ABSTRACT

Lauded as the poster child of the sharing economy, the success of Uber’s business model was once viewed as inexorable. However, a disastrous Initial Public Offering and a series of legal rulings since have led some to question whether it has a viable model at all. This changing sentiment raises important questions about how we define a business model and understand the determinants of its success and failure. Rejecting the dominant diagnostic approach, this paper synthesises critical accounting work on business models as narratives with Suchman’s concept of organisational legitimacy. We argue that business models are narratives articulated by firms in order to achieve both pragmatic and moral legitimacy. In contexts where stakeholder interests diverge, this requires careful framing in order to foreground certain economic and moral representations whilst omitting others. Business model narratives are consequently partial, unstable and open to contestation. Applying this formulation to Uber, we argue that its pragmatic legitimacy was contingent upon a particular set of conjunctural conditions and the undisclosed exploitation of legal grey areas in order to grow at scale. We highlight the tensions that emerge when those undisclosed practices become a focal point for social mobilisation and understand Uber's recent problems as emerging from external challenges to the moral legitimacy of its business model narrative. The paper contributes to accounting research on business models and legitimacy and presents a revisionist account which positions platforms as fragile economic and moral entities dependent on conjunctural institutional and capital market arrangements, rather than heroic technological disruptors.

1. Introduction

In the last decade, Uber has emerged as a standard-bearer for the “sharing economy”, its growth has been represented as inexorable (Kavadias et al., Citation2016), and its business model seen as a force of “disruptive innovation” capable of displacing incumbents and transforming transportation (Kornberger et al., Citation2017). However, sustained criticism concerning the moral and social value of some of its corporate practices (Isaac, Citation2019; Peticca-Harris et al., Citation2018; Scholz, Citation2017) led to regulatory interventions that have tempered investor enthusiasm. In 2019, Uber’s IPO valuation price was between a quarter and a third lower than expected and, after two days trading, its share price had fallen by 17.6 per cent (Bond et al., Citation2019). Further difficulties followed with the 2021 UK Supreme Court ruling that drivers are to be classified as workers rather than self-employed, with potentially devastating consequences for its economic future (Venkataramakrishnan & Croft, Citation2021). In June 2022, a dossier (“the Uber files”) emerged highlighting Uber’s efforts to evade laws and secretly lobby governments (Davies et al., Citation2022). As we write, Uber’s share price is 22 per cent below its 2019 opening price despite a significant recovery in value post-Covid.

This article analyses these changing perceptions of Uber’s business model through the lens of organisational legitimacy. Synthesising Suchman’s (Citation1995) formulation of organisational legitimacy with critical accounting work on business models (Andersson et al., Citation2010; Froud et al., Citation2009; Gleadle & Haslam, Citation2010; Haslam et al., Citation2014) we argue that business models are narrativized objects, which, from the late 1990s on, became critical to the construction and maintenance of a firm’s legitimacy and thus its stability. Business model narratives, like reporting practices, operate within a multi-stakeholder context where competing concerns are attentive to conduct as well as economic performance (Mahadeo et al., Citation2011). Consequently, the role of any business model narrative is to present an agreeable explanation of the company’s economic and social contribution in order to secure both “pragmatic” (financial) and “moral” (pro-social) legitimacy, in Suchman’s terminology. Business model narratives are thus carefully framed – foregrounding certain aspects of firm practice, whilst leaving other practices undisclosed (Froud et al., Citation2009). For that reason, business model narratives are partial, unstable and open to contestation when those undisclosed practices are revealed, making organisational legitimacy often difficult to attain.

Our argument is that as a new venture, Uber initially achieved some degree of organisational legitimacy by aligning itself with the “sharing economy” and identifying as a digital disruptor intent on transforming urban transportation for the public good. We argue that this business model narrative was, however, vulnerable to two legitimacy challenges. First, the capacity to disrupt was dependent upon supportive, conjuncturally-contingent investor expectations and credit conditions which allowed Uber to undercut and displace incumbents by carrying heavy losses. The continuation of that financial support was dependent on investors’ willingness to tolerate high cash-burn levels in the collective belief that growth would lead eventually to a monopoly position, and so was always sensitive to events which threatened that potential. Second, that trajectory of growth also relied upon the exploitation of regulatory grey areas that pushed costs and risks onto drivers. This increased moral legitimacy risks and the probability of regulatory pushback, which could frustrate the attainment of a monopoly position, undermining pragmatic legitimacy. We argue, developing Suchman (Citation1995), that pragmatic and moral legitimacy are thus intertwined, generating self-reinforcing circuits of legitimacy or illegitimacy. We then show how a combination of social opposition and workforce antagonism led to regulatory tightening which eroded investor confidence and reduced the number of investors willing to provide the capital flows (at a particular price) needed for Uber to maintain solvency and sustain growth. We conclude that the legitimacy of platform company business models may be volatile leading to sudden bankruptcy risks, as the collapse of companies like WeWork and Theranos demonstrate.

This paper, therefore, builds on critical accounting research that emphasises governance and accountability tensions within the platform economy (Begkos & Antonopoulou, Citation2020; Chapman et al., Citation2021; Kornberger et al., Citation2017; Leoni & Parker, Citation2019; McDaid et al., Citation2019), providing a corrective to technologically-determinist views of digital platforms which understand their ascendency as inevitable and perceive Uber as an unstoppable force of disruptive innovation. Instead we understand Uber – and many other platforms – as fragile economic and moral entities dependent on conjuncturally-contingent institutional and capital market arrangements. Our analysis of Uber, which serves as a principal player in the ascendancy of platforms, has wider implications as the “basic internal limits” (Fleming et al., Citation2019, p. 488) of the gig economy emerge.

The following section presents Suchman’s (Citation1995) formulation of organisational legitimacy. It explains the role played by business model narratives in securing legitimation when facing multi-stakeholder interests, before outlining the significance of business model narratives for the legitimation of start-up firms who lack historical markers of reliability. The subsequent section outlines our critical accounting “narratives and numbers” method (Froud et al., Citation2006) and then applies that approach to Uber, examining both the disclosed and undisclosed elements of its business model. Uber’s business model narrative left two core elements undisclosed: the exploitation of benign capital market conditions by accepting large losses to displace competition; and operating in legal grey areas to facilitate growth and become “too big to ban”. The paper proceeds with a discussion of how legitimacy was compromised around undisclosed elements as public campaigns mobilised and regulators acted. Finally, the wider implications and research contribution are detailed.

2. Organisational legitimacy, business model narratives and start-ups

2.1. Organisational legitimacy

Legitimacy plays an important role in supporting different regimes, institutions and structures (Habermas, Citation1973; Parsons, Citation1960; Weber, Citation1964). The most influential discussion of “organizational legitimacy” is that of Suchman (Citation1995, p. 574) who defines it as a generalised perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions. For Suchman (Citation1995), organisational legitimacy is a social construct formed collectively over time, through events that engender a sense of behavioural consistency and predictability which constitute public approval. Although there are exceptions, legitimacy and stability are thus mutually reinforcing (Pfeffer, Citation1981). This is because core audiences generally invest in organisations which they perceive as consistently conforming to their own shared sense of acceptable or desirable behaviour (Cederström & Fleming, Citation2016). Of course, firms may try to manipulate external perceptions (Ashforth & BW, Citation1990), but they are also embedded in and constrained by prevailing societal expectations, which condition the boundaries of acceptable practice, as DiMaggio and Powell (Citation1983) famously argued.

Managing the balance between the ability to manipulate perceptions and being constrained by societal norms is at the heart of Suchman’s (Citation1995) analysis. Suchman identifies three analytical types: pragmatic, moral and cognitive legitimacy. Pragmatic legitimacy is secured when the perceived self-interested calculations of an organisation’s most immediate audiences (Suchman, Citation1995, p. 578) are met. This focuses mainly on exchange logics and a belief on the part of invested individuals that the actions of an organisation will benefit them directly, often financially. Moral legitimacy, on the other hand, rests on judgments which ask whether the organisation is viewed by its macro environment as being socially acceptable (Suchman, Citation1995, p. 579). These more “sociotropic” logics involve value judgements about whether the outcomes of behaviours and practice are moral, or at least conform to societal expectations about delivering socially-desirable outcomes (Islam et al., Citation2022; Mahadeo et al., Citation2011). The third type is cognitive which concerns external legitimacy and the level of knowledge about an activity (Georgiou & Jack, Citation2011). The highest form of cognitive legitimacy is achieved when a new product or service is taken-for-granted so that it becomes part of the general order of things and alternatives are rendered unthinkable (Suchman, Citation1995, p. 583).

