Abstract

The #metoo movement prompted many librarians to self-disclose accounts of sexual harassment within their workplaces. In 2022, we used the validated Sexual Experiences Questionnaire to survey people who had recently worked in public libraries in order to measure the prevalence of sexual harassment within the field. A very high percentage of respondents stated they had experienced inappropriate behaviors from coworkers, patrons, and/or board of trustees. Nearly a quarter also shared qualitative comments which revealed a lack of psychological safety for those working in public libraries.

Introduction

In 2018, spurred by the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements, we surveyed academic librarians to assess the prevalence of sexual harassment in our field. The results, presented in 2019 at the ACRL National Conference and published in 2021 in College & Research Libraries, revealed that more than three-fourths of respondents had experienced sexual harassment from coworkers, patrons, or both.

We were not surprised by our findings; while there had been little formal research about sexual harassment in libraries, we were very familiar with more anecdotal evidence. An informal survey conducted by Manley in 1993 found that 78% of respondents experienced frequent sexual harassment, while another informal survey conducted in 2017 gathered numerous incidents of sexual harassment. What we did not expect from our survey, however, was the number of respondents who reached out to us individually. We had used an established instrument that collected solely quantitative data; there was no opportunity to provide comments. But our solicitation of their experiences led numerous librarians and library staff to email us directly to share their stories. When we publicly presented our research, we had similar experiences. People in the audience generally did not need our statistics to convince them that sexual harassment is prevalent in our field; many came to bear witness to the trauma they had either experienced or witnessed.

In response, when we ran the same survey for public librariansFootnote1, we added one feature: a comment box at the end. While not a required element of the survey, a quarter of respondents chose to write something in the box. Some were words of gratitude that we were amplifying this very real problem in librarianship, but many were personal narratives. The result, as one of our authors said, was “twenty-plus pages of tragedy.” We obviously had hit a very real nerve.

In this article, we will share the methodology, demographics, analysis, and results of our survey. We also will take this opportunity to explore how the well-established prevalence of sexual harassment in libraries affects psychological safety, and examine its normalization in the field.

Review of the literature

Sexual harassment in libraries

Until 2017, virtually all of the work related to sexual harassment in libraries was informal and reported in trade magazines, presentations, or on blogs (Jensen, Citation2013; Manley 1993; etc). Civitello and McLain’s presentation “It’s Not Just Part of the Job: Breaking the Silence on Sexual Harassment in the Library” at ALA Annual 2017 and Civitello’s follow-up article in that September’s Public Libraries were among the first to connect the #MeToo movement to libraries. Jensen conducted a survey of librarians in 2017 and shared the results on the blog Book Riot. The year 2021 saw the publication of three research studies on sexual harassment in libraries. In addition to our article, “#MeToo in the Academic Library: A Quantitative Measurement of the Prevalence of Sexual Harassment in Academic Libraries”, (Benjes-Small et al., Citation2021) College & Research Libraries published Barr-Walker et al.’s (Citation2021) “Sexual Harassment at University of California Libraries: Understanding the Experiences of Library Staff Members.” Lazaro-Rodriguez’s article, “Lethe and alethia: a study on cases of sexual harassment towards public library staff in Spain” was published in El Profesional de la informacion.

All of the articles discuss the difficulty in defining “sexual harassment.” Most people readily agree that rape, assault, and quid pro quo cases (“you’ll lose your job unless you do X”) fall into that category, but less extreme behaviors such as teasing, joking, and a touch of the hand or back are not as obviously labeled. The EEOC definition is more expansive than the public might realize:

It is unlawful to harass a person (an applicant or employee) because of that person’s sex. Harassment can include “sexual harassment” or unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical harassment of a sexual nature.

Harassment does not have to be of a sexual nature, however, and can include offensive remarks about a person’s sex. For example, it is illegal to harass a woman by making offensive comments about women in general.

Both victim and the harasser can be either a woman or a man, and the victim and harasser can be the same sex.

Although the law doesn’t prohibit simple teasing, offhand comments, or isolated incidents that are not very serious, harassment is illegal when it is so frequent or severe that it creates a hostile or offensive work environment or when it results in an adverse employment decision (such as the victim being fired or demoted).

The harasser can be the victim’s supervisor, a supervisor in another area, a coworker, or someone who is not an employee of the employer, such as a client or customer.

Researchers like Louise Fitzgerald have used a psychological framework to help identify what contributes to a “hostile or offensive work environment” and how the actions extract a toll on psychological health. Such work has called for a more nuanced look at what constitutes sexual harassment.

The scholarly articles used surveys which asked respondents to share whether they had experienced particular behaviors which have been identified as related to sexual harassment. Benjes-Small et al. relied on an existing scale used in previous research on sexual harassment, called the Sexual Experiences Questionnaire (SEQ). The SEQ was first developed by Louise Fitzgerald et al. and used in their 1988 paper, “The incidence and dimensions of sexual harassment in academia and the workplace.” Barr-Walker et al. referred to Fitzgerald’s work but also included behaviors suggested by feedback from librarian colleagues, and the Institutional Betrayal and Support Questionnaire version 1. Lazaro-Rodriguez used Barr-Walker’s instrument.

Overwhelmingly, the resulting scholarship supports the anecdotal evidence that sexual harassment is a serious problem in libraries. Barr-Walker et al.’s study focusing on the University of California Libraries system showed that 54% of respondents experienced and/or observed sexual harassment at work. In our study of United States academic libraries, 77% of respondents had experienced sexual harassment behaviors. Lazaro-Rodriguez’s survey was completed by 87 public librarians; all but two reported they had either personally experienced or observed sexual harassment of staff. Our study aims to add to the picture, assessing the prevalence and incidence of sexual harassment in United States public libraries.

