘donor figures’ at its base ().Footnote2 Beatrice herself is depicted in panel 1e. However, the presence in the adjoining panel of Beatrice’s son, William, sixth Baron Roos (1d, d. 1414), accompanied by his wife and his own male heirs, suggested to French that Beatrice acted only in concert with her son. In French’s later Corpus Vitrearum volume, Beatrice’s patronage of the window was not explored further, and she has received no further scholarly attention, despite the burgeoning literature devoted to female agency in the arts.Footnote3 Indeed, as recently as 2020, Beatrice was described as William’s wife rather than his mother, robbing her of any agency in the creation of one of late medieval England’s most ambitious hagiographical narratives.Footnote4 New research has revealed the extent of her independent action as an art patron with very considerable resources at her disposal, the consequence of three marriages which took her progressively closer to the centre of Lancastrian power. Her agency can now be traced in the patronage of major works by masons and tomb-makers, glaziers and seal-makers, exercised over a period from the mid-1380s to the second decade of the 15th century. She was the patron of two of late medieval England’s most important artists, master mason Henry Yevele and glazier John Thornton. It will be argued here that in her use of personal heraldry she challenged the traditionally held interpretation of women as the passive transmitters of a formulaic concept of lineage. Her right to be identified as the principal donor of the St William window, and thereby the most important medieval secular patron of York Minster, will be asserted, and it will be argued that the window represents not only a celebration of the life and miracle of the Minster’s resident enshrined saint, but also in its content and imagery, a specific monument to the legacy of this remarkable woman.

beatrice de roos: daughter, wife, mother

Beatrice’s capacity for artistic patronage derived from her accumulation of wealth through three successive marriages. As a widow, her entitlement to a third of her husbands’ estates for the duration of her lifetime made Beatrice very wealthy in her own right and it is perhaps unsurprising that it is to the years of her widowhood that the evidence of her art patronage belongs.Footnote5

Beatrice was the third daughter of Ralph Stafford (1301–72), first earl of Stafford, by Margaret Audley (daughter of Hugh, earl of Gloucester). Although the Staffords were of long-standing influence in the west Midlands, it was Ralph who elevated the family to wealth and national significance through his outstandingly successful career as soldier, administrator and courtier. Advantageous marriage was to play a critical role in Stafford success. McFarlane has shown how Ralph, who had already flaunted the marriage conventions of his class by marrying a noble heiress without royal sanction, invested heavily in securing advantageous marriages for his daughters, and his third daughter, Beatrice, was no exception.Footnote6 While superficially Beatrice’s successive marriages might be read as taking her down rather than up the social scale, closer examination reveals that each union actually moved her increasingly closer to the seat of political influence.

Countess of Desmond, c. 1350–58

Beatrice’s first husband was Maurice fitz Maurice Fitzgerald, heir to the potentially troublesome Irish earldom of Desmond, to whom she was promised on 20 April 1350. Her negotiated marriage portion of £1,000 and a jointure of £200 per annum was extremely generous and can be seen as part of her ambitious father’s pursuit of dynastically advantageous marriage as well as a tool in his policy for the restoration of English lordship in Ireland.Footnote7 The death of the first earl in 1356 made the young Beatrice the countess of Desmond, but in the early summer of 1358 her 21-year-old husband was drowned crossing the Irish Sea. Beatrice was awarded dower in August of that year, and as she was still a year underage, guardians were appointed on her behalf, meaning that she was probably only 13 years old. Indeed, as she is described as residing in England at the time of her husband’s death, it is likely that the marriage was in name only.Footnote8 In her first widowhood her Stafford relatives continued to manage her life and one of her guardians was her powerful uncle Richard Stafford (d. 1380), one of the most important members of the Black Prince’s inner circle.Footnote9

Baroness Roos, 1359–84

Beatrice remained unmarried for less than a year, itself suggestive of an unconsummated union. Her marriage to Thomas, fourth Lord Roos of Hamlake (1336/7–84) was licensed by the Crown on 1 January 1359 and by September of the same year they are described as husband and wife.Footnote10 Thomas had succeeded his elder brother William as Baron Roos of Hamlake (Helmsley) in 1352, and was already a seasoned soldier.Footnote11 Although Thomas Roos was arguably of lesser social rank than Beatrice’s first husband, the Roos family was one of the most important in the north of England. Thomas’s father William (d. 1343) had served on the continual council of Edward III and had been ‘among a circle of welcome visitors at court’ in the early years of the reign.Footnote12 The union of Stafford and Roos was also useful in furthering royal policy in Ireland. In 1361 and 1362 Thomas was called to a council concerning Irish affairs and in 1368 was instructed to take his armed forces with him to reside on Beatrice’s Irish dower lands to prevent their loss.Footnote13 If service to the Crown was financially profitable, service as a retainer of the king’s younger son, John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster, was probably of greater social and dynastic significance, drawing Thomas and Beatrice into a close-knit network of midlands and northern magnate families.Footnote14 Between 1370 and 1382 Thomas was in receipt of one of the larger annuities awarded by the duke and served frequently in his campaigns overseas.Footnote15 As one of Gaunt’s bannerets from 1372 onwards, Thomas became one of the most significant of the duke’s military subordinates, a role fulfilled in the main by magnates from the north. Thomas was active in the parliament of January 1377, convened as Edward III’s health declined and a reopening of war was anticipated.Footnote16

Between 1364 and 1383, Beatrice bore Thomas six children, including the future fifth and sixth barons Roos, John (d. 1393) and William (d. 1414).Footnote17 She also enjoyed John of Gaunt’s personal favour. In June 1372, the duke ordered his forester to allow Beatrice to mount a hunting expedition on his estates at Pickering Lythe (north Yorkshire) at a time of her own convenience.Footnote18 Although the evidence for aristocratic female participation in the hunting of larger game animals is ambivalent, this entry refers to hunting, not hawking, better known as an elite female pastime, offering a rare glimpse of the more adventurous country pursuits of an aristocratic lady.Footnote19 Thomas died at Uffington in Lincolnshire on 8 June 1384 and was buried at his own request in Rievaulx Abbey.Footnote20 His son William followed him into Lancastrian service. In July 1399 William hastened to join Henry Bolingbroke’s invading army, and on 29 September 1399 he attended the interview with Richard II at which the king signed his abdication. He served as privy councillor to Henry IV and as treasurer of England in 1403–04. He was rewarded with the Garter in 1404 and wears the SS collar on his tomb effigy, now in Bottesford church.Footnote21

Lady Burley, 1385–87

Beatrice remained a widow for barely more than the year expected of her. By August of 1385, she had married for a third time.Footnote22 Her third husband was Sir Richard Burley K.G., another favoured retainer of John of Gaunt. As a wealthy widow of about forty years of age, of independent means and with her child-bearing responsibilities to her Roos family behind her, Beatrice would have been far freer to make her own life choices and it was relatively rare for mature widows to remarry.Footnote23 We may conclude that this was a marriage of personal choice, and she married without royal license, although the king’s pardon was sought and quickly given. While the Burleys were in origin a minor Herefordshire gentry family, they had risen in stature and wealth through distinguished diplomatic and military service. By the early years of Richard II’s reign the Burley family was among that small group of courtiers who benefitted disproportionately from the king’s favour, sometimes to the detriment, and often to the chagrin, of their more noble peers.Footnote24 Although it is Richard’s uncle Sir Simon Burley K.G. (d. 1388), tutor and confidant of Richard II,Footnote25 who is the member of this family of courtiers now best-known to history, the path to advancement in royal service had already been trodden by Richard’s father, Sir John Burley K.G. (d. 1383). Sir John, Simon Burley’s older brother, was another companion of the Black Prince and subsequently a chamber knight at the court of Richard II. He was the first knight bachelor to be elected to the Garter fellowship by the new king.Footnote26 He was a trusted envoy in various important diplomatic missions, including the abortive negotiations to marry the young king to Catherine Visconti, and the subsequently successful negotiation for the hand of Anne of Bohemia.Footnote27 Richard followed his father into the service of the Crown and in 1375 he inherited half of the estate of his maternal uncle, Sir Richard Pembridge K.G. (d. 1375), another formerly prominent member of Edward III’s household, for whom the young man had presumably been named.Footnote28 Richard Burley accompanied the Black Prince on his Spanish expedition of 1367, and chronicler Walter of Peterborough singled him out for his bravery in the vanguard actions led by the prince’s younger brother, John of Gaunt.Footnote29 His family typified the social mobility associated with a career in arms in the reign of Edward III, and in 1381 he was another of Richard II’s earliest appointments to the Order of the Garter, following his father and two uncles into this most coveted circle of intimate royal companions.Footnote30

