Abstract

Brands increasingly address social inequalities by means of advertising. Inclusive advertising can, however, damage brands if consumers suspect insincere and extrinsic motivations. For instance, many companies that have engaged in identity-targeting advertisements face ‘washing’ accusations, particularly by members of the targeted social group. Still, our understanding of how these vested stakeholders determine whether brands are washing remains superficial. Further, little is known about when perceptions of washing lead to a loss of approval by the targeted community. Analyzing interviews with 24 LGBTQ+ individuals, we found that vested stakeholders construct motivational attributions guided by the salience of their minority identities. Specifically, respondents with highly salient minority identities sourced cues from both the advertisements and the advertisement’s organizational context to inform the attributions on which they base their washing perceptions and the corresponding negotiation of social approval. Thus, we highlight how identity salience influences the evaluation of targeted advertisements and outline which cues minority consumers employ to inform their motivational attributions and washing evaluations. We also discuss when perceived washing can lead to a loss of the target communities’ social license to operate (SLO), thereby engaging in theory building by integrating self-categorization theory (SCT) and attribution theory into the SLO framework.

In recent years, the phenomenon of brands addressing social inequalities by means of advertising, which we term inclusive advertising, has become increasingly prevalent (Taylor Citation2022; Viglia et al. Citation2023). While some scholars argue that brands are intrinsically motivated to promote inclusivity (Wilkie et al. Citation2023), others outline that they might be succumbing to social pressures to position themselves in polarized sociopolitical debates (Van Der Meer and Jonkman Citation2021) or are attempting to profit from performative inclusivity (Li Citation2021; Wulf et al. Citation2022). Similarly, consumers are often uncertain about brands’ motivations behind inclusive advertising and increasingly articulate public criticism in the form of washing accusations (Pope and Wæraas Citation2016).

A notable example of corporate washing is the proliferation of brands incorporating LGBTQ+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer +) symbols and imagery in advertisements without substantiating this representation with supportive policies or external advocacy for LGBTQ+ rights (Ciszek and Lim Citation2021; Li Citation2021). Such advertising is often labeled rainbow-washing, and consumers perceive it as an insincere attempt at performative allyship through which companies exploit minority communities for financial gain (Li Citation2021). These accusations are critical for brands, as advertising scholars have highlighted that perceived washing is associated with negative evaluations of ads and brands (Schmuck, Matthes, and Naderer Citation2018). Previous research has focused on identifying company characteristics that are associated with washing perceptions (Ruiz-Blanco, Romero, and Fernandez-Feijoo Citation2021), for instance, corporate environmental performance (Nyilasy, Gangadharbatla, and Paladino Citation2012). Yet, despite some seminal articles (Paço and Reis Citation2012), there is more to learn about consumer perspectives in the context of corporate washing. Specifically, there is scant insight into the way in which consumers construct motivational attributions toward advertisements.

Particularly for inclusive advertising, which often strategically utilizes minority symbols and imagery to convey inclusivity and target minority consumers (Wulf et al. Citation2022), something we term identity-targeting advertising, the role of the targeted minority consumer in constructing washing needs to be better understood. Their perceptions are of particular importance as ‘their’ symbols and imagery are being used in advertising. As such, they are ‘vested’ stakeholders whose approval is critical for brands to gain and maintain their social license to operate (SLO; Wilburn and Wilburn Citation2011). A loss of approval within the vested stakeholder community can lead to undesirable consequences for brands (Boutilier and Thomson Citation2011). Hence, when attempting to understand washing accusations uttered in response to identity-targeting advertising, examining the perceptions of the vested stakeholders—the targeted minority community—is of the utmost importance.

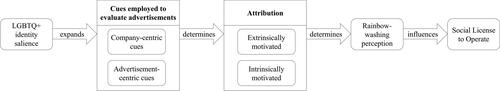

In this study, we explore how a vested stakeholder group (LGBTQ+ consumers) attributes corporate motivations to advertisements and forms washing perceptions. We follow this up with a discussion of when these washing perceptions might lead to a withdrawal of the SLO by the targeted community. Empirically, we used a grounded theory approach to analyze 24 semistructured interviews with LGBTQ+ consumers. Our findings indicate that consumers look beyond the direct messages sent by brands through their LGBTQ+ advertisements. Rather, they use additional advertisement-centric as well as contextual cues to construct their attributions and determine whether they perceive brands to be rainbow-washing. Critically, we find that the salience of their LGBTQ+ identities influences the extent to which they draw upon additional cues, as well as when and how perceived rainbow-washing leads to a withdrawal of SLOs. With these findings, we make four contributions to advertising literature.

First, we advance insights in how minority identities influence the way in which minority consumers evaluate minority-targeting advertising (see Lau and Lee Citation2018; Navarro et al. Citation2019; Shao et al. Citation2023). We highlight that increased identity salience of minority consumers does not necessarily lead to higher advertising effectiveness (as was found in previous studies; Navarro et al. Citation2019) but can expand the cues used to evaluate the advertisements. Second, we advance the understanding of corporate washing in inclusive advertising by delineating the specific cues employed by LGBTQ+ consumers to form motivational attributions and assess rainbow-washing. Third, we introduce the SLO concept to advertising literature to illuminate the evaluative process in which minority consumers engage in when encountering identity-targeting advertisements. We do this by integrating attribution theory into the SLO framework and considering it in tandem with self-categorization theory (SCT). Fourth, we contribute to advertising literature on the outcomes of inclusive advertising by discussing when perceived washing can lead to a withdrawal of the SLO by the targeted community.

Theoretical Framework

LGBTQ+ Advertising and Rainbow-Washing

The LGBTQ+ community (a social minority group that is divergent from the majority in their gender identity and/or sexuality) constitutes the most rapidly growing consumer segment in the United States (Baron Citation2022). This has made them a popular community to target through advertising. Brands place LGBTQ+ symbols and imagery (e.g., rainbow flags) in their advertising (Champlin and Li Citation2020; Milfeld, Flint, and Zablah Citation2022) to target LGBTQ+ consumers in their advertising campaigns. Often, these advertisements are released during June, which is known as Pride Month (Ciszek and Lim Citation2021).

However, LGBTQ+ advertising has garnered criticism recently, because consumers are unsure what motivates these brands to address the LGBTQ+ community in their advertising (Li Citation2021). While many brands portray these advertisements as a way to communicate inclusivity as a brand value (Sobande Citation2019), consumers wonder whether these brands might have alternative, extrinsic motivations, such as trying to benefit from the “queer dollar” (Ginder and Byun Citation2015), or if they are succumbing to societal pressures to claim positions in polarized social debates (Van Der Meer and Jonkman Citation2021) without truly practicing what they preach (Li Citation2021).

As consumers become more critical toward the motivations behind brands’ inclusive advertising campaigns, brands have increasingly been accused of exploiting LGBTQ+ imagery and symbols, rather than representing and uplifting LGBTQ+ people (Li Citation2021). LGBTQ+ consumers have termed this rainbow-washing (Batey Citation2019), referring “to a brand’s use of LGBTQ symbols to only signal their support through advertising, without engaging in further support of this community or their rights. This performative allyship is a method of commodifying a social issue in an effort to make profits, rather than one to produce a change in society” (Champlin and Li Citation2020, 162).

While some studies have explored how the LGBTQ+ community can be targeted in their role as consumers (Eisend and Hermann Citation2019; Ginder and Byun Citation2015), most research on LGBTQ+ advertising examines the effects of LGBTQ+ images on nontarget publics (Ginder and Byun Citation2015), thereby focusing on “identifying possible resistance from heterosexual audiences to the inclusion of the LGBTQ+ community as a target of companies’ marketing goals” (Pinto et al. Citation2020, 13). However, the interest in understanding LGBTQ+ consumers’ responses to targeted advertising has increased (Demunter and Bauwens Citation2023), especially as scholars have become more aware of the importance of the distinct perspective afforded by their LGBTQ+ identities.