Normalization of sexual harassment

Sexual harassment has been studied in numerous other professions and found to be particularly prevalent when predominantly female employees are seen to be in service to others, like social work, nursing, and waitressing. Good and Cooper (Citation2016) suggests that this is tied to more systemic issues; women are taught in our society to prioritize making others feel comfortable and carry that obligation into their work. They expend emotional labor to ensure that clients, patients, and customers feel cared about, and (especially male) recipients may misinterpret this attention as being personal in nature. According to Huebner (Citation2008), “Sex role spillover theory argues that sexual harassment is commonplace in women’s work because it replicates women’s traditional roles to serve and care for others” (p. 86).

When sexual harassment becomes common, the victims may accept it as normal. In Huebner’s study of nurses and waitresses, both dismissed unwanted sexualized interactions as expected parts of the job. As one interviewee said, “You know, it goes with the territory of being a waitress and being on that type of job. You shouldn’t have to think that way but that’s the way of society- and life goes on” (p. 80). In another interview, a nurse shared a time when a male patient masturbated in front of her and said she was not offended as she saw it as a sign of his fears about an upcoming surgery. As Huebner states, “Exposing himself and masturbating may be seen as sexual harassment in other workplaces but this nurse understood his behavior as part of care - as part of her job” (p. 82).

Even in fields not dominated by women, sexual harassment can be prevalent and normalized. Freedman-Weiss et al. (Citation2020)’s study of surgical residents, a field in which less than 30% of trainees are women, discovered that 70% of women and 30% of men had been sexually harassed during their surgical training. Over 90% of those who indicated they had been harassed said they had not reported it. The most common reasons for not doing so were that they thought it would be a waste of time (47.7%) and that they thought the harassment was harmless (62.1%). In this setting, most of the harassment was from supervisors or peers, but the idea that the inappropriate behaviors were “harmless” aligns with Huebner’s interviews with nurses.

Microaggressions and psychological safety in the workplace

Barr et al., Benjes-Small et al., and Lazaro-Rodriguez’s studies all found that most cases of sexual harassment are at the ‘lesser’ end of the scales, with the victim experiencing sex or gender related jokes and comments. These behaviors are types of microaggressions, defined as “everyday verbal, nonverbal, and environmental slights, snubs or insults, whether intentional or unintentional, which communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative messages to target persons based solely upon their marginalized group membership,” (Sue Citation2010). While often dismissed as being harmless or no big deal, such microaggressions can be chronic and have a cumulative effect, negatively impacting the work environment and individuals’ work. Gartner and Sterzing (Citation2016) review of the literature on microaggressions shows that victims can suffer from depression, anxiety, and lowered self-esteem. The chronic stressors can be especially prevalent and therefore harmful to people who have multiple marginalized identities.

As with sexual harassment, these microaggressions may become so common as to be normalized. But the literature shows that across professions, microaggressions are more allowed when the culprit is seen as a customer. Even if the victim feels like the behavior is harmful, their manager often dismisses their concerns. As Good says, “Even when employees do complain to their manager, employers may be reluctant to confront customers, given the status of customers as being almost as ‘second manager’ in the transaction” (p. 453). A common theme in the library literature similarly states that those in administration or supervisory positions are seen as indifferent or dismissive of patron misbehavior (Smith et al., Citation2020).

One consequence is that people feel less psychologically safe at their work. The idea of “psychological safety” grew out of research in organizational change (Schein and Bennis, Kahn), with Edmondson and Lei (Citation2014) defining it as “the shared belief held by members of team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking” (p. 350). In a psychologically safe workplace individuals believe they will not be rejected by colleagues for being themselves, and feel that others care about them and respect them. Workers who feel psychologically safe are more likely to speak up about workplace problems.

Research has identified key behaviors that promote psychological safety, including supportive leadership, access to mentorship, effective diversity practices, and rewarding interpersonal relationships with colleagues (Singh et al., Citation2013; Newman et al., Citation2017). Positive effects of having a psychologically safe workplace include increased production, performance, learning, and creativity (Newman). In their article, “Building a Culture of Strategic Risk-taking in a Science Library: Creating Psychological Safety and Embracing Failure,” Besara and Renaine (Citation2018) argue that innovation requires a willingness to fail, and that willingness comes from employees feeling psychologically safe.

Obviously, being harassed will make an employee feel less safe. But it’s worth unpacking the role a lack of psychological safety can play in the reporting of harassment. Tynan’s (Citation2005) research supports the hypothesis that workers who do not feel psychologically safe are less likely to communicate information upwards. Tynan argues that both interpersonal and structural factors affect the likelihood of employees reporting information which might reflect negatively on themselves or the organization.

Bergman et al. (Citation2002) article, “The (Un)reasonableness of Reporting: Antecedents and Consequences of Reporting Sexual Harassment” outlines the many negative repercussions often experienced by those who report sexual harassment, including retaliation, lowered job satisfaction, and greater psychological stress. Victims of sexual harassment naturally see what happens to others in their organization. If reporting is not taken seriously or the reporter is punished, then it is less likely that other victims will step forward. A dismissal of sexual harassment diminishes both the psychological safety of the workplace, and also lessens the chances of future reports. It is the responsibility of the organization, Bergman et al. argue, to build a climate that is intolerant to sexual harassment, “through a documented history of taking complaints seriously, protecting complainants from retaliation, and holding perpetrators responsible for their actions” (p. 241).

Methods and materials

With the academic library portion of our research complete we turned our focus to researching sexual harassment in public libraries. We were able to apply what we learned from the academic libraries survey to this version of the survey, adding a comment box for those who wanted to relate more information about their experiences.

