Abstract

In 2007 an isolated cist burial was discovered on farmland near Marton-cum-Grafton, North-Yorkshire. An archaeological excavation was undertaken by York Archaeological Trust, funded by English Heritage. The excavation revealed a large cut containing a stone cist, within which a wooden lead-lined coffin had been placed. The skeleton within was of a 30-45 year old male. No grave goods were present within the grave. Cist burials of this type are rare in Britain as a whole, a late third century example from Trentholme Drive in York being the closest comparable example.

Discovery and investigation

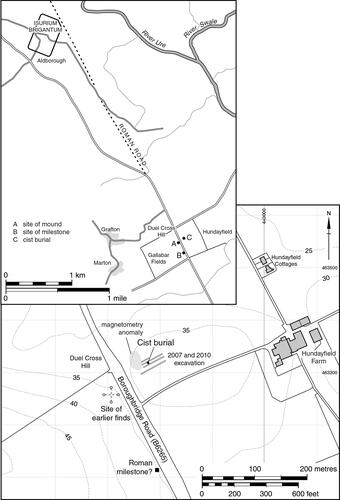

In August 2007 a metal-detectorist, operating with the landowner’s agreement in a field adjacent to the B6265 York – Boroughbridge road (), exposed a corner of what he believed to be a lead coffin, apparently contained within a rectangular structure of coursed masonry aligned NNW-SSE (alignments simplified to ‘north-south’ and ‘east-west’ in subsequent discussion). After reporting and some initial investigation, a small team from York Archaeological Trust (YAT) led by B. Antoni undertook the excavation of the cist and its contents between 17 September and 11 October 2007, with funding from English Heritage (now Historic England; ). A geophysical survey of the vicinity of the cist burial identified only very modern features, detritus and subsurface anomalies considered to be of natural origin (WYAS Citation2007). In September 2010 a small team of volunteers under the supervision of Dr J. Kenny of YAT excavated four south-west to north-east aligned trenches in the vicinity of the cist burial to determine whether or not the cist had originally formed part of a larger cemetery (YAT Citation2020).

Site and setting

The cist was located at SE 4280 6330, 3.5 km south of the village of Aldborough, the site of the Roman civitas capital Isurium Brigantum (Wacher Citation1995, 401-7), and 50 m east of the modern B6265, which on this stretch directly overlies Dere Street, the Roman road from York (Eboracum) to Catterick (Cataractonium) (Margary Citation1973, 427-8; M8a). About one kilometre to the north of the site the B6265 veers westwards whilst the line of Roman Dere Street continues straight on to Aldborough, passing close by the town to the south-west on its route northwards (; Ramm, Addyman, and Black Citation1984, 43). The cist was sited on a low spur of land projecting eastwards into the Vale of York at a height of about 35 m above Ordnance Datum. The subsoil on the site consists of glacially-derived sands.

In the near vicinity of the cist, west of the B6265, there was once a large mound named Duel Cross Hill, described by Edwin Hargrove in 1787 as being 18 feet high with a 370-foot circumference (5.5 m high and 113 m in circumference, a diameter of 37.5 m), and his map of 1809 located the mound to the immediate south-west of the York – Boroughbridge road (Ramm, Addyman, and Black Citation1984, 43-44, quoting Hargrove in 1787). The mound appears to have been levelled completely before the survey for the 1855 first edition Ordnance Survey map was undertaken, having been ‘broken into, some time since, to supply materials for the high road leading from Aldborough to York’ (ibid., 43). It is not known whether Duel Cross Hill was a natural or man-made feature. There are several examples in Yorkshire of prehistoric (primarily Bronze Age) barrows having formed a focus for later burials (Lucy Citation2000, 126-8); the comment on the 1855 Ordnance Survey map ‘Urns and Human Bones found here’ suggests its use for burial at some point in the past, attributed to the Anglo-Saxon period by Hargrove on grounds which are uncertain (North Yorkshire County Council Historic Environment Record entry MNY 18433). The site of a Roman milestone of Trajan Decius (AD 249-51), a cylindrical stone pillar 1.5 m in height with a diameter of 280 mm, has been located 183 m south-west of the site of Duel Cross Hill (Collingwood and Wright Citation1965, 2276; Ramm, Addyman, and Black Citation1984, 43).