Legitimacy theory, particularly the balance between pragmatic and moral concerns, has been used widely within the accounting literature to explore, amongst other things, the rise of social and environmental reporting as a way for firms to signal their commitment to values embraced by society (Deegan, Citation2002); or as a means of countering negative community sentiment (Deegan et al., Citation2002); the growth of the environmental assurance industry and assurance reporting generally (O’Dwyer et al., Citation2011), and the symbolic and substantive means through which viruses such as HIV/AIDS are reported (Soobaroyen & Ntim, Citation2013). More recently the approach has been criticised for its binarism – that organisations are seen as either “legitimate” or “illegitimate” – and the notion that legitimacy can be achieved by conforming with community expectations, when society is made up of different beliefs and expectations about corporations and their conduct (Deegan, Citation2019). It is therefore important to understand that evaluations of legitimacy are not static (Bitektine, Citation2011; Cederström & Fleming, Citation2016); they are made and remade as part of a social process (Palazzo & Scherer, Citation2006; Suddaby et al., Citation2017). And that achieving legitimacy can be fraught with tensions, especially when the interests of core audiences diverge (Zald, Citation1978). Consequently, perceptions of legitimacy may be contextually and temporally contingent, requiring different strategies to meet the long-term legitimacy challenges shared by a general audience and episodic challenges which pertain to the perceptions of a small group (Kuruppu et al., Citation2019).

It is therefore possible to achieve legitimacy within an ongoing process of contested interactions. But there are examples where coherence is lost, leading to a self-reinforcing crisis of legitimacy (Elsbach & Sutton, Citation1992). The question then is to understand the contingent contexts and social processes through which legitimacy is maintained or undermined. Part of that process involves the articulation of organised narratives by firms whose audiences hold different economic and social priorities.

2.2. Business models as legitimacy-building narratives

In polyarchic contexts, firms strive to develop forms of stakeholder dialogue which achieve a consensus around the nature of its activity (Unerman & Bennett, Citation2004). Since the dotcom boom, firms have sought to do this by distilling a simplified vision of their purpose and goals in operational, financial and social terms through the articulation of a “business model” (Feng et al., Citation2001). As critical work within accounting and management has noted, business models should therefore be understood as a type of company narrative (Andersson et al., Citation2010; Froud et al., Citation2006; Gleadle & Haslam, Citation2010; Haslam et al., Citation2014; see also Magretta, Citation2002) which, like strategy, is “constructed to persuade others toward certain understandings and actions” (Barry & Elmes, Citation1997, p. 443). This narrativized approach contrasts with accounts which view business models as something more essentialist, diagnostic and prescriptive; as architectures (Timmers, Citation1998), plans (Amit & Zott, Citation2001; Osterwalder et al., Citation2005) or heuristics (Chesbrough & Rosenbloom, Citation2002) that combine tangible components or processes strategically to add value or create profit for an organisation. A narrativized account, by way of contrast, views business models as an attempt to articulate those elements, infusing them with a set of coherent and consistent values that are broad enough to enrol disparate groups (Doganova & Eyquem-Renault, Citation2009). Placing this within Suchman’s framework, firms therefore seek to achieve legitimacy by developing business model narratives which explain their contribution in pragmatic and moral terms so that one may explain the other: for example, an organisation’s investment potential is explained by its social contribution.

This distinction between essentialist and narrativized approaches to business models has important analytical implications. Essentialist accounts tend to treat the rising share price of a company or some other measure of value as validation of a business model whose components drive its success. A narrativized account, which recognises the role of the business model narrative in building legitimacy, would acknowledge that the drivers of success may not be realistically disclosed by the firm without alienating certain publics. It would also recognise that narratives are credible in certain contexts but not others: a financial services company that explained its value proposition in terms of its skill in trading credit derivatives and its social contribution as the efficient distribution of risk, may have been credible in 2006 but not 2009 after the financial crisis. Consequently, as Suchman (Citation1995, p. 575) argues, the actions which enhance an organisation’s ability to remain a viable financial proposition are not necessarily the same as those that enhance their meaning as a force for social good.

These subtleties have been drawn out by accounting research that emphasises the careful framing required to foreground certain economic and moral representations, whilst omitting others in order to enrol broad audiences. Undisclosed elements or practices can coexist alongside disclosed business models and may be central to securing a firm’s pragmatic legitimacy. Froud et al. (Citation2006), for example, highlight how Jack Welch attributed General Electric’s success to its internal culture, developed through initiatives such as “WorkOut” and “Six Sigma”; whilst at the same time achieving pragmatic legitimacy by running the industrial businesses for high ROCE and an AAA credit rating which allowed the company to scale up its financial business profitably. The interplay of disclosed and undisclosed elements has also been explored in the case of Apple’s business model (Bergvall-Kåreborn & Howcroft, Citation2013; Froud et al., Citation2014; Lehan & Haslam, Citation2013; Montgomerie & Roscoe, Citation2013), highlighting the undisclosed role of supply chain cost control and consumer lock-in to explain elements of its success. Importantly the emphasis on the undisclosed does not imply that these elements are unknown or outside the public domain, but rather denotes practices that are not explicitly articulated as part of the business model, because to do so would undermine the legitimacy of that which firms chose to disclose (Froud et al., Citation2009).

2.3. Start-ups & business model narratives

The importance of business model framing is especially important for new ventures who strive to achieve legitimacy despite having little in the way of history or symbolic markers of reliability during the high-growth, loss-making phase of early stage development (Aldrich & Fiol, Citation1994, p. 651). When new ventures rely on a consistent flow of investor capital to remain solvent, firms must manage representations of their future potential in order to secure resources, sustain daily operations and achieve a growth profile that is likely to attract more capital investment in the next round of fundraising (Delmar & Shane, Citation2004; Garud et al., Citation2014). Some new ventures thus eschew the usual legitimacy-building strategy of environmental conformity (Suchman, Citation1995, p. 587) and instead develop business model narratives designed to “promulgate new explanations of social reality”, evoking the possibility of alternative futures (Suchman, Citation1995, p. 591). Start-up companies often explain how their business model will preserve or enhance experiences that consumers value, whilst emphasising distinctiveness, thereby setting themselves up as both familiar yet transformative (Foster et al., Citation2017; Rahman & Thelen, Citation2019). This balance between the recognisable and the metamorphic can reduce investor uncertainties and help attract inward investment (Lounsbury & Glynn, Citation2001). This is a difficult balance to strike, especially if disruption to the status quo is perceived as opportunist and instrumental, with little social benefit. Many start-up companies, therefore, experience acute tensions between pragmatic and moral legitimacy in their early years.

Platform companies provide an instructive, if extreme, example, articulating transformational business models that emphasise their ability to avoid being remade in the image of their environment, cultivating an oppositionist stance to extant structures and incumbent organisations who are portrayed as outmoded (Srnicek, Citation2017). As Suchman (Citation1995, p. 591) notes, this form of legitimacy-building can be effective when it adopts a more evangelist spirit, which can prove remarkably durable, particularly when it depends less upon observable events, and more upon collective imaginaries about the benefits to be accrued in some future state (Perkmann & Spicer, Citation2010). Legitimacy-building is thus more effective when firms are perceived to embody economic changes that are inexorable, transformative and benign, as seen with new economy firms in the 1990s (Glynn & Marquis, Citation2004). Like the dotcom boom, that relation between firm-level and economy-wide visions can produce self-fulfilling effects if they convince investors to provide capital to the organisation (Feng et al., Citation2001; Thrift, Citation2001). This creates the financial basis for the stability identified by Suchman (Citation1995) as a prerequisite of organisational legitimacy.

