ABSTRACT

War remains a central feature of global politics and has been a core focus for politics and international relations, history, economics, sociology as well as other cognate disciplines. The analysis of the effects of war has, however, tended to be compartmentalised by sub-disciplines. This article proposes a heuristic framework to map the effects of war in terms of ripple and backwash across a range of interconnected layers of societies. Through this framework, the article then introduces a set of empirically rich and theoretically informed studies from across multiple disciplines which examine the first consequences of the war in Ukraine. Taken together, these studies show that the war has had deep and complex effects affecting human life; human development; economies; values and attitudes; policy and governance; and power distribution and relations around the world. Although broader international public interest in the war may have waned within weeks of the invasion, the effects of the conflict have been deep and continued in many areas, but also differentiated across space and time. Traditional public policy concepts used to frame the effects of “external shocks” such as punctuated equilibrium and critical junctures may overlook such deep-seated and diverse effects, warranting the multidisciplinary lenses used in this volume.

1. Introduction

Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, in an escalation of a conflict that had been continued with varying intensity since 2014 when Russia took control of Crimea and pro-Russia separatist forces in the Donbass region declared their independence. The conflict is rooted in a centuries long struggle for power between great empires and constellations of power (Sakwa Citation2014; Sullivan Citation2022).

The academic and policy communities got it wrong. Few predicted that Russia would invade Ukraine and even less anticipated the latter would hold their ground against initial Russian attack. As the invasion enters its third year, the most immediate and visible consequences have been loss of life and large numbers of refugees from Ukraine. However, given the interconnected structure of the international political, economic, and policy systems, the ramifications of the conflict can be felt well beyond Ukraine.

Much of the recent literature and commentaries have focused on the military and strategic lessons learned from the on-going conflict (Biddle Citation2022; Citation2023; Dijkstra et al. Citation2023). However, there are potentially much wider global consequences for a greater variety of policy areas (Orenstein Citation2023). As Robert Jervis notes, the international system is not only interconnected but also often displays nonlinear relationships and “outcomes cannot be understood by adding together the units or their relations, and many of the results of actions are unintended” (Jervis Citation1997, 6). With the analysis of war usually the preserve of strategic studies and military history, such multifaceted, interconnected and non-linear effects are not always studied so closely – or at least not in a more unified way. Policy studies, moreover, often tends to treat the effects of war as an “external shock” or “punctuated equilibrium” with little further theoretical reflection.

This special issue considers the first consequences of the war, two years on from the full-scale invasion and still ongoing at the time of the publication, aware that these are changing in real time. The articles assembled here provide a diverse range of perspectives on the effects of the war on particular policy areas in Ukraine, across Europe and globally – but also how theoretical concepts such as “exogenous shocks” and “punctuated equilibrium” are used for understanding policy change.

Section 2 provides a brief review of the main literatures which have sought to explore the effects of war. Section 3 provides a timeline and some background to the war in Ukraine. Section 4 considers some of the methodological issues involved in identifying the effects of war. Section 5 then provides a heuristic framework for understanding the interconnected effects of the war. We suggest that the metaphor of the ripple and washback effects of war across multiple layers of society can help capture a fuller picture of the consequences of conflict than the existing terminology. Section 7 then applies this framework to the war in Ukraine using the studies included in this special issue. The final section considers the broad lessons from the conflict and policy recommendations.

2. Existing approaches to studying the effects of war

War (or conflict) has historically been an ever-present feature of human existence, and the use of force an essential component of statecraft (Black Citation2009; Rosen Citation2005). Given the significance of the subject-matter, the study of war remains a central theme in strategic studies and international relations (e.g. Brands Citation2023; Levy Citation2014; Sarkees and Wayman Citation2010; Vasquez Citation2009). Consequently, and perhaps understandably, much of the literature has focused on the causes of wars (Levy Citation1998; Levy and Thompson Citation2010). Scholars have long noted the nonlinear and unpredictable nature of war (Beyerchen Citation1992). They have also pointed its transformative effects. As Carl von Clausewitz (Citation1976, 92) pointed out, “[t]he original political objects can greatly alter during the course of the war and may finally change entirely since they are influenced by events and their probable consequences” (emphasis in original).

Of equal significance, then, are the consequence (or the impact) of wars, which is the focus of this Policy Studies special issue. Wars have the potential to not only alter the parties and “transform the future” of belligerents (Ikle Citation1991, vii) but can also bring about foundational changes to the international system (Gilpin Citation1981, 42–43). As William R. Thompson (Citation1993, 139) pointed out, the literature on the consequences of war is “probably much more extensive than most people realize” and in need of more “ambitious analyses … [that require] to view warfare and the phenomena upon which it impacts as a complex field of interactive structures and processes.” Put differently, the consequences of wars areoften felt beyond simple calculations of material capabilities and properly understanding the full effects in their diversity and complexity requires a multidisciplinary approach.

This is not to say that there has been no literature on the effects of war. Many different disciplinary perspectives have considered – explicitly or implicitly – the question of what the effects of war are. We argue, however, that they have tended to do so in disparate and generally disconnected ways.

Economists have provided considerable analysis of the macroeconomic effects of a conflict across spatial levels: locally, nationally, regionally and internationally. Studies have examined the effects of specific wars such as the Syrian civil war (Kešeljević and Spruk, Citation2023) or the Iraq war (Bilmes and Stiglitz Citation2006). They have also examined the effects of war in general. For instance, Reuven Glick and Alan Taylor (Citation2010) examine bilateral trade relations from 1870 to 1997 and find “large and persistent impacts of wars on trade, and hence on national and global economic welfare” (102; also see, Anderton and Carter Citation2001). Similarly, Vally Koubi (Citation2005) examines the effects of inter and intrastate wars on a sample of countries and finds that the combined prewar, contemporaneous and postwar effects on growth are negative. A “war ruin” school therefore emerged, according to Kang and Meernik (Citation2005), which emphasized that the destruction caused by wars is accompanied by effects on inflation, unproductive resource spending on the military and war debt (Chan Citation1985; Diehl and Goertz Citation1985; Russett Citation1970). By contrast, a “war renewal” school claimed that there can be longer term positive economic effects from war because it can lead to increased efficiency in the economy by reducing the power of rent-seeking special interests, triggering technological innovation, and advancing human capital (Olson Citation1982; Organski and Kugler Citation1980). Early analysis estimated that the invasion of Ukraine by Russia had an economic cost of 1% of global GDP in 2022 (Liadze et al. Citation2023).