To the west, quarrying of the hilltop immediately to the south of Grafton and to the east of Marton in the 1950s exposed the footings of curvilinear structures and an enclosing wall, apparently of Iron Age date (Waterman, Kent and Strickland Citation1955, 383–397). A cropmark on an aerial photograph of the mid-1970s indicates a rectilinear enclosure, identified as probably being of Iron Age or Romano-British date, in a field immediately to the east of Hundayfield Farm, 400 m from the cist burial (North Yorkshire County Council Historic Environment Record entry MNY 18491). In 1979 the Bishop Auckland to Towton gas pipeline was laid through the field containing the cist burial, less than 100 m to the east of it. A resistivity survey over an area of 100 m2 was undertaken in advance of the pipeline construction, seemingly incorporating the study site, but it was concluded that the observed features had been created by modern sheep pens measuring 3.6 m × 2 m. It is striking, however, how closely these measurements match those of the cist. It may be that inaccuracies in plotting led to the cist burial being missed by the geophysical survey, as the stone blocks of the cist would seem to form a target which would be eminently detectable by geophysics against the background of glacially-derived sands.

The cist, coffin and associated features

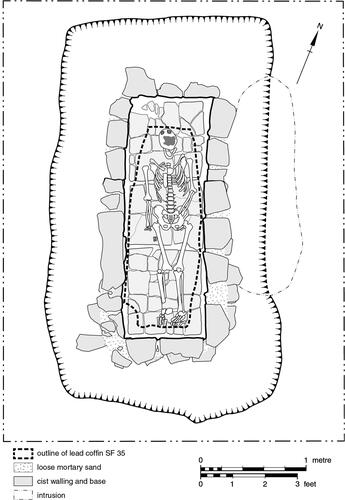

The cist was set in a wide, shallow, flat-based construction cut, measuring 3.8 m north-south, 2.0 m − 2.2 m east-west and 0.4 m − 0.6 m deep. The cist was placed centrally within this cut on a north-south alignment, its maximum external and internal dimensions being respectively 2.9 m x 1.4 m and 2.3 m x 0.7 m. Four complete courses of the red sandstone masonry of the cist survived with a fifth uppermost course intact across its southern half, the rest presumably destroyed by ploughing. The masonry courses were separated by a thin layer of coarse sand and pea-gravel containing only sparse mortar and had been laid to create very regular, vertical-sided internal faces to a maximum height of 0.4 m.

The internal face of the lowest course abutted a rectilinear base of over fifty closely-packed fragments of red sandstone, ranging between 100 mm x 50 mm and 450 mm x 300 mm in size and approximately 100 mm thick. These fragments originally formed three slabs, each measuring approximately 0.7 m east-west and between 0.7 m and 0.8 m north-south which had become fragmented post-deposition, presumably as a result of the great weight of the coffin. Unfortunately many of these fragments had to be removed in order to lift the lead coffin intact following the dismantling of the cist. It was not possible therefore to photograph this base in situ, and it had to be reconstructed from the fragments after the lifting operation had been completed.

The external faces of the cist were highly irregular ( and ) indicating that they were not meant to be seen. The backfill deposits between the cist and cut comprised horizontally banded layers of reddish-brown sand, pebbly gravel, yellow-brown sand and cobbles and fragments of red sandstone, indicating the construction cut was backfilled a course at a time, presumably to help with stability.

Figure 4. The skeleton within the lead coffin-lining, showing detail of the three slabs which formed the base of the cist.

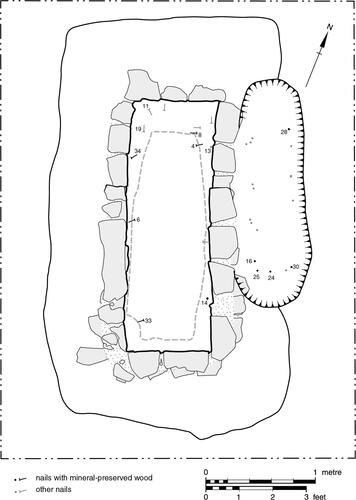

When the construction of the cist had been completed the lead coffin, originally measuring 1.9 m x 0.42 m x 0.35 m in depth, had been placed in the cist. Excavation revealed a gap of about 150 mm between the sides of the coffin and the internal elevation of the cist. The recovery of thirteen iron nails from the layers of sandy silt which had accumulated within the cist indicates the presence of a wooden box or frame around the lead coffin which would have occupied some of this gap (). The majority of the nails were located around the northern (head) end of the burial, but there was also a pair mid-way down the length of the cist and two more at its southern (feet) end. In addition, three unstratified nails were retrieved from this area of the cist before formal archaeological excavation began.