3. Methodology, data & methods

3.1. Methodological approach

To understand the interplay of business model narratives and organisational legitimacy in the case of Uber we follow the “narratives and numbers” approach of Froud et al. (Citation2006), which is concerned with how tensions are balanced or accumulate as companies confront a multi-stakeholder environment. This method also locates competing representations of individual companies within a wider conjunctural context that can support or undermine processes of legitimation (Froud et al., Citation2006, p. 122). Legitimation, given both its pragmatic and moral dimensions, requires the production of both narratives and numbers that are agreeable to the expectations of an external set of stakeholders. This approach to numbers is different from the Popperian view that they operate as an objective resource capable of falsifying specific claims. Similarly accounting numbers are not simply a function or output of corporate narratives, including business model narratives (although corporate narratives will always try to frame numbers positively). Rather accounting numbers are the outcome of an organisational process that involves the interpretation and implementation of prevailing accounting standards (Chua, Citation1986; Robson & Bottausci, Citation2018) and they are received and evaluated by stakeholders within a specific time and space. Numbers can thus be enrolled by a company to corroborate a narrative, but equally companies do not fully control how numbers are received by a community of users and they may also be used to unsettle or discredit business model narratives. Accounting numbers are thus semi-autonomous from corporate narratives and the way narratives and numbers relate is complex (see Froud et al., Citation2006, pp. 132–133). “Good” numbers can be, for example, enrolled to corroborate extant explanations of the business model, even when other undisclosed corporate practices may be driving those numbers. Similarly, numbers that are deemed “good” in one period may be viewed as “disappointing” in another, depending on context and expectations.

The narrative and numbers approach thus requires a more iterative, patchwork approach that pieces together an analysis of the different elements – representations, counter-representations, events, financial results and conjuncture – that change over time. As a case study method, it is thus more suitable to an emergent approach (Lee et al., Citation2007), owing less to the approach of Yin (Citation2014) which relies heavily on propositional knowledge where all research components that lead to a case study output are established in advance of the study taking place. It is more akin to the abductive approach of Stake (Citation1995) which emphasises the fundamental importance of judgement and the “ordinary process of interpretation” in distilling an argument from primary and secondary sources to provide a multi-layered interpretation of events.

3.2. Data collection & organisation

Following the logic of Froud et al. (Citation2006), our data collection strategy focused on (a) sources that help understand how Uber represent their own business model (b) sources that help understand the conjunctural contexts which support or undermine Uber’s capacity to achieve organisational legitimacy from its narrative and financial numbers (c) sources that help us understand practices which the company does not disclose as part of its business model narrative, but which help it achieve organisational legitimacy.

In terms of business model as Uber articulate it, we used two sources. First, we used the Dow Jones FactivaFootnote1 database to locate interview data with Uber executives and official statements by the company. Factiva provides more than 33000 global news sources, including the main international financial newspapers, such as the Financial Times, Wall Street Journal, the New York Times and many trade and industry journals. We confined our search to the four main business news outlets: The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The New York Times and the Financial Times for reasons of data manageability. These four newspapers also happened to be the outlets with the highest frequency of “hits” for our search string. In terms of dates, we limited our search to the years 2009 (the year Uber was formed) to 2021. Boolean search strings of “Uber” and “business model” and “interview” or “Kalanick” and “business model” and “interview” were applied since we were interested in Uber’s own narrative representations. Articles which did not contain direct quotes, official statements or interview material from Uber representatives were filtered out.

We also analysed Uber’s detailed explanation of its activity in its S-1 IPO submission document. An S-1 filing is issued by any company planning to go public in the US. In this case, Uber produced a 396 page document which provided an explanation of the business model to prospective investors, as well as detailed information on their financial position, corporate governance processes, management structure and corporate mission. This provided a rich resource for identifying business model themes as the company would like them to be understood as well as previously hard-to-get financial data. Prior to 2019 Uber did not issue any single document that outlined its business model, given its privately owned status.

In order to identify the conjunctural context of Uber’s business model, we used academic studies, the financial press and industry literature to understand the changing conjunctural landscape of start-up funding, and Uber’s funding specifically. By examining these sources over time we also formed a view of the emerging tensions in Uber’s business model and the capacity for those contextual elements to support the “numbers” – and expectations about the numbers – that contribute to Uber’s pragmatic legitimacy This provided background to our financial analysis of Uber. Our analysis of the “numbers” – which provide the financial context of Uber’s pragmatic legitimacy – drew on company accounting data listed on the CrunchbaseFootnote2 database and the financial disclosures in Uber’s S-1 IPO document. From these sources, we pieced together a multi-year analysis of trends in revenues, operating losses, net asset position, sources of financing (debt/equity), amounts raised during different funding rounds, the names of the individual investors and other pertinent accounting data.

Finally, on the “undisclosed” practices that contribute to Uber’s pragmatic legitimacy – we were aware of challenges to Uber’s business model narrative through our own exposure to newspaper reports about Uber’s predicament, and so, abductively following Stake (Citation1995), used a variety of search strings related to competition, regulatory avoidance, and labour issues, including employment (mis)classification and social protection on two databases. We used these search strings on googlescholar to locate academic journal articles, including ethnographies of, and interview material with, Uber drivers. We also used those strings on the Factiva database to access press reports on those themes. We observed a marked increase in these reports from early 2017 on, which was used as an empirically-informed inflection point to focus our reading, when counter-narratives which challenged the company’s business model narrative (i.e. its “undisclosed practices”) gained in ascendance. This focus was reinforced by Uber’s S-1 document which noted:

… our business performance was negatively impacted in early 2017 when we faced many challenges, including the #DeleteUber campaign that encouraged platform users to delete our app and cease use of our offerings.

3.3. Methods

In terms of methods, we used an abductive approach, which is more suitable for understanding an unfolding process of legitimation and de-legitimation, where academic judgement and interpretation plays an important role in distilling an argument from multiple data sources (Lee et al., Citation2007; Stake, Citation1995). Deep reading methods were used, once the above limiters were placed on the data so that it became manageable. Based on the data collection and analysis, we categorised Uber’s disclosed business model narrative into three components: its articulated logic, operating plan and value proposition. We identified the “undisclosed practices” – the actions which materially enhance, or enhance perceptions of, Uber’s financial stability, but were not formally disclosed as part of its narrated business model – by synthesising the findings from the Factiva database with wider academic literature. Two core undisclosed practices were identified from this analytic review: the exploitation of benign capital market conditions by accepting large losses to displace competition; and operating in legal grey areas to facilitate growth and become “too big to ban”. We examined the interplay of disclosed and undisclosed to inform the analysis of moral, pragmatic and cognitive legitimacy, which is detailed in the discussion section.

4. Uber’s disclosed business model and its undisclosed practices

4.1. Overview

Uber is a global transportation company founded in 2009 by Travis Kalanick and Garrett Camp in San Francisco, California. According to Kalanick, its objective was to provide a convenient and efficient alternative to traditional taxis by leveraging mobile technology. Uber’s primary activity consists of connecting passengers with drivers through a smartphone application. The application enables users to track the location of their ride in real-time and pay electronically, eliminating the need for cash transactions. Over time, Uber has expanded its services to include different options such as UberX, UberPOOL, UberEats, and even electric scooters and bicycles.

Since its inception, Uber has grown exponentially and now operates in hundreds of cities across the world, making it one of the most prominent players in the ride-hailing industry. The company's user base consists of both riders and drivers. Uber argues that riders appreciate the convenience and affordability of their service and drivers appreciate the higher returns and flexibility of using their own vehicles to work to their own schedule. Uber has placed a strong emphasis on innovation, disruption and growth, but this has often created scandals which have drawn regulatory challenges and controversies, as we will discuss below.

4.2. Uber’s disclosed business model

Uber’s disclosed business model can be broken down into three parts: its articulated logic (a broad picture of the firm’s purpose, what value it adds and how it will make money), operating plan (a description of the strategic objectives of the model and how each build towards that purpose) and value proposition (what the business offers to investors, consumers and society more broadly).

