ABSTRACT

During the 1790s Britain experienced a series of poor harvests which, given an expanding population and wartime disruption to the European grain trade, caused sudden and rapid increases in the domestic price of wheat. In modern discussion of Corn and Poor Laws the severity of these fluctuations has been obscured by the use of annual average grain prices, despite weekly county prices being available from 1771 as published in the London Gazette. We highlight the uncertainties of grain prices during the period 1794-96, drawing upon contemporary discussion published in the Annals of Agriculture of the problems arising from fluctuations in the price of wheat. Our purpose is to demonstrate that the tropes usually today associated with the Corn and Poor Laws – pauperism, a clash between merchant, manufacturing and landlord interests, population and impoverishment – are absent from discussion during this period. A doctrinaire “political economy” would develop in the early 1800s, but did not yet exist. Policy argument drew upon casuistic reasoning from circumstance and past experience. We also show in conclusion that Edmund Burke’s Thoughts and Details on Scarcity cannot be linked to “political economy”.

While it has long been accepted that Britain underwent the first Industrial Revolution between the last third of the eighteenth century and the first third of the nineteenth, the processes that initiated and sustained this transformation remain today a matter of ever-more technical debate among economic historians. Arnold Toynbee’s Lectures on the Industrial Revolution in England (1884) originated the historiography,Footnote1 adding to it the idea that this economic transformation was accompanied by an intellectual transformation: the creation of an English Political Economy associated primarily with David Ricardo, who ‘lived in the midst’ of an industrial revolution,Footnote2 unlike his predecessor Adam Smith. Toynbee’s grasp of Ricardo was shaky, but as an Oxford student he would have been familiar with Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, which was a set text for Pass degree students like Toynbee.Footnote3 Nonetheless, he argued that it was Ricardo, not Smith, who appeared to contemporaries as ‘the revealer of a new gospel’, although his followers were said to be blinded to the importance of observation by their adherence to deductivism.

According to Toynbee, competition was the leading idea of Ricardo’s political economy; and this neatly links to the treatment of the industrial revolution and Ricardian political economy in the work of another significant writer, Karl Polanyi’s Great Transformation (1944). Like the ‘industrial revolution’ that Toynbee put into circulation, this ‘great transformation’, the emergence of a market economy, remains a powerful popular myth that continues to make some sort of sense of the multiple transformations of the global economy since the later eighteenth century. Central to Polanyi’s story is what the market economy did to labour, destroying the ‘traditional fabric of society’ and in the process creating a ‘free labour market’ that eventually turned out to have benefits for all concerned. However the emergence of a competitive labour market was delayed: ‘During the most active period of the Industrial Revolution, from 1795 to 1834, the creating of a labour market in England was prevented through the Speenhamland Law.’Footnote4 Named as such after a decision made by Berkshire Justices of the Peace in May 1795 to create a sliding scale of poor relief for the working poor according to household size, Polanyi argued that the measure pauperised workers, hindering the transition to a free labour market with the New Poor Law of 1834. Here he unwittingly repeated the mythology of the Old Poor Law advanced by the architects of the New Poor Law, Nassau Senior and Edwin Chadwick, who employed the data they had collected only to confirm their prior doctrinal beliefs. This mythology had duly become received wisdom; not until the 1960s were the flaws in this story exposed.Footnote5

The forty years between 1795 and 1834 form the space on to which arguments about Britain’s industrial transformation are projected, yet for much of this period Britain was primarily an agrarian economy, with the great majority of the population living outside major cities, engaged in agriculture, small-scale manufacture and handicrafts, depending throughout the period on the same road network, rivers, canals and coastal shipping. Only in the course of the Crimean War of 1853 to 1856 did the British Army complete a transition to a rifled, muzzle-loading musket that replaced a smoothbore originating in the early eighteenth century. Charles Dickens’ first novel, Pickwick Papers, was published in 1836, supposedly depicting events in 1827–28, but the world in which the action is placed would have been equally familiar fifty years earlier. While in the early nineteenth century a new world did begin to form within the old order, we should take care not to project the ideas and assumptions of the former prematurely on to the latter.

Polanyi was not wrong to identify poor relief as a potential wedge issue, but he was wrong to see ‘Speenhamland’ as a turning point. This essay seeks to explain why this is so, while recognising that in the first three decades of the nineteenth century the new discourse of political economy developed arguments about wage labour, pauperism and the relationship between rents, wages and profits that sought to influence legislative action, all of which postdated ‘1795’ both chronologically and epistemologically. Robert Malthus’s Essay on Population (1798), his Investigation of the Cause of the Present High Price of Provisions (1800), Ricardo’s Essay on Profits (1815), along with Sir Frederick Eden’s State of the Poor (1797) – in 1795 these all lay in the future. Edmund Burke’s Thoughts and Details on Scarcity was drafted during the autumn of 1795 and it has been suggested in recent years that Burke draws here upon a contemporary discourse of political economy, creating a new link between 1795, 1815 and 1834. We will show that there is however no plausible linkage between Burke’s text and what shortly afterwards became known as political economy, while such analysis as he offered also failed to engage with contemporary debate.

This essay turns away from canonical names to consider instead how this contemporary debate reflected changing agrarian market conditions, adopting the perspective of the Annals of Agriculture. This was a serial initiated by Arthur Young and published from 1784 to 1808, primarily aimed at diffusing agricultural knowledge but during times of dearth and high prices carrying a great deal of commentary from local contributors. In late 1795 it also included a large amount of Parliamentary material, although the relatively limited pamphlet literature of the time was never systematically reviewed.Footnote6 The primary context that we will work from here is not one formed by texts and ideas, but instead the perspective supplied by the Annals together with the London Gazette grain prices, presenting current prices of wheat as they appeared to contemporaries, using the data available to them, the better to understand their responses.

It is commonplace in modern commentary to use annual average prices for grain as an empirical referent, especially since so much recent historical research has been directed to the macroeconomic abstractions of a long-run annual rate of growth. This focus upon the long period disregards entirely the short-term price fluctuations that were the immediate contemporary experience; indeed, treats them as statistical noise to be smoothed away. We use here instead the weekly county average prices available since 1771, acknowledging their imperfections but demonstrating how much information they nevertheless contain. By taking the period 1794–96, during which a mediocre wheat harvest was followed by a very poor one, we aim to restore a perspective upon the dynamics of debate upon food, population and profits before it became the stock in trade of a new political economy. If we can in this way restore a contemporary perspective upon pauperism and market regulation, we might in turn cast fresh light on the post-Napoleonic period, when a new political economy positioned itself as a provider of legislative counsel on wages and welfare. The crisis of 1794–96 provides a baseline in which familiar problems of pauperism and price fluctuations arose, but at a time when the doctrines in terms of which they have since been read did not yet exist. Hence our focus upon how contemporaries understood the issues with which they were confronted.Footnote7

By examining just two successive harvest years we can also set aside most of the issues over which agrarian historians have argued during the last hundred years or more – landholding and access to common land, the scale and impact of parliamentary enclosure, the size and occupational composition of the rural working population, crop yields, labour productivity, shifts in land-use between arable and pasture, crop courses and labour requirements, Poor Law expenditure, settlement and migration – all these are here set to one side. This is not to say that these factors are unimportant or insignificant, but during the short period we have in view here none of them was capable of making a significant change to output: none addressed the eternal problem of fluctuating harvests, hence could not shift the boundaries of expectations regarding food security. Furthermore, although by no means a perfect cross-section of a rural intelligentsia, the contributors to the Annals of Agriculture can be credited with having a more consistent and local appreciation of agricultural matters than the average member of parliament, many of whose connection to a constituency was purely nominal.Footnote8

The first section outlines the process by which grain moves from field to final consumption. Treating ‘the grain market’ as a sequence of actions and transactions in time enables us to better understand the significance of sudden shifts in prices, or indeed a lack of any such shift, in the context of the various factors at work through the harvest year. And this latter concept is employed here in place of the more usual calendar year, reorienting our perspective to the actual rhythm in which grain is produced, supplied and consumed. We then outline the regulatory framework within which the grain market operated: the Corn Laws, the Poor Laws, and the Assize of Bread. These long-established bodies of legislation sought to manage respectively the domestic price of grain, welfare transfers to the poor, elderly and indigent, and the retail price and quality of bread.Footnote9 We then emphasise how limited was the market information available in the 1790s regarding the production, sale and distribution of grain, besides the current and past prices; and the efforts made to remedy this deficiency. The Annals of Agriculture is important here, for while it was originally conceived as a forum for the dissemination of information about agricultural improvement, during times of high prices it became an important medium for the collection, collation and discussion of information about prices, wages, yields and grain supply.