Figure 5. The secondary grave in relation to the cist, showing the positions of iron nails within both graves; numbered nails referred to in the text.

The lead coffin had become severely crushed and misshapen by the collapse of ten large, irregularly-shaped slabs of red sandstone, individual fragments measuring between 0.3 m x 0.2 m and 0.7 m x 0.4 m and between 100-150 mm thick (). Prior to their collapse these irregular fragments had formed one or more regularly-shaped slabs covering the cist. The collapsed fragments did not extend as far as the northern and southern cist walls, and it seems certain that similarly large fragments had been removed from these locations, presumably after disturbance by ploughing. Taking this into account, the most likely reconstruction is of two regularly-shaped slabs of red sandstone, each measuring about 1.2 m north-south by 1 m east-west. The loss of the northern slab is consistent with the absence of the fifth, uppermost course of the cist wall in the northern half of the structure, indicating a greater depth of plough-disturbance in this area.

Figure 6. The cist burial viewed from the north, showing the covering slabs collapsed onto the underlying lead coffin lining.

Apart from the iron nails, no artefacts were found within the stone cist, the sediments it contained, nor the backfill of its construction cut; nor was anything accompanying the skeleton retrieved when the lid of the lead coffin was removed and its contents excavated under laboratory conditions. Palaeoenvironmental analysis of sediment from six contexts did not retrieve any remains of interpretative value.

Hard against the eastern wall of the cist and truncating the backfill deposit of the cist construction cut was a linear feature 1007, measuring 1.8 m north-south by 0.6 m east-west, and 200-250 mm deep (). Within the backfill of this feature (1006) were seventeen iron nails, arranged in two north-south aligned rows close to the eastern (six nails) and western (ten) edges of the feature, with a single nail located centrally close to its southern edge. The arrangement of the nails indicates the presence of a nailed wooden box with minimum dimensions of 1.3 m x 0.4 m. The shape and dimensions of feature 1007, its location immediately adjacent to the cist burial on a common orientation, and the apparent original presence of the wooden box, suggest that this feature was a grave, though no human bone was recovered from its backfill, in the field or in the post-excavation sieving of a 10 litre sample from 1006. This absence may be accounted for by the impact of ploughing and the effects of the acidic sandy subsoil.

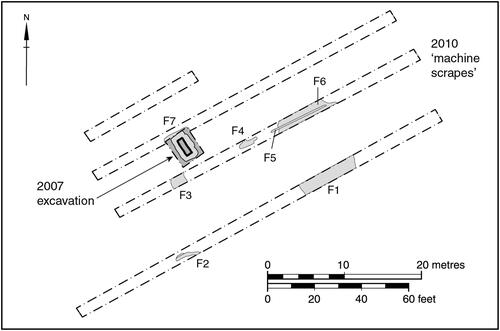

In September 2010 four machine-excavated trenches measuring between 15 m and 55 m in length and 2 m wide were dug in the vicinity of the cist to determine whether or not associated features were present (YAT 2010). The surface of the natural was trowelled clean to establish the presence of any features, but there was no intention to excavate any features exposed. The operation revealed a handful of soil-marks, with only one being a potential grave; a north-east to south-west aligned soil mark (, feature F4) measuring 2 m x 0.6 m, some 8 m due east of the cist, although this is a very uncertain interpretation. Of the other features recorded, F2 and F3 were adjudged to be variations in the natural substrate and F5 was clearly a deep plough scar or field drain extending across F6 and into F4. It is possible that the large features F1 and F6, each measuring 8 m east-west in adjacent machine trenches represent a single very large feature extending over a minimum of 10 m north-south, possibly part of a backfilled sand-pit.

The lead coffin/lining, from a report by Ian Panter and Antoni (Citation2008)

The lead coffin was retrieved intact following the dismantling of the surrounding stone cist. After consolidation and reinforcement it was carefully lifted out of the trench using a JCB and transported to YAT’s conservation laboratory in York.

Detailed examination indicated that the overall condition of the coffin was poor. Physical deformation and damage had occurred as a result of the collapse of the overlying stone cist capping, which had crushed the coffin lid and the two side panels, forcing the lid downward towards the base of the coffin, although the end panels had prevented its complete collapse. The eastern side had been flattened inwards, the western side outwards. The two end panels had suffered the least physical damage, although they had undergone slight deformation ( and ). The lead was covered in a thin powdery off-white carbonate crust and residual soil, and an examination of the broken edges revealed that the metal had undergone complete mineralisation, leaving the lead extremely brittle with no inherent flexibility and consequently fragile and prone to fracturing.