The public libraries version of the survey focused on three research questions:

What is the prevalence of sexual harassment by coworkers among library workers in public libraries?

What is the prevalence of sexual harassment by board members/trustees among library workers in public libraries?

What is the prevalence of sexual harassment by library patrons among library workers in public libraries?

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was granted from our three universities. We learned a lot from our IRB application for our academic libraries survey and were able to apply that to this application. Once again, we did not capture the names of libraries or other identifying information. We also included a trigger warning along with resources such as the National Sexual Assault Telephone Hotline and contact information for RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network) in the event that the survey caused any negative effects.

We used the Sexual Experiences Questionnaire (SEQ), created in 1988 by Fitzgerald and Geltman and revised at different times in the 1990s and 2000s to better reflect the populations being studied. These revisions were necessary due to the fact that the definition of sexual harassment used is cis-gendered and sets cis-women as the victims. According to Johnson et al. (Citation2018), the SEQ is the “gold standard” for measuring prevalence of sexual harassment in the workplace. A copy of our survey is available at https://scholarworks.wm.edu/librariespubs/99/

The SEQ defines sexual harassment as “unwanted sex-related behavior at work that is appraised by the recipient as offensive, exceeding her resources, or threatening her well-being” (Fitzgerald et al., Citation1997). It asks participants to answer questions about the five dimensions of sexual harassment. The SEQ uses the following concepts to define the dimensions of sexual harassment (Fitzgerald et al., Citation1988):

Gender harassment is measured by seven items and defined as generalized sexist remarks and behavior.

Seductive behavior is measured by nine items and is defined as experiencing inappropriate and offensive, but essentially sanction-free sexual advances.

Sexual bribery is measured by four items and defined as solicitation of sexual activity or other sex-linked behavior by the promise of rewards.

Sexual coercion is measured by four items and is defined as coercion of sexual behavior by threat of punishment.

Sexual assault is measured by five items and is defined as gross sexual imposition or assault.

The level of sexual harassment measured by the SEQ through these dimensions increases in severity from general sexist remarks to gross sexual assault. The respondent answers questions about the various dimensions of sexual harassment and must say whether or not they have had the experience described. The final question of the survey is designed to serve as a global indicator of Sexual Harassment. It asks if the participant has ever been sexually harassed. The final question is designed to see if participants consider the behaviors described through these dimensions as sexual harassment. The phrase sexual harassment is not used until this final question because we wanted the survey to focus on the behaviors experienced and not “sexual harassment.”

Participants were asked to report on experiences in the past five years in order to estimate the prevalence of sexual harassment of the population. When measuring prevalence, it is best practice to limit the time period which the respondents are asked about. As Johnson et al. (Citation2018) states, “[A]fter long enough periods, memory deterioration sets in, leaving behind only those sexual harassment experiences that left a lasting memory, and leaving out everyday sexist comments or ambient harassment.”

The survey was sent out to numerous organizations for distribution on their list-servs, including Urban Librarians Unite, the Ohio Library Council, the Pennsylvania Library Association, the Texas Library Association, the Maryland Library Association, the New Jersey Library Association, the Illinois Library Association, the Washington Library Association, the Virginia Library Association, and the AUTOCAT listserv. The survey was also promoted on Facebook, Twitter, and ALA Connect. The survey invitations requested that participants only report on experiences in public libraries. It also stated that they should fill out the survey even if they had not experienced sexual harassment.

The survey ran for 27 days from February 1, 2022, to February 27, 2022. During that time 462 individuals provided partial or complete responses to the survey. The survey begins with a screening question designed to allow participants to opt out of the survey if they would like to. Of the 462 individuals who began the survey, 461 agreed to complete the survey. A total of 337 participants completed the survey for a response rate of 72.9%. the remaining 37.1% of participants only provided partial response. This gave us a total of 678 employment experiences.

Demographics of survey participants

Data was collected on participants age, race, gender, and employment by the survey. We used guidelines suggested by The Williams Institute to identify transgender individuals. These guidelines recommend asking about gender with two questions.Footnote2 The first question asks about the gender assigned at birth, and the second question asks about participants current gender identity. Over 95% of participants were cisgendered (84.2% cis-women and 10.9% cis-men). Transgendered or non-binary individuals made up 4.8% of participants. The survey measured race with one question that asked participants to self-identify their race as: White, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, or Other. Participants could select more than one choice to indicate a multiracial identity. The majority of participants (91.6%) indicated they were white alone (not in combination with any other race). The rest of participants (8.4%) indicated they were either a racial minority, biracial, or multiracial. Age was self-reported in years. The age range of participants was 19–75 with an average age of 40.71. Half of respondents were between 19 and 37 and the other half were between 38 and 75 ().

Table 1. Participant demographics.

These demographics generally align with the overall librarian profession, with the 2022 Bureau of Labor Statistics showing that 86% of employed librarians identify as white and 82% as women.

The survey also collected information about the participant’s employment experiences and about the characteristics of the libraries in which they worked. Library employment experiences refer to the number of library jobs held by participants. A total of 678 job experiences were reported from this survey. The number of library jobs per participant ranged from 1-6, with an average of approximately 1.5 library jobs per participant. Those with more than one position (N = 147) provided 436 observations or library job experiences ().

Table 2. Total library job experiences (678 total experiences recorded).

Participants were asked what percentage of each job was spent with patrons, ranging from 0–100%; the results showed an average of 58.08% (SD = 28.82). Nearly half (51.8%) of participants reported working in an urban or suburban library setting, and 26.4% of participants reported working in a town or rural setting (). Population served was record for participants with the largest number of participants working in settings with a population of 25,000 to 249,999. The breakdown of the population served can be seen in .