Human development studies have considered the impact of the loss of lives and injuries of those directly or indirectly involved in the conflict, as well as the effects on the workforce due to the war mobilization or reorientation of economic activities. The effects of war, terrorism and armed conflict on young children include post-traumatic stress symptoms, behavioural and emotional symptoms, and psychosomatic symptoms (Slone and Mann Citation2016). Exposure to war as a child can have long term adult effects on health (Allais, Fagherazzi, and Mink Citation2021). There are long lasting effects on human capital and educational attainment (Ichino and Winter-Ebmer Citation2004)

Political science has tended to focus on the domestic consequences of war. Electoral political scientists have often considered the effects of war on public opinion. A key concern has been whether war produces “rally around the flag effects” to bolster the support of incumbent leaders – or whether war weariness can contribute towards declining support for governments, including for those governments committed to conflicts far overseas. John Mueller (Citation1970) was the first to develop the concept of the “rally-round-the-flag” with later scholars identifying some of the factors that might shape or mitigate the effect (e.g. Dinesen and Jaeger Citation2013; Murray Citation2017). Kseniya Kizilova and Pippa Norris (Citation2023) considered any rally effects during the first few months of the Ukraine war. They argue that the reason likely to be motivating Putin’s military invasion was an attempt to boost popular support amongst the Russian electorate. They note evidence of a surge in support for Putin following the invasion which persisted longer than is usual in democratic system. However, they question whether this is likely to be sustained as the economic costs of the conflict bite.

A lengthy literature from policy studies, governance and public administration have also considered the effects of war on other policies or systems of governance. These approaches usually treat war as representing a critical juncture which creates a punctuated equilibrium. Punctuated Equilibrium Theory was originally advanced by Frank Baumgartner and Bryan Jones (Citation1993, Citation2005) to explain the policy process in the US. It held that factors such as bureaucratic politics and high decision-making costs can make change difficult to achieve. However, a major “focussing event” such as a natural disaster can cause the policy to be reframed. In this model, the causes of policy change are therefore exogenous to domestic political systems – or to the factors which shape policy during “normal times”. Joly and Richter (Citation2023) have recently argued that that this approach is also useful for studying international policy making and governance. A war that is external to a political system or policy sub-system can cause a punctuated equilibrium within this system. The Ukraine war indeed represents a possible critical juncture for many different policy areas, within and outside Ukraine and Russia (Stockemer Citation2023).

Area Studies have also considered the effects from the perspective of multiple escalating conflicts and simmering disputes. With military use of force now an endemic reality in the Middle East, and the threat of kinetic conflict seemingly more likely across large swathes of Africa and the Indo-Pacific, issues of regional specificity and comparability are of particular concern (Cobbett and Mason Citation2021). In other words, the approach is to consider what can we learn from the Ukraine case when it comes to Gaza, the Red Sea or even Taiwan? Equally, an Area Studies approach considers whether the global impact of the War in Ukraine highlights the increased challenges of containing regional conflict on the one hand, and dealing with the interconnections that are now affected by related political events and decisions taking place within a relatively limited geographical space, on the other (Legrenzi and Lawson Citation2018).

Military and diplomatic historians have long produced rich accounts of war. In particular, the growth of cultural approaches within these fields has demonstrated the potential wide-ranging impact and societal transformation of conflict (See: Addison Citation1975; Lary Citation1994; Mosse Citation1994). For example, the insights that analysis of social and cultural aspects have brought to the historiography of World War demonstrates the benefits of studying war from beyond its traditional parameters (e.g. See: Heathorn Citation2005; Jones Citation2013). Political historians, meanwhile, have noted the consequences for specific leaders or politicians. For example, Tony Blair’s decision to go to war in Iraq had considerable consequences for his popularity amongst the public – but especially amongst his own party. The latter contributed considerably towards shortening his time in office (Buller and James Citation2012). Meanwhile, historical sociologists have taken a macro-social, long durée approach to the consequences of war, analysing the role of war in state building (Mann Citation1988; Tilly Citation1992), an approach often summarized through the “War made states and states made war” slogan.

Given the richness and breadth of existing studies on the consequences of war, there is a risk of unfairly creating a “straw-man model” of the existing literature. Each distinct strand provides important knowledge and understandings. Nonetheless, the analysis of the effects of war tends to be divided into disciplines and sub-disciplines with relatively little conversation between them or integrative efforts. This special issue proposes to bring these different approaches and contributions together, providing an integrative framework to map the multiform consequences of the war Ukraine and offering a more integrated, if necessarily still incomplete view.

3. The war in Ukraine

Having looked at how different disciplines study the consequences of war, we now turn to the conflict in Ukraine. Indeed, the roots of today’s conflict go back to the early 1990s, when Ukraine declared its independence from the Soviet Union. While the Ukrainian economy was still strongly tied to Russia’s, the country began shifting its political focus towards the EU and NATO. This shift culminated in the Orange Revolution of 2004, resulting in the election of pro-Western Viktor Yushchenko as President (Noll Citation2022). In 2013, tensions escalated again when pro-Russia President Viktor Yanukovych declined to endorse plans for closer economic cooperation with the EU, contributing to trigger the “Euromaidan” demonstrations and the establishment of a new government in February 2014 (Walker Citation2023a).

Portraying the protests as a Western-backed “coup”, Russian President Vladimir Putin launched a covert operation in Crimea, justifying it as a rescue mission for the peninsula (Masters Citation2023). Following a disputed referendum, he declared the annexation of Crimea in March 2014 (CPA Citation2024). Conflict soon erupted in the Eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk (the Donbass), where Russia supported separatist forces (Walker Citation2023a). Despite attempts to negotiate a ceasefire through the Minsk Agreements, the conflict in the Eastern part of the country has continued (Walker Citation2023a), resulting in over 14,000 deaths between 2014 and 2021 (OHCHR Citation2022a).

Against this backdrop, on 21st February 2022, Russia recognized the independence of Donetsk and Luhansk and, three days later, confounding most western observer’s expectations, launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, referring to it as a “special military operation”.Footnote1 During the initial weeks, Russia made substantial advances (CIA Factbook Citation2024), yet failed to take Kyiv (Kiev) in the face of robust Ukrainian resistance supported by western allies. In October 2022 Russia declared the annexation of Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia (even though they were not entirely under its control) (Walker Citation2023b). In summer 2022 and June 2023, with the material assistance – both civil and military – of its western allies, Ukraine launched counteroffensives to retake lost territories. Estimates suggest that, as of February 2024, Ukraine has reclaimed more than half of the territories initially seized by Russia (CPA Citation2024; Walker Citation2023b). Simultaneously, however, evidence emerged of Russia having violated international law and committed war crimes, including through summary executions, torture, rape, and the bombing of hospitals (Amnesty International Citation2022; CPA Citation2024; OHCHR Citation2022b).

The war has had a significant impact on Ukraine’s population. Within the initial two years of the conflict, more than 6 million Ukrainians have fled their country, and it is estimated that over 10,000 Ukrainian civilians and approximately 31,000 Ukrainian soldiers were killed.Footnote2 Civilian casualties were especially high at the beginning of the war, with over 4000 civilians killed in March 2022 alone (OHCHR Citation2024).

In Russia, the government announced a “partial mobilisation” of 300,000 reservists in autumn 2022, which led many to leave the country. Estimates suggest that between 500,000 and 1 million Russians fled to neighbouring countries, first of which Kazakhstan and Serbia (The Economist Citation2023). Russian casualties are estimated at 66,000–88,000 in the first two years of the war (The Economist Citation2024). Moreover, as reported by Freedom House (Citation2023), Russia has imposed restrictions on individuals’ rights and liberties since the start of the war in order to restrain dissent, including by criminalizing anti-war protests, arresting and mistreating demonstrators.

