?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

There is a research gap on understanding gender equality issues in the OR discipline, and on the role of gender in OR participation and career progression. We apply a gender lens to the literature on the history of OR, reflecting on the origins of OR, the OR community, and the theory, methods and practice of OR. A gender lens aims to uncover hidden gender dimensions to bring gender issues into sharper focus. The review shows that women are largely invisible in the recorded history of OR. We use a survey instrument to capture the current OR community and extract insights on their careers by gender. Using a decision tree to understand factors that affect participation in OR, our findings are consistent with other studies: women perceive barriers to their participation and career progression, but the barriers are not as apparent to their male peers. Our paper offers novel contributions including a reflection on the history of OR through a gender lens, insights on the role of gender in OR careers, and a critical discussion of our findings. We aim to stimulate a conversation and encourage a discussion on the next steps toward innovative and cross-disciplinary research and applications at the gender/OR nexus.

1. Introduction

There are several characteristics which may be a source of discrimination. Complex interaction and intersection of age, marital status, disability, race, religion, sex or sexual orientation can result in reduced opportunities and unequal outcomes for an individual. Many organisations recognise the potential benefits from the diverse perspectives of their members or employees. However, there is a significant challenge to achieve meaningful Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) to reap those benefits.

In this paper we focus on gender equality. There is ample evidence of a gender pay gap (GPG), and under representation of women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) disciplines (European Commission, Citation2021). We do not currently have evidence of how Operational Research (OR) fares in comparison to other disciplines, or how gender equality issues manifest in practice for women in OR. Our study makes several important contributions to the OR literature and introduces the as yet unexplored gender/OR nexus.

1.1. History of Operational Research

OR has its origins in the optimisation of radar and military operations in the 1930s. Since then it has developed into a mature discipline anchored in mathematics coupled with soft techniques to model and solve real world problems. Applications span energy, humanitarian, healthcare, logistics, production, risk and revenue management, supply chain, and transport problems to name a few. The spread of, and connection to application is perhaps the most distinguishing feature of OR, compared to theory-driven pure mathematical or engineering problem structuring and solution approaches. The multi- and intersecting disciplinarity of OR can cause confusion about its identity (Ormerod, Citation1996). There has been much discussion on whether OR is a science, or a technology (Mingers Citation2000), or a core element of modern management ecosystems (Mortenson et al., Citation2015).

Learned societies such as the UK OR Society aim to promote the OR discipline and support professional operational researchers, both academic and practitioners. The UK OR Society is the longest established OR society and describes OR as “a scientific approach to the solution of problems in the management of complex systems that enables decision makers to make better decisions” (ORS, Citation2023). EURO, the Association of European Operational Research Societies, promotes the subject of OR across Europe and uses a similar definition as the UK OR Society (EURO, Citation2023). INFORMS, the Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences promotes decision-making disciplines, which include OR, and describes OR as “the scientific process of transforming data into insights for making better decisions” (Gorman & Klimberg, Citation2014; INFORMS, Citation2023).

The lack of distinction between the definitions of OR and analytics is noted in Mortenson et al. (Citation2015). OR overlaps and intersects with disciplines such as mathematics, industrial engineering, operations management and computer science. For this reason, OR academic departments are found in different faculties depending on local university structures. Similarly, OR functions may be embedded in multiple business units or centralised within an IT department, and may not even be named or recognised as OR departments.

Historically, the developmental direction of OR was closely related to the needs of major industry groups, such as coal, steel or energy. The military and transport sectors have also played important roles in the development of OR, and in recent years, healthcare has emerged as an active area. OR has been successful in dealing with short term tactical problems such as unit commitment scheduling (Saravanan et al., Citation2013), and longer term strategic problems such as electrical or gas network design. Petropoulos et al. (Citation2023) give an overview of the current state of OR, describing a broad range of methodologies to tackle a variety of applications. Globalisation, the decline of heavy industry and the rise of digitalisation, economic crises, and the war in Ukraine have all been features of the twenty first century which affect the demand for skilled workers and the associated development and practice of OR. The evolving symbiotic relationship between OR and analytics, and challenges to OR from AI and analytics are addressed in Burger et al. (Citation2019); Hindle et al. (Citation2020); Mortenson et al. (Citation2015); Ormerod (Citation2021). Burger et al. (Citation2019) note the difference between automated AI decision-making systems and human OR assisted decision-making and argue for the development of hybrid OR/AI approaches to generate actionable insights in a technology and data rich society. Changing demands and the need for sustainability mean that heavy industry now need to explicitly recognise connections to broader “wicked” societal problems. This has implications for the practice of OR.

In this paper, we explore the history of OR through a gender lens. Applying a gender lens means to analyse a policy or problem for implicit or explicit gender perspectives or impacts. It means exploring if a problem statement or policy captures the differential needs of men and women and analysing whether recommended solutions or policy initiatives have a positive or negative impact on gender equality. We review the history of OR with respect to gender to bring gender related dimensions into sharper focus.

Many in the OR community are already aware of gender equality conversations. However, many people, both women and men, are unaware of the gender related factors or dimensions that are hidden in aspects of daily life, how society operates and decision making in general. There are interesting hidden connections between gender and OR in what is called the gender/OR nexus. By applying a gender lens we bring gender dimensions at the gender/OR nexus and in the history of OR into sharper focus.

We also reflect on current gender equality issues in the OR community. We first provide a brief introduction to gender equality issues to help set the context of our study.

1.2. Introduction to gender equality

Gender equality means “that women and men, girls and boys, have equal conditions, treatment and opportunities for realising their full potential, human rights and dignity, and for contributing to (and benefitting from) economic, social, cultural and political development” (UNICEF, Citation2017). The United Nations introduced a Gender Inequality Index (GII), which spans three dimensions of health, education and labour force participation to measure gender equality, (Seth, Citation2009). A high GII indicates high inequality between women and men. Such indices and metrics offer quantitative tools to capture gender equality dimensions and create awareness by rendering explicit gender gaps.

Focusing on participation in the labour force, women earned on average 13% less per hour than men in the EU in 2020. This has only changed minimally since 2010. There are differences per member state and region, industry sector and employment status. On the remuneration side, the Gender Pay Gap (GPG), which measures the difference in average wage between men and women (EUROSTAT, Citation2016), is partly explained by women working part-time, in lower paid jobs, and not making as much career progression as male counterparts. Women also carry a disproportionate burden of unpaid work which impacts opportunities to engage in paid economic activities (European Commission, Citation2020). New EU directives on obligatory pay transparency measures will help to clarify pay rates and quantify the GPG in EU member states.

The EU has set out a gender equality strategy for the years 2020–2025 which aims to make concrete progress on gender equality in the EU (European Commission, Citation2020). Key objectives include challenging gender stereotypes; closing gender gaps in the labour market; achieving equal participation across different sectors of the economy; and achieving gender balance in decision-making and politics. The strategy is implemented through gender mainstreaming which is a theoretical and practical framework to embed a gender dimension into all practices, processes and policies.

Gender equality actions need to make progress across all sectors of society by increasing awareness, and addressing existing barriers and stereotypes. For example, within academia, a report commissioned by the government of Ireland on gender in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) notes that: “The reason why women are not found in the same proportion as men in the most senior positions is not because women are not talented or driven enough to fill these roles, it is because numerous factors within HEIs, conscious and unconscious, cultural and structural, mean that women face a number of barriers to progression, which are not experienced to the same degree by their male colleagues; systematic barriers in the organisation and culture within higher education institutions mean that talent alone is not always enough to guarantee success” (HEA, Citation2016), page 9.

García-González et al. (Citation2019) explore the research landscape in Spain and find that gender inequalities are perceived by women researchers in their workplace but are not noticed by their male colleagues; the authors also point out that perception and awareness may be critical to close the gender gap. From an industry perspective, we note a similar finding in a survey of workers in the energy sector in 2019 where 75% of women perceive the existence of gender related barriers, while only 40% of men do (IRENA, Citation2019). Guyan and Oloyede (Citation2020) look at EDI challenges and interventions in the UK research and innovation (R&I) sector and suggest that approaches from the private sector such as returnship (ie, a programme to support those returning from an extended leave or career break to resume and/or restart their career) and executive sponsorship (ie, pairing an employee with a senior leader(s)) might be useful to support women in R&I.