Then we turn in the second section to the data that we do have on grain prices,Footnote10 their strengths and limitations, and introduce graphics and tables designed to highlight the non-random features of price instability in the period under review. While the role of climate in harvest fluctuations has long been recognised, we are more concerned about ‘the weather’, the local impact of rainfall and temperature on crop yields. This relationship is only incompletely captured by records of national daily average temperatures or rainfall. Furthermore, while climate has long been linked to annual yield and so to actual supply, by our focus on the harvest year we are better able to capture patterns in price fluctuations relating to expectations about the likely size of the coming harvest, in part influenced by shifts in the current weather. Consequently we rely here more on contemporary description of changing weather patterns than on the data that is today available.

The third section outlines contributions to the Annals of Agriculture addressed to the problems created by the price fluctuations presented in Section 2, including the manner in which the Annals covered parliamentary debate on this matter. Discussion in the periodical began in early 1795, associated in particular with a questionnaire that Arthur Young circulated and which quickly drew a large number of responses. Not until the autumn, following the harvest of 1795, did parliamentary discussion begin, with the establishment of Select Committees on prices and proposals for legislative intervention. These are briefly reviewed before noting the shift during 1796 in the Annals towards institutional reform of the Poor Laws, rather than mitigation of the immediate situation faced by working households.

The final section presents Edmund Burke’s Thoughts and Details on Scarcity as a belated and unsuccessful intervention into both extra-parliamentary and parliamentary debate. Recent commentary has connected Burke’s analysis to arguments he supposedly found in Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, seeking a connection with an emergent political economy. We suggest in contrast that the new doctrines of political economy that would shape debate in the early nineteenth century about pauperism and the Corn Laws did not yet exist, and so could not be mobilised in discussion during 1794–96. Burke’s appraisal of wages and prices drew upon a legal framework, and did not anticipate what would would shortly become known as political economy.

1. The harvest year, the production cycle and market regulation

As noted above, modern literature on the Corn Laws tends to rely upon mean annual domestic prices of wheat, barley and oats in their discussion of the waxing and waning of debate over the threshold prices for imports and exports. However, annualised data eliminates the problem with which we are here concerned: the nature and impact of short-term price fluctuations. The explicit purpose of the Corn Laws was to ensure a steady supply of grain at a price that rendered wheaten bread affordable for the great majority of the population, and in the later eighteenth century this price was thought to be about 60s. a quarter.Footnote11 The poorer the household, the greater its reliance on bread for basic nutrition; while agricultural labourers generally considered white wheaten bread essential for adequate nutrition, rendering demand for it relatively inelastic to price changes.

The annual averages employed in modern accounts of ongoing parliamentary debate that, eventually, terminated in 1846 with the abolition of the Corn Laws are aggregated from weekly returns published since 1771 in the London Gazette.Footnote12 Until 1820 these recorded county average prices only, after that date recording price and quantities for each individual market. This was the primary source used for our period in the original archival research of American graduate students during the interwar years, chief among them Donald Grove Barnes, whose History of the English Corn Laws remains the standard work of reference.Footnote13 As we show in the following section, we should use this unaggregated data if we wish to understand contemporary debate over the price of grain, especially of wheat, and how prices might be managed. In so doing we also replace the calendar year as our base chronology with the harvest year – the twelve month period from the first days of September to the end of the following August, a year that begins at the point when the bulk of the English crops have just been harvested.Footnote14 Since the price during the following months is initially determined by the size and quality of the summer crop, then successively reflects the incidence of imports and of changing expectations regarding the coming crop, this provides a consistent chronology matching the issues with which we are here concerned. During the period under consideration wheat was sown in the autumn, while barley and oats were spring sown. Barley was primarily grown for distilling and malted for brewing beer; oats were in England primarily a fodder crop for horses, the principle power source for agriculture, transport and some early manufacturing enterprises where there was no suitable source of water.Footnote15 All grain crops were harvested in the summer, with an interval of around a month from south to north.Footnote16

Although some rural areas were predominantly pasture and others predominantly arable,Footnote17 at this time wheat was never sown on more than about one-third of the cultivated area and even in primarily arable areas shared courses with other crops.Footnote18 Much of the consumption of wheat was relatively local. Only London drew for its supply of grains on more than one region,Footnote19 and unlike in France there had never been formal impediments to the movement of grain out of area. The harvest period was succeeded by a lengthy period of threshing; combined with any carry-over from stored grain, new grain for consumption ordinarily first became available in late autumn. Minchinton noted for example that the harvest of 1800 was so poor that consumption in Warwickshire began immediately after threshing, implying that in more normal times local stocks were carried over for at least one or two months from the previous harvest year.Footnote20 Ploughing, harrowing and then the sowing of wheat would all have to take place before the weather deteriorated, the next burst of male agricultural activity being the spring sowing of barley and oats. For some three-quarters of the harvest year the wheat crop was in the ground, the future yield being affected adversely by the incidence of heavy rain, or lack of rain, or hard frosts, right up until the harvest began again. And even during the harvest weather conditions mattered: there was so much rain during the autumn of 1799 that the harvest dragged on for weeks, many fields in the north remaining unreaped in November, in some places the harvest even continuing to January.Footnote21

But where the latest crop was stored once threshed and sold off the farm, and who it belonged to, is a different matter. In his survey of the structure of the grain market HoldernessFootnote22 emphasises that we know very little about the sale and marketing of grain in this period, except that the long-established legal framework regulating market trading was relaxed in 1773 and selling by sample in corn exchanges became increasingly common. Joyce Burnette’s account of the seasonality of labour requirements based on farm accountsFootnote23 has shed light on the extent to which grain was retained on farm and threshed through the year, spreading out the demand for male agricultural labour but in any case implying that the larger the farm, the greater was the capacity for delaying sale.Footnote24 The reworking of Burnette’s data by Liam Brunt and Edmund Cannon has shed further light on the pattern of storage and threshing, noting that about 29% of wheat was threshed in the three months before the next harvest, implying that grain tended to be held on farm unthreshed, rather than by traders as grain.Footnote25

Nonetheless, the absence of information about the functioning of London wholesale and retail markets in the only recent article available underscores our continuing ignorance about the timing and volumes in the movement of grain from barn and outdoor storage to merchants to millers.Footnote26 We unfortunately have no reliable information on the relation of farm size to the timing of sales, other than its reflection in current prices. Because flour deteriorated quickly once milled the crop was usually stored unthreshed and then traded as grain, most parishes having a local mill, from the mid-eighteenth century most millers buying on their own account, milling and then trading over a ten-mile radius. The technology of both windmills and watermills was significantly improved in this period, slowing the adoption of steam-power which in any case brought hazards of its own: the very large Albion Mill in London was totally destroyed by fire in 1791 after only five years in operation.Footnote27 Nonetheless, at any one time significant amounts of London’s grain supply would have either been in transit, being milled or being turned into bread, something which in itself possibly had a stabilising effect on the weekly prices recorded for Middlesex (ie. London). Since London also was a port it can be anticipated that imported grain would quickly have entered this local chain.