Sir Richard Burley was to become one of the best remunerated of all of John of Gaunt’s retainers, his service coinciding with that of Thomas Roos, through whom he may be presumed to have come into contact with Beatrice. His annuities from the duke of Lancaster practically doubled his income, amounting to in excess of £100 a year.Footnote31 His marriage to Beatrice de Roos gave him an interest in a third of the Roos inheritance during Beatrice’s lifetime, something Thomas’s heir, John was forced to acknowledge.Footnote32 Sir Richard Burley, seasoned soldier, favoured retainer of Edward III’s younger son, nephew of Richard II’s confidant and tutor, and a member of the highest chivalric order in the kingdom, was therefore sufficiently wealthy and well connected to satisfy a twice-widowed dowager of a certain age and independent means.Footnote33

Gaunt’s patronage of Richard Burley was rewarded by decades of loyal service. Burley took out letters of protection prior to campaigning overseas in 1367, 1370 and 1386.Footnote34 In 1386 he was appointed commander of one of the companies prosecuting the duke’s pursuit of his claim to the throne of Castile.Footnote35 On 26 May 1386, while in Plymouth awaiting embarkation for Spain, Richard Burley made his will, in which Beatrice is described as ‘ma treschere compaigne’ and was appointed his principal executor.Footnote36 The duke’s campaign enjoyed initial success, but was then overtaken by a plague that claimed many members of the Lancastrian force, including Richard Burley, who died on 23 May 1387.Footnote37

Beatrice was a widow once more, but this time she did not remarry. She continued to enjoy the favour of the Lancastrian court, attending the coronation of Henry IV wearing robes provided for her by the Lord Chamberlain.Footnote38 Indeed, she enjoyed the widowed state for almost as long as she had been married to her three husbands, and died on 14 April 1415, having made her will in June of the previous year.Footnote39

widowhood, wealth, and the making of art

It was in the last decade of her life that Beatrice deployed her wealth in the creation of two major monuments attributable to two of the greatest artists of the day, the mason Henry Yevele and the glazier John Thornton. The first, now lost, was the tomb and effigy of Sir Richard Burley in St Paul’s Cathedral. The second was the St William window in York Minster (nVII). Her role in the creation of the former has been almost entirely overlooked. Her significance in the creation of the latter has not been fully explored or acknowledged.

The correct identification of Burley’s tomb, long misattributed to Richard’s uncle Simon, is confirmed by the display on it of Beatrice’s personal coat of arms, which in turn can be unequivocally identified by its inclusion on her personal seal. This seal, with its distinctive and unusual marshalling of arms, is deserving of attention in its own right. It is the first surviving evidence of her involvement in the making of art and is unusual among the seals of aristocratic ladies, suggesting an awareness of the power of heraldic display to construct identity and meaning.

The Personal Seal of Beatrice de Roos

Three seal impressions bearing Beatrice’s personal coat of arms and the legend ‘Sigillum domine beatricis de Roos’ have survived. Footnote40 The impressions can be dated to the years 1388–89, 1404 and 1412–14. The shield displayed on the seal is divided vertically in three parts, tierce en pale (). The arms of Roos (gules three water-bougets argent) occupy the dexter third, Beatrice’s natal arms of Stafford (or a chevron gules) the central section of the shield, and the arms of Burley (barry of six sable and or, a chief with two pallets sable, on an inescutcheon gules charged with three bars ermine) the sinister side. Two collared greyhounds sejant support the shield, which has an anchor fesswise arranged across its top, to which the dogs are connected by a cord. The inclusion of the Burley heraldry shows that this was a seal that can only have been adopted after her third marriage in 1385, and which she continued to use well into her third widowhood. Beatrice’s personal seal would have been essential to the conduct of her private affairs. It may be wondered whether Beatrice styled herself as ‘Domine de Roos’ during the lifetime of Richard Burley. After his death, however, she was entering the stage of her life at which her personal wealth would have been at its height. As a wealthy widow she would have been most in need of the personal authority implied by the imagery on the seal, especially in the management of those estates and properties associated with her dower possessions derived from the Roos and Burley patrimonies.Footnote41 The choice of a legend that identified her as the dowager Baroness Roos, a title by which she would have been most readily recognised by her contemporaries, emphasized the continuing status and authority she derived as the matriarch of a large and influential Lancastrian clan with a powerful and politically active heir (and more than one spare).

The evolution of female heraldry and the ways in which the multiple marriages of the elite Englishwoman were represented, especially on their seals, have been explored in print by C. H. Hunter Blair, Adrian Ailes, Peter Coss and Maurice Keen, while Rachel Davis has considered the Scottish material.Footnote42 It is a discussion in which Beatrice has attracted some attention. Hunter Blair, for example, singled out Beatrice’s seal as an interesting example of a shield tierced in pale, while H. Stanford London commented on the inclusion of the greyhound supporters.Footnote43 Indeed, in the marshalling of three shields in one, and in its use of heraldic supporters, Beatrice’s seal seems to have been a rarity among surviving examples of aristocratic ladies’ seals. Hunter Blair has demonstrated that most aristocratic ladies tended to prefer an arrangement in which successive marriage alliances were represented by arrangements of separate shields.Footnote44 In this way, as many as three or four associations could be represented, as in the case of Eleanor Maudit (1325) and Eufemie Heslarton (1369; ), whose seals are decorated with the separate shields of arms of their fathers and three husbands. The seal became, thereby, a chronological narrative of successive relationships of significance and status defined in terms of the arms belonging to fathers and husbands. The closest comparison with Beatrice’s seal, both in terms of its date and its arrangements of arms tierced en pale, is found on the seal of Maud, countess of Northumberland (1381). Like Beatrice, Maud favoured a vertical tripartite shield division on her seal, placing Henry Percy, her third husband in the central position, with her second husband (Umfreville) on the dexter and her father (Lucy) on the sinister.Footnote45 Hunter Blair explained the absence of first husbands on the seals of both Beatrice de Roos and Maud Percy in terms of lack of space, but this explanation lacks conviction, especially as his own survey shows that ways could be found by the engraver of seal dies to accommodate four or more separate shields when the patron required it. A more considered decision to prioritize certain elements over others, and, critically, to integrate them into a single heraldic entity, is implied by the design favoured by Beatrice de Roos and Maud Percy. It is easy to see why, in Beatrice’s case, a brief, childless (and possibly even unconsummated) marriage that had ended nearly half a century earlier carried little emotional weight, while the Fitzmaurice heraldry would have little legal value in managing her affairs in England. The presence of the arms of her own Stafford family and the arms of the husband to whom she bore six children, and whose name she continued to use, require little explanation. On the other hand, the visual parity accorded to the arms of her third husband, to whom she was so briefly married, suggests a strong personal attachment. Visually, the heraldry displayed on Beatrice’s seal does not read as a narrative but as an embodiment, in which Stafford is flanked/supported equally by Roos and Burley, in a distinctive tripartite fusion.

Fig. 3. The seal of Eufemie, daughter of Ralph Lord Neville, widow of (1) Reynold Lucy, (2) Robert Lord Clifford, (3) Sir Walter Heslarton

Drawn by Janet Parkin, based on Hunter Blair, ‘Armorials on English Seals’, pl. XVI, y

The inclusion of animal supporters is also unusual on a female seal of this date. The greyhounds were not beasts used by the Roos family, who seem to have used the peacock as a heraldic device.Footnote46 London has shown that greyhounds were strongly associated with the sons of Edward III and became especially significant in the circle of John of Gaunt, who gifted jewelled badges in the form of white greyhounds to ladies of his circle.Footnote47 While Beatrice is not among those ladies recorded as having received a greyhound jewel from the duke, it may not be entirely irrelevant that it is a small white collared dog that accompanies her in the St William window. The anchor arranged fesswise, another distinctive feature of her seal, has so far defied explanation.