Uber initially presented its business model logic by aligning itself with pre-existing discourses around the sharing economy, which served as a credentialing mechanism (Rao, Citation1994) providing familiarity and thus plausibility for resource providers (Fisher et al., Citation2016). New ventures suffer from the unknowns associated with newness and notoriously high failure rates; fostering a connection with an identifiable sector, particularly “industries of the future”, can therefore help build cognitive legitimacy (Zimmerman & Zeitz, Citation2002). Uber thus explained its logic and purpose through affiliation, by borrowing the rules, values and practices of the sharing economy (Vasagar, Citation2014).Footnote3 Uber defined taxi-drivers as driver-partnersFootnote4 and deployed the inclusive language of “ridesharing” to underline its role in enabling private drivers to monetise their motor assetsFootnote5 (Uber, Citation2019). The redefinition of social relations formed the core of Uber’s logic which articulated how its moral legitimacy, represented in the “mutual benefits” offered by Uber to partner-drivers and consumers, created pragmatic legitimacy with opportunities for value creation.Footnote6

Uber narrated a three-part operating plan within this broader logic. The first was to challenge or avoid regulation to enable growth. This disruptive aspect was expressed in an early interview by founder Travis Kalanick who argued that its business model meant principled confrontation with existing regulations which were designed to protect … (the) incumbent industry, … providing less choices for citizens to get around the city (cited in Bradshaw, Citation2014). Uber cultivated an image of itself as a consumer champion, hampered by regulation in its quest to counter the established “taxi monopoly” and transform urban transportation. Uber’s narrated business model therefore centred on its self-identification as a digital intermediary rather than a transportation firm, which allowed it to question the applicability of the existing legal framework to its operations.Footnote7 This attempt to promulgate new explanations of social reality, in Suchman’s terms, enabled Uber to adopt a moral position against existing regulations which were framed as an anti-competitive block on new entrants. Avoiding, breaking or bending those rules could thus be justified through an appeal to higher principles (Suchman, Citation1995, p. 587), particularly around notions of “sharing”, consumer choice and the wider benefits of disruptive innovation.

The second aspect of Uber’s operating plan involved an articulation of its growth strategy. Uber provided incentives to drivers and consumers in order to scale the business geometrically and expand market share. Uber styled itself as an enabler, attracting driver-partners by offering opportunities for “micro-entrepreneurship” (Botsman, Citation2015), a practice which was emblematic of the sharing economy.Footnote8 Uber utilised a referral reward scheme to existing drivers, offered special discounts to new recruits and lowered the proportion of deductions of driver fares (Uber, Citation2019, p. 8Footnote9), thereby incentivising drivers to switch from other taxi firms and weaken competitors. Consumers were also offered discounts when signing up to the app (Uber, Citation2019, p. 8). These practices of cross-subsidization are typical of platform firms in pursuit of market share (Kenney et al., Citation2019).

A third aspect of Uber’s representation of its operating model was the development of proprietary marketplace, routing, and payments technologies’ including demand prediction, matching and dispatching, and pricing technologies (Uber, Citation2019, p. 1). Consumers would apparently benefit from functionality at scale with GPS smartphone technology, electronic payments and an algorithmic decision engine; this would improve co-ordination between supply and demand driving “network effects” which would reduce waiting time and enable cashless transactions (Uber, Citation2019, p. 8). This was often pitched in contradistinction to the outmoded way industry incumbents were organised, who Kalinick argued, represented a form of protectionism against progress and innovation (Bradshaw, Citation2014). Combined, these three aspects of the operating model represented a credible narrative about Uber’s strategy for scaling up, reinforcing pragmatic and moral legitimacy.

In terms of its value proposition, the money-making opportunities presented by network effects formed a central part of an investor-focused narrative around Uber’s ability to scale at speed and the prospects for capital growth (rather than profit) (Uber, Citation2019, p. 1; 8). The network effects that pervade digital platforms add an important peculiarity in that once a firm establishes market leadership, its dominance becomes self-perpetuating (Mazzucato, Citation2018). New ventures generally emerge with low levels of cognitive legitimacy, but network dynamics associated with platforms would confer a first-mover advantage for Uber that would potentially generate future profits through economies of scale, brand allegiance and lock-in (Azhar, Citation2016; Munn, Citation2019). In 2019, Uber claimed it had 91million monthly active customers (Uber, Citation2019, p. 21). The value proposition rested on a narrated business model which would digitise and monetise that which was previously peripheral to taxi service operations: ordering, connecting, and paying. This enabled Uber to curate each digital transaction while taking a cut on each fare – which was a significant departure from traditional business models that seek to maximise revenue per transaction (Scholz, Citation2017).

As noted, legitimacy-building can have a projective element based on nurturing future expectations (Garud et al., Citation2014). Uber stressed the potential of expanding its digital architecture to lever greater network effects. Uber claimed their business model could be rolled out across other forms of logistics, which included food delivery markets to compete with rivals like JustEat (Uber, Citation2019, p. 26), creating dominance of transportation services. They articulated a vision of “infrastructuralization” (Peck & Phillips, Citation2021, p. 77) whereby Uber would sit at the apex of digital intermediation across global markets, not only dictating the terms of trade but also the terrains on which it is practiced. This powerful image provided a strong draw for capital, where the prospect of being an early stage investor in a future Amazon or Apple had significant appeal. Resources flowed to Uber, who raised $25.2bn over 29 funding rounds (Crunchbase, Citation2021a), allowing the company to grow and reinforcing perceptions of pragmatic legitimacy. For a period of time, in Suchman’s terms, Uber benefitted from an alignment of moral and pragmatic legitimacy, so that one supported the other in a self-reinforcing way.

4.3. Uber’s undisclosed practices

As noted, business model narratives require careful framing in order to enrol diverse audiences and secure organisational legitimacy. Yet as Ashforth and BW (Citation1990, p. 177) note, most research on legitimacy examines the means of legitimation but overlooks the conditions under which such means are successful or not. Alongside disclosed business model narratives there can be undisclosed conditions and practices which help the company meet financial expectations and reinforce legitimacy perceptions. Again, to re-emphasise – being “undisclosed” does not here mean they are unknown or outside the public realm, but rather denotes that they are not explicitly articulated as part of a company’s business model, because to do so would undermine the legitimacy of that which businesses choose to disclose (Froud et al., Citation2009). An examination of Uber’s undisclosed practices reveals a reliance on two principles: first, to exploit the benign capital market conditions of the conjuncture by accepting large losses to undercut and displace competition; and second, to operate in legal grey areas and negate the risk of regulatory sanction in order to facilitate growth and become “too big to ban”.

Uber’s first undisclosed practice reflects the opportunities presented by the post-crisis conjuncture of low interest rates and loose credit after the financial crisis. In such a context, Uber’s losses were tolerated by investors in anticipation of future monopoly rents (Langley & Leyshon, Citation2017), as the disappointingly low returns in traditional investments increased appetite for risk elsewhere. This diverted speculative capital into the narrow geographies of Silicon Valley and the Bay Area (McNeill, Citation2016), so that by 2019, the state of California attracted almost as much venture capital investment as China, India, Singapore and Japan combined (Crunchbase, Citation2021b).

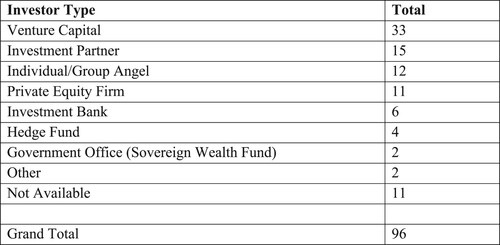

The abundant liquidity and the attraction of technology firms with the potential to become natural monopolies changed both the investor profile and investment behaviours in that area. Venture capital funds showed a greater willingness to fund late – as well as the traditional early-stage investment funding (Erdogan et al., Citation2016), meaning companies could stay private for longer, avoiding stock market pressure for profitability. In 1999, the average US technology company went public after four years; by 2014 it was eleven years (Ritter, Citation2015). In contrast to dotcoms in the 1990s, venture capital investment was also concentrated in a smaller number of firms, meaning investors would compete to finance propositions providing an abundance of liquidity and pushing up valuations (Peck & Phillips, Citation2021). Calculations from a report produced by Ernst and Young (Citation2016) show that average venture capital investment per company was around $19 m – almost double that of the dotcom era; and platform-based firms were valued, on average, two to four times higher than companies with more traditional business models (Libert et al., Citation2016). Uber also benefited from the hybridisation of investment in start-ups outside traditional venture capital (Kenney & Zysman, Citation2016). Investment banks, private equity firms, sovereign wealth funds, and other technology firms invested in Uber (). By 2020 Uber had also raised $7.6bn from debt markets (Crunchbase, Citation2021a).