The West’s response to the conflict included military assistance to Ukraine, economic support and sanctions against Russia. In the first two years of the war, Ukraine received €253 billion in bilateral contributions (Trebesch et al. Citation2024).Footnote3 Specifically, it received financial aid for €128 billion, humanitarian support for €17 billion, and military contributions for €107 billion. The EU is the largest donor, followed by the United States. Considering bilateral aid by donor countries’ GDP, Eastern European and Scandinavian countries (including Estonia, Denmark, Lithuania, Norway) are the leading donors. On the contrary, over 16,500 sanctions were imposed on Russia by various countries, including the USA, UK and EU (BBC Citation2024). Simultaneously, NATO grew to include Finland in April 2023 and Sweden in March 2024,Footnote4 while Ukraine and Georgia were granted official EU candidate status in June 2022 and December 2023, respectively (Council of the European Union Citation2024). Despite the conflict prompting a unified response by the EU and the West, global condemnation of Russia did not unfold as anticipated, as over forty countries repeatedly abstained or opposed United Nations’ resolutions (Alden Citation2023).

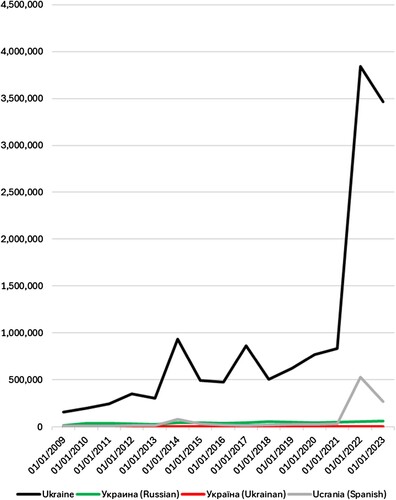

The conflict has captured the world’s attention and risen to the top of the media and political agenda. summarizes the number of news stories in Nexis Advance UK with “Ukraine” in the title in the period from 2009 to the end of 2023. The dataset includes newspapers from around the world. While it may not be complete in coverage and more orientated towards English-speaking UK media, it provides a useful snapshot of coverage of the war outside of Ukraine and Russia. The dataset does include non-English sources and the Russian, Ukrainian and Spanish translations are therefore also included (“Ukraine” has the same translation in French and German). shows an incomparable increase in the volume of news stories on the country in the wake of the invasion. Although there was already a spike in 2014 when the conflict was ongoing, the media interest since 2022 has been unprecedented. Yet, it is also notable that media coverage has declined in 2023, even though the drop appears relatively small.

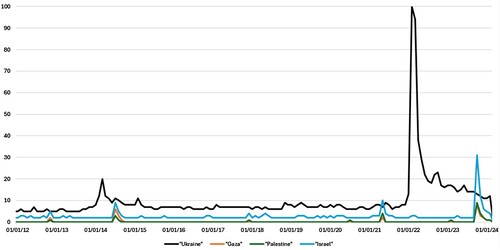

By contrast, citizen’s interest has faded away relatively quickly. uses Google Trends data of searches for “Ukraine”. It shows very little interest in the conflict in 2014 but a major surge in the initial period of the invasion. This unprecedented interest has dropped substantially over time. The figure includes searches for “Gaza” “Palestine” and “Israel” as comparisons. While international interest may have shifted to other conflicts or issues, there was not a simple switch from Ukraine to Gaza, however. In fact, interest for Ukraine had already substantially dropped away before the attack against Israel and the Israeli military invasion of Gaza in response. However, as this volume shows, despite shifting international attention the effects of the war in Ukraine have continued to be substantial.

4. Methodological issues in tracing the effects of war

In trying to map out the consequences of the war we encounter several methodological challenges.

The first issue is the danger of presentism. The war is ongoing at the time of writing. It is therefore impossible to know when it might end and what the outcome will be. The effects of wars, as the literature above notes, often extend in the medium and long term. There are therefore dangers in declaring too soon what the consequences have been. And yet, there are also dangers in not examining the proximate effects of the war. It undoubtedly had huge humanitarian, economic and political impacts which require policies to address them. The effects of wars cannot be left for future historians; social scientists have an active role to play in documenting and analysing consequences as they unfold. Conscious of the practical need to bound the analysis, we refer to the first effects of the war in Ukraine to designate those which occurred following the invasion of Russia in February 2022 up until the end of 2023. This covers a period of roughly two years. We are well aware that further mid to long-term effects might follow – and also that there were prior effects as the conflict predates February 2022.

A second issue is the danger of assumed causality. Wars are complex in nature and uncertainty is running high – the proverbial “fog of war”. It is therefore difficult to trace causality with a high degree of certainty. Counterfactuals are not readily available. For example, although there was a decline in some economic indicators – how do we know what would have happened anyway? This problem is well understood and approached differently by different disciplines and social science research traditions. For example, quantitative researchers might develop synthetic controls (Costalli, Moretti, and Pischedda Citation2017). Qualitative comparative historical sociologists tend to emphasize the value of process tracing (Mahoney Citation2015). Our approach is to be neutral in terms of which approach is better suited. Papers collected in this special issue were independently reviewed by external academics on their own terms. We welcomed papers from all research traditions.

A third issue is the temptation and danger of neat distinctions and parsimony. The special issue seeks to go beyond the traditional narrow focus on geopolitics and stress the complex, interrelated and differentiated effects of war. This approach values research which is place and time specific. War is “messy” and uncertain, and its effects diverse and diffuse – with different levels of intensity – around the world. There is danger in collapsing the complex effects into a simple narrative, running the risk of losing specificity and precision. At the same time, there is also value in developing a typology of the effects of war – however tentative and imperfect. Typologies do help provide clarity for the reader – be they academics or policy makers – to map a complex phenomenon and are therefore used by both quantitative and qualitative researchers (Collier, Laporte, and Seawright Citation2008). Without some theoretical parsimony, it can be difficult for a complex landscape to be comprehended. There is also a danger that theoretical concepts, frameworks and narratives are used implicitly when not explicitly laid out to the reader. By developing a basic typology of the effects of war, we seek to provide clarity while making our assumptions explicit.

A fourth methodological challenge is geo-graphical coverage. It is impossible to truly survey the effects around the world in every country. There are limits on the number of articles which can be included in this special issue, the volume of researchers that can contribute and the number of policy areas which can be included. There are also global inequalities and disparities in higher education university systems – in terms of resources, language, access to journals etc – which might lean towards some positions and policy areas being more explored than others. Those most affected and particularly well positioned to comment on the effects of the war are likely to be researchers from within Ukraine. However, for them war is a lived experience. They may therefore not be able or willing to write academic research articles about a conflict in which they are directly or indirectly involved and which is a direct concern with immediate pressures. This special issue sought to address these challenges by making an open call across disciplines and to include as many perspectives as possible. The special issue is therefore much longer and more substantial than traditional volumes in this journal. We were delighted to be able to include research from Ukrainian researchers, while also aware that the volume could and should include more.

