ABSTRACT

Originally conceived to create dense, diverse and mixed-used communities that are inclusive and sustainable communities, Transit-oriented Development (“TOD”) has come under increasing academic scrutiny on its negative implications on equity and justice. However, these injustices are often examined case-by-case individually, which revealed the lack of a comprehensive framework that is grounded in justice concepts and theories for analysing justice in TOD. In this paper, we aim to show the importance of, and suggest a framework for, analysing justice in TOD holistically. We begin by taking a brief overview of key theories and concepts in process and outcome justice. Then, through a thematic review of justice-related TOD literature, we synthesised three main justice issues currently existing in TOD: transit-induced gentrification; neglect of livelihood and well-being of disadvantaged groups; and poor inclusion and representation of different stakeholders. These issues revealed the interconnectedness and importance of both process and outcome justices in TOD. As such, we formulated an analytical framework by adopting the Institutional Analysis and Development (“IAD”) model (a tool for understanding institutional interactions in public policies) to examine process justice; and the 5Ds of the built environment (namely Density, Diversity, Design, Destination Accessibility, and Distance to Transit) to examine outcome justice. In brief, for process justice, our framework advocates open, accessible and equitable particiaption by all interested stakeholders to be able to give views, exercise their power, obtain and share information, and make decisions collectively, with dedicated efforts to facilitate participation of more disadvantaged groups. For outcome justice, our framework calls for providing suitable and equitable built environments (in terms of 5Ds) in different neighbourhoods in a TOD, with special attention towards the needs of disadvantaged groups. The framework serves as general guidance for researchers and planners to analyse the justice implications of TOD (both ex-ante and ex-post) in a holistic and conceptually-grounded manner, with a view to better positioning justice issues and directing efforts towards more just TODs.

1. Introduction

Transit-Oriented Development (“TOD”) advocates mixed-use, high-density, walkable and compact neighbourhoods centred around transit stations, aiming to build equitable and sustainable communities (Calthorpe, Citation1993). While TOD promises benefits from increasing development density and diversity, to encouraging walking/cycling, transit use and curbing urban sprawl (Hrelja et al., Citation2020; Ibrahim et al., Citation2022; Jamme et al., Citation2019), its justice implications have also received greater recognition and interest recently (Ibrahim et al., Citation2022; Padeiro et al., Citation2019; Shatu et al., Citation2022), with sustainability, equity, and gentrification among the main emergent research themes (Sun et al., Citation2022). Literature has uncovered various justice issues associated with TOD, including gentrification (Baker & Lee, Citation2019; Cervero, Citation2004; Deka, Citation2016); loss of affordable housing (Peng & Knaap, Citation2023; Zhu & Diao, Citation2022); poor institutional coordination (Banerjee et al., Citation2018; Pojani & Stead, Citation2014); unclear and inadequate engagement of stakeholders (Harrison et al., Citation2019; Mohiuddin, Citation2021; Noland et al., Citation2017); challenges faced by ethnic minorities (Lung-Amam et al., Citation2019; Zuñiga & Houston, Citation2022), older adults (Chen et al., Citation2023), and families with children (Bierbaum & Vincent, Citation2013).

Despite the variety and significance of issues identified, a comprehensive and conceptually-grounded framework to analyse and position justice issues within TOD is lacking. Jamme et al. (Citation2019) noted in their review of TOD literature that today’s narrower, more specific analysis of TOD issues had drawn research focus away from TOD’s comprehensive goal of affordable, liveable and equitable communities. This concurs with the observation that spatial planning research tends to explicate how injustices happen “on the ground”, i.e. real-life phenomenon that appear unjust, but less drawing from justice theories and concepts to support their analysis with a normative theoretical framework (Israel & Frenkel, Citation2018; Przybylinski, Citation2022). More specifically, research commonly approaches justice in TOD through equitable outcomes and fair distribution (Ibraeva et al., Citation2020; Lung-Amam et al., Citation2019), while less so through the planning and procedural side of TOD, e.g. interactions and inclusion of stakeholders (Hrelja et al., Citation2020; Ibraeva et al., Citation2020).

Therefore, in this review-based conceptual paper, we aim to formulate a comprehensive and conceptually-grounded analytical framework to analyse justice in TOD, including both process and outcome aspects of justice. The framework aims to provide general guidance to systematically position and analyse various injustice issues in TOD (whether ex-ante or ex-post), in order to better learn from and compare cases, direct attention and resources, and formulate measures towards more just TODs.

The paper is structured as follows. Starting with Section 2, we elaborate briefly on concepts of justice to lay the normative foundations for the meaning of the term. Then, in Section 3, we describe the methodology of our thematic review, followed by Section 4 discussing our review findings - three key justice issues in TOD reflecting and relating to both process and outcome justice. In Section 5, we formulate an analytical framework of justice in TOD, adopting the Institutional Analysis and Development (“IAD”) model developed by Polski and Ostrom (Citation1999), a tool intended for understanding institutional interactions in forming policies, to analyse process justice; and 5Ds of the built environment (i.e. Density, Diversity, Design, Destination Accessibility, and Distance to Transit), which originates as criteria to determine a TOD’s success, to analyse outcome justice. To conclude, we discuss the framework’s operationalisation, significance and limitations.

2. Background – concepts of justice

In geography and spatial planning, justice is seen as a powerful shared vision that helps bring research into political action (Harvey, Citation1996), though a somewhat “unknowable” concept that eludes consistent definition (Barkan & Pulido, Citation2017). A common fundamental interpretation of justice comprises fair allocation of cost and benefits and fair procedures to determine these distributive rules, i.e. outcome and process justice, both important to form a full picture of justice (Fainstein, Citation2010; Tyler, Citation2000).

2.1. Process justice

Process justice, or “just production justly arrived at” (Harvey, Citation2009, p. 98), has long been important for geographers. One should have the right to co-determine how a city develops (Marcuse, Citation2011). A basic starting point is communicative planning with open platforms, wide representation, flat hierarchy, and democratic participation (Achmani et al., Citation2020). However, some cautioned that these are no guarantee of just outcomes (Fainstein, Citation2010), for example by overlooking systematic distortions (Neuman, Citation2000). Critical geography emerged from this basis, focusing on the oppression of non-dominant groups (Przybylinski, Citation2022), and how social, institutional and political norms weaken public life participation by those oppressed (Young & Allen, Citation2011). It emphasises proactively identifying and involving the dominated, marginalised and powerless parties (Young & Allen, Citation2011). If not tackled in the planning stage, these injustices tend to preserve and reproduce themselves later in the policy outcomes (Dikeç, Citation2001).

Therefore, by combining these principles, process justice starts with an open, level, deliberative platform, with effective representation and democratic decision-making of all stakeholders, considering the broader and relevant structural, legal and institutional contexts. Furthermore, the process should strive to uncover and tackle injustices, e.g. dedicated measures to facilitate participation of socially disadvantaged groups.

2.2. Outcome justice

Justice in geography conventionally looks at fair distribution (Elster, Citation1992), mainly fundamental “primary goods and liberties” (Rawls & Kelly, Citation2001), such as affordable housing, personal mobility and accessibility (Martens, Citation2017). Equally important are the patterns of distribution (Przybylinski, Citation2022), essentially the allocation of resources that safeguards everyone’s fundamental welfare (Paul et al., Citation1995; Tyler, Citation2000), and close scrutiny of “the value of difference, particularity and pluralism” to decide on a differential treatment that favours disadvantaged people (Barnett, Citation2018, p. 6). Such individual-oriented outcome justice is also adapted in the well-known Capability Approach developed by Amartya Sen (Citation1995), focusing on opportunities available to individuals (termed “capabilities”), and environmental factors that enable or hinder their transformation into real achievements (termed “conversion factors”). Therefore, justice goes beyond an equal set of fundamental capabilities for everyone (Beyazit, Citation2011), but also suitable conversion factors, recognising human diversity and the freedom to exercise one’s agency (Robeyns & Byskov, Citation2021).

To summarise, outcome justice starts with a fair distribution of fundamental “primary goods”, the distribution of which should take into account the needs, wants and circumstances of different people, especially disadvantaged groups like children, older adults and the disabled, to compensate for their limited capabilities and conversion factors.