Figure 1. Frequency of investors in uber by investor type. Source: Crunchbase (Citation2021a).

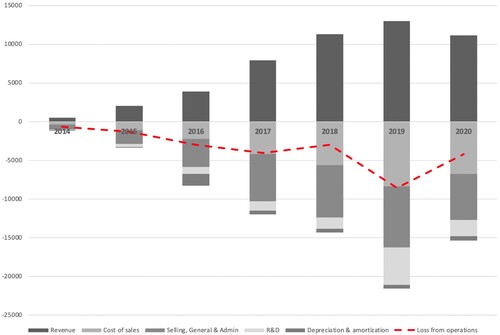

The high levels of liquidity and the tolerance for loss-making meant Uber was able to remain private for longer and lose money for longer. Between 2014 and 2020 Uber had accumulated operating losses of $24.9bn () and reported an accumulated deficit of $23.1bn in their annual report. Of significant cost was the capture of competitor drivers. Uber offered drivers a higher percentage of total fares than those at traditional taxi firms and financial incentives to join the company (Hall & Krueger, Citation2018). This included “excess incentives” where drivers would receive income that exceeded the fare charged to the consumer, as well referral bonuses for recommendations (Uber, Citation2019, p. iii). There is strong evidence that these loss-leading enticements attracted experienced drivers from local taxi firms to fuel expansion, whilst also pushing incumbents out of the market (Hall & Krueger, Citation2018; Waheed et al., Citation2015). These conjunctural supports therefore allowed Uber to undercut and displace incumbents, confirming perceptions about the superiority of the business model articulated by Kalanick and others, reinforcing organisational legitimacy.

Figure 2. Uber’s net revenues and operating losses (US$m). Source: Crunchbase, Uber (Citation2019), S&P Global Insights.

Uber’s second undisclosed practice relates to the more complex and fraught organisational practices which produce the conditions for pragmatic legitimacy. If rapid growth creates the conditions for Uber’s pragmatic legitimacy because it provides a pathway to achieving a monopoly position, attaining rapid growth may mean engaging in practices which potentially challenge their moral legitimacy. Ordinarily, adherence to legal norms is viewed as essential if new ventures plan to appear legitimate to stakeholders (Delmar & Shane, Citation2004). But Uber operates in regulatory grey areas (Cherry, Citation2016), engaging in practices of “regulatory arbitrage” (Davidson & Infranca, Citation2015), openly challenging incumbent rules and structures. Uber has achieved scale partly by claiming that traditional taxi regulations do not apply, provoking regulatory “flashpoints” in different spatial contexts, including (unfair) competition, employment and labour issues, social policy and social benefit concerns, taxation avoidance, and consumer safety (Thelen, Citation2018). As pressures for reform become a matter of political concern, non-compliance or outright confrontation carry risks to Uber’s moral legitimacy. Yet the faster Uber grows and the more competitors they put out of business, the greater the social costs of regulatory sanction or licence withdrawal to consumer welfare, making Uber “too big to ban” (Pollman & Barry, Citation2017). Uber was – and arguably still is – therefore, in a high-stakes game: to expand quickly it must operate in legal grey areas or defy existing regulation because monopolisation of territory is critical (Munn, Citation2019); but this exposes it to reputational damage and potential regulatory sanction which could impose costs or restrain future growth to the detriment of its pragmatic legitimacy.

Uber, like other technology companies, achieves scale by passing on cost, responsibility and risk to their suppliers (Bergvall-Kåreborn & Howcroft, Citation2013). In Uber’s case, this includes classifying drivers as self-employed workers, sidestepping the contractual responsibilities and costs associated with being an employer. Drivers are also required to provide their own vehicle, avoiding fleet management obligations. Contractually and operationally, these practices allow Uber to avoid the frictions which can slow growth. To manage potential reputational risks on driver quality, Uber embeds algorithmic management within its digital infrastructure (Lee et al., Citation2015). This enables the digital control of workflow, which restricts driver decision-making, producing power and information asymmetries between drivers and the platform (Calo & Rosenblat, Citation2017). Uber is, therefore, able to achieve scale by avoiding the regulations that might hamper growth, while managing the potential reputation risks of extending the driver pool through digitised bureaucratic control systems (see Leoni & Parker, Citation2019 for similar arguments about AirBnB).

The self-employment categorisation leaves drivers both dependable and disposable (Hyman, Citation1987, p. 43). In terms of dependability, by offering drivers joining incentives and by claiming a lower share of driver fares, Uber has attracted large numbers of drivers which have led to the widespread closure of local taxi firms (Hall & Krueger, Citation2018; Waheed et al., Citation2015). The lack of alternative firms creates dependence, and provides Uber with an option to raise fares at a later date (Munn, Citation2019). But drivers can become disposable if the algorithmic management system suspends or terminates driver accounts for activities such as “excessive” cancellations or low customer ratings (Uber, Citation2021). The contractual relation is therefore thin, providing Uber with the option of withdrawing from more challenging regulatory markets without incurring significant legacy costs. This disposability illustrates Uber’s heterarchical and hierarchical structure: drivers are beholden to the power of “evaluative infrastructures” – distributed mechanisms of accountability and control such as customer ratings – in order to maintain their positionality within the platform network (Kornberger et al., Citation2017), but monitoring, performance management and sanctioning processes are highly centralised, echoing traditional modes of governance, power and control (Leoni & Parker, Citation2019).

The political risks associated with operating in legal grey areas with this level of instrumentality are high. Uber has therefore invested heavily in its lobbying activity (McNeill, Citation2016) as disclosed recently in the Uber files leak. This extended to the mass mobilisation of consumers, who were encouraged to register their disapproval towards regulatory agencies which attempt to impose sanctions (Thelen, Citation2018). Having the power to assemble a support coalition became especially evident in 2020 when a ballot of voters in California passed a measure based on Prop 22 (authored by Uber, Lyft, Doordash and Instacart) that classified gig workers as contractors without access to standard employment rights (Paul, Citation2020). Platform corporations invested more than $200 m in the campaign, indicating their commitment to resisting pressures for regulatory change. While becoming “too big to ban” carries negative implications for moral legitimacy, the enrolment of consumer support helps neutralise those concerns.

5. Discussion: the challenges to Uber’s legitimacy

Having explained how the interaction of disclosed and undisclosed elements nurtures organisational legitimacy in particular contexts, this section will now discuss the challenges to Uber’s legitimacy since 2017 within this same framework.

5.1. Challenges to moral legitimacy

While moral legitimacy is based on a positive normative evaluation, illegitimacy can emerge when a disparity arises between the apparent social values of the firm and the wider norms of society (Elsbach & Sutton, Citation1992). While business models may serve as legitimacy-enhancing narratives, the revealing of undisclosed practices can disrupt the balance of pragmatic and moral legitimacy. In 2017, growing public discontent with platforms generally led to a “techlash”, placing them in an increasingly vulnerable position (Van Dijk, Citation2020) as concerns surrounding disinformation, tax evasion, privacy scandals, anti-trust security leaks, hate speech and an undermining of employment law began to emerge. Critical audiences began to focus on Uber and organise around a “#DeleteUber” social media campaign. Uber acknowledged that this action had a profound effect on perceptions of their moral legitimacy and was likely to damage their business:

Our business performance was negatively impacted in early 2017 when we faced many challenges, including the #DeleteUber campaign that encouraged platform users to delete our app and cease use of our offerings. Later in 2017, allegations of discrimination, harassment, and retaliation in the workplace adversely impacted our reputation and further encouraged platform users to cease use of our offerings. (Uber, Citation2019, p. 107)

Despite these declarations of intent, Uber’s resistance to regulatory conformity continued. Having appealed four legal challenges over five years in the UK, in February 2021 the UK Supreme Court finally ruled that Uber drivers are to be classed as workers as opposed to self-employed and are thus entitled to holiday pay, a company pension and the national minimum wage (Naughton, Citation2021). This was followed in December 2021 by a new European Commission proposal to recognise drivers as “employees” entitled to a minimum wage, holiday pay, unemployment and health benefits. These developments will have a significant impact on Uber’s operating costs, and has far-reaching implications for platforms generally (Venkataramakrishnan & Croft, Citation2021).

