Abstract

While it’s well known that behavior is the target of systems of online surveillance, explanations of what behavior actually is are much harder to come by. This article provides a brief account of behavior’s twentieth century appearance and journey to a position of centrality in common-sense understandings of who we are. Given that traditional understandings of the right to privacy and self-determination are founded on a liberal humanist understanding of the subject, dominant critiques of online surveillance are seriously compromised by the fact that behavior cannot, strictly speaking, be accommodated within this intellectual framework.

Introduction

While there is plenty of anxiety concerning surveillance and invasion of privacy by online platforms such as Google and Facebook, it’s often unclear what specific objections this anxiety results from. In public debates, there is a tendency to invoke a traditional Enlightenment principle that privacy is a personal right, and surveillance an infringement on that right. However, the processes by which online platforms gather data about people are different in important ways from how law enforcement, for example, might surveil a person, or how a peeping Tom might watch someone through a window. It’s not entirely clear how Enlightenment conceptions of personal privacy, or even traditional definitions of surveillance itself, can be mapped onto this newer regime given that it doesn’t entail direct scrutiny of a person or require a human agent of surveillance.

Attempts to understand the distinctive character of online surveillance often fix on a difference in its object. That is, while it is clearly scrutinizing you, the “you” being scrutinized doesn’t seem to fit a definition of the liberal subject whom traditional notions of privacy are intended to protect. “Data doubles” (Nichols Citation2004), “data shadows” (Clarke Citation1994), “algorithmic identities” (Cheney-Lippold Citation2011), “voodoo dolls” (ABC Citation2019), or some other term might be used to suggest a kind of ghost or substitute that constitutes the target of algorithmic analysis more properly than the entity we generally – informed by humanist ideas about individual identity – understand to be ourselves. This other entity is clearly connected to us, but for some reason it doesn’t seem to fit an inherited sense of what truly and essentially constitutes us. A sense that the object of online surveillance isn’t quite us, or only encompasses a part of us peripheral to the core, definitional components of identity, seems to underly the ambivalence often displayed about online tracking and profiling, where most people seem to object to it in principle but feel comfortable with it in practice.

The lack of clarity concerning the relationship between personal identity and online surveillance results from the fact that systems of online profiling are founded on an understanding very different from that supporting a traditional conception of the self (cf. Yeung Citation2017). While terms like “data doubles” seek to negotiate this problem by positing another form of personal identity that fits online profiling where older forms of identity do not, the real problem is that identity is not the object of online surveillance at all. While our self-conception is still dominantly informed by the Enlightenment-era, autonomous, internalized subject, systems of online surveillance understand us using the twentieth century concept of behavior, which is not only irreconcilable with the liberal humanist subject, but is in fact antithetical to it.

This problem is clearly illustrated by Shoshana Zuboff’s book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (2019), one of the most influential critiques of online surveillance. Zuboff explicitly characterizes online behavioral surveillance as a continuation – or rather reanimation – of a twentieth century American behaviorist project and critiques it from a liberal humanist position. However, if we join Zuboff in subscribing to a liberal humanist view of the individual as a rational, self-determining agent, we should also dismiss behaviorism as a pseudo-scientific endeavor that misattributes the originators of human action and is therefore doomed to failure. And if we do this, then, while online behavioral profiling might be a problem for online platforms and their advertising customers due to its ineffectiveness, it’s not clear why it should be a concern for anyone else.

In an effort to advance the understanding of online surveillance, and particularly the advertising market that drives its mass-scale private-sector deployment, this article will give an account of the origins of behavior as a concept, explain how it has come to be a key part of the online economy, and make some suggestions concerning what this tells us about the nature of online profiling. My intention is not to contribute to – or even engage with – the science of behavior in which the term originates; rather, I take behavior as a culturally and historically specific concept, the understanding and application of which has been inflected by different social and intellectual contexts leading up to it taking a central position in both popular and technical understandings of online surveillance. The question of behavior’s objective reality, and its efficacy or otherwise for describing, predicting, or modifying human or animal activity, falls outside the scope of this article, and the answer to these questions does not affect its argument. Obviously, whether behavioral research can be used to change how people act is highly consequential for the matter of how concerned we should be about online behavioral profiling; however, it is precisely because of this that critiques of behavioral profiling need to move away from invoking a liberal humanist understanding that suggests such external influence is not possible.

The value of data

The wealth of big online platforms is often explained in terms of an “attention economy,” but this is misleading; when Michael Goldhaber coined the term attention economy in the 1990s, central to it was the principle that attention has no financial worth (Goldhaber Citation1997). While the rise of social media influencers might have confirmed his prediction that online interaction would produce an economy built around the ability to hold attention, his larger claim that this attention economy would be separate from, and could even replace, the financial economy greatly underestimated capitalism’s adaptability.

Goldhaber’s argument that online interaction would replace money with a currency of attention rested on a belief that information – or data – could never hold significant monetary value:

Information … would be an impossible basis for an economy, for one simple reason: economies are governed by what is scarce, and information, especially on the Net, is not only abundant, but overflowing … It is not in any way scarce, and therefore it is not an information economy towards which we are moving. (Goldhaber Citation1997)

The data-oil analogy suggests that data is a natural resource, which can be gathered and refined to produce a valuable commodity (The Economist Citation2017); but the analogy only goes so far. First of all, data is, of course, not a naturally occurring phenomenon at all: companies like Meta (née Facebook) and Google that create value from data also create the data from which the value is created. The data is only attributed with potential value inasmuch as it’s credited with being, itself, a derivative of some still-more unrefined natural phenomenon, which the data-gathering system can capture and represent in a format amenable to further processing. Second, this first fact means that not all data have value – only those derived from natural phenomena that are themselves attributed with value. And while there might be potential value in other kinds of data, the data-oil analogy has been drawn in reference to one very specific kind of data: behavior.Footnote1