Equipped with the concepts of process and outcome justice, we can now proceed to explore common justice issues seen in TOD.

3. Methodology

We conducted a thematic review of justice-related TOD literature to identify the main justice issues of TOD, discuss their relation to process and outcome justice, and thus support the relevance and need for an analytical framework. When viewed through Van Wee and Banister (Citation2016)’s guidance on writing literature reviews, this paper belongs to a thematic review that aims to present a conceptual model and explore the literature that might help underpin the model that the paper. Our thematic review serves a comparable role to that in some other review-based conceptual papers, such as Cornet et al. (Citation2022)’s conceptual framework on “worthwhile travelling time” and Keseru et al. (Citation2019)’s framework on “citizen observatory for mobility”, where the frameworks’ purposes and themes were also derived from the literature reviewed.

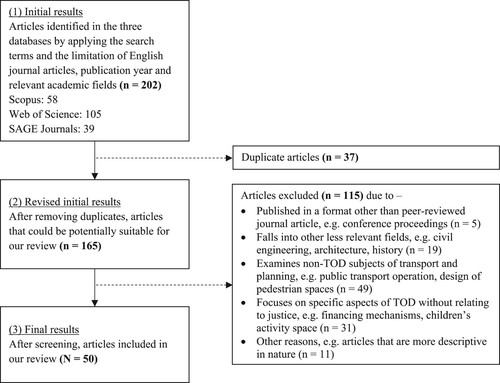

In our review, we chose the databases of Web of Science, Scopus, and SAGE Journals, considered the main large-scale bibliographic databases for TOD literature (Ibraeva et al., Citation2020). The search terms adopted were (“justice” OR “equity” OR “equality”) AND (“Transit-oriented development” OR any of its variants: “TOD”, “transit-oriented communities”, “transit village”, “mobility hub”, “hub development”, “station development”), to return results that relate to both justice and TOD. We limited the search to peer-reviewed journal articles in English, published on or after 2000, in the fields of social science, geography, planning, urban studies and transport. After removing duplicates and screening, 50 articles were finally included in the review, as illustrated in below.

Among the papers reviewed, the vast majority are empirical papers (n = 46) using mostly quantitative (e.g. sensitivity and factor analysis, predictive models, various statistical methods) and some qualitative methods (e.g. institution analysis, interviews). There a few review papers (n = 3) and conceptual paper (n = 1). Although not a perfect categorisation, this highlights the dominance of empirical studies and the limited engagement of TOD and justice conceptually. Consistent with bibliometric analysis by Shatu et al. (Citation2022) on TOD literature, most papers (n = 23) examined cases in the U.S.A., followed distantly by Canada (n = 4), China and India (n = 3 for both), Taiwan and Hong Kong (n = 2 for both), then 11 other places/countries each covered by one paper. A summary of the 50 papers reviewed, including their types, locations covered, objective and relevant key findings, is in Appendix 1.

We first relied on the review papers included in the review to obtain an overview of the justice implications of TOD. Using these as guidance, we then went through the empirical papers that examine specific justice dimensions of TOD cases, noting their objectives, main themes and key findings to group similar ones together. Finally, by identifying the subjects discussed most recurrently, combining and adjusting boundaries of related items, we synthesised and formulated the three main justice issues of TOD: (1) transit-induced gentrification; (2) neglect of the livelihood and well-being of disadvantaged groups; and (3) poor inclusion and representation of stakeholders.

4. Review findings – key justice issues of TOD

4.1. Transit-induced gentrification

Almost half of the papers reviewed (n = 24) relate to transit-induced gentrification, namely TOD raising the surrounding land and property values, attracting wealthier residents and displacing lower-income population and/or local businesses away from the TOD area (Padeiro et al., Citation2019). Studies have frequently found increases in average income, housing values and education levels of residents, the often-used indicators of gentrification, after a TOD is built (Padeiro et al., Citation2019), such as in San Francisco (Baker & Lee, Citation2019), Denver (Bardaka et al., Citation2018), New Jersey (Deka, Citation2016) in the U.S.A., Bangkok, Thailand (Matsuyuki et al., Citation2020) and Bangalore, India (Chava et al., Citation2018). The effects of gentrification differ case-by-case, depending such as on the typology of TOD (e.g. Park-and-Ride vs. Walk-and-Ride neighbourhoods) (Kahn, Citation2007), but often impoverished areas experience greater gentrification effects than affluent areas (Nilsson & Delmelle, Citation2018). For example, affordable public housing are relocated further away to give way to private housing at the TOD site (He et al., Citation2018), and other times ethnic minorities (Lung-Amam et al., Citation2019), temporarily settling refugees (Jones & Ley, Citation2016), or older adults (Chen et al., Citation2023) were displaced. The relocation may not be always apparent as displaced residents sometimes remain in the TOD “catchment area” but move to more periphery locations (Deka, Citation2016). Residents not displaced may still face challenges living in a gentrified neighbourhood, including discrimination and loss of social ties (Zuñiga & Houston, Citation2022), which relate to the second issue discussed in Section 4.2.

Transit-induced gentrification manifests as an issue in outcome justice. TOD exacerbates gentrification because of its reliance on capitalising on the increased land values over a whole area (Padeiro et al., Citation2019). Paradoxically, the better accessibility offered by TOD raises rent levels and drives away disadvantaged social groups, who are most dependent on accessible destinations and public transport offered by the TOD (Dong, Citation2017; Zhu & Diao, Citation2022). On the other hand, the higher-income “gentrifiers” sometimes still retain their entrenched habits of using automobiles instead of public transport in TOD (Matsuyuki et al., Citation2020). This reflects an outcome injustice - the socially disadvantaged are less able to enjoy the benefits of TOD (Padeiro et al., Citation2019), even though its implementation often involve significant public funds (Wang et al., Citation2022).

Furthermore, gentrification also involves issues in process justice. Lung-Amam et al. (Citation2019) argued that public advocacy and participation in the inception and planning of TOD are important points to prevent gentrification. In other examples of process issues, the inflated power of property developers in TOD compared to conventional urban development (Jones, Citation2020), limited involvement of local businesses and existing residents (Baker, Citation2020), and lack of focus on addressing gentrification-induced hardships faced by disadvantaged groups (Zuñiga & Houston, Citation2022) also lead to adverse effects in gentrification. Gentrification, therefore, relates to both outcome and process justice.

The papers reviewed also offered some directions to mitigate or prevent (potential) gentrification, which broadly falls into several categories including long-term engagement of existing communities in the planning process of TODs (Zuñiga & Houston, Citation2022), inclusionary zoning policies with strong community-based, cross-sector involvement (Lung-Amam et al., Citation2019) and protective policies for more disadvantaged groups such as integrated affordable housing requirements (Fainstein, Citation2010; Peng & Knaap, Citation2023).

It should be noted that in a review of TOD and gentrification, Padeiro et al. (Citation2019) concluded that while existing research indeed suggests TOD contributes to gentrification, local dynamics, built environment attributes, and broad planning and development policies also play significant roles, thus requiring further rigorous research to establish a strong causal link. Also interestingly, not all studies cast gentrification from TOD in a negative light, especially in greenfield new developments. For example, compared to an “ordinary” train station, TOD offers better access to public transport that benefits people of different incomes (Nazari Adli et al., Citation2020). Even with some signs of gentrification, TOD as new development holds the potential to support lower-income groups by creating economic opportunities (Zuñiga & Houston, Citation2022) and improving their mobility (Wang & Woo, Citation2017), especially in high-capacity TODs such as regional train stations (Tran & Draeger, Citation2021).

4.2. Neglect of livelihood and well-being of disadvantaged groups

Another justice issue identified is the comparably worse livelihood and well-being of the disadvantaged, deprived and marginalised groups in TOD neighbourhoods, an issue studied by over half of the papers reviewed (n = 28). Examples include features in TOD unfavourable to older adults (e.g. limited local transport and poor walking environment) in Tokyo, Japan (Chen et al., Citation2023), inadequacies to needs of families with children (e.g. affordable housing with accessible schools) in San Francisco, U.S.A. (Bierbaum & Vincent, Citation2013), lack of designs that safeguard vulnerable groups, such as needs of the disabled in Lahore, India (Malik et al., Citation2020), disproportionate defunding and cancellation of railway projects that predominantly serve certain ethnicities in U.S.A. (McFarlane, Citation2021) and TOD potentially exacerbating transport expense burdens of lower-income groups due to relocation of affordable housing in Nanjing, China (Wu et al., Citation2020). Though somewhat overlapping with transit-induced gentrification, we focus here on the actual poorer well-being of certain groups, which may or may not be due to gentrification.

