Abstract

NaviCare/SoinsNavi was a research-based patient navigation center for children/youth with complex care needs (CCNs) in New Brunswick, Canada. This process evaluation focused on the implementation of NaviCare/SoinsNavi by exploring indicators related to program coverage and process. Key indicators were explored using client charts and program archives as well as stakeholder interviews with clients (n = 14) and members of the NaviCare/SoinsNavi team (n = 6). NaviCare/SoinsNavi served 162 families and 42 care providers between January 2017 and May 2020. Most clients lived in one of the three major cities in New Brunswick (Saint John, Fredericton, and Moncton), and were English-speaking. The most commonly reported diagnoses were autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and global developmental delay. The most prominent themes among NaviCare/SoinsNavi team members related to program coverage and program process were (1) expanding the reach and coverage of NaviCare/SoinsNavi through the implementation of a sustained outreach strategy; (2) maintaining the center’s research program; and (3) continuing to build stakeholder relationships to support integrated models of care. The most prominent themes among clients related to program coverage and program process were (1) client satisfaction with program implementation for both caregivers and care providers; (2) recommendations for more sustained outreach strategies; (3) a desire for more hands-on support; and (4) the need to continue building stakeholder relationships to support integrated models of care. This process evaluation demonstrated that NaviCare/SoinsNavi was successfully implemented as planned and produced recommendations for improvements to future iterations of the program.

Introduction

Approximately 15% to 18% of children and youth in North America live with conditions that impact their health and quality of life, which often lead to complex care needs (CCNs; Brenner et al., Citation2018; Cohen et al., Citation2012). CCNs are multidimensional care needs that include some combination of health, social, and/or behavioral factors and can occur with or without an official diagnosis or medical condition (Breneol et al., Citation2017; Brenner et al., Citation2018; Cohen et al., Citation2011, Citation2012; National Research Council, Citation2015). Children/youth with CCNs often require more medical, social, and/or educational support than children/youth in general and are vulnerable to experiencing several challenges and barriers to accessing care across settings, services, and sectors (Breneol et al., Citation2017; Brenner et al., Citation2018; Cohen et al., Citation2011, Citation2012; National Research Council, Citation2015). Indeed, Canadian families of children with CCNs and their care providers report gaps in services and experience difficulty navigating the health and social care systems (Doucet et al., Citation2017; Luke et al., Citation2018). Currently, there is a need for care interventions that are community-based and focus on connecting various levels of healthcare and community services for children/youth with CCNs (Doucet et al., Citation2017; Luke et al., Citation2018).

Patient navigation has been considered one way to address these gaps in care and services. Generally, patient navigation programs aim to facilitate integrated patient-centered care by linking patients and families to a wide range of services (i.e., primary care, specialist care, community-based services, social services) and help patients and care providers identify and overcome barriers to care (Valaitis et al., Citation2017). Recent studies evaluating pediatric patient navigation programs demonstrate that these services may be an effective way to facilitate access to care in fragmented healthcare systems, particularly for pediatric patients with CCNs (Feinberg et al., Citation2020; Hirth et al., Citation2019; Luke et al., Citation2020). For example, Hirth et al. (Citation2019) explored caregiver perceptions of a patient navigation program to increase human papillomavirus vaccination in pediatric clinics. This evaluation showed that caregivers thought the navigation program provided valuable support and information. Another example is a randomized control trial that assessed the effectiveness of a patient navigation program for families seeking an autism assessment for their child. Compared to standard care, the navigation program improved satisfaction with care and completion of the diagnostic assessment (Feinberg et al., Citation2020). Finally, Luke et al. (Citation2020) explored the experiences of caregivers of children/youth with CCNs who were clients at a patient navigation center. Caregivers reported that the patient navigation service enhanced their overall caregiver experience by providing needed support and knowledge about healthcare and social care systems they may access.

A recent scan of pediatric patient navigation programs across Canada indicated that pediatric patient navigation is being used across the country to improve the coordination of care across different levels of health and community care (Luke et al., Citation2018). The environmental scan identified 23 navigation programs, with representation across Canada. The purpose of most programs appeared to be consistent and focused on helping patients overcome barriers related to fragmented or siloed care systems through support, education, and improved access to resources and services (Luke et al., Citation2018). The scan showed ample variation across navigation programs regarding condition type, target population, patient navigator background, and delivery format; however, many programs targeted patients with specific health conditions. In New Brunswick, for example, the environmental scan found patient navigators working in the areas of pediatric oncology and mobility disability, but no navigation programs were identified for children with CCNs more broadly (Luke et al., Citation2018). To address this gap, a navigation center for children/youth with CCNs and their families was developed and implemented in New Brunswick, Canada. NaviCare/SoinsNavi was a bilingual (English and French) research-based patient navigation center for children/youth 25 years of age or younger with CCNs and their families across the province. This was the first navigation center of its kind in New Brunswick (Doucet et al., Citation2019).

The intervention

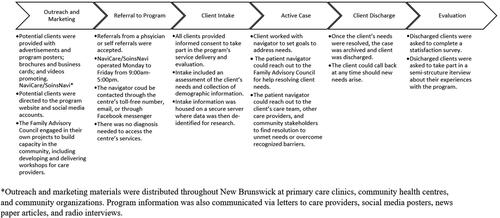

The aim of NaviCare/SoinsNavi was to help facilitate more convenient and integrated care to support the physical, mental, emotional, social, cultural, and spiritual needs of children/youth and their families using a personalized family-centered model of care, thereby improving the overall care experience for children/youth with CCNs and their families. A patient navigator helped coordinate patient care; facilitate transitions in care; connect families with appropriate resources; and inform families about health, education, and social services available to meet their needs and was a resource for the care team. These services were provided free of charge. The implementation of NaviCare/SoinsNavi was initially funded by the New Brunswick Children’s Foundation, a nonprofit charity organization, in 2015. The day-to-day operations of NaviCare/SoinsNavi were originally contracted out to a company that runs a telecare program in the province; however, as additional services and in-kind support from the University of New Brunswick and other research networks became more accessible, the team decided to establish the program at the University of New Brunswick. Due to the resulting changes to the program (e.g., changes in location, staff, and data collection procedures), the team revised their logic model to better reflect the program as well as to guide implementation and evaluation (Luck et al., Citation2019). This logic model is a visual representation of the required resources, activities, and outputs considered necessary for successful program implementation and for the research and evaluation of the program processes (Luck et al., Citation2019).