The perceptions of LGBTQ+ individuals are of particular importance when ads employ LGBTQ+ symbols and imagery, making LGBTQ+ consumers the vested stakeholders of LGBTQ+ advertising (Wilburn and Wilburn Citation2011). Stakeholder communities are “vested” when an organization claims something the community has a right or a claim to—something they consider “theirs” (Wilburn and Wilburn Citation2011). Thus, in the instance of LGBTQ+ advertising, the main vested community is the LGBTQ+ community. This ‘vestedness’ highlights their relevance in granting social approval, in other words, a social license to operate. While SLOs are outside of legal regulations, they are crucial for companies to avoid undesirable consequences, such as backlash, boycotts, and blockades (Boutilier and Thomson Citation2011).

The SLO and Its Role in Advertising

The corporate SLO is the product of an engagement between corporations and vested stakeholder communities (Wilburn and Wilburn Citation2011) who grant them licenses to operate, meaning they approve of the corporations’ activities (Hurst, Johnston, and Lane Citation2020). Corporations maintain SLOs by engaging with various stakeholder communities with the objective to have them approve of their activities (Gunningham, Kagan, and Thornton Citation2004; Nelsen Citation2006; Parsons, Lacey, and Moffat Citation2014).

The concept of SLOs was developed in the context of the mining industry, where the environmental risks of corporations’ activities led to backlash from local, affected communities. Faced with increasing demands for sustainable development, mining companies had to obtain support from local communities to avoid costly consequences, such as boycotts, blockades, or protests (Boutilier and Thomson Citation2011; Prno and Slocombe Citation2012). This required firms to engage with the affected communities beyond their business-oriented goals to gain their approval (Parsons, Lacey, and Moffat Citation2014). Recently, the SLO concept has been extended to social licenses given or withdrawn by specific stakeholder communities which are not necessarily bound together geographically (as local communities are) but are connected through a claim in a shared issue (Hurst, Johnston, and Lane Citation2020; Van Der Meer and Jonkman Citation2021). SLOs are inherently community specific, because they refer to the approval corporations seek from a community affected by the corporation’s activities.

Beyond local communities, SLOs have been connected to so-called issue arenas. Luoma-Aho and Vos (Citation2010) argue that organization–stakeholder interactions are no longer organization-centric, as the traditional stakeholder model would suggest, but increasingly take place in issue arenas. These issue arenas are actual or conceptual places of interaction among parties who have stakes in a shared issue (Vos, Schoemaker, and Luoma-Aho Citation2014). Corporations enter issue arenas and claim a stake in the issue at hand. Inside the issue arena, corporations engage with stakeholder communities, which are affected by the organization’s behavior in connection to the issue at hand—in particular, vested stakeholders (Wilburn and Wilburn Citation2011). Conceptually, SLOs are very close to notions of legitimacy, as both concepts refer to approval gained through the confirmation to specific norms. The main difference is that legitimacy focuses on public, non-community-specific approval based on broader societal norms and SLOs are characterized by a personal level of approval given specifically by vested stakeholder communities (Gehman, Lefsrud, and Fast Citation2017; Wilburn and Wilburn Citation2011).

There are various forms of approval corporations can gain from vested communities. Vested communities can reject the claims of corporations all together, meaning they disapprove of the organization’s activities, which can lead to costly consequences such as boycotts and protests by the targeted community (Hurst, Johnston, and Lane Citation2020). Beyond that, vested communities can accept the corporation’s claims temporarily, yet remain critical. In those instances, the risk of them withdrawing their acceptance is high (Boutilier and Thomson Citation2011). When vested stakeholders approve of the corporation’s claim, or even begin to psychologically identify with the corporation, the risk of having their SLO withdrawn is quite low (Boutilier and Thomson Citation2011). As such, the process of maintaining SLOs is dynamic, as organizations continuously gain and lose various forms of approval.

Previous work on SLOs has mostly focused on how they are negotiated in public relations, which refers to the management of the relationship between corporations and the public through communication (Marschlich Citation2022). However, perceptions of public relations have become more dynamic and often encompass the engagement between corporations and their environments more broadly (Marschlich Citation2022), thereby highlighting the interconnectivity of advertising and public relations. If brands enter sociopolitical issue arenas by means of advertisements, those advertisements become part of the SLO negotiations. The admission of an SLO can thereby also be contingent on the messages sent in corporate advertising. Consequently, the process of targeted consumers holding brands accountable for their advertising messaging (Li Citation2021) is part of the SLO construction process.

Much research investigating the SLO construction process has done so from the perspective of the corporation aiming to receive a SLO by a vested community (Wilburn and Wilburn Citation2011), often employing stakeholder theory to illustrate how companies can manage vested stakeholders in order to receive their SLO (Gupta and Kumar Citation2018). In this study, we instead focus on how vested stakeholders construct interpretations of the companies’ activities to determine whether they will grant or withhold their SLO. To do this, we integrate attribution theory into the SLO framework to understand how LGBTQ+ consumers come to perceive advertisements to be rainbow-washing and consequently engage in SLO withdrawal. While attribution theory has a long history of explaining washing perceptions (Nyilasy, Gangadharbatla, and Paladino Citation2012), integrating attribution theory into the SLO framework will offer a novel and expanded understanding of the consumer process of vested stakeholders when faced with targeted advertisements.

Attribution theory argues that individuals attribute causes to others’ behavior to explain it and make judgments about it. When attempting to explain others’ behavior, they either attribute it to dispositional (intrinsic) or situational (extrinsic) motives (Jeong Citation2009). In the context of LGBTQ+ advertising, an attribution of dispositional motivations would refer to consumers believing that the brand is intrinsically motivated to make LGBTQ+ advertising, for example, due to genuine concern for the LGBTQ+ community (Ginder, Kwon, and Byun Citation2021). An attribution of extrinsic motivation indicates that consumers believe that the corporation is engaging in LGBTQ+ advertising due to situational factors which are often opportunistic and self-serving, for example, because they perceive it as an opportunity to increase profits by targeting the LGBTQ+ community (Ginder, Kwon, and Byun Citation2021; Li Citation2021).

In line with attribution theory (Nyilasy, Gangadharbatla, and Paladino Citation2012), we pose that when encountering LGBTQ+ advertising, consumers are confronted with uncertainty about the motivations behind these advertisements. Consequently, LGBTQ+ consumers come up with cognitive explanations (attributions) why brands are using LGBTQ+ symbols and imagery in their advertising campaigns. These attributions inform their evaluations of the advertising campaigns and determine their course of action—specifically, whether they grant their approval to the corporation. By positioning attributions as the basis upon which SLOs are negotiated (hence integrating attribution theory into the SLO framework) we gain a clearer understanding of the consumer process of the vested stakeholders.

The perspective of LGBTQ+ consumers is of importance because they are the ones who must grant their SLO to the company engaging in LGBTQ+ advertising. However, their LGBTQ+ identity is important not only because it makes them vested stakeholders, but also because it affords a unique perspective on LGBTQ+ advertising. Previous research on identity-targeting advertisements has shown that advertisements affect individuals holding the targeted identities differently. Similarly, Li (Citation2021) highlighted that there were clear differences in the evaluations of LGBTQ+ advertisements by LGBTQ+ consumers and non-LGBTQ+ consumers. Their social identity, group belongingness, and self-perception are hence critical components of their ad-evaluation process.

Social identity theory (SIT) and its derivative, self-categorization theory (SCT), outline that individuals source part of their identity from memberships in social groups (Ellemers and Haslam Citation2012; Tajfel Citation1974). A social identity is “the part of an individual’s self-concept which [is derived] from his knowledge of his membership of a social group . . . together with the emotional significance attached to that membership” (Tajfel Citation1974, 69). The more important group membership is for sense of self (i.e., the more the identity is salient), the more group members will strive to emphasize this social identity and begin to act and think in terms of the social group (Ellemers and Haslam Citation2012; Turner and Reynolds Citation2012).