Overall, the lack of awareness of gender inequality among men in the research and energy sectors is a concern. It is important for men, who occupy many of the positions of power and influence in STEM, to become aware of gender inequalities and participate in driving change.

1.3. OR and gender equality

There is a research gap on the status of gender in the OR discipline. Initiatives in OR with respect to gender include INFORMS Women in OR/MS (WORMS) founded in 1995, the UK Women in OR & Analytics Network (WORAN) founded in 2018, and the EURO Women in Society: Doing Operational research and Management science (WISDOM) Forum established in March 2020. The three groups share broadly similar objectives to support women in OR. In this paper we focus on WISDOM which is a EURO Forum (general interest group) founded following the growing interest in promoting inclusion within the OR discipline at EURO conferences eg, Women in Science (EURO, Citation2018), and Women in OR (EURO, Citation2019). The WISDOM Forum aims to provide a platform to support, empower and encourage the participation of ALL genders in OR within EURO through the following actions (WISDOM, Citation2020):

advise/make recommendations/highlight best practices to the EURO executive on issues women in OR face: such guidelines can be disseminated to EURO member societies and Working Groups where positive progress/outcomes/activities of member societies may serve as a template for other member societies;

promote championing, networking and mentoring, especially of women at the early stages of their career in OR; and

stimulate a conversation around how OR can be utilised to help create a diverse and inclusive future.

WISDOM implements these actions through research, events and public relations activities. Action 2 is implemented mainly through online webinars and a visibility initiative called YoungWomen4OR. The work presented in this paper is a research activity aimed at addressing actions 1 and 3.

WISDOM produced a White Paper to highlight some of the issues that women working in OR and Analytics may face, and to recommend best practices within the discipline. Gender balance does not necessarily mean parity on teams or in decision-making bodies and committees. The number of women in OR may be low, and participation in committees can prove over burdensome and a hindrance to career progression; the so called “tonne of feathers” (EURO, Citation2019). Ensuring a proportional representation could be a useful starting point for the OR community by gathering data to model the OR network of actors (Carroll et al., Citation2020).

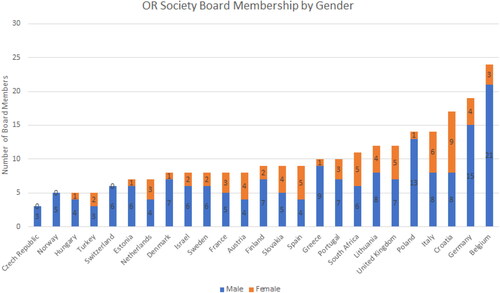

shows a snapshot of the current board representation by gender of EURO national OR Societies as reported on their websites. Of 25 national OR Societies three have only males (ie, Czech Republic, Norway and Switzerland), one has a 50/50 split (ie, Austria), and two have more female than male board members (ie, Croatia and Spain). The rest have a mix of genders and show a gender imbalance with more male than female board members. A simple average across the societies shows 73% of board members are male while 27% are female.

Another gender perspective on the OR community is the percentage of societies’ prizewinners over time. The EURO Gold Medal (EGM) was launched in 1985. 92% of the EGM recipients have been men. Martine Labbé was the first woman to receive the EGM in 2019, followed by Ailsa Land (posthumously) in 2021. The EURO Doctoral Dissertation Award (EDDA) was launched in 2004 and has been awarded to five women, and eight men (38% versus 62%). The EURO Distinguished Service Award (ESDA) was launched in 2009. 91% of the ESDA recipients are male. Ulrike Leopold-Wildburger was the first woman to receive the ESDA in 2021. There have been significantly more male recipients than female recipients across the award categories. It is perhaps no surprise to see more women in the EDDA award category compared to the others. It could be indicative of the “leaky pipeline” which starts after the PhD. It is heartening to see female recipients of the EGM and ESDA in recent years.

A similar finding is apparent looking at the gender of prizewinners from both The UK OR Society and INFORMS award categories:

the UK OR Society: the Doctoral Dissertation award was established in 2008 and had its first female recipient in 2017 (Jeeu Fong Sze); the Beale Medal was established in 1992, the first woman recognised was Ailsa Land in 2019;

INFORMS: the George B. Dantzig Dissertation award was established in 1994, its first female recipient was Daniela Pucci de Farias in 2002; the President’s Award was established in 1993, its first woman to be recognised was Margaret Brandeau in 2008.

Furthermore, an analysis of the top 100 cited OR academics on Google Scholar finds only one woman: Prof. Maria Grazia Speranza who holds the 72nd highest h-index in the OR Area of interest.

The imbalance in gender in OR society boards and in awards and visibility points to a gap in our understanding of the participation of women in OR. We do not have a clear understanding of how many women are active in OR, nor the barriers they encounter to full participation. The WISDOM White Paper notes that recruitment into STEM is not generally a significant barrier to broadening participation, but retention and promotion are. What appear to be women’s individual “choices” are shaped by social context factors. Gendered differences may be perceived as individual characteristics rather than societal practices of social differentiation. We do not yet understand if gender equality issues in other disciplines are as apparent, amplified or reduced in OR.

1.4. Research questions and contributions

There is a gap in our knowledge and understanding of gender issues facing the OR community. Our study provides insights for the OR community to better understand gender issues from a historic and current perspective. We focus on two aspects of the gender/OR nexus: articulating a gendered perspective of the history of OR, and identifying potential career challenges by gender to full participation in OR.

We aim to answer the following research questions:

Is there a gender dimension to the history of OR?

Are there gender differences in OR careers?

We conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) on the history of OR which we analyse through a gender lens to answer the first question. We carried out a survey on careers in OR during the EURO 2021 conference to answer the second question. The survey respondents were mainly academics. Our paper contribution is three-fold. Firstly, we enrich the history of OR literature through a novel exploration of the OR/gender nexus. To the best of our knowledge this has not been done before. Secondly, we gather primary data on careers in OR within the EURO community. Other disciplines have mapped career progress or networks by gender. To the best of our knowledge, only one paper investigates OR collaboration networks (Bravo-Hermsdorff et al., Citation2019). As such, our work is the first to explore the EURO OR community by gender. Thirdly, we critically analyse the survey data using statistical tools to understand gender factors in OR careers which, again, to our understanding, has not been attempted before.

The structure of the paper is as follows: Section 2 describes our methodologies in detail, Section 3 provides an analysis of our results, while discussion and conclusions are provided in Sections 4.

2. Materials and methods

We use a mixture of methods to answer our two research questions. We apply a gender lens to secondary data from an SLR to uncover gender perspectives on the history of OR. We gather primary data for statistical analysis via an online survey instrument to explore gender differences in OR careers.

2.1. Systematic literature review (SLR)

We search for articles in the Scopus database at the gender/OR nexus to answer Research Question 1. Search strings such as TITLE-ABS ((“operations research” OR “operational research”) AND (“gender” OR “sex” OR “male” OR “female”) AND INDEXTERMS (“history of OR”)) find zero hits.

Search Strings such as TITLE-ABS((”gender” OR” sex” OR” male” OR” female”) AND” history”) identify just under a quarter of a million papers. However we only find three in OR journals: two in Management Science, and one in Operations Research Forum. Broader search strings such as ((“operations research” OR “operational research”) AND (“gender” OR “sex” OR “male” OR “female”)) in the title or abstract yield 215 papers. However, the majority are biological or medical applications in the medical or animal welfare literature not relevant to our research questions. We refine this search by restricting the hits to those that are in OR journals: Annals of Operations Research, Journal of Combinatorial Optimization, Journal of The Operational Research Society, Interfaces, European Journal of Operational Research, Production and Operations Management, Operations Research Forum, and Journal of Simulation. This is Search 1, which in total yields 18 papers at the gender/OR nexus for analysis.