Figure 7. The lead coffin-lining in the final stages of cleaning and conservation prior to the removal of its cover and the excavation of the skeleton within.

The coffin proved to have been constructed from two sheets of lead, one formed to make the coffin itself, the second the lid. The lead sheet for the coffin was 5 – 6 mm thick, cut to dimensions of 1.9 m x 1.1 m with rectangular projections, measuring 0.35 m x 0.42 m, located centrally on each short side to form the end panels of the coffin. This single sheet was then folded, rather in the manner of a ‘flat-pack’ cardboard carton, to bring the end and side panels together in basic butt joints, creating a rectilinear box varying between 0.32 m and 0.35 m in internal depth and with an internal width of 0.37 m at the ‘head’ end and 0.42 m at the ‘feet’ end. There were no traces of these butt joints having been soldered or even ‘crimped’ together to secure them. The lead used for the lid was 3 – 4 mm thick, measured 2 m x 0.52 m, and was simply laid over the top of the coffin with its overhanging edges folded down to cover it. There was no indication that the coffin had borne any form of surface decoration.

Even on its own, without a body inside it, this would clearly have been a very heavy object, weighing approximately 200 kg. Equally apparently, if lifted it would not have been able to support its own weight (let alone that of an adult human body as well) and resist the metal’s inherent flexibility: it would have slumped and folded. It must therefore have been contained within a more rigid structure, presumably constructed of the wood represented by the assemblage of iron nails retrieved from within the cist.

The iron nail assemblage by Heather Stewart and Steven James Allen

Thirteen iron nails were retrieved from the sediments surrounding the lead coffin within the cist, and a further seventeen from 1006, the backfill of the secondary feature 1007. Additionally, three nails which had been removed by the finder and landowner before contacting YAT were handed to the excavation team at their first site visit. Although the exact provenance of these was not recorded on plan, they are known to have come from close to the southern end of the cist.

Of the total assemblage of thirty-six nails recorded in the excavation, three were represented only by iron stains in the soil, from which nothing solid could be retrieved. Of the remainder, twenty-one proved on examination under a microscope to preserve wood grain in their corrosion products: eleven of those recorded in situ in the cist burial, the three retrieved by the landowner and finder from the cist burial, and seven from the rows of nails in the secondary feature ().

Certain identification of wood species was possible in five instances from the cist burial (including two of the three nails retrieved before controlled excavation commenced), with probable identification of a further three examples, and five nails from the secondary feature 1007 were certainly identified to species. In every instance the species was oak (Quercus).

Although the disintegration and total decay of the wood, and the subsequent collapse of the covering slabs into the cist, meant that virtually all of the nails are likely to have been moved to some degree from their original positions, in most instances they nevertheless appear to have remained close to them. Microscopic examination indicates that the side-planks of the coffin were nailed laterally to its base (as indicated by the wood-grain preserved on nail 13; ), and that the end-boards were subsequently added, nailed directly into the end-grain of the sides and base (as indicated by nails 11 and 19), to create a rigid box. The collapse of the wooden coffin as it decayed, and the consequent dropping of nails from its upper edges, means that it is impossible to be certain whether this wooden coffin also had a nailed-on lid.

The distribution of the nails recovered from the secondary feature 1007 () suggests that most were recovered from close to their original positions, with the evidence of wood-grain on the nails indicating a variation in the method of coffin construction. Nail 24 was clearly located in the middle of the southern end of the coffin. Had the coffin been constructed in the same manner as that in the stone cist, the surviving wood-grain on the nail shaft would have shown that the nail had been driven through the side-grain of the oak end-board and into the end-grain of the base. In fact, however, this nail was clearly driven through the side-grain of the end-board into the side-grain of another piece of wood, indicating that this second piece of wood was aligned laterally, rather than longitudinally, to the coffin. This seems to require the presence of a short, lateral batten internal to the southern end of the coffin, to which the base-plank, side-planks and end-board had been nailed. In such construction nail 30, at the extreme southern end of the eastern side-plank, would have been nailed into the end-grain of this batten, as the wood-grain impressions which it bears do indeed indicate.

The skeleton, from a report by Dr Rebecca Storm (Citation2014)

The lead coffin having been lifted intact following the dismantling of the surrounding stone cist, the skeleton it contained was cleaned in situ, lifted at YAT’s premises in York in 2007 and analysed macroscopically in June 2014.

