ABSTRACT

There has been speculation about a growing demand for substances used without medical need for cognitive enhancement (CE). Thus, the prevalence rates and the identification of sociodemographic groups at risk of this behavior need further description and constant monitoring. We conducted a nationwide web-based representative sample (N = 22,101) (regarding sex, age, education, and federal state) of the general adult population in Germany. Results show a high past twelve months prevalence of consuming caffeinated drinks for CE (62.4% of respondents), followed by food supplements and home remedies (31.4%), and caffeine tablets (2.5%). The twelve-month prevalence of CE with prescription drugs was 3.7% (lifetime: 5.5%), of whom 29.1% reported using them 40 or more times; 40.5% of all respondents indicated some future intake willingness. Cannabis was the most frequently reported illegal drug for CE (past twelve months: 4.0%; lifetime: 10.7%), followed by the category amphetamine and methamphetamine (past twelve months: 1.0%; lifetime: 2.4%), and cocaine (past twelve months: 0.9; lifetime: 2.4%). We also show variation in the prevalence across multiple ascribed and achieved sociodemographic characteristics. These results can inform public policy and prevention strategies regarding the continued monitoring of the prevalence of CE and the identification of groups at risk of drug misuse.

Introduction

The use of different types of substances without medical indication with the intent to improve brain functioning has received widespread attention in scientific and public debates in recent years (d’Angelo, Savulich, and Sahakian Citation2017; Dresler et al. Citation2019; Greely et al. Citation2008; Sattler Citation2016). This practice has been termed cognitive enhancement (CE). The substances used for CE are classified differently depending on the legislation of a country. In Germany, where our study is located, substances used for CE can be classified as over-the-counter drugs that are freely available in, for example, supermarkets (e.g., Ginkgo biloba preparations and guarana); pharmacy-only drugs that are available without a prescription but that require the pharmacist to provide the buyer with a certain level of information (e.g., caffeine tablets); doctor-prescribed drugs whose medical necessity is ensured and that are only available in pharmacies wherein the pharmacist provides further information (e.g., methylphenidate and modafinil); and illegal drugs that are only available on the “black market” or in other countries with different laws (e.g., cocaine and microdoses of psychedelics) (Franke, Northoff, and Hildt Citation2015; Sattler Citation2016).

While there is no commonly agreed-on definition of CE, existing definitions typically refer to practices aiming to improve brain functioning (including better working memory, concentration, and cognitive control) without a medical need (e.g., Bostrom and Sandberg Citation2009; Cabrera Citation2017; Farah Citation2015; Hildt Citation2013; Sattler Citation2020; Smith and Farah Citation2011). The definition implies that individuals act on the basis of subjectively believing that certain substances will help them improve their cognitive performance. Thus, while improvement of cognition is intended, CE substances can potentially be ineffective or even have detrimental effects on performance (Ilieva, Boland, and Farah Citation2013; Repantis et al. Citation2010; Weyandt et al. Citation2018). Thus, similar to other potentially dangerous behaviors that are driven by a subjective belief but with problematic or absent evidence (such as taking colloidal silver or ivermectin to treat SARS-CoV-2 or using homeopathic remedies against many illnesses) (Adams, Baker, and Sobieraj Citation2020; Ernst Citation2002; Popp et al. Citation2021), the subjective belief in the performance enhancing effects of different substances may still lead to individuals using them and underestimating or ignoring related dangers (Caviola and Faber Citation2015; Huber, Sattler, and Mehlkop Citation2023).

While CE substances do not by definition need to have enhancing effects, such effects have been demonstrated for many common substances used for CE. For instance, caffeine has been shown to improve information processing and performance on tasks in individuals experiencing sleep loss (Irwin et al. Citation2020). The available data, however, do not cover most situations in which CE substances are self-administered. Furthermore, the effectiveness of prescription drugs in healthy individuals remains the subject of current research and seems to depend on the specific agent and cognitive ability examined. A recent review concluded that D-amphetamine does not have any effects, modafinil increased memory updating in non-sleep-deprived adults, and methylphenidate improved recall, sustained attention, and inhibitory control (Roberts et al. Citation2020). Moreover, several studies also observed effects of antidepressants that could be perceived as improving cognitive functioning (Gräff and Tsai Citation2013; Schmitt et al. Citation2006). Similarly, positive effects have been described for beta blockers (Campbell et al. Citation2008; Hahn et al. Citation2020; Hauser et al. Citation2018). Generally, the observed effects of CE substances appear smaller than subjective drug effects (Weyandt et al. Citation2018; Winkler and Hermann Citation2019). There is a widespread belief among lay people that such drugs improve brain functioning and help coping with strain (DeSantis, Webb, and Noar Citation2008; Vargo and Petróczi Citation2016; Zohny Citation2015). This belief might be, however, at least partially based on an overestimation of drug effects and an underestimation of side effects (Caviola et al. Citation2014; Roberts et al. Citation2020; Smith and Farah Citation2011). Thus, the “hype” around enhancement substances producing large boosts in performance seems not to be supported by research on their effects, which experts have warned about repetitively (de Jongh Citation2017; Neubauer and Wood Citation2022; Partridge et al. Citation2011). Thereby, it has been argued that the misrepresentation of effects in the media might have fueled this “hype” (Partridge et al. Citation2011; Schäfer Citation2018).

In addition to possible enhancing effects, the use of CE substances is often accompanied by health risks, including negative side effects and long-term health consequences, such as nausea, hypertension, sleep problems, and addiction, or other specific somatic adverse effects that are well known from other uses (e.g., increased bleeding risk with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants) (Lipman Citation2004; Nochaiwong et al. Citation2022; Ragan, Bard, and Singh Citation2013; Winder-Rhodes et al. Citation2010). While the described adverse side effects are more likely to occur as a result of prescription and illegal drug use, they are usually of less concern for legal enhancement. For example, consuming caffeine or other caffeine containing beverages at usual amounts does generally not threaten public health. However, individual tolerability depends on the degree of habituation and the dose. More extensive use, typically achieved by intake of caffeine tablets or energy drinks, could be also harmful. This is also indicated by a report released by the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment and the German Government on the dangers of caffeinated drinks (Bundesinstitut für Risikobewertung Citation2019; Die Bundesregierung Citation2019).

The health risks associated with CE substances – also in relation to their possible efficacy – play an important role in ethical debates around their consumption (Bavelier et al. Citation2019; Beddington et al. Citation2008; Forsberg et al. Citation2017; Jane and Vincent Citation2017; Racine, Sattler, and Boehlen Citation2021). These debates contrast the presumed advantages of CE substance use (e.g., increased competence, productivity, and collective welfare) with the possible negative effects (e.g., unfairness, social pressure to keep up by using drugs, diminished authenticity, increased inequality due to stratified access, and costs for the health care system). Both the majority of CE scholars as well as the public seem to be generally critical about this practice – especially with regard to consuming prescription and illegal drugs for CE (Bard et al. Citation2018; Dubljević, Sattler, and Racine Citation2014; Fitz et al. Citation2014; Hiltrop and Sattler Citation2022; Sattler et al. Citation2013; Schelle et al. Citation2014; Scheske and Schnall Citation2012). Still, also the use of legal drugs for CE could be seen as deviant as it can violate social norms that suggest not engaging in health-endangering behavior or behavior that may provoke the above-described adverse social effects.

Nevertheless, such attitudes can also change over time and could become more positive toward CE, particularly given the related trends in striving for self-optimization (Conrad Citation2007) and the demands associated with deep transformations in the working environment (e.g., digitalization, flexibilization, and the growth of the service sector) (e.g., Brühl and Sahakian Citation2016; Fink Citation2016; Siegrist Citation2016). These trends may contribute to the use of such drugs as well as processes of social diffusion (Baum, Sattler, and Reimann Citation2023; Huber, Sattler, and Mehlkop Citation2023; Schäfer Citation2018). In light of the potential health and social implications of CE, especially regarding the more dangerous forms of prescription and illegal drugs, it is important to further monitor the prevalence of CE substance use, variation in prevalence across different substance classes, polydrug use (i.e., the overlapping use of different substances and substance classes), and assess which population groups are more likely to use them (Bagusat et al. Citation2018; Franke et al. Citation2012; Heller et al. Citation2022; Ragan, Bard, and Singh Citation2013; Sattler Citation2016; Schelle et al. Citation2015).