The lack of literature at the gender/OR nexus makes a review using standard approaches difficult. Therefore we supplement this set of papers with an additional search focusing on the history of OR. Search 2, in the Scopus database is: TITLE-ABS ((“operations research”” OR “operational research”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (EXACTKEYWORD, “History of OR”)). This search returns 38 hits at the gender/OR history intersection for review.

We synthesise both sets of papers into a taxonomy and analyse the papers by applying a gender lens to the paper contents.

2.2. Survey instrument

We implemented an online survey during the EURO 2021 hybrid conference to understand the issues facing women in OR, particularly in academic careers. We use a survey instrument to address Research Question 2: the gender dimension of OR careers, and use exploratory data and statistical analysis to assess the results.

We first secured research ethics approval (UCD HREC Ref: HS-E-21-56-Carroll), then designed and piloted the survey using Qualtrics. We disseminated the final survey via an anonymous link/QR code during the EURO 2021 hybrid conference 11–14 July 2021. The link was made available on the conference website during the conference and remained available up to the end of September 2021 for national OR societies to disseminate to their members.

Our survey aims to identify potential challenges by gender to participation in OR, and to create insights into career paths in OR. The survey consists of seven blocks: participant information (block 1), about you (block 2), career progression (block 3), participation in OR (block 4), gender dimension to OR (block 5), WISDOM support schemes (block 6), and OR career choice (block 7). Blocks 2-4 are the subject of this paper.

Block 2 explores characteristics such as gender, age, affiliated institution and location, caring responsibilities, career break(s), OR (sub-)discipline expertise, and employment circumstances. Block 3 attempts to map participants’ career progression focusing on time since the PhD award, institutional change after PhD and subsequent career stages and, in particular, motivations underpinning either a” change” or a” no change” of the institution. Block 4 enquiries about authors’ publication ordering conventions, invites open text comments on challenges to shape a career in OR, and role models. The remaining blocks cover gender dimensions of OR research and practice, and the reason(s) to choose a career in OR. The interested reader can find the complete list of survey questions, including all blocks, in Appendix A.

We collected 321 complete responses which we analysed using exploratory data analysis (EDA), tests for associations between categorical variables, regression and decision tree models. Three respondents preferred not to say or to self describe their gender. Since this number is small, we excluded their responses from further analysis to preserve those respondents’ anonymity. This leaves 318 responses for analysis.

3. Results

In this section we present the results of the SLR and analysis of the survey responses.

3.1. SLR results

Search1 identifies 18 OR articles in the gender/OR nexus, ie, OR articles that explicitly mention “gender” OR “sex” OR “male” OR “female”. Search 2 identifies 38 papers on the history of OR which we explore to uncover any latent gender dimensions.

3.1.1. Gender/OR nexus

Focusing first on the 18 papers identified in Search 1 at the gender/OR nexus, Bjarnadottir and Stone (Citation2022) summarise papers considered for the 2021 Daniel H. Wagner prize including Keskin et al. (Citation2021)’s work on sex-trafficking network interdiction which is already captured in Search 1 of the SLR. Therefore we omit (Bjarnadottir & Stone, Citation2022) leaving just 17 papers for detailed analysis. We group the 17 papers according to the role of gender in the paper. Gender occurs in six papers as an explanatory variable, in three papers as a component of an optimisation model, and in two papers as stakeholder involvement. shows a summary of the results.

3.1.1.1. Explanatory variable

Gender as an explanatory variable appears in Hirschfield et al. (Citation1995) and Rivett and Roberts (Citation1995) where patients’ sex is considered in community-based health services. Stevenson et al. (Citation2010) provide an application of discrete event simulation testing for a medical condition (thrombophilia) where gender is a feature of a patient’s profile. De Witte et al. (Citation2010) research pupil and school performance in girls only British single-sex schools. Otamendi et al. (Citation2012) offer a simulation approach to design drop-off/pick-up zones, where gender is contextually embedded in an application for the female University of Riyadh (Saudi Arabia). Baldiga (Citation2014) evaluate gender differences (male vs. female) when answering a test like the SAT (commonly used for college admissions in the US). The author finds that women tend to skip more answers if penalties to incorrect answers are present, gender is a predictor for a number of skipped answers, and there is a negative relationship between skipping questions and final test performance. Keskin et al. (Citation2021) propose an OR-based framework including grouping and prediction algorithms to combat sex trafficking in the USA. Also on human trafficking, Eryarsoy et al. (Citation2023) introduce a two-stage approach involving logistic regression first and then Bayesian belief networks to try and unveil complex patterns. More recently, gender is considered as an explanatory variable in a COVID patient risk assessment tool in Dede et al. (Citation2023), but is not found to play a significant role. Eskandarian et al. (Citation2023) also consider COVID, and through statistical analysis of medical data in an Iranian hospital come to the same conclusion that there is no significant association between gender and risk of mortality from a COVID infection. An interesting application by Sherman et al. (Citation2023) focuses on analysis of salary history bans in the US as a GPG reduction policy. Knowledge of job applicants’ previous salary could reinforce bias and perpetuate GPGs. However, in an analysis of a sample of 240 job changers in an educational institution in the UK, and a study of truncated time-series data from a UK recruitment firm which had voluntarily adopted a salary history ban, the authors find that the ban reduces pay for all applicants rather than reducing the GPG. They recommend that a combination of legislative interventions and awareness building could be more effective in reducing GPGs.

3.1.1.2. Optimisation model component

Gender as a component of an optimisation model appears in Sutcliffe et al. (Citation1984) who apply goal programming to the allocation of students to secondary schools in Reading (UK): one of the six goals is sex balance. Alpern and Katrantzi (Citation2009) use a game theory capproach to consider variants of stable marriage problems. Marriage is intended in the broader graphical sense like matching, where unequally sized gender labelled groups are to be matched according to preferences rather than by a centralised single decision maker. Durán and Wolf-Yadlin (Citation2011) propose several MILP models to select applicants to a master’s programme with an “affirmative action” criterion. Gender is explicitly addressed, one of the model sets is” all the female applicants” (p.280), and a lower-bound constraint on how many females should be enrolled is included in the model. Lastly in this group, Tang and Yuan (Citation2023) highlight the importance of choosing a fairness metric to ensure decision recommendation systems are aware of the needs of the subject groups and alert to the risk of bias or discrimination. They propose an interesting framework to ensure fairness and provide a theoretical perspective of a global utility function that can be maximised subject to meeting a target for the utility function of each subgroup. They mention gender as a possible group characteristic but do not provide any case study or application related to ensuring gender fairness.

3.1.1.3. Stakeholder involvement

Gender as stakeholder involvement can be found in Mwiti and Goulding (Citation2018) who take a holistic view to how Community Based OR can be used as a problem framing tool to include the needs and perspectives of disadvantaged groups with less agency. They describe a case study in Africa to support women’s community groups to develop business ideas and small enterprises. More recently, Amorosi et al. (Citation2021) interview female university professors at different academic and life stages with the goal of providing insight into the perception of gender gaps in the OR community. Emerging themes include discrimination, the necessity to step out of traditional societal “feminine” paths to embark in STEM studies, the so-called “leaky pipeline” (ie, fewer women progressing to top academic positions) and on a positive note, OR-based gender equality forums providing a positive environment such as WORMS, WORAN and WISDOM.

Table 1. OR/Gender nexus SLR results.

3.1.2. Gender/history of OR

Given the small number of papers at the gender/OR nexus, we next conduct a thematic analysis of the 38 History of OR papers identified by search two. We identify three main themes: (1) the OR community (people and places); (2) the epistemological (the OR theoretical knowledge base), and (3) phronesis and techne (the art and practice of OR). Where papers span multiple themes we label the paper by its most prominent theme. Once classified under our taxonomy we then apply a gender lens to uncover where and in what context gender implicitly appears, is mentioned or discussed. shows a taxonomy of the papers.

Table 2. History of OR SLR results.