We use the term salience to outline the extent to which an identity is important for an individual’s self-concept (Ellemers and Haslam Citation2012). However, identity theories also use it to describe the extent to which identities become situationally salient (i.e., through situational fit; Turner and Reynolds Citation2012). Both conceptualizations of salience argue that the more salient the social identity, the more social group members think and behave in line with norms and values associated with their group, whereas individuals whose social identity is barely salient will demonstrate more variability in their thinking and behavior.

We suggest that the extent to which individuals draw on the specific norms and values associated with their social group (Turner and Reynolds Citation2012) to interpret advertisements making use of the symbols and imagery associated with their social group, will influence their interpretation of these advertisements. We thus suggest that the consumers’ LGBTQ+ identities impact the attributions they form when confronted with LGBTQ+ advertisements, and these attributions are consequently used to deliberate the corporation’s SLO. The integration of attribution theory into the SLO framework will enable a better understanding of how SLOs are constructed. The proposed theoretical relationship is presented in .

Methodology

Our research question required a qualitative and structured yet flexible research methodology. Therefore, we chose an inductive, grounded theory approach (Mattley, Strauss, and Corbin Citation1997). Empirically, we aim to understand how LGBTQ+ consumers construct motivational attributions which led to perceptions of rainbow-washing and when this resulted in the corporation losing their approval. To answer these questions, we conducted interviews in two rounds, with the first round consisting of 15 respondents and the second round consisting of 9 respondents. Conducting the study in two rounds allowed us to examine the data in stages.

We used purposive snowball sampling focused on individuals who identify as LGBTQ+ to overcome skepticism and trust barriers (Browne and Nash Citation2010). The recruitment criteria for respondents required them to identify as LGBTQ+, be above the age of 18, and speak English. The respondents of the first round were recruited via a written message explaining the purpose of this study. Upon agreeing to participate in the study, the respondents were asked to fill out a demographics survey screening them for eligibility. Interviews took place via the online video-call platform Zoom due to the practical constraints of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The second-round participants were recruited by means of theoretical sampling (as is typical for grounded theory informed research; Tie, Birks, and Francis Citation2019) through LGBTQ+ organizations. Theoretical sampling is used to “maximize opportunities to discover variations among concepts and densify categories in terms of different properties and dimensions” (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998, 201). This sampling approach was employed because, during the first round of interviews, a sensitizing concept—identities—emerged, which led to the theoretical sampling of respondents with different LGBTQ+ identities. All participants were screened for eligibility by the principal researcher and then given an interview appointment. All participants signed a consent form and were interviewed via Zoom.

All participants identified as LGBTQ+. They held various gender identities, including cisgender men and women, nonbinary respondents, agender respondents, and transgender women. They also held various sexualities, including bisexual, homosexual, pansexual, and asexual. An overview of their pseudonyms, sexualities, and gender identities can be found in Appendix 1. The age of respondents ranged between 18 and 70. Their nationalities also ranged widely; however, they all resided in Europe—specifically, all resided in the Netherlands or Germany at the time of the interview. Sampling respondents with various gender identities and sexual orientations allowed us to capture a broader range of experiences, while the geographical closeness ensured that all respondents were, at least at the time of the interview, exposed to similar LGBTQ+ advertising in their daily lives. The first interview guide employed by the principal investigator was formulated based on an extensive literature review. We started by conducting four semistructured interviews over the course of one week and transcribing those interviews verbatim in the following days. After finishing those transcripts, we started the coding process. We employed a reflexive approach to coding, (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) because this offers the possibility of rich, detailed, and nuanced interpretations of data. The interview guide is shown in Supplemental Online Appendix A.

Upon having conducted 12 interviews exploring the emergent concepts in greater depth, we proceeded to the second stage of axial coding. In addition to formulating the higher-order concepts, we also began constructing the relationships between the concepts. We returned once more to the data collection and conducted three more interviews, bringing us to a total of 15 interviews, which were again transcribed and coded. After conducting these 15 interviews we suspected robust and saturated findings, as no fundamentally new themes emerged after the 13th interview. This is in line with research conducted by Guest, Bunce, and Johnson (Citation2006). Still, after receiving feedback from our helpful reviewers, we agreed that some dimensions of our findings left space for further investigation. Thereafter, we conducted nine additional interviews to ensure that the data were saturated.Footnote1 We found that while these interviews offered the opportunity to expand on existing themes in more depth, they did not fundamentally challenge our interpretation of the data.

Findings

The Importance of Identity Salience

The first inductive finding of our study was the importance of the respondents’ LGBTQ+ identity, its salience, and how this influenced their advertising evaluation and SLO construction process. Respondents were asked to reflect on their LGBTQ+ identity, to what extent their LGBTQ+ identity influenced their sense of self, on their connection to the LGBTQ+ community, and on the way in which their LGBTQ+ identity determines their social role. Some respondents described their LGBTQ+ identity as having a subordinate standing in their lives, while others highlighted that they perceived their LGBTQ+ identity as their primary identity and consequently viewed life through the lens of said identity.

Low identity salience respondents experienced it as a separate isolated identity that did not influence other aspects of their lives and carried no deep connection to their personal values, as highlighted by Mark: “Honest answer is that I would prefer to be seen only as myself, not specifically as queer. I think that would be the ideal world, where I don’t have to be attached to any label, even as gay or as queer. . . . Sometimes I have to remind myself . . . that I’m among the LGBTQ+ group.” Similarly, Anna stated, “I think it’s not an extremely big part of my identity. I mean, of course I am queer, but it’s not like the first thing I tell someone if I meet them.”Footnote2

Some respondents also felt little connection to the LGBTQ+ community or did not perceive it as a community all together, as exemplified by Frantz, who stated, “I don’t think that it’s an actual community. I think it’s a demographic, right? . . . I don’t think you are in a community just because you share an identity.” Respondents with low identity salience felt that their LGBTQ+ identity did not determine their societal standing, as was outlined by Hanna, who stated, “It’s still a part of me, . . . but not in the way that it’s deviant from the norm.” Consequently, those respondents experienced less of an “othering” effect in relation to the cisgender/heterosexual majority than respondents with a high identity salience.

Respondents with high identity salience emphasized that their LGBTQ+ identity is highly intertwined with other identities they hold, as highlighted by William: “So, I feel like, honestly, queer, is kind of like my primary identity, and then everything else is kind of like filtered through that. So it’s like, yes, I am American, but I’m a queer American first.” Felix noted, “[My queer identity] . . . I think it’s quite high for me. Like it’s always up there. Right along whatever I do, like, even if I have a professional identity, this almost comes first or it’s right alongside. And it hasn’t felt good to make it come second.” When the respondents’ LGBTQ+ identity was highly salient, they often reported this identity to be somewhat intersectional, in the sense that it influenced the values they hold, as exemplified by Bengü: “It influences my core values as a person. Like I want to be very open and accepting to all people, and that is probably influenced by that identity as being queer.”

Often, these respondents reported feeling strongly connected to other people who held LGBTQ+ identities, explaining that they perceived them to have had similar experiences and consequently represent a sense of safety:

Alex: “And yeah, obviously, I feel like part of the LGBTQ+ community. I feel like it’s a safe haven. . . . It just it makes me feel safe. . . . We are basically forming a group and making borders . . . like, let’s say cis/het people, they are different than us and they don’t understand us.”

Felix: “[I feel a] very innate kinship to anyone who has a queer identity. I think I instantly just feel a relatedness to them that I don’t feel for other strangers.”

Luna: “We are considered different from other people in the society. That’s why I feel like there are two different groups, like the LGBT and the ones that . . . are, most of the time, bad to us.”

Bengü: “I feel like it is very hard to make that [my queerness] visible, even when you tell people like, I have a girlfriend, in German that’s just saying a friend, and I feel like people put a lot of effort into understanding it not the way it’s meant. So, like, even when I say partner, people would be like, ‘Is it your friend or whatever?’”