Osteological analysis

The skeleton was >75% complete, with all skeletal elements represented except for a few facial bones, carpals, metacarpals, phalanges, and the right patella. Overall preservation was poor to moderate, largely due to the collapse of the stone cover of the cist which had squashed the lead coffin and crushed the skeleton within it. The facial area and cranial base of the almost-complete skull were highly fragmentary, the vault suffering mild post-mortem deformation. Post-cranially, only the clavicles, right humerus, metatarsals and pedal phalanges were found to be in a complete state, all other bones had a degree of fragmentation due to post-mortem breakage, and many bone surfaces were found to have uninformed bone surface erosion, fibrous and rough in texture with some flaking and splintering. In most proximal and distal ends of the long bones and in a number of vertebrae cancellous bone is exposed. The only elements having good to excellent preservation are the right humerus, right scapula, and both clavicles.

Overall morphological traits and metrical analysis indicated the individual to be male. Comparison of the age-at-death indicators provided by pubic symphysis, auricular surfaces and sternal rib morphology (dental ware having been discarded as an indicator due to the possibility of ante-mortem tooth loss having affected molar wear pattern) indicated an age-at-death in the range of thirty-six to forty-five years, probably towards and perhaps slightly beyond the upper end of that age-range. The length of the right humerus gave a living height of 1.71 m ± 41 mm, fitting closely with the average male stature of 1.59-1.78 m reported for Roman Britain (Roberts and Cox Citation2003).

Palaeopathology

Dental pathology

The maxillae, mandible and a total of twenty-five teeth were available for analysis for evidence of calculus, enamel hypoplasia, caries, periodontal disease, and dental anomalies (see Hilson Citation2005). The individual lost teeth 23, 26 and 27 ante-mortem, and there was pitting/porosity and partial absorption of the sockets for the posterior teeth on both sides of the maxillae. A build-up of bone on the alveolar bone buccal and lingual aspects of the maxillary dentition indicates extensive lateral movement of the jaw. Some calculus was present on the buccal and labial surfaces of all of the mandibular teeth, but poor preservation of the maxillary teeth meant that it was not possible to determine if it had been present ante-mortem. The calculus largely prevented identification of the presence of dental enamel hypoplasia, thought to be associated with nutritional or pathological stress, although hypoplastic lines were located on 33, 43, and 44, with 44 also being pitted. Three carious lesions were present, two on adjoining interproximal surfaces of 24 and 25 and a large one on the mesial interproximal surface of 46. Mild periodontitis affected the whole of the mandibular dentition. There appears to be a congenital absence of all four third molars, although in the absence of radiographs it is possible that they were present but failed to erupt.

Degenerative change

Few degenerative changes, usually the result of ageing and mechanical stress and strain during life, were observed. Minimal osteophytosis was observed on the margins of the right acetabulum and glenoid cavities, manubrium and right third rib. Very slight joint surface pitting was located on the sternum, right third rib, clavicles, and right olecranon processes of the ulna. The metatarso-phalangeal joint of the first right proximal pedal phalanx was cupped with considerable osteophytic lipping. There were indications of strong dorsal muscle attachments proximally. The right first metatarsal had nodules of bone present centrally on the plantar surface of the head. It is possible that post-mortem damage may have obscured further pathological change. Overall this limited degenerative change conforms with the age-at-death suggested above.

Trauma

The individual had suffered a compression fracture of the twelfth thoracic vertebra resulting in considerable loss of anterior body height, extension and pitting of the inferior rim, and eventual osteophyte formation of the anterior margins of the body.

Developmental conditions

Large cortical defects were present in the acetabulae, the right measuring 11.9 mm superoinferior and the left 5.7 mm superoinferior by 10.6 mm anteroposterior. Such defects in the cortical bone are benign and symptomless.

Conclusion

Overall the body in the cist, of a 30 – 45 year old male standing 5′ 5½” − 5′ 8½” (1.67 m − 1.75 m) tall, appears to be of an individual who experienced good-to-average health in the course of his life, with evidence for only minor pathological change. Isotope analysis undertaken by Durham University (Moore et al. Citation2018) indicates that the individual was a migrant to Roman Britain, likely from a region with a warmer, drier climate and suggesting a childhood spent in areas of southern Europe such as the Iberian Peninsula or southern Italy.