3.1.2.1. OR community

22 papers address aspects of the OR community. Seven papers highlight members of the OR community. Biographies are of prominent males and commemorate Cecil Gordon (Rosenhead, Citation1989), Andrew McNaughton (Finan & Hurley, Citation1997), Patrick Blackett (Kirby, Citation1999), Saul I. Gass (Assad, Citation2006), Keith Douglas Tocher (Hollocks, Citation2008), Alan Turing (Haeusler, Citation2012), and Alex Green (Green et al., Citation2015).

The “founding fathers” of OR are remembered in Rosenhead (Citation2009) including Robert Watson-Watt (the inventor of radar) and Patrick Blackett. Among the founders of branches of OR we find just one female remembered: Ailsa Land (UK) who was associated with the development of IP branch and bound techniques, and we note, was the first female to receive the UK ORS Beale Medal in 2019 as well as a posthumous recipient of the EURO 2021 Gold Medal.

We identified two review papers. A bibliometric analysis of the most productive and influential authors in Merigó and Yang (Citation2017) shows they are predominantly males, while the review of the successes and challenges of OR in Thomas (Citation1994) notes the contributions of prominent males associated with founding the discipline but does not note the contributions of any females nor the gender imbalance in the OR community.

13 papers focus on regional development of OR and cover the UK/USA (Fildes & Ranyard, Citation1997), the UK (Keys (Citation1998), Kirby and Capey (Citation1998), Tomlinson (Citation1998), Turner (Citation2008), Rosenhead (Citation2009), Rand (Citation2024), the USA (Machol, Citation1998), Canada (Lindsey, Citation1998), the Arab world (Yousef, Citation2011), Africa (Ittmann, Citation2021), (Jablonský et al., Citation2022), and Slovenia (Povh et al., Citation2023). These papers tend to focus on the regional development of the OR profession, the type of OR taught or conducted in the region such as the increase in Government OR as a response to increased demand for analysis to support evidence-based policy (Turner, Citation2008). Some of these 13 papers discuss the diversity of applications in OR, and the geographic/regional diversity of authors at their conferences, but neither the gender of authors nor of members are discussed. There is no explicit gender dimension other than that where people are mentioned they are overwhelmingly male. Fildes and Ranyard (Citation1997) mention the intent of the “founding fathers” of OR and while Kirby and Capey (Citation1998) mention Charles Babbage (male) in the context of the development of “scientific management”, his collaborator Ada Lovelace (female) is not mentioned.

3.1.2.2. Epistemological – The theory of OR

Seven papers focus on the theoretical knowledge base of OR including major subtopics such as Analytics (Mortenson et al., Citation2015), Discrete Event Simulation (Hollocks, Citation2006), Probabilistic Decision Analysis (Morton & Phillips, Citation2009), Soft OR (Paucar-Caceres, Citation2010, Citation2011), Systems Dynamics (Coyle, Citation1997), and Strategic OR (Bell, Citation1998). Again, there is no explicit gender dimension except to note that the key people associated with the sub-topics are male.

3.1.2.3. Phronesis and Techne – The art and craft of OR

Finally, nine papers focus on the craft and practice of OR including problem structuring (Klein, Citation2009), applications to Iron, Steel and Coal industries (Kirby, Citation2000), Locational Analysis (Smith et al., Citation2009), Military (Kirby & Capey, Citation1997a, Citation1997b; Kirby & Godwin, Citation2010; Sawyer et al., Citation1989), and Town Planning (Yewlett, Citation2001a, Citation2001b). Again, there is no explicit gender dimension, except to note that the key people mentioned are male such as Charles Goodeve in Kirby (Citation2000). The review of military OR during WW2 OR is a summary of talks by four male OR practitioners (Sawyer et al., Citation1989).

Next, we apply a gender lens to this set of papers. It is not possible to tell the gender of the authors of the 38 papers as the journal author naming conventions often just give initials of first names. Knowledge of who is writing may give some insight to their perspectives and world view to explain why and what they are writing about their chosen topics.

It is not surprising given the military origins of OR to find that the OR history literature is male dominated. Papers on people and places are male dominated. A striking characteristic of the papers is the recognition and honouring of individual males for their contribution to the OR discipline. The literature is largely silent on the contributions of individual women or the role women may have played in founding and developing the OR discipline. As noted in Section 1.3, women have not been recipients of major OR awards until recently.

The epistemological knowledge base papers exhibit no explicit gender dimension. There is no attempt to check for systematic biases of mathematical models or in OR tool development. Similarly, the art and craft of OR papers show no evidence of gender awareness.

We note some use of dated stereotypes and language. Lindsey (Citation1998) notes the changing use of language in using gender neutral terms such as “person-months” in project resources rather than “man-months”. Terms such as “founding fathers” appear in Fildes and Ranyard (Citation1997) and Rosenhead (Citation2009), and the assumed male/female roles in Sawyer et al. (Citation1989) and the assumption that the manager is male in Thomas (Citation1994) come from an earlier era.

As noted in Rosenhead (Citation2009) developments in OR are interconnected with developments in society at large. The biography of Cecil Gordon notes his awareness of the social dimensions of science such as aspects of racial and feminist theories in the early twentieth century. Industrial demands in the 1930s and 40’s associated with World War II created a need for a more scientific approach to optimising operations. This simultaneously created opportunities for women to work outside the home and fill jobs normally reserved for men – albeit at a lower pay. Social changes such as student radicalisation noted in Rosenhead (Citation2009), and civil rights progress in the 1960s and 70’s meant changing demands for OR and paralleled women achieving legislative equality in many parts of the world. The 1980s and 90’s witnessed the privatisation of industry and the collapse of the Soviet Union which affected the nature of work for women and men.

Tomlinson (Citation1998) reviews the history and practice of OR to derive a framework with six principles of effective OR: “partnership, catalysis, interpenetration, independence, catholicity, and balance.” The partnership principle could be adapted to include a gender balance of partners or stakeholders in the project design and capture womens’ perspectives and needs from the outset of the OR project. The catalysis principle sees OR acting as an agent of change within organisations. In this case, OR problem structuring and modelling approaches could be harnessed to incorporate gender perspectives and metrics, and so support organisations to design and implement gender equality action plans.

3.2. Survey

Our first research question reflects back on the History of OR through a gender lens. In this section we address our second research question which looks to the present and aims to understand if there are gender differences in OR careers.

3.2.1. Exploratory data analysis

We report the results of the EDA and tests for survey blocks 2, 3 and 4.

tests allow us to check for relationships between categorical variables. The null hypothesis is that the variables are independent. Low p-values indicate that the null hypothesis is false and there is evidence that the variables are dependent, ie, there is an association between the variables. Tests that result in a p-value

are strongly significant, tests resulting in

values

are weakly significant.

3.2.1.1. Block 2: About you

The 318 participants are split 46% male and 54% female (Q1). We highlight a possible imbalance with a higher proportion of female respondents than most likely reflects the EURO community population proportion, but note an encouraging level of male respondents.

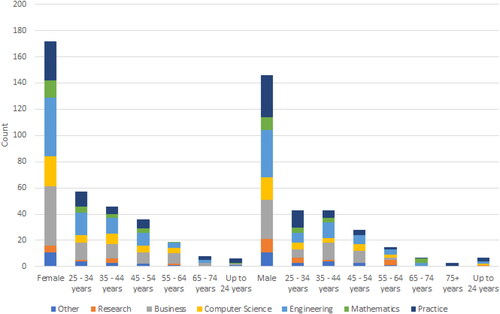

Q2 explores age which peaks at 25–34 years old (31%) followed by 35–44 years old (28%), and 45–54 years old (20%), see .

Figure 2. Survey Responses: Count by age, affiliation (academic faculty or practioner) and gender (172 female vs 146 male), frequency count on the y-axis.

90% of respondents are affiliated with institutions in Europe (Q3), with a good geographic spread of responses including France (24%), Germany (8%) Italy (7%), Portugal (7%), Austria (6%), Spain (5%), The Netherlands (4%) and the remainder coming from the rest of Europe.