Whether due to the societally perceived differences between LGBTQ+ people and non-LGBTQ+ people, or the heteronormativity of society, respondents who experienced their LGBTQ+ identity as highly salient often felt placed in a deviant social position.

LGBTQ+ Identities and Perceptions of LGBTQ+ Advertising

All respondents reported having previously encountered LGBTQ+ advertising, with most respondents specifically highlighting having seen and experienced LGBTQ+ advertisements during Pride Month in June. Most respondents felt that LGBTQ+ advertising can help LGBTQ+ individuals feel seen, heard, and represented. They also appreciated the potential effects such as increased public awareness of LGBTQ+ issues and overall LGBTQ+ acceptance. However, respondents with a highly salient LGBTQ+ identity outlined that, despite these potential positive effects, they were critical toward companies using their identities in advertising and often attributed situational motives to those advertisements, perceiving them as rainbow-washing. As Bengü stated:

“On the one hand, I think it’s cool that some brands showed awareness to that topic, to the community, whatever. But of course, it always has a negative touch, because it’s capitalism and brands I don’t have a specific connection to, which try to get to me just by using my identity, which is kind of weird.”

Respondents with a less salient LGBTQ+ identity emphasized the beneficial aspects of LGBTQ+ advertisements more and expressed a less critical attitude toward it than respondents with highly salient identities, as exemplified by the following responses from William (whose LGBTQ+ identity was highly salient) and Mark (whose LGBTQ+ identity was of lower salience). Both respondents highlighted the importance of representation and public acceptance, but William expressed a more critical and to some extent even conflicted opinion:

William: “I still kind of see it two ways. On the one hand, yes, great, for all the young kids that need to know like . . . I very much understand the importance of representation. . . . But I’m also, like, is this actually doing anything deep? It’s like that money isn’t going to support actual, queer people ninety-nine percent of the time and it’s all just a marketing ploy for some company to get more money. It’s pure rage honestly, at this point, when I see it.”

Mark: “I think it can be a positive thing. It brings out awareness and encourages acceptance of the general public.”

Constructing Rainbow-Washing

We found that respondents made use of informational cues to inform their motivational attributions and consequently decide whether they perceived brands to be rainbow-washing. Respondents with a low identity salience were less critical toward LGBTQ+ advertising and experienced less internal conflict, leading to them be less in need of additional cues beyond the advertisements to inform their attributions. Respondents with a highly salient identity experienced more conflict and thus required a more expansive set of cues to inform their attribution. Respondents used two types of cues to determine whether a brand was rainbow-washing—namely, advertisement-centric cues and company-centric cues.

Advertisement-centric cues are cues respondents inferred from the advertisement itself, including the timing of the advertisement, geographical consistency, riskiness, reflection of the LGBTQ+ community, and product–cause fit. Company-centric cues referred to cues sourced from the organizational context in which the advertisements are situated, such as cues relating to a company’s past relationship with the LGBTQ+ community, company size, company–cause fit, profit orientation, and intersectionality of approach.

Advertisement-Centric Cues

Respondents inferred cues from the advertisements directly to inform their attribution making. The first recurringly mentioned cue was the extent to which advertisements reflected and showed a real understanding of the LGBTQ+ community. Intrinsic motives were attributed to advertisements that spotlighted the more overlooked members of the community, or which reflected a deeper understanding of the struggles that LGBTQ+ people face. In contrast, advertisements that showcased more superficial support for the LGBTQ+ community were often attributed situational motives.

To that end, Antonio highlighted that “their ads could target specific LGBTQ+ issues, like youth homelessness. I think there’s a lot of ways that companies can use messaging to better help the community and show their genuine support.” Similarly, Theo stated:

“I would also feel better if they donate to a cause that is, I guess, more specific. Like, . . . we want to prevent anti-LGBT violence, or more LGBT education in school, or better prevention against homophobia or STDs [sexually transmitted diseases]. A specific thing they can help the community with, rather than just being like okay, there’s a charity we can donate some things to.”

“There is the trans month, the trans awareness week, the transgender day of remembrance, the transgender day of visibility, and I never see anything during those moments. Sounds a little bit like lesbian and gay pride, like LG. And the B, the Q, the T, the A, just—they do not exist, so I . . . feel a bit angry.”

Thus, companies whose LGBTQ+ advertisements showed only a minimal understanding of the LGBTQ+ community were more likely to be attributed situational motives than companies who invested in demonstrating a deep understanding of the entire LGBTQ+ community and the struggles this community faces.

Brands were also evaluated on whether they took a risk with their LGBTQ+ advertisements. Brands who were visibly taking a risk with their advertisements were often attributed intrinsic motives and consequently less likely to be perceived as rainbow-washing than companies who were making LGBTQ+ advertisements risk-aversely. Julia noted, “When companies take more risk, I will also see it as more genuine. When they know that some of their customer base will oppose to it, and they still choose to go ahead and do it, regardless of boycotting and things like that, I would see it as more genuine.” Other respondents criticized companies who made LGBTQ+ advertising in countries that are generally supportive of the LGBTQ+ community but refrained from doing so in less supportive countries. This form of risk aversion in LGBTQ+ advertising was often seen as a sign of rainbow-washing. As Valente stated, “And the interesting thing is that they [a corporation from Italy] also had a boat during Pride [in Amsterdam], and I found it so . . . like a bit fake, because I think in Italy, they would not take the same stance. I do not really think it always comes from a good place.” Thus, brands explicitly taking risks to show their support for the LGBTQ+ community were more likely to be perceived as intrinsically motivated than companies who only made LGBTQ+ advertisements when it was seen as risk free, which was interpreted as situationally motivated.

The most prevalent advertisement-centric cue was the timing of advertisements. Respondents outlined that they experienced LGBTQ+ advertising primarily, if not exclusively, during Pride Month. They perceived brands to express public support for the LGBTQ+ community only during Pride, as opposed to all year round, making respondents critical of the advertisements. Brands that limited their public expressions of LGBTQ+ support to one month in the year were attributed situational motives (such as purely wanting to increase profit). Respondents concluded that suspicious timing is a sign of insincerity, indicating that the corporations did not care about the LGBTQ+ community but wanted to capitalize on the yearly occasion of Pride, and hence perceived them to be rainbow-washing. Brands which made LGBTQ+ advertising all year round, however, were much more likely to be attributed intrinsic motives and thus not be considered rainbow-washing. As Luna stated,

“When there’s Pride Month, a lot of companies start producing stuff for Pride only, while the rest of the year they really don’t care about that. You know, they’re just making it to make money or—so that’s why I really don’t like it. Because they don’t actually care about us; they’re only doing it for themselves.”

Company-Centric Cues

Respondents also collected cues from the organizational environment in which the advertisements are situated. For instance, many respondents highlighted that company size impacted their evaluation of the advertisement. They were much more likely to attribute rainbow-washing to large corporations than small, independently run businesses, as Mic stated: “Well, it depends. If they are a big company or like a little company, because I have different emotions for big companies and small ones. I think that capitalism is one of the reasons why queer people are oppressed, so I don’t appreciate that.” Similar sentiments were expressed by William, Julia, and Eni. William noted, “If it’s a smaller company that’s like maybe not inherently queer but like trying with their marketing, I’m a little bit more forgiving.” Julia stated, “Most of it . . . I don’t feel like it’s genuine, because it never is . . . if it’s like a very big company.” Eni explained, “Probably there’s a bunch of big companies who don’t have a really good human rights track record and it makes me wary of how genuine their support of LGBTQ+ rights is.”

The aspect concerning human rights raised by Eni ties into another cue often reported by respondents. Many respondents voiced that whether they perceived corporations’ support of the LGBTQ+ community to be intersectional influenced their evaluation of the corporations LGBTQ+ advertising campaign. They elaborated that if they perceived brands to support other social causes such as sustainability and fair treatment of workers, they were more inclined to perceive LGBTQ+ ads as intrinsically motivated. For instance, William stated, “If the company is actively lobbying governments to divest from fossil fuels, or things like that, maybe that would make it better.”