Table 3. Library jobs spent in patron facing roles based on setting.

Table 4. Population served.

Quantitative responses

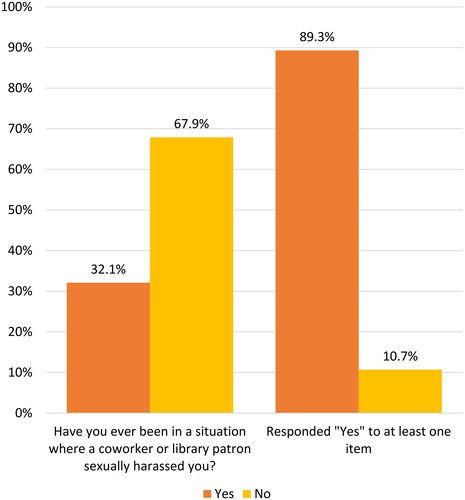

Of the 461 respondents, 89.3% had experienced one of the behaviors in the survey. Survey participants were asked to respond separately for different jobs that they held during the 5 year period of analysis. Thus, if one participant had two different jobs, that person would answer questions about harassment at each job separately. All percentages below reflect the percentage of responses we received to any individual question for each job as reported by the participants, rather than each participant.

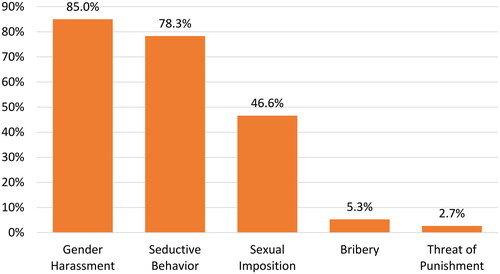

Consistent with finding among academic librarians, gender harassment was the most common dimension of sexual harassment experienced by public librarians, with 85% of library experiences including some form of gender harassment. Only slightly less common was seductive behavior, occurring in 78.3% of responses. Again, consistent with academic librarians, sexual imposition occurred in 46.6% of responses. Bribery (coercion) and threat of punishment were uncommon, at 5.3% and 2.7% respectively, but we would like to underscore that these last two categories of harassment are very severe and destructive to the victims, and while those percentages are small, they represent a combined 45 instances of experiences that are likely to have been quite traumatic ().

Who are the harassers?

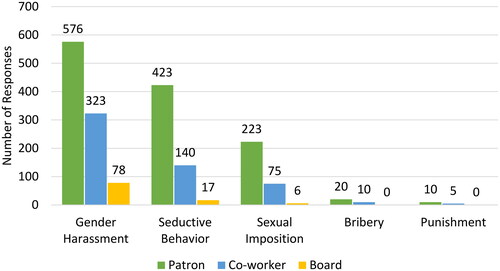

This survey asked about three potential identities of harassers: coworkers, patrons, and board members. In the previous survey academic librarians reported that much of the harassment they experienced came from patrons (799 instances in the two most common categories, but almost half of it came from colleagues (770 instances in the two most common categories). While public librarians experience significant harassment from their coworkers, a striking difference in this data is that the majority of harassment directed at public librarians comes from patrons. Board members account for some of the harassment, primarily in the form of gender harassment.

There are many potential reasons that patrons represent such a large percentage of harassers for public librarians. One potential explanation is that such a large percentage of public librarians are either women or trans/non-binary (89% of survey respondents), a group that consistently represents the vast majority of harassment targets in studies measuring sexual harassment. Evidence also shows that people who are anonymous to their targets are more likely to harass, and public library patrons are likely to be even more anonymous in public libraries than in academic libraries. Since people who feel themselves in a powerful position are also more likely to harass, it is possible that the service-oriented nature of public libraries also contribute to high levels of patron harassment, though this service-orientation is probably not meaningfully different in public and academic libraries. A final potential contributing factor is the amount of time that public librarians spend in public-facing role. The mean percentage of time spent in public facing work from our survey respondents was 58%, with the highest percentages of public facing work reported in small towns (69% in towns of less than 1,000, and 76% in towns between 1,000 and 2,499) ().

Gender harassment

Given that 85% of responses reported some form of gender harassment, it’s not surprising that high percentages of responses report having experiences each of the individual categories of gender harassment. The most frequent experiences are “staring, leering, or ogling you in a way that made you feel uncomfortable” (65.7%) and “frequently treated you ‘differently’ because of your gender (i.e., ever been either favored, slighted, or ignored)” (65.5%).

Seductive behavior

The second-most common form of harassment was seductive behavior, with 78.3% of responses reporting it. The category was largely dominated by one particular experience: “you received unwanted attention from a co-worker, board member/trustee, or library patron?” (69.6%), and is supported by the qualitative data, which report numerous experiences of patrons attempting to start romantic relationships in some way. A distant second, with 54%, is the similar item “unwanted attempts to draw you into a discussion of personal matters (e.g., attempted to discuss or comment on your sex life).”

Sexual imposition

The third most common form of harassment is sexual imposition, reported by 46.6% of responses. The majority of responses in this category refer to “deliberately touched you (e.g., laid their hand on your bare arm, or put an arm on your shoulders) in a way that made you feel uncomfortable” (46%), which accounts for the least severe level of this category. It is important to note that this category also includes some very disturbing levels of sexual assault which, while small, are extremely distressing for their victims, including “forceful attempts to touch, fondle, kiss, or grab you” (4.3% − 24 instances) and 7 instances of attempted rape or “unwanted attempts to have sexual intercourse with you that resulted in you crying, pleading, or physically struggling” (1.3%).