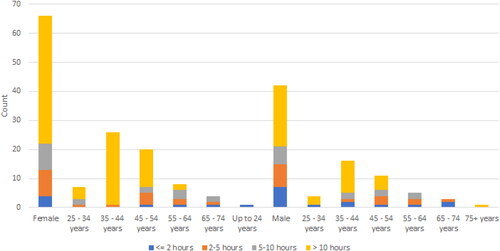

We asked about caring responsibilities (Q4). We define a carer according to the Central Statistics Office of Ireland as “someone who provides regular, unpaid personal help for a friend or family member”. 34% of respondents report having caring responsibilities. shows the counts of care hour by age and gender (Q4.2). A test for independence of having caring responsibilities and gender results in a p-value of .07 which is weakly significant. Testing the proportion of respondents with more than 10 h of weekly caring responsibility and gender results in a p-value of .08, which is weakly significant.

Figure 3. Count of caring hours by age and gender. 34% of all respondents reported care duties, 66 female vs 42 male respondents.

Our analysis shows a weak association between gender and caring responsibilities with women having more caring responsibilities than men, and spending more hours per week on those duties. The survey also asks whether the respondent is a joint, primary or secondary carer. Women report more primary carer and multiple caring roles than men. The p-value from a test for association between joint or primary caring roles and gender is .06, which is weakly significant.

We found a strong statistical significance associating care responsibilities and gender in the 35–44 year age bracket compared to other ages (p-value = .00). This is the age when many academics are building their profile as independent researcher.

We also asked about career break(s) (Q5). 38% of respondents reported taking a career break other than a research sabbatical. shows the percentage of career breaks by gender. The majority of leave is parental. A test for association of leave and gender yields a p-value of .00 indicating a strongly statistically significant relation between gender and career breaks. While some male respondents reported taking paternity leave, in most countries this is considerably shorter than maternity leave.

Table 3. Career break vs. gender.

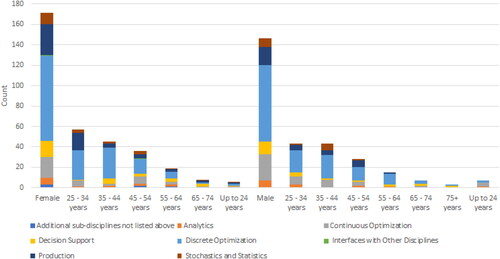

In relation to the OR area of interest, we asked respondents with which European Journal of Operational Research (EJOR) sub-disciplines categories the respondent (primarily) associates themselves (Q6) (Elsevier, Citation2018). displays participants’ affiliation to EJOR sub-disciplines. tests for association between gender and different OR areas finds no statistical differences. Therefore we can assume gender and the OR sub-disciplines are independent.

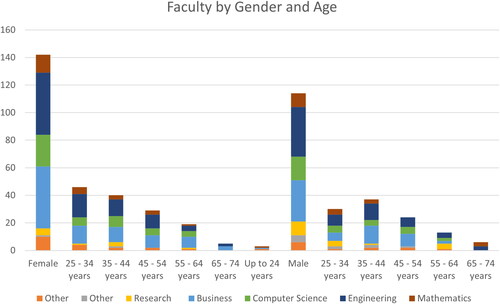

Respondents from academia constitute 80% of the sample (Q7). shows the split of respondents by faculty type, age and gender. The respondents come from Engineering (32%), Business (29%), Computer Science (16%), Mathematics (9%), with the remainder from other faculties or research departments. tests for the association between gender and faculty type finds no statistical differences. Therefore we can assume that gender and faculty type are independent.

3.2.1.2. Block 3: Career progression

The next block of questions relate to academic career progression. shows the average age of respondents by gender and academic role. We see a divergence in age by gender after Assistant Professor which may be indicative that it takes longer for women to progress to senior academic positions.

Table 4. Average age (years) by academic role and gender.

We asked how long respondents had been at their current workplace (Q8) and if they had changed institution (Q9.1). The majority had stayed at their current institution for more than 12 years (34.50%). Among the respondents holding a PhD (77.88%), nearly half (46.80%) had received their doctoral degree more than 12 years ago while 19.20% and 18.80% had been awarded their doctorate 3–7 years ago and 7–12 years ago, respectively (Q.9). It is interesting to note that nearly half (41.60%) of those holding a PhD had never changed institution since their PhD (Q9.1).

offers further insights by listing the number of changes by gender. suggests that females are more conservative or perhaps less mobile and have mostly never changed or only changed institution once since their PhD award.

Table 5. Number of changes of institution since PhD vs. gender.

and summarise the reasons reported by gender not to change (Q9.A1) and reasons for a change (Q9.B2), respectively. reports that the only motivation not to change where males slightly outnumber females is” I am satisfied with my current work/life balance”. Differently, all other reasons, see females outnumbering men. The widest gap reported is an inability to move because of caring responsibilities where males and females account for 0.7% and 6.5%, respectively. Other reasons not to change provided by respondents include, but are not limited to: country-dependent regulations, not being in a research-driven institution, feeling too old to find another position, unwilling to be distant from family, and awaiting promotion or the right opportunity to arise. details that, in line with Q9.1 by gender findings (ie, males being more prone than females to change institutions), males tend to outnumber females in all options except the open-text one. It is interesting that, when it comes to change, both males and females seem to have similar preferences: the main driver is the pursuit of a promotion, followed by a career change, and meeting family or caring responsibilities. Other reasons provided by respondents include, but are not limited to: increasing chance of securing tenure, looking for new research projects, networking, no contract renewal or extension available at a previous institution, and being closer to family.

Table 6. Reasons not to change institution vs. gender.

Table 7. Reasons to change institution vs. gender.

3.2.1.3. Block 4: Participation in OR

The final block of survey questions relates to participation in OR. For academics only, we enquired about the author name ordering convention generally used (Q10). shows the naming conventions by gender. There is no statistical difference between the conventions used by male and female, but more female academics report using the option “Lead author first, senior author last, other authors in between ordered by their contribution”.

Table 8. Author name ordering convention vs. gender.

To try and build a bigger picture of participation in the OR discipline, we also asked about the biggest challenges to pursuing a career in OR (Q11). Results are shown in by gender. Both male and female researchers report challenges to a career in OR, the challenge most reported by both genders is “Balancing work/life” which is followed by “Securing research funding” for males while “Getting papers published” for females, respectively. Moreover, “Balancing work/life” and “Getting promoted” are those challenges where the gap with the male counterpart seems to be the widest: for the former the gap is a half while for the latter is one and a half. Other challenges in free text responses include, but are not limited to: traveling abroad without the opportunity to bring children, balancing teaching and research loads, having impact and fun, finding a good position in a place where someone would like to live, being a female in a male-dominated environment, and couples not able to find academic positions in the same countries.

Table 9. Challenges to participation in OR vs. gender.

We also look at some of the drivers to support a career in OR starting with role models (Q12). 61% of our respondents reported having had a role model in their early career. Of these, 57% of females had a male role model, while 25% of males had a female role model. A test for association in same gender role models yields a strongly significant result with a p-value of .00. This is perhaps not surprising given there are likely more senior or established males in OR.

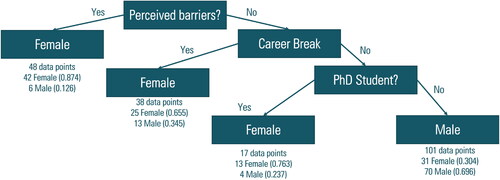

Lastly, we ask if there are particular barriers for the respondent’s gender to participate in OR (Q13). Only 17% perceived that there are barriers to their gender, split 15.1% female, 1.6% male. 78.5% did not feel there is any gender-specific barrier to participating in OR, split 34.7% female, 43.2% male.

3.2.2. Decision trees

Next we harness the findings of the EDA to build a regression model to predict gender (either male or female). This allows us to identify the features or explanatory variables most closely associated with gender. We built useful models using the following survey questions as features

About You (Block 2): Do you currently have any caring responsibilities (Q4)? How many hours per week on average do you spend on caring (Q4.2)? Have you ever taken a career break (Q5)? If in academia, what role are you currently in (Q7.A3)?

Career Progression (Block 3): Have you changed institution since your first post-PhD position (Q9.1)?