Another indicator often highlighted by respondents was the company–cause fit. Respondents found that companies who provided products or services that are inherently linked to the LGBTQ+ community were less likely to be perceived as rainbow-washing than corporations whose products or services did not have any particular meaning for the LGBTQ+ community, or even were specifically harmful to the LGBTQ+ community. Eni, for instance, brought up an example of a company making menstrual underwear: “[The company] just made a campaign where they have shorts specifically designed for trans people. . . . For me, it showcases a commitment to being an inclusive brand.”

Paul and Theo highlighted the other side of the coin; they reflected on alcohol producers making LGBTQ+ advertisements. Paul stated: “So, for example, like [alcohol brand] has a lot of money to brand to gay people because, frankly speaking, alcoholism amongst gay men is incredibly high . . . so when I look at this, I think like, what does it mean to have that company represent queer people? And what kind of message are they promoting? What does their brand specifically mean to queer people?” Theo similarly pointed out: “I think it’s kind of difficult, depending on the company. I guess with, for example, [alcohol brand] there is, you know, a larger percentage of queer people that have mental health issues and a larger percentage of queer people, you know, that struggle with substance abuse.” Hence, liquor companies have a complex relationship with the queer community, and thus if a brands’ product has a potentially negative impact on the LGBTQ+ community, respondents were more critical of their campaigns.

Respondents further stated that companies making financial profit with their LGBTQ+ advertising influenced their attributions. On the most basic level, Theo found: “[During] Pride Month they [brands] make something rainbow colored or it’s limited edition and more expensive, and those things I don’t really like.” If corporations made LGBTQ-themed products more expensive than their non-LGBTQ-themed counterparts, they were more often attributed to be situationally motivated and hence perceived to be rainbow-washing.

Moreover, the conflict respondents felt regarding corporations profiting from LGBTQ+ advertising was more profound that just attributing situational motives when the LGBTQ+ themed products were pricier than their non-LGBTQ+ counterparts. They outlined that they were conflicted because these companies are fundamentally profiting from real inequalities in society. When corporations make LGBTQ+ advertising, they often claim to promote social equality and acceptance of LGBTQ+ people. However, companies can only make these advertisements because the LGBTQ+ community is not yet socially equal. As such, they viewed brands to be using existing discrimination and inequalities in society as a source of profit. As Valente stated,

“It’s like leveraging a situation that really does not belong to you, and maybe you do not even have a full understanding of it, for the sake of making profit. But that’s really mean, because you are actually exploiting fields that are not yours. You are just exploiting some other people’s lives, experiences, that we also all know are not very positive in several cases, so that makes me feel a bit like [sighs uncomfortably].”

However, some respondents mentioned that if brands donated a substantial part of the profit to LGBTQ+ causes, they were less likely attribute situational motives. Mic explained that he “saw that they made the advertisement, and after that they said, they are not only doing this advertisement, but they also started a project for this organization, and that is a positive sign for me . . . because at that point it’s not only making profit but also giving money.” Similarly, Anna argued, “I do think it’s very important that if you, as a company, decide to make like a Pride collection, or something like that, I feel like you have to donate something at least. Because, if you’re not, then it’s really just marketing and just trying to make more profit for yourself.”

The most frequently brought up cue referred to the company’s past with the LGBTQ+ community. Most respondents outlined that if corporations had a negative past with the LGBTQ+ community—in the sense that they either mistreated LGBTQ+ people or supported those actively harmful to the LGBTQ+ community—then the advertisements were likely seen as situationally motivated. Willow noted, “There are organizations that promote by using the flag, but the history of their treatment of LGBT people isn’t good, so if they’re not doing it in their employment or with their employees, and they just want people to go in and buy things. . . . I’m very suspicious of what this is about.” Similarly, Julia explained, “If it’s a brand that has been harmful to LGBTQ people in the past, I can see that [boycotts] happen.” Gabriel expressed a similar sentiment: “If like, for example, [fast-food brand], which has a history of you know [referring to a history of corporate donations to anti-LGBTQ+ organizations and anti-LGBTQ+ statements] started like doing rainbow cups or whatever, and they still donated to the organizations that they donate to, obviously, I’d be like, this doesn’t make sense, and I don’t want to support that.” In addition, it was mentioned that if corporations had a history of LGBTQ+ discrimination, these companies must reflect upon and atone for said history before engaging in LGBTQ+ advertising. If corporations chose to ignore their inequitable history and made LGBTQ+ advertising without addressing their past, they were perceived to be rainbow-washing. For example, Felix explained:

“I think [a specific company] had a little thirty-minute video, saying like “We support the queer people who work here. These are the resources we have for them.” And Twitter blew up because of [company’s] past during World War Two in Nazi Germany, making some of the early computational devices that they used to run to administrate the concentration camps, where of course there were queer people who were interned there.”

Identity Salience, Perceptions of Rainbow-Washing, and How They Influence SLO Construction

Some respondents, specifically respondents with a low identity salience, did not initially voice disapproval of LGBTQ+ advertising, even if they perceived it to be rainbow-washing. Freddie, for example, explained that they were always in favor of LGBTQ+ advertising because “it helps with visibility and the more of it there is, the more like normalized it is.” However, for most respondents, attributing situational motives to advertisements had twofold effects. On one hand, most respondents stated that they could still see the beneficial societal effects (such as increased visibility and acceptance) of LGBTQ+ advertising, even if they clearly perceived it to be rainbow-washing. As Felix said, “Maybe it’s not ethical, and maybe they’re just doing it to get money, but it is better than the alternative, which is to completely ignore us and not do anything.”

On the other hand, this did not inherently imply approval of the corporation’s activities. Despite the understanding that it might have beneficial effects, brands were still at risk of losing their approval. Respondents, especially those with highly salient identities, highlighted that if they found severe discrepancies between “talk” and “walk”—such as a corporation having been actively harmful to the LGBTQ+ community—then they were likely to lose their approval, as outlined by Osas: “If I knew for a fact that there’s this company, and that they have values that don’t align with the LGBTQ+ community, or they’re harmful to the LGBTQ+ community, but they are putting out, I don’t know, great fashion ads that signal to the LGBTQ+ community, then I would, for a fact, not buy it. I would definitely boycott it.”

Further, they often stated that they shared their opinions concerning advertisements which they perceived to be rainbow-washing with their social environments—both inside and outside their community. To that end, Quirin explained:

“Personally, I won’t interact with this brand [brand he perceives to be rainbow-washing] at all, because I don’t want to support them in any way. Like I will go out of my way to refrain from buying from them or using the things that they offer, . . . and I think I actually share it with my friends that are also queer. We just sometimes encounter them [rainbow-washing advertisements] when we are walking around the city, and of course we are all aware of rainbow-washing, so we all agree that it’s something that people should know about, and how problematic it is.”

“For example, I also talked about it with my mom, who’s not part of the community, [and] I do tell her that’s, like, just rainbow-washing. They do not care about the queer community, and she did ask me, “Okay, but like, why is it bad?” Or something? I just told her like basically the same thing that I just told you. I just wanted her to know what was up, and that she does also know, okay, maybe let’s not support these brands.”

Quirin outlines that perceived rainbow-washing led him not only to engage with other members of his community to discuss their disapproval but also to inform those outside of the community that the brand had lost their approval. Hence, while it was especially LGBTQ+ individuals with highly salient identities whose perception of rainbow-washing led to them disapprove of the corporation’s activities, they made an effort to spread their disapproval within their community and beyond it, thereby actively engaging in the withdrawal of SLO.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to understand when vested stakeholders (in our case, LGBTQ+ consumers) attribute situational motives to LGBTQ+ advertising, when it was perceived to be rainbow-washing, and when this led to a withdrawal of corporate SLO by these vested stakeholders. Our core findings are summarized in .

Figure 2. Process of constructing rainbow-washing and its influence on the corporate social license to operate (SLO).