Data from 2014 suggest that 2.2% of a nonrandom sample of individuals aged 12–49 years old in Germany (N = 5,511) used prescription stimulants nonmedically (i.e., medication not prescribed or consumed as intended by the prescriber, which may include enhancement and non-enhancement purposes) during the past twelve months (5.8% lifetime); the prevalence was 2.9% (9.6% lifetime) for prescription opioids and 2.8% (5.5% lifetime) for prescription sedatives (Novak et al. Citation2016). Moreover, a representative survey of the general population (age 18–59) found that 4.5% of the 8,200 respondents in 2015 showed problematic use pattern of psychoactive medication, indicating drug dependency (Rauschert et al. Citation2023b). This number slightly increased in 2021 to 5.2% of 7,050 respondents. This survey also reports an increase of the twelve-month consumption of any illegal drug in this period (2015: 7.5%, N = 8,251; 2021: 10.6%, N = 8,048), for example, of cannabis (2015: 7.0% N = 8,252; 2021: 10.0%, N = 8,049) and cocaine/crack (2015: 0.6%, N = 8,229; 2021: 1.6%, N = 8,065) (Rauschert et al. Citation2023a).Footnote1 For cannabis (2015: 1.2%, N = 8,224; 2021: 2.6% N = 8,018) and cocaine (2015: 0.2%, N = 8,231; 2021: 0.3%, N = 8,058), problematic use indicating drug dependency also increased, although for the latter not statistically significantly.

In recent years, studies – often with small and nonrandom samples – have also documented the use of such substances for CE purposes in specific populations, such as college students (DeSantis, Webb, and Noar Citation2008; McCabe et al. Citation2005; Teter et al. Citation2020), university students (Forlini et al. Citation2015; Heller et al. Citation2022; Sattler and Wiegel Citation2013; Schelle et al. Citation2015; Singh, Bard, and Jackson Citation2014), the workforce (Marschall et al. Citation2015; Sattler and Schunck Citation2016), and scientists (Wiegel et al. Citation2016). However, research using general population-based samples remains scarce (Bagusat et al. Citation2018; Sattler Citation2016). The prevalence estimates in these studies vary widely, warranting further studies on prevalence rates. For example, Maier, Ferris, and Winstock (Citation2018) found that the United States has the highest self-reported twelve-month prevalence of CE across respondents in a nonrandom sample from 15 Western countries. These authors observed a twelve-month prevalence of CE with prescription stimulants of 18.7% of 4,734 respondents in 2015 and 21.6% of 3,570 respondents in 2017 in individuals aged 16–65 years. The twelve-month prevalence of CE with illegal stimulants, such as speed and amphetamine, was 4.4% in 2015 and 14.7% in 2017. Such increases were found in almost all countries however, different participants were investigated in this repeated cross-sectional study, and the self-selection of the respondents recruited via media outlets may be an important factor contributing to this increase. The twelve-month prevalence in Germany, the country in which we conducted our study, did increase, but the levels started lower and the increases were less sharp: from 1.5% of 28,824 respondents in 2015 to 3.0% of 10,142 respondents in 2017 for prescription stimulants and from 1.7% in 2015 to 5.5% in 2017 for illegal stimulants. A representative survey of employees (N = 6,454; age 19–52) suggests a lifetime prevalence of CE prescription drug use of 3.0% (Sattler and Schunck Citation2016). A further representative survey of employees found a lifetime prevalence of 5.0% of prescription drug use to enhance cognition and mood among 3,017 employees (age 20–50) (DAK Citation2009) and an increase to 6.7% (3.3% only to enhance performance) in a follow-up study six years later using a new sample (N = 4,971) (Marschall et al. Citation2015). More recently, Bagusat et al. (Citation2018) reported a lifetime prevalence of prescription stimulants use of 4.3%, mood modulating prescription drugs of 20.3%, stimulating illicit drugs of 10.2%, cannabis of 23.4%, and “soft enhancers” (e.g., energy drinks, Ginkgo biloba, or caffeine tablets) of 85.3% in a smaller quota sample of 1,128 adults aged 18 years and older.

Given the increasing trends of CE use, it is unclear whether the estimates from older studies correspond to present prevalence rates. Furthermore, the comparability of existing studies is strongly limited because they largely differ in their definitions of CE as well as their classifications of CE substances (Sattler Citation2016; Schäfer Citation2020; Smith and Farah Citation2011). Moreover, several adult samples focused on employees in specific age ranges (Marschall et al. Citation2015) or specific occupations, such as scientists (Wiegel et al. Citation2016) or employed doctors, programmers, advertising specialists, and publicists (Schröder et al. Citation2015). Additionally, large representative samples are still rare, indicating the need for more research with such samples. It has been also criticized (Sattler Citation2016) that existing studies which exclude respondents who have prescriptions for certain drugs (Franke et al. Citation2012; Maier, Ferris, and Winstock Citation2018) may have biased estimations of prevalence rates, since respondents may feign symptoms to access such drugs; and even if they have a medical condition, they can still (mis-)use drugs with the intention to enhance cognitive performance (Fuermaier et al. Citation2021; van Veen et al. Citation2021). While many studies only used binary (lifetime) measures, describing how frequently drugs are used could help identify chronic users, who could be at risk of losing control over their drug consumption and developing an addiction (Müller and Schumann Citation2011). Moreover, experts also expect the trends in prevalence rates to continue due to a reported gap between observed willingness and prevalence rates (Dinh, Humphries, and Chatterjee Citation2020; Leon, Harms, and Gilmer Citation2019). As non-users with high willingness to use are presented with opportunities to engage in CE and to access CE substances, they may do so and, thus increase prevalence rates will continue to increase (Marschall et al. Citation2015; Sattler and Schunck Citation2016; Singh, Bard, and Jackson Citation2014).

In sum, we need more studies that regularly assess the use of substances with the explicit goal of enhancing cognitive performance without medical indication, in order to describe the respective prevalence in the general population using large random samples. Such large random samples are also important for examining whether certain sociodemographic groups are at particular risk of engaging in CE. Research investigating important ascriptive and achieved respondent characteristics, such as sex, age, education, income is currently inconclusive. For example, some reported higher prevalence rates or use willingness among males (Ponnet et al. Citation2015; Schröder et al. Citation2015; Singh, Bard, and Jackson Citation2014), others suggested higher use or willingness levels among females (Hoebel et al. Citation2011; Sattler and Schunck Citation2016), and others found no sex differences (Novak et al. Citation2007; Sattler and Schunck Citation2016; Weyandt et al. Citation2009; Wolff and Brand Citation2013). Another example is age, for which findings were also mixed. While some showed no or limited age effects, for example, for prior prescription drug use (Ponnet et al. Citation2015; Sattler and Schunck Citation2016; Wolff and Brand Citation2013), others reported a higher prevalence among younger age groups (Hoebel et al. Citation2011; Maier, Haug, and Schaub Citation2015; Schröder et al. Citation2015). Moreover, for many key characteristics, research is limited to a few studies examining the relation between CE and sociodemographic characteristics, such as employment status or level of education, income, having a partner, or place of residence, as well as having a history of a diagnosis of mental illness. Such characteristics could be assumed to be associated with CE drug use as they may indicate having the need for CE, for example students vs. retirees (Weyandt et al. Citation2009), having financial resources to obtain CE or alternative enhancements (Baum, Sattler, and Reimann Citation2023), being under the influence of social control, or receiving support from a partner (Carr and Springer Citation2010; Jang et al. Citation2018; Thoits Citation2011), having better access to drugs due to living in urban vs. rural setting (Galea, Rudenstine, and Vlahov Citation2005), or having experience with using or accessing relevant drugs via a prescription.