Companies such as Google and Meta spin data into revenue through “online behavioral advertising,” or OBA (Raley Citation2013). As explained by Sophie Boerman and her collaborators, “OBA, which is also called ‘online profiling’ and ‘behavioral targeting’” is “the practice of monitoring people’s online behavior and using the collected information to show people individually targeted advertisements” (Boerman, Kruikemeier, and Zuiderveen Borgesius Citation2017, 364, italics in original). Data as data is more-or-less worthless in line with Goldhaber’s original argument, but data as behavior has worth because knowledge of behavior is believed to increase the efficacy of advertising, allowing it to be delivered as surgical strikes on individual consumers’ personalities. Understanding a person’s behavior is believed to open up the possibility of changing a person’s behavior.

According to the logic on which online behavioral advertising is founded, behavior is a real-world phenomenon that can be represented by data. The attribution of financial value to this data arises from a belief that it is directly connected to external, physical events (the actions of consumers) that, unlike data, are constrained in their supply and accessibility and therefore valuable. But if behavior really is an objective physical phenomenon that is being represented as data, where is it? There doesn’t seem to be any specific thing in the world we can point to and identify as behavior, so how can online platforms quantify it – and how can we even be certain it’s really there at all?

What is behavior?

Behavior has been an object of scientific enquiry for more than a century, and there has perhaps never been more widespread faith in its economic and explanatory value than there is today. In addition to its commodification through behavioral advertising, technology companies employ behavioral design (Cash, Hartlev, and Durazo Citation2017) to shape users’ interactions with devices and interfaces; in 2017, Richard Thaler was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his work in the field of behavioral economics, which has established the “nudge” (Thaler and Sunstein Citation2009) as an internationally influential principle of governmentality; in the same year, a group of neuroscientists published a paper titled “Neuroscience needs behavior” (Krakauer et al. Citation2017), in which they complained that a focus on the microscopic, physiological scale of “neural circuits” has led to a neglect of the behavior that brain research should ultimately be seeking to explain:

Insofar as the goal of a neuroscience research question is to explain some behavior … the behavioral research must be considered, for the most part, epistemologically prior. The neural basis of behavior cannot be properly characterized without first allowing for independent detailed study of the behavior itself. (Krakauer et al. Citation2017, 487–88, italics in original)

This field overlaps with, but is distinct from, computer science and robotics. It treats machine behaviour empirically. This is akin to how ethology and behavioural ecology study animal behaviour by integrating physiology and biochemistry – intrinsic properties – with the study of ecology and evolution – properties shaped by the environment. (Rahwan et al. Citation2019, 477)

Psychology, although describing itself as “the science of behavior,” has not to date arrived at any consensus in the matter of what the concept of “behavior” means … A review of 26 psychology dictionaries (both standard and online) and textbook glossaries by this author revealed that only seven of them offered definitions of “behavior” at all, reflecting a widespread tendency in the field to ignore the question entirely. (Bergner Citation2011, 147)

Similarly, in the field of behavioral biology, Daniel A. Levitis and colleagues write,

What do we mean by this word, “behaviour”? There are numerous published definitions, and for many biologists the meaning is simply and clearly intuitive. However, satisfying definitions of this word, in the context of modern biology, are hard to find. Many definitions are so vague as to be impossible to apply. Others are crafted around a particular taxon such that members of other taxa by definition cannot behave … Still other definitions make distinctions that exclude phenomena widely considered to be behaviours or that fail to exclude phenomena most biologists would agree are not behaviours. Many sources, including textbooks on the topic of behaviour, fail to define their subject matter, assuming that the reader knows what is meant. (Levitis, Lidicker, and Freund Citation2009, 103)

In fact, Levitis and colleagues had members of three scientific societies that produce behavioral biology journals answer a survey in which they had to state whether each of 20 different animal activities constituted behavior. Of the 20, there was not a single case that every respondent could agree qualified as behavior (Levitis, Lidicker, and Freund Citation2009, 1073).

The reason why behavior is so difficult to pin down is that, in reality, it is not an unmediated objective phenomenon at all. It is not a natural feature of the world that is represented as data; rather, behavior is itself constructed from data. It is simply another layer of data beneath the data used in online behavioral advertising, for example. This lower stratum of data existed before the advent of Google, but it hasn’t existed forever. A belief that the data-construct referred to as behavior does, itself, represent real-world phenomena, and furthermore that it has financial value, is a product of behavior’s twentieth century permeation of American scientific, institutional, and popular cultures.

Behaviorism

Explanations for why human beings do the things they do existed long before the twentieth century, of course. But back then, behavior as it’s understood today did not yet exist as a basis for those explanations. For example, in the nineteenth century, habit, rather than behavior, provided a dominant framework for explaining the combination of predictability and unpredictability that characterizes human activity.

Habit has an intellectual history reaching back to Aristotle, but it gained a particular prominence in nineteenth century thinking after Félix Ravaisson’s 1838 doctoral thesis, Of Habit – or De L’Habitude – made him a star of nineteenth century French philosophy (Ravaisson Citation2008). Ravaisson presented habit as a principle that could be found throughout the animate and inanimate world, but it was notably applied to accounts of human conduct, for example in the psychology of William James (Citation1976) and in American pragmatist philosophy more generally. However, toward the end of the nineteenth century, the dominant understanding of habit began to shift due to the emergence of psychology as a discrete academic discipline, one with its own university departments and practitioners, who believed their dedication to scientific rigor distinguished them from philosophers like James (see Camic Citation1986; Coon Citation1993; Pedwell Citation2017).