The Monument and Chantry of Sir Richard Burley

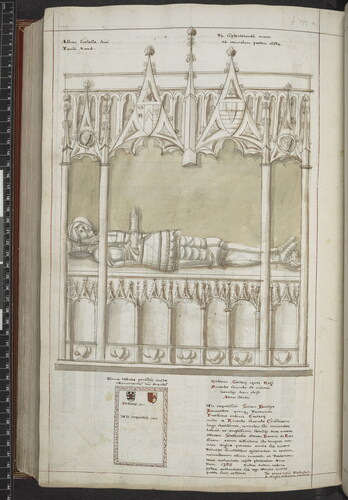

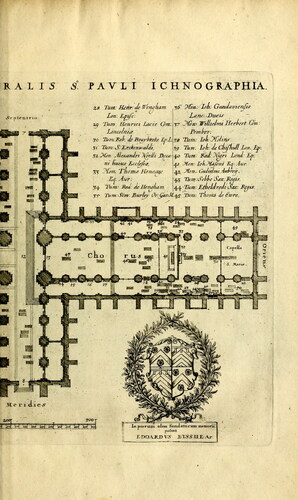

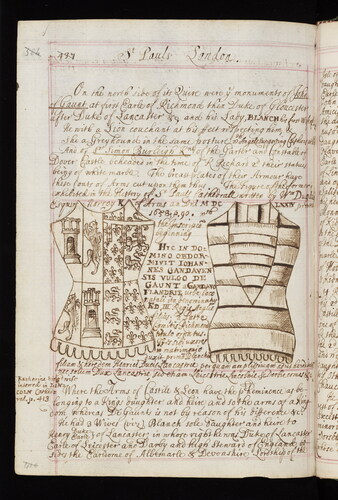

The arms decorating Beatrice’s personal seal were also prominently displayed on the canopy of the large monument commemorating Sir Richard Burley in St Paul’s Cathedral in London. Dugdale recorded its location on his cathedral plan of 1648 and two images of it survive. One is the watercolour drawing made in June 1641 by William Sedgwick for Sir William Dugdale’s ‘Book of Monuments’ (). An engraved version by Wenceslaus Hollar was published in Dugdale’s 1658 history of the cathedral ().Footnote48 The monument was located against the north wall in the sixth bay from the east of the north choir aisle. It faced that of John of Gaunt and his first wife, Blanche of Lancaster, which was located between the piers of the choir arcade, to the north of the high altar ().Footnote49 The tomb displayed a recumbent effigy of Sir Richard in full armour, his head resting on his helm, with a lion at his feet, under a three-bay canopy with four gables of unequal size, each one decorated with a shield.Footnote50 The tomb location had been specified in Richard’s will: ‘en le mure encontre la sepulture mon tresredote seigneur de Lancastre’ (‘in the wall opposite the sepulchre of my very renowned lord of Lancaster’).Footnote51 The double monument to Blanche of Lancaster and John of Gaunt was created between 1372 and 1379 to designs by mason Henry Yevele, with an associated chantry chapel added c. 1403–08. It was widely acknowledged to be a monument of particular splendour, located in an extremely prestigious location.Footnote52 Richard Burley also requested that his executors negotiate with the dean and chapter of St Paul’s in order to establish a chantry at the altar associated with the Lancaster monument, for the benefit of his soul and that of his mother and father, and of his maternal uncle Sir Richard Pembridge. He was one of only three of the duke’s many retainers to mention him directly in their will.Footnote53

Fig. 4. The tomb of Richard de Burley in St Paul’s Cathedral, London, from William Dugdale’s Book of Monuments. Watercolour by William Sedgwick, June 1641

© British Library Board, Add. MS 71474, fol. 181v

Fig. 5. The tomb of Sir Richard Burley in St Paul’s Cathedral, London

From William Dugdale’s History of St Pauls [sic] Cathedral in London (London 1658), drawn by Wenceslas Hollar

![Fig. 5. The tomb of Sir Richard Burley in St Paul’s Cathedral, LondonFrom William Dugdale’s History of St Pauls [sic] Cathedral in London (London 1658), drawn by Wenceslas Hollar](/cms/asset/d296ab10-19fc-4edb-869f-c32964247012/yjba_a_2221105_f0005_c.jpg)

Fig. 6. The location of Richard de Burley’s monument (no. 35) opposite that of John of Gaunt (no. 36). Burley’s tomb is incorrectly identified as that of Simon de Burley

From Dugdale, The History of St Paul’s, plan following p. 160

As Peter Begent has observed, there are minor discrepancies in the representation of heraldic detail in the Sedgwick and Hollar depictions of the tomb, although both versions show that in the central bay of the canopy the gables were decorated on the left with the arms of Roos, Stafford and Burley tierced en pale, as represented on Beatrice’s personal seal, while on the right were the undifferenced arms of Burley.Footnote54 In around 1680 Thomas Dingley drew details of the John of Gaunt’s and Richard Burley’s effigies, recording that Sir Richard’s carved jupon was painted with the undifferenced Burley arms ().Footnote55

Fig. 7. Detail of the effigy of St Richard Burley, drawn by Thomas Dineley, c. 1680

Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Top. Gen. d.19, fol. 300v

Sir Richard’s will did not specify the form or design of his monument, leaving it to his executors to consult appropriate experts: ‘ieo voile que de mes bienz ma sepulture soit honestement et belement faite come mez excutours le saverent deviser par conseil dez hommes de cell art’ (‘I wish that from my goods my tomb be decently and beautifully made, as my executors may devise according to the counsel of men of the craft’). While it did not rival the splendour of the Lancaster memorial nearby, it was clearly a substantial and conspicuous work. Richard’s funeral arrangements were to be appropriately splendid, with the hearse surrounded by five large tapers and a number of torches equal to his age, carried by men dressed in red and white robes. The person charged with the supervision of his wishes was Beatrice: ‘Et ieo ordaigne Beatrice ma trechere compaigne ma principal executrice pur accomplier et faire execucion de toute ma volunte susdite’ (‘And I appoint Beatrice my very dear companion as my principal executor for accomplishing and carrying out all my will as follows’). Richard’s uncle, Simon Burley, also named in the will, was executed less than a year after his nephew’s death and so is unlikely to have played any part in the tomb’s creation. No contract survives for its making, but the cost of the Lancaster monument (£486, paid in instalments), even though proportionally far greater, gives some impression of the scale of investment involved and the weight of responsibility entrusted to Beatrice. Whether Henry Yevele and his associate Thomas Wrek, responsible for the Lancaster monument, were consulted cannot be proven, although John Harvey has identified the monument as a product of the Yevele workshop, a view with which Professor Christopher Wilson concurs.Footnote56 Dingley’s description makes it clear that the Burley effigy closely resembled that of the duke of Lancaster, as both are described as being of ‘marble’, suggesting that the Burley monument was therefore also a composite of materials, with a freestone canopy and tomb base and an alabaster effigy. The niches on the side of the tomb chest would have admitted seven weepers, although all had been lost by the time of Sedgwick’s record.

While the monument may have been commissioned soon after Sir Richard’s death in 1386, the establishment of the chantry requested in his will was delayed by over twenty years. This is probably explained by the somewhat protracted progress of the Lancaster chantry, with which it was always intended to be closely associated. In 1372 the two chaplains engaged to pray for the soul of Blanche were performing their offices at a wooden altar next to her tomb. Only at the time of Gaunt’s own demise in 1399 did formal arrangements for the creation of a perpetual chantry of two chaplains crank up a notch.Footnote57 This involved not only the securing of a chantry licence, but also the building of a separate chapel, which lay behind Sir Richard’s monument, projecting beyond the walls of the north choir aisle, occupying the space between the buttresses of the sixth bay from the east.Footnote58 The Lancaster chantry chapel was described as newly built in 1403 and its endowments and provisions had been formalized in 1408, with a set of ordinances for the chaplains, who resided close by, issued only in December 1411. The exact relationship between the Burley tomb and the entrance to the Lancaster chantry is unclear.

Burley’s own chantry foundation, served by one chaplain, was finally established on 25 November 1408 and shows that Beatrice, described as the widow of Thomas Roos, was still actively securing the fulfilment of his wishes, even if somewhat belatedly. It was she who initiated its creation, having expanded its scope somewhat. It was founded for the benefit of the souls of Richard Burley, his father and mother (John Burley and Amicia Pembridge), his maternal uncle Sir Richard Pembridge K.G., Beatrice’s second husband Thomas de Roos and his parents (William Roos and Margery Badlesmere), and for the good estate during her life and for her soul after death of Beatrice herself.Footnote59

It is telling that in one important respect Richard Burley’s monument did not emulate that of his master John of Gaunt, for despite Beatrice’s close involvement in the creation of the monument and its associated chantry, and the inclusion of her own distinctive personal arms on its canopy, it does not commemorate husband and wife, and Richard’s effigy lies alone. Nor was Beatrice to be buried with the husband to whom she bore six children. It will be argued in the next section of this paper that Beatrice selected the St William window in York Minster as the most public memorial to herself and her achievements as the matriarch of the Roos family.