A fifth and final issue is the positionality of the special issue and editorial team with respect to the war. Research papers may adopt a normative position – explicitly or implicitly – on the conflict. We did not filter or discourage submissions of any form – either in terms of normative positioning or location of the submissions. As it were, we received no submission from Russian academics or from academics supporting the invasion.

5. The ripple effects of war

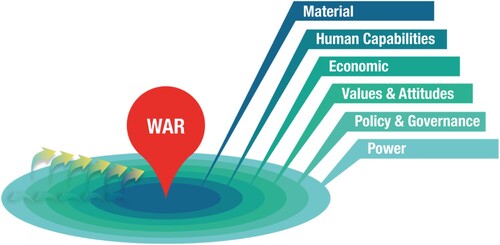

To help provide some order to the special issue – and our understanding of the effects of war – this section introduces a typological framework. It aims to transcend the existing approaches surveyed above – which tend to focus on one dimension only of war. Here, we emphasize how war can affect different layers of society – and how they interact. Our framework is set out in . The figure is centred on the conflict, coloured in red. It causes ripple effects across the following areas: direct human and material destructions; human capabilities; economies; values and attitudes; policy and governance; and domestic and international power relations.

5.1. Six ripple effects

The primary effects are the immediate and direct material effects of war. The strategic decision to invade, to deploy troops and attack causes damage. First and foremost, this includes the loss of life and physical injuries suffered by military personnel and civilians, which have enduring effects. This damage includes the destruction of material infrastructures, such as buildings, means of communication and military facilities and equipment. Decisions to attack can also lead to material damage to the aggressor because of defence and counterattack.

The material effects then affect human opportunities to realize their central capabilities. Central human capabilities, Martha Nussbaum (Citation2011) argued, include life, bodily health, sense imagination and thought and control over one’s environment. War conditions can immediately affect these. Educational resources may be unavailable while healthcare provisions may be destroyed. Job opportunities which provide income may no longer be available. Injuries may make humans unable to do previous jobs.

War has broader economic consequences which can also undermine human opportunities. Economic supply chains may be affected as a result of the destruction of infrastructures and resources. War mobilization may affect the workforce and economic production. Actors in the economy may also act strategically to deploy resources elsewhere, to support the war effort or because the war has affected incentive structures or decide to cease production altogether because of expected losses. These effects can be local to geographical areas engulfed in conflict but also cause ripple effects to a wider regional area and to the global economy. Production, consumption, trade, inflation, growth and employment patterns may all be affected.

In this new environment humans will rethink values, beliefs and attitudes. There might be shifts in identity as new enemies and perceptions of the self and “others” are reformed or strengthened. Those within the conflict zone may see their feelings and values towards others – both friends and enemies – hardened or reshaped. Those outside of the immediate conflict zone may also develop new or reframed perceptions of the aggressors and those under attack. Attitudes might shift in favour or against specific countries and populations.

The next layer is governance and policy change. At a governmental level, the countries at war redeploy attention and resources towards the conflict – and this also affects governance as well as other policy areas. Powers may be centralized around the executive to deal with the emergency, to the detriment of other institutions including the Parliament. Democratic backsliding may therefore occur with reduced accountability of decisions. The economy may be governed in an altered way, with new taxes for example, to fund military efforts. Other policies might be scrapped altogether in the face of the emergency – or reorientated towards the conflict. Governments outside of the immediate conflict area may shift resources to support or oppose of the parties to the conflict: aid might be provided in support the war effort and humanitarian support can be offered to those fleeing the war. However, third party government may also accommodate policy to respond to indirect externalities of the war, such as economic shocks, supply chain disruptions or inflation. These policy changes may, in turn, affect other polities, in a coordinated manner or not.

All of these connected ranges of effects feed into the final domain: power relations and relationships. There might be winners and losers of the war at the domestic and international levels. The relationships between states, organizations and social classes may change because of the conflict and shifts in the other layers of effects. Some partnerships and ways of working may come to an end – with new relations and hierarchies being formed.

5.2. Washback effects of the ripples

The effects of war and conflict are marked in with a greenarrow, from the most proximate to the most distant effects. The effects of the war do not occur in a linear way, however. Each layer is connected to all the others – as they are all part of interconnected human relations. They can create ripples onto each other. Yet not all are necessarily affected. For example, material damage and loss of life in a conflict could occur – with very limited change in values, attitudes or policies in third party states. The extent to which there are ripple effects might be contingent on media reporting and broader power relations for instance, as the wider world may pay little attention. There is therefore a need to examine the nature and strength of the waves resulting from any given conflict.

Developments in the layers identified above will also feedback into shaping the conflict with washback effects. The policies of states that are third party to the conflict may, for example, directly shape the conflict. Those involved in the war may also be mindful of broader international public opinion. There will therefore be fluid and complex interactions between the six layers identified above.

6. The ripple effects of the war in Ukraine

We now turn to a presentation of the studies included in this special issue, introduced using the framework sketched out above. While this framework does not fully do justice to the richness of the contributions, it provides a useful way to organize them and their contributions.

6.1. Material effects

Foremost, the material effects were the loss of life to those involved, directly or indirectly in the conflict. The UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine (HRMMU) has claimed that it has verified 10,000 civilian deaths and nearly 20,000 civilian injuries during the first two years of the conflict (OHCHR Citation2024). This includes 587 killed and 1298 injured children. In December 2023 a declassified US intelligence report suggested that roughly 315,000 people had died or were injured (Landay Citation2023). HRMMU have also reported heavy damage to infrastructure including 59 destroyed medical facilities and 236 destroyed educational facilities. 406 medical facilities and 836 educational facilities were damaged in the conflict (OHCHR Citation2024).

6.2. Human capabilities

The broader effects of the war on human capabilities are assessed directly by Balazs Égert and Christine de la Maisonneuve (Citation2024). They evaluate the likely effects on human capital by examining how the quality and quantity of education and adult skills would be affected the war. They argue that the effects on individuals could last lifetimes. Both Marie Jelínková, Michal Plaček, and František Ochrana (Citation2024) and Matilde Rosina (Citation2024) analyse the effects of the large volume of refugees fleeing Ukraine. This has immediate consequences for those involved but also longer-term consequences. Égert and de la Maisonneuve (Citation2024) point out that there is broad evidence that refugee children are less likely to attend school and hardly any refugees attend university.

6.3. Economic effects

The economic effects have been both national and international. In Ukraine, Égert and de la Maisonneuve (Citation2024) argue that the longer term macro-economic effect of the war includes decline in productivity. They estimate that losses in long-run aggregate productivity could be roughly 7% by 2035, with the negative effects taking decades to remedy. Vladyslav Teremetskyi et al. (Citation2024) detail how the war had detrimental effects on the economy in Ukraine. They show in particular that there was a drastic reduction in the tax revenue to the state budget because of the impact of the war on economic activity.

Ukraine is an important grain producer and exporter of crops with 42% of global sunflower oil exports being produced in Ukraine before the war (Hegarty Citation2022). Hamid El Bilali and Tarek Ben Hassen (Citation2024) sets out how the war has impacted food production dramatically on a global scale, affecting all food security dimensions: availability, access, utilization, and stability.