The term habit was also commonly used in the life sciences of the time, but the actions it referred to in that context were most likely to be those investigated through animal experiments, giving it a meaning closer to reflexes or instincts than the acquired adaptations seen in human patterns of action or culture. In the early twentieth century, as the influence of experimental psychology grew, habit was increasingly understood to refer to basic and innate responses to external stimuli of the kind studied in psychology laboratories rather than the more diffuse and complex influences implicit in the use of the word by figures such as Émile Durkheim or Max Weber. As the former meaning became dominant, habit fell out of favor in the humanities and social sciences and became primarily a scientific term.

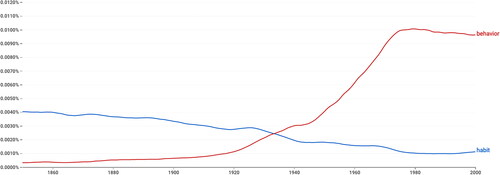

However, habit’s status as an abstraction existing across multiple, sometimes internally heterogeneous, events, posed a challenge for scientific enquiry’s requirement of reproducibility. While the actions of living bodies could be explained as simple cause and effect at the level of basic reflexes, beyond this they were frustratingly inconsistent. But a solution to this problem had appeared at the end of the nineteenth century in the form of probability, which Ian Hacking has described as “the philosophical success story of the first half of the twentieth century” (Hacking Citation1990, 4). Whereas, during the Enlightenment, it had been believed that all events were ultimately explicable and predictable according to fundamental laws – all that was required was the discovery of those laws – the success of probability as a concept lay precisely in its ability to assimilate phenomena that stubbornly resisted reduction to such laws. A probabilistic representation of events grouped them into stable units despite their internal inconsistencies, allowing an unstable collection of phenomena to be crystalized into a single object of study. And before long, psychology replaced habit with a word chosen to specifically describe this probabilistic rendering of patterns of action: behavior (Camic Citation1986; also see ).

Figure 1. Chart from Google Books Ngram Viewer that plots the twentieth century frequency of the word “behavior” in the books in Google’s digitized library.Footnote2

The popularization of this new term and the probabilistic representation of action it signified was driven by successive scientific celebrities. First came Ivan Pavlov, whose behavioral research was sufficiently sensational to have remained a part of popular culture for over a century, appearing in everything from Thomas Pynchon novels to songs by The Rolling Stones. Pavlov’s work on conditioned response established behavior as a probabilistic explanation for the patterns of activity produced by living bodies, empirically demonstrated via modification of an organism’s environment. Although resulting from laboratory experiments on animals, Pavlov’s findings were widely hailed as unlocking fundamental mysteries of human psychology as well. H.G. Wells described Pavlov as “a star which lights the world, shining above a vista hitherto unexplored” (cited in Skinner Citation1976, 300–01).

Then, in 1913, the American John B. Watson published the paper “Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It” (1913), establishing behaviorism as a movement that would become dominant in psychology. Watson explicitly argued that the principles discovered in his own animal experiments could provide a basis for explanations of human activity. Behavior, as the probability of particular actions, could be analyzed and controlled through the alteration of environmental variables, and doing so could explain human conduct without the need for recourse to things like culture or understanding, subjectivity or free will.

Psychology as the behaviorist views it is a purely objective experimental branch of natural science. Its theoretical goal is the prediction and control of behavior. Introspection forms no essential part of its methods, nor is the scientific value of its data dependent upon the readiness with which they lend themselves to interpretation in terms of consciousness. (Watson Citation1913, 158)

Although Watson’s academic career was suddenly ended in 1920 by a scandalous divorce following an affair with one of his graduate students, he was subsequently employed by J. Walter Thompson, at that time possibly the largest advertising company in the world. Watson was hired in the belief that behaviorism could provide a scientific approach to the influencing of consumers, and, although he seemingly made little progress – or even effort – toward this goal, in his new position he was nevertheless a successful advocate for behaviorism in the business world and amongst the broader public (Kreshel Citation1990). The study of consumer behavior became firmly established as a key tool of advertising, pursued using the latest technologies of data-gathering and -analysis up to the present era of OBA.

But it was B.F. Skinner who brought behavior its greatest fame and infamy. In the words of the psychologist Bernard Baars,

B.F. Skinner was for decades the most famous scientist of any kind in the United States. In a century of unmatched creativity in physics, biology, medicine and all the other sciences, it was Skinner who dominated the public stage. (Baars Citation2003, 9)

In Cold War America, a science of mass behavioral engineering was attractive: the threat of nuclear attack on the civilian population made the fostering of public morale and suppression of panic an important consideration (Orr Citation2004), and during the 1960s its potential to neutralize protest movements and civil disobedience was seductive for defenders of the status quo.

Having expanded the science of behavior by adding operant conditioning to Pavlov’s classical conditioning,Footnote3 Skinner became an influential public intellectual as the application of behaviorism spread. Behaviorism claimed human behavior could be predictably and reliably influenced by changes to environmental stimuli, and so its principles came to be applied in prisons, schools and reformatories, and institutions for the mentally ill and disabled. But Skinner called for behavioral engineering to go further:

We could solve our problems quickly enough if we could adjust the growth of the world’s population as precisely as we adjust the course of a spaceship, or improve agriculture and industry with some of the confidence with which we accelerate high-energy particles, or move towards a peaceful world with something like the steady progress with which physics has approached absolute zero (even though both remain presumably out of reach). But a behavioural technology comparable in power and precision to physical and biological technology is lacking, and those who do not find the very possibility ridiculous are more likely to be frightened by it than reassured. (Skinner Citation1973, 10–11)

completely at odds with our basic belief in the dignity and worth of the individual. To the behaviorist, man is not an individual; he is one of a herd, a particle in a mass of humanity who does not know what is good for him and who needs to be saved from himself by a superior elite using intellectual cattle prods. (Agnew Citation1972, 84)

Skinner’s legacy

The specter of Skinner looms large in Shoshana Zuboff’s The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (2019), which draws a direct intellectual lineage from twentieth century behaviorism to the behavioral technologies of contemporary online platforms. Her awareness of this lineage results from having been present for the anti-Skinner backlash, having been a postgraduate student at Harvard in the 1970s when Skinner was employed there (Zuboff Citation2019, 361). As a result, her critique of behaviorism and behavioral engineering is founded on a reactivation of the anti-Skinnerian position of the time; but simply thawing out that debate after half a century is not enough to fully address behavior’s role in the contemporary moment.