The regulatory framework governing English and Welsh grain markets dated back to the early seventeenth century, addressing both the ways in which local markets should be conducted and the conditions for exports and/or imports.Footnote28 Foreign trade thresholds were periodically fixed that imposed duties on exports when domestic prices were high, permitted imports under the same conditions, while also providing bounties (subsidies) to merchants to export grain when domestic prices were low, securing revenue to farmers and encouraging them to maintain production of wheat. In fact, the government had no regular means of collecting information on grain prices, nor was any concerted effort made to enforce existing regulations. There were indeed no major periods of shortage during the first half of the eighteenth century; grain was exported and the population, even by contemporary estimates, was not increasing very much, if at all.Footnote29 As Barnes noted, the Corn Laws were not during this period a matter of any great public controversy.Footnote30 But from mid-century female ages at marriage fell slightly, the birth rate rose and the death rate fell. The population began to increase rapidly, grain exports declined, and in the latter part of the century the domestic supply of wheat came under pressure from rising domestic demand, a succession of poor harvests, and the disruption of international trade. In 1793 France declared war on Britain, and from that same year Britain became a net importer of grains until the later twentieth century. The inflection point in public debate came with the poor harvest of 1756, and from his study of the contemporary pamphlet literature Barnes concluded that at this point the high prices following a number of poor harvests were mainly blamed on middlemen – corn buyers (badgers, kidders, laders, broggers and carriers) but also assemblers and speculators (factors, jobbers, merchants, corn chandlers, millers, maltsters, mealmen, flourmen, bakers, brewers, distillers and taverners).Footnote31 Initially the most common solution advanced during the period 1756–1773 was to enforce Tudor statutes regulating their activities. However, attention soon switched from the role of the export bounty and middlemen to other factors:

Clearly, the most popular explanation was the wickedness of the middlemen. Adulteration of bread by the bakers, war taxes, national debt, corruption in court, luxury of all classes, payment of tithe in kind, enclosure and engrossing of farms, and bad harvests, all had their advocates. The remedies suggested, naturally, depended upon the explanation offered. To curb the middlemen the most popular suggestions were to enforce the laws against forestallers, engrossers and regrators; to forbid the exportation of grain; to prevent the use of grain in distilleries; to erect public granaries; and to place restrictions on combinations of corn dealers. Those who defended the middlemen insisted that the best way to secure relief was by protecting the latter from mobs. Pamphleteers who held bakers responsible believed that the best remedy was a new law regulating the assize of bread. Advocates of enclosure were convinced that the solution lay in extending the area of cultivation and in improving farming methods.Footnote32

The ensuing debate on the high price of grain now took a new turn: rather than seeking to identify conniving merchants, public concern shifted to the problem that the wages of male agricultural labourers were too low to subsist their families, even taking account of the paid work of females and children in the household. What we do not encounter in discussion at this time is any idea that the working poor deliberately formed large households so that they might live ‘on the parish’. This was a later narrative. In any case and as already noted, the increase in the rural population had begun in the mid-eighteenth century and by the end of the century was already into its second generation. This nullifies any argument that large and poor households were the consequence of overgenerous parish relief, rather than a rising population and higher prices being the cause of rising expenditure.Footnote36 As we shall see in Section 3, controversy about the role of parish relief in the pauperisation of agricultural labour is notably absent from the period we have in view here, but a brief outline of contemporary provisions will help contextualise this absence.

Legislation regarding the poor, old and indigent dates in England and Wales from the end of the sixteenth century, the parish being made responsible for levying and administering a local poor rate. While there was considerable discretion in the support offered to those settled in the parish, until the mid-eighteenth century the system primarily assisted paupers unable to support themselves, chiefly by placing them in workhouses or poorhouses. During the second half of the century assistance began to be provided in some localities to able-bodied workers, supporting the seasonally-unemployed by allocating them to farmers who were then subsidised by the parish. Exactly how widespread this and related measures were is unclear, since the first general survey of provision we have is for 1802–1803, and no systematic survey of the scattered sources that exist for the preceding period has yet been made. James HuzelFootnote37 does note that from the 1770s the existence of able-bodied men in need of relief began to appear in parish overseers’ account books, while an act 1782 for the first time included provisions for the relief of the able-bodied poor through monetary outdoor assistance. George Boyer likewise emphasised that payment of outdoor relief was widespread before 1795, and long recognised in the literature.Footnote38

But it was a meeting of Justices of the Peace on 6 May 1795 at the Pelican Inn, Speenhamland that came to symbolise a wholesale shift to outdoor relief and an allowance system – support for the working poor. The ‘Speenhamland System’ provided for payments to be made according to a sliding-scale of allowances calculated according to household size, payable to married men in work but who were unable to adequately support their families.Footnote39 In fact a similar scale had been proposed in Oxford that January,Footnote40 and as will become apparent in Section 3, ‘Speenhamland’ took a long time to enter circulation as an emblematic idea. The full scale was printed in Eden’s State of the Poor,Footnote41 but the ‘System’ was always more symbol than template. And as we can see in its use by Karl Polanyi, it has ever since generally been used symbolically, to condemn the pauperising impact of welfare payments, implicitly retrofitting arguments that first fully developed in the 1820s onto an earlier period in which they were rarely made. This will become very obvious when we come to discuss the response to dearth and high prices in the Annals of Agriculture.

The narrative regarding population, employment and welfare that prevailed from the 1820s to the 1960s was not widely employed during the period 1793–1815.Footnote42 As already noted with the work of Mark Blaug, the survey data collected during the 1820s and early 1830s was at the time never subjected to any systematic assessment, being used instead as a source of illustrative material for prior ideological positions. It was so easy to superimpose later prejudice onto previous conditions because there was in the later eighteenth century so little accessible and systematic evidence about population, employment and welfare: opinion trumped empirical fact. One thread running through the preceding discussion is the contemporary absence of consistent and comparable data on population, poor relief, crop yields, and imports and exports of grain. All contemporaries really had until the early 1800s was weekly grain prices from 1771, by county; while today some would claim that reliable runs of wages data have now been constructed, their confidence is today vigorously contested.Footnote43 The London Gazette grain prices do however turn out to be a very useful source, notwithstanding their multiple defects, a matter dealt with in the following section. While the collation and publication of national grain prices did begin with the London Gazette series, it was the crisis of 1795 that prompted the first systematic efforts to collect and collate information other than grain prices. Early in 1795 the Annals of Agriculture printed a questionnaire drafted by Young regarding the current stocks of grain, expectations of the next harvest, and the methods adopted for the relief of the poor. A minor deluge of letters and responses quickly followed. Then the Board of Agriculture, established with government support in 1794, quickly arranged for a comprehensive series of county reports to be made. In June 1795 the Board also

… proposed the issue of a questionnaire asking ‘the landed interest’: (i) What number of acres are, by estimation, or from regular survey, contained in your parish, constablewick, tithing, division, or district? and (ii) How many of such acres are arable, how many generally kept under each species of crop, how many in fallow, and how many in grass? A month later it sent out a statement ‘on the present scarcity of provision’ suggesting ‘measures to prevent any risk of real want previous to the ensuing harvest.’ The Board clearly stated that ‘the collecting of information respecting the agricultural state of the country’ was necessary before measures could be recommended to parliament.Footnote44

A final issue here is the role of stocks, alluded to above where we noted that, in the months following a harvest, the ownership and physical location of grain was not something local or central authorities knew very much about in the later eighteenth century. Recurring appeals for the establishment of public granaries capable of buying in during periods of low prices and releasing stocks during periods of high prices reflected a belief that the latter were more related to market failure than to an absolute shortfall. But stocks had to be held throughout the harvest year, and usually included some provision for the subsequent year as part of the normal inventory. Shortage in one year would be serially correlated with that of the next, so long as the harvest was not exceptionally large, since inventories would require restocking.Footnote47 Our working assumption here is that persistently high and increasing prices were a function primarily of harvest shortfall and the lack of sufficient and timely imports, rather than a consequence of market manipulation; and secondarily, of expectations about these factors. We now need to consider what we might learn from price movements during the two harvest years here under consideration.

