Abstract

Urban regeneration in post-reform China has become a fertile ground for the transition towards collaborative planning, which serves as a powerful tool for managing conflicts and addressing complex urban challenges. This article aims to delve into the micro-level processes that underpin the emergence of collaborative planning in practical urban regeneration projects in China. By shedding light on these micro-level processes of conflict resolution, we aim to provide a deeper understanding of how collaborative planning is implemented within the Chinese authoritarian context. Deliberative knowledge utilisation is intricately interwoven with the process of problem framing, exerting a significant influence on how conflicts are approached and ultimately resolved. We employ framing analysis as an analytical approach to demonstrate how problem framing is shaped by deliberative knowledge utilisation and is discursively constructed, drawing on empirical studies of the contentious Enning Road case in Guangzhou.

Regarding the problem framing related to the legitimacy of demolition and planning, institutional knowledge pertaining to planning leg islation and administrative procedures was intentionally wielded by the media and local residents to challenge the legitimacy of demolition. Concerning the problem framing related to the preservation of historic buildings, local knowledge was actively harnessed and deliberately employed by residents and the media to underscore the historical and cultural significance of the neighbourhood. Regarding problem framing centred on resistance to resettlement and eviction, residents intentionally incorporated institutional knowledge when composing and submitting petition letters. These three lines of problem framing, grounded in deliberative knowledge utilisation, significantly impact power dynamics and facilitate the incremental transition towards collaborative planning, which emerges as a gradual process marked by experimentation and the resolution of conflicts.

1 Introduction

Urban regeneration in post-reform China has provided fertile ground for the shift towards communicative and collaborative planning. This shift is driven by the increasing complexity and influence of various actors involved in urban regeneration. Collaborative planning, deeply rooted in Habermas's concept of communicative rationality, has been advocated since the 1980s and is closely connected to the political theory of deliberative democracy (Healey 2003; Gualini 2015). However, collaborative planning has faced considerable criticism due to its contextual limitations, particularly its tendency to overlook the contextual factors that may hinder its successful implementation. Since the late 1990s, the concept of collaborative planning has gained traction in China, both in theoretical and practical contexts. Within this framework, the concept of 'authoritarian deliberation' holds significant importance for comprehending collaborative planning practices and theoretical development in the Chinese context (Lin 2023; Tang 2015). The practice of urban regeneration has encountered resistance from local communities and an escalation of conflicts since the I99os. The local government has grappled with the formidable challenge of handling this resistance and has found it increasingly difficult to execute and manage urban regeneration projects independently. In this context, collaborative planning has emerged as an alternative approach to address the aforementioned challenges. It has helped the government gain a deeper understanding of the issues at hand and discover solutions to resolve conflicts, ultimately enhancing its legitimacy (Lin Citation2023). In a certain sense, conflicts can be viewed as the starting points for the emergence of collaborative planning in China. In essence, collaborative planning serves as a tool to manage conflicts and complex problems, rather than merely pursuing the normative planning goal of achieving democracy and equality (Lin 2023). Collaborative planning is actively employe d and supported by the government to better comprehend the complex issues and strategically address the impediments hindering the progress of urban regeneration within the Chinese context.

In this context, the shift towards collaborative planning in the realm of urban regeneration in China has garnered the attention of numerous scholars (Lin Citation2023; Cao et al. Citation2021). Particularly since 2015, there has been a discernible transformation in both urban regeneration policy and practice in China, transitioning from large-scale, movement-style urban redevelopment to small-scale, incremental micro-regeneration. This shift towards micro-regeneration has amplified the prominence and dynamism of collaborative planning in the Chinese context (Li et al. Citation2020; Wang et al. Citation2022). For instance, young scholars and planners from universities have introduced innovative urban planning methods in community regeneration planning. They have effectively employed collaborative workshops as a means to foster more inclusive decision-making processes (Li et al. Citation2020). Notably, it has been observed that social media serves as an influential platform for collaborative planning in China (Lin Citation2023; Cao, Wang Citation2019; Yao et al. Citation2021). Social media and various online forums have been strategically harnessed to stimulate public debates and even challenge existing power dynamics (Tan, Altrock Citation2016). A newly formed alliance, comprised of mobilised citizens and the central government, with a priority on maintaining social stability, has countered the pro-growth coalition. This alliance has facilitated a shift in governance towards a more inclusive mode (Zhang et al. Citation2016). Nevertheless, it is important to note that collaborative planning in the Chinese context typically remains government-led or government-steered, which differs significantly from the Western perspective of collaborative planning deeply rooted in communicative deliberative democracy. Therefore, the primary objective of this article is to delve into the micro-level processes that contribute to the emergence of collaborative planning in practical urban regeneration in China. The central research questions can be framed as follows: what enables more inclusive decision-making and collaborative planning in urban regeneration in China?

Conflicts in urban planning typically stem from changes in land use that reflect incompatible interests among various stakeholders (von der Dunk et al. Citation2011; Gualini Citation2015). Dealing with conflicts is the focus of both collaborative planning and agonistic planning. Collaborative planning primarily concentrates on conflicts of interest among various stakeholders, while agonistic planning centres on ontological conflicts related to hegemonic and marginalised discourse and the related identity-forming processes of inclusion and exclusion (Mäntysalo et al. Citation2023). In agonistic planning, conflicts are viewed as productive and necessary for bringing about institutional and social change (Dahrendorf 1961). The approach of agonistic planning fully accepts and even encourages conflicts. In contrast, collaborative planning deals with conflicts of interest among different stakeholders through mutual negotiation and active communication. The mechanism of conflict resolution is a key factor that distinguishes collaborative planning from agonistic planning. Stepanova et al. (Citation2020: 265) define conflict resolution as a “dynamic iterative process where different stakeholders (not only courts and mediators) initiate attempts to solve the conflict formally and informally in search of ‘better’ management solutions.” Agonistic planning does not necessarily aim for consensus-building but rather seeks alternative methods for decision-making in the presence of persistent conflicts. However, the lack of discussion about conflict resolution in the agonistic planning approach makes it unable to provide practical guidance for implementing agonistic planning (Kuehn Citation2021). In contrast to agonistic planning, conflict resolution is the primary goal of collaborative planning, and conflict serves as a catalyst that promotes collaboration (Innes, Booher Citation2015). In collaborative planning, conflict resolution pertains to the means and processes by which actors with conflicting interests strive to reach a consensus. Starting from this point, the agonistic approach criticises consensus-oriented collaborative planning as a potentially rhetorical or idealised model, suggesting that in practice, temporary ‘conflictual consensus’ tends to emerge due to the ongoing disputes, and this consensus may not truly represent the agreement of all affected actors (Mouffe Citation2013; He, Wagenaar Citation2018). In response, drawing on pragmatism, Giddensian structural theory, and complexity theory, collaborative planning has developed further by later concentrating on situational consensus or situational planning processes, thus reaching a better conceptual balance between deliberative ideals and practical difficulties (Forester Citation2013; Mäntysalo et al. Citation2023). In this way, the idea of conflictual consensus as a temporary solution has also been acknowledged and even integrated into the later development of situational agreement in collaborative planning. As conflict resolution serves as a catalyst and approach to promote more deliberative interactions among various stakeholders and advance collaborative planning, this paper aims to take a closer look at how conflict resolution processes facilitate the shift towards collaborative planning in the Chinese context.