Bribery or threat of punishment

The two least common categories of sexual harassment are bribery and threat of punishment. The majority of the bribery category reported was “subtly bribed with some sort of reward (e.g., preferential treatment) to engage in sexual behavior with a coworker, board member/trustee, or library patron” (4.4% − 25 instances). The most commonly reported category of threat of punishment was “you actually experienced negative consequences for refusing to engage in sexual activity with a co-worker, board member/trustee, or library patron” (2.5% − 14 instances).

A striking contrast exists in the data between the number of responses that report having been sexually harassed, compared to the number of responses that report at least one category of sexual harassment. When directly asked whether they had been sexually harassed at the end of the survey, only 32.1% of respondents said yes, and yet, 89.3% of totally library experiences included at least one sexual harassment experience. This speaks to the widespread normalization and minimization of harassment of public librarians. This contrast was also seen among academic librarians, 77.4% of whom responded “yes” to at least one dimension of sexual harassment, and only 17% of whom responded yes when asked if they had been harassed ().

Non-cis harassment experiences

While only 4.8% of respondents identified as transgender or non-binary, the experiences of this subgroup of library professionals bears particular attention, given that this group is much more likely to be targeted by various kinds of harassment (Brassel et al., Citation2019).

One should interpret the data related to non-cis respondents with care. We conducted chi-square tests of independence for each dimension of harassment looking only at the non-cis respondents. Importantly with the small number of non-cis individuals in the sample, it is difficult to be confident in the statistical test.

Several dimensions of harassment do not show a statistically significant difference in the harassment experiences of non-cis respondents compared to those of the overall sample. Gender harassment, sexual imposition, bribery, and punishment all show a statistically insignificant difference for non-cis respondents.

There is one dimension that shows a statistically significant difference in the harassment experiences of non-cis respondents: seductive behavior. In this category, 93.3% of non-cis respondents report harassment experiences, compared to 77.4% of cis-gender individuals.

Interestingly, there is also a statistically significant difference in the number of non-cis respondents who reported “yes” to the question of whether they had been harassed: 50% of non-cis respondents answered yes to this question, compared to 31.1% of cis-gender respondents. This might suggest that non-cis library workers are more often harassed (and the evidence suggest that at least in one category, they are), but this number seems to indirectly measure whether or not people know what behavior is harassment, and this finding suggests that non-cis respondents are more aware that the behavior they are experiencing constitutes sexual harassment.

We want to emphasize again that the small sample makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions, but the experience of non-cis respondents seemed important, and worth addressing separately. This research suggests that in some dimensions of harassment, non-cis respondents were more likely to experience sexual harassment in their library workplaces, and that they are more likely to recognize those experiences as harassment.

Qualitative responses

Of the 461 survey responses, we received 113 (24%) substantive qualitative comments to the final question on the survey: “If you would like to share anything else about your experience(s) with sexual harassment in public library settings, please use the space below to include that information.” Many of these comments summarized horrifying stories of workplace harassment that respondents tolerated for years. Added together the comments make for a tragic record of experiences for the survey respondents. Some of the comments indicated that the described harassment happened before the 5-year window of data collection for the survey, indicating that some of the qualitatively-described specific experiences are in addition to those reflected in the survey data.

Themes

Several themes emerged from the qualitative comments:

Administrative response

Persistence/inescapability of harassment

Disengagement

Power imbalances

Values conflict

Fear

Normalization

Bearing witness

We describe these themes below, and include illustrative comments for each.

Administrative response

One particularly dispiriting theme of the comments was the inability, or unwillingness, of library administrators to address sexual harassment. All U.S. workplaces, including libraries, are legally obligated to protect their employees from harassment, both from colleagues and from patrons. The comments suggest that some administrators are unaware of this obligation, or do not recognize harassment for what it is. Existing research clearly indicates that lack of response from management contributes to the harm caused by sexual harassment both to the targets, and to their workplaces (Bergman, Langhout, Palmieri, Cortina, and Fitzgeral). At least 20 comments (17% of comments submitted) were related specifically to this theme.

“The HR response to my concerns was ‘why don’t you just leave then’ and ‘you don’t know how to pick your battles.’”

“Management and leaders were dismissive if concerns were ever brought up to them, often telling the staff member who experienced sexual harassment that they need to have thicker skin or learn to deal with it or that they should know better to avoid putting themselves in that situation.”

“Even the library’s lawyer on various occasions told me some variation of ‘it’s not that big of a deal’ or ‘just ignore it.’”

“This same patron stared at my young intern one year so frequently and creepily, she cried. Our security guard laughed at her distress and refused to do anything.”

Even when management takes the situation seriously and intervenes, a common theme was the inability of management to stop the harassment.

“If patrons find out I have a wife, they sometimes react poorly and loudly… and I once had a patron scream at the top of his lungs, ‘No, don’t be a homosexual’ while I was working a public desk. Our management doesn’t stand for this, but it’s still so very, very tiring to deal with on a daily basis.” [emphasis added]

“Often the only course of action is to write up a report… If the patron is still in the library, the Director will ask them to leave. But overall, I feel helpless in these situations.”

“My library was great with dealing with this. The moment the patron walked in, I disappeared into a back office to do work. This patron eventually began to stop approaching me.”

These quotes demonstrate that even when management intervenes, sometimes the best available outcome is that the harasser eventually just gives up, leaving all the agency over whether the harassment ends with the harasser, instead of the target.

Negative cases of administrative or institutional support are common in the literature. A majority of Lazlo-Rodriguez’s survey respondents said their institutions failed to: create an environment in which it was safe to talk about the issue of sexual harassment; believe the victim; apologize for what happened; create an environment that even admitted sexual harassment was a problem. Barr-Walker et al.’s repondents had similar experiences. In a notably named section “Institutional Betrayal and Importance of of Addressing Sexual Harassment” a majority disagreed that addressing sexual harassment was very important to the UC library administration, and a sizable minority of those who reported sexual harassment felt “unsupported, betrayed, or discriminated against during this process” (p. 247).