2. Food security 1794–96: the variation and variability of grain prices

While Galpin and Barnes had made systematic use of the Gazette price series, they are not referred to at all in Deane and Cole’s British Economic Growth 1688–1959, a five and ten-year average wheat price index for the eighteenth centuryFootnote48 being based on Beveridge’s Prices and Wages.Footnote49 Boyd Hilton’s Corn, Cash, Commerce does have one table of monthly wheat prices 1812 to 1829,Footnote50 but these are taken from Tooke’s History of Prices without further comment, Hilton’s work being primarily a political history based on extensive documentary research. Even this monthly series is a national average, disregarding the availability from 1820 of weekly prices and quantities sold in local markets. Attention was once again drawn to the availability of the London Gazette series for local markets by Lucy Adrian in 1977, outlining some possible sources of inconsistency in variable definitions of the ‘market’ in space and time, but then making a local case study for Bury St. Edmunds during 1846–47 to test the reliability and utility of the returns that highlighted the role of transport costs in local variation.Footnote51

A comment published the following year questioned the value of the Gazette returns before 1821; but here Wray Vamplew addressed only national prices. Adrian had made no claim that national figures were reliable; she was interested not in national trends, rather in how local markets related to each other dynamically, the relationship between changes in their prices, not their relative level. In any case, Vamplew’s recalculations of annual averages for 1829–59 also show relatively minor variations: a maximum variance between the official and recalculated price of 2.5% for wheat and 8.1% for barley, with only two anomalous records.Footnote52

Vamplew’s emphasis upon the various sources of inconsistency in the Gazette data should by rights have simply reinforced a sceptical and cautious approach to the uses made of any economic data, especially the aggregated and inferential data upon which so much weight has come to be placed. Instead, Adrian’s innovative use of the Corn Returns simply disappeared from the literature, there being no further mention of her work until 2015.Footnote53 In 2013 Liam Brunt and Edmund Cannon provided a comprehensive account of the origin and development of the Corn Returns that neglected to mention Adrian’s work, while repeating some of the points she had already made.Footnote54 Nonetheless, their detailed survey of the background to and development of the Gazette price seriesFootnote55 concludes that the Corn Returns are the most important, and also reliable, source for British grain markets between 1770 and 1914, noting also that ‘They probably constitute the largest single body of data on the British economy before 1914.’Footnote56 Their more recent work on farm storage builds on this by using farm accounts to estimate the relationship between storage and sales – although in the case of 1794–96, with two successive poor harvests, stocks would have been very reduced and contributed to the acceleration of new sales off-farm.Footnote57

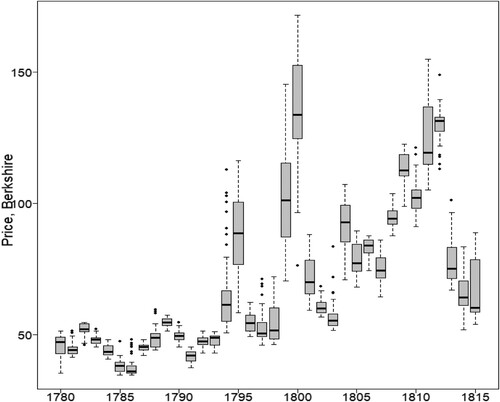

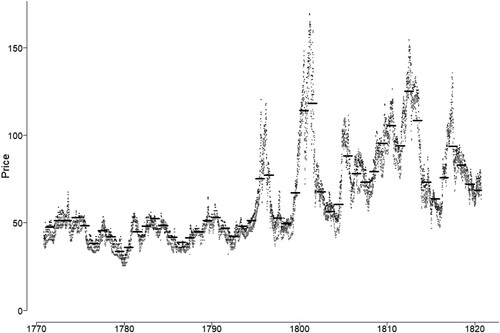

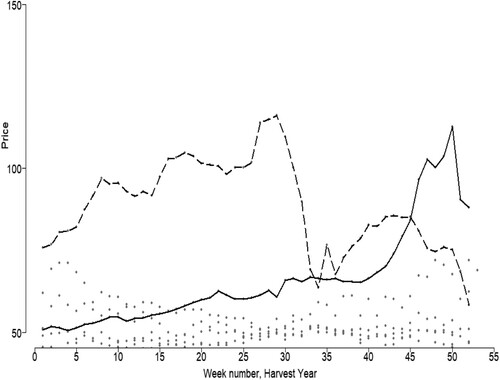

presents weekly prices from 1770 for London (Middlesex) and its related sources of coastal supply from Sussex, Kent and Norfolk. This isolates a distinct subgroup among English counties that was a distinct market and which also influenced national price formation. We use a scatter plot that clearly shows up several important points: that fluctuations were at times extreme; that prices in the four counties tended to move together; and that the dispersion between county prices was limited, and consistently so.

Figure 1. Comparison of Middlesex Wheat Prices (black dots) with Norfolk, Sussex, and Kent (grey dots), with calculated annual average as bars (calendar years, shillings per quarter).

The manner in which the construction of an annual average of these four series significantly moderates volatility is of course predictable, but all the same striking at times of high volatility. By construction the average yearly price follows the evolution of prices; shows however that the variability around the yearly average is large in particular in times of ‘crisis’, i.e. when prices are high. Since the weekly prices are those available to contemporaries and in terms of which they argued, their real evolution is important to our following discussion.

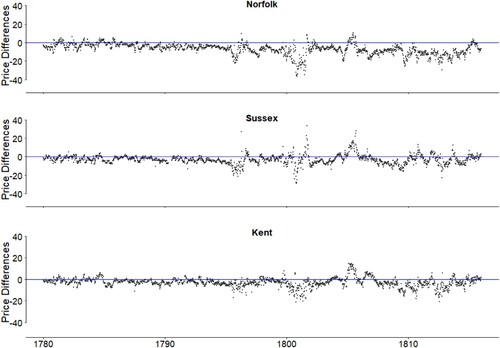

We examine the variation between Middlesex and the other counties in . This shows that there are sometimes large differences between the Middlesex weekly prices and those of the other counties. Each point represents the difference (in shillings) between the price in a given county and the price in Middlesex. There are sometimes large differences between the county weekly prices and Middlesex. In some cases (Norfolk) the differences can be long-lasting – Norfolk prices are more often than not below the prices for Middlesex, especially after 1800.

Figure 2. Weekly Price Differences (shillings per qr. of wheat) for Norfolk, Sussex and Kent with respect to Middlesex.

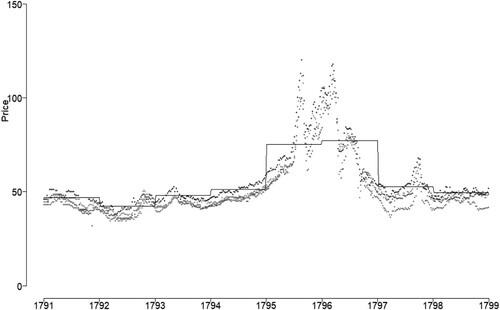

then focusses on the same four counties during the 1790s, it can be seen that while differences between county prices exist, opening out during periods of rapid upward change, but not downward, the pattern of fluctuation is common to all the counties.

Figure 3. Weekly Wheat Prices 1791–99 in shillings per quarter: scatter plot for Middlesex, Sussex, Kent, Norfolk, with annual average indicated by thick line segments.

A focus upon wheat prices for the same four counties during the 1790s demonstrates that while differences between county prices exist, opening out during periods of rapid upward change, but not downward, it is evident that the pattern of fluctuation is common to all the counties.

It was the meeting of Berkshire JPs at the Pelican Inn, Speenhamland in May 1795 that (eventually) put into circulation the idea that rising poor relief was due to subsidies paid to working adults on a sliding scale of the number of children in the household (outdoor relief), a practice which, it would later be said, diminished the incentive to work. Stated like that, there is a clear non-sequitur at work, but no matter: this was the idea with which Speenhamland became associated.

Our first point is that no reference to ‘Speenhamland’ can be found anywhere in the Annals of Agriculture before 1797, and even after Eden’s State of the Poor had highlighted the sliding scale in 1797, for a long time ‘Speenhamland’ did not represent a particular social policy. Indeed, searching local newspapers turns up only a brief report of the meeting, in The Courier for 13 May 1795, an item that was not repeated in other publications as seemed to be the practice at the time.