This is a major issue of outcome justice in TOD. Benefits brought by a TOD are not always distributed fairly among different people living there (Luckey et al., Citation2018; Trudeau, Citation2018; Wey et al., Citation2016). Specific needs of disadvantaged groups, such as older adults (Chen et al., Citation2023) and families with children (Bierbaum & Vincent, Citation2013) may be overlooked, limiting the TOD’s beneficial effects for them. Worse still, gentrification and displacement could harm their welfare by breaking social ties and raising housing and transport costs (Lung-Amam et al., Citation2019; Wu et al., Citation2020). Those who are already well-off are likely to reap greater benefits, while those who started off as disadvantaged continue to receive smaller shares of benefits (Fainstein, Citation2010), sustaining or exacerbating outcome injustices.

Although details depend on the disadvantaged groups in question, there are various suggestions on how to address this justice, such as better connections between the TOD and the destinations frequently used by the disadvantaged groups (Chen et al., Citation2023), the incorporation of social equity as a fundamental part of the TOD vision and strategy (Malik et al., Citation2020; Trudeau, Citation2018), and formulating specific measures and incentives to better align the interests and actions of stakeholders towards improving well-being of disadvantaged groups (Bierbaum & Vincent, Citation2013; Trudeau, Citation2018), which could also include measures like affordable housing (Chen et al., Citation2023).

4.3 . Poor inclusion and representation of different stakeholders

Furthermore, TOD sometimes suffers from inadequate and ineffective inclusion and participation of stakeholders in the planning process, to which a significant number of papers reviewed (n = 16) relate. For example, in Johannesburg, South Africa, Harrison et al. (Citation2019) reported strong community frustration and criticisms towards the inadequate participation process of its “Inclusionary TOD”. Baker (Citation2020) found that in TOD projects in St. Louis, the U.S.A., black, lower-income and transit-dependent residents were overlooked in the planning process dominated by real estate developers. Sandoval (Citation2018) found that failure to meaningfully include communities of ethnic minorities in the planning process of TOD in U.S.A. led to their resistance in later completion stages.

These examples illustrate how the planning process of TOD, often driven by economic returns (He et al., Citation2018), can fail to allow fair stakeholder participation. Landowners and developers frequently command dominating power at the expense of less powerful stakeholders such as lower-income and ethnic minority residents (Abdi & Lamíquiz-Daudén, Citation2022; Sandoval, Citation2018). Furthermore, even stakeholders of more comparable power may still suffer from poor communication, lack of collaboration and competing goals in the TOD planning process, such as between planners, city officials, and public transport agencies (Banerjee et al., Citation2018).

This is not to mention that the most disadvantaged and also transit-dependent groups are often inherently less able to participate because of their literacy in planning matters, political power and social influence (Young & Allen, Citation2011). Yet we see that public actors may be inclined to limit planning participation to professionals (Baker, Citation2020), and only conduct “token participation” of public engagement that fails to involve interested parties meaningfully (Harrison et al., Citation2019), or disregards certain stakeholders’ input by consistently overruling them, e.g. on budgetary grounds (McFarlane, Citation2021). These are detrimental to creating process justice.

The papers reviewed suggested some remedial proposals, which share similarities with those of other issues. They include identifying key disadvantaged or neglected stakeholders, and then encouraging direct involvement and participatory decision-making in the planning process (Baker, Citation2020; McFarlane, Citation2021), enacting protective laws to safeguard the power and rights of disadvantaged stakeholders (Zuñiga & Houston, Citation2022), and fostering and mobilising grassroots and community-based action in the greater political arena (Lung-Amam et al., Citation2019; Sandoval, Citation2018).

These three key justice issues of TOD are closely related and straddle both outcome and process justice, requiring both perspectives to analyse their cause, meaning and impact. Therefore, to effectively analyse justice in TOD, we propose below an analytical framework that captures both process and outcome justice.

5. A proposed analytical framework

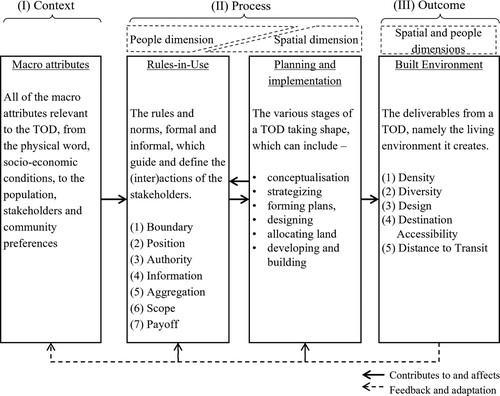

We begin with our proposed analytical framework in .

The overall structure of the proposed analytical framework is broadly based on the IAD model developed by Polski and Ostrom (Citation1999), and composed of three parts: (I) Context, (II) Process and (III) Outcome. (I) Context contains the social, economic and other macro attributes that relate to the TOD. This affects and contributes to the (II) Process, comprising the planning and implementation process of TOD which focuses more on a spatial dimension (e.g. land allocation and development), and the IAD model’s Rules-in-Use governing stakeholders’ interaction coming from a more people-oriented dimension. Eventually, the (III) Outcome of TOD comes to the built environment, including housing, facilities, public transport, etc., which we can analyse through the 5Ds of the built environment originating from Cervero and Kockelman (Citation1997), both from the spatial dimension (objectively measured 5Ds) and people dimension (satisfaction towards the 5Ds). The spatial and people division echoes the review of the travel, equity and wellbeing impacts of TOD conducted by Wang et al. (Citation2022), where the “D” in TOD was found to have multiple connotations focusing either on “environment” or “people”. We will further explain below what the spatial and people dimensions mean in (II) Process and (III) Outcome parts of our framework.

Afterwards, the built environment provides feedback to the components of (I) Context (such as by changing the population structure) and (II) Process (such as by creating more favourable Rules-in-Use for certain stakeholders). In the following, we proceed to explore the two models that form the framework’s backbone – the IAD and 5Ds models.

5.1. The IAD model

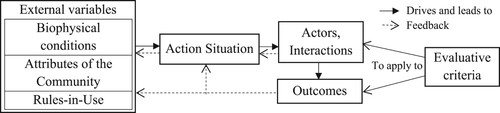

The IAD model is a method designed to comprehend the work of multiple actors in public policy and resource allocation (Polski & Ostrom, Citation1999). It facilitates systematically breaking down complex stakeholders' inclusion, interactions and power dynamics (Cole, Citation2017), which are important components of process justice, as briefly outlined in Section 2.1. The IAD model has been used to analyse stakeholders' interaction towards achieving a common goal, outcome or policy, such as Achmani et al. (Citation2020) adopting it to understand spatial inequalities in land management interventions. Likewise, we consider the IAD model well-suited for analysing process justice in TOD since it enables us to structurally examine themes such as stakeholder representation and participation, decision making, power dynamics, diverging and alignment of goals and interests between parties, which commonly appear in the process justice aspects of, and the suggested measures for, the three justice issues in our review above. With the aid of below, we briefly visit the IAD model and see how it is incorporated into our framework.

Figure 3. The IAD model. Adopted from: (Ostrom, Citation2005).

5.1.1. Action situation, actors and interactions

The IAD model centres on the Action Situation where participants interact, make decisions and cooperate (i.e. Interactions) to achieve the target Outcomes (Ostrom, Citation2011). In our analytical framework, the Action Situation translates to Part (II) Process, namely the TOD planning and implementation process governed by the Rules-in-Use. As for Actors, they should include every party (individuals, groups, institutions, etc.) that is interested in or relevant to the Action Situation, regardless of their actual participation (Ostrom, Citation2011).