In the Western context, planning conflicts frequently become visible and prominent during the formally regulated process of public consultation or participation. However, in the authoritarian governance framework of urban regeneration in China, the establishment of public participation institutions is still in its early stages, and public participation often primarily serves as a symbolic administrative procedure to acquire legitimacy (Wu Citation2015). Meanwhile, many conflicts arise throughout the entire urban regeneration process, yet a significant number of them remain unapparent and unacknowledged in official documents by decision-makers in China. Most research attention has been directed towards problem framing documented in the final planning document, which is officially announced. However, the series of conflicts that emerge during the on-the-ground planning formation and adjustment processes are frequently ignored and underestimated by policymakers and urban researchers. In a sense, many of these less visible, undocumented conflicts are of utmost importance for gaining a better understanding of the micro-level processes of planning and the institutional dilemmas associated with urban regeneration practices and policy innovation mechanisms in the Chinese context. The development and resolution of conflicts represent something of a ‘black box’ that warrants and demands closer scrutiny and investigation. By shedding light on the micro-level processes of conflict resolution, it facilitates a better understanding of how collaborative planning is implemented in the Chinese context of ‘authoritarian deliberation’, enriching the scholarly debate in the field of collaborative planning.

Since the 1980s, scholars have increasingly focused on the role of knowledge in urban planning (Davoudi Citation2015; Owens, Cowell Citation2011). Although the utilisation of knowledge has been extensively discussed in the theoretical domain (Alexander Citation2008; Rydin Citation2007; Davoudi Citation2015), there is still a scarcity of applied empirical analyses of knowledge utilisation within the field of planning (Stepanova et al. Citation2020). Stepanova and Saldert (Citation2022) contend that knowledge integration can be discerned in the context of planning conflicts, making the underlying knowledge utilisation factors of conflicts more apparent. Similarly, Innes and Booher (Citation2015) argued that the role of knowledge utilisation is critical and significant during the conflict resolution processes. This, in turn, is valuable for enhancing conflict resolution by moving towards more sustainable, long-term-oriented solutions. A clearer and more profound understanding of how knowledge facilitates collaborative deliberation is instrumental in helping planners find solutions to conflicts through the deliberate utilisation of knowledge. Building upon Stepanova and Saldert’s (2022) focus on knowledge utilisation in planning conflict resolution, this paper aims to delve into the finely tuned and micro-level mechanisms through which knowledge utilisation, especially, contributes to both the development and resolution of conflicts.

As noted by He and Warren (Citation2011), extensive deliberative and participatory practices have emerged within the authoritarian framework of China. Scholarly attention has also grown around numerous informal and unstructured deliberative initiatives in the country (Tang Citation2015). Deliberation is defined as “debate and discussion aimed at producing reasonable, well-informed opinions in which participants are willing to revise preferences in light of discussion, new information, and claims” (Chambers Citation2003: 309). Similarly, He and Warren (Citation2011) define deliberation as a mode of communication in which participants offer and respond to the substance of claims, reasons, and diverse perspectives in ways that generate persuasion-based influence. Viewed from this perspective, knowledge utilisation in conflict resolution can be understood as a deliberative practice aimed at producing reasonable and persuasive problem and strategy framing for consensus-building. Therefore, this paper aims to examine the micro-level processes of deliberative knowledge utilisation in problem framing, for a deeper and more specific understanding of conflict evolution and resolution. In urban studies, conflict and framing are often studied separately, yet they are also closely interconnected. The interrelations between conflict and framing will be elaborated in more detail in the following section.

The remainder of the paper is divided into six sections. First, it offers a research review of collaborative planning and its application in China within the authoritarian Chinese context. Additionally, it reviews scholarly findings and discussions regarding the interrelations between collaborative planning, conflict resolution, and problem framing. It also revisits research on conflict resolution and deliberative knowledge utilisation. Second, it explains the analytical framework encompassing knowledge typologies and the framing analysis approach that serves as a guide for the analysis in the empirical case study. In the fourth section, the paper provides the background of the selected case study and explains the methods used for data collection. Following that, it explores how problem framing, based on deliberative knowledge utilisation, shapes the process of urban regeneration in practice and how the shift towards incremental collaborative planning occurs. The sixth section discusses how conflict-driven deliberative knowledge utilisation promotes more inclusive decision-making and collaborative planning within the Chinese context. Finally, the findings on how knowledge utilisation influences problem and strategy framing in conflict resolution and facilitates collaborative planning within the Chinese authoritarian context will be discussed.

2 Theoretical and conceptual f ramework

2.1 Collaborative planning in the authoritarian Chinese context

Collaborative planning, originally rooted and advocated in the Western context, has faced criticism due to its contextual limitations, such as a lack of consideration for its practical implementation within authoritarian settings. As mentioned earlier, collaborative planning has been promoted to address conflicts and complex problems in urban regeneration, with Chinese planners and researchers showing a heightened focus on its functional benefits, particularly in consensus-building. However, there has been insufficient reflection on the adaptability and limitations of the Western-conceived idea of collaborative planning within the context of ‘authoritarian deliberation’ in China (He, Warren Citation2011). Regarding the authoritarian deliberation context in China, the governance of urban regeneration has been described and summarised in various ways. It has been characterised as entrepreneurialism (Zhu 2011; Duckett Citation1998; Duckett Citation2001; Bercht Citation2013), a ‘socialist pro-growth coalition’ (Zhang Citation2002) with a strong local government collaborating with non-public sectors while excluding the community, or ‘local state corporatism’ (Qi 1995: 1132), where local governments treat enterprises within their administrative jurisdiction as components of a larger corporate entity. Wu et al. (Citation2022) have labelled the governance mode of urban regeneration in China as ‘state entrepreneurialism’. In the authoritarian Chinese context, governance arrangements remain largely under the control of the party-state, and institutional procedures regulating interactions and negotiations are gradually evolving. This evolution is dependent on the availability of specific resources and capabilities that allow actors to access, participate in negotiations, and ultimately influence urban regeneration processes. What is crucial in the Chinese case is the fact that due to the exploratory nature of urban regeneration, a policy field that has not yet established stable institutional settings, there is no assurance of a mature arrangement of supportive resources, procedures, routines, and best practice experience. Additionally, it has been suggested that Confucian culture and concepts play a significant role in understanding how collaborative planning operates in the Chinese context. They may influence power dynamics and prioritise principles of collaborative planning that favour harmony over equality (He, Wagenaar Citation2018; Lin Citation2023). Examining the respective practice of collaborative planning within an Asian context such as China can help enrich and respond to the aforementioned criticisms of collaborative planning.

Additionally, collaborative planning has faced criticism due to its constraints and limitations in the selection of representative citizens involved in the collaborative consensus-building processes. The agonistic planning theorists have argued that the Habermasian consensus, based on the assumptions of deliberative democracy, primarily exists in the theoretical domain, while temporary ‘conflictual consensus’ remain factual in practice (Mouffe Citation2013). This scenario is characterised by domination by strong actors such as the government and developers, with limited input from civil society. Starting from this criticism, the collaborative planning approach has been developed further by looking for contextual opportunities in actual planning processes, i.e. situational agreements to deal with conflicting interests (Forester Citation2013; Innes, Booher Citation2010). The pragmatic manner thus enables the further development of collaborative planning in the theoretical and practical domains. However, there remain critics of collaborative planning regarding its deficit in ignoring the institutional dimensions and lack of engagement with institutional reconfiguration, by mainly focusing on situational planning within existing institutional arrangements (Mäntysalo et al. Citation2023).