Day-to-day operations were assumed by a patient navigator, a registered nurse, who managed all patient cases. In addition to a patient navigator, the team also included three co-directors, seven volunteers (parents of children/youth with CCNs or youth/young adults who have experienced growing up with CCNs who sit on a Patient and Family Advisory Council), and several trainees and researchers who enabled the center to function effectively. Being housed at a university gave the center access to many established resources, for example, a secure data server (to house data collected), a marketing department (to help design public relations materials and market the program), a finance department (to manage operational budgets), office space (for the patient navigator and research team), and a human resource department (to support employment requirements).

Although the focus for NaviCare/SoinsNavi was on directly improving the care experience of children/youth with CCNs and their families, research and advocacy for system change were also an integral piece in fulfilling the NaviCare/SoinsNavi vision and mission and ensuring the success of this program. Continued research and evaluation allows the NaviCare/SoinsNavi team to learn more about the needs if the population they served and to monitor program implementation. This research and evaluation also provides the knowledge and experience to advocate for the continued improvement in quality care for this population (see for NaviCare/SoinsNavi Client Pathway).

This research presents a process evaluation of NaviCare/SoinsNavi. While most outcome evaluations explore the effectiveness of a program over the short or long term, process evaluations demonstrate how program outcomes were achieved (Carroll et al., Citation2007). As such, process evaluations are generally concerned with whether the intervention or program was implemented effectively and as originally planned (Carroll et al., Citation2007). Assessing how a program is implemented is important, as research has demonstrated that implementation impacts how the intervention affects desired outcomes (Carroll et al., Citation2007; Goense et al., Citation2016). For example, an outcome evaluation may assume that an intervention is being implemented according to the researchers prescribed protocol; however, unless an evaluation of the program process is conducted, it cannot be determined whether issues with effectiveness are due to poor implementation or problems with the intervention itself (Carroll et al., Citation2007). Indeed, a meta-analysis examining the effect of treatment integrity on client outcomes of evidence-based interventions for juveniles with antisocial behavior found that high levels of treatment integrity are positively associated with positive client outcomes (Goense et al., Citation2016). The current process evaluation focuses on the implementation of NaviCare/SoinsNavi and aims to determine how successfully the project followed the strategy laid out in the team’s logic model (Luck et al., Citation2019).

Method

Design

This evaluation was conducted based on the logic model developed by the NaviCare/SoinsNavi team (Luck et al., Citation2019) and took guidance from the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Process Evaluations Workbook (World Health Organisation, Citation2001). We used a mixed-method design to explore indicators related to both program coverage and program process. This evaluation addressed the following research questions.

Program coverage:

Has the program served the intended clients?

What were the demographic and clinical characteristics of clients accessing this program?

Program process:

3. Has the program been implemented according to the program’s logic model in terms of outreach/marketing strategies, patient navigation services, research and training activities, and facilitating integrated care?

Data collection

NaviCare/SoinsNavi client data were routinely collected for the purpose of research and evaluation. The NaviCare/SoinsNavi team received ethics approval for an evaluation from the University of New Brunswick’s Research Ethics Board (REB file number 026-2016). All clients included in this evaluation provided informed consent to have their data used for research and evaluation purposes. For the current process evaluation, retrospective chart data were retrieved from the University of New Brunswick’s secure server, where NaviCare/SoinsNavi stored client information. Interviews were routinely conducted with clients after they had been discharged from the program. This client interview data were stored on a secure server and were retrieved for the purpose of this process evaluation. Additional interviews were conducted with members of the NaviCare/SoinsNavi team specifically for this evaluation. These interviews were conducted virtually or in-person at the university by the lead author.

Retrospective chart review

NaviCare/SoinsNavi maintained a client database containing information relating to client characteristics (e.g., age, gender, and location), as well as other indicators of program coverage, such as medical diagnoses and reasons for contacting NaviCare/SoinsNavi. Quantitative data were extracted from 204 client charts spanning from January 2017 to May 2020.

Administrative files

Additional program information was extracted from NaviCare/SoinsNavi program files using a data extraction Excel sheet. This included, for example, outreach tools, resource lists, reports and news releases, and knowledge translation activities.

Stakeholder interviews

A qualitative descriptive design was used to collect and analyze stakeholder interviews. During the initial consent process, clients were also asked to consent to being contacted for a qualitative study exploring their experiences with the program. Clients who consented were contacted by a member of the research team once their case was closed by the patient navigator. Thirty caregivers and 11 care providers had previously completed interviews about their experience with NaviCare/SoinsNavi at the time of this evaluation. These interviews were conducted by a trained research assistant working with NaviCare/SoinsNavi, as part of an ongoing outcome evaluation of the center. Interviews followed a semi-structured interview guide and focused on the client’s experience with NaviCare/SoinsNavi, and all interviews were transcribed verbatim. All interviews were analyzed in detail for an outcome evaluation; however, the current process evaluation focused on a randomly selected subset of these interviews to maintain a manageable dataset overall. Furthermore, for the purpose of this process evaluation, we only focused on topics such as satisfaction with service implementation, patient navigator skills, services received, and referral source. Examples of interview questions include: “Did the patient navigator appear to be knowledgeable about programs and services?” and “What are potential areas where the center can make improvements to support care providers and families around navigation and coordination of care for children with complex health conditions?” (See Appendix A for interview guides.)

For the current process evaluation, 14 client interviews were randomly selected for analysis (eight caregivers and six care providers). Six additional semi-structured interviews were conducted by the lead author with members of the NaviCare/SoinsNavi team for the purpose of this process evaluation (three co-directors, two patient navigators, and one member of the Family Advisory Council). Interviews took place in a private setting at the university and were conducted by the lead author using a semi-structured interview guide. These interviews focused on program implementation and included topics such as program reach/recruitment, staff roles, use of program resources, service delivery, and program implementation. Examples of questions include the following: “Do you feel NaviCare is currently reaching all of their target populations (why/why not)?” “How sufficient is the staffing, in terms of numbers of staff and competencies for the functions that must be performed?” “How do you feel the resources, facilities, and funding support important program functions?” “Could you describe how the program coordinates with other programs and agencies with which it interacts?” (See Appendix A for interview guides.) These interviews were transcribed verbatim by the lead author.