The war has also substantially increased global economic uncertainties, as Whelsy Boungou and Alhonita Yatié (Citation2024) show. This negatively affected the performance of global financial markets and led to higher commodity prices. An increase of uncertainty of 1% led to an increase in raw material prices of almost 3%. They find that the responses to war-induced uncertainties were stronger in Europe and America than elsewhere. The negative shocks tended to be smaller the longer the war continued.

The Russia-Ukraine war had varying effects on the currencies of non-Eurozone countries, as Mahmut Zeki Akarsu and Orkideh Gharehgozli (Citation2024) demonstrate. Poland, Hungary, and Sweden experienced significant impacts, while the Czech Republic and Romania remained relatively stable. They also highlight the stability of the Euro as a reserve currency, which attracted investors during the crisis and protected participating economies from currency fluctuations.

The war also increased energy costs and the distribution of energy supplies, as noted by Moniek de Jong (Citation2024) and Li-Chen Sim (Citation2024). As de Jong shows, the war triggered a gas supply and price shock for the EU which, through the greater use of LNG (including from the US), market and consumer responses to higher prices and – to a lesser degree – a new set of policy measures, has become more diversified and less gas intensive but also more import dependent on a new set of suppliers.

6.4. Values, beliefs and attitudes

Wars can trigger major shifts in values, beliefs and public opinion. Aaron Brantly (Citation2024) argues that the war has caused Ukraine to unify behind a common national idea and identity. This unification and the creation of a new national identity have profound implications for post-war Ukraine. Matthias Mader (Citation2024) examines how the war has changed attitudes in Europe towards Russia. He finds that there has been an increased perceptions of Russia as a threat and stronger support for collective defence, but also some significant variation in the size of these changes across countries. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine strengthened Europeans’ preference for NATO rather than EU support. It also changed citizens’ general willingness to defend other European countries.

The values and beliefs of policy makers, as well as citizens, are also important in shaping the war. A key influence on these would be how Ukrainian leaders would appeal to the wider world. Yuliia Kurnyshova (Citation2024) examines how Ukraine has sought to influence international partners by narrating the conflict. It sought to draw attention to the numerous insecurities in energy supply, environmental and nuclear hazards, and disruption of food transportation. Ukraine therefore sought to present the strategic narrative of the war as an intrinsic part of European security governance.

6.5. Governance and policy

Policy changes followed as a result of the war in neighbouring states to Ukraine and around the world. Security and defence policy has been the most obvious to be affected by the war. Prior to the war, the EU had invested greater efforts to boost defence and security co-operation between member states. Jonata Anicetti (Citation2024) evaluates the impact of the war in Ukraine on EU defence cooperation by exploring three level of analysis: arms collaboration, arms procurement, and offsets. He argues that the Russo-Ukrainian war has negatively impacted EU defence cooperation across the board. Member states have been investing less in EU collaborative defence projects, have been buying more non-EU weapons, and demanding more offsets.

Ramūnas Vilpišauskas (Citation2024) examines the effect of the conflict in Ukraine on Lithuania's cyber security policy, taking a longer temporal perspective. Despite increasing cyberattacks in the late 2000s, policy change was slow. It was only after the 2014 Russo-Ukrainian war that the conditions emerged for cybersecurity policy to be transformed. In this sense, while the 2022 events had limited further impact, being mainly visible at the operational level, developments in Lithuania's cybersecurity policy are strictly related to security developments in Ukraine.

Foreign policy, more generally, has also been redefined by the war. Ryhor Nizhnikau and Arkady Moshes (Citation2024) examine how the war has shaped the EU’s Eastern Neighbourhood Policy, a policy that covers the EU’s relations – including technical and economic cooperation, as well as support for good governance and democratic reforms – with its neighbouring countries to the east.Footnote5 The EU has sought to build partnerships with these countries mainly through political association, economic integration and pressure for reforms, but the war has created an acute need for adding a geopolitical and security dimension to the policy. It has meant an urgent reassessment of security challenges and the development of new objectives and instruments to deter Moscow and support partners in the region. This, they argue, raises questions as to whether the EU can balance values, including on good governance and democratic reforms, with security interests.

Migration policy is also an area that was affected. Jelínková, Plaček, and Ochrana (Citation2024) outline how the war led to a major influx of refugees in the Czech Republic. This created the opportunity and need for policy change. The war therefore led to fundamental changes in Czech migrant-integration policy. However, this change can only be short-term, as a critical juncture did not occur. Relatedly, Rosina (Citation2024) argues that the war led to an unprecedented response by the EU concerning migration as the Union adopted for the first time a “temporary protection” mechanism for Ukrainians, while also suspending its visa facilitation agreement with Russia.

At the level of global governance, the internal structure of international policy networks also stands to be affected. Anna Ivanova and Paul Theirs (Citation2024) show how the stability of international epistemic communities has been disrupted by the war. They analyse case studies of three epistemic communities: the European Space Agency (ESA), the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), and the Arctic Council (AC). They find evidence of policy communities changing and adapting; but also ceasing to exist in times of disruption.

6.6. Power relations and relationships

Power relations and relationships have also shifted as a result of the conflict. In Europe, Nizhnikau and Moshes (Citation2024) argue that the war has made the “post-Soviet space” conceptual framework redundant and created a new regional fragmentation along geopolitical fault lines. Anicetti (Citation2024)’s analysis claims that there was less EU bloc defence co-ordination. By contrast, Rosina (Citation2024) argues that the war has also prompted the EU to utilize migration measures as tools for foreign policy and soft power considerations, reminiscent of Cold War images of migration being employed to undermine opposing regimes. A more proactive EU foreign policy therefore had potential to shift power relations in Europe and beyond.

How did geo-political relations shift between states and across regions, beyond Europe? Angela Pennisi di Floristella and Xuechen Chen (Citation2024) examine China's security narrative by analysing the country's position on the Ukraine Conflict. They argue that China has maintained a dual-track approach by echoing Russia's position on the conflict but also stopping short of fully supporting Moscow. Chirayu Thakkar (Citation2024) examines India's position of neutrality (or strategic autonomy) in foreign policy, particularly relating to the Ukraine Conflict, and argues that it should broadly support US strategic objectives.

Russia cut off gas supplies to Europe in response to European sanctions. As de Jong (Citation2024), argues the war has led the EU to become more diversified, less gas intensive, but also more import dependent, with gas imports coming from new suppliers, including the US and the Middle East. While the war has reshaped the European energy landscape, Li-Chen Sim (Citation2024) argues that, with regards to the Gulf countries and Asia, the war has accelerated pre-existing trends rather than upset them. It has led to Russia redirecting energy flows to Asia because European states banned the import of Russian seaborne crude and petroleum products. This has reinforced competition between Russian and Gulf energy exporters on Asian markets, the Gulf states remaining as the dominant oil and gas suppliers for the region. The war also led to a re-calibration of energy relations between Russia and specific Asian countries, which may impact the Gulf states. The Russo-India relation may have been altered as India increasingly buys Russian oil. Japan, a significant purchaser of Russian gas, coal and oil, meanwhile may have turned away from Russia.