5.1.2. Biophysical conditions and attributes of the community

Next are External Variables, which are the contextual factors that drive the Action Situation (Polski & Ostrom, Citation1999). The first two components – namely biophysical conditions and attributes of the community – are grouped together as Part (I) Contexts in our analytical framework. It is because while relating to the motivation for TOD, they do not form the core of examining justice.

5.1.3. Rules-in-use

The component of “Rules-in-Use” holds the key to understanding process justice. They are often implicit, hidden systems that dictate the participation, interaction and decision-making of Actors (Polski & Ostrom, Citation1999). Rules-in-Use, formal and informal, “concentrate on the operating rules that are commonly used by most participants and on the source of these rules, rather than on well-articulated but not widely observed rules” (p. 23). They are divided into seven types as shown in .

Table 1. The seven Rules-in-Use in the IAD model.

As noted by Blomquist and deLeon (Citation2011), the Rules-in-Use is the key element to analyse because they guide, influence and delineate the Interactions in the Action Situation. Ostrom herself placed great importance and effort on developing and refining the Rules-in-Use (Cole, Citation2017). We have adapted them in Part (II) Process of the analytical framework, as the metrics of analysing process justice in TOD. While they inherently focus more on the people dimension (namely, the stakeholders), they also shed light on the justice implications of spatial dimensions in the TOD planning process, as we elaborate rule-by-rule below.

5.2. Evaluative criteria of process justice in TOD

5.2.1. Boundary

The main principle of “Boundary” is that all relevant or interested stakeholders should be able to access and participate in the TOD planning process. Ideally, this should be formalised in legislation, though it is equally important that legislation is not used to ring-fence the process to exclude certain stakeholders (Cascetta & Pagliara, Citation2013), for example, when a fixed panel of officially appointed “representatives” serve as the same token of public engagement for every project (Bryan et al., Citation2007).

Furthermore, it is critical to actively identify and include disadvantaged populations – e.g. older adults, the disabled and (ethnic) minorities to improve their representation. They may be less aware of ongoing initiatives like TOD that could affect them, face language, cultural and knowledge barriers in public participation (Sandoval, Citation2018), and have specific challenges and needs to be catered to (Lung-Amam et al., Citation2019).

5.2.2. Position

The “Position” of different parties in TOD depends on their expertise, roles, functions, and broader societal and political contexts. The government usually holds the dominating position (Ibrahim et al., Citation2022), with national, provincial and local units setting strategies, developing plans, and implementing projects, respectively (Mittal & Shah, Citation2021). Landowners and developers may also wield substantial power (He et al., Citation2018). Public transport operators provide the essential component of “T” in TOD, though their position may be limited to operational levels with little influence on strategic decisions (Cascetta & Pagliara, Citation2013). Other parties, such as advocacy groups, NGOs, (existing) residents and commercial actors, may play more periphery positions of giving comments, often only when invited (Zuñiga & Houston, Citation2022).

To deliver process justice, the “Position” rule should ensure that all parties of similar roles, goals and interests can engage, compromise and interact on an equal footing. For example, when it comes to residents, different potential and existing residents (of various incomes, ethnicities, social groups, etc.) should be able to engage with other stakeholders fairly (Sandoval, Citation2018) by facilitating diverse groups of similar interests to take up comparable positions (Trudeau, Citation2018), such as on a planning panel.

5.2.3. Authority

Similar to “Position” rules, overarching “Authority” in a TOD usually falls to a government (Mittal & Shah, Citation2021). Beyond these, different parties may hold authority over their respective spheres, such as operators of public transport, commercial developers of office spaces, and housing associations on residential development. Such ownership and development rights of land in TOD affect process justice from a spatial dimension.

For parties with substantial authority, e.g. the government, it is important that their power be clearly and formally defined, such as who to seek input, agreement or consult (Humphreys, Citation2012). As for groups of competing interests, they should hold balanced authorities. For example, in allocating a piece of land, all interested stakeholders (e.g. housing organisations, retail corporations and private developers) should start with the same opportunity and means to give input and influence the planning process (Wagner, Citation2013). Meanwhile, some positive discrimination should be in place to safeguard the interests of disadvantaged, such as representation via advocacy groups (Lung-Amam et al., Citation2019). There should also be oversight to ensure that powerful stakeholders do not take advantage of their influence beyond their roles and responsibilities, such as developers of station-top shopping malls also controlling and restricting the use of infrastructure like pedestrian connections (Al-Kodmany et al., Citation2022).

5.2.4. Information

“Information” can include matters from broad strategies, population targets to architectural and street designs. Information that widely affects the interests of different stakeholders should be made easily accessible (Fainstein, Citation2010). These can include the overall zoning plans, design rationale and principles, and development stages and timeframe of the TOD. Stakeholders should be able to understand the information effectively, weigh its significance, give feedback and make decisions (Hossinger et al., Citation2004). Special attention should be given to highly technical information (Wagner, Citation2013), with workshops and demonstrations potentially useful for the public to grasp and comment on such (Pojani & Stead, Citation2015). For disadvantaged groups, advocacy groups can help with digesting information and reacting appropriately to safeguard their welfare (Lung-Amam et al., Citation2019).

5.2.5. Aggregation

“Aggregation” concerns how decisions are made, collectively or individually (Ostrom, Citation2011). While democratic decision-making calls for considering everyone’s interests and welfare (Fainstein, Citation2010), it is not always practical – not every decision can be made by “majority rules”, given the various and complex decisions in TOD planning (Humphreys, Citation2012). Further still, democracy is no guarantee of justice – given our imperfect information, self-interested nature and preference for short-term gains, decisions made democratically may still harm justice by neglecting the disadvantaged population (Fainstein, Citation2010; Neuman, Citation2000). Therefore, open democratic planning is important but not an unyielding rule.

“Aggregation” becomes particularly important in decisions that involve critical resources and competing interests (such as development rights of land-plots close to the train station). In this scenario, a disinterested party (e.g. an independent planning commission) consisting of a broad spectrum of members should host an open and accessible platform for all relevant stakeholders to express their views, make suggestions and provide justifications (Cascetta & Pagliara, Citation2013). Since TOD inherently advocates for the integration and densification of different land-use functions, there are more occasions for different stakeholders to make decisions on spatial resources aggregately, such as developing a mixed-use site together. In such collective interactions which affect the use of and benefit from land resources, the disinterested party should make decisions with a good balance of interests while safeguarding the disadvantaged. Its deliberations and reasoning should be clear and transparent for all to view, question or challenge.

5.2.6. Scope

“Scope” somewhat overlaps with “Authority”, though “Authority” relates more to exercising power and making decisions, while “Scope” concerns the ultimate goals and visions of the parties (McGinnis, Citation2011). Justice in “Scope” can be interpreted as the respect, fair treatment and aligning of every parties’ controllable goals and ultimate visions.

For example, a private property developer seeks to maximise profits (Marcuse, Citation2011), which translates to obtaining and developing the most desirable plots closest to the train station (He et al., Citation2018). This will often be at odds with the scopes of other stakeholders, such as social housing whose aim is to provide affordable accommodation with accessible public transport for low-income residents. If the most suitable lands are all purchased by private developers, then a discrepancy would be created between the two visions of building premium residences and housing the needy, with the former better realised than the latter. We can evaluate justice by comparing whether the scopes of different parties are fulfilled, and whether discrepancies exist between the vision and reality of certain stakeholders (Wagner, Citation2013). To realise justice, the government should actively intervene and balance any greatly divergent visions and realities of certain parties (Harvey, Citation1996), such as by planning for a mix of housing and development types.

5.2.7. Payoff

Broadly speaking, we may evaluate “Payoff” by examining who bears the costs and who reaps the benefits in TOD. “Payoff” include non-financial items like housing and services, and also spatial resources, especially when TOD is primarily a land development strategy, for example in Asia (Liang et al., Citation2020; Wey et al., Citation2016).