Many guidelines exist for estimating adequate sample size for qualitative research studies, which vary depending on the type of qualitative analysis being used. Thematic saturation, for example, is a concept often used to project sample size, with thematic saturation occurring when new data does not significantly add to existing themes (Guest et al., Citation2006; Robinson, Citation2014). Specifically, Guest et al. (Citation2006) reported thematic saturation after the analysis of 6 to 12 interviews. Information power is another concept that can guide sample size and takes into consideration the aim of the study, sample specificity, use of established theory, quality of dialogue, and analysis strategy (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021; Malterud et al., Citation2016). This process evaluation employed thematic analysis, with the use of a codebook that was created inductively (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019, Citation2021). The research questions for this study are narrow and focus on the implementation of the program. Moreover, participants were drawn from a subsample of NaviCare/SoinsNavi clients. We used semi-structured interviews which resulted in focused, in-depth dialogue with participants. With these factors in mind, the authors believe that the current sample size of 14 clients and 6 program stakeholders provided sufficient information power for the description of experiences with the implementation of NaviCare/SoinsNavi (Malterud et al., Citation2016).

Analysis

Retrospective chart data were organized and analyzed using IBM SPSS statistical software. Descriptive statistics were obtained for all key indicators of program coverage and process. Interviews with the NaviCare/SoinsNavi team were conducted for the purpose of this process evaluation and the interview guide reflected this purpose. Interviews with clients, however, were previously conducted for the purpose of program improvement. Therefore, for the current process evaluation, these data were analyzed through the lens of program process. Program process activities were divided into four sections, based on the NaviCare/SoinsNavi logic model: outreach/marketing, patient navigation, research and training, and integrated care (Luck et al., Citation2019).

Given the differences in data collection, interview data were analyzed separately for the two stakeholder groups. Thematic analysis was used to explore key points related to the implementation of the NaviCare/SoinsNavi program and was guided by Braun and Clarke’s phases of thematic analysis. This is a flexible and accessible approach to qualitative analysis that focuses on data familiarization, data coding, theme development, and revision (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Specifically, we used the codebook approach to thematic analysis to help chart and guide the coding process (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). This approach is often used in the fields of health research and policy change (i.e., identifying facilitators and barriers to successful program and policy development) (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). First, all interviews were uploaded to NVivo 12 software for review, organization, and analysis of the interview data. Second, preliminary coding of the data was conducted by the lead author and a trained research assistant. Next, through an iterative process, the researchers generated key themes, which were refined and reviewed by the research team. Finally, principal themes were labeled and defined for reporting results.

Results: retrospective chart review/administrative files

Program coverage

Program coverage includes information on NaviCare/SoinsNavi’s reach of children/youth with CCNs, their caregivers, and care providers through enrollment numbers, demographic information, medical information, and reasons for contacting NaviCare/SoinsNavi.

Children/youth with CCNs and their caregivers

NaviCare/SoinsNavi aimed to serve children/youth with CCNs and their families throughout the province of New Brunswick. NaviCare/SoinsNavi served 162 patients and caregivers between January 2017 and May 2020. The majority of clients were caregivers of children/youth with CCNs, and most reported being the mother of the individual with CCNs (82.5%). These caregiver clients were located in five different health zones in New Brunswick, with most clients residing in the Saint John (47.76%), Fredericton (23.88%), Moncton (23.88%) areas. Although NaviCare/SoinsNavi is a bilingual (English/French) service, the majority of caregiver clients preferred receiving services in English (92.86%). Demographic information about children/youth enrolled in the program is presented in through .

Table 1. Child/youth gender and age (N = 141).

Table 2. Child/youth diagnoses by category.

Table 3. Number of diagnoses per child/youth.

Caregiver clients contacted NaviCare/SoinsNavi for a number of reasons; however, the majority of clients contacted the program requesting referrals to local resources and services (75%). These clients were commonly requesting general information on programs and resources appropriate for the child/youth with CCNs and their families. Many caregiver clients also contacted NaviCare/SoinsNavi for help with care coordination (11.11%). These inquiries often included requests for help organizing patient care activities and sharing information among care providers to achieve safer and more effective care, including diagnosis coordination. Given the complexity of care needs, it was interesting to find that many caregiver clients contacted NaviCare/SoinsNavi for only one or two distinct needs (65.60% and 31.21%, respectively).

Care providers

NaviCare/SoinsNavi also aimed to serve care providers across the province of New Brunswick by connecting care providers with resources and services across health, education, and social sectors. NaviCare/SoinsNavi served 42 care providers between January 2017 and May 2020. Most care providers worked in the Saint John (47.5%) and Moncton (30%) areas, with 92.68% preferring to receive services in English. Care provider clients came from a variety of programs and professions; the most common was the social work and community care sector (53.66%). A number of the care provider clients worked in healthcare (29.27%) and education (14.63%). Most care providers (53.85%) contacted NaviCare/SoinsNavi for referrals to resources and training opportunities for their patients, including services for newcomers. Furthermore, many care providers requested information about funding for their patients (e.g., for equipment or travel for medical purposes) and help with care coordination (25.64% and 15.38%, respectively).

Program process

Program process activities were divided into four sections which aligned with the NaviCare/SoinsNavi logic model: outreach/marketing; patient navigation; research and training; and integrated care (Luck et al., Citation2019).

Outreach/marketing

Outreach and marketing activities outlined in NaviCare/SoinsNavi’s logic model included developing a marketing and outreach plan; creating and maintaining a bilingual website; and establishing phone, email, and fax lines for communications. The NaviCare/SoinsNavi team developed several outreach tools to advertise the navigation center and gain publicity throughout New Brunswick. For example, NaviCare/SoinsNavi was the focus of 14 reports and news releases. Outreach efforts involved contacting more than 494 possible referral sources throughout the province. Outreach tools included advertisements and program posters containing program information for potential clients; a standard referral letter form for pediatricians; brochures and business cards for distribution in community and healthcare sectors; as well as a program presentation and videos promoting NaviCare/SoinsNavi. The team developed a website and social media accounts where potential clients could access information and contact the NaviCare/SoinsNavi team.