The effects of the war for Japan are explored further by Paul O’Shea and Sebastian Maslow (Citation2024). They argue that the war was utilized by Japan's conservative elite to consolidate the US-Japan Alliance and West-Japan alignment, and that it has accelerated Japan's transformation towards becoming a fully-fledged “normal nation”.

7. Conclusions

The effects of war have been analysed by many separate disciplines and approaches, with each bringing specific and important contributions. This volume has undertaken a cross-disciplinary approach to bring together findings about the effects of war and their interconnections. This article has proposed a heuristic typology in “six ripples” to frame the analysis, map out the effects and introduce the research articles in the special issue. Several general lessons emerge from the theoretical and empirical material and studies in this volume.

Firstly, the ripple effects of war appear much deeper if the analysis adopts the synoptic lenses we propose. The increased specialization of academia encourages the examination of policy effects in discrete areas and smaller pieces, which can cause some effects to fall below the radar of researchers and policy makers alike. By contrast, using multiple tools from across different disciplines can enable a richer and deeper analysis. The punctuated equilibrium metaphor, widely used in the policy sciences, suggests that war can bring sudden and dramatic change followed by a new period of continuity, consistency and stability. The typology used in this article, by contrast, encourages the analysis of several distinct but interconnected layers: material, human development, economic, values and attitudes, governance and policy and power relations. Each has the potential to generate wash back effects which could be immediate – but also last over several years or decades. To fully grasp these effects and interactions, the temporal period of study would therefore need to be much longer. It is notable that public interest in the conflict has declined globally relatively quickly over time. An awareness of the full range of ongoing effects may not be immediately obvious to citizens. The same could be said of academics.

Secondly, the ripple effects of war are nuanced and complex. They are not only more interconnected in the contemporary globalized world but can also be felt at different levels – nationally, regionally and globally. But the weight of the impact can be varied across levels and layers and often cannot be felt at the same frequency. As such, a single narrative about the effects of the war is unlikely to capture the effects in full. Detailed studies using a range of methodologies, disciplinary approaches are needed to capture this complexity. However, there is value in aggregating these studies. Moreover, the case of the war in Ukraine puts in sharp relief that war and major issues of global politics today can influence every corner of the international system in different ways. This not only shows how interconnected our world has become but also the changing of the very nature of conflicts in the twenty-first century (Strachan Citation2014).

Third, agency matters in mitigating the consequences of war and the articles in this volume also make important policy recommendations for responding to the effects of war. For example, the tragic effects on human life can be moderated through humanitarian support packages. Support for refugees and reinvestment in infrastructure can reduce the longer-term effects. Reformed tax policies can promote economic recovery. Agency comes into play because policy makers can take forward these proposals in Ukraine. There are also opportunities for policy learning for other ongoing or possible conflicts. Mitigation policies can therefore be put in place in advance and activated in the event of conflict. Above all, war is an act of agency and choice itself. It is a decision made by political leaders who decide to launch invasions. They are therefore ultimately culpable for the effects of war.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Pierre Bocquillon

Pierre Bocquillon Lecturer in EU Politics and Policy at the University of East Anglia. He is a scholar of of EU and comparative European Politics, whose research focuses in particular on the politics and policies of energy and climate change.

Suzanne Doyle

Suzanne Doyle Lecturer in International Relations at the University of East Anglia. Her research interests include nuclear history, transatlantic relations, US and British defence policy and security studies.

Toby S. James

Toby S. James Professor of Politics and Public Policy at the University of East Anglia. He is also Distinguished Fellow and Adjunct Professor at Queens University, and co-Director of the Electoral Integrity Project. His research focuses on democracy, elections and the policy process.

Ra Mason

Ra Mason Sasakawa Associate Professor of International Relations and Japanese Foreign Policy at the University of East Anglia. He is author/co-author of Japan’s Relations with North Korea and the Recalibration of Risk, Regional Risk and Security in Japan, and Risk State. Ra’s research focuses on Okinawa and the security of the East China Sea.

Soul Park

Soul Park Lecturer in International Relations at the University of East Anglia. His research interests include international security and foreign policy analysis in the Indo-Pacific.

Matilde Rosina

Matilde Rosina Lecturer in Global Challenges at Brunel University London and Visiting Fellow at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Her research focuses on migration policy and politics in Europe.

Notes

1 See: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/world-europe-60470900 and http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/67843, last accessed 27/2/2024.

2 See: https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine, OHCHR (Citation2024), and https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/feb/25/zelenskiy-puts-figure-on-ukrainian-soldiers-killed-for-first-time-at-31000, last accessed 27/2/2024.

3 Data refers to financial, humanitarian and military commitments by 41 countries, between 24 January 2022 and 15 January 2024, as reported by the Ukraine Support Tracker (Trebesch et al. Citation2024).

4 See https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_49212.htm, last accessed 19/3/2024.

5 The Eastern Neighbourhood Policy covers a range of countries, including Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine.

References

- Addison, Paul. 1975. The Road to 1945: British Politics and the Second World War. London: Cape.

- Akarsu, Mahmut Zeki, and Orkideh Gharehgozli. 2024. “The Impact of the Russia-Ukraine War on European Union Currencies: A High-Frequency Analysis.” Policy Studies 45 (3-4): 353–376.

- Alden, Chris. 2023. “The International System in the Shadow of the Russian War in Ukraine.” LSE Public Policy Review 3 (1): 16, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.31389/lseppr.96.

- Allais, O., G. Fagherazzi, and J. Mink. 2021. “The Long-run Effects of War on Health: Evidence from World War II in France.” Social Science & Medicine 276: 113812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113812.

- Amnesty International. 2022. “Ukraine 2022.” Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.amnesty.org/en/location/europe-and-central-asia/ukraine/report-ukraine/.

- Anderton, Charles H., and John R. Carter. 2001. “The Impact of War on Trade: An Interrupted Times-Series Study.” Journal of Peace Research 38 (4): 445–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343301038004003.

- Anicetti, Jonata. 2024. “EU Arms Collaboration and Procurement: The Impact of the War in Ukraine.” Policy Studies 45 (3-4): 443–466.

- Baumgartner, Frank R., and Bryan D. Jones. 1993. Agendas and Instability in American Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- BBC. 2024. “What are the Sanctions on Russia and Have They Affected its Economy?” February 23, 2024. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-60125659.

- Beyerchen, Alan. 1992. “Clausewitz, Nonlinearity, and the Unpredictability of War.” International Security 17 (3): 59–90. https://doi.org/10.2307/2539130.

- Biddle, Stephen D. 2022. “Ukraine and the Future of Offensive Maneuver.” War on the Rocks. November 22. https://warontherocks.com/2022/11/ukraine-and-the-future-of-offensive-maneuver/.

- Biddle, Stephen D. 2023. “Back in the Trenches: Why New Technology Hasn’t Revolutionized Warfare in Ukraine.” Foreign Affairs 102 (5): 153–164.