Firstly, we examine how the costs (e.g. in constructing infrastructure and facilities) are allocated to the stakeholders. There are various cost allocation mechanisms used in TOD, such as Build-Operate-Transfer agreementFootnote1 (Al-Kodmany et al., Citation2022) and leasing arrangementsFootnote2 (Matsuyuki et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, social costs may also arise in the form of existing residents and businesses evicted and forced to relocate due to redevelopment (Sandoval, Citation2018). Then, we compare the distribution of benefits – who gains the use of land, transport and infrastructure? Are existing residents and businesses able to benefit from the TOD in their redeveloped neighbourhood? Do certain stakeholders receive a greater share of benefits (such as high-end residences occupying gentrified plots close to the train station)? Though this can simply be a legitimate result of the market mechanism, one must recall that the vision of TOD is to create sustainable and equitable communities, not only to drive economic development (Jamme et al., Citation2019). Therefore, not only economic benefits but also social returns, such as the number of residents of different income levels housed, should also be considered. To this end, it is important to devise and implement “Payoff” rules at the beginning of the planning process, such as a balanced mix of housing in the strategic plans (Fainstein, Citation2010).

5.3. 5Ds of the built environment

With process justice examined through the IAD model, we now turn to outcome justice via another model – the 5Ds of the built environment, namely (a) Density, (b) Diversity, (c) Design, (d) Destination Accessibility, and (e) Distance to Transit (Thomas & Bertolini, Citation2020), which trace their origins back to the 3Ds developed by Cervero and Kockelman (Citation1997) as the criteria in creating successful TODs as equitable and inclusive communities. The 5Ds are now formulated as the essential elements of the built environment delivered by a TOD (Hrelja et al., Citation2020; Jamme et al., Citation2019), as outlined in below.

Table 2. Key definition and commonly used indicators of 5Ds.

The 5Ds provide a structured approach to describe the desired deliverables of TOD. In our thematic review in Section 4 above, we saw that the outcome justice aspects of, and the proposed measures in response to, the three TOD justice issues share common themes in the availability and distribution of certain “deliverables of TOD”. These include affordable housing, public transport service, community resources, social amenities and appropriate designs for certain social groups. The 5Ds also tend to go together in contributing to accessibility, a comprehensive measure of land-use and transport integration (Handy, Citation2018). TOD itself is closely tied to accessibility planning, with some even proposing Accessibility-oriented Development to be TOD’s successor (Deboosere et al., Citation2018). Therefore, we find the 5Ds useful in examining and comparing these “TOD deliverables” in different neighbourhoods, and thereby in analysing outcome justice from the spatial dimension.

In addition, we may also view the 5Ds from a people dimension through the satisfaction of residents towards the 5Ds. People’s satisfaction and well-being are increasingly valued in the discussion of justice (Barnett, Citation2018), particularly in more individual-oriented justice concepts, e.g. Amartya Sen (Citation1995)’s Capability Approach. In the context of TOD, discrepancies in residential satisfaction can be a common manifestation of the justice issues we reviewed, especially transit-induced gentrification and neglect of livelihood and well-being of disadvantaged groups, given the generally accepted relation between the built environment and residential satisfaction (Chen et al., Citation2022). Many researchers have explored the effects of the 5Ds on residential satisfaction in relation to other planning topics, such as urban stratification (Wen et al., Citation2022), metro station development (Li et al., Citation2018), and urban environment with limited modal choice (Olfindo, Citation2021). Residential satisfaction could also deviate from objective measurements of the built environment due to self-selection preferences, individual perception and other factors (Jansen, Citation2012; Smrke et al., Citation2018). Therefore, analysing outcome justice from a people dimension through the satisfaction of residents towards the 5Ds in their neighbourhoods is also essential. Using both the spatial and people dimensions, we discuss below the evaluative criteria for each of the 5Ds to analyse outcome justice in TOD.

5.4. Evaluative criteria of outcome justice in TOD

5.4.1. Density

While historically TOD aimed to encourage higher density, studies have revealed a generally negative correlation between density and residential satisfaction in an urban setting (Yin et al., Citation2019), though satisfaction at a certain density also depends on other factors like local services, green spaces and such (Bramley et al., Citation2009), namely the other Ds. On the other hand, preferences for moderate or low densities are harder to predict, with different studies of satisfaction yielding contrasting or insignificant correlations (Smrke et al., Citation2018).

From the spatial dimension, we may assess justice by comparing whether the densities of different neighbourhoods around a TOD show marked discrepancy. In other words, are there particular neighbourhoods that are much denser than others (e.g. social housing vs. private residences) which potentially affects the residents’ quality of life? Correspondingly, from the people dimension, given the variation in an individual’s preferences towards density (Smrke et al., Citation2018), we may also compare the subjective satisfaction of different TOD residents towards the densities of their neighbourhood, and note whether there are marked differences.

5.4.2. Diversity

A varied mix of housing, retail, services and facilities – i.e. a high functional diversity, contributes significantly to residents’ satisfaction (Tridib Banerjee et al., Citation2018; Chen et al., Citation2022), and is also a key promised benefit of TOD (Thomas & Bertolini, Citation2020). We may view “diversity justice” in TOD from the spatial dimension: Is there a diverse mix of different housing for people of different income (e.g. affordable housing), needs and preferences (e.g. families, older adults)? Changes in housing types were found to be one of the implications of gentrification (Padeiro et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, are there diverse shops, services and facilities in different neighbourhoods? Diverse shops may be found at the shopping mall developed at the train station, but less so towards the periphery of the TOD (Curtis & Renne, Citation2016), hinting at injustices for the residents living further away from the station. On the other hand, the diversity of shops around the train station may cater more to commuters and visitors using the station but neglects the needs of existing residents, especially disadvantaged groups (Noland et al., Citation2017). We can also examine this from the people dimension – are different residents satisfied with the functional diversity in their neighbourhoods? A lack of diverse shops and services limits residents’ choices and harms their living satisfaction (Baker & Lee, Citation2019), but excessive diversity may indicate overcrowding which also negatively affects life satisfaction (Chen et al., Citation2022).

5.4.3. Design

Design involves many elements, from networks, facilities to infrastructure designs (Jamme et al., Citation2019). In the context of justice, we may assess and compare the living environments between different neighbourhoods, such as Appleyard et al. (Citation2019)’s comparison of neighbourhoods in different TOD stations. From the spatial dimension, do the TOD designs foster pleasant and safe walking, cycling and travelling within the neighbourhood? From the people dimension, are there dedicated designs that cater to those with specific needs, such as older adults and the disabled? As we have seen in the review in Section 4.2, this may not be the case, such as for older adults and young children. Design measures to address this include better wayfinding, pedestrian connections, and street furniture.

5.4.4. Destination accessibility

A higher level of accessibility to destinations contributes to a better quality of life (Deboosere et al., Citation2018). In terms of justice, we can compare the Destination Accessibility between different neighbourhoods, namely the availability of various destinations in the spatial dimension, such as shops and leisure facilities (somewhat overlapping with Diversity), and how easy it is to reach them (to which Design is relevant). Do more well-off social groups enjoy greater Destination Accessibility because they reside in more “premium” locations? Furthermore, on the people dimension, it is also worth noting the clientele of the accessible destinations. For example, gentrification can lead to the loss of local businesses (Jones & Ley, Citation2016) replaced by shops and retail catering more to commuters and tourists but less frequented by the community (Noland et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, we should also pay attention to disadvantaged residents and their needs, such as older adults and the disabled – their desired destinations, from shopping, community spaces, to healthcare services, often differ from commuters for which TOD are designed (Chen et al., Citation2023).

5.4.5. Distance to transit

Providing accessible public transport is a common promise of TOD (Thomas & Bertolini, Citation2020). Therefore, from the spatial dimension, it is important to consider whether certain groups of residents disproportionally enjoy greater access to the train station and local public transport (including distance, costs, and barriers) than other residents. For those living in neighbourhoods in the periphery of the TOD, local transport within the TOD area becomes even more important, either to access the train station or elsewhere outside. When viewed from the people dimension, lower-income and disadvantaged groups (e.g. older adults and the disabled) are often more dependent on public transport (Matsuyuki et al., Citation2020; Tao et al., Citation2022), which makes their satisfaction towards “Distance to Transit” even more relevant. Residents’ reported satisfaction may also show discrepancies with objective measurements of “Distance to Transit” due to dissonance in the attitudes towards using automobiles and public transport (De Vos et al., Citation2014). Therefore, measuring from both the people and spatial dimensions is essential.