We found that the respondent’s minority identity salience expands the cues used by them to evaluate the identity-targeting advertisements. Specifically, respondents with highly salient minority identities looked beyond the advertisements to determine whether brands are rainbow-washing. The respondents examined the company-specific context of the advertisements for consistency: If the messages sent by the brand through their advertisements were inconsistent with their previous communication and behavior, then they attributed situational motives to their advertising and the brand was perceived to be rainbow-washing. The extent to which perceptions of washing led to the respondents engaging in SLO withdrawal was also influenced by their identity salience. Especially respondents with highly salient identities actively participated in SLO withdrawal, but in doing so they engaged others (both within and beyond their community) in this process.

This study illuminates the process minority consumers engage in, from encountering identity-targeting advertisements, to evaluating them and forming attributions, on the basis of which they construct the brands’ SLO. While our findings are explicitly situated in the field of advertising, they support the broader notion that minority consumers evaluate the brand in its entirety, as opposed to considering identity-targeting advertisements in a vacuum (Lim, Ciszek, and Moon Citation2022). We demonstrate that an evaluation of the brands’ advertisements can lead to perceptions of rainbow-washing if the overall brand communications and conduct are found to be inconsistent with the messages communicated in their advertisements. Moreover, we provide insight on how SLO withdrawal by a targeted community might occur as a consequence of perceived rainbow-washing.

Our findings relate to previous SLO research, which has tied SLOs to other theories (such as stakeholder theory; Gupta and Kumar Citation2018) to explain the process through which SLOs are constructed. While many of these studies focused on the ways in which companies can manage stakeholder relations (Hall and Jeanneret Citation2015; Provasnek, Sentic, and Schmid Citation2017; Sáenz Citation2018) to be granted a SLO, our study emphasizes the perspective of the vested stakeholder community through the integration of SCT and attribution theory into the SLO framework. Moreover, most studies consider SLOs as an outcome of public relations conducted in a local context (Ihlen and Raknes Citation2020), whereas our study expands the scope by outlining how advertising can influence the SLO granted by a dispersed community within an issue arena (Luoma-Aho and Vos Citation2010; Vos, Schoemaker, and Luoma-Aho Citation2014).

Moreover, our findings connect to broader discussions on identity-targeting advertising (e.g., femvertising; Sobande Citation2019), which have previously outlined that as brands try to signal empowerment through the commercialization of advocacy, they can perpetuate the very inequalities they are trying to address. We offer insight into the perspectives of the targeted minority communities, as they evaluate advertisements making use of their symbols and language to communicate brand inclusivity. Specifically, we highlight that to have positive effects on the targeted minority community, brands’ advertisements must be situated within a broader brand culture of inclusivity.

Contributions

Theoretical Contributions

With our findings, we make four contributions to advertising literature. First, we contribute to the literature on inclusive advertising by crystallizing the effect of minority identities on advertising evaluations. Second, we contribute to inclusive advertising literature by outlining which cues minority consumers employ to construct motivational attributions to inform their washing evaluations. Our third contribution lies in introducing the SLO framework to advertising literature and theoretically extending it to capture the outcomes of advertising evaluations by vested consumers. Integrating attribution theory and SLOs allows us to better account for the SLO construction process from the perspective of the vested stakeholder group. By applying this framework to identity-targeting advertisements, we provide a comprehensive analytical tool for understanding the processes of minority consumers when exposed to identity-targeting advertisements. Fourth, we contribute to the literature on corporate washing in advertising by demonstrating when washing perceptions can lead to a loss of approval by the targeted community.

Previous research on the impact of identity salience for advertising evaluations has argued that consumers evaluate ads and brands more favorably when they connect to a highly salient identity (Navarro et al. Citation2019; Shao et al. Citation2023). The findings of this study advance those insights, as we found that a highly salient identity can also lead to increased skepticism by the targeted consumer. We outline that, in instances where advertisements make use of minority identity symbols and imagery, group members with a highly salient minority identity might react more critically and express more skepticism toward the advertisement, leading them to collect additional cues to inform their judgments. As such, we give first insights on the circumstances under which a highly salient minority identity leads not to a more favorable evaluation of minority-targeting ads and brands, but can lead to a more negative evaluation through the attribution of situational motives. These findings also support and expand insights from existing research on other forms of corporate washing, such as greenwashing (Paço and Reis Citation2012), which found that increased concern for the environment leads to more skepticism toward green advertising.

We contribute to inclusive advertising literature focused on corporate washing (see Matthes Citation2019; Schmuck, Matthes, and Naderer Citation2018) because we outline which cues LGBTQ+ consumers used to evaluate LGBTQ+ advertising and determine whether they perceive a brand to be rainbow-washing. Here, we demonstrated that consumers sourced cues from the advertisement itself as well as inferred cues from the organizational context. In doing so, we not only shed light on the cues which LGBTQ+ respondents used to inform their attributions but also outlined the interconnectedness of advertising and its broader organizational context, which is of the utmost importance for this area of research. In summary, we have outlined that perceived inconsistencies between the previous organizational conduct and the advertisement can lead to the attribution of washing by the vested stakeholder community.

We contribute to literature on the outcomes of perceived corporate washing (see Matthes Citation2019) by demonstrating when perceived rainbow-washing in advertising can lead to a withdrawal of SLO by the vested stakeholders in a particular issue arena. Previous research has illustrated that there are discrepancies between the perceptions and evaluations of vested and nonvested stakeholders (Li Citation2021), which emphasizes the need to explore the outcomes of their perceptions of corporate washing separately. Focusing on the SLO allowed us to isolate attitudinal outcomes of perceived rainbow-washing on the level of the vested stakeholder group. Further, applying the SLO concept in this study shed first light on processes inherent to SLO construction in a context in which the vested stakeholders are not bound together geographically but connected through membership in a social group whose symbols and imagery were used in advertising. This widens our understanding of how SLOs are constructed beyond the local context.

We argue that vested stakeholders with a highly salient identity actively expressed disapproval, shared their sentiment with other community members and involved them in demonstrations of dissatisfaction to create collective awareness of the loss of the SLO of their community. Hence, we found that in instances where the community is not bound together geographically, the SLO withdrawal process begins with community members with highly salient identities expressing their own disapproval, and consequently actively diffusing their opinion within their community, and even beyond it. The engagement beyond their own community highlights that these vested stakeholders withdrawing their SLO likely starts the broader backlash that many brands have begun to face for their LGBTQ+ advertisements.

Finally, we contribute to the advertising literature by theoretically extending the SLO framework and applying it to the advertising context. We have engaged in theory development within the SLO framework as we integrated attribution theory into the SLO framework and considered it in tandem with SCT to explain the SLO construction process. We illustrate that attributions are integral to the process of SLO construction, and it is therefore highly beneficial to consider attribution theory within the SLO framework. Moreover, we highlight that, in instances of identity-targeting advertisements, it is useful to consider SCT and this SLO framework in tandem, because the extent to which individuals think and behave in line with their social group influences both their attribution making and how these attributions determine the brands’ SLO. We thus propose a theoretical model that integrates attribution theory into the SLO framework and connects it to SCT, which offers a useful tool in the analysis of the minority consumer process when faced with identity-targeting advertisements.

Managerial Implications

In addition to these theoretical contributions, the study also has distinct practical implications. First, it gives organizations indications on how to make minority-targeting advertising to avoid backlash from the vested community. Advertisements that illustrate a deeper level of understanding of the targeted community and their members indicated more intrinsic motivations, whereas superficial advertisements often indicated situational motives. Similarly, brands should aim to be consistent beyond their advertisements, as brand consistency indicated dispositional motives. Further, practitioners should aim to win over those members of the community whose social identity is of high salience, because they are the most critical and the most vocal in their opposition if they perceive brands to be washing.