In contrast, the agonistic planning approach has faced criticism for its failure to adequately consider the existing ambivalences in the political practice of planning, primarily due to its strong bias towards a positive view of conflict (Kuehn Citation2021). In other words, it falls short of addressing the challenges of finding a practical planning approach that can capture the dynamic interplay between institutional reform and stabilising policy actions (Mäntysalo et al. Citation2023). To embrace agonism in practical planning, Pløger (Citation2023) proposed the concept of a ‘sketch’, which refers to a thematic plan made of points and lines capable of changing on the move, as an appropriate and pragmatic approach for working in a way that is decisional, temporary, and unfinished. He argued that the agonistic approach of a sketch could transform the planning process from one based on path dependency with fixed plans or final decisions into a series of aggregated open decisions that can adapt to emerging discontinuities and disagreements. In a certain sense, the mutual complement and fusion of agonistic planning and collaborative planning help develop a planning approach that can effectively address planning conflicts, exploring opportunities for situational agreements while remaining responsive to marginalised dissensus (Hillier 2003; Pløger Citation2023; Mäntysalo et al. Citation2023). Moreover, an agonistic planning approach aims to bring conflicts and informal deliberation to the surface and engage with them openly. It provides valuable insights into how conflicts and power dynamics influence urban regeneration in an authoritarian system. In line with this perspective, this paper places particular emphasis on a critical reflection of the processes and outcomes of ongoing consensus-building by examining the often-overlooked or undocumented conflicts that arise during collaborative planning in the Chinese context. Besides, it examines the dilemmas and challenges of the conventional fixed-plan-oriented approach regarding emergent conflicts, drawing on empirical studies of a controversial case called Enning Road in Guangzhou.

2.2 Collaborative planning, conflict resolution and problem framing

These conflicts in urban planning serve as both the impetus and catalyst for consensus-oriented collaborative planning, making conflict resolution an explicit objective of the planning process (Innes, Booher Citation2010). Collaborative planning involves various efforts for conflict resolution, which aim to establish a shared understanding and consensus-building through methods such as discussions, collaborative dialogues, and formal and informal participatory exercises (Ross Citation2009). Consequently, conflicts are an integral part of the collaborative process. It is argued that although conflicts may initially appear as challenging and unwelcome, they can also be viewed as potential sources of innovation (Christmann Citation2019). Healey (Citation1999) posited that planning conflicts serve as ‘creative tensions’. Conflicts can be beneficial when, during the process, actors with differing perspectives converge on shared frames of reference (Schruijer, Vansina Citation2006). From this perspective, consensus-building and collective decision-making to achieve shared goals become central features and goals of collaborative planning (Healey Citation2003; Booher, Innes 2010). Collaborative planning is instrumental in generating more sophisticated and flexible solutions that balance and coordinate conflicting interests among multiple actors (Kuehn Citation2021; Booher, Innes 2010).

Conflict and framing are often researched separately, but they are also closely intertwined. Framing, as eloquently described by Rein and Schön (Citation1993), is a multifaceted process of selecting, organising, interpreting, and understanding the complexity of reality. In the realm of conflict, the clash of perspectives often stems from different problem and strategy framings. The interactive and communicative nature of problem and strategy framing is a vital aspect of conflict resolution. In the course of consensus-seeking deliberation and social interaction, new ideas for framing problems and strategies emerge (Benford Citation1997). Framing serves as windows into the development and mechanics of conflicts, shedding light on what might otherwise remain hidden. Framing thus becomes both a sense-making tool and an approach, enabling us to comprehend the multitude of discourses and the origins of conflicting viewpoints in a given field (Goffman Citation1974; Zimmermann et al. Citation2022). Problem framing is not just about describing what exists; it is also about making normative statements regarding what is desirable. In a certain sense, problem framing illuminates the complexities of conflicts and is instrumental in steering the path towards resolution. In essence, framing is both a compass for understanding conflict resolution and a tool for shaping it. Brand and Gaffikin (2007) argue that collaborative planning plays a key role in facilitating negotiative problem definition and consensus-building. Hence, this paper seeks to analyse the development and resolution of conflicts, with a closer examination of the interactions and development of various problem framings and their role in fostering situational consensus.

2.3 Conflict resolution and deliberative knowledge utilisation

A growing number of scholars has recognised the significance of knowledge utilisation in conflict resolution and collaborative planning. Notably, it has been acknowledged that knowledge integration is a critical factor contributing to conflict resolution and consensus building (Innes, Booher Citation2010; Stepanova 2014; Rydin Citation2007; Albrechts Citation2012). Some studies have recognised knowledge integration and collaborative knowledge production as important mechanisms for conflict resolution and consensus building (Peltonen, Sairinen 2010). Knowledge integration is considered both a process and an outcome of conflict resolution (Stepanova et al. Citation2020). Furthermore, it has been observed that the utilisation of knowledge in conflict resolution also fosters mutual learning processes and the development of a shared understanding among various actors (Stepanova et al. Citation2020; Westberg, Polk 2016). However, the practical aspects of knowledge utilisation as a critical approach and mechanism for conflict resolution have been under-investigated (Stepanova et al. Citation2020). In the literature on collaborative planning, the interactions and relationships among the state, market, and community are typically analysed in terms of their ability to pool and mobilise various resources, such as infrastructure, capital, property, land, and social capital in networks. While the knowledge dimension has received increasing attention from scholars in the collaborative planning literature, its importance remains somewhat overlooked. Burrage (Citation2009) argues that knowledge has become a fluid resource, akin to a form of ‘currency’, but it is often neglected in urban regeneration, unlike the more visibly tangible physical resources. Similarly, the knowledge and ideas used to justify decision-making methods and planning practices are frequently overlooked (Van Herzele Citation2004). Concerning collaborative planning in China, existing studies tend to focus more on the outcomes and participatory tools of collaborative planning, rather than on the internal processes and mechanisms of knowledge utilisation and conflict resolution, which are crucial for understanding collaborative planning in the Chinese context.

Deliberative knowledge utilisation enables actors to derive meaning from available relevant knowledge and strategically employ it in relatively open negotiation processes. This strategic utilisation of knowledge aims to lead to successful action and achieve more inclusive and integrative decision-making that takes the actors’ interests into account. The specific approaches within this context depend on the roles of the actors, the types of knowledge they can access, and the developmental context that influences the range of possibilities within which they can operate. As noted by Fly vbjerg (1998), actors may choose to acquire knowledge for strategic reasons, sometimes even through acquisition or purchase. Atkinson et al. (2010) posit that knowledge exchange is intertwined with various forms of communication, such as mass media, closed expert communities, professional consulting, or public deliberation. While this observation might seem somewhat counterintuitive within the Chinese political system, it has nevertheless been confirmed by all the cases examined in this fluid and evolving policy field (Li et al. Citation2020; Yao et al. Citation2021). The process of deliberative knowledge utilisation may be challenging to pinpoint, but it can still be captured through the examination of argumentation and various discourses related to problem and strategy framing (Stepanova et al. Citation2020). In this context, this paper seeks to explore how deliberative knowledge utilisation contributes to conflict resolution in urban regeneration within the Chinese context.

Deliberative knowledge utilisation is deeply intertwined with the process of problem framing, which in turn influences how conflicts are approached and resolved. Problem framing, as Hoppe (Citation2010) and Heinelt et al. (Citation2010) suggest, is shaped by both the ‘is’ and ‘ought’ dimensions. The ‘is’ dimension refers to the existing knowledge available for understanding the problem. The certainty of this knowledge can vary, affecting how problems are framed. On the other hand, the ‘ought’ dimension encompasses norms, values, principles, ideals, and interests that play a role in defining the problem. The level of ambivalence or ambiguity regarding these normative issues further affects problem framing. The availability and certainty of knowledge also impact the framing of problems. Hoppe (Citation2010) categorises problems into unstructured, moderately structured, and structured based on the certainty of knowledge and the ambivalence of values. This categorisation illustrates how problem framing is influenced by the interplay between knowledge and values.

Additionally, the relationship between deliberative knowledge utilisation, problem framing and power dynamics, is crucial in conflict resolution. Knowledge is not neutral and is influenced by power and values. Weiler’s concept of the ‘politics of knowledge’ highlights the intricate relationships between knowledge and power in urban politics. Power dynamics affect which knowledge is considered relevant and whose knowledge is included or excluded in urban regeneration practices. Government officials often prioritise ‘expert knowledge’ over local knowledge, as noted by Stone et al. (Citation2001) and Hordijk and Baud (2006). This preference can lead to the marginalisation of local knowledge and residents’ problem framing in decision-making processes, creating imbalances in power dynamics. In practice, imbalances in power dynamics can influence the utilisation of various types of knowledge in problem framing by different stakeholders. Conversely, the deliberative utilisation of knowledge in strategic problem framing can impact power relations, further shaping the resolution of conflicts. Understanding this intricate interplay is essential for effective conflict resolution and collaborative planning. Therefore, this research seeks to explore the relationships between deliberative knowledge utilisation in problem framing and power dynamics to shed light on how they influence conflict resolution in urban regeneration in China.