6. Conclusion

6.1. Key takeaway points

Through our review, we identified three key justice issues in TOD: transit-induced gentrification; neglect of the livelihood and well-being of disadvantaged groups; and poor inclusion and representation of stakeholders. They are inter-related and straddle both outcome and process justice. Therefore, we devised an analytical framework that integrates the IAD model and the 5Ds of the built environment to facilitate analysing process and outcome justice in TOD. We briefly discuss below how the analytical framework can be operationalised.

6.2. Operational use of the analytical framework

Firstly, Part (I) Context concerns macro attributes (e.g. socio-economic conditions) which establish the background rationale and objectives of the TOD.

The core analysis of justice then takes place in Part (II) Process and Part (III) Outcome of the framework applicable to the vast variety of TOD types and subjects, both ex-ante and ex-post evaluations. Ex-ante evaluations regarding a work-in-progress TOD include observing stakeholders’ interactions to analyse process justice (people-dimension), and examining the plans for the station neighbourhood (spatial-dimension) to analyse outcome justice; while ex-post evaluations regarding a completed TOD can also include interviewing stakeholders to understand their experiences during previous planning to analyse process justice (people-dimension), and surveying residents on their satisfaction towards the 5Ds (people-dimension), or examining the built environment (spatial-dimension) to analyse outcome justice. below offers some suggested questions that could guide actual analysis using our framework, with some examples of past studies related to the sets of questions included for reference. The answers collected can then be assessed against the evaluative criteria outlined in Sections 5.2 (for process justice) and 5.4 (for outcome justice). Such an assessment can also provide insights into how (in)justice in the TOD planning process influences (in)justice in achieved TOD outcomes.

Table 3. Suggested guidance questions to analyse justice in TOD with the framework.

6.3. Significance and challenges of using the analytical framework

With its central aim to analyse justice in TOD, the analytical framework holds the following key functions and significance. Firstly, it helps raise awareness of the justice implications of TOD, especially in the various components of its planning and implementation. Public awareness is an important step in driving political action to pursue justice in TOD (Harrison et al., Citation2019). Secondly, it helps us better incorporate justice concepts when planning and implementing TODs. The framework provides a more structured roadmap to uphold justice while taking forward TOD projects and initiatives. Thirdly, the framework also helps evaluate the justice implications of a completed TOD more systematically and comprehensively.

As a simplified ex-post evaluation example, say that a completed TOD neighbourhood shows signs of transit-induced gentrification. Using the framework, we may examine the planning process to discover the participation, interactions and power dynamics of stakeholders, such as identifying disadvantaged populations and social housing organisations as under–represented or –participated in the process as contributing factors of gentrification. As for the outcome, we may also compare the 5D attributes and residents’ satisfaction between various neighbourhoods, providing insights into the reasons behind gentrification. Even further, the 5D attributes can also help guide measures to mitigate gentrification, such as the specific built environment features to improve upon.

Naturally, there are certain challenges in using the analytical framework. Firstly, the framework is intended as broad guidance and does not offer specific indicators. As such, one needs to develop specific questions and indices for the topic concerned in accordance with this framework aiming to provide general guidance, as illustrated in . Second is the broad coverage and usage of the term TOD, which could refer to national strategies, regional plans, local development and neighbourhood projects (Hrelja et al., Citation2020; Jamme et al., Citation2019). The exact catchment area of a TOD is also open to interpretation, ranging from a radius of fixed distance, walking/cycling or travel time to the main transit station, to covering places where potential transit users live or where land prices are affected by the TOD (Sung et al., Citation2014; Tong et al., Citation2018). This makes it harder to delineate the “Process” and “Outcome” of TOD consistently. While acknowledging the importance of consistency in defining the catchment area of TOD, especially when comparing cases, we believe the framework still holds great promise for comparative studies by breaking up justice into structured elements, for example in discovering components in a TOD that strengthen or inhibit process or outcome justice to be learned or avoided by others. Third is the analysis of TOD in relative isolation from boarder transport and planning strategies and policies. These strategies and polices could play important roles in TOD (Hrelja et al., Citation2020) but are relegated to (I) Contexts of the framework. This echoes with certain critiques towards the IAD model in giving inadequate attention to the broader power and interests in how institutions are created, e.g. the delineation of government units (Clement, Citation2010), and treating decision-making of stakeholders as independent of larger social and historical contexts (Agrawal, Citation2001). We may address these challenges by using the framework at an upper level and analysing justice in the formulation of relevant broader strategies and policies, supplementing analysing justice in TOD.

In closing, the analytical framework can guide various future research on justice and TOD, from analysing good practices and lessons learned in specific TODs to larger-scale comparisons between justice in TODs in different countries. This fits with the growing scholarly interests in TOD policy transferability across countries (Thomas et al., Citation2018) and disparities in transport and planning between the Global North vs. Global South (Abdi & Lamíquiz-Daudén, Citation2022). As such, the framework strives to help advance TOD’s original vision to create just, liveable, and sustainable communities.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (34.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In a Build-Operate-Transfer agreement, private developers fund and build the infrastructure as per the government’s specifications, owns the exclusive right to receive fares and toll for a specified duration, and at the end of said duration transfers ownership of the infrastructure back to the government.

2 For example, in a lease arrangement for a new railway line, the government funds and builds the railway infrastructure, then allow transit operators to use them for regular lease payments.

References

- Abdi, M. H., & Lamíquiz-Daudén, P. J. (2022). Transit-oriented development in developing countries: A qualitative meta-synthesis of its policy, planning and implementation challenges. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 16(3), 195–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/15568318.2020.1858375

- Achmani, Y., Vries, W. T. d., Serrano, J., & Bonnefond, M. (2020). Determining indicators related to land management interventions to measure spatial inequalities in an urban (re)development process. Land, 9(11), 448. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9110448

- Agrawal, A. (2001). Common property institutions and sustainable governance of resources. World Development, 29(10), 1649–1672. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00063-8

- Al-Kodmany, K., Xue, Q., & Sun, C. (2022). Reconfiguring vertical urbanism: The example of tall buildings and transit-oriented development (TB-TOD) in Hong Kong. Buildings, 12(2), 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12020197

- Appleyard, B. S., Frost, A. R., & Allen, C. (2019). Are all transit stations equal and equitable? Calculating sustainability, livability, health, & equity performance of smart growth & transit-oriented-development (TOD). Journal of Transport & Health, 14, 100584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2019.100584

- Baker, D. M. (2020). Inclusion and exclusion in establishing the Delmar loop transit-oriented development site. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 43(4), 897–916. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X20929760

- Baker, D. M., & Lee, B. (2019). How does light rail transit (LRT) impact gentrification? Evidence from fourteen US urbanized areas. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 39(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X17713619

- Banerjee, T., Bahl, D., Barrow, K., Eisenlohr, A., Rodriguez, J., Wallace, Q., & Jamme, H.-T. (2018). Institutional Response to Transit Oriented Development in the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area: Understanding Local Differences through the Prism of Density, Diversity, and Design. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.30327.78240.

- Bardaka, E., Delgado, M. S., & Florax, R. J. G. M. (2018). Causal identification of transit-induced gentrification and spatial spillover effects: The case of the Denver light rail. Journal of Transport Geography, 71, 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.06.025

- Barkan, J., & Pulido, L. (2017). Justice: An epistolary essay. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 107(1), 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2016.1230422

- Barnett, C. (2018). Geography and the priority of injustice. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 108(2), 317–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2017.1365581

- Beyazit, E. (2011). Evaluating social justice in transport: Lessons to be learned from the capability approach. Transport Reviews, 31(1), 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2010.504900

- Bierbaum, A. H., & Vincent, J. M. (2013). Putting schools on the Map: Linking transit-oriented development, households with children, and schools. Transportation Research Record, 2357(1), 77–85. https://doi.org/10.3141/2357-09

- Blomquist, W., & deLeon, P. (2011). The design and promise of the institutional analysis and development framework. Policy Studies Journal, 39(1), 1–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00402.x

- Bramley, G., Dempsey, N., Power, S., Brown, C., & Watkins, D. (2009). Social sustainability and urban form: Evidence from five British cities. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 41(9), 2125–2142. https://doi.org/10.1068/a4184

- Bryan, V., Jones, B., Allen, E., & Collins-Camargo, C. (2007). Civic engagement or token participation? Perceived impact of the citizen review panel initiative. Children and Youth Services Review, 29(10), 1286–1300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.05.002

- Calthorpe, P. (1993). The next American metropolis: Ecology, community, and the American dream. Princeton Architectural Press.