One reason for caution is that much of the demonization of Skinner seen in the 1970s was unfair and relied on a caricaturing of his thought. Much of Zuboff’s account of the backlash focuses on the Ervin committee report, claiming that “Skinnerian behavioral engineering was singled out for critical examination” (Zuboff Citation2019, 325) in its pages, making the report an official governmental repudiation of his ideas. But in reality, Skinner’s ideas were of marginal concern to the committee: “Of all the methods of behavior modification presently being employed in the United States” the report reads, the kind of positive reinforcement espoused by Skinner was “perhaps the most benign” (Staff of the Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights of the Committee on the Judiciary Citation1974, 16). The report cites Skinner as an authority on behavior, but contains no direct criticism of him or his work – aside from that implicit in a disapproving reference to “the behavioral psychologist, who operates from the premise of determinism,” and therefore considers “philosophical notions of ‘freedom’ and ‘dignity’ … irrelevant” (Staff of the Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights of the Committee on the Judiciary Citation1974, 627).

By the 1970s, behaviorism’s decades of intellectual dominance had firmly established the concept of behavior as central to the understanding of human conduct, and anxieties created by the Cold War and civil unrest had driven practical attempts at its control. A whole armamentarium of behavior-changing techniques had been assembled, up to and including aversion therapies that utilized drugs or electric shocks, and even lobotomization. Skinner was a victim of the success of both his ideas and himself as a public figure: his dominant position in the science of behavior, and his high public profile and scientific critique of the sacred cows of liberal humanism, made him seem representative of – and thus to some degree answerable for – the worst excesses of behavior modification, excesses with which he was not associated and to which he was in many cases intellectually and morally opposed. In a submission to the Ervin committee, two behavioral psychologists, Michael A. Milan and John M. McKee, decried the lumping of behaviorism with a rogue’s gallery of ethically questionable techniques, complaining that:

A variety of medical techniques, such as psychosurgery, chemotherapy, and electrode implantation, are frequently attributed to the behavior modifier when, in fact, they do not fall within the scope of this discipline. Although these procedures do indeed result in behavior change, they should not be confused with behavior modification procedures for they are not applications of the principles of conditioning and learning …

[T]he term “behavior” has gained such popularity among non-behaviorists in both professional and lay circles that its original and appropriate meaning has all but been lost. In many instances, the forced use of “behavior” as an adjective or a suffix appears more a thinly disguised attempt to “update” outmoded formulations and approaches to human behavior than it is the adoption and deployment of a new conceptual system. (Staff of the Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights of the Committee on the Judiciary Citation1974, 461–63)

Intelligent people no longer believe that men are possessed by demons … but human behaviour is still commonly attributed to indwelling agents …

Unable to understand how or why the person we see behaves as he does, we attribute his behaviour to a person we cannot see, whose behaviour we cannot explain either but about whom we are not inclined to ask questions … He initiates, originates, and creates, and in doing so he remains, as he was for the Greeks, divine. We say that he is autonomous – and, so far as a science of behaviour is concerned, that means miraculous. (Skinner Citation1973, 13, 19)

Skinner’s high profile as a public intellectual, and the fact that the attacks on him and behaviorism took place in the public eye, ensured that this hostile sentiment irreversibly tarnished both in the popular imagination, and the Ervin committee report and public attacks on Freedom and Dignity are often cast as the death knell of behaviorism. According to this account, the 1970s saw an intellectual and moral rejection of a perspective whose assumptions about the impossibility of accessing interior mental phenomena in a scientifically rigorous way would later be rejected by fMRI-wielding cognitive scientists in any event. While Zuboff explicitly identifies online behavioral profiling as an heir to behaviorism, she characterizes this as a return from the dead, after decades of absence, of an idea whose very anachronism encourages us to view it with suspicion.

But while Zuboff’s account portrays a 1970s vanquishing of behavioral engineering, undone when it would later “resurface in a wholly unexpected incarnation as a creature of the market” (Zuboff Citation2019, 325), historian of psychology Alexandra Rutherford argues that the response to the criticism of the time was often only “a subtle shift in terminology and a modification of technique” (2006, 217). In fact, Zuboff herself repeats Rutherford’s quoting of a psychologist working with prison inmates in the 1970s: “We’re doing what we always did before … To call it behavior modification just makes things more difficult. Who needs it?” (Rutherford Citation2006, 217, cf. Zuboff Citation2019, 325). In reality, the underlying dominance of behavior as a concept continued uninterrupted throughout the remainder of the twentieth century and beyond, and today it remains the entirely naturalized foundation of our understanding of human conduct.