Participation in OR (Block 4): What author name ordering convention do you generally use (Q10)? Are there particular barriers for your gender to participate in OR (Q13)?

We split the dataset into 80% for training and 20% for testing and built several regression models using the MATLAB Classification Learner APP with 5-fold cross-validation. reports the accuracy in the validation and testing phases, respectively, for each classification model.

Table 10. MATLAB classification Learner APP results.

The most promising model is the optimisable tree with the highest accuracy in the testing phase (76.2%). We then tested a regression tree inline (ie, coding a script) in MATLAB with these two different settings: default (ie, “CategoricalPredictors”,” all”,” CrossVal”,” on”,” KFold”, 5,” SplitCriterion”,” gdi”,” MaxNumSplits”, 4) and custom settings (ie, “CategoricalPredictors”,” all“). The MATLAB syntax means that all predictors are treated as categorical, a 5 fold cross-validation is used, the Gini’s diversity index is used as a split criterion, and the maximum number of splits is set to 4. The custom settings tree provided an accuracy in the testing phase of 73.02% compared to the default settings one of around 55.56%.

displays the final decision tree which shows that perception of barriers to participate in OR, availing (or not) of a career break and the current academic position are indicators of gender.

4. Discussion and conclusions

In this paper we set out to answer whether there is a gender dimension to the history of OR, and if there are gender differences in OR careers.

4.1. The past

We cannot say that women have been written out of the history of OR. However, our SLR shows the male dominated origins of OR and that in the past women in OR have been largely invisible. The development of OR over time as a management and decision support tool in public and private industry have brought utility to many sectors, yet women and their contributions and role in sustaining the OR discipline have been largely overlooked. The record does not show the contribution of women in the early years of OR. We cannot say for sure whether this is because women had fewer opportunities to work, or participate in education due to societal expectations in the past, or whether their contributions were not recorded or recognised. It is likely that both lack of opportunity and lack of recognition contribute to the invisibility of women in the history of OR.

We have noted the military origins of OR. The societal contexts and environment which fostered the genesis of OR simultaneously created opportunities for women. The lack of a labour force while men were away fighting created a demand for female workers, and created new opportunities for women in industrial manufacturing. They were in general not paid at the same rate as equivalent male workers which contributed to GPGs and labour practices which continue to this day. The use of language and stereotypes may seem irrelevant to the theory and practice of OR. However they are instruments that encode societal norms (Carroll et al., Citation2020), which if left unchallenged may seep through OR problem structuring into mathematical models and algorithms.

We found little evidence that the theory and practice of OR historically has incorporated any gender dimensions - neither male nor female. Gender appears explicitly in a small number of OR papers as an explanatory variable, model component, or in stakeholder involvement. There is a significant research gap in the OR/Gender nexus. We have not yet begun to explore possible gender bias in our data and models in the same way the Machine Learning/AI communities have. This is an unexplored research direction and a major opportunity for future OR research.

4.2. The present

Turning to the present and our second research question, our survey presents a gendered overview of the EURO community and finds evidence that women in OR perceive barriers to career progression to a greater extent than their male colleagues.

We found weak statistical evidence that women in OR discharge more caring responsibilities than their male counterparts, particularly in the 35–44 year age bracket. This affects the remaining time that could potentially be devoted to other activities such as work. We found strong statistical evidence that taking a career break is associated with gender. This has implications for building and maintaining momentum in OR careers. We found no evidence of statistical difference of the proportion of women and men in different academic faculties, or active in different OR sub-disciplines. This suggests that men and women are equally active in all OR sub-disciplines.

There is an expectation of mobility in academic careers to promote and exchange scientific knowledge. We noted a lack of mobility by female respondents indicated by a lower proportion who change institute. Learnings from the forced online activities during the Covid pandemic could point to online collaboration opportunities for less mobile members of the OR community.

78.5% of respondents did not perceive any gender-specific barrier to participating in OR. This is good news for the OR community and is perhaps attributable to the multi- and inter-disciplinary nature of OR which has always required collaboration with diverse stakeholders. However, the most significant factor in determining gender in our decision trees is the perception of barriers to participation. This finding is consistent with surveys in other domains where women are more alert to barriers than their male counterparts (García-González et al., Citation2019; IRENA, Citation2019).

It is particularly important in male dominated disciplines where men have more decision making agency, see , that awareness of gender equality issues is created.

We note the limitations of our survey size and potential issues with the quality of data from online survey instruments. We also note that the majority of respondents are from academia leaving a gap in our understanding of career progression for practitioners. However, in the absence of other primary data, our analysis gives the first insights to gender issues in OR careers. The results in the decision tree in showing a branch of female PhD students could suggest that our early career women in OR are aware of, and concerned about gender equality issues. There is a challenge to attract women into careers in STEM, and a bigger challenge to keep them there - the so called leaky pipeline. However, our survey can only act as a guide, and further research is required.

4.3. The future

Finally, turning to the future, the OR community became more intellectually alert and agile once a dialogue on the basis for and purpose of analytic support was opened (Rosenhead, Citation2009). The OR community have also queried the possibilities for OR associated with the AI and analytics age (Burger et al., Citation2019; Mortenson et al., Citation2015; Ormerod, Citation2021) suggesting that this intersection may create new and more varied OR career paths. Such data science disciplines have already begun to explore gender dimensions associated with their tools and techniques. There is an emerging understanding of the importance of using unbiased data to train AI and ML models and to be alert that systematic biases that encode societal norms are not reinforced in their models. There is also a growing body of work on explainable AI to ensure results and recommendations are transparent. There are opportunities for the OR community to do the same and to reflect on latent gender dimensions in the theory and practice of OR.

Writing in 2009, Morton and Phillips (Citation2009) say: “the recent run of disastrous wars and economic crises shows that our ability, as a society, to make decisions under uncertainty is far from adequate. We believe that the intellectual frameworks and modelling ideas reviewed in this paper have great potential to bring greater clarity, transparency, and accountability to these decisions.” Such prescient comments emphasise the need for explainable models. Such (OR) models could contribute to advancing gender equality objectives.

Rosenhead (Citation2009) concludes that OR has been subject to redesign by larger forces at work in society. As society becomes alert to the hidden biases in systems and data OR must respond and reassess the potential for biases to be encoded in our mathematical models and simulations. Kirby (Citation1999) noted the importance of the role of governmental scientific advisors in shaping the development of OR. Similarly, current sustainability initiatives influence policies and societal direction. Thus national and institutional gender equality plans influence our lives in a concrete fashion – moulding how we live, where, and how we work. The OR discipline will be affected by national and institutional gender equality policies and, in turn, has a unique opportunity to leverage its history of supporting decision making and contribute to making gender equality a reality. OR frameworks such as that described in Tomlinson (Citation1998) could be adapted to include a gender lens and ensure that a gender perspective is included in the OR project design and specification at the outset.

Our paper highlights the historic lack of visibility of women in the OR and issues facing women in the OR today. Our survey findings reflect the experiences mainly of academics from the EURO community. We note the need for specific focused future research to capture the gender-related experience of the OR practitioner community, and the opportunity for future joint research on and between all groups that support the participation of women in the OR. We hope to stimulate a conversation and encourage a broad debate within the OR community on how OR can be utilised to help create a diverse and inclusive future.

Acknowledgement(s)

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their time and constructive feedback on earlier versions of this paper. The authors acknowledge the members of the EURO WISDOM Forum Research Subcommittee who helped conceptualise, design, and pilot the survey: Vesna Čančer (VC), Rosa Figueiredo (RF), Renata Mansini(RM), Nicola Morrill (NM), Frances O’Brien (FOB), Andreina Francisco Rodriguez (AFR), Tatiana Tchemisova (TT). Finally, we thank the people who took the time to respond to the survey and share their views.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Paula Carroll

Conceived and designed the project: Annunziata Esposito Amideo (AEA), AFR, FOB, Paula Carroll (PC), RF, RM, TT, VC. Collected the data (Ethics, Survey Design, Pilot): AEA, PC. Performed the analysis: AEA, PC. Wrote the paper: AEA, PC.