- Cascetta, E., & Pagliara, F. (2013). Public engagement for planning and designing transportation systems. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 87, 103–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.10.597

- Cervero, R., & Kockelman, K. (1997). Travel demands and 3Ds: Density, diversity and design. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 2(3), 199–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1361-9209(97)00009-6

- Cervero, R., & National Research Council (U.S.). Transportation Research Board., Transit Cooperative Research Program., United States. Federal Transit Administration., & Transit Development Corporation (2004). Transit-oriented development in the United States: Experiences, challenges, and prospects. Transportation Research Board. http://trb.org/publications/tcrp/tcrp_rpt_102.pdf.

- Chava, J., Newman, P., & Tiwari, R. (2018). Gentrification of station areas and its impact on transit ridership. Case Studies on Transport Policy, 6(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2018.01.007

- Chen, Q., Yan, Y., Zhang, X., & Chen, J. (2022). A study on the impact of built environment elements on satisfaction with residency whilst considering spatial heterogeneity. Sustainability, 14(22), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215011

- Chen, Z., Li, P., Jin, Y., Bharule, S., Jia, N., Li, W., Song, X., Shibasaki, R., & Zhang, H. (2023). Using mobile phone big data to identify inequity of aging groups in transit-oriented development station usage: A case of Tokyo. Transport Policy, 132, 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2022.12.010

- Clement, F. (2010). Analysing decentralised natural resource governance: Proposition for a “politicised” institutional analysis and development framework. Policy Sciences, 43, 129–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-009-9100-8

- Cole, D. H. (2017). Laws, norms, and the institutional analysis and development framework. Journal of Institutional Economics, 13(4), 829–847. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744137417000030

- Cornet, Y., Lugano, G., Georgouli, C., & Milakis, D. (2022). Worthwhile travel time: A conceptual framework of the perceived value of enjoyment, productivity and fitness while travelling. Transport Reviews, 42(5), 580–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2021.1983067

- Curtis, C., & Renne, J. L. (Eds.). (2016). Transit oriented development: Making it happen. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315550008

- Deboosere, R., El-Geneidy, A. M., & Levinson, D. (2018). Accessibility-oriented development. Journal of Transport Geography, 70, 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.05.015

- Deka, D. (2016). Benchmarking gentrification near commuter rail stations in New Jersey. Urban Studies, 54(13), 2955–2972. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016664830

- De Vos, J., Van Acker, V., & Witlox, F. (2014). The influence of attitudes on transit-oriented development: An explorative analysis. Transport Policy, 35, 326–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2014.04.004

- Dikeç, M. (2001). Justice and the spatial imagination. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 33(10), 1785–1805. https://doi.org/10.1068/a3467

- Dong, H. (2017). Rail-transit-induced gentrification and the affordability paradox of TOD. Journal of Transport Geography, 63, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2017.07.001

- Elster, J. (1992). Local justice: How institutions allocate scarce goods and necessary burdens. Russell Sage Foundation. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.77589781610441834.

- Fainstein, S. S. (2010). The just city. Cornell University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591j.ctt7zhwt.

- Handy, S. (2018). Enough with the “D’s” already—let’s get back to “A.”. Transfers Magazine, 1, 1–3. http://transfersmagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2018/05/Susan-Handy-_-Enough-with-the-Ds.pdf

- Harrison, P., Rubin, M., Appelbaum, A., & Dittgen, R. (2019). Corridors of freedom: Analyzing Johannesburg’s ambitious inclusionary transit-oriented development. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 39(4), 456–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X19870312

- Harvey, D. (1996). Justice, nature, and the geography of difference. Blackwell Publishers. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591j.ctt7zhwt.

- Harvey, D. (2009). Social justice and the city (Revised Edition). University of Georgia Press. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/rug/detail.action?docID=3038870

- He, S. Y., Tao, S., Hou, Y., & Jiang, W. (2018). Mass transit railway, transit-oriented development and spatial justice: The competition for prime residential locations in Hong Kong since the 1980s. Town Planning Review, 89(5), 467–493. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2018.31

- Hossinger, R., Jones, P., Barta, F., Kelly, J., Witte, A., & Wolfe, A. (2004). Successful transport decision-making: A project management and stakeholder engagement handbook. GUIDEMAPS Consortium. https://trid.trb.org/view/1157841.

- Hrelja, R., Olsson, L., Pettersson-Löfstedt, F., & Rye, T. (2020). Transit Oriented Development (TOD): A Literature Review. The Swedish Knowledge Center for Public Transport: K2 Research, 2. https://www.k2centrum.se/transit-oriented-development-tod-literature-review.

- Humphreys, J. (2012). A critical evaluation of the role of public consultation in transport planning, With particular reference to the city of York’s local transport plan. Irish Transport Research Network, Belfast, Ireland. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332182794_A_Critical_Evaluation_of_the_Role_of_Public_Consultation_in_Transport_Planning_With_Particular_Reference_to_the_City_of_York's_Local_Transport_Plan.

- Ibraeva, A., Correia, G. H., de, A., Silva, C., & Antunes, A. P. (2020). Transit-oriented development: A review of research achievements and challenges. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 132, 110–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2019.10.018

- Ibrahim, S. M., Ayad, H. M., & Saadallah, D. M. (2022). Planning transit-oriented development (TOD): A systematic literature review of measuring the transit-oriented development levels. International Journal of Transport Development and Integration, 6(4), 378–398. https://doi.org/10.2495/TDI-V6-N4-378-398

- Israel, E., & Frenkel, A. (2018). Social justice and spatial inequality: Toward a conceptual framework. Progress in Human Geography, 42(5), 647–665. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517702969

- Jamme, H.-T., Rodriguez, J., Bahl, D., & Banerjee, T. (2019). A twenty-five-year biography of the TOD concept: From design to policy, planning, and implementation. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 39, 409–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X19882073

- Jansen, S. J. T.. (2012). The Impact of Socio-Demographic Characteristics, Objective Housing Quality and Preference on Residential Satisfaction. OTB Working Papers, 2012(7). http://resolver.tudelft.nl/uuid:8c3a9369-9fd7-42b9-bda0-08b5a32ba195.

- Jones, C. E. (2020). Transit-oriented development and suburban gentrification: A “natural reality” of refugee displacement in metro Vancouver. Housing Policy Debate, 533–552. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2020.1839935

- Jones, C. E., & Ley, D. (2016). Transit-oriented development and gentrification along metro Vancouver’s low-income SkyTrain corridor. Canadian Geographer, 60(1), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12256

- Kahn, M. E. (2007). Gentrification trends in new transit-oriented communities: Evidence from 14 cities that expanded and built rail transit systems. Real Estate Economics, 35(2), 155–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6229.2007.00186.x

- Keseru, I., Wuytens, N., & Macharis, C. (2019). Citizen observatory for mobility: A conceptual framework. Transport Reviews, 39(4), 485–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2018.1536089

- Li, W., Sun, B., Yin, C., Zhang, T., & Liu, Q. (2018). Does metro proximity promote happiness? Evidence from Shanghai. Journal of Transport and Land Use, 11(1), 1271–1285. https://doi.org/10.5198/jtlu.2018.1286

- Liang, Y., Du, M., Wang, X., & Xu, X. (2020). Planning for urban life: A new approach of sustainable land use plan based on transit-oriented development. Evaluation and Program Planning, 80, 101811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2020.101811

- Lin, J. J., & Gau, C. C. (2006). A TOD planning model to review the regulation of allowable development densities around subway stations. Land Use Policy, 23(3), 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2004.11.003

- Liu, L., Zhang, M., & Xu, T. (2020). A conceptual framework and implementation tool for land use planning for corridor transit oriented development. Cities, 107, 102939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102939

- Luckey, K. S., Marshall, W. E., Durso, C., & Atkinson-Palombo, C. (2018). Residential preferences, transit accessibility and social equity: Insights from the Denver region. Journal of Urbanism, 11(2), 149–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2017.1422531