Discussion

The coffin and burial

It is clear that the lead coffin would not have been a self-supporting structure, and could only have been moved and carried if placed within a rigid container; the nail assemblage indicates a nailed oak box. The unit as a whole should therefore be described as a ‘lead-lined oak coffin’ rather than a ‘lead coffin’. The evidence of the wood-grain preserved in the iron corrosion-products of the nails indicates some of the construction features of the lead-lined oak coffin within the stone cist, and some slight but interesting differences with the coffin subsequently placed in a secondary grave immediately adjacent to the cist. The weight of the lead-lined oak coffin with an adult male body inside it should also be noted; combined, the adult male corpse (estimated weight about 74 kg), lead lining (estimated weight about 200 kg) and oak coffin (assuming a board thickness of up to 25 mm, estimated weight about 79 kg) would have been somewhere in the region of 353 kg.

Comparative evidence

The Marton-cum-Grafton cist burial is an example of the rare Philpott Type 1 cist inhumation burial, defined as cists constructed of coursed masonry with covering slabs, ‘structurally the most sophisticated cist found in Britain’ (Philpott Citation1991, 61). Philpott’s corpus cites only two certain examples from Britain, one from Conderton, Worcestershire, like Marton-cum-Grafton an apparently isolated interment, the second from the extensive cemetery at Trentholme Drive, York, excavated in 1951-2. Two other possible examples were noted at Beckfoot, Cumbria, and Thirst House Cave, Derbyshire, although these were insufficiently preserved to be certain of the identification as Type 1 cists (and the latter, as illustrated in The Reliquary 1897, 99–101, is in fact rather different in character). The inclusion of a lead lining to the coffin makes the Marton example all the more unusual. Lead linings/coffins are well attested within the urban centre at York (RCHME Citation1962), but are rare in the region outside of the city (Taylor et al. Citation1993; Toller Citation1977).

The Conderton cist, dated by a coin of Lucilla or Faustina II to the early-/mid-third century AD, appears never to have been fully reported, although some details, accompanied by photographs, appear in the Illustrated London News of 9 Nov 1963. From this it can be seen that the cist was constructed in similar fashion to Marton with at least 6 courses of unmortared masonry where best preserved. The inhumation was that of an adult male, the survival of nails indicating interment in a wooden coffin. The Trentholme Drive cist provides the best comparison with Marton-cum-Grafton, however, being the most completely documented (Wenham Citation1968, 42-44, 130; Figures 14-15; pls XII and XIII). It contained a near-complete adult male skeleton at least thirty years of age, lightly-built and standing about 5’7” − 5’8” (1.73- 1.76 m) in height. The man was interred in a stone cist, within which forty-nine iron nails indicate the presence of a wooden coffin (without a lead lining). The dimensions of the construction cut for the cist are closely comparable to those from Marton-cum-Grafton, but the cist itself was slightly shorter, narrower and taller, although the height is more likely to result from differential survival rather than original form.

Close similarities in construction of the cists from Trentholme Drive and Marton-cum-Grafton are readily apparent and allow them to be regarded as potentially broadly contemporaneous, dating to the second half of the third century AD. The covering slabs of the York example are described as resting on the fifth course, and at Marton-cum-Grafton the fifth course was the uppermost to (partially) survive; also the covers of both cists comprised two slabs of comparable size. Unlike the unaccompanied Marton-cum-Grafton inhumation, the Trentholme Drive cist contained a Nene Valley Colour Coated Ware Funnel-necked indented beaker with a suggested date-range of c. AD 225 – 280 (Monaghan Citation1997, Figure 391.3896, 865). Wenham attributes a coin of Gallienus (r. AD 253 − 68) to the backfill of the Trentholme Drive cist (Wenham Citation1968, 44, 90), which accords with the date suggested by the indented beaker and provides a terminus post quem for the cist’s construction of AD 253.

If the construction of the two cists is comparable, the better preservation at Trentholme Drive suggests elements that may have been lost through the plough-damage seen at Marton-cum-Grafton. Wenham’s report, however, confuses the depth of the cist below the probable level of the Roman ground surface, by implying that the top of the cist was 4′ 0” (1.22 m) below the contemporary ground surface (ibid., 44). It is more likely, as also stated in the report (ibid., 15), that it was in fact the base of the cist which had been dug to this depth. This seems far more plausible, is consistent with the depth of other burials in the vicinity, and would place the uppermost course and cover of the cist at a depth 1′ 6” (0.46 m) below Roman ground level. At this depth, loose stones found above the head end of the cist may have formed packing for an upright grave marker which has subsequently disappeared. As with many Romano-British urban and military settlements, numerous such gravestones are known from the environs of Roman York, including several recovered from The Mount area within 200 m of the Trentholme Drive cist burial.