- Bilmes, Linda, and Joseph E. Stiglitz. 2006. The Economic Costs of the Iraq War: An Appraisal Three Years After the Beginning of the Conflict. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Black, Jeremy. 2009. War: A Short History. London: Continuum.

- Boungou, Whelsy, and Alhonita Yatié. 2024. “Uncertainty, Stock and Commodity Prices During the Ukraine-Russia War.” Policy Studies 45 (3-4): 336–352.

- Brands, Hal, ed. 2023. The New Makers of Modern Strategy: From the Ancient World to the Digital Age. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Brantly, Aaron F. 2024. “Forged in the Fires of War: The Rise of a New Ukrainian Identity.” Policy Studies 45 (3-4): 377–401.

- Buller, Jim, and Toby S. James. 2012. “Statecraft and the Assessment of National Political Leaders: The Case of New Labour and Tony Blair.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 14: 534–555. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-856X.2011.00471.x.

- Chan, Steve. 1985. “The Impact of Defense Spending on Economic Performance: A Survey of Evidence and Problems.” Orbis 29 (2): 403–434.

- CIA Factbook. 2024. “Ukraine.” Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/ukraine/.

- Cobbett, Elizabeth, and Ra Mason. 2021. “Djiboutian Sovereignty: Worlding Global Security Networks.” International Affairs 97 (6): 1767–1784. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiab181.

- Collier, D., J. Laporte, and J. Seawright. 2008. “Typologies: Forming Concepts and Creating Categorical Variables.” In Oxford Handbook of Political Methodology, edited by J. M. Box-Steffensmeier, H. E. Brady, and D. Collier, 152–173. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Costalli, S., L. Moretti, and C. Pischedda. 2017. “The Economic Costs of Civil War: Synthetic Counterfactual Evidence and the Effects of Ethnic Fractionalization.” Journal of Peace Research 54 (1): 80–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343316675200.

- Council of the European Union. 2024. “EU Enlargement Policy.” Accessed March 19, 2024. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/enlargement/#Candidates.

- CPA (Centre for Preventive Action). 2024. “War in Ukraine.” Council on Foreign Relations, Global Conflict Tracker, February 9, 2024. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/conflict-ukraine.

- de Jong, Moniek. 2024. “Wind of Change: The Impact of REPowerEU Policy Reforms on Gas Security.” Policy Studies 45 (3-4): 614–632.

- Diehl, Paul, and Gary Goertz. 1985. “Trends in Military Allocation Since 1816: What Goes Up Does Not Always Come Down.” Armed Forces & Society 12 (1): 134–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095327X8501200107.

- Dijkstra, Hyllke, Myriam Dunn Cavelty, Nicole Jenne, and Yf Reykers. 2023. “What We Got Wrong: The War Against Ukraine and Security Studies.” Contemporary Security Policy 44 (4): 494–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2023.2261298.

- Dinesen, P. T., and M. M. Jaeger. 2013. “The Effect of Terror on Institutional Trust: New Evidence from the 3/11 Madrid Terrorist Attack.” Political Psychology 34 (6): 917–926. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12025.

- The Economist. 2023. “Russians Have Emigrated in Huge Numbers since the War in Ukraine.” August 23, 2023. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2023/08/23/russians-have-emigrated-in-huge-numbers-since-the-war-in-ukraine.

- The Economist. 2024. “How Many Soldiers Have Died in Ukraine?” February 24, 2024. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2024/02/24/how-many-russian-soldiers-have-died-in-ukraine.

- Égert, Balázs, and Christine de la Maisonneuve. 2024. “The Impact of the War on Human Capital and Productivity in Ukraine.” Policy Studies 45 (3-4): 282–292.

- El Bilali, Hamid, and Tarek Ben Hassen. 2024. “Disrupted Harvests: How the Conflict in Ukraine Influence Global Food Systems – A Systematic Review.” Policy Studies 45 (3-4): 310–335.

- Freedom House. 2023. “Freedom in the World 2023: Russia.” Accessed March 15, 2024. https://freedomhouse.org/country/russia/freedom-world/2023.

- Gilpin, Robert. 1981. War and Change in World Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Glick, Reuven, and Taylor M. Alan. 2010. “Collateral Damage: Trade Disruption and the Economic Impact of War.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 92 (1): 102–127.

- Heathorn, Stephen. 2005. “The Mnemonic Turn in the Cultural Historiography of Britain’s Great War.” The Historical Journal 48 (4): 1103–1124. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X05004930.

- Hegarty, Stephanie. 2022. “How Can Ukraine Export its Harvest to the World?” BBC, May 22.

- Ichino, Andrea, and Rudolf Winter-Ebmer. 2004. “The Long-Run Educational Cost of World War II.” Journal of Labor Economics 22 (1): 57–87. https://doi.org/10.1086/380403.

- Iklé, Fred C. 1991. Every War Must End. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Ivanova, Anna, and Paul Theirs. 2024. “Conflict Disruptions of Epistemic Communities: Initial Lessons from the Impact of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine.” Policy Studies 45 (3-4): 551–572.

- Jelínková, Marie, Michal Plaček, and František Ochrana. 2024. “The Arrival of Ukrainian Refugees as an Opportunity to Advance Migrant Integration Policy.” Policy Studies 45 (3-4): 507–531.

- Jervis, Robert. 1997. System Effects: Complexity in Political and Social Life. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Joly, Jeroen, and Friederike Richter. 2023. “The Calm Before the Storm: A Punctuated Equilibrium Theory of International Politics.” Policy Studies Journal 51 (2): 265–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12478.

- Jones, Heather. 2013. “As the Centenary Approaches: The Regeneration of First World War Historiography.” The Historical Journal 56 (3): 857–878. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X13000216.

- Jones, Bryan D., and Frank R. Baumgartner. 2005. The Politics of Attention: How Government Prioritizes Problems. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Kang, Seonjou, and James Meernik. 2005. “Civil War Destruction and the Prospects for Economic Growth.” The Journal of Politics 67: 88–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2005.00309.x.

- Kešeljević, Aleksandar, and Rok Spruk. 2023. Estimating the Effects of Syrian Civil War. Empirical Economics.

- Kizilova, Kseniya, and Pippa Norris. 2023. ““Rally Around the Flag” Effects in the Russian–Ukrainian War.” European Political Science, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-023-00450-9.

- Koubi, Vally. 2005. “War and Economic Performance.” Journal of Peace Research 42: 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343305049667.

- Kurnyshova, Yuliia. 2024. “Chains of Insecurities: Constructing Ukraine’s Agency in Times of War.” Policy Studies 45 (3-4): 423–442.

- Landay, Jonathan. 2023. “U.S. Intelligence Assesses Ukraine War has Cost Russia 315,000 Casualties –Source.” Reuters, December 12, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/world/us-intelligence-assesses-ukraine-war-has-cost-russia-315000-casualties-source-2023-12-12.