- Lung-Amam, W., Pendall, R., & Knaap, E. (2019). Mi casa no es Su casa: The fight for equitable transit-oriented development in an inner-ring suburb. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 39(4), 442–455. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X19878248

- Malik, B. Z., Rehman, Z. u., Khan, A. H., & Akram, W. (2020). Women’s mobility via bus rapid transit: Experiential patterns and challenges in Lahore. Journal of Transport & Health, 17, 100834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2020.100834

- Marcuse, P. (2011). Whose right(s) to what city? In P. Marcuse, M. Mayer, & N. Brenner (Eds.), Cities for people, not for profit (1st ed., pp. 24–41). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203802182

- Martens, K. (2017). Transport justice: Designing fair transportation systems. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315746852

- Matsuyuki, M., Aizu, N., Nakamura, F., & Leeruttanawisut, K. (2020). Impact of gentrification on travel behavior in transit-oriented development areas in Bangkok, Thailand. Case Studies on Transport Policy, 8(4), 1341–1351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2020.09.005

- McFarlane, A. G. (2021). Black transit: When public transportation decision-making leads to negative economic development. Iowa Law Review, 106(5), 2369–2396. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3871151

- McGinnis, M. (2011). An introduction to IAD and the language of the ostrom workshop: A simple guide to a complex framework. Policy Studies Journal, 39(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00401.x

- Mittal, H., & Shah, A. (2021). Discursive politics and policy (im)mobility: Metro-TOD policies in India. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 40(2), 463–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/23996544211029295

- Mohiuddin, H. (2021). Planning for the first and last mile: A review of practices at selected transit agencies in the United States. SUSTAINABILITY, 13(4), 2222. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042222

- Nazari Adli, S., Chowdhury, S., & Shiftan, Y. (2020). Evaluating spatial justice in rail transit: Access to terminals by foot. Journal of Transportation Engineering Part A: Systems, 146(9), 04020101. https://doi.org/10.1061/JTEPBS.0000419

- Neuman, M. (2000). Communicate this! Does consensus lead to advocacy and pluralism? Journal of Planning Education and Research, 19(4), 343–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X0001900403

- Nilsson, I., & Delmelle, E. (2018). Transit investments and neighborhood change: On the likelihood of change. Journal of Transport Geography, 66, 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2017.12.001

- Noland, R. B., Weiner, M. D., DiPetrillo, S., & Kay, A. I. (2017). Attitudes towards transit-oriented development: Resident experiences and professional perspectives. Journal of Transport Geography, 60, 130–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2017.02.015

- Olfindo, R. (2021). Transport accessibility, residential satisfaction, and moving intention in a context of limited travel mode choice. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 145, 153–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2021.01.012

- Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7s7wm.

- Ostrom, E. (2011). Background on the institutional analysis and development framework: Ostrom: Institutional analysis and development framework. Policy Studies Journal, 39(1), 7–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00394.x

- Padeiro, M., Louro, A., & da Costa, N. M. (2019). Transit-oriented development and gentrification: A systematic review. Transport Reviews, 39(6), 733–754. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2019.1649316

- Paul, V. A., Knox, L., & Smith, D. M. (1995). Smith, D. M. 1977: Human geography: A welfare approach. London: Edward Arnold. Progress in Human Geography, 19(3), 389–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/030913259501900305

- Peng, Q., & Knaap, G. (2023). When and where do home values increase in response to planned light rail construction? Journal of Planning Education and Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X221133022

- Pojani, D., & Stead, D. (2014). Ideas, interests, and institutions: Explaining Dutch transit-oriented development challenges. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 46(10), 2401–2418. https://doi.org/10.1068/a130169p

- Pojani, D., & Stead, D. (2015). Transit-oriented design in The Netherlands. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 35(2), 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X15573263

- Polski, M. M., & Ostrom, E. (1999). An institutional framework for policy analysis and design. Workshop in political theory and policy analysis, Indiana University. https://ostromworkshop.indiana.edu/pdf/teaching/iad-for-policy-applications.pdf

- Przybylinski, S. (2022). Where is justice in geography? A review of justice theorizing in the discipline. Geography Compass, 16(3), e12615. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12615

- Rawls, J., & Kelly, E. (2001). Justice as fairness: A restatement. Harvard University Press.

- Robeyns, I., & Byskov, M. F. (2021). Capability approach. In E. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/capability-approach/.

- Sandoval, G. F. (2018). Planning the barrio: Ethnic identity and struggles over transit-oriented, development-induced gentrification. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 41(4), 410–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X18793714

- Sen, A. (1995). Inequality reexamined. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0198289286.001.0001

- Shatu, F., Aston, L., Patel, L. B., & Kamruzzaman, M. (2022). Chapter Ten - Transit oriented development: A bibliometric analysis of research. In X. J. Cao, C. Ding, & J. Yang (Eds.), Advances in transport policy and planning (Vol. 9, pp. 231–275). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.atpp.2021.06.001

- Smrke, U., Blenkuš, M., & Sočan, G. (2018). Residential satisfaction questionnaires: A systematic review. Urbani Izziv, 29(2), 67–82. https://doi.org/10.5379/urbani-izziv-en-2018-29-02-001

- Sun, Z., Allan, A., Zou, X., & Scrafton, D. (2022). Scientometric analysis and mapping of transit-oriented development studies. Planning Practice & Research, 37(1), 35–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2021.1920724

- Sung, H., Choi, K., Lee, S., & Cheon, S. (2014). Exploring the impacts of land use by service coverage and station-level accessibility on rail transit ridership. Journal of Transport Geography, 36, 134–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2014.03.013

- Tao, S., Ettema, D., Luo, S., & He, S. (2022). The role of transit accessibility in influencing the activity space and non-work activity participation of different income groups. Journal of Transport and Land Use, 15(1), 375–398. https://doi.org/10.5198/jtlu.2022.2075

- Thomas, R., & Bertolini, L. (2020). Transit-Oriented development: Learning from international case studies. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48470-5

- Thomas, R., Pojani, D., Lenferink, S., Bertolini, L., Stead, D., & van der Krabben, E. (2018). Is transit-oriented development (TOD) an internationally transferable policy concept? Regional Studies, 52(9), 1201–1213. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1428740

- Tong, X., Wang, Y., Chan, E. H. W., & Zhou, Q. (2018). Correlation between transit-oriented development (TOD), land use catchment areas, and local environmental transformation. Sustainability, 10(12), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124622

- Tran, M., & Draeger, C. (2021). A data-driven complex network approach for planning sustainable and inclusive urban mobility hubs and services. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science, 48(9), 2726–2742. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399808320987093

- Trudeau, D. (2018). Integrating social equity in sustainable development practice: Institutional commitments and patient capital. Sustainable Cities and Society, 41, 601–610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2018.05.007

- Tyler, T. R. (2000). Social justice: Outcome and procedure. International Journal of Psychology, 35(2), 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/002075900399411

- Van Wee, B., & Banister, D. (2016). How to write a literature review paper? Transport Reviews, 36(2), 278–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2015.1065456

- Wagner, J. (2013). Measuring performance of public engagement in transportation planning: Three best principles. Transportation Research Record, 2397(1), 38–44. https://doi.org/10.3141/2397-05

- Wang, F., Zheng, Y., Wu, W., & Wang, D. (2022). The travel, equity and wellbeing impacts of transit-oriented development in Global South. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 113, 103512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2022.103512

- Wang, K., & Woo, M. (2017). The relationship between transit rich neighborhoods and transit ridership: Evidence from the decentralization of poverty. Applied Geography, 86, 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2017.07.004

- Wen, P., Zhang, J., & Zhou, S. (2022). Social group differences in influencing factors for Chinese urban residents’ subjective well-being: From the perspective of social stratification. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159409

- Wey, W.-M., Zhang, H., & Chang, Y.-J. (2016). Alternative transit-oriented development evaluation in sustainable built environment planning. Habitat International, 55, 109–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2016.03.003

- Wu, H., Zhai, G., & Chen, W. (2020). Combined rental and transportation affordability under China’s public rental housing system—A case study of Nanjing. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(21), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218771