It seems highly likely that a structure of the complexity seen at Marton-Cum-Grafton would have been marked by some form of recognisable above-ground monument. This could have been a headstone (and footstone?) as suggested at Trentholme Drive, or conceivably a more elaborate tomb-like structure. This is obviously relevant to the presence of the secondary feature, interpreted as a grave also containing a wooden coffin, which was dug hard against the eastern side of the cist and implies that its location was still remembered and/or was visible.

Comparison of funerary traditions between the cist burials of this period is limited by the variable preservation of evidence. Acidity of the soil at Marton-cum-Grafton has largely destroyed any organic remains, unlike the Conderton Type 1 cist burial which contained at least three pairs of shoes (Philpott Citation1991, 174). There does, however, appear to be a similar concern with the preservation of the body after burial at Marton-cum-Grafton and Trentholme Drive, with the provision of a lead coffin at the former and the latter being sealed beneath 130 mm or more of pure clay.

A final consideration is the weight of the coffined burial at Marton-cum-Grafton when it was laid in the ground. With a total weight of over 353 kg it would surely have been far too heavy to have been lifted by hand, let al.one carried manually any distance. Even if the coffin was assembled on site it is likely that the various components were transported to the graveside by cart.

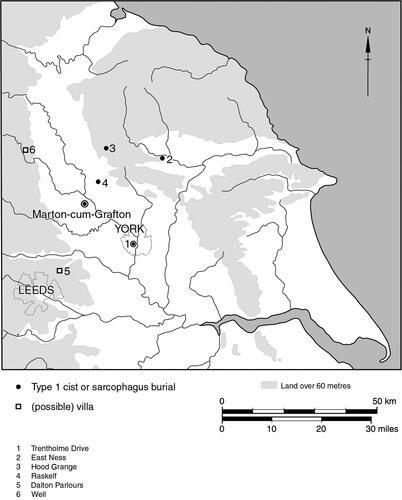

Although the Type 1 cist is a rare provision, high status burials within stone sarcophagi and/or lead coffins are rather more prevalent. York is well provided with such, a reflection of its status as an urban centre (and provincial capital) (RCHME Citation1962). Examples in a rural context in Yorkshire are less common but widespread and include two stone sarcophagi bearing Latin inscriptions from East Ness in upper Ryedale, 10 km north-west of Malton (RIB720, now lost; Kitson-Clark Citation1935, 79) and Hood Grange, near Thirsk (Wenham Citation1960, 298–300; RIB3209). In addition, three stone coffins of apparently Roman date are reported as having been discovered near Raskelf (Kitson-Clark Citation1935, 121), 4 km west of Easingwold in the Vale of York and only 10 km from Marton-cum-Grafton.

Conclusion

Philpott Type 1 cist burials are rare discoveries, with only two other comparable Romano-British examples recorded, one quite nearby in the region at York. The additional inclusion of a lead lining at Marton cum Grafton appears unique to this case. Other high-status inhumations in the Yorkshire region are represented by stone sarcophagi and/or lead coffins (Toller Citation1977; Philpott Citation1991, 61). These are strongly represented in the urban centre of Eburacum, but uncommon, if relatively widespread, without. An association of such high status rural burials with high status, i.e. villa, settlement sites might be supposed (Smith et al. Citation2018, 249); the question remains whether southern European origin and high status are linked in this case (cf McKenzie and Thomas Citation2020, 119–121) and what connection that might imply to the community at York.

Although no potential villas have yet been identified closer than Well (Gilyard-Beer Citation1951) and Dalton Parlours (Wrathmell and Nicholson Citation1990), both c.25 km distant from Marton-cum-Grafton (), it is surely in such a context that the currently very fragmentary evidence for high-status later Romano-British burials in the region, whether isolated or in small cemeteries, should be researched and understood.

Acknowledgements

The main author would like to thank all of the named contributors for both their formal reports and broader discussions of the burial. Bryan Antoni and Jim Williams (of YAT) undertook the 2007 excavations and Lesley Collett prepared the text figures for publication. Nick Wilson of Hundayfield Farm provided much helpful comment and information. Gail Falkingham and L. Matthews of North Yorkshire County Council provided invaluable help in accessing and interpreting the evidence held in the county’s Historic Environment Record. English Heritage generously provided grant support for the excavation, assessment, analysis and publication, with Dr Peter Wilson guiding the project through all of these stages. Jane McComish and Steve Malone of YAT edited the text.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mark Whyman

Mark Whyman at the time of writing was a Senior Project Officer with York Archaeological Trust.