Skinner’s behavior modification proposals relied on the principle of operant conditioning through positive reinforcement. Rather than provoking moral revulsion and rejection in the 1970s, this approach, with its economy of stamps and stickers, has for some time been so widely accepted in schools and elsewhere as to now be almost entirely naturalized and unquestioned. In fact, learning through reinforcement has remained sufficiently influential as a model of human development that it has informed the design of many of the artificial intelligence systems that today perform behavioral analysis. And even the deployment of behavior modification as a tool of government was not out of favor for long. From the 1990s onwards, behavioral economics and “nudge”-based behavior-modification programs (Thaler and Sunstein Citation2009) were enthusiastically welcomed by governments around the world.

Nonetheless, it is true that the continuity between twentieth century behaviorist psychology and twenty-first century behavioral economics and online behavioral profiling has been obscured. As Alexandra Rutherford notes, even those engaged in Skinnerian behavior modification came to avoid direct association with the project after the backlash of the 1970s. Just as behaviorists had once complained about the “forced” use of the term behavior in an attempt to align old practices with the influential “new conceptual system,” later they would learn to avoid the language of behaviorism even as the conceptual system itself endured.

In a review of Cass Sunstein’s book Why Nudge? The Politics of Libertarian Paternalism (Sunstein Citation2014) for the Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, Howard Rachlin writes:

Readers of JEAB will certainly want to know what Sunstein says about Skinner. The answer is: Nothing. Neither Skinner’s name nor the name of any behaviorist I am aware of appears in the index. There may be good reasons for this omission. (Rachlin Citation2015, 201)

But my aim is not to establish direct continuity between behaviorist psychology and behavioral economics, or between both of these and online behavioral profiling. There are significant differences between each of these endeavors. However, there is also a clear intellectual continuity between them. Most obviously, without behaviorism, neither behavioral economics nor online behavioral profiling would have their object of investigation: behavior itself. It also seems unlikely to be a coincidence that the take-off of behavioral economics in the 1990s coincided with the popularization of personal computing and the Internet. The digitalization of culture resulted in an unprecedented explosion in both the numerical quantification of varied aspects of human life and the capacity to subject this quantification to statistical analysis, and the concept of behavior provided a model of the self suited to this analysis where so many others are not suited at all. Twentieth century psychology’s development of behavior as a way of quantifying human actions equipped twenty-first century technocrats and corporations with the means to translate human beings into the raw material of algorithmic analysis. Behavioral economists and Google engineers might not be behaviorists in the sense that B.F. Skinner or John B. Watson were behaviorists, but they are behaviorists in the sense that behavior provides the foundation of their worldview, and the generation, quantification, and modification of behavior is their stock in trade.

Against humanism

As a repetition of the 1970s critique of Skinner, Zuboff’s position rehearses the defense of the liberal subject and “the American traditions of individualism, human dignity, and self-reliance” that were brought to bear on him at the time. She explicitly asserts her belief in free will and the need to defend it from such a threat (Zuboff Citation2019), and there are certainly many today who would share her position. At the same time, however, while Skinner’s belief that society should be shepherded by a class of behavioral engineers whose rationality and objectivity would allow them to determine the greatest good seems as suspect today as it did in the 1970s – if not more so – it’s also true that, following the anti-humanism of Michel Foucault later in the 1970s, charges of disparaging the rational, autonomous, internalized subject of Enlightenment thought don’t pack the same punch they once did. Over the intervening years, it’s become less certain that the liberal humanist subject deserves to be defended in the first place. In any event, today’s attempts to defend the liberal humanist subject from big tech are just as compromised by its irreconcilability with a behaviorist view as were 1970s attempts to defend it from institutional behavioral engineering.

The autonomous liberal subject and behavior exist in two different, and irreconcilable, intellectual paradigms, and as a consequence one cannot be set against the other in any intellectually coherent way. For example, Zuboff’s analysis is encapsulated in the following quote:

As to this species of power, I name it instrumentarianism, defined as the instrumentation and instrumentalization of behavior for the purposes of modification, prediction, monetization, and control. In this formulation, “instrumentation” refers to the puppet: the ubiquitous connected material architecture of sensate computation that renders, interprets, and actuates human experience. (Zuboff Citation2019, 352, italics in original)

Forget the cliché that if it’s free, “You are the product.” You are not the product; you are the abandoned carcass. The “product” derives from the surplus that is ripped from your life. (Zuboff Citation2019, 377)

The behaviorist doesn’t believe in the existence of the liberal subject as an internally motivated free agent, but, more than that, even if the liberal subject does exist, it does not have any behavior to modify – at least not in the sense in which behavior is understood by behaviorists or online platforms. Behavior, as a probabilistic pattern of actions, exists only at the statistical level of populations, and so – like all statistics – cannot be isolated at the level of individual actors. Even at its most hubristic and unguarded, a company like Meta or Google would never claim to have the power to directly control the actions of a particular selected individual, or even believe in the possibility of one day doing so. Success for these companies is something like changing the average number of people who decide to purchase a particular product from 2 out of every 100 to 5 out of every 100; but what does this success mean at the level of a single person? Like any statistical effect, at the level of individual psychology it does not mean anything. There is simply no way of translating such an effect into the terms of liberal subjectivity.

It might be objected that, whatever the history of the term behavior, it has long since left the specialized intellectual milieu of behaviorism and become a part of common-sense understandings of the liberal self. As evidenced by behavioral economics as well as everyday usage, today behavior and the liberal subject seem to co-exist happily in popular discourse. They have been reconciled with one another through a belief that behavior is merely a product of the liberal subject, an observable external expression of an internalized self.