Patient navigation

Patient navigation activities outlined in NaviCare/SoinsNavi’s logic model included developing client support tools and services, establishing and maintaining a Patient and Family Advisory Council, and developing standard operating procedures. With regard to client support tools, the center’s website contained a database of resources and services that were identified and validated by the NaviCare/SoinsNavi team (n = 463). The website also contained a database of camps that met the needs of many children/youth with CCNs and their families.

Establishment of the Patient and Family Advisory Council was a primary goal during the implementation of NaviCare/SoinsNavi. The Patient and Family Advisory Council comprised caregivers of children/youth with CCNs from different areas of the province, a member of NaviCare/SoinsNavi’s advisory committee who acted as co-chair of the Patient and Family Advisory Council (with another council member), and NaviCare/SoinsNavi’s administrative assistant who also supported the administrative needs of the Patient and Family Advisory Council. This group met monthly to discuss NaviCare/SoinsNavi activities and ways in which the Patient and Family Advisory Council could support the center and enhance patient navigation services. Members of the Family Advisory Council worked together to develop a Journey Map for children/youth with CCNs and their families, which is a pamphlet resource to support families as they care for a child or youth with CCNs. In November 2019, NaviCare/SoinsNavi’s Patient and Family Advisory Council hosted a workshop for individuals interested in learning more about the journey from pre-diagnosis to accessing resources to successful self-care for caregivers and families of children/youth with CCNs. The journey map provides tips on how to navigate different stages of the journey to healthcare for their families.

Standard operating procedures are essential to the efficient implementation of any program. NaviCare/SoinsNavi had an advisory committee that met approximately once per month. To facilitate the day-to-day operations of NaviCare/SoinsNavi and streamline the intake process, data collection, and management of client cases, the committee developed 10 work processes and procedures documents related to intake, navigation, disenrollment, gaps in service, and outreach. The committee also developed four position descriptions for roles that were deemed essential to the functioning of NaviCare/SoinsNavi. These role profiles include patient navigator, physician consultant, co-directors, and senior advisor/research associate. At least one stakeholder had to fill each position. Although the center developed a standard referral process for care providers, patient and caregiver clients were directed to NaviCare/SoinsNavi through several different sources. Although there were only a small number of referrals using the official NaviCare/SoinsNavi referral form (n = 9), the majority of clients did report hearing about NaviCare/SoinsNavi from a physician (46.94%). Another large portion of clients heard about NaviCare/SoinsNavi from a health worker/counselor/community coordinator (31.63%).

The patient navigator tracked the amount of time spent with clients since January 2019, and we have data from 76 clients. These data indicated that most NaviCare/SoinsNavi clients had cases open for a period of 4 to 7 months before being discharged from the program (45.25%), followed by a number of clients with cases open for 1 to 3 months (33.58%). The patient navigator spent an average of 76.6 minutes (∼1.25 hours) in direct contact with each client and an average of 171.24 minutes (∼3 hours) per client on research and coordinating services. Most care provider clients had a case open with NaviCare/SoinsNavi for less than 1 month (53.85%), with another large portion of care providers having open cases for 1 to 3 months (30.77%). The patient navigator spent an average of 35.33 minutes in direct contact per care provider client and spent an average of 122.22 minutes (∼1.5 hours) on research and service coordination per care provider client.

Research and training

Research and training activities outlined in NaviCare/SoinsNavi’s logic model included developing a research consent process, developing data collection processes, developing research projects, supporting research trainees, and undertaking knowledge translation activities. All clients enrolled with NaviCare/SoinsNavi services were asked to provide informed consent to be contacted for research purposes. The team continually assessed client feedback by sending out satisfaction surveys and conducting interviews with clients once they had been discharged from the program. NaviCare/SoinsNavi spurred the development of more than 30 internal research projects focused on children/youth with CCNs, and the NaviCare/SoinsNavi team supervised more than 15 research trainees. These undertakings led to more than 50 knowledge translation activities (e.g., publications, posters, presentations).

Integrated care/stakeholder relationships

Activities related to integrated care outlined in NaviCare/SoinsNavi’s logic model included building stakeholder relationships to inform practice and policy and developing best practice guidelines to support the patient-centered care of children/youth with CCNs. The NaviCare/SoinsNavi team developed one policy brief and presented to the Government of New Brunswick on four occasions and the Government of Prince Edward Island on two occasions. Additionally, members of the team presented at grand rounds at the largest tertiary care hospital in the province. The patient navigators connected with dozens of clinicians while conducting outreach activities and the center fostered partnerships with 23 related programs (navigation centers, etc.). NaviCare/SoinsNavi established a formal partnership with a New Brunswick pediatrician who served as a consultant for the center, as well as more informal partnerships with a number of other pediatric providers.

Results: stakeholder interviews

Interviews with the NaviCare/SoinsNavi team

Interviews with members of the NaviCare/SoinsNavi team included the three co-directors who were responsible for overseeing the center’s service delivery and research program, one current patient navigator, one past patient navigator, as well as one caregiver who sat on the Family Advisory Council. These interviews focused on program implementation. The most prominent themes were (1) expanding the reach and coverage of NaviCare/SoinsNavi; (2) implementing sustained outreach and recruitment strategies; (3) maintaining the center’s research program; and (4) continuing to build stakeholder relationships to support integrated models of care. Overall, the NaviCare/SoinsNavi team believed that the program was being implemented as planned (see ).

Table 4. Themes.

Theme 1: expand reach and coverage

The most prominent theme to emerge from interviews with the NaviCare/SoinsNavi team was the desire to expand the reach of NaviCare/SoinsNavi. The center reached clients primarily from the Saint John, Moncton, and Fredericton regions of New Brunswick, although NaviCare/SoinsNavi aimed to serve residents from across the province. For example, one team member said:

I feel that we could definitely branch out further than the 3 main cities, so Moncton, Saint John, and Fredericton are where most of our calls come from. Where we are hoping to service youth all over NB, I feel that we are lacking a little bit more, like the more rural areas.

I think we’re really reaching southern NB and even within southern NB, we’re reaching mostly people with autism. Our intent is to reach individuals with complex care needs more broadly. So, I think we are hitting a really narrow geographical location, but also narrow in terms of diagnosis as well.