Moral legitimacy has also been undermined through Uber’s poor handling of controversies. As Begkos and Antonopoulou (Citation2020) note, platform companies (and users) have manipulated technologies that measure and manage digital platform performance, in order to fabricate metrics and blur others’ evaluations. For example, Uber has been accused of gaming regulations using its software tool Greyball. Uber created a fake version of the app populated with “ghost cars” in order to deceive law enforcement agencies in situations where it has violated regulations (Calo & Rosenblat, Citation2017). This software was authorised by Uber’s legal department and applied in various geographies (Wong, Citation2017). Similarly, transparency concerns surfaced when it became apparent that hackers had breached the personal data of 57 million Uber customers/drivers. Uber failed to notify individuals and regulators and instead paid the hackers $100,000 on condition they would keep quiet (Newcomer, Citation2017). Further tensions have been amplified by media accounts of corporate culture. A class action concerning gender and racial discrimination, sexual harassment and problematic workplace practices in Uber’s headquarters, resulted in a payment of $10 m to 285 women and 135 men of colour for financial and emotional harm (Mishra & Raman, Citation2018).

These events highlight how even post-disciplinary, “gamified” mechanisms of control can be treated with mistrust and undermine legitimacy when accountability fails (Chapman et al., Citation2021). They have led to a growing public perception that the company has a disregard for rules and regulations, raising questions about the morality of the means by which Uber pursues growth. This illustrates an important tension: operating in grey areas in order to reach a “too big to ban” tipping point may, paradoxically, attract greater regulatory scrutiny which makes that aim improbable. Uber identify this as a fundamental problem: regulations that permit or limit our ability to provide Ridesharing in certain markets impact our financial performance (Citation2019, p. 107). The problem for Uber is that the practices associated with these social and moral conflicts are critical to fuelling the growth that underpins its pragmatic legitimacy. And without pragmatic legitimacy, the company may struggle to raise the investments that support its losses.

5.2. Challenges to pragmatic legitimacy

Investor enthusiasm for Uber waned amidst the various challenges to the company’s moral legitimacy and public pressure for regulatory change. In November 2017, Uber faced difficulties in raising equity funding at a value that would continue its trajectory of share price growth. A so-called “down round” – the situation where a private company offers additional shares at a lower price than in previous financing rounds – is feared by many fast-growing start-ups with no track record of profitability. Down-rounds have the capacity to undermine pragmatic legitimacy because when valuations are based upon expectations of future profitability, the plateauing of that trajectory signals that the firm is over-priced, its prospects are diminishing or it is no longer “desirable”. Uber consequently allowed a Softbank-led consortia to buy shares held by others at a discount provided they bought a smaller number of new shares at Uber’s proposed higher price in order to keep the company’s trajectory of share price rises intact on paper (Waters & Hook, Citation2017). In 2019 when Uber sought funding from the public markets via an IPO, the valuation price mooted of between $80.5bn and $91.5bn was substantially below the $100bn-$120bn expected by some commentators (Bond et al., Citation2019). Its post-IPO performance was amongst the worst of any large firm in history, with its valuation falling 17.6 percent in the two days after the IPO (Bullock et al., Citation2019).

These events show that moral and pragmatic legitimacy are not necessarily distinct (Palazzo & Scherer, Citation2006) and can be inseparable in particular contexts. The visibility of Uber’s socially and morally challenging practices and impending sanctions undermine the visions of a financial future which underpin today’s investment flows. For loss-making companies like Uber this is problematic because they rely on capital market investment to recover their costs and remain solvent. Changes in economic conditions can alter market perceptions of the balance of investment risks and rewards around particular types of companies. There are various concerns that Uber is part of a larger valuation bubble around platform businesses (Kenney & Zysman, Citation2016) and that investors may not be willing to continue to write bigger checks for platforms with high “burn rates” in the future (Langley & Leyshon, Citation2017). The fate of other platform firms such as WeWork and Theranos show that the combination of accumulated losses and unclear route to profit can mean can lead to sudden collapse once investor sentiment changes and they decide to turn off the taps.

5.3. Challenges to cognitive legitimacy

McDaid et al. (Citation2019) highlight the challenge of managing reputation in a platform context where online ratings and reviews proliferate, and where bad reviews may carry more weight than good ones. Cognitive legitimacy occurs when a company becomes synonymous with the service they are providing, so that their presence is taken-for-granted. As the interrelation between pragmatic and moral legitimacy is increasingly challenged, the object to which Uber’s cognitive legitimacy was attached also became tainted. Uber originally tapped into a story about the sharing economy as an alternative to traditional corporations, illustrating “the ways in which organizations manipulate and deploy evocative symbols in order to garner societal support” (Suchman, Citation1995, p. 572). However, by evoking that connection Uber aligned itself with other platform businesses who were also subject to moral challenges (e.g. Airbnb, Deliveroo, Lyft) revealing sharing economy companies as intensifying some of worst features of global capitalism (Schor, Citation2020).

Cognitive legitimacy exists regardless of whether knowledge of the organisation is positive, negative or neutral (Rentschler et al., Citation2021; Suchman, Citation2005). Uber’s global expansionist approach rapidly generated cognitive legitimacy, but as attention was drawn to undisclosed practices, some stakeholders began to question Uber’s espoused egalitarian commitments. According to Scholz (Citation2017, p. 1), no-one could have believed that the ideological bubble of the sharing economy would deflate so quickly. As a result, Uber became increasingly associated with the much maligned gig economy and “Uberization” became a euphemism for exploitative working conditions (Fleming et al., Citation2019). Uber’s name thus became synonymous with a series of unwanted norms linked to its undisclosed practices, but which were nevertheless difficult to relinquish because they were critical to Uber’s anticipated market dominance and the possibility of achieving “winner-takes-all” status (Bradshaw et al., Citation2019).

Uber’s embodiment of norms it did not wish to be associated with also extended to its leadership. Research has shown that cognitive legitimacy extends beyond an understanding of the product/service to include perceptions of how the organisation is run and managed (Shepherd & Zacharakis, Citation2003; Suchman, Citation2005). In keeping with the imagery associated with tech CEOs, Kalanick initially traded on his popularity as a “hypermuscular entrepreneur” (Suddaby et al., Citation2017), but the darker side of Uber’s “bro culture” was revealed with the release of a video where Kalanick harangues an Uber driver for questioning pay rates. Acutely aware that corporate misconduct could destabilise legitimacy and create shareholder anxiety, key investors lobbied for the CEO’s resignation (Munn, Citation2019). Kalanick’s replacement (Dara Khosrowshahi) was intent on minimising further reputational breaches and their potential to undermine legitimacy:

The truth is that there is a high cost to a bad reputation. It really matters what people think of us, especially in a global business like ours … .It’s critical that we act with integrity in everything we do, and learn how to be a better partner to every city we operate in. we will show that Uber is not just a really great product, but a really great company that is meaningfully contributing to society, beyond its business and its bottom line. (Dara Khosrowshahi, cited in Balakrishnan, Citation2017)

6. Conclusion

This paper has analysed the case of Uber and its business model. It has argued that in the modern firm, legitimacy is pursued through the development of business model narratives which articulate an economic and moral vision to stakeholders whose interests diverge. Business model narratives involve careful framing and so foreground particular representations (the disclosed) whilst omitting others (the undisclosed). Consequently, they are prone to challenge and revision when undisclosed elements become points of social and political mobilisation or when changing conjunctural contexts render their articulation implausible.