Beatrice de Roos and York Minster

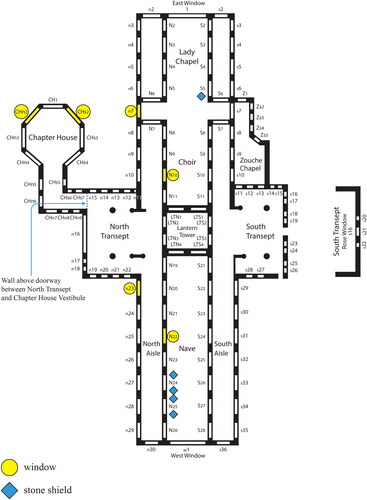

Unequivocal public recognition of the importance of Beatrice de Roos as a patron of the fabric of York Minster is found in stained glass in the fifth light of window NX (panel 2e, ), in the north-west choir clerestory. The Minster shield is unremarkable in its heraldic conventions, impaled appropriately for a married woman, with the shield of Roos (gules three water-bougets argent) on the senior dexter side of the shield and Beatrice’s natal Stafford arms (or a chevron gules) on the sinister. The arms thereby refer specifically to Beatrice’s second marriage of 1359 to 1384 to Thomas, Lord Roos. The Roos family had a long-standing association with York Minster, their arms appearing in stone, glass and paint in at least thirteen locations in the chapter-house, in the chapter-house vestibule, on the north side of the nave and in the Lady Chapel and choir (). Carved in stone in the fourth bay of the south arcade of the Lady Chapel is an undifferenced Roos shield (), the form most frequently found in stone and glass throughout the Minster. The first four bays of the Minster’s new eastern arm were begun c. 1361 by Archbishop John Thoresby and completed by the time of his death in 1373. The installation of this shield, therefore, can be dated to the years of Beatrice’s marriage to Thomas Roos, yet it makes no reference to the Stafford alliance, and the ‘portrait’ head of the carved bust supporting the shield is resolutely male. The western bays of the new choir of the Minster, in which window NX is located, were only begun c. 1394,Footnote60 and French has proposed a date of c. 1408 for the glazing of the north side of the western choir clerestory.Footnote61 The coat of arms in window NX was therefore created over twenty years after Thomas Roos’s death, by which time Beatrice had married and been widowed for the third time. Hers is the only armorial, in stone or glass, specifically associated with a woman in this, the liturgical heart of the Minster. It therefore seems an inescapable conclusion that the shield is intended to be a considered and personal reference to Beatrice de Roos.

Fig. 8. York Minster north-west clerestory, NX. The arms of Roos impaling Stafford are represented in panel 1e

The York Glaziers Trust, reproduced courtesy of the Chapter of York

Fig. 9. The location in York Minster of the arms of Roos in stone, glass and paint

Drawn by Janet Parkin

Fig. 10. York Minster, fourth bay of the south arcade of the Lady Chapel. The arms of Roos carved in stone

Historic England Archive

The arms are located in a window that forms part of a coherent scheme embracing eight windows in the western choir clerestory (NVIII–NXI and SVIII–SXI), which depict important royal and ecclesiastical figures from the early history of the Minster. Beneath the figures are coats of arms commemorating significant Minster benefactors, including prominent members of the nobility as well as senior members of the chapter, some living and some of whom had died many years earlier.Footnote62 No documentary records survive to show who paid for individual windows, so it cannot necessarily be concluded that Beatrice personally paid for the glass depicting her shield. Her arms in window NX are accompanied by shields related to two other well-connected Lancastrians, Archbishop Henry Bowet (1407–23, arms in panel 1c) and Archbishop Thomas Arundel (Archbishop of York 1388–96 and of Canterbury 1396–1414, arms in panel 1a). Both men were themselves generous benefactors to the Minster, and as staunch Lancastrians both were familiar with Beatrice de Roos and her family. Arundel, in particular, was related to the wife of her son William, and was asked to supervise the wills of her sons John and William. William bequeathed plate to Archbishop Arundel and a location close to Arundel’s chantry in Canterbury Cathedral was one of his preferred options for burial.Footnote63

The most likely interpretation of this tribute to Beatrice in this highly significant part of York Minster is that it was the chapter’s acknowledgement of her commitment to the provision of glass for the window of the north-east choir transept (nVII), dedicated to the life and miracles of St William of York. The proposed chronology of the choir clerestory glazing places this event in the very decade in which we know that Beatrice was actively catering for the health of the souls of herself and those dearest to her in the chantry at St Paul’s Cathedral. The year 1408 was also that in which John Thornton completed the Great East window and so was free to turn his attention to the creation of the St William window, widely attributed to him on stylistic grounds.Footnote64

Beatrice de Roos and the St William Window

The St William Window (nVII) occupies the full height of the north-east transept of York Minster, and together with St Cuthbert window in the south-east transept, illuminated the high altar of the Minster.Footnote65 The late-15th-century shrine of St William occupied the bay immediately east of the high altar, and the head shrine of St William was kept nearby.Footnote66 There can be no doubt as to the significance of Beatrice’s commitment to the sponsorship of the St William window, as the window is one of a triptych of huge narrative windows in the new eastern arm, surpassed in size only by the Great East window of 1405–08, the gift of Bishop Walter Skirlaw of Durham. Its southern equivalent, the St Cuthbert window of c. 1440 (sVII), was the gift of Thomas Langley, former dean of York and Skirlaw’s successor as bishop of Durham.Footnote67 This is by far the largest window in York Minster attributable to a secular donor and the only one that can be unequivocally attributed to the patronage of a woman.

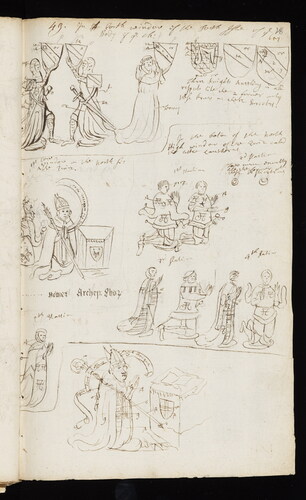

In 1987, French first set the record straight in terms of the identity of the ‘donor figures’ at the base of the St William window, and thereby re-dated it to c. 1414. In particular, he established the identity of the lone female figure kneeling in panel 1e ( and ).Footnote68 Based on a mixture of physical evidence and antiquarian record, French established that the figure is that of Beatrice de Roos. The key evidence for Beatrice’s identity lies in the treatment of her cloak, now patched with modern blue glass on the damaged dexter side but retaining the Roos arms on the sinister side. Thankfully, her figure was drawn c. 1670 in the ‘5th station’ (i.e. panel 1e) by antiquary Henry Johnston, which reveals that her cloak originally displayed her natal arms of Stafford on the dexter side, with those of Roos on the sinister (, bottom left). In c. 1620 Roger Dodsworth recorded the same arms on the carved shield supported by an angel at the window’s sill immediately below her figure in glass.Footnote69

Fig. 11. York Minster, St William window (nVII), panel 1e, Beatrice de Roos

The York Glaziers Trust, reproduced courtesy of the Chapter of York

Fig. 12. Henry Johnston’s record of the donor figures c. 1670. Beatrice is shown on the extreme left of the page, labelled as occupying the ‘5th station’ (bottom left)

Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Top. Yorks. C14, fol. 28r

All the ‘donor figures’ are kneeling, facing east, and are therefore intended to be read from right to left. French demonstrated that the careful application of marks of cadency to the Roos heraldry on the costume of the male figures in panels 1a–1c means that we are looking at the image of a father and mother (in 1d), accompanied by their five sons, only the oldest of whom (in 1c) was married at the time the glass made. Panel 1d displays a bearded kneeling male figure with a jewelled circlet on his head, dressed in armour with a heraldic surcoat displaying Roos without difference (). His wife wears a coronet over her coif and a costume decorated with the arms of Roos impaling Despencer quartering Goushill. Panel 1c depicts a clean-shaven kneeling man in armour with a circlet of leaves decorated with a single jewel on his head, with a heraldic surcoat displaying Roos with a label for difference (). His wife wears an elaborate hat and a costume also decorated with the arms of Roos impaling Despencer quartering Goushill. Both wives hold open books. Panel 1b depicts two clean-shaven kneeling youths, both dressed in armour (). The surcoat of the figure on the right displays Ross with a crescent for difference, that on the left Roos with an annulet for difference. The young man on the left also wears a wreath on his head with single jewel. Panel 1a contains two more kneeling youths in armour (), both clean shaven and bare headed. The surcoat of the boy on the right displays Roos with a star for difference, that of the boy on the left a trefoil.

Fig. 13. York Minster, St William window (nVII), panel 1d, William Roos and his wife Margaret

The York Glaziers Trust, reproduced courtesy of the Chapter of York

Fig. 14a–c. York Minster, St William window (nVII); a. panel 1c, John Roos and his wife Margery; b. York Minster, St William window (nVII), panel 1b, William and Thomas Roos; c. York Minster, St William window (nVII), panel 1a, Robert and Richard Roos

The York Glaziers Trust, reproduced courtesy of the Chapter of York

Only one combination of Roos family members fits this family configuration (), confirming that the figures in 1d are William, sixth Baron Roos (d. 1414) and his wife Margaret Arundel, with John (d. 1421), seventh Baron Roos, accompanied by his wife Margery Despencer, in panel 1c. Panel 1b depicts William (d. 1421) and Thomas (d. 1430). Youngest sons Robert and Richard appear in panel 1a.Footnote70 John, although only seventeen at the time of his father’s death in 1414, was married by 1404 and died without heirs. William junior died unmarried, and Thomas, who according to his father’s will was originally destined for the church, was only eight when his father died. Propelled into the barony in 1421 by the unexpected and childless deaths of his older brothers John and William at the battle of Baugé, Thomas was only licensed to marry Eleanor Beauchamp in 1423 and was himself a casualty of war, although not before fathering a male heir.