Persistence

Many comments described harassment as something inescapable, inevitable, or frequent. One particularly strong signal was harassment over the phone. Sixteen comments − 14% of the qualitative responses, described the exact same behavior: “Most frequently it is over the phone, and involves a patron masturbating when you try to help them.”

Many comments described numerous occasions of being asked out, given unwanted gifts, followed to their cars, comments of sexual innuendo, asked for their numbers, etc. Some comments described assault. These comments usually explained that the harassment would be repeated, from the same patron, and the target was expected to solve it.

“A patron who hangs around outside my office for however long it takes for me to come out, then follows me to my car. A patron who writes me poetry about how he can’t sleep because he’s thinking of me.”

“A patron pinned me against the wall while inside an elevator with him, with his erect penis up against my backside. Another patron took photos of me without my knowledge and posted them on his blog along with poetry he had written about me.”

“In a year, he made about a dozen unwanted or uncomfortable comments and asked me out twice.”

“And I mean, my breasts were grabbed, my clothing investigated, rude things said, etc.”

“A younger page was told to ‘just stop walking to your car alone’ after a repeat offender followed her around the library (and outside).”

“I pointed out a new bulletin board I just designed (titled “Cozy Nights”) to a patron who was there with his 7-8 y/o son and he responded ‘Mmmm cozy nights, your place or mine?’”

Disengagement

Several comments address deliberate disengagement from work as a protection mechanism from harassment.

“I am helpful but less open and friendly to middle-aged to older men to dissuade unwanted attention.”

“My branch manager at the time instructed the younger female staff to try and be ‘less friendly’ with the primary offender. As someone trained in her former profession to assist sexual assault victims, I was blown away by such a careless response.”

“The majority of my harassment experience seems to be male patrons assuming my friendly, customer service oriented demeanor is because of genuine sexual interest in them and not a job for which I am paid.”

“It’s humiliating. To have instances where I thought I was having a friendly conversation about library services suddenly turn into asking me on a date is startling.”

“I do tend to stay behind the desk when I am alone in the library with a questionable male patron as it feels safer but have used a cart to block people when needed as well.”

“Getting unwanted overtures from a patron is based more on how nice you are to them than how old you are and definitely has nothing to do with revealing clothes, makeup or other ‘sexualized’ outward appearances.”

The second quotation above underscores that expecting the victims of harassment to manage their own harassment through dissuasion is, while a commonly used tactic, wholly inappropriate and insufficient.

Power imbalances

Responses frequently mentioned the way that power imbalances contributed to the frequency or harm of their harassment experiences. This is consistent with sexual harassment literature that finds individuals who feel themselves to be in a position of power over their targets are more likely to harass.

“Board members seem to think they are not accountable to workplace sexual harassment laws since they are not employees.”

“It’s very common for patrons to feel they have some kind of ‘power’ over staff and to try to intimidate staff via sexually suggestive language and acts.”

“Library patrons sometimes feel entitled to invade the personal space and privacy of public library employees–occasionally with an invocation of ‘salaries paid by taxpayers’ that justifies, for some, their mistreatment of library employees.”

“Female patrons NEVER tell me to smile. Not once. Only male patrons do.”

“I've been called a 'bitch’ by male patrons, told to ‘suck [their] dick,’ and threatened with violence.”

Values conflict

Respondents shared stories of prioritizing the needs or feelings of the patron over the safety of the staff as a reason cited for not intervening to protect the targets of harassment.

“She went on to say that I should not contact the patron and/or discuss the incident, because we ‘wouldn’t want to make him feel like we think he is a pervert.’”

“There is more concern for patrons than there is for employees.”

“Sexist remarks are most often made by patrons who clearly have some kind of mental health need. This adds a layer of complexity to shutting down the harassment while offering empathy to an underserved group.”

“One guy… I didn’t know how to discourage because he was passively suicidal.”

“My manager thought it was ‘good to have a pretty face at the front desk.’ So myself and other female librarians were given the majority of the shifts.”

“I was met with comments like ‘Oh, but you are so good at the front desk’ and ‘But patrons really like you’ and felt guilted into remaining on the desk.”

Fear

Qualitative data included many stories about librarians feeling fear for their physical safety. This very basic need going unmet in the workplace can cause substantial psychological harm, particularly in situations where the target is not empowered to protect herself.

“My family would like me to have something such as mace for safety it is not allowed by my library district.”

“Usually the library was otherwise empty except for the patron/s in question and if not for the giant (floor to ceiling) window behind the front desk facing a usually populated main street I would have felt even more isolated and afraid.”

“I have been exposed to child pornography more than once which was extremely traumatic.”

“I ended up walking around with the library’s panic button until he left.”

Normalization

Comments suggested widespread normalization of harassment, often in ways that the commenter did not appear to recognize. The perspective of “this is just how it is” or “this isn’t really harassment” were common.

“I had a stalker for months. I was told by my director that I was overreacting due to lack of experience and needed to calm down.” [emphasis added]

“I don’t know that I would’ve even categorized those experiences as sexual harassment because they are so normal.”

“What other women might call ‘harassment’ to me is simply the verbal wanderings of a man in his older age.”

“It’s difficult to judge when patron behavior crosses the line unless it’s an extreme case.”

“This is sadly a normal part of life as someone in a public service role, especially in a place like a library.”

“It is an everyday occurrence when working with library patrons.”

“These sorts of remarks and behaviors do not happen often… This probably happens once every 2–3 months.”