As a new venture seeking different resources while appealing to multiple stakeholders, Uber has struggled to adapt to shifting legitimacy evaluations. While mainstream scholarship tends to view legitimation in absolute terms as either present or absent (Fisher, Citation2020), this study highlights its dynamic nature, given the thresholds of legitimacy are temporally and contextually contingent. This study has shown how Uber’s symbolic association with the sharing economy, deemed central to its disclosed business model at its inception, can later turn into a disadvantage when viewed simply as a more extreme version of deregulated free markets (Scholz, Citation2017) and so assumes negative, de-legitimizing connotations. As Uber has matured, the fluctuating legitimacy evaluations have become more stringent and it faces something of a Catch-22: many of the company’s legally-ambiguous and morally-challenging undisclosed practices have been rendered visible, which have invited sanctions that erode investor enthusiasm and thus pragmatic legitimacy. This pragmatic legitimacy is also dependent on maintaining growth rates that rely on continuing those same undisclosed practices, which leaves them morally exposed.

This paper provides two contributions. First, it offers an antidote to the technologically-determinist view that the market dominance of platform business models is inexorable and arises as the outcome of irrepressible technological developments that will inevitably displace incumbents. Our revisionist work develops critical accounting work on the tensions and limits of platform accountability (Begkos & Antonopoulou, Citation2020; Chapman et al., Citation2021; Kornberger et al., Citation2017; Leoni & Parker, Citation2019; McDaid et al., Citation2019) to explore the wider contradictions of platform capitalism itself. The generalisability of the case of Uber to other platform companies could be questioned, but emerging evidence suggests it has wider significance: many platforms rely on profit-less growth by exploiting legal grey areas and so are susceptible to similar tensions between moral and pragmatic legitimacy. In 2020, the collapse of WeWork, one of the world’s largest unicorns, demonstrates how diminishing legitimacy can rapidly lead to the withdrawal of investor funding, a downward legitimacy spiral and collapse (Brown & Farrell, Citation2021). In 2021 Deliveroo became the worst IPO in London’s history, losing £2bn of its £7.6bn valuation on the opening day of trading following concerns about the implications of Uber’s UK Supreme Court ruling on similar businesses (Bradshaw & Mooney, Citation2021). Others have also noted the instability of the conjunctural condition of platform capitalism (Peck & Phillips, Citation2021; Srnicek, Citation2017) and the inherent limitations of the platform business model, which are largely unworkable and unsustainable in practice (Fleming et al., Citation2019). The credit conditions, expectations of future cashflows and narratives of transformation that sustained the bull market in new technology stocks and made Uber’s stated business model appear plausible, seem unlikely to continue. The disruption and increasing market concentration created by a small number of predatory platforms (Cusumano et al., Citation2020; Kenney et al., Citation2019) means that when some eventually cease to exist, the fallout from the “colonizing effects” (Peck & Phillips, Citation2021, p. 79) will have long-term ramifications for both sectors and jobs.

Our second contribution contextualises the literature on business models as narratives (Magretta, Citation2002) within Suchman’s (Citation1995) work on organisational legitimacy. This extends critical accounting research on business models (Andersson et al., Citation2010; Feng et al., Citation2001; Froud et al., Citation2009; Gleadle & Haslam, Citation2010; Haslam et al., Citation2014) by approaching them as: a narrativized account of a firm’s logic, operating plan and value proposition, designed to engage, convince, and enrol a diverse audience with the aim of securing organisational legitimacy. In contrast to the predominantly diagnostic or normative approaches in business model literature, this allows us to consider the fragilities that can arise when undisclosed practices that are central to a firm’s financial viability, but which fall outside of the narrativized frame of the business model, are made visible by critical audiences. The examination of both the disclosed and the undisclosed elements provides analytical power that is largely absent in mainstream analysis and avoids repeating the mistakes of the 1990s where technology companies were seen as exemplars of business model innovation, yet lost legitimacy rapidly in 2000. This research offers a more critical interrogation, enhancing the business model concept, and complementing the small but growing literature on narrative and numbers analysis (Froud et al., Citation2006).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editor and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive comments. The paper is, in our view, much improved as a result of their recommendations. We would also like to thank our funders - the Independent Social Research Foundation (ISRF) and Danmarks frie forskningsfond (DFF) whose generous grants gave us the time and intellectual space to write this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The Factiva database includes the main international financial newspapers, such as the Financial Times, Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg, Reuters, broadsheets such as The Times, New York Times as well as many trade and industry journals.

2 Crunchbase specialises in start-up and new technology companies, providing data on their funding history, investment activities, and acquisition trends. As a private company, Uber released relatively little financial data – Crunchbase was perhaps the only database presenting detailed accounting information up until the release of the S-1 document.

3 An official Uber statement explained, for example: “We believe ridesharing brings huge benefits to cities – including less congestion, less environmental impact, more consumer choice and greater economic opportunities” (Vasagar, Citation2014).

4 “The Company’s principal activities are to develop and support proprietary technology applications (“platform(s)”) that enable independent providers of ridesharing services (“Driver Partner(s) … collectively the Company’s ‘Partners’, to transact with ‘Rider(s)’ (for ridesharing services)” (Uber, Citation2019, p. F11).

5 “In addition to powering movement for riders, our platform powers opportunity for Drivers, fueling the future of independent work by providing Drivers with a reliable and flexible way to earn money” (Uber, Citation2019, p. 1).

6 The intertwining of moral and pragmatic legitimacy can be found in statements such as, “we aim to provide everyone, everywhere on our platform with access to a safe, reliable, affordable, and convenient trip within a few minutes of tapping a button … We believe that Personal Mobility represents a vast, rapidly growing, and underpenetrated market opportunity” (Uber, Citation2019, p. 2); or in their revised mission aimed at building bridges with regulators and other stakeholders, based around eight cultural norms, including We do the right thing. Period, We Celebrate Differences and We Value Ideas Over Hierarchy (Uber, Citation2019, p. 8).

7 At its most extreme, Uber drew on the legal outcome of Quashie vs Stringfellows Restaurants Ltd, arguing that drivers were more like lapdancers than traditional cab drivers insofar as the individual driver paid Uber a fee to work, which enabled them to negotiate and earn payments from clients for services provided (Uber BV v Aslam and others Citation2019).

8 See Uber’s assertion that, “Driving for money gave people freedom and flexibility to make extra cash” Again this pragmatic legitimacy building narrative was coupled with moral legitimacy arguments: “The online app connected neighborhoods that were underserved by taxis. Sober Uber drivers would mean safer roadways, as drunk drivers would be kept off the road at night. If Uber were broadly used, people wouldn't need to own cars at all, reducing roadway congestion and emissions” (Davis et al., Citation2022).

9 “Increasing scale, creating category leadership and a margin advantage. We can choose to use incentives, such as promotions for Drivers and consumers, to attract platform users on both sides of our network” (Uber, Citation2019, p. 8).

References

- Aldrich, H. E., & Fiol, C. M. (1994). Fools rush in? The institutional context of industry creation. The Academy of Management Review, 19(4), 645–670. https://doi.org/10.2307/258740

- Amit, R., & Zott, C. (2001). Value creation in E-business. Strategic Management Journal, 22(6-7), 493–520. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.187

- Andersson, T., Gleadle, P., Haslam, C., & Tsitsianis, N. (2010). Bio-pharma: A financialized business model. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 21(7), 631–641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2010.06.006

- Ashforth, B. E., & BW, G. (1990). The double-edge of organizational legitimation. Organization Science, 1(2), 177–194. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1.2.177

- Azhar, A. (2016, January 28). Beware of the ‘blitzscalers’. Financial Times.

- Balakrishnan, A. (2017). Uber CEO on losing London license: “There is a high cost to a bad reputation” [online]. CNBC. Retrieved April 17, 2021, from https://www.cnbc.com/2017/09/22/uber-ceo-email-weighs-in-on-fight-with-london-regulators.html.