Theme 2: implement sustained outreach and recruitment strategies

Throughout the interviews, there was an emphasis on increasing NaviCare/SoinsNavi’s outreach efforts. One team member mentioned:

I think we need to, in an ongoing way, be communicating with people and getting the word out. Or like we’ll have a big marketing blitz and then we’ll fizzle out because we’ll get busy with something else. So, I think it’s just, in an ongoing way keeping a presence, people seeing us and keeping our name at the forefront and the service at the forefront of people’s minds.

So, we’re trying to build the social media a little bit more trying to get that out … I don’t know how we do that, but I feel like that would be helpful because then the patient navigator is gonna [sic] get more calls, and people are going to be able to access it more. Cause we’re so new, a lot of people don’t know we exist.

Theme 3: maintain NaviCare/SoinsNavi’s research program

Another prominent theme that emerged from the interviews was the importance of NaviCare/SoinsNavi’s research program. For those involved in the implementation of NaviCare/SoinsNavi, the balance between maintaining quality service delivery and establishing a research program was considered essential but difficult. For example, one team member said: “Sometimes you don’t want the research to get in the way of the service delivery, [but] on the flip side the service is a research project.” Another team member mentioned:

I think that was another shift that was really tricky, because it started up as a service, the research was very much, almost secondary and then when we shifted it here [current location], it’s a research project and we’re actually evaluating this service.

We need somebody who is kind of keeping an eye on NaviCare … looking at it from a research lens as well and so I think that’s what’s really needed is to get somebody back in that research assistant role, to oversee everything that’s happening and to keep things rolling.

Theme 4: continue to build stakeholder relationships

The NaviCare/SoinsNavi team emphasized the importance of fostering strong stakeholder relationships to improve care for children/youth with CCNs and their families. Collaboration among patients, families, and care providers was seen as paramount in the development of a true patient-centered navigation center. One team member said, “I think that ongoing collaboration with professionals is going to be really important,” while another mentioned, “With other agencies, there’s a lot of communication and kind of idea bouncing off each other. A lot of people will call and ask questions and if I have the answer, or we’ll work together to find the answer.”

Interviews with clients

Interviews with NaviCare/SoinsNavi clients were routinely conducted after clients were discharged from the program, as part of an outcome evaluation of the center. A randomly sampled subset of these interviews was selected for the purpose of this process evaluation. The analysis of these interviews focused on content related to program implementation. The most prominent themes were (1) client satisfaction with program implementation for both caregivers and care providers; (2) lack of awareness of NaviCare/SoinsNavi; (3) a desire for more hands-on support; and (4) the need for collaborative care (see ).

Theme 1: satisfaction with program implementation

The most prominent theme in the client interview data was satisfaction with navigation services. Clients reported feeling supported by the patient navigator and that the patient navigator was a good advocate for families caring for children/youth with CCNs. One caregiver client said:

I think everybody else has a very specific mandate, whether, you know it’s a specific service like, you know, speech language, occupational therapy, paediatrician, you know, they all have a special mandate … but yet I think sometimes in that, the listening part gets maybe a little bit, um, jumbled, and so that was the first day that I can honestly say when I hung up the phone I thought to myself—wow, she really listened to me and she understood what it was that my husband and I are struggling with so badly.

I mean, she helped me to see that my voice matters and that what I was seeing with my daughter, perhaps somebody else would be able to see the same way, and, you know, and that it was okay to ask for somebody else to assess her and that’s all it took. I had the confidence to just speak with our family doctor, who was like “absolutely we can do this” and sent off a consult to the—a second pediatrician, and then the ball just kind of went from there. But had she, the navigator from NaviCare, not helped me feel that it was okay, then, you know I may not have done that, and we may have just, kind of, continued on, I guess.

I know a little bit about the healthcare system, but it was really beyond anything that I had ever experienced before or specific training. Umm, I would know a very, very basic level of maybe you should reach out to extramural and that’s about it. So, it was very helpful because I had no idea how to navigate that system.

It wasn’t a typical situation. So, it allowed me to step away from the area that I really wasn’t comfortable with, where I didn’t feel that I had the expertise in. So, it does really help me in my work.

Theme 2: lack of awareness of NaviCare/SoinsNavi

Clients, particularly care providers, believed that NaviCare/SoinsNavi could improve their outreach strategies to reach more potential clients. For example, many care providers were unaware NaviCare/SoinsNavi existed or were unaware of the services the center offered. One client said: “The only thing I would say is that, like, I work in a building full of helping professions and nobody knew about NaviCare.” While another mentioned:

I think just awareness; there is a lot of people and it’s the same with my organization, a lot of people do not know that we exist. And it’s the same thing with NaviCare. I was just talking to an [occupational therapist] yesterday who was just running into some barriers, and I told her you need to call NaviCare.

Theme 3: increase navigator hands-on support

NaviCare/SoinsNavi aimed to provide a holistic service to clients to facilitate integrated care for children/youth and their family. The majority of clients reported being satisfied with NaviCare/SoinsNavi services; however, some clients reported they would have liked to receive more resources from the patient navigator. In a few cases, the clients reported that they only received a list of available services and resources, without follow-up or aid in accessing these resources. One client reported:

The relationship that I had was more of an—I’m telling her what his condition is and how I’m getting it treated—you know, just kind of keeping her up to date. You know, maybe it’s a good bank for me to put my knowledge and my experience into. Maybe not so much me maybe withdrawing information from it.

Theme 4: need for collaborative care

NaviCare/SoinsNavi clients acknowledged the importance of building and maintaining strong stakeholder relationships to improve care for children/youth with CCNs and their families. Care providers, in particular, recognized the importance of collaborating across providers and sectors. One client said:

NaviCare will often reach out to me for different advice, which I really value because it seems it’s like a partnership. It’s not one-sided. Just overall to continue to co-support people I think that’s very important to have that relationship between families and different organizations or associations and to really be a collaborative source I guess because that has really been my experience from the start and it’s been really positive.

So, for me it is more of a collaboration. I had been working closely with [patient navigator]. She would call me and ask me about different resources and where to go for a handful of families. And then [patient navigator] and I were working together because I needed some updating of some of the resources that I provide for the families that I work with and certain questionnaires. … So, she could share with her families that she was working with, and I could share with my families that I was working with.