Fig. 15. The Roos Family Tree

Drawn by Janet Parkin, after French, ‘The glazing of the St William Window’

Much has been made in the past of the recurrence of Despencer arms in the heraldic dress of the two wives depicted in 1d and 1c. Ingenious but implausible explanations for the absence of Margaret Audley’s arms and the duplication of Margery Despencer’s impaled cloak have been made, none of them at all satisfactory.Footnote71 The most plausible explanation is that in the immediate aftermath of William’s death in September 1414, a matter of months before his mother Beatrice, and the accession of John to the barony, an attempt was made to alter the baronial succession depicted at the window’s base.Footnote72

The treatment of the figure of Beatrice de Roos in 1e reinforces her claim to be the principal and probably the sole donor of the St William window. Beatrice’s figure is located in the most easterly and thereby the most honorific position, closest to the high altar. She is also thereby placed quite literally at the head of her family, and she is the only figure afforded a panel to herself, which she shares only with a small pet dog who looks backwards to her then-living children and their spouses, who kneel behind her. In this arrangement, a telling comparison may be made with the representation of the donor at the base of the nearby Great East window, where Bishop Walter Skirlaw is similarly afforded an entire panel to himself. In the donor image, Beatrice’s widowed status is signalled by her sober dress, which is in marked contrast to the modish apparel and bejewelled headdresses of her daughter-in-law and granddaughter-in-law. She kneels before a prie-dieu bearing an open book.

Despite its now-damaged state, Beatrice’s costume deserves closer scrutiny, for no mention has yet been made of the very specific detailing of Beatrice’s heraldic dress. French described her as wearing the arms of Roos impaling Stafford.Footnote73 In fact, Beatrice’s heraldic clothing in nVII did not conform to the normal form of an impaled coat, in which the arms of the wife’s family appeared on the junior ‘sinister’ side of the shield with that of the husband on the senior ‘dexter’ side. This is the conventional form observed in the version of her arms in clerestory window NX, as well as in the dress of the Roos wives depicted in panels 1d and 1c of the St William window, where their natal arms are overlaid by a mantle of Roos heraldry occupying the senior ‘dexter’ side. It is clear both from Johnson’s sketch and from the vertical line dividing the surviving Roos arms from the damaged area of her cloak, that the Stafford arms (or a chevron gules) were on the visually as well as symbolically more prominent dexter side of the armorial, and that technically Beatrice wore the arms of Stafford impaling Roos. Notwithstanding the duplication of heraldic clothing in panels 1d and 1c, mentioned above, it is clear that the window’s designer was sensitive to heraldic detail, notably in the careful use of marks of cadency on the heraldic surcoats of William Roos’s sons; this reversal of the dexter and sinister sides of her heraldic cloak looks deliberate.Footnote74 Had this detail survived, Beatrice’s figure would have been visually all the more distinctive compared to the women in the adjoining panels.

The gallery of family figures over which Beatrice presides has no place for her second husband, Thomas Roos, long since dead at the time of the window’s creation, nor for their eldest son, John, fifth baron, who had died in 1393 while on return from pilgrimage. A strip of fragmented white glass running through the base of the window may once have contained an inscription requesting payers for the repose of their souls. The Roos family members depicted in the window were therefore all living at the time of the window’s inception, if not at the time of its completion, even if William’s younger sons, depicted here as armoured youngsters, were actually in their infancy at the time. The window also makes no provision for images of William de Roos’s four legitimate daughters.

Beatrice is therefore celebrated in the window as the progenitrice of the Roos succession. Beatrice was very well aware of the fragility of family lines and the importance of numerous sons. Her husband Thomas had succeeded his own elder brother, and her own eldest son, John, had not lived long enough to establish his own family line. Her brother, Hugh Stafford, second Earl Stafford (d. 1385) was himself a second son, and was succeeded by his own second son, having lost his oldest heir at the murderous hand of Sir John Holland. Hugh’s second son, Thomas Stafford, third earl, died childless in 1392 and was succeeded by his two younger brothers William (d. 1395) and Edmund (d. 1403).Footnote75 In the event, William Roos’s own eldest heir, depicted in 1c, also died without issue, but as the father of five sons, William’s line was secure. Beatrice’s gallery is not, therefore, intended to hold in the mind’s eye the souls of the departed, but to celebrate the solidity and vigour of the present, and thus the secure future of the Roos inheritance.

A number of factors would have commended a window dedicated to St William to a family led by a determined and well-resourced aristocratic matriarch. An advantageous marriage in the distant past meant that the Roos family could legitimately claim St William as a family member, through the union of Lucy Fitzherbert, daughter of St William’s great nephew Peter Fitzherbert (d. 1235) to William de Roos (d. 1264).Footnote76 The name William was also favoured in the family. If the St William window was an opportunity to refresh the prestige of the Minster’s officially enshrined saint in the face of the popular appeal of the new, unofficial cult of Archbishop Richard Scrope (d. 1405), it was also an opportunity for the Roos family, a prominent local family with a long-standing association with the Minster, eclipsed in recent years by the prominence of the Scropes of Masham, to reassert itself as a major patron of the cathedral.Footnote77

The predominance of female beneficiaries of St William’s miracle-working would have exerted a particular appeal for a female donor.Footnote78 In panels 24d and 24e, the final two panels at the very top of the narrative and immediately above the figure of Beatrice herself, are two scenes depicting an accident taking place in a landscape. An aristocratic woman dressed in red and wearing an ermine and bejewelled hat, the only elite woman depicted in the window, other than the female members of the royal family represented in panels 18b and 18e, is first apparently trampled by a horse () and then gives thanks at the shrine of St William for her deliverance ().Footnote79 These panels were drawn quite deliberately to conclude the narrative, comprising ninety-five panels, more than half of which are devoted to posthumous miracles of St William, and most of which are associated with his shrine in the Minster. This posed a very considerable challenge in terms of subject matter and design. Some of the panels depict specific miracles which can be identified in the extant Latin sources. Others represent generic categories of miracle mentioned in the sources, such as healing people with hydropsy. Others again seem to depict individual miracles which, however, find no parallel in the surviving sources.Footnote80 The miracles are arranged broadly speaking in chronological order, and the window was devised and made from the bottom upwards, following the narrative order.

Fig. 16. York Minster, St William window (nVII), panel 24d. An aristocratic lady is knocked over by a mounted man

The York Glaziers Trust, reproduced courtesy of the Chapter of York

Fig. 17. York Minster, the St William window (nVII), panel 24e. The lady offers thanks at the shrine of St William in York Minster

The York Glaziers Trust, reproduced courtesy of the Chapter of York

By the time the designers reached the top of the window, however, inspiration seems to have failed them. Up to that point, even though the shrine is depicted numerous times, each panel was individually designed. But in the last two rows at the very top of the window (rows 23 and 24), we find that design elements from panels lower down—depictions of the shrine, figures grouped around it etc.—are reused, but all recombined in different ways to give the appearance of original new scenes. All except the last two panels depicting the aristocratic lady. These panels, which have no parallel in the written sources, evidently depict a specific and recent incident, and have clearly been specially chosen to fill the last two places in the narrative, in such a way that the lady kneeling in front of the shrine in panel 24e is located immediately above the figure of Beatrice de Roos kneeling at her prie-dieu. It is tempting to identify this sumptuously dressed noble lady as Beatrice herself, depicting some unrecorded life-threatening incident in her active youth, when, as we have seen, she counted hunting among her leisure pursuits. The rich ruby of her gown, although not embellished with any heraldry, is the colour predominant in the arms of both Roos and Burley, as well as being the tincture of the charge on the shield of Stafford.

death and burial

Beatrice died on 14 April 1415 and her Inquisition Post Mortem identifies her eldest grand-son, John, then aged eighteen, as her heir.Footnote81 Beatrice’s choice of final resting place is intriguing. She was buried neither with one of her husbands nor close to her children, requesting instead burial in the choir of the small Augustinian house of Warter in the East Riding, a house that has sadly disappeared without physical trace. Warter was neither prominent nor wealthy, and was valued at only £144 in 1535.Footnote82 It had been (re)founded in the 1130s by Geoffrey Fitz-Pain, alias Trussebut, and passed to the Roos family, together with the distinctive water-bouget armorial, probably in the 1170s.Footnote83 This was a house that would have been familiar to Beatrice, for at the time of her death she seems to have been living nearby at Storwood (known as Storthwaite in the Middle Ages), a manor held by the Roos family since the 13th century. It is recorded as being held as part of the dower of Beatrice’s mother-in-law Margery (née Badlesmere, d. 1363), one of those commemorated in the chantry at St Paul’s Cathedral, and Beatrice was similarly seized of it at her death in 1415, suggesting that this was the Roos dower house.Footnote84 In her will, made on 26 June 1414, Beatrice left £50 for masses to be sung for five years by two chaplains at the church in the shadow of the Roos stronghold of Helmsley, for the souls of herself, Thomas Roos and all the faithful departed, and £40 for the same to be celebrated for four years by a single chaplain at Storthwaite. Footnote85 Otherwise, the Augustinians seem to have attracted her particular favour, for in addition to gifts to the prior, subprior and every canon, as well as to the church of Warter, she was also generous to the Augustinians of nearby York, who received 100s, compared to the five marks each bequeathed to the York Franciscans, Dominicans and Carmelites. Female religious also received her bounty. Beatrice Chetwyn, canoness of Aconbury, perhaps a relative of esquire William Chetwyn who witnessed the will, received 53s 4d. Beatrice Roos also shared with other members of her family, and the Lancastrian circle more generally, a fondness for recluses and anchorites, bequeathing to the anchoresses of Leake and Nun Appleton 40s each. Indeed, it might be wondered whether it was not from their mother that John and William Roos both derived their own devotion to anchorites.Footnote86