- Barry, D., & Elmes, M. (1997). Strategy retold: Toward a narrative view of strategic discourse. The Academy of Management Review, 22(2), 429–452. https://doi.org/10.2307/259329

- Begkos, C., & Antonopoulou, K. (2020). Measuring the unknown: Evaluative practices and performance indicators for digital platforms. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 33(3), 588–619. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-04-2019-3977

- Bergvall-Kåreborn, B., & Howcroft, D. (2013). The Apple business model: Crowdsourcing mobile applications. Accounting Forum, 37(4), 280–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2013.06.001

- Bitektine, A. (2011). Toward a theory of social judgments of organizations: The case of legitimacy, reputation, and status. The Academy of Management Review, 36(1), 151–179. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0382

- Bond, S., Bullock, N., & Bradshaw, T. (2019, April 25). Uber seeks $91.5bn valuation in this year’s largest IPO. Financial Times.

- Botsman, R. (2015). The changing rules of trust in the digital age. Harvard Business Review. October edition.

- Bradshaw, T. (2014, May 9). Lunch with the FT: Travis Kalanick. Financial Times.

- Bradshaw, T., Bullock, N., & Bond, S. (2019, April 12). Uber Aims to Maintain Heavy Spending to Keep Rivals at Bay’. Financial Times.

- Bradshaw, T., & Mooney, A. (2021, March 31). Disaster strikes as Deliveroo becomes ‘worst IPO in London’s history. Financial Times.

- Brown, E., & Farrell, M. (2021). The cult of we: WeWork and the great start-up delusion. Harper Collins.

- Bullock, N., Bond, S., & Georgiadis, P. (2019, May 13). Uber extends slide on second day of trading Financial Times.

- Calo, R., & Rosenblat, A. (2017). The taking economy: Uber, information, and power. Columbia Law Review, 117(6), 1623–1690.

- Cederström, C., & Fleming, P. (2016). On bandit organizations and their (il)legitimacy: Concept development and illustration. Organization Studies, 37(11), 1575–1594. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840616655484

- Chapman, C., Chua, W. F., & Fiedler, T. (2021). Seduction as control: Gamification at Foursquare. Management Accounting Research, 53, 100765.

- Cherry, M. A. (2016). Beyond misclassification: the digital transformation of work. Comparative Labor Law and Policy Journal, http://ssrn.com/abstract = 2734288.

- Chesbrough, H., & Rosenbloom, R. S. (2002). The role of the business model in capturing value from innovation: evidence from Xerox Corporation’s technology spin-off companies. Industrial and Corporate Change, 11(3), 529–555. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/11.3.529

- Chua, W. F. (1986). Theoretical constructions of and by the real. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 11(6), 583–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(86)90037-1

- Crunchbase. (2021a). Crunchbase database. https://www.crunchbase.com/.

- Crunchbase. (2021b). The State Of Global Venture Funding During COVID-19 [online]. http://about.crunchbase.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Crunchbase_State_of_Funding_Covid_FINAL.pdf.

- Cusumano, M., Yoffie, D. B., & Gawer, A. (2020). The future of platforms. MIT Sloan Management Review, 61(3), 46–54.

- Davidson, N. M., & Infranca, J. J. (2015). The sharing economy as an urban phenomenon. Yale Law and Policy Review, 34, 215–280.

- Davies, H., Goodley, S., Lawrence, F., Lewis, P., O’Carroll, L., & Cutler, S. (2022, July 11). Uber broke laws, duped police and secretly lobbied governments, leak reveals. The Guardian.

- Davis, A., Noack, R., & MacMillan, D. (2022, July 11). Uber leveraged violent attacks against its drivers to pressure politicians. Washington Pos.

- Deegan, C. (2002). Introduction: The legitimising effect of social and environmental disclosures – a theoretical foundation. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 15(3), 282–311. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513570210435852

- Deegan, C., Rankin, M., & Tobin, J. (2002). An examination of the corporate social and environmental disclosures of BHP from 1983-1997: A test of legitimacy theory. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 15(3), 312–343. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513570210435861

- Deegan, C. M. (2019). Legitimacy theory: Despite its enduring popularity and contribution, time is right for a necessary makeover. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 32(8), 2307–2329.

- Delmar, F., & Shane, S. (2004). Legitimating first: organizing activities and the survival of new ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, Evolutionary approaches to entrepreneurship: Honoring Howard Aldrich, 19, 385–410.

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(April), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

- Doganova, L., & Eyquem-Renault, M. (2009). What do business models do? Innovation devices in technology entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 38(10), 1559–1570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2009.08.002

- Elsbach, K. D., & Sutton, R. I. (1992). Acquiring organizational legitimacy through illegitimate actions: A marriage of institutional and impression management theories. Academy of Management Journal, 35(4), 699–738. https://doi.org/10.2307/256313

- Erdogan, B., Kant, R., Miller, A., & Sprague, K. (2016). Grow fast or die slow: Why unicorns are staying private. McKinsey and Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/high-tech/our-insights/grow-fast-or-die-slow-why-unicorns-are-staying-private.

- Ernst and Young. (2016). Back to reality: EY global venture capital trends 2015. https://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/ey-global-venture-capital-trends-2015/%24FILE/ey-global-venture-capital-trends-2015.pdf.

- Feng, H., Froud, J., Johal, S., Haslam, C., & Williams, K. (2001). A new business model? The capital market and the new economy. Economy and Society, 30(4), 467–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085140120089063

- Fisher, G. (2020). The complexities of new venture legitimacy. Organization Theory, 1(2), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/2631787720913881

- Fisher, G., Kotha, S., & Lahiri, A. (2016). Changing with the times: An integrated view of identity, legitimacy, and new venture life cycles. Academy of Management Review, 41(3), 383–409. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2013.0496

- Fleming, P., Rhodes, C., & Yu, K.-H. (2019). On why Uber has not taken over the world. Economy and Society, 48(4), 488–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2019.1685744

- Foster, W. M., Coraiola, D. M., Suddaby, R., Kroezen, J., & Chandler, D. (2017). The strategic use of historical narratives: a theoretical framework. Business History, 59, 1176–1200.

- Froud, J., Johal, S., Leaver, A., Phillips, R., & Williams, K. (2009). Stressed by choice: A business model analysis of the BBC. British Journal of Management, 20(2), 252–264. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2008.00564.x

- Froud, J., Johal, S., Leaver, A., & Williams, K. (2006). Financialization and strategy: Narrative and numbers. Routledge.

- Froud, J., Johal, S., Leaver, A., & Williams, K. (2014). Financialization across the Pacific: Manufacturing cost ratios, supply chains and power. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Special Issue on Critical Perspectives on Financialization, 25, 46–57.

- Garud, R., Schildt, H. A., & Lant, T. K. (2014). Entrepreneurial storytelling, future expectations, and the paradox of legitimacy. Organization Science, 25(5), 1479–1492. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2014.0915

- Georgiou, O., & Jack, L. (2011). In pursuit of legitimacy: A history behind fair value accounting. The British Accounting Review, 43(4), 311–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2011.08.001

- Gleadle, P., & Haslam, C. (2010). An exploratory study of an early stage R&D-intensive firm under financialization. Accounting Forum, 34(1), 54–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2009.10.002

- Glynn, M. A., & Marquis, C. (2004). When good names go bad: Symbolic illegitimacy in organizations. In C. Johnson (Ed.), Legitimacy processes in organizations, research in the sociology of organizations (pp. 147–170). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Habermas, J. (1973). Legitimation crisis. John Wiley and Sons.

- Hall, J. V., & Krueger, A. B. (2018). An analysis of the labor market for Uber’s driver-partners in the United States. ILR Review, 71(3), 705–732. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793917717222

- Haslam, C., Butlin, J., Andersson, T., Malamatenios, J., & Lehman, G. (2014). Accounting for carbon and reframing disclosure: A business model approach. Accounting Forum, 38(3), 200–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2014.04.002

- Hyman, R. (1987). Strategy or structure? Capital, labour and control. Work, Employment and Society, 1(1), 25–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017087001001004