- Lary, Diana. 1994. The Chinese People at War: Human Suffering and Social Transformation, 1937–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Legrenzi, Matteo, and Fred Lawson. 2018. “Regional Security Complexes and Organizations.” In The Oxford Handbook of International Security, edited by Alexandra Gheciu, and William Wohlforth, 683–696. Oxford: Routledge.

- Levy, Jack. 1998. “The Causes of War and the Conditions of Peace.” Annual Review of Political Science 1: 139–165. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.1.1.139.

- Levy, Jack S. 2014. War in the Modern Great Power System 1495–1975. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

- Levy, Jack S., and William R. Thompson. 2010. Causes of War. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Liadze, Iana, Corrado Macchiarelli, Paul Mortimer-Lee, and Patricia Sanchez Juanino. 2023. “Economic Costs of the Russia-Ukraine War.” The World Economy 46: 874–886. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.13336.

- Mader, Matthias. 2024. “Increased Support for Collective Defence in Times of Threat: European Public Opinion Before and After Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine.” Policy Studies 45 (3-4): 402–422.

- Mahoney, J. 2015. “Process Tracing and Historical Explanation.” Security Studies 24 (2): 200–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2015.1036610.

- Mann, Michael. 1988. States, War & Capitalism. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Masters, Jonathan. 2023. “Ukraine: Conflict at the Crossroads of Europe and Russia.” Council on Foreign Relations, February 14, 2023. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/ukraine-conflict-crossroads-europe-and-russia#chapter-title-0-4.

- Mosse, George L. 1994. Fallen Soldiers: Reshaping the Memory of the World Wars. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mueller, John E. 1970. “Presidential Popularity from Truman to Johnson.” American Political Science Review 64 (1): 18–34.

- Murray, S. 2017. “The “Rally-‘Round-the-Flag” Phenomenon and the Diversionary Use of Force.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Nizhnikau, Ryhor, and Arkady Moshes. 2024. “The War in Ukraine, the EU’s Geopolitical Awakening and Implications for the “Contested Neighbourhood””. Policy Studies 45 (3-4): 489–506.

- Noll, Andreas. 2022. “What You Need to Know about the Ukraine-Russia Crisis.” DW, February 2, 2022, Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.dw.com/en/how-the-ukraine-russia-crisis-reached-a-tipping-point/a-60802626.

- Nussbaum, Martha C. 2011. Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- OHCHR (Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights). 2022a. “Conflict-related Civilian Casualties in Ukraine.” January 27, 2022. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://ukraine.un.org/sites/default/files/2022-02/Conflict-related%20civilian%20casualties%20as%20of%2031%20December%202021%20%28rev%2027%20January%202022%29%20corr%20EN_0.pdf.

- OHCHR (Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights). 2022b. “UN Commission Concludes that War Crimes Have Been Committed in Ukraine, Expresses Concern about Suffering of Civilians.” September 23, 2022, https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2022/10/un-commission-concludes-war-crimes-have-been-committed-ukraine-expresses, last accessed 27/2/2024.

- OHCHR (Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights). 2024. “Two-Year Update. Protection of Civilians: Impact of Hostilities on Civilians since 24 February 2022.” Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/2024-02/two-year-update-protection-civilians-impact-hostilities-civilians-24.pdf.

- Olson, Mancur. 1982. The Rise and Decline of Nations. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Orenstein, M. A. 2023. “The European Union’s Transformation After Russia’s Attack on Ukraine.” Journal of European Integration 45 (3): 333–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2023.2183393.

- Organski, A. F. K., and Jacek Kugler. 1980. The War Ledger. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- O’Shea, Paul, and Sebastian Maslow. 2024. “Rethinking Change in Japan's Security Policy: Punctuated Equilibrium Theory and Japan's Response to the Russian Invasion of Ukraine.” Policy Studies 45 (3-4): 653–676.

- Pennisi di Floristella, Angela, and Xuechen Chen. 2024. “Strategic Narratives of Russia’s War in Ukraine: Perspectives from China.” Policy Studies 45 (3-4): 573–594.

- Rosen, Stephen Peter. 2005. War and Human Nature. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Rosina, Matilde. 2024. “Migration and Soft Power: The EU’s Visa and Refugee Policy Response to the War in Ukraine.” Policy Studies 45 (3-4): 532–550.

- Russett, Bruce. 1970. What Price Vigilance? The Burdens of National Defense. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Sakwa, Richard. 2014. Frontline Ukraine: Crisis in the Borderlands. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Sarkees, Meredith R., and Frank Wayman. 2010. Resort to War 1816–2007. Washington: CQ Publishing.

- Sim, Li-Chen. 2024. “The Arab Gulf States in the Asian Energy Market: Is the Russia-Ukraine War a Game Changer?” Policy Studies 45 (3-4): 633–652.

- Slone, M., and S. Mann. 2016. “Effects of War, Terrorism and Armed Conflict on Young Children: A Systematic Review.” Child Psychiatry & Human Development 47 (6): 950–965. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-016-0626-7.

- Stockemer, Daniel. 2023. “The Russia-Ukraine War: A Good Case Study for Students to Learn and Apply the Critical Juncture Framework.” Journal of Political Science Education, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/15512169.2023.2286472.

- Strachan, Hew, ed. 2014. The Changing Character of Warfare. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sullivan, Becky. 2022. “Russia’s at War with Ukraine. Here’s How We Got Here.” NPR, February 24. https://www.npr.org/2022/02/12/1080205477/history-ukraine-russia.

- Teremetskyi, Vladyslav, Volodymyr Valihura, Maryna Slatvinska, Valentyna Bryndak, and Inna Gutsul. 2024. “Tax Policy of Ukraine in Terms of Martial law.” Policy Studies 45 (3-4): 293–309.

- Thakkar, Chirayu. 2024. “Russia-Ukraine War, India, and US Grand Strategy: Punishing or Leveraging Neutrality?” Policy Studies 45 (3-4): 595–613.

- Thompson, William R. 1993. “The Consequences of War.” International Interactions 19 (1-2): 125–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050629308434822.

- Tilly, Charles. 1992. Coercion, Capital and European States. AD 990–1992. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Trebesch, Christoph, Arianna Antezza, Katelyn Bushnell, Pietro Bomprezzi, Yelmurat Dyussimbinov, Andre Frank, Pascal Frank, et al. 2024. “The Ukraine Support Tracker: Which Countries Help Ukraine and How?” Kiel Working Paper 2218: 1–75.

- Vasquez, John A. 2009. The War Puzzle Revisited. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Vilpišauskas, Ramūnas. 2024. “Gradually and Then Suddenly: The Effects of Russia’s Attacks on the Evolution of Cybersecurity Policy in Lithuania.” Policy Studies 45 (3-4): 467–488.

- von Clausewitz, Carl. 1976. On War. Edited and translated by Michael Howard and Peter Paret. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Walker, Nigel. 2023a. “Conflict in Ukraine: A Timeline (2014-eve of 2022 Invasion).” House of Commons Library: Research Briefing, August 22, 2023. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9476/.

- Walker, Nigel. 2023b. “Conflict in Ukraine: A Timeline (Current Conflict, 2022-Present).” House of Commons Library: Research Briefing, October 18, 2023. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9476/.