The final comment in particular highlights that the respondent in that case considers continual, regular, blatant harassment that is happening 4-6 times every year, as infrequent.

Bearing witness

Many of the respondents who offered comments used those comments to report on harassment they had witnessed, but not personally experienced, and so did not include in the survey. Literature on workplace bullying shows clearly that witnessing harassment extends the harm to both the target and to the witness. To not be the victim of harassment does not exempt one from the harm caused by it.

“My coworker was sexually assaulted and he got away with it. She has to see and speak with him, fortunately he is at another location.”

“I witnessed a lot of these kinds of behaviors happening to a different coworker, to the point where she made a March Madness style bracket of patrons who would frequently make unwanted advances towards her.”

“I know of another coworker that experienced harassment from only one patron, but it happened in such a harmful manner that I feel it 'counts’ more.”

“We usually are not treated as badly. I believe this is because we are older.”

“Many of my coworkers have not been so unscathed.”

“I have witnessed experiences that were not directed at me, but at my coworkers.”

“As I get older, I find I get much less actual attention from random men in the library, which is nice for me, but I know the younger workers, mostly female, still deal with unwanted attention on a semi-regular basis.”

“I had a dozen patrons make unwanted comments or romantic advances in a year, but a coworker at another library experienced twice that, so it feels hard to judge.”

“I have experienced very little unwanted harassment in the past 5 years, my young coworkers are often targeted.”

Limitations

Over the years, the SEQ has been modified several times to reflect various populations, which has caused some to question its validity (Gutek et al., Citation2004). The SEQ is also focused on interpersonal, face-to-face encounters and does not include behavioral online examples, such as being harassed through social media or reference chat. While other library studies have used homegrown surveys, our field would benefit from a tool which includes online behavior and has passed a rigorous validation process.

Although our respondent demographics in terms of race and gender are an accurate reflection of the overall profession, we must always be cautious about generalizing from self-selected Internet surveys. It is feasible that our survey has a disproportionate number of library workers who have experienced or witnessed sexual harassment; on the other hand, it is possible that this same population may have avoided responding to such a survey because the topic is emotionally fraught or traumatic, an effect known as nonrespondent bias. While some suggest that to encourage response rates sexual harassment researchers should frame their surveys as being about “culture” and not use the phrases “sexual harassment” or “sexual misconduct” in their solicitation (Johnson et al., Citation2018), our three Institutional Review Boards required that we warn respondents about the content before they started the survey. Our research team agreed with this approach, but we recognize the possible critique.

Discussion

In this study, we studied the prevalence of sexual harassment experienced by people who work in public libraries. We found that a staggering 89.3% of respondents had experienced at least one of the behaviors in the survey within the past 5 years. These experiences were found in all settings and sizes of libraries: rural, suburban, and urban; and of all population sizes. Numerous librarians expressed to us in the comments and off-survey that if they had been able to report on their entire time in public libraries, not just the past five years, they would have had many more examples to share. Anecdotally, we suspected sexual harassment was endemic in public libraries, but the true breadth and depth of harassment is even more alarming.

At the same time, what exactly constitutes sexual harassment continues to be debatable. While the great majority of respondents indicated they had experienced one of the behaviors in the SEQ, only 34% said they had experienced sexual harassment. This is strikingly similar to our study in academic libraries, where 77% of respondents had experienced an SEQ behavior, but less than 20% said they had ever been sexually harassed. This disconnect has some worrisome ramifications. If we don’t expressly agree on the parameters of the problem, how can we develop appropriate solutions?

One challenge to a consensus about sexual harassment is our society’s normalization of inappropriate behaviors. In our researcher group, the librarians have been told to “let it go” and “not make a fuss” when subjected to behaviors listed in the SEQ. The comments in our study show just how much sexual harassment has been normalized in our field. At least 20 respondents reported that library administration was unable or unwilling to address sexual harassment by patrons, and others felt that even colleagues dismissed their experiences. This normalization affects the psychological safety of employees, making them fearful in their jobs and also reducing their inclination to report sexual harassment.

Conclusion

Workplaces are legally and ethically required to protect their staff from sexual harassment from both inside and outside the library. For years librarians have talked amongst themselves about the behaviors they have been forced to endure in their jobs; our research shows that such problems are widespread. Administrators and managers need to consider how to make their libraries safer.

Fundamentally, the organizational culture must also be changed. If a workplace is thought to be unsupportive about reported harassment, does not sanction offenders, and appears to punish whistle blowers, it is likely to have a higher level of sexual harassment (Willness et al., Citation2007). As damaging as sexual harassment is to its victims, we must also consider the ripple effect Hulin et al. (Citation1996) found that workplaces that were permissive of sexual harassment had a “chilling effect” on all women in the organization, negatively affecting their job satisfaction, psychological well-being, and physical health (p. 146). It is essential that libraries intentionally plan to prevent sexual harassment, protect their workers, and hold harassers accountable.

In previous presentations of our work, we have often been asked for model policies or statements that libraries can implement. So far, we have not found any resources to point audience members toward. We strongly urge the American Library Association to address this absence, creating and promoting guidelines for the development of policies and procedures. ALA’s Policy Checklist for User Behavior and Library Use, Guidelines for Reopening Libraries during the Covid-19 Pandemic, and How to Respond to Challenges and Concerns about Library Resources are examples of similar efforts in recent times. Sexual harassment is a profession-wide problem, and we need as a profession to address it.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 For this study, we are using the word “librarians” to refer to anyone who worked in a library.

2 The GenIUSS Group, “Best Practices for Asking Questions to Identify Transgender and Other Gender Minority Respondents on Population-Based Surveys” (The Williams Institute, Citation2014), accessed January 28, 2019, https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/geniuss-report-sep-2014.pdf.

