ABSTRACT

The late 19th and early 20th centuries were a period when artistic endeavours, aimed at expressing a national identity, were thriving in Hungary. The Jewish minority of Budapest also found it important to be present in public spaces. A couple of years after the emancipation of Hungarian Jews, the first statues of Jewish personalities appeared on the streets of Budapest. Who were these statues dedicated to? Who were the artists commissioned, and who paid for them? What were the invisible texts beyond reading the statues as texts? What happened to the public monuments during the Second World War? This paper aims to respond to these questions as a part of a research project mapping Jewish interventions in public art in Budapest.

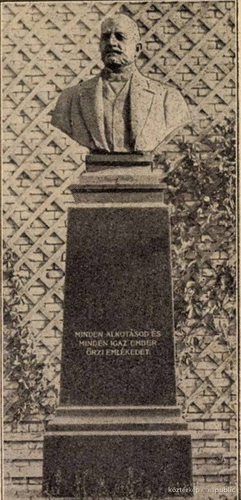

On 26 November 1924, a life-size bust of Manfréd Weiss (1857–1922), one of Hungary’s richest men and entrepreneurs was erected in front of the office building of his former war factory. A choir sang during the commemoration ceremony, followed by a speech by the factory’s most senior official. Neither the nationalist, revisionist prayer-like poem, the Hungarian Credo, which became famous during the Horthy era and which advocated the restoration of the territory of the Kingdom of Hungary to its pre-World War I size, nor the inaugural speech gave any hint that Weiss was Jewish.Footnote1 Alajos Stróbl (1856–1926),Footnote2 a fashionable Hungarian sculptor who introduced public portrait sculpture in Budapest with his monumental Romantic statues of great Hungarian artists and politicians, depicted the famous industrialist in a suit and a bow tie. The inscription on the pedestal reads: ‘All your creations and all your travels preserve your memory’.Footnote3 () This description was a false promise, as the statue no longer stands in front of the factory building. It is not clear what happened to it: Tibor Bárány, a journalist and researcher into the history of Csepel (the southern island in the Danube), where the Weiss factory was located, says that a member of the anti-Semitic Arrow Cross party tore it down,Footnote4 while other sources say that it was destroyed by the Germans during the Second World War.Footnote5 The Weiss factory, which produced most of the Hungarian army’s military equipment, was taken over by the Germans after the German occupation on 19 March 1944, then by the communist state after 1945, and privatisation after 1989 culminated in the closure of most of the factory’s production.

Illustration 1. Manfréd Weiss’ Statue. Köztérkép, https://www.kozterkep.hu/40520/weiss-manfred-mellszobor#vetito=400777.

Weiss’s statue was one of a handful of monuments depicting famous Jewish personalities of the era. This article focuses on how the emerging wealthy Jewish upper class, with seemingly unlimited financial resources and social standing, attempted to intervene in the secular public spaces of Budapest during and after the ‘Golden Era’ of Jewish emancipation in Hungary (1867–1918). This period is also known as the age of ‘double emancipation’, as it opened opportunities for assimilated Jewish women to leave the patriarchal household and pursue a career to earn their living. It is no coincidence that the first female statue in Budapest depicting a figure who was neither a member of the Habsburg dynasty nor a Christian saint was that of a successful Jewish woman, Johanna Bischitz.Footnote6 While Budapest is by no means unique in not having many statues of women in public spaces, it is certainly unique that the first statues of women were commissioned by the city’s Jewish citizens.Footnote7

While attempting to uncover the circumstances of the creation of the monuments, the article aims to decipher the motives of the commissioners. To do this, we use a theoretical framework often applied in urban studies: reading the city and urban landscapes as texts. By deconstructing the statues as texts, a range of cultural, social, and political meanings emerge, which in turn contribute to an understanding of how the commissioners intended to write a Jewish text into the city. To achieve this, we seek answers to the following questions: To whom were these statues dedicated? What role did they play in the Jewish community, and why were they chosen for commemoration? Who were the artists commissioned, and who were the patrons? Where were the statues placed, and how and why were these sites chosen? What is the gender politics of these statues?

We are also interested in the history of the statues, which reveals a striking contradiction between the intentions of the commissioners and the readings of the statues by the observers. While the Jewish community had the means and opportunity to erect statues at the fin-de-siècle, this trend changed in the late 1930s, and by the end of the Second World War, most of the monuments discussed in this article had been demolished or had disappeared from their original locations. However, due to the limitations of the length of this article and, more importantly, the lack of sources, we can only touch upon these events to illustrate how the readings of certain urban settings changed over time, and how they are the objects of constant interaction between their readers.

The methodological problems of the research are presented first, followed by the larger context of Jewish emancipation in Hungary. We then present the statues and how their readings as texts overwrite previous literature claiming the invisibility of Jews in Budapest’s public spaces. In this article we use the adjective ‘Jewish’ in the sense of the identity of the depicted personalities and the commissioning communities the majority of the Hungarian Jews considered themselves to be Jewish Hungarians whose only distinguishing feature was their religion.Footnote8

Methods

One might wrongly assume that there will be an inventory of Jewish-related monuments in Budapest by 2023. Sculpture in Hungary is not inventoried as it is in the open access database: Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland, 1851–1951.Footnote9 This article therefore required basic research, which was carried out at the Institute of Art History of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The Institute’s archives provided background information on several statues and memorials dedicated to Jewish personalities. The collection consists mainly of handwritten cards with references or newspaper cuttings. These were probably written by one or more art historians over time, and they were arranged by the Institute’s staff according to the surnames of the sculptors. As the cards of an artist are not arranged or indexed in any other way, the researcher has to go through them systematically to find details about particular statues.

The information on the cards is often fragmented or refers to outdated literature. Some cards quote from the issues of contemporary newspapers, which are not available in libraries. Thus, although the basic data on the statues can be obtained (sculptor, person represented, commissioner, date of unveiling, material, location), some equally important information may be missing: for example, the reception, the subsequent fate of the statues, whether they were removed and if so, by whom and when, the date of demolition, and so on. These gaps have been filled with information from literature and online sources.

Theoretical background: reading public interventions as texts

‘Preserving memory’, as the bust statue of Manfréd Weiss reads, is usually one of the main aims of public statues. However, neither Weiss’s statue nor the other statues erected to commemorate assimilated Jews in Budapest analysed in this article are still standing today. This sad fact would seem to prove Mary Gluck’s point:

The Jewish presence in Budapest was, and continues to be, an undeniable fact of life, documented by social, economic, and demographic evidence. Yet many Jews experienced, and continue to experience, their situation as if they were invisible.Footnote10

In Budapest, Jewish identity was manifested in urban spaces through various forms of art, such as literature: in the literary scene and pieces, typically places labelled as Jewish where, for example, the shopping streets of the 5th, and 6th districts, or coffee houses, as analysed by Szabó.Footnote11 Such places are considered ‘invisible’ for various reasons. The authors of A zsidó Budapest, for example, linked invisibility to the fact that most of the urban features created or built by Jews had no specific ‘Jewish’ features apart from the person of the architect; they were civic contributions and not defined by the denomination of the founder/architect.Footnote12 Mary Gluck developed this idea by linking the notion of invisibility to another kind of contribution: Jewish intellectual and cultural life, especially nightlife, which reflected ‘Jewish modernity’ and the lifestyle of the emerging middle class.Footnote13

In this article, we re-conceptualise the notion of ‘invisibility’ in comparison to Gluck’s use of it, which projects the majority viewpoint onto the minority while denying the minority agency. In contrast, we analyse the (in)visibility of the Jewish presence in Budapest through the community’s public monuments: in this context, (in)visibility is linked to complex socio-political processes, representativeness, and identity, and it is strongly connected to how different social groups perceived these monuments.

The 19th century was the era of building and imagining the nation-state, and the erection of monuments became an instrument of this process. This was a turning point in the shaping of the cityscape, as it brought with it the proliferation of public statues in public spaces, expressing the national idea rooted in the past; national heroes, writers and artists, and politicians were represented as symbols of perceived Hungarian identity. The collective memory of the city is thus manifested in monuments and statues: objects whose purpose is to remind the inhabitants of their common past and to construct a common belonging.

A ground-breaking framework for the analysis of monuments was Pierre Nora’s ‘lieu de memoire’ theory, which linked the community’s memorial heritage and shared past to symbolic elements displayed in the city.Footnote14 In this way, Nora argued, the city’s past becomes a constitutive element of the present through this symbolic level and sites of memory, creating a sense of continuity, and a sense of belonging. Through this process, the reflective level elevates the past to become part of the community’s identity.Footnote15 This approach to interventions in public space has two problems: first, it assumes that the nation (or, in this case, the population of a city) is a homogenous entity, and second, it assumes a unidirectional reading: those who erect the monuments have a message that is accepted by the viewers. However, when a locality is multi-ethnic or multi-religious, the nationalisation and historicisation of a city’s spaces is characterised by compromises, and monuments have different interpretations, depending on the identity of the viewer and the time of the viewing.

Urban studies, a discipline dedicated to the study and analysis of landscapes and urban spaces, offers a more flexible theoretical framework, a set of approaches rooted primarily in Walter Benjamin’s Das Passagen-Werk, a monumental work in which the philosopher and critical theorist examined the cities as texts. Benjamin read urban settings literally through metonymy and metaphor.Footnote16 His starting point was an analysis of street names in Paris, pointing out that despite the strict state control over street naming practices, the citizens of the city read these texts in their way,Footnote17 which provided a space for resistance to the overpowering state. In this way, the urban environment as text is not only an instrument of power, but also an object of interaction to be claimed by the inhabitants, and it ‘appears as an agency which has the power to organise or disrupt the socio-spatial order of the city’.Footnote18 Jazeel adds that the city as an analytical category is ‘an imaginative production’, a practice that facilitates its own creation.Footnote19

In analysing the city as ‘text’, researchers perceive it as a universe of condensed social and cultural meanings,Footnote20 ‘communicative devices’ that convey information,Footnote21 that can be deconstructed. How do we read sculptures as historical objects?Footnote22 To decipher these meanings, intertextuality must be considered: in the case of landscapes, this defines culture as a system of signification. Approaching urban settings in this way can unlock subtexts that lie beyond the visible text, and generate knowledge about the imaginative and cultural construction and structure of the city, as well as power relations and social life.Footnote23

In his monograph on reading and consumer culture, Gideon Reuveni aptly points out that reading is an autonomous, creative, and social activity, and that readers may read different messages into the same text, depending on their social background, identity, experiences, cultural, and political interests.Footnote24 The same applies to urban environments: depending on a variety of factors, city dwellers interpret them differently over time.

When we come to public monuments, we can perceive them as allegories: they act as symbols or icons that convey ‘morally charged stories’ about the commissioners, the person depicted, and the viewers, and as such, they express identity and political agendas, evoke different narratives and reflect social relations within a community.Footnote25 Readings of the monuments may differ from the intentions of the commissioners and the sculptor, which has sometimes led to the removal of these monuments.

In this article, we examine the cultural, social, and political circumstances of statues of Jewish personalities concerning gender politics. We also attempt to deconstruct them as texts to decipher the intentions of their commissioners: Jewish individuals, societies, or religious communities. At the same time, we want to follow the fate of these monuments and reflect on their reading by the local society, which explains their destruction: from the 1930s onwards, increasingly exclusionary, racist interpretations contributed not only to the symbolic but also to the physical invisibilisation of the statues.

The “Golden Age” with long shadows

Karl Lueger, the notoriously anti-Semitic mayor of Vienna called Budapest ‘Judapest’ because the Jews made up 23% of the population.Footnote26 Budapest was home to a thriving Jewish community at the turn of the 20th century: Jews had been granted legal equality in 1867, at the time of the establishment of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, which led to a period of prosperity and peace. Jewish youth entered higher education, and Jews participated in the intellectual, artistic, and economic spheres at a much higher rate than the Jewish population as a proportion of the inhabitants of the multi-ethnic Hungarian Kingdom.Footnote27 They made up 50% of the country’s merchants, 50% of its doctors, 29% of its lawyers, and 39% of its journalists. Jews took a lion’s share in the capitalist transformation and modernisation of the Hungarian economy. Most Jews in Budapest – the country’s leading community – were assimilated into Hungarian culture, spoke Hungarian, and had a Hungarian identity.Footnote28 The majority of them were mobile both socially and geographically.Footnote29

In 1868–1869, a Jewish Congress, a major gathering of representatives of the religious communities, was held in Pest to establish a nationwide organisational framework for these communities. However, instead of the desired unification, the participating religious leaders formed three major groups, thus causing a ‘schism’. Those who followed the progressive line (members of the so-called Neolog community), accepted the statutes of the Congress: they advocated emancipation, introduced Hungarian-language services, and dressed like non-Jews. The Orthodox decided to set up a separate, more conservative organisation for their communities. Finally, members of the smallest group, the Status Quo Ante communities, did not join either of the two main federations.Footnote30 90% of Budapest’s Jews belonged to the Neolog community.

According to Viktor Karády’s theory, to win over the country’s Jews to the national cause, an implicit social contract was concluded between them and the non-Jewish Hungarian nobility, which expected linguistic and cultural assimilation, and the support for Hungarian national independence in exchange for freedom of religion, protection, social mobility, the opportunity to participate in the economy, and the chance to be integrated into the new middle class.Footnote31 This process culminated with the Emancipation ActFootnote32 and the emancipation of the Jewish religion in 1895, when the Jewish faith was recognised as one of the major faiths in Hungary.Footnote33

The modern, assimilated Jewish middle class was the strongest in the capital. As soon as the legal conditions allowed, the Jewish presence among the intelligentsia and the bourgeoisie grew significantly. According to statistics, a quarter of the Jewish community worked as private clerks and officials, another quarter were self-employed, proprietors and another nine percent were civil servants.Footnote34 As Karády’s observations on the sociological characteristics of the Jewish community show, the vast majority of Jews living in Budapest were acculturated and secularised: in 1910, 90% of them spoke Hungarian; many of them Magyarised their names and/or converted to one of the main Christian religions, or married a non-Jew.Footnote35

Thus, this community was extraordinary both in its size and social composition, and although it could be considered the flagship of the Hungarian Jewish population, it is important to remember that the Budapest Jewish community had its own characteristics, such as its social status and the high proportion of assimilated individuals.

As early as 1859, a remarkable symbol of Hungarian Jewish pride in Budapest was inaugurated in the heart of the capital: in September, the Dohány street synagogue opened its doors to the community. Although the exterior of the building is Moorish style, the interior is basilica-like: the space is divided into three aisles, two pulpits were added to the sides, and an organ was placed above the Torah ark. The synagogue is thus a mixture of ‘Hungarian’ and ‘Jewish’ – reflecting both the contemporary identity of its congregantsFootnote36 and serving as a text written into the cityscape, ostentatiously drawing attention to the Jewish presence.Footnote37

The synagogue was not the only public intervention of Budapest’s Jews. Jews also sought to transform public spaces in Budapest. After the emancipation, known as the ‘Golden Age of the Jews’, as more and more Jewish personalities gained local, national, or even international recognition or reputation, and as the Jewish community enjoyed the tolerance of the majority society, statues and memorial plaques of Jewish artists, philanthropists, scientists, and successful businessmen appeared in the streets of the capital. These works of art were closely linked to the contemporary contexts of Romanticism, urban development, and ideologies such as nationalism and patriotism. The Jewish population of Budapest applied the text available at the time for writing themselves in the public space. However, those texts, namely the statues unlock subtexts that lie beyond the visible text and generate knowledge beyond their influence.

The erection of the memorials analysed in this article has an important temporal dimension. Anti-Semitism was present throughout this period,Footnote38 but in 1920, the first political antisemitic law in Europe, the numerus clausus,Footnote39 marked a turning point, and then, at the end of the 1930s, the major anti-Jewish laws meant that no statutes or plaques of Jews could be erected anymore. At that time, the control of public space meant the exclusion of Jews; this was complemented by the control of the financial resources available to those who could commission monuments and memorials.

Statues of Jewish personalities in Budapest

The 19th century saw a flourishing of the arts, which meant not only a multitude of new artistic genres but also new methods of bringing art into the public sphere. This was particularly evident in urban planning, which became an established practice at the beginning of the 20th century. The design and transformation of the urban environment were subject to plans based on scientific and artistic ideas of urban development. These efforts can be summed up as the triple aim of expansion, improvement, and embellishment.Footnote40 The latter included artistic efforts to decorate buildings, streets, squares, and other elements of the cityscape. This was facilitated by modern reproduction techniques and the mass production of sculptures.Footnote41

In Budapest, the so-called Szépítő Bizottság (Embellishment Committee) and later the Építészeti Bizottmány (Architectural Committee) were responsible for urban planning between 1808 and 1857.Footnote42 The efforts to transform and modernise the city in architectural and artistic terms were supported by the emerging institutional framework of the arts, which was initially based on artistic societies: organisations open to all, which facilitated the development of the arts both financially and morally.Footnote43 However, the most important institutions were founded only after the Austro-Hungarian Compromise: the Magyar Királyi Rajziskola (Hungarian Royal Drawing School) in 1871 and the Műcsarnok (Hall of Arts) in 1877. In addition to the former, various master classes were held by prominent artists, such as Alajos Stróbl who founded the master school of sculptors. These schools were merged in 1908 to form the Hungarian Royal College of Fine Arts.Footnote44

Under these circumstances, the number of sculptures placed in public spaces increased rapidly. Most of them depicted national heroes, royal figures (such as the statues in Heroes’ Square), generals, politicians, saints, and mythological or allegorical figures. The statues and plaques of Budapest’s Jewish community, however, were different (). The choice of figures commemorated mainly reflected the contribution of the Jews to Hungarian science, economy, and society. During our research, we found the following statues erected during this period:

Table 1. List of public statues and memorials in Budapest depicting Jews before the Shoah.

Interpretations and readings of the urban texts

In the following, we reconstruct the circumstances of the erection of the above monuments and their historical, social, and political context. The brief biographies of the depicted figures allow us to conclude the intentions and motivations of their patrons. For the sake of clarity and simplicity, we have grouped the statues according to the career of the person depicted or the nature of the contribution for which he or she was immortalised.

The public spaces occupied by these statues and plaques deserve special attention. A central regulation linking the erection of statues to the prior authorisation of the Minister of Education and Religious Affairs was only introduced in 1949.Footnote45 Before that, depending on the location, the monuments were approved by the Architectural Committee, the mayor, various ministries or other institutions.Footnote46 Given that most of the plaques and statues discussed in this article were placed on the walls of buildings or in (semi-)public spaces around the institutions that initiated their erection, we can assume that no special permissions were required; the commissioners only had to secure the financial means to pay the artists and place the monuments.

Four out of the seven monuments mentioned in the table were placed outside of the traditional Jewish district of Budapest (the 7th district). While this indicates the extent of assimilation and the intention of the Jewish community to be present in the cityscape, it must be noted that the statues were all associated with Jewish community institutions or organisations to which a Jewish individual made a significant contribution, such as the Weiss factory or the Stock Exchange. This may seem to diminish their significance, but we must also bear in mind that apart from sculptures depicting the members of royal families and personalities considered ‘national heroes’ (such as famous politicians, artists, etc.), very few fewer famous individuals had statues in centrally located spaces – most of them were placed near their former homes or institutions where they had worked.Footnote47

A building of parallel life stories

The building of 4 Holló Street in Budapest was built in 1835 according to the plans of the architect József Hild. In 1869, Antal Fochs, the leader of the Committee for Orphans of the Israelite Congregation, donated money to enable the Committee to buy the building and set up an orphanage for boys. The building was later extended with two wings and some of the apartments were rented out to cover the costs of the orphanage. Dr Sámuel Kohn and Dr Ignác Goldziher lived side by side in these apartments.Footnote48

Dr Sámuel Kohn (1841–1920) was the chief rabbi of the Pest Israelite Congregation, a historian, president of the Hungarian Jewish Literary Association, and a royal councilor. He supported the assimilation of Hungarian Jews, and he was the first to deliver a Hungarian sermon in the Dohány street synagogue, in 1866. As a result, he was invited to become the community’s rabbi. He was promoted to chief rabbi in 1905. He played a prominent role in the organisation of the 1868 Jewish Congress and the acculturation of the Jewish community in Pest. Franz Joseph I. honoured him with the title of Royal Councillor, then Court Councillor. Dr Kohn wrote several monographs on the history of the Hungarian Jews, the most important being A zsidók története Magyarországon a legrégibb időktől a mohácsi vészig [The history of the Jews in Hungary from the earliest times until the battle of Mohács].Footnote49

Dr Ignác Goldziher (1850–1921) was a world-renowned orientalist, university teacher, a member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, and the secretary of the Pest Israelite Congregation for 30 years. Under his teacher, Ármin Vámbéry, he learnt Arabic, Turkish and Persian languages and he carried out extensive research into Arabic and Jewish culture and Islamic religious philosophy. Although he was offered several positions at universities abroad, he never accepted them and stayed in Hungary.Footnote50

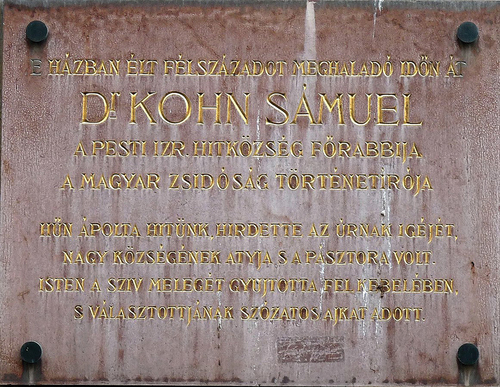

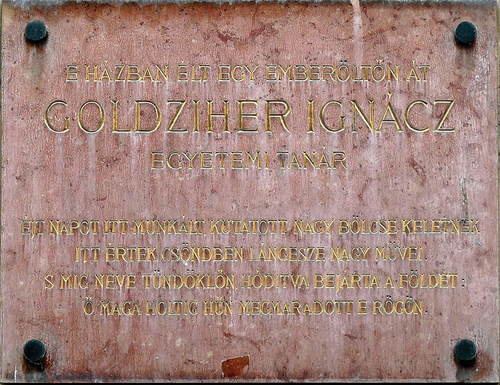

There are commemorative plaques on the façade of 4 Holló Street where they both lived. The plaques were commissioned by the Pest Israelite Congregation, and their inscriptions read:

Dr Sámuel Kohn, Chief Rabbi of the Pest Israelite Congregation, historian of Hungarian Jewry, lived in this house for more than half a century. He guarded our faith with devotion, he preached the Word of God, he was the father and shepherd of his great congregation, God kindled the warmth of the heart in his chest and provided his chosen one with eloquent lips. ()

Ignác Goldziher, a university teacher, lived in this house all his life. The great Orientalist worked and researched here day and night, and the great works of his genius matured here in silence. And while his name shone all over the world, he remained faithful to this land until his death. ()

These two outstanding scholars not only represented the Jewish contribution to Hungarian scientific life, but they were both fervent patriots and proud of their Hungarian nationality and Jewish identity. At the same time, they made significant contributions to the Jewish religious community and charity and social services. As such, their plaques as text carry the meaning of pride in certain community members who served both the Jewish minority and the non-Jewish majority. This can also be seen as a political agenda: to prove to the non-Jewish observer that Jews were invaluable members of society and faithful to the Hungarian national cause, which, in turn, underpins the importance and success of assimilation. Furthermore, of the individuals who received a monument in the period under discussion, only Sámuel Kohn was a religious leader which further proves that the extent of assimilation meant that the community felt the need to commemorate secular rather than spiritual achievements.

During the Second World War, the building was marked with a yellow star – a discriminatory sign indicating that only Jews could live in the house.Footnote51 The building is protected by the state as part of the cultural heritage and the memorial plaques are still on the wall.

Remarkable women

During the period of double emancipation, Jewish women were given unprecedented opportunities as Jews and as women.Footnote52 No longer confined to the home, they came to the fore in more unconventional roles. An outstanding example was Johanna Bischitz (née Fischer) (1827–1898), whose husband, Dávid Bischitz, was a wealthy merchant, and who gained recognition for her philanthropic activities. She was the founder and first president of the Pest Israelite Women’s Association for 25 years. In this context, she made a significant contribution to the development of a social welfare system: for example, the establishment of an orphanage for Jewish girls, soup kitchens (which served all the poor regardless of their religion), maternity hospitals, etc. She was a member of 35 charitable organisations and more than 10 women’s organisations. In 1879, she and her family were ennobled by Franz Joseph I.

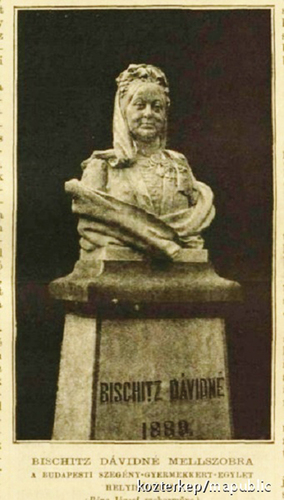

The statue of Johanna Bischitz was the first statue of a woman in the Hungarian capital and Hungary, followed by numerous statues of Sisi, Queen Elisabeth, the wife of Franz Joseph I. The bust, commissioned by the Pest Israelite Women’s Association and created by the famous Jewish sculptor, József Róna (1861–1939), was inaugurated at the end of 1889, when Mrs. Bischitz was still alive.Footnote53 The sculpture was originally unveiled in the hall of the Poor Children’s Garden Association of Budapest, a Jewish charity organisation, founded in 1879. The association helped orphans regardless of their religious background, and within a few years – thanks to Mrs. Bischitz’s activity – the number of donors supporting the association grew to more than a thousand. At the time, they were providing shelter and education for 250 children.Footnote54 Károly Szász, a Calvinist bishop gave a speech at the solemn inauguration ceremony. ()

Illustration 4. Johanna Bischitz’s statue. Köztérkép, https://www.kozterkep.hu/9787/bischitz-davidne-mellszobra#vetito=137374.

In 1894, the orphanage moved to another building: 32 Akácfa Street, where the statue was placed in a special niche built for this purpose in the gateway.Footnote55 A few decades later it was moved again, and today it is part of the collection of the Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives. Only the pedestal with the inscription ‘Mrs. Dávid Bischitz, 1889’, remained in the niche. It is unclear what happened to the bust, when, and who removed it. Historian Viktor Cseh speculates that it was taken to the Jewish Museum after the Second World War as part of the post-war salvage since the pedestal remained in its place: he believes that if anti-Semites had taken away the bust, they would have broken the pedestal as well.Footnote56 The sculpture is not mentioned in (Liber’s Citation1934) book on the public statues of Budapest,Footnote57 either because it was placed in the gateway or because it had been removed by then. Zsuzsanna Toronyi, director of the Jewish Museum, said that she did not know when the statue was brought to the museum, as there was no record of it.Footnote58

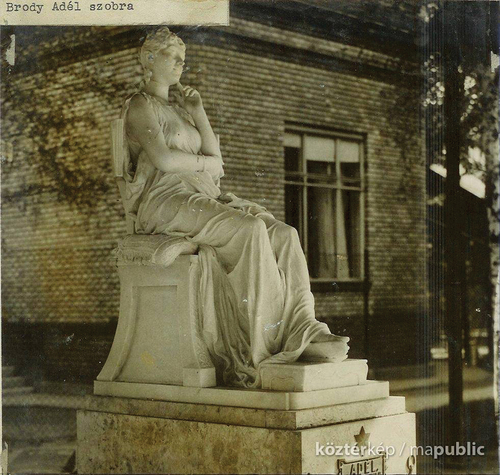

The other statue of a woman immortalised Adél Bródy (née Stern, 1847–1893), the wife of journalist and publisher Zsigmond Bródy. Zsigmond Bródy founded and financed the Israelite Children’s Hospital (or Bródy Adél Children’s Hospital) and named it after his wife in her memory. Built between 1895 and 1896,Footnote59 this modern hospital – the first one in the capital to specialise in paediatrics – accepted patients from all congregations. The hospital building was designed by the architect Vilmos FreundFootnote60 and it was located next to the Israelite Hospital (later the Weiss Alice Maternity Ward was built next to it). After the war, all the hospital buildings were nationalised.

The statue of Adél Bródy, depicting her in a contemplative seated position, was placed in the sanctuary of the hospital. The marble statue was one of the last works of the famous Austrian artist Viktor Oskar Tilgner. In 1932, the Jewish community, which was responsible for the upkeep of the hospital, moved the sculpture to the garden. It is not known what happened to it afterwards – it was probably destroyed during the Second World WarFootnote61 and is now lost. ()

Illustration 5. Adél Bródy’s statue. Köztérkép, https://www.kozterkep.hu/47704/brody-adel#vetito=530397.

The two women became well-known for their charity work and this was the main reason for their immortalisation. However, the origin of the statues and the artistic solutions are different. The bust of Johanna Bischitz was commissioned by the Women’s Association, and while it remained semi-public and seemed to have been created for the inner circle of the Jewish community (even the sculptor was Jewish!), the fact that it was unveiled by a Calvinist bishop and placed in the grounds of an interreligious orphanage suggests that the association wanted to emphasise that Mrs. Bischitz (and Jewish charities in general) helped the Jewish and non-Jewish poor alike. Through her achievements, they could prove that the needy could benefit from the accumulated Jewish capital regardless of their religion or origin – thus justifying the economic successes of the Budapest Jewish community.

This relatively modest statue was similar to those of famous men in that it did not include the body, thus keeping the focus on the face. This is complemented by a simple inscription on the pedestal, which emphasises the iconography and the fact that Mrs. Bischitz was a well-known figure at the time who did not need a lengthy introduction or laudation.

Adél Bródy’s sculpture, on the other hand, represents a typically feminine iconography: both her pose and the almost transparent, thin garment that covers her body, revealing her features, emphasise her femininity. Unlike Mrs. Bischitz’s, this statue celebrates – almost glorifies – a woman’s beauty (being placed in a sanctuary), while at the same time emphasising her connection with thought through her posture. There is nothing particularly ‘Jewish’ about Mrs. Bródy’s sculpture which is reinforced by the person of the sculptor and the fact that the hospital was open to all congregations. The commissioner’s intention was probably to commemorate his wife with a statue that would evoke respect and admiration in the observer. It took on new meanings as text when it was placed in the garden of the hospital, where it could be seen by everyone: there, it represented not only the woman whose name the hospital bore, but also the assimilated Jewish community, and Jewish philanthropy in helping sick children.

Finances that matter

The ‘Golden Age’ was almost synonymous with the rise of the powerful Weiss family. Manfréd Weiss (1857–1922) was one of the most important figures in the Hungarian industry: he was the founder of the steelwork factory in Csepel, one of the largest of its time. Originally, Weiss and his brother started their career by producing cans. They produced mainly for the army, and soon began to manufacture shells and bullets. In 1890, however, a cartridge exploded in the factory and the authorities banned production in the city. The Weiss brothers then moved their factory to Csepel (an island south of Budapest), an almost uninhabited place. As a result, the small village of Csepel began to grow: the factory and its favourable working conditions attracted workers. By 1914 it had become the largest military factory in Hungary and the second largest in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy.

Manfréd Weiss was also a philanthropist: he created exceptionally good conditions for his workers, and founded the Weiss Alice maternity ward, sanatoriums, and the National Alliance of Hungarian Industrialists. For his efforts, Franz Joseph I made him a baron.Footnote62

The bust of Weiss described in the introduction to this article had a number of intended meanings: first and foremost, it was a memorial to the founder of the factory. Secondly, and perhaps equally importantly, it was intended to remind the observers of a fatherly figure who cared for his workers. Neither the statue itself nor the description of the inauguration contain any ‘Jewish’ specificity – quite the opposite. We can therefore assume that the bust is a symbol of assimilated Jewry and Jewish entrepreneurship which contributed to the Hungarian economy.

The other Jewish industrialist family was the Kornfelds. Zsigmond Kornfeld (1852–1909) was born in Moravia and began working at the age of 14. He found jobs in local banks and soon began to rise through the ranks. As the deputy director of the Prague branch of Credit-Anstalt, he met Albert Rothschild who decided to send him to the Hungarian General Credit Bank in Budapest. Thus, at the age of 27, Kornfeld became a member of the bank’s board of directors and, from 1895, its managing director. He was a prominent figure in Hungarian financial and business life, helping to found several companies and serving as president of the Stock Exchange. In recognition of his expertise and contribution, he was ennobled by the King in 1909 and given the title of baron.Footnote63

The statue of Zsigmond Kornfeld was commissioned by the Stock Exchange.Footnote64 Unfortunately, little else is known about this bust, except from that it was probably made by Alajos Stróbl and placed in the Stock Exchange Palace.Footnote65 However, this information is sufficient to establish that it was a token of recognition from an important lay institution, which probably had no intention of emphasising Jewishness in any way. However, if we consider that, throughout its history, a significant proportion of the directors of the Exchange were of Jewish origin,Footnote66 the statue takes on a different meaning. In this context, it represented the Jewish presence in business and economy, the opportunity to get a foothold in this field, which was seized and used by talented Jews.

The memory of certain communities

The plaque commemorating the heroic deaths of the Jewish boys’ orphanage was originally placed on the wall of the new orphanage building in Vilma királynő street (today Városligeti fasor). The Pest Israelite Congregation bought the land in 1900 and commissioned Alfréd Wellisch to design a new, larger building for the orphanage. During the Holocaust, the residents of the Jewish girls’ orphanage were also transferred to this building. Members of the Arrow Cross Party raided the orphanage and killed some of them, and the building itself was also damaged by bombing. In 1945, the orphanage was rebuilt according to the plans of Alfréd Hajós. The building was nationalised and demolished in 2008.Footnote67 The memorial plaque, originally commissioned by the pupils of the orphanage, was probably destroyed at the same time.

The Pest Israelite Congregation commissioned József Róna to design a memorial plaque to commemorate the community’s heroic dead. They paid him a 10.000 Pengő deposit and Róna produced three draft designs, but in the meantime, the community leaders decided they would rather erect a monument in their cultural hall. Róna sued the community and as a result, they had to pay him an additional 20.000 Pengő.Footnote68 Originally, the plaque would most probably have been placed on the wall of the Heroes’ Temple, a small synagogue built in 1931 near the Dohány street synagogue in honour of the Jewish soldiers killed in the First World War.

Although nothing more is known about the fate of the plaque, this episode is instructive as it shows that a just over a decade after the end of the First World War, the commemoration of fallen soldiers was already institutionalised and intertwined with a religious framework. These plaques served not only as commemorative texts but also as symbols of Jewish participation in the war effort. The placement of the plaque commemorating the heroic deaths of the Israelite boys’ orphanage was quite obvious; the Pest Israelite Congregation’s initial decision to place a plaque on the wall of the Heroes’ Temple served more representative purposes. The small temple itself is a building that expresses the shared history of Jews and non-Jews, solidarity, and participation in national undertakings and tragedies.

Conclusions

Above, we presented eight statues and memorial plaques erected for Jewish personalities. Our categorisation shows the core values of which the Jewish community was proud in the age of emancipation: scientific achievements, charitable activities, talent for business and economics, and participation in the First World War. While these achievements reflect the social standing of Budapest’s Jewish community, the commissioners intended to insert the monuments as text into the urban environment to represent Jewish-Hungarian identity, belonging to the Hungarian nation, and Jewish contribution to social and cultural life. Unsurprisingly, business and the liberal professions were the areas in which Jews were ‘overrepresented’ and associated with them by the majority society.Footnote69 It is important to note that only one of the immortalised personalities was a religious leader, indicating the extent of assimilation; the community chose to commemorate the lives and achievements of its lay members.

In contrast, the non-Jewish personalities who received statues were mostly politicians, members of royal families, war heroes, and artists. This, in turn, shows that for centuries, Jews were not allowed to participate in the governance of the country. Their presence in trade and commerce predestined them to gain a foothold in the economic sphere after emancipation, while traditional Jewish education and their pre-existing educational network prepared them to participate in and seek opportunities in lay, non-Jewish higher education.Footnote70

For women (both Jewish and non-Jewish), these possibilities were severely limited. For example, women were not admitted to universities until 1895, and even then, only to certain faculties.Footnote71 As a result, there were far fewer statues of women of note. It is symbolic that the first public statue of a woman was of a Jewish woman, Johanna Bischitz. In the city’s public spaces, women were usually depicted as allegorical figures, except the members of royal families (see, for example, the sculpture of Maria Theresa at Heroes’ Square. She was the only queen to get a place in the all-male pantheon),Footnote72 actresses (Róza Széppataki),Footnote73 and educators (Mrs. Pál VeresFootnote74). In contrast, the first Jewish women to be immortalised in statues were philanthropists who contributed to society by helping the poor. The intention behind these statues was to commemorate the combination of Jewish solidarity with marginalised, or segregated populations (which they had been for centuries) and merit earned through the scale and nature of their donations. The gendered reading of these statues reflects the traditional public/private divide: the only way for women to enter the public space was to be presented as promoters of the national cause.

In society, those with authority can define cultural identity by interpreting the past.Footnote75 However, as previous research has shown, urban environments are spaces of constant negotiation, and the Jewish minority also used their opportunities to offer their interpretations through monuments. The circumstances in which the sculptures were erected prove that the assimilated Jewish community felt a sense of belonging to the majority and sought to express this through the monuments. Many of the sculptors commissioned to create the statues were non-Jewish; there were non-Jewish, even religious, speakers and speeches at the inaugurations; furthermore, the location of the statues also supports this theory: at least four of them were placed outside the traditional ‘Jewish district’ (the 7th district of Budapest, where the majority of the inhabitants were Jewish). Thus, the statues were intended to be an integral part of the urban structure. The spaces where these statues were erected were semi-public private spaces: owned by the Jewish community or the factory owner. It is not surprising that when anti-Semitism increased, these statues were removed.

The last of the monuments discussed in this article was commissioned in 1931. Just one year later, the Nazi Party became the largest party in the German parliament in the elections, while in Hungary a racist politician, Gyula Gömbös, became prime minister. This shift to the right and subsequent events, such as the first major anti-Jewish law in 1938, prevented the erection of any more statues commemorating Jewish figures. Soon, Hungarian Jews became second-class citizens as their rights were curtailed and anti-Semitism among the non-Jewish population increased.

Of the sculptures and plaques analysed, only two can still be seen where they were originally placed: the plaques of Sámuel Kohn and Ignác Goldziher. Two others were demolished, one was removed, and it is unknown what happened to the statues of Zsigmond Kornfeld and Adél Bródy. Their destruction offers a glimpse of how the reading of urban landscape changed and was renegotiated, and how the reading intended by the commissioners was rejected by the observers. While all of the monuments lacked Jewish symbolism and specificity, and in most cases, the commissioners aimed to prove Jewish belonging to the Hungarian nation, those who demolished the statues, read them through an exclusionary, anti-Semitic lens and denied this belonging. In this way, Jewishness could not be read as a text in public space, because the space where they wanted to belong: the multicultural, inclusive, and secular public space, did not exist.Footnote76 As a result, the memory of those Jews who were known at the time disappeared from the urban environment. In this sense Jews become ‘invisible’ but the process of invisibility also raises the question of responsibility and illusions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02619288.2024.2339655)

Notes

1. See the speech in print and a description of the inauguration in: Magyar Gyáripar, January 1, 1925, 6–7.

2. Alajos Stróbl (1856–1926), Hungarian sculptor and teacher, leading artist of the 19th century.

3. Manfréd Weiss’ bust, Köztérkép, (accessed January 10, 2023) https://www.kozterkep.hu/40520/weiss-manfred-mellszobor.

4. Bárány, “Diebold Herman 140 éve született.”

5. Köztérkép, (accessed January 10, 2023) https://www.kozterkep.hu/40520/weiss-manfred-mellszobor.

6. Szapor, et al., Jewish Intellectual Women.

7. Klacsmann, “Memory Walk.”

8. Braham, A népirtás politikája, 7–9.

9. Dunstan, “Reading Victorian Sculptures,” 6.

10. Gluck, “The Budapest Flaneur,” 4.

11. Szabó, “The Changing Memories of Jewish Budapest,” 135–7.

12. Frojimovics et al., A zsidó Budapest, 634–5.

13. Gluck, A láthatatlan zsidó Budapest, 9, 11.

14. Nora, “Volume Introduction,” xxxix.

15. Garbowski, “The City as a Lieu de Mémoire,” 35.

16. Keith, “Walter Benjamin,” 414.

17. Benjamin, Das Passagen-Werk.

18. Wallach, A City in Fragments.

19. Jazeel, “The “City” as Text.”

20. Wallach, A City in Fragments.

21. Duncan, The City as Text, 4.

22. Dunstan, “Reading Victorian Sculptures,” 3.

23. Ibid., 4–5.

24. Reuveni, Reading Germany, 3–4.

25. Duncan, The City as Text, 20.

26. Kepecs, A zsidó népesség száma településenként, 26.

27. Karády, The Jews of Europe, 49.

28. On the social characteristics and identity of the Budapest Jewish community, see: Karády, Allogén elitek, 31–7.

29. Ibid., 21.

30. Turán, “150th anniversary of the Hungarian Jewish Congress,” 204.

31. Karády, “Politikai antiszemitizmus és nemzetállam-építés.”

32. Act XVII of 1867; see: Jogtár, (accessed January 4, 2023) https://net.jogtar.hu/ezer-ev-torveny?docid=86700017.TV&searchUrl=/ezer-ev-torvenyei%3Fpagenum%3D27.

33. Act XLII of 1895; see: Jogtár. (accessed January 4, 2023)

34. Karády, Allogén elitek, 38.

35. Ibid., 32–5.

36. Komoróczy, A zsidók története Magyarországon, 47–8.

37. In contrast, most Orthodox synagogues were hidden behind the ordinary façade of tenement houses or did not have a decorated appearance. Due to their architectural value and historical significance, the UNESCO and the EU appointed several Neolog synagogues as cultural heritage.

38. On the anti-Semitic tendencies of the era and their origins, see: Karády, “A magyarországi antiszemitizmus,”10–2.

39. Act XXV of 1920; see: Jogtár, (accessed January 25, 2023) https://net.jogtar.hu/ezer-ev-torveny?docid=92000025.TV&searchUrl=/ezer-ev-. The text of the law itself did not contain any restriction to Jews, however, its so-called minority clause classified Jews as a “racial minority” and restricted their quota in higher education to 6%. This minority clause was withdrawn in 1928. On the place of the numerus clausus law in Hungarian history and its connection to the Holocaust, see: Kovács M., “A numerus clausus és a zsidótörvények.”

40. Hall, Planning Europe’s Capital Cities, 3, 322.

41. Dunstan, “Reading Victorian Sculptures,” 7.

42. Berza, Budapest lexikon, 455.

43. Sisa, A magyar művészet a 19. században, 260.

44. Majik and Szarvas, Magyar rapszódia, 17. See also the website of the Hungarian University of Fine Arts, (accessed January 5, 2023) https://www.mke.hu/az_egyetem_tortenete/index.php.

45. Wehner, “A köztér (részleges) nyilvánossága.”

46. See for instance a description about the various planned locations of the István Báthory statue in Budapest, and the variety of authorities which were involved in the 1930s: Gerencsér, “Az elfelejtett szobor históriája,”41–4.

47. See numerous examples in Liber, Budapest szobrai és emléktáblái.

48. A mi Erzsébetvárosunk, (accessed January 6, 2023) https://mierzsebetvarosunk.blog.hu/2015/04/02/hollo_utca_4.

49. Kohn, A zsidók története Magyarországon. The volume is digitised and accessible online at (accessed January 6, 2023) http://real-eod.mtak.hu/5916/1/000911349.pdf. Information on Dr Sámuel Kohn: A Dohány utcai zsinagóga honlapja, (accessed January 6, 2023) http://www.dohany-zsinagoga.hu/?page_id=39 , and Ujvári, Magyar zsidó lexikon, 494–5.

50. Ujvári, Magyar zsidó lexikon, 319–20.

51. See the Yellow Star Houses Project’s website: (accessed January 6, 2023) http://www.yellowstarhouses.org/#.

52. On this topic, see: Szapor, Pető, Hametz, Calloni, Jewish Intellectual Women.

53. Gerő, A szeretet munkásai, 181–2. In this publication, the date of the unveiling is December 10, 1889, however, Vasárnapi Újság published photos of the statue already on December 1 (Vasárnapi Újság, December 1, 1889, 785), and Egyenlőség, the most well-known Jewish periodical wrote that the inauguration happened on November 10 (Egyenlőség, November 17, 1889, 4–7).

54. Cseh, “Zsidó jótevők és nem-zsidó rászorulók.”

55. Today, the building is a tenement house and a kindergarten operates in it. Apart from the pedestal, there is nothing left to remind of the Jewish past.

56. Ibid., and Viktor Cseh’s email to Borbála Klacsmann, July 17, 2020.

57. Liber, Budapest szobrai és emléktáblái.

58. Zsuzsanna Toronyi’s message to Borbála Klacsmann, Facebook, July 3, 2020.

59. Jeney, “Freund Vilmos, a budapesti kórházépítész.”

60. Vasárnapi Újság, May 15, 1897, 322.

61. Zsuppán, “Ha az egész Liget-projekt.”

62. Ujvári, Magyar zsidó lexikon, 959.

63. Ibid., 505.

64. Radnóti, Kornfeld Zsigmond, 175.

65. The Palace has been empty since 2009, and currently it is closed to the public, therefore it is not possible to check whether the statue is still there.

66. Bolgár, “Újabb mítoszok.”

67. Óvás! Egyesület, (accessed January 3, 2023) http://lathatatlan.ovas.hu/index.htm?node=47986.

68. Vállalkozók Lapja, vol. LII, no. 25 (1931), 6.

69. Bolgár, “Pengébb zsidók, deltásabb keresztények,” 15.

70. Komoróczy, A zsidók története Magyarországon, 54–5.

71. Domonkos, “Mióta járhatnak egyetemre a nők.” The first woman to enrol in university was Vilma Glücklich who studied mathematics and physics, and the first to receive a diploma, was Sarolta Steinberger, in 1900. Both of them were Jewish. Women received equal rights to attend university like men only in 1946.

72. Csordás, “Habsburg-restauráció a Hősök terén.”

73. Köztérkép, (accessed January 18, 2023) https://www.kozterkep.hu/12710/deryne-szeppataki-roza.

74. Vasárnapi Újság, May 6, 1906, 282.

75. Duncan, The City as Text, 22.

76. See more in Gluck, A láthatatlan zsidó Budapest.

Bibliography

- Bárány, T. ““Diebold Herman 140 éve született” [Herman Diebold Was Born 140 Years Ago]. XXI. kerületi hírhatár.” Accessed January 10, 2023. http://www.21keruleti-hirhatar.hu/index_cikk.php?hh=egy-epitesz-emlekere

- Benjamin, W. Das Passagen-Werk. Vol 2. Frankfurt am Main: Rolf Tiedemann, 1983.

- Berza, L., ed. Budapest lexikon. Vol 2. Budapest: Akadémiai, 1993.

- Bolgár, D. “Újabb mítoszok a zsidó jólétről [Further myths about Jewish wealth].” Eszmélet. Accessed March 2, (2023).

- Bolgár, D. “Pengébb zsidók, deltásabb keresztények. Diskurzus a zsidó testről és észről a 19. századtól a holokausztig” [Smarter Jews, stronger Christians. Discourse on the Jewish body and mind from the 19th century to the Holocaust].” In Egy polgár emlékkönyvébe – Tanulmányok a 66 éves Gerő András tiszteletére [To the Album of a Bourgeois – Essays for the 66-year-old András Gerő], edited by D. Bolgár, K. Fenyves, and E. V. Vér, 13–80. Budapest: Kir Bt, 2018.

- Braham, R. L. A népirtás politikája – a Holocaust Magyarországon [The Politics of Genocide – the Holocaust in Hungary]. Vol 1. Budapest: Belvárosi Könyvkiadó, 1997.

- Cseh, V. ““Zsidó jótevők és nem-zsidó rászorulók a 19. századi Budapesten” [Jewish philanthropes and non-Jewish poor in 19th-century Budapest].” Zsido.com. Accessed January 9, 2023. https://zsido.com/zsido-jotevok-es-nem-zsido-raszorulok-19-szazadi-budapesten/

- Csordás, L. “’Habsburg-restauráció a Hősök terén’ [Habsburg restoration at Heroes’ Square]. Múlt-kor.” Accessed January 18, 2023. https://mult-kor.hu/cikk.php?id=5314

- Dohány utcai zsinagóga. Accessed January 6, 2023a. http://www.dohany-zsinagoga.hu/

- Domonkos, C. “Mióta járhatnak Egyetemre a nők Magyarországon?” [Since When Can Women Attend University in Hungary?] Tudás.Hu.” Accessed January 18, 2023. https://tudas.hu/miota-jarhatnak-egyetemre-a-nok-magyarorszagon/

- Duncan, J. S. The City as Text: The Politics of Landscape Interpretation in the Kandyan Kingdom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Dunstan, A. “Reading Victorian Sculpture.” 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century 22, no. 22 (2016). doi:10.16995/ntn.776.

- Egyesület, Ó. Accessed January 3, 2023. http://lathatatlan.ovas.hu/

- Frojimovics, K., G. Komoróczy, V. Pusztai, and A. Strbik. A zsidó Budapest. The Jewish Budapest Vol 2 Budapest: MTA, 1995.

- Garbowski, C. “The City as a Lieu de Mémoire: Phenomenological, Symbolic, and Self-Reflective Levels of the Past in Lublin’s Present.” The Polish Review 63, no. 3 (2018): 35–48. doi:10.5406/polishreview.63.3.0035.

- Gerencsér, T. “Az elfelejtett szobor históriája – A zuglói Báthory-szobor [The history of the forgotten statue – The Báthory statue of Zugló].” Hitel 24, no. 11 (2011): 35–55.

- Gerő, K. A Szeretet munkásai – a Pesti Izraelita Nőegylet Története [The Workers of Love – the History of the Pest Israelite Women’s Association]. Budapest: private publication, 1937.

- Gluck, M. “The Budapest Flaneur: Urban Modernity, Popular Culture, and the “Jewish Question” in Fin-de-Siècle Hungary.” Jewish Social Studies 10, no. 3 (2004): 1–22. doi:10.1353/jss.2004.0012.

- Gluck, M. A láthatatlan zsidó Budapest [The Invisible Jewish Budapest]. Budapest: Múlt és Jövő, 2017.

- Hall, T. Planning Europe’s Capital Cities: Aspects of Nineteenth-Century Urban Development. London: E & FN Spon, 1997.

- Hungarian University of Fine Arts. Accessed January 5, 2023. https://www.mke.hu/

- Jazeel, T. “The ‘City’ as Text.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 45, no. 4 (2021): 658–662. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.13029.

- Jeney, A. “Freund Vilmos, a budapesti kórházépítész” [Vilmos Freund, the hospital architect of Budapest]. Építészfórum. Accessed January 12, 2023. https://epiteszforum.hu/freund-vilmos-a-budapesti-korhazepitesz

- Jogtár. Accessed January 13, 2023b. https://net.jogtar.hu/

- Karády, V. ““A magyarországi antiszemitizmus: kísérlet egy történeti kérdéskör megközelítésére” [Hungarian Anti-Semitism: an attempt to approach a historical issue].” Regio 2, no. 2 (1991): 5–35.

- Karády, V. “Politikai antiszemitizmus és nemzetállam-építés Közép-Európában” [Political anti-Semitism and the building of nation states in Central Europe].” In Magyar megfontolások a Soáról [Hungarian Considerations Concerning the Shoah], edited by G. Hamp, Ö. Horányi, and L. Rábai, Budapest – Pannonhalma: Balassi Kiadó, 1999. Accessed January 3, 2023. http://www.magyarpaxromana.hu/kiadvanyok/soa/karady.htm

- Karády, V. The Jews of Europe in the Modern Era. Budapest – New York: CEU Press, 2004.

- Karády, V. Allogén elitek a modern magyar nemzetállamban [Allogenic elites in the modern Hungarian nation-state]. Budapest: Wesley János Lelkészképző Főiskola, 2012.

- Keith, M. “Walter Benjamin, Urban Studies and the Narratives of City Life.” In A Companion to the City, edited by G. Bridge and S. Watson, 410–429. Oxford: Blackwell, 2003.

- Kepecs, J., ed. A zsidó népesség száma településenként (1840–1941) [Statistics of the Jewish population by townships (1840–1941)]. Budapest: KSH, 1993.

- Klacsmann, B. “Memory Walk: History Through Monuments.” In The Future of Holocaust Memorialization. Confronting Racism, Anti-Semitism, and Homophobia Through Memory Work, edited by A. Pető and H. Thorson, 100–104. Budapest: Tom Lantos Institute, 2015.

- Kohn, S. A zsidók története Magyarországon a legrégibb időktől a mohácsi vészig [The history of the Jews in Hungary from the earliest times until the battle of Mohács]. Budapest: Athenaeum, 1884.

- Komoróczy, G. A zsidók története Magyarországon [The History of the Jews in Hungary]. Vol 2. Pozsony: Kalligram, 2012.

- Mária, and Kovács, M. “A Numerus Clausus és a zsidótörvények” [The Numerus Clausus and the Anti-Jewish Laws].” In A holokauszt Magyarországon hetven év múltán [The Holocaust in Hungary seventy years later], edited by R. L. Braham and A. Kovács, 49–58. Budapest: Múlt és Jövő, 2015.

- Köztérkép. Accessed 10 January 2023. https://www.kozterkep.hu/

- Liber, E. Budapest szobrai és emléktáblái [Budapest’s statues and memorial plaques]. Budapest: Szfőv. Háziny, 1934.

- Majik, N., and G. Szarvas, eds. Magyar rapszódia – festészet, grafika, szobrászat [Hungarian rhapsody – Painting, graphics, sculpture]. Lviv: Lvivi Nemzeti Művészeti Galéria, 2019.

- A mi Erzsébetvárosunk. Accessed January 6, 2023c. https://mierzsebetvarosunk.blog.hu/2015/04/02/hollo_utca_4

- Nora, P. Volume Introduction. In Rethinking France – Les Lieux de Mémoire Vol 1 edited by P. Nora, xxxv–xl, Chicago – London; University of Chicago Press, 2001.

- Radnóti, J. Kornfeld Zsigmond. Budapest: private publication, 1931.

- Reuveni, G. Reading Germany: Literature and Consumer Culture in Germany Before 1933. New York – Oxford: Berghahn, 2006.

- Sisa, J., ed. A magyar művészet a 19. században – Képzőművészet [Hungarian art in the 19th century – Fine arts]. Budapest: MTA – Osiris, 2018.

- Szabó, A. “The Changing Memories of Jewish Budapest: Pre- and Post-Holocaust Representations of a City.” Cultural History 10, no. 1 (2021): 133–149. doi:10.3366/cult.2021.0234.

- Szapor, J., A. Pető, M. Hametz, and M. Calloni. Jewish Intellectual Women in Central Europe 1860–2000. New York – Queenston: The Edwin Mellen Press, 2012.

- Turán, T. “150th Anniversary of the Hungarian Jewish Congress.” Jewish Culture and History 21, no. 3 (2020): 203–212. doi:10.1080/1462169X.2020.1796371.

- Ujvári, P., ed. Magyar zsidó Lexikon [Hungarian Jewish Lexicon]. Budapest: Pallas, 1929.

- Wallach, Y. A City in Fragments: Urban Text in Modern Jerusalem. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2020.

- Wehner, T. ““A köztér (részleges) nyilvánossága” [The (partial) publicity of public spaces].” Új Forrás 36, no. 9 (2004): 69–78.

- Yellow Star Houses Project. Accessed January 6, 2023d. http://www.yellowstarhouses.org/

- Zsuppán, A. ““Ha az egész Liget-projekt ilyen lenne, mindenki szeretné” [If the whole Liget project was like this, everyone would like it]. Válasz Online.” Accessed January 12, 2023. https://www.valaszonline.hu/2021/01/28/ha-az-egesz-liget-projekt-ilyen-lenne-mindenki-szeretne/