Current study

To overcome several limitations of previous studies, this study aims to assess the lifetime prevalence, the twelve-month prevalence, and the use frequency of legal substances, prescription drugs, and illicit drugs that are explicitly used with the aim of increasing cognitive performance without medical necessity. This study allows us to, furthermore, examine whether respondents engage in mainly one or multiple substance classes (i.e., polydrug use). Therefore, we will use a large representative population-based sample. We conducted an online survey, which has been shown to reduce socially desirable responding, in comparison to interviewer-based survey modes (Crutzen and Göritz Citation2010; Krumpal Citation2013). The sampling frame included people with and without prescriptions for CE and the questionnaire included questions regarding prior diagnosis, which will allow us to examine the variation in prevalence rates across these characteristics. We also assessed respondents’ willingness to use prescription drugs for CE, since willingness measures may help map the beginning of trends and demands for products that are not readily accessible or unavailable in legal markets. This approach is also important because the media hype around CE in recent years might have raised awareness of CE drugs; thus, the willingness to use CE drugs may have increased (DAK Citation2009; Partridge et al. Citation2011; Schäfer Citation2018; Wiegel et al. Citation2016). Moreover, we will explore the variation in CE across a wide range of sociodemographic characteristics that are ascribed or achieved, namely sex, age, education, employment status, income, having a partner, place of living, as well as currently or previously having a diagnosis of a mental illness and receiving treatment. Through the better identification of potential population groups with higher or lower risk of using CE, our study results can provide information to public health authorities and insurance companies regarding whether CE has reached problematic levels and if so, which groups should be potentially targeted by evidence-based prevention and intervention strategies in case of an elevated risk (Faraone et al. Citation2020).

Methods

Participants

The ENHANCE study is a nationwide web-based study of German-speaking residents in private households in Germany with internet access (i.e., approximately 95% of all households in Germany, Statista Citation2020). The sample was recruited via forsa.omninet, which provides a panel that is representative of the German population with regard to sex, age, education, and federal state. Participants were approached using a multistage random sampling process, which was based on the telephone master sample of the Association of German Market and Social Research Institutes (in German: Arbeitskreis Deutscher Markt- und Sozialforschungsinstitute e.V., ADM) (Citation2012; Häder and Gabler Citation1998). Within ADM, a group of market research agencies in Germany is responsible for the development of the sampling frame for member agencies. This frame is used to representatively select samples of the population living in private households (ADM Citation2012; Häder and Gabler Citation1998). Hence, every household has the same statistical chance to participate. Through this process, infrequent internet users are also captured, and self-selection into the panel and respondents with multiple accounts are prevented. The gross sample includes 47,406 adults; of these adults 27,149 (57.3%) consented to participate, and 24,809 (91.4%) completed the study. Of these completers, 22,024 came from the initial sample from 2019 and a further 2,785 came from an expansion sample from 2020, which served to counteract demographic imbalances due to selective participation. Participation was voluntary, and as the researchers, we never had access to the personal information of the respondents. Each participant received bonus points for participation, which could be converted to a voucher, a ticket for a charity lottery, or a UNICEF donation (2 Euros, which is worth approximately $2.30 USD). To allow for comparisons between all analyses, we conducted a listwise deletion of missing values, resulting in 22,101 cases. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Erfurt (reference number: EV-20190917). Although our study is not a medical study, we adhered to the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) to protect human research participants.

Instruments

Legal substance use

We asked the respondents about their twelve-month use of 1) caffeinated drinks (e.g., coffee, energy drinks, caffeinated soft drinks, mate, guarana, or black/green tea), 2) caffeine tablets, and 3) food supplements and home remedies (e.g., vitamins, Ginkgo biloba preparations, guarana, omega-3, valerian, and Saint John’s wort) with the aim of strengthening their cognitive performance (e.g., improve learning and thinking, memory, attention, alertness, and creativity). The question wording was: “The following pages deal with different things which people do or consume in order to keep up their mental performance (e.g., to learn and think better, to have a better memory, more attention, alertness and creativity). How about you? On average, how often did you do or consume the following in the last 12 months strengthen your mental performance? If it was exclusively for other reasons, please choose ‘never.’ Please answer all the questions, even if you have never done or consumed any of the following.” The responses for each of the three substances were assessed on a six-point scale as follows: “never or for other reasons” (0), “less than once per month” (1), “once per month” (2), “several times per month” (3), “once per week” (4), “several times per week” (5), and “daily” (6). Moreover, respondents could additionally choose the response option “no response” for this and all other survey measures. For the bivariate and multivariate analyses, each measure was dichotomized into “no use” (0) and “some use” (1).

Prescription drug use

The respondents answered questions about their use of prescription drugs with the aim of augmenting their cognitive performance (we explicitly mentioned that the respective use should not have been advised by a doctor for the treatment of a specific illness), indicating separately the frequency over the past twelve months and prior to the past twelve months (Sattler and Schunck Citation2016; Sattler and Wiegel Citation2013). We explained that such medications are usually taken, for example, for attention deficit, narcolepsy, dementia, depression, and anxiety and that they include stimulants (e.g., methylphenidate), anti-dementia drugs (e.g., piracetam), beta blockers (e.g., metoprolol), antidepressants (e.g., fluoxetine), among others. After these explanations, the question wording was: “How often have you taken such medication in the last 12 months and/or before that in order to support your mental performance without this being necessary due to illness?” The response options were “0 times” (0), “1–2 times” (1), “3–5 times” (2), “6–9 times” (3), “10–19 times” (4), “20–39 times” (5), and “40 or more times” (6), allowing for comparability with existing studies, such as (Johnston et al. Citation2019; Miech et al. Citation2015). Then, respondents who indicated some use (and those refusing to answer the initial question) were asked more specifically regarding the type of substance(s) they used over the past twelve months and before. The question wording was: “Now, please state whether you took any of the following prescription-only medication(s) in order to support your mental performance without this being due to an illness.” To support recall, respondents were shown different substance classes and common brand names (see Supplementary Information Table S1 for details). These substance classes included ADHD drugs and/or stimulants (see Limitations section regarding Guanfacine), anti-dementia drugs, beta blockers, and antidepressants. Respondents could also specify other medications used for cognitive performance enhancement and whether they had forgotten a medication’s active substance or name. All open responses were further coded into existing categories i.e., ADHD drugs and/or stimulants, anti-dementia drugs, antidepressants, beta blockers. Moreover, we also created new categories for analgesics (such as the opioid Tramadol or the pyrazolone Metamizol) and sedatives (such as the benzodiazepine Alprazolam or the antipsychotic Fluphenazine). Due to partially low case numbers in certain substance groups, we combined categories 1) to 4) into ADHD drugs and/or stimulants and categories 5) to 9) into anti-dementia drugs. For the bivariate and multivariate analyses, we created dichotomous measures indicating “no use” (0) and “some use” (1) over the past twelve months and over the lifetime.

We also assessed the willingness to use prescription drugs for cognitive performance enhancement because this construct can be considered as an important proximal antecedent of future enhancement behavior (Baum, Sattler, and Reimann Citation2023; Jain and Humienny Citation2020; Molloy et al. Citation2019; Sattler et al. Citation2014). The question wording was: “Could you imagine taking prescription medication for the following purposes without this being necessary due to illness?” To better understand the specific forms of CE desired by users (Roberts et al. Citation2020), nine items asked respondents about their willingness to take prescription drugs for different purposes without it being necessary due to an illness (i.e., “better concentration,” “staying awake longer,” “better memory retention,” “improved alertness,” “improved motivation,” “more creativity,” “better decision-making,” “better self-control,” and “combatting nervousness or uneasiness”). The response options were “absolutely not” (0), “probably not” (1), “about half/half” (2), “probably” (3), and “absolutely” (4) (Huber, Sattler, and Mehlkop Citation2023). To examine the dimensionality of the willingness objectives, we ran a principal component analysis. Results revealed a one-component solution (all components had loadings > 0.705, see Supplementary Information Table S2), and reliability was high (α=.94), indicating that the nine objectives can be reduced to one use willingness dimension. For the bivariate and multivariate analyses, respondents were considered as having at least some willingness (1) if they indicated response option two or higher on at least one use purpose and as having no willingness otherwise (0).