Online surveillance is widely understood to be a threat to the liberal subject because the liberal subject is widely understood to be its true target – behavior is just the route taken to get there. Behavioral data are only of interest because – various (pseudo-)scientific undertakings such as neuromarketing and emotion recognition notwithstanding – what a person does is the only available objective indication of that person’s internal drives or motivations. A belief that our data constitute a kind of “digital exhaust” or “digital shadow,” which betrays who we are to tech companies, arises from a belief that that all our behavior, online or not, is a kind of exhaust or shadow left by an invisible internal subjectivity. A Google algorithm can supposedly identify things like gender, class, sexuality or political persuasion from what we do online because externally observable behaviors are expressions of a stable inner self, making it possible to work back from (surveillable and ephemeral) behaviors to (non-surveillable and stable) identity categories.Footnote4

However, when looked at more closely, the cracks in this explanation start to show. While online behavioral targeting might frequently invoke the language of liberal subjectivity (categorizing a user as a child, for example, or a woman, or politically conservative), this shared language is a red herring. While a Google algorithm might categorize an individual user as “Asian,” say, the term “Asian” is for that system a free-floating signifier that has no necessary relationship with historical beliefs about ethnicity, culture or phenotype. Such terms are useful presumably because they provide a point of articulation between the advertising industry – which is still likely to understand such descriptors in terms of traditional beliefs about the personalities and values of different consumers – and behavioral profiling, where these things are irrelevant, allowing discussions between advertisers and online platforms to avoid collapsing into mutual incomprehension.

But in reality there is no liberal subject or internalized identity in these systems. In past systems of surveillance, observed behavior needed to be structured and narrativized to create a posited “true” identity (terrorist, political radical, criminal, etc.), which could in turn provide a basis for prediction. Behaviorism’s innovation was to provide a system that didn’t require the (empirically non-verifiable) middle ground of identity: through careful quantification and probabilistic analysis, it allowed prediction to exist entirely in an external, objective realm. The power of machine-learning systems lies precisely in their ability to produce useful outcomes in the absence of any hypothesis or conceptual framework; they simply evaluate a multitude of variables to find the one that generates the most effective predictions (Yeung Citation2018). This “end of theory” (Anderson Citation2008) renders human understandings of personal identity and motivation irrelevant. With online profiling, behavior is both the input and the output of a closed system that obviates any other form of knowledge.

Some online platforms allow users to look up the categories to which they’ve been assigned through behavioral profiling; when doing so, it’s not unusual to find you’ve been assigned to one or more categories that don’t accord with your personal identity. For example, you might find that you’ve been identified as male, when you identify as female. Seeing this might lessen your anxieties about online surveillance; clearly the system isn’t as all-knowing as some accounts have suggested, and even if it is capable of influencing a person, any attempt to do so in your case would be targeting the wrong kind of person. But to think this would be an error borne of conflating the meaning of “male” and “female” as descriptors of personal identity and “male” and “female” as descriptors of behavior, when in reality there is no connection between the two. If a person describes herself as female, “female” is being used to describe her personal identity; when Google’s behavioral advertising system describes a person as female, “female” is a probabilistic cluster of behavioral measurements. It’s perfectly possible for an individual to have the personal identity of “female” and the behavioral category of “male,” and for each to be perfectly accurate and correct according to its frame of reference.

If you, a woman, have been assigned to the behavioral category of male, this has happened because you fit a set of behavioral parameters described as “male,” and Google will assess the probability of you and everyone else in that category responding to certain advertisements. Google’s attempts to influence you with advertising might be successful or they might not, but the chance of success is not affected by whether you personally identify as a man or not; the behavioral category of “male” corresponds only to a certain set of behavioral indicators, and you have been correctly placed in that category if you’ve generated those behavioral indicators – how you describe your gender is irrelevant to this. Every single individual labeled “male” in Google’s system of behavioral targeting could identify as female, and the system would work just as well as if every single individual identified as male. How you describe yourself – or even how other human beings describe you – according to a humanist conception of individual identity is simply irrelevant to this system because, shared category names notwithstanding, they are utterly unrelated to one another.

Which returns us to the question of just what, precisely, is at stake in online surveillance. Although Shoshana Zuboff (Citation2019) is attuned to the indifference to subjectivity and interiority that distinguishes twenty-first century online profiling from twentieth century totalitarianism, she remains unclear regarding precisely what is placed at risk in this newer regime. Totalitarianism threatens the annihilation of the liberal humanist self by a program of state domination that remakes the individual in its image, but the behaviorism of big tech is not invested in either the self or some master ideology or worldview. When she does come to invoke some future regime based around behavioral profiling, Zuboff focuses on promises made by tech companies about their capacity to improve the efficiency of workers – that is, the application of their technology to the governance of working bodies. But the administration of employees aimed at maximizing their pliability and productivity is importantly different from the wider context of surveillance capitalism, where there is no unified set of aims or values concerning what kind of people there should be. In areas like social media or search, for example, online platforms don’t need users to engage in any particular kind of behavior; all behavior is equally promising grist for the mill.

While online platforms may engage in what Karen Yeung terms “algorithmic regulation” (2018), these behavior modification efforts are not aimed at making linear progress toward some fixed external goal such as communism, law and order, patriotism or a reduction in birth rate. Their behavior modification efforts are circular, aiming to maintain a closed loop that runs from using social media so as to generate behavioral data, to using social media so as to receive advertising determined by that behavioral data. It is a behavior-modification system that is not designed to serve some external ideal or goal; instead, its only purpose is to perpetuate itself, functioning as a closed engine that throws off money to be collected by its owner but never moves in any particular direction.