There is no evidence of Warter having attracted other Roos burials. The family had originally favoured the choir of the Augustinian priory of Kirkham, founded by Walter Espec, lord of Helmsley, where at least four lords had been laid to rest.Footnote87 Thomas, Beatrice’s second husband, had chosen the choir of Cistercian Rievaulx, another Espec foundation, where John, fifth Lord Roos (d. 1393), Thomas and Beatrice’s eldest son, was also buried, in the Lady Chapel, close to the shrine of St Aelred, where he was joined by his wife, Mary (d. 1394), who commissioned a large marble stone to cover her.Footnote88 Beatrice and Thomas’s second son, William (d. 1414), who had succeeded his brother as sixth Baron Roos, was buried at the minor Benedictine house of Belvoir in Leicestershire, where he was joined by his own son John, who, with his brother William, died at the battle of Baugé in 1421.Footnote89

Recent research by Jessica Barker reminds us that it was not uncommon for much-married women to choose to be buried alone and apart from husbands and children.Footnote90 This appears to have been Beatrice’s choice. She may well have derived her partiality for the Augustinians from her natal family, for the Staffords strongly favoured the order. Beatrice’s father, Ralph, first earl of Stafford, was buried at Tonbridge Priory in Kent, the Augustinian mausoleum of Beatrice’s mother’s family. His own ancestors were buried at Stone Priory in Staffordshire, centre of the cult of St Wulfhad of whom he was a devotee, with prayers also said for him at the Augustinian house of his own foundation at Stafford.Footnote91 His son and heir, Beatrice’s brother, Hugh (d. 1386), second earl, was buried at Augustinian Stone.Footnote92

Beatrice’s generosity to Warter could be expected to have secured for her a burial location of some prominence in the chancel of the small church, said to have been only 28 yards long and 9 yards wide.Footnote93 Liturgical observance in the church was greatly enhanced thanks to Beatrice’s bounty. Her gifts included two tall candlesticks, a silver-gilt chalice, two cruets, a silver pax board, one pair of censers and a silver bell. In addition, she donated a full set of vestments of blue cloth of gold comprising three albs, with two tunicles, one chasuble, one cope, one altar frontal and one reredos with appurtenances.Footnote94 These vestments were significantly more splendid that those she bequeathed to the parish churches of Helmsley and Hemingbrough. These liturgical items can all be identified in an inventory of Warter made at the time of the Dissolution, where her vestments are described as ‘one sutte of blew sylke callyd the watter bowges’, and they were not donated to local parishes, the fate of some of the more modest textiles listed in the inventory.Footnote95 They bore a similarity in colour to the set of rich bed hangings that she bequeathed to her son William: ‘one complete blue bed with its hangings embroidered with white roses and the arms of Roos and Stafford’.Footnote96 Frustratingly, no mention is made of the form of any memorial to Beatrice.

conclusion

In common with that of most medieval women, the life of Beatrice de Roos can only be recovered from a series of partial glimpses and the occasional documentary reference. She comes into sharper focus only in the years of her final widowhood, when the control of her accumulated dower and the release from marriage and motherhood gave her a range of choices that would not have been hers earlier in her life. Widows, and especially older widows, were traditionally in a far stronger position than unmarried younger women, and it is clear from the surviving evidence that Beatrice exercised her opportunities, rights and privileges to the full. In her use of a variety of forms of her family heraldry, for example, in flexible and diverse combinations, we can see that she was sensitive to the potential of the medium for the projection of a variety of identities. This is a kind of subtle manipulation of the rules of heraldic marshalling that is not unknown, but which has rarely been associated with a woman. Richard II famously impaled his arms with those of Edward the Confessor, ceding to the saint the heraldic location appropriate to the husband.Footnote97 John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster, did something similar. By virtue of his second marriage, he laid claim to the throne of Castile and León and began to impale the arms of England with those of his second wife, Constance of Castile, initially in the dexter position of greater honour. After he surrendered his claim to the throne of Castile and León in 1388, he reversed the marshalling, returning his own royal arms to the dexter side of the impalement, which is how they were shown on his tomb effigy.Footnote98

Beatrice was also capable of manipulating her own heraldry in order to create images that were personal, emblematic and specific to their location, their function and their audience. On her personal seal, she projected a complex composite identity, fusing her aristocratic natal origins with the military and political prestige of Roos and Burley from whom she derived wealth and independence. It is with this heraldry that she includes herself on Richard Burley’s tomb close to that of the duke of Lancaster. In the choir clerestory glazing of York Minster she is represented more conventionally as the wife of Thomas Roos, but she was the only woman to be commemorated in this liturgical space, acknowledged on an equal footing with elite male donors and benefactors. In the St William window, she appears in the position of greatest honour, and in effect, as the head of the noble household of Roos, longstanding benefactors of the mother church of the northern province. The hagiographical narrative bears the stamp of her influence, while the imagery of the window’s bottom row is an unsentimental snapshot of Beatrice’s personal achievements as daughter of the self-made and powerful earl of Stafford and matriarch of a successful and fecund family—an image of a dynastic and political success story in which there is no room for the deceased or the dynastically irrelevant.Footnote99 It is a celebration of a family’s future, not a memorial to its past. It is the St William window that stands as her lasting memorial and her greatest gift to posterity, for in death she once again eludes us.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In the evolution of this paper, which emerged out of a lockdown project, I received a great deal of advice, practical help and moral support from my friends and colleagues Philip Lankester FSA and Professor Christopher Norton FSA. Dr Joseph Spooner FSA provided invaluable help in the interpretation of textual sources, and Janet Parkin provided essential artwork. For the helpful comments of the two anonymous readers, I record my thanks. Any shortcomings that remain are entirely my own.

Notes

1 In the Complete Peerage the Roos family name is spelt ‘Ros’ and this variant is commonly found in relation to this baronial family, with its seat at Helmsley Castle. However, Beatrice herself spelt her name ‘Roos’, and this is the spelling that has been adopted throughout this text.

2 T. French, ‘The glazing of the St William Window of York Minster’, JBAA, 140 (1987), 175–81.

3 Notably the research distilled in Reassessing the Roles of Woman as ‘Makers’ of Medieval Art and Architecture, ed. T. Martin, 2 vols (Leiden 2012). Beatrice’s art patronage is of too late a date to have attracted the attention of L. L. Gee’s Women, Art and Patronage from Henry III to Edward III (Woodbridge 2002), while she is too early to appear in Susan E. James’s The Feminine Dynamic in English Art, 1485–1603 (Abingdon 2009) or in B. J. Harris’s English Aristocratic Women and the Fabric of Piety, 1450–1550 (Amsterdam 2018). She also escaped notice in Christine Hediger’s ‘Female donors of Medieval stained glass windows’, in Investigations in Medieval Stained Glass, ed. E. C. Pastan and B. Kurmann Schwarz (Leiden 2019), 239–50.

4 P. A. Fox, Great Cloister: A lost Canterbury Tale (Oxford 2020), 554–56. Fox first correctly states Beatrice to be the mother of William, but barely a page later describes her as William’s wife.

5 On the day of her marriage a wife was traditionally assigned a third of her husband’s possessions, and after his death retained this for her lifetime, whether she remarried or not: H. Leyser, Medieval Women: A Social History of Women in England 450–1500 (London 1995), ch. 8.

6 K. B. McFarlane, The Nobility of Later Medieval England (Oxford 1973), 187–212; C. Rawcliffe, ‘Stafford, Ralph, first earl of Stafford (1301–72), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/26211 (accessed 14 November 2022).

7 G. E. Cockayne ed., The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland (London 1910–59), IV, 241–42.

8 Calendar of Patent Rolls, 53 vols (London 1819–1916) (hereafter CPR), Edward III, 1358–61, 58, 16 June 1358. I am grateful to Dr Jeremy Goldberg for discussing with me the implications of this information.