Illegal drug use

We assessed use of illegal drugs with the aim of enhancing the cognitive performance (as described above) over the past twelve months and prior to this period. The question wording was: “Next, we are dealing with substances which cannot be purchased legally. How often have you taken such substances in the last 12 months and/or before that, in order to support your mental performance (e.g. for better concentration, memory, alertness, creativity)? If you do not know the precise frequency, please estimate.” Response options were: “0 times or only for other reasons” (0), “1–2 times” (1), “3–5 times” (2), “6–9 times” (3), “10–19 times” (4), “20–39 times” (5), and “40 or more times” (6). We assessed the use of illegal drugs within four categories by asking about the use of 1) cannabis, 2) amphetamine and methamphetamine (e.g., speed, crystal meth, and medications not approved in Germany), 3) cocaine, and 4) other substances that cannot be purchased legally (e.g., ecstasy, LSD, magic mushrooms, crack, and ketamine). Due to low twelve-month and lifetime use prevalence, the last three categories were combined to indicate the use of other illegal drugs for each period. For the bivariate and multivariate analyses, we created dichotomous measures indicating “no use” (0) and “some use” (1), separately for each illegal substance category (cannabis and other illegal drugs) and the timeframe (use over the past twelve months and the lifetime).

Sociodemographic characteristics

Our analyses included the respondents’ sex, age, education, and whether they had a partner living in household. We also included employment status using the categories full-time employment, part-time employment, in education, and not employed (cf., Beckmann et al. Citation2016). Thereby, education is comprised of individuals receiving educational/occupational training or retraining as well as secondary education pupils and post-secondary education students. Not employed consists of unemployed and retired individuals as well as those on parental leave. Moreover, we examined the household equivalence income, for which we assessed the estimated monthly net household income with an open-ended question, and in the case of no answer, income categories were shown (cf., Beckmann et al. Citation2016). Regarding the income categories, the mean value of each category was used. For the last category “20.000 and more,” which was open-ended, the value 20.000 was used (Celeste and Luiz Bastos Citation2013). We computed the equivalence income by considering the number of household members with the OECD-modified scale (Hagenaars, De Vos, and Asghar Zaidi Citation1994); thus, the first adult had a weight of 1, each additional adult had a weight of 0.5, and each child (under 14 years) had a weight of 0.3. Then, income was divided by the weight. Afterwards, income was categorized into three categories based on the median distribution. Respondents with incomes lower than 60% of the medium income were categorized as low income, while respondents earning more than twice the medium income were categorized as high income. Respondents who were above the low income cutoff point and below the high income cutoff point were categorized as medium income. Place of residence was categorized as either rural or urban settlement structure (Federal Institute for Research on Building; Urban Affairs and Spatial Development Citation2017) using respondents’ postal codes. Finally, we included whether respondents have received a diagnosis of a mental illness (e.g., depression, attention deficit disorder (ADD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), phobias, dementia, or other mental illnesses) and if so, whether they are still in treatment or no longer in treatment (see ).

Table 1. Sample description without and with sampling weights (N = 22,101).

Weighting

Sampling weights were used in all analyses to increase the representativeness of the sample given that women, younger individuals, and individuals with less education were underrepresented in comparison to the general adult population (). The weights were computed using iterative proportional fitting (raking) (Kolenikov Citation2014) based on the distribution of sex, age, education, and federal state in the general adult resident population of Germany (with internet access).

Statistical analysis

First, we present the descriptive statistics for each prevalence measure (). Second, we examined polydrug use, i.e., the overlap among different substance use outcomes. To assess the association between drug and drug class uses, we computed percentages of the overlap of two substances at a time as well as Pearson´s correlations (). We refer to Sullivan and Feinn (Citation2012) as a guideline about the strength of an association (i.e., r >±.2 indicates a small effect, r>±.5 a medium effect, and r>±.8 a large effect). Third, we used logistic regression models (Long and Freese Citation2001) to test the differences in prevalence across sociodemographic characteristics (, and Tables S3a, S4a, S5a and S6a). For categorial variables with more than two groups, we provide further analyses in which we rotated the reference group to allow for a comparison of all groups (Tables S3b-S3d, S4b-S4d, S5b-S5c and S6b-S6c). To indicate the magnitude of the associations between the different prevalence measures and each sociodemographic group, we present unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) for bivariate relations and adjusted ORs when controlling for all other variables, along with their confidence intervals. Thereby, an OR ≥ 1.50 (≤.67) can be understood as a small effect, an OR ≥ 2 (≤.5) as a medium effect, and an OR ≥ 3 (≤.33) as a large effect (Sullivan and Feinn Citation2012). It should be noted that such guidelines for effect sizes are conventions, rather than statistical theory, and that their interpretation remains context specific (Ferguson Citation2009). All analyses were performed with the statistical software package Stata 16.

Table 2. Prevalence of different drugs used for cognitive enhancement and respective use periods across respondent characteristics in percentages with 95% confidence intervals in square brackets (N = 22,101).

Table 3. Overlap among different use outcomes for cognitive enhancement (N = 22,101).

Results

Descriptive findings

Legal substances

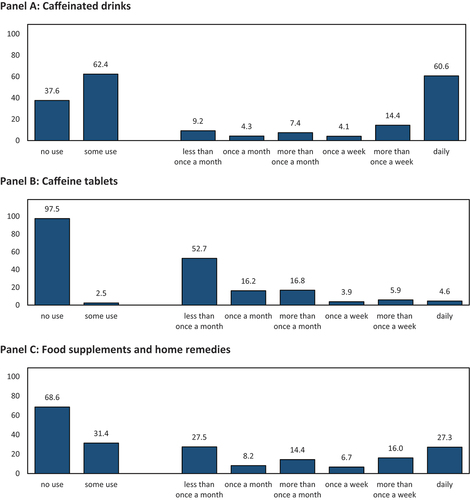

Panel A of shows that the twelve-month prevalence of consuming caffeinated drinks with the intent to enhance cognitive performance was 62.4%; one in ten respondents consumed such drinks less than once per month, while six in ten respondents consumed such beverages daily. Caffeine tablets were used by only 2.5% of respondents (see Panel B); the majority of which were relatively infrequent users. Food supplements and home remedies were used by approximately one-third of respondents for CE, with almost three in ten reporting daily usage (Panel C).

Prescription drugs

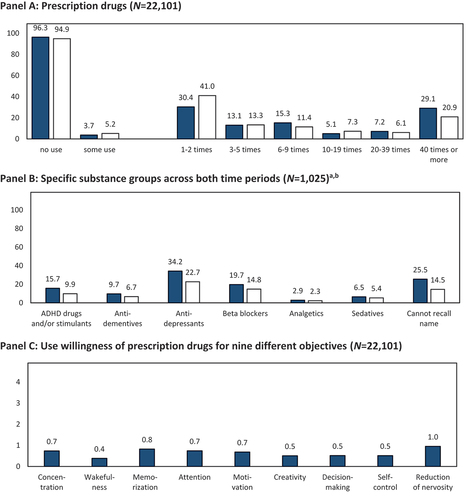

Panel A of shows that the twelve-month prevalence of prescription drug use with the intent of CE was 3.7%; every third respondent engaged in such use 1–2 times, while another third engaged in such use 40 or more times. Prior to the past twelve months, 5.2% of respondents used prescription drugs for CE; of these respondents, four in ten used prescription drugs 1–2 times, and two in ten used prescription drugs 40 or more times. Combining both periods resulted in a lifetime prevalence of 5.5% (the differing interval widths of the response options in both use periods do not allow an aggregation into lifetime use frequencies). Panel B shows that antidepressants were the most commonly used substance group over the past twelve months, followed by beta blockers, ADHD drugs and/or stimulants, sedatives, and analgesics. Several respondents were unable to recall the active substance or name of the medication they used. Two of five respondents indicated some willingness to take prescription drugs for CE; of whom, reducing nervousness and increasing concentration were the most prevalent purposes for which respondents were willing to take prescription drugs (Panel C). As sensitivity analyses, we repeated the analyses by using alternate definitions of willingness to take prescription drugs to enhance a certain cognitive function (see Methods section). When willingness was defined as only “probably” or “absolutely” (excluding individuals who may be willing to use in principle but do not show a stronger preference in favor of use, i.e., response category “about half/half”), 24.9% of the sample was considered as willing to take prescription drugs for CE. When willingness was defined as only “absolutely” (only considering the strongest possible willingness), 7.7% of the sample was considered willing.