3 Analytical f ramework: knowledge typologies and f raming

3.1 Three types of knowledge

It is also recognised that knowledge is multifaceted (Sandercock Citation1998) due to its various sources and forms. Negev and Teschner (Citation2013) have suggested that stakeholders possess and utilise multiple types of knowledge concurrently. Knowledge sharing or transfer helps to expand its assets and value (Gibney Citation2011; Healey Citation2013). Making distinctions among different types of knowledge and comprehending the diverse forms of knowledge is an essential step when using knowledge as an analytical approach to examine the interactions among various actors within the intricate web of urban regeneration. Concerning categories of knowledge, distinctions can be drawn between codified and tacit knowledge, verbal and non-verbal knowledge, propositional and non-propositional knowledge, as well as knowledge based on skills and abilities (Abel 2008). Moreover, there has been substantial discussion about the concepts of ‘explicit’ and ‘implicit knowledge’, or ‘codified’ and ‘tacit knowledge’ (Polanyi Citation1966). Alexander (Citation2008) identified three kinds of knowledge, including systematic-scientific knowledge, performative knowledge, and appreciative knowledge. Matthiesen (Citation2005) introduced the notion of ‘knowledgescapes’ to distinguish between eight interrelated and overlapping forms of knowledge. However, it can be quite challenging to identify knowledge types based on ‘knowledgescapes’ in empirical research. For instance, many planners struggle to specify the type or nature of knowledge they employ (Khakee et al. Citation2000). Building upon the categories proposed by Matthiesen, Getimis (Citation2012) further differentiated three forms of knowledge: (1) scientific/professional/expert knowledge, (2) steering/institutional knowledge, and (3) local/every day/milieu knowledge. Similarly, Edelenbos et al. (2011) identified three types of knowledge: scientific, stakeholder, and bureaucratic or administrative knowledge. Based on the knowledge types defined by Getimis (Citation2012) and Edelenbos et al. (2011), we will classify the knowledge used in urban regeneration into three types in this study: technical knowledge, institutional knowledge, and local knowledge (Tan et al. 2019). Distinguishing features of these three types of knowledge can be analysed from three aspects: (1) origin (where it comes from), (2) validity (why people trust it), and (3) recognition (how evident it is in discourse).

Technical knowledge used in urban regeneration primarily finds expression in the field of planning. The application of technical knowledge in urban regeneration typically takes on explicit and codified forms, such as planning documents. Planning is an integral aspect of urban regeneration, as no redevelopment project can be carried out without planning approval in China. Technical knowledge is considered valid, often being perceived as expert or professional knowledge. Planners, who carry this technical knowledge, hold a crucial role in the urban regeneration process. Within the critical theory paradigm, knowledge is viewed as value-laden and constitutive of interests (Hordijk, Baud 2006). Hordijk and Baud (2006) argue that powerful actors can reinforce their claims by utilising ‘expert knowledge’ and may exclude the interests of less powerful actors by disregarding practice-based and traditional knowledge or by contesting the source and legitimacy of such knowledge. The role of technical knowledge in conflict resolution hinges on how specific technical knowledge is integrated as expertise and becomes authoritative knowledge concerning particular conflicts. Researchers have also observed that certain preferred technical knowledge is reinforced while alternatives are marginalised. Understanding which technical knowledge is chosen as expertise in conflict resolution and how it becomes part of the knowledge assembly process requires further investigation.

According to Matthiesen (Citation2005: 7), institutional knowledge pertains to “knowledge about the systemic and functional as well as formal and informal logics of organisations and institutional arrangements.” This knowledge encompasses both codified or explicit knowledge, primarily reflected in formal rules (North Citation1991), such as constitutions, laws, property rights, and tacit or implicit knowledge, referring to informal restraints (North Citation1991), such as sanctions, taboos, customs, traditions, and codes of conduct. The utilisation of institutional knowledge becomes evident through discursive interactions among various actors. Matthiesen (Citation2005: 7) asserted that “institutional knowledge is distributed highly unequal between different actor networks and societal strata.” Consequently, actors possessing valid institutional knowledge and resource-based capacity can apply it, while marginalised actors with only outdated institutional knowledge may attempt to “adjust these shortcomings via ‘soft’ personal knowledge networks and informal institutions.”

Antweiler (Citation1998) referred to ‘local knowledge’ or ‘indigenous knowledge’, which consists of factual knowledge, skills, and capabilities, most of which are empirically grounded. Headlam and Hincks (2010) also discovered that local communities are often unable to apply their local knowledge in practice, relying on ‘experts’ to translate their knowledge into action. Healey (Citation1998) observed that policy ‘experts’ and ‘professionals’ possess their own form of ‘local knowledge’, acquired through interactions with various individuals and organisations across different sectors. It has been noted that failures in conflict resolution often result from insufficiently integrating local knowledge or incorporating incorrect local knowledge (Trujillo et al. Citation2008).

3.2 Framing analysis: knowledge-based problem and strategy framing

The framework of framing includes two dimensions: cognitive and interactional (Aukes et al. Citation2017). In terms of the cognitive aspect, framing can be viewed as an instrument for making meaning from knowledge utilisation and creating various storylines. In regard to the interactional aspect, framing involves consensus building among actors through shared meaning-making during interactions (Dewulf, Bouwen Citation2012). Framing can thus be considered an instrumental approach to meaning-making, closely intertwined with the deliberative utilisation of knowledge. Specific knowledge is strategically selected and used in problem framing. In line with the interactive perspective of framing, framing is referred to as co-constructions that are negotiated, contested, and transformed during social interactions (Goffman Citation1974; Benford Citation1997; Zimmermann et al. Citation2022). While deliberative knowledge utilisation has been recognised as a pivotal facilitator in problem framing and strategy framing within the context of conflict resolution, there is a need for further investigation into how it facilitates problem and strategy framing and how these processes contribute to consensus-building in the Chinese context.

In the real world, knowledge-based problem framing often takes the form of narratives and arguments. In other words, knowledge utilisation in framing can be implicitly embedded in discourse. Methodologically, problem framing can be detected and traced through discursive outputs such as journal reports, petition letters, planning documents, interviews, etc. The study aims to gain a better understanding of the root causes of conflicts and delve into the processes of conflict resolution.

The interplay between framing and relational dynamics plays a critical role in influencing the success of collaborative planning (Vandenbussche et al. Citation2017). Framing analysis has been increasingly utilised by deliberative scholars (Mendonça, Simões Citation2022). Investigating the micro-mechanisms of problem and strategy framing through a knowledge-based lens helps us understand how problem-framing-oriented discourse and debates are generated, interact with each other, and influence decision-making in the practical context of urban regeneration in China. Hence, framing analysis as an analytical approach is applied in this paper to map the problem and strategy framing, demonstrating how problem framing is shaped by deliberative knowledge utilisation and discursively constructed. It also highlights how shared strategy framing and consensus-building are achieved.

4 Case selection and data collection

Enning Road in Guangzhou has been chosen as the empirical case study to provide a comprehensive and insightful examination of complex knowledge dynamics in conflict resolution within the field of urban regeneration in the Chinese context. The case of Enning Road has garnered significant scholarly attention due to its substantial relevance for debates on multifaceted issues, including cultural preservation, just resettlement, institutional innovation, and more (Tan, Altrock Citation2016; Yao et al. Citation2021; Wang et al. Citation2022). It serves as a microcosm of the larger debates and controversies surrounding conflict resolution in urban regeneration in Guangzhou and the broader region. The extended duration of the project from 2006 to 2021 and the evolution of planning schemes due to continuous problem framing and emerging strategies underscore its significance. Moreover, the active engagement of various stakeholders, including the media, scholars, NGOs, and residents, reflects the deliberative utilisation of multiple forms of knowledge in problem framing and strategy framing for more inclusive and participatory approaches. The Enning Road case is emblematic of the issues that continue to challenge urban regeneration in China and offers a means to better understand how the shift towards collaborative planning occurs in the Chinese context.

To gather comprehensive data and insights, meticulous fieldwork was conducted from 2011 to 2018, involving a wide range of stakeholders. Thirty-five semi-structured interviews were carried out with local officials, residents, planners, journalists, and NGO members, providing invaluable perspectives. Furthermore, the author’s close relationships with Enning Road community residents facilitated both participatory and non-participatory observations, resulting in a wealth of in-situ materials. This material includes petition letters, photographs, governmental announcements, and internal notes, shedding light on the multifaceted aspects of the Enning Road regeneration project. Long-term and in-depth ethnographic studies are essential for capturing the ways in which knowledge is utilised in problem framing.

5 Deliberative knowledge utilisation in conflict resolution of Enning Road

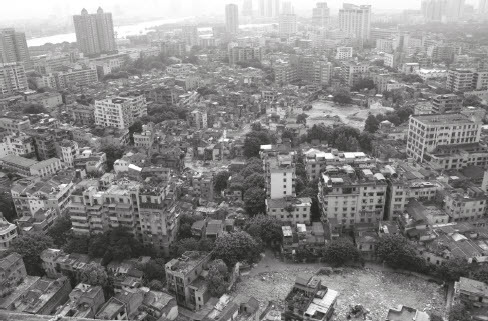

The Enning Road project endured for a lengthy 15-year period, commencing in 2006 and concluding at the end of 2021. During this protracted period, three distinct versions of detailed planning were formulated by three different planning institutes from 2006 to 2011. The first plan was established in 2006 when the government officially initiated the redevelopment project (see ). Subsequently, a second plan was crafted in 2007 after the first plan was rejected in the internal decision-making process (see ). A common feature in both the initial plans was the proposed demolition of most buildings to facilitate the relocation of all residents within the project site. Both plans were built around the concept of having two north-south roads cutting through the area, following the regulatory plan of Guangzhou in 2007. This approach inevitably led to the complete destruction of the historical community and the urban fabric. The third version of the plan was established in 2009 (see ). In this iteration, the strategy shifted away from demolishing the main part and reconstructing with high-rise buildings to a plan with significantly lower density. This significant change placed greater emphasis on preserving historical buildings. It ultimately received approval from the municipal planning committee and was published in 2011.

Fig. 1: The first plan. (Source: Experimental Dilapidated Housing Renovation Plan of Guangzhou, 2006)

Fig. 3: The third plan. (Source: Urban Regeneration Planning of Enning Road in Liwan District, 2011)

It is important to note that these first two plans reflected the prevalent urban redevelopment strategy widely applied in central Guangzhou since the 1980s, primarily driven by municipal urban infrastructure development, especially the construction of motorways. The earliest official demolition permit for the Enning Road redevelopment program was issued by the government in September 2007, and official demolition work began in 2008. The scope of demolition was defined and executed in accordance with the 2007 plan, even though this version of the plan had not received official approval or been made public. As per the redevelopment strategy promoted by the government in 2006, the municipal government was responsible for financial matters, while the district government managed land expropriation, compensation, and resettlement. Initially, redevelopment funding was obtained through bank loans secured by the Municipal Land Development Center, with intended repayment through the potential income generated from later land transactions. The tasks of compensation mobilisation and relocation negotiations were over-seen by the Liwan District Unsafe Housing Re-development Project Office.

In 2006, the Guangzhou government formally announced the commencement of the Enning Road project under the banner of ‘re-development of unsafe housing’. This initial phase of large-scale resettlement and demolition has been conducted under the pretext of ‘redevelopment of unsafe housing’, without the presence of officially approved and publicised planning from 2006 to 2008. This served as the original catalyst for complex conflicts stemming from the demolition debate. Under such context, three lines of problem framing have emerged and revolved around different aspects: 1) the legitimacy of demolition and planning, 2) preservation of historic buildings, and 3) resistance to resettlement and eviction. In the following section, we will delve into these lines of problem framing and their respective strategy framing.

5.1 Problem framing on legitimacy of demolition and planning

The first two plans for the Enning Road project faced disapproval during internal decision-making because they resembled a property-focused redevelopment approach involving extensive demolition. This approach had already been heavily criticised in a previous controversial project called Liwan Square, drawing ire from scholars and reflections from planners. Recognising these issues, the government chose not to approve or make these plans public.

However, the government needed to sell the land in line with the original redevelopment strategy, so they initiated a compensation agreement and began evacuating residents. The demolition work started, partially following the second plan from 2007, even though it had not been published or approved at that time. This led to increased disputes over sudden demolition and greater resistance to resettlement within the first three years, which posed more challenges than the government had anticipated. As a result, they began developing a third plan, seeking a more acceptable alternative in this context.

When the third version of the plan was eventually published on 21 December 2009, over half of the households in the community had already signed compensation and relocation contracts, and a significant number of buildings had been demolished. To slow down and halt the demolition, the media began questioning the legitimacy of the planning process. In a 2009 news report titled ‘Planning of Enning Road Redevelopment Should Not Occur Secretly’ by the New Express, there was a call for the planning process to be made transparent to the public and to take public opinion into consideration.

Subsequently, doubts regarding the legitimacy of the demolition permit, particularly the argument that it would allow demolition without planning guidance, gained strength from scholars and local residents. In March 2010, 220 local residents wrote a letter to the People’s Congress and the standing committee member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference of Guangzhou municipality, contending that “such large-scale demolition without a detailed plan violates our current national urban reconstruction and demolition management law”. An expert in historical and cultural preservation also voiced criticism regarding the government’s choice to commence demolition before completing the planning process, deeming it indicative of an immature decision-making approach. This perspective is documented in a report titled ‘Permanent Pain Caused by Demolition Before Planning’, as published by the Yangcheng Evening News.

The dispute primarily revolved around whether a detailed plan was necessary for issuing the demolition permit, and this debate pressured the government to release the plan as soon as possible. In response, the government initiated and published the third version of the plan. Simultaneously, they were compelled to make the first two plans public to clarify the evolving planning ideas that had been taking place behind the scenes.

During this period, some residents blamed the planner of the third plan for the large-scale demolition, as they were unaware that demolition prior to 2009 had been carried out based on the second version of the plan. The residents framed the issue this way due to the lack of transparency in the planning processes, which left them with insufficient information.

5.2 Problem framing on preservation of historic buildings

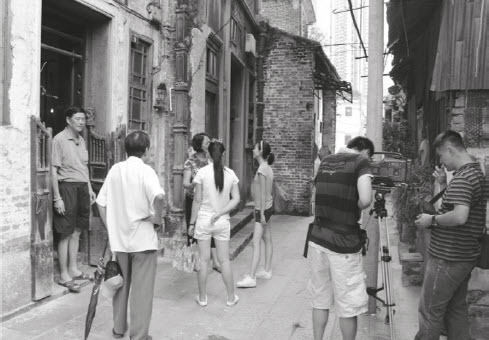

In May 2007, for the first time, the Liwan district government published the boundaries of the demolition area, represented by red lines, covering an area of 11.37 hectares. This development attracted widespread media attention due to the discovery of numerous locally renowned and well-preserved unlisted historical buildings within the designated demolition area. One particularly controversial report revolved around the potential demolition of Enning Qilou Street. However, it was later announced that Qilou Street would be preserved, which garnered significant public interest. The problem framing before the official publication of plans has been focused on the inappropriate destruction of potentially valuable historic buildings. Under such context, many stories about these historical buildings, fuelled by local and technical knowledge, came to the forefront through media coverage. Local residents shared additional stories about notable buildings, including former residences of famous Canton drama artists and Bruce Lee, during the demolition phase (see ). A professor specialising in traditional architecture played a significant role in evaluating old traditional residential structures in Enning Road, while local residents gathered information about valuable old buildings and shared their memories.

Fig. 4: Interview of residents by journalists in 2011. (Source: Focus Group) : Enning Road area in demolition in 2011. (Source: Focus Group)

In 2008, the government published the Historical Building Preservation Plan for Enning Road and made several adjustments to the demolition list and scope between 2007 and 2014. The most significant change was observed in the third version of the plan, which placed a greater emphasis on cultural preservation. Media reports played a vital role in drawing public attention and awareness to the cultural significance of the community. As a result, the third plan placed a much greater emphasis on preserving historical buildings, leading to significant adjustments in the demolition plan when compared to the first two versions. The primary objective was to retain a more substantial number of buildings within the area. In December 2009, the third plan was unveiled to seek public input.

During this period, a letter was published in a newspaper, authored by five residents and endorsed by 183 others, titled ‘Protect Real Xiguan, No Learning from Shanghai Xintiandi’. In this letter, they argued that the government’s intentions were to displace them and construct a commercial street in an artificial antique style, all under the guise of redeveloping the old town and preserving historical culture. Furthermore, in the previously mentioned letter, signed by 220 residents in 2010, the residents criticised the project, asserting that “the project’s true aim is purely commercial and tourism development, cloaked in the guise of serving the public interest”. In this manner, the problem framing related to the authenticity and intent of historic preservation within the third plan was established.

Moreover, the cultural value of Enning Road received official recognition when it was included in the Famous Historical and Cultural City Preservation Plan of Guangzhou City. In 2012, when the draft plan was released, Enning Road was initially omitted from the list of historical and cultural communities. In response, 78 local residents from the Enning Road area signed and submitted an open letter titled ‘Suggestions on Including Enning Road as a Historical and Cultural Community in 2012’. Additionally, the Focus GroupFootnote1 NGO also advocated for similar suggestions. Eventually, in 2012, Enning Road was officially recognised as the 23rd historical and cultural community in Guangzhou.

In 2012, the municipal government’s decision to construct the Canton Opera Museum on Enning Road was serendipitous. Driven by the new mayor’s vision for a museum, officials scouted land throughout Guangzhou. Remarkably, they stumbled upon available land following the area’s demolition, making it a suitable site. Local knowledge that has been deliberatively utilised to emphasise the historical significance of Enning Road, particularly its connection to renowned Cantonese opera artists, was used to justify the museum’s location.

5.3 Problem framing on resistance to resettlement and eviction

The implementation of the Enning Road redevelopment project encountered far more challenges than initially anticipated, primarily due to continuous resistance from residents against evacuation and demolition (see ). In 2009, a letter titled ‘Opinions and Strong Requirements from Relocated Households in Enning Road Redevelopment Project’ was penned by residents. This letter expressed complaints about the compensation offered and requested an increase in the monetary compensation standard so that they could afford to purchase similar flats in nearby areas. Simultaneously, numerous reports highlighting compensation conflicts were featured in newspapers and online sources. Initially, in 2007 and 2008, the compensation strategy for private owners involved relocating to flats in the outskirts of Guangzhou. However, in 2009, the government announced that an additional 600 flats near Enning Road would be provided as relocation housing.

Meanwhile, the problem framing by the residents that challenged the official problem framing of ‘unsafe housing’ has emerged as well. For example, there was a seven-story building originally constructed as a factory in 1995, later privatised, and renovated into residential flats in 2002. In response, a letter was authored and signed by 80 households residing in the building, which was sent to the National People’s Congress. This letter asserted that the “demolition of the building should be cancelled as it violates the recently published Law of Property Rights” and argued that their building is safe housing without any quality problems. This proved effective, as in 2009, it was officially announced that the building would not be demolished.

Throughout this process, the media continued to play a pivotal role. In the early stages, the residents were uncertain about which legal avenues to pursue to protect their property rights. In response, journalists consulted with lawyers and recommended that the residents appeal to the National People’s Congress. Moreover, members of the Focus Group with expertise in law provided guidance and assistance to local residents when they sought legal recourse for property rights disputes. Residents were highly motivated to seek higher compensation, and they sought attention and support through various avenues including problem framing that challenged the legitimacy of the demolition planning, engaged in debates about public interest in the project scheme, addressed compensation issues related to property, and scrutinised the use of ‘unsafe housing’ as a justification for launching the project.

5.4 Incremental turn towards collaborative planning

The extended challenges encountered during the problem framing and implementation phases of the Enning Road project provided valuable lessons regarding top-down planning approaches, which had faced substantial resistance. These experiences ultimately led to a shift towards collaborative planning as an alternative approach to conflict resolution by the government. However, this transition to collaborative planning did not occur abruptly; rather, it was the result of ongoing bottom-up, self-organised efforts that had aimed at increasing public participation in planning decision-making since 2006.

During the public planning consultation process, residents and NGOs actively participated in planning discussions and sought dialogues with planners. Residents even attempted personal contact with the planner responsible for the third plan, although these efforts were unsuccessful for various reasons. The Focus Group conducted a comprehensive five-month investigation within the community, producing two reports: ‘Suggestions on the Regeneration Plan of Enning Road’ and ‘Social Assessment Report of the Redevelopment Project of Enning Road’. These reports were later submitted to the municipal planning department. The Focus Group also attempted to create a community regeneration plan, although it faced various challenges, and this did not come to fruition. Furthermore, the group organised an exhibition called ‘Listening to Enning’ and a round-table meeting that brought together scholars and residents in 2012.

As demolition and evictions continued from 2008, the physical environment in the neighbourhood deteriorated, leading to various issues such as accidental fires, flooding on rainy days, piles of rubbish, and increased burglary. One journalist attempted to speak with a member of the People’s Congress, who later suggested that the mayor personally visit the Enning Road area. This visit resulted in the establishment of the Advisory Group of the Enning Road Project in October 2010. The group included experts in urban planning and traditional architecture preservation. This could be seen as the preliminary effort and the initial turning point towards collaborative planning.

The conflicts related to compensation posed significant challenges to the Enning Road regeneration project, resulting in a slowdown in the demolition of buildings and hindering the original strategy of raising funds through land transactions. From 2007 to 2010, the Guangzhou government made several attempts to identify potential developers. However, these efforts proved challenging as only a few developers showed interest. The complex negotiations regarding relocation and the preservation of historical buildings had resulted in fragmented land parcels that did not seem to offer sufficient market value to attract developers. As the environment in the area continued to deteriorate during the demolition, the local government faced the difficult task of determining how to proceed with the Enning Road regeneration given the limited financial resources available. They needed to find a viable solution to this challenge.

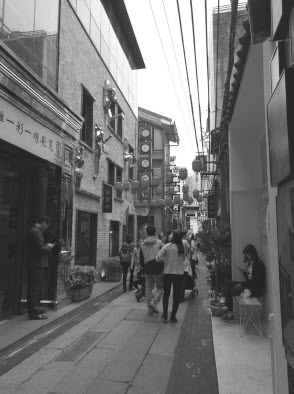

Under such circumstances, the district government initiated a micro-regeneration project in the western part of the Enning Road redevelopment area in 2016. The real estate company Vanke secured the bid to oversee the renovation and management of the Yongqingfang area, with a focus on revitalising 7200 square meters of vacant buildings (see ). The ‘Guidelines on Micro Regeneration in Yongqingfang’ were released, emphasising a strategy in which the district government played a dominant role, enterprises were responsible for implementation, and residents actively participated in the decision-making process. To facilitate this collaborative approach, a platform called ‘co-making’ was established to promote collective and inclusive decision-making. This represented a new direction in the regeneration efforts for the Enning Road area, aimed at finding solutions to the financial and implementation challenges that had emerged.

During the implementation phase, conflicts arose between the company and local residents. For instance, residents lodged complaints that the developers had obstructed their windows following the renovation of old buildings, negatively impacting their living conditions and daily lives. In 2017, four representative residents penned a letter, co-signed by 60 residents, and submitted it to the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress in Guangzhou. This letter conveyed their concerns about the issues stemming from the micro-regeneration project. The strategy of problem framing and articulating residents’ concerns, which had been employed from 2006 to 2016, endured. The initial phase of the Yongqingfang regeneration, taking place from 2016 to 2018, achieved a compromise and consensus. This phase allowed residents to remain in their homes while preserving the traditional buildings, thereby transforming Enning Road into an attractive destination for commercial and leisure entertainment. The Bruce Lee Museum was established at the former residence of Bruce Lee on Enning Road. The second phase of renovation and adaptive use commenced in 2018 and was completed at the end of 2021. The establishment of the co-making platform within the Yongqingfang regeneration eventually evolved into an institutionalised planning approach, incorporated into relevant legislation for urban regeneration in Guangzhou. Building on the experiences of problem and strategy framing in Enning Road, micro-regeneration was initially promoted in the ‘Methods of Urban Regeneration’ published in 2015.

6 Collaborative planning driven by deliberative knowledge utilisation in problem f raming

Regarding the problem framing on the legitimacy of demolition and planning, institutional knowledge related to planning legislation and administrative procedures was deliberately employed by the media and local residents to challenge the legitimacy of demolition. As a consensus was gradually reached on the legitimacy of demolition, this problem framing also garnered criticism from scholars and prompted the government to reflect on the pitfalls of hastily conducting demolition without careful planning and negotiation. These instances of problem framing exerted considerable pressure on the government to initiate the creation of a third version of the planning that prioritised preservation. This process involved publicising the three versions of the plans, officially amending the regulatory plan in accordance with the third approved plans and conducting public consultations to gather feedback on the third plan. It also led to the establishment of official co-making platforms to promote more inclusive collaborative planning in the Yongqingfang micro-regeneration project.

Regarding the problem framing on preservation of historic buildings, local knowledge was actively harnessed and deliberately utilised by residents and the media to emphasise the historical and cultural significance of the neighbourhood. This problem framing was articulated and conveyed through media reports, petition letters from residents published in the media, an NGO’s report based on fieldwork and interactions with residents, and the interactions between residents and a professor who specialised in traditional architecture preservation. The deliberate use of local knowledge played a crucial role in generating persuasive problem framing discourse that gradually altered the perspectives of the government and the public regarding the preservation value of the Enning Road neighbourhood. This consensus on prioritising preservation led to several revisions of the government’s demolition plans and the compilation of a preservation list. Moreover, the local narratives about the residences of famous Cantonese artists and Bruce Lee eventually gave rise to the development of the Bruce Lee Museum and a Cantonese Opera venue on Enning Road. In response to the growing emphasis on preservation and to address this aspect of problem framing, the government also made a deliberate effort to integrate technical knowledge on preservation. For instance, a professor specialising in historic building preservation was entrusted to conduct on-site investigations to further adjust the scope of demolition and compile the preservation list. Furthermore, a consultant group was established in 2010, featuring both experts and residents, to promote more inclusive decision-making.

Regarding the problem framing on resistance to resettlement and eviction, residents deliberately employed institutional knowledge when composing and submitting petition letters. The legal knowledge associated with the Law of Property issued in 2007 and administrative proceedings empowered residents to frame their concerns in a legal context, which helped to substantiate their rights to remain in the area and simultaneously advocate for improved compensation and resettlement arrangements. In fact, the desire to secure better compensation and the right to remain can be regarded as the fundamental driving force behind the residents’ active and deliberative engagement in all three streams of problem framing. According to interviewees, the media encouraged residents to believe that framing the issue solely as dissatisfaction with compensation is not convincing enough to gain public support. Instead, framing the issue in terms of legitimacy and the preservation of historic buildings, which are closely linked to the public interest, was more likely to garner support and help legitimise their pursuit of higher compensation or the right to remain in the neighbourhood.

Fuelled by all three lines of problem framing and their corresponding strategy framing, the transition towards collaborative planning unfolded gradually. The series of bottom-up participatory initiatives and top-down communication experiments slowly shaped the approach and tools of collaborative planning in the Enning Road context. Enning Road has emerged as a well-known and influential project, signifying a shift in the urban regeneration landscape of Guangzhou. This shift marks a transition from large-scale property-driven redevelopment to a more meticulous approach focused on small-scale micro-regeneration.

7 Conclusions

Hence, the shift towards collaborative planning did not occur overnight. It was a gradual process marked by experimentation and conflict resolution. Faced with financial pressures stemming from the failure of the land auction that was initially proposed and increasing criticism from local residents and social media, the local government found it increasingly difficult to proceed with urban regeneration solely through top-down planning, especially with limited community participation. In this context, collaborative planning emerged as a means to collectively address these conflicts. Its promotion in the Urban Regeneration Method of Guangzhou in 2015 signified that experimental practices and conflict resolution had contributed to the institutionalisation of decision-making procedures.

Throughout the earlier period of top-down planning, which marked the inception of the project, there was a noticeable lack of a formal institutional framework for various stakeholders to articulate their distinct problem framings and concerns. The three streams of problem framing, facilitated by deliberative knowledge utilisation, were expressed through a discourse coalition comprising media, local residents, NGO members, and scholars. The media, in particular, played a central role as a knowledge broker, helping convey institutional and technical knowledge to residents to effectively frame and publicise their concerns. This empowered residents to enhance their ability to express themselves, render their problem framing more persuasive, garner public support, and even initiate dialogues with decision-makers, albeit often indirectly. It did so by exerting pressure on the local government to respond and adopt a more inclusive planning approach.

In the Enning Road case, space and opportunities for expressing disputes emerged primarily through media reports and petition letters. These practices were enabled by a discourse coalition formed by grassroots residents, NGOs, social media actors, and some scholars. However, it is important to note that these practices were tolerated as long as they did not pose a direct challenge to the stability or legitimacy of the regime, within the context of an authoritarian deliberative system. These conflicts, stemming from various types of problem framing, raised concerns among local government officials about the potential for community-level disputes to escalate and threaten ‘social stability’. As a result, they took action to mediate and manage these conflicts responsively.

From this starting point, the Enning Road redevelopment case can serve as a prime example to illustrate how deliberative knowledge utilisation affects the dynamics between various actors and influences the process of plan development. Problem framing can be considered an instrument for making meaning out of knowledge utilisation. Enning Road, being the first comprehensive redevelopment project in the old town of Guangzhou, demonstrates how conflicts can drive the shift towards collaborative planning within the authoritarian context of China. This is accomplished through an examination of how conflicts were addressed and how grassroots actors improved their access to decision-making through knowledge-based framing of issues over time. Power structures can either empower or constrain the utilisation of knowledge. However, this case illustrates that the strategic and deliberative utilisation of knowledge as an invisible resource can also influence the existing power relations among various actors. Nevertheless, under the framework of ‘authoritarian deliberation’ and its imbalanced power structure, collaborative planning remains highly regulated and directed by the government and professionals who hold more decision-making power. They decide to what extent the problem framing and strategy framing of local residents and the public are incorporated into the decision-making process.

Building on our analysis, we assert that deliberative knowledge utilisation serves as a tool for conflict resolution by stimulating negotiation processes and reshaping power relations among diverse actors. What is crucial in the Chinese context is that, given the exploratory nature of urban regeneration and its lack of a stable institutional framework, one cannot rely on a mature arrangement of supportive resources, procedures, routines, and best practices. Our case studies demonstrate that there is room for bottom-up strategic intervention in decision-making processes. A virtuous and integrated, yet deliberative utilisation of multiple forms of knowledge can facilitate the shift towards collaborative planning in this context. Further investigation and exploration of deliberative knowledge utilisation in practical planning fields are warranted and valuable for better comprehending the resilience and challenges of collaborative planning within an authoritarian context.

Acknowledgement

This work was funded by the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No. 2021A1515110276), Guangzhou Philosophy and Social Sciences (No. 2020GZYB54), and Guangdong Philosophy and Social Sciences (No. GD19YYS07).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Xiaohong Tan

Xiaohong Tan, Dr.-Ing., is a Researcher at the School of Architecture and Urban Planning at Guangdong University of Technology. Her research interests are centred around urban regeneration, urban governance, public participation, social learning, and informal housing in China. Presently, she is involved in researching social innovation, artistic intervention, and heritage preservation in the Chinese context.

Uwe Altrock

Uwe Altrock, Dr.-Ing., is a Professor of Urban Regeneration and Planning Theory at the University of Kassel, School of Architecture, Urban and Landscape Planning, Institute for Urban Development. His research interests are urban regeneration, urban governance, planning theory, megacities, and suburban development. Currently, he is the head of the DFG-funded research group FOR2425 Urban expansion in times of re-urbanization – new suburbanism?

Xiaowei Liang

Xiaowei Liang, PhD, is a Lecturer at the School of Culture Tourism and Geography, Guangdong University of Finance and Economics in China. She has pursued research on urban regeneration as well as urban planning and urban governance. Currently, she is engaged in research on land policies, the urban redevelopment scheme and land development rights within the context of China’s urban-rural dual-track land system.

Notes

1 In March 2010, a group of students from various universities in Guangzhou, along with a few societal volunteers, established the ‘Academic Focus Group of Enning Road’ (referred to as the ‘Focus Group’ hereafter). The group members come from diverse academic backgrounds, including urban planning, architecture, sociology, anthropology, economics, geography, journalism, law, art, and more.

References

- Antweiler, C. (1998): Local knowledge and local knowing: an Anthropological analysis of contested “cultural products” in the context of development. Anthropos, 36, pp. 469–494.

- Aukes, E.; Lulofs, K.; Bressers, H. (2017): Framing mechanisms: the interpretive policy entrepreneur’s toolbox. Critical Policy Studies, DOI: 10.1080/19460171.2017.1314219.

- Albrechts, L. (2012): Reframing strategic spatial planning by using a coproduction perspective. Planning Theory, 12 (1), pp. 46–63. doi: 10.1177/1473095212452722

- Alexander, E. R. (2008): The role of knowledge in planning. Planning Theory, 7 (2), pp. 207–210. doi: 10.1177/1473095208090435

- Bercht, A. L. (2013): Glurbanization of the Chinese megacity Guangzhou – image-building and city development through entrepreneurial governance. Geographica Helvetica, 68 (2), pp. 129–138. doi: 10.5194/gh-68-129-2013

- Burrage, H. (2009): Knowledge, the new currency in regeneration. Journal of Urban Regeneration and Renewal, 3, pp. 120–127.

- Brand, R.; Gaffinkin, F. (2007): Collaborative planning in an uncollaborative world. Planning Theory, 6 (3), pp. 282–313. doi: 10.1177/1473095207082036

- Benford, R. D. (1997): An insider’s critique of the social movement framing perspective. Sociological Inquiry, 67, pp. 409–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-682X.1997.tb00445.x

- Cao, C.; Wang, S. F. (2019): Rethinking the role of planners under media influence. Planner, 3, pp. 69–74 (in Chinese).

- Cao, K.; Zhu, J.; Zheng, L. (2021): The “collaborative planning turn” in China: exploring three decades of diffusion, interpretation and reception in Chinese planning. Cities, 117, 103210. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2021.103210

- Chambers, S. (2003): Deliberative democratic theory. Annual Review of Political Science, 6 (1), pp. 307–326. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.6.121901.085538

- Christmann, G. B. (2019): Introduction: struggling with innovations. Social innovations and conflicts in urban development and planning. European Planning Studies, DOI: 10.1080/09654313.2019.1639396.

- Davoudi, S. (2015): Planning as practice of knowing. Planning Theory, 14 (3), pp. 316–331. doi: 10.1177/1473095215575919

- Dewulf, A.; Bouwen, R. (2012): Issue Framing in Conversations for Change: Discursive Interaction Strategies for “Doing Differences”. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 48 (2), pp. 168–193; DOI: 10.1177/0021886312438858.

- Davidoff, P. (1965): Advocacy and pluralism in planning. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 31, pp. 331–338. doi: 10.1080/01944366508978187

- Duckett, J. (1998): The entrepreneurial state in China: real estate and commerce departments in reforms Era Tianjin. London, UK: Routledge.

- Duckett, J. (2001): Bureaucrats in business, Chinese-style: The lessons of market reform and state entrepreneurialism in the People’s Republic of China. World Development, 29 (1), pp. 23–37. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00083-8

- Flyvbjerg, B. (1998): Rationality & Power: Democracy in Practice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Forester, J. (2013): On the theory and practice of critical pragmatism: Deliberative practice and creative negotiations. Planning Theory. 12 (1), pp. 5–22; https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095212448750.

- Getimis, P. (2012): Comparing Spatial Planning Systems and Planning Cultures in Europe. The Need for a Multi-scalar Approach. Planning Practice and Research, 27 (1), pp.25–40. doi: 10.1080/02697459.2012.659520

- Gibney, J. (2011): Knowledge in a “Shared and Interdependent World”: Implications for a Progressive Leadership of Cities and Regions. European Planning Studies, 19, pp. 613–627. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2011.548474

- Goffman, J. (1974): Frame analysis. Harvard University Press.

- Gualini, E. (2015): Conflict in the city: democratic, emancipatory – and transformative? In search of the political in planning conflicts. In: Gualini, E. (ed.), Planning and Conflict: Critical Perspectives on Contentious Urban Developments. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 3–36

- Healey, P. (1998): Building institutional capacity through collaborative approaches to urban planning. Environment and Planning A, 30 (9), pp. 1531–1546. doi: 10.1068/a301531

- Healey, P. (1999): Institutionalist analysis, communicative planning, and shaping places. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 19 (2), pp. 111–121. doi: 10.1177/0739456X9901900201

- Healey, P. (2003): Collaborative planning in perspective. Planning Theory, 2 (2), pp.101–123 doi: 10.1177/14730952030022002

- Healey, P. (2013): Circuits of Knowledge and Techniques: The Transnational Flow of Planning Ideas and Practices. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37 (5), pp.1510–1526. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12044

- Headlam, N.; Stephen, H. (2010): Reflecting on the role of social innovation in urban policy. Journal of Urban Regeneration and Renewal, 4 (2), pp.168–179.

- He, B. G.; Warren, M. E. (2011): Authoritarian deliberation: the deliberative turn in Chinese political development. Perspectives on Politics, 9 (2), pp. 269–289. doi: 10.1017/S1537592711000892

- He, B. G.; Wagenaar, H. (2018): Authoritarian deliberation revisited. Japanese Journal of Political Science, 19, pp. 622–629. doi: 10.1017/S1468109918000257

- Hordijk, M.; Isa, B. (2006): The role of research and knowledge generation in collective action and urban governance: How can researchers act as catalysts? Habitat International, 30 (3), pp. 668–689. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2005.04.002

- Hoppe, R. (2010): The governance of problems: Puzzling, powering, participation. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.