The behavioral engineering of Skinner (and later behavioral economists) seeks to shift human behavior to fit particular goals aligned with the greater good (such as reducing crime, pollution, and overpopulation), and such goals might very well be in conflict with the desires of an individual. But the behavioral engineering of a company like Google or Meta is not in the service of some fixed, pre-determined outcome – it simply follows the money. While an infamous Google X video from 2016 imagines Google’s behavioral technologies being put into the service of a “species-level” project of behavior modification, the fact remains that Google has no reason to ever employ such a “selfish ledger” (Savov Citation2018) in the service of some posited greater good: Google, unlike a totalitarian regime, is not motivated by a vision of some “perfect” society; it is committed to no particular outcome that could guide such a project. Google seeks to influence consumption in line with the commercial interests of advertisers, of course, but these are shifting and contingent aims that do not fit into some unified ultimate outcome toward which users are being driven. While twentieth century critiques could characterize behavioral engineering as an attempt to change the individual to fit some externally imposed determination concerning whom they should be, Google and Meta have no such template to which their users must conform. In fact, rather than turning users into someone else, they see themselves as, if anything, making them more like the person they already are; that is, their systems work by feeding back the outcomes of users’ decisions, creating experiences that claim to be ever-more tailored to the individual tastes and personalities of each user. The hold of these platforms over users is presented as evidence that they are not trying to impose some alien set of values and interests on them at all but are rather subordinating themselves to each person’s unique subjectivity. In the face of this, an intellectual opposition between the desires of the individual and the desires of the behavioral engineer seems hard to maintain.

Conclusion

The liberal humanist self does not exist in a behaviorist worldview, and behavior does not exist in liberal humanist one. This fact does not establish that there is nothing objectionable about online surveillance or that we should submit to it without complaint, however. Rather, it indicates that, while simple appeals to liberal humanist values in critiques of online surveillance practices are inadequate, it is also possible to contest these practices at a more foundational level than their feared effects.

Catastrophizing about AI is perhaps a helpful point of comparison here: while there are plenty of reasons to be concerned about AI technologies, very real practical problems are often eclipsed by implausible scenarios founded on an uncritical acceptance of tech companies’ overblown claims about the efficacy and applicability of what they have created. Similarly, critiques of online surveillance and behavior modification tend to accept without question platforms’ claims to be gleaning valuable insights into who we truly are and making productive use of them.

Given that these critiques most often invoke liberal humanism – a frame of understanding according to which these overblown claims can’t be true – it’s inevitable that the results can be intellectually problematic. A good illustration of this was the techno-dystopian handwringing over the 2016 US presidential election, where attempts to defend a model of democracy built on the idea of citizens as rational, autonomous agents alleged that many citizens’ voting choices resulted from crude psychological manipulation by companies like Cambridge Analytica. If such external manipulation is possible, then democratic elections were presumably never truly free to begin with. While it’s true that the principles of democracy and liberalism have for much of their history been combined with a belief that certain groups of people don’t possess the rationality and wisdom necessary to make responsible decisions, this only highlights the need to subject models of individual action to ongoing critical interrogation, and this applies to the behaviorist models used by tech companies at least as much as it does to liberal humanist ones.

Of course there can be a sensible middle ground somewhere between citizens as entirely autonomous and citizens as responding mechanistically to external stimuli. But these two extremes can’t be reconciled simply by believing them both at the same time. Instead, critiques of online surveillance should begin with a critical investigation of the behavior that is its object: what – if anything – constitutes that behavior, and what ends – if any – can it be put to? And this critical investigation must start from an acknowledgement of behavior as not simply an external phenomenon that comes to be captured and worked on by systems of online surveillance, but rather as something produced by them.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 While it is true that some kinds of non-behavioral data have value in this economy (e.g. a person’s name and address), this data only has value inasmuch as it provides a fixed identifier that allows behavioral data to be attributed to a single person.

3 Unlike Pavlov’s work, operant conditioning was a framework applicable to conscious, voluntary actions, giving it much wider reach as an explanation for and potential modifier of human behavior: “When a bit of behaviour is followed by a certain kind of consequence, it is more likely to occur again, and a consequence having this effect is called a reinforcer. Food, for example, is a reinforcer to a hungry organism; anything the organism does that is followed by the receipt of food is more likely to be done again whenever the organism is hungry. Some stimuli are called negative reinforcers; any response which reduces the intensity of such a stimulus – or ends it – is more likely to be emitted when the stimulus recurs. Thus, if a person escapes from a hot sun when he moves under cover, he is more likely to move under cover when the sun is again hot. The reduction in temperature reinforces the behaviour it is “contingent upon” – that is, the behaviour it follows. Operant conditioning also occurs when a person simply avoids a hot sun – when, roughly speaking, he escapes from the threat of a hot sun.” (Skinner Citation1973, 31–32)

4 It might be useful to remind the reader here that, while this article includes an account of the origins of behavior within psychology, and while not only behavior but other terms used, such as identity and habit, have specialized meanings within psychology, this is not a psychology paper, and these terms are being used in line with their broader application outside the discipline.

References

- ABC. 2019. Your phone isn’t spying on you: It’s listening to your "voodoo doll". ABC.net.au, May 2. Accessed March 23, 2024. https://www.abc.net.au/triplej/programs/hack/your-phone-is-not-spying-its-listening-to-your-voodoo-doll/11073686

- Agnew, S. T. 1972. Agnew’s blast at behaviourism. Psychology Today, January 4, 84, 87.

- Anderson, C. 2008. The end of theory: The data deluge makes the scientific method obsolete. Wired, June 23. Accessed March 23, 2024. https://www.wired.com/2008/06/pb-theory/

- Baars, B. 2003. The double life of B.F. Skinner: Inner conflict, dissociation and the scientific taboo against consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies 10 (1):5–25.

- Bergner, R. M. 2011. What is behavior? And so what? New Ideas in Psychology 29 (2):147–55. doi:10.1016/j.newideapsych.2010.08.001.

- Boerman, S. C., S. Kruikemeier, and F. J. Zuiderveen Borgesius. 2017. Online behavioral advertising: A literature review and research agenda. Journal of Advertising 46 (3):363–76. doi:10.1080/00913367.2017.1339368.