References

- Collingwood, R. G., and R. P. Wright. 1965. The Roman Inscriptions of Britain I Inscriptions on Stone. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Gilyard-Beer, R. 1951. The Romano-British Baths at Well. Research Report No.1. Leeds: Roman Antiquities Committee of the Yorkshire Archaeological Society.

- Hilson, S. 2005. Teeth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kitson-Clark, M. 1935. A Gazetteer of Roman Remains in East Yorkshire. Leeds: Roman Antiquities Committee of the Yorkshire Archaeological Society.

- Lucy, S. 2000. The Anglo-Saxon Way of Death: Burial Rites in Early England. Stroud: Sutton.

- Margary, I. 1973. Roman Roads in Britain. 3rd ed. London: Phoenix House.

- McKenzie, M., and C. Thomas. 2020. In the Northern Cemetery of Roman London. Excavations at Spitalfields Market, London E1, 1991-2007. London: Museum of London Monograph, 58.

- Monaghan, J. 1997. Roman Pottery from York. The Archaeology of York 16/8. York: Council for British Archaeology.

- Moore, J., J. Montgomery, J. Evans, and G. Nowell. 2018. York Lead Coffin Burial Isotope Report. Durham: University of Durham Archaeological Services.

- Panter, I. 2008. “Assessment of the Lead Coffin.” In Hundayfield Farm, Marton-cum-Grafton, North Yorkshire, Assessment Report, edited by B. Antoni, 25–27. York: York Archaeological Trust. Report 2008/9.

- Philpott, R. 1991. Burial Practices in Roman Britain: A Survey of Grave Treatment and Furnishing AD 43 – 410. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports British Series 219.

- Ramm, H. G. 1984. “The Duel Cross Milestone and Roman Roads West of York.” In Archaeological Papers from York Presented to M.W. Barley, edited by P. V. Addyman and V. E. Black, 43–45. York: York Archaeological Trust.

- RCHME. 1962. An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the City of York. Volume 1: Eburacum Roman York. London: HMSO.

- Roberts, C. A., and M. Cox. 2003. Health and Disease in Britain: From Prehistory to the Present Day. Stroud: Sutton.

- Smith, A., M. Allen, T. Brindle, M. Fulford, L. Lodwick, and A. Rohnbogner. 2018. Life and Death in the Countryside of Roman Britain. Britannia Monograph 31. London: The Roman Society.

- Storm, R. 2014. Osteological Analysis of the Human Skeletal Remains from Hundayfield Farm, Marton-Cum-Grafton, North Yorkshire. Bradford: University of Bradford Biological Anthropology Research Centre.

- Taylor, A., M. Green, C. Duhig, D. Brothwell, E. Crowfoot, P. W. Rogers, M. L. Ryder, and W. D. Cooke. 1993. “A Roman Lead Coffin with Pipeclay Figurines from Arrington, Cambridgeshire.” Britannia 24: 191–225. https://doi.org/10.2307/526728

- Toller, H. 1977. Roman Lead Coffins and Ossuaria in Britain. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, 38.

- Wacher, J. 1995. The Towns of Roman Britain. 2nd ed. London: Batsford.

- Waterman, D. M., B. W. J. Kent, and H. J. Strickland. 1955. “Two Inland Sites with ‘Iron Age A’ Pottery in the West Riding of Yorkshire.” Yorkshire Archaeological Journal 38: 383–397.

- Wenham, L. P. 1960. “Seven Archaeological Discoveries in Yorkshire.” Yorkshire Archaeological Journal 40: 298–328.

- Wenham, L. P. 1968. The Romano-British Cemetery at Trentholme Drive. York. Ministry of Public Buildings and Works Archaeological Reports No.5. London: HMSO.

- Wrathmell, S. and A. Nicholson, eds. 1990. Dalton Parlours: Iron Age Settlement and Roman Villa. Wakefield: West Yorkshire Archaeology Service, 3.

- WYAS. 2007. Hundayfield Farm, Marton-Cum-Grafton, North Yorkshire: Geophysical Survey Report No. 1735. Wakefield: West Yorkshire Archaeology Service.

- YAT. 2020. Hunday Farm Strip Trenching September 2010. York: York Archaeological Trust.