9 K. B. McFarlane, Lancastrian Kings and Lollard Knights (Oxford 1972), 174–75; Rawcliffe, ‘Stafford, Ralph’.

10 CPR, Edward III, 1358–61, 143, 271.

11 He served in France in 1355, 1356 and 1359–60: Complete Peerage IX, 100–01.

12 W. M. Ormrod, Edward III (New Haven and London 2011), 58, 137.

13 Complete Peerage IX, 100–1.

14 Simon Walker has estimated that Thomas Roos earned £250 per annum from his royal annuity, but only £50 from the duke, who was also slow to pay his debts: S. Walker, The Lancastrian Affinity (Oxford 1990), 62, 105.

15 He served abroad in in 1369, 1370, 1372, 1373 and 1378: Walker, Lancastrian Affinity, 280.

16 Ormrod, Edward III, 571.

17 Four sons and two daughters; John, William, Thomas, Robert. See E. and M. L. Toulmin Smith ed., The Itinerary of John Leland, 5 vols (London and Carbondale 1909–64), I, 92.

18 S. Armitage-Smith ed., John of Gaunt’s Register (1371–1375), Camden Society Third Series, 4 vols (London 1911–37), II, 56–57, no. 989.

19 Richard Almond, Medieval Hunting (Stroud 2011), 101–15.

20 A. Gibbons, Early Lincoln Wills (Lincoln 1888), 70; Itinerary of John Leland, I, 92.

21 Complete Peerage XI, 101; Tobias Capwell, Armour of the English Knight 1400–1450 (London 2015), 135, figs 1.194, 1.224, 1.264, 1.268.

22 CPR, Richard II, 1385–89, 8. Pardon granted 20 August 1385.

23 J. Rosenthal, ‘Aristocratic Widows in Fifteenth-Century England’, in Women and the Structure of Society, ed. B. J. Harris and J. McNamarra (Durham, GA 1984), 36–52.

24 N. Saul, Richard II (New Haven and London 1997), 129.

25 J. L. Leland, ‘Burley, Sir Simon (1336?–1388)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online, https://doi-org/libproxy.york.ac.uk/10.1093/ref:odnb/4036 (accessed 27 March 2023).

26 H. E. L. Collins, The Order of the Garter 1348–1461. Chivalry and Politics in Late Medieval England (Oxford 2000), 49, 96–97.

27 Saul, Richard II, 84, 87–88.

28 A. Gross, ‘Pembridge, Sir Richard (c.1320–1375), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online, https://www-oxforddnb-com.libproxy.york.ac.uk/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-21826?print=pdf (accessed 27 March 2023).

29 A. Goodman, John of Gaunt: The Exercise of Princely Power in Fourteenth-Century Europe (Harlow 1992), 228–29.

30 G. F. Beltz, Memorials of the Most Noble Order of the Garter (London 1841), 291–94; J. L. Gillespie, ‘Chivalry and Kingship’, in The Age of Richard II, ed. J. L. Gillespie (Stroud 1997), 115–38.

31 Walker, Lancastrian Affinity, 91–92.

32 15 November 1386: Calendar of the Close Rolls, 47 vols (London 1900–63), Richard II, 3, 1385–89, 286–88.

33 By the 15th century, the financial security of the dowager was at its height: R. Archer, ‘Rich old ladies: The problem of late medieval dowagers’, in Property and Politics: Essays in Later Medieval English History, ed. A. J. Pollard (Gloucester and New York 1984), 15–31.

34 Walker, Lancastrian Affinity, 266.

35 Saul, Richard II, 148–50. Burley served under Sir John Holland, half-brother of the king and one of the duke of Lancaster’s sons-in-law, infamous as the murderer of Beatrice’s nephew, the son and heir of the earl of Stafford.

36 J. H. Parry ed., Registrum Johannis Gilbert: episcopi Herrfordensis 1375–89, Canterbury and York Society 18 (London 1925), 109–12.

37 L. C. Hector and B. F. Harvey ed., The Westminster Chronicle (Oxford 1983), 191; Calendar of Inquisitions Post-Mortem, 26 vols (London 1904–2010), XVI, 514, 515.

38 Complete Peerage, XI, 101.

39 Testamenta Eboracensia I, Surtees Society (London 1836), IV, 375–79; J. Ward trans. & ed., Women of the English Nobility and Gentry 106–1500 (Manchester 1995), 227–30.

40 That of 1388 is in the National Archives, Kew, attached to E213/73, published in R. H. Ellis, Catalogue of Seals in the Public Record Office, Personal Seals Vol. II (London 1981), no. P1960, 91 and pl. 26, and document reference online at https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C3422554 (accessed 23 March 2022). That of 1404 is attached to British Library Add. Ch. 22391, published in W. G. de Birch, Catalogue of Seals in the Department of Manuscripts in the British Museum, 6 vols (London 1887–1900), III, no. 13073, 448–49, and pl. VIII. The BL is also in possession of a sulphur cast said to have been attached to a charter dated 1412–14 in the possession of the second Earl of Leicester, now department of Western Manuscripts, detached seal LXXVI.42, reference online at https://searcharchives.bl.uk/primo_library/libweb/action/display.do;jsessionid=32189C38F2F52FA52A23C944AA9950EF?ct=display&fn=search&doc=IAMS040-002215002&indx=1&recIds=IAMS040-002215002&recIdxs=0&elementId=0&renderMode=poppedOut&displayMode=full&frbg=&frbrVersion=&dscnt=0&scp.scps=scope%3A%28BL%29&vid=IAMS_VU2&mode=Basic&srt=rank&tab=local&vl(freeText0)=Beatrix%20de%20Roos&dum=true&dstmp=1676806386547&tabs=moreTab&gathStatTab=true (accessed 23 March 2023). A drawing of the same seal impression but minus the legend, attached to an unidentified document, is shown in London, College of Arms MS Aspilogia 2, fol. 32r, where it is mistakenly attributed to Simon de Burley.

41 Bedos-Rezok has observed, in relation to the French sigillographic evidence, that while the seal of a woman carried as much legal weight as that of a man, documents issued by a man and wife were usually validated by the man’s seal alone: B. Bedos-Rezak, ‘Medieval Women in French sigillographic sources’, in Medieval Women and the Sources of Medieval History, ed. J. T. Rosenthal (Athens, GA 1990), 1–36.

42 C. H. Hunter Blair, ‘Armorials on English seals from the twelfth to the sixteenth century’, Archaeologia, 89 (1943), 1–26; A. Ailes, ‘Heraldic marshalling in medieval England’, in Proceedings of the VIII Colloquium of the Academie Internationale d’Heraldique (Canterbury 1995), 15–29; P. Coss, The Lady in Medieval England (Stroud 1998), 38–50; A. Ailes, ‘Armorial portrait shields of medieval noblewomen—Examples in the Public Record Office’, in Tribute to an Armorist, ed. John Campbell-Kease (London 2000), 218–34; M. Keen, ‘Heraldry and the Medieval Gentlewoman’, The Coat of Arms, 3rd series, vol. I, part 1, no. 209 (2005), 1–8; R. Davis, ‘Material Evidence? Reapproaching elite women’s seals and charters in late Medieval Scotland’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 150 (2021), 301–26.

43 Hunter Blair, ‘Armorials on English seals’, 23; H. S. London, ‘The greyhound as a royal beast’, Archaeologia, 97 (1955), 139–63.

44 Hunter Blair, ‘Armorials on English seals’, 23–25.

45 Hunter Blair, ‘Armorials on English seals’ 23, pl. XVI v.

46 William Roos rests his head on a helm surmounted by a peacock on his surviving effigy now at Bottesford, while the feet of a lost bird remain on the helm of his son, John (d. 1421): Capwell, Armour, figs 1.191, 1.301.

47 London, ‘The greyhound as a royal beast’, 150–51.

48 William Dugdale’s ‘Book of Monuments’, London, British Library, Add. MS 71474, fol. 181v, watercolour drawing by William Sedgwick; W. Dugdale, The History of St Pauls [sic] Cathedral in London (London 1658), 38, 102 and fold-out plan.

49 Dugdale, History of St Pauls, 90–91.

50 A post-medieval plaque, of unknown date and origin, attached to the wall above the recumbent effigy, wrongly identified the figure as being that of Sir Simon de Burley (d. 1388), uncle of Sir Richard, an identification accepted at face value by Dugdale and Ashmole: E. Ashmole, The Institutions, Laws and Ceremonies of the Most Noble Order of the Garter (London 1672), 205–06. After his execution in 1388 Simon Burley was buried in the Cistercian abbey church of St Mary Graces, not St Paul’s Cathedral. See Hector and Harvey, The Westminster Chronicle, 290–92. This misattribution has been the cause of much subsequent confusion. The correct identification of Richard Burley’s monuments was recognized by J. Stow, Survey of London, 3 vols (London 1908–1927), I, 336, and in more recent literature by Beltz, Memorials of the Most Noble Order of the Garter, 289 and P. Begent, ‘A Note upon the Practice of encircling Arms with the Garter’, The Coat of Arms N.S. 8, no. 144 (1989), 186–95.