Discussion

Scant research is available assessing the implementation process of navigation programs, particularly navigation programs in pediatric care (Valaitis et al., Citation2017). This is the first process evaluation of NaviCare/SoinsNavi, a research-based navigation center for children/youth with CCNs and their families. Key indicators of program coverage and program process were evaluated by examining the inputs, activities, and outputs presented in NaviCare/SoinsNavi’s logic model (Luck et al., Citation2019). These components illustrate what is needed and how the program should be implemented to attain the desired outcomes (i.e., ultimately, improved experiences with navigating care) (Funnell & Rogers, Citation2011). The inputs included in NaviCare/SoinsNavi’s logic model describe the infrastructure that was put in place to implement this project, including university support, a patient navigator, researchers, trainees, the Family Advisory Council, and funding. This allowed the center to engage in a number of key activities related to outreach/marketing, patient navigation, research and training, and integrated care.

Outreach/marketing

The activities outlined in outreach/marketing are integral to recruitment and client retention. One of the most prevalent topics discussed in the stakeholder interviews was the need to expand the reach of NaviCare/SoinsNavi services. Although NaviCare/SoinsNavi aimed to provide services across New Brunswick in both official languages (English and French), the majority of clients were from the major cities in Southern New Brunswick (i.e., Saint John, Moncton, and Fredericton) and were English-speaking. Furthermore, a large proportion of children had a diagnosis of ASD and the majority of children were younger than 10 years old, despite the center providing services up to the age of 25. One way that the NaviCare/SoinsNavi team tried to expand the reach of the center was through a change in the program description for NaviCare/SoinsNavi. The center was formerly described as “a navigation center for children with complex care needs (CCNs) and their families.” This description was subsequently changed to “a navigation center for children with health care needs and their families.” The NaviCare/SoinsNavi team believed that this description would resonate with a broader range of clients, as many individuals may not consider their needs “complex” or may assume the original description refers to “medically complex” conditions and needs (Azar et al., Citation2020). In addition, the NaviCare/SoinsNavi team agreed that the center needed to do a targeted campaign to promote its ability to help with transitions in care, such as the transition from pediatric to adult care for young adults with CCNs. These modifications could change the way potential clients perceive the NaviCare/SoinsNavi’s purpose. In fact, Carroll et al. (Citation2007) proposed a framework for assessing program implementation in which participant responsiveness was a key factor. For example, if participants perceive an intervention or program as being not relevant to them, they will not engage in the program, and this can lead to limited uptake or coverage. Therefore, the change in messaging by NaviCare/SoinsNavi could be an effective way to reach a more diverse sample of children/youth in need of navigation services in the region.

Patient navigation

As laid out in the logic model, patient navigation is one of the central activities needed for NaviCare/SoinsNavi to accomplish its intended purpose. At the time of this evaluation, the center employed one patient navigator, a registered nurse, who maintained a comprehensive, up-to-date database containing client resources. The patient navigator was responsible for most of the day-to-day service delivery for the center. Overall, the patient navigation services were well received by clients. Overwhelmingly, clients reported that their patient navigator was knowledgeable and genuinely supportive. A good client–provider relationship has been shown to be a key factor when implementing a patient navigation program (Fiscella et al., Citation2011; Valaitis et al., Citation2017). For example, Fiscella et al. (Citation2011) found that satisfaction with navigation services and having a working alliance with the patient navigator were key factors in the success of navigation programs in general. This relationship between patient navigator and client was also enhanced by the sharing of health knowledge (Fiscella et al., Citation2011).

It is important to note, however, that some clients in the current process evaluation reported a desire for more support or more “hands-on” coordination from the NaviCare/SoinsNavi patient navigator, rather than the receipt of resource contacts they reported receiving. Many clients felt like they were on their own navigating healthcare and social systems, and often a list of resources is not enough. Quality of delivery has also been shown to be a key factor in assessing program implementation. Basically, if the content of an intervention or program is not delivered in a way that fits with service user needs, the full impact of the program may not be realized (Carroll et al., Citation2007). Although providing recommendations for relevant resources and their contact information is an important step in the navigation process, NaviCare/SoinsNavi also aimed for the patient navigator to help clients articulate their goals and prioritize them during an ongoing navigator–client relationship (Doucet et al., Citation2019). It is also possible that differences regarding client satisfaction are related to staff changes in the patient navigator position. This highlights the importance of having consistent program implementation strategies. These strategies could include training manuals or guidelines as well as monitoring and offering feedback for patient navigators (Carroll et al., Citation2007; Valaitis et al., Citation2017). This would help to ensure that the delivery of the program is as uniform as possible, while maintaining a patient-centered approach to care (Carroll et al., Citation2007).

Research and training

Research and training are an integral part of NaviCare/SoinsNavi’s original vision. The NaviCare/SoinsNavi team agreed that there should have been more focus on maintaining NaviCare/SoinsNavi’s research program. The patient navigator position with NaviCare/SoinsNavi was the only full-time position held through the center, and it was focused almost exclusively on service delivery. Given the limited staff, balancing service delivery while maintaining a productive research program proved to be a challenge. Indeed, Valaitis et al. (Citation2017) found that obtaining adequate human resources was an important consideration for the implementation and maintenance of navigation programs.

Integrated collaborative care

Building and maintaining relationships with other agencies and care providers throughout the province of New Brunswick was an essential step in the maintenance of NaviCare/SoinsNavi. In fact, Valaitis et al.’s (Citation2017) review on factors influencing the implementation of patient navigation programs indicated that both inter- and intra-organizational relationships were considered integral to the implementation and maintenance of patient navigation programs. Indeed, families who have children/youth with CCNs report that current systems are not well integrated and do not provide the necessary guidance for navigating across providers, settings, and even sectors, which can often lead to discontinuity in care (Doucet et al., Citation2017; Luke et al., Citation2018). Developing these inter- and intra-organizational relationships posed a challenge for NaviCare/SoinsNavi, largely because the patient navigator program was not embedded within the healthcare system (i.e., within a community health center, hospital clinic, etc.). This impacted recruitment of clients to the center, as NaviCare/SoinsNavi lacked the visibility it would have had if it was embedded within an established healthcare setting. In light of this limitation, NaviCare/SoinsNavi was able to continue building a database of resources for families in New Brunswick and to facilitate patient navigation with care providers across settings and sectors through forming strong working relationships with various stakeholders. Improving communication and collaboration between care providers and care sectors will support the integration of care for children/youth with CCNs and ultimately improve health outcomes for this population (Brenner et al., Citation2018).