Figure 2. Past twelve months (![]() ) and prior to the past twelve months (□) prevalence and respective frequencies of using prescription drugs for cognitive enhancement. notes: anot all respondents provided substance names; thus, the number of users reflected in the graph is lower than that in the general prevalence information. binformation of analgesics and sedatives was generated from open answers.

) and prior to the past twelve months (□) prevalence and respective frequencies of using prescription drugs for cognitive enhancement. notes: anot all respondents provided substance names; thus, the number of users reflected in the graph is lower than that in the general prevalence information. binformation of analgesics and sedatives was generated from open answers.

Illegal drugs

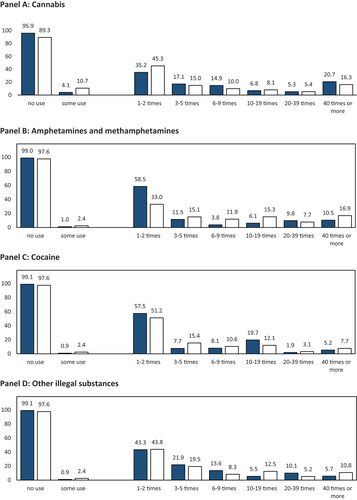

Panel A of shows that 4.1% of respondents reported the use of cannabis for CE over the past twelve months; of these, 35.2% reported very infrequent use, while 20.7% reported using cannabis 40 or more times. Furthermore, one in ten respondents reported using cannabis prior to the last twelve months; of these, almost every second respondent used cannabis 1–2 times, and 16.3% used cannabis 40 or more times. Combining both periods resulted in a lifetime prevalence of 10.7%. Panel B shows a much lower prevalence of the category amphetamine and methamphetamine used for CE over the past twelve months and prior. Of the respondents who reported such use, most used these substances 1–2 times, while every tenth (past twelve months) and sixth respondent (prior) reported using them very frequently. Cocaine and other illegal drugs were used by a similarly small share, and infrequent use was most commonly reported frequency (Panels C and D). The combined prevalence of amphetamine and methamphetamine, cocaine, and other illegal drugs was 1.6% over the past twelve months and 4.1% over the lifetime.

In total, 7.8% of respondents reported using either prescription or illegal drugs for enhancement purposes over the past twelve months (lifetime: 16.0%). When further including legal substances, such as caffeinated drinks, the total share of respondents who reported using CE substances over the past twelve months was 69.9%.

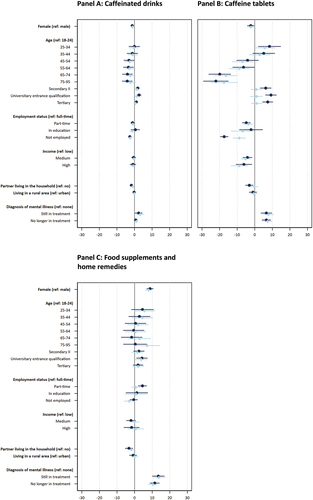

Variation across respondents

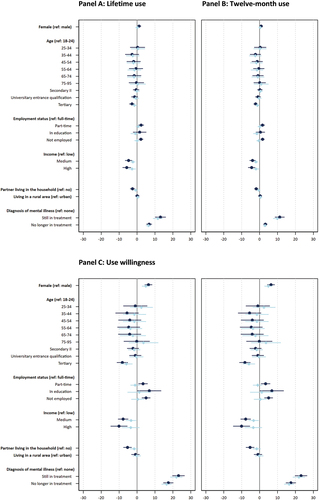

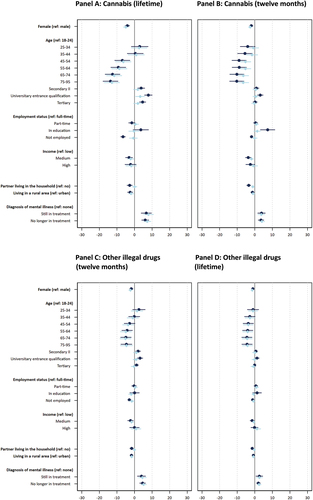

To examine sociodemographic variation in use prevalence, we report percentages indicating the share respondents who use each substance (), and unadjusted and adjusted ORs based on logistic regression models. The ORs for legal drug use are displayed in Panels A to C of and Tables S3a-S3d; for prescription drugs in Panels A to C of and Tables S4a-S4d; for cannabis in Panels A and B of and Tables S5a-S5c; and for other illegal drugs in Panels C and D of and Tables S6a - S6c. In the following presentation, we focus on adjusted ORs with at least small effect sizes (as defined in the Methods section).

Figure 4. Coefficient plots of twelve-month use of legal drugs for cognitive enhancement (N=22,101). Notes: ![]()

Figure 5. Coefficient plots of prescription drug use for cognitive enhancement (N=22,101). Notes: ![]()

Figure 6. Coefficient plots of illegal drug use for cognitive enhancement (N=22,101). Notes: ![]()

Sex

Our results show that for some substances there are no substantial sex differences in the probability of CE consumption (i.e., for caffeinated drinks; food supplements and home remedies; lifetime and twelve-month prescription drug use; and the intention to use prescription drugs), while for other substances, females were less likely to report using the substance as compared to males. For example, the adjusted OR of 0.609 indicates that females, as compared to males, have a 39.01% lower likelihood of reporting caffeine tablet consumption for CE – which shows a small effect of sex on caffeine tablet consumption. We also observed small sex differences in the lifetime use of cannabis and other illegal drugs, while the effects are of medium size for the respective use over the past twelve months, suggesting that males were more likely to report such use than females.

Age

We find substantial variation in prevalence across age groups as indicated by numerous small, medium, and large effects of age on use and willingness. One key pattern is that the respondents aged 18–44, as compared to those over 44 years old, were more likely to report use over the past twelve months of caffeinated drinks, caffeine tablets, cannabis (also lifetime) and other illegal drugs (also lifetime). For example, the age groups 18–24, 25–34, and 35–44 were at least 1.78 times more likely to report caffeine tablet use, as compared to the other four age groups. These effects were generally larger for use of cannabis and other illegal drugs over the past twelve months and lifetime. Furthermore, the age group 44–54 and partially the age group 55–64 had higher likelihoods of reporting CE-related use of cannabis and other illegal drugs, compared to most of the older age groups. However, the pattern is somewhat different for prescription drugs used for CE over the past twelve months and lifetime. Here, the age group 25–34 had a substantially higher likelihood reporting such use as compared to several older groups. Nevertheless, the age group 75–95 had a higher likelihood of reporting prescription drug use, compared to several younger age groups. Respondents in age groups 35–44 and 45–55 had lower likelihoods of reporting such use compared to most other age groups. Interestingly, no substantial variation across age is found regarding food supplements and home remedies as well as willingness to use prescription drugs for CE.

Education

Prevalence of CE substance use varied across education groups as indicated by several small effects of education on use. On the one hand, caffeine tablets were less likely to be used for CE by members of the lowest education group (Secondary I and below) as compared to the second lowest education group (Secondary II) and those with a university entrance qualification. On the other hand, respondents in the two lowest education groups were more likely to report use of prescription drugs and other illegal drugs for CE over the past twelve months, compared to the highest education group (tertiary). The likelihood of reporting use of other illegal drugs was also higher for the highest education group in comparison to those with a university entrance qualification. Other substantial differences between education groups did not occur.

Employment status

CE substance use patterns also varies according to employment status. For example, respondents working full-time reported a substantially higher likelihood of caffeine tablet use for CE over the past twelve months as compared to those in education (small effect) and those not employed (large effect). In this latter group, the use of caffeine tablets was almost nonexistent and, as indicated by the moderate effect sizes, they were substantially less likely to report such use compared to all other groups. The participants still in education were substantially less likely to report using prescription drugs for CE over the past twelve months, as compared to those employed full- or part-time (both effects are small in size). We also observe small to large effects of employment status on past twelve months and lifetime use of other illegal drugs for CE, whereby those in full- and part-time employment were more likely to report such use, as compared to those in education and not employed. Meanwhile, part-time, as compared to full-time, workers were more likely to report the use of other illegal drugs for CE over the past twelve months. The differences in such use over the past twelve months between part-time worker and those in education were particularly large. No substantial differences across employment status were found for caffeinated drinks, food supplements and home remedies, lifetime use of prescription drugs, as well as past twelve months and lifetime cannabis use.