Why did the Berkshire magistrates meet and agree such a measure? If we examine the wheat prices for Berkshire we can perhaps gain some sense of the urgency they felt. While in the period 1794–96 the mean and the median price for the harvest year are throughout roughly the same, the story is very different if we look at the price in the first and the third quartiles – so September to November, and March to May. Up until September 1793 the prices are comparable, showing a marked increase for the third quartile in 1794 and almost doubling from first to third for 1795–96. The high prices beginning in 1808 do not show the same degree of peakiness – high prices certainly, but in a more sustained fashion. Given our working assumption, that it is rapid changes in prices rather than sustained high prices that created a sense of crisis, this provides some sort of general illumination of the situation facing the Berkshire JPs in May 1795. From it is evident that up until late 1794 prices fluctuated within a relatively predicable band. By early 1795 upward fluctuation had turned into a trend, creating a new situation compared with previous years. We suggest that it was this shift that created the sense of alarm first registered in Arthur Young’s January circular, and the responses to it. While it is true that, compared with subsequent prices changes, evident in , the 1795–96 crisis was on a smaller scale, the fact that this was a new phenomenon led to the reaction that we record in Section 3.

The following graph presents the same information as in ():

Table 1. Berkshire Wheat Prices 1780–1815 in shillings per quarter, harvest years commencing September of each calendar year.

The Figure show a box and whiskers plot of the prices in Berkshire for every year between 1780 and 1815. The length of the lower and upper limits of each box represent the first and third quartile of the distribution of prices in a particular year. The horizontal line within the box indicates the level of the median price that year (the means and medians are not that different in our data). The whiskers extend 1.5 of the interquartile range below the first quartile or above the third quartile. If the maximum price in that year is within 1.5 times the interquartile range above the third quartile, then the end of the whisker (upwards) is set at the maximum (similarly for the minimum). If there are instead some observations beyond this limit, each value is then plotted beyond, above or below, the whisker.

Early periods are characterised by less annual variability and relatively more stable prices, while the later years exhibit more price variability within a year (the size of the boxes and the length of the whiskers are larger). Years where the median prices are high correspond in general to periods of larger annual price variability (the interquartile range is wider), and in some cases (for example 1800) to a much wider difference between the smaller and the larger weekly price within that year (the distance between the end of the whiskers is larger).

We then plot on the same axes Berkshire wheat prices for each harvest year 1791–98 – from September of any given year to the end of the following August in the same figure. The evolution through a particular year is indicated by the week number (horizontal axis) while the vertical axis describes the price level. Here we can see more clearly the price evolution in May 1795 as compared with previous years. The continuous line shows the evolution of the price in 1794–95 and the dashed line for 1795–96. The scatter plot at the bottom represents the prices for all years, excluding 1794 and 1795. We observe therefore that for the two harvest years beginning 1794 and 1795 the price level changed relative to the other years, and that the evolution of prices over time differs between the harvest year 1794 and 1795. In 1794 high prices rose sharply at the end of the year, while in 1795 prices were relatively high early on and decreased later in the year. The abrupt fall around Week 30 reflects the impact of government sales and the arrival of private imports during March 1796 (from week 27 to 30).Footnote58 By contrast, the Berkshire magistrates seem to have been reacting to a sudden further surge in prices during April, while the fact that prices then remained the same until late June, only then resuming a rapid rise, might account for the lack of any immediate reaction to the Pelican Inn meeting. While prices did fall in August, they quickly returned to the same level and more, the distance between the autumn prices for 1794–95 and 1795–96 indicating quite why it was thought, during the autumn of 1795, that government intervention was needed ().

Figure 5. Graph for Evolution of Berkshire Wheat Prices over the Harvest Years 1791–98 (shillings per qr.).

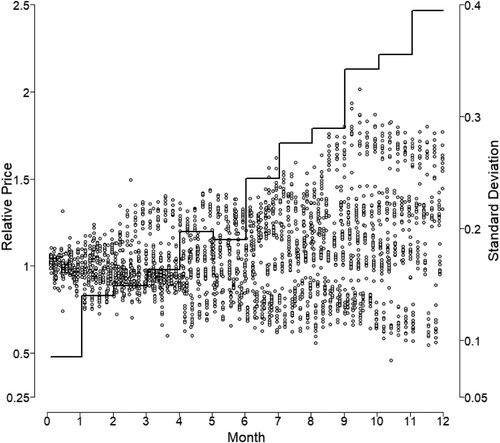

When a sudden upward price change occurs that appears to break with a previous pattern of price fluctuations it can generate an expectation that this change could become a new trend – a line of thought that we attribute to the Berkshire JPs. But the harvest year itself generated a pattern of expectations, deriving first from the sufficiency of the new harvest and modified by the weather pattern on the way to the next. After 1821 the Corn Returns were reported by market, and so instead of having 52 county observations for any one year, we have 52 observations times the number of reporting markets in the county – in our case of Norfolk, 572 local observations. This enables us to gauge the degree of variation of future prices relative to any point in the harvest year, and so gain some perspective on the expectations an actor on the selling (or buying) side might form of future prices. We wish to emphasise market participants did face considerable uncertainty regarding the evolution of market prices, which we highlight by using a harvest year to organise the data. As can be seen from the impact of government intervention on March 1796 prices in Berkshire, the sudden influx of imports could shift expectations of future prices for a while, but adverse weather conditions would alter expectations of future prices more directly.

We take wheat prices from eleven Norfolk marketsFootnote59 for the years October 1820 to July 1828, scaled by the average price in September for each market. The scaled prices are then on average equal to 1 in the September of each harvest year. We then overlay the weekly pricesFootnote60 in each market for several years on the weeks of one single (hypothetical) harvest year, giving 88 data points for each week. This figure suggest that from the point of view of the price information available when the harvest is collected uncertainty over prices for the coming year is large; prices can halve or double, increasing over time. We also show how the standard deviation of (the scaled) prices changes over the year (continuous step line).

While these prices necessarily come from a later period, they provide perspective on how expectations might form at an important point in the harvest year. It is clear that the market clearing process, even at a local level, provided wheat producers with a good idea of the ‘market price’ for wheat at the county level and at the national level. Careful planning under such conditions will be difficult. Storing grain in the hope that the price will double over a year would expose a merchant to a loss of half of the value of his stock if the price did not double. Similarly, selling all the stock at the current price leaves the producer exposed to substantial possible losses if the prices did increase – representing the opportunity cost of selling at a point prior to a subsequent rise in price. Those reliant on the grain for food would not be able to insure themselves in any way against such price volatility ().

Figure 6. Range of annual weekly prices relative to September in each Year, eleven local Norfolk Markets, October 1820-July 1828.

Our presentation of the London Gazette price data provides some insight into the responses to a sudden increase in the price of wheat that we review in the following section. Despite inherent limitations of the Corn Returns – local inconsistencies of measurement, in recording the returns, and the prevalence of selling by sample outside the local markets – this data provides us with a much richer understanding of the actual evolution of wheat prices than we have previously had for the 1790s, providing a richer context for the debates to which they gave rise.