Annunziata Esposito Amideo

Conceived and designed the project: Annunziata Esposito Amideo (AEA), AFR, FOB, Paula Carroll (PC), RF, RM, TT, VC. Collected the data (Ethics, Survey Design, Pilot): AEA, PC. Performed the analysis: AEA, PC. Wrote the paper: AEA, PC.

References

- Alpern, S., & Katrantzi, I. (2009). Equilibria of two-sided matching games with common preferences. European Journal of Operational Research, 196(3), 1214–1222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2008.05.012

- Amorosi, L., Cavagnini, R., Sasso, V. D., Fischetti, M., Morandi, V., & Raffaele, A. (2021). Women just wanna have OR: Young researchers interview expert researchers. Operations Research Forum, 2(1) https://doi.org/10.1007/s43069-020-00039-8

- Assad, A. (2006). Four score years of Saul I. Gass: Portrait of an OR professional. Operations Research/Computer Science Interfaces Series, 36, 23–72.

- Baldiga, K. (2014). Gender differences in willingness to guess. Management Science, 60(2), 434–448. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2013.1776

- Bell, P. C. (1998). Strategic operational research. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 49(4), 381–391. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jors.2600467

- Bjarnadottir, M. V., & Stone, L. D. (2022). Introduction: 2021 Daniel H. Wagner Prize for excellence in the practice of advanced analytics and operations research. INFORMS Journal on Applied Analytics, 52(5), 395–397. https://doi.org/10.1287/inte.2022.1125

- Bravo-Hermsdorff, G., Felso, V., Ray, E., Gunderson, L. M., Helander, M. E., Maria, J., & Niv, Y. (2019). Gender and collaboration patterns in a temporal scientific authorship network. Applied Network Science, 4(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41109-019-0214-4

- Burger, K., White, L., & Yearworth, M. (2019). Developing a smart operational research with hybrid practice theories. European Journal of Operational Research, 277(3), 1137–1150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2019.03.027

- Carroll, P., Esposito Amideo, A., Francisco-Rodriguez, M. A., Mansini, R., Morrill, N., O’Brien, F., & Tchemisova, T. (2020). Promoting gender equality and inclusivity in euro activities: Wisdom forum white paper. White Paper

- Coyle, R. G. (1997). System dynamics at Bradford University: A silver jubilee review. System Dynamics Review, 13(4), 311–321. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1727(199724)13:4<311::AID-SDR134>3.0.CO;2-Y

- De Witte, K., Thanassoulis, E., Simpson, G., Battisti, G., & Charlesworth-May, A. (2010). Assessing pupil and school performance by non-parametric and parametric techniques. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 61(8), 1224–1237. https://doi.org/10.1057/jors.2009.50

- Dede, G., Filiopoulou, E., Paroni, D.-V., Michalakelis, C., & Kamalakis, T. (2023). Analysis and evaluation of major covid-19 features: A pairwise comparison approach. Operations Research Forum, 4(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43069-023-00201-y

- Durán, G., & Wolf-Yadlin, R. (2011). A mathematical programming approach to applicant selection for a degree program based on affirmative action. Interfaces, 41(3), 278–288. https://doi.org/10.1287/inte.1100.0542

- Elsevier. (2018). Author information pack. European Journal of Operational Research. sciencedirect.com/journal/european-journal-of-operational-research/about/aims-and-scope. Accessed 23rd April 2024.

- Eryarsoy, E., Topuz, K., & Demiroglu, C. (2023). Disentangling human trafficking types and the identification of pathways to forced labor and sex: An explainable analytics approach. Annals of Operations Research, 335(2), 761–795. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-023-05520-1

- Eskandarian, R., Alizadehsani, R., Behjati, M., Zahmatkesh, M., Sani, Z. A., Haddadi, A., Kakhi, K., Roshanzamir, M., Shoeibi, A., Hussain, S., Khozeimeh, F., Darbandy, M. T., Joloudari, J. H., Lashgari, R., Khosravi, A., Nahavandi, S., & Islam, S. M. S. (2023). Identification of clinical features associated with mortality in covid-19 patients. Operations Research Forum, 4(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43069-022-00191-3

- EURO. (2018). Women in science WIS event [Paper presentation]. The 29th European Conference on Operational Research. https://euro2018.euro-online.org/index.html3Fp=4516.html

- EURO. (2019). Women in OR – the equality, diversity and inclusion agenda: How do we weigh a tonne of feathers? [Paper presentation]. The 30th European Conference on Operational Research. https://www.euro-online.org/web/pages/1649/2019-dublin-euro-k

- EURO. (2023). OR and EURO: What is operational research? Retrieved from https://www.euro-online.org/web/pages/301/or-and-euro

- European Commission. (2020). A union of equality: Gender equality strategy 2020-2025 [Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions]. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0152 (Document 52020DC0152, 152)

- European Commission. (2021). She figures 2021: Gender in research and innovation: Statistics and indicators. Publications Office of the European Union.

- EUROSTAT. (2016). Glossary: Gender pay gap (gpg) (Tech. Rep.). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Glossary:Gender_pay_gap_(GPG)

- Fildes, R., & Ranyard, J. C. (1997). Success and survival of operational research groups-a review. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 48(4), 336–360. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jors.2600389

- Finan, J. S., & Hurley, W. J. (1997). Mcnaughton and Canadian operational research at Vimy. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 48(1), 10–14. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jors.2600326

- García-González, J., Forcén, P., & Jimenez-Sanchez, M. (2019). Men and women differ in their perception of gender bias in research institutions. PLOS One, 14(12), e0225763. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225763

- Gorman, M., & Klimberg, R. (2014). Benchmarking academic programs in business analytics. Interfaces, 44(3), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1287/inte.2014.0739

- Green, A., Green, D., & Francis, R. (2015). OR forum-a glimpse at an operation analyst’s World War II:” report on the combat performance of the remote control turrets of B-29 aircraft. Operations Research, 63(2), 262–268. https://doi.org/10.1287/opre.2015.1359

- Guyan, K., Oloyede, F. D. (2020). Equality, diversity and inclusion in research and innovation: UK review. UK Research and Innovation. https://www.ukri.org/files/final-edi-review-uk

- Haeusler, E. (2012). A celebration of Alan Turing’s achievements in the year of his centenary. International Transactions in Operational Research, 19(3), 487–491. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3995.2012.00848.x

- HEA (2016). HEA national review of gender equality in Irish higher education institutions June 2016 (Tech. Rep.). https://hea.ie/assets/uploads/2017/06/HEA-National-Review-of-Gender-Equality-in-Irish-Higher-Education-Institutions.pdf

- Hindle, G., Kunc, M., Mortensen, M., Oztekin, A., & Vidgen, R. (2020). Business analytics: Defining the field and identifying a research agenda (Vol. 281). Elsevier.

- Hirschfield, A., Brown, P., & Bundred, P. (1995). The spatial analysis of community health services on wirral using geographic information systems. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 46(2), 147–159. https://doi.org/10.2307/2583985

- Hollocks, B. (2006). Forty years of discrete-event simulation-a personal reflection. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 57(12), 1383–1399. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jors.2602128

- Hollocks, B. (2008). Intelligence, innovation and integrity – KD Tocher and the dawn of simulation. Journal of Simulation, 2(3), 128–137. https://doi.org/10.1057/jos.2008.15

- INFORMS (2023). Operations Research & analytics. https://www.informs.org/Explore/Operations-Research-Analytics

- IRENA (2019). Renewable energy: A gender perspective. https://www.irena.org/publications/2019/Jan/Renewable-Energy-A-Gender-Perspective

- Ittmann, H. (2021). The current state of OR in Africa. Operational Research, 21(3), 1793–1825. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12351-019-00516-x

- Jablonský, J., Černý, M., & Pekár, J. (2022). The last dozen of years of OR research in Czechia and Slovakia. Central European Journal of Operations Research, 30(2), 435–447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10100-022-00795-4

- Keskin, B. B., Bott, G. J., & Freeman, N. K. (2021). Cracking sex trafficking: Data analysis, pattern recognition, and path prediction. Production and Operations Management, 30(4), 1110–1135. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.13294

- Keys, P. (1998). OR groups and the professionalisation of OR. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 49(4), 347–354. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jors.2600551

- Kirby, M. W. (1999). The Blackett memorial lecture: 3rd December 1998. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 50(10), 985–993. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jors.2600811

- Kirby, M. W. (2000). Spreading the gospel of management science: Operational research in iron and steel, 1950–1970. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 51(9), 1020–1028.