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of this evaluation is the use of a mixed-methods design. Collecting both quantitative chart data and qualitative interview data allowed for a more complete understanding of how NaviCare/SoinsNavi was implemented, particularly the nuances surrounding changes in implementation since program inception. Indeed, it is important to keep in mind that during the first year of operation, NaviCare/SoinsNavi had a major change in implementation (transferred location of the center and changes to service delivery staff) that resulted in inconsistent data collection. For example, demographic variables such as ethnicity, education, and income were not consistently collected for families enrolled in the program. This information would have added to the description of program coverage. Moreover, data related to the time spent with each client were only available for the most recent 2 years of implementation. It is important to note that this process evaluation explored the implementation of a navigation center for children/youth with CCNs in New Brunswick. As such, the current findings represent the delivery of a specific program and may not be representative of service delivery in other areas.

Conclusions

The primary purpose of a process evaluation is to assess the implementation of a program, which refers to whether program delivery is consistent with the original program goals and design (Carroll et al., Citation2007). It is only by measuring whether a program has been implemented as planned that we can understand how and why the program is working, as well as how it can be improved to produce the desired outcomes. The current process evaluation demonstrated that NaviCare/SoinsNavi was implemented as planned (i.e., outputs were produced in the right quality and quantity), suggesting that NaviCare/SoinsNavi would produce the intended outcomes (Steckler & Linnan, Citation2002; Stufflebeam & Shinkfield, Citation2007). As discussed, NaviCare/SoinsNavi did face a few key barriers during implementation, which could be addressed in future iterations of the program. First, relocating the program from an academic institution to primary care clinics is advised, as it would facilitate better integration of care and increase program visibility. This shift would broaden the program’s reach, attracting a more diverse client base with varied diagnoses and needs. Additionally, ensuring consistency in patient care could be achieved by providing standardized navigation training for all navigators. This would ensure that all clients receive the same standard of care to meet their needs. Last, maintaining a robust research program alongside the navigation service would further enhance its quality. Regular research activities would keep patient navigators and the entire team informed about the latest advancements in navigation programs, evolving client needs, and relevant resources, contributing to ongoing program improvement and adaptation.

Moving forward, program outcomes will be assessed with an evaluation, which will include measures of short- (e.g., increased knowledge of resources and services), medium- (e.g., increased use of appropriate services and reduced stress for caregivers), and long-term outcomes (e.g., improved quality of life). These metrics will allow the NaviCare/SoinsNavi team to evaluate whether patient navigation improved the quality of care, user experiences, health outcomes, and cost-effectiveness of care for children/youth with CCNs (Doucet et al., Citation2019). As an adjunct to the current process evaluation, an outcome evaluation of NaviCare/SoinsNavi will be essential to provide stakeholders and policymakers with the necessary evidence that these patient-centered navigation services are needed in New Brunswick and elsewhere.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Brittany Skelding, MA, for contributing to qualitative data analysis.

Conflicts of interest

The contributing authors Dr. Shelley Doucet and Dr. Alison Luke were co-directors of NaviCare/SoinsNavi, which is the program being evaluated in this study. The lead author L.M. is a research associate at the University of New Brunswick with no previous associations with NaviCare/SoinsNavi.

References

- Azar, R., Doucet, S., Horsman, A., Charlton, P., Luke, A., Nagel, D. A., Hyndman, N., & Montelpare, W. (2020). A concept analysis of children with complex health conditions: Implications for research and practice. BMC Pediatrics, 20(1), 251. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02161-2

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13(2), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846

- Breneol, S., Belliveau, J., Cassidy, C., & Curran, J. A. (2017). Strategies to support transitions from hospital to home for children with medical complexity: A scoping review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 72, 91–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.04.011

- Brenner, M., Kidston, C., Hilliard, C., Coyne, I., Eustace-Cook, J., Doyle, C., Begley, T., & Barrett, M. J. (2018). Children’s complex care needs: A systematic concept analysis for multidisciplinary language. European Journal of Pediatrics, 177(11), 1641–1652. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-018-3216-9

- Carroll, C., Patterson, M., Wood, S., Booth, A., Rick, J., & Balain, S. (2007). A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implementation Science, 2(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-2-40

- Cohen, E., Kuo, D. Z., Agrawal, R., Berry, J. G., Bhagat, S. K., Simon, T. D., & Srivastava, R. (2011). Children with medical complexity: An emerging population for clinical and research initiatives. Pediatrics, 127(3), 529–538. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-0910

- Cohen, E., Lacombe-Duncan, A., Spalding, K., MacInnis, J., Nicholas, D., Narayanan, U. G., Gordon, M., Margolis, I., & Friedman, J. N. (2012). Integrated complex care coordination for children with medical complexity: A mixed-methods evaluation of tertiary care-community collaboration. BMC Health Services Research, 12(1), 366. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-366

- Doucet, S., Luke, A., Splane, J., & Azar, R. (2019). Patient navigation as an approach to improve the integration of care: The case of NaviCare/SoinsNavi. International Journal of Integrated Care, 19(4), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.4648

- Doucet, S., Nagel, D., Azar, R., Montelpare, W., Charlton, P., Hyndman, N., Luke, A., & Stoddard, R. (2017). A mixed-methods quick strike research protocol to learn about children with complex health conditions and their families. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 160940691773142. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917731426

- Feinberg, E., Kuhn, J., Eilenberg, J. S., Levinson, J., Patts, G., Cabral, H., & Broder-Fingert, S. (2020). Improving family navigation for children with autism: A comparison of two pilot randomized controlled trials. Academic Pediatrics, 20(S1876-2859), 30171–30176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2020.04.007

- Fiscella, K., Ransom, S., Jean-Pierre, P., Cella, D., Stein, K., Bauer, J. E., Crane-Okada, R., Gentry, S., Canosa, R., Smith, T., Sellers, J., Jankowski, E., & Walsh, K. (2011). Patient-reported outcome measures suitable to assessment of patient navigation. Cancer, 117(15 Suppl), 3603–3617. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26260

- Funnell, S. C., & Rogers, P. J. (2011). Purposeful program theory. Jossey-Bass.