51 Registrum Johannis Gilbert), 109–12.

52 O. D. Harris, ‘“Une tresriche sepulture”: The tomb and chantry of John of Gaunt and Blanche of Lancaster in Old St Paul’s Cathedral’, Church Monuments, 25 (2010), 7–35.

53 Walker, Lancastrian Affinity, 102.

54 Begent, ‘A Note upon the Practice’, n. 48.

55 Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Top. Gen. d.19, fol. 300v. The anomalies in the visual evidence occur in the treatment of the gables of the narrower east and west bays. In both gables Sedgwick, likely to be the more reliable witness, as he saw the monument prior to its destruction, depicts the undifferenced arms of Burley encircled fully by a garter with its motto; Hollar shows the impaled arms of Burley and Stafford, but with a garter without a motto that does not fully enclose the shield.

56 J. Harvey, English Medieval Architects: A Biographical Dictionary down to 1550 (Gloucester 1984), 366 (although the reference incorrectly attributes the monument to Simon Burley). I am grateful to Professor Christopher Wilson for discussing this with me in email correspondence, 25 June 2022: ‘I would be very surprised if there were any large architectural monuments in south-east England dating from the late 14th century that were not designed by Yevele.’

57 Harris, ‘The tomb and chantry of John of Gaunt’, 11–13.

58 How it was accessed is not clear, as Hollar’s engraving suggests that the Burley monument filled the full width of the internal bay, although his plan shows it standing forward from the wall and somewhat shorter than the full width of the bay.

59 CPR, Henry IV, 1408–13, 40; C. J. Kitching ed., London and Middlesex Chantry Certificate 1548, London Record Society, 16 (London 1980), no. 109; M. H. Rousseau, ‘Chantry Foundations and Chantry Chaplains at St Paul’s Cathedral in London c. 1200–1545’ (unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of London, 2003), 35–36, 245.

60 S. Brown, ‘Our Magnificent Fabrick’: York Minster, An Architectural History c.1220–1500 (Swindon 2003), 176–87.

61 T. French, York Minster: The St William Window, Corpus Vitrearum Medii Aevi, Summary Catalogue, 5 (Oxford 1999), 17.

62 The scheme includes the arms of known Minster benefactors, including Walter Skirlaw (SIX, 2c) and Thomas Langley (SIX, 2a), as well as those of prominent Minster clergy of an earlier generation, including treasurer, John de Clifford (1375–93, SVIII, 2d), and Richard and John Ravenser (prebendaries of Knaresborough 1371–81 and of Holme 1391–93 respectively, SIX, 2b).

63 A. Gibbons, Early Lincoln Wills (Lincoln 1888), 70–71, 136–77; Testamenta Eboracensia, I, 357–60.

64 French, York Minster: The St William Window, 12–15.

65 This was the location of the high altar throughout the Middle Ages. The altar was moved one bay east in 1726 when the wooden altar screen was removed: F. Drake, Eboracum (York 1736), 173.

66 S. Harrison, ‘The shrines of St William of York reconstructed’, in York: Art, Architecture and Archaeology, ed. S. Brown, S. Rees Jones and T. Ayers, BAA Trans. xlii (London and New York 2022), 1–25.

67 K. Harrison, ‘Illuminating Narrative: An Interdisciplinary Investigation of the Fifteenth-Century St Cuthbert Window, York Minster’ (unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of York, 2019), ch. 3.

68 French, ‘The glazing of the St William Window of York Minster’.

69 Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Top. Yorks. C14, fol. 28r; Oxford, Bodleian Library, Dodsworth MS 137, fol. 12v. The medieval heraldry painted on these shields was replaced when the monument to Sir Henry and Lady Ursula Bellasis was installed immediately below the window in 1624.

70 French, York Minster: The St William Window, 17–19.

71 J. Fowler, ‘On a window representing the Life and Miracles of St William of York, at the north end of the eastern transept of York Minster’, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, 11–12 (1874), 198–348, at 317; E. Milner-White, ‘The return of the windows’, Friends of York Minster Annual Report, 27 (1955), 25–30.

72 As the window was apparently made starting at the bottom, an alteration rather than a production error seems more likely.

73 French, York Minster: The St William Window, 19.

74 Marks of cadency were also deployed with care in the depiction of Scrope heraldry in clerestory window NIX nearby.

75 Beatrice’s oldest brother, Ralph Stafford (d. 1347). The murder of Hugh Stafford’s own oldest son, also named Ralph, was said to have hastened his father’s death: Complete Peerage, XII, 179–80.

76 C. Norton, St William of York (York 2006), xiv, 186; Complete Peerage, XI, 93–94.

77 C. Norton, ‘Richard Scrope and York Minster’, in Richard Scrope: Archbishop, Rebel, Martyr, ed. P. J. P. Goldberg (York 2007), 138–213.

78 Norton, St William, 153.

79 French, York Minster: The St William Window, 107–08 (described prior to conservation when the panels occupied positions 24b and 24c). For what follows I am indebted to Christopher Norton for discussion of his as yet unpublished reinterpretation of the window.

80 Norton, St William, 150–92.

81 Inquisitions Post Mortem Relating to Yorkshire of the Reigns of Henry IV and Henry V, ed. W. Paley Baildon and J. W. Clay, Yorkshire Archaeological Society, Record Series, 59 (Leeds 1918), 107–09; Mapping the Medieval Countryside, King’s College London, 2014. Available at http://www.inquisitionspostmortem.ac.uk/view/inquisition/20-371/388 (accessed 14 November 2022).

82 C. Cross, ‘The last generation of Augustinian Canons in Sixteenth-Century Yorkshire’, in The Regular Canons in the Medieval British Isles, ed. J. Burton and K. Störber (Turnhout 2011), 387–402.

83 Through the marriage of Everard de Roos to Roese, daughter of William Trussebut, lord of Warter: N. Denholm Young, ‘The Foundation of Warter Priory’, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, 21 (1934), 208–13.

84 A. P. Baggs, G. H. R. Kent and J. D. Purdy, ‘Thornton’, in A History of the County of York East Riding: Volume 3, Ouse and Derwent Wapentake, and Part of Harthill Wapentake, ed. K. J. Allison (London 1976), 179–90; at British History Online, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/yorks/east/vol3/pp179-190 (accessed 10 May 2022). The largest number of personal servants rewarded in Beatrice’s will seem to be those associated with her properties in Storthwaite and its immediate vicinity: Inquisitions Post Mortem, 107–09.

85 Ward, Women of the English Nobility, 227–30; the will was proved on 16 May 1415.

86 J. Hughes, Pastors and Visionaries (Woodbridge 1988), 68–69.

87 Itinerary of John Leland, I, 92; J. Burton, Kirkham Priory: From Foundation to Dissolution, Borthwick Paper 86 (York 1995), 2–3, 23; S. Harrison, Kirkham Priory, North Yorkshire (London 2010).

88 Gibbons, Early Lincoln Wills, 70; Itinerary of John Leland, I, 92; Ward, Women of the English Nobility, 223–24. Margaret’s slab was to resemble that which lay over her grandmother, Lady Margaret de Oreby, at St Botolph’s, Boston. Nigel Saul has suggested that this was probably an incised slab rather than a brass: N. Saul, English Church Monuments in the Middle Ages (Oxford 2009), 104.

89 Gibbons, Early Lincoln Wills, 136; Itinerary of John Leland, I, 92. The tomb chests and armoured effigies of both William and John were transferred to the Rutland mausoleum at Bottesford by their descendant: N. Pevsner and E. Williamson, The Buildings of England: Leicestershire and Rutland (London 1992), 105–06.

90 J. Barker, Stone Fidelity. Marriage and Emotion in Medieval Tomb Sculpture (Woodbridge 2020), 152–215.

91 Rawcliffe, ‘Stafford, Ralph’.

92 C. Rawcliffe, ‘Stafford, Hugh, second earl of Stafford (c.1342–86)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/26206 (accessed 14 November 2022).

93 Historical Manuscripts Commission, Twelfth Annual Report, Part IV, The Manuscripts of the Duke of Rutland, vol. I (London 1888), 28–30.

94 Ward, Women of the English Nobility, 229.

95 Historical Manuscripts Commission, Twelfth Annual Report, 28.

96 Ward, Women of the English Nobility, 228.

97 Barker, Stone Fidelity, 127.

98 Harris, ‘Tomb and Chantry of John of Gaunt’, 21–22.

99 Of Beatrice’s affection for her daughter Elizabeth Clifford there can be no doubt, as she made generous gifts to her and her granddaughter Mathilda, who received a silver-gilt covered vessel that had once belonged to Beatrice’s older son, John: Ward, Women of the English Nobility, 228.