Aside from offering brands a guideline on how to engage in LGBTQ+ advertising to avoid rainbow-washing accusations and maintain their SLO, this study also recenters the vested stakeholders and affirms their powerful position in determining the fate of companies’ SLO within their issue arena. Brands can have multiple reasons to make LGBTQ+ advertising, from demonstrating inclusivity (Wilkie et al. Citation2023) to attracting the queer dollar (Ginder and Byun Citation2015), and more often than not only a small portion of consumers examine their advertisements critically and question their motivations (Wilkie et al. Citation2023). However, even this small consumer subsection—the vested stakeholders with highly salient identities—can play a powerful role in constructing (and of course denying) a brand’s SLO if they perceive the brand to be rainbow-washing. Specifically, we highlight that these are the consumers most vocal in their judgments, and brands could benefit from orienting their minority advertisements toward this particular consumer segment.

Consequently, brands should increase their engagement with these vested stakeholders in two ways. On one hand, brands should engage with vested stakeholders prior to making their advertisements to gain a deeper understanding of the needs and wants of the community they are targeting. Achieving authenticity by portraying the communities’ values, concerns, and experiences is crucial to demonstrate intrinsic motivations, allowing brands to significantly lower the risk of being perceived as washing. Moreover, brands should proactively monitor the public reactions of vested stakeholders (for example, on social media) to be able to anticipate backlash early and prevent broader boycotts, as recognition of their disapproval is a key indicator of potential backlash.

Finally, brands must recognize that consumers do not perceive and evaluate their advertisements in a vacuum. Rather, they seek consistency across communication platforms, in brands’ internal policies and behavior, as well as across issue arenas. To be perceived as truly inclusive, brands must thus invest substantial resources in to intersectional inclusivity. If brands practice inclusivity only in their advertising and not in their other forms of engagement, or if brands are inclusive only toward minority groups constituting profitable consumer segments, they run the risk of being perceived as washing and consequently being held accountable for it. These practical implications, as well as suggestions for future research are summarized in a table in Appendix 2.

Future Research Directions

We encourage future research on perceptions of washing in identity-targeting advertising to apply the theoretical framework proposed here, for example, to investigate more closely the processes of SLO withdrawal by the vested community as a consequence of perceived washing. While we have shed light on how vested stakeholders with high identity salience engage in building a shared understanding of the brands’ SLO and its potential withdrawal, still more is to be learned about these processes—especially for spatially dispersed (minority) communities.

As this is a qualitative, inductive study, it is important for future research to examine the processes described in other settings. For example, the findings of this work do not indicate how perceived washing (and consequently the SLO) is constructed in settings where advertisements are not inherently connected to consumer identities. In addition, the topics investigated in this study are thematically linked to other relevant streams of research, such as the growing body of research addressing political consumption. While addressing political consumption extended beyond the scope of this study, it is of relevance to washing research, and to the field of inclusive advertising. Thereafter, future research might benefit from linking studies on corporate washing and SLO construction to other relevant phenomena such as political consumption and situate it within the growing body of research on inclusive advertising.

Conclusion

This study contributes to theory on how LGBTQ+ consumers construct the rainbow-washing attribution in reference to LGBTQ+ advertising. More broadly speaking, this article begins to unravel the potential effects of corporations entering sociopolitical issue arenas through advertising. We emphasize that practitioners should critically examine their LGBTQ+ advertising. Practically, this means that corporations should expand their LGBTQ+ advertising beyond the annual Pride celebrations in June and especially emphasize their LGBTQ+ advertising in contexts in which LGBTQ+ rights and equality are at risk, if they want to be perceived as intrinsically motivated. This requires corporations to engage with the LGBTQ+ community beyond bending to social pressures (Van Der Meer and Jonkman Citation2021) and advertising to the queer dollar (Ginder and Byun Citation2015). Academically, we invite scholars to investigate the various issue arenas that corporations enter through advertising to understand the impact that these advertisements have—both for the targeted community and for the brands making those advertisements.

Supplemental Online Appendix B

Download MS Word (42.5 KB)Supplemental Online Appendix A

Download MS Word (40.8 KB)Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to the associate editor and the reviewers for their valuable feedback and guidance on this article. Their expertise has significantly improved the work, and we appreciate their efforts and constructive suggestions. We also extend our thanks to the LGBTQ+ organizations that provided invaluable assistance in recruiting respondents for our study. Finally, our heartfelt thanks go out to all our respondents for sharing their insights and experiences with us.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflicts of interest were reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tiziana Schopper

Tiziana Schopper (MSc, University of Amsterdam) is a doctoral candidate, Institute for Leadership and Organization, Munich School of Management, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München.

Anna Berbers

Anna Berbers (PhD, KU Leuven) is an assistant professor, Amsterdam School of Communication Research, University of Amsterdam.

Lukas Vogelgsang

Lukas Vogelgsang (PhD, FU Berlin) is an assistant professor, Institute for Leadership and Organization, Munich School of Management, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München.

Notes

1 In the conduct of the research presented in this article, we complied with the APA Ethical Principles regarding research with human participants, as well as the principles for ethical research stated in the Belmont Report. The first wave of interviews was conducted while the lead author was affiliated with the University of Amsterdam, and approval was received on November 22nd, 2021, in line with the guidelines of the Amsterdam School of Communication Research for such research projects. The second wave of interviews (which occurred during the revision process) was conducted while the lead author was affiliated with the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität (LMU) Munich. At the time of this study, the LMU Munich School of Management did not require ethical approval for noninvasive, interview-based research, nor did it have an ethics board to review and approve studies.

2 Empirical quotes are also listed and categorized in a table in Supplemental Online Appendix B.

References

- Abrams, D., & M. A. Hogg, 2010. “Social Identity and Self-Categorization.” In The SAGE Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping and Discrimination, edited by J. F. Dovidio, M. Hewstone, P. Glick, and V. M. Esses, 179–193. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446200919.n11

- Baron, K. 2022, April 11. Prepping For Pride 2022 & Beyond: Engaging a Booming LGBTQ+ Consumer Landscape. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/katiebaron/2022/04/11/prepping-for-pride-2022–beyond-engaging-a-booming-lgbtq-consumer-landscape/?sh=49cd36077faf

- Batey, M. 2019, July 8. “Selling the Rainbow: Why Rainbow-Washing Is Actually Bad Marketing.” Public Discourse. https://www.thepublicdiscourse.com/2019/07/54444/

- Boutilier, R. G., and I. Thomson. 2011. “Modelling and Measuring the Social License to Operate: Fruits of a Dialogue between Theory and Practice.” Social Licence 1–10.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Browne, K., and C. J. Nash. 2010. Queer Methods and Methodologies: Intersecting Queer Theories and Social Science Research. London: Routledge.

- Champlin, S., and M. Li. 2020. “Communicating Support in Pride Collection Advertising: The Impact of Gender Expression and Contribution Amount.” International Journal of Strategic Communication 14 (3): 160–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2020.1750017

- Ciszek, E., and H. Lim. 2021. “Perceived Brand Authenticity and LGBTQ Publics: How LGBTQ Practitioners Understand Authenticity.” International Journal of Strategic Communication 15 (5): 395–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2021.1988954

- Demunter, R., and J. Bauwens. 2023. “Going All the Way? LGBTQ People’s Receptiveness to Gay-Themed Advertising in a Belgian Context.” European Journal of Marketing 57 (4): 1219–1241. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-11-2020-0847

- Eisend, M., and E. Hermann. 2019. “Consumer Responses to Homosexual Imagery in Advertising: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Advertising 48 (4): 380–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2019.1628676

- Ellemers, N., and S. A. Haslam. 2012. “Social Identity Theory.” Vol. 2 of Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology, 379–398. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446249222.n45

- Gehman, J., L. Lefsrud, and S. Fast. 2017. “Social License to Operate: Legitimacy by Another Name?” Canadian Public Administration 60 (2): 293–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/capa.12218

- Ginder, W., and S. Byun. 2015. “Past, Present, and Future of Gay and Lesbian Consumer Research: Critical Review of the Quest for the Queer Dollar.” Psychology & Marketing 32 (8): 821–841. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20821