- Camic, C. 1986. The matter of habit. American Journal of Sociology 91 (5):1039–87. doi:10.1086/228386.

- Cash, P. J., C. G. Hartlev, and C. B. Durazo. 2017. Behavioural design: A process for integrating behaviour change and design. Design Studies 48:96–128. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2016.10.001.

- Cheney-Lippold, J. 2011. A new algorithmic identity: Soft biopolitics and the modulation of control. Theory, Culture & Society 28 (6):164–81. doi:10.1177/0263276411424420.

- Clarke, R. 1994. The digital persona and its application to data surveillance. The Information Society 10 (2):77–92. doi:10.1080/01972243.1994.9960160.

- Coon, D. J. 1993. Standardizing the subject: Experimental psychologists, introspection, and the quest for a technoscientific ideal. Technology and Culture 34 (4):757–83.

- Goldhaber, M. H. 1997. The attention economy and the net. First Monday 2 (4). Accessed March 23, 2024. https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/519/440

- Hacking, I. 1990. The taming of chance. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- James, W. 1976. Habit. New York: Norwood.

- Jones, R., J. Pykett, and M. Whitehead. 2013. Changing behaviours: On the rise of the psychological state. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Krakauer, J. W., A. A. Ghazanfar, A. Gomez-Marin, M. A. MacIver, and D. Poeppel. 2017. Neuroscience needs behavior: Correcting a reductionist bias. Neuron 93 (3):480–90. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2016.12.041.

- Kreshel, P. J. 1990. J. B. Watson at J. Walter Thompson: The legitimation of “science” in advertising. Journal of Advertising 19 (2):49–59. doi:10.1080/00913367.1990.10673187.

- Levitis, D. A., W. Z. Lidicker, Jr., and G. Freund. 2009. Behavioural biologists do not agree on what constitutes behaviour. Animal Behaviour 78 (1):103–10. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.03.018.

- Nichols, J. 2004. Data doubles: Surveillance of subjects without substance. Accessed March 23, 2024. https://journals.uvic.ca/index.php/ctheory/article/view/14546/5393

- Orr, J. 2004. The militarization of inner space. Critical Sociology 30 (2):451–81. doi:10.1163/156916304323072170.

- Pedwell, C. 2017. Habit and the politics of social change: A comparison of nudge theory and pragmatist philosophy. Body & Society 23 (4):59–94. doi:10.1177/1357034X17734619.

- Rachlin, H. 2015. Choice architecture: A review of Why nudge? The politics of libertarian paternalism. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior 104 (2):198–203. doi:10.1002/jeab.163.

- Rahwan, I., M. Cebrian, N. Obradovich, J. Bongard, J.-F. Bonnefon, C. Breazeal, J. W. Crandall, N. A. Christakis, I. D. Couzin, M. O. Jackson, N. R. Jennings, E. Kamar, I. M. Kloumann, H. Larochelle, D. Lazer, R. McElreath, A. Mislove, D. C. Parkes, A. Pentland, M. E. Roberts, A. Shariff, J. B. Tenenbaum, and M. Wellman. 2019. Machine behaviour. Nature 568 (7753):477–86. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1138-y.

- Raley, R. 2013. Dataveillance and counterveillance. In Raw data” is an oxymoron, ed. L. Gitelman, 121–45. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Ravaisson, F. 2008. Of habit. London: Continuum.

- Rutherford, A. 2000. Radical behaviorism and psychology’s public: B.F. Skinner in the popular press, 1934–1990. History of Psychology 3 (4):371–95. doi:10.1037/1093-4510.3.4.371.

- Rutherford, A. 2006. The social control of behavior control: Behavior modification, Individual Rights, and research ethics in America, 1971–1979. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 42 (3):203–20. doi:10.1002/jhbs.20169.

- Savov, V. 2018. Google’s selfish ledger is an unsettling vision of Silicon Valley social engineering. The Verge, May 17. Accessed March 31, 2024. https://www.theverge.com/2018/5/17/17344250/google-x-selfish-ledger-video-data-privacy

- Skinner, B. F. 1976. Particulars of my life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Skinner, B. F. 1973. Beyond freedom and dignity. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

- Staff of the Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights of the Committee on the Judiciary. 1974. Individual rights and the federal role in behavior modification. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Sunstein, C. R. 2014. Why nudge? The politics of libertarian paternalism. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Thaler, R. H. 2016. Behavioral economics: Past, present, and future. American Economic Review 106 (7):1577–600. doi:10.1257/aer.106.7.1577.

- Thaler, R. H. 2015. Misbehaving: The making of behavioral economics. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Thaler, R. H., and C. R. Sunstein. 2009. Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. New York: Penguin.

- The Economist. 2017. The world’s most valuable resource is no longer oil, but data. The Economist, May 6. Accessed March 31, 2024. https://www.economist.com/leaders/2017/05/06/the-worlds-most-valuable-resource-is-no-longer-oil-but-data

- Uher, J. 2016. What is behaviour? And (when) is language behaviour? A metatheoretical definition. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 46 (4):475–501. doi:10.1111/jtsb.12104.

- Watson, J. B. 1913. Psychology as the behaviorist views it. Psychological Review 20 (2):158–77. doi:10.1037/h0074428.

- Yeung, K. 2017. Hypernudge": Big data as a mode of regulation by design. Information, Communication & Society 20 (1):118–36. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2016.1186713.

- Yeung, K. 2018. Algorithmic regulation: A critical interrogation. Regulation & Governance 12 (4):505–23. doi:10.1111/rego.12158.

- Zuboff, S. 2019. The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. New York: Public Affairs.