3. The annals of agriculture

The Annals of Agriculture was a project initiated by Arthur Young in 1784Footnote61 publishing contributions relating to agricultural improvement of all kinds, much of it contributed by himself. The first volume was dated 1786, including material from some years earlier; and while there are some variations in the dating of volumes and contents, contributions were mostly printed in chronological sequence. Discussion of agricultural labour, of pauperism, of nutrition would suddenly become common only during times of rural distress. However, the issues that were of concern were not necessarily those we might anticipate from later debate on pauperism. Vol. XXII (1794) for example includes a contribution on the ‘causes of the alarming increase of the poor-rates, those most discouraging checks to all agricultural improvements’:

I am of opinion that there is a radical evil in our present poor-laws, which, if not speedily removed, will, in many populous villages in this kingdom, be attended with utter ruin to the small farmers. The evil I mean to point at, is the almost irresistible power of the overseers in their respective parishes, who, in many instances, which come under my own immediate observation, are landholders, who have received no advantage from education, and who are by routine put into office from their large occupations.Footnote62

Although Vol. XXIV (1795) is the second volume for this year, it begins with the January 1795 average prices for corn.Footnote63 Arthur Young included a ten-point questionnaire, dated 23 January 1795, relating to expressions of concern about a possible scarcity of provisions, covering: current stocks of wheat and rye relative to consumption until later in the year when the 1795 crop would be available; expectations (Young’s term) of the 1795 harvest, ‘relative to any deficiency which it is supposed may result from the autumnal rains and the present severe frost’; effective means for the relief of the poor; any increases in the pay of agricultural labour; the use of substitutes for wheaten bread; the present price of basic foodstuffs other than bread; the price of coal; the impact of the present frosts on fodder crops and young wheat; the price of hay and straw; and the price of wool.Footnote64 Young subsequently printed seventy-nine responsesFootnote65 covering 268 pages, dated up to May but for the most part originating in February, suggesting that writers recognised the immediacy of the issues Young raised. There was general agreement that the 1795 wheat harvest was up to 30% reduced, and that there were only limited stocks in hand. Views were mixed on the coming harvest – some positive, others negative (in February). In virtually all cases ‘the poor’ who were the object of concern were the working poor: males in regular employment but whose wages were too low given the current price of grain. Charity and public subscription were considered to be the primary means of ameliorating their lot, either by subsidising the price of flour, through the establishment of soup kitchens, or by direct cash payments from charitable funds. One example stands for may:

In the parish where I live, besides the frequent and private donations of the well disposed, a sum of money has been raised, with which flour is purchased, and retailed to every poor family, consisting of both or either parent and two or more children, at the rate of half a peck, weekly, to each, and at the price of one shilling and ninepence per peck, or seven shillings the bushel. This relief is also extended to the aged and infirm widows; persons not included under the above description, are relieved, weekly, by the overseer. Our fund, which has now lasted nine weeks, will probably carry us, in these weekly sales, to the month of June; and then, if the price of wheat remains (as most probably it will) as high as at present, the same relief must be extended till after next harvest; for it is not unreasonable to insist, that the labourer, let his industry be what it may, cannot support himself and a large family, under the existing circumstances of scarcity.Footnote66

In May Young summarised the responses he had received, taking each question in turn and reviewing the material by county. The first point that emerged was that the 1793 harvest had also been mostly deficient, so that in the summer of 1794 there were limited stocks in hand. He also emphasised the low rates of agricultural pay, and the advantages of piece rates – concluding that the increase of the Poor Rate reflected these low rates of pay. Few of his correspondents had in fact mentioned the Poor Rates, and Young dealt with the issue only in passing. Charitable giving was what he emphasised:

That the price has, for some months, been too high for the faculties of the poor cannot be doubted: charity, the most liberal and boundless, has done wonders for their assistance: it is however a reliance never to be desired; and that some legislative steps should be taken to procure a more enlarged supply, in future years, cannot be doubted.Footnote68

In July 1795 the Board of Agriculture circulated a note on ‘The Present Scarcity of Provisions’ which recommended wholegrain rather than white wheaten bread, and the reduction of wheat consumption by the substitution of vegetables, plus admixture with other grains and potato flour. The information they collected was to be placed before Parliament, which should seek to prevent future scarcity by statutory means, securing for the people ‘a sufficient quantity of nourishing food, at a reasonable price.’Footnote70 This emphasis upon practical measures that might effect a speedy amelioration of the impact of high wheat prices is quite typical of views expressed in mid-1795. Volume XXV is dated 1796, but continues on directly for the summer of 1795, with two contributions advocating the cultivation of waste land as a remedy for high prices, and a letter from Sir John Sinclair recommending the cultivation of potatoes.Footnote71 In October 1795 Arthur Young published a second circular, to update responses earlier in the year but also adding a new question, seeking views on the regulation of wages according to the price of ‘bread corn’.Footnote72 Responses initially focussed on the use of rice and potato as substitutes for wheat flour in the making of bread; some contributors noted the existence of supplementary wage payments; but striking in all of this discussion of wages, food substitutes, subsidies and soup kitchens, is the absence of any discussion of imports, their timing and impact upon prices. For his 1964 article on this period Walter Stern had searched through The Times newspaper for reports of both imports and the release of government stocks, concluding that their timing had a significant impact upon local fluctuations. There was however no discussion of this in the Annals, presumably because to do so would have opened up discussion of commercial matters, rather than those arising in the purely agrarian realm to which it was addressed.

During the autumn of 1795 the Annals printed a lengthy ‘Report on the Inquiry into the General State of the Poor’ commissioned by Hampshire JPs. This began with a review of farm labour, distinguishing between three broad classes of worker: domestic servants, those who work by the piece, and the daily or weekly waged. The first were farm servants living-in as single adults, contracted annually and paid from £5 to £9 per year. This group was the best off, since they were usually at least well-fed. Those working by piece were said to be able to earn 12s. to 15s. a week in summer, and 10s. to 12s. In winter. The precarious position of the third group is marked: those working for daily or weekly wages while most likely supporting a family as well were paid around 8s. a week, recently increased in some places to 9s. Here the Report suggested that letting of cottages with small plots of land would be a significant improvement, although there is no mention of the work done by other members of the household that would have improved the very poor pay of a male agricultural day labourer.Footnote73 Another problem identified is the reliance of such households on small shops; here it is recommended that as far as possible workers might be remunerated in kind, which would align more directly the interests of labourer and farmer. This leads on to wider issues of nutrition, one curious feature of which is an extended discussion of the deleterious effects of drinking tea as opposed to beer, arguing that ‘the obvious, the only remedy is the return to animal food and beer, those genuine supports of labour, of life, for which any other are vainly in effect, as cruelly in attempt, endeavoured to be substituted.’Footnote74 The Report then goes on to consider health, ‘houses of industry’ (workhouses), the training of boys and girls, and the proper use of the poor rate – primarily for the construction and maintenance of workhouses and associated provision for the training of juveniles. These were said to be ‘the chief means of reducing the poor rates’.Footnote75 While there is little or no direct discussion of outdoor relief, it is once again evident from this report that ‘the poor’ are identified with the ‘working poor’, the agricultural labour supplied by the three classes initially identified.

The final two hundred pages of Vol. XXV are dominated by the parliamentary proceedings of November and December 1795, beginning with a summary of the debate on 3 November 1795 in which Pitt, the Prime Minister, moved that a Select Committee on the high price of corn be formed, so that any measures taken were founded upon thorough investigation and deliberation. He also called for revision of the Assize of Bread to permit coarser flours to be used, or even maize and potato flours.Footnote76 The following speaker blamed the present scarcity on large farmers who were able to hold back from selling their grain, whereas the small farmer was obliged ‘to sell his grain, at any price it will bring, at the proper season.’Footnote77 To the cause of high prices he added the activities of corn jobbers and the practice of selling by sample – all arguments that were popular in the 1760s but which were largely absent from the Annals during 1795. Speaking in the same debate in response to Pitt, Charles Fox redirected the attention of the House to a failure of wages to keep up with prices, that in an ‘inclement season’ the ‘industrious poor’ were compelled to rely on the charity of the rich; although no form of coercion through the regulation of wages was thought appropriate, a principle with which Pitt agreed.Footnote78

Arthur Young commented at length on this, suggesting that the first task of the Select Committee was to familiarise itself with the facts:

The harvest was late, and little old stock on hand; the seed-time came suddenly with the rains, and the necessity of threshing one-tenth of the crop if it was an average one, or one-ninth or one-eighth if deficient, for seeding the ground, an operation not yet finished, must in the nature of things much impede the supply of the market, except for seed – wheat and rye. We see the effect of this in the price of barley, for all accounts from every part of the kingdom yet received by various persons agree that that crop was large; yet the price is very high, with the distillery stopped; this clearly and palpably proceeds from the threshers having been employed every where in threshing wheat-seed; till that is done, barley cannot, in the nature of things, fall to a price proportionate to the produce. In one month after wheat sowing is finished, this fact will be ascertainable. But the circumstance which most prevents the price from being a fair index of the crop, is alarm and apprehension of scarcity, which never fail raising the price much higher than the real deficiency of the crop would otherwise occasion. This was more apparent than in the preceding summer; when corn is rising with a general alarm, much is hoarded, in expectation of still higher prices. Men regret having sold too soon, and that induces others to keep back from market.Footnote79

On 13 December 1795 the House of Commons returned to the issue, the Annals reporting on a speech by Lord Sheffield (The Bristol MP John Baker Holroyd). He lent support to the contention that by the time of the 1794 harvest the usual four or five months’ stock in hand was almost exhausted, and far from the inventory being restored in 1795, that harvest was mostly very poor. While an abundant crop might more than meet consumption, Britain now consumed more grain than was produced in normal years, as demonstrated by the imports of the previous twelve years. His discussion of the possible source of imports, and the quantities required, stands in contrast to the arguments previously made by other Annals contributors, focussed more on charitable support to the poor either in money or in kind than on the fact that Britain was now a net importer of grain even in years of good harvests.

Channelling a line of argument that had occasionally surfaced in the Annals, on 9 December 1795 Samuel Whitbread had introduced a bill into the House that would enable JPs to regulate agricultural wages, an initiative that eventually went on to be defeated on 12 February 1796. The bill was presented not as an innovation, but as in the original Elizabethan spirit of the Poor Laws, which had aimed at fixing maximum, not minimum wages.Footnote81 Although Arthur Young and some of his contributors had earlier argued for the regulation of wages, 26 pages of responses published in the Annals from early January 1796 were mostly sceptical of Whitbread’s proposal, echoing recent Parliamentary debate.Footnote82 The argument that wages should be linked to average prices was complicated by the question of exactly when farmers sold their grain; hence to what extent farmers might benefit from high prices, and so could pass this on in the form of higher wages. There was however little information on this aspect of the present crisis besides anecdote. One such instance is that of Edmund Burke, who noted in his Thoughts and Details that in 1794–95 he had sold grain from his farm at £14 a load, thinking he had sold at the peak, which however then turned out to be later, when at the end of the season he could have got £30.Footnote83 While Charles Smith had in 1766 raised this issue in his Three Tracts – how farm size dictated the speed at which harvested grain entered the market – this was not during 1795 addressed in the pages of the Annals. However, Smith’s Three Tracts was republished in 1795;Footnote84 and it was Charles Smith, not Adam Smith, who was later cited in a Select Committee report.

The Select Committee on High Prices established by Pitt quickly produced its first report, on 16 November. Having reviewed the information available, the Committee had quickly established that, while the 1795 harvest had overall been abundant, in the case of wheat it had been so poor as to require immediate remedy. The most obvious course was importation; but review of the possible foreign sources concluded that there was a general shortage, that it was doubtful whether the domestic deficiency could be quickly or easily resolved in this way. The committee went on to consider the alternatives of government purchase, and that of individual traders enjoying a bounty on imports, which would compensate merchants for the expense of shipping grain from the Mediterranean, where there was thought to be an adequate supply.Footnote85 It was also reported that a considerable quantity of Indian Corn (maize) was available, and that offering a bounty on its importation would be of benefit. A Second Report followed shortly after, including rye in the proposed bounty payments and extending the period of time during which bounties would be paid.Footnote86

While this use of bounty payments to encourage imports was new, it was linked to the work of a parallel committee established to explore the issue of bringing waste land into cultivation. As already noted, this had long been advocated by Arthur Young, and the first report of this committee, largely written by Sir John Sinclair of the Board of Agriculture, repeated his arguments. The committee’s terms of reference were limited to the means of bringing waste land into use,Footnote87 and such reasons as were presented for so doing related to the provision of land to the rural poor, not directly the need to expand productive capacity. A later and more detailed report was reprinted in the Annals that looked forward to the end of the war, suggesting that

A disbanded fleet supplies our merchantmen with sailors, and may extend the fisheries on our coasts; but a disbanded army has hitherto had little resource, but emigration to our colonies, or to foreign countries, or resorting to manufactures, many of which require skill and experience in those who are employed in them. Since the introduction of machinery, however, great numbers of hands are less necessary for our manufactures than formerly; and thence the proper business for our disbanded soldiers would be the cultivation of the soil.Footnote88

From this account it appears, that 148,000 acres of additional cultivation, under these articles of produce, would have yielded the imported quantity; and consequently, that if such a breadth of waste land (capable of yielding these products) were in future to be added to the culture of the kingdom, there would not be a similar necessity for importation. Nor is that all: can any person doubt, that double the quantity of land wanted might be brought into cultivation, if the legislature would give such encouragement, or even permission, for that purpose. In that case, even in years of scarcity, there would be a sufficient quantity of grain for the consumption of the country; and in favourable seasons, there would be a considerable surplus, which, exported to other nations, would add to our commerce and our wealth.Footnote89

Besides reprinting reports from the Select Committee on the Present High Price of Provisions, during the early months of 1796 the Annals printed contributions concerned with the organisation by individual parish or union of ‘houses of industry’, taking their cue from a proposal by William Pitt.Footnote93 There was a marked shift from the tenor of discussion a year earlier, when contributors wrote of charitable aid, of payment in kind, and the baking of bread with alternative contents. By June 1796 one contributor advocated the payment of outdoor relief to the industrious poor, while containing the indigent in workhouses:

So far the plan of the houses of industry is preferable; but it fails in forcing all claimants into one place, away from their homes and friends, and where they are maintained at a dearer rate than they could be by weekly allowances at their respective homes. The present disadvantage of such weekly allowances is, that more paupers will apply for them, than would be willing to go into a house of industry, and it is by this, that the chief saving of houses of industry is made; but then this saving is made in rather an unjust way, by forcing the quiet and industrious to be pinched at home, while the idle and vicious have no aversion to go into the house altogether. The directly contrary practice ought to take place, of keeping all the quiet and industrious out of the house, so long as they are willing to accept of such weekly allowances as the body of overseers judge to be sufficient relief to them; they would then never throw themselves into the house, except from the most absolute necessity: there fore every parish ought to have a small poor house, to receive such paupers i.e. sickly and old men and women, and orphan children, and to treat them well. But the idle and vicious, who are contented with nothing allowed to them, ought to be disposed of in another manner; that is, in every hundred one house should be hired or erected for those only, who are idle, vicious, stealers of gates and bars, thieves, beggars, impudent whores, the insolent and disorderly, where they should be kept to close labour and harder fare, under more rigorous rules, and by a different body of managers from the body of overseers, but chosen by the body of overseers in the several parishes; and no person to be sent there without a written order from a justice of peace, after his being thoroughly informed of their characters and conduct: these are the only persons who ought to be removed from their parishes, and this as a punishment to them.Footnote94

It is very evident, from this last change, and the general scope of your correspondent's letter, that this workhouse, to be used as a house of correction, is chiefly intended for such POOR as are not satisfied with the allowance which the body of overseers, under the proposed new organization, by a majority of votes, may be disposed to grant them; or such as the overseers shall not think proper to have any allowance.Footnote95

4. Edmund Burke’s counsel

By 1815 arguments about pauperism and the Poor Laws had merged with those over the regulation of the grain trade and the management of the Corn Laws, reframing debate in terms of the relationship between rent, wages and profit. How far the emergence of a new political economy actually illuminated these issues is not an issue with which we can deal here. We can simply note that the casuistic approach to problems of grain production and supply and the price of bread for working families typical in 1795 and early 1796 was challenged by a new discourse based upon principles, on ‘theory’. As Ryan Walter has shown, during the mid-1790s ‘theory’ had only a negative connotation.Footnote96

Arthur Young expressed this very clearly in the context of the arguments we have been considering:

If the price of corn regulates the price of everything else, as has been contended, the result ought to have been fatal to our exports; but experience is a better master than theory: and here we find that, on the contrary, never have our manufactures been more flourishing, nor our commerce more extensive, than just in the very period when this prodigious rise of 81 per cent in bread corn ought, according to the principles of those writers, to have absolutely annihilated both. So very young are we in the science of politics; and so little dependence can we have on theories, built on any other basis than the only solid one of fact and experience.Footnote97

By way of conclusion we can assess the status of the arguments expressed in Thoughts and Details in the light of those made by Burke’s contemporaries, as outlined above; and also in terms of our argument that in 1795 the new discourse of political economy had not yet fully formed. We will show that there is no plausible linkage between Thoughts and Details and what soon afterwards became known as political economy. We will outline the arguments advanced in support of a linkage of Burke to political economy; then consider the arguments Burke advanced in 1795 as compared with those we have found in Annals of Agriculture for the same period, and which address the same substantive issues.