- Ginder, W., W. Kwon, and S. Byun. 2021. “Effects of Internal–External Congruence-Based CSR Positioning: An Attribution Theory Approach.” Journal of Business Ethics 169 (2): 355–369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04282-w

- Guest, G., A. Bunce, and L. Johnson. 2006. “How Many Interviews Are Enough?” Field Methods 18 (1): 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903

- Gunningham, N., R. A. Kagan, and D. Thornton. 2004. “Social License and Environmental Protection: Why Businesses Go beyond Compliance.” Law & Social Inquiry 29 (2): 307–341. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-4469.2004.tb00338.x

- Gupta, S., and A. Kumar. 2018. “Social Licence to Operate: A Review of Literature and a Future Research Agenda.” Social Business 8 (2): 187–203. https://doi.org/10.1362/204440818X15333820366450

- Hall, N., and T. Jeanneret. 2015. “Social Licence to Operate.” Corporate Communications: An International Journal 20 (2): 213–227. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-01-2014-0005

- Hurst, B., K. A. Johnston, and A. B. Lane. 2020. “Engaging for a Social Licence to Operate (SLO).” Public Relations Review 46 (4): 101931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2020.101931

- Ihlen, Ø., and K. Raknes. 2020. “Appeals to ‘the Public Interest’: How Public Relations and Lobbying Create a Social License to Operate.” Public Relations Review 46 (5): 101976. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2020.101976

- Jeong, S. 2009. “Public’s Responses to an Oil Spill Accident: A Test of the Attribution Theory and Situational Crisis Communication Theory.” Public Relations Review 35 (3): 307–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2009.03.010

- Lau, H. Y., and R. T. Lee. 2018. “Ethnic Media Advertising Effectiveness, Influences and Implications.” Australasian Marketing Journal 26 (3): 216–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2018.05.014

- Li, M. 2021. “Influence for Social Good: Exploring the Roles of Influencer Identity and Comment Section in Instagram-Based LGBTQ-Centric Corporate Social Responsibility Advertising.” International Journal of Advertising 41 (3): 462–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2021.1884399

- Lim, H. S., E. Ciszek, and W. Moon. 2022. “Perceived Organizational Authenticity in LGBTQ Communication: The Scale Development and Initial Empirical Findings.” Journal of Communication Management 26 (2): 187–206. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-02-2021-0023

- Luoma-Aho, V., and M. Vos. 2010. “Towards a More Dynamic Stakeholder Model: Acknowledging Multiple Issue Arenas.” Corporate Communications: An International Journal 15 (3): 315–331. https://doi.org/10.1108/13563281011068159

- Marschlich, S. 2022. “Corporate Diplomacy: How Multinational Corporations Gain Organizational Legitimacy.” In Organisationskommunikation, XVIII, 212. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-36818-0

- Matthes, J. 2019. “Uncharted Territory in Research on Environmental Advertising: Toward an Organizing Framework.” Journal of Advertising 48 (1): 91–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2019.1579687

- Mattley, C., A. Strauss, and J. Corbin. 1997. “Grounded Theory in Practice.” Contemporary Sociology 28 (4): 489. https://doi.org/10.2307/2655359

- Milfeld, T., D. J. Flint, and A. R. Zablah. 2022. “Riding the Wave: How and When Public Issue Salience Impacts Corporate Social Responsibility Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 53 (1): 148–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2022.2146023

- Navarro, M. A., L. Hoffman, E. Crankshaw, J. Guillory, and S. E. Jacobs. 2019. “LGBT Identity and Its Influence on Perceived Effectiveness of Advertisements from a LGBT Tobacco Public Education Campaign.” Journal of Health Communication 24 (5): 469–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2019.1615582

- Nelsen, J. L. N. S. 2006. “Social License to Operate.” International Journal of Mining, Reclamation and Environment 20 (3): 161–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/17480930600804182

- Nyilasy, G., H. Gangadharbatla, and A. Paladino. 2012. “Greenwashing: A Consumer Perspective.” Economics & Sociology 5 (2): 116. https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1P3-2862726661/greenwashing-a-consumer-perspective.

- Paço, A. D., and R. Reis. 2012. “Factors Affecting Skepticism toward Green Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 41 (4): 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2012.10672463

- Parsons, R., J. Lacey, and K. Moffat. 2014. “Maintaining Legitimacy of a Contested Practice: How the Minerals Industry Understands Its ‘Social Licence to Operate.” Resources Policy 41:83–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2014.04.002

- Pinto, C. L., N. Huete-Alcocer, L. E. C. Rivera, and R. T. Veiga. 2020. “Diversity and Consumption: Evaluation of the Research Papers on the LGBT Community in Top Marketing Journals.” Atlantic Marketing Journal 9 (1): 5. https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/amj/vol9/iss1/5/.

- Pope, S., and A. Wæraas. 2016. “CSR-Washing Is Rare: A Conceptual Framework, Literature Review, and Critique.” Journal of Business Ethics 137 (1): 173–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2546-z

- Prno, J., and D. S. Slocombe. 2012. “Exploring the Origins of ‘Social License to Operate’ in the Mining Sector: Perspectives from Governance and Sustainability Theories.” Resources Policy 37 (3): 346–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2012.04.002

- Provasnek, A. K., A. Sentic, and E. Schmid. 2017. “Integrating Eco-Innovations and Stakeholder Engagement for Sustainable Development and a Social License to Operate.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 24 (3): 173–185. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1406

- Ruiz-Blanco, S., S. Romero, and B. Fernandez-Feijoo. 2021. “Green, Blue or Black, but Washing–What Company Characteristics Determine Greenwashing?” Environment, Development and Sustainability 24 (3): 4024–4045. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01602-x

- Sáenz, C. 2018. “Building Legitimacy and Trust between a Mining Company and a Community to Earn Social License to Operate: A Peruvian Case Study.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 26 (2): 296–306. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1679

- Schmuck, D., J. Matthes, and B. Naderer. 2018. “Misleading Consumers with Green Advertising? An Affect–Reason–Involvement Account of Greenwashing Effects in Environmental Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 47 (2): 127–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2018.1452652

- Shao, W., Y. Zhang, A. Cheng, S. Quach, and P. Thaichon. 2023. “Ethnicity in Advertising and Millennials: The Role of Social Identity and Social Distinctiveness.” International Journal of Advertising 42 (8): 1377–1418. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2023.2172663

- Sobande, F. 2019. “Woke-Washing: “Intersectional” Femvertising and Branding “Woke” Bravery.” European Journal of Marketing 54 (11): 2723–2745. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-02-2019-0134

- Strauss, A., and J. Corbin. 1998. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Tajfel, H. 1974. “Social Identity and Intergroup Behaviour.” Social Science Information 13 (2): 65–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901847401300204

- Taylor, C. 2022. “Future Needs in Gender and LGBT Advertising Portrayals.” International Journal of Advertising 41 (6): 971–973. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2022.2095941

- Tie, Y. C., M. Birks, and K. Francis. 2019. “Grounded Theory Research: A Design Framework for Novice Researchers.” SAGE Open Medicine 7: 2050312118822927. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312118822927

- Turner, J., and K. J. Reynolds. 2012. “Self-Categorization Theory.” Vol. 2 of Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology, 399–417. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446249222.n46

- Van Der Meer, T. G., and J. G. F. Jonkman. 2021. “Politicization of Corporations and Their Environment: Corporations’ Social License to Operate in a Polarized and Mediatized Society.” Public Relations Review 47 (1): 101988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2020.101988

- Viglia, G., W. S. Tsai, G. Das, and I. Pentina. 2023. “Inclusive Advertising for a Better World.” Journal of Advertising 52 (5): 643–646. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2023.2255242

- Vos, M., H. Schoemaker, and V. Luoma-Aho. 2014. “Setting the Agenda for Research on Issue Arenas.” Corporate Communications: An International Journal 19 (2): 200–215. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-08-2012-0055