References

- Barr-Walker, J., Hoffner, C., McMunn-Tetangco, E., & Mody, N. (2021). Sexual harassment at University of California libraries: Understanding the experiences of library staff members. College & Research Libraries, 82(2), 237. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.82.2.237

- Benjes-Small, C., Knievel, J., Resor-Whicker, J., Wisecup, A., & Hunter, J. (2021). #MeToo in the academic library: A quantitative measurement of the prevalence of sexual harassment in academic libraries. College & Research Libraries, 82(5), 623. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.82.5.623

- Bergman, M. E., Langhout, R. D., Palmieri, P. A., Cortina, L. M., & Fitzgerald, L. F. (2002). The (un)reasonableness of reporting: Antecedents and consequences of reporting sexual harassment. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(2), 230–242. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.2.230

- Besara, R., & Renaine, J. (2018). Building a culture of strategic risk-taking in a science library: Creating psychological safety and embracing failure. Journal of New Librarianship, 3(1), 48–52. https://doi.org/10.21173/newlibs/4/10

- Brassel, S. T., Settles, I. H., & Buchanan, N. T. (2019). Lay (Mis)perceptions of sexual harassment toward transgender, lesbian, and gay employees. Sex Roles, 80(1–2), 76–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0914-8

- Edmondson, A. C., & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091305

- Fitzgerald, L. F., Drasgow, F., Hulin, C. L., Gelfand, M. J., & Magley, V. J. (1997). Antecedents and consequences of sexual harassment in organizations: A test of an integrated model. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(4), 578–589. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.82.4.578

- Fitzgerald, L. F., Shullman, S. L., Bailey, N., Richards, M., Swecker, J., Gold, Y., Ormerod, M., & Weitzman, L. (1988). The incidence and dimensions of sexual harassment in academia and the workplace. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 32(2), 152–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(88)90012-7

- Freedman-Weiss, M. R., Chiu, A. S., Heller, D. R., Cutler, A. S., Longo, W. E., Ahuja, N., & Yoo, P. S. (2020). Understanding the barriers to reporting sexual harassment in surgical training. Annals of Surgery, 271(4), 608–613. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003295

- Gartner, R. E., & Sterzing, P. R. (2016). Gender microaggressions as a gateway to sexual harassment and sexual assault: Expanding the conceptualization of youth sexual violence. Affilia, 31(4), 491–503. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109916654732

- Good, L., & Cooper, R. (2016). But it’s your job to be friendly’: Employees coping with and contesting sexual harassment from customers in the service sector. Gender, Work & Organization, 23(5), 447–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12117

- Gutek, B. A., Murphy, R. O., & Douma, B. (2004). A review and critique of the sexual experiences questionnaire (SEQ). Law and Human Behavior, 28(4), 457–482. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:LAHU.0000039335.96042.26

- Huebner, L. C. (2008). It is part of the job: waitresses and nurses define sexual harassment. Sociological Viewpoints, 24(10), 75–90.

- Hulin, C. L., Fitzgerald, L. F., & Drasgow, F. (1996). Sexual harassment in the workplace: Perspectives, frontiers, and response strategies. In Sexual harassment in the workplace: Perspectives, frontiers, and response strategies (pp. 127–150). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483327280

- Jensen, K. (2017). The state of sexual harassment in the library. Book Riot. https://bookriot.com/sexual-harassment-library/

- Jensen, K. (2013). Things they don’t teach you in library school: Sexual harassment? Yes, it can happen in the library. Teen Librarian Toolbox. https://teenlibrariantoolbox.com/2013/03/24/things-they-dont-teach-you-in-library-school-sexual-harassment-yes-it-can-happen-in-the-library/

- Johnson, P. A., Widnall, S. E., & Benya, F. F. (Eds.). (2018). Sexual harassment of women: Climate, culture, and consequences in academic sciences, engineering, and medicine. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24994

- Lázaro-Rodríguez, P. (2021). Lethe and aletheia: A study on cases of sexual harassment towards public library staff in Spain. El Profesional de la Información, 30(3), e300319. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2021.may.19

- Newman, A., Donohue, R., & Eva, N. (2017). Psychological safety: A systematic review of the literature. Human Resource Management Review, 27(3), 521–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.01.001

- Singh, B., Winkel, D. E., & Selvarajan, T. T. (2013). Managing diversity at work: Does psychological safety hold the key to racial differences in employee performance? Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86(2), 242–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12015

- Smith, D. L., Bazalar, B., & Wheeler, M. (2020). Public librarian job stressors and burnout predictors. Journal of Library Administration, 60(4), 412–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2020.1733347

- Sue, D. W. (2010). Microaggressions in everyday life: Race, gender, and sexual orientation. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Sue, D. W. (2010). Microaggressions: More than just race | psychology today. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/microaggressions-in-everyday-life/201011/microaggressions-more-just-race

- The Williams Institute. (2014). Best practices for asking questions to identify transgender and other gender minority respondents on population-based surveys. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/geniuss-report-sep-2014.pdf

- thisisloyal.com, L. | (n.d.). Best practices for asking questions to identify transgender and other gender minority respondents on population-based surveys (GenIUSS). Williams Institute. Retrieved September 18, 2023, from https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/geniuss-trans-pop-based-survey/

- Tynan, R. (2005). The effects of threat sensitivity and face giving on dyadic psychological safety and upward communication. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 35(2), 223–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2005.tb02119.x

- Willness, C. R., Steel, P., & Lee, K. (2007). A meta-analysis of the antecedents and consequences of workplace sexual harassment. Personnel Psychology, 60(1), 127–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00067.x