- Goense, P. B., Assink, M., Stams, G. J. J. M., Boendermaker, L., & Hoeve, M. (2016). Making ‘what works’ work: A meta-analytic study of the effect of treatment integrity on outcomes of evidence-based interventions for juveniles with antisocial behavior. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 31, 106–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2016.08.003

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough?: An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903

- Hirth, J. M., Berenson, A. B., Cofie, L. E., Matsushita, L., Kuo, Y., & Rupp, R. E. (2019). Caregiver acceptance of a patient navigation program to increase human papillomavirus vaccination in pediatric clinics: A qualitative program evaluation. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 15(7-8), 1585–1591. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2019.1587276

- Luck, K., Doucet, S., & Luke, A. (2019). The development of a logic model to guide the planning and evaluation of a navigation centre for children and youth with complex care needs. Child & Youth Services, 41(4), 327–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2019.1684192

- Luke, A., Doucet, S., & Azar, R. (2018). Pediatric patient navigation models of care in Canada: An environmental scan. Paediatrics & Child Health, 23(3), e46–e55. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/pxx176

- Luke, A., Luck, K. E., & Doucet, S. (2020). Experiences of caregivers as clients of a patient navigation program for children and youth with complex care needs: A qualitative descriptive study. International Journal of Integrated Care, 20(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.5451

- Malterud, K., Siersma, V. D., & Guassora, A. D. (2016). Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753–1760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315617444

- National Research Council. (2015). Investing in the health and well-being of young adults. National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK284781/

- Robinson, O. C. (2014). Sampling in interview-based qualitative research: A theoretical and practical guide. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 11(1), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2013.801543

- Steckler, A., & Linnan, L. (2002). Process evaluation for public health interventions and research. Jossey-Bass.

- Stufflebeam, D. L., & Shinkfield, A. J. (2007). Evaluation theory, models, & applications. Jossey-Bass.

- Valaitis, R. K., Carter, N., Lam, A., Nicholl, J., Feather, J., & Cleghorn, L. (2017). Implementation and maintenance of patient navigation programs linking primary care with community-based health and social services: A scoping literature review. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2046-1

- World Health Organisation (WHO). (2001). Process evaluation workbook. WHO Press.

Appendix A:

Interview Guides

NaviCare/SoinsNavi Client Interview Guide

Satisfaction

1. Describe your experience with NaviCare/SoinsNavi.

2. How satisfied were you with NaviCare/SoinsNavi (e.g., the services offered by the patient navigator [PN])?

a. Prompting questions: Did the PN listen and understand issues related to your needs? Did the PN answer your questions? Address your concerns?

3. Did the PN direct you to any services or resources? Was this useful? Why or why not?

a. Prompting questions: Did the PN appear to be knowledgeable about programs and services? Did you learn about any new services and programs in NB or elsewhere?

4. Would you call the center again? Please explain why or why not.

5. Would you refer other families to use the center? Please briefly explain why or why not.

6. Have you used the NaviCare/SoinsNavi website? How satisfied were you with the contents of the website? Explain.

Knowledge

7. Did you learn about new programs or services for families with children with complex health conditions?

8. In what ways did the PN affect your ability to manage your child’s care? (Ask for examples.)

Experience with coordination, integration, and continuity of care

9. In what ways did the services provided through NaviCare/SoinsNavi affect the amount of time required to care for your child? Can you give examples?

10. In what ways did the services provided through NaviCare/SoinsNavi affect communication between you and your care team? Among members of your care team? Can you elaborate please?

a. Prompt: May need to explain care team. This could involve care providers through the healthcare system as well as through social service, the education system, not-for-profit organizations, or private organizations.

11. Can you describe how your experience with NaviCare/SoinsNavi’s PN has influenced or changed your ability to navigate the system?

Quality of life

12. We would like to know how caring for a child with complex health conditions affects your quality of life. Has this changed since your contact with the PN?

a. Prompting questions: Are you able to do the things you want/need to do? Has caring for your child affected your ability to work outside the home? Ask about missed days at work if applicable. Have these things changed since your involvement with the center?

13. We would like to know if your child is able to do the things they would like to do. Has this changed since your interaction with the PN?

a. Prompting questions: Does this affect their ability to play with friends, join clubs, do extra curricular activities, and/or attend school?

14. Are you able to access services and programs in a timely manner? Has this changed since your interaction with the PN?

General Overall Concluding Questions

15. To what extent have services from NaviCare/SoinsNavi affected your family?

16. What are potential areas where the center can make improvements to support care providers and families around navigation and coordination of care for children with complex health conditions?

17. Is there anything else you would like to add to regarding your experiences with NaviCare/SoinsNavi?

NaviCare/SoinsNavi Program Staff Interview Guide

NaviCare/SoinsNavi role

1. How would you describe your role with the NaviCare/SoinsNavi?

2. (For Patient and Family Advisory Committee members):

a. How would you describe the role of the FAC as a whole?

b. Do you feel supported by NaviCare staff?

c. Do you have recommendations for the FAC?

Reach and coverage associated with NaviCare services

3. Do you feel NaviCare is currently reaching all of their target populations? Probe: How is the target population being adequately reached by NaviCare?

4. In what ways, if any, do you feel reaching the target populations could be improved?

5. What other populations should the program be working with/targeting?

NaviCare/SoinsNavi staff

6. How sufficient is the staffing, in terms of numbers of staff and competencies for the functions that must be performed? Probe: What areas do you feel could be improved? Are there staffing areas that you feel need additional skillsets to be effective?

7. Could you describe how the staff work with each other? What works well, and what areas could be improved? How does the FAC fit in?

8. Could you describe how the program coordinates with other programs and agencies with which it interacts? Probe: In what ways, if any, could the effectiveness of coordination be improved?

NaviCare/SoinsNavi uses resources

9. How do you feel the resources, facilities, and funding support important program functions?

10. How could NaviCare improve its use of resources?

How NaviCare/SoinsNavi has developed over time

11. How has the program implementation changed over time? How has this impacted standard of care or services offered?

12. Is there anything else that you would like to add about your experience with NaviCare?