Income

While no substantial differences were found in the likelihood to use legal substances across income levels, respondents with lower incomes had a higher likelihood of reporting use of prescription drugs for CE over the past twelve months and lifetime, as compared to those with medium or higher incomes. Respondents with lower incomes, as compared to medium incomes, also had a lower likelihood to report use of cannabis over the past twelve months. The medium-income group was more likely to report lifetime use of other illegal drugs than the lower and higher income groups. Interestingly, the higher-income group was more likely to report use of other illegal drugs over the past twelve months, as compared to respondents with lower or medium income. All reported income effects are small, with the exception of the last effect (higher vs. medium income), which is of medium size.

Partner

Respondents with a partner living in the same household had a lower likelihood of reporting the use of caffeine tablets for CE over the past twelve months, as compared to those not living with a partner (as indicated by a small effect). All other effects were not substantial.

Place of residence

Legal substance and prescription drug use did not differ substantially with regard to living in an urban or rural area. However, differences with small effect size suggest that respondents in rural areas had a lower likelihood of using other illegal drugs over the past twelve months and lifetime as compared to respondents in urban areas.

Diagnosis of mental illness

Respondents diagnosed with a mental illness, both who were undergoing treatment and those no longer in treatment, reported substantially higher likelihoods of using all investigated legal CE substances (with the exception of twelve-month prevalence of caffeinated drinks), prescription drugs, and all illegal drugs in comparison to those who were never diagnosed with a mental illness. Effect sizes ranged from small (e.g., twelve-month prevalence of food supplement and home remedy use) to large (e.g., twelve-month prevalence of prescription drug use). We also observe small to moderate effects on caffeine tablets and prescription drug use (twelve months and lifetime), indicating that respondents still in treatment were more likely to report using such substances in comparison to those no longer in treatment.

Sensitivity analysis

As a sensitivity analysis, we also investigated variation in willingness across respondents using a stricter definition of willingness (see above) and found similar patterns (Tables S7a and S7b). Given that drug use can be a sensitive topic for some respondents, we also examined anonymity perceptions regarding our study (Patrzek et al. Citation2015) and found that only a very small minority of 0.7% expected their responses not to remain confidential. We also reran our multivariate analysis to test the stability of our results when including these perceptions and found that (except for minor changes) the reported pattern remained stable and that such perceptions were partially associated with a lower prevalence of use (see Tables S8a, S8b, S9a, S9b, S10a, S10b, S11a, and S11b).

Evidence for polydrug use

To investigate the prevalence of overlapping use of different substances for CE, we provide percentages of overlapping use (upper part of ) and correlation coefficients between the measures (lower part of ). One interesting pattern is that for all substances examined, the prevalence rates of consuming caffeinated beverages were higher for users of other CE substances than the full sample (which was 62.2%). For example, over the past twelve months, the rates of caffeine beverage consumption were 94.6% for users of caffeine tablets, 81.9% for users of prescription drugs, and 85.8% for users of cannabis. Another finding demonstrating an overlap between users of different substances is that among the 4.1% of the respondents who reported cannabis use for CE over the past twelve months, 12.6% also reported using caffeinated tablets for CE (while only 2.5% of the full sample reported such use) and 16.0% reported a twelve-month use of prescription drugs for CE (compared to 3.6% of the full sample). Thus, the respondents who used cannabis for CE had substantially higher rates of using other substances for CE. Furthermore, among respondents who used prescription drugs for CE over the past twelve months, 25.7% also reported a lifetime CE-related use of cannabis, and 18.7% of other illegal drugs, which is substantially higher than in the full sample (10.7% and 4.1%, respectively).

When looking at the strength of the relationships in the lower part of , the effects are mostly below the threshold for small effects (i.e., r<±.2). Some exceptions are strong association between lifetime and twelve-month use of prescription drugs and of moderate strength between lifetime and twelve-month use of cannabis and other illegal drugs, respectively. Hence, these associations are within a specific substance category and are unsurprising given the definition of the lifetime variable (which also includes use over the past twelve months).

Within the class of illegal drugs, associations of small sizes exist between the use of cannabis and other illegal drugs – especially for lifetime use of both substance types. Within the class of legal drugs, the use of caffeinated drinks, food supplements and home remedies also had small associations with each other. Thus, although there are also overlaps between substance classes, these appear less strong.

Discussion

Based on solid empirical data from the largest representative population-based study on CE in Germany to date, this study aimed to provide reliable estimates of the previous twelve-month and lifetime prevalence of using different substances with the intention to increase cognitive performance and, thus, of a behavior possibly violating social and/or legal norms. This study also explored variation across a wide range of sociodemographic characteristics, such as sex, age, education, employment status, and income in order to better understand which sociodemographic groups have a higher or lower likelihood of engaging in CE.

Prevalence across substance classes

This study examined the prevalence of consuming legal (twelve-month use), prescription (twelve-month use, lifetime use and use willingness), and illegal substances (twelve-month and lifetime use) with the intention of increasing cognitive performance. Our results show that the most common legal substances used for CE are caffeinated drinks (including energy drinks and mate), with six in ten respondents consuming them on a daily basis. The use of food supplements and home remedies (such as ginkgo or guarana), including their daily use, was only reported by half as many respondents (three in ten). Although definitions of CE, sampling strategies, populations, and other study features differ across prior studies, our results seem to resemble that of previous studies, showing that a large share of respondents consume these legal substances, or so-called “soft enhancers” (Bagusat et al. Citation2018; Brand and Koch Citation2016). Another drug often investigated under the term “soft enhancers” is the caffeine tablet, which was used much less frequently than the other soft enhancers examined in our study. Our data show that only a small share of respondents use caffeine tablets, and those who consume them do so at frequencies that are substantially lower than consumption reported in a smaller-scale self-selective university student sample (Brand and Koch Citation2016) or a self-selected sample of surgeons (Franke et al. Citation2015), but comparable to that of a larger-scale random university student sample (Middendorf, Poskowsky, and Becker Citation2015).

Although our observed lifetime prevalence of prescription drugs used for CE (5.5%) generally falls within the range of prior population-based studies, our findings suggest a somewhat higher prevalence than most prior studies in Germany (Bagusat et al. Citation2018; Hoebel et al. Citation2011; Maier, Ferris, and Winstock Citation2018; Marschall et al. Citation2015; Sattler Citation2016; Sattler and Schunck Citation2016). We found that one-third of users reported consuming prescription drugs frequently over the past twelve months. This higher prevalence could be due to the different assessment strategies used across studies or may indicate an upward trend, albeit at a slower pace, than that predicted by media outlets and scholars (Partridge et al. Citation2011; Schäfer Citation2018).

One explanation of the increasing trends could be an increasing awareness of the possibilities for using prescription drugs for CE combined with use willingness rates that were substantially higher than actual prevalence rates (Marschall et al. Citation2015; Sattler and Schunck Citation2016; Wiegel et al. Citation2016). While the former might be attributed to a media hype (Partridge et al. Citation2011) and social influences, such as peers through which information about drug use can be distributed (Huber, Sattler, and Mehlkop Citation2023; Jain and Humienny Citation2020), the comparatively lower prevalence has been attributed to a lack of opportunity or access among individuals willing to engage in CE. The higher willingness, compared to actual use, in our results (even when strictly defining willingness as respondents who indicated “absolutely” willing) may indicate a further increase in the prevalence over time. Interestingly, use willingness can be described as a one-dimensional construct given the high covariance shared by the nine use purposes (i.e., to improve memorization or concentration). This may indicate that users prefer or reject CE regardless of the specific enhancement of a certain cognitive functioning, which would be in line with the finding that many people may hold strong moral objections against the use of prescription drugs for enhancement purposes (Champagne, Gardner, and Dommett Citation2019; Huber, Sattler, and Mehlkop Citation2023; Schelle et al. Citation2014). Our data also suggest that illegal drugs, such as cocaine and especially cannabis, are used with the intention to enhance cognitive performance. This finding has also been reported in prior studies involving various populations (Heller et al. Citation2022; Maier, Ferris, and Winstock Citation2018), showing that different substance classes are recognized and consumed as cognitive enhancers. When combining the lifetime prevalence of illegal and prescription drugs, as reported in other studies (e.g., Franke et al. Citation2013), we find 16.0% of respondents reported such use.