We here use the term ‘political economy’ in a very specific, doctrinal sense; contemporary usage did not (yet) associate the term with any particular body of ‘theory’. While Adam Smith did use the term ‘political oeconomy’ in the title to Book IV of the Wealth of Nations, this was a pejorative usage most likely angled against Sir James Steuart, who in his Principles of Political Œconomy (1767) was one of the very first users of the term in English, a neologism borrowed from the contemporary French économie politique. This did not however denote doctrine, as it would by the early 1800s, but policy. Smith himself never described Wealth of Nations as a book written in the genre of political oeconomy, although the term was coming into relatively common use by the 1780s as a general designation of policy, as in the French usage. Most striking is that a search of the Kress/Goldsmiths digital collection turns up only three instances of ‘political economist’ before 1800, all in the 1790s, whereas use of the term snowballed shortly afterwards.Footnote99

John Pocock noted the ‘varying degrees of specificity’ of usage in his essay on Burke and the French Revolution. ‘Political economy’ could for example be used for ‘either the emerging science of the ‘wealth of nations’ or the policy of administering the public revenue.’Footnote100 This was however prefaced by a remark that this was the way ‘political economy’ had been used at the time – which is true only for the last third of the century, and not before. The meaning of political economy that Pocock favoured was a more general one, never employed as such at the time: ‘a more complex, and more ideological, enterprise aimed at establishing the moral, political, cultural, and economic conditions of life in advancing commercial societies’. This, he thought, could also be described as a commercial humanism which met the challenge posed by civic humanism to the ‘quality of life in such societies’. It would have been better had he stuck with ‘commercial humanism’. This would clearly be a legitimate and convenient historical construct upon contemporary usage, whereas use of ‘political economy’ involves exactly the same kind of anachronism that has recruited eighteenth century writers on policy as the forerunners and anticipators of modern economic science, their work then being evaluated in its terms. Most of all, it was the construction in the early 1800s of a new doctrine of political economy that demolished the project of ‘commercial humanism’ to which Pocock alludes, creating an ambiguity in modern usage that conceals the radical break that it represented. To link Burke to ‘political economy’ in the sense generally understood today implies an endorsement of the very ‘theory’ that Burke and his peers rejected.

Richard Bourke’s recent monumental study of Burke’s politics has very little to say about any connection with political economy, being organised chronologically around his political career, chiefly conceived as a parliamentary life registered in speeches, letters and writings. Bourke’s discussion of the political and economic context in 1795 is quite brief, the connection made to Adam Smith retreating into the generalities of natural jurisprudence, rather than any examination of what Smith had to say about the circumstances and interests that governed markets.Footnote101 He does acknowledge Donald Winch’s discussion of the putative Burke-Smith relationship, although not its sceptical tone.Footnote102 Winch does what he can with Thoughts and Details, pointing to its deficiencies, while his examination of Burke’s supposed debt to Smith is likewise negative.Footnote103 This path is retraced by Ryan Walter,Footnote104 but identifying the construction and function of Smith’s analysis in Books I and II of Wealth of Nations: the nature of, and relationship between, productive and unproductive labour, and the central role of capital, its employment and supervision. It can then be demonstrated how little Burke’s own account of prices, wages and consumption owes to any arguments made by Adam Smith, that only a superficial similarity between Burke and Smith’s treatment of wage formation has licensed a reading of Burke as though he were a market theorist.Footnote105

In 1800 the posthumous publication of Thoughts and Details came with an editorial preface that not only explained its construction from two separate texts, but which emphasised that Burke had been a diligent student of ‘Agriculture, and the commerce connected with, and dependent upon it’, ‘one of the most considerable branches of political economy’. Hence the editor is placing Burke according to recent usage that has little connection with Smith, and none with political economy as ‘theory’. But as is evident from the contributions to Annals of Agriculture, many of whom could be described in the same terms, their response to high prices and pauperism were in the course of 1795 pragmatic and situational: they make little or no use of ‘principles’. Nor do they invoke any authorities, least of all Adam Smith. The practice of composing theoretical treatises on economic matters had not yet developed, so there were no authorities that could have been invoked. Smith’s own views on the grain trade, his opposition to export bounties, was itself founded upon his appreciation of the relatively stable conditions during the first half of the eighteenth century. There was little in Wealth of Nations that might provide worthwhile counsel for any policy regarding the turbulence of the 1790s.

For our purposes there is little need to discriminate between those parts of Thoughts and Details composed as counsel for William Pitt, and those drafted for correspondence with Arthur Young. We are interested in the kind of arguments Burke made regarding contemporary conditions, and while his counsel to Pitt would have taken account of Pitt’s position as Prime Minister, this did not modify the analysis upon which the counsel was based. We can briefly review the various propositions that he advances, checking their alignment with his contemporaries, and registering the source of any variation.

The first point concerns his conception of ‘the poor’. It is clear that for contributors to the Annals in 1795 ‘the poor’ were chiefly agricultural labourers on fixed wages that were inadequate for the purchase of sufficient amounts of their basic food, wheaten bread. Burke’s impassioned rejection of the ‘political canting language, “The Labouring Poor”’,Footnote106 simply marks his detachment from the contemporary view that agricultural wages were too low to properly support any family, and that the irregularities of seasonal labour exacerbated this problem. That ‘Patience, labour, sobriety, frugality, and religion’Footnote107 was appropriate advice to the poor was not a view widely shared in the pages of the Annals. No especially sophisticated analysis is needed to understand this. That the poor insisted on ‘bread made with the finest flour, and meat of the first quality’Footnote108 was proof of their recalcitrance as far as Burke was concerned. That the poor were better off in the 1790s than they had been ‘50 or 60 years ago’ is also a questionable observation.

As for wages, Burke maintains that ‘It is not true that the rate of wages has not encreased with the nominal price of provisions. I allow it has not fluctuated with that price, nor ought it … ’.Footnote109 As is evident from Section 2, given the rise in price through the summer of 1795, and the continuing rise after the harvest, this together amounted to several months of high prices, and so from the point of view of the labouring poor was more than a merely passing phenomenon. But Burke goes on from this to assert that ‘Labour is a commodity like every other, and rises or falls according to the demand. … They bear a full proportion to the result of their labour’.Footnote110 While this may appeal to a theorist, as recent research has shown many occupations, including agricultural labour, were characterised by wage rigidity; indeed, it was for this reason that the argument was advanced during 1795 that JPs should set agricultural wages, as in Whitbread’s December 1795 Bill.

The text then switches to a section taken from the draft letter to Young that articulates the assumptions in the foregoing about the wage relation, and the way in which wages were set.

There is an implied contract, much stronger than any instrument or article of agreement, between the labourer in any occupation and his employer – that the labour, so far as that labour is concerned, shall be sufficient to pay to the employer a profit on his capital, and a compensation for his risk: in a word, that the labour shall produce an advantage equal to the payment. Whatever is above that, is a direct tax; and if the amount of that tax be left to the will and pleasure of another, it is an arbitrary tax.Footnote111