- Kirby, M. W., & Capey, R. (1998). The origins and diffusion of operational research in the UK. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 49(4), 307–326. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jors.2600558

- Kirby, M., & Capey, R. (1997a). The air defence of Great Britain, 1920–1940: An operational research perspective. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 48(6), 555–568. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jors.2600421

- Kirby, M., & Capey, R. (1997b). The area bombing of Germany in World War II: An operational research perspective. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 48(7), 661–677. https://doi.org/10.2307/3010056

- Kirby, M., & Godwin, M. (2010). The invisible science: Operational research for the British armed forces after 1945. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 61(1), 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1057/jors.2009.156

- Klein, J. (2009). Ackoff’s fables revisited: Stories to inform operational research practice. Omega, 37(3), 615–623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2008.02.006

- Lindsey, G. (1998). Four good decades of OR in the Canadian department of national defence. Journal of Electrical Bioimpedance, 15(1), 26–32. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jors.2600495

- Machol, R. E. (1998). How OR can survive and prosper. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 49(4), 392–395. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jors.2600508

- Merigó, J., & Yang, J.-B. (2017). A bibliometric analysis of operations research and management science. Omega, 73, 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2016.12.004

- Mingers, J. (2000). The contribution of critical realism as an underpinning philosophy for OR/MS and systems. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 51(11), 1256–1270. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jors.2601033

- Mortenson, M., Doherty, N., & Robinson, S. (2015). Operational research from taylorism to terabytes: A research agenda for the analytics age. European Journal of Operational Research, 241(3), 583–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2014.08.029

- Morton, A., & Phillips, L. (2009). Fifty years of probabilistic decision analysis: A view from the UK. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 60(suppl 1), S33–S40. https://doi.org/10.1057/jors.2008.175

- Mwiti, F., & Goulding, C. (2018). Strategies for community improvement to tackle poverty and gender issues: An ethnography of community based organizations (‘chamas’) and women’s interventions in the Nairobi slums. European Journal of Operational Research, 268(3), 875–886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2017.12.009

- Ormerod, R. (1996). On the nature of OR-entering the fray. The Journal of the Operational Research Society, 47(1), 1–17. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2584247 https://doi.org/10.2307/2584247

- Ormerod, R. (2021). The fitness and survival of the OR profession in the age of artificial intelligence. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 72(1), 4–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/01605682.2019.1650619

- ORS. (2023). About OR: What is operational research? https://www.theorsociety.com/about-or/

- Otamendi, F., Laffond, J., & Segundo, N. (2012). Design of the drop-off-pick-up zones in buildings: The case of private transportation at the female university of Riyadh. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 63(1), 122–129. https://doi.org/10.1057/jors.2011.19

- Paucar-Caceres, A. (2010). Mapping the changes in management science: A review of ’soft’ OR/MS articles published in omega (1973–2008. Omega, 38(1–2), 46–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2009.04.001

- Paucar-Caceres, A. (2011). The development of management sciences/operational research discourses: Surveying the trends in the US and the UK. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 62(8), 1452–1470. https://doi.org/10.1057/jors.2010.109

- Petropoulos, F., Laporte, G., Aktas, E., Alumur, S. A., Archetti, C., Ayhan, H., Battarra, M., Bennell, J. A., Bourjolly, J. M., Boylan, J. E. & Breton, M. (2023). Operational research: Methods and applications. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 1–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/01605682.2023.2253852

- Povh, J., Zadnik Stirn, L., & Žerovnik, J. (2023). 60 years of OR in Slovenia: Development from a first conference to a vibrant community. Central European Journal of Operations Research, 31(3), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10100-023-00859-z

- Rand, G. K. (2024). From operational research quarterly to journal of the operational research society: The early editors. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 75(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/01605682.2023.2244339

- Rivett, P., & Roberts, P. (1995). Community health care in Rochdale family health services authority. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 46(9), 1079–1089. https://doi.org/10.2307/2584495

- Rosenhead, J. (1989). Operational research at the crossroads: Cecil Gordon and the development of post-war OR. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 40(1), 2–28. https://doi.org/10.1057/jors.1989.2

- Rosenhead, J. (2009). Reflections on fifty years of operational research. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 60(suppl 1), S5–S15. https://doi.org/10.1057/jors.2009.13

- Saravanan, B., Das, S., Sikri, S., & Kothari, D. P. (2013). A solution to the unit commitment problem—a review. Frontiers in Energy, 7(2), 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11708-013-0240-3

- Sawyer, F. L., Charlesby, A., Easterfield, T. E., & Treadwell, E. E. (1989). Reminiscences of operational research in World War II by some of its practitioners. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 40(2), 115–136. https://doi.org/10.1057/jors.1989.17

- Seth, S. (2009). Inequality, interactions, and human development. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 10(3), 375–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/19452820903048878

- Sherman, E. L., Brands, R., & Ku, G. (2023). Dropping anchor: A field experiment assessing a salary history ban with archival replication. Management Science, 69(5), 2919–2932. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2022.4658

- Smith, H., Laporte, G., & Harper, P. (2009). Locational analysis: Highlights of growth to maturity. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 60(suppl 1), S140–S148. SUPPL. https://doi.org/10.1057/jors.2008.172

- Stevenson, M., Simpson, E., Rawdin, A., & Papaioannou, D. (2010). A review of discrete event simulation in national coordinating centre for health technology assessment-funded work and a case study exploring the cost-effectiveness of testing for thrombophilia in patients presenting with an initial idiopathic venous thromboembolism. Journal of Simulation, 4(1), 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1057/jos.2009.12

- Sutcliffe, C., Board, J., & Cheshire, P. (1984). Goal programming and allocating children to secondary schools in reading. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 35(8), 719–730. https://doi.org/10.2307/2581978

- Tang, S., & Yuan, J. (2023). Beyond submodularity: A unified framework of randomized set selection with group fairness constraints. Journal of Combinatorial Optimization, 45(4), 102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10878-023-01035-4

- Thomas, L. C. (1994). Forty years on: Challenges and successes. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 45(12), 1343–1350. https://doi.org/10.1057/jors.1994.211

- Tomlinson, R. (1998). The six principles for effective OR-their relevance in the 90s. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 49(4), 403–407. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jors.2600509

- Turner, H. (2008). Government operational research service: Civil OR in UK central government. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 59(2), 148–162. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jors.2602452

- UNICEF (2017). Gender equality: Glossary of terms and concepts (Tech. Rep.). https://www.unicef.org/rosa/media/1761/file/Genderglossarytermsandconcepts.pdf

- WISDOM (2020). EURO WISDOM forum terms of reference (Tech. Rep.). https://www.euro-online.org/web/pages/1654/wisdom

- Yewlett, C. J. L. (2001a). OR in strategic land-use planning. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 52(1), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jors.2601086

- Yewlett, C. J. L. (2001b). Theory and practice in OR and town planning: A continuing creative synergy? Journal of the Operational Research Society, 52(12), 1304–1314. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jors.2601239

- Yousef, D. (2011). Operations research/management science in the Arab world: Historical development. International Transactions in Operational Research, 18(1), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3995.2010.00789.x

Appendix A.

WISDOM survey

Block 2” About You” includes questions Q0–Q7.2, block 3” Career progression” includes questions Q8–Q9.1.B2, block 4” Participation in OR” includes questions Q10–Q14, block 5” Gender dimension” is comprised of Q15, block 6” WISDOM support” includes Q16–Q16.1, and block 7” Career choice” is comprised of Q17.

Table A1. Survey questions.

Table A2. Survey questions (Cont’d).