Polydrug use

Of particular interest is the use of multiple drugs and substance classes (Catherine, Williams, and Gabe Citation2019; Schelle et al. Citation2015). A general observation from our study is that those who report the use of a substance or class of substances for CE (e.g., report caffeine tablet use) have higher prevalence rates of using other substances as compared to the full sample (e.g., higher prevalence rates of illegal drug use than respondents who do not report caffeine tablet use). However, the strength of associations between substances in different classes was very low, while associations of moderate size were found for use of substances within the same class, i.e., between caffeinated drinks and food supplements and home remedies as well as between cannabis use and the use of other illegal drugs. These findings can be indicative, for example, of similar antecedents that trigger consumption of different substances or the use of a certain substance to increase or counteract the functioning of another substance (Kandel and Kandel Citation2015). For instance, caffeine pills or caffeinated drinks may be used, not only to attenuate the sedation caused by antipsychotic drugs, but also to modify the activity of enzymes metabolizing such drugs, with occasional deleterious consequences (Tantcheva-Poór et al. Citation1999; Thompson et al. Citation2014; Yartsev and Peisah Citation2021). While it is plausible that the use of drugs with lower barriers to access and possibly lower risks (e.g., caffeine tablets vs. illegal drugs) could initiate further substance use (i.e., experimenting with illicit substances after trying legal substances) (Franke Citation2019; Heller et al. Citation2022; Kandel and Kandel Citation2015), we only observed weak effects regarding overlaps between different drug classes. However, we cannot break down the temporal order of the use of different drugs, hence future longitudinal studies are needed to understand the causal ordering of the relationships.

Variation across respondents

This study also aimed to describe variation in using different substances for CE across ascriptive and achieved sociodemographic characteristics. The results provided evidence for such variation across all examined sociodemographic groups. The discussion of these results should be seen as a first interpretation of the findings and an attempt to understand the observed variation, rather than testing theory-driven hypotheses.

Sex

We observed an elevated prevalence of prior twelve-month use of caffeine tablets and the lifetime use of all illegal drugs among males as compared to females, but no further substantial differences in the use of other substances or across other observational periods. These findings resemble the previously reported inconclusive effects of sex – while some prior findings suggest higher prevalence rates or use willingness among males (Ponnet et al. Citation2015; Schröder et al. Citation2015; Singh, Bard, and Jackson Citation2014), a few studies found higher use or willingness levels among females (Hoebel et al. Citation2011; Sattler and Schunck Citation2016), and many other studies detected no sex differences (Sattler and Schunck Citation2016; Sattler and Wiegel Citation2013; Weyandt et al. Citation2009; Wolff and Brand Citation2013). Different reasons have been postulated to account for the higher prevalence rates among males, such as the gender roles which encourage males to be more competitive, ambitious, serve as the breadwinner; and that males have a more risk-prone personality (Sattler Citation2019), while the latter might be especially relevant for the observed use of illegal drugs. The higher consumption of illegal drugs also resembles the finding that males are more likely to engage in norm-violating behavior (Mears, Ploeger, and Warr Citation1998; Zimmerman and Messner Citation2010).

Age

We found much age-variation in the substance use measures, except for food supplements and home remedies as well as willingness to use prescription drugs. The observed variation points toward three general patterns: 1. The use of caffeinated beverages and caffeine tablets for CE tends to be equally likely within the age groups 35–44 and below (with few exceptions), but higher than in the older groups which are again relatively similar in their likelihood to use such substances; 2. Prescription drug use for CE seems to have a more U-shaped distribution, with the age group 35–44 and 45–55 tending to be less likely to have used prescription drugs for CE than those younger or older; 3. For all illegal drug uses, there seems to be a tendency toward an age-related decline in use (especially in those older than 25–34), meaning that use prevalence generally decreases with age. Most investigations of prior prescription drug use revealed no or limited age effects (Ponnet et al. Citation2015; Sattler and Schunck Citation2016; Wolff and Brand Citation2013), while some findings suggest that CE is more prevalent among younger age groups (Hoebel et al. Citation2011; Maier, Haug, and Schaub Citation2015; Novak et al. Citation2007; Schröder et al. Citation2015). Younger age groups might be more drug prone (especially to use the potentially more dangerous illegal drugs) not only due to their higher risk tolerance and neglect of side effects (Dohmen et al. Citation2005; Sattler and Wiegel Citation2013) but also due to specific common age-related demands (e.g., labor market entry). Additionally, the more permissive attitudes regarding drug use among young people in our sample may be indicative of the beginning of a value change in which young people are early adopters (Anon Citation2021. Conversely, the higher likelihood of reporting the use of prescription drugs for CE among the older and the oldest cohort may reflect a desire to counteract age-related cognitive deterioration (Forsberg et al. Citation2017; O’Connor and Nagel Citation2017).

Education

Our results suggest elevated prevalence rates among respondents with certain educational degrees. For example, respondents in the Secondary II education group and those with a university entrance qualification were most likely to have used caffeine tablets for CE. While some previous research found a negative association between years of education and prior prescription drug use for CE (Sattler and Schunck Citation2016) as well as no variation in such behavior (Bagusat et al. Citation2018; Hoebel et al. Citation2011; Marschall et al. Citation2015) or use willingness (Sattler and Schunck Citation2016), we found that individuals with tertiary education were less likely to report prescription drug use over the past twelve months, compared to respondents with lower levels of education. Respondents with tertiary education also had a substantially lower likelihood of using other illegal drugs for CE over the past twelve months. Potential explanations of this variation include that individuals with higher levels of education may have more awareness about the limited efficacy of using such drugs for enhancement, while those with lower levels of education may have a greater need to compensate for lower chances in the labor market (Sattler and Schunck Citation2016). Thus, further research is needed to examine the mechanisms behind the observed pattern.

Employment status

Respondents employed full-time have a particularly high prevalence of caffeine tablet consumption for enhancement purposes, especially compared to unemployed respondents. Our findings resemble some studies which found no differences in prescription drug use between full-time and part-time employees (Maier, Haug, and Schaub Citation2015), but differ from other studies showing higher use among respondents working more than 40 hours per week compared to those working 20 to 40 hours (Hoebel et al. Citation2011). While it has been speculated that consuming substances for CE is especially common during education (Weyandt et al. Citation2009), those in education interestingly do not appear more likely to use substances for CE in our study. Respondents in education reported twelve-month prevalence of caffeine tablets and prescription drug use as well as twelve-month and lifetime use of other illegal drugs that was often lower than that among those employed full-time and those employed-part time. This higher prevalence of certain substances among employed respondents – in comparison to respondents who are unemployed and in education – could reflect an effort to cope with work demands (Baum, Sattler, and Reimann Citation2023).

Income

We observed an elevated use of illegal drugs for CE among the middle-income group (regarding lifetime prevalence) and the higher-income group (regarding twelve-month prevalence). Although the impact of economic resources on CE has been rarely examined, one previous study found no relation between economic wealth and the use of prescription drugs (Maier, Haug, and Schaub Citation2016; Sattler and Schunck Citation2016). Nevertheless, a higher income may indicate more financial resources to acquire CE drugs (Baum, Sattler, and Reimann Citation2023). Indeed, some illegal drugs may be expensive and, thus, make it difficult for low-income people to purchase them. However, our results also show that having a lower income was associated with higher prevalence rates for prescription drugs (lifetime and twelve months) as well as cannabis (twelve months). Future research should, therefore, investigate the possible reason(s) for this variation across income, for example, whether certain enhancement drugs might be instrumentalized among individuals with low incomes to compensate for a lack of other resources that allow for upward mobility in the job market.

Partner

Being in a partnership might have health-protective effects, such as coping with stress (Carr and Springer Citation2010; Thoits Citation2011), and serve as a social control that deters engagement in risky and illegal behavior, such as substance (mis-)use (Jang et al. Citation2018; Laub, Nagin, and Sampson Citation1998). Therefore, having a partner may reduce the use of CE drugs. In support of the assumption that having a partner in the household decreases the use of CE drugs, our results show that respondents in such relationships were less likely to report the use caffeine tablets for CE. Conversely, previous research (which did not differentiate between cognitive and mood enhancement) found no such effect of being in a stable relationship on prescription drug use in bivariate analyses and even a positive effect in multivariate analyses (Maier, Haug, and Schaub Citation2015).

Place of residence

In our study, we found a higher prevalence of illegal drug use for CE in urban settings, as compared to rural settings. These results are similar to a recent study involving students which found that those in urban areas were more likely to use prescription drugs to help study (Teter et al. Citation2020). However, we do not know of any population-based study investigating the relation between place of residence (in terms of rural vs. urban) and CE. One interpretation of our findings might be that there is greater access to such drugs in urban settings (Galea, Rudenstine, and Vlahov Citation2005) and increased familiarity with drug use due to proximity to social places/events where such drug use is common (such as partying and clubbing) (Metzler Citation2003).

Diagnosis of mental illness

Individuals with a mental illness (both those recovered and still undergoing treatment) have a higher likelihood of reporting the CE use of all investigated substances (except of caffeinated drinks). More recent research also found a higher prevalence of prescription drug use for cognitive and mood enhancement among individuals receiving medical treatment for a mental disorder (Maier, Haug, and Schaub Citation2015) and a higher prevalence of prescription drug use for cognitive enhancement among those reporting depressive symptoms (Heller et al. Citation2022). It is worth noting that we explicitly asked respondents to only indicate their use of prescription drugs for CE which was not advised by a doctor for the treatment of a specific illness. However, using different drugs (including prescription drugs) with the intention to enhance performance could be due to various reasons, such as self-medication due to lowered performance that might accompany the illness (Khantzian Citation1997), a positive experience with prescription drugs during treatment, or better access to such drugs (including leftover drugs) to be misused. Moreover, it is possible that the diagnosis is the result of an attempt to feign symptoms to access prescription drugs and, therefore, is not valid (van Veen et al. Citation2021).

Limitations of the study and directions for future research

Our study has both its advantages and disadvantages, particularly regarding sampling design. On the one hand, our offline recruited nationwide sample of residents in Germany (see Methods section) is more representative of the general population than the convenience samples often used in CE research. On the other hand, survey uptake was partially selective as women, younger individuals, and those with less education were underrepresented. Although online surveys are very cost-effective and convenient for individuals to respond without restrictions regarding pace, time, and space or fear regarding possible judgment about responses by interviewers (see next point about social desirability bias), they are known for being subject to such selective survey uptake. However, to counteract this problem and to increase the representativeness of the sample in regard to the general adult population in Germany, we used sampling weights.

Furthermore, our study is based on self-reported data, which are subject to social desirability bias. The use of web-based surveys, as compared to interviewer-based surveys, however, may increase the likelihood of disclosing sensitive information (Kreuter, Presser, and Tourangeau Citation2008). Moreover, respondents were made aware that their responses would remain anonymous (Ong and Weiss Citation2000) and only a very small minority of less than one percent of the respondents expected their responses to not remain confidential. Also, a sensitivity analysis showed the results remain stable when controlling for anonymity perceptions. We also examined the data for a potential item non-response (in our case, the use of the response option “no response,” since a continuation of the survey without any response was not possible) and or unit nonresponse bias (dropping out of the survey on the page asking about substance use or use willingness). However, we only observed very small dropout rates ranging from 36 out of 25,865 (0.1%) raw unweighted cases for the survey page on which the frequency of using prescription drugs for CE was assessed to 47 out of 25,243 (0.2%) for the page on which the frequency of using illegal drugs for CE was assessed. Also, item nonresponse rarely occurred – as it ranged from 24 out of 25,288 (0.1%) responses regarding the question about the lifetime frequency of using prescription drugs for CE to 194 out of 25,234 (0.8%) responses regarding the twelve-month frequency of using cannabis for CE. This indicates that few respondents likely dropped out or answered “no response” due to sensitive nature of the topic. Hence, the potential nonresponse bias seems overall very low. While we specifically asked respondents about their substance use to enhance their cognitive performance (for legal and illegal drugs, we explicitly mentioned that no other reasons for intake should be indicated; for prescription drugs, we explicitly stressed that the respective use should not have been advised by a doctor for treating an illness), we have to rely on their self-reports and cannot exclude the possibility that substance use other than for CE was mentioned. As this study was focused on the use of different substances for the specific purpose of cognitive enhancement, we did not assess the general prevalence irrespective of this purpose, although this is an interesting addition which we suggest for future studies. Moreover, given more recent discussions about concerns of an increase in psychedelic microdosing (Lea et al. Citation2020; Petranker et al. Citation2022) such use intended to enhance performance should be also specifically assessed.

We must acknowledge that during the assessment of prescription drugs used for CE, the substance “Guanfacin” was incorrectly included in a list of substances within a response category to assess other prescription stimulant drugs (e.g., Atomoxetine [e.g., the brand name Strattera] and Dexamphetamine [e.g., Attentin]), while it is a selective α2A adrenergic receptor agonist that is used to treat ADHD. This is only relevant for Panel B in . In this Panel, the numbers meant to represent prescription stimulant drugs include an additional four individuals whose responses (unweighted, i.e., raw data) from open-ended answers were coded into the category other prescription stimulant drugs for the period before the past 12 months used for CE prescription drugs (no such answers existed for the past 12 months). We have verified that none of these refer to Guanfacine. If we exclude the entire category (Panel B in ) which also lists drugs other than Guanfacine (without those added via the open-ended response option) in the prevalence of prescription stimulant drugs, the prevalence of prescription stimulant drugs used during the past twelve months changes from 11.1% to 9.9% and from 15.4% to 13.3% for those used before the past twelve months. However, the exclusion of the entire category can be seen as too rigid since it would imply that no other prescription stimulant drugs would have been considered. Given that Guanfacine is only one active agent, we believe that the mistake may have hardly affected the results and our conclusions. Still, future studies using the same or similar assessment strategies to our study should refine the item.

We also particularly encourage studies to engage in the theoretical development of the associations found here, whose mechanisms have not yet been tested as well as those derived from relevant theories (e.g., Social Learning Theory (Ford and Ong Citation2014; Huber, Sattler, and Mehlkop Citation2023); the Theory of Normative Social Behavior (Rimal and Real Citation2005; Rimal et al. Citation2005); Outcome Expectancy Theory (Jain and Humienny Citation2020; Jones, Corbin, and Fromme Citation2001), or Strain Theory (Ford and Schroeder Citation2009; Ford and Yohros Citation2018)).

Conclusion

This study delivers a detailed description of the prevalence of the use of different substances that individuals believe can increase their cognitive performance, and the extent of the prevalence rates across different sociodemographic groups in Germany. Thus, this study extends beyond research involving smaller, partially selective samples and research that simply focuses on subpopulations (e.g., university students or employees) and contributes to the understanding of substance-based CE in Germany. Our results suggest that the prevalence of drugs used for enhancement purposes varies across drug types and sociodemographic characteristics, with legal drugs being the most prevalent. From a public health, occupational health, and policy perspective, one key question is when to begin to react to a problem and allocate resources to solving it, for example, whether this should begin when a problem is omnipresent, on the rise, or relatively stable on a moderate level or, for example, when the majority of stakeholders, such as the public or health professionals, consider it immoral. While we cannot answer this question here, our data suggest that especially dangerous forms of CE, e.g., with highly addictive illegal drugs, seem to be used only by a minority of the population in Germany. Although CE use is not an omnipresent phenomenon and its “hype” seems not to be justified (Allen and Strand Citation2015; Ferrari Citation2011; Partridge et al. Citation2011), the use of prescription drugs for CE may still amount to approximately 2.5 million users in the past year and 3 million lifetime users